Abstract

This longitudinal study examines how the time that youth spend in activities during high school may contribute to positive or negative development in adolescence and in early adulthood. We draw on data from 1103 participants in the longitudinal Youth Development Study, followed from entry to high school to their mid-twenties. Controlling demographic, socioeconomic, and psychological influences, we estimate the effects of average time spent on homework, in extracurricular activities, and with friends during the four years of high school on outcomes measured in the final year of high school and twelve years later. Our results suggest that policies surrounding the implementation and practice of homework may have long-term benefits for struggling students. In contrast, time spent with peers on weeknights was associated with both short- and long-term maladjustment.

Keywords: Positive youth development, time use, homework, extracurricular activities, peers

Introduction

Time use in adolescence is a contentious topic that has generated extensive research and policy discussion. Parents, teachers, and the wider public have strong opinions about how students should spend their time during high school (Farb & Matjasko, 2012; Zuzanek, 2009). Out-of-school activities are thought to shape life outcomes beyond the senior year (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007), and research supports this claim (Broh, 2002; Fredricks & Eccles, 2006; Gibbs, Erickson, Dufur, & Miles, 2015; McHale, Crouter, & Tucker, 2001; Peck et al., 2008; Viau, Denault, & Poulin, 2015). Homework and extracurricular activities (e.g. theater, music, sports, church youth groups) are found to have positive effects on educational achievement, prosocial behavior, problem behavior, and delinquency (Cooper, Robinson, & Patall, 2006; Farb & Matjasko, 2012; Fredricks & Eccles, 2006; Zaff, Moore, Papillo, & Williams, 2003; Vandell, Larson, Mahoney, & Watts, 2015).1 In contrast, unsupervised time with peers may be detrimental to positive development in and out of school at various ages (Barnes, Hoffman, Welte, Farrell, & Dintcheff, 2007; Mahoney, Larson, Eccles, & Lord, 2005; Osgood & Anderson, 2004; Vandell et al., 2015), though evidence indicates that positive relationships with peers can be beneficial for youth emotionally, socially, and academically (e.g. MacLeod 1987; Oberle, Shonert-Reichl, & Thompson, 2010; Vitaro et al. 2009; Wentzel, 2009).

We aim to extend existing studies of adolescents’ use of time and positive youth development (Peck et al., 2008) in several ways: First, most studies in this area are cross-sectional or rely on just a few years of observation (Bartko & Eccles, 2003; Busseri et al., 2006; Camacho & Fuligni, 2015; Darling, 2005; Fredricks & Eccles, 2006; Fredricks & Simpkins, 2012; Simpkins, Eccles, & Becnel, 2008; Wolf et al., 2015). Relatively little is known about the long-term implications of the ways time is spent during high school. The transition to adulthood is often conceived as a “fresh start,” a time of exploration, with opportunity to develop new commitments, enter new social contexts, and form new relationships (Arnett, 2007; Settersten & Ray, 2010). At this time of life, some youth turn their lives around despite difficulties in adolescence (Masten, 2015). In contrast, other youth may falter when they encounter new responsibilities as they take on adult roles. We use longitudinal data to follow students prospectively over 12 years, from mid-adolescence (age 14/15) to early adulthood (age 26/27). The temporal ordering of time spent in high school and outcomes later in life, as well as the use of a wide range of earlier socio-demographic, socio-economic, and psychological controls, help to establish directionality (Sacker & Schoon, 2007).

Second, previous research mainly examines single outcomes of youth development, such as educational achievement or delinquency. As we will elaborate in the following sections, we propose a multi-dimensional definition of positive youth development. Positive youth development refers to the dynamic integration of personality strengths; constructive engagement with families, peer groups, schools, organizations, and communities; adaptation to environmental contexts; and other positive outcomes that indicate “thriving” across adolescence and into young adulthood (Larson, 2000; Lerner et al., 2009; Sesma et al., 2013). This framework obviously encompasses multiple kinds of characteristics and experiences, and cannot be captured by single outcomes alone. Thus, it must be measured in broader, holistic terms to capture the complex array of potential time-use effects and to accommodate the multi-faceted nature of positive development. Accordingly, we constructed multivariate measures of development in adolescence and early adulthood using a Latent Class Analysis based on educational, occupational, behavioral, and psychological outcomes.

Third, most previous studies of time use focus on average effects for a student cohort. Yet, different student populations face distinct challenges from the outset. We expect that time use may have different implications for students with more favorable starting positions compared to students who are situated less favorably. We explore whether time allocation during high school is associated with positive development for teenagers who face initial difficulties (Luthar, Crossman, & Small, 2015; Yates, Tyrell, & Masten, 2015), and whether outcomes are different for students who started out in more sanguine positions.

Fourth, many previous studies examine one type of time use, for example, extracurricular activities, in isolation from other types (e.g. homework, time with peers). Time spent on one activity may be conditional on time spent on other activities and the effects of each may be highly interdependent. We take into account three measures of time use (extracurricular activities, homework, evenings with peers) to disentangle net effects. As such, we respond to the call to examine extracurricular activities in tandem with other ways that adolescents spend their time (Farb & Matjasko, 2012).

We find positive medium- to long-term effects of time spent on homework and extracurricular activities on positive youth development and negative effects of time spent with peers in the evenings. Time spent in organized activities may enhance adolescents’ positive development by providing structure and by reducing the amount of time available to spend in unsupervised contexts. Policies that encourage the practice of homework and extracurricular activities, particularly for youth whose developmental attributes are less favorable at the start of high school, may have the potential to promote positive development far beyond high school in ways that may not have been primarily intended by such homework or extracurricular programs.

Positive Youth Development and Time Use

The Positive Youth Development (PYD) literature (see, for example, Lerner et al., 2009; Sesma, Mannes, & Scales, 2013) provides a framework for assessing the complex trajectories of youth throughout and beyond high school. PYD is often described as the development of mutually adaptive and beneficial relations between youth and the contexts in which they grow up (i.e. Lerner, 2017). There is no common agreement, however, about how positive development should be measured. Studies vary substantially in terms of the outcomes used to indicate positive development, including educational performance, problem behavior, employment, aspirations, etc. (see, e.g. Leman, Smith, Peterson & SRCD Ethnic-Racial Issues and International Committees, 2017). Common to most studies relying on the PYD framework is the notion that positive development is a complex, multifaceted process that may affect multiple life domains (Lerner et al., 2009).

PYD frames development as resulting from the reciprocal relationship between individual choices and youth contexts. The study of adolescents’ use of time is integral to understanding this dynamic (e.g., Wolf et al., 2015). Policies that provide opportunities for growth and protect against risk are critical from the PYD perspective (Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2003). While researchers and practitioners previously embraced a deficit-oriented perspective, recent literature stresses the importance of developing assets to promote strength (promotive factors) and resources for those exposed to risk (Sesma et al., 2013; Luthar et al., 2015). The ways students spend their time during high school reflect the contexts of development that youth are regularly exposed to and that are either more or less conducive to positive outcomes.

However, relatively little attention outside the field of criminology (e.g. Barnes et al., 2007) has been directed to factors that protect adolescents with favorable starting points from negative development over time. Because those youth are seen as advantaged, scholars have been less interested in the personal strengths and circumstances that enable young people in favorable starting positions to maintain their positive development over time, and those factors that lead some of them to falter. We are therefore interested in both differential and long-term correlates of time use. From a policy standpoint, so-called ‘overscheduling’ youth in activities may be a problem for more affluent high school districts, involved parents, and active teachers. It may be less of a problem for at-risk youth who face difficulties at home or impoverished schools, with few resources for extracurricular activities, and poor neighborhoods (Putnam, 2015).

Although numerous factors have been shown to contribute to positive youth development, few have examined time spent in activities during the high school period as a predictor of positive or negative development in adulthood. In light of the proposition that children’s activities constitute developmental opportunities (Larson, 1994; Larson & Verma, 1999), in the following sections we describe how three ways youth allocate time may enhance or reduce their exposure to promotive and protective processes.

Homework, Extracurricular Activities, and Time Spent with Peers

Despite some controversy about the drawbacks of too much homework (e.g. Zuzanek, 2009) and the challenges of homework for students with learning disabilities or economically disadvantaged students (Bennet & Kalish, 2006), studies of homework time and effort have consistently demonstrated positive associations with academic achievement (Cooper et al., 2006; Farb & Matjasko, 2012). Beyond promoting educational achievement, a positive factor in itself, homework may have beneficial spill-over. Doing homework, and seeing its results, may enhance motivational resources, including self-regulation, discipline, time-management, self-determination, goal-setting, and achievement motivation (Bempechat, 2004; Ramdass & Zimmerman, 2011). Adolescents who invest more time in doing their homework consistently and thoroughly across their high school years may learn to appreciate its long-term benefits (e.g., better grades, admission to selective colleges).

Studies of extracurricular activities consistently show that mere participation is associated with positive outcomes (Farb & Matjasko, 2012; Lauer et al., 2006; Vandell et al., 2015), including prosocial behavior, educational achievement, and college completion, as well as lower risk of dropout, substance abuse, and criminal behavior (Broh, 2002; Durlak, Weissberg, & Pachan, 2010; Farb & Matjasko, 2012; Gibbs et al., 2015; Shulruf, 2010; Vandell et al., 2015). Extracurricular activities can broadly be defined as activities officially or semiofficially approved and usually organized student activities connected with school and usually carrying no academic credit (e.g., theater, music, sports, church youth groups). The positive effects of such activities increase with program quality, duration, intensity, and consistency (Hirsch et al., 2011; Vandell et al., 2015). A few studies indicate benefits over the transition to young adulthood. Fredericks and Eccles (2006) found that participating in sports and clubs in high school was associated with educational status and civic engagement a year after high school. In a study of female high school athletes, participation in sports was associated with greater odds of college graduation (Troutman & Dufur, 2007). The current study extends this body of research by examining the long-term associations of extracurricular activities and adjustment in young adulthood at age 26/27.

While extracurricular activities are diverse in character and heterogeneous in their effects (Eccles, Barber, Stone, & Hunt, 2003), they are typically designed with the intention to enhance adolescent development. As such, they have a number of attributes in common. First, extracurricular activities (e.g., theater, music, sports, church youth groups) provide opportunities for the development of positive social ties, and they promote cooperative prosocial behavior, social skills, and a sense of community (e.g., Gibbs et al., 2015; Mahoney, 2000). Second, supervised programs expose adolescents to potential adult role models and facilitate relationships with teachers, coaches, and community workers (Viau et al., 2015). Third, many extracurricular activities involve goal setting, long-term commitment, and self-determination (e.g., competitive sports, rehearsing for a play or concert). They offer opportunities to explore interests, acquire skills, develop talents, and experience success (e.g. Hansen, Larson, & Dworkin, 2003; Mahoney et al., 2005). Fourth, when youth are participating in extracurricular activities they are not in ‘harmful’ environments, such as stressful circumstances at home. Thus, structured activities, like homework and participation in the extra curriculum, may enhance the development of protective factors that prevent problem behaviors in adolescence (Barnes et al., 2007; Wolf et al., 2015).

In contrast, research on unsupervised settings has revealed a very different developmental course. Large amounts of unsupervised time with peers may foster problem behaviors like substance use and delinquency (Barnes et al., 2007; Dishion et al., 2015), interfere with school bonding, and reduce achievement (Maimon & Browning, 2010; Mahoney et al., 2005; Osgood & Anderson, 2004). Time spent in the company of other adolescents may also reduce time spent with parents, parental monitoring and control, and routine social interaction in the family that reinforces social norms. However, in some circumstances a lack of time with friends may be harmful to development (e.g., Twenge, Martin, Campbell, 2018), perhaps because students who are socially isolated do not build the interpersonal skills needed for adult roles. Additionally, time with friends – in some cases – is believed to be a strategy to avoid problem situations at home, which could lead to even more adverse consequences (e.g. MacLeod 1987). Thus, peer influence can be positive or negative, depending largely on the pro- or anti-social orientations of friends and the context (Vitaro et al., 2009). In the current study, we specifically focus on unsupervised settings of peer influence by examining evening time with friends.

Hypotheses

The review of key research on adolescents’ use of time in the previous section informs a clear set of expectations:

-

1)

Time investments in homework and extracurricular activities will enable students with less favorable starting positions to achieve positive developmental outcomes as well as help students with favorable starting positions to avoid losing their relative advantage.

-

2)

Unstructured time spent with peers in the evenings during high school will reduce chances for positive development and increase the likelihood that adolescents with favorable starting positions will show lower levels of later positive development.

-

3)

Adolescents’ use of time during high school will matter not only over the course of high school (from middle to late adolescence) but also in early adulthood.

Methods

Data.

In 1987, Youth Development Study participants (N = 1,139) were recruited as ninth graders (mostly age 14–15) entering all high schools in the St. Paul, Minnesota Public School District via random sampling (Mortimer, 2012). U.S. Census data show that this site was comparable to the nation as a whole with respect to several economic and sociodemographic indicators (Mortimer, 2003). In 1989, per capital incomes in St. Paul and in the nation at large were $13,727 and $14,420 respectively. However, St. Paul residents were more highly educated than in the U.S. (among persons 25 and older, 33% and 20%, respectively, were college graduates). The minority population in the St. Paul School District was 30 percent in the mid-1980s, and 25 percent in the YDS panel. Because the YDS panel represented the ethnic/racial composition of the St. Paul community, the largest minority group consisted of Hmong children (11% of the initial panel) who were recent refugees. Comparison of census tract data for those who consented and those who refused the invitation to participate in the study did not reveal significant differences in socioeconomic variables.

Children were surveyed annually, during the first four years in their school classrooms, and subsequently by mail. The current study utilizes waves 1 (1988), 2 (1989), 3 (1990), 4 (1991), and 12 (2000). In 2000, 12 years after the first wave, 70% of the original sample (age 26–27) remained. Because of attrition, analyses of time use and developmental change during adolescence are based on a larger sample than those covering the period of transition to adulthood. Although a wide range of attitudes and behaviors (measured in 1988) do not predict retention in the study, attrition has been greater among men, minorities, and youth without an employed parent (Mortimer, 2012).

Measures

Dependent variable.

To capture the complex array of potential time-use effects and to accommodate the multi-faceted nature of positive development, we constructed holistic, multivariate measures of development in adolescence and early adulthood using a person-centered approach. Person-centered analyses, like Latent Class Analysis (LCA), enable a global focus on the whole person, which is more naturalistic than the traditional regression approach of statistically “controlling” various aspects of life (Masten, 2015). Based on a range of indicators of positive development over time, the LCA statistically identified ‘more favorable’ and ‘less favorable’ positions at three stages of development:

wave 1—middle adolescence, or the freshman year of high school, when most respondents were 14 and 15 years old;

wave 4—late adolescence, or the senior year of high school, ages 17–18;

and wave 12—early adulthood, ages 26/27.

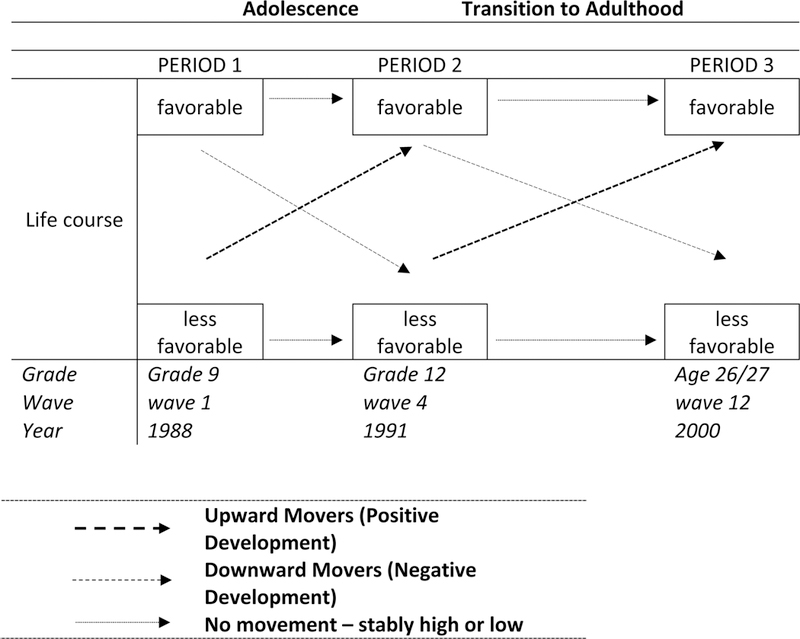

Subsequently, we look at movements between categories across adolescence and the transition to adulthood. We examined “upward” movement from less favorable to more favorable positions over time (i.e. positive development). Conversely, “downward” movement refers to moving from favorable positions at the start to overall less favorable positions indicated by a range of outcomes. Figure 1 provides a graphic representation of our conceptual framework, showing positive and negative development over time.

Figure 1:

Movement between latent classes across developmental stages

Using the period between Grades 9 and 12 as an example, if a respondent is identified as having a more favorable developmental status in the 9th grade, but is then seen to exhibit less favorable attributes in 12th Grade, he or she is considered to experience negative development (downward movement). If instead, the movement seen is from the less favorable to more favorable categories, they are thought to experience positive development (upward movement). Respondents can also be stable if there is no movement between any two periods.

An advantage of LCA is that it allows groups to emerge from relationships in the data, rather than imposing groupings based on researchers’ preconceived notions, in this case, of what constitutes positive development. In using this method, we assume that choices, attitudes, motivations, and behaviors can be observed and that the interrelations of these phenomena are similar for individuals in a specific group and distinct from other groups. Therefore, identifying how these observable characteristics converge lets us construct a plausible grouping of individuals exhibiting similar multifaceted patterns.

Latent classes were constructed based on variables in educational, behavioral, and psychological domains that are time-variant and indicative of “positive development” in each phase.2 These domains have close and complementary relationships over time (Masten, 2015; Obradovíc et al., 2009.) The choice of indicators was informed by the Policy Research Team in Ramsey County, Minnesota, which oversees and evaluates several programs targeted to improving the prospects of at-risk youth. We established variable cut-offs indicating the points at which students might be considered to be in more or less favorable positions based on past literature and practical guidelines (e.g., a GPA of C+ is below the average of students admitted to college), not to separate the most high-achieving students from others. As a result, cut-offs for some variables may be considered a rather “low bar.” In setting these markers, we also considered the variable distributions to have sufficient numbers of cases in each category. Though this measurement strategy might be considered a limitation (given restricted variance), it honors the empirical linkages among several variables in a holistic manner.

In middle and late adolescence, educationally-related variables included grade point average (C+ or better, less than C+); educational aspiration, or the highest level of schooling the students think they will achieve (4 years of college or more, less than 4 years of college); and intrinsic motivation toward school (high, low). In the behavioral domain, we included getting in trouble at school (low, high), number of alcoholic drinks in the last 30 days (2 or less, more than 2); and smoking cigarettes in the last 30 days (no, yes). Psychological orientations included certainty about achieving career goals (high certainty, not as certain) and an index of more general expectations concerning the future (high, or more optimistic, or low, more pessimistic).

Considering these indicators together produces strong, holistic measures of more or less favorable development in adolescence.3 Table 1 shows the prevalence of each class in our sample in middle and late adolescence, as well as the respective predicted probabilities of each indicator in our latent class analysis. In middle adolescence (age 14–15), 64% of the respondents were likely to be in a latent class we call “favorable development”; 32% were likely to be in the “less favorable development” latent class.

Table 1:

Estimated Prevalence and Conditional Probabilities of Observed Attitudes and Behaviors for Development Classes in Middle and Late Adolescence

| Middle Adolescence (Age 14–15) |

Late Adolescence (Age 17–18) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Favor-able | Less favorable | Favor-able | Less favorable |

|

| Prevalence | 64.13% | 31.71% | 56.71% | 33.14% |

| GPA of C+ or better | 0.85 | 0.34 | 0.98 | 0.53 |

| GPA less than C+ | 0.12 | 0.61 | 0.02 | 0.45 |

| Expects 4 years of college or more | 0.71 | 0.33 | 0.74 | 0.41 |

| Expects less than 4 years of college | 0.19 | 0.54 | 0.2 | 0.52 |

| Does not know educational expectations | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| High intrinsic motivation towards school index | 0.87 | 0.47 | 0.91 | 0.53 |

| Low intrinsic motivation towards school index | 0.12 | 0.52 | 0.09 | 0.46 |

| More school probem behavior | 0.15 | 0.54 | 0.14 | 0.51 |

| Less school problem behavior | 0.84 | 0.41 | 0.85 | 0.49 |

| Had two or fewer drinks in the past 30 days | 0.92 | 0.5 | 0.88 | 0.55 |

| More than 2 drinks in the past 30 days | 0.08 | 0.49 | 0.12 | 0.45 |

| Has not smoked in the past 30 days | 0.92 | 0.39 | 0.89 | 0.48 |

| Has smoked in the past 30 days | 0.07 | 0.61 | 0.1 | 0.52 |

| Greater career certainty | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.9 | 0.85 |

| Less career certainty | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.1 | 0.14 |

| High future expectations index | 0.82 | 0.65 | 0.87 | 0.69 |

| Low future expectations index | 0.18 | 0.35 | 0.11 | 0.29 |

| N | 724 | 258 | 587 | 343 |

In young adulthood, development categories were defined by the following stage-appropriate developmental indicators4: educational attainment (high school or less; vocational or associates degree; some college; or bachelor’s degree or more); currently employed (yes, no); job satisfaction (satisfied; somewhat satisfied; dissatisfied); how one’s current job relates to one’s career goal (yes; it is a stepping stone; no); certainty about eventually achieving one’s career goal (already achieved it; very certain; somewhat or not certain); economic self-sufficiency (100% spouse/self; 25% or more from relatives or government; other); and physical or emotional health problems that interfere with daily activities (no, yes). Table 2 shows the conditional probabilities of observed attitudinal and behavioral indicators of respondents assigned to each class, as well as the likelihood of each class assignment.5

Table 2:

Estimated Prevalence and Conditional Probabilities of Observed Attitudes and Behaviors for Positive Development in Early Adulthood.

| Early Adulthood (age 26–27) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Favorable | Less favorable - Unemployed |

Less favorable - Other |

|

| Prevalence | 46.45% | 11.71% | 41.84% |

| Bachelor’s degree or more | 0.34 | 0.16 | 0.23 |

| Some college education | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.27 |

| Tech/vocational or associates | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.19 |

| High School education or less | 0.18 | 0.50 | 0.31 |

| Employed | 1 | 0.01 | 1 |

| Not employed | 0 | 0.96 | 0 |

| Satisfied with job | 0.81 | 0 | 0.23 |

| Somewhat satisfied with job | 0.17 | 0 | 0.53 |

| Dissatisfied with job | 0.01 | 0 | 0.23 |

| Is pursuing career of choice | 0.63 | 0 | 0.08 |

| Is in a stepping stone job to career | 0.33 | 0 | 0.39 |

| Is not in career of choice | 0.05 | 1 | 0.53 |

| Achieved occupational goal | 0.36 | 0.16 | 0.06 |

| Very certain to achieve occupational goal | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.43 |

| Somewhat/not very certain to achieve goal | 0.19 | 0.4 | 0.42 |

| 100% income from self and spouse | 0.81 | 0.46 | 0.68 |

| 25% of income from government or relatives | 0.13 | 0.42 | 0.25 |

| Source of income: other | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.06 |

| No physical or emotional interference | 0.78 | 0.55 | 0.52 |

| Slight physical or emotional interference | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.32 |

| Experience physical or emotional interference | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.16 |

| N | 353 | 89 | 318 |

In our study, we are less interested in those who remain stable over time than in movement between classes through adolescence and during the transition to adulthood. Table A1 and A2 in the Appendix show movement from middle to late adolescence (freshman to senior year of high school) and movement from late adolescence to early adulthood (senior year of high school to age 26/27). Overall, 28% of respondents move between categories from middle to late adolescence and 46% from late adolescence to early adulthood. In early adulthood, we thus observe less stability than during high school. Forty-eight percent of those who were starting with a less favorable developmental pattern at the end of high school (late adolescence) experience positive development by early adulthood (upward movers); 41 percent of youth in the more favorable latent class in late adolescence experienced negative development eight years later (downward movers).

When considering transition patterns across all three periods (see Table A3 in the supplementary material), we find that 39% of cases (N= 264) with valid responses across all three periods neither move up nor down (they are stable). Thirty-five percent of all students (N= 233) in the sample are one-time downward movers. Among downward movers, most move down after senior year. Thirteen percent (N= 86) are one-time upward movers and another 13% (N= 90) move at each period. However, it must be noted that comparing rates of transition across all three periods may be misleading given that the sample is reduced by more than 50%, due to attrition, and the indicators of positive development change between period 2 (late adolescence) and 3 (early adulthood). We therefore focus our attention on movement from mid to late adolescence, and then from late adolescence to early adulthood.

Independent variables.

The independent variables included hours spent per week on homework, hours spent per week in extra-curricular activities, and number of weekday evenings spent with friends during adolescence. Time spent on homework and extracurricular activities include the weekend, as students may catch up on homework on the weekend and many extracurricular events occur during the weekend. Time spent with peers includes only weekday evenings. Time spent with friends in the evening on weekdays is more likely to be time spent in ‘unstructured’ environments than in the afternoon, since during the latter time organized programs may take place that are not interpreted as “extracurricular activities.” We use averages of reported time spent in activities across four annual waves of data (one for each year of high school). Averaging across years is preferable to relying exclusively on information from one particular year because adolescent use of time can change substantially during high school. Moreover, we use continuous scores of hours spent on an activity as the independent variable of central interest. Arguably, the effect of time use may be sensitive to certain threshold values. For example, while a moderate amount spent on homework may be beneficial, too many late-night hours on homework may be harmful. To test the sensitivity of our time-use measures, we estimated all models with various cut-off points.

We use the average of all four high school years because the survey question can be considered retrospective for the current school year. This means that the number of hours spent on homework, for example, in the last year of high school, reflects time spent on this activity during the school year up to the day of the survey. As such, this measure maintains the temporal ordering of time use measures (independent variable) and developmental outcomes (dependent variable). In addition, we test the robustness of time-use effects by estimating the models with alternate measures (years 1–3, and years 2–3).

Controls

Covariates included background and psychological variables, measured in the first wave, that could affect time spent in activities during high school as well as the multidimensional indicators of positive development in adolescence and early adulthood, reflected in the latent classes. Background variables include parental household income, parental education, race, gender, and family structure. These measures are commonly included to reflect the relative advantages of youth at the beginning of high school. Additional psychological variables include depressed mood, self-esteem, self-mastery, academic self-efficacy, and parental educational expectations for the child. These constructs represent relatively stable, long-term characteristics. All controls could drive movement toward more or less beneficial uses of time, as well as eventual positive development during adolescence and the transition to adulthood; including them in the analyses reduces the risks of endogeneity and time-use effects. Table A6 in the Appendix shows how each variable in the analysis was operationalized.

Table 3 shows descriptive statistics for the independent, dependent, and control variables in the two key analytic samples, representing adolescence and the transition to adulthood (the latter smaller due to sample attrition). On average, the adolescents spent 7.9 hours in extracurricular activities per week; 9.1 hours per week doing homework, and 2.5 evenings per week with peers. Descriptives for all variables are presented for the analytic adolescent sample as well as the analytic transition to adulthood sample (see Table 3). Summary statistics of all model variables are shown by the dependent variable, i.e. movement category (upward, downward, stable high, stable low), in Table A9, Table A10, and Table A11 in the Appendix.

Table 3:

Descriptive Statistics (Analytic Samples)

| Variable | Measurement | Analytic Sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescence (w1–4) |

Transition to adulthood (w 4–12) |

||||||

| % | mean | sd | % | mean | sd | ||

| Dependent Variable | Downward Movement | 10.0 | 15.6 | ||||

| Upward Movement | 18.3 | 30.4 | |||||

| Stable High | 50.8 | 32.6 | |||||

| Stable Low | 20.9 | 21.4 | |||||

| Independent Variables | Homework | 9.1 | 6.4 | 9.1 | 6.3 | ||

| Extracurricular | 7.9 | 6.5 | 7.8 | 6.6 | |||

| Peers | 2.5 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 1.3 | |||

| Socio-Demographic & Socio-Economic Controls | Income4 | ||||||

| Household Income | 6.0 | 2.3 | 9.1 | 6.3 | |||

| Parental Education | |||||||

| Less than HS/HS | 49.0 | 48.9 | |||||

| Some college | 21.1 | 20.9 | |||||

| Community/Junior college | 8.6 | 7.9 | |||||

| 4 year college of more | 21.5 | 22.3 | |||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 53.9 | 57.9 | |||||

| Race | |||||||

| Non-White | 20.3 | 18.9 | |||||

| Country of Birth | |||||||

| Foreign-born | 6.3 | 5.3 | |||||

| Family Structure | |||||||

| Both biological parents | 56.4 | 58.6 | |||||

| Stepfamily | 13.8 | 13.5 | |||||

| Single parent | 23.4 | 22.5 | |||||

| Other | 6.3 | 5.4 | |||||

| Psychological and Socio-Psychological Controls | Depressed Mood Index | 10.3 | 3.1 | 10.4 | 3.1 | ||

| Self Esteem index | 9.1 | 1.5 | 9.1 | 1.5 | |||

| Academic Self-Esteem | 10.6 | 1.9 | 10.6 | 1.9 | |||

| Mastery Index | 13.6 | 2.6 | 13.6 | 2.5 | |||

| Parent Expectations | 4.4 | 1.7 | 4.4 | 1.7 | |||

| Sample Size | 678 | 570 | |||||

Analytic Strategy.

As described above, a latent class analysis of key indicators of positive youth development at three times (freshman year of high school, senior year of high school, and early adulthood) distinguished a “favorable” class and a less favorable class. Then, because “class movement” is categorical, consisting of four categories (stable favorable status, stable unfavorable status, positive development, negative development), we used multinomial logistic regression to assess the likelihood of upward movement and downward movement across adolescence and over the transition to adulthood.

As our key analysis, we estimate two models: The first “adolescence” model predicts the 1) Relative Risk Ratio, or odds, of being an upward mover, i.e. positive development by the end of high school despite initial difficulty; and 2) the Relative Risk Ratio of being a downward mover, negative development over the course of the high school years for those who start out in an initially more favorable position. The second model repeats this analysis for the period from the end of high school to early adulthood (age 26/ 27). We only report results for changes across time rather than stability because these findings, particularly factors promoting movement from less favorable to more favorable outcomes, could inform interventions designed to support positive youth development. Variables measuring time spent in activities during high school are entered in the model simultaneously to ascertain their independent effects net of one another (e.g., the effects of extracurricular time above and beyond time spent with friends and time doing homework). To include the maximal number of cases, we estimate the adolescent model with data from all respondents who were retained by 1991, the last year of high school; we estimate the transition to adulthood model with those remaining by 2000, when most respondents were 26–27 years old.

Robustness Checks.

To assess the sensitivity of the results to our methods, model specification, sample, and missing cases, we conducted a series of robustness checks. First, sample attrition is of concern, particularly at the transition into adulthood. In response, we estimated all models for the earlier stage (mid to late adolescence) using the smaller sample for the “transition to adulthood” model. Second, we re-estimated the model incorporating multiple imputation using chained equations. Third, we checked how sensitive the results were to different codings of time variables. Fourth, we estimated our key models for development between the beginning of high school and early adulthood – spanning a period of 12 years. Fifth, we assessed the impact of including and excluding basic socio-demographic and psychological controls into the model. Our reported results were robust against all the outlined checks (available upon request).

Results

Development from Middle Adolescence to Late Adolescence

The findings shown in Table 4 clearly demonstrate that how students spend their time in high school was associated with their development over the course of high school. Students starting in less favorable positions in the ninth grade were 7% more likely to move upward with each additional hour spent, on average, per week on homework (compared to participants who remained in the less favorable developmental status). The effects for time in extracurricular activities and with peers were not statistically significant.

Table 4:

Multinomial Logistic Regression Estimates (Relative Risk Ratios) of Positive and Negative Development in Adolescence

| Model | Upward Movement (Positive Development) |

Downward Movement (Negative Development) |

|---|---|---|

| Relative Risk Ratio | Relative Risk Ratio | |

| Reference Category | Stable Unfavorable | Stable favorable |

| Homework | 1.066* | 0.975 |

| (0.0299) | (0.0246) | |

| Extracurricular | 1.028 | 0.962 |

| (0.0216) | (0.0236) | |

| Peers | 0.826 | 1.419** |

| (0.0985) | (0.183) | |

| Socio-demographic/ Socio-economic controls | YES | YES |

| (Socio-) Psychological controls | YES | YES |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.145 | 0.145 |

| Observations | 678 | 678 |

Exponentiated coefficients; Standard errors in parentheses

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Note: See Table A7 for a full list of coefficients.

Next, we estimated the effects of time use on the likelihood of negative development, that is, moving to the less favorable developmental condition. Negative development during the course of high school did not depend on homework time or extracurricular involvement. Instead, the effect of time spent with peers was substantial. An additional evening with peers during the week, on average, increases the risk of negative development by 42% (p < .01). The multivariate results are consistent with patterns in the descriptive summary statistics (Table A9–A11 in the Appendix) – Upward movers spent on average more time on homework, on extracurricular activities and less time with peers compared to downward movers and students with stably low development.

Development from Late Adolescence to Early Adulthood

Adolescents’ use of time during high school also predicted positive and negative development during the transition from late adolescence to adulthood. Having spent more hours a week on homework and extracurricular activities increased the likelihood of upward movement (positive development) by age 26/27.

What about late adolescents who started off more favorably? Strikingly, earlier involvement with peers had a large and deleterious effect on their future (see Table 5). Those who had spent one more evening on average a week with friends during high school were 38% (p < .05) more likely to be downward movers. All effects shown in Table 5 are net of key socio-demographic, socio-economic, and psychological variables.

Table 5.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Estimates (Relative Risk Ratios) of Positive and Negative Development during the Transition to Adulthood

| Model | Upward Movement (Positive Development) |

Downward Movement (Negative Development) |

|---|---|---|

| Relative Risk Ratio | Relative Risk Ratio | |

| Reference Category | Stable unfavorable | Stable favorable |

| Homework | 1.098*** | 0.951+ |

| (0.0301) | (0.0258) | |

| Extracurricular | 1.050* | 1.005 |

| (0.0239) | (0.0212) | |

| Peers | 0.804+ | 1.381* |

| (0.0973) | (0.179) | |

| Socio-demographic/ Socio-economic controls | YES | YES |

| (Socio-) Psychological controls | YES | YES |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.116 | 0.116 |

| Observations | 570 | 570 |

Exponentiated coefficients; Standard errors in parentheses

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Note: See Table A8 for a full list of coefficients.

In sum, our findings show that the ways students spend their time in high school are associated with their development, both in the short- and long-term. Homework and, to some degree, extracurricular activities, increase the likelihood of positive development, but are less implicated in the likelihood of moving downward. Time spent with peers increases the likelihood of negative development for youth who started out more favorably both in adolescence and early adulthood. Contrary to our expectations, the effects of time spent in activities on positive development and negative development are not mirror images of one another. We discuss this asymmetry in the next section.

Discussion

This study aimed at extending the literature on time use during high school and positive youth development in several ways. We examined long-term effects at 4 and 12 years after starting high school. We assessed predictors of positive development for those who started high school with unfavorable developmental attributes, as well as predictors of negative development for those who started out as relatively promising. We constructed holistic measures for positive development rather than relying on single outcomes such as educational achievement or delinquency. Lastly, we took into account different types of time use (homework, extracurricular activities, time spent with peers) simultaneously rather than studying each one of them in isolation.

We conceptualized and operationalized the positive development of adolescents and young adults as multifaceted phenomena that encompass several psychological orientations, achievements, and other behaviors. As such, we used a person-centered approach, Latent Class Analysis, to assess positive development. According to Yates and colleagues (2015): “Cumulative risk is best met by cumulative protection efforts that prevent risk, promote resources, and buffer adaptive functioning” (2015, pp.778). Our results suggest that adolescents’ use of time may be a fruitful avenue for such “cumulative protection efforts”.

Most attention in the developmental literature has been directed to understanding risk and vulnerability. Long-term disadvantage and repeated failures (in school, work, with peers, etc.) engender cumulative risk and negative developmental outcomes necessitating multiple protective resources and strategies. But even in dire circumstances, many disadvantaged adolescents manage to thrive by the time they reach adulthood. The transition into adulthood is often portrayed as a “fresh start,” with developmental pathways dependent on exposure to new contexts and the greater capacity to exercise individual agency and autonomy (Arnett, 2007; Crosnoe 2001; Masten, 2015; Settersten & Ray, 2010). Laub and Sampson (2003) draw attention to “knifing off” experiences in the military (see also London and Wilmoth 2016), support from a conforming spouse, and positive work experiences, all of which lead to desistance from crime. However, it is important to acknowledge that continued exposure to disadvantaged contexts, and the cumulative risks they pose, may limit the opportunities many youth have to get a fresh start (Bynner, 2005; Cote, 2008; Dannefer, Kelley-Moore, & Huang, 2016; Furstenberg, 2008; Putnam, 2015). For example, structural factors in high school, such as ability tracking within and across schools, limit individual choices beyond the senior year (e.g. Lucas 2001). Those less favorably positioned, and particularly those who do not achieve a post-secondary degree of any kind (i.e., bachelors’ or associates degrees, vocational certificates) face considerable challenges in the new “gig” economy, in achieving stable employment, independent residence, and economic self-sufficiency. Many join the working “precariat” and become “boomerang children.” In fact, difficult experiences in attaining key markers of adulthood may have led a substantial portion of young people in this study to experience “downward movement” during the transition from adolescence to adulthood.

While “fresh start” and “knifing off” processes signify sharp discontinuities, breaking from the past, the present study sheds light on more mundane, quotidian uses of time (i.e., homework, extracurricular pursuits) that may interrupt negative developmental trajectories. Our results suggest that time use during high school may be one leverage point that opens doors. For example, early decisions about homework and extracurricular activities may influence later decisions about the use of time in post-secondary settings, including continued schooling and occupational pathways that foster continued attainments.

We find that the average time spent on homework and with peers during the four years of high school matter for development. Because students in middle to late adolescence spend a lot of their time in the structured environments under consideration, we would expect homework and extracurricular activities to have immediate effects on positive development over the course of high school. As discussed in the beginning of this article, homework may boost achievement, and extracurricular activities promote the development of non-cognitive skills and social ties. It is reasonable to suppose that the effects of adolescent time use would wane once students leave the structured environment of high school.

Surprisingly, however, the use of time in high school still had predictive power several years later when respondents had reached early adulthood. In the current study, time spent doing homework and, to a lesser extent, in extracurricular activities (in the transition to adulthood period only) increased the probability of positive development. Interestingly, the effects of time spent in these two activities on those who started off more favorably at the beginning of each interval were not statistically significant (at the p < 0.05 level). In other words, time spent in homework and extracurricular activities did not protect students from negative development. But every additional weekday evening spent with peers during high school increased the chances of negative development in late adolescence and in early adulthood.

These results link back to the ongoing and heated debate about “overscheduling” students, which may be a concern only for some students. More time spent doing homework and extracurricular activities had positive effects, in particular, for students starting off less favorably, independent of socio-economic origins and early psychological orientations. In contrast, our findings indicate that doing more homework or more extracurricular activities may not help students to maintain an initial advantage. This implies that policies encouraging homework may be especially important for students facing challenges at the beginning of high school; increasing homework time is likely to affect favorable development across multiple domains over time. Although many have argued against giving too much homework or homework that is merely “busy work” (Marzano & Pickering, 2007), the current research underscores the importance of homework for students starting with a less favorable developmental status, including, for example, at-risk subgroups of students. Rather than shielding at-risk students from homework, providing support for a diverse range of students to complete homework is important (Voorhees, 2011).

Interestingly, the negative effects of evening time spent with peers were significant among youth who started out more favorably in both periods. Spending four evenings a week on average with friends compared to one doubled the probability of negative development. A study of low-income minority children similarly found high levels of problem behaviors (e.g., delinquency, substance use, and peer substance use) for those who spent unstructured time away from home, presumably with peers, compared to unstructured time at home (Wolf et al., 2015). Notwithstanding a body of research that highlights potential benefits from positive friendships (Vitaro et al., 2009), our findings also corroborate a body of work on peer deviance training (e.g., Dishion, Kim, & Tein, 2015). That is, youth are more likely to engage in delinquent behaviors when they are together with other youth in unstructured contexts (Dodge et al., 2008; Osgood and Anderson, 2004).

Time spent in extracurricular activities during high school predicted upward movement, or a positive developmental pathway, over the transition to adulthood. Although extra-curricular activities are a possible support mechanism for young people, policy makers are cautioned against simply grouping vulnerable youth together in after school activities (Dodge et al., 2008). Instead, mixed groups, structured activities, and connections with adult mentors are key components that contribute to positive development in extra-curricular contexts. Additionally, practices that discourage at-risk students from engaging in extra-curricular activities should be reexamined, particularly fees that may be prohibitive to families from lower socio-economic backgrounds (Putnam, 2015).

While our design was not able to directly test explanations of why time spent in homework, extracurricular activities, and peers has such strong and long-lasting statistical “effects,” we offer a number of potential mechanisms that could explain our key results. The persistent effects of adolescents’ use of time can be explained if distinct activities are understood as opportunity structures for non-cognitive skill and habit formation. The impacts of non-cognitive skills (such as self-regulation, motivation, values, etc.) on life outcomes are key interests of psychologists; such interests are increasingly spreading to other fields such as economics (Heckman, Stixrud, & Urzua, 2006) and sociology (Johnson & Mortimer, 2011; Vuolo, Staff, & Mortimer, 2012). While homework may be primarily intended to improve cognitive skills, increase learning, raise grades and heighten achievement, homework time may also contribute to the development of discipline, self-regulation, achievement motivation, time discounting preferences, and delayed gratification (Bempechat, 2004; Ramdass & Zimmerman, 2011). Homework may also teach high school students how to acquire information, solve problems, and learn new things, and these lessons stay with them after they leave school. Extracurricular activities constitute a venue for developing social and cooperative skills, making friends, setting goals to be pursued in a vigorous and systematic manner, and acquiring positive adult role models (Mahoney et al., 2005). Each of these processes sets the stage for positive development in adulthood despite challenges.

The negative effect of time with peers in largely unsupervised environments is well established (McHale et al., 2001; Osgood & Anderson, 2004; Vandell et al., 2015). Structured lives with more routine, organized activities reduce opportunity for deviant behavior and enhance social control (Cohen & Felson, 1979; Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990; Hirschi, 1969). Organized processes constructed and supervised by adults (e.g. homework, extracurricular activities) constrain the violation of social norms, whereas unsupervised evening time with peers may boost the opportunity for delinquency (Dodge, Dishion, & Lansford, 2007). The absence of adult control enables adolescents to pursue peer norms that are often detrimental to long-term development, achievement, and progress. These norms may condone or support deviant behavior, a lack of effort in school, disengagement from conventional activities and contexts, and detachment from positive adult role models.

Our study faces certain limitations. First, our sample is based on a panel of youth in a single Midwest community in the US. While any judgment about the applicability of our findings to other settings is beyond the scope of this study, we encourage similar research in other contexts to explore the external validity of our results. International comparisons may be of particular interest as educational regimes and the transition to the labor market vary systematically and dramatically across societies. Some countries, such as Germany, have tightly regulated school-to-work pathways. Since individuals are channeled into vocational and college preparatory tracks at an early age, and because these trajectories lead directly into work or post-secondary education, discretionary experiences during high school such as the ones studied here (extracurricular activities, peer involvements) may have less impact on developmental and attainment outcomes. Other countries, such as Israel, have mandatory conscription which may present an opportunity for a “fresh start” for some youth with less favorable development during high school. Furthermore, it is important to note that positive development is socio-historically constructed and highly dependent on place and time (see Dannefer, 1984; Mortimer & Moen, 2016).

Second, use of self-reported hours or evenings spent on each activity raises threats of measurement error. It does not reveal the quality of the activity or how the individual engages with the opportunity structure provided by the use of time (Hirsch et al., 2011, Vandell et al., 2015). Unfortunately, we lack more detailed information about the features of homework or extracurricular activities that might yield the most beneficial results, and the kinds of peer activities, or characteristics of peers, that may be most harmful. Future studies are needed to address these nuances and to understand the mechanisms through which time use during high school contributes to positive or negative development.

Third, as in most observational studies, we face issues of unobserved heterogeneity. There may be unobserved student characteristics that drive both patterns of time investment in activities and patterns of development. We have tried to address this issue by identifying and controlling a wide range of plausible social background and psychological confounders. Lastly, more research is needed on the interaction of time use with smart phone use and social media (see e.g. Twenge et al., 2018). Given the period of our data collection, we were not able to capture this new development.

Despite these limitations, our study confirms previous evidence on the positive effects of homework and extracurricular activities and the potentially negative effects of peers on development in mid-to-late adolescence. We extend this evidence by showing that time use during high school predicts developmental outcomes well beyond the high school years, into early adulthood. Findings indicate that homework should be promoted, especially for adolescents who are not doing as well as their peers upon entry to high school. However, unsupervised time with peers appears to be detrimental to the positive development of all mid-adolescents, irrespective of their initial starting positions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Throughout this paper, we do not use the term, effects, to suggest causal relationships given that the study design does not ensure causality. Here effects refer to statistically significant associations that have been adjusted for a wide range of prior and intervening factors.

The Latent Class Analysis (LCA) was performed using the Stata package (Lanza, Dziak, Huang, Wanger, and Collins 2015). According to Nylund, Asparouhov, and Muthen (2007), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and the Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) are good indicators of the number of classes to retain. We chose the number of latent classes corresponding to the lowest BIC. Additionally, high entropy suggests that observations fit well into a defined number of classes. Clark and Muthen (2009) claim that an entropy of 0.8 is considered high entropy. For each of our chosen models, the entropy scores ranged from 0.77 to 0.85. The highest entropy scores for each model corresponded to the lowest BIC. The Log-Likelihood, BIC, and Entropy R-Squared for each LCA specification are reported in Table A4 in the Appendix. A review of all variables included, as well as their operationalizations, are reported in Table A5 of the Appendix.

Appendix Table A4 shows the log-likelihood estimates and fit statistics, indicating two latent classes in middle adolescence, two in late adolescence, and three in early adulthood.

We acknowledge that stage-appropriate indicators are social constructions that may vary largely across time and space (see Dannefer (1984); Mortimer, J. & Moen, P. (2016))

This stage includes three classes: one clearly “favorable” (with higher probability of an advantageous position on each indicator and a prevalence of 46%) and two less “favorable.” The distinguishing feature of one less favorable class is an absence of employment (with a prevalence of 12%); the other is employed, but has other less favorable characteristics (prevalence of 42%). Due to the similarity between the classes with respect to our intended measure of development and to simplify the analysis, we combine the two less favorable classes into a single group. Employment in young adulthood is generally more fluid and unstable than later in the work career, and this is especially the case for those with fewer educational credentials. It is therefore not surprising to find two latent classes, both having less favorable characteristics, which are distinguished mainly by the presence of employment. The more favorable group has stronger educational credentials than either of the less favorable ones. Respondents in this class are also more likely to be economically self-sufficient, to have no physical or mental problems that interfere with daily routines, and (compared to those in the less favorable employed group) to be more satisfied with their work and more optimistic about their career progress.

Contributor Information

Jasper Tjaden, Global Migration Data Analysis Centre, International Organization for Migration.

Dom Rolando, Department of Family, Youth & Community Services, University of Florida-Gainesville.

Jennifer Doty, Department of Family, Youth & Community Services, University of Florida-Gainesville.

Jeylan T. Mortimer, Department of Sociology, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

References

- Alvord MK, & Grados JJ (2005). Enhancing resilience in children: a proactive approach. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(3), 238–245. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Hoffman JH, Welte JW, Farrell MP, & Dintcheff BA (2007). Adolescents’ time use: Effects on substance use, delinquency and sexual activity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(5), 697–710. [Google Scholar]

- Bartko WT, & Eccles JS (2003). Adolescent participation in structured and unstructured activities: A person-oriented analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32(4), 233–241. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S, & Kalish N (2006). The case against homework: How homework is hurting our children and what we can do about it. New York, NY: Crown. [Google Scholar]

- Bempechat J (2004). The motivational benefits of homework: A social-cognitive perspective. Theory into Practice, 43(3), 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Broh BA (2002). Linking extracurricular programming to academic achievement: Who benefits and why? Sociology of Education 75(1), 69–95. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JC, Mezzacappa E, & Beardslee WR (2003). Characteristics of resilient youths living in poverty: The role of self-regulatory processes. Development and Psychopathology, 15(1), 139–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busseri MA, Rose-Krasnor L, Willoughby T, & Chalmers H (2006). A longitudinal examination of breadth and intensity of youth activity involvement and successful development. Developmental Psychology, 42(6), 1313–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bynner J (2005). Rethinking the youth phase of the life-course: The case for emerging adulthood?” Journal of Youth Studies, 9, 367–384. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho DE, & Fuligni AJ (2015). Extracurricular participation among adolescents from immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(6), 1251–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SL, & Muthén B (2009). Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. Retrieved from https://www.statmodel.com/download/relatinglca.pdf

- Cohen LE, & Felson M (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 588–608. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Robinson JC, & Patall EA (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987–2003. Review of Educational Research, 76(1), 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Cote J (2008). Changes in the transition to adulthood in the U.K. and Canada: The role of structure and agency in emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth Studies 11, 251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R (2011). Fitting In, Standing Out: Navigating the Social Challenges of High School to Get an Education. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer D (1984). Adult development and social theory: A paradigmatic reappraisal. American Sociological Review, 49 (1): 100–116. [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer D, Kelley-Moore J, & Huang W (2016). Opening the social: Sociological imagination in life course studies In Shanahan MJ, Mortimer JT, & Johnson MK (Eds.), Handbook of the Life Course, Vol. II, pp.87–110. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Darling N (2005). Participation in extracurricular activities and adolescent adjustment: Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(5), 493–505. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kim H, & Tein J-Y (2015). Friendship and adolescent problem behavior: deviancy training and coercive joining as dynamic mediators In Beauchaine Theodore P. & Hinshaw Stephen P. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Externalizing Spectrum Disorders (pp. 303–312). Oxford/ New York: Oxford Universitz Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, & Lansford JE (2007). Deviant peer influences in programs for youth: Problems and solutions. New York/ London: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, & Pachan M (2010). A meta‐analysis of after‐school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3–4), 294–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Barber BL, Stone M, & Hunt J (2003). Extracurricular activities and adolescent development. Journal of Social Issues, 59(4), 865–889. [Google Scholar]

- Farb AF, & Matjasko JL (2012). Recent advances in research on school-based extracurricular activities and adolescent development. Developmental Review, 32(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S, & Zimmerman MA (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review Public Health, 26(1), 399–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks JA, & Eccles JS (2006). Is extracurricular participation associated with beneficial outcomes? Concurrent and longitudinal relations. Developmental Psychology, 42(4), 698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks JA, & Simpkins SD (2012). Promoting Positive Youth Development through organized after‐school activities: Taking a closer look at participation of ethnic minority youth. Child Development Perspectives, 6(3), 280–287. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF (2008). The Intersections of Social Class and the Transition to Adulthood. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 119, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs BG, Erickson LD, Dufur MJ, & Miles A (2015). Extracurricular associations and college enrollment. Social Science Research, 50(1), 367–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson MR, & Hirschi T (1990). A general theory of crime. Standord, CL: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen DM, Larson RW, & Dworkin JB (2003). What adolescents learn in organized youth activities: A survey of self-reported developmental experiences. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13(1), 25–55. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ, Stixrud J, & Urzua S (2006). The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior. Journal of Labor Economics, 24(1), 411–482. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch BJ, Deutsch NL & DuBois DL (2011). After-school centers and youth development: Case studies of success and failure: Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T (1969). Causes of delinquency: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK & Mortimer JT 2011. Origins and Outcomes of Judgments about Work. Social Forces, 89, 1239–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interagency Working Group on Youth Programs. (n.d.). Positive Youth Development. Retrieved from https://youth.gov/youth-topics/positive-youth-development [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Dziak JJ, Huang L, Wagner AT, & Collins LM (2015). LCA Stata plugin users’ guide (Version 1.2) University Park: The Methodology Center, Penn State. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R (1994). Youth organizations, hobbies, and sports as developmental contexts In Silbereisen RK & Todt E (Eds.), Adolescence in context: The interplay of family, school, peers, and work in adjustment (pp. 46–65). New York: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R (1999). How children and adolescents spend time across the world: work, play, and developmental opportunities. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), 701–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American psychologist, 55(1), 170–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laub JH, & Sampson RJ (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives: Delinquent boys to age 70. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lauer PA, Akiba M, Wilkerson SB, Apthorp HS, Snow D, & Martin-Glenn ML (2006). Out-of-school-time programs: A meta-analysis of effects for at-risk students. Review of Educational Research, 76(2), 275–313. [Google Scholar]

- Leman PJ, Smith EP, Petersen AC, SRCD Ethnic–Racial Issues and International Committees, Seaton E, Cabrera N, ... & Leman P (2017). Introduction to the special section of Child Development on positive youth development in diverse and global contexts. Child development, 88(4), 1039–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM (2017). Commentary: Studying and Testing the Positive Youth Development Model: A Tale of Two Approaches. Child Development., 88(4), 1183–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM, Abo-zena MM, Bebiroglu N, Brittian A, Lynch AD, & Issac SS (2009). Positive youth development: Contemporary theoretical perspectives In DiClemente RJ, Santelli JS & Crosby RA (Eds.), Adolescent health: Understanding and preventing risk behaviors. (pp. 116–130). New York, NY: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, & Becker B (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London AS, & Wilmoth JM. (2016). Military service in lives: Where do we go from here? In Shanahan MJ, Mortimer JT, & Johnson MK (Eds.), Handbook of the Life Course, Vol. II, pp.277–300. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Crossman EJ, & Small PJ (2015). Resilience and adversity In Lerner Richard M. (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (pp. 1–40). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod J (1987). Ain’t no makin’it: Leveled aspirations in a low-income neighborhood. Westview Press, Boulder. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney JL (2000). School extracurricular activity participation as a moderator in the development of antisocial patterns. Child Development, 71(2), 502–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney JL, Larson RW, Eccles JS, & Lord H (2005). Organized activities as developmental contexts for children and adolescents In Mahoney JL, Larson RW, & Eccles JS (Eds.), Organized activities as contexts of development: Extracurricular activities, after-school and community programs (pp. 3–22). London: Lawrence Erlbaum Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Maimon D, & Browning CR (2010). Unstructured socializing, collective efficacy, and violant behaviour among urban youth. Criminology, 48(2), 443–474. [Google Scholar]

- Marzano RJ, & Pickering DJ (2007). Special topic: The case for and against homework. Educational Leadership, 64(6), 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS (2015). Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, & Coatsworth JD (1998). The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments: Lessons from research on successful children. American Psychologist, 53(2), 205–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, & Tucker CJ (2001). Free‐time activities in middle childhood: Links with adjustment in early adolescence. Child Development, 72(6), 1764–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JT (2003). Working and Growing Up in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JT (2012). The evolution, contributions, and prospects of the Youth Development Study: An investigation in life course social psychology. Social Psychology Quarterly, 75(1), 5–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer J & Moen P (2016). The Changing Social Construction of Age and the Life Course: Precarious Identity and Enactment of ‘Early’ and ‘Encore’ Stages of Adulthood” Pp. 111–129 in Handbook of the Life Course, Vol 2 NewYork: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, & Muthén BO (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(4), 535–569 [Google Scholar]

- Oberle E, Schonert-Reichl KA, Thomson KC (2010). Understanding the link between social and emotional well-being and peer relations in early adolescence: Gender-specific predictors of peer acceptance. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 1330=1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, & Anderson AL (2004). Unstructured socializing and rates of delinquency. Criminology, 42(3), 519–550. [Google Scholar]

- Peck SC, Roeser RW, Zarrett N, & Eccles JS (2008). Exploring the Roles of Extracurricular Activity Quantity and Quality in the Educational Resilience of Vulnerable Adolescents: Variable‐and Pattern‐Centered Approaches. Journal of Social Issues, 64(1), 135–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD (2015). Our kids: The American dream in crisis. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Ramdass D, & Zimmerman BJ (2011). Developing self-regulation skills: The important role of homework. Journal of Advanced Academics, 22(2), 194–218. [Google Scholar]

- Sacker A, & Schoon I (2007). Educational resilience in later life: Resources and assets in adolescence and return to education after leaving school at age 16. Social Science Research, 36(3), 873–896. [Google Scholar]

- Sesma A, Mannes M, & Scales PC (2013). Positive adaptation, resilience and the developmental assets framework In Fernando C & Ferrari M (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 427–442). Springer, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Settersten R, & Ray BE (2010). Not quite adults: Why 20-somethings are choosing a slower path to adulthood, and why it’s good for everyone. New York: :Bantam Books. [Google Scholar]

- Shulruf B (2010). Do extra-curricular activities in schools improve educational outcomes? A critical review and meta-analysis of the literature. International Review of Education, 56(5–6), 591–612. [Google Scholar]

- Simpkins S, Eccles J, & Becnel J (2008). The role of breadth in activity participation and friends in adolescents’ adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 44(4), 1081–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troutman KP, & Dufur MJ (2007). From High School Jocks to College Grads Assessing the Long-Term Effects of High School Sport Participation on Females’ Educational Attainment. Youth & Society, 38(4), 443–462. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Martin GN, & Campbell WK (2018). Decreases in Psychological Well-Being Among American Adolescents After 2012 and Links to Screen Time During the Rise of Smartphone Technology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/emo0000403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. (2007). Putting positive youth development into practice: A resource guide. Wahsington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Vandell DL, Larson RW, Mahoney JL, & Watts TW (2015). Children’s organized activities In Lerner RM, Bornstein MH, & Leventhal T (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (7 ed., Vol. 4, pp. 305–344). New Jersey: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Viau A, Denault A-S, & Poulin F (2015). Organized activities during high school and adjustment one year post high school: Identifying social mediators. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(8), 1638–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Boivin M, & Bukowski WM (2009).The role of friendship in child and adolescent psychosocial development In Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, & Laursen B (Eds.), Social, emotional, and personality development in context. Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 568–585). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Voorhees S (2011). Why the dog eats Nikki’s homework: Making informed assignment decisions. Reading Teacher, 64(5), 363–367. doi: 10.1598/RT.64.5.8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vuolo M, Staff J, Mortimer JT (2012). Weathering the great recession: Psychological and behavioral trajectories in the transition from school to work. Developmental Psychology, 48: 1759–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR (2009). Peers and academic functioning at school In Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, & Laursen B (Eds.), Social, emotional, and personality development in context. Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 531–547). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S, Aber JL, & Morris PA (2015). Patterns of time use among low-income urban minority adolescents and associations with academic outcomes and problem behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(6), 1208–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates TM, Tyrell F, & Masten AS (2015). Resilience theory and the rractice of positive psychology from individuals to societies In Joseph S (Ed.), Positive Psychology in Practice: Promoting Human Flourishing in Work, Health, Education, and Everyday Life (2 ed., pp. 773–788). New Jersey: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Zaff JF, Moore KA, Papillo AR, & Williams S (2003). Implications of extracurricular activity participation during adolescence on positive outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Research, 18(6), 599–630. [Google Scholar]

- Zolkoski SM, & Bullock LM (2012). Resilience in children and youth: A review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(12), 2295–2303. [Google Scholar]

- Zuzanek J (2009). Students’ study Ttime and their “homework problem”. Social Indicators Research, 93(1), 111–115. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.