Abstract

Objectives

To identify sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of callers’ making repeated calls within 48 hours to a medical helpline, compared with those who only call once.

Setting

In the Capital Region of Denmark people with acute, non-life-threatening illnesses or injuries are triaged through a single-tier medical helpline for acute, healthcare services.

Participants

People who called the medical helpline between 18 January and 9 February 2017 were invited to participate in the survey. During the period, 38 787 calls were handled and 12 902 agreed to participate. Calls were excluded because of the temporary civil registration number (n=78), the call was not made by the patient or a close relative (n=699), or survey responses were incomplete (n=19). Hence, the analysis included 12 106 calls, representing 11.131 callers’ making single calls and 464 callers’ making two or more calls within 48 hours. Callers’ data (age, sex and caller identification) were collected from the medical helpline’s electronic records. Data were enriched using the callers’ self-rated health, self-evaluated degree of worry, and registry data on income, ethnicity and comorbidities. The OR for making repeated calls was calculated in a crude, sex-adjusted and age-adjusted analysis and in a mutually adjusted analysis.

Results

The crude logistic regression analysis showed that age, self-rated health, self-evaluated degree of worry, income, ethnicity and comorbidities were significantly associated with making repeated calls. In the mutually adjusted analysis associations decreased, however, odds ratios remained significantly decreased for callers with a household income in the middle (OR=0.71;95% CI 0.54 to 0.92) or highest (OR=0.68;95% CI 0.48 to 0.96) quartiles, whereas immigrants had borderline significantly increased OR (OR=1.34;95% CI 0.96 to 1.86) for making repeated calls.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that income and ethnicity are potential determinants of callers’ need to make additional calls within 48 hours to a medical helpline with triage function.

Keywords: organisation of health services, quality In health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The characteristics of callers’ who make repeated calls to a medical helpline with triage function have not previously been studied.

This study provided an overview of the frequency of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics and its association with callers’ who repeatedly call a medical helpline, compared with those who only call once.

The sociodemographic and health-related characteristics influence the odds for making repeated calls to a medical helpline was calculated in sex-adjusted and age-adjusted analysis and in a mutually adjusted logistic regression analysis.

The sociodemographic characteristics influence on making repeated calls compared with the health-related characteristics is illustrated.

In the present study, 33.3% of the invited study population agreed to participate in the survey, possibly introducing selection bias.

Introduction

In the last decade, out-of-hours (OOH) primary care has taken place in large-scale organisations in various countries,1 and telephone triage is a common feature of OOH services, serving to determine the level of urgency and healthcare needed.2 In the Capital Region of Denmark, people with acute, non-life-threatening illnesses or injuries are encouraged to call a single-tier telephone preadmission evaluation and triage service called medical helpline 1813 (MH1813).3 Triage results in one of two possible outcomes: (1): face-to-face consultation (home visit, hospital-based emergency department/acute care clinic or hospitalisation) or (2) medical telephone advice (self-care, contact general practitioner or prescriptions).4 Telephone triage, however, is not straight forward, and a lack of visual cues compromises clinical decision making.4 The call handler creates a picture of the caller using non-verbal cues, such as tone of voice, diction and background noises to help determine the urgency of the call.5 When using this strategy, call handlers subconsciously incorporate their own preconceptions and stereotypes,6 not to mention professional and personal experience.6 An additional complicating factor in the clinical decision making is that the call handler must simultaneously act as a gatekeeper and as a caregiver.7

Furthermore, when telephone medical helplines serve as a single-tier entry point for face-to-face consultations, callers must have the ability to describe symptoms sufficiently and follow the given medical advice adequately;2 8 however, the callers’ ability to do so may vary.9 A lack of ability may increase the risk of receiving inaccurate advice or incorrect triage outcome,10 potentially increasing the need to make additional calls.

There is a lack of studies on whether sociodemographic and health-related characteristics are related to repeated calls to medical helplines. Existing literature on users of OOH services with face-to-face consultations (eg, emergency departments) has shown that sociodemographic and health-related characteristics are associated with repeat visits11–14 and that specific characteristics can add to the risk of making errors in clinical decision making.11 15–18 Frequent use of OOH services is associated with the presence of comorbidities,8 19 whereas low, self-rated health (SRH) is associated with frequent general practice visits in Denmark.20 Similarly, immigrants use the emergency room more often than ethnic Danes.21

Identification of the sociodemographic and health-related determinants for making repeated calls to medical helplines may help prevent errors in clinical decision making, preventing overtriage or undertriage in medical helplines. In addition, by gaining insight into underlying determinants to perform repeated calls, policy-makers might be provided with knowledge that potentially helps prevent the portion of repeated calls that may be unnecessary and resource demanding.

The aim of this paper was to identify the sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of individuals making repeated calls to a medical helpline within 48 hours, compared with those who only call once.

Methods

Design

A prospective cohort study was conducted of individuals who repeatedly called MH1813 within 48 hours of their initial call (n=464) compared with those who only called once (n=11 131). The differences between the two groups were examined in relation to sociodemographic (income and ethnicity) and health-related characteristics (age, sex, degree of comorbidities, SRH and self-evaluated degree of worry (DOW)). We also analysed the influence of the details on the initial call (time of call and caller) to MH1813.

Setting

The study was conducted at Emergency Medical Services Copenhagen in the Capital Region of Denmark, which provides acute and emergency services for 1.7 million people. Access to public medical healthcare services is free of charge in Denmark. MH1813 is a round-the-clock, single-tier entry point for acute healthcare for people with acute, non-life-threatening illnesses or injuries and encourages people to call for preassessment and possible triage to a face-to-face consultation outside the office hours of general practitioners.3 A separate three-digit emergency number, 112, is available for potentially life-threatening symptoms/injuries and to request an ambulance.

The MH1813 medical staff handle approximately 1 million calls annually, 4% of which are repeat calls within 48 hours of the initial call.22 Call handlers at MH1813 comprise nurses (80%) and physicians (20%), who use an electronic decision support tool to determine the level of urgency and healthcare needed.3

The present study is embedded within a wider trial examining DOW as a predictor for the use of acute healthcare services and is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov, file no. NCT02979457.

Approvals and registration

This study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (2012-58-0004) and Statistics Denmark. Approval from the Scientific Ethics Review Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark was requested but no permission is required (H-15016323). Informed oral consent was obtained from all study participants.

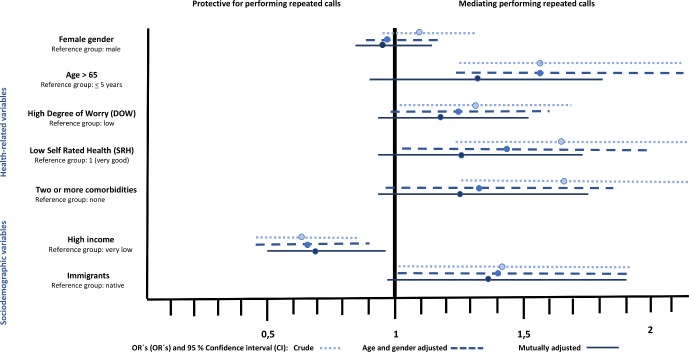

Participants

Anyone who called MH1813 between 18 January and 9 February 2017 was invited to participate in a survey. If the caller agreed to participate, the survey was completed prior to speaking with the call handler. During this period, 38 787 people called, 12 902 of whom agreed to participate in the study (33.26%). Callers were excluded if they had a temporary civil registration number (eg, tourists) (n=78); the call was not made by the patient or a close relative to the patient (eg, primary care nurses) (n=699); or survey responses were incomplete (n=19), leaving 12 106 calls for analysis, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of calls included.

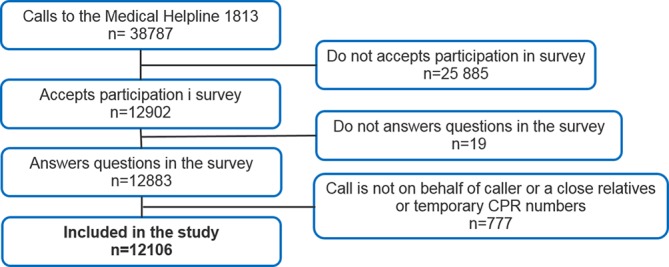

Initially we divided the calls included in the study cohort into the following four sequences: (1) one-time callers, where the individual only called once within 48 hours (n=11 131); (2) initial call plus the occurrence of repeated call (n=464); (3) first repeated call within 48 hours of the initial call (n=464); and (4) two or more repeated calls within 48 hours of the initial call (n=47). Figure 2 illustrates the four sequences. For the analysis, however, we divided the study data into two main groups: one-time calls (n=11 131) and the initial call to the repeated calls (n=464).

Figure 2.

Division of the included calls into four strata: one-time callers, initial calls plus occurrence of repeated call, first repeated call within 48 hours and two or more repeated calls within 48 hours of the initial call.

Exposure

Data on sex (male, female) and age (≤5, 6–18, 19–65 and >65 years) were retrieved from MH1813’s electronic patient record. This classification of age was selected based on disease patterns in the respective age groups (children, adolescents, adults and the elderly). Time of call (workday and weekend) was retrieved from the same electronic patient record.

Prior to speaking with the call handler, caller responses to three survey questions were collected: self-evaluated DOW (1=low, 2=middle, 3=high) and SRH (on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1=very good and 5=very poor) and who the caller was (patient, close relative to the patient and other). A recorded message presented the survey questions, which callers responded to on a numeric scale using their phone keypad.

DOW represents a self-evaluated measure of the caller’s level of worry concerning the acuteness of their health situation. Although this scale has not been validated a previous study showed that people using OOH services were able to rate their DOW as a measure of the self-evaluated level of urgency at MH1813.23 24

SRH reflects an individual’s own assessment of their health according to their own definition of health. SRH is a validated scale that predicts morbidity and mortality,25 and also prompts people to seek primary care more frequently.20 26

All residents of Denmark are assigned a personal identification number at birth or on officially registering in the Danish Civil Registration System.27 28 This number makes it possible to conduct individual follow-up in national registries. Call data on each caller were merged with data on annual household income divided into four quartiles (very low, low, middle and high) and ethnicity (natives, immigrants and descendants of immigrants) from Statistics Denmark’s registries.29 Data on comorbidity from the past 10 years (Charlson score: 0=no comorbidities, 1=one comorbidity, 2=two or more comorbidities) were obtained from the Danish National Patient Registry,30 31 where morbidity is registered continuously for all patients in Danish hospitals. The validity of the Danish National Patient Registry is estimated at 66%–99% compared with a journal audit.32

Analysis

A descriptive baseline analysis of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics was performed using frequency distributions (number and percentage). Logistic regression analyses were used to calculate crude, age -adjusted and sex-adjusted and mutually adjusted (for age, sex, ethnicity, income, call time, caller, DOW, SRH and Charlson comorbidity score) ORs with 95% CIs for repeat callers (n=464) versus one-time callers (n=11 131).

Due to the limited number of missing values in the data collection (n=106 in SRH), they were excluded from the analysis because their absence was considered random.

The statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1.

Results

The analysis included 11 595 callers, 4% (n=464) of whom represented callers who made repeated calls within 48 hours of their initial call.

The results of the crude analysis identified an association between repeated calls to MH1813 within 48 hours and the callers’ sociodemographic and health-related characteristics, as well as the details related to the call. However, these associations decreased in the mutually adjusted analysis, indicating that sociodemographic and health-related characteristics have a reinforcing effect on the need to make an additional call.

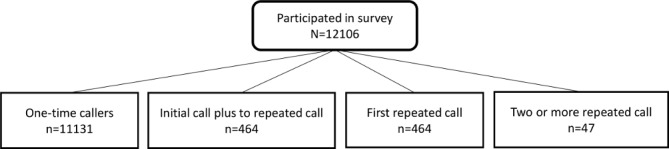

A comparison of the results in the mutually adjusted analysis showed that sociodemographic variables have a stronger association with the odds of making a repeat call within 48 hours compared with the health-related variables (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Showing Crude, age-adjusted and gender-adjusted, and mutually adjusted ORs with 95% CI for health-related and sociodemographic characteristics for repeated calls <48 hours (n=464) compared with single calls (n=11 131) to the medical helpline.

Findings in the mutually adjusted analysis suggest that income and ethnicity are potential determinants for individuals need to make repeated calls within 48 hours to a medical helpline with triage function.

Association of health-related characteristics with making repeated calls

The crude analysis on the health-related characteristics (age, sex, DOW, SRH and Charlson comorbidity score) indicated that all characteristics, except sex, were significantly associated with the odds of making repeated calls. The strongest positive association for making a repeat call was a Charlson comorbidity score of 2 compared with a score of 0 (OR=1.66; 95% CI 1.26 to 2.19) (table 1).

Table 1.

Crude, adjusted and full model adjusted ORs with 95% CIs for health-related characteristics for repeated calls <48 hours (N=464) compared with one-time calls (N=11 131) to the telephone triage

| One-time callers (N=11 131) |

Repeat callers (N=464) |

Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) * | Mutually adjusted OR (95% CI)† | |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 5116 (45.96) | 205 (44.18) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 6015 (54.04) | 259 (55.82) | 1.08 (0.89 to 1.29) | 0.96 (0.77 to 1.13) | 0.94 (0.78 to 1.14) |

| Age, n (%) | |||||

| Mean | 30.37 | 34.57 | |||

| ≤5 years | 2576 (23.14) | 106 (22.84) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥6 and ≤18 years | 1915 (17.20) | 63 (13.58) | 0.79 (0.58 to 1.09) | 0.79 (0.58 to 1.09) | 0.95 (0.67 to 1.33) |

| ≥19 and ≤65 years | 5222 (46.91) | 202 (43.75) | 0.95 (0.74 to 1.20) | 0.94 (0.74 to 1.19) | 0.80 (0.59 to 1.08) |

| >65 years | 1428 (12.74) | 92 (19.83) | 1.58 (1.18 to 2.10) | 1.57 (1.17 to 2.09) | 1.24 (0.85 to 1.81) |

| Degree of worry, n (%) | |||||

| Low | 3396 (30.51) | 132 (28.50) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Middle | 4026 (36.17) | 141 (30.39) | 0.90 (0.71 to 1.15) | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.13) | 0.88 (0.69 to 1.23) |

| High | 3709 (33.32) | 191 (41.16) | 1.33 (1.06 to 1.66) | 1.23 (0.98 to 1.55) | 1.13 (0.89 to 1.45) |

| Self-rated health, n (%) | |||||

| 1 (very good) | 2077 (18.84) | 79 (17.10) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2685 (24.35) | 107 (23.16) | 1.05 (0.78 to 1.41) | 1.02 (0.76 to 1.37) | 1.02 (0.75 to 1.37) |

| 3 | 2433 (22.07) | 89 (19.26) | 0.96 (0.71 to 1.31) | 0.90 (0.66 to 1.23) | 0.87 (0.63 to 1.19) |

| 4 | 2208 (20.03) | 86 (18.61) | 1.02 (0.75 to 1.39) | 0.93 (0.68 to 1.28) | 0.88 (0.63 to 1.21) |

| 5 (very poor) | 1622 (14.71) | 101 (21.86) | 1.64 (1.21 to 2.21) | 1.43 (1.05 to 1.96) | 1.26 (0.91 to 1.75) |

| Charlson comorbidity score, n (%) | |||||

| 0 (none comorbidities) | 9045 (81.26) | 351 (75.65) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 (one comorbidities) | 1108 (9.95) | 50 (10.78) | 1.16 (0.86 to 1.57) | 1.06 (0.77 to 1.15) | 1.02 (0.74 to 1.40) |

| 2 (two or more comorbidities) | 978 (8.79) | 63 (13.58) | 1.66 (1.26 to 2.19) | 1.33 (0.96 to 1.84) | 1.27 (0.91 to 1.77) |

*Adjusted for age and sex.

†Adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, income, call time, caller, degree of worry, self-rated health and Charlson comorbidity score.

In the mutually adjusted logistic regression analysis, the ORs decreased somewhat, and none of the health-related characteristics were significantly associated with the odds of performing a repeated call (table 1).

Association of sociodemographic characteristics with making repeated calls

The crude analysis on the sociodemographic characteristics (household income and ethnicity) indicated that immigrant status increased the odds of performing a repeated call, whereas having a middle or a high household income decreased the odds of performing a repeated call (table 2).

Table 2.

Crude, adjusted and full model adjusted ORs with 95% CIs for sociodemographic characteristics for repeated calls <48 hours (N=464) compared with one-time calls (N=11 131) to the telephone triage

| One-time callers (N=11 131) |

Repeat callers (N=464) |

Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) * | Mutually adjusted OR (95% CI)† | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||

| Natives | 9488 (82.24) | 380 (82.24) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Immigrants | 833 (7.22) | 47 (10.17) | 1.41 (1.03 to 1.93) | 1.40 (1.02 to 1.93) | 1.34 (0.96 to 1.86) |

| Descendants of immigrants | 754 (6.54) | 35 (7.57) | 1.16 (0.81 to 1.65) | 1.27 (0.89 to 1.82) | 1.14 (0.79 to 1.65) |

| Annual household income, n (%) | |||||

| Very low | 3151 (28.31) | 156 (33.62) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Low | 3139 (28.20) | 147 (31.68) | 0.95 (0.75 to 1.19) | 0.82 (0.64 to 1.06) | 0.81 (0.63 to 1.05) |

| Middle | 3198 (28.73) | 110 (23.71) | 0.69 (0.54 to 0.89) | 1.03 (0.80 to 1.33) | 0.71 (0.54 to 0.92) |

| High | 1643 (14.76) | 51 (10.99) | 0.63 (0.46 to 0.87) | 0.65 (0.46 to 0.91) | 0.68 (0.48 to 0.96) |

*Adjusted for age and sex.

†Adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, income, call time, caller, degree of worry, self-rated health and Charlson comorbidity score.

In the mutually adjusted logistic regression analysis, annual income significantly decreased the odds of performing a repeated call for callers’ with household income in the middle quartile (OR=0.71; 95% CI 0.54 to 0.92) and highest quartiles (OR=0.68; 95% CI 0.48 to 0.96), compared with callers’ with household income in the lowest quartile (table 2). This result indicates that low income is a potential determinant for performing repeated calls to the MH1813.

Immigrants relative to natives had significantly increased odds for performing repeated calls, in the crude analysis, as well as the analyses adjusted for age and sex. In the mutually adjusted analysis, the association was borderline significant (OR=1.34; 95% CI 0.96 to 1.85). This result indicates that being an immigrant also is a potential determinant for performing repeated calls to the MH1813 (table 2).

Characteristics associated with calls to MH1813 and with making repeat calls

The crude analysis on characteristics related to the call found that callers’ who were a close relative to the patient were significantly associated with performing a repeated call, whereas the time of call did not have an association with performing a repeated call (table 3).

Table 3.

Crude, adjusted and full model adjusted ORs with 95% CIs for characteristics attach to the call for repeated calls <48 hours (N=464) compared with one-time calls (N=11 131) to the telephone triage

| One-time callers (N=11 131) |

Repeat callers (N=464) |

Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) * | Mutually adjusted OR (95% CI)† | |

| Call time, n (%) | |||||

| Workday | 6777 (60.88) | 275 (59.27) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Weekend | 4354 (39.12) | 189 (40.73) | 1.07 (0.88 to 1.29) | 1.05 (0.87 to 1.27) | 1.09 (0.89 to 1.32) |

| Caller, n (%) | |||||

| Patient | 4481 (40.26) | 210 (45.26) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Close relative | 6650 (59.74) | 254 (54.74) | 0.82 (0.67 to 0.98) | 0.79 (0.64 to 1.00) | 0.75 (0.59 to 0.94) |

*Adjusted for age and sex.

†Adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, income, call time, caller, degree of worry, self-rated health and Charlson comorbidity score.

In the mutually adjusted logistic regression analysis, callers who were close relatives had significantly decreased odds for making repeated calls compared with callers who were patients (OR=0.75; 95% CI 0.59 to 0.94) (table 3).

Discussion

The main finding is that the association between callers’ sociodemographic characteristics (income and ethnicity) and repeated calls to the MH1813 within 48 hours is stronger than for the callers’ health-related characteristics (age, sex, comorbidity, SRH and DOW) (figure 3). Sociodemographic factors have also been shown to be an influence among people with repeated visits to OOH services with face-to-face consultations.20 21 26 33–35 This indicates that the MH1813 reflects similar patterns among people with low income and people who are immigrants, as seen in the OOH services in general.

Specific clinical factors, such as the call handlers’ level of professional experience or language barriers, may also have affected the individual’s need to call more than once. Identification of these factors is beyond the scope of this survey but is a relevant issue to explore in future studies.

The mutually adjusted analysis showed that household income was the only investigated variable that was significantly associated with making repeated calls. Our results indicate that high household income may represent a factor that leads to the occurrence of fewer repeated call within 48 hours of the initial call, whereas low household income may be a determinant for making repeated calls. This finding is supported by evidence showing that low socioeconomic status is related to the extent of comorbidity,36 37 which may increase the need for a professional assessment of the severity of symptoms. Moreover, low socioeconomic status is related to increased use of medical services in general.35 37

In relation to ethnicity, the frequency distribution showed that 7.2% of one-time callers were immigrants, which should be seen in the light of the fact that immigrants make up 10.31% of the general population in Denmark.38 Determining whether fewer immigrants use MH1813, or whether fewer immigrants declined to participate in the survey, is not possible based on the present data. The existing literature, however, indicates that immigrants generally use OOH acute healthcare with face-to-face consultations more frequently than ethnic Danes.21

The mutually adjusted analysis showed that immigrants had insignificantly higher odds of making repeated calls compared with ethnic Danes. One possible reason for this is that immigrants with limited language skills may lack the vocabulary to adequately describe their symptoms on the telephone.39 40 According to Hansen and Hunskaar, who studied adherence to the advice given by a nurse on the telephone, callers’ who were immigrants had a significantly lower level of trust in the nurses and felt that they did not receive relevant answers to questions compared with natives.41

In the frequency distribution between repeated callers’ and one-time callers, sex was not associated with repeated calls. Nevertheless, there were a higher amount of women among one-time callers (54.04%) and repeat callers (55.82%) compared with the distribution of women in the general Danish population (50.25%).38 This distribution is similar to previous studies on OOH services.2 42 43 Women generally contact medical helplines more often than men and usually report a lower SRH than men44 and a higher DOW.23

The distribution of comorbidity in the study population showed that people with the highest strata of comorbidity made repeated calls more frequently (13.58%) than one-time calls (8.79%). This is in line with the existing literature, where people with chronic diseases have a higher rate of repeated inquiries to emergency departments than those without chronic diseases.45–47 One possible explanation is that people with multiple comorbidities have more progressive symptoms, increasing the need for repeated inquiries.8

The self-reported assessment of DOW and SRH was obtained in real time in conjunction with the call to MH1813, diminishing the risk of recall bias. SRH and DOW are simple, self-reported single-item variables that measure subjective, qualitative data using a quantitative method.48 Poor self-evaluated health is a factor that prompts people to seek primary care more frequently.20 26 In the present study, the crude analysis showed that very poor SRH (score=5) was significantly associated with the need to make repeated calls compared with very good SRH (score=1). Likewise, the crude analysis indicated that high DOW was significantly associated with the need to make repeated calls compared with low DOW. The observed association remained significant in the age and sex-adjusted analysis, indicating that SRH and DOW are potential predictors for repeated calls.

When a close relative made the call on behalf of the patient, the risk of a repeated call occurring was significantly reduced. We hypothesise that this result is due to the number of relatives who are parents of small children and request advice and guidance on how to handle a child’s symptoms, reducing the need to call MH1813 again. The two youngest age groups (0–5 and 6–18 years) represented almost 40% of all the calls in this study, which means they are over-represented compared with the general population (22.6%).38 This is in line with similar studies showing that younger people generally have a higher consumption of acute healthcare services.2 15 42 43

Overall, the analysis of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics showed that associations between groups decreased in the adjusted analysis. This suggests that the variables under study had a reinforcing effect and do not independently characterise people who have a need to make repeated calls, indicating that identifying the underlying factors for the need to make repeated calls constitutes a complex issue.

Limitations

In the present study, 33.3% of the study cohort invited to participate agreed to do the survey. In a comparative analysis the participants did not differ significantly from non-responders in relation to age, sex and triage outcome. Nevertheless, selection bias might have been introduced in relation to other sociodemographic or health-related characteristics.

Data on comorbidity were obtained from the Danish National Patient Registry,31 which is why people may have had one or more unrecognised morbidities that had not received an in-hospital diagnosis and subsequent registration in the Danish National Patient Registry. This factor could potentially have led to an information bias in relation to the calculation of comorbidity scores in the present study. However, as this potential information bias would have been present in both people who made one-time calls and people who made repeated calls, it was considered a non-differential misclassification.

In this study, SRH and DOW are measured with a simplified numeric scale. SRH is recognised as a valid predictor of morbidity and mortality.48 DOW, however, is a less studied variable, which is why the validity cannot be accounted for, as is recommended for self-reported measurements.49

Because one of the aims of this study was to be able to implement results in decision making in clinical practice, the sociodemographic and health-related characteristics variables were not tested for interaction. Nevertheless, the existing evidence on the sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of interest suggest multiple interactions between variables, for example, a poor SRH interacts with age and with comorbidities50; a higher DOW interacts with female callers23; and immigrant status interacts with a lower self-perceived health and a higher rate of comorbidities.51 Testing for interaction in the statistical analysis could potentially have provided valuable insight into possible confounders but was considered outside the scope of this study.

Implications for clinicians and policy-makers

This study indicates that specific sociodemographic characteristics of callers are potential determinants of the callers’ need to make repeated calls to a medical helpline with triage function. This implies that the health service needs of callers with certain sociodemographic characteristics may differ compared with other sociodemographic groups when calling a telephone medical helpline.

Recognising the sociodemographic characteristics that play a role is an important aspect of preventing undertriage, which poses a risk of delaying examination and treatment. One way of dealing with this issue is to provide call handlers with additional information about callers’ sociodemographic and self-evaluated characteristics in the existing electronic decision support tool to supplement identification and clinical decision making in telephone triage.

The aim and design of this study provide knowledge on callers’ determinants for performing repeated calls. However, the study does not provide knowledge on potential determinants related to the call handler, nor the interaction between caller and call handler during the initial call, which is relevant to investigate in future studies.

The results of this study are generalisable and can serve to benefit other large-scale OOH telephone triage services.

Conclusions

In the present study, 4% of the calls MH1813 received were from repeat callers. The crude analysis identified sociodemographic and health-related characteristics associated with making repeated calls. The mutually adjusted analysis showed that callers with a mid to high household income had significantly decreased odds for making repeated calls compared with those with very low income. Also, immigrants had insignificantly higher odds for making repeated calls compared with ethnic Danes. Other variables under study had a reinforcing effect on the odds of making repeated calls, which means they did not independently characterise people with a need to make additional calls.

These findings suggest that income and ethnicity are potential determinants for making repeated calls, which indicates that OOH telephone triage might benefit from incorporating sociodemographic characteristics in clinical decision making tools to prevent overtriage or undertriage.

Patient and public involvement

The development of the research aim, design, recruitment, conduct, and outcome measures in this study were not based on patient involvement. Participants can request further information on this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Jens Morten Haugaard, and especially Medical Emergency Services Copenhagen, in acquiring the scientific data and overall guidance.

Footnotes

Contributors: MB, HG-J, ME and TM: conceptualised the study. MB and HG-J: participated in data extraction. MB and MvE-C: participated in data analysis. MB and TM: produced the first draft of the manuscript. HG-J, MvE-C, HCC and TM: provided overall guidance and a final review of all manuscript drafts.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Danish Data Protective Agency (2012-58-0004). Approval from the Scientific Ethics Review Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark was requested but no permission is required (H-15016323).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Huibers L, Giesen P, Wensing M, et al. Out-of-hours care in western countries: assessment of different organizational models. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:105 10.1186/1472-6963-9-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huibers L, Moth G, Carlsen AH, et al. Telephone triage by GPs in out-of-hours primary care in Denmark: a prospective observational study of efficiency and relevance. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:e667–e673. 10.3399/bjgp16X686545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wadmann SKJ. Evaluering af enstrenget og visiteret akutsystem i Region Hovedstaden. Sammenfatning. Det nationale institut for komuners og regioners analyse og forskning 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leprohon J, Patel VL. Decision-making strategies for telephone triage in emergency medical services. Med Decis Making 1995;15:240–53. 10.1177/0272989X9501500307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Purc-Stephenson RJ, Thrasher C. Nurses' experiences with telephone triage and advice: a meta-ethnography. J Adv Nurs 2010;66:482–94. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Greenberg ME. A comprehensive model of the process of telephone nursing. J Adv Nurs 2009;65:2621–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05132.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holmström I, Dall’Alba G. ’Carer and gatekeeper' - conflicting demands in nurses' experiences of telephone advisory services. Scand J Caring Sci 2002;16:142–8. 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2002.00075.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Flarup L, Moth G, Christensen MB, et al. Chronic-disease patients and their use of out-of-hours primary health care: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:114 10.1186/1471-2296-15-114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gamst-Jensen H, Lippert FK, Egerod I. Under-triage in telephone consultation is related to non-normative symptom description and interpersonal communication: a mixed methods study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2017;25:52 10.1186/s13049-017-0390-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bunn F, Byrne G, Kendall S. The effects of telephone consultation and triage on healthcare use and patient satisfaction: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2005;55:956–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Verelst S, Pierloot S, Desruelles D, et al. Short-term unscheduled return visits of adult patients to the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2014;47:131–9. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cheng SY, Wang HT, Lee CW, et al. The characteristics and prognostic predictors of unplanned hospital admission within 72 hours after ED discharge. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:1490–4. 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sabbatini AK, Kocher KE, Basu A, et al. In-Hospital Outcomes and Costs Among Patients Hospitalized During a Return Visit to the Emergency Department. JAMA 2016;315:663–71. 10.1001/jama.2016.0649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Martin-Gill C, Reiser RC. Risk factors for 72-hour admission to the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2004;22:448–53. 10.1016/j.ajem.2004.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huibers LA, Moth G, Bondevik GT, et al. Diagnostic scope in out-of-hours primary care services in eight European countries: an observational study. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:30 10.1186/1471-2296-12-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Byrne M, Murphy AW, Plunkett PK, et al. Frequent attenders to an emergency department: a study of primary health care use, medical profile, and psychosocial characteristics. Ann Emerg Med 2003;41:309–18. 10.1067/mem.2003.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Di Giuseppe G, Abbate R, Albano L, et al. Characteristics of patients returning to emergency departments in Naples, Italy. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:97 10.1186/1472-6963-8-97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCusker J, Healey E, Bellavance F, et al. Predictors of repeat emergency department visits by elders. Acad Emerg Med 1997;4:581–8. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03582.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huber CA, Rosemann T, Zoller M, et al. Out-of-hours demand in primary care: frequency, mode of contact and reasons for encounter in Switzerland. J Eval Clin Pract 2011;17:174–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01418.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vedsted P, Fink P, Sørensen HT, et al. Physical, mental and social factors associated with frequent attendance in Danish general practice. A population-based cross-sectional study. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:813–23. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Norredam M, Krasnik A, Moller Sorensen T, et al. Emergency room utilization in Copenhagen: a comparison of immigrant groups and Danish-born residents. Scand J Public Health 2004;32:53–9. 10.1080/14034940310001659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Helpline Tepratm. 9 Jan 2018 2017.

- 23. Gamst-Jensen H, Huibers L, Pedersen K, et al. Self-rated worry in acute care telephone triage: a mixed-methods study. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:e197–e203. 10.3399/bjgp18X695021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gamst-Jensen H, Frishknecht Christensen E, Lippert F, et al. Impact of caller’s degree-of-worry on triage response in out-of-hours telephone consultations: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2019;27:44 10.1186/s13049-019-0618-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chandola T, Jenkinson C. Validating self-rated health in different ethnic groups. Ethn Health 2000;5:151–9. 10.1080/713667451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vedsted P, Christensen MB. Frequent attenders in general practice care: a literature review with special reference to methodological considerations. Public Health 2005;119:118–37. 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):22–5. 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;29:541–9. 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thygesen L. The register-based system of demographic and social statistics in Denmark. Stat J UN Econ Comm Eur 1995;12:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, et al. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol 2015;7:449–90. 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):30–3. 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tn N. Datavaliditet og dækningsgrad i Landspatientregisteret. Ugeskr Læger 2002;164:33–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maheswaran R, Pearson T, Jiwa M. Repeat attenders at National Health Service walk-in centres - a descriptive study using routine data. Public Health 2009;123:506–10. 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sandvik H, Hunskaar S. Frequent attenders at primary care out-of-hours services: a registry-based observational study in Norway. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:492 10.1186/s12913-018-3310-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vedsted P, Olesen F. Social environment and frequent attendance in Danish general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2005;55:510–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marmot M, Wilkinson RG. Social determinants of health: Oxford university press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marmot MW RG. Social determants of health: Oxford university press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Statistik D. Statistikbanken. Available from: http://wwwstatistikbankendk/statbank5a/defaultasp?w=1920 (cited 7 Apr 2018).

- 39. Wu Z, Penning MJ, Schimmele CM. Immigrant status and unmet health care needs. Can J Public Health 2005;96:369–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Njeru JW, Damodaran S, North F, et al. Telephone triage utilization among patients with limited English proficiency. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:706 10.1186/s12913-017-2651-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hansen EH, Hunskaar S. Understanding of and adherence to advice after telephone counselling by nurse: a survey among callers to a primary emergency out-of-hours service in Norway. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2011;19:48 10.1186/1757-7241-19-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huibers L, Moth G, Andersen M, et al. Consumption in out-of-hours health care: Danes double Dutch? Scand J Prim Health Care 2014;32:44–50. 10.3109/02813432.2014.898974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moth G, Huibers L, Christensen MB, et al. Out-of-hours primary care: a population-based study of the diagnostic scope of telephone contacts. Fam Pract 2016;33:504–9. 10.1093/fampra/cmw048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Christensen ALE, Davidsen O, Juel, K M. Sundhed og sygelighed i Danmark 2010 & udviklingen siden 1987 Statens Institut for Folkesundhed. Syddansk Universitet København 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Flarup L, Carlsen AH, Moth G, et al. The 30-day prognosis of chronic-disease patients after contact with the out-of-hours service in primary healthcare. Scand J Prim Health Care 2014;32:208–16. 10.3109/02813432.2014.984964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. White D, Kaplan L, Eddy L. Characteristics of patients who return to the emergency department within 72 hours in one community hospital. Adv Emerg Nurs J 2011;33:344–53. 10.1097/TME.0b013e31823438d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sauvin G, Freund Y, Saïdi K, et al. Unscheduled return visits to the emergency department: consequences for triage. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:33–9. 10.1111/acem.12052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav 1997;38:21–37. 10.2307/2955359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McKenna SP. Measuring patient-reported outcomes: moving beyond misplaced common sense to hard science. BMC Med 2011;9:86 10.1186/1741-7015-9-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jylhä M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:307–16. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jervelund SS, Malik S, Ahlmark N, et al. Morbidity, self-perceived health and mortality among non-western immigrants and their descendants in denmark in a life phase perspective. J Immigr Minor Health 2017;19:448–76. 10.1007/s10903-016-0347-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.