SUMMARY

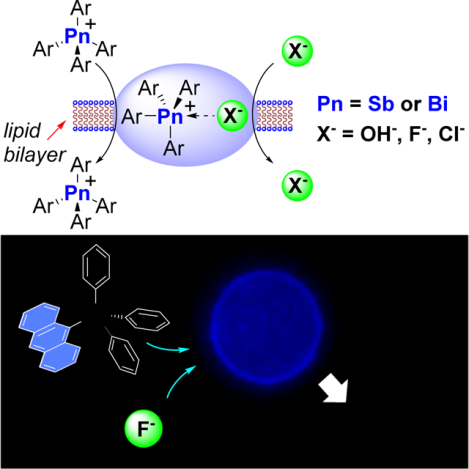

Our work on the complexation of fluoride anions using group 15 Lewis acids has led us to investigate the use of these main group compounds as anion transporters. In this paper, we report on the anion transport properties of tetraarylstibonium and tetraarylbismuthonium cations of the general formula [Ph3PnAr]+ with Pn = Sb or Bi and with Ar = phenyl, naphthyl, anthryl, or pyrenyl. Using EYPC-based large unilamellar vesicles, we show that these main group cations transport hydroxide, fluoride and chloride anions across phospholipid bilayers. A comparison of the properties of [Ph3SbAnt]+ and [Ph3BiAnt]+ (Ant = 9-anthryl) illustrates the favorable role played by the Lewis acidity of the central pnictogen element with respect to the anion transport. Finally, we show that [Ph3SbAnt]+ accelerates the fluoride-induced hemolysis of human red blood cells, an effect that we assign to the transporter-facilitated influx of toxic fluoride anions.

Keywords: anion transport, fluoride, chloride, hydroxide, human erythrocytes, hemolysis, antimony, phospholipid vesicles, cations, Lewis acids

Graphical Abstract

eTOC

This work introduces a new approach to transmembrane anion transport based on lipophilic and Lewis acidic tetraaryl-stibonuim and bismuthonium cations. The stibonium cations are particularly appealing given that they readily transport hydroxide, fluoride and chloride anions in synthetic vesicles. When combined with human erythrocytes, the most active stibonium cation uncovered in this study quickly localize in the cell membranes and induces hemolysis when fluoride is present. This effect is assigned to the transporter facilitated influx of toxic fluoride anions.

INTRODUCTION

The toxicity of fluoride at high doses derives, in part, from its enzyme inhibiting properties.1; 2 Logically, the adverse properties of these anions also originate from its ability to penetrate cells, a step likely necessary before accessing vulnerable enzymes. Bacteria equipped with naturally occurring fluoride anion channels capable of exporting the toxic anion display a greater resilience when exposed to high doses of fluoride.2–5 These findings have served as an inspiration for the development of synthetic derivatives which could be used to transport fluoride anions through cell membranes. While Matile and co-workers obtained initial evidence that synthetic ionophores based on naphthalene diimides are capable of transporting fluorideions,6;7 a team led by Gale has recently shown that strapped calix[4]pyrroles such as A behave as selective fluoride anion transporters, a property correlated to the favorable hydrogen bonds formed between the host and the anionic guest (Figure 1).8 There is also growing interest in the transport of hydroxide anions, a process which could be used to defuse pH gradients across cellular membranes.9;10 Such processes may be used to induce apoptosis, thus opening the door to applications in cancer therapy.11–15

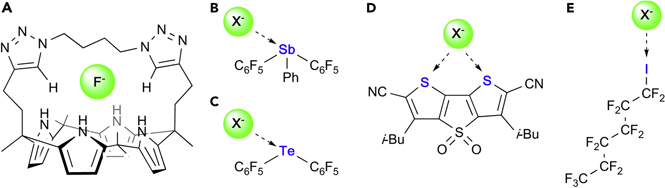

Figure 1.

Selected examples of relevant transmembrane anion transporters.

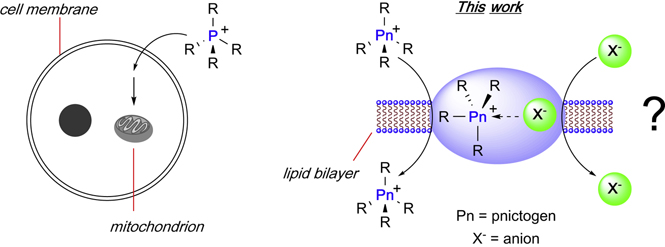

While the use of organic receptors dominates the domain of anion transport, a series of recent reports indicate that Lewis acidic main group compounds may constitute promising platforms as in the case of the pnictogen, chalcogen and halogen, bond donor derivatives B,16 C,16 D,17 and E18, which transport chloride ions through artificial lipid bilayers (Figure 1). These precedents, as well as the knowledge we have derived from our work on main group Lewis acids as anion sensors,19–22 led us to speculate that Lewis acidic pentavalent pnictogen derivatives may be potent fluoride or hydroxide ion transporters. While contemplating this idea, it occurred to us that pnictogenium cations could be appealing targets because of the known cell penetrating properties of their phosphorus congeners. Indeed, lipophilic phosphonium cations are known to quickly penetrate cell membranes, ultimately locating in the mitochondrion as a result of a negative electrostatic gradient (Figure 2).23–25 Merging the concepts of cell penetration with those of Lewis acidity at the group 15 center, we have now decided to test whether pnictogenium cations would serve as a new type of fluoride and hydroxide anion transporters (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Left: Illustration of the ability of phosphonium cations to cross cell walls and target mitochondria. Right: Graphical summary of the hypothesis tested in this stud.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The pnictogenium cations

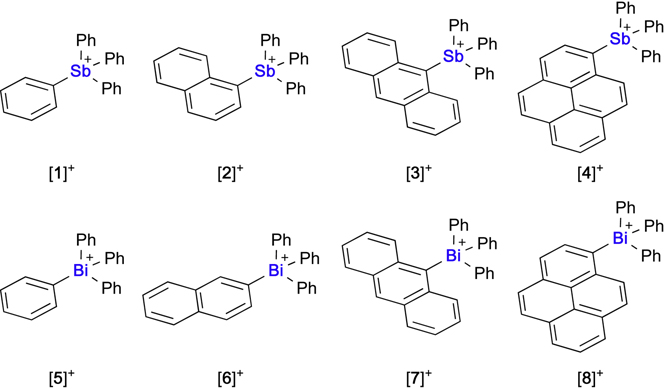

While the use of tetraarylphosphonium cations was initially tempting, we contended that the lack of Lewis acidity at the group 15 center might be problematic. Since simple stibonium or bismuthonium are known to react with fluoride anions to afford a covalent 1λ5-fluoro-stiborane19; 22; 26–28 or -bismuthane,29 respectively, we decided to focus on the use of these heavy pnictogen cations as potential transporters. The precedent that bismuth enjoys in medicine30 and the ease of preparation of tetraarylbismuthonium cations served as an additional incentive for studying bismuth-based systems.31; 32 Bearing in mind that lipophilicity might play a significant role in the transport properties of these cations, we targeted cations [1]+-[8]+ (Figure 3) which could be readily prepared using existing protocols.22;31

Figure 3.

Structures of the stibonium and bismuthonium cations investigated as anion transporters.

While [6]BF4 and [7]BF4 are new, we note that all other pnictogenium cations have been previously described.19;22;33;34 All new salts have been fully characterized with the solid-state structure of [7]BF4 being crystallographically determined (see Figure S1–10). Next, we measured the fluoride anion affinity of these cations in DMSO/H2O 98:2 (v/v) using KF as a fluoride source and UV-vis spectroscopy as a monitoring method (Scheme 1, Figure S11–18). All stibonium cations ([1]+-[4]+) display fluoride binding constants in excess of 107 M−1 indicating essentially quantitative conversion into the corresponding 1λ5-fluoro-stiborane under these experimental conditions. More progressive fluoride binding was observed with the bismuthonium cations[5]+-[8]+). In this case, fitting the resulting titration data to a 1:1 binding isotherm afforded the binding constants Ka in Table 1. With the binding constants of [5]+ and [6]+ being lower than those of [7]+ and [8]+, these results suggest a correlation between the hydrophobic character of the compounds and their fluoride ion affinity. Another important conclusion from these titration experiments is the higher Lewis acidity displayed by the antimony cations. While this conclusion may appear surprising at first, we note that it is readily reproduced by fluoride anion affinity calculations which show that the computed fluoride anion affinity of and [Ph4Bi]+ is 3.9 kcal/mol lower than that of [Ph4Sb]+. We assign this difference to the more diffuse orbitals of bismuth when compared to antimony, a factor that would weaken the covalent component of the Bi-F bond. We also note that relativistic effects in the sixth period lead to an anomalous increase of the electronegativity (χ = 2.01 for Bi vs. 1.82 for Sb)35 thereby lowering the Coulombic stabilization of the Bi-F bond. While the formation of fluoro-stiboranes by reaction of fluoride anions with stibonium cations is well understood, knowledge about the corresponding bismuth species is more limited. To confirm that the bismuthonium cations interact with fluoride, 19F NMR and 1H NMR studies were conducted (Figure S20–25). A resonance corresponding to the bismuth-bound fluorine atom was observed upon addition of [6]+, [7]+ or [8]+ to solutions of tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride (TBAF) in d6-DMSO. These 19F NMR resonances appear between −81 and −77 ppm, a range which can be compared to the value reported for pure Ph4BiF in CDCl3 (−84.6 ppm)29 or DMSO-d6 (−83.3 ppm, see Figure S19).

Scheme 1.

Binding equilibrium occurring between a pnictogenium cation and a fluoride anion. K represents the equilibrium constant.

Table 1.

Partition coefficients, fluoride binding constants and fluoride transport activity data ob-tained for [1]+-[8]+

| [Pn+] | log/Kowa | Ka (M−1)b | EC50, (mol%)c | nd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1]+ | 4.19 | >107 | 6.91(±0.70) | 1.32(±0.18) |

| [2]+ | 5.09 | >107 | 2.44(±0.01) | 0.98(±0.05) |

| [3]+ | 5.85 | >107 | 0.41(±0.05) | 0.88(±0.13) |

| [4]+ | 6.26 | >107 | 0.57(±0.07) | 1.03(±0.13) |

| [5]+e | 4.06 | 6.7(±0.2) × 103 | - | |

| [6]+ | 4.94 | 1.7(±0.1) × 104 | 6.47(±0.38) | 0.99(±0.06) |

| [7]+ | 5.55 | 1.1(±0.3) × 105 | 1.24(±0.03) | 1.28(±0.04) |

| [8]+ | 6.04 | 5.2(±1.0) × 104 | 1.38(±0.05) | 1.50(±0.08) |

Calculated octanol/water partition coefficient defined as log/Kow at 298 K.

Fluoride anion binding constant in DMSO/H2O 98:2 (v/v).

Effective concentration needed to achieve 50% transport at t=270 s (with valinomycin).

Hill coefficient derived from the fluoride efflux data (with valinomycin).

The low transport activity of this cation did not allow for Hill analysis at acceptable transporter concentrations.

Fluoride anion transport

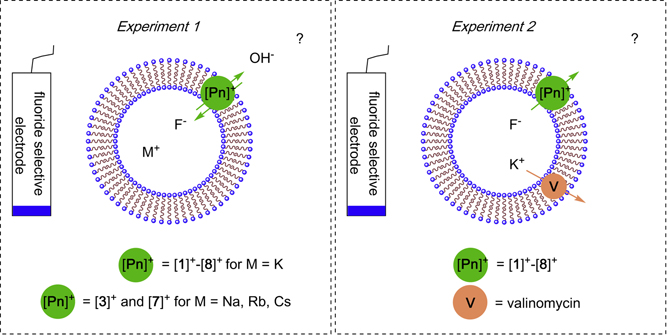

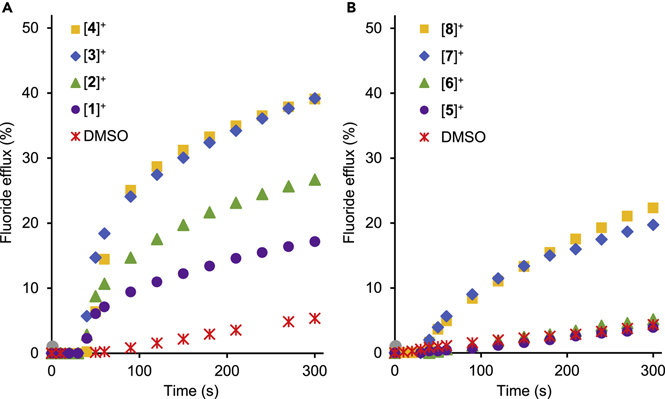

To test the transport activities of [1]+-[8]+, we designed an assay in which a DMSO solution (7 μl) of the pnictogenium cation (10 mM) was added to a solution containing fluoride-loaded large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) prepared with egg yolk phosphatidylcholine (EYPC) suspended in a buffered aqueous solution (5 mL, [EYPC] = 0.7 mM) (Figure 4, Experiment 1).8;17 Using a fluoride selective electrode, we first verified that fluoride efflux is negligible in the absence of any transporter (Figure S26). With this baseline established, we tested the effect of DMSO alone and found that it induced a modicum of transport as illustrated in Figure 5. Marked fluoride transport was detected in the presence of stibonium cations ([1]+, [2]+, [3]+ or [4]+) and the most hydrophobic derivatives [3]+ and [4]+ showed a higher activity. In the case of the bismuthonium cations, the most hydrophilic cation [5]+ as well as [6]+ showed no significant transport activity, suggesting that the higher Lewis acidity of the antimony cations is a favorable factor (Figure 5A). The importance of hydrophobicity was also noted in the case of bismuth-based cations since the anthracene and pyrene-based systems [7]+and [8]+ induced significant fluoride efflux (Figure 5B). We have also investigated the possible role played by the alkali cation and found that using NaF, RbF or CsF instead of KF leads to the same fluoride efflux. This result leads us to conclude that the fluoride transport activity of these pnictogenium cation does not depend on the nature of the alkali cation, allowing us to rule out metal-fluoride symport (Figure S27

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of selected anion transport experiments showing an idealized EYPC unilamellar vesicle. The vesicles are loaded with a 300 mM alkali metalfluoride solution (MF) buffered at pH 7.2 (10 mM HEPES) while the external medium consist of a 300 mM potassium gluconate solution also buffered at pH 7.2 (10 mM HEPES). A fluoride selective electrode is used to measure fluoride efflux; EYPC concentration: 0.7 mM.

Figure 5.

Fluoride efflux from EYPC vesicles triggered by addition of a DMSO solution (7 μl) containing (A) only DMSO, [1]+-[4]+ and (B) only DMSO, [5]+-[8]+. Transporter concentration: 2 mol% with respect to the lipid concentration. The other experimental conditions are those described for Experiment 1 in Figure 2.

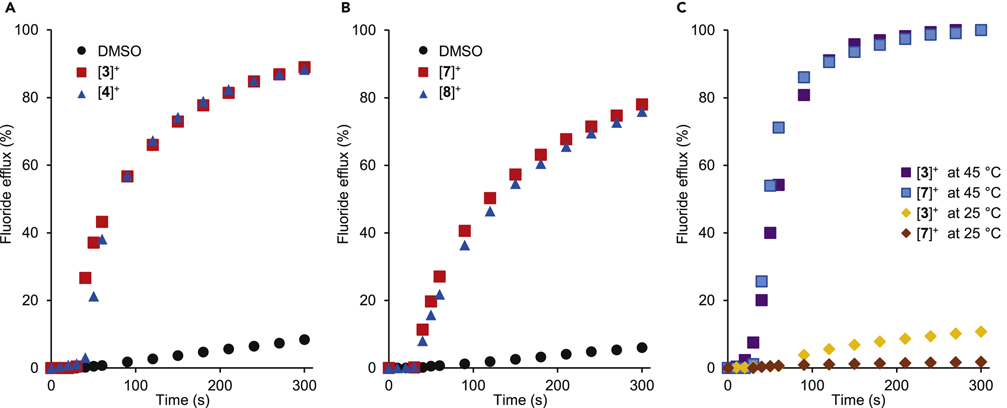

The transport activity observed in the absence of a cation transporter could be interpreted on the basis of two, possibly complementary, mechanisms. The first one would be a simple F−/OH− antiport mediated by the pnictogenium cation, which would lead to a drastic basification of the vesicle interior. Another relevant mechanism that does not involve accumulation of hydroxide ions within the vesicle would rely on the non-specific efflux of K+ and/or F− as a result of pnictogenium-induced membrane destabilization. Independently of which mechanism is at play, we reasoned that cation transport may be limiting anion efflux. For this reason, we became eager to test the effect of valinomycin, a well-known cation transporter (Figure 4, Experiment 2).36; 37 Under these conditions, we observed drastically improved fluoride anion transport, especially in the case of the most hydrophobic pnictogenium cations [3]+, [4]+, [7]+, and [8]+ (Figure 6A, 6B and Figure S28). The resulting data was modeled using the Hill equation (Figure S29–35), leading to the parameters compiled in Table 1.38–40 The first conclusion that can be derived from the fitted parameters is that all cations act as mobile carriers for the fluoride anion. Indeed, the Hill coefficients (n < 2) calculated for [2]+-[4]+ are close to unity suggesting that each cation transports one fluoride anion.41 This conclusion is consistent with the formation of 1λ5-fluoro-stiborane or -bismuthane, as the critical species involved in fluoride shuttling.29 The larger Hill coefficient observed for some of the cations could indicate the involvement of cooperative effects within the membrane where two molecules of the cationic transporter could chelate or exchange the fluoride anion.20;42 In addition, comparison of the data obtained for the antimony and bismuth compounds points to the defining influence played by the elevated Lewis acidity and fluoride anion affinity of the stibonium cations which display significantly lower EC50 values. These data indicate that the tight complexation of fluoride anions by these antimony-based systems does not impede anion catch-and-release on either side of the membrane (Figure 6A and Figure S28). The EC50 value of 0.41(±0.05) mol% (with respect to lipid concentration) measured for [3]+ can be compared to the value of 0.9 mol% obtained by the Gale group for the Calix[4]pyrrole A using POPC vesicles rather than EYPC vesicles. While the difference in the nature of the phospholipids does not allow for a more detailed comparison, the low EC50 values obtained for [3]+ validate our approach and show that readily accessible main group cations can be potent fluoride transporters. It could be argued that the transport observed in these experiments is the result of HF efflux coupled with transporter-facilitated hydroxide efflux. However, given that the fluoride concentration is 6 orders of magnitude higher that the hydroxide concentration, we see this scenario as highly unlikely.

Figure 6.

Graphs A and B: Fluoride efflux from EYPC vesicles (0.7 mM) in the presence of valinomycin (0.1 mol% with respect to the lipid concentration) Efflux was triggered by addition of a DMSO solution (7 μL) containing (A) only DMSO, [3]+ and [4]+ and (B) only DMSO, [7]+ and [8]+. Transporter concentration: 2 mol% with respect to the lipid concentration. The other experimental conditions are those described for Experiment 2 in Figure 2. Graph C: Temperature-dependent transport experiments carried out with [3]+ and [7]+ and DPPC-based vesicles.

To solidify our understanding of the role played by the lipophilicity of the pnictogenium cations, we computed the n-octanol/water partition coefficient Kow defined as Kow = [R4Bi+]octanol/[R4Bi+]water (See Figure S46).43–45 Within the antimony and bismuth series, these partition coefficients increase gradually as the size of the polycyclic aromatic substituent increases (Table 1). Interestingly, the data in Table 1 reveals that the most lipophilic pnictogenium cations [4]+ and [8]+ are not the best transporters. We interpret these results as indicating that the high lipophilicity of [4]+ and [8]+ may force it to locate in the hydrophobic part of the membrane thereby decreasing access to hydrated fluoride anions. It is also possible that the more lipophilic pyrene ring may lower transmembrane mobility, also affecting fluoride anion transport. Such effects, which have been discussed previously for hydrogen bond donor anion transporters, indicate the subtlety that one should exert when optimizing the properties of these derivatives.46 It is also possible that the more lipophilic cations can aggregate in the membrane or even partly precipitate from solution, thus lowering anion transport.47 To verify our interpretation that these cations behave as mobile fluoride ion carriers, we tested the transport properties of [3]+ and [7]+ using DPPC-based vesicles (DPPC= 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphtidylcholine) (Figure 6C). This phospholipid is known to form temperature sensitive bilayers that undergo a phase transition between a gel and a liquid at 41 °C.48;49 It has been previously suggested that channel-type transporters are less affected by this phase transition.50 However, in the case of [3]+ and [7]+, we observed a drastic decrease in transport when the temperature of the assay was lowered from 45 °C to 25 °C, indicating that transport is significantly affected by the fluidity of the bilayer. This observation asserts our interpretation that [3]+ and [7]+ behave as a mobile fluoride ion carrier rather than as a channel-type transporter.51 Additionally, to rule out the pnictogenium cation-induced destabilization of the membrane as a cause of fluoride efflux, we carried out an assay based on carboxyfluorescein, a hydrophilic fluorescent dye that does not cross phospholipid membranes and which experiences self-quenching when confined to a vesicle. This dye is used as a marker of membrane integrity since its release into the medium, as a result of membrane destabilization, is accompanied by a marked fluorescence increase. Gratifyingly, no such effects were observed when [3]+ or [7]+ were used as transporters at concentration close to their EC50 (Figure S38). The stability of the membrane in the presence of the pnictogenium cation was also assessed by dynamic light scattering (DLS) studies under the conditions employed in the electrode assay. These studies show that the scattering intensity and the average size of the vesicles remains unchanged even 30 minutes after adding cations ([3]+ or [7]+) (Figure S39), providing further evidence for the stability of the membrane.

Activity toward other anions

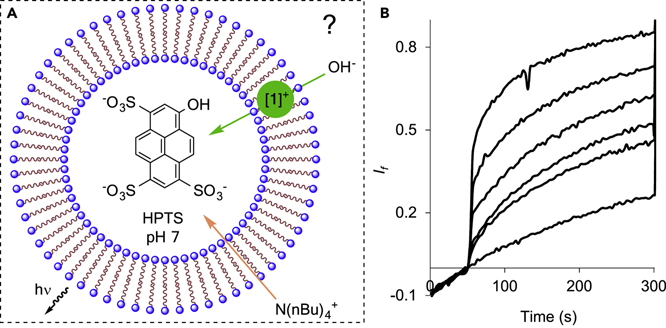

As noted, above the observation that fluoride efflux occurs in the absence of valinomycin strongly suggest the possible involvement of a OH−/F− antiport mechanism. Such a scenario is certainly supported in the case of the stibonium cations which display a high affinity for hydroxide anions.19; 52 To add credence to this interpretation, we tested the hydroxide transport properties of [1]+ using the pH-sensitive dye 8-hydroxypyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid (HPTS) which was loaded inside EYPC vesicles (Figure 7A). This cation was selected because it shows good transport properties with respect to fluoride and does not absorb at 410 and 460 nm, the two wavelengths used to excite the HPTS assay in ratiometric pH fluorescence measurement. Transport was initiated by addition of TBAOH (5 mM) to the vesicle solution (TBA = tetra-n-butyl ammonium), which resulted in a base pulse of +1.36 pH unit of the buffered solution (10 mM HEPES, starting pH 7.0).10 Hydroxide transport inside the vesicle, facilitated by the membrane permeable TBA+ cation, was manifested by a rapid change in the HPTS fluorescence profile and the normalized fractional fluorescence intensity lf(Figure 7B). An initial slope analysis of the lf vs. time data collected between 5 seconds and 20 seconds shows that higher concentrations of [1]+ correlate with an increased hydroxide influx (Figure S40–S45). This hydroxide transport experiment supports the proposal that OH−/F− antiport is at least partly responsible for the fluoride efflux observed in the electrode-monitored assay in the absence of a cation transporter. Finally, we have also tested the ability of [3]+ and [7]+ to transport chloride anions using conditions analogous to those in Experiment 2 (Figure 4) but with KCl instead of KF (Figure S36–37). Monitoring transport with a chloride selective electrode shows that these two cations are also active in the transport of chloride anions as indicated by EC50 values of 0.61(±0.04) mol% (with respect to lipid concentration) obtained for [3]+ and 3.77(±0.23) mol% (with respect to lipid concentration) obtained for [7]+. We note that these EC50 values are higher than those obtained for fluoride anions, indicating that these transporters remain selective for fluoride anions by a factor of 1.5 in the case of [3]+ and 3.0 in the case of [7]+.8

Figure 7.

Hydroxide transport experiments with [1]+ as a transporter. A: Schematic representation of the hydroxide anion transport assay involving EYPC vesicles (EYPC concentration: 0.1 mM). The vesicles are loaded with an HPTS (1 mM) / potassium gluconate (100 mM) solution buffered at pH 7.0 (10 mM HEPES) while the external medium only contains potassium gluconate and the buffer at the same concentrations and pH value. Transport is initiated by addition of TBAOH (5 mM). Hydroxide influx is monitored by measuring the fluorescence intensity of the HPTS molecule (λem = 510 nm) at two excitation wavelengths simultaneously (λex = 410nm and 460 nm). B: The graph shows the normalized fluorescence intensity as a function of time. The transporter was added 50s after the base. Concentrations of [1]+ used: DMSO, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6 mol% with respect with the lipid concentration.

Application to fluoride anion transport in biological systems

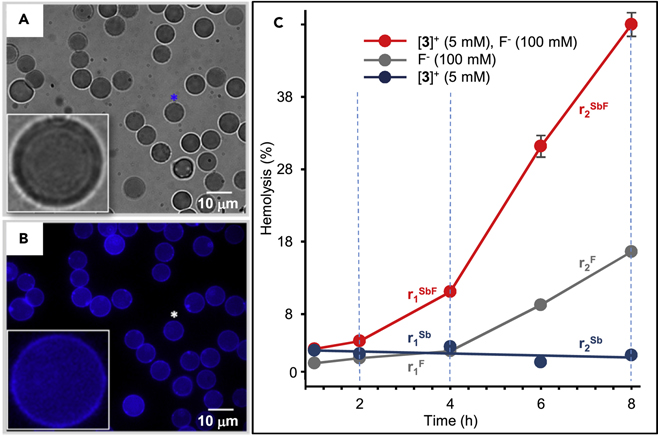

With the anion transport ability of tetraarylstibonium and tetraarylbismuthonium established in model systems, we became eager to also assess the properties of these new transporters in biological systems. In search for a model system, we were drawn by a series of reports which show that fluoride induces hemolysis in murine erythrocytes as a result of oxidative stress.53–55 We hypothesized that these toxic effects, which could be accelerated in the presence of a fluoride anion transporter, could serve as a marker of activity for the cationic transporters described in this study. To test this possibility, we suspended freshly obtained human erythrocytes in PBS buffer (6.8 % by volume) and first tested their behavior in the presence of 100 μM concentrations of [3]+ and [7]+. The experiment was monitored by microscopy which revealed a different behavior for these two cations. Indeed, while the erythrocytes remained visually unchanged upon addition of the antimony cation [3]+, the bismuth cation [7]+ induced the rapid appearance of cell ghosts indicating lysis of the erythrocytes (Figure S47). This process is so fast that no intact cells remain after 3 minutes. By contrast, the appearance of ghosts was not observed with [3]+, even after 25 minutes (Figure 8A). The toxicity of [7]+, which probably arises from the known oxidative properties of tetraarylbismuthonium cations,56; 57 shows that such bismuth-based cations are not well suited for application in biological systems. We therefore decided to focus our efforts on [3]+ which appeared to be more innocuous. As argued above, [3]+should be lipophilic, an attribute that should drive its localization in the cell membrane. We tested this possibility using fluorescence cell imaging, anticipating that the anthracene fluorophore of [3]+ would provide a detectable signal. Because of the weakly emitting nature of [3]+, we decided to carry out these experiments using a relatively high concentration of 100 μM. Images collected soon after the addition show a clear enhancement of fluorescence of the cell membranes suggesting that the transporter indeed localizes in the cell. Images taken 25 minutes after addition show an even clearer contrast with a halo defining the cell membrane of most cells (Figure 8B). These features, and in particular the observation of a halo, are characteristic of red blood cells stained by lipophilic fluorescent dyes.58;59 We confirmed the absence of auto fluorescence by imaging RBCs (0.2 % by volume) in the absence of [3]+ (Figure S48).

Figure 8.

Images A and B: bright field and fluorescence imaging of a sample of human erythrocyte (0.2 % by volume) 25 minutes after addition of [3]OTf (100 μM). The insets show a magnified view of the cell marked by an asterisk. The dark contrast of the cells in the bright field image shows that the cells are intact while the fluorescence image shows localization of [3]+ in the membrane. The DAPI filter cube (from Chroma Technology, λex/λem = 300–388, 425–488 nm) was used to obtain image B. Graph C: Hemolysis assay carried out with human erythrocytes showing the cooperative effects occurring when [3]+ and fluoride are combined. The cells were suspended in PBS buffer (HyClone). [3]+ was administered as the OTf− salt and fluoride as NaF. The rate of hemolysis are denoted as rnx with n = 1 or 2 and X = Sb, F, SbF as noted on the graph (n = 1 corresponds to the rates observed in the 2–4 h window, and n =2 to the rates observed in in the 4–8 h window; X = Sb stands for [3]+, X = F for F− and X = SbF for [3]+ and F− combined). Each experiment was carried out in triplicate and the data points represent mean percentages. The triplicated data showed high reproducibility such that some of the error bars are too small to discern.

Next, we decided to test if transporter [3]+ would increase the sensitivity of the red blood cells (RBCs) of erythrocyte towards fluoride as a result of facilitated anion transport. We investigated this possibility by carrying out a hemolysis assay, the results of which are presented in Figure 8C. We first tested the independent toxicity of the fluoride and [3]+ over the course of 8 hours. When a 100 mM concentration of fluoride is used, hemolysis does not appear to progress to any appreciable extent for the first four hours of the experiment. After this point, however, hemolysis starts increasing reaching 16.6 % after 8 hours. The long induction period may reflect the progressive influx and accumulation of fluoride inside the cell. The addition of transporter [3]+ lead to a drastically different hemolysis profile. When the transporter is used in 5 μM concentration the point taken at 2 and 4 hours shows increasing extent of hemolysis. This trend becomes even clearer at 6 and 8 hours where hemolysis reaches 31.2 % and 48 %, respectively. Analysis of the rate of hemolysis shows that the effect observed are cooperative rather than additive. For the 2–4 hours window, the hemolysis rate measured in the presence of [3]+ and fluoride (r1SbF = 3.4 %/h) is 9.7 times higher than the sum of the rates (r1Sb+r1F = 0.4 %/h) obtained when [3]+(r1Sb = −0.1 %/h) and fluoride are used alone (r1F = 0.49 %/h). It follows that the [3]+ greatly shortens the toxicity induction period, which we propose results from facilitated fluoride transport into the cell. Analysis of the data in the 4–8 hours window of the experiment provides corroborating results. Indeed, the rate of hemolysis in the presence of [3]+ and fluoride (r2sbF = 9.2 %/h) is 2.8 times higher than the sum of the rates (r2sb+r2F = 3.3 %/h) obtained when [3]+ (r2sbF = −0.1 %/h) and fluoride (r2F = 3.4 %/h) are used alone. To a lesser degree, accelerated hemolysis is also observed when [3]+ is used at a 1 μM concentration as illustrated in figure S49.

Conclusion

This paper introduces a new approach to transmembrane anion transport based on lipophilic and “fluoridophilic” pnictogenium cations. Evolved from the knowledge that phosphonium cations possess biological membrane translocating properties while their heavier analogs are Lewis acidic at the group 15 center, this approach and its preliminary implementation illustrate how the structure of the ligands and the nature of the Lewis acidic element govern the transport properties of these main group compounds. The stibonium cations are particularly appealing given that they readily transport hydroxide, fluoride and chloride anions in synthetic vesicles. Finally, we have also investigated the behavior [3]+ and [7]+ toward human erythrocytes. While the bismuthonium cation [7]+ proved to be very toxic, the stibonium cation [3]+ quickly localized in the cell membranes but did not induce notable hemolysis when used in micromolar concentrations. However, when [3]+ and fluoride were co-administered, the cells underwent accelerated hemolysis. We propose that this phenomenon results from the transporter-facilitated influx of toxic fluoride anions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

General procedure adopted for the synthesis of [5]BF4-[8]BF4:

This procedure was adapted from the literature.31 BF3 OEt2 (0.5 mmol) was transferred to a cooled (0 °C) CH2Cl2 solution (10 mL) containing triphenylbismuth difluoride (0.3 mmol) and the arylboronic acid (0.4 mmol). The resulting solution was stirred for 2 h at room temperature. An aqueous solution of NaBF4 (2.0 mmol) was then added. The resulting mixture was stirred vigorously for 30 m. The aqueous phase was separated and extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic extracts were dried over MgSO4 and evaporated under reduced pressure to afford a solid residue which was taken up in CH2Cl2 (2 mL) and precipitated with Et2O (20 mL). After filtration, the solid product was washed with two portions of Et2O (20 mL) for ([5]BF4 and [6]BF4) or THF (10 mL) (for [7]BF4 or [8]BF4).

Vesicle preparation.

The vesicles were prepared according to a previously established method.60 A thin film of the lipid was prepared by evaporation of a solution of EYPC (30 mg) dissolved in a 1:1 mixture of MeOH/CHCl3 (2 mL). This film was dried under vacuum overnight. A buffered KF solution (1 mL, 10 mM HEPES, 300 mM KF, pH 7.2) was then added, resulting in a suspension which was then subjected to nine freeze-thaw cycles (liquid N2/ 40 °C water bath), and extruded 27 times through a 200 nm polycarbonate membrane. To remove any extravesicular component, the vesicle suspension was passed through a size exclusion column (Sephadex G-50) using a buffer solution (10 mM HEPES, 300 mM KGlc, pH 7.2) as an eluent. The DPPC vesicles were prepared in a similar fashion, except that the water bath used during the freeze-thaw cycles was elevated to 50 °C. The same temperature was also used during the vesicle extrusion.

Fluoride efflux in the presence of valinomycin (EYPC and DPPC vesicles).

The following assay was adapted from a previous report.8 A solution with a final phospholipid concentration of 0.7 mM was obtained by combining an aliquot of the KF-loaded EYPC vesicles with an aqueous solution (5 mL, pH = 7.2, [HEPES] = 10 mM) containing KGlc (300 mM). The fluoride selective electrode was immersed in this solution. After the signal of the voltage had stabilized (~60 s), the measurement was initiated. At t = 0 s, valinomycin dissolved in DMSO (0.7 mM) was added to the assay such that the final valinomycin concentration was 0.1 mol %. At t = 30 s, the bismuthonium or stibonium salt ([1]-[3]OTf, [4]Br and [5]BF4-[8]BF4,) was added to the assay. At t = 300 s, 50 μL of a Triton X-100 solution (10:1:0.1 H2O:DMSO:Triton X-100 (v/v/v)) was added to lyse the vesicles triggering complete release of the fluoride cargo. The value corresponding to 100 % fluoride efflux was recorded at t = 420 s, 2 m. after lysing the vesicles. The DPPC-based assay was carried out using the same protocol and the same concentrations as those employed for the EYPC-based assay. The only difference is that the transport experiments were carried out at 25 °C and 45 °C.

RBC-based assays.

Whole blood was purchased from Gulf Coast Regional Blood Center (Houston, TX). Erythrocytes were isolated from whole blood by centrifugation for 10 m at 1,250 g. The erythrocyte pellet was resuspended in PBS (HyClone) and this washing procedure was repeated three times to remove plasma and the buffy coat. To observe membrane localization of [3]+ by fluorescence microscopy, RBCs were diluted to 2 % volume in PBS and treated with 100 μM [3]+for 5 or 25 m at 37 °C. The solution was then rapidly diluted to 0.2 % by volume in PBS and added to a glass-bottom 96-well plate for imaging. Fluorescence microscopy was performed using an inverted microscope (Olympus lX-81) with a ×100 objective as well as a heated stage (37 °C) and images were taken using a Rolera-XR back-illuminated electron multiplying CCD camera (Qimaging). For fluorescence imaging, a DAPI (λex/λem = 300–388, 425–488 nm) filter cube was used (Chroma Technology). The bright field and fluorescence images of cells were obtained using the SlideBook 4.2.0.7 software (Intelligent Imaging innovations, Inc.) For hemolysis assays, RBCs were diluted to 6.8 % volume in PBS and treated with 100 mM NaF and/or 1 or 5 μM [3]+ where indicated and ion transport was allowed to continue for 1–8h at 37°C. At each time point, intact RBCs and ghosts were sedimented by centrifugation for 2 m at 1,250 g. The supernatant containing the heme was then transferred to an optical bottom 96-well plate for measurement of free heme by measuring the absorbance (λ = 488 nm) using a GloMax-Multi+ detection system plate reader (Promega). Triplicate experiments were performed, measured and subjected to normalization. To normalize hemolysis results, a positive control was conducted in tandem by treating RBCs with 1 % Triton X-100.

Supplementary Material

The Bigger Picture.

The transport of anions through human cell membranes usually occur through channel proteins which support numerous essential processes including synaptic signal transmission, cell and organelle acidification, transepithelial salt transport, cell division as well as apoptosis. With the view to mimic and possibly one day replace such channels for therapeutic purposes, the design of small molecules that facilitate the transport of anions through artificial phospholipid membranes has become a topic of active research. This article introduces an approach to transmembrane anion transport based on readily accessible group 15 cations. The results obtained in this study demonstrate that lipophilic tetraaryl-antimony and -bismuth cations are particularly well-suited for the transmembrane transport of hard anions such as the fluoride and hydroxide anions.

Highlights.

Lewis acidic tetraaryl-stibonuim and bismuthonium cations as anion transporters

Transport of anions, including fluoride, across artificial membranes

Transporter-facilitated hemolysis of erythrocytes in the presence of fluoride anions

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the College of Science FY19 Strategic Transformative Research Program (F.P.G. and J.P.P.), the National Science Foundation (CHE-1566474, F.P.G.), the Welch Foundation Award Number (A-1423, F.P.G.), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM110137, J.P.P.), and Texas A&M University (Arthur E. Martell Chair of Chemistry, F.P.G.). We thank Dr. lou-Sheng Ke for his initial synthesis and characterization of [7]BF4.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

Crystallographic data for [7]BF4 have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and are available under the following accession number: CCDC-1863621.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Additional experimental and computational details.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Ji C, Stockbridge RB, and Miller C (2014). Bacterial fluoride resistance, Flue channels, and the weak acid accumulation effect. J. Gen. Physiol 144, 257–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stockbridge RB, Robertson JL, Kolmakova-Partensky L, and Miller C (2013). A family of fluoride-specific ion channels with dual-topology architecture. Elife 2, e01084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker JL, Sudarsan N, Weinberg Z, Roth A, Stockbridge RB, and Breaker RR (2012). Widespread genetic switches and toxicity resistance proteins for fluoride. Science 335, 233–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brammer AE, Stockbridge RB, and Miller C (2014). F−/Cl− selectivity in CLCF-type F−/H+ antiporters. J. Gen. Physiol 144, 129–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stockbridge RB, Kolmakova-Partensky L, Shane T, Koide A, Koide S, Miller C, and Newstead S (2015). Crystal structures of a double-barrelled fluoride ion channel. Nature 525, 548–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawson RE, Hennig A, Weimann DP, Emery D, Ravikumar V, Montenegro J, Takeuchi T, Gabutti S, Mayor M, Mareda J, et al. (2010). Experimental evidence for the functional relevance of anion-π interactions. Nat. Chem 2, 533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorteau V, Bollot G, Mareda J, Perez-Velasco A, and Matile S (2006). Rigid oligonaphthalenediimide rods as transmembrane anion-p slides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 128, 14788–14789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke HJ, Howe EN, Wu X, Sommer F, Yano M, Light ME, Kubik S, and Gale PA (2016). Transmembrane Fluoride Transport: Direct Measurement and Selectivity Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 16515–16522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demaurex N (2002). pH Homeostasis of Cellular Organelles. Physiology 17, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu X,Judd Luke W., Howe Ethan N.W., Withecombe Anne M., Soto-Cerrato V, Li H, Busschaert N, Valkenier H, Pérez-Tomâs R, Sheppard David N., et al. (2016). Nonprotonophoric Electrogenic Cl− Transport Mediated by Valinomycin-like Carriers. Chem 1, 127–146. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohit S, Madhusudan A, Sonal S, Bhari SM, Devi CS, and Raghu R (2015). pH Gradient Reversal: An Emerging Hallmark of Cancers. Recent Patents on Anti-Cancer Drug Discovery 10, 244–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodilla AM, Korrodi-Gregório L, Hernando E, Manuel-Manresa P, Quesada R, Pérez-Tomâs R, and Soto-Cerrato V (2017). Synthetic tambjamine analogues induce mitochondrial swelling and lysosomal dysfunction leading to autophagy blockade and necrotic cell death in lung cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol 126, 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gale PA, Perez-Tomas R, and Quesada R (2013). Anion Transporters and Biological Systems. Acc. Chem. Res 46, 2801–2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pérez-Tomás R, Montaner B, Llagostera E, and Soto-Cerrato V (2003). The prodigiosins, proapoptotic drugs with anticancer properties. Biochem. Pharmacol 66, 1447–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sessler JL, Eller LR, Cho W-S, Nicolaou S, Aguilar A, Lee JT, Lynch VM, and Magda DJ (2005). Synthesis, Anion-Binding Properties, and In Vitro Anticancer Activity of Prodigiosin Analogues. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 44, 5989–5992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee LM, Tsemperouli M, Poblador-Bahamonde AI, Benz S, Sakai N, Sugihara K, and Matile S (2019). Anion Transport with Pnictogen Bonds in Direct Comparison with Chalcogen and Halogen Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 141, 810–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benz S, Macchione M, Verölet Q, Mareda J, Sakai N, and Matile S (2016). Anion Transport with Chalcogen Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 9093–9096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jentzsch AV, Emery D, Mareda J, Nayak SK, Metrangolo P, Resnati G, Sakai N, and Matile S (2012). Transmembrane anion transport mediated by halogen-bond donors. Nat. Comm 3, 905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirai M, Myahkostupov M, Castellano FN, and Gabbaï FP (2016). 1-Pyrenyl- and 3 Perylenyl-antimony(V) Derivatives for the Fluorescence Turn-On Sensing of Fluoride Ions in Water at Sub-ppm Concentrations. Organometallics 35, 1854–1860. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirai M, and Gabbaï FP (2015). Squeezing Fluoride out of Water with a Neutral Bidentate Antimony(V) Lewis Acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 54, 1205–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirai M, and Gabbaï FP (2014). Lewis acidic stiborafluorenes for the fluorescence turn-on sensing of fluoride in drinking water at ppm concentrations. Chem. Sci 5, 1886–1893. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ke I-S, Myahkostupov M, Castellano FN, and Gabbaï FP (2012). Stibonium Ions for the Fluorescence Turn-On Sensing of F“in Drinking Water at Parts per Million Concentrations. J. Am. Chem. Soc 134, 15309–15311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith RA, Porteous CM, Gane AM, and Murphy MP (2003). Delivery of bioactive molecules to mitochondria in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 100, 5407–5412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith RAJ, Hartley RC, Cocheme HM, and Murphy MP (2012). Mitochondrial pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 33, 341–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim DY, Kim HJ, Yu KH, and Min JJ (2012). Synthesis of [F-18]-Labeled (6-Fluorohexyl)triphenylphosphonium Cation as a Potential Agent for Myocardial imaging using Positron Emission Tomography. Bioconjugate Chem. 23, 431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moffett KD, Simmler JR, and Potratz HA (1956). Solubilities of Tetraphenylstibonium Salts of Inorganic Anions. Procedure For Solvent Extraction of Fluoride Ion From Aqueous Medium. Anal. Chem 28, 1356–1356. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowen LH, and Rood RT (1966). Solvent extraction of 18F as tetraphenylstibonium fluoride. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem 28, 1985–1990. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jean M (1971). Tetraphenylstibonium fluoride. Ultraviolet measurements. Anal. Chim. Acta 57, 438–439. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ooi T, Goto R, and Maruoka K (2003). Fluorotetraphenylbismuth: A New Reagent for Efficient Regioselective α-Phenylation of Carbonyl Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 125, 10494–10495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadler PJ, Li HY, and Sun HZ (1999). Coordination chemistry of metals in medicine: target sites for bismuth. Coord. Chem. Rev 185–6, 689–709. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matano Y, Begum SA, Miyamatsu T, and Suzuki H (1998). A new and efficient method for the preparation of bismuthonium and telluronium salts using aryl- and alkenylboronic acids. First observation of the chirality at bismuth in an asymmetrical bismuthonium salt. Organometallics 17, 4332–4334. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matano Y, Begum SA, Miyamatsu T, and Suzuki H (1999). Synthesis and stereochemical behavior of unsymmetrical tetraarylbismuthonium salts. Organometallics 18, 5668–5681. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang M, Pati N, Belanger-Chabot G, Hirai M, and Gabbaï FP (2018). Influence of the catalyst structure in the cycloaddition of isocyanates to oxiranes promoted by tetraarylstibonium cations. Dalton Trans. 47, 11843–11850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matano Y, Shinokura T, Yoshikawa O, and Imahori H (2008). Triaryl(1-pyrenyl)bismuthonium salts: Efficient photoinitiators for cationic polymerization of oxiranes and a vinyl ether. Org. Lett 10, 2167–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allen LC (1989). Electronegativity is the average one-electron energy of the valence-shell electrons in ground-state free atoms. J. Am. Chem. Soc 111, 9003–9014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sokol PP, and Mckinney TD (1990). Mechanism of Organic Cation-Transport in Rabbit Renal Basolateral Membrane-Vesicles. Am. J. Physiol 258, F1599–F1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinkerton M, Steinrauf LK, and Dawkins P (1969). Molecular Structure and Some Transport Properties of Valinomycin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 35, 512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ren C, Zeng F, Shen J, Chen F, Roy A, Zhou S, Ren H, and Zeng H (2018). Pore Forming Monopeptides as Exceptionally Active Anion Channels. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 8817–8826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Busschaert N, Park SH, Baek KH, Choi YP, Park J, Howe ENW, Hiscock JR, Karagiannidis LE, Marques I, Felix V, et al. (2017). A synthetic ion transporter that disrupts autophagy and induces apoptosis by perturbing cellular chloride concentrations. Nat. Chem 9, 667–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu X, and Gale PA (2016). Small-Molecule Uncoupling Protein Mimics: Synthetic Anion Receptors as Fatty Acid-Activated Proton Transporters. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 16508–16514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bao X, Wu X, Berry SN, Howe ENW, Chang YT, and Gale PA (2018). Fluorescent squaramides as anion receptors and transmembrane anion transporters. Chem. Commun 54, 1363–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen C-H, and Gabbaï FP (2017). Fluoride Anion Complexation by a Triptycene-Based Distiborane: Taking Advantage of a Weak but Observable C-H⋯F Interaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 56, 1799–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ribeiro RF, Marenich AV, Cramer CJ, and Truhlar DG (2011). Use of Solution-Phase Vibrational Frequencies in Continuum Models for the Free Energy of Solvation. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 14556–14562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kolar M, Fanfrlik J, Lepsik M, Forti F, Luque FJ, and Hobza P (2013). Assessing the Accuracy and Performance of Implicit Solvent Models for Drug Molecules: Conformational Ensemble Approaches. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 5950–5962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vlahovic F, Ivanovic S, Zlatar M, and Gruden M (2017). Density functional theory calculation of lipophilicity for organophosphate type pesticides. J. Serb. Chem. Soc 82, 1369–1378. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saggiomo V, Otto S, Marques I, Felix V, Torroba T, and Quesada R (2012). The role of lipophilicity in transmembrane anion transport. Chem. Commun 48, 5274–5276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li H, Valkenier H, Judd LW, Brotherhood PR, Hussain S, Cooper JA, Jurček O, Sparkes HA, Sheppard DN, and Davis AP (2015). Efficient, non-toxic anion transport by synthetic carriers in cells and epithelia. Nat. Chem 8, 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dias CM, Valkenier H, and Davis AP (2018). Anthracene Bisureas as Powerful and Accessible Anion Carriers. Chem. Eur. J 24, 6262–6268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Behera H, and Madhavan N (2017). Anion-Selective Cholesterol Decorated Macrocyclic Transmembrane Ion Carriers. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139, 12919–12922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis JT, Okunola O, and Quesada R (2010). Recent advances in the transmembrane transport of anions. Chem. Soc. Rev 39, 3843–3862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koulov AV, Lambert TN, Shukla R, Jain M, Boon JM, Smith BD, Li HY, Sheppard DN, Joos JB, Clare JP, et al. (2003). Chloride transport across vesicle and cell membranes by steroid-based receptors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 42, 4931–4933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beauchamp AL, Bennett MJ, and Cotton FA (1969). Molecular structure of tetraphenylantimony hydroxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc 91, 297–301. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Agalakova NI, and Gusev GP (2012). Fluoride induces oxidative stress and ATP depletion in the rat erythrocytes in vitro. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol 34, 334–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bharti VK, and Srivastava RS (2011). Effect of Pineal Proteins at Different Dose Level on Fluoride-Induced Changes in Plasma Biochemicals and Blood Antioxidants Enzymes in Rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res 141, 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Agalakova NI, and Gusev GP (2011). Fluoride-induced death of rat erythrocytes in vitro. Toxicology in Vitro 25, 1609–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barton DHR, and Finet JP (1987). Bismuth(V) reagents in organic synthesis. Pure Appl. Chem 59, 937–946. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matano Y (2012). Pentavalent organobismuth reagents in organic synthesis: alkylation, alcohol oxidation and cationic photopolymerization. Top. Curr. Chem 311, 19–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Y, An F-F, Chan M, Friedman B, Rodriguez EA, Tsien RY, Aras O, and Ting R (2017). 18F-positron-emitting/fluorescent labeled erythrocytes allow imaging of internal hemorrhage in a murine intracranial hemorrhage model. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 37, 776–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsai L-W, Lin Y-C, Perevedentseva E, Lugovtsov A, Priezzhev A, and Cheng C-L (2016). Nanodiamonds for Medical Applications: Interaction with Blood in Vitro and in Vivo. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hennig A, Fischer L, Guichard G, and Matile S (2009). Anion-Macrodipole Interactions: Self-Assembling Oligourea/Amide Macrocycles as Anion Transporters that Respond to Membrane Polarization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 131, 16889–16895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.