Abstract

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an important public health problem worldwide. However, there are few active disease surveillance systems for it. The China Kidney Disease Network (CK-NET) was established as a comprehensive surveillance system for CKD using various data sources. As part of this, the proposed CK-NET-Yinzhou study aims to build a regional surveillance system in a developed coastal area in China to obtain detailed dynamic information about kidney disease and to improve the ability to manage the disease effectively.

Methods and analysis

Yinzhou is a district of Ningbo city, Zhejiang province. The district has a population of more than 1 million. By 2016, 98% were registered in a regional health information system that started in 2009. This system includes administrative databases containing general demographic characteristics, health check information, inpatient and outpatient electronic medical records, health insurance information, disease surveillance and management information, and death certificates. We will use longitudinal individual electronic health record data to identify people with CKD by repeated laboratory measurements and diagnostic codes. We will also evaluate the associated risk factors, prognosis and disease management. An intelligent clinical decision support system (CDSS) will be developed based on clinical guidelines, domain expert knowledge and real-world data, and will be integrated into the hospital information system.

Ethics and dissemination

The CK-NET-Yinzhou study has been reviewed and approved by the Peking University First Hospital Ethics Committee. Privacy of local residents registered with the health information system will be tightly protected through the study process. The findings of the study will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journal articles, posters and presentations in national and international scientific conferences, as well as among local practitioners through the CDSS.

Keywords: electronic health record, chronic kidney disease, surveillance system, clinical decision support system

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study is among the first to establish a chronic kidney disease (CKD) surveillance system in China based on data from linked individual-level electronic health records covering more than one million people in the population.

It will identify CKD using both diagnostic codes and abnormalities in laboratory tests. The prognosis and complications associated with CKD will be traced and monitored using information about repeated health checks, primary care visits, hospitalisation, disease surveillance and death certificates.

A clinical decision support system will be developed and integrated into the healthcare system to improve the quality of care for CKD.

There are likely to be inconsistencies in diagnosis from different data sources, inaccuracy in some data domains and missing data, and data quality will have to be managed carefully.

The study will cover a large population but will be limited to a developed coastal area of China, and the population there may not be representative of the whole country.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global public health problem, with an estimated prevalence of 10%–16% across major developed and developing countries.1 2 However, awareness of CKD is extremely low (less than 20% among the general population in most countries).3 4 CKD can lead to increased morbidity and mortality. The 2010 Global Burden of Disease study found that the proportion of deaths linked to CKD has risen by 82.3% in the last two decades, just behind HIV/AIDS and diabetes mellitus.5 The 2016 Global Burden of Disease study showed that the burden of CKD kept increasing from 2002 to 2016 and outpaced other non-communicable diseases in the USA.6 In China, an analysis using a nationwide hospitalisation registry showed that the proportion of CKD related to diabetes has been greater than the proportion related to glomerulonephritis since 2010, and that metabolic diseases now play a more important role in driving the CKD epidemic.7

Disease surveillance systems have been defined as ‘ongoing, systematic, collection, analysis and interpretation of health data essential to the planning, implementation and evaluation of public health practice, closely integrated with the timely dissemination of these data to those who need to know’.8 Establishing such a system is an essential step in making effective public policy and allocating resources for controlling diseases. Considerable work has gone into creating registries for patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), especially those under renal replacement therapy, but there are only limited examples for predialysis CKD.9 In 2014, the China Kidney Disease Network (CK-NET), which was originally proposed by the late Hai-Yan Wang, tried to establish a robust CKD surveillance system by leveraging data from the national Hospital Quality Monitoring System.10 However, this system only covers inpatient records, not laboratory test results or outpatient clinic records. This limited its ability to capture patients with CKD, as well as provide data for risk factor analysis.11

In Yinzhou district, in the city of Ningbo, Zhejiang province, electronic health record data are distinguished by linking almost all aspects of healthcare, including public health, health insurance, disease registries and clinical practice. The data are updated on a daily basis.12 Using this platform and an efficient primary healthcare network, it was considered possible to expand on the CK-NET work to design a new study, CK-NET-Yinzhou, with the aims:

To monitor incidence and prevalence of CKD using data from electronic health records on repeatedly measured laboratory indicators of CKD and diagnostic International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes.

To monitor prognosis and complications of CKD, evaluate the management of the disease and related conditions (mainly hypertension and diabetes), and assess referrals to nephrologists in secondary and tertiary hospitals.

To develop a clinical decision support system (CDSS) for CKD management, and to improve the efficiency and quality of healthcare by incorporating this into the local healthcare system.

Methods and analysis

Setting and data sources

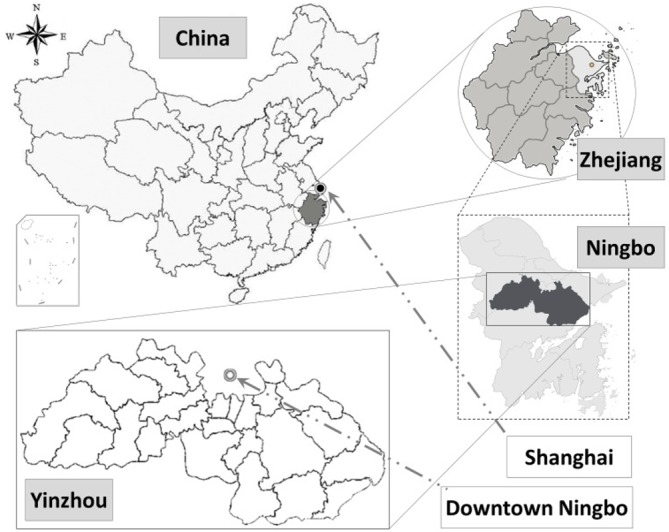

We aimed to establish a CKD surveillance and management system in Yinzhou, a district of Ningbo in Zhejiang province in China, which has a population of 1.24 million (figure 1). Yinzhou is noted for its excellent primary healthcare system and a comprehensive health information system, which has linked all public health and clinical databases in the region since 2009. A detailed description of the health information system in Yinzhou has been published elsewhere.12 This system integrates administrative databases on general demographic characteristics, health checks information, inpatient and outpatient electronic medical records, health insurance, disease management, death certificates and environmental monitoring data, and is updated in real time. In total, 98% of the population in Yinzhou had registered in the system by 2016. The data sources are linked by unique and encoded identifiers. The data sources, topics covered in this study and potential limitations are listed in table 1 and online supplementary figure S1). A third-party company, Wonder Information Corporation, is in charge of maintaining the system, linking the databases and keeping personal information stored securely.

Figure 1.

Study location for the CK-NET-Yinzhou study. Reproduced from Lin et al, 2018,12 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. CK-NET, China Kidney Disease Network.

Table 1.

Data sources and topics in establishing a CKD surveillance system in China

| Data source | Indications of CKD | Risk factors for CKD | Progression of CKD and outcomes | Medical interventions | Limitations |

| Population census and registered health insurance database | NA | Demographics, lifestyle risk factors | NA | NA | Only one record of measurement for each person. |

| Health checks database* | Serum creatinine, dipstick test of proteinuria | Physical examinations, laboratory tests, disease history | Serum creatinine, dipstick test of proteinuria | Types, doses and frequency of prescription | 1–2 years’ lag, no information on medications. |

| Disease surveillance and management database | NA | NA | Diagnosis of CVD, Death certificates | Types, doses and frequency of prescription | No information on laboratory tests. |

| Outpatient/inpatient EMR database | Serum creatinine, urine albumin to creatinine ratio, ICD-10 codes for CKD | Physical examinations, laboratory tests, disease history | Diagnosis of comorbidities, CVD, ESKD and death certificates | Types, doses and frequency of prescription | Coverage limited to patients with outpatient/inpatient visits. |

| Charge and claims database | NA | NA | NA | Types, doses and frequency of prescription | Prescription information may not be accurate. |

*Health checks database refers to health checks for new rural cooperative medical scheme, health checks for elderly people and health checks for adults with hypertension and diabetes.

CKD, chronic kidney disaese; CVD, cardiovascular disease; EMR, electronic medical record; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; NA, not available.

bmjopen-2019-030102supp001.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)

Identification of those with CKD and at risk of CKD

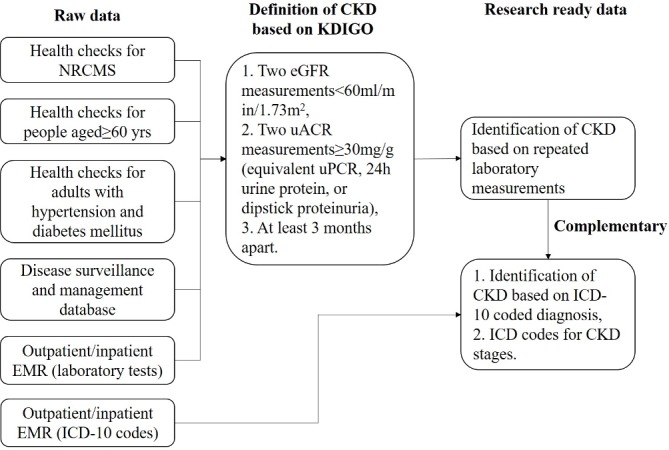

The definition of CKD used in this study will be from the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guideline,13 and the CKD-specific diagnosis in International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes (both cause-specific and in CKD stages, table 2). The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) will be calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Consortium creatinine equation.14 Two eGFR measurements <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 at least 3 months apart, two urine albumin to creatinine ratio of at least 30 mg/g (or equivalent urine protein to creatinine ratio, 24 hours’ urine protein and dipstick proteinuria) at least 3 months apart or diagnosis of CKD by ICD-10 codes from electronic medical record data will be used to define CKD (figure 2). In 2017 and 2018, 30.5% (195 562/640 393) of the adult permanent residents had at least two records of serum creatinine separated by more than 3 months. The corresponding proportion is 39.1% (250 415/640 393) for urine protein (dipstick or quantitative proteinuria/albuminuria measurement). Risk factors used to define those at risk of CKD were smoking, family history of CKD, hypertension, diabetes, long-term exposure to nephrotoxic drugs and previous hospitalisation for acute kidney injury. We will focus in particular on the population identified as having hypertension and/or diabetes. The definition of hypertension and diabetes will be based on levels of measurements (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg for hypertension, fasting blood glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L and/or haemoglobin A1c ≥6.5% for diabetes), diagnosis by physicians or use of particular medications. To clarify the natural course of CKD, especially with autoimmune diseases or hereditary kidney disease, a general population-based control group will be selected.

Table 2.

The ICD-10 codes for CKD

| Aetiology or stage of CKD | ICD coding |

| Diabetes mellitus | |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus with renal complications | E10.2 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus with renal complications | E11.2 |

| Other specified diabetes mellitus with renal complications | E13.2 |

| Unspecified diabetes mellitus with renal complications | E14.2 |

| Hypertensive diseases | |

| Hypertensive renal disease with renal failure | I12.0 |

| Hypertensive renal disease without renal failure | I12.9 |

| Hypertensive heart and renal disease with (congestive) heart failure | I13.0 |

| Hypertensive heart and renal disease with renal failure | I13.1 |

| Hypertensive heart and renal disease with both (congestive) heart failure and renal failure | I13.2 |

| Hypertensive heart and renal disease, unspecified | I13.9 |

| Glomerular diseases | |

| Acute nephritic syndrome, other | N00.8 |

| Recurrent and persistent haematuria | N02 |

| Chronic nephritic syndrome | N03 |

| Nephrotic syndrome | N04 |

| Unspecified nephritic syndrome | N05 |

| Isolated proteinuria with specified morphological lesion | N06 |

| Persistent proteinuria, unspecified | N39.1 |

| Renal tubulointerstitial diseases | |

| Chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis | N11 |

| Tubulointerstitial nephritis, not specified as acute or chronic | N12 |

| Drug-induced and heavy metal-induced tubulointerstitial and tubular conditions | N14 |

| Other renal tubulointerstitial diseases | N15 |

| Renal tubulointerstitial disorders in diseases classified elsewhere | N16 (exclude N16.4) |

| Other specified disorders of carbohydrate metabolism | E74.8 |

| Disorders of amino acid transport | E72.0 |

| Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus | N25.1 |

| Obstructive nephropathy | |

| Hydronephrosis with ureteropelvic junction obstruction | N13.0 |

| Hydronephrosis with ureteral stricture, not elsewhere classified | N13.1 |

| Hydronephrosis with renal and ureteral calculous obstruction | N13.2 |

| Other chronic kidney failure, unknown cause | |

| CKD | N18 not combined with I10 |

| Unspecified kidney failure | N19 not combined with I10 |

| Stage of CKD | |

| CKD stage 1 | N18.801 |

| CKD stage 2 | N18.802 |

| CKD stage 3 | N18.803 |

| CKD stage 4 | N18.804 |

| CKD stage 5 | N18.001 |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; ICD, International Classification of Diseases.

Figure 2.

Data sources and criteria to define CKD. CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; EMR, electronic medical record; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; KDIGO, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes; NRCMS, New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme; uACR, urinary albumin to creatinine ratio.

Monitoring the diagnosis and management of those with CKD and at risk of CKD

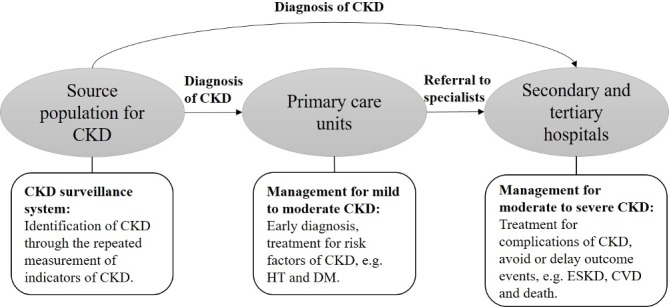

The diagnosis of individuals meeting our criteria for CKD identified by laboratory tests will be monitored in both primary healthcare units and higher level hospitals (identified through codes). This is meant to reflect the ability to identify patients with CKD in the healthcare system. We will also evaluate the achievement of goals consistent with clinical guidelines for intervention for hypertension, diabetes and lipid profiles, among patients with CKD or at risk of CKD. We will especially focus on the use of renin–angiotensin system inhibitor for diabetics with proteinuria and hypertension and evaluate their effects on control of hypertension and albuminuria. We will also monitor the identification and referral of patients in CKD stages G4–G5 (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2) or with severe comorbidities to specialists in nephrology in secondary or tertiary hospitals (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Process for management of patients with CKD. CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; HT, hypertension.

Creating a CDSS to be integrated into the process of diagnosis and management of CKD

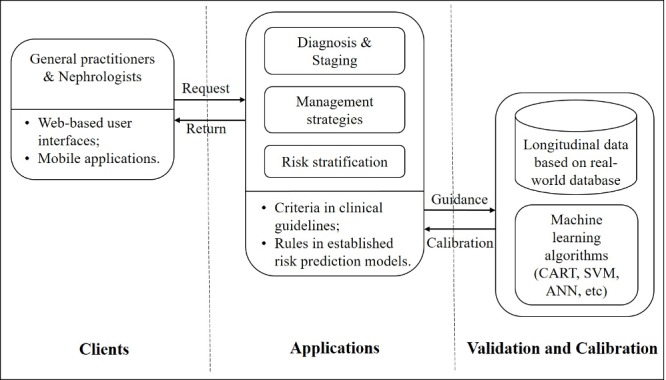

A CDSS will be developed and integrated into the hospital information system in Yinzhou to facilitate diagnosis and management of CKD by general practitioners and specialists in nephrology. In line with the appropriate guidelines,13 diagnosis and staging information about CKD will be provided in the system if certain criteria are met and will appear in appropriate interfaces embedded in the web-based working station for general practitioners. Suggestions for additional examinations and follow-up frequencies will be provided if necessary. A risk stratification tool for categorising CKD patients based on the probability for prognosis of CKD and occurrence of complications will also be developed. The established prediction model for adverse outcomes developed in Western countries will be validated using real-world data from Yinzhou before being incorporated into the decision support system (figure 4).15 16

Figure 4.

Development of clinical decision support system for diagnosis and risk stratification of CKD. ANN, artificial neural network; CART, classification and regression tree; SVM, supportive vector machine.

Outcomes

The CKD surveillance system will monitor kidney function progression and occurrence of ESKD, cardiovascular disease and death as outcomes. Both events and their date of occurrence will be recorded. Kidney function progression will be monitored using the longitudinal serum creatinine measurements (or other alternative markers for kidney function), and the slope, trajectory and magnitude of decline (50% or 30% decline) in kidney function will be calculated. The slope of kidney function change can be used as a surrogate outcome for prognosis for CKD. To monitor occurrence of ESKD, we will focus on renal replacement therapy, which includes haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis and kidney transplantation. Proposed cardiovascular disease events include non-fatal heart failure, non-fatal coronary heart disease, non-fatal ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke, heart arrhythmia and peripheral artery disease. The detailed ICD-10 codes for cardiovascular events are shown in table 3. The records will be obtained from both the electronic medical records database and the cardiovascular disease registry. Information about the primary cause of death will be extracted from death certificates. The database of health insurance claims will also provide outcome information.

Table 3.

The ICD-10 codes for cardiovascular disease

| Types of CVD | ICD coding |

| Acute coronary syndrome | |

| STEMI | I21.0, I21.1, I21.2, I21.3, I21.9 |

| NSTEMI | I21.4, I20.0, I20.1, I20.9 |

| Others | I22, I24 |

| Other coronary heart diseases | |

| Chronic ischaemic heart disease | I25 |

| Exertional angina pectoris | I20.803 |

| Postinfarction angina pectoris | I20.005 |

| Syndrome X | I20.802 |

| Stable angina pectoris | I20.801 |

| Mixed angina pectoris | I20.804 |

| Heart failure | I50 |

| Other heart diseases | |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | I42.0 |

| Other hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | I42.2 |

| Other restrictive cardiomyopathy | I42.5 |

| Cardiomyopathy, unspecified | I42.9 |

| Cardiovascular disease, unspecified | I51.6 |

| Heart disease, unspecified | I51.9 |

| Pulmonary oedema | J81 |

| Cerebral stroke | |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage | I60 |

| Intracerebral haemorrhage | I61 |

| Acute ischaemic cerebral stroke | I63, I64, H34.1 |

| Peripheral artery disease | I70.2, I73.9, I74.3, I74.4 |

CVD, cardiovascular disease; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; NSTEMI, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Data analysis

Prevalence of CKD will be calculated using the number of cases as numerator and the total population covered by the surveillance system as denominator. The cumulative incidence of CKD per year will be calculated by counting new diagnoses. The Cox proportional hazards regression model will be used to estimate the association between the proposed risk factors and medical interventions and time to outcomes. We will use longitudinal data for the measurement of risk factors so that time-dependent variables can be used in the model, and interactions with time and between covariates will be carefully checked to avoid bias. Linear mixed-effect modelling will be used to estimate the slope of change in kidney function and to evaluate the effect of risk factors and medical interventions. We will identify patterns in the trajectory of change in kidney function using the latent growth model.17 Traditional and new machine learning and deep learning algorithms, for example, the classification and regression tree model, support vector machine and artificial neural networks, will be used to develop risk prediction models where appropriate. These algorithms are particularly useful for dealing with a large number of candidate risk factors.18 The random survival forest model will be used to rank the comparative importance of the risk factors, and the classification and regression tree model will be used to find appropriate cutoffs for indicators and risk factors for CKD.

Patient and public involvement

The research questions and outcome measures for this study are based on recognised and agreed clinical guidelines, and the majority of work on data linkage and analysis is technical. We have, therefore, not involved patients and the public in the design of the study. However, we hope that the study findings will raise awareness of CKD among the general population, and improve treatment adherence among patients with CKD, hypertension and diabetes. We will therefore invite residents and patients in Yinzhou to participate in developing a community-based healthcare plan for CKD and involve them in the dissemination of the study outcomes.

Discussion

This protocol describes how we plan to establish a CKD surveillance system based on a regional health information system in Yinzhou, Ningbo, Zhejiang, China. We aim to establish the disease burden of CKD and evaluate the risk factors, medical interventions and prognosis of the disease. We also hope to develop a CDSS to facilitate management of CKD in both primary healthcare and nephrology settings. The ultimate goal of this surveillance system was to lower disease burden of CKD and to improve the care provided for this disease.

A number of countries have established surveillance systems for ESKD, but few assess predialysis CKD.9 In the USA, the national CKD surveillance system uses a number of data sources, including administrative databases, national surveys and ongoing prospective cohort studies.19 The topics addressed in the system and the corresponding measures and indicators were agreed by expertise in nephrology, epidemiology and other disciplines. Each topic will be addressed by selecting appropriate data sources from the system. Besides leveraging comprehensive data sources, the common practices in establishing a chronic disease surveillance system include linking data covering different aspects of the healthcare system and making secondary use of them. Typically, the system might bring together laboratory results, diagnostic codes and/or prescription information for individuals. For example, one CKD registry in the USA is based on the Cleveland Clinic Healthcare Network.20 A nationwide CKD surveillance system in Canada is based on the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network,21 and a CKD screening programme in Singapore uses the national primary care system.22 In our project, the linked data sources in the health information system in Yinzhou include electronic health records from different levels of hospitals, the public health information system and the health insurance system.12 The primary healthcare network in Yinzhou has sufficient facilities and workforce to reach every area, and can provide basic diagnosis and treatment for hypertension and diabetes. Local tertiary hospitals provide advanced management for CKD, including haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis and kidney transplantation. Information about environmental exposures, including meteorological elements, urban sewage and air pollutants, which may have an adverse influence on health, are available through links with routinely monitoring activity. Yinzhou, therefore, is an ideal place to establish such a monitoring system for CKD.

The majority of CKD detected in the general population in China is in the early stages, characterised by the presence of albuminuria and normal or mildly reduced kidney function.2 With the increasing prevalence of metabolic diseases over the past decades, data from the registry for renal replacement therapy in Beijing and Shanghai of China show that ESKD requiring renal replacement therapy has increased.23 24 However, much is still unknown about the current burden of CKD and ESKD in China, as well as the healthcare practice required to manage the challenges of the disease. To fill this gap, we initiated the CK-NET study to establish a CKD surveillance system in China. In the first annual data report of CK-NET, we used hospitalisation records from tertiary hospitals around the country to show the burden, causes, interventions and costs of CKD.10 In the recent second annual data report of CK-NET, we focused on the disease burden of ESKD, using more data sources, including commercial health insurance and health insurance for permanent residents.25 However, these administrative data sources lack laboratory measurements and may lead to considerable underdetection of CKD. The source population and the prognosis for the patients are also typically unclear. Therefore, this limits the ability to use these data to evaluate risk factors, medical interventions and associated outcomes. However, this information can be obtained from more comprehensive data within the integrated health information system.

The Global Kidney Health Atlas, initiated by the International Society of Nephrology, reported that there is a shortage of trained staff and insufficient capacity in nephrology in middle-income countries, including China.26 Besides monitoring the ongoing disease burden, risk factors and prognosis for CKD, another aim of this project was to promote guideline-based practices for the management of those with or at risk of CKD. The effectiveness of this will be evaluated in the health system in Yinzhou, and new knowledge will be generated and circulated to general practitioners, nephrologists and other health professionals during the process of routine healthcare practice. This is essential to create a learning health system where healthcare providers can access and apply evidence in real time and rigorous scientific research can be conducted using the advanced health information technology and infrastructure.27 We hope that a learning health system can be built in Yinzhou to improve the quality of care. It is possible that increased awareness of CKD may result in unnecessary investigation and even overdiagnosis, but we believe that better management of those with and at risk of CKD, especially through improved primary healthcare service, will reduce the burden of CKD and increase the efficiency of the whole healthcare system. Additionally, many healthcare services can be examined and promoted by conducting pragmatic clinical trials. Randomised clinical trials with strict inclusion and exclusion criteria can be much more easily conducted by accessing various longitudinal information of patients.28

Despite the above-mentioned advantages, our study has some limitations, which may also be issues in other electronic health record-based studies. First, there may be inconsistencies in the identification of disease status. Both diagnosis and date of onset of a specific disease could vary between data sources. It will therefore be necessary to decide on priorities for data sources and protocols to combine information. We tend to first rely on information from disease registries and then on the diagnosis in the discharge form provided by secondary/tertiary hospitals. We will also include a category for uncertain cases where information is insufficient for diagnosis. Second, there are likely to be missing data, which may be a more significant issue with some data sources. To manage this, we will use several imputation methods or delete cases with missing values in key variables before data analysis. We will also evaluate the potential for selective bias as a result. Third, information about frequency and doses in prescription may not be accurate. Fourth, Yinzhou is a developed area in the southeast of China. Compared with a representative sample of the general adult population of China recruited for the China Health and Nutrition Survey examined in 2009, the population in Yinzhou is younger (mean age: 39.7±15.4 years vs 44.5±16.9 years), with a higher proportion of men (48.6% vs 46.7%), fewer current smokers (19.6% vs 28.0%) and similar body mass index (22.5±2.5 kg/m2 vs 23.3±3.5 kg/m2), and systolic (127.1±14.9 mm Hg vs 124.6±18.8 mm Hg) and diastolic (79.0±9.9 mm Hg vs 80.5±11.3 mm Hg) blood pressure levels.12 29 The population of Yinzhou is therefore not representative of the whole country, and the strategies and procedures for CKD management developed in this study will need to be assessed further before they are applied elsewhere.

Ethics and dissemination

In developing this study protocol, we have carefully considered security, privacy and confidentiality issues related to storage and handling of individual electronic health record data. The database is stored in the central repository operated by the local telecom administrative bureau and supervised by the local public security organisation. The establishment of the CKD surveillance system using electronic health record-based health information system has been approved by the local health authority (Health and Family Planning Bureau of Yinzhou District). A third-party company (Wonders Information Corporation) was responsible for linking different data sources and used encrypted identifiers. To protect the confidentiality of participants, all personal identifiers will be removed before data use by the researchers. Electronic health record data are collected in routine practice, so the participants do not provide informed consents. The study has been approved by the ethics committee of Peking University First Hospital. The study results will be disseminated in published journal articles and at conferences, through seminar posters and presentations. They will also be included in the Annual Data Report of CK-NET. The CDSS will facilitate access to clinical evidence among healthcare providers in the region.

In conclusion, this protocol describes work to establish a CKD surveillance system in Yinzhou, Ningbo, to monitor the ongoing disease burden of CKD in the area. The work will help to improve the competency of local general practitioners and specialists through the use of a CDSS. We hope it will optimise the management of CKD and improve the outcome for patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Alicic Radica of Providence Health Care for her suggestions on extraction of key variables from electronic health records in establishing a chronic kidney disease surveillance system, and Melissa Leffler of Liwen Bianji, Edanz Editing China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of the draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

JW and BB contributed equally.

Contributors: JW, BB, PS and LZ drafted the manuscript. JW, BB, PS, MZ, HL and LZ conceived and designed the study. HL, BB and PS are responsible for study coordination; JW, PS, XS, GK, and YY are responsible for data quality control; PS, XS and GD are responsible for data wrangling; and JW, BG, CY and LZ are responsible for data analysis. All authors contributed to the writing of the study protocol in an iterative manner, and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91846101 and 81771938), the National Key R&D Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (2016YFC1305400), the University of Michigan Health System–Peking University Health Science Center Joint Institute for Translational and Clinical Research (BMU2018JI012) and the Peking University Medicine Fund of Fostering Young Scholars’ Scientific and Technological Innovation (BMU2018PYB005).

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on the map(s) in this article do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, et al. . Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 2013;382:260–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang L, Wang F, Wang L, et al. . Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2012;379:815–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jha V, Wang AY, Wang H. The impact of CKD identification in large countries: the burden of illness. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association 2012;27(Suppl 3):iii32–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang F, Zhang L, Wang H. Awareness of CKD in China: a national cross-sectional survey. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation 2014;63:1068–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. . Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2095–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bowe B, Xie Y, Li T, et al. . Changes in the US burden of chronic kidney disease from 2002 to 2016: an analysis of the global burden of disease study. JAMA Network Open 2018;1:e184412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang L, Long J, Jiang W, et al. . Trends in chronic kidney disease in China. N Engl J Med 2016;375:905–6. 10.1056/NEJMc1602469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thacker SB, Stroup DF. Future directions for comprehensive public health surveillance and health information systems in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 1994;140:383–97. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Radhakrishnan J, Remuzzi G, Saran R, et al. . Taming the chronic kidney disease epidemic: a global view of surveillance efforts. Kidney Int 2014;86:246–50. 10.1038/ki.2014.190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang L, Wang H, Long J, et al. . China kidney disease network (CK-NET) 2014 annual data report. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation 2017;69(6S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saran R, Steffick D, Bragg-Gresham J. The China Kidney Disease Network (CK-NET): "Big Data-Big Dreams". Am J Kidney Dis 2017;69:713–6. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin H, Tang X, Shen P, et al. . Using big data to improve cardiovascular care and outcomes in China: a protocol for the Chinese electronic health records research in Yinzhou (cherry) study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019698 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chapter 1: definition and classification of CKD. Kidney Int Suppl 2013;3:19–62. 10.1038/kisup.2012.64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. . A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tangri N, Grams ME, Levey AS, et al. . Multinational assessment of accuracy of equations for predicting risk of kidney failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2016;315:164–74. 10.1001/jama.2015.18202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grams ME, Sang Y, Ballew SH, et al. . Predicting timing of clinical outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease and severely decreased glomerular filtration rate. Kidney Int 2018;93:1442–51. 10.1016/j.kint.2018.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jiang G, AOY L, CHT T, et al. . Progression of diabetic kidney disease and trajectory of kidney function decline in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Naylor CD. On the prospects for a (deep) learning health care system. JAMA 2018;320:1099–100. 10.1001/jama.2018.11103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saran R, Hedgeman E, Plantinga L, et al. . Establishing a national chronic kidney disease surveillance system for the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5:152–61. 10.2215/CJN.05480809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Navaneethan SD, Jolly SE, Schold JD, et al. . Development and validation of an electronic health record-based chronic kidney disease registry. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;6:40–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bello AK, Ronksley PE, Tangri N, et al. . A national surveillance project on chronic kidney disease management in Canadian primary care: a study protocol. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ramirez SPB, McClellan W, Port FK, et al. . Risk factors for proteinuria in a large, multiracial, Southeast Asian population. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002;13:1907–17. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000018406.20282.C8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gan L, Zuo L. Current ESRD burden and its future trend in Beijing, China. Clin Nephrol 2015;83(7 Suppl 1):17–20. 10.5414/CNP83S017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen Z, Zhang W, Chen X, et al. . Trends in end-stage kidney disease in Shanghai, China. Kidney Int 2019;95:232 10.1016/j.kint.2018.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang F, Yang C, Long J, et al. . Executive summary for the 2015 Annual Data Report of the China Kidney Disease Network (CK-NET). Kidney Int 2019;95:501–5. 10.1016/j.kint.2018.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bello AK, Levin A, Tonelli M, et al. . Assessment of global kidney health care status. JAMA 2017;317:1864–81. 10.1001/jama.2017.4046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Greene SM, Reid RJ, Larson EB. Implementing the learning health system: from concept to action. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:207–10. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-3-201208070-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Strippoli GFM, Craig JC, Schena FP. The number, quality, and coverage of randomized controlled trials in nephrology. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004;15:411–9. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000100125.21491.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li M, Shi Z, during DP. And its association with cardio metabolic risks in Chinese adults: the China health and nutrition survey. Nutrients 1991-2011;2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030102supp001.pdf (1.3MB, pdf)