Abstract

Primary central nervous system lymphoma is increasingly seen in immunocompetent patients and should be considered in any patient with multiple nervous system lesions.

Central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma can be classified into 2 categories: primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL), which includes disease limited to brain, eyes, spinal cord; and leptomeninges without coexisting or previous systemic lymphoma. Secondary CNS lymphoma (SCNSL) is essentially metastatic disease from a systemic primary site.1 The focus of this case presentation is PCNSL, with an emphasis on imaging characteristics and differential diagnosis.

The median age at diagnosis for PCNSL is 65 years, and the overall incidence has been decreasing since the mid-1990s, likely related to the increased use of highly-active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in patients with AIDS.2,3 Although overall incidence has decreased, incidence in the elderly population has increased.4 Historically, PCNSL has been considered an AIDS-defining illness.5 These patients, among other immunocompromised patients, such as those on chronic immunosuppressive therapy, are at a higher risk for developing the malignancy.6

Clinical presentation varies because of the location of CNS involvement and may present with headache, mood or personality disturbances, or focal neurologic deficits. Seizures are less likely due to the tendency of PCNSL to spare gray matter. Initial workup generally includes a head computed tomography (CT) scan, as well as a contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image (MRI), which may help direct clinicians to the appropriate diagnosis. However, there is significant overlap between the imaging characteristics of PCNSL and numerous other disease processes, including glioblastoma and demyelination. The imaging characteristics of PCNSL are considerably different depending on the patient’s immune status.7

This case illustrates a rare presentation of PCNSL in an immunocompetent patient whose MRI characteristics were seemingly more consistent with those seen in patients with immunodeficiency. The main differential diagnoses and key imaging characteristics, which may help obtain accurate diagnosis, will be discussed.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 72-year-old male veteran presented with a 2-month history of subjective weakness in his upper and lower extremities progressing to multiple falls at home. He had no significant medical history other than a thymectomy at age 15 for an enlarged thymus, which per patient report, was benign. An initial laboratory test that included vitamin B12, folate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, complete blood cell count, and comprehensive metabolic panel, were unremarkable, with a white blood cell count of 8.5 K/uL. The initial neurologic evaluation did not show any focal neurologic deficits; however, during the initial hospital stay, the patient developed increasing lower extremity weakness on examination. A noncontrast CT head scan showed extensive nonspecific hypodensities within the periventricular white matter (Figure 1). A contrast-enhanced MRI showed enhancing lesions involving the corpus callosum, left cerebral peduncle, and right temporal lobe (Figures 2, 3, and 4). These lesions also exhibited significant restricted diffusion and a mild amount of surrounding vasogenic edema. The working diagnosis after the MRI included primary CNS lymphoma, multifocal glioblastoma, and tumefactive demyelinating disease. The patient was started on IV steroids and transferred for neurosurgical evaluation and biopsy at an outside hospital. The frontal lesion was biopsied, and the initial frozen section was consistent with lymphoma; a bone marrow biopsy was negative. The workup for immunodeficiency was unremarkable. Pathology revealed high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and the patient began a chemotherapy regimen.

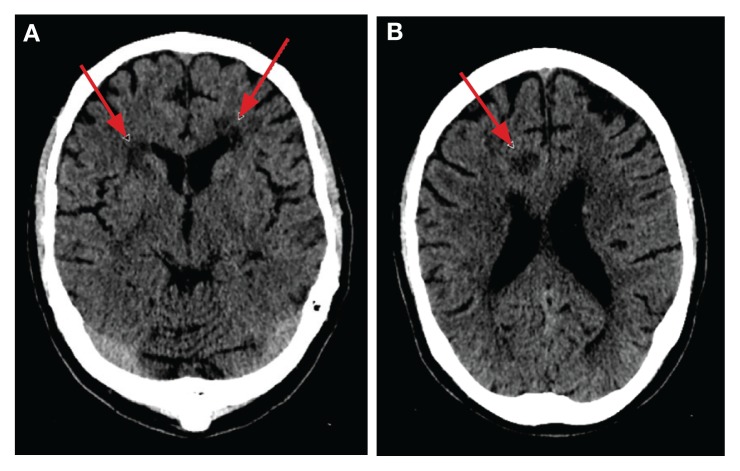

FIGURE 1.

Noncontrast head computed tomography scan showing periventricular and pericallosal hypodensity (arrows).

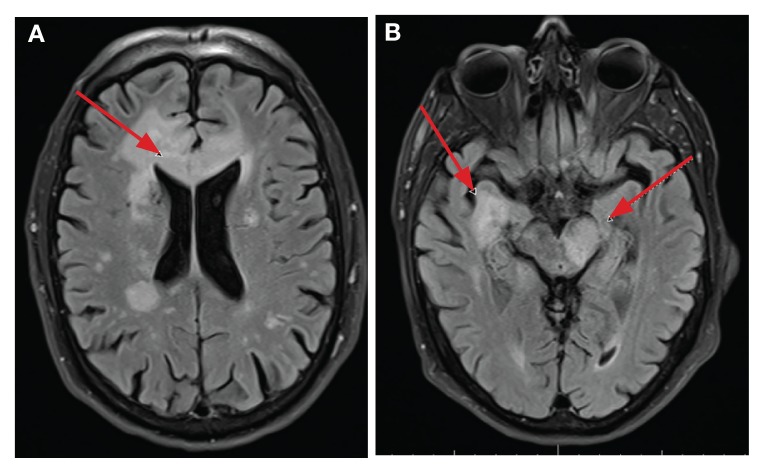

FIGURE 2.

Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain showing increased signal involving the corpus callosum, left cerebral peduncle, and right temporal lobe (arrows).

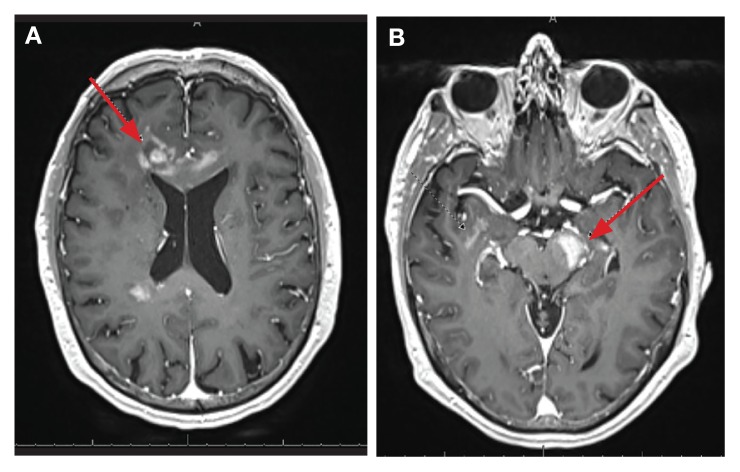

FIGURE 3.

Axial T1 postcontrast magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain showing enhancement near the corpus callosum, left cerebral peduncle, and right temporal lobe (arrows).

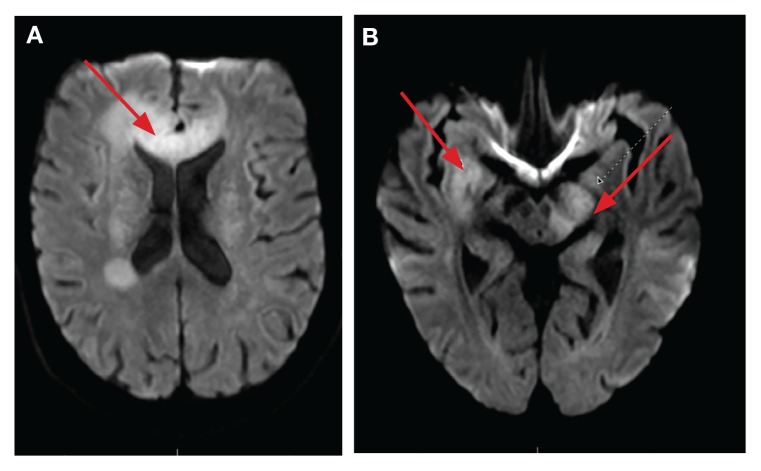

FIGURE 4.

Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain showing increased signal in the corpus callosum, left cerebral peduncle, and right temporal lobe (arrows).

DISCUSSION

The workup of altered mental status, focal neurologic deficits, headaches, or other neurologic conditions often begins with a noncontrast CT scan. On CT, PCNSL generally appears isodense to hyperdense to gray matter, but appearance is variable. The often hyperdense appearance is attributable to the hypercellular nature of lymphoma. Many times, as in this case, CT may show only vague hypodensities, some of which may be associated with surrounding edema. This presentation is nonspecific and may be seen with advancing age due to changes of chronic microvascular ischemia as well as demyelination, other malignancies, and several other disease processes, both benign and malignant. After the initial CT scan, further workup requires evaluation with MRI. PCNSL exhibits restricted diffusion and variable signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging.

PCNSL is frequently centrally located within the periventricular white matter, often within the frontal lobe but can involve other lobes, the basal ganglia, brainstem, cerebellum, or less likely, the spinal canal.7 Contrary to primary CNS disease, secondary lymphoma within the CNS has been described classically as affecting a leptomeningeal (pia and arachnoid mater) distribution two-thirds of the time, with parenchymal involvement occurring in the other one-third of patients. A recent study by Malikova and colleagues found parenchymal involvement may be much more common than previously thought.1 Leptomeningeal spread of disease often involves the cranial nerves, subependymal regions, spinal cord, or spinal nerve roots. Dural involvement in primary or secondary lymphoma is rare.

PCNSL nearly always shows enhancement. Linear enhancement along perivascular spaces is highly characteristic of PCNSL. The typical appearance of PCNSL associated with immunodeficiency varies from that seen in an otherwise immunocompetent patient. Patients with immunodeficiency usually have multifocal involvement, central necrosis leading to a ring enhancement appearance, and have more propensity for spontaneous hemorrhage.7 Immunocompetent patients are less likely to present with multifocal disease and rarely show ring enhancement. Also, spontaneous hemorrhage is rare in immunocompetent patients. In our case, extensive multifocal involvement was present, whereas typically immunocompetent patients will present with a solitary homogeneously enhancing parenchymal mass.

The primary differential for PCNSL includes malignant glioma, tumefactive multiple sclerosis, metastatic disease, and in an immunocompromised patient, toxoplasmosis. The degree of associated vasogenic edema and mass effect is generally lower in PCNSL than that of malignant gliomas and metastasis. Also, PCNSL tends to spare the cerebral cortex.8

Classically, PCNSL, malignant gliomas, and demyelinating disease have been considered the main differential for lesions that cross midline and involve both cerebral hemispheres. Lymphoma generally exhibits more restricted diffusion than malignant gliomas and metastasis, attributable to the highly cellular nature of lymphoma. 7 Tumefactive multiple sclerosis is associated with relatively minimal mass effect for lesion size and exhibits less restricted diffusion values when compared to high grade gliomas and PCNSL. One fairly specific finding for tumefactive demyelinating lesions is incomplete rim enhancement.9 Unfortunately, an MRI is not reliable in differentiating these entities, and biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. Many advancing imaging modalities may help provide the correct diagnosis of PCNSL, including diffusion-weighted and apparent diffusion coefficient imaging, diffusion tensor imaging, MR spectroscopy and PET imaging.7

CONCLUSION

With the increasing use of HAART, the paradigm of PCNSL is shifting toward one predominantly affecting immunocompetent patients. PCNSL should be considered in any patient with multiple enhancing CNS lesions, regardless of immune status. Several key imaging characteristics may help differentiate PCNSL and other disease processes; however, at this time, biopsy is recommended for definitive diagnosis.

Footnotes

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

References

- 1.Malikova H, Burghardtova M, Koubska E, Mandys V, Kozak T, Weichet J. Secondary central nervous system lymphoma: spectrum of morphological MRI appearances. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;4:733–740. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S157959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolecek TA, Propp JM, Stroup NE, Kruchko C. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2005–2009. Neuro-Oncol. 2012;14(suppl 5):v1–v49. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diamond C, Taylor TH, Aboumrad T, Anton-Culver H. Changes in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: incidence, presentation, treatment, and survival. Cancer. 2006;106(1):128–135. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Neill BP, Decker PA, Tieu C, Cerhan JR. The changing incidence of primary central nervous system lymphoma is driven primarily by the changing incidence in young and middle-aged men and differs from time trends in systemic diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkins lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(12):997–1000. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1992;41(rr-17):1–19. [no authors listed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maiuri F. Central nervous system lymphomas and immunodeficiency. Neurological Research. 1989;11(1):2–5. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1989.11739851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haldorsen IS, Espeland A, Larsson EM. Central nervous system lymphoma: characteristic findings on traditional and advanced imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;32(6):984–992. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gómez Roselló E, Quiles Granado AM, Laguillo Sala G, Gutiérrez S. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: spectrum of findings and differential characteristics. Radiología. 2018;60(4):280–289. doi: 10.1016/j.rx.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mabray MC, Cohen BA, Villanueva-Meyer JE, et al. Performance of Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Values and Conventional MRI Features in Differentiating Tumefactive Demyelinating Lesions From Primary Brain Neoplasms. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2015;205(5):1075–1085. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]