Abstract

Advances in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are attributed to several aspects such as new classification criteria enabling early diagnosis and intensive treatment with the application of treat-to-target principles as well as better understanding of the pathogenesis of RA contributing to the development of targeted therapies. However, reaching remission is still not achieved in most patients with RA, which is one of the driving forces behind the continuous development of novel therapies and the optimization of therapeutic strategies. This review will outline several new therapeutic antibodies modulating anti-inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-10 and pro-inflammatory mediators granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, fractalkine, and IL-6 that are in various stages of clinical development as well as the progress in manufacturing biotechnologies contributing to the next generation of antibodies and their potential to expand the therapeutic armamentarium for RA. In addition, the fate of unsuccessful therapies including agents targeting IL-15, the IL-20 family, IL-21, chemokine CXCL10, B-cell activating factor (BAFF), and regulatory T (Treg) cells or a novel concept targeting synovial fibroblasts via cadherin-11 will be discussed.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, biological therapies, monoclonal antibodies, therapeutic strategies

Introduction

In recent years, dramatic advances have emerged across medical disciplines in understanding the pathogenesis of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, which are accompanied by a significant shift in treatment options 1. One of the most significant advances has been shown in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), in which the discovery of glucocorticoid activity was among the first therapeutic milestones in the 1950s 2, followed by widespread use of methotrexate since the turn of the 1980s and 1990s 3. Later on, success in the treatment of RA can be attributed to the introduction of new classification criteria allowing earlier diagnosis and treatment and application of the treat-to-target principles with the aim to induce remission or at least low disease activity 4– 6. The biggest breakthrough in the treatment of RA, however, comes with biologic therapy, which has gradually begun to spread since the beginning of the new millennium with the introduction of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors into clinical practice 7.

Targeted disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), consisting of biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs) and targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs), antagonize soluble cytokines and their receptors and directly affect immune cell activity or intracellular signaling pathways 8– 10. The effect of targeted therapies is relatively rapid and often accompanied by a significant suppression of inflammation. In most cases, it can substantially improve quality of life and stop or significantly slow the progression of functional and structural impairment 11. Currently, out of the biological therapies, five original TNF inhibitors and already even more biosimilar TNF inhibitors, two interleukin-6 receptor (IL-6R) inhibitors, and one IL-1 receptor inhibitor as well as B-lymphocyte (CD20) and co-stimulatory signal (CD28-B7 interaction) for T-cell activation inhibitors are available for the treatment of RA ( Table 1). In addition to bDMARDs, two tsDMARDs, including Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) tofacitinib (pan-JAKi) and baricitinib (JAK1/2i) ( Table 1), have expanded the treatment armamentarium 12.

Table 1. Currently approved targeted therapies for rheumatoid arthritis.

| Original biologic DMARDs | Target | Structure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infliximab (3–5 mg i.v. every 8 weeks) | TNF | Chimeric mAb | ||

| Adalimumab (40 mg s.c. every other week) | TNF | Human mAb | ||

| Etanercept (50 mg s.c. every week) | TNF | Fc fusion protein | ||

| Golimumab (50 mg s.c. once a month) | TNF | Human mAb | ||

| Certolizumab pegol (200 mg s.c. every other week) | TNF | Humanized PEGylated Fab fragment | ||

| Rituximab (1,000 mg i.v. every 6 months) | CD20 (B-cells) | Chimeric mAb | ||

| Abatacept (125 mg s.c. every week) | CD80/86 (costimulation) | Fc fusion protein | ||

| Tocilizumab (162 mg s.c. every week) | IL-6R | Humanized mAb | ||

| Sarilumab (150–200 mg s.c. every other week) | IL-6R | Human mAb | ||

| Targeted synthetic DMARDs | Target | Structure | ||

| Tofacitinib (10 mg daily) | JAK1, JAK2, JAK3 | Small molecule | ||

| Baricitinib (2–4 mg daily) | JAK1, JAK2 | Small molecule | ||

| Biosimilar DMARDs | Target | Reference product | Approved by EMA/FDA | Manufacturer |

| Remsima/Inflectra (CT-P13) | TNF | Infliximab | 2013/2016 | Celltrion |

| Flixabi/Renflexis (SB2) | TNF | Infliximab | 2016/2017 | Samsung Bioepis/Biogen |

| Zessly/Ifixi (GP1111/PF-06438179) | TNF | Infliximab | 2018/2017 | Sandoz (EU)/Pfizer (US) |

| Amgevita/Amjevita (ABP 501) | TNF | Adalimumab | 2017/2016 | Amgen |

| Cyltezo (BI 695501) | TNF | Adalimumab | 2017/2017 | Boehringer Ingelheim |

| Imraldi (SB5) | TNF | Adalimumab | 2017/ * | Samsung Bioepis/Biogen |

| Hyrimoz (GP2017) | TNF | Adalimumab | 2018/2018 | Sandoz |

| Hulio (MYL-1401A) | TNF | Adalimumab | 2018/2018 | Mylan |

| Benepali (SB4) | TNF | Etanercept | 2016/ * | Samsung Bioepis/Biogen |

| Erelzi (GP2015) | TNF | Etanercept | 2017/2016 | Sandoz |

| Truxima (CT P10) | CD20 | Rituximab | 2017/2018 | Celltrion/Hospira (Pfizer) |

| Rixathon | CD20 | Rituximab | 2017 | Sandoz (EU) |

CD, cluster of differentiation; DMARDs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; EMA, European Medicines Agency; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; IL, interleukin; IL-6R, interleukin-6 receptor; i.v., intravenously; JAK, Janus kinase; mAb, monoclonal antibody; s.c., subcutaneously; TNF, tumor necrosis factor

*accepted for review by FDA, assessed 19 March 2019.

Although the fate of patients with RA has improved significantly and a milder course of disease can be observed than in the past 13, persistent remission, let alone drug-free remission or complete cure, is still elusive 14. This review will outline several new directions for the potential new therapeutic antibodies and treatment strategies for RA, new biological drugs against new targets, and biological drugs against already-known targets that are currently in early or late stages of clinical development.

Cytokine and cell-targeted therapies

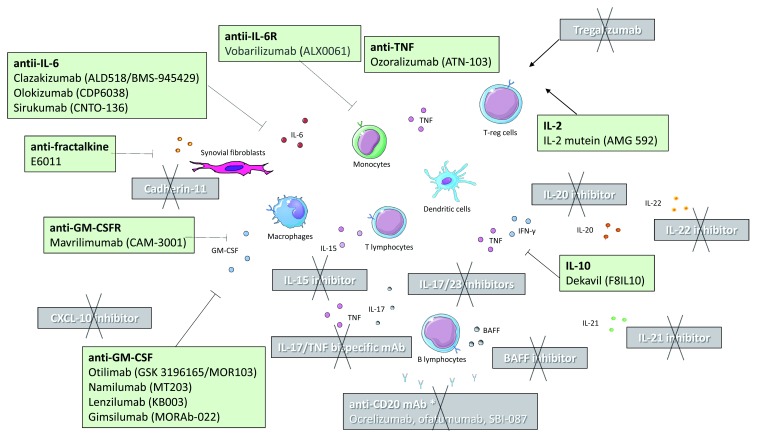

The development of biological therapies for RA has been facilitated by two main assumptions. The first prerequisite is an increasing understanding of the pathophysiological processes in which systemic immune mediators, immune cells, and signaling pathways play a role and have become targets for specific immune interventions 15. The second important assumption is the dynamic development of the pharmaceutical industry and advances in genetic engineering and biotechnology 16. Potential therapeutic antibodies that are in various stages of clinical development are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Potential biological therapies for the management of rheumatoid arthritis that are currently in various stages of clinical development.

Black text shows therapies that were effective in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, although some of the drugs are not further evaluated in rheumatoid arthritis owing to company prioritization. White text shows therapies that failed to prove efficacy or whose clinical trials were terminated owing to safety concerns.

*However, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody such as rituximab is effective and licensed for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

BAFF, B-cell activating factor; CXCL, C-X-C motif ligand; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; GM-CSFR, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor; IL, interleukin; mAb, monoclonal antibody; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; Treg, T regulatory

New targets in later phases of development

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) was first described in the 1970s and is considered a pro-inflammatory cytokine, which is upregulated upon stimulation with multiple mediators such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or TNF and is produced by a variety of immune as well as resident tissue cells 17. As the expression of GM-CSF is increased in the synovial tissue and synovial fluid of patients with RA, it can stimulate the synthesis of adhesion molecules and pro-inflammatory cytokines, and it can also activate synovial fibroblasts and polarize macrophages into an inflammatory M1 phenotype, thus promoting rheumatoid synovial inflammation 18. At present, several monoclonal antibodies targeting the GM-CSF pathway in patients with RA are being studied 19.

Mavrilimumab (CAM-3001), a monoclonal antibody against GM-CSF receptor alpha being developed by MedImmune, has been extensively evaluated in the EARTH development program 20, 21. Mavrilimumab was administered in a phase II dose-ranging study (10–100 mg) every other week for a total of 12 weeks to patients with active RA on background methotrexate 20. The primary endpoint was met: the greater proportion of patients receiving mavrilimumab compared with placebo achieved a ≥1.2 decrease in disease activity score (DAS28-CRP) from baseline at week 12 (55.7% versus 34.7%; p=0.003). The 100 mg dose demonstrated a significant effect versus placebo on DAS28-CRP <2.6 (23.1% versus 6.7%, p=0.016). In a phase IIb study in RA patients with inadequate response to at least one conventional synthetic DMARD (csDMARD), significantly more mavrilimumab-treated (150, 100, and 30 mg) patients achieved American College of Rheumatology definition of improvement (ACR20) compared with placebo at week 24 (73.4%, 61.2%, 50.6% versus 24.7%, respectively [ p<0.001]) and clinically meaningful response was observed as early as one week after treatment initiation 21. Another phase IIb study evaluated the efficacy and safety of mavrilimumab and golimumab (anti-TNF) in patients with RA who have had an inadequate response to csDMARDs and anti-TNF agents 22. Mavrilimumab demonstrated numerically lower response rates compared with golimumab in patients with inadequate response to csDMARDs and similar efficacy to that of golimumab in the anti-TNF non-responders. However, the study was not powered to provide a direct comparison between mavrilimumab and golimumab, and it is probable that a suboptimal dosage of mavrilimumab was used (100 mg every other week) 22. Pulmonary safety assessments were performed because the inhibition of GM-CSF signaling has the potential to affect the clearance of surfactant by alveolar macrophages and thus be responsible for pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Although there was a potential risk of this rare disease, including neutropenia, infections, and other lung toxicities associated with the blockade of GM-CSF, none of these studies nor a long-term extension study up to 3.3 years revealed such concerns 23. Mavrilimumab demonstrated sustained efficacy and an acceptable safety profile; however, due to future clinical development plans, the study was terminated (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01712399).

Otilimab (GSK 3196165 or MOR103) is a fully human high-affinity IgG monoclonal antibody against GM-CSF being developed by GlaxoSmithKline. In a phase IIb dose-ranging study (BAROQUE), patients with active RA were randomized to placebo or otilimab (22.5, 45, 90, 135, or 180 mg) administered weekly for five injections, and then every other week until week 50 24. Dose-related treatment effect with the onset of clinical response as early as week one was observed for all doses. However, the primary endpoint (DAS28 remission at week 24) was not achieved; it was only numerically higher in patients at the highest dose of otilimab versus placebo (16% versus 3%; p=0.134). In addition, exposure to otilimab was lower than predicted owing to increased apparent clearance. In July 2019, a phase III clinical program (“ContRAst”) was announced, in which otilimab (90 and 150 mg weekly doses) will be compared with two treatments with different modes of action: JAKi (tofacitinib) and anti-IL-6R (sarilumab) (https://www.gsk.com).

Namilumab (MT203), lenzilumab (KB003), and gimsilumab (MORAb-022) being developed by Takeda, KaloBios Pharmaceuticals, and Morphotek, respectively, are fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibodies against GM-CSF. While initial studies, at least with namilumab 25, demonstrated good safety and promising efficacy data, no further results from phase II studies have been reported so far 19. In addition, based on negative results from a psoriasis study 26 and results from a proof-of-concept study in RA (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02393378), further studies on namilumab in psoriasis and RA were terminated.

Interestingly, GM-CSF-targeting therapies are also being studied in other rheumatic diseases. For instance, otilimab was studied in patients with hand osteoarthritis and showed numerical reduction in pain and functional impairment, while little difference was observed with placebo on tender and swollen joints, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) endpoints 27. In patients with axial spondyloarthritis, a phase IIa proof-of-concept study evaluating the safety and efficacy of namilumab has been recruiting subjects since August 2018 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03622658).

Old targets with the focus on interleukin-6

In mid-2017, sarilumab (trade name Kevzara), a human monoclonal antibody against IL-6R, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of RA. Sarilumab showed significantly greater affinity to recombinant human IL-6R compared with tocilizumab and longer half-life with a similar safety profile 28, 29. Further biological drugs targeting IL-6 pathways are in development.

Clazakizumab (formerly ALD518 and BMS-945429) is a humanized monoclonal antibody against IL-6. In a phase IIb study 30, the primary endpoint was met; ACR20 response rates at week 12 were greater for clazakizumab (25, 100, and 200 mg) once monthly in combination with methotrexate (MTX) or clazakizumab monotherapy (100 and 200 mg) versus MTX (76.3%, 73.3% and 60.0% or 55.0% and 61.0% versus 39.3%; p<0.05). Also, remission rates as assessed by DAS28-CRP for clazakizumab plus MTX were greater than for MTX plus original adalimumab (40.0–49.2% versus 23.7%). The treatment was well tolerated with no unanticipated safety signals, consistent with the known pharmacologic effects of IL-6 blockade. Bristol-Myers Squibb has decided, based on portfolio prioritization, to return worldwide rights to clazakizumab to Alder BioPharmaceuticals. However, no further trials in RA are ongoing. The drug is currently in the early phases of development for the treatment of kidney transplant recipients with late antibody-mediated rejection (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03380377 and NCT03380962).

Olokizumab (CDP6038), a humanized monoclonal antibody against IL-6, was formerly developed by UCB Pharma and out-licensed to R-Pharm in 2013. In a phase IIb study, the primary endpoint was met; patients with active RA who had previously failed TNF inhibitor therapy demonstrated a significant decrease in DAS28-CRP at week 12 for all doses (60 mg, 120 mg, and 240 mg) administrated every four or every two weeks with results comparable to tocilizumab 31. Safety data were consistent with the use of IL-6-targeted therapy. Although no further results have been reported, phase III studies (CREDO) are either completed (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02760368, NCT02760433) or ongoing (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02760407, NCT03120949).

Sirukumab (CNTO-136; proposed trade name Plivensia), a human monoclonal antibody against IL-6, was developed by Centocor, GlaxoSmithKline, and Janssen Biotech. Sirukumab was investigated at doses of 100 mg and 50 mg every two and four weeks, respectively, in five phase III trials (SIRROUND) in a broad spectrum of patients with RA 32. Sirukumab showed significant improvements in disease activity, physical function, and quality of life along with inhibition of radiographic progression 33, 34. In a head-to-head study with adalimumab, sirukumab monotherapy showed greater improvements in disease activity (DAS28) but similar ACR50 response rates at week 24 35. Although the long-term safety of sirukumab seems to be similar to that of other IL-6-inhibiting agents, drug regulatory authorities suggested re-evaluating the safety profile of sirukumab for increased mortality rates in post open-label studies 32. Interestingly, the drug is currently under development for the treatment of major depressive disorder (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02473289).

New targets in early phases of development

Interleukin-2

IL-2, first cloned in the early 1980s, is predominantly produced by CD4 + T-cells and activated dendritic cells and has pleiotropic functions (for review, see 36). In high doses, IL-2 has been found to promote effector T cells, whereas low-dose IL-2 (ld-IL2) activates regulatory T cells (Tregs) and thus can have a broad therapeutic potential in many autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Indeed, the results of a first prospective, phase I–IIa clinical trial recently demonstrated that ld-IL2 (1,000,000 IU/day) given for five days and then once every other week for six months selectively activated and expanded Tregs without activating effector T cells. Furthermore, the authors reported signals of efficacy without safety issues in 46 patients across 11 autoimmune and inflammatory chronic diseases, including RA, ankylosing spondylitis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and psoriasis 37. In addition, in vitro and first-in-human data on a fusion protein of IL-2 mutein and human Fc (AMG 592) demonstrated dose-dependent, selective expansion of Tregs with no increase of major pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF, or interferon-γ (IFN-γ) in healthy volunteers 38. Based on these data, another phase Ib/IIa study evaluating the safety and efficacy of AMG 592 has been underway in patients with RA since May 2018 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03410056) but also in patients with SLE (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03451422).

Interleukin-10

IL-10 is produced by virtually all leukocytes and inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, e.g. TNF and IFN-γ, and abrogates antigen presentation and cell proliferation (for review, see 39). Despite the fact that it belongs to the most potent anti-inflammatory cytokine, limited efficacy with subcutaneously administered recombinant IL-10 was observed in a phase I trial in patients with RA in the past 40.

Several reasons for this discrepancy can be speculated, e.g. complex mechanism of pathophysiological action of IL-10, including potential pro-inflammatory activity 41, or short half-life of IL-10 hampering effective delivery of recombinant IL-10 to the sites of inflammation. To overcome these obstacles, Dekavil (F8IL10), a fully human anti-inflammatory immunocytokine composed of the vascular-targeting anti-fibronectin domain fused to IL-10, is under investigation in patients with RA 42. In a phase II clinical trial, Dekavil (30–600 mg/kg) is administered once a week for eight consecutive weeks by subcutaneous injection in combination with MTX to RA patients who have previously failed at least one TNF inhibitor. Preliminary data have demonstrated some signs of efficacy, with 46% demonstrating ACR20 clinical response after eight weeks of drug administration. Dekavil was well tolerated; however, mild injection site reaction occurred in 60% of the patients 43.

Fractalkine

Fractalkine (FKN) is known as a CX3C chemokine that promotes cell adhesion and chemotaxis, but also angiogenesis and osteoclastogenesis, and increases the production of inflammatory mediators, thus playing a significant role in the pathogenesis of RA (reviewed in 44). Recently, first data from a phase II, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with anti-FKN monoclonal antibody (E6011) in patients with active RA were released 45. This novel approach targeting FKN demonstrated reliable safety and promising efficacy with a dose-dependent clinical response, particularly in patients who showed higher baseline CD16 + monocytes (ACR20 at week 24: 30% for placebo, 46.7% for 100 mg, 57.7% for 200 mg, and 69.6% for 400/200 mg).

Unsuccessful biological therapies in rheumatoid arthritis

Although several pro-inflammatory cytokines play a significant role in the pathogenesis of RA and their inhibition contributed to a significant reduction in synovial inflammation and joint damage in an experimental model of arthritis and proved to be effective in early phases of development in humans, further studies failed to confirm significant efficacy 46 ( Table 2). For instance, IL-1 inhibitors are approved but only modestly effective in RA while highly effective in several autoinflammatory diseases 47. An early phase study with IL-15 inhibitor therapy seemed to be efficient 48, but a phase II clinical trial of a fully human monoclonal antibody against IL-15 failed to confirm significant efficacy (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00433875). Although targeting the IL-23/17 axis is effective in spondyloarthritis 49, strategies to block the IL-17 pathway, IL-12/23 p40, or IL-23 did not prove to be effective in patients with established RA, and the clinical research programs in RA were discontinued 50. Similarly, the IL-20 family of cytokines such as IL-20 and IL-22 play a significant role in the process of immune cell activation and bone destruction, and although an early phase trial with the IL-20 inhibitor fletikumab was well tolerated and effective, particularly in patients with seropositive RA, further studies with fletikumab and also IL-22 inhibitor fezakinumab were completed several years ago with negative or no final results released 51, 52. Although IL-21 plays an important role in the activation of the immune system, an early phase first-in-man trial with an IL-21 inhibitor (NNC0114-0000-0005) in patients with RA and healthy subjects was finished in 2012 and no further results have been released (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01208506). The first study demonstrating good safety and clinical efficacy of a chemokine inhibitor in patients with RA evaluated eldelumab (MDX-1100), a fully human anti-CXCL10 (anti-IP-10) monoclonal antibody 53; however, no further data were released.

Table 2. Selected unsuccessful biological therapies in rheumatoid arthritis.

| Drug | Target | Reason for failure | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| HuMax-IL15 (anti-IL-15 mAb) | IL-15 | Lack of efficacy | * |

| Brodalumab (anti-IL-17R mAb) | IL-17 | Lack of efficacy | 50 |

| Secukinumab (anti-IL-17A mAb) | IL-17 | Lack of efficacy | 50 |

| Ixekizumab (anti-IL-17A mAb) | IL-17 | Lack of efficacy | 50 |

| Bimekizumab (dual anti-IL-17A/F mAb) | IL-17 | Lack of efficacy | 50 |

| Ustekinumab (anti-IL-12/23p40mAb) | IL-12/IL-23 | Lack of efficacy | 50 |

| Guselkumab (anti-IL-23 mAb) | IL-23 | Lack of efficacy | 50 |

| Remtolumab (dual anti-TNF/IL-17A) | TNF/IL-17 | Not higher efficacy than adalimumab | 67 |

| NNC0114 (anti-IL-21 mAb) | IL-21 | No final results released | + |

| Fletikumab (anti-IL-20 mAb) | IL-20 | Lack of efficacy | 51 |

| Fezakinumab (anti-IL-22 mAb) | IL-22 | Negative or no final results released | 51 |

| Eldelumab (anti-CXCL10 mAb) | CXCL10 | Effective/safe, but no final results released | 53 |

| Mavrilimumab (anti-GM-CSFRα) | GM-CSFRα | Effective/safe, terminated (sponsor decision) | ɸ |

| Namilumab (anti-GM-CSF) | GM-CSF | Lack of efficacy | ♯ |

| Tabalumab (anti-BAFF) | BAFF | Lack of efficacy | 56 |

| Belimumab (anti-BAFF) | BAFF | Terminated (sponsor decision) | ± |

| Ocrelizumab (anti-CD20 mAb) | B-cells | Risk/benefit consideration | 54 |

| Ofatumumab (anti-CD20 mAb) | B-cells | Risk/benefit consideration | 54 |

| SBI-087 (CD20-targeted SMIP) | B-cells | Further development terminated | 55 |

| Alemtuzumab (anti-CD52 mAb) | T-cells | Safety | 57 |

| Keliximab (anti-CD4 mAb) | T-cells | Safety | 57 |

| Clenoliximab (anti-CD4 mAb) | T-cells | Safety | 57 |

| Tregalizumab (anti-CD4 mAb) | Treg cells | Lack of efficacy | 58 |

| RG6125 (anti-cadherin-11 mAb) | Cadherin-11 | Lack of efficacy | 59 |

BAFF, B-cell activating factor; CXCL, chemokine C-X-C motif ligand; GM-CSFRα, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor α; IL, interleukin; mAb, monoclonal antibody; SMIP, Small Modular ImmunoPharmaceutical; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; Treg, T regulatory

* ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00433875

+ ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01208506

ɸ ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01712399

♯ ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03622658

± ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00583557

Several strategies to inhibit B-cells were tested; for instance, humanized and human monoclonal antibodies ocrelizumab (trade name Ocrevus) and ofatumumab (trade name Arzerra) proved to be effective in patients with RA. However, after risk/benefit consideration, further studies were discontinued 54. In order to reduce the molecule, promote penetration to sites of inflammation, and improve efficacy, single-chain antibody polypeptides known as SMIPs (small modular immunopharmaceuticals) have been developed that are approximately one-half to one-third of the size of the standard monoclonal antibody. A next-generation, humanized SMIP protein therapeutic against the CD20 antigen (SBI-087) was evaluated in patients with RA, but further development was terminated 55. In addition, a further strategy to inhibit B-cell differentiation and survival via anti-B-cell activating factor (anti-BAFF) antibody has also failed in the treatment of patients with RA 56. Direct T-cell-targeting therapies such as alemtuzumab, keliximab, and clenoliximab did not show satisfactory results and were accompanied by a number of serious adverse reactions associated with severe CD4 + T-lymphopenia and rash 57. Tregalizumab (BT-061) is a humanized agonist antibody that selectively activates Treg lymphocytes and was tested as an innovative treatment for RA; however, it also did not show significant clinical benefit 58.

Recently, a novel approach targeting synovial fibroblasts in RA via the inhibition of cadherin-11 was presented 59. Although an interesting concept, anti-cadherin-11 (RG6125) given on top of anti-TNF therapy in patients with active RA failed to be more effective than placebo and the study was discontinued 59.

Next-generation antibodies

Conventional monoclonal antibodies (e.g. infliximab or adalimumab), Fc fusion proteins (etanercept and abatacept), and one antibody-derived molecule, a PEGylated anti-TNF Fab fragment (certolizumab pegol), are widely used for the treatment of patients with RA. Further advances in antibody engineering have led to the development of so-called next-generation therapeutic antibodies representing antibody fragments, dual/bispecific targeting variants, and immunocytokines 60– 62. The purpose is to develop antibodies that are smaller, more stable, have higher affinity and improved tissue penetration, and have lower immunogenicity and toxicity than conventional antibodies. For instance, nanobodies are single-domain antibodies that were originally developed after the discovery of camelid antibodies consisting of heavy chain variable domain (lacking the Fc-equivalent region) and can be engineered to bind to two (or even more) different antigens or epitopes on the cell surface, so-called bispecific (even multispecific) antibodies 61, 62. These antibodies are frequently used to treat cancer. Another therapeutic success was achieved by the development of immunocytokines, a fusion of an antibody and cytokine, which are widely studied as an anticancer therapy 63 and should extend cytokine half-life, reduce systemic adverse events, and deliver the cytokine specifically to sites of inflammation as mentioned above (Dekavil or AMG 592).

Belgian biopharmaceutical company Ablynx has developed unique new-generation bispecific therapeutic nanobodies ozoralizumab (ATN-103) and vobarilizumab (ALX0061) for the treatment of RA, the first humanized bispecific nanobodies, which neutralize TNF and IL-6R, respectively, and also bind to human serum albumin to increase the half-life. Ozoralizumab was tested in subcutaneous form at a once-monthly dosing interval in patients with RA and after 12 weeks of treatment, EULAR response was obtained in 97% of patients, an ACR20 response was achieved in 84%, and DAS28 remission was seen in 38% of patients with RA 64. A phase II study evaluating long-term safety and tolerability was completed in 2012 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01063803), and no further reports of development have been made so far. An early phase study with vobarilizumab demonstrated promising results as well, with ACR20 response rates of up to 84% and DAS28 remission rates of up to 58% 65. In addition, in a phase IIb monotherapy study (head-to-head versus tocilizumab) in RA patients 66, a similar proportion of vobarilizumab-treated patients achieved ACR20 response at week 12 compared with tocilizumab (73–81% versus 78%). Although more patients achieved DAS remission on highest vobarilizumab dose (225 mg every other week), when using more stringent CDAI and SDAI remission criteria, a similar efficacy was obtained in the monotherapy with vobarilizumab (5–10%) and tocilizumab groups (9–11%).

Remtolumab (ABT-122), developed by AbbVie, is another bispecific antibody, a full-length IgG with dual-variable domains (DVD-Ig), targeting two important human cytokines: TNF and IL-17A. Based on a TNF-transgenic mouse model of arthritis, dual inhibition of both cytokines proved to be more effective in suppressing inflammation and bone/cartilage destruction than either cytokine inhibitor alone 67. However, a phase II trial demonstrated that a strategy of dual inhibition of TNF and IL-17A with remtolumab does not appear to be significantly different from that of TNF inhibition alone with adalimumab in human patients with RA and psoriatic arthritis 68. In addition to this finding, recent data proved that another DVD-Ig lutikizumab (ABT-981) targeting IL-1α/β did not improve pain or synovitis in patients with both erosive hand osteoarthritis and knee osteoarthritis 69, 70.

Conclusion

Biologicals have become an essential part of the therapeutic armamentarium for RA, significantly ameliorating disease activity and improving quality of life. Furthermore, the progress in our understanding of the pathogenesis of RA has significantly contributed to the development of novel intracellular targeted therapies such as JAK inhibitors tofacitinib and baricitinib that have already been implemented in routine clinical practice. Nowadays, more selective JAK inhibitors and other targeted synthetic therapies are in various stages of clinical development in RA, which is beyond the scope of this review and is reported elsewhere 71, 72. In addition to the development of new therapies, the patent protection of older original biological agents expires and biosimilars have been entering the market within the last few years, thus lowering the price and enabling the treatment of more patients 73.

Despite current practice, early and intensive management with the treat-to-target approach, reaching remission is still not achieved in most patients, which is one of the driving forces behind the continuous development of novel therapies and the optimization of therapeutic strategies 74. Thus, advances in antibody engineering and further therapeutic targets such as neuro-immune modulation, gene therapy, and epigenetic modification are being evaluated in the treatment of RA 75– 77. In addition, the two main treatment strategies can be potentially applied in the future to improve disease outcome, halt further progression, or even cure the disease either 1) by an induction-maintenance regime with biological therapies administered as early as the diagnosis is established 78 or 2) even before clinical arthritis becomes apparent 79. Currently, several ongoing proof-of-concept trials are testing whether targeting T-cells or B-cells can induce immunological reset and be used to prevent the onset of RA 80. An advanced study demonstrated that a single infusion of 1,000 mg rituximab significantly delayed the development of arthritis in patients at risk of developing of RA 81. Other treatment approaches for preventive strategies may represent, for instance, the use of tolerogenic dendritic cells 82 or targeting the IL-17/23 axis 83 in order to block arthritis development in pre-clinical phases of the disease. However, further research is needed to determine which therapeutic agent or strategy would best suit each individual patient.

Editorial Note on the Review Process

F1000 Faculty Reviews are commissioned from members of the prestigious F1000 Faculty and are edited as a service to readers. In order to make these reviews as comprehensive and accessible as possible, the referees provide input before publication and only the final, revised version is published. The referees who approved the final version are listed with their names and affiliations but without their reports on earlier versions (any comments will already have been addressed in the published version).

The referees who approved this article are:

John Isaacs, Institute of Cellular Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK

Diego Kyburz, Experimental Rheumatology, University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Project for Conceptual Development for the institution of Ministry of Health Czech Republic - Institute of Rheumatology (number 023728).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; peer review: 2 approved]

References

- 1. Cho JH, Feldman M: Heterogeneity of autoimmune diseases: pathophysiologic insights from genetics and implications for new therapies. Nat Med. 2015;21(7):730–8. 10.1038/nm.3897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hench PS, Kendall EC, Slocumb CH, et al. : The effect of a hormone of the adrenal cortex (17-hydroxy-11-dehydrocorticosterone: compound E) and of pituitary adrenocortical hormone in arthritis: preliminary report. Ann Rheum Dis. 1949;8(2):97–104. 10.1136/ard.8.2.97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weinblatt ME, Maier AL: Longterm experience with low dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1990;22:33–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. : 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(9):1580–8. 10.1136/ard.2010.138461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, et al. : American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(3):404–13. 10.1136/ard.2011.149765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, et al. : Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;75(1):3–15. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, et al. : Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Trial in Rheumatoid Arthritis with Concomitant Therapy Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(22):1594–602. 10.1056/NEJM200011303432202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 8. Senolt L, Vencovský J, Pavelka K, et al. : Prospective new biological therapies for rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;9(2):102–7. 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buch MH, Emery P: New therapies in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(3):245–51. 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283454124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burmester GR, Feist E, Dörner T: Emerging cell and cytokine targets in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(2):77–88. 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stavre Z, Upchurch K, Kay J, et al. : Differential Effects of Inflammation on Bone and Response to Biologics in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Spondyloarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2016;18(12):72. 10.1007/s11926-016-0620-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schwartz DM, Kanno Y, Villarino A, et al. : JAK inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for immune and inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(12):843–62. 10.1038/nrd.2017.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 13. Kievit W, Fransen J, de Waal Malefijt MC, et al. : Treatment changes and improved outcomes in RA: an overview of a large inception cohort from 1989 to 2009. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52(8):1500–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/ket166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aletaha D, Smolen JS: Achieving Clinical Remission for Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. JAMA. 2019;321(5):457–458. 10.1001/jama.2018.21249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Veale DJ, Orr C, Fearon U: Cellular and molecular perspectives in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39(4):343–54. 10.1007/s00281-017-0633-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Azhar A, Ahmad E, Zia Q, et al. : Recent Updates on Molecular Genetic Engineering Approaches and Applications of Human Therapeutic Proteins. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2017;18(3):217–32. 10.2174/1389203717666160901114911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Burgess AW, Metcalf D: The nature and action of granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factors. Blood. 1980;56(6):947–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhou D, Huang C, Lin Z, et al. : Macrophage polarization and function with emphasis on the evolving roles of coordinated regulation of cellular signaling pathways. Cell Signal. 2014;26(2):192–7. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cook AD, Hamilton JA: Investigational therapies targeting the granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor-α in rheumatoid arthritis: focus on mavrilimumab. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2018;10(2):29–38. 10.1177/1759720X17752036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 20. Burmester GR, Weinblatt ME, McInnes IB, et al. : Efficacy and safety of mavrilimumab in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(9):1445–52. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burmester GR, McInnes IB, Kremer J, et al. : A randomised phase IIb study of mavrilimumab, a novel GM-CSF receptor alpha monoclonal antibody, in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):1020–30. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 22. Weinblatt ME, McInnes IB, Kremer JM, et al. : A Randomized Phase IIb Study of Mavrilimumab and Golimumab in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(1):49–59. 10.1002/art.40323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 23. Burmester GR, McInnes IB, Kremer JM, et al. : Mavrilimumab, a Fully Human Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor Receptor α Monoclonal Antibody: Long-Term Safety and Efficacy in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(5):679–89. 10.1002/art.40420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 24. Buckley C, Simon Campos JA, Yakushin S, et al. : A Phase IIb Dose-ranging Study of Anti-GM-CSF with Methotrexate Treatment in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) and an Inadequate Response to Methotrexate (abstract). Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(suppl 10): abstract number 1938. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huizinga TW, Batalov A, Stoilov R, et al. : Phase 1b randomized, double-blind study of namilumab, an anti-granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor monoclonal antibody, in mild-to-moderate rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):53. 10.1186/s13075-017-1267-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 26. Papp KA, Gooderham M, Jenkins R, et al. : Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) as a therapeutic target in psoriasis: randomized, controlled investigation using namilumab, a specific human anti-GM-CSF monoclonal antibody. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(6):1352–60. 10.1111/bjd.17195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schett G, Bainbridge C, Berkowitz M, et al. : A Phase IIb Study of Anti-GM-CSF Antibody GSK3196165 in Subjects with INflammatory Hand Osteoarthritis (abstract). Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(suppl 10): abstract number 1365. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rafque A, Martin J, Blome M, et al. : Evaluation of the binding kinetics and functional bioassay activity of sarilumab and tocilizumab to the human IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) alpha. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72 (suppl 3), abstract number 797. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-eular.2360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Avci AB, Feist E, Burmester GR: Targeting IL-6 or IL-6 Receptor in Rheumatoid Arthritis: What's the Difference? BioDrugs. 2018;32(6):531–46. 10.1007/s40259-018-0320-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 30. Weinblatt ME, Mease P, Mysler E, et al. : The efficacy and safety of subcutaneous clazakizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate: results from a multinational, phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo/active-controlled, dose-ranging study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(10):2591–600. 10.1002/art.39249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Genovese MC, Fleischmann R, Furst D, et al. : Efficacy and safety of olokizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitor therapy: outcomes of a randomised Phase IIb study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(9):1607–15. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bartoli F, Bae S, Cometi L, et al. : Sirukumab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: update on sirukumab, 2018. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14(7):539–47. 10.1080/1744666X.2018.1487291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Aletaha D, Bingham CO, 3rd, Tanaka Y, et al. : Efficacy and safety of sirukumab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-TNF therapy (SIRROUND-T): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multinational, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1206–17. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30401-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 34. Takeuchi T, Thorne C, Karpouzas G, et al. : Sirukumab for rheumatoid arthritis: the phase III SIRROUND-D study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(12):2001–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 35. Taylor PC, Schiff MH, Wang Q, et al. : Efficacy and safety of monotherapy with sirukumab compared with adalimumab monotherapy in biologic-naïve patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (SIRROUND-H): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, multinational, 52-week, phase 3 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(5):658–66. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 36. Klatzmann D, Abbas AK: The promise of low-dose interleukin-2 therapy for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(5):283–94. 10.1038/nri3823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 37. Rosenzwajg M, Lorenzon R, Cacoub P, et al. : Immunological and clinical effects of low-dose interleukin-2 across 11 autoimmune diseases in a single, open clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(2):209–17. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 38. Tchao N, Gorski KS, Yuraszeck T, et al. : Amg 592 Is an Investigational IL-2 Mutein That Induces Highly Selective Expansion of Regulatory T Cells. Blood. 2017;130(Suppl 1):696 Reference Source 28798058 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Saxena A, Khosraviani S, Noel S, et al. : Interleukin-10 paradox: A potent immunoregulatory cytokine that has been difficult to harness for immunotherapy. Cytokine. 2015;74(1):27–34. 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.10.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Galeazzi M, Bazzichi L, Sebastiani GD, et al. : A phase IB clinical trial with Dekavil (F8-IL10), an immunoregulatory 'armed antibody' for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, used in combination wiIh methotrexate. Isr Med Assoc J. 2014;16(10):666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Verma R, Balakrishnan L, Sharma K, et al. : A network map of Interleukin-10 signaling pathway. J Cell Commun Signal. 2016;10(1):61–7. 10.1007/s12079-015-0302-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Maini RNPH, Breedveld PC: Hu lL-10 in subjects with active rheumatoid arthritis (I&A): phase I and cytokine response study. Arthritis Rheum; Abstract Supplement of National Scientific Meeting; Washington,1997;224. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Galeazzi M, Sebastiani G, Voll R, et al. : Dekavil (F8IL10) – update on the results of clinical trials investigating the immunocytokine in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77(2):603–604. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-eular.5550 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nanki T, Imai T, Kawai S: Fractalkine/CX3CL1 in rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2017;27(3):392–7. 10.1080/14397595.2016.1213481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tanaka Y, Takeuchi T, Yamanaka H, et al. : OP0223 EFFICACY AND SAFETY OF E6011, AN ANTI-FRACTALKINE MONOCLONAL ANTIBODY, IN MTX-IR PATIENTS WITH RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(Suppl 2):188 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.1671 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ridgley LA, Anderson AE, Pratt AG: What are the dominant cytokines in early rheumatoid arthritis? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30(2):207–14. 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 47. Cavalli G, Dinarello CA: Treating rheumatological diseases and co-morbidities with interleukin-1 blocking therapies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(12):2134–44. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baslund B, Tvede N, Danneskiold-Samsoe B, et al. : Targeting interleukin-15 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a proof-of-concept study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(9):2686–92. 10.1002/art.21249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bridgewood C, Watad A, Cuthbert RJ, et al. : Spondyloarthritis: new insights into clinical aspects, translational immunology and therapeutics. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30(5):526–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 50. Baker KF, Isaacs JD: Novel therapies for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: What can we learn from their use in rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis? Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(2):175–87. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 51. Kragstrup TW, Andersen T, Heftdal LD, et al. : The IL-20 Cytokine Family in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Spondyloarthritis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2226. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Šenolt L, Leszczynski P, Dokoupilová E, et al. : Efficacy and Safety of Anti-Interleukin-20 Monoclonal Antibody in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Randomized Phase IIa Trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(6):1438–48. 10.1002/art.39083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yellin M, Paliienko I, Balanescu A, et al. : A phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the efficacy and safety of MDX-1100, a fully human anti-CXCL10 monoclonal antibody, in combination with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(6):1730–9. 10.1002/art.34330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Du FH, Mills EA, Mao-Draayer Y: Next-generation anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies in autoimmune disease treatment. Auto Immun Highlights. 2017;8(1):12. 10.1007/s13317-017-0100-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 55. Damjanov N, Tlustochowicz M, Aelion J, et al. : Safety and Efficacy of SBI-087, a Subcutaneous Agent for B Cell Depletion, in Patients with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis: Results from a Phase II Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(12):2094–100. 10.3899/jrheum.160146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Genovese MC, Fleischmann RM, Greenwald M, et al. : Tabalumab, an anti-BAFF monoclonal antibody, in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(9):1461–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hepburn TW, Totoritis MC, Davis CB: Antibody-mediated stripping of CD4 from lymphocyte cell surface in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42(1):54–61. 10.1093/rheumatology/keg030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. van Vollenhoven RF, Keystone EC, Strand V, et al. : Efficacy and safety of tregalizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate: results of a phase IIb, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(4):495–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 59. Finch R, Sostelly A, Sue-Ling K, et al. : OP0224 RESULTS OF A PHASE 2 STUDY OF RG6125, AN ANTI-CADHERIN-11 MONOCLONAL ANTIBODY, IN RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS PATIENTS WITH AN INADEQUATE RESPONSE TO ANTI-TNFALPHA THERAPY. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(Suppl 2):189 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.3028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Schmid AS, Neri D: Advances in antibody engineering for rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019;15(4):197–207. 10.1038/s41584-019-0188-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 61. Steeland S, Vandenbroucke RE, Libert C: Nanobodies as therapeutics: big opportunities for small antibodies. Drug Discov Today. 2016;21(7):1076–113. 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kontermann R: Dual targeting strategies with bispecific antibodies. MAbs. 2012;4(2):182–97. 10.4161/mabs.4.2.19000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Neri D: Antibody-Cytokine Fusions: Versatile Products for the Modulation of Anticancer Immunity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7(3):348–54. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 64. Fleischmann R, De Bruyn S, Duby C, et al. : A Novel Individualized Treatment Approach in Open-Label Extension Study of Ozoralizumab (ATN-103) in Subjects with Rheumatoid Arthritis On a Background of Methotrexate. Arthritis Rheumatol. ACR meeting, abstract number 1311.2012. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 65. Holz JB, Sargentini-Maier L, de Bruyn S, et al. : OP0043 Twenty-Four Weeks of Treatment with a Novel Anti-IL-6 Receptor Nanobody® (ALX-0061) Resulted in 84% ACR20 Improvement and 58% DAS28 Remission in a Phase I/Ii Study in RA. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;72(Suppl 3):A64.1–A64. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-eular.248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Dörner T, Weinblatt M, Beneden KV, et al. : FRI0239 Results of a phase 2b study of vobarilizumab, an anti-interleukin-6 receptor nanobody, as monotherapy in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(Suppl 2):575 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-eular.3746 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Fischer JA, Hueber AJ, Wilson S, et al. : Combined inhibition of tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin-17 as a therapeutic opportunity in rheumatoid arthritis: development and characterization of a novel bispecific antibody. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(1):51–62. 10.1002/art.38896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Khatri A, Klünder B, Peloso PM, et al. : Exposure-response analyses demonstrate no evidence of interleukin 17A contribution to efficacy of ABT-122 in rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(2):352–60. 10.1093/rheumatology/key312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 69. Kloppenburg M, Peterfy C, Haugen IK, et al. : Phase IIa, placebo-controlled, randomised study of lutikizumab, an anti-interleukin-1α and anti-interleukin-1β dual variable domain immunoglobulin, in patients with erosive hand osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(3):413–20. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 70. Fleischmann RM, Bliddal H, Blanco FJ, et al. : A Phase II Trial of Lutikizumab, an Anti-Interleukin-1α/β Dual Variable Domain Immunoglobulin, in Knee Osteoarthritis Patients With Synovitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(7):1056–1069. 10.1002/art.40840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 71. Cheung TT, McInnes IB: Future therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis? Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39(4):487–500. 10.1007/s00281-017-0623-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 72. Virtanen A, Haikarainen T, Raivola J, et al. : Selective JAKinibs: Prospects in Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases. BioDrugs. 2019;33(1):15–32. 10.1007/s40259-019-00333-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 73. Dörner T, Strand V, Cornes P, et al. : The changing landscape of biosimilars in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(6):974–82. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Aletaha D, Smolen JS: Diagnosis and Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Review. JAMA. 2018;320(13):1360–72. 10.1001/jama.2018.13103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 75. Koopman FA, Maanen MA, Vervoordeldonk MJ, et al. : Balancing the autonomic nervous system to reduce inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. J Intern Med. 2017;282(1):64–75. 10.1111/joim.12626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 76. Frank-Bertoncelj M, Klein K, Gay S: Interplay between genetic and epigenetic mechanisms in rheumatoid arthritis. Epigenomics. 2017;9(4):493–504. 10.2217/epi-2016-0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 77. Filková M, Jüngel A, Gay RE, et al. : MicroRNAs in rheumatoid arthritis: potential role in diagnosis and therapy. BioDrugs. 2012;26(3):131–41. 10.2165/11631480-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. van Vollenhoven RF, Nagy G, Tak PP: Early start and stop of biologics: has the time come? BMC Med. 2014;12: 25. 10.1186/1741-7015-12-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. van Steenbergen HW, da Silva JAP, Huizinga TWJ, et al. : Preventing progression from arthralgia to arthritis: targeting the right patients. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14(1):32–41. 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Hilliquin S, Hugues B, Mitrovic S, et al. : Ability of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs to prevent or delay rheumatoid arthritis onset: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(8):1099–1106. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 81. Gerlag DM, Safy M, Maijer KI, et al. : Effects of B-cell directed therapy on the preclinical stage of rheumatoid arthritis: the PRAIRI study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(2):179–85. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 82. Pozsgay J, Szekanecz Z, Sármay G: Antigen-specific immunotherapies in rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13(9):525–37. 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 83. Pfeifle R, Rothe T, Ipseiz N, et al. : Regulation of autoantibody activity by the IL-23-T H17 axis determines the onset of autoimmune disease. Nat Immunol. 2017;18(1):104–13. 10.1038/ni.3579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation