Abstract

Objectives

To examine whether exposure to heavy physical work from early to later adulthood is associated with primary healthcare visits due to cause-specific musculoskeletal diseases in midlife.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Nationally representative Young Finns Study cohort, Finland.

Participants

1056 participants of the Young Finns Study cohort.

Exposure measure

Physical work exposure was surveyed in early (18–24 years old, 1986 or 1989) and later adulthood (2007 and 2011), and it was categorised as: ‘no exposure’, ‘early exposure only’, ‘later exposure only’ and ‘early and later exposure’.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Visits due to any musculoskeletal disease and separately due to spine disorders, and upper extremity disorders were followed up from national primary healthcare register from the date of the third survey in 2011 until 2014.

Results

Prevalence of any musculoskeletal disease during the follow-up was 20%, that for spine disorders 10% and that for upper extremity disorders 5%. Those with physically heavy work in early adulthood only had an increased risk of any musculoskeletal disease (risk ratio (RR) 1.55, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.28) after adjustment for age, sex, smoking, body mass index, physical activity and parental occupational class. Later exposure only was associated with visits due to any musculoskeletal disease (RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.12) and spine disorders (RR 2.40, 95% CI 1.41 to 4.06). Early and later exposure was associated with all three outcomes: RR 1.99 (95% CI 1.44 to 2.77) for any musculoskeletal disease, RR 2.43 (95% CI 1.42 to 4.14) for spine disorders and RR 3.97 (95% CI 1.86 to 8.46) for upper extremity disorders.

Conclusions

To reduce burden of musculoskeletal diseases, preventive actions to reduce exposure to or mitigate the consequences of physically heavy work throughout the work career are needed.

Keywords: musculoskeletal, physical work, spine disorder, upper extremity

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We used self-reported assessment of physical heaviness of work that was based on a single question, which is why the specificity of the exposure, for example, regarding exposure of different parts of the body, is low.

We cannot rule out the possibility of changes in the exposure or outcomes between the survey waves.

The setting enabled us to prospectively examine the long-term consequences of exposure to early and later physical work and midlife musculoskeletal health problems that were objectively measured.

The used cohort data were representative of the general population with relatively little loss to follow-up.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal diseases (MSD) are, along with mental disorders, the leading cause of work disability1 measured as sickness absence2 and disability retirements.3 In the European Union, the estimated total cost of lost productivity attributable to MSD among working-aged people can be up to 2% of gross domestic product.4 Contextual factors, particularly those related to workplace, have been identified as risk factors for sickness absence and disability retirement due to musculoskeletal problems5 6 as well as for musculoskeletal pain.7 We have reported findings where early and cumulative exposure to physical work was associated with low back pain at midlife.8 However, pain as an outcome is always self-reported, as well as a common condition. Thus, objective outcome measures are needed to confirm whether the effects of early and cumulative physical work are similar for more severe and objectively assessed MSD outcomes.

Only few studies to date have been able to assess the associations between cumulative exposure to physical work and MSD. A recent study used a job exposure matrix to assess exposure at the level of occupational title and disability retirement due to MSD,6 but even the first exposure measurements were mainly from midlife. In another study, two individual-level measurements were used to examine the associations between long-term exposure to high physical workload in midlife and risk of disability retirement due to MSD after age of 61,9 while younger employees were not included. Yet another study used individual-level physical work exposure data that were retrospectively assessed, and observed that cumulative exposure may increase the risk of sickness absence and disability retirement, but results for cause-specific outcomes were not reported.10 In addition to the lack of cumulative exposure data, prior studies have rarely accounted for family background although parental socioeconomic position has been linked, for example, to later musculoskeletal problems11 and widespread pain12 as well as career possibilities13 and choices.14

To fill these gaps in evidence, we examined whether physical heaviness of work from early adulthood to later adulthood is associated with primary healthcare visits due to MSD in midlife. We hypothesised that early, later and repeated exposure to heavy work is associated with later healthcare visits. Any MSD was examined as one outcome group, but we also included two cause-specific groups: disorders of the spine and upper extremities. The contribution of behavioural factors and parental socioeconomic position in these associations was considered.

Methods

Participants

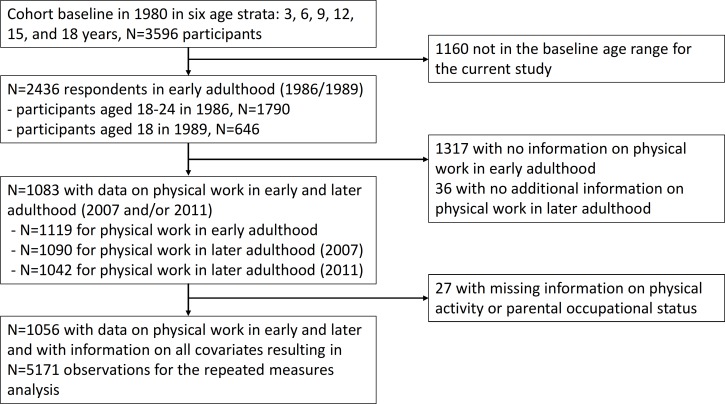

Data for this study are derived from the Young Finns Study.15 Cohort baseline data were collected in 1980 in six age strata: 3, 6, 9, 12, 15 and 18 years resulting in 3596 participants (response rate 83%). For this study, we included all those who were 18, 21 or 24 years when responding to the survey in 1986 (early adulthood). These data were completed by including also those who turned 18 years and responded to the survey in 1989 (figure 1). The age-based selection criterion was applied as the focus of this study was on early work-related exposures. Further inclusion criterion required that the participants responded to the question on physical heaviness of work in 1986 or 1989 (early adulthood exposure, n=1119), and in 2007 (later adulthood exposure, n=1090) and/or in 2011 (later adulthood exposure, n=1042), which resulted in a total of 10 83 participants. After excluding those with missing data on any covariate (after recoding and imputation), the final study sample was 1056 cohort participants (with 5171 observations) who all had work exposure measurement from early adulthood and at least one measurement from later adulthood.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the sample selection.

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients or the public were not involved in the development of the research question or the design of this study nor in the conduct of the study.

Exposure

Physical heaviness of work was enquired at waves 1–3 with a single question: ‘How heavy is your work physically?’ There were six response alternatives: (1) light sedentary work, (2) other sedentary work, (3) physically light work, involving standing and moving, (4) medium heavy work involving moving, (5) physically heavy work, and (6) physically very heavy work. The responses were categorised as: sedentary/physically light work, and medium to heavy physical work. We used responses from all three waves to form a five-class exposure variable categorised as: ‘no exposure’, when reporting sedentary/physically light work in all three waves, ‘early exposure only’, when reporting medium to heavy physical work only in wave 1, ‘later exposure only’, when reporting medium to heavy physical work in wave 2 or 3 (89% responded to both waves 2 and 3) and ‘early and later exposure’, when reporting medium to heavy physical work in wave 1 and in later adulthood in wave 2 and/or 3. All other possible response combinations formed a group ‘inconsistent exposure’.

Outcomes

We examined primary healthcare visits due to a musculoskeletal diagnosis. The follow-up started from the day after returning wave 3 survey in 2011. Repeated visits were used for the main analyses. For an alternative analysis, time to the first visit was used as an outcome, and the follow-up from returning the survey in 2011 continued until the first primary healthcare visit, death (from Statistics Finland) or end of the follow-up (end of 2014), whichever occurred first. Data were obtained from the register of primary healthcare visits (Avohilmo) maintained by the National Institute for Health and Welfare.16 Diagnosis-specific data have been collected and were available from 2011 onwards. Visits due to any musculoskeletal diagnosis by International Classification of Diseases (ICD) version 10 codes M00–M99 were examined over the follow-up period. Additionally, two cause-specific outcome groups with the largest numbers of events were: (1) disorders of the spine and (2) upper extremity disorders. Disorders of the spine included any of the following diseases, surgeries or treatments (ICD-10 code): cervical disc disorders (M50), lumbar and other intervertebral disc disorders with radiculopathy (M51.1), other specified intervertebral disc displacement (M51.2), disc degeneration (M51.3), disc disorders (M51.8), intervertebral disc disorder, unspecified (M51.9), disc disorder/disc disease (back disorders with radiation: M50, M51), other dorsopathies (M53), back pain/dorsalgia (back disorders without radiation: M54.1, M54.2, M54.3, M54.4, M54.5, M54.6, M54.8, M54.9) and lumbar disc herniation or sciatica (M51.1, M51.2, M54.3 and M54.4). Upper extremity disorders included any of the following diseases, surgeries or treatments: carpal tunnel syndrome, carpal tunnel release (G56.0, ACC51, ACC59), shoulder disorder (M75), medial epicondylitis, lateral epicondylitis and periarthritis of wrist (M77.0, M77.1, M77.2 or M77.3). Additionally, the numbers of visits due to osteoarthritis (M15, M16, M17, M18) were examined, but found to be too low for statistical analyses (see table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the study population at baseline

| Variable | All | |

| n | % | |

| Total individuals | 1065 | 100 |

| Women | 446 | 42 |

| Men | 610 | 58 |

| Parental occupational status | ||

| Upper non-manual | 152 | 14 |

| Lower non-manual | 447 | 42 |

| Upper manual | 282 | 27 |

| Lower manual | 175 | 17 |

| Ever smokers | 516 | 49 |

| Low physical activity index* | 710 | 67 |

| Cumulative exposure to heavy physical work | ||

| No exposure | 523 | 49 |

| Early exposure only | 124 | 13 |

| Later exposure only | 130 | 12 |

| Inconsistent exposure | 118 | 11 |

| Early and later exposure | 161 | 15 |

| Outcomes (−) | ||

| Any musculoskeletal disease | 221 | 21 |

| Disorders of the spine | 107 | 10 |

| Upper extremity disorders | 52 | 5 |

| Osteoarthritis | 16 | 1.5 |

*Index score 5–10.

Covariates

From the questionnaires we obtained information on possible confounders. We included sex and age at wave 1, and parental occupational status in childhood (1=upper non-manual, 2=lower non-manual, 3=upper manual, 4=lower manual). Smoking (ever smoker vs non-smoker) and body mass index (BMI, kg/m2 based on measured weight and height) were included as time-varying covariates collected at baseline, 2001, 2007 and 2011. Measure for leisure-time physical activity (PA) was based on a set of questions requesting the frequency and intensity of PA, frequency of vigorous PA, hours spent on vigorous PA, average duration of a PA session and participation in organised PA. Based on these questions a physical activity index was calculated (range 5–15, larger value indicating greater activity).17 For PA, we used the maximum of the three measurements of the PA index in adulthood (2001, 2007 and 2011), as these data had plenty of missing values (n missing=730 in 2001, 150 in 2007 and 475 in 2011), but the patterns of PA have been observed to remain constant in adulthood.18 Missing data on smoking were recoded as ‘non-smoker’. Number of missing observations varied by phase from 5 in 2007 to 369 in 1986, some of which were excluded due to missing data on other covariates. Missing data on BMI were imputed using mean of the study sample in the corresponding survey. Number of missing observations varied from 0 in 2001 to 411 in 1989, some of which were excluded due to missing data on other covariates. Although this is not the strongest imputation method we considered it was the most applicable one, as the method only concerned one covariate. All these covariates have been linked to back problems in prior studies11 19–21 and smoking can be also considered as an indicator of low socioeconomic position, which may affect the choice of employment and further physical workload.

Statistical analyses

We used generalised estimating equation (GEE) models with Poisson distribution to assess associations between the five-class physical work exposure, ‘no exposure’ serving as the reference group, and repeated primary healthcare visits due to MSD. This method was chosen as the GEE models permit specification of a working correlation matrix that accounts for the form of within-subject correlation of responses on dependent variables of many different distributions, including Poisson.22 We ran models separately for all musculoskeletal visits, for disorders of the spine and for upper extremity disorders. Two model specifications were used: model 1 was adjusted for sex and age at baseline, model 2 was additionally adjusted for parental occupational class, PA, and time-varying smoking and BMI. Results are presented as risk ratios (RR) with 95% CIs. As an alternative method, we ran the analyses using Cox proportional hazards models using time to the first visit as the outcome, which resulted in very similar findings (online supplementary table 1).

bmjopen-2019-031564supp001.pdf (45.6KB, pdf)

Results

Descriptive statistics of the analysis sample in total and by sex are shown in table 1. At baseline, mean age was 20.5 (SD=2.9) years, and mean BMI 22.4 (SD=2.3), while the mean BMI during the follow-up was 25.5 (SD=4.8). Mean follow-up time for first visits due to any MSD was 3.2 (SD=0.87) years, due to spine disorders 3.4 (SD=0.63) years and due to upper extremity disorders 3.4 (SD=0.50) years. In the total sample, prevalence of any MSD during the follow-up was 20%, that for spine disorders 10% and that for upper extremity disorders 5%. Distributions of the outcomes and proportions of events in each of the five exposure groups in total and by sex are presented in table 2. As shown in table 2, the low numbers of events prevented sex-specific analyses.

Table 2.

Number of observations and proportions (%) of primary healthcare visits due to musculoskeletal diseases by the exposure categories for physical heaviness of work between 2011 and 2014

| Physical heaviness of work | Any musculoskeletal disease nobs (%) |

Disorders of the spine nobs (%) |

Upper extremity disorders nobs (%) |

Osteoarthritis nobs (%) |

| All | 1083 | 527 | 253 | 79 |

| No exposure | 405 (37) | 168 (32) | 66 (26) | 44 (56) |

| Early exposure | 137 (13) | 64 (12) | 34 (13) | 20 (25) |

| Later exposure | 156 (14) | 102 (19) | 40 (16) | 5 (6) |

| Inconsistent exposure | 168 (16) | 85 (16) | 34 (13) | 10 (13) |

| Early and later exposure | 217 (20) | 108 (21) | 79 (31) | 0 (0) |

| Women | 730 | 353 | 165 | 59 |

| No exposure | 334 (46) | 148 (42) | 47 (28) | 35 (58) |

| Early exposure | 58 (8) | 29 (8) | 14 (8) | 15 (25) |

| Later exposure | 107 (15) | 63 (18) | 30 (18) | 5 (8) |

| Inconsistent exposure | 128 (18) | 55 (16) | 34 (21) | 5 (8) |

| Early and later exposure | 103 (14) | 58 (16) | 40 (24) | 0 (0) |

| Men | 353 | 174 | 88 | 20 |

| No exposure | 71 (20) | 20 (11) | 19 (22) | 10 (50) |

| Early exposure | 79 (22) | 35 (20) | 20 (23) | 5 (25) |

| Later exposure | 49 (14) | 39 (23) | 10 (11) | 0 (0) |

| Inconsistent exposure | 40 (11) | 30 (17) | 0 (0) | 5 (25) |

| Early and later exposure | 115 (32) | 50 (29) | 39 (44) | 0 (0) |

Associations between physical heaviness of work and primary healthcare visits due to the three outcome groups are presented in table 3. Overall, the age and sex-adjusted estimates (model 1) were slightly attenuated after including parental occupational status smoking, BMI and PA (model 2). We observed an association between early exposure only and any musculoskeletal disorders (fully adjusted RR 1.55, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.28) and a slightly weaker association for later exposure only (RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.12). Early and later exposure had the strongest association with any visits due to MSD (RR 1.99, 95% CI 1.44 to 2.77).

Table 3.

Risk ratios for primary healthcare visits due to musculoskeletal diseases in relation to early and later exposure to heavy physical work

| Physical heaviness of work | Model 1* | Model 2† | ||

| RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | |

| Any musculoskeletal disease | ||||

| No exposure | 1 | 1 | ||

| Early exposure | 1.65 | 1.12 to 2.41 | 1.55 | 1.05 to 2.28 |

| Later exposure | 1.57 | 1.09 to 2.24 | 1.46 | 1.01 to 2.12 |

| Inconsistent exposure | 1.90 | 1.35 to 2.67 | 1.87 | 1.34 to 2.61 |

| Early and later exposure | 2.14 | 1.55 to 2.97 | 1.99 | 1.44 to 2.77 |

| Disorders of the spine | ||||

| No exposure | 1 | 1 | ||

| Early exposure | 1.87 | 1.02 to 3.42 | 1.76 | 0.96 to 3.22 |

| Later exposure | 2.51 | 1.51 to 4.18 | 2.40 | 1.41 to 4.06 |

| Inconsistent exposure | 2.32 | 1.35 to 3.99 | 2.30 | 1.34 to 3.95 |

| Early and later exposure | 2.62 | 1.56 to 4.40 | 2.43 | 1.42 to 4.14 |

| Upper extremity disorders | ||||

| No exposure | 1 | 1 | ||

| Early exposure | 2.50 | 1.03 to 2.16 | 2.16 | 0.87 to 5.37 |

| Later exposure | 2.33 | 1.00 to 2.02 | 2.02 | 0.85 to 4.85 |

| Inconsistent exposure | 2.33 | 0.96 to 2.26 | 2.26 | 0.94 to 5.43 |

| Early and later exposure | 4.79 | 2.28 to 3.97 | 3.97 | 1.86 to 8.46 |

*Model 1 adjusted for age and sex.

†Model 2 adjusted for age, sex, smoking, body mass index (BMI), physical activity and parental occupational class.

RR, risk ratio.

For disorders of the spine, we observed an association for later exposure only (RR 2.40, 95% CI 1.41 to 4.06), inconsistent exposure (RR 2.30, 95% CI 1.34 to 3.95) and early and later exposure (RR 2.43, 95% CI 1.42 to 4.14). Effect estimates for visits due to upper extremity disorders were also positive, that for early and later exposure (HR 3.97, 95% CI 1.86 to 8.46) reaching statistical significance, although with a wide CI.

Discussion

In this study, reporting both early and later exposure to heavy physical work was associated with objectively measured MSDs requiring primary healthcare visit in midlife. In addition, physical heaviness of work in early adulthood only was associated with an increased risk of primary healthcare visit due to any MSD, and exposure in later adulthood only was associated with any MSD and disorders of the spine. These diagnosis-specific findings are in line with our prior findings for self-reported low back pain.8 Although our current analyses may have lacked power to detect precise associations, particularly for upper extremity disorders, the findings suggest that physical work exposure is also a predictor of objectively measured MSDs even after considering behavioural factors and parental socioeconomic position.

Longitudinal studies on the associations between physical work exposures and objectively measured MSDs are scarce. Specifically, we are not aware of studies that would have collected and used data on work-related physical exposures of participants from early to later adulthood, and healthcare visits due to MSDs in midlife. Some evidence exists regarding physical work exposures and musculoskeletal pain or disorders at an early stage of the working career. In one cross-sectional study repetitive and asymmetric demands, including high probability of repetitive tasks, bending or rotation movements and manual materials handling, were associated with the presence of neck/shoulder pain and severity of upper and lower back pains among 21-year-old employees.23 Another cross-sectional study among less than 30-year-old employees reported similar results regarding the association between physical work exposures (eg, repetitive flexion or rotation movements of the trunk, and more than 3 years in a job including lifting more than 25 kg at least once an hour) and low back pain.24 However, in these studies follow-up for midlife musculoskeletal disorders was not available. Timing of outcome measurement seems essential as it is likely that there are differences in associations between physical work and MSD among 20–35, 36–49 and over 50-year-old employees.25

Several studies have reported associations between physical work exposures and increased risk of objectively measured disability retirement due to MSD.5 26–28 However, only one of these studies examined how exposure in early adulthood was associated with disability retirement due to MSD in midlife.28 Moreover, only a few studies have reported associations between cumulative exposure to physical work throughout the work career and objectively measured sickness absence or disability retirement in general,29 or due to disability retirement due to MSD in particular.6 These findings have been in line with ours, although the cumulative exposure in the study focusing on MSD was assessed using a job exposure matrix.

Some limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. We used self-reported assessment of physical heaviness of work that was based on a single question. Consequently, the specificity of the exposure, for example, regarding exposure of different parts of the body, is low. Although such questions have widely been used in epidemiological studies and have indicated good validity,30 this may partly explain the non-significant associations between physical work and upper extremity disorders. We also used a dichotomised physical heaviness of work measure where medium and heavy/very heavy work were combined as the proportion of those with heavy/very heavy work was rather low (10% at early adulthood). The used cut-off may have attenuated the observed associations if medium heavy work had substantially weaker association with healthcare visits than heavy/very heavy work. We cannot rule out the possibility of changes in the exposure or outcomes between the survey waves, which may have caused underestimation or overestimation of the associations. However, the long follow-up enabled us to examine the long-term consequences of early and later physical work and midlife musculoskeletal health problems that were objectively measured. Some healthy worker effect may have attenuated the findings as we required minimum of two responses (from early and later adulthood) regarding physical heaviness of work and those with physically strenuous work or with musculoskeletal problems may have left employment before the second survey. It can also be speculated that primary healthcare visits with musculoskeletal diagnosis in midlife are mostly a result of pain complaints. Severe pain may interfere with work activities and induce need for sickness absence, which may be the primary motivation for the visit to a physician. Thus, the used outcomes may reflect the severity of work disability due to a subjective measure of musculoskeletal pain. The follow-up period for the outcomes was not very long and unobserved changes in the exposure or covariates during the outcome follow-up could have caused some bias to the findings resulting in underestimation or overestimation of the observed associations. However, the major strength of this work is the prospective study design with three repeated assessments of physical heaviness of work that were initiated in early adulthood. Moreover, the used cohort data were representative of the general population with relatively little loss to follow-up.15 As we used register data, only persons who emigrate will no more have registered healthcare visits. This suggests good generalisability to the Finnish working population, while more caution is needed when assessing generalisability to other countries with different healthcare systems.

In summary, our findings suggest that exposure to heavy physical work over the work career contributes to the high burden in the healthcare. Therefore, preventive actions against musculoskeletal problems due to physically heavy work in early adulthood, later adulthood and cumulatively throughout the work career are needed. One possible action, specifically among young employees, might be good introduction to ergonomic ways to work. Guidance on how to recover from physical work tasks is also important; for example, at individual level recovery training has been seen beneficial to the employees.31 At organisational level, procedures enabling recovery during the workday could include task variation and convenient work-break schedules,31 which are likely to be applicable throughout the work career.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the statistician Niina Kartiosuo for her help with the formation of the analysis data set.

Footnotes

Twitter: @FIOH

Contributors: JIH, RS, MM, HS, EVJ, SS and TLa conceived and designed the experiments. TLa analysed the data. JIH wrote the first draft of the article. MK, TLe and OR contributed materials and/or analysis tools. TLa, MK, TLe and OTR contributed to the funding of the study. TLa is the guarantor of the study. All authors were involved in interpretation of the findings, writing the paper and approved the submitted and published versions.

Funding: The research was funded by the Finnish Academy (grant numbers 287488 and 319200 for TLa and JIH). The Young Finns Study has been financially supported by the Academy of Finland: grants 286284, 134309 (Eye), 126925, 121584, 124282, 129364, 129378 (Salve), 117787 (Gendi) and 41071 (Skidi); the Social Insurance Institution of Finland; Competitive State Research Financing of the Expert Responsibility area of Kuopio, Tampere and Turku University Hospitals (grant X51001); Juho Vainio Foundation; Paavo Nurmi Foundation; Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research; Finnish Cultural Foundation; the Sigrid Juselius Foundation; Tampere Tuberculosis Foundation; Emil Aaltonen Foundation; Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation; Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation; Diabetes Research Foundation of Finnish Diabetes Association; and EU Horizon 2020 (grant 755320 for TAXINOMISIS); and European Research Council (grant 742927 for MULTIEPIGEN project); Tampere University Hospital Supporting Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study has received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland on 21 September 2010.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. OECD Sickness, disability and work: breaking the barriers. A synthesis of findings across OECD countries OECD publishing. Paris, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Linaker C, Harris EC, Cooper C, et al. The burden of sickness absence from musculoskeletal causes in Great Britain. Occup Med 2011;61:458–64. 10.1093/occmed/kqr061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Statistics Finland Recipients of disability pension, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bevan S. Economic impact of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) on work in Europe. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2015;29:356–73. 10.1016/j.berh.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foss L, Gravseth HM, Kristensen P, et al. The impact of workplace risk factors on long-term musculoskeletal sickness absence: a registry-based 5-year follow-up from the Oslo health study. J Occup Environ Med 2011;53:1478–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ervasti J, Pietilainen O, Rahkonen O, et al. Long-Term exposure to heavy physical work, disability pension due to musculoskeletal disorders and all-cause mortality: 20-year follow-up-introducing Helsinki health study job exposure matrix. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Madsen IEH, Gupta N, Budtz-Jørgensen E, et al. Physical work demands and psychosocial working conditions as predictors of musculoskeletal pain: a cohort study comparing self-reported and job exposure matrix measurements. Occup Environ Med 2018;75:752–8. 10.1136/oemed-2018-105151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lallukka T, Viikari-Juntura E, Viikari J, et al. Early work-related physical exposures and low back pain in midlife: the cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Occup Environ Med 2017;74:163–8. 10.1136/oemed-2016-103727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kjellberg K, Lundin A, Falkstedt D, et al. Long-Term physical workload in middle age and disability pension in men and women: a follow-up study of Swedish cohorts. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2016;89:1239–50. 10.1007/s00420-016-1156-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sundstrup E, Hansen Åse Marie, Mortensen EL, et al. Retrospectively assessed physical work environment during working life and risk of sickness absence and labour market exit among older workers. Occup Environ Med 2018;75:114–23. 10.1136/oemed-2016-104279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lallukka T, Viikari-Juntura E, Raitakari OT, et al. Childhood and adult socio-economic position and social mobility as determinants of low back pain outcomes. EJP 2014;18:128–38. 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00351.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Power C, Atherton K, Strachan DP, et al. Life-Course influences on health in British adults: effects of socio-economic position in childhood and adulthood. Int J Epidemiol 2007;36:532–9. 10.1093/ije/dyl310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Laukkonen M-L. Pienituloisten perheiden ylioppilaat välttävät riskiä pääsykokeita painottavissa opiskelijavalinnoissa [High school graduates from low income families evade risk related to student admission emphasizing entrance examinations]. ETLA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Whiston SC, Keller BK. The influences of the family of origin on career development: a review and analysis. The Counceling Psychologist 2004;32:493–568. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Raitakari OT, Juonala M, Rönnemaa T, et al. Cohort profile: the cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:1220–6. 10.1093/ije/dym225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Institute for Health and Welfare Register of primary health care visits. Helsinki: National Institute for Health and Welfare, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rovio SP, Yang X, Kankaanpää A, et al. Longitudinal physical activity trajectories from childhood to adulthood and their determinants: the young Finns study. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2018;28:1073–83. 10.1111/sms.12988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Telama R, Yang X, Leskinen E, et al. Tracking of physical activity from early childhood through youth into adulthood. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2014;46:955–62. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shiri R, Karppinen J, Leino-Arjas P, et al. The association between smoking and low back pain: a meta-analysis. Am J Med 2010;123:87.e7–35. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shiri R, Karppinen J, Leino-Arjas P, et al. The association between obesity and low back pain: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2010;171:135–54. 10.1093/aje/kwp356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shiri R, Euro U, Heliövaara M, et al. Lifestyle risk factors increase the risk of hospitalization for sciatica: findings of four prospective cohort studies. Am J Med 2017;130:1408–14. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ballinger GA. Using generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data analysis. Organizational Research Methods 2004;7:127–50. 10.1177/1094428104263672 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lourenço S, Araújo F, Severo M, et al. Patterns of biomechanical demands are associated with musculoskeletal pain in the beginning of professional life: a population-based study. Scand J Work Environ Health 2015;41:234–46. 10.5271/sjweh.3493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van Nieuwenhuyse A. Risk factors for first-ever low back pain among workers in their first employment. Occup Med 2004;54:513–9. 10.1093/occmed/kqh091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oakman J, Neupane S, Nygård C-H. Does age matter in predicting musculoskeletal disorder risk? An analysis of workplace predictors over 4 years. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2016;89:1127–36. 10.1007/s00420-016-1149-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lahelma E, Laaksonen M, Lallukka T, et al. Working conditions as risk factors for disability retirement: a longitudinal register linkage study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:309 10.1186/1471-2458-12-309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Robroek SJW, Järvholm B, van der Beek AJ, et al. Influence of obesity and physical workload on disability benefits among construction workers followed up for 37 years. Occup Environ Med 2017;74:621–7. 10.1136/oemed-2016-104059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ropponen A, Svedberg P, Koskenvuo M, et al. Physical work load and psychological stress of daily activities as predictors of disability pension due to musculoskeletal disorders. Scand J Public Health 2014;42:370–6. 10.1177/1403494814525005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sundstrup E, Hansen Ã…se Marie, Mortensen EL, et al. Cumulative occupational mechanical exposures during working life and risk of sickness absence and disability pension: prospective cohort study. Scand J Work Environ Health 2017;43:415–25. 10.5271/sjweh.3663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stock SR, Fernandes R, Delisle A, et al. Reproducibility and validity of workers’ self-reports of physical work demands. Scand J Work Environ Health 2005;31:409–37. 10.5271/sjweh.947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Verbeek J, Ruotsalainen J, Laitinen J, et al. Interventions to enhance recovery in healthy workers; a scoping review. Occup Med 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031564supp001.pdf (45.6KB, pdf)