Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess public acceptance of four possible healthcare policies supporting tobacco dependence treatment in line with the Framework Convention for Tobacco Control, Article 14 recommendations in Germany.

Design

Cross-sectional household survey.

Setting

Data were drawn from the German population and collected through computer-assisted, face-to-face interviews.

Participants

Representative random sample of 2087 people (>14 years) from the German population.

Outcome measures

Public acceptance was measured regarding (1) treatment cost reimbursement, (2) standard training for health professionals on offering cessation treatment, and making cessation treatment a standard part of care for smokers with (3) physical or (4) mental disorders. Association characteristics with smoking status and socio-economic status (SES) were assessed.

Results

Support for all policies was high (50%–68%), even among smokers (48%–66%). Ex-smokers and never-smokers were more likely to support standard training on cessation for health professionals than current smokers (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.92; OR 1.43; 95% CI 1.14 to 1.79, respectively). Ex-smokers were also more likely than current smokers to support cessation treatment for smokers with mental disorders (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.73). Men were less likely than women to support cessation treatment for smokers with physical diseases (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.91) and free provision of treatment (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.97). Offering cessation treatment to smokers with physical disorders was generally more accepted than to those with mental health issues.

Conclusions

The majority of the German population supports healthcare policies to improve the availability and affordability of tobacco dependence treatment. Non-smokers were more supportive than current smokers of two of the four policies, but odds of support were only about 40% higher. SES characteristics were not consistently associated with public acceptance.

Trial registration number

DRKS00011322.

Keywords: healthcare policy, public opinion, smoking cessation, household survey

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study helping fill a knowledge gap on what changes to the tobacco cessation treatment system in Germany the country’s population would agree to.

Data were obtained from a sample which is representative of the German population.

The analysis takes into account socio-demographic and socio-economic factors as well as smoking status of the respondents.

Since the assessed policies are only hypothetical, we are unable to say whether public support would change in the light of actual implementation.

It would also be important to gain insight into the healthcare professionals’ perspective regarding the support towards healthcare policies promoting tobacco cessation in Germany

Introduction

Treating tobacco use is a major public health issue: smoking remains a leading cause of death, killing approximately 6 million people worldwide each year.1 Compared with other Western European countries, for example, the Netherlands (19%), England (17%) or Sweden (7%),2 the prevalence of tobacco smoking in Germany remains high (28%).3 Moreover, smoking is unequally distributed across different groups within the population, with higher rates of smoking in more disadvantaged socio-economic groups3 4 and in people with poor mental health.5 Hence, interventions to reduce tobacco consumption should also aim to decrease tobacco-related health inequalities, and smoking cessation treatment as part of health services should be equally accessible to all social groups.

Article 14 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC)1 states that ratifying countries should take effective measures to promote cessation of tobacco use and provide adequate treatment for tobacco dependence.6 To assist countries in fulfilling these obligations, guidelines for the implementation of Article 14 of the WHO FCTC have been developed,6 proposing the following healthcare policies to reduce national smoking prevalence: integrating brief advice to quit smoking into all healthcare systems, ensuring that all healthcare workers are trained to provide brief smoking cessation support to their smoking patients, using existing health infrastructures for access to tobacco cessation (including primary care) and making evidence-based smoking cessation medication available to all smokers wanting to quit, either freel of charge or at least at an affordable cost.

Whereas other European countries that ratified the FCTC made substantial progress to put these healthcare measures into practice, the level of implementation in Germany is comparably poor.7 Evidence-based treatments are still not, or only partly, reimbursed and stop-smoking services rarely exist. According to national clinical guidelines, evidence-based cessation methods and brief advice to quit tobacco should be routinely offered to smoking patients in medical and psychosocial healthcare settings.8 9 However, general practioners (GPs) lack training in smoking cessation promotion as training is not a standard part of medical education, and to date no specific reimbursement is provided to GPs for offering brief smoking cessation counselling.10

As a consequence, less than 20% of smokers in Germany visiting their GP in the past year report receiving brief smoking cessation counselling,11 which contrasts with England where half of all smokers report having received counselling.12 The majority (>80%) of smokers in Germany still try to quit unaided or with the use of non-evidence-based treatments,3 and thus limit their chances of success.13 Hence, there is an urgent need to improve implementation of Article 14 FCTC in German healthcare.

Implementation of healthcare policies tackling smoking prevalence at population level can only be successful if it is broadly accepted by the public and used by those affected. However, little is currently known about public support for healthcare policies to reduce tobacco-related health effects in Germany. The few existing studies focus exclusively on public attitudes towards tobacco control measures such as increasing taxes, improving public education and environmental restrictions.14–16

Appropriate data are needed to improve the understanding of structural possibilities for the implementation of policies in German healthcare. Implementation usually requires political will, which often relies on understanding the level of public support. The German Study on Tobacco Use (DEBRA), an ongoing national representative survey, provides such data.

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess public support for possible legislative changes on healthcare policies that, according to Article 14 WHO FCTC, should have long been implemented in German healthcare.

Methods

Design, setting and participants

Data on public support for the implementation of potential healthcare policies were collected as part of the nationally representative DEBRA study (‘DEutsche Befragung zum RAuchverhalten’, www.debra-study.info). DEBRA started in June 2016 and consists of cross-sectional, computer-assisted household interviews of people aged 14 years and older, carried out by a market research institute as part of a larger omnibus survey. Over a period of at least 3 years, a new representative sample of approximately 2000 respondents of the German population will complete the survey every 2 months. Beyond smoking status, smoking and quitting behaviour, use of cessation methods and of electronic cigarettes, respondents report on socio-demographic characteristics. Methodological details, including details of the sampling approach, as well as the complete DEBRA questionnaire have been published in the study protocol.17 The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Questions on public support for specific policies were asked during wave 2 of the study in August/September 2016, in a total sample of 2087 respondents. For this wave, questions on public acceptance of (a) tobacco control strategies and (b) healthcare policy were included. Findings on legislative tobacco control strategies such as a total ban of tobacco products or raising the legal age for tobacco consumption have been published elsewhere.18 This article discusses the findings on public attitudes towards healthcare policies suggested in Article 14 of the WHO FCTC.

Measures

Socio-demographic and smoking characteristics

Socio-demographic data on age, sex, education and net household income from all respondents are routinely collected in the omnibus survey by the market research institute. In the current analysis, the level of education of every respondent was categorised from highest to lowest as 5=high school equivalent (‘Allgemeine Hochschulreife’), 4=advanced technical college equivalent (‘Fachhochschulreife’), 3=secondary school equivalent (‘Realschulabschluss’), 2=junior high school equivalent (‘Hauptschulabschluss’) and as 1=no qualification. Respondents provided a point estimate of their net household income, which was categorised into 6=more than 5000€/month, 5=4000 to less than 5000€/month, 3=2000 to less than 3000€/month, 4=3000 to less than 4000€/month, 2=1000 to less than 2000€/month and 1=less than 1000€/month. Respondents were categorised as current tobacco smokers (cigarettes or other combustible tobacco products), as ex-smokers if they had stopped during the past year or more than a year ago, or as never smokers if they had never smoked for a year or longer.

Current smokers of tobacco products were asked further details on their smoking behaviour: number of cigarettes smoked per day (per week or per month data were converted for analyses), about their current motivation to quit smoking using the translated and culturally adapted German version of the Motivation to Stop Smoking Scale,19 and whether or not they made at least one quit attempt during the past year.

Measuring public support for healthcare policies

Public support was assessed for four suggestions on potential healthcare policies related to tobacco cessation. These suggestions have been adapted from the Smoking Toolkit Study,20 a methodologically comparable household survey, allowing comparisons with data from England at a later stage.

Participants were asked whether they would (a) ‘strongly support’, (b) ‘tend to support’, (c) ‘have no opinion either way’, (d) ‘tend to oppose’, (e) ‘strongly oppose’, or (f) ‘don’t want to answer’ the four statements listed below. Answers are classified into ‘agree’ (a and b), ‘disagree’ (d and e), ‘undecided’ (c) and ‘no answer’ (f), and further dichotomised for regression analyses into ‘agree’ (a and b) and ‘don’t agree’ (c, d and e), with those responding ‘f’ excluded.

‘Every smoker who wants should get support that is clinically proven to help stop smoking, and costs for these treatments (pharmacological or behavioural smoking cessation therapy) should be reimbursed’.

‘Making sure that all healthcare professionals directly involved in the treatment or care of patients are trained to advise smokers on how to stop smoking’.

‘Making stop-smoking support a standard part of care for smokers with long-term physical health problems (such as cardiovascular or respiratory diseases)’.

‘Making stop-smoking support a standard part of care for smokers with mental health problems (such as depression or schizophrenia)’.

Statements were asked in a random order to avoid primacy and recency effects.21

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses using unweighted data were carried out to characterise the total sample, as well as the subsamples, according to the smoking status of respondents. For categorical variables, proportions were computed and for continuous variables, data were presented in terms of means and SD.

To provide prevalence data on public support for potential healthcare policies, the sample was weighted to be representative of the German population. Details on weighting procedures have been published in the study protocol.17

Associations between support for suggested healthcare policies and sample characteristics were assessed with exploratory multivariable logistic regression analyses using unweighted data (dichotomous dependent variable ‘agree on a potential healthcare policy’ (agree vs disagree)). A second multivariable model was run with the subsample of current smokers, assessing associations between support for suggested healthcare policies and smoking characteristics. Sample characteristics included in both models were sex, age, net household income, education and smoking status. For the subgroup analysis in current smokers, the following smoking characteristics were also included: number of cigarettes smoked per day, current motivation to stop smoking18 and attempts to quit smoking (any vs none) during the past year. To assess whether the subsample of smokers differed from the subsample of never-smokers and ex-smokers, we ran a third regression model for the latter group separately (online supplementary table 1).

bmjopen-2018-026245supp001.pdf (72.2KB, pdf)

Of the total sample, 25 respondents (1.1% of the total sample) refused to disclose their smoking status and were thus excluded from all analyses. Respondents who refused to answer questions on either their educational level, their attempts to quit smoking, or on questions regarding their support for potential healthcare policies were only excluded from the multivariate logistic regression analyses (statement 1=177 missing (8.6%), statement 2=187 missing (9.1%), statement 3=179 missing (8.7%) and statement 4=245 missing (11.9%)).

Results

Sample characteristics

Unweighted baseline characteristics of the analysed sample of 2062 respondents with full data on their smoking status are presented in table 1. The sample had a mean age of 51.8 years (SD=±20 years) and 1070 (51.9%) respondents were women. In total, 1107 (53.7%, 95% CI=51%–55%) respondents were never-smokers, 369 (17.9%, 95% CI=16%–19%) were ex-smokers and 586 (28.4%, 95% CI=26%–30%; unweighted) were current smokers. Table 2 presents data on smoking characteristics for this subsample of current smokers.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the total sample and by smoking status (unweighted data)*

| Total sample (n=2062; 100%) |

Current smoker (n=586; 28.4%) |

Ex-smoker (n=369; 17.9%) |

Never-smoker (n=1107; 53.7%) |

|

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 51.8±19.8 | 47.1±17.2 | 58.4±17.5 | 52.1±21.1 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1070 (51.9%) | 271 (46.2%) | 143 (38.8%) | 656 (59.3%) |

| Male | 992 (48.1%) | 315 (53.8%) | 226 (61.2%) | 451 (40.7%) |

| Education† | ||||

| High school equiv. | 479 (23.2%) | 110 (19.2%) | 85 (23.2%) | 284 (27.4%) |

| Adv. tech. college equiv. | 133 (6.5%) | 28 (4.9%) | 30 (8.2%) | 75 (7.2%) |

| Secondary school equiv. | 686 (33.3%) | 230 (40.1%) | 116 (31.7%) | 340 (32.8%) |

| Junior high school equiv. | 646 (31.3%) | 193 (33.6%) | 130 (35.5%) | 323 (31.1%) |

| No qualification | 33 (1.6%) | 13 (2.3%) | 5 (1.4%) | 15 (1.4.5%) |

| Household income | ||||

| >€5000/per month | 134 (6.5%) | 26 (4.4%) | 27 (7.3%) | 81 (7.3%) |

| €4000–5000/per month | 128 (6.2%) | 31 (5.3%) | 24 (6.5%) | 73 (6.6%) |

| €3000–4000/per month | 369 (17.9%) | 96 (16.4%) | 67 (18.2%) | 206 (18.6%) |

| €2000–3000/per month | 557 (27.0%) | 164 (28.0%) | 106 (28.7%) | 287 (25.9%) |

| €1000–2000/per month | 638 (30.9%) | 173 (29.5%) | 117 (31.7%) | 348 (31.4%) |

| < €1,000/per month | 236 (11.4%) | 96 (16.4%) | 28 (7.6%) | 112 (10.1%) |

*Baseline characteristics of the sample have also been published elsewhere18 under the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited: CC BY 4.0. Data are presented as number (% within row), unless otherwise stated.

†German equivalents to education levels listed in table from highest to lowest: high school equivalent = “Allgemeine Hochschulreife,” advanced technical college equivalent = “Fachhochschulreife,” secondary school equivalent = “Realschulabschluss,” junior high school equivalent = “Hauptschulabschluss”.

Table 2.

Smoking characteristics of current smokers (unweighted data)

| Current smokers only (n=586) |

|

| Cigarettes smoked per day (mean+SD) | 15.3±9.0 |

| Made at least one quit attempt last year | 140 (23.9%) |

| Motivation to stop smoking17 | |

| Don't want to stop smoking | 268 (45.7%) |

| Should stop but don't really want to | 139 (23.7%) |

| Want to stop but haven't thought about when | 52 (8.9%) |

| Want to stop but haven’t decided when | 51 (8.7%) |

| Really want to stop and hope to soon | 43 (7.3%) |

| Really want to stop and intend to in the next 3 months | 7 (1.2%) |

| Really want to stop and intend to in the next month | 6 (1.0 %) |

Data are presented as number (%), unless otherwise stated.

Public support for healthcare policies

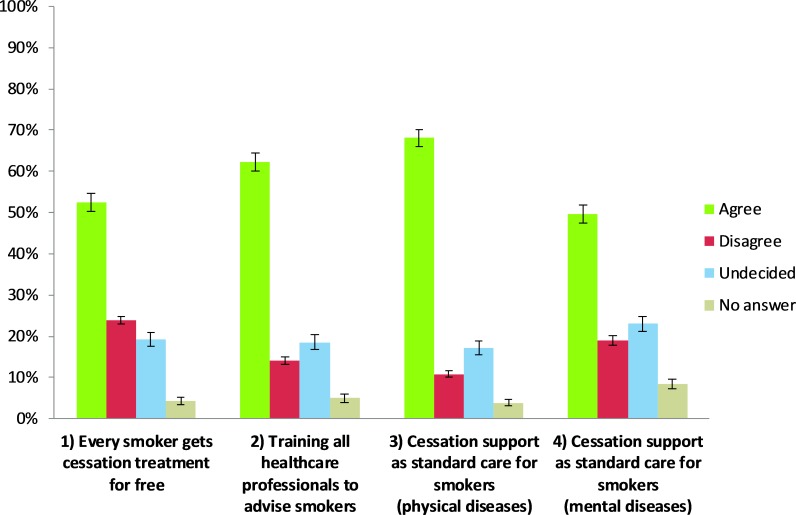

Figure 1 presents rates of support for suggested healthcare policies weighted to be representative for the German population. All four policies receive support from the majority of the population. Of the total sample, 52% (95% CI=50%-55%) agreed to providing cessation treatment to every smoker for free, 62% (95% CI=60%-64%) would support standard training on cessation for health professionals, 68% (95% CI=66%-70%) would support cessation as standard care for patients with chronic physical diseases, and half of the sample (50%, 95%CI=47%–51%) supports cessation for patients with mental disorders.

Figure 1.

Proportion (with 95% CI) of public support for healthcare policies (n=2062 respondents, weighted data).

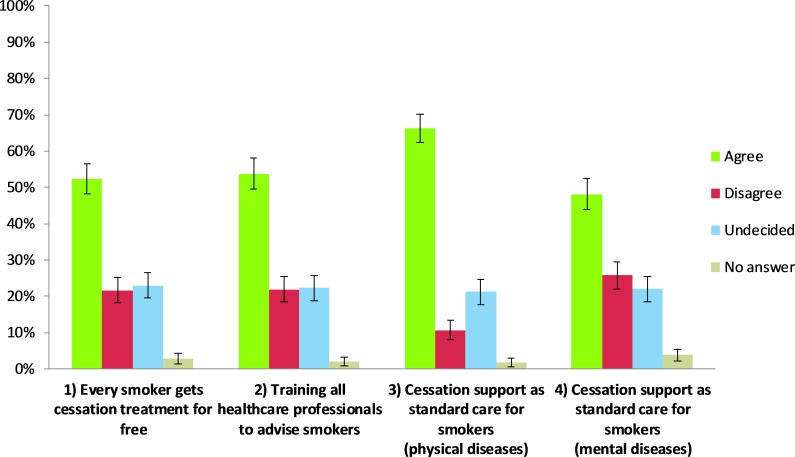

Among the subsample of current smokers (figure 2), the majority also agreed with all four healthcare policies, with standard cessation provision for patients with physical comorbidities, again ranking highest at 66% (95% CI=62%-70%). Slightly fewer smokers (54%, 95% CI=50%–58%) than in the total sample would support standard training for all health professionals.

Figure 2.

Proportion (with 95% CI) of support for healthcare policies in the subsample of current smokers (n=586 respondents, weighted data).

Factors associated with public support

Table 3 presents the results of the multivariable logistic regression for the suggested healthcare policies for the total unweighted sample and for the subgroup of current smokers (for the sake of completeness we ran the regression model again for the group of never-smokers and ex-smokers, please see online supplementary table 1). Overall, socio-demographic and smoking characteristics are not consistently associated with support for proposed healthcare policies, with the exception of sex and smoking status.

Table 3.

Multivariable associations with support for the proposed healthcare policies in the total sample (n=2062), and in current smokers (n=586)

| 1)Every smoker gets cessation treatment for free | 2)Training all healthcare professionals to advise smokers | 3)Cessation support as standard care for smokers (physical diseases) | 4)Cessation support as standard care for smokers (mental illness) | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current smoker (ref.) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ex-smoker | 0.88 (0.67–1.16) | 1.43 (1.07–1.92)* | 1.37 (1.00–1.88) | 1.19 (0.89–1.58) |

| Never-smoker | 0.88 (0.71–1.09) | 1.43 (1.14–1.79)** | 1.05 (0.83–1.33) | 1.39 (1.11–1.73)** |

| Age, 10 year units† | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) | 1.05 (1.00–1.11) | 1.06 (1.00–1.13)* | 1.05 (1.00–1.11) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female (ref.) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 0.80 (0.66–0.97)* | 0.83 (0.68–1.01) | 0.74 (0.60–0.91)** | 0.91 (0.75–1.10) |

| Education‡ | ||||

| High school equiv. (ref.) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Adv. tech. college equiv. | 1.50 (1.00–2.24)* | 1.16 (0.76–1.77) | 1.21 (0.77–1.92) | 1.41 (0.93–2.13) |

| Secondary school equiv. | 1.34 (1.05–1.72)* | 1.15 (0.88–1.49) | 1.02 (0.77–1.34) | 1.06 (0.82–1.37) |

| Junior high school equiv. | 1.36 (1.03–1.79)* | 0.99 (0.75–1.32) | 0.93 (0.69–1.26) | 1.23 (0.93–1.63) |

| No qualification | 1.07 (0.49–2.34) | 1.68 (0.69–4.11) | 1.19 (0.49–2.91) | 0.86 (0.39–1.91) |

| Household income | ||||

| €>5000/per month (ref.) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| €4000–5000/per month | 0.99 (0.60–1.64) | 0.70 (0.42–1.19) | 1.23 (0.69–2.19) | 1.32 (0.79–2.21) |

| €3000–4000/per month | 1.04 (0.69–1.58) | 0.88 (0.56–1.36) | 1.03 (0.65–1.165) | 1.59 (1.04–2.43)* |

| €2000–3000/per month | 0.92 (0.62–1.38) | 0.87 (0.57–1.33) | 0.84 (0.54–1.32) | 1.39 (0.92–2.10) |

| €1000–2000/per month | 1.02 (0.68–1.53) | 0.91 (0.59–1.40) | 1.05 (0.67–1.64) | 1.56 (1.03–2.37)* |

| < €1,000/per month | 1.53 (0.97–2.43) | 1.10 (0.67–1.78) | 1.22 (0.73–2.04) | 2.07 (1.29–3.31)** |

| Current smokers only (n=586) | ||||

| Cigarettes smoked/day, number | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) |

| Quit attempt last year (yes/no) | ||||

| Yes, attempt to quit (ref.) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No, attempt to quit | 0.80 (0.51–1.26) | 0.70 (0.44–1.11) | 0.91 (0.56–1.48) | 0.84 (0.54–1.32) |

| Motivation to stop smoking (MRS)3§ | 1.00 (0.87–1.14) | 1.20 (1.04–1.40)* | 1.14 (0.98–1.33) | 0.95 (0.83–1.08) |

Data are presented as adjusted OR (95% CI around OR). *p<0.05; **p<0.01.

†Continuous variable: age units are based on DEBRA study participation eligibility (14 years and older): 14–23; 24–33; 34–43; 44–53; 54–63; 64–73; 74–83; 84–93; 94–103.

‡German equivalents to education levels listed in table from highest to lowest: high school equivalent = “Allgemeine Hochschulreife,” advanced technical college equivalent = “Fachhochschulreife,” secondary school equivalent = “Realschulabschluss,” junior high school equivalent = “Hauptschulabschluss”.

§Continuous variable (MRS: increasing from 1 “don’t want to top” to 7 “really want to stop, intend to in the next month”).

Ref., reference group.

Men had lower odds of agreeing with (1) free provision of cessation treatment (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.97) than women. Household income showed no significant associations with support for the policy, while those with education levels of junior high school equivalent to advanced technical college equivalent had higher odds of supporting free provision (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.79; OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.72, OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.00 to 2.24, respectively).

Standard ( 2) training of health professionals in cessation had higher odds of being supported by ex-smokers or never-smokers (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.92 and OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.79, respectively) than current smokers.

Men were less likely than women to support ( 3) cessation as standard care for patients with physical diseases (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.91).

Regarding ( 4) cessation as standard care for patients with mental illness, ex-smokers had significantly higher odds than current smokers to agree with this healthcare policy (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.73). Those earning less than 1000€/month had higher odds of supporting this statement than the highest income group (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.29 to 3.31).

Support for policies in the subsample of smokers

When adjusting for socio-demographic characteristics (age, sex, education, household income) in the group of current smokers (table 3), motivation to quit smoking was associated with support for the proposed statement that all health professionals should be trained in offering cessation support: the higher the motivation to quit, the greater the odds that a respondent agreed with the statement (continuous variable, OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.40). No further associations between level of support and smoking characteristics could be found among current smokers.

Discussion

Overall, support in Germany is high for four healthcare policies that would increase the availability and affordability of tobacco cessation treatment: a majority of the adult population supports each of the four policies. Smoking status was associated with support for two of the four policies, but the odds of agreement were only up to 40% greater among non-smokers than current smokers. These findings are in line with results from 89 surveys on smokefree policy in the USA and Canada22; however, a study from China found equal support for policies among smokers and non-smokers.23 Men were less supportive than women, which was also observed in the review from the USA and Canada,22 but most socio-economic status (SES) characteristics were not consistently associated with public acceptance.

Acceptance of standard cessation support for patients with chronic physical diseases is higher than of cessation provision for patients with mental health issues. Compared with the highest income group, people in the lower income groups expressed higher support for standard cessation treatment for the patient group with mental health comorbidities. Prevalence of smoking24 25 and of mental health issues26 is higher in lower SES groups in Germany, similar to other European countries,27 which could potentially explain these findings. Inequalities also persist for seeking treatment for psychiatric disorders in Germany.28 Another possible explanation is misconception relating to smoking and mental health. A recent systematic review found that even among mental health professionals, smoking is often perceived as a tool to manage stress in patients, and some mental health professionals believe that quitting smoking may be too much for their patients to take on while on treatment.29

A related interesting finding is that the number of people not answering whether they support standard treatment for patients with mental health comorbidities was higher than for other questions. This raises concerns about potential stigmatisation of psychiatric illnesses or lack of knowledge about mental health in the general population in Germany. At the same time, this healthcare policy, in particular, would be of high importance, as patients with mental health issues are more susceptible to tobacco use5 and could especially profit from standard provision of cessation support.30 It could be argued that more information about mental health might need to be provided to the public. Integrating information on study participants' mental health conditions and treatment into future or ongoing population surveys could further support research on cessation for these groups.

We found sex differences influencing support for two statements: support for free cessation treatment among current smokers and support for standard treatment for patients with physical disorders among the whole sample. In each case, men had lower odds of supporting the said healthcare policies. Whether disease concepts, including concepts of addiction,31 play a role in these differences needs to be explored further, ideally using both survey data and in-depth qualitative research.

Respondents who indicated a high motivation to quit seem to be more supportive of training healthcare professionals to advise smokers on how to quit tobacco. In the light of the fact that the majority of quit attempts in Germany occur unaided,3 this result highlights the need for the integration of such training into health professional education in Germany.

Compared with other European countries, tobacco cessation treatment is not well integrated into healthcare in Germany, despite knowledge about the burden of the disease caused by tobacco use. The Germany SimSmoke study estimated that over 140 000 lives could be saved between 2020 and 2040 if cessation treatment were provided for free and comprehensively,32 indicating a potential for better public health in Germany were such policies to be implemented.

This study has some limitations. We were only able to pose the healthcare policy support questions in one wave of the DEBRA survey due to resource constraints. It would be interesting to repeat the assessment in the future to gain insights into temporal trends and sensitivity of public acceptance in the light of actual healthcare policy changes.

As the proposed healthcare policies would directly affect healthcare professionals in their training and work, it would be useful to assess not only public support, but also healthcare professionals’ support towards these measures. However, as DEBRA is a nationally representative sample, the findings give good insights into the overall population and research with a sample of healthcare professionals could complement our national study.

The policies assessed here are only hypothetical. We are therefore unable to say whether public support would change in the light of actual implementation. In addition, respondents were not asked about who would pay for free cessation treatment. Other studies have found that the public is willing to pay for effective tobacco control;33 however, this willingness to spend has its limits.

Our findings help fill a knowledge gap on what changes to the tobacco cessation treatment system in Germany the country’s population would agree to. Few studies have assessed public support for cessation treatment measures instead of tobacco control policies such as taxation or smokefree legislation. Information on public acceptance of specific tobacco treatment measures is even scarcer in Germany than for tobacco control. In Germany, DEBRA is one of only a few representative surveys targeting smoking and tobacco use behaviour,34 and is the only one providing both cross-sectional and longitudinal data on specific tobacco-related questions at 2-month intervals.17

Making cessation treatment a part of standard care for patients with physical and mental health disorders is a practice that has already been successful elsewhere,35 and would be in line with the German clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of tobacco addiction.8 9 As such, these proposed healthcare policies are within the realm of the possible. Our findings show that offering cessation treatment as standard care in Germany would be accepted by the public.

Conclusions

Public support for integrating tobacco cessation treatment into the health system is high in Germany, in both smokers and never-smokers and ex-smokers. Never-smokers were more supportive than current smokers, but it is encouraging that the difference regarding the level of support between these two groups is small. Socio-demographic characteristics were not consistently associated with public acceptance. Offering tobacco cessation treatment to patients with physical diseases was generally more accepted than for patients with mental disorders. Providing cessation treatment offers to all smoking patients or, as a bare minimum, to those presenting with chronic disorders could be an accepted way forward in German tobacco control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank: Professor Robert West for support with the DEBRA study design; Kantar Health (Constanze Cholmakow-Bodechtel and Linda Scharf) for data collection; and Yekaterina Pashutina for her support with table entries.

Footnotes

Contributors: SK coordinates the DEBRA study, drafted the manuscript and analysed and interpreted the data. MB co-wrote the manuscript and interpreted the data. DK conceived the DEBRA study, contributed to the study design for the policy question analysis and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. LS and JB work for the English Smoking Toolkit Study with which DEBRA is closely aligned, and contributed to the study design as well as to the writing of the manuscript. All named authors contributed substantially to the manuscript and agreed on its final version.

Funding: This work was supported by the Ministry for Culture and Science of the German Federal State of North Rhine-Westphalia ("NRW-Rückkehrprogramm"). It had no involvement in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, interpretation of data or in the writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: SK and MB have no conflict of interest to declare. JB has received unrestricted research funding from Pfizer who manufacture smoking cessation medications. LS has received honoraria for talks, an unrestricted research grant and travel expenses to attend meetings and workshops from Pfizer, and has acted as a paid reviewer for grant-awarding bodies and as a paid consultant for healthcare companies. DK received an unrestricted grant from Pfizer in 2009 for an investigator-initiated trial on the effectiveness of practice nurse counselling and varenicline for smoking cessation in primary care (Dutch Trial Register NTR3067). All authors declare no financial links with tobacco companies or e-cigarette manufacturers or their representatives.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the Heinrich-Heine-University Dusseldorf (ID 5386/R).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. WHO WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic. Warning about the dangers of tobacco 2011. Available: http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/ [Accessed 25 Jun 2018].

- 2. European Commission Special Eurobarometer 458. Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes, 2017. Available: https://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/dataset/S2146_87_1_458_ENG [Accessed 15 Apr 2019].

- 3. Kotz D, Böckmann M, Kastaun S. The use of tobacco, e-cigarettes, and methods to quit smoking in Germany. A representative study using 6 waves of data over 12 months (the DEBRA study). Dtsch Arztebl Int 2018;115:235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kuntz B, Zeiher J, Hoebel J, et al. Social inequalities, Smoking and Health [Soziale Ungleichheit, Rauchen und Gesundheit]. Suchttherapie 2016;17:115–23. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Royal College of Physicians, Royal College of Psychiatrists Smoking and mental health. Royal College of psychiatrists Council report CR178, 2013. Available: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/smoking-and-mental-health [Accessed 14 Apr 2019].

- 6. WHO Framework convention on tobacco control (FCTC) article 14 guidelines, 2010. Available: http://www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/adopted/article_14/en/ [Accessed 25 Mar 2019].

- 7. The Tobacco Control Scale 2016 in Europe A report of the association of the European cancer Leagues, 2016. Available: https://www.tobaccocontrolscale.org/ [Accessed 15 Apr 2019].

- 8. AWMF Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) S3 Guideline “Screening, Diagnostics, and Treatment of Harmful and Addictive Tobacco Use” [S3-Leitlinie “Screening, Diagnostik und Behandlung des schädlichen und abhängigen Tabakkonsums”]. AWMF-Register Nr. 076-006, 2015. Available: http://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/076-006.html [Accessed 15 Apr 2019].

- 9. Andreas S, Batra A, Behr J, et al. Smoking cessation in patients with COPD. [Tabakentwöhnung bei COPD S3-Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin e.V.]. Pneumologie 2014;68:237–58.24570269 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Twardella D, Brenner H. Lack of training as a central barrier to the promotion of smoking cessation: a survey among general practitioners in Germany. Eur J Public Health 2005;15:140–5. 10.1093/eurpub/cki123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kastaun S, Kotz D. Brief physician advice for smoking cssation: Results of the DEBRA study [Ärztliche Kurzberatung zur Tabakentwöhnung – Ergebnisse der DEBRA Studie], 2019. Available: https://econtent.hogrefe.com/doi/abs/10.1024/0939-5911/a000574

- 12. Brown J, West R, Angus C, et al. Comparison of brief interventions in primary care on smoking and excessive alcohol consumption: a population survey in England. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:e1–9. 10.3399/bjgp16X683149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction 2004;99:29–38. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schumann A, John U, Thyrian JR, et al. Attitudes towards smoking policies and tobacco control measures in relation to smoking status and smoking behaviour. Eur J Public Health 2006;16:513–9. 10.1093/eurpub/ckl048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Keller S, Weimer-Hablitzel B, Kaluza G, et al. Attitudes towards smoking policy and smoking status [Einstellungen zur Raucherpolitik in Abhängigkeit vom aktuellen Raucherstatus]. Z Med Psychol 2002;11:177–84. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schaller K, Braun S, Pötschke-Langer M. Success story protection from second-hand smoke exposure in Germany: Increased public support for legislative measures [Erfolgsgeschichte Nichtraucherschutz in Deutschland: Steigende Unterstützung in der Bevölkerung für gesetzliche Maßnahmen]. Gesundheitsmonitor Newsl 2014:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kastaun S, Brown J, Brose LS, et al. Study protocol of the German study on tobacco use (DEBRA): a national household survey of smoking behaviour and cessation. BMC Public Health 2017;17:378 10.1186/s12889-017-4328-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boeckmann M, Kotz D, Shahab L, et al. German public support for tobacco control policy measures: results from the German study on tobacco use (DEBRA), a representative national survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:696 10.3390/ijerph15040696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kotz D, Brown J, West R. Predictive validity of the motivation to stop scale (MTSS): a single-item measure of motivation to stop smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;128:15–19. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fidler JA, Shahab L, West O, et al. 'The smoking toolkit study': a national study of smoking and smoking cessation in England. BMC Public Health 2011;11:479 10.1186/1471-2458-11-479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bowling A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J Public Health 2005;27:281–91. 10.1093/pubmed/fdi031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thomson G, Wilson N, Collins D, et al. Attitudes to smoke-free outdoor regulations in the USA and Canada: a review of 89 surveys. Tob Control 2016;25:506–16. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li Q, Hyland A, O'Connor R, et al. Support for smoke-free policies among smokers and non-smokers in six cities in China: ITC China survey. Tob Control 2010;19 Suppl 2:i40–6. 10.1136/tc.2009.029850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hoebel J, Kuntz B, Kroll LE, et al. Trends in absolute and relative educational inequalities in adult smoking since the early 2000s: the case of Germany. Nicotine Tob Res 2018;20:295–302. 10.1093/ntr/ntx087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lampert T, von der Lippe E, Müters S. Prevalence of smoking in the adult population of Germany [Verbreitung des Rauchens in der Erwachsenenbevölkerung in Deutschland]. Bundesgesundhbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz 2013;56:802–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pinto-Meza A, Moneta MV, Alonso J, et al. Social inequalities in mental health: results from the EU contribution to the world mental health surveys initiative. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013;48:173–81. 10.1007/s00127-012-0536-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam A-JR, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2468–81. 10.1056/NEJMsa0707519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Epping J, Muschik D, Geyer S. Social inequalities in the utilization of outpatient psychotherapy: analyses of registry data from German statutory health insurance. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:147 10.1186/s12939-017-0644-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sheals K, Tombor I, McNeill A, et al. A mixed-method systematic review and meta-analysis of mental health professionals' attitudes toward smoking and smoking cessation among people with mental illnesses. Addiction 2016;111:1536–53. 10.1111/add.13387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, et al. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2014;348:g1151 10.1136/bmj.g1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Racine E, Sattler S, Escande A. Free will and the brain disease model of addiction: the not so Seductive Allure of neuroscience and its modest impact on the Attribution of free will to people with an addiction. Front Psychol 2017;8:1850 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Levy DT, Blackman K, Currie LM, et al. Germany SimSmoke: the effect of tobacco control policies on future smoking prevalence and smoking-attributable deaths in Germany. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:465–73. 10.1093/ntr/nts158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sanders AE, Slade GD, Ranney LM, et al. Valuation of tobacco control policies by the public in North Carolina: comparing perceived benefit with projected cost of implementation. N C Med J 2012;73:439–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Piontek D, Kraus L, EGd M. Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse 2015 [Der Epidemiologische Suchtsurvey 2015] SUCHT; 2016: 259–69. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Szatkowski L, Aveyard P. Provision of smoking cessation support in UK primary care: impact of the 2012 QOF revision. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:e10–15. 10.3399/bjgp15X688117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026245supp001.pdf (72.2KB, pdf)