Abstract

Current conceptual models for examining the production of risk and harm (e.g. syndemics, ‘risk environment’) in substance use research have been fundamental in emphasizing broader environmental factors that shape health outcomes for people who use drugs (PWUD). However, the application of these frameworks in ways that highlight nuance and complexity has remained challenging, with much of this research focusing on select social positions (e.g. race, gender) and social-structural factors (e.g. poverty, drug policies). It is crucial that we move to better accounting for these relations in the context of substance use research to enhance equity in research and ensure understanding of diverse and complex needs. Building on the risk environment framework and complementary approaches, this article introduces the ‘intersectional risk environment’ as an approach to understanding the interconnected ways that social locations converge within the risk environment to produce or mitigate drug-related outcomes. This framework integrates a relational intersectional lens to examine how differential outcomes across populations of PWUD are produced in relation to social location and processes operating across social-structural dimensions. In doing so, the intersectional risk environment highlights how outcomes are products of processes and relations that are embodied, reflected, and challenged while situated within social, historical, and geographic contexts. Incorporating this framework into future research may improve understandings of health outcomes for PWUD and better orient structural interventions and public health approaches to address differential risks and experiences of PWUD.

Keywords: intersectionality, risk environment, health inequities, substance use, health outcomes

INTRODUCTION

The dynamic relationships among individuals, their environments, and health have been well established, with ecological approaches to public health drawing attention to how social, structural, and physical environments shape disease distribution and health inequities (Krieger, 2001; Rhodes et al., 2005; Singer, 1996). Transitions in how the production of risk and disease distribution have been conceptualized have emerged organically from research conducted with populations who use drugs, specifically in relation to HIV-related risk (Rhodes et al., 2005; Singer, 1996; Strathdee et al., 2010). This body of work has demonstrated how the social-structural conditions (e.g. social, political, and economic institutions) of individuals’ environments produce or mitigate harm, noting that such elements were unaddressed by public health approaches that had emphasized individual-focused behaviour change (Rhodes, 2002; Strathdee et al., 2010). These frameworks have thus highlighted the need for interventions that target both individual behaviours and structural factors to better address social and health inequities (Blankenship et al., 2006; Des Jarlais, 2000).

In response to ongoing critiques of individual-focused interventions, substance use research has increasingly focused on the critical need to implement interventions addressing the environmental factors of drug use locales (e.g. supervised injection sites, harm reduction housing models) (Blankenship et al., 2006; Rhodes, 2002; Singer & Clair, 2003). ‘Safer environment interventions’ – public health interventions attuned to intersecting social-structural inequities of people who use drugs (PWUD) (McNeil & Small, 2014; Rhodes et al., 2005) – have subsequently focused on factors including social and physical environments in which drug use occurs (e.g. syringe exchange, consumption sites) (Kerr et al., 2007), providing legal access to injection-related equipment (e.g. syringes, cookers) (Bluthenthal et al., 1999), and increasing connection to health and ancillary services through low-threshold models (e.g. food services, shelter, medical care) to better address factors shaping health- and drug-related outcomes (Collins et al., 2017). Earlier research examined the role of historical contexts and social locations including gender in relation to risk environments (Bourgois, Prince, & Moss, 2004; Measham, 2002), race (Maher, 2004), and socio-economic status (Moore, 2004) in shaping health and drug outcomes.

More recently, approaches providing a more ontologically-oriented way of thinking about drug-related outcomes have been implemented within addictions research to examine the relational and material aspects of drug use (e.g. Duff, 2010, 2013; Fraser, 2013; Fraser, Moore, & Keane, 2014; Ivsins & Marsh, 2018; Vitellone, 2017). This work has focused on processes, relations, and actions that occur between places, technologies, materials, and subjects, and bring these elements into being (Duff, 2014; Rhodes, 2018), and can be understood as distinct from other social-ecological approaches. Importantly, relational-material and ecological approaches have made profound contributions to how drug-related outcomes are conceptualized and addressed, with more recent ontologically-oriented approaches being able to emphasize relational dynamics within intersectionality. However, the application of these models across disciplines, and in ways that highlight nuance and complexity, has remained challenging. In particular, much research taking up ecological risk environment approaches have focused on a single social position (e.g. race, gender) and social-structural factors (e.g. drug policies, poverty), and has not fully elucidated relations across these dimensions. As such, there is a need to develop ways to operationalize a socially-oriented framework that accounts for the relations across heterogeneous factors shaping drug-related risks and outcomes, while also providing direction to policy makers and researchers in applied disciplines.

It is at this juncture that we seek to articulate intersectionality as a relational approach to discern the interconnected ways in which health- and drug-related outcomes are produced in relation to processes operating across political, social, physical, and economic dimensions, and in connection to social location, or the groups to which people belong given overlapping systems of oppression and privilege (e.g. race, gender, sexuality). It is not our intent to propose an additional ontology of drug use and risk, but rather to extend the drug use risk environment by integrating the relational approach of intersectionality. Although the risk environment framework accounts for multi-level complexity and recursive relationality, it has been applied in ways that have fallen short of fully engaging with drug-related risks and health outcomes as relational matters that are experienced differently across drug-using populations. We aim to operationalize these aspects through an intersectional lens, which has significant implications for developing public health approaches that better account for complexity between and within groups to more broadly address inequities.

In what follows, we first define the risk environment and intersectionality frameworks, examining how these approaches have been used to assess health inequities and disease distribution. We then explore the relationality of particular elements that compose the intersectional risk environment, and highlight how this framework may provide deeper insight into the disparate ways in which individuals experience risk and health outcomes. In doing so, we emphasize how examining social locations within the context of social-structural and historical milieus throughout the research process is critical to better understanding and addressing health inequities. We then offer several suggestions for how to operationalize the intersectional risk environment framework in both research and policy.

The risk environment – a multi-level approach to harm reduction

The risk environment framework has been the most prominent ecological model for substance use research, having originally developed to assess HIV-related risk for PWUD (Rhodes et al., 2012). At its most basic rendition, the risk environment is characterized as the social or physical space in which risk and harm are produced or mitigated by the interplay of factors exogenous to the individual (Rhodes, 2002). Made up of four environments (social, political, economic, and physical) operating across the micro- (immediate or institutional) and macro- (societal) levels, this framework broadens responsibility of risk production to encompass social and political structures and systems (Rhodes, 2002).

As outlined in Table 1, micro- and macro-level environmental factors of the risk environment (e.g. peer relationships, policing practices, drug use settings) have been identified as critical to shaping risk and protective networks, decision-making, and the distribution of harm among populations (Bluthenthal et al., 1999; Cooper, Wypij, & Krieger, 2005; Shannon et al., 2008; Strathdee et al., 2008, 2015). Although divided within the risk environment framework, micro- and macro-environmental factors intersect, including across levels of influence, and are constantly interacting with each other in dynamic ways to produce or reduce drug-related risks and outcomes (Rhodes et al., 2005). As such, this heuristic serves to structure analyses by providing a framework through which the social implications of risk can be situated in relation to context, rather than demarcating causal pathways.

Table 1:

Environmental contexts of the risk environment

| Micro-environment | Macro-environment | |

|---|---|---|

| Social | • Gendered power relations • Dynamics of assisted injection • Drug-related stigma in interactions with health care professionals • Violence and interpersonal conflicts • Local policing practices and crackdowns • Peer group dynamics and social norms |

• Gendered inequities and gendered risk • Stigmatization and marginalization of PWUD • Racial or ethnic inequalities • Public discourses around public health, drug use, and welfare policies |

| Physical | • Drug use settings and characteristics (e.g. supervised injection facilities, public spaces) • Sex work locations • Homelessness and housing instability Neighbourhood deprivation, urban development, and spatial inequalities • Exposure to violence or trauma • Prisons and incarceration |

• Drug trafficking and distribution routes • Geographic population shifts (e.g. neighbourhood and population mixing) • Population mobility and cross border migration |

| Economic | • Cost of living (e.g. drug-related costs, health treatments, housing costs) • Sex trade or sex work engagement • Lack of income generation and employment opportunities • Food insecurity |

• Investment in health and social services infrastructure • Growth of informal economies • Investment in social housing • Criminal justice expenditures |

| Policy | • Access to low threshold and social housing • Abstinence-only drug policies and drug criminalization in healthcare settings • Coverage and availability of harm reduction services • Operating regulations at supervised injection facilities • Local policing practices and crackdowns |

• National and international drug laws • Policies and laws for harm reduction programs and services • Policies and laws criminalizing sex work • Universal access to healthcare • Laws governing protection of human rights • Policies and laws governing pregnancy and drug use for women who use drugs |

While risk environments constrain agency, PWUD actively create, adapt, and embody risk environments through daily practices (Bourdieu, 1990; Duff, 2007; Rhodes et al., 2012). As such, the risk environment framework underscores the dynamic and relational interaction between individuals and their environments (Rhodes, 2009; Rhodes et al., 2005). This process of structuration, in which social systems and structures and individuals are engaged in a dynamic interplay and are thus not independent of each other (Giddens, 1984), positions PWUD as active participants within risk environments who both embody and shape risk environments through everyday practices (Bourdieu, 1990; Boyd et al., 2018). However, the amount of agency one can enact within a risk environment is influenced by one’s level of structural vulnerability (Rhodes et al., 2012). Structural vulnerability is a positionality resulting from an individual’s location within a social hierarchy due to intersecting social (e.g. sexism, racism) and structural (e.g. poverty, drug criminalization) inequities that render particular populations more susceptible to social suffering (Quesada, Hart, & Bourgois, 2011). As such, structural vulnerability can mediate agency by restricting structurally vulnerable individuals’ (e.g. women, sex workers) ability to engage in risk-reduction practices and can be compounded by interventions lacking environmental supports (e.g. low-threshold programming) (McNeil et al., 2015), thus intensifying influences on health (Rhodes et al., 2012).

The risk environment has provided a valuable heuristic for analyzing the impact of social-structural factors on health outcomes of PWUD across a variety of spaces (e.g. prisons, hospitals, healthcare services) (McNeil et al., 2014c; Strathdee et al., 2015). However, it has been under-theorized and largely applied in a way that overlooks the complexities and inequities experienced across groups of PWUD. In doing so, the ecological risk environment has been used in a way that essentializes and homogenizes PWUD by obscuring the ways that different individuals are impacted by social and structural forces more so than others given their social locations. Notably, a small body of research has aimed to advance the existing risk environment framework by examining how experiences of health-outcomes are heterogeneous within populations who use drugs based on, for example, race (Cooper et al., 2016b). This work has made important contributions to examining intragroup differences, drawing particular attention to how neighbourhood factors such as distribution of economic advantage, law enforcement surveillance, and proximity to harm reduction services can increase health harms for racialized persons who inject drugs (Cooper et al., 2016a, 2016c).

However, there remains a need to focus on the multidimensional and relational processes and interactions occurring between individuals, systems, places, and objects across specific socio-historical contexts, and how these create heterogeneous health and drug outcomes. Understanding these complexities is critical to developing context-specific policies (Blankenship et al., 2006; Rhodes et al., 2005) and structural interventions that create ‘enabling environments’ for risk reduction for specific populations (Duff, 2010), and can better reduce health and social inequities.

Intersectionality and public health

The intersectional paradigm highlights the complexity of human lives and experiences by emphasizing how social locations are comprised of intersecting, fluid, and multiple identities that cannot be reduced or separated (Collins, 1990; Crenshaw, 1991). As such, intersectionality highlights how identity categories (e.g. race, gender) are often conflated within mainstream discourses, obscuring differences occurring across and within particular groups. As such, an intersectional approach examines the intersections of multiple axes of oppression and privilege (e.g. gender, ethnicity, ability), positing that what is produced at these intersections is more than what is produced by each piece discretely (Crenshaw, 1991; Lorde, 1984). Examining only one dimension of an individual’s social location thus fails to accurately represent the unique ways in which they experience privilege or oppression (Crenshaw, 1991; Hooks, 1989). Notably, most intersectional scholarship does not infer that all social locations are of the same social significance, nor are they equally disadvantaged, focusing largely on marginalized individuals (Bowleg, 2012; Nash, 2008). Here, we utilize intersectionality as a general approach to identity, positing that examining all social locations (including those of privilege) can better highlight the complex and intimate connections between privilege and oppression and how these intersect to produce or mitigate harm across groups of PWUD. Moreover, within intersectionality, primacy is given to macro-level power structures which shape micro-level experiences. However, because these interactions are dynamic and socially constructed, experiences and interactions between these systems of power change over time and are shaped by place (Crenshaw, 1991).

Historically, intersectionality emerged from the examination of how Black women have been excluded from feminist and antiracist discourses, oppressed in laws and policies, and subjugated by social and economic inequities (Collins, 1990; Lorde, 1984; Roberts, 1991). More recently, intersectionality has been applied within public health to examine health inequities and distribution of health outcomes across various populations (Bowleg, 2012). In doing so, intersectionality has illustrated how traditional epidemiological approaches (e.g. binary analytical approaches, dichotomization of sex and gender) can obfuscate the unique ways in which particular populations experience health inequities, particularly when rooted in the experiences of white, middle-class individuals (Hankivsky, 2012). For example, this body of work has used an intersectional approach to examine mental health (Morrow, Frischmuth, & Johnson, 2006), risk of HIV acquisition (Dworkin, 2005), and health-related inequities amongst lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, two-spirit, and intersex (LGBTQ2SI+) communities (Bowleg, 2012; Brotman et al., 2002).

Despite calls to incorporate intersectionality into epidemiological and public health research, there has yet to be a wide integration into mainstream research (Hankivsky, 2012). This slow application has largely been attributed to a lack of a defined methodology and the need to encompass a multitude of elements and social-structural variables (Bauer, 2014). There is thus a need to better operationalize an intersectional framework within health research. Doing so can emphasize the dynamic ways that social locations continuously emerge through social and structural processes while being (re)produced, (re)embodied, and challenged in ways that shape outcomes within specific socio-historical contexts.

The production of contexts of health – intersecting locations

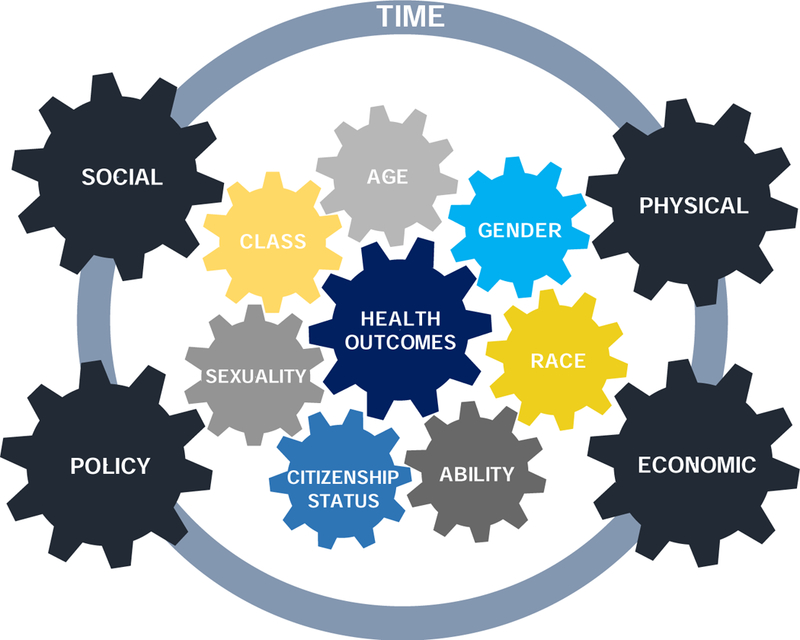

An intersectional risk environment framework encourages a social justice-oriented, critical analysis of the production of drug- and health-related outcomes through explicit attention to inequities across populations. Here, we define the intersectional risk environment as the convergence of social and structural dimensions and individuals’ intersecting social locations in ways that interact with and impact individual behaviours to produce health outcomes (see Figure 1). In this way, the intersectional risk environment is a type of situational assemblage (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987), in which relations between processes, objects, and places interact within specific social, historical, and geographic contexts to produce variegated health effects on the basis of social locations (e.g. gender, sexuality, ability). It is this situatedness that contributes to a multitude of ways in which the intersectional risk environment is embodied, reflected, reproduced, and challenged in relation to recursive interactions (Bourdieu, 2000; Giddens, 1984).

Figure 1.

The intersectional risk environment framework

How an individual enacts, embodies, and demonstrates agency in social practices that influence drug and health outcomes, however, is shaped by their intersecting social locations, which themselves are the product of structural racism, neoliberalism, gender inequities, colonial histories, among other things. The intersectional risk environment framework thus integrates a relational intersectional lens to examine the diverse ways that differential drug- and health-related outcomes are produced. While a categorical intersectional approach focuses on the relationships among social groups (e.g. working-class women, bisexual Hispanic men) and how these relationships change (McCall, 2005), it is limited in its examination of social locations as fluid categories. A relational intersectional lens seeks to tease out the complexity of such categories, positing that social locations are not fixed, but rather in a state of becoming (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987; Rhodes, 2018), entangled and shaped by social-structural dynamics. For example, dialogues (e.g. gendered power differentials), policies (e.g. punitive approaches for drug use during pregnancy), spaces (e.g. public space, home), and material elements (e.g. syringes, naloxone kit) imbue particular meaning to social locations such as gender, but by doing so, simultaneously create and reinforce gendered identities and inequalities (e.g. women as submissive, caretakers) (Butler, 1990; Hansen, 2012).

Importantly, we view risk and response to risk as situationally dependent (Bloor, 1995), but contend that these situated risks can be experienced differently based on interactions between intersecting social locations and social-structural processes. Thus, the intersectional risk environment explicitly interrogates the dynamic workings of social locations, which are simultaneously experienced, adapted, and shaped by risk environments (Bourdieu, 1977, 2000). Of note, we have removed the macro- and micro-level distinctions of the risk environment to better demonstrate the dynamic interaction between levels of social-structural influence and social locations in the production or reduction of drug-related risks and harms.

Below, we explore key social locations depicted in Figure 1, highlighting how they are not only shaped by dimensions of the drug risk environment, but intersect and reinforce one another. Although a multitude of factors converge to shape daily lives, we focus on key, or primary, social locations that are rooted in structures of inequality (e.g. gender, class, race), and how these impact health outcomes for PWUD. While secondary positions such as age are also implicated, the effects of these positions can have less of an impact on social and health outcomes. Of note, this differentiation of primary and secondary locations is not complete. Rather, we aim to provide guidance on how an intersectional risk environment approach can be implemented in ways that illuminate key axes of inequities. However, determining which social locations are defined as primary and secondary can also be context dependent, impacted by both social-structural context and specific situations. Importantly, we define many of the following categories (e.g. gender, class, race) as being socially produced, while begetting real effects in society and lived experiences.

Gender

Epidemiological studies have largely conflated biological sex and gender, concentrating on dichotomized variables to examine sex/gender-based differences in drug and health outcomes (Bowleg, 2012; Hankivsky, 2012). However, gender is fluid and relational (Butler, 1990; Schippers, 2007). As such, the bifurcation of gender minimizes the complexities of gender within drug scene settings as it overlooks socio-economic and political factors that impact the development and performance of gender throughout the life-course and over generations (Butler, 1990). Research drawing on the ecological risk environment framework has illustrated how gendered power relations and control in drug using partnerships can increase health- and drug-related risks if women are often second on the needle, require assistance injecting, and are unable to negotiate harm reduction strategies due to social-structural barriers, such as risk of violence (Bourgois et al., 2004; Rhodes et al., 2012; Sherman, Lilleston, & Reuben, 2011). Such factors have been shown to be further exacerbated by age, with young women who use drugs often at an increased risk of health and drug harms (Bourgois et al., 2004).

Recent ethnographic research integrating intersectional approaches into analyses drawing on the risk environment framework have further problematized drug scene dynamics (Boyd et al., 2018). This work has illustrated how everyday violence differentially impacted marginalized women who use drugs, with racialized and Indigenous women and transgender women most affected (Boyd et al., 2018). By focusing on relational aspects within a street-based drug scene, this research demonstrated how structural factors such as drug criminalization, colonialism, lack of housing, gender inequities, systemic racism, and prohibited assisted injection intersected in ways that shaped, and were shaped by, women’s social locations, increasing their risk of harm (Boyd et al., 2018). By drawing on aspects of intersectionality within a risk environment framework, this work utilized a social justice lens to illustrate racialized and gendered barriers that constrained access to harm reduction services within the context of a public health emergency (Boyd et al., 2018). In doing so, this research is able to add complexity to existing understandings of public health interventions by providing a more social justice-oriented understanding of drug-related risks and how risk differs within a specific socio-historical context. However, it further creates space to consider how PWUD exercise agency in contesting and changing risk environments (e.g. peer-led overdose response interventions), and how these too are influenced by, and indeed produce, social location within specific social-structural contexts. This is particularly instructive in light of drug user-led activism emerging from within communities facing multiple structural oppressions (e.g. housing instability, socio-economic marginalization) (Bardwell et al., 2018; Kennedy et al., 2019; Kerr et al., 2017; McNeil et al., 2014b).

Notably, how women’s drug use has been interpreted and stigmatized has varied over generations, shaped by gender norms and marketing campaigns, which are bound with racial and class discourses (Herzberg, 2010). For example, the regular use of benzodiazepines for middle-class white women in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was not stigmatized, but arguably ensured the maintenance of traditional gender roles and norms (e.g. passive housewife, docility) (Herzberg, 2010). However, expectations of gender roles differ for women of colour and racialized women who use drugs in western nations. Racialized women are seen as more ‘devious’ for their ‘transgressions’ of gender norms than white women, and thus suffer increased penalization under the law (e.g. child apprehensions) (Boyd, 2015). Applying an intersectional risk environment lens could further problematize the complexities resulting from the ways in which gender, race, sexuality, and ability ‘become’ through policies, and how these change over time. For example, research exploring drug treatment and drug use have described how PWUD are constructed by gendered and racialized hierarchies in ways that delineate between those who are (un)deserving of treatment (Hansen, 2017; Knight, 2017). In doing so, this work is better positioned to tease out more of the complexities surrounding social and health inequities for PWUD, and how individuals resist efforts aimed at producing and reifying inequities.

Race

A large body of research has detailed how race impacts social and health outcomes for PWUD (e.g. higher rates of HIV, geographic and structural barriers to treatment, increased incarceration rates), and intersects with socio-economic marginalization, gender, and geography in ways that produce markedly different harms (Cooper et al., 2016b; Hansen, 2017; Hansen et al., 2016; Knight, 2017). However, examining race within the socio-historical contexts in which it is constructed elucidates the dynamics that produce and reproduce it (Hall, 1980), and underscores how race intersects with social and structural environments across generations to shape health outcomes. For example, medical sociological and anthropological research has demonstrated how medical discourses and systemic discrimination are bound with race, class, and gender narratives to shape deservingness of care within healthcare settings (Hansen, 2017; Knight, 2017; Netherland & Hansen, 2016). For opioid agonist treatment programs in the United States, structural barriers (e.g. financial barriers, referral process, types of medical coverage accepted) and geographic location of services can create disparities in access to treatment options for low-income racialized persons, resulting in a higher number of racialized persons being prescribed more regulated and stigmatized maintenance therapies such as methadone (Hansen et al., 2016). As this research focused on race, geography, and income, examining these dynamics from an intersectional risk environment perspective may also discern how access to opioid agonist treatments are further complicated by gender, notions of ‘worthiness’ of care, and punitive approaches to drug use that operate within racialized class hierarchies. Importantly, an intersectional risk environment framework could also examine how such dynamics are embodied, recreated, and resisted across and among populations who use drugs, relative to their intersecting social locations across time.

Additionally, structural factors, including poverty, healthcare practices, punitive policies, and neighbourhood contexts can significantly impact drug and health outcomes for racialized PWUD (Cooper et al., 2016b). However, such factors are also rooted in historical forms of oppression (e.g. colonialism, slavery) (Crenshaw, 1991; Million, 2013), which can shape the wellbeing of individuals across generations (Sotero, 2006). Research has indicated how racialized women who use drugs are disproportionately impacted by punitive practices, which create barriers to accessing health-related services (Knight, 2017), as they overlap with disparate notions of motherhood that are racialized and classed (Hansen, 2017; Knight, 2017). Applying an intersectional risk environment framework could further discern additional pieces of the assemblage within which health inequities are rooted, and dynamics that make particular racialized populations more at risk for incarceration (Sapers, 2016; Small, 2001), drug-related harms, or other social inequities as they intersect with additional social locations.

For example, ethnographic research incorporating intersectionality within analyses rooted in an ecological risk environment framework has illustrated the variegated ways that Indigenous women experience overdose risk given racialized and gendered hierarchies, socio-economic marginalization, and housing instability which increase their interaction with police (Boyd et al., 2018). However, by situating such research within the context of colonialism, this work is able to discern how such overlapping factors create barriers to needed harm reduction services, particularly as they are largely implemented without attention to multiple needs within and across racialized populations who use drugs (Boyd et al., 2018).

While research has highlighted how racialized persons are disproportionately impacted by drug and health harms due to intersecting systems of oppression, pervasiveness of racism and ethnocentrism has perpetuated such health inequities (Allan & Smylie, 2015). Understanding how race intersects with additional social locations across environmental dimensions is imperative to addressing and mitigating health outcomes for racialized PWUD.

Ability

There is a growing appreciation of how ability influences harm for PWUD. Clinical and ethnographic studies have demonstrated how physical and mental health conditions (e.g. poor venous access, paralysis, Parkinson’s disease, depression) resulting from aging, long-term drug use, and traumatic experiences can create drug-related outcomes impacting the morbidity and mortality of PWUD (McNeil et al., 2014b; Wurcel et al., 2015). For example, PWUD who have disabilities may require assistance injecting, which is often prohibited at injection sites to minimize potential for civil or criminal liabilities (Pearshouse et al., 2007). Considering the mechanisms through which social, structural, and built environments (e.g. operational policies, accessibility of services) shape health and drug risks for PWUD with varying abilities is thus critical to addressing inequities exacerbating their risk of harm.

Medical social science research has highlighted how embodied risks related to the inability to access assistance injecting can limit engagement with needed harm reduction services for particular PWUD, reinforcing inequities and experiences of violence when injections occur in other physical spaces (e.g. alleys) with ‘doctors’ (i.e. someone who performs injections) (Fairbairn et al., 2010; McNeil et al., 2014b). For example, ethnographic research utilizing a risk environment approach more attuned to differences within highly vulnerable populations who use drugs, illustrated how particular spatial, social, and structural factors created differential risk for people needing assistance injecting (McNeil et al., 2014b). This research found that socio-economically marginalized women and people with disabilities were disproportionately impacted by socio-legal mechanism regulating injecting spaces (McNeil et al., 2014b). While this work looked more relationally at social locations in shaping health and drug outcomes, a relational intersectional risk environment lens could further disentangle how historical and social contexts (e.g. colonialism, drug-user led activism, implementation without input from PWUD, exclusion), objects (e.g. syringes, veins), and places (e.g. consumption sites, alleys, neighbourhoods) reify the marginalization of PWUD by shaping how experiences are embodied and challenged. Moreover, examining the complexities of sexuality and racialization within these contexts can elucidate the relationality of risk as social locations were at once shaping risk and ‘becoming.’

While research on assisted injection provides valuable insight into harm reduction needs for PWUD with varying abilities (e.g. McNeil et al., 2014b), there is a need to critically examine how social, physical, economic, and political environments also shape drug-related risks on the basis of social locations. Specifically, there remains a dearth of research examining the drug use practices of PWUD with varying abilities, including engagement with harm reduction services (e.g. needle exchanges, drug consumption sites) and management of drug-related risks. An intersectional risk environment framework may provide a useful lens through which to conduct this work, as it is well-positioned to consider how social-structural (e.g. interpersonal violence, discrimination), implementation (e.g. operating policies, educational materials in varying formats), and physical (e.g. mobility, physical access to services) contexts can produce or minimize inequities as they intersect with relational intersectional experiences. By drawing on these elements, harm reduction interventions, public health programming, and health and ancillary services, can better minimize health inequities and provide greater agency for PWUD with varying abilities through a social justice lens.

Sexuality

Sexuality is fluid and complex, negotiated within a heteronormative framework (Foucault, 1990; Rich, 1980) in which it is largely constrained by gender hierarchies and gender norms (Butler, 1990). As such, individuals who are or perceived as non-heteronormative are often scrutinized and confronted with discrimination and stigma (Foucault, 1990) within specific socio-historical contexts. Considering these relations within non-heteronormative and heteronormative contexts is imperative to understanding inequities that can develop for PWUD. For example, heteronormative framings can implicate health-related outcomes for PWUD, with research demonstrating how stigma experienced in health care settings (e.g. homophobia) can deter engagement for LGBTQ2SI+ persons who use drugs (Lombardi, 2007) and undermine needed care due to binary approaches to sexuality (Hughes, Szalacha, & McNair, 2010). A critical policy analysis elucidated how alcohol and other drug policies in Australia draw on heteronormative and gendered frameworks that ‘create’ LGBTQ2SI+ communities as ‘at risk’ thereby removing their agency and problematizing their drug use (Pienaar et al., 2018). Using an intersectional risk environment framework can draw further attention to the nuanced ways in which individuals embody, resist, and adapt these experiences through the negotiation of their sexuality in relation to social-structural dynamics, such as racialization, socio-political environment, and social relationships.

Moreover, spaces in which harm reduction services are accessed, such as treatment centres and injection facilities, as well as approaches to such services, have historically been established through a heteronormative lens that does not adequately consider other identities (Pinkham, Stoicescu, & Myers, 2012). The effects of such oversights can create barriers to engagement for particular populations, particularly if such spaces reinforce heteronormative roles (Boyd et al., 2018), such as women as ‘caretakers’ or men as more aggressive. Additionally, structural policies and programming that fail to consider the specific needs of LGBTQ2SI+ persons can be further barriers for engagement and exacerbate experiences of discrimination and stigma in health and ancillary service settings (Lombardi, 2007). Discrimination and stigma can further contribute to an increased risk of violence and trauma for LGBTQ2SI+-identifying PWUD (Balsam et al., 2004). Not only can these interactions increase drug use, but they can also exacerbate adverse health outcomes including social isolation and depression (Ritter, Matthew-Simmons, & Carragher, 2012). However, by taking a more ecological approach with distinct categories, rather than addressing the complex entanglements through which social locations like sexuality are created and redefined, this work may overlook how particular structural dynamics (e.g. national policies, healthcare access) can remake sexuality and individual’s experiences of sexuality as it intersects with additional socio-economic locations (e.g. gender, race, age).

A relational intersectional lens also underscores how a conflation of sexuality into dichotomous categories (e.g. gay/lesbian or heterosexual/straight) can fail to capture the interconnecting social dimensions of sexuality that shape health risks (Hughes et al., 2010) and how sexuality can change over time. It is important to note, however, that there remains limited research exploring the variegated drug-related risks experienced by LGBTQ2SI+ persons. Using an intersectional risk environment framework to guide additional research that explores how LGBTQ2SI+ persons experience health and drug outcomes in relation to factor such as structural racism, colonialism, socio-political environments is imperative to providing tailored services to better address needs.

Class

Structural factors associated with class and income inequality (e.g. neighbourhood underdevelopment, policies dictating welfare rates, insurance premiums, rural settings) can influence drug and health outcomes. However, income inequality is inherently racialized and gendered, and overlaps with criminal justice practices (e.g. mass incarceration, drug-related arrests) in ways that can increase health risks (e.g. HIV) for PWUD (Friedman et al., 2016), with poor, racialized women disproportionately impacted (Sapers, 2016; Swavola, Riley, & Subramanian, 2016). These dynamics heighten risk of violence for those low-income individuals who turn to informal and illegal forms of work (e.g. sex work, recycling, drug dealing) while also amplifying health and social inequities (Boyd et al., 2018; Strathdee et al., 2015; Tempalski & McQuie, 2009). However, epidemiological research has highlighted how socio-economic factors intersect with race to produce heterogeneous health outcomes across low-income populations (Cooper et al., 2005; Friedman et al., 2016; Strathdee et al., 2010). For example, low-income, racialized neighbourhoods are often targeted with increased levels of policing and surveillance (e.g. drug crackdowns, police sweeps), which has significant implications for harm reduction practices (e.g. shared syringes, rushed injections) and risk of HIV transmission and acquisition for PWUD (Cooper et al., 2005; Strathdee et al., 2010). An intersectional risk environment framework can illustrate how larger inequities related to factors such as gender, race, and sexuality are inextricably linked with class and thus cannot be meaningfully separated. As such, this framework holds promise for providing more complex analyses by accounting for these interconnected and fluid elements as they relate to class, while underscoring the ways individuals embody, challenge, and create these same dynamics.

Further research has detailed how class and income inequality also intersect with gender and ability to produce heterogeneous health and social outcomes for low-income populations. However, these interlocking factors are not stagnant, but change over time, within specific contexts, and with changing physical ability (Bourgois & Schonberg, 2009; McNeil et al., 2014a). For example, longitudinal ethnographic research among impoverished men with varying levels of ability has shown how men at times engage in homosocial partnerships with other men who not only help provide economically (e.g. collective purchasing and splitting of drugs, food provision), but also assist with injections (Bourgois & Schonberg, 2009). While these relationships have economic and social benefits, such marginal masculinities that are intimately linked with class can reinforce marginalization through subordination in partnerships, increased risk of violence, and limiting access to needed services (Bourgois & Schonberg, 2009; McNeil et al., 2014a).

While this work has underscored how class and other intersecting factors can ‘create’ gender and impact risk of violence (Bourgois & Schonberg, 2009; McNeil et al., 2014a), an intersectional risk environment framework could render analyses more complex by examining how policies, discourse, and social relationships can further shape health inequities within, and across, marginalized populations who use drugs with attention to how class is racialized and gendered. For example, an intersectional risk environment framing might be well-positioned to examine how risk of social- or drug-related harm is further complicated for low-income, racialized, non-binary persons by examining how gendered violence, sexuality, and ability are made, reinforced, and challenged within the context of a drug scene.

Implications and future directions

In articulating the complex, intersecting, and relational ways in which health outcomes are produced through the dynamic workings of social locations and social-structural factors, this paper has argued the need to broaden our scope of understanding risk and harm across and within populations. Like previous models of the risk environment (Rhodes et al., 2005; Strathdee et al., 2010), we emphasize the relational and dynamic interaction of factors across all environmental dimensions. However, we further expand the risk environment framework by incorporating a relational approach to intersectionality which allows us to focus on health and social inequities among and within groups. Insofar as individuals are engaged in addressing health inequities through a social justice lens, there is a need to look more holistically at the network of factors shaping experiences of risk and harm for individuals.

While extensive research has documented the impact of risk environments on PWUD (Rhodes et al., 2012; Strathdee et al., 2010), research examining relations across social location and social-structural factors in ways that highlight nuance and complexity have been more limited (Boyd et al., 2018; Collins et al., 2018; McNeil et al., 2014a). Integrating a relational intersectional approach within the drug use risk environment framework can better inform enabling environments and structural interventions attuned to inequities experienced between and within particular populations. Recent critical drug studies problematizing concepts of addiction and harm are also of particular importance, for they bring attention to how assumptions about drugs, addiction, and harm are historical, cultural, and political (Fraser, 2017; Fraser, Moore, & Keane, 2014).

Examining the multitude of ways in which social locations are impacted by, and interact with, environmental dimensions to shape health and drug outcomes can contribute to public health strategies and interventions better attuned to varying needs of individuals rendered more susceptible to harm. As such, we suggest exploring the processes that contribute to the social locations of individuals and how these are embodied, reproduced, and challenged in ways that impact health outcomes, contending that by doing so, specific interactions contributing to, and stemming from, social-structural contexts can be better understood.

Application in public health and future research

While this paper has focused primarily on PWUD, the intersectional risk environment framework has broader applicability across public health where there is concern that social locations can shape health outcomes. As such, the exact configuration of the intersectional risk environment framework can vary. Tailoring the framework to the local context to include primary and secondary social location positions more attuned to the specific issue being examined (e.g. sex work environments, chronic disease management in rural areas, healthcare access in prison) can assist in its application across populations to understand inequities within and between groups. For example, if applying the intersectional risk environment framework to chronic kidney disease treatment access in a rural region of the United States, primary social locations might include factors such as gender, race, ability, and income level. Additional dynamics including, transportation logistics, policies dictating healthcare costs and insurance premiums, and the built and social environmental may also be critical to examine, as these intersect with social locations in variegated ways. In doing so, this framework may highlight that particular social and structural dynamics (e.g. structural racism, gender hierarchies) intersect with social locations in ways that render specific rural populations (e.g. low-income, racialized women) more at risk of chronic kidney disease and comorbidities. Further, this framework could illustrate how discourses and ideals around gender performance (e.g. caretaking), class-based stigma, systemic racism, colonial histories, and income inequality create specific contexts within which individuals challenge, embody, and adapt their intersectional risk environments on the basis of their needs.

Importantly, this framework provides a tool to explicitly focus on inequities and how these are experienced, adapted, challenged, and embodied within relational contexts, which can be drawn upon to develop a research agenda. Exploring how evolving and adapting social locations within broader social and structural processes impact, reinforce, or minimize these inequities is important for implementing interventions and services that are better attuned to diverse needs. Like the more standard risk environment framework, this heuristic also acknowledges individuals’ agency. However, given the intersectional risk environment’s focus on inequities, additional research is needed that more closely examines the ways in which diverse groups enact agency within intersectional risk environments. Drawing on the extensive histories of activism within drug using communities may provide a vantage point from which to consider the diverse ways in which PWUD shape intersectional risk environments. Additionally, future research examining public health emergencies, such as the overdose crisis, should consider utilizing this framework to better assess social and health inequities rendering particular populations more susceptible to harm (Boyd et al., 2018). In doing so, this framework is well-suited to provide recommendations for public health interventions and services more attuned to diverse needs of populations within and across groups.

Methodological strategies

Existing scholarship has outlined methods for operationalizing an intersectionality approach within public health research (Bauer, 2014; Bowleg, 2012; Hankivsky, 2012). It is not our intent to reiterate this work, but rather illustrate how these methods can be utilized with an intersectional risk environment framework. While this framework can be implemented to guide research, it is also imperative to test it through application and to continue refining it, as pushing the boundaries of this approach will help it evolve. Importantly, when implementing this framework, there is need to critically reflect on how the research will be organized, what the guiding research questions will be, and what methodologies will be chosen as these elements can actively make particular populations, particular experiences, and particular health outcomes invisible if continuously overlooked in scholarship (Clatts, 2001). Utilizing an intersectional risk environment framework to guide research conceptualization and design can help build a program of research that interrogates differential risks, complexities, and relations between individuals and their environments given their social locations. Within this, there is a need to critically examine the ways in which research populations are being defined. For example, are targeted research participants defined on a single axis (e.g. people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men)? If so, what might be highlighted by altering such definitions in ways that look relationally at social locations in the production of health outcomes?

Moreover, using a multi-method design (e.g. ethnography, semi-structured interviews, epidemiological surveys, census tract data, extended case method) can provide a more dynamic analysis of risk environments as it provides multiple ways of characterizing experiences. For example, qualitative interviews allow individuals to situate themselves temporally, and demonstrate the broader environmental contexts and cultural frameworks individuals draw on to understand and locate their experiences (McAdams, 2008). They can also better elucidate relationality as qualitative interviews are well-positioned to capture affect within relational situations (Rhodes, 2018). However, understanding the broader context within which participants experience, challenge, embody, and reproduce processes, can be assessed through ethnography and the extended case method approach to ethnographic research, which can render research more complex and show how these processes are constantly ‘becoming’ (e.g. Hansen, 2017; Knight, 2017). As each method lends itself to triangulation and uncovering subtleties in experiences between groups of PWUD, utilizing multiple methods within the research process can highlight the variegated and interrelated ways that health outcomes are produced in relation to social-structural processes and social locations.

Secondly, operationalizing an intersectional risk environment framework throughout analyses is imperative to assessing intersecting and relational pathways through which individuals experience inequities. Drawing on the local context to determine primary and secondary social locations within specific social-structural contexts and situations can better explicate the nuanced ways in which people engage with, adapt, and embody intersectional risk environments. This paper, like others before it (Bowleg, 2012; Hankivsky, 2012), has underscored how dichotomizing variables, such as race, gender, and sexuality obfuscates the distinct ways such social locations shape experiences. Exploring how such social locations are continuously being created, reproduced, embodied, and challenged through relational processes can better illustrate how particular people are rendered more susceptible to inequities and how experiences are variegated. While we acknowledge that this may need to be adapted for epidemiological research given analytical constraints (Bauer, 2014), being transparent as to which certain variables were chosen over others is imperative.

Analyzing and interpreting research results using an intersectional risk environment can be instrumental in assessing additional areas contributing to health outcomes on the basis of social location. Within this, systems of power, inequality, and privilege must be interrogated, as well as cultural framings of social locations such as race, gender, and sexuality, among others. However, the particular historical moment and social locations of the researchers and research must be considered during analysis, as well as throughout the research process, as it impacts theorizing in relation to the intersectional risk environment framework.

Implications for policy and interventions

Utilizing an intersectional risk environment framework to both guide and analyze policy and public health strategies can better support social justice efforts aimed at reducing inequities between and among populations who use drugs. Policy development often takes a one-dimensional approach, which can reify the oppressive consequences of intersectional risks (Hankivsky et al., 2010) by narrowly focusing on singular social locations (e.g. gender). Understanding the nuanced ways in which intersectional risks contribute to the heterogeneity of experiences in producing health outcomes can contribute to a more inclusive approach to defining problems, developing solutions, and implementing policy and intervention strategies. Including diverse populations (i.e. a sample of individuals whose race, sexuality, gender, age, ability, and other social locations more widely represent intersections of power and oppression) to contribute to the policy-making processes or collaborating with community groups to explore the potential unintended consequences of proposed interventions (Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, 2005) also hold significant promise in developing and implementing more appropriate public health strategies. An intersectionality framing does not suggest that the multitude of factors shaping our lives hold the same social significance, as some of these factors are entrenched within social structures and relations of inequality. While there may be other factors that impact our daily lives, they may not be rooted within relations of oppression and power.

We also argue that it is necessary to expand understandings of unforeseen consequences of particular policies and public health strategies. For example, in constructing policy pertaining to overdose-related interventions, drawing from research that includes and/or collaborates with diverse groups such as racialized and gender diverse persons, youth and elders, persons with varying socio-economic statuses, as well as housed and unhoused persons, may contribute to implementing services in ways that limit barriers to access, stigma, and minimize risk. Additionally, current efforts drawing on the expertise of PWUD to address the overdose crisis through peer worker programs or peer-administered naloxone have been influential in accessing PWUD who face barriers when accessing services, while simultaneously allowing for PWUD to enact greater agency in public health efforts (Bardwell et al., 2019; Faulkner-Gurstein, 2017).

Such efforts may also be useful in shaping public discourse, as the framework provides a lens to examine how current strategies may be reifying the discrimination and stigmatization of PWUD when defining problems and solutions. Further, critically analyzing who gets to define policy and public health issues is important for assessing whether current policy approaches reinforce inequity for particular populations (Lapalme, Haines-Saah, & Frohlich, 2019). Involving diverse populations and community representatives in policy and public health dialogues can better challenge the status quo and minimize generalizations and diverse impacts are highlighted.

Conclusion

As social-structural factors are inextricably linked with and shape social locations, it is imperative to look holistically to understand the varying impacts and outcomes on health. Applying an intersectional risk environment framework allows for a deeper understanding of variegated risks within and across populations, ensuring that particular social locations are not collapsed within others creating gaps in needed care and services. In doing so, this framework offers a broader concept for addressing health inequities and can facilitate the creation of enabling environments based on the diverse needs and risks of individuals.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Presents a conceptual framework for examining differential health outcomes.

Describes how multi-level risks and social locations converge to shape health.

Suggests this approach better accounts for complexity between and within groups.

Framework informs research and initiatives to address health inequities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This research was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA044181 and R01DA043408) and the Canadian Institute of Health Research (PJT-155943, CBF-362965). Alexandra Collins is supported by a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship. Ryan McNeil is supported by a Canadian Institute of Health Research New Investigator Award and a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of Interest: None

REFERENCES

- Allan B, & Smylie J (2015). First Peoples, second class treatment: the role of racism in the health and well being of Indigenous peoples in Canada Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Balsam K, Huang B, Fieland K, Simoni J, & Walters K (2004). Culture, trauma, and wellness: a comparison of heterosexual and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and two-spirit Native Americans. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol, 10(3), 287–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell G, Fleming T, Collins A, Boyd J, & McNeil R (2019). Addressing intersecting housing and overdose crises in Vancouver, Canada: opportunities and challenges from a tenant-led overdose response intervention in single room occupancy hotels. J Urban Health, 96(1), 12–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell G, Kerr T, Boyd J, & McNeil R (2018). Characterizing peer roles in an overdose crisis: preferences for peer workers in overdose resonse programs in emergency shelters. Drug Alcohol Depend, 190, 6–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR (2014). Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc Sci Med, 110, 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship K, Friedman S, Dworkin S, & Mantell J (2006). Structural interventions: concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. J Urban Health, 83(1), 59–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloor M (1995). A user’s guide to contrasting theories of HIV-related risk behaviour. In Gabe J (Ed.), Medicine, Health and Risk: Sociological Approaches (pp. 19–30). Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal R, Kral A, Erringer E, & Edlin B (1999). Drug paraphernalia laws and injection-related infectious disease risk among drug injectors. J Drug Issues, 29(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P (1977). Outline of a theory of practice Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P (1990). The logic of practice Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P (2000). Pascalian meditations Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P, Prince B, & Moss A (2004). The everyday violence of hepatitis C among young women who inject drugs in San Francisco. Hum Organ, 63(3), 253–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P, & Schonberg J (2009). Righteous Dopefiend Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality - an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health, 102(7), 1267–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J, Collins A, Mayer S, Maher L, Kerr T, & McNeil R (2018). Gendered violence and overdose prevention sites: a rapid ethnographic study during an overdose epidemic in Vancouver, Canada. Addiction, 113(12), 2261–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd S (2015). From Witches to Crack Moms: Women, Drug Law and Policy (2nd ed.). Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brotman S, Ryan B, Jalbert Y, & Rowe B (2002). The impact of coming out on health and health care access: the experiences of gay, lesbian, bisexual and two-spirit people. J Health Soc Pol, 15(1), 1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J (1990). Gender trouble: feminism and the subversion of identity New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network. (2005). “Nothing about us without us.” Greater, meaningful involvement of people who use illegal drugs: a public health, ethnical, and human rights imperative

- Clatts MC (2001). Reconceptualizing the interaction of drug and sexual risk among MSM speed users: notes toward an ethno-epidemiology. AIDS Behav, 5(2), 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Boyd J, Damon W, Czechaczek S, Krüsi A, Cooper H, & McNeil R (2018). Surviving the housing crisis: social violence and the production of evictions among women who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Health Place, 51, 174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Parashar S, Hogg R, Fernando S, Worthington C, McDougall P, … McNeil R (2017). Integrated HIV care and service engagement among people living with HIV who use drugs in a setting with a community-wide treatment as prevention initiative: a qualitative study in Vancouver, Canada. J Int AIDS Soc, 20(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P (1990). Black feminist thought: knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment Boston: Unwin Hyman. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Arriola K, Haardorfer R, & McBride C (2016a). Population-attributable risk percentages for racialized risk environments. Am J Public Health, 106(10), 1789–1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Linton S, Kelley M, Ross Z, Wolfe M, Chen Y, … National HIV Behavioral Surveillance Study Group. (2016b). Risk environments, race/ethnicity, and HIV status in a large sample of people who inject drugs in the United States. PLoS ONE, 11(3), 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Linton S, Kelley M, Ross Z, Wolfe M, Chen Y, … Paz-Bailey G (2016c). Racialized risk environments in a large sample of people who inject drugs in the United States. Int J Drug Pol, 27, 43–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Moore L, Gruskin S, & Krieger N (2005). The impact of a police drug crackdown on drug injectors’ ability to practice harm reduction: a qualitative study. Soc Sci Med, 61(3), 673–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Wypij D, & Krieger N (2005). Police drug crackdowns and hospitalisation rates for illicit-injection-related infections in New York City. Int J Drug Pol, 16(3), 150–160. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1991). Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze G, & Guattari F (1987). A Thousand Plateaus Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais D (2000). Structural interventions to reduce HIV transmission among injecting drug users. AIDS, 14(Suppl 1), S41–S46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff C (2007). Towards a theory of drug use contexts: space, embodiment and practice. Addict Res Theory, 15(5), 503–519. [Google Scholar]

- Duff C (2010). Enabling places and enabling resources: new directions for harm reduction research and practice. Drug Alcohol Rev, 29, 337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff C (2013). The social life of drugs. Int J Drug Pol, 24(3), 167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff C (2014). The place and time of drugs. Int J Drug Pol, 25, 633–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin S (2005). Who is epidemiologically fathomable in the HIV/AIDS epidemic? Gender, sexuality, and intersectionality in public health. Cult Health Sex, 7(6), 615–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn N, Small W, Van Borek N, Wood E, & Kerr T (2010). Social structural factors that shape assisted injecting practices among injection drug users in Vancouver, Canada: a qualitative study. Harm Reduct J, 7(1), 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner-Gurstein R (2017). The social logic of naloxone: peer administration, harm reduction, and the transformation of social policy. Soc Sci Med, 180, 20–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M (1990). The history of sexuality New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser S (2013). The missing mass of morality: a new fitpack design for hepatitis C prevention in sexual partnerships. Int J Drug Pol, 24(3), 212–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser S, Moore D, & Keane H (2014). Habits: remaking addiction Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S, Tempalski B, Brady J, West B, Pouget E, Williams L, … Cooper H (2016). Income inequality, drug-related arrests, and the health of people who inject drugs: reflections on seventeen years of research. Int J Drug Pol, 32, 11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A (1984). The constitution of society: outline of the theory of structuration Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall S (1980). Race, articulation, and societies structured in dominance. In O’Callaghan (Ed.),Sociological theories: race and colonialism (pp. 305–345). Paris: Unesco. [Google Scholar]

- Hankivsky O (2012). Women’s health, men’s health, and gender and health: Implications of intersectionality. Soc Sci Med, 74(11), 1712–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankivsky O, Reid C, Cormier R, Varcoe C, Clark N, Benoit C, & Brotman S (2010). Exploring the promises of intersectionality for advancing women’s health research. Int J Equity Health, 9(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen H (2012). The “new masculinity”: addiction treatment as a reconstruction of gender in Puerto Rican evangelist street ministries. Soc Sci Med, 74, 1721–1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen H (2017). Assisted technologies of social reproduction: pharmaceutical prosthesis for gender, race, and class in the white opioid “crisis”. Contemp Drug Probl, 44(4), 321–338. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen H, Siegel C, Wanderling J, & DiRocco D (2016). Buprenorphine and methadone treatment for opioid dependence by income, ethnicity and race of neighborhoods in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend, 164, 14–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg D (2010). Happy pills in America: from Miltown to Prozac Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks B (1989). Talking back Boston: South End. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, Szalacha L, & McNair R (2010). Substance abuse and mental health disparities: comparisons across sexual identity groups in a national sample of young Australian women. Soc Sci Med, 71(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivsins A, & Marsh S (2018). Exploring what shapes injection and non-injection among a sample of marginalized people who use drugs. Int J Drug Pol, 57, 72–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy M, Boyd J, Mayer S, Collins A, Kerr T, & McNeil R (2019). Peer worker involvement in low-threshold supervised consumption facilities in the context of an overdose epidemic in Vancouver, Canada. Soc Sci Med, 225, 60–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Mitra S, Kennedy M, & McNeil R (2017). Supervised injection facilities in Canada: past, present, and future. Harm Reduct J, 14(1), 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Small W, Moore D, & Wood E (2007). A micro-environmental intervention to reduce the harms associated with drug-related overdose: evidence from the evaluation of Vancouver’s safer injection facility. Int J Drug Pol, 18(1), 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight K (2017). Women on the edge: opioids, benzodiazepines, and the social anxieties surrounding women’s reporduction in the U.S. “opioid epidemic.” Contemp Drug Probl, 44(4), 301–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N (2001). Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. Int J Epidemiol, 30(4), 668–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapalme J, Haines-Saah R, & Frohlich K (2019). More than a buzzword: how intersectionality can advance social inequalities in health research. Crit Public Health

- Lombardi E (2007). Substance use treatment experiences of transgender/transsexual men and women. J LGBTQ Health Res, 3(2), 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorde A (1984). Age, race, sex and class: women redefining difference. In Sister outsider: essays and speeches (pp. 114–123). Trumansburg: Crossing Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maher L (2004). Drugs, public health and policing in Indigenous communities. Drug Alcohol Rev, 23, 249–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams D (2008). Personal narratives and the life story. In Oliver P, Robbins R, & Pervin L (Eds.), The handbook of personality, 3rd edition: theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 242–262). New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCall L (2005). The complexity of intersectionality. Signs, 30(3), 1771–1800. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Kerr T, Anderson S, Maher L, Keewatin C, Milloy M, … Small W (2015). Negotiating structural vulnerability following regulatory changes to a provincial methadone program in Vancouver, Canada: a qualitative study. Soc Sci Med, 133, 168–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Shannon K, Shaver L, Kerr T, & Small W (2014a). Negotiating place and gendered violence in Canada’s largest open drug scene. Int J Drug Pol, 25(3), 608–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, & Small W (2014). “Safer environment interventions”: a qualitative synthesis of the experiences and perceptions of people who inject drugs. Soc Sci Med, 106, 151–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Small W, Lampkin H, Shannon K, & Kerr T (2014b). “People knew they could come here to get help”: an ethnographic study of assisted injection practices at a peer-run ‘unsanctioned’ supervised drug consumption room in a Canadian setting. AIDS Behav, 18(3), 473–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Small W, Wood E, & Kerr T (2014c). Hospitals as a “risk environment”: an ethno-epidemiological study of voluntary and involuntary discharge from hospital against medical advice among people who inject drugs. Soc Sci Med, 105, 59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measham F (2002). Doing gender, doing drugs’: conceptualizing the gendering of drugs cultures. Contemp Drug Probl, 29, 335–375. [Google Scholar]

- Million D (2013). Therapeutic nations: healing in an age of Indigenous human rights Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moore D (2004). Governing street-based injecting drug users: a critique of heroin overdose prevention in Australia. Soc Sci Med, 59(1547–1557). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow M, Frischmuth S, & Johnson A (2006). Community-based mental health services in BC: changes to income, employment, and housing supports. Vancouver: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

- Nash J (2008). re-thinking intersectionality. Fem Rev, 89, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Netherland J, & Hansen H (2016). The war on drugs that wasn’t: wasted whiteness, “dirty doctors,” and race in media coverage of prescription opioid misuse. Cult Med Psychiatry, 40(4), 664–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearshouse R, Elliott R, & Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network. (2007). A helping hand: legal issues related to assisted injection at supervised injection facilities Toronto: Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network. [Google Scholar]

- Pienaar K, Murphy D, Race K, & Lea T (2018). Problematising LGBTIQ drug use, governing sexuality and gender: a critical analysis of LGBTIQ health policy in Australia. Int J Drug Pol, 55, 187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkham S, Stoicescu C, & Myers B (2012). Developing effective health interventions for women who inject drugs: key areas and recommendations for program development and policy. Adv Prev Med, 2012, 269123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada J, Hart LK, & Bourgois P (2011). Structural vulnerability and health: Latino migrant laborers in the United States. Med Anthropol, 30(4), 339–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T (2002). The “risk environment”: a framework for understanding and reducing drugrelated harm. Int J Drug Pol, 13(2), 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T (2009). Risk environments and drug harms: a social science for harm reduction approach. Int J Drug Pol, 20(3), 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T (2018). The becoming of methadone in Kenya: how an intervention’ s implementation constitutes recovery potential. Soc Sci Med, 201, 71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Singer M, Bourgois P, Friedman S, & Strathdee S (2005). The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users. Soc Sci Med, 61(5), 1026–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Wagner K, Strathdee S, Shannon K, Davidson P, & Bourgois P (2012). Structural violence and structural vulnerability within the risk environment: theoretical and methodological perspectives for a social epidemiology of HIV risk among injection drug users and sex workers. In O’Campo JR, Dunn P (Ed.), Rethinking Social Epidemiology: Towards a Science of Change (pp. 205–230). [Google Scholar]

- Rich A (1980). Compulsory heterosexuality and lesbian existence. Signs, 5(4), 631–660. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter A, Matthew-Simmons F, & Carragher N (2012). Monograph No. 23: Prevalence of and interventions for mental health and alcohol and other drug problems amongst the gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender community: a review of the literature Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DE (1991). Punishing drug addicts who have babies: women of color, equality, and the right of privacy. Harvard Law Review, 104(7), 1419–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapers H (2016). Annual report of the Office of the Correctional Investigator Ottawa. [Google Scholar]

- Schippers M (2007). Recovering the feminine other: masculinity, femininity, and gender hegemony. Theory Soc, 36(1), 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Kerr T, Allinott S, Chettiar J, Shoveller J, & Tyndall M (2008). Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Soc Sci Med, 66(4), 911–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SG, Lilleston P, & Reuben J (2011). More than a dance: the production of sexual health risk in the exotic dance clubs in Baltimore, USA. Soc Sci Med, 73(3), 475–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M (1996). A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inq Creat Sociol, 24(2), 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, & Clair S (2003). Syndemics and public health: reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Med Anthropol Q, 17(4), 423–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small D (2001). The war on drugs is a war on racial justice. Soc Res, 68, 896–903. [Google Scholar]

- Sotero M (2006). A conceptual model of historical trauma: implications for public health practice and research. J Health Dispar Res Pract, 1(1), 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee S, Hallett T, Bobrova N, Rhodes T, Booth R, Abdool R, & Hankins C (2010). HIV and risk environment for injecting drug users: the past, present, and future. Lancet, 376(9737), 268–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee S, Lozada R, Pollini R, Brouwer K, Mantsios A, Abramovitz D, … TL P (2008). Individual, social, and environmental influences associated with HIV infection among injection drug users in Tijuana, Mexico. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 47(3), 369–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee S, West B, Reed E, Moazan B, Azim T, & Dolan K (2015). Substance use and HIV among female sex workers and female prisoners: risk environments and implications for prevention, treatment, and policies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 69(1), S110–S117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swavola E, Riley K, & Subramanian R (2016). Overlooked: women and jails in an era of reform New York: Vera Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Tempalski B, & McQuie H (2009). Drugscapes and the role of place and space in injection drug use-related HIV risk environments. Int J Drug Pol, 20(1), 4–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitellone N (2017). Social science of the syringe: a sociology of injecting drug use New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]