Abstract

Objective

To summarise study descriptions of the James Lind Alliance (JLA) approach to the priority setting partnership (PSP) process and how this process is used to identify uncertainties and to develop lists of top 10 priorities.

Design

Scoping review.

Data sources

The Embase, Medline (Ovid), PubMed, CINAHL and the Cochrane Library as of October 2018.

Study selection

All studies reporting the use of JLA process steps and the development of a list of top 10 priorities, with adult participants aged 18 years.

Data extraction

A data extraction sheet was created to collect demographic details, study aims, sample and patient group details, PSP details (eg, stakeholders), lists of top 10 priorities, descriptions of JLA facilitator roles and the PSP stages followed. Individual and comparative appraisals were discussed among the scoping review authors until agreement was reached.

Results

Database searches yielded 431 potentially relevant studies published in 2010–2018, of which 37 met the inclusion criteria. JLA process participants were patients, carers and clinicians, aged 18 years, who had experience with the study-relevant diagnoses. All studies reported having a steering group, although partners and stakeholders were described differently across studies. The number of JLA PSP process steps varied from four to eight. Uncertainties were typically collected via an online survey hosted on, or linked to, the PSP website. The number of submitted uncertainties varied across studies, from 323 submitted by 58 participants to 8227 submitted by 2587 participants.

Conclusions

JLA-based PSP makes a useful contribution to identifying research questions. Through this process, patients, carers and clinicians work together to identify and prioritise unanswered uncertainties. However, representation of those with different health conditions depends on their having the capacity and resources to participate. No studies reported difficulties in developing their top 10 priorities.

Keywords: James Lind Alliance, priority setting partnership, patient and public involvement, patient involvement in research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first scoping review of published studies using the James Lind Alliance (JLA) approach available with involvement of patients, carers and the public in the setting the research agenda.

The weakest voices often lack representation, which could limit the generalisability of these priorities to these populations.

Because a scoping review approach was used, the quality of the articles was not assessed prior to inclusion.

We were not in contact with the JLA Coordinating Centre and search in all relevant literature, such as grey literature and studies, which do not described all steps of the JLA process, might have limited our results.

A limitation of this scoping review was our inclusion of only English-language articles.

Introduction

Over the past decade, patient and public involvement (PPI) has been highlighted worldwide in both health research agendas and the development of next-step research projects.1 PPI has been defined as ‘experimenting with’ as opposed to ‘experimenting on’ patients or the public.2 PPI allows patients to actively contribute, through discussion, to decision-making regarding research design, acceptability, relevance, conduct and governance from study conception to dissemination.3 However, PPI may also involve active data collection, analysis and dissemination.4

Researchers have noted that involving healthcare service users, the public and patients improves research quality, relevance, implementation and cost-effectiveness; it also improves researchers’ understanding of and insight into the medical and social conditions they are studying,1 5 although such evidence is still relatively limited.4

The James Lind Alliance (JLA) is a UK-based non-profit initiative that was established in 2004. The JLA process is focused on bringing patients, carers and clinicians together, on an equal basis, in a priority setting partnership (PSP) to define and prioritise uncertainties relating to a specific condition.6 Hall et al 7 note that the JLA aims to raise awareness among research funding groups about what matters most to both patients and clinicians, in order to ensure that clinical research is both relevant and beneficial to end users. According to the JLA Guidebook,6 uncertainties and how to prioritise these are key features of the JLA process. The process begins by defining unanswered questions (ie, ‘uncertainties’) about the effects of treatment and healthcare—questions that cannot be adequately answered based on existing research evidence, such as reliable, up-to-date systematic reviews—and then prioritises the uncertainties based on their importance. The most recent version of the JLA Guidebook explains that many PSPs interpret the definition of treatment uncertainties broadly. They may interpret ‘treatments’ to include interventions such as care, support and diagnosis. This approach has been an important development and one that helps the JLA adapt to the changing health and care landscapes, as well as to the changing needs of its users.6

The JLA provides facilitation and guidance in the identification and prioritisation processes. This process forms part of a widening approach to PPI in research. The characteristics of the PSP process are (1) setting up a steering group to supervise all aspects of the study; (2) establishing a PSP; (3) assembling potential research questions; (4) processing, categorising, and summarising those research questions; and (5) determining the top 10 research priorities through an interim process and a final priority setting workshop using respondent ranking and consensus discussion. To ensure that all voices in the workshop are heard, the JLA supports an adapted nominal group technique (NGT) for PSPs when choosing their priorities. NGT is a well-established and well-documented approach to decision-making.6

To our knowledge, there is a gap in existing research given that no review has yet been published describing how the JLA approach is used to establish steering groups, set up PSPs, gather uncertainties, summarise uncertainties and determine the lists of top 10 priorities. Thus, the objective of this scoping review was to summarise study descriptions of the JLA approach to the PSP process, and how this process is used to identify uncertainties and develop lists of top 10 priorities.

How do the studies describe the characteristics of the PSPs and, elaborating on aspects, how have they operationalised the JLA methods?

How do the studies describe involvement of different user groups?

What processes are used to gather and verify uncertainties?

Methods

Identifying relevant studies

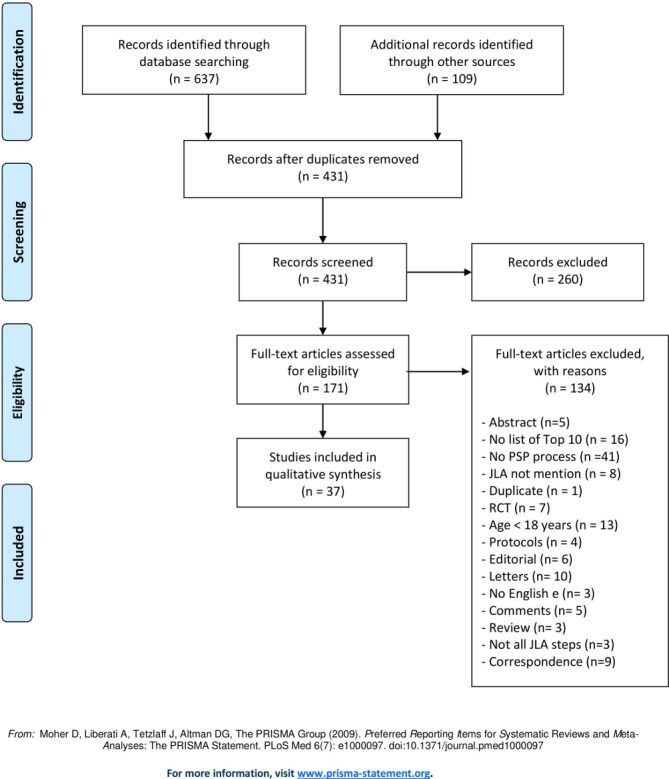

A systematic search was conducted up to October 2018 using five databases: Embase, Medline (Ovid), PubMed, CINAHL and the Cochrane Library. The search strategy in each database was «james lind*» OR «priorit* setting partnership*». We also searched in JLA website. This search identified 746 records and 431 potentially relevant citations. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts based on our inclusion and exclusion criteria, the full text of 171 studies was examined in greater detail. A total of 37 studies met all criteria for review and were subsequently investigated. These numbers were verified by a university librarian (see flowchart, figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram. JLA, James Lind Alliance; PSP, priority setting partnership; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Selecting relevant studies

A prescreening process included reviewing the search results and excluding all articles that were not research studies, that were unavailable in full text or that clearly did not involve the JLA PSP approach. At least two authors screened the remaining articles using the inclusion and exclusion criteria presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|

|

JLA, James Lind Alliance; PSP, priority setting partnership.

Charting data

A data extraction sheet was created to collect studies’ demographic details, aims, samples and patient groups. The sheet was used to collect methodological details about the studies’ PSPs, including descriptions of stakeholders, lists of top 10 priorities, descriptions of the roles of JLA facilitators and PSP stages.

Procedure

In addition to the first author, one of the other authors evaluated each article, and individual and comparative appraisals were discussed among the authors until agreement was reached. At least two authors were involved in each of the study selection procedures. A predefined procedure was developed for consulting a third author, or the whole research team, in cases of discrepancies; however, this was never necessary (ie, decisions to accept or reject unclear articles were based on a dyad consensus). The first author and one other author extracted the characteristics and findings of each study.

Quality appraisal

The most recent JLA Guidebook 6 served as the context for investigating the descriptions of the studies’ methods. A quality assessment was not included in the remit of this scoping review.8

Patient and Public Involvement

No patient was involved.

Collating, summarising and reporting results

Findings related to the scoping review’s research questions, based on the JLA approach, were extracted and documented. The information shown in table 2 includes the studies’ aims, suggested uncertainties and—depending on the version of the JLA guidelines used—how these uncertainties were determined. We also collected information on the stakeholders (including members of the PSP), whether a JLA advisor/facilitator was used, and the JLA process stages: (1) setting up a PSP, (2) gathering uncertainties, (3) data processing and verifying uncertainties, (4) interim priority setting and (5) final priority setting. The results are presented based on the JLA Guidebook steps, which have remained consistent across versions.6 9–11

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| Year Author Country |

Aim of the study | 1. User group* 2. JLA Guidebook, year and version 3. Age of patient† 4. Health condition/disease 5. Number of initial uncertainties and participants or returned surveys or uploaded research priorities |

Steering group‡ identification and management of partners/stakeholders | JLA The role of the facilitator/ advisor |

PSP Number of steps Description of stages NGT |

| 2010 Buckley et al 12 UK |

To identify and prioritise ‘clinical uncertainties’ relating to treatment of UI. |

|

Organisations were identified, which represented or could advocate for patients, their informal carers and clinicians involved in the treatment or management. | NR | Five steps+NGT

|

| 2011 Eleftheriadou et al 13 UK |

To stimulate and steer future research in the field of vitiligo treatment by identifying the 10 most important research areas for patients and clinicians. |

|

Professional bodies and patient support groups; steering group included 12 members with knowledge and interest in vitiligo. | The Vitiligo PSP adopted the methods advocated by the JLA, which were refined to meet the needs of this particular PSP. | Five steps 1. Initiation. 2. Consultation. 3. Collation. 4. Ranking exercise (Interim prioritisation exercise). 5. Final Prioritisation Workshop. |

| 2012 Gadsby et al 14 UK |

To collect uncertainties about the treatment of type 1 diabetes from patients, carers and health professionals, and to collate and prioritise these uncertainties to develop a list of top 10 of research priorities. |

|

Members with perspectives in paediatrics and primary care, users of type 1 diabetes services, including patients and carers; a steering group of representatives from these organisations (n=9 plus an independent information specialist) and partner organisations. |

JLA, being represented on the steering group | Six steps

|

| 2013 Batchelor et al 15 UK |

To identify the uncertainties in eczema treatment that are important to patients who have eczema, their carers and the healthcare professionals who treat them. |

|

The steering group comprised four patients and carers, including a representative from the National Eczema Society, four clinicians, two dermatologists, a dermatology nurse specialist and a GP and three researchers⁄administrators at the Centre of Evidence-Based Dermatology. | The PSP was coordinated from the Centre of Evidence-Based Dermatology in Nottingham, with oversight by a representative of JLA, who was the independent chair of the PSP steering group. | Five steps 1. Initiation. 2. Consultation—collection of treatment uncertainties. 3. Collation and treatment uncertainties. 4. Ranking of treatment uncertainties. 5. Workshop to develop research questions. |

| 2013 Davila-Seijo et al 45 Spain |

To describe and prioritise the most important uncertainties about dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa treatment shared by patients, carers and healthcare professionals in order to promote research in those areas. |

|

The steering group comprised eight people, including patients/carers, a representative from the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Association Spain, a clinician; dermatologists, nurses and researchers; and the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. | Workshop advocated by the JLA | Five steps+NGT

|

| 2013 Hall et al 7 UK |

To describe the tinnitus PSP in providing a platform for patients and clinicians to collaborate, to identify and to prioritise uncertainties or ‘unanswered questions’. |

|

Membership of the steering group provided a broad representation of people from the field of tinnitus, including professional bodies, charities and advocators for people with tinnitus. The wider working partnership included 56 major UK stakeholders, including individual advocators for people with tinnitus, support groups, hospital centres and commercial organisations. |

Independent chairperson representing the JLA | Seven steps

|

| 2014 Deane et al 16 UK |

To identify and prioritise the top 10 evidential uncertainties that impact on everyday clinical practice for the management of Parkinson’s disease. |

|

The steering group consisted of representatives from Parkinson’s UK (n=8) and the Cure Parkinson’s Trust (n=1), patients (n=2), carers (n=2), clinical consultants (n=2) and a Parkinson’s disease nurse specialist (n=1). Those from Parkinson’s UK included representatives with expertise in research development, policy and campaigns (n=5), information and support worker services (n=1), advisory services (n=1) and resources and diversity (n=1). | The JLA provided an independent chair, advised on the methodology, and facilitated the process. | Five steps+NGT

|

| 2014 Ingram et al 17 UK |

To generate a top 10 list of hidradenitis suppurativa research priorities, from the perspectives of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, carers and clinicians, to take to funding bodies. |

|

The steering committee included five patients and carers, including two representatives of the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Trust UK patient organisation; six dermatologists, including two trainees, two dermatology specialist nurses, a plastic surgeon, a general practitioner; the JLA representative and an administrator and stakeholders from various Royal College-related groups. | Three JLA facilitators or four facilitators | Five steps+NTG

|

| 2014 Manns et al 36 Canada |

To improve understanding of kidney function and disease, including those for specific areas, such as dialysis therapies. |

|

The priority setting process was initiated with the formation of an 11-person steering group, which included patients, a caregiver, clinicians, an employee of the Kidney Foundation of Canada and an expert in the JLA approach. |

Experienced facilitators | Five steps+NGT

|

| 2014 Pollock et al 5 UK |

To identify the top 10 research priorities relating to life after stroke, as agreed by stroke survivors, carers and clinicians. |

|

A steering group comprising a stroke survivor, carers, a nurse, a physician, allied clinicians, a researcher and representatives from key national stroke charities/patient organisations and from the JLA; the Scottish Government’s National Advisory Committee for Stroke. This project was completed in partnership with Chest Heart & Stroke Scotland and the Stroke Association in Scotland. | The facilitators were briefed by members of the JLA on the importance of ensuring equitable participation of all group members | Six steps+NGT

|

| 2014 Rowe et al 18 UK |

To Identify research priorities relating to sight loss and vision through consultation with patients, carers and clinicians. |

|

The steering committee included patient representatives and eye health professionals. A steering committee and data assessment group comprising the authors of this article oversaw the process and stakeholders from various Royal College-related groups. The Steering Committee also included patient representatives and eye health professionals. |

Representative from the JLA convened meetings of the steering committee | Five steps+NGT

|

| 2014 Uhm et al 19 UK |

To discover the research questions for preterm birth and to grade them according to their importance for infants and families. |

|

Potential partners were identified through a process of peer knowledge and consultation, steering group members’ networks and JLA’s existing register of affiliates. Stakeholders from various Royal College-related groups. | Two facilitators from the JLA | Five steps+NGT

|

| 2015 Barnieh et al 37 Canada |

To assess the research priorities of patients on or nearing dialysis within Canada and their carers and clinicians. |

|

The 11-person steering group comprised four patients, one carer, three clinicians, an employee of the Kidney Foundation of Canada (an important funder of kidney research in Canada), an expert in the JLA approach and a researcher. The steering group included individuals from across Canada and different stakeholders. | Facilitators with experience in the JLA methods lead the workshop | Four steps+NGT 1. Form PSP. 2. Gather research uncertainties. 3. Process and collate submitted research uncertainties. 4. Final priority setting workshop. |

| 2015 Boney et al 20 UK |

To identify research priorities for anaesthesia and perioperative medicine. |

|

The steering group comprised representatives of the funding partner organisations, patients and carers, and the JLA. Almost 2000 stakeholders contributed their views regarding anaesthetic and perioperative research priorities. Stakeholders were defined as ‘any person or organisation with an interest in anaesthesia and perioperative care’. |

Steering group chaired by the JLA adviser | Eight steps

|

| 2015 Kelly et al 21 UK |

To identify unanswered questions around the prevention, treatment, diagnosis and care of dementia, with the involvement of all stakeholders; to identify a top 10 prioritised list of uncertainties. |

|

Potential partner organisations were identified through the networks of the Alzheimer’s Society and the steering group, ensuring representation from all stakeholders. Patients, carers and clinicians were not involved in the steering group. | The Dementia PSP was guided and chaired by an independent JLA representative. | Six steps+NGT

|

| 2015 Stephens et al 22 UK |

To identify the top 10 research priorities relating to mesothelioma (pleural or peritoneal), specifically, to identify those unanswered questions that involved an intervention. |

|

Steering group comprised two patients, one bereaved carer, nine clinicians (including nurses, surgeons, oncologists, chest physicians and palliative care experts) and four representatives of patient and family support groups (one of the representatives was also a bereaved carer); in total, 16 participants. | The steering group was chaired by a JLA facilitator. | Eight steps

|

| 2016 Knight et al 23 UK |

To identify unanswered research questions in the field of kidney transplantation from end-service users (patients, carers and healthcare professionals). |

|

The steering group included transplant surgeons, nephrologists, transplant recipients, living donors and carers. Additional partner organisations were invited to take part in the process by involving their members in the surveys and helping to promote the process. National patient and professional organisations and charities involved in kidney transplantation were contacted about the project and were invited to contribute to a steering group. |

The steering group was chaired by an experienced advisor from the JLA. | Five steps+NGT

|

| 2016 Rangan et al 24 UK |

To run a UK-based JLA PSP for ‘surgery for common shoulder problems’ |

|

The steering group was made up of the most relevant stakeholders and included patients, physiotherapists, GPs, shoulder surgeons, anaesthetists and pain control experts, orthopaedic nurses and academic clinicians; national networks and interest organisations | A JLA adviser | Five steps

|

| 2016 van Middendorp et al 1 UK |

To identify a list of Top 10 priorities for future research into spinal cord injury. |

|

The steering group comprised representatives from each stakeholder organisation, including an independent information manager. Stakeholders included consumer organisations, clinician societies and carers representatives. | Support and guidance were provided by the JLA | Four steps 1. Gathering of research questions. 2. Checking of existing research evidence. 3. Interim prioritisation. 4. Final consensus meeting. |

| 2016, Wan et al 25 UK |

To establish a consensus regarding the top 10 unanswered research questions in endometrial cancer. |

|

As part of the JLA process, all organisations that could reach and advocate for patients, carers and clinicians were invited to become involved in a PSP. A steering group composed of representatives from these groups was then formed to ensure the study remained inclusive and fulfilled its aim to deliver and publicise a list of shared research priorities. A group of 23 stakeholders was constituted but was not described in detail. |

An independent advisor from the JLA was chair of the steering group | Six steps+NGT 1. Establishing a steering group. 2. Consultative process. 3. Gathering uncertainties. 4. Data analysis and verifying uncertainties. 5. Interim priority setting. 6. Final priority setting. |

| 2017, Britton et al 26 UK |

Facilitate balanced input in the priority setting process for Barrett’s oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and to reach a consensus on the Top 10 uncertainties in the field |

|

Professionals, patients and charity representatives formed a steering committee. The steering committee, which identified the broader priorities, The British Society of Gastroenterology, National Health Service, the University of Manchester, the Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons and the Primary Society for Gastroenterology. | NR. | Five steps+NGT 1. Initial survey. 2. Initial response list. 3. Long-list generation and verification. 4. Interim prioritisation survey. 5. Final workshop. |

| 2017, Fitzcharles et al 38 Canada |

Priorities of uncertainties for the management of fibromyalgia (FM) that could propel future research. |

|

The steering committee was composed of five patients (one patient was a practising pharmacist), five healthcare professionals (one family physician, two rheumatologists, one psychologist and one internist), an internist with previous experience of the JLA process but without specific interest in FM, and a rheumatologist. | Facilitators with experience of the JLA process | Five steps

|

| 2017, Hart et al 27 UK |

To devise a list of the key research priorities regarding treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, as seen by clinicians, patients and their support groups, using a structure established by the JLA. |

|

A steering committee was established following an initial explanatory meeting and included two patients, two gastroenterologists, two inflammatory bowel disease specialist nurses, two colorectal surgeons, two dietitians, a representative from the UK inflammatory bowel disease charity organisation Crohn’s and Colitis UK, a representative of the JLA and an administrator. | A JLA facilitator | Five steps 1. Initiation and setting up the committee. 2. Collection of treatment uncertainties. 3. Collation of treatment uncertainties. 4. Ranking of treatment uncertainties. 5. Development of a list of top 10 priorities. |

| 2017, Hemmelgarn et al 39 Canada |

To identify the most important unanswered questions (or uncertainties) about the management of CKD, that is, in terms of diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. |

|

The priority setting process with the formation of a 12-person steering group from across Canada, including patients with non-dialysis CKD, a carer, clinicians (nephrologists), researchers and an employee of the Kidney Foundation of Canada (non-profit organisation for patients with kidney disease). | Jointly organised PSP broadly adhering to the JLA Guidebook | Four steps+NGT

|

| 2017, Khan et al 40 Canada |

To identify the 10 most important research priorities of patients, carers and clinicians for hypertension management. |

|

Steering committee of 15 volunteer patients, carers and clinicians from across Canada. Stakeholder not reported in detail. |

JLA facilitator from the UK | Five steps

|

| 2017, Jones et al 41 Canada |

To identify unanswered questions encountered during management of kidney cancer agreement by consensus on a prioritised list of the top 10 shared unanswered questions and to establish corresponding research priorities. |

|

A 15-person steering group was formed with 7 patients/carers and 7 expert clinicians from across Canada. In response, the Kidney Cancer Research Network of Canada, in collaboration with the JLA, Kidney Cancer Canada, the Kidney Foundation of Canada, was formed | The group also included an advisor from the JLA (UK) who provided support and advice throughout the process. | Five steps

|

| 2017, Lomer et al 28 UK |

To provide a comprehensive summary of the research priority findings relating to diet in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease |

|

Steering committee comprising two patients, two gastroenterologists, two inflammatory bowel disease specialist nurses, two colorectal surgeons, two dietitians, a representative from the UK inflammatory bowel disease charity organisation, Crohn’s and Colitis UK, a representative of the JLA and an administrator (ie, 13-person steering committee). Stakeholders from various roles, ages and ethnic groups. |

A representative of the JLA and an administrator on the steering committee. | Five steps

|

| 2017, Macbeth et al 29 UK |

To identify uncertainties in alopecia areata management and treatment that are important to both service users, people with hair loss, carers/ relatives and clinicians. |

|

Four people representing various patient support groups, four dermatologists and two further individuals to represent the BHNS and the European Hair Research Society; an academic psychologist; a registered trichologist and a GP, and a JLA representative. Two separate steering groups. | A JLA representative provided independent oversight of the PSP and chaired the steering group. |

Five steps+NGT 1. Identification and invitation of potential partners. 2. Invitation to submit uncertainties. 3. Collation. 4. Ranking of treatment uncertainties. 5. Final workshop. |

| 2017, Narahari et al 44 India |

To summarise the process of lymphoedema PSP, discussion during the final prioritisation workshop and recommendation on the top seven priorities for future research in lymphoedema and a brief road map. |

|

The Faculty of Applied Dermatology and the Central University of Kerala participated in the coordinating committee | NR | Eight steps

|

| 2017 Prior et al UK |

To identify and prioritise important research questions for miscarriage. |

|

The steering group was a balanced composition of women charities that represented them and clinicians. Some members representing charities or clinicians also had personal experience of pregnancy loss. | The workshop was chaired by an independent JLA facilitator. | Six steps

|

| 2017 Rees et al 42 Canada |

Engaging patients and clinicians in establishing research priorities for gestational diabetes mellitus |

|

A steering committee consisting of three patients and three clinicians (one family physician who practises intrapartum care, an endocrinologist and a neonatologist); a facilitator familiar with the JLA process and a project manager. The Diabetes Obesity and Nutrition Strategic Clinical Network with the Alberta Health Services supported this research. Stakeholders were not reported. | A facilitator familiar with the JLA process | Four steps+NGT

|

| 2017 Smith et al 30 UK |

Prioritise research questions in emergency medicine in a consensus process to determine the Top 10 questions |

|

The steering group members were not reported with titles but consisted of 16 members. The Royal College of Emergency Medicine. |

NR. | Six steps

|

| 2018 Fernandez et al 31 UK |

To establish the research priorities for adults with fragility fractures of the lower limb and pelvis that represent the shared interests and priorities. |

|

The steering group consisted of patient representatives, healthcare professionals and carers with established links to relevant partner organisations to ensure that a range of stakeholder groups were represented. | A JLA adviser supported and guided the PSP | Five steps

|

| 2018 Finer et al 32 UK |

To describe processes and outcomes of a PSP and to identify the top 10 research priorities’ in type 2 diabetes. |

|

The steering group comprised five people living with type 2 diabetes (managing their condition in different ways), five clinicians (including a dietician, diabetes specialist nurse, GP and two consultant dialectologists), an information specialist, seven members of the Diabetes UK Research and the senior leadership team, and a JLA senior advisor. The steering group (47% men and 53% women and 26% from black and minority ethnic groups) met 12 times during the PSP process, in person or by teleconference. |

The workshop was facilitated by trained JLA advisors. | Four steps+NGT 1. Gathering uncertainties. 2. Organising the uncertainties. 3. Interim priority setting. 4. Final priority setting. |

| 2018 Lechelt et al 43 Canada |

To identify the top 10 treatment uncertainties in head and neck cancer from the joint perspective of patients, caregivers, family members and treating clinicians. |

|

The steering committee included five patients with head and neck cancer who were from 3 to 25 years since diagnosis; seven clinicians involved in the treatment and management of head and neck cancer (maxilla-facial prosthodontist, radiation oncologist, speech language pathologist clinician-researcher, infectious disease specialist, anaplastologist, and two head and neck oncological and reconstructive surgeons). However, a sixth individual (family member) was involved informally throughout the project, despite being unable to commit to regular participation. Alberta Cancer Foundation and the Institute for Reconstructive Sciences in Medicine | The workshop was led by an independent facilitator with extensive experience on JLA PSP projects, supported by two cofacilitators, all of whom were briefed by the JLA senior advisor on recommended JLA protocols. | Five steps+NGT

|

| 2018 Lough et al 33 UK |

To identify the shared priorities for future research of women affected by and clinicians involved with pessary use for the management of prolapse. |

|

The steering group comprised three women with pessary experience, three clinicians experienced in managing prolapse with pessaries, two researchers and a pessary company representative, the PSP with guidance from the JLA adviser and project leader. The JLA Pessary PSP was partially funded by a UK Continence Society research grant, two grants from the Pelvic Obstetric and Gynaecological Physiotherapy group of the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy and a funded studentship from Glasgow Caledonian University. | The steering group agreed on the terms of reference and protocol for the JLA adviser and project leader. | Four steps+NGT

|

| 2018 Macbeth et al 34 UK |

Identify uncertainties in hair loss management, prevention, diagnosis and treatment that are important to both people with hair loss and clinicians |

|

The steering group comprised four people representing various patient support groups, four dermatologists, a psychologist, a registered trichologist and a GP. A JLA representative ensured key stakeholders were identified through a process of consultation and peer knowledge, building on steering group members’ networks and existing JLA affiliates. | The process was facilitated by the JLA to ensure fairness, transparency and accountability. | Five steps+NGT

|

*User group means the participants who are involved in the PSP process, not only the survey.

†Age refers to age of patients who are involved in the survey.

‡Steering group, steering committee and coordinating committee are defined as equal concepts.

BHNS, British Hair and Nail Society; CKD, chronic kidney disease; GP, general practitioner; JLA, James Lind Alliance; NGT, nominal group technique; NR, not reported; PSP, priority setting partnership; UI, urinary incontinence.

Results

In total, 37 studies met the inclusion criteria; their characteristics are summarised in table 2.

The publication years ranged from 2010 to 2018. The number of studies using this process has increased annually, with 12 published in 2017. In our sample, 27 of the studies were from the UK,1 5 7 12–35 8 were from Canada,36–43 and 1 each was from India44 and Spain.45

The JLA process participants were patients, carers and clinicians aged ≥18 years. The studies collectively represented patient groups with heterogeneous ages and health conditions/diseases, with later studies generally more focused on symptoms and function than on diseases (table 2). Totally, 15 of the studies gave information about ethnicity.13 14 16 19 21 23 25–27 32 33 35 36 40 42 One of the studies also gave information about socioeconomic status.26 Another study gave only information about socioeconomic status.44

Three of studies described that patient and carers submitted more questions on psychosocial issues, psychosocial stress, depression and anxiety compered with clinicians.13 23 40 No studies described disagreement in the prioritisation stages. However, 24 other studies also mentioned psychosocial issues without noting who had done so.1 7 14–19 25–27 29 31–39 41–43 Ten studies did not mention psychosocial issues.5 12 20–22 24 26 28 44 45 The types of health conditions that were addressed included gastrointestinal,26–28 neurological,1 5 7 16 21 38 dermatological,13 15 17 29 34 45 endocrinal14 32 42 and cancer22 25 41 43 conditions.

Setting up a PSP

The JLA steering group is made up of key organisations and individuals who can collectively represent all or the majority of issues related to the PSP, either individually or through their networks.6

All included studies had a steering group, although they were described differently. Nineteen studies1 5 12 14–17 19 20 22 23 25 31 36 37 39–41 45 included patients, carers and clinicians in their steering groups; 16 studies7 13 18 24 26–29 32–35 38 42–44 did not include carers in their steering group (ie, only patients and clinicians). In one study,30 the titles of the members on the steering group were not reported; in another,21 the steering group did not specifically include patients, carers or clinicians, but rather stated that representation from all stakeholders was ensured.

The number of JLA steps in the PSP process varied across studies from four steps1 32 33 37 39 42 to eight steps.20 22 44 Five steps, corresponding to JLA Guidebook V.4, V.5 and V.6, were most common,12 13 15–19 23 24 26–29 31 34 36 38 40 41 43 45 with step 1, initiation; step 2, collection of uncertainties; step 3, collation of uncertainties; step 4, interim priority setting; and step 5, final priority workshop.

Gathering uncertainties

PSPs aimed to gather uncertainties from as wide a range of potential contributors as possible, ensuring that patients were equally confident and empowered compared with clinicians in submitting their perspectives on uncertainties.6

With regard to recruitment, various partner organisations, local advertisements, social media, patients, carers and clinicians were PSP information targets. In addition to an online and paper survey, two studies also used face-to-face methods to reach and facilitate involvement by their identified groups.5 42

The questions were usually deliberately open-ended to encourage full responses regarding the experiences of patients, carers and clinicians. One of the 37 studies44 used an online survey to collect uncertainties; patients and clinicians were invited via email to endorse their priorities based on a table that had been developed from abstracts collected in a literature search. Among the other 36 studies, 12 used open-ended questions1 15 18 23 25 32 35 40–43 45 such as ‘What questions about the management of hypertension or high blood pressure would you like to see answered by research?’ In seven studies, participants (patients, carers and clinicians) were asked to submit three to five research ideas.16 17 20 21 27 28 33 In eight studies, no limit was placed on the types of questions that could be submitted.5 13 24 30 31 36 37 39 One study asked about eight open-ended questions requesting a narrative answer.38 Close-ended questions were used in three studies,22 29 34 such as ‘Do you have questions about the prevention, diagnosis or treatment of hair loss that need to be answered by research?’ Five studies did not report their question format.7 12 14 19 26

The number of submitted uncertainties ranged from 8227, submitted by 2587 participants,32 to 323, submitted by 58 participants.45 All studies except two7 44 reported involving patients, carers and clinicians in the initial survey. Two of the studies addressed verifying uncertainties for example by content experts or librarians.40 43 The steering group or researchers were involved in addressing verifying uncertainties in 22 of the studies and5 7 14–16 18 20 21 23–27 30 31 33 35 37 39 41 44 45 in 13 of the studies not describing verifying the uncertainties.1 12 13 17 19 22 28 29 32 34 36 38 42

Data processing and verifying uncertainties

Unlike most surveys that are designed to collect answers, JLA PSP surveys are designed to collect questions. The survey responses must then be reviewed, sorted and turned into a list of ‘indicative’ questions, all of which are unanswered uncertainties.6

According to Lechelt et al,43 uncertainties are organised through coding, with natural clusters emerging. During this step, duplicates such as similar and related uncertainties are identified. Clinician–patient dyads consolidate and rephrase each cluster of related questions into a single indicative uncertainty, written in lay language using a standard format. Lomer et al 28 specified that similar uncertainties are combined to create indicative uncertainties. Among our included studies, 20 described refining questions into indicative uncertainties,5 13–15 17 19 20 23 24 27–29 31–34 38 39 42 43 while 17 did not describe a concept of indicative uncertainties.1 7 12 16 18 21 22 25 26 30 35–37 40 41 44 45

In total, 16 of the studies described directly ranking and assessing survey-generated uncertainties from a long list ranging from 43 to 226 uncertainties.1 5 13 14 19–21 23 24 26 27 30 38 41 43 44

The wording of the long list of uncertainties was reviewed by the steering group, and, in some cases, wording was altered to make the uncertainties more understandable and to explain complex words not generally well known to the public.1

Interim priority setting

Interim prioritisation is the stage at which the long list of uncertainties (indicative questions) is reduced to a short list for the final priority setting workshop.6

All studies described an interim stage, using the terms: interim priority setting14 32; interim prioritisation1 5 42; and ranking exercise.13 44

Their short lists varied from 2226 to 30 uncertainties.12 17–19 22 25 30 36 39 Sixteen of the studies used an interim prioritisation of their top 25 uncertainties that were taken to a final prioritisation workshop, where the participants agreed on their top 10 priorities.1 7 13 20 21 23 24 28 29 31 33–35 37 38 40 Three of the studies did not describe the number of shortlisted treatment uncertainties.15 27 44

To reduce the number of uncertainties, an interim prioritisation exercise was conducted by email or by post.5 18 32 Patients, carers and health professionals were initially invited to examine the long list18; 14 of the studies used a second online survey,1 19 20 23 25 28 29 31–35 38 40 and in one study, the steering group members facilitated an interim ranking exercise.39

Final priority setting

The JLA’s final stage is a rank ordering of the uncertainties, with a particular emphasis on the lists of top 10 priorities. For JLA PSPs, a final face-to-face priority setting workshop is conducted with both small group and whole group discussions. The NGT can be used by groups, with voting to ensure that all opinions are considered6; 21 of the studies reported using the NGT in the final priority setting workshop.5 12 16–19 21 23 25 26 29 32–34 36 37 39 41–43 45

All of the studies implemented a final priority setting workshop to agree on their top 10 priorities. In most of the studies, these final workshops included patients, carers and clinicians; nine studies mentioned including only patients and clinicians.7 23 28 29 33 34 42–44

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review of published studies using the JLA approach, although the number of steps used by PSPs differed and not all papers describe in detail every aspect of the JLA approach. However, overall they incorporated the same procedural content, which indicates no implications or small implications for our findings. Thus, this scoping review provides unique insight into a broad and varied range of perspectives on PPI using the JLA approach. Interestingly, there were some differences between the questions submitted by patients and carers compared with those submitted by clinicians. The patients focused more on symptoms and function than on disease, while clinicians focused on general treatment. Compared with clinicians, patients submitted more questions about psychosocial issues, psychosocial stress, depression and anxiety.13 23 40 There were no studies that described disagreement in the prioritisation steps. The health conditions addressed in these studies were primarily somatic diseases, although one study was about life after stroke and included mental health.5 Thus, the JLA approach is an appropriate and important method for defining research from the perspectives of end users that is, patients and carers.46

A key value that informs such partnerships is often described as equality. Equitable partnerships might be defined as a gradation of shared responsibility negotiated in a collaborative and cooperative decision-making environment. Whether such values always align within the JLA process is an open question. Thus, reflecting on and clarifying values about involvement before starting collaborative work might enhance the positive impacts while avoiding the negative impacts of public involvement.47

The number of priority setting exercises in health research is increasing,48 and our review indicates that the use of the JLA approach is also growing. This approach facilitates broad stakeholder involvement, and it is transparent and easy to replicate. This is consistent with findings by Yoshida,48 who argues that there is a clear need for transparent, replicable, systematic and structured approaches to research priority setting to assist policymakers and research funding agencies in making investments. Increased public involvement can lead to a wider range of identified and prioritised research topics that are more relevant to service users.49 A key strength of involving the public and patients, rather than only academics, throughout the partnership process is described in these studies, including having a project led by representatives of a wider range of consumer and clinician organisations.1 The number of resulting uncertainties reflects this breadth. The studies examined tended to conclude that the JLA principles were welcomed, but consistently emphasised the need for an even broader understanding, better conceptualisation and improved processes to incorporate the results into research. However, few studies focused on how to reach the weakest voices for survey participation. After critically reading these studies, one might ask whether they included the lowest socioeconomic groups and most vulnerable patients. Many respondents, particularly those associated with charity organisations, are likely to be white and middle class and to have high education attainment levels. Yet it is the individuals who are more difficult to reach, such as those in low socioeconomic groups and those who are vulnerable patients, who may have the greatest unmet needs and stand to gain the most from improved treatment.25 26 35 42 Given that the JLA is designed to identify shared research priorities, such individuals and their needs may not be reflected in what is typically reported studies. In one case, to better facilitate patient and carer involvement, and to reach those who may not receive and/or respond to email or postal information, a steering group member visited existing support groups and arranged the distribution of information leaflets at local meetings.5 Although great efforts were reportedly made25 to include participants from black and minority ethnic groups and care home populations, they were not particularly successful. Lough et al 33 reported that the use of an online survey may introduce a bias in favour of patients who use the internet and social media. It is also likely that those with literacy issues will not participate.16 Three of the studies5 18 42 attempted to facilitate participation among those with language barriers and literacy issues, which implies that efforts need to be made to enable minority groups and learning disabilities to participate in the PSP process. Stephens et al 22 note another major challenge to involving users in research and patients in the steering group who have incapacitating symptoms and short expected survival durations. Another important issue is that all but two studies44 45 were from English-speaking countries and thus represent a relatively limited global population.

According to the JLA Guidebook,6 PSPs usually report their process and methods, the participants involved, results, reflections on successes, lessons learnt or limitations, and the next steps. It is important that these reports be written in a language understandable to everyone with an interest in the topic, not just to clinicians. Lough et al 33 explained that all of the unanswered questions generated by their PSPs would be available on the JLA website and widely disseminated to research commissioners, public health and research funders. However, such reports can be difficult to obtain by those without ready online access or by those with literacy issues. Eleftheriadou et al 13 included implementation of a feasibility study as one of their top 10 priorities; the authors hoped that, following its publication, along with their list of the most important uncertainties, relevant studies would be developed.

Running a PSP and involving the relevant stakeholders in deciding which research should be funded seem to be an effective and sustainable model.24 Without doubt, the essential advantage is integration of this involvement in both research and healthcare. Identifying research priorities is perhaps where the PSP’s greatest effect can be achieved.26 Nevertheless, one might ask whether PSPs emphasise basic research less than applied research. Abma et al 50 have argued that the international literature describes corresponding challenges in research agenda setting and follow-up; patient involvement is limited to actual agenda setting, and there is limited understanding of what happens next and how to shape patient involvement activities in follow-up phases. This scoping review process gathered a large number of research priorities from a diverse set of respondents.32 34 There has been a clear paradigm shift from a reactive to a more proactive approach described as ‘predictive, personalised, preventative and participatory’.25 It is expected that the JLA process will have a clinical impact by driving relevant research studies based on PPI. Crowe et al 51 reported that a critical mismatch between the treatments that patients and clinicians want to have evaluated and the treatments actually being evaluated by researchers. This apparent mismatch should be taken into account in future research.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this paper is the application of a rigorous and robust scoping review method, including independent screening and data extraction. The search strategy was carefully performed in conjunction with a research librarian. To strengthen the review’s validity, several databases were used, and we have reported them with complete transparency. The studies selected for inclusion were manually searched. Although we searched multiple databases for the period since their inception, we may not have identified all relevant studies. We did not search the grey literature, assuming that empirical research using the JLA approach would be found in indexed databases. As a scoping review, the findings describe the nature of research using JLA’s approach and provide direction for future research; hence, this review cannot suggest how to operationalise the JLA process or how to use it in a given context. Another strength is that several of the researchers contributing to this project also work in the clinical areas represented in the studies. In addition, while a quality analysis was beyond the scope of this paper, we have noted varying descriptions within the selected studies (ie, sample sizes, health status and age of groups). Finally, the included studies do not provide information about the impact of involvement, regarding development of consensus, the discussions among all those who took part, the distribution of power and the politics. In future work, it may be important to evaluate how much influence patient/public partners had during the process, besides the impact of the number of participants in the respective groups. Another limitation might involve our inclusion criteria with respect to requirement for peer-reviewed publications, which by definition will use more academic language and may not be readily accessible to the layperson. Lastly, the cost and time involved in a PSP are described in one publication only.24 According to the JLA Guidebook, the PSP process will last approximately 12–18 months.6

Conclusions

JLA-based PSP makes a useful contribution to identifying research questions. A range from 327 to 8227 uncertainties were published, with 27 studies from UK. The number of reported steps varied from four to eight. In total, 33 studies mentioned the involvement of a JLA facilitator. Twenty-four included studies that addressed methods for verifying uncertainties, and the use of NGT was reported in 21 studies. Finally, it is important that the results of these studies, including the top 10 priorities, reach those who answered the survey, including the vulnerable groups. Online publishing might contribute to this. Future studies should focus on factors influencing patient and carer involvement in priority setting projects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank research librarian Malene Wøhlk Gundersen for her helpful and knowledgeable assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: AN, LH, SL, EKG and AB designed the study. AN coordinated the project and is the guarantor. AN, LH, SL, EKG and AB screened articles and performed data extraction. AN conducted the literature search. AN, LH, SL, EKG and AB interpreted the data. AN drafted the manuscript and all authors critically reviewed it. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway (grant number OFFPHD prnr 271870), Lørenskog Municipality and Oslo Metropolitan University. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

- 1. van Middendorp JJ, Allison HC, Ahuja S, et al. Top ten research priorities for spinal cord injury: the methodology and results of a British priority setting partnership. Spinal Cord 2016;54:341–6. 10.1038/sc.2015.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hanley B, Bradburn J, Barnes M, et al. Involving the public in NHS public health, and social care research: Briefing notes for researchers. UK: Involve 2004;2:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoddinott P, Pollock A, O'Cathain A, et al. How to incorporate patient and public perspectives into the design and conduct of research. F1000Res 2018;7 10.12688/f1000research.15162.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Price A, Albarqouni L, Kirkpatrick J, et al. Patient and public involvement in the design of clinical trials: an overview of systematic reviews. J Eval Clin Pract 2018;24:240–53. 10.1111/jep.12805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pollock A, St George B, Fenton M, et al. Top 10 research priorities relating to life after stroke – consensus from stroke survivors, caregivers, and health professionals. International Journal of Stroke 2014;9:313–20. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00942.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Institute for health research, the James Lind alliance Guidebook: version 7, 2018. Available: http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/jla-guidebook/downloads/Print-JLA-guidebook-version-7-March-2018.pdf

- 7. Hall DA, Mohamad N, Firkins L, et al. Identifying and prioritizing unmet research questions for people with tinnitus: the James Lind alliance tinnitus priority setting partnership. Clin Investig 2013;3:21–8. 10.4155/cli.12.129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:15 10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Institute for health research, the James Lind alliance Guidebook: version 6, 2016. Available: http://jla.nihr.ac.uk/jla-guidebook/downloads/JLA-Guidebook-Version-6-February-2016.pdf

- 10. Cowan K, Oliver S. The James Lind alliance Guidebook: version 5, 2013. Available: http://www.jlaguidebook.org/pdfguidebook/guidebook.pdf

- 11. Cowan K, Oliver S. James Lind alliance Guidebook: version 4, 2010. Available: http://www.bvsde.paho.org/texcom/cd045364/guidebook.pdf

- 12. Buckley BS, Grant AM, Tincello DG, et al. Prioritizing research: patients, carers, and clinicians working together to identify and prioritize important clinical uncertainties in urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2010;29:708–14. 10.1002/nau.20816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eleftheriadou V, Whitton ME, Gawkrodger DJ, et al. Future research into the treatment of vitiligo: where should our priorities lie? results of the vitiligo priority setting partnership. Br J Dermatol 2011;164:no–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10160.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gadsby R, Snow R, Daly AC, et al. Setting research priorities for Type 1 diabetes. Diabetic Medicine 2012;29:1321–6. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03755.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Batchelor JM, Ridd MJ, Clarke T, et al. The eczema priority setting partnership: a collaboration between patients, carers, clinicians and researchers to identify and prioritize important research questions for the treatment of eczema. Br J Dermatol 2013;168:577–82. 10.1111/bjd.12040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deane KHO, Flaherty H, Daley DJ, et al. Priority setting partnership to identify the top 10 research priorities for the management of Parkinson's disease. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006434 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ingram JR, Abbott R, Ghazavi M, et al. The hidradenitis suppurativa priority setting partnership. Br J Dermatol 2014;171:1422–7. 10.1111/bjd.13163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rowe F, Wormald R, Cable R, et al. The sight loss and vision priority setting partnership (SLV-PSP): overview and results of the research prioritisation survey process. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004905 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Uhm S, Crowe S, Dowling I, et al. The process and outcomes of setting research priorities about preterm birth — a collaborative partnership. Infant 2014;10:178–81. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boney O, Bell M, Bell N, et al. Identifying research priorities in anaesthesia and perioperative care: final report of the joint National Institute of academic Anaesthesia/James Lind alliance research priority setting partnership. BMJ Open 2015;5:e010006 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kelly S, Lafortune L, Hart N, et al. Dementia priority setting partnership with the James Lind alliance: using patient and public involvement and the evidence base to inform the research agenda. Age Ageing 2015;44:985–93. 10.1093/ageing/afv143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stephens RJ, Whiting C, Cowan K, et al. Research priorities in mesothelioma: a James Lind alliance priority setting partnership. Lung Cancer 2015;89:175–80. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Knight SR, Metcalfe L, O’Donoghue K, et al. Defining priorities for future research: results of the UK kidney transplant priority setting partnership. PLoS One 2016;11:e0162136 10.1371/journal.pone.0162136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rangan A, Upadhaya S, Regan S, et al. Research priorities for shoulder surgery: results of the 2015 James Lind alliance patient and clinician priority setting partnership. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010412 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wan YL, Beverley-Stevenson R, Carlisle D, et al. Working together to shape the endometrial cancer research agenda: the top ten unanswered research questions. Gynecol Oncol 2016;143:287–93. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.08.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Britton J, Gadeke L, Lovat L, et al. Research priority setting in Barrett's oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2:824–31. 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30250-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hart AL, Lomer M, Verjee A, et al. What are the top 10 research questions in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease? A priority setting partnership with the James Lind alliance. ECCOJC 2017;11:204–11. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lomer MC, Hart AL, Verjee A, et al. What are the dietary treatment research priorities for inflammatory bowel disease? a short report based on a priority setting partnership with the James Lind alliance. J Hum Nutr Diet 2017;30:709–13. 10.1111/jhn.12494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Macbeth AE, Tomlinson J, Messenger AG, et al. Establishing and prioritizing research questions for the treatment of alopecia areata: the alopecia areata priority setting partnership. Br J Dermatol 2017;176:1316–20. 10.1111/bjd.15099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith J, Keating L, Flowerdew L, et al. An emergency medicine research priority setting partnership to establish the top 10 research priorities in emergency medicine. Emerg Med J 2017;34:454–6. 10.1136/emermed-2017-206702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fernandez MA, Arnel L, Gould J, et al. Research priorities in fragility fractures of the lower limb and pelvis: a UK priority setting partnership with the James Lind alliance. BMJ Open 2018;8:e023301 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Finer S, Robb P, Cowan K, et al. Setting the top 10 research priorities to improve the health of people with type 2 diabetes: a diabetes UK-James Lind alliance priority setting partnership. Diabetic Medicine 2018;35:862–70. 10.1111/dme.13613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lough K, Hagen S, McClurg D, et al. Shared research priorities for pessary use in women with prolapse: results from a James Lind alliance priority setting partnership. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021276 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Macbeth A, Tomlinson J, Messenger A, et al. Establishing and prioritizing research questions for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of hair loss (excluding alopecia areata): the hair loss priority setting partnership. Br J Dermatol 2018;178:535–40. 10.1111/bjd.15810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Prior M, Bagness C, Brewin J, et al. Priorities for research in miscarriage: a priority setting partnership between people affected by miscarriage and professionals following the James Lind alliance methodology. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016571 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, Lillie E, et al. Setting research priorities for patients on or nearing dialysis. CJASN 2014;9:1813–21. 10.2215/CJN.01610214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barnieh L, Jun M, Laupacis A, et al. Determining research priorities through partnership with patients: an overview. Semin Dial 2015;28:141–6. 10.1111/sdi.12325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fitzcharles M-A, Brachaniec M, Cooper L, et al. A paradigm change to inform fibromyalgia research priorities by engaging patients and health care professionals. Canadian Journal of Pain 2017;1:137–47. 10.1080/24740527.2017.1374820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hemmelgarn BR, Pannu N, Ahmed SB, et al. Determining the research priorities for patients with chronic kidney disease not on dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017;32:847–54. 10.1093/ndt/gfw065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Khan N, Bacon SL, Khan S, et al. Hypertension management research priorities from patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers: a report from the hypertension Canada priority setting partnership group. J Clin Hypertens 2017;19:1063–9. 10.1111/jch.13091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jones J, Bhatt J, Avery J, et al. The kidney cancer research priority-setting partnership: identifying the top 10 research priorities as defined by patients, caregivers, and expert clinicians. Can Urol Assoc J 2017;11:379–87. 10.5489/cuaj.4590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rees SE, Chadha R, Donovan LE, et al. Engaging patients and clinicians in establishing research priorities for gestational diabetes mellitus. Canadian Journal of Diabetes 2017;41:156–63. 10.1016/j.jcjd.2016.08.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lechelt LA, Rieger JM, Cowan K, et al. Top 10 research priorities in head and neck cancer: results of an Alberta priority setting partnership of patients, caregivers, family members, and clinicians. Head Neck 2018;40:544–54. 10.1002/hed.24998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Narahari SR, Aggithaya M, Moffatt C, et al. Future research priorities for morbidity control of lymphedema. Indian J Dermatol 2017;62:33–40. 10.4103/0019-5154.198039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Davila-Seijo P, Hernández-Martín A, Morcillo-Makow E, et al. Prioritization of therapy uncertainties in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: where should research direct to? an example of priority setting partnership in very rare disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013;8:61 10.1186/1750-1172-8-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chalmers I, Ignorance CT. Confronting therapeutic ignorance. BMJ 2008;337:a841–7. 10.1136/bmj.39555.392627.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gradinger F, Britten N, Wyatt K, et al. Values associated with public involvement in health and social care research: a narrative review. Health Expectations 2015;18:661–75. 10.1111/hex.12158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yoshida S. Approaches, tools and methods used for setting priorities in health research in the 21st century. J Glob Health 2016;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Barber R, Boote JD, Parry GD, et al. Can the impact of public involvement on research be evaluated? a mixed methods study. Health Expectations 2012;15:229–41. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00660.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Abma TA, Pittens CACM, Visse M, et al. Patient involvement in research programming and implementation: a responsive evaluation of the dialogue model for research agenda setting. Health Expect 2015;18:2449–64. 10.1111/hex.12213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Crowe S, Fenton M, Hall M, et al. Patients', clinicians' and the research communities' priorities for treatment research: there is an important mismatch. Res Involv Engagem 2015;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.