Abstract

Objectives

Violence towards emergency department healthcare workers is pervasive and directly linked to provider wellness, productivity and job satisfaction. This qualitative study aimed to identify the cognitive and behavioural processes impacted by workplace violence to further understand why workplace violence has a variable impact on individual healthcare workers.

Design

Qualitative interview study using a phenomenological approach to initial content analysis and secondary thematic analysis.

Setting

Three different emergency departments.

Participants

We recruited 23 emergency department healthcare workers who experienced a workplace violence event to participate in an interview conducted within 24 hours of the event. Participants included nurses (n=9; 39%), medical assistants (n=5; 22%), security guards (n=5; 22%), attending physicians (n=2; 9%), advanced practitioners (n=1; 4%) and social workers (n=1; 4%).

Results

Five themes emerged from the data. The first two supported existing reports that workplace violence in healthcare is pervasive and contributes to burn-out in healthcare. Three novel themes emerged from the data related to the objectives of this study: (1) variability in primary cognitive appraisals of workplace violence, (2) variability in secondary cognitive appraisals of workplace violence and (3) reported use of both avoidant and approach coping mechanisms.

Conclusion

Healthcare workers identified workplace violence as pervasive. Variability in reported cognitive appraisal and coping strategies may partially explain why workplace violence negatively impacts some healthcare workers more than others. These cognitive and behavioural processes could serve as targets for decreasing the negative effect of workplace violence, thereby improving healthcare worker well-being. Further research is needed to develop interventions that mitigate the negative impact of workplace violence.

Keywords: qualitative research, burnout, accident & emergency medicine, wellness

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Prospective study of healthcare workplace violence across multiple different healthcare professionals.

Addresses a limitation of current literature by collecting data immediately following workplace violence events, thus limiting recall bias.

Identifies possible targets to ameliorate the negative impact of workplace violence on healthcare workers.

Proposes a conceptual model of healthcare workplace violence and burn-out.

Sample was limited to a purposive sample of 23 healthcare workers practising within a single US city.

Introduction

Healthcare worker (HCW) safety and well-being are cornerstones of safe, effective patient care.1 The link between patient care and HCW safety is now recognised by patient safety experts, with recent reports suggesting that the ‘Triple Aim’ of high-value healthcare include a fourth Aim reflecting the need to support HCW well-being.2 Workplace violence (WPV) in healthcare is linked to HCW burn-out.3 4 While the prevalence of WPV is most commonly described in North America and the UK, recent studies report similar violence rates and characteristics in other parts of Europe, Asia, Africa and Australia.5–10 Despite efforts to address WPV and HCW burn-out and well-being, violence against HCWs remains a pervasive, recognised threat to patient safety.2

The emergency department (ED) setting has been specifically recognised as an area of high risk for WPV. Violence in the ED impacts more than 1 million individuals with over 78% of ED HCWs identifying at least one incident of physical assault by a patient or patient’s visitor during their career.11 According to a 2006 study, 67% of nurses, 63% of medical assistants and 51% of physicians had been assaulted by an ED patient at least once in the prior 6-month period.12 Patient factors (eg, psychiatric comorbidities, cognitive impairment) and institutional/environmental factors (eg, high censuses, long waiting room times) make EDs particularly susceptible to WPV.13–15

Most published research and quality improvement programmes have focused on interventions to decrease the incidence of WPV.16–19 Despite these efforts, a recent report by the American College of Emergency Physicians notes that over a 1-year period, greater than 60% of physicians report being assaulted.20 Since some amount of ED WPV seems inevitable regardless of training or security measures,15 21 22 it is important to also focus on mitigating the negative impact of WPV on HCWs.23 Surveys conducted in several countries suggest a connection between WPV and burn-out,3 4 yet do not offer an understanding of the processes that lead to burn-out, nor do they explain why some HCWs are less affected than others. Specifically, there is a paucity of work focused on identifying the cognitive and behavioural processes that could assist HCWs in recovering from WPV events.

We conducted a prospective qualitative study to understand (1) how ED HCWs appraise WPV events, (2) what coping mechanisms ED HCWs use in response to WPV and (3) the relationship between WPV and burn-out. This work supports our overall goal of mitigating the negative impact of acute and chronic exposure to WPV.

Methods

Study design and setting

We executed a qualitative study with semistructured interviews of ED HCWs and analysed transcripts using a phenomenological approach. One-on-one interviews involved ED HCWs from three EDs representing urban, academic and community hospitals within the State of Washington (table 1). We conducted all interviews within 24 hours of a WPV event.

Table 1.

Hospital characteristics of enrolling sites

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 3 | |

| Setting | Urban, academic safety net hospital | Tertiary referral centre | Community |

| Inpatient beds (n) | 413 | 450 | 303 |

| ED beds (n) | 48 | 23 | 55 |

| ED visits per year (n) | 63 000 | 29 000 | 82 000 |

| Admitted patients (% total) | 21 | 24 | 14 |

| Average length of stay (h) | 4.5 | 4.9 | 3.0 |

ED, emergency department

Participants and sampling

Participants were ED HCWs selected through purposive sampling. A trained research coordinator present in the ED weekdays from 14:00 until 22:00 identified employees who experienced verbal or physical aggression as defined by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (table 2).24 Following an observed WPV event, the research coordinator approached the employees involved. Employees were considered eligible if they were available for an interview within the following 24 hours. All participants provided consent for both participation and audio recording. The research coordinator collected demographic information from each consented participant. At two sites, participants were compensated with a US$10 gift card. The third site required voluntary participation based on institutional bylaws.

Table 2.

Definitions relevant to the analysis

| Construct | Definition and significance |

| Occupational Safety and Health Administration definition of WPV | “Workplace violence is any act or threat of physical violence, harassment, intimidation, or other threatening disruptive behavior that occurs at the work site. It ranges from threats and verbal abuse to physical assaults and even homicide”.57 |

| Cognitive appraisal | The process of an individual evaluating the personal significance or relevance of a stressful event and its related components to his/her well-being.32 Cognitive appraisals then drive the individual’s selection of coping mechanism and partially mediate stressor impact and work-related outcomes.37 58 |

| Primary cognitive appraisal | Process of an individual evaluating whether s/he has anything at stake during a stressful encounter; that is, harm to physical self, loss of self-esteem, ability to learn or improve, etc.32 Primary appraisals can be categorised as harmful, threatening or challenging. |

| Secondary cognitive appraisal | Process of evaluating the ability to respond to the situation; that is, having the necessary resources or skills to deal with the stressful event.33 This relates to the individual’s assessment that they can (1) directly address the stressor and (2) cope with the event.32 |

| Coping | Conscious use of cognitive and/or behavioural strategies that is intended to decrease perceived stress or increase resources available to deal with stress. Can be further delineated into those efforts directed at processing the stressful event to improve understanding or foster resourcefulness (approach coping) and those directed at physically or mentally avoiding unpleasant thoughts related to the stressful event (avoidance coping).35 36 |

| Burn-out | A psychological syndrome consisting of three components: emotional exhaustion, a tendency to depersonalise client encounters and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment.40 |

WPV, workplace violence.

Interview guide development

Using an iterative process supported by a literature review, we developed an interview guide to elicit the participant’s perspective of the WPV event and how he/she was impacted. We first reviewed the WPV literature both within and outside of healthcare to guide question development. A multidisciplinary ED safety board at the University of Washington reviewed questions. This revised interview guide was pilot tested with two ED employees (one nurse, one medical assistant) who had experienced a recent WPV event. Two members of the study team reviewed the interview transcript and refined the interview guide. The interview guide underwent another round of testing with a social worker and medical assistant to evaluate new changes (online supplementary file 1).

bmjopen-2019-031781supp001.pdf (53.9KB, pdf)

A non-clinical, female research coordinator with prior experience conducting interviews and focus groups conducted the interviews. The research coordinator was purposely unfamiliar to the participants, had no personal interest in WPV or ED safety, and had no relationship with clinical leadership or human resources at the institution. This was important to preserve participant privacy and to maximise honest and open reflections. The research coordinator received specific training relevant to the project, followed by direct observation with feedback from the investigators. The interview format was semistructured, with follow-up or probative questions for clarification. Interviews ranged from 6 to 24 min in length, with a mean length of 13 min. All interviews were conducted in a private, closed room adjacent to, but separated from, clinical space. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The research coordinator reviewed each transcript for accuracy and removed any identifying information.

Qualitative analysis

Researchers used inductive and deductive qualitative phenomenological approach.25 26 The primary coding team consisted of three board-certified emergency physicians and a social worker with extensive ED and qualitative research experience. Codes were derived from a close reading of transcripts to capture key concepts. Codes were then sorted into higher-order categories based on how they were related or linked.27 The first four transcripts were reviewed by all coders. The research team met periodically to develop and refine the codebook and discuss the coding process. All transcripts were then coded in duplicate using Dedoose V.8.2.14 software (SocioCultural Research Consultants, Los Angeles, California, USA). Codes were compared and disagreements were discussed. If the initial coders could not reach consensus, a third person provided adjudication. Two members of the team reviewed data collection and analysis until saturation was reached and no additional themes were identified. After all transcripts were analysed, the research team met to identify themes and subthemes that accurately summarised coded statements.

Results

Interviews were conducted from January 2017 to May 2017. We obtained thematic saturation with 23 participants. No events involved physical abuse only. Participants included nurses (n=9; 39%), medical assistants (n=5; 22%), security guards (n=5; 22%), attending physicians (n=2; 9%), advanced practitioners (n=1; 4%) and social workers (n=1; 4%). Basic demographic information pertaining to participants is provided in table 3.

Table 3.

Participant demographics

| Demographic | Participants (n=23) |

| Age, year; mean (SD) | 35 (9) |

| Male, n (%) | 13 (57) |

| Profession, n (%) | |

| Nurse | 9 (39) |

| Advanced nurse practitioner | 1 (4) |

| Physician | 2 (9) |

| Social worker | 1 (4) |

| Security guard | 5 (22) |

| Medical assistant | 5 (22) |

| Institution of primary employment, n (%)* | |

| Urban academic safety net hospital | 15 (65) |

| Tertiary referral centre | 4 (17) |

| Community hospital | 4 (17) |

| Experience in healthcare, years; mean (SD) | 10 (7) |

| Experience working in an emergency department, years; mean (SD) | 6 (5) |

*For physicians who work at more than one institution, listing reflects where they were working at the time of enrolment.

Five themes emerged from the data related to the experience of WPV: (1) WPV as a frequent, inevitable occupational hazard; (2) manifestations of burn-out among participants; (3) variability in primary cognitive appraisals of WPV; (4) variability in secondary cognitive appraisals of WPV; (5) reported use of both avoidant and approach coping mechanisms. Themes 1 and 2 are consistent with findings in other studies, identifying WPV as pervasive28 and associating WPV experiences with indicators of burn-out.3 4 We include these confirmatory themes as they were important to the overall objective of the project and helped shape the approach to our analysis. Key definitions of terms are provided in table 2. Quotes illustrating themes appear in the text below, with additional quotes provided in table 4.

Table 4.

Additional quotes to support identified themes about workplace violence appraisals and coping processes

| Themes | Subthemes | Quotes |

| WPV as a frequent, inevitable occupational hazard | “It personally, makes me really sad that this is a component. It’s not even like a maybe; it’s like a when. When it will happen. It’s not an if“. (Nurse, 6) “I just see it as inevitable, occupational hazard, kind of like many shifts and weekends and holidays, like if you’re going to care for the people that no one else wants to care for”. (Physician, 23) |

|

| “It happens every day.… I would say pretty much every day, to some extent, someone is out of control and we have to have, you know, some kind of confrontation like this”. (Security, 1) | ||

| Manifestations of burn-out among participants | Emotional exhaustion | “Even though I think I’m pretty jaded to it, it probably increases stress levels and makes you feel unwell… And you can only take so much and try to help people to get that behavior returned to get violent behaviors it does wear on you physically and emotionally deep down inside”. (Nurse, 9) “There are days that it gets me really, really stressed out. And at the end of the day, I just feel really wiped out, and that I don’t have anything left to give”. (Medical Assistant, 18) |

| Depersonalisation | “He is literally just an (expletive). And so that’s just a bad person. So that doesn’t make me feel bad at all”. (Physician, 14) “And I’ve watched over the years I’ve watched the sweetest nicest people coming to this job and it doesn’t take very long and they’re jaded and they’re changed and it’s sad”. (Nurse, 17) |

|

| Decreased personal efficacy | “I don’t know. I think I went into it thinking it was going to be like… Like I was helping people and fixing and adding to their lives and not… It’s completely different than what I had thought I was going to do. You still have those moments, but when you’re cleaning up the urine and having these people spit at you and you’re putting people in restraints… That’s not what I expected. That’s not what I thought I was going to be doing”. (Nurse, 17) | |

| Diminished job satisfaction | “I think probably a year into my role here as a medical assistant I for sure wanted to be an emergency room nurse and I still want to, but I have lately been definitely thinking about whether or not that it’s something I want to do after I get done with nursing school do I want to continue working in emergency department where this is going to be the norm for my life for the next 30 years? Or do I want to maybe work in a cardiac ICU, somewhere a little quieter something where it’s a little… Where the environment is a little more control… I sometimes question whether or not this is something I want to do full-time, long-term”. (Medical Assistant, 18) “I had a very naïve idea of what the day today actually looks like. And yeah it’s been… this ends up being part of the day today and sometimes it can be a little bothersome and you really like wonder whether or not… If you’ll be able to do it for as long as you hoped you could”. (Nurse, 20) |

|

| Variability in primary cognitive appraisals of WPV | Negative primary appraisals—harm and threat appraisals | “If it gets really personal, people get up in my face, somebody tries to like actually get physical, then I get a lot more upset”. (Nurse, 6) “And so I was typing a note. And I didn’t even realise it and I turned around and she was like behind me and over me. And I felt physically threatened. And realised that not only did I feel physically threatened but there was nobody to call to help me”. (Advanced Practitioner, 22) |

| Positive primary appraisals—challenge appraisals | “It helps me… kind of builds my, I guess, confidence in future incidences. Kind of you get tools from everything. You get new ways to do certain things with each person”. (Security, 15) “You get a little perspective and you realise, look, no one got hurt, surprisingly, it turned out fine. The patient got the care the patient needed. I think the important part is to reflect and say, gosh, how should I handle that differently? What am I going to do going forward differently? And then kind of with some resilience, move on”. (Physician, 23) |

|

| Variability in secondary cognitive appraisals of WPV | Secondary appraisals indicating adequate resources to address WPV events | “Like I do see that certain events do impact other staff members more than it impacts me and I think that for people who do get into those situations, sometimes the social resources may not be available for them to process”. (Nurse, 11) “I’ve always had that mentality where I can kind of just destress and cope with things a lot easier than some people would, like a… or just normal visitors here”. (Security, 7) |

| Secondary appraisals indicating inadequate resources to address WPV events | “I was happy to see three officers come towards me when this event occurred, but none of them were in arm’s reach that would’ve stopped it. They would’ve been able to help after, but they wouldn’t have been able to stop it. Nobody would’ve stopped it. But I just… I don’t know. I just… this is not… doesn’t feel like a safe place”. (Nurse, 17) | |

| Reported use of both avoidant and approach coping mechanisms | Avoidant coping strategies | “Once the patient is either calmed down or they’re placed in the restraints and everyones safe in their rooms, then I usually just like, I’ll sit down, kind of just like do some charting and then kind of take like a good 5 min sit-down session. I’m pretty good after that”. (Medical Assistant, 16) “Honestly, I think the easiest way to cope with things is just to simply just forget about them, kind of like erase it from your memory bank, because I have other patients I’ve got to take care of”. (Nurse, 10) |

| Approach coping strategies | “I just… I depend a lot on my co-workers and making sure, was there anything that I missed? Was there anything I did? Do you know what I mean? Like that made the situation worse or… I should’ve moved off? Whatever. You know what I mean? What could I have done? I’m a good talker, so just talking about it and getting it out there and getting feedback from the people I trust on how things went, that’s how I deal with it”. (Nurse, 9) “And then we have somebody who’s obviously not well, is very much struggling with her relationships with her kind of emotional volatility, that kind of very willfully contributes to her crises. And so when you have somebody responding out of that place, a very compromised place, and so I don’t take it personally. This person has to walk around in that pain. And so those things I think promote my compassion”. (Social worker, 2) |

WPV, workplace violence.

WPV as a frequent, inevitable occupational hazard

The HCWs in this study described WPV as common, noting that it was a standard part of their job. Verbal abuse, such as the use of derogatory language and direct or implied threats, in particular, was noted to be a regular, almost daily occurrence. As one participant commented:

(It happens) every day. Yeah, I mean even if someone isn’t physically violent, people are definitely very loud and vocal towards you in one way or the other. I don’t ever go a work day without being yelled at and called some name. (Medical Assistant, 16)

As implied by the above quote, it is not only verbal aggression that is common. Participants in this study noted that physical violence, far from being rare and unusual, is a constant, tangible threat to HCWs in the ED and a regular feature of their workplace environment. Participants described being kicked, hit, spit at, lunged at and having objects thrown at them, some on an almost daily basis. Violence was perceived as being the norm, ‘an inevitable, occupational hazard’ (Physician, 23) that one simply tolerates and adapts to.

Since it is the norm here… how has it impacted me? Well I just take it as it is. You don’t even think about it. You know what I mean? Okay this is just part of the job. Let’s go. (Nurse, 12)

Manifestations of burn-out among participants

Participants in this study reported manifestations of burn-out due to their frequent exposure to WPV. Burn-out as described by Maslach et al is a psychological phenomenon composed of emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment that negatively impacts one’s ability to provide effective, quality care.29 Burn-out is common among HCWs and has been associated with increased medical errors, higher reported rates of suboptimal patient care, diminished emotional and physical well-being, and increased absenteeism and job turnover.30 31

Many participants in this study reported violence in the workplace as having a negative impact on them both emotionally and physically. Participants described feeling ‘fatigued’, ‘worn out’, ‘stressed out’ and ‘tired’ as a result of repeatedly being the victim of violence. As one participant noted:

A lot of times I’ll come home like pretty stressed out and just really tired, like fatigued from constantly dealing with the verbal and physical abuse that we experience… it does definitely wear on you after a certain point… we’re just constantly dealing with it. So it can get pretty hard. (Security Officer, 7)

For many, these feelings were not limited to the workplace or confined to the time period immediately following the violent event. Rather, these participants described the emotional toll of WPV as being chronic, present in and out of their working environment.

You know it [violence] wears you out for sure. You are exhausted. It takes away from a lot when you’re at home. You sleep a lot because you’re exhausted. It has taken a lot out of you physically or mentally and then it can tax you… I think that’s how it affects me at home, in my personal life. (Nurse, 9)

In addition to emotional exhaustion, a subset of participants made statements consistent with ‘depersonalization’ or ‘dehumanization’. In Maslach’s model of burn-out, this refers to “the development of ‘negative, cynical attitudes and feelings’ toward the recipients of one’s care”.29 For some, this depersonalisation manifested as disapproving or derogatory comments about their patients.

When you’re called to serve snakes every now and then one of them is going to bite you. (Physician, 23)

It [WPV] also changed what I think about people… Yeah, how horrible people really are, or can be. I shouldn’t say are, but can be. (Nurse, 13)

Other participants in this subset directly acknowledged the impact of WPV on their coworkers and their own perceptions of their work and patients, reflecting that the experience of violence made them ‘cold’, ‘jaded’ and less empathic and understanding.

I feel like it has also hardened me a little bit. I think my world-view has shifted a little bit. I find myself being more judgmental and I try to catch myself in that before I let those feelings take over. (Medical Assistant, 18)

The final component of burn-out reported by some of the participants was a diminished sense of their own personal, professional accomplishment. Many participants described a sense of helplessness when discussing their ability to adequately address the physical and mental health needs of their patients, particularly their violent patients who often suffer from mental illness, expressing dissatisfaction both with the few available tools they have to address these behaviours (often chemical or physical restraints) and with the limitations of the larger healthcare system.

It just makes me sad the way it normally does… It sucks because I don’t think he’s fully, I don’t think he fully understands all of his actions. And us sending him off to the bus doesn’t really help anything. I wish there was a way we could help him through treatment or something. Because that’s just going to be somebody else’s problem and his problem. Yeah, I just feel kind of depressed that we didn’t… That we’re a healthcare facility but we didn’t help him. That sucks. (Security Officer, 5)

Variability in primary cognitive appraisals of WPV among participants

The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping is a framework for evaluating the processes of coping with stressful events.32 Stressful experiences are conceptualised as person–environment transactions that depend on the impact of the external stressor. The level of stress experienced depends on appraisals of the situation. When an individual encounters a stressor or stressful event, they engage in a two-step process of cognitive appraisal during which they first interpret the personal significance of the event (primary cognitive appraisal) and subsequently determine whether they have the resources available to overcome or address the event (secondary appraisal).32 33 In this study, HCWs’ primary cognitive appraisals of WPV events varied, with participants describing harm and threat appraisals as well as challenge appraisals.

Negative primary appraisals: harm and threat appraisals

Harm appraisals manifested as HCWs describing negative emotions such as sadness and anger. This was often accompanied by the recognition that it was their job to help the patient, yet frustrating that they had to put themselves in harm’s way to do so.

Just generally, it makes you feel crappy. And you can only be… take so much and try to help people and try to help, and then to get that behavior returned, get violent behaviors, it does wear on you physically and emotionally. (Nurse, 9)

Threat appraisals were expressed through description of negative emotions and interpretations characterised by fear and anxiety. Participants described a real threat to their safety, and this was not a part of the job they were expecting. Participants also reported an underlying sense of uncertainty surrounding a situation, suggesting that safety threats could be hidden and unexpected.

You know any day that you could get hurt. But then a lot of jobs have that risk. But it’s… you didn’t go into it thinking that. When people became nurses they didn’t anticipate that… I don’t know… I never anticipated that I would be used and abused as I have been. (Nurse, 17)

Positive primary appraisals: challenge appraisals

In contrast to more negative interpretations, some ED HCWs described challenge appraisals, viewing WPV events as an opportunity to grow or gain due to a stressful event. HCWs would cite the opportunity to improve performance the next time they encountered a violent patient, and described seeking input from their colleagues to identify areas of improvement. As one nurse stated:

I feel like the way I deal with it is just trying to look at a situation and see how it can maybe better improve… It’s like okay, I can improve here or here. (Nurse, 10)

In these challenge appraisals, WPV events were seen as both an educational experience to prepare them for the next encounter with WPV and as a way to build a sense of professional confidence.

Variability in secondary cognitive appraisals of WPV among participants

In contrast to primary appraisals that reflect the meaning an individual attributes to an event, secondary appraisals reflect an individual’s belief that they have (or do not have) the resources necessary to cope with the situation and its aftermath.32 HCWs in this study demonstrated significant variability in their secondary appraisals of WPV events, with some participants indicating that they possessed adequate resources to overcome WPV, and other indicating that they did not.

Secondary appraisals indicating adequate resources to address WPV events

Participants who viewed themselves as having adequate resources to address WPV events described factors that enabled their ability to handle violent events better than their colleagues. This is sometimes attributed to past experiences in similarly stressful jobs, personal traits, physical stature or specialised training (eg, military or martial arts). Several note that, in their view, they do not need to cope.

Well from a physical stand… the confrontation standpoint, yes. I did kick boxing for 15 years and so I, I’m not worried about that, but from de-escalation, I just leave the room. It’s not a big deal. So either way, yes, it’s fine. (Physician, 14)

I mean, it just is what it is. I don’t know that I need to cope with it. (Advanced Practitioner, 22)

Some HCWs reported a belief that they are less susceptible to the negative impact of WPV and are able to tolerate more violence without experiencing any negative impact.

… I can tolerate I think a little bit more than maybe somebody else in a different emergency room just because we just have people that are just out of control and we know what to do with them and we handle it. (Nurse, 13)

Secondary appraisals indicating inadequate resources to address WPV events

In contrast to those who felt they were adequately resourced to deal with WPV events, another subset of participants described feeling under-resourced and therefore incapable of successfully managing WPV events. This often was couched in terms of a lack of control over patient behaviour.

I mean I can say… he wasn’t safe at all. For him and for me, because if I could be close, he could do anything. He has one hand is unrestrained, he can punch me, he could do anything. (Medical Assistant, 3)

Likewise, HCWs reported a sense of uncertainty or lack of control in their healthcare system’s response mechanisms or protection measures currently in place. This included a perceived lack of response or concern from leadership and a sense that HCW well-being was not a priority.

We don’t have resources available, especially out in the front waiting room, I can’t hear overhead pages. In order to call for help I have to overhead page something and I can’t see any response, or I have to radio and pray somebody comes. We have a silent alarm, but that doesn’t necessarily mean a lot of things. And if it’s something like that where you want to not get a phone out and say, can security come to the front, and really escalate the patient in front of you just because it’s really difficult to manage those situations. (Nurse, 6)

And I just keep thinking, it’s going to take something really bad happening before they put security in the back. Or do something to make us feel safer. (Nurse, 17)

Reported use of both avoidant and approach coping mechanisms among participants

Coping is defined as the cognitive and behavioural efforts to master, reduce or tolerate the internal and/or external demands that are created by a stressful event.34 Coping strategies can be categorised as avoidant or approach-oriented (table 2).35 36 Just as the participants in this study described significant variability in their cognitive appraisals of WPV events, so too did they report a variety of coping strategies.

Avoidant coping strategies

Participants described multiple different coping strategies to avoid or decrease the negative emotions associated with the WPV event. Participants often described taking a few minutes to separate themselves from the situation both physically and emotionally.

I think I… you do sometimes need to like take some time, like away. Like sometimes it’s a great time to take your 15 min break and, like, sit down and, like, chill. (Nurse, 12)

This was described as a way to allow individuals to continue their work. In some cases, HCWs described physical separation. This distance was perceived as creating a separation between work events and home life, supporting an emotional separation.

So I intentionally don’t live near the hospital, because I like to have that physical separation from work. (Advanced Practitioner, 22)

Immediately following a WPV event, avoidant strategies may help HCWs adapt. More chronic avoidant behaviour, however, was also described. For example, a number of participants acknowledged using alcohol as a coping strategy.

Alcohol. Probably. More than anything, you go home and you’re like… nobody would believe me. There’s nobody at home to tell. (Nurse, 17)

Approach-oriented coping strategies

Unlike avoidant coping strategies, approach coping strategies involve directly managing or ameliorating the cause of stress.35 Approach strategies generally manifested as a rationalisation of the patient’s behaviour. Several HCWs justified patient behaviour in terms of their mental illness.

He is not pointedly violent towards individuals. I think just because he is just… he is out his… out of what I believe (is) his normal mental state. I don’t think he knows… he really knows a lot of what’s going on around him. He has a very limited grasp of his reality at this time. And that’s okay and we’re here to help him out. (Security, 4)

Reviewing a situation and creating strategies for the next event is another example of approach coping. HCWs reported reviewing events with coworkers, both as a way to learn from others’ perceptions of the event and as a way to discuss their feelings with others that had similar experiences. The sense of support and the ability to ‘depend on’ and ‘look to’ other staff for support was almost universal.

But I think taking time away and then if it is something that’s violent that really bothered you, I think talking, like, to a co-worker, which I think everybody is really good about here. I think there’s always somebody checking on you, like, are you okay? (Nurse, 11)

Discussion

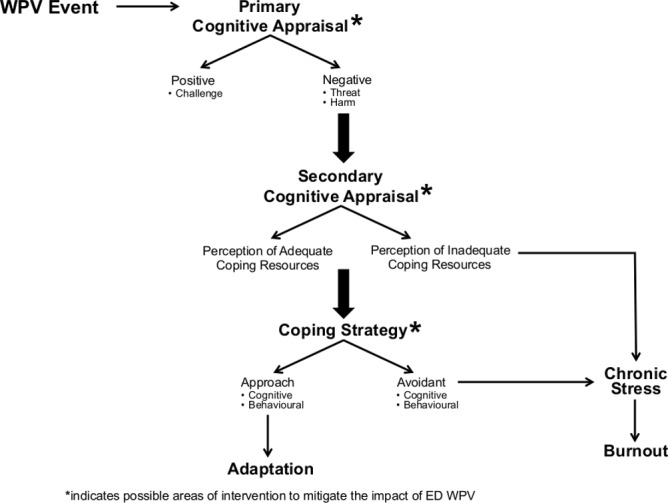

Our findings were consistent with other studies, highlighting the perception that WPV is pervasive in EDs and that HCWs connect their WPV experience with manifestations of burn-out.3 4 21 We also identified three novel themes not previously discussed in the healthcare WPV literature. These themes highlight the variability in how HCWs appraise WPV events and what coping mechanisms they employ to deal with WPV. In the following discussion, we draw from the stress and violence literature and propose a framework (figure 1) that is based on the transaction-based stress model.32 37–39 This framework illustrates how the cognitive and behavioural processes of appraisal and coping may mediate the relationship between WPV and burn-out, thus highlighting potential targets for intervention.32 37–39

Figure 1.

Proposed model for the processes linking workplace violence and burn-out.

All occupations, including those within healthcare, have sources of stress; that is, taxing features or experiences that cause a physical or mental discomfort. While unpleasant, the negative effects of these simple stressors is temporary, with the individual quickly returning to their usual states of happiness and functioning. Burn-out, in contrast, is a chronic condition, characterised by a progressive and sustained decline in function and well-being.40 41 Several studies have detailed an association between the experience of WPV and the development of burn-out among HCWs.3 4 42 Unfortunately, WPV, particularly verbal abuse, is difficult to eliminate from healthcare. While efforts to decrease the incidence of WPV should continue, it is important to note that complete eradication of WPV, especially non-physical violence, is not feasible in certain settings. The goal then becomes mitigating the effects of WPV, and more specifically, understanding and preventing the cognitive and behavioural processes that lead to burnout.

Multiple studies demonstrate that WPV events affect individuals differently, with some experiencing little to no change in their functioning, whereas others suffer significant physical and psychological health symptoms, including burn-out.43 Our work is in line with research in other fields, suggesting that appraisal and coping may at least partially explain this variability (figure 1).44 45 Primary and secondary appraisals ‘converge’ for an individual and determine whether the WPV event presents a significant stressor and potential stimulus for burn-out.39

We heard from multiple HCWs who described negative primary appraisals, reflecting feelings of anger and frustration as well as a sense of threat and uncertainty. While there is no ‘right’ appraisal, negative appraisals are highly stressful and are positively related to burn-out.37 Moreover, when a WPV event is appraised as harmful or threatening, and their secondary appraisal indicates an inability to meet the demand of the situation or cope with its aftermath, the risk of chronic stress and burn-out may increase.37 39

Not all participants appraised WPV events as harmful or threatening. Several described challenge primary appraisals, seeing opportunity for self-growth and the ability to improve and perform better or differently the next time. Likewise, some secondary appraisals reflected the participant’s belief that they were better able to handle WPV because of physical attributes, training or mental toughness. Having this sense of control over the situation or environment (1) facilitates an individual’s ability to appraise WPV events as challenges rather than threats and (2) may decrease burn-out related to workplace stress.37 To facilitate the development of challenge appraisals in HCWs, ED and institutional leadership should foster a true sense of HCW control over their environment.

The way an individual appraises a WPV event directly affects the coping strategy employed.46 Coping strategies that foster avoidance or escape are positively related to burn-out, whereas more direct, approach-oriented strategies negatively relate to chronic stress and burn-out.47 48 In our study, participants described a number of different coping strategies that could be adaptive and/or maladaptive. Avoidant coping strategies might be useful, and even necessary, immediately following a WPV event, for example, if a HCW has to emergently switch tasks to provide care to an unstable patient.36 However, long-term avoidant coping leads to less adaptation as compared with more direct, approach-oriented coping, which is thought to allow individuals to experience high stress situations without experiencing long-term physical and psychological trauma.49 Healthcare institutions and ED leadership should help employees identify and adopt the cognitive and behavioural processes that support approach-oriented coping strategies.

Both cognitive appraisal and coping are processes as opposed to traits.39 This is an important distinction. If we assume that the impact of a WPV event is dependent on fixed personality traits, then we cannot change the outcome. Because cognitive appraisals and coping strategies are processes, they are amenable to change. If we can alter how an individual interprets and chooses to respond to a WPV event, we can potentially decrease or prevent related negative outcomes such as chronic stress and burn-out.50 Research suggests that appraisals and choice of coping strategy can be modified by the use of cognitive-behavioural techniques.51 A meta-analysis demonstrated superiority of cognitive-behavioural techniques over multimodal interventions, relaxation training and organisation-focused interventions when treating work-related stress.52 Such an intervention could provide a viable and practical way to decrease the deleterious effects of ED WPV on HCWs. Moreover, cognitive-behavioural techniques implemented prior to starting a shift could increase optimistic explanatory style, lower levels of catastrophic thinking and increase constructive envisioning of the future, all of which can help less resilient individuals who experience WPV cope more effectively.53 Such interventions warrant further research, as they have the potential to decrease the deleterious effects of WPV and promote HCW well-being.

Limitations

This study has several important limitations, primarily related to selection bias. Our sample was limited to a purposive sample of 23 HCWs practising within a single US city. Existing research recognises cultural differences in perceptions and reactions to violence.54 55 Although early work suggests similar links between WPV and burn-out, it will still be important to evaluate the mechanisms and models proposed here across multiple countries and healthcare settings.

We did collect data across an interprofessional sample of HCWs practising in three different institutions representing a community hospital, a regional tertiary referral centre and an urban academic safety net hospital. However, it is still possible that the themes identified in this study may not generalise to different patient and HCW populations. The largest percentage of participants was recruited at the urban safety net hospital where a disproportionate number of patients have psychiatric comorbidities. This could have caused an overstatement of findings or a heightened focus on mental illness as a primary contributor.

We did not collect race or ethnicity data from our participants, thus we cannot report if there is an imbalance in the sample that could influence our data. Similarly, we did not track the demographics of those individuals who were approached but did not participate. Multiple individuals consented but were then called away for clinical work and were not able to be interviewed. We do not have demographic data for those individuals and thus cannot guarantee that there was no omission bias. The investigators may have inherent biases that could influence analysis and interpretation of the results. All coders were women and 75% were Emergency Medicine physicians employed at two out of three data collection sites. While this could be a benefit in terms of interpreting institution-specific terminology, there could also be a reporting bias when interpreting comments.

Finally, interviews were shorter than in other qualitative studies.56 This was done intentionally to facilitate immediate data collection and thereby reduce recall bias present in other WPV healthcare-related studies. To our knowledge, this is the first study to interview HCWs immediately following a WPV event.

Conclusion

WPV in healthcare is seen as pervasive and directly impacting the safe, effective delivery of patient care. Healthcare institutions must work to decrease the incidence of physical WPV and also include efforts to mitigate the negative impact of both verbal and physical WPV on HCWs. We identify both cognitive appraisals and coping processes as viable targets for interventions aimed at ameliorating the impact of WPV on HCWs. Research in other fields with high levels of WPV may help inform interventions to decrease chronic stress and burn-out related to WPV. This important work will require translating such interventions to healthcare as well as identifying appropriate proximal and distal outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MCV and AKC contributed equally to this manuscript and are joint first authors on this manuscript. MCV and RF conceived of the study and analysis plan. All authors (MCV, EDR, AKC, LH, MM, NJS and RF) participated in developing interview tools. MCV, EDR, AKC, LH, MM and RF performed analyses. MCV, AKC and RF wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RF and AKC drafted the conceptual model presented in the manuscript. All authors (MCV, EDR, AKC, LH, MM, NJS and RF) contributed to interpretation of the data, substantially edited the manuscript and approved of the final version. RF takes final responsibility for the manuscript as a whole.

Funding: RF, MCV, AKC, LH, MM and NJS were funded by the State of Washington, Department of Labor and Industries, Safety and Health Investment Projects, 2014XH00293.

Disclaimer: The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: RF, MCV, LH, MM, AKC and NJS received funding from the State of Washington, Department of Labor and Industries, Safety and Health Investment Projects. RF, EDR, AKC and MCV received funding from the Department of Defense. RF and EDR received funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This work was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board (STUDY00000502).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Gates DM, Gillespie GL, Succop P. Violence against nurses and its impact on stress and productivity. Nurs Econ 2011;29:59–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gandhi TK, Kaplan GS, Leape L, et al. Transforming concepts in patient safety: a progress report. BMJ Qual Saf 2018;27:1019–26. 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Erdur B, Ergın A, Yüksel A, et al. Assessment of the relation of violence and burnout among physicians working in the emergency departments in Turkey. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2015;21 10.5505/tjtes.2015.91298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Copeland D, Henry M. The relationship between workplace violence, perceptions of safety, and professional quality of life among emergency department staff members in a level 1 trauma centre. Int Emerg Nurs 2018;39:26–32. 10.1016/j.ienj.2018.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pinar T, Acikel C, Pinar G, et al. Workplace violence in the health sector in Turkey: a national study. J Interpers Violence 2017;32:2345–65. 10.1177/0886260515591976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Babiarczyk B, Turbiarz A, Tomagová M, et al. Violence against nurses working in the health sector in five European countries—pilot study. Int J Nurs Pract 2019;25:e12744 10.1111/ijn.12744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fute M, Mengesha ZB, Wakgari N, et al. High prevalence of workplace violence among nurses working at public health facilities in southern Ethiopia. BMC Nurs 2015;14:9 10.1186/s12912-015-0062-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang L, Wang A, Xie X, et al. Workplace violence against nurses: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud 2017;72:8–14. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lu L, Dong M, Wang S-B, et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against health-care professionals in China: a comprehensive meta-analysis of observational surveys. Trauma Violence Abuse 2018:152483801877442 10.1177/1524838018774429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mayhew C, Chappell D. Workplace violence in the health sector—a case study in Australia. J Occup Health Safety 2003;19. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mayer BW, Smith FB, King CA. Factors associated with victimization of personnel in emergency departments. J Emerg Nurs 1999;25:361–6. 10.1016/S0099-1767(99)70090-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gates DM, Ross CS, McQueen L. Violence against emergency department workers. J Emerg Med 2006;31:331–7. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. May DD, Grubbs LM. The extent, nature, and precipitating factors of nurse assault among three groups of registered nurses in a regional medical center. J Emerg Nurs 2002;28:11–17. 10.1067/men.2002.121835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luck L, Jackson D, Usher K. Stamp: components of observable behaviour that indicate potential for patient violence in emergency departments. J Adv Nurs 2007;59:11–19. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04308.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kowalenko T, Gates D, Gillespie GL, et al. Prospective study of violence against ED workers. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:197–205. 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wassell JT. Workplace violence intervention effectiveness: a systematic literature review. Saf Sci 2009;47:1049–55. 10.1016/j.ssci.2008.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wong AH, Wing L, Weiss B, et al. Coordinating a team response to behavioral emergencies in the emergency department: a simulation-enhanced interprofessional curriculum. West J Emerg Med 2015;16:859–65. 10.5811/westjem.2015.8.26220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beech B, Leather P. Workplace violence in the health care sector: a review of staff training and integration of training evaluation models. Aggress Violent Behav 2006;11:27–43. 10.1016/j.avb.2005.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gillespie GL, Gates DM, Kowalenko T, et al. Implementation of a comprehensive intervention to reduce physical assaults and threats in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs 2014;40:586–91. 10.1016/j.jen.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American College of Emergency Physicians ACEP emergency department violence poll research results. Alexandria, VA: Marketing General Incorporated; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wolf LA, Delao AM, Perhats C. Nothing changes, nobody cares: understanding the experience of emergency nurses physically or verbally assaulted while providing care. J Emerg Nurs 2014;40:305–10. 10.1016/j.jen.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morken T, Johansen IH, Alsaker K. Dealing with workplace violence in emergency primary health care: a focus group study. BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:51 10.1186/s12875-015-0276-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Violence in emergency departments is increasing, harming patients, new research finds. Available: http://newsroom.acep.org/2018-10-02-Violence-in-Emergency-Departments-Is-Increasing-Harming-Patients-New-Research-Finds [Accessed 8 Jan 2019].

- 24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Violence: occupational hazards in hospitals Cincinnati NIOSH; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morse JM, Field PA. Nursing research: the application of qualitative approaches. Nelson Thornes, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ashton RA, Morris L, Smith I. A qualitative meta-synthesis of emergency department staff experiences of violence and aggression. Int Emerg Nurs 2018;39:13–19. 10.1016/j.ienj.2017.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory : Evaluating stress: a book of resources. 3rd edn Lanham, MD, US: Scarecrow Education, 1997: 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lu DW, Dresden S, McCloskey C, et al. Impact of burnout on self-reported patient care among emergency physicians. West J Emerg Med 2015;16:996–1001. 10.5811/westjem.2015.9.27945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goldberg R, Boss RW, Chan L, et al. Burnout and its correlates in emergency physicians: four years’ experience with a wellness booth. Acad Emerg Med 1996;3:1156–64. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03379.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lazarus RS. Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Folkman S. Personal control and stress and coping processes: a theoretical analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol 1984;46:839–52. 10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krohne HW. Individual differences in coping : Zeidner M, Endler NS, Handbook of coping: theory, research, applications. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1996: 381–409. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Roth S, Cohen LJ. Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. Am Psychol 1986;41:813–9. 10.1037/0003-066X.41.7.813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gomes AR, Faria S, Gonçalves AM. Cognitive appraisal as a mediator in the relationship between stress and burnout. Work Stress 2013;27:351–67. 10.1080/02678373.2013.840341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Anshel MH. A conceptual model and implications for coping with stressful events in police work. Crim Justice Behav 2000;27:375–400. 10.1177/0093854800027003006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, et al. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;50:992–1003. 10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB. Historical and conceptual development of burnout : Schaufeli WB, Maslach C, Marek T, Professional burnout: recent developments in theory and research. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis, 1993: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brill PL. The need for an operational definition of burnout. Fam Community Health 1984;6:12–24. 10.1097/00003727-198402000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu W, Zhao S, Shi L, et al. Workplace violence, job satisfaction, burnout, perceived organisational support and their effects on turnover intention among Chinese nurses in tertiary hospitals: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019525 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Agaibi CE, Wilson JP. Trauma, PTSD, and resilience: a review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse 2005;6:195–216. 10.1177/1524838005277438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cooper CL, Cooper CP, Dewe PJ. Organizational stress: a review and critique of theory, research, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Goh YW, Sawang S, Oei TPS. The revised transactional model (RTM) of occupational stress and coping: an improved process approach. Aust N Z J Organ Psychol 2010;3:13–20. 10.1375/ajop.3.1.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Gruen RJ, et al. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;50:571–9. 10.1037/0022-3514.50.3.571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Koeske GF, Kirk SA, Koeske RD. Coping with job stress: which strategies work best? J Occup Organ Psychol 1993;66:319–35. 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1993.tb00542.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Leiter MP. Coping patterns as predictors of burnout: the function of control and escapist coping patterns. J Organ Behav 1991;12:123–44. 10.1002/job.4030120205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J Pers Soc Psychol 2004;86:320–33. 10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. V Papathanasiou I, Tsaras K, Neroliatsiou A, et al. Stress: concepts, theoretical models and nursing interventions. AJNS 2015;4:45–50. 10.11648/j.ajns.s.2015040201.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gardner B, Rose J, Mason O, et al. Cognitive therapy and behavioural coping in the management of work-related stress: an intervention study. Work Stress 2005;19:137–52. 10.1080/02678370500157346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. van der Klink JJ, Blonk RW, Schene AH, et al. The benefits of interventions for work-related stress. Am J Public Health 2001;91:270-6 10.2105/ajph.91.2.270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schaubroeck JM, Riolli LT, Peng AC, et al. Resilience to traumatic exposure among soldiers deployed in combat. J Occup Health Psychol 2011;16:18–37. 10.1037/a0021006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cooper CL, Swanson N. Workplace violence in the health sector: state of the art. Geneva: Organización Internacional de Trabajo, Organización Mundial de la Salud, Consejo Internacional de Enfermeras Internacional de Servicios Públicos, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Poster EC. A multinational study of psychiatric nursing staff’s beliefs and concerns about work safety and patient assault. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 1996;10:365–73. 10.1016/S0883-9417(96)80050-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wong AH-W, Combellick J, Wispelwey BA, et al. The patient care paradox: an interprofessional qualitative study of agitated patient care in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2017;24:226–35. 10.1111/acem.13117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Occupational Safety and Health Administration Guidelines for preventing workplace violence for health care social service workers (OSHA 3148-06R 2016) U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Searle BJ, Auton JC. The merits of measuring challenge and hindrance appraisals. Anxiety Stress Coping 2015;28:121–43. 10.1080/10615806.2014.931378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031781supp001.pdf (53.9KB, pdf)