Abstract

Objectives

Despite the publication of hundreds of trials on gout and hyperuricemia, management of these conditions remains suboptimal. We aimed to assess the quality and consistency of guidance documents for gout and hyperuricemia.

Design

Systematic review and quality assessment using the appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation (AGREE) II methodology.

Data sources

PubMed and EMBASE (27 October 2016), two Chinese academic databases, eight guideline databases, and Google and Google scholar (July 2017).

Eligibility criteria

We included the latest version of international and national/regional clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements for diagnosis and/or treatment of hyperuricemia and gout, published in English or Chinese.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two reviewers independently screened searched items and extracted data. Four reviewers independently scored documents using AGREE II. Recommendations from all documents were tabulated and visualised in a coloured grid.

Results

Twenty-four guidance documents (16 clinical practice guidelines and 8 consensus statements) published between 2003 and 2017 were included. Included documents performed well in the domains of scope and purpose (median 85.4%, range 66.7%–100.0%) and clarity of presentation (median 79.2%, range 48.6%–98.6%), but unsatisfactory in applicability (median 10.9%, range 0.0%–66.7%) and editorial independence (median 28.1%, range 0.0%–83.3%). The 2017 British Society of Rheumatology guideline received the highest scores. Recommendations were concordant on the target serum uric acid level for long-term control, on some indications for urate-lowering therapy (ULT), and on the first-line drugs for ULT and for acute attack. Substantially inconsistent recommendations were provided for many items, especially for the timing of initiation of ULT and for treatment for asymptomatic hyperuricemia.

Conclusions

Methodological quality needs improvement in guidance documents on gout and hyperuricemia. Evidence for certain clinical questions is lacking, despite numerous trials in this field. Promoting standard guidance development methods and synthesising high-quality clinical evidence are potential approaches to reduce recommendation inconsistencies.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42016046104.

Keywords: clinical practice guideline, hyperuricemia, gout, systematic review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The first systematic review to assess the quality of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements on the diagnosis and treatment for both hyperuricemia and gout.

The first systematic review to summarise recommendations for best practice in hyperuricemia and gout.

The appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation II instrument is an international, structured, validated and rigorously developed tool.

Only guidance documents in English and Chinese were included.

Literature search was >1 year old at the time of publication.

Background

Gout is an inflammatory arthritis occurring in response to monosodium urate (MSU) crystals formation, a common and necessary pathogenic factor of which is hyperuricemia. The prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia,1–4 as well as their disease burden,5 6 are rising globally. However, although >600 related clinical studies7 have been published to date, the quality of care for gout and hyperuricemia remains suboptimal. The goal of treatment is to reduce the body’s total uric acid pool8 9 and consequently to minimise the risk of acute flares, arthropathy, nephrolithiasis and other complications.7 10 11 A study in the USA found that only 22% of patients with gout received therapy adhering to all quality indicators.12 A nationwide population study in the UK reported that only 48% of prevalent patients received proper consultation and only 27% of incident patients were provided with urate-lowering therapy (ULT) within 1 year of diagnosis.6

High-quality guidance documents are important for improving the quality of care for gout and hyperuricemia at individual, community and national levels.13 Current guidance documents for gout and hyperuricemia have been developed by rheumatology, endocrinology and cardiology groups, at regional, national or international levels. Among these documents, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines,14 15 updated in 2012, and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) guidelines,16–18 updated in 2016, have the most substantial global influence. Besides, the most recent documents (released in 2017) are two national guidelines, from the American College of Physicians (ACP)19 20 and the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR),21 respectively, and one consensus statement, from the Chinese Multidisciplinary Expert Task Force on Hyperuricemia and Its Related Diseases.22

Despite the variety of documents, current guidelines and consensuses on gout and hyperuricemia provide inconsistent recommendations, even those released by highly respected professional organisations, such as the ACP and the ACR.23 Some distinct differences lie in key aspects for patient care, such as the pharmacological treatment for asymptomatic hyperuricemic patients, the timing of initiation of ULT in patients with gout flare24 and indications for ULT.25 These discrepancies may result from ethnic and social differences, but can be a consequence of inconsistent guideline development.23 Low-quality guidance documents put individual patients and communities at risk, and impede the application of guideline recommendations in clinical practice.26 Hence, we conducted this study to systematically evaluate the quality of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements on gout and hyperuricemia and to compare key recommendations on patient care from all included documents.

Methods

Detailed methods of the study have been published previously27 and this study was registered with PROSPERO.

Literature search and selection criteria

We systematically searched PubMed and EMBASE from inception to 27 October 2016 using a comprehensive search strategy (online supplementary tables 1 and 2) to identify guidelines and consensus recommendations pertaining to the diagnosis and treatment of gout and hyperuricemia. We searched two academic databases for Chinese publications (the Chinese Biomedical Literature Database and the Wanfang Data) and eight guideline databases from inception to 24 July 2017 using search strategies tailored to different databases (online supplementary table 3). We also searched Google and Google scholar in July 2017 for potentially eligible guidelines and consensus recommendations that were not indexed in the aforementioned databases.

bmjopen-2018-026677supp001.pdf (582.6KB, pdf)

We included the latest versions of all international and national/regional clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements for the diagnosis and/or treatment of gout and hyperuricemia, published in English or Chinese. Two reviewers (QL, XL) independently screened all searched documents. Reasons for exclusion were provided for documents excluded during the full-text review (online supplementary table 4). Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (SL).

Data extraction

We extracted the following data from each included document: document characteristics (eg, year of publication, funding body and evidence base), recommendations for diagnosis and monitoring of gout and hyperuricemia, and recommendations for management. Data were extracted by one investigator (QL) and checked by another (XL).

Appraisal of guidance documents

All included documents were assessed by four reviewers (QL, XL, JW and HL) independently using the appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation (AGREE) II instrument.28 AGREE II is an internationally developed and validated tool to evaluate the quality of clinical practice guidelines29–31 and consensus statements.32 33

All reviewers completed an online training tutorial34 before the commencement of appraisal to ensure standardisation. We adapted detailed instructions for scoring from the AGREE II User’s Manual28 and provided objective scoring criteria for each item (online supplementary file 1). We selected four guidance documents for pilot scoring, during which we discussed and clarified our objective scoring criteria. When scoring for all included documents was completed, a meeting was held among reviewers and every item with scores differed more than one point was discussed. After the meeting, reviewers were given the opportunity to revise their scores or to keep the original scores. We recorded all original scores, revised scores and reasons for modifying scores for quality control purpose, and used the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) to test inter-rater reliability. The ICC was calculated via IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 and an ICC ≥0.7 was considered acceptable.35

Recommendation synthesis

We manually extracted recommendations on key clinical questions from all included guidance documents and summarised them into four tables: (1) the diagnosis of gout and hyperuricemia, (2) the treatment of hyperuricemia, (3) the treatment of acute gout and (4) the treatment of tophi. Recommendations were extracted by one investigator (QL) and checked by another (XL). We further visualised these recommendations in a five-colour grid to illustrate inconsistencies. The most frequently recommended content was used as a reference. We used green to colour documents providing consistent recommendations, red to colour those providing contrary recommendations and blue to colour those providing partially consistent recommendations. A partially consistent recommendation was defined as a recommendation that included but not the same as the reference content. Where recommendations were not given or were not applicable, the cell was coloured in yellow and in grey, respectively.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the conceptualisation or carrying out of this research.

Results

Search results

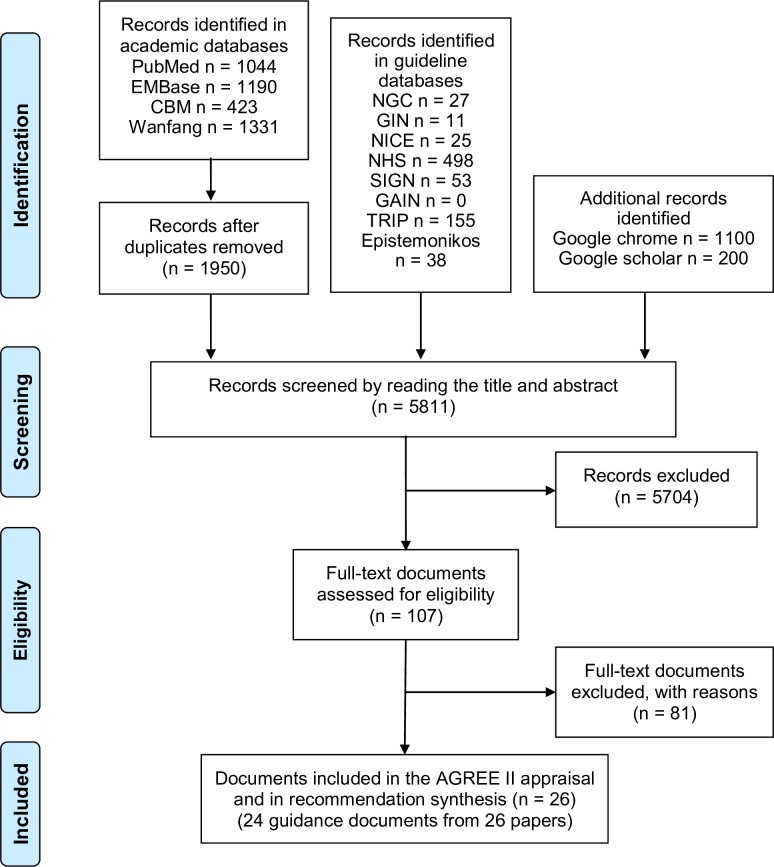

Overall, we identified 5811 items across academic databases, guideline databases, Google and Google Scholar. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 24 guidance documents from 26 papers14–22 36–52 were included in the final appraisal and recommendation synthesis (figure 1). Studies excluded after full-text review and reasons for exclusion were provided as online supplementary table 4.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for literature search. AGREE, appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation; CBM, Chinese Biomedical Literature Database; GAIN, Guidelines and Audit Implementation Network; GIN, Guidelines InternationalNetwork; NGC, National Guideline Clearinghouse; NHS, National Health Service; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; TRIP, Turning Research into Practice Database

Characteristics of included guidelines and consensus statements

Table 1 summarised characteristics of included guidance documents, among which 16 were clinical practice guidelines14–21 38 41 44–46 48–52 and 8 were consensus statements.22 36 37 39 40 42 43 47 16 national or regional organisations and three international groups (ie, the 3e (evidence, expertise, exchange) Initiative, the EULAR and the development group for the treat-to-target (T2T) recommendations) published these documents between 2003 and 2017. Sixteen documents14–18 21 22 36–38 40 42 43 45 46 49 50 were issued by rheumatology organisations and seven16–18 36 39 42 43 were developed by multinational development groups. Seventeen documents14–18 21 22 36 38–41 43–46 49 51 provided information on their guideline development group, among which 1114–17 19–21 36 41–43 45 46 explicitly stated the involvement of a methodologist. Twelve documents14–18 21 22 38–41 43–46 49 51 provided information on their target audience, among which only three16 38 44 considered patients as one of the target audiences. Eighteen documents14–21 36 39–43 45 46 48–52 conducted systematic literature review as part of their development process, among which 17 documents14–21 36 39–41 43 45 46 48–52 reported the level of evidence supporting recommendations and 1616–21 36 39–41 43 45 46 48–52 graded the strength of recommendations. Ten documents16 19–21 39 42 46 48 49 51 52 clearly stated being externally reviewed. Five19–21 46 49 50 provided a clear time of update plan. Twelve documents14 15 17–21 36 39 42 46 49 51 52 provided information on their funding body, among which six17 36 39 46 49 51 were fully or partially funded by the pharmaceutical industry and the rest did not clearly declare their funding body.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included guidelines and consensus statements

| Document | Issuing organisation | Year of publication | Country | Funding body | Target population | Target audience | Guideline development group | Guideline review | Guideline update | Evidence base | LOE | SOR |

| Guidelines | ||||||||||||

| SAMA_200351 | South African Medical Association | 2003 | South Africa | Pharmaceutical company | Gout | Phy | Multi | ER | Intermittent | NG | – | – |

| EULAR_200618 | EULAR | 2006 | Europe | EULAR | Gout | NG | Rheu | NG | NG | SLR | + | + |

| MOH_MSR_AMM_200849 | MOH, MSR, AMM | 2008 | Malaysia | Pharmaceutical company | Adults (>16 years) with gout | Phy | Multi | ER | 2012 or sooner | SLR | + | + |

| PRA_200850 | Philippine Rheumatology Association | 2008 | Philippine | NG | Gout | Phy | NG | NG | Three or more years | SLR | + | + |

| UTAustin_200952 | University of Texas at Austin | 2009 | US | University of Texas at Austin | Adults with gout | Phy | NG | ER | NG | SLR | + | + |

| EULAR_201117 | EULAR | 2011 | Multination | Pharmaceutical company, ASCR | Gout | Phy | Multi | NG | NG | SLR | + | + |

| JSGNAM_201148 | Japanese Society of Gout and Nucleic Acid Metabolism | 2011 | Japan | NG | Hyperuricemia or gout | NG | NG | ER | NG | SLR | + | + |

| ACR_201214 15 | ACR | 2012 | US | ACR, NIAMS, NIH | Gout | Phy | Multi | NG | Intermittent | SLR | + | – |

| SER_201346 | Spanish Society of Rheumatology | 2013 | Spain | Pharmaceutical company | Gout | Phy | Multi | ER | Four years | SLR | + | + |

| SIR_201345 | Italian Society of Rheumatology | 2013 | Italy | NG | Gout | Phy | Multi | NG | NG | SLR | + | + |

| FMOH_201444 | Federal Ministry of Health (Nigeria) | 2014 | Nigeria | NG | Gout | Phy, Pts in Nigeria | Multi | NG | NG | NG | – | – |

| CRA_201641 | Chinese Rheumatology Association | 2016 | China | NG | Gout in China | Phy | Multi | NG | NG | SLR | + | + |

| EULAR_201616 | EULAR | 2016 | Europe | NG | Gout | Phy, Pts | Multi | ER | Intermittent | SLR | + | + |

| TRA_201638 | Taiwan Rheumatology Association | 2016 | Taiwan, China | NG | Hyperuricemia or gout | Phy, Pts | Multi | NG | NG | NG | – | – |

| ACP_2017 19 20 | ACP | 2017 | US | ACP | Acute and recurrent gout | Phy | NG | ER | Five years | SLR | + | + |

| BSR_201721 | The British Society for Rheumatology | 2017 | UK | No specific funding | Gout in the UK | Phy | Multi | ER | Planned in 2020 | SLR | + | + |

| Consensus statements | ||||||||||||

| CCCP_201247 | Chinese College of Cardiovascular Physicians | 2012 | China | NG | Asymptomatic hyperuricemia with CVD | NG | NG | NG | NG | CS | – | – |

| 3e_201336 | 3e Initiative | 2013 | Multination | Pharmaceutical company | Gout | NG | Rheu | NG | NG | SLR | + | + |

| CSE_201 3 37 | Chinese Society of Endocrinology | 2013 | China | NG | Hyperuricemia or gout | NG | NG | NG | NG | CS | – | – |

| 3e_PT_201440 | Portuguese 3e Initiative | 2014 | Portugal | NG | Gout in Portuguese | NG | Rheu | NG | NG | SLR | + | + |

| 3e_AU_NZ_201543 | Australian and New Zealand 3e Initiative | 2015 | Multination | NG | Gout | NG | Rheu | NG | NG | SLR | + | + |

| ACR_EULAR_201542 | ACR/EULAR | 2015 | Multination | ACR, EULAR | Gout | NG | NG | ER | Intermittent | SLR | – | – |

| T2T_201639 | NG | 2016 | Multination | Pharmaceutical company | Gout | NG | Rheu | ER | NG | SLR | + | + |

| CRA_multi_201722 | Chinese multidisciplinary expert task force on hyperuricemia and its related diseases | 2017 | China | NG | Hyperuricemia | Phy | Multi | NG | NG | CS | – | – |

ACP, American College of Physicians; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; AMM, Academy of Medicine of Malaysia; ASCR, American Society of Clinical Rheumatologists; CS, consensus statement; CVD, cardiovascular diseases; ER, external review; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; LOE, level of evidence; MOH, Ministry of Health Malaysia; MSR, Malaysian Society of Rheumatology; Multi, multidisciplinary development group; NG, not given; NIAMS, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; NIH, National Institutes of Health; Phy, physicians; Pt, patients; Rheu, rheumatologists; SLR, systematic literature review; SOR, strength of recommendation; 3e, evidence, expertise, exchange.

Appraisal of guidelines and consensus statements

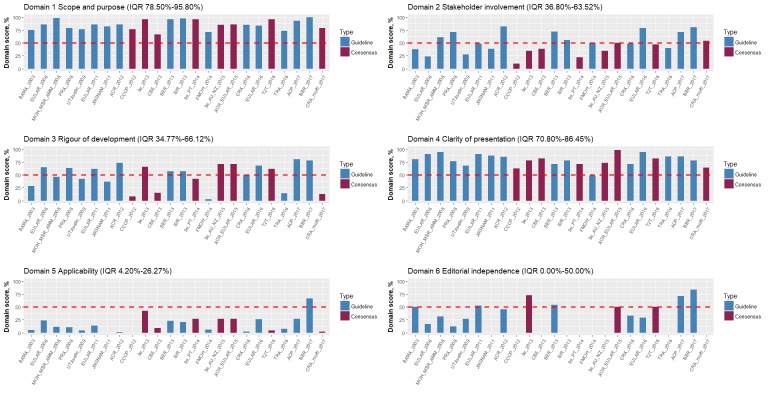

Standardised AGREE II domain scores for each guidance document were shown as figure 2 and were provided in value as online supplementary table 5. Scores for each AGREE II item were provided in mean as online supplementary table 6 and in detail as online supplementary table 7. The overall quality of guidance documents, as assessed by AGREE II, varied both between documents across domains and within documents between domains. The document with the highest domain scores was the gout management guideline published by the BSR in 2017,21 with five domains scoring above the upper quartile, followed by the guidelines published by the ACP in 2017,19 20 and the 2015 gout classification criteria by the ACR and the EULAR jointly,42 both with four domains scoring above the upper quartile. Guidelines did not always score higher than consensus statements. No tendency of improvement in the quality score over time was observed (online supplementary figure 1).

Figure 2.

Standardised domain scores for each guidance document. 3e, evidence, expertise, exchange Initiative; 3e_AU_NZ, Australian and New Zealand 3e Initiative; 3e_PT, Portuguese 3e Initiative; ACP, American College of Physicians; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; AMM, Academy of Medicine of Malaysia; ASCR, American Society of Clinical Rheumatologists; BSR, British Society for Rheumatology; CCCP, Chinese College of Cardiovascular Physicians; CRA, Chinese Rheumatology Association; CRA_multi, Chinese Multidisciplinary Expert Task Force on Hyperuricemia and Its Related Diseases; CSE, Chinese Society of Endocrinology; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; FMOH, Federal Ministry of Health (Nigeria); JSGNAM, Japanese Society of Gout and Nucleic Acid Metabolism; MOH, Ministry of Health Malaysia; MSR, Malaysian Society of Rheumatology; NIAMS, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; NIH, National Institutes of Health; PRA, Philippine Rheumatology Association; SAMA, South African Medical Association; SER, Spanish Society of Rheumatology; SIR, Italian Society of Rheumatology; T2T, treat-to-target; TRA, Taiwan Rheumatology Association; UTAustin, University of Texas at Austin.

The AGREE II instrument evaluated guidelines and consensus statements in six domains, from the development, dissemination to implementation. The scope and purpose (domain 1) of a document clarifies its clinical questions. Proper involvement of stakeholders (domain 2) balances individuals’ biases. The rigour of development domain (domain 3) is most concerned by clinicians and ensures the validity of development methodology.53 Clearly presented recommendations (domain 4) conveyed precise and accessible information from the development group to clinicians. Good performances in the applicability domain (domain 5) and the editorial independence domain (domain 6) guarantee the usefulness and the independence of documents.

Guidance documents received the highest scores for the scope and purpose domain (median 85.4%, range 66.7%–100.0%) and the clarity of presentation domain (median 79.2%, range 48.6%–98.6%), and the lowest scores for the applicability domain (median 10.9%, range 0.0%–66.7%) and the editorial independence domain (median 28.1%, range 0.0%–83.3%). The worst scored item was the monitoring or auditing criteria item (mean score 1.2, range 1.0–4.0), followed by the implementation advice or tools item (mean 1.7, range 1.0–4.8), the external review item (mean 2.1, range 1.0–6.0) and the updating procedure item (mean 2.1, range 1.0–6.5).

The ICC was 0.896. Group discussion modified 365/2208 (16.53%) of individual scores.

Synthesis of recommendations

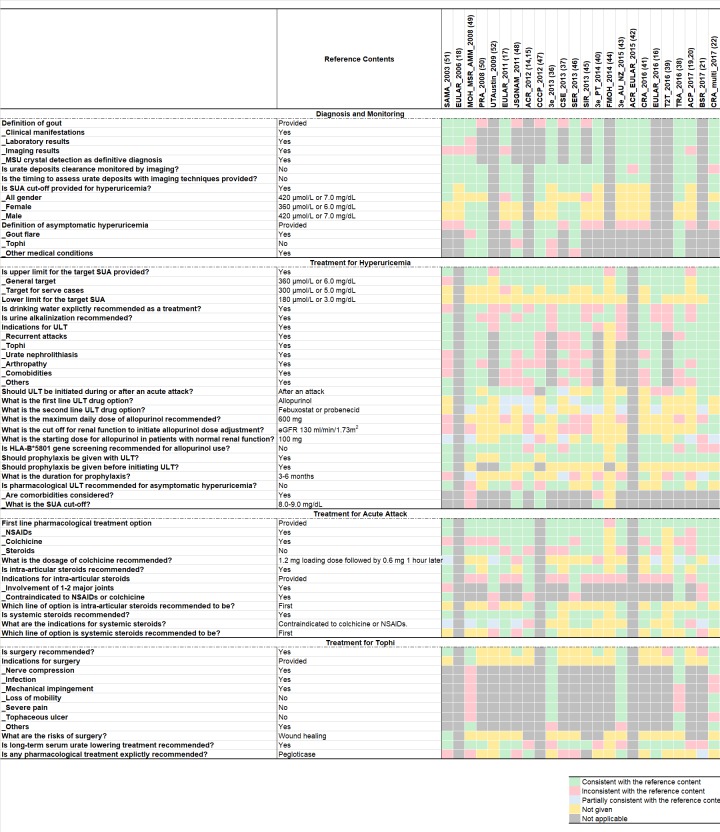

Included guidance documents addressed four major themes: diagnosis of gout and hyperuricemia, treatment for hyperuricemia, treatment for acute gout attack and treatment for tophi. Figure 3 showed key recommendations and their inconsistencies.

Figure 3.

Summary of key recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of gout and hyperuricemia. 3e, evidence, expertise, exchange Initiative; 3e_AU_NZ, Australian and New Zealand 3e Initiative; 3e_PT, Portuguese 3e Initiative; ACP, American College of Physicians; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; AMM, Academy of Medicine of Malaysia; ASCR, American Society of Clinical Rheumatologists; BSR, British Society for Rheumatology; CCCP, Chinese College of Cardiovascular Physicians; CRA, Chinese Rheumatology Association; CRA_multi, Chinese Multidisciplinary Expert Task Force on Hyperuricemia and Its Related Diseases; CSE, Chinese Society of Endocrinology; EULAR, European League AgainstRheumatism; FMOH, Federal Ministry of Health (Nigeria); JSGNAM, Japanese Society of Gout and Nucleic Acid Metabolism; MOH, Ministry of Health Malaysia; MSR, Malaysian Society of Rheumatology; NIAMS, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; NIH, National Institutes of Health; PRA, Philippine Rheumatology Association; SAMA, South African Medical Association; SER, Spanish Society of Rheumatology; SIR, Italian Society of Rheumatology; T2T, treat-to-target; TRA, Taiwan Rheumatology Association; UTAustin, University of Texas at Austin.

Approaches to diagnostic strategies for gout and hyperuricemia

Thirteen guidance documents17–20 22 36 38 40–43 46 49 51 covered the diagnosis of gout and 1117 22 37 38 45–51 covered that of hyperuricemia. Online supplementary table 8 showed key recommendations. The identification of MSU crystals in synovial fluid or tophi was a gold standard for definite diagnosis, as recommended by all included documents. In the absence of MSU crystals, three aspects were commonly evaluated for gout diagnosis, namely the clinical manifestation, considered by all documents; the laboratory result, considered by all but one document49; and the imaging result, considered by all but four documents.17 19 20 49 51

Guidance documents differed when recommending the cut-off serum uric acid (SUA) level to diagnose hyperuricemia. For the patient population in general, four documents38 47 48 51 recommended 7.0 mg/dL (or 420 μmol/L) as the cut-off, while two17 45 preferred 6.8 mg/dL. Five documents22 37 46 49 50 provided gender-specific cut-offs, recommending 6.0 mg/dL (or ~360 μmol/L) in female and 7.0 mg/dL (or ~420 μmol/L) in male. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia was defined in seven documents,36 38 46–50 among which six36 38 46–48 50 excluded patients with gout and two36 48 excluded patients with tophi when making the diagnosis. Attitudes were inconsistent for whether or not patients with renal diseases can be diagnosed with asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Patients with renal diseases were not eligible for the diagnosis in the Japanese48 and the Philippine50 guidelines, but patients with pre-existing renal or cardiovascular diseases can receive this diagnosis in the 3 Initiative document.36

Approaches to treatment for hyperuricemia

Twenty-two guidance documents14–17 19–22 36–41 43–52 covered the treatment for hyperuricemia and online supplementary table 9 summarised key recommendations. All but three documents19 20 44 52 explicitly provided target levels for long-term SUA control, most of which recommended 6.0 mg/dL (or 360 μmol/L), except the South African guideline51 which recommended 5.0 mg/dL (300 μmol/L). Two documents16 22 recommended a lower limit of 3.0 mg/dL (or 180 μmol/L) for long-term SUA management. Among these two documents, only the 2016 EULAR guideline16 explained the reason for providing a lower limit was that low SUA might increase the risk of neurodegenerative diseases, but the level of evidence and the grade of recommendation were both low.

All but six guidance documents36 39 40 43 44 52 provided explicitly indications for long-term ULT. The most commonly recommended indications were recurrent attacks,14–17 19–22 41 45 48–51 tophi,14–17 19–22 38 41 45 48–51 urate nephrolithiasis,14–17 19–22 37 38 49 50 arthropathy16 17 21 22 38 41 45 49 and comorbidities.14–16 19–22 37 47 49 50 The definition of recurrent attacks varied from at least once per year17 to at least three times per year,49 while the majority of documents14–16 19–21 41 recommended twice per year as the cut-off.

Regarding the timing to initiate ULT, the documents did not agree on whether to start pharmacological ULT after an acute attack17 21 22 36–38 40 48 49 51 52 or during an attack.14 15 37 When recommending to start ULT after an attack, the preferred time to wait since the attack resolved varied from 2 weeks37 48 to 6 weeks.52 All guidance documents based their recommendation for this question on expert opinions, due to insufficient evidence. The explanations provided for starting ULT after an attack were that ULT was better discussed when a patient was not painful,21 and that ULT initiation could prolong or worsen the acute attack.51 Two documents16 39 explicitly presented the currently conflicting views and insufficient evidence and stated consequently no recommendation for this issue.

When pharmacological ULT options were explicitly provided, allopurinol was recommended by all guidance documents14–17 21 36 40 43 45 46 48–50 to be the first-line drug, while febuxostat was recommended by three documents14 15 17 46 to be the first-line and by six documents16 21 36 40 43 45 to be the second-line. However, recommendations on the dosage of allopurinol varied largely. The maximum daily allopurinol dose recommended varied from 300 mg,51 600 mg,22 37 47 800 mg,14 15 17 38 45 to 900 mg,21 43 46 and the daily starting dose recommended in patients with normal renal function varied from 50 mg19 20 22 47 48 51 to 200 mg.21 As for patients with impaired renal function, the cut-off renal function to initiate dose adjustment was provided diversely as creatinine clearance 20–140 mL/min,37 45 46 49 51 or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 130 mL/min/1.73 m2.21 One document preferred to depend allopurinol dosage solely on eGFR by limiting the maximum daily dose to 1.5 mg/eGFR in patients with renal impairment.22 HLA-B*5801 gene screening prior to allopurinol use was recommended by five guidance documents.14 15 21 22 37 38

For patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia, 14 guidance documents14 15 17 21 36–40 43 47–49 51 52 commented on the option of pharmacological ULT, among which, 517 21 38 51 52 explicitly recommended no treatment under any circumstances. Three documents47–49 recommended pharmacological treatments in asymptomatic hyperuricemia patients with comorbidities47 48 or with very high SUA levels,40 47–49 but their cut-off SUA level to indicate ULT varied from 8.0 mg/dL47 48 to 13.0 mg/dL.49 We also found that the Portuguese consensus40 was incoherent itself by stating that no pharmacological ULT was recommended as a general principle, but also stating that pharmacological ULT was recommended for patients with SUA higher than 9 mg/dL. No direct evidence was provided by any document to support pharmacological treatment for asymptomatic hyperuricemia, and such recommendations were only made in concern of the onset of gout40 and the risk of cardiovascular events.47 48

Approaches to treatment for acute gout attack

Twenty-one guidance documents14–17 19–22 36–41 43–46 48–52 covered the treatment for acute gout attack and online supplementary table 10 summarised their key recommendations. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) was recommended by all but three documents19 20 39 44 as the first-line pharmacological treatment, while colchicine by 11 documents.14–17 21 22 36 37 40 43 45 48 Colchicine was recommended to be given in a fixed dose by three documents38 40 48 and in a loading dose followed by different doses by six documents.14–17 19 20 22 38 51 52 Seven documents21 36 41 43 45 49 50 only recommended the total daily dose for colchicine, regardless of the regimen, and their doses recommended varied from 1 mg21 49 50 to 2.4 mg.49 Suprisingly, one document43 recommended 1.8 g colchicine in 24 hours without any further explanation, which was likely a typo. Systemic steroids were recommended by all but 3 documents,37 39 44 among which 614–17 19 20 36 43 recommended them as the first-line option and 1021 22 38 41 45 46 48 50–52 recommended them when NSAIDs and colchicine were contraindicated or intolerant. Intra-articular steroids injection was recommended by 14 documents,14–17 21 22 36 38 40 43 45 46 49 51 52 among which 514–16 21 36 43 clearly recommended it as the first-line option.

Approaches to treatment for tophi

Twenty-one guidance documents14–17 19–22 36–41 43–46 48–52 covered treatment for tophi and online supplementary table 11 showed their key recommendations. Surgery was recommended by nine documents,22 36 38 40 43 48 49 51 among which five22 36 38 43 49 explicitly presented its indications, most commonly nerve compression22 36 38 43 and infection.36 38 43 The risk for surgery was only discussed by one document51 and only the risk of delayed wound healing was stated. Long-term ULT was recommended by all but two documents,44 52 but the drugs used for pharmacological treatment was only explicitly recommended by eight of them.15–17 21 37 43 46 51

Discussion

Principal findings and interpretations

This systematic review, including 16 guidelines and 8 consensus statements, found generally low methodological quality and inconsistent recommendations from guidance documents covering the diagnosis and management of gout and hyperuricemia. During revision of our work, the English version of two documents, from the Chinese Multidisciplinary Expert Task Force on Hyperuricemia and Related Diseases54 and the Taiwan Rheumatologist Association,55 respectively, were released. Despite increase in the number of guidance documents published between 2003 and 2017, the quality of documents in all domains did not seem to improve with time. To date, this is the first systematic appraisal for the quality of guidelines and consensus statements pertaining to both gout and hyperuricemia.

Comparison with existing research

Guidance documents assessed in our study performed well in the domains of scope and purpose (domain 1) and clarity of presentation (domain 4), but poorly in the domain of applicability (domain 5). These results were consistent with two previous reviews,56 57 one of which systematically assessed the quality of all guidelines for gout and the other assessed three documents released, respectively, by the 3e Initiative,36 the ACR14 15 and the EULAR.18 58 Our study systematically included both guidelines and consensus statements in the field of both gout and hyperuricemia, and the diverse performance by different AGREE II domains was shared across both types of document.

This distribution of AGREE II domain scores has been observed by many previous guideline appraisal studies, in which documents scored higher in the scope and purpose domain and the clarity of presentation domain, and lower in the applicability domain and the editorial independence domain. This domain score distribution was not only shared by guidance documents for endocrinology diseases, such as diabetes59 60 and thyroid disorders,31 61 and rheumatology diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis32 62 63 and systemic lupus erythematosus,64 but also shared by documents for diseases in other clinical specialities.33 65–67 Despite generally low and varied scores in the applicability domain, guidance documents for gout and hyperuricemia performed obviously poorer comparing with documents for other conditions,31–33 59–61 63–67 suggesting that improving the usefulness of guidance being more challenging in gout and hyperuricemia. One major impediment to good applicability of guidance document is the time and cost to perform economic evaluations and pilot studies, and a stable and long-term task force of guideline development is required to conduct these evaluations and studies. Although forming such a task force is practically difficult in some regions and countries, guidance documents were suggested to at least inform audience the need to consider these issues.65 Low scores in the editorial independence domain often resulted from lacking of detailed information on the influence of funding body and on the conflict of interests. We found that 50% of documents declaring funding sources were supported by the pharmaceutical industry, calling for awareness of the potential influence of pharmaceutical industry on the synthesis of clinical guidance and for the need of promoting transparency in financial declaration.

Clinical implications and future research

Guidance documents were concordant and recommended a target for SUA <6.0 mg/dL (or 360 μmol/L) for long-term control, to consider recurrent attacks as one of the indications for ULT (although the definitions for recurrent attacks differed), to consider allopurinol as the first-line ULT and NSAIDs as the first-line drug in acute attack, and to consider long-term ULT in patient with tophi. Despite these similarities, recommendations differed in the majority of items and these discrepancies might come from several sources, including ethnic difference, quality of documents and lack of evidence.

Ethnical and social differences are important reasons why recommendations may vary between guidelines and consensus, and such diversity is to be encouraged, in order to best meet the needs of local populations. One example was that Asian guidance documents were more likely to recommend HLA-B*5801 gene screening before prescribing allopurinol.22 37 38 HLA-B*5801 gene screening was promoted because the risk of hypersensitivity reactions associated with allopurinol is significantly increased in individuals carrying the variant allele HLA-B*5801. Studies suggested that the frequency of this variant allele are higher in Han Chinese, Korean and Tai people than that in the Caucasian population,14 15 21 and that that HLA-B*5801 gene screening prior to allopurinol initiation is cost-effective for Asians but not Caucasians.68 69 These findings are consistent with the preferences of Asian documents. Providing ethnicity-specific recommendations or explicitly specifying the ethnicity of target audience helps clarify this source of inconsistency and improves the precision of recommendations.

However, it is worrying that low methodological quality of guidance documents may also lead to discrepant recommendations and consequent variability in application. Our study suggested that comparing to high-quality documents,16 19–21 36 42 46 low-quality ones22 37 38 44 47 52 were more likely to provide ambiguous prioritisation of both (1) ULT drugs for hyperuricemia and (2) steroid options for acute attack. A quick notice was that when making this rough summary, we considered a document to be high-quality when it scored above the upper quartile in at least three out of the six AGREE II domains, and to be low-quality when it scored below the lower quartile in at least three out of the six AGREE II domains. Among all AGREE II domains, those pertaining to stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, applicability and editorial independence could be improved by standardising developing processes, which consequently improved the reliability of recommendations. These results reinforced that it is better for clinicians to refer to high-quality guidance documents instead of the low-quality ones. However, when high-quality documents are unavailable in local language, referring to low-quality local documents might mislead clinical practice in the region. Selecting appropriate guidance documents to follow in clinical practice is thus more challenging for non-English speaking countries, including China.13 Moreover, the oldest document included in our study was the South African Medical Association guideline, published in 2003, and no guidance document in either English or Chinese was released in South African in the last 16 years. This finding suggested that some old documents might still affect regional practice. Efforts to timely update or declare the withdrawal of existing guidance documents are also critical for clinical practice.

Guidance documents are considered as the starting point to identify evidence gaps and to prioritise research questions.70 Evidence gaps were discussed in the recommendations of both (1) treatment for asymptomatic hyperuricemia, by 514 15 36 37 39 43 out of 14 documents,14 15 17 21 36–40 43 47–49 51 52 and (2) timing to initiate ULT, by 216 39 out of 14 documents.14–17 21 22 36–40 48 49 51 52 Although the rest of documents provided explicit recommendations, they based their recommendations either on indirect evidence or expert opinions. As for gout and hyperuricemia, evidence synthesis is warranted for the effects of pharmacological ULT in patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia and for the optimal timing to initiate ULT in patients with the acute attack.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of our review included a systematic approach to identify guidance documents pertaining to the diagnosis and management of hyperuricemia and gout. Both guidelines and consensus statements were evaluated and compared. We used the AGREE II instrument, an international, validated and rigorously developed tool, to assess the quality of document development and we tailored the AGREE II instrument to point-by-point scoring criteria (online supplementary file 1) to improve the objectivity and reproducibility of our study. We summarised all key recommendations, and compared and visualised the inconsistencies among them, providing a concise but informative overview for clinicians and researchers.

Our study also has limitations. First, we only included documents published in English or Chinese, which could lead to a risk of neglecting essential documents from regions not using English or Chinese as the first language. We attempted to mitigate this risk by tailoring our search strategy to identify the English versions of guidance documents published from these regions. Second, unconscious bias from a subjective rating of documents was inevitable. We avoided inviting coauthors of guidance documents as reviewers to prevent subconscious competing interest, and conducted two rounds of group discussions to minimise subjective bias. Third, the AGREE II instrument itself has weaknesses,31 59 67 71 although it was the most commonly used tool to assess the quality of guidance documents. The AGREE system assigned equal weight to all six domains, regardless of their relative importance.72 Although better methods of guideline development and greater transparency of reporting are associated with more reliable recommendations, they do not guarantee better patient outcomes. Hence, the quality scores assessed by the AGREE II should be interpreted with caution, especially when used to indicate which guidelines to follow in clinical practice. Moreover, the subjective interpretation of scoring criteria impeded the replicability of AGREE II studies and direct comparison of quality scores in guidance documents provided by different reviews. Fourth, our literature search was over 12 months old when the study was ready to publish, affecting the timeliness of our study. However, we eventually decided not to update the literature at a late stage of the study, because of the infeasibility of bringing together all reviewers with another round of centralised training and appraisal, and the risk of inconsistent scoring criteria for each reviewer after a long time since their previous scoring. Moreover, a quick review of publications in PubMed, using the same search strategy (online supplementary table 1) and limiting the publication date from 1 September 2016 to 21 January 2019, did not found any new relevant documents, reassuring us of the timeliness of our study.

Conclusions

The methodological quality needs to be improved in the current guidelines and consensuses on the diagnosis and management of gout and hyperuricemia, as assessed by the AGREE II. Inconsistent recommendations are common, even in some key aspects. Promoting standard methods for guidance documents development, and synthesising high-quality clinical evidence to fill in evidence gaps, are warranted to improve the quality of guidance documents.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

QL and XL contributed equally.

Author's contributions: HT and SL conceived this study. QL, JS-WK and SL designed the inclusion/exclusion criteria and the searching resource and strategy. QL, JS-WK, HC, LL and XS designed the appraisal strategy of each included guideline and consensus. QL and XL searched literature search and extracted data. QL, XL, JW, HL and SL assessed the quality of each document. QL analysed and visualised the outcomes. S-CC, AS, YC, ZA, XS and HH provided critical review. QL, XL and SL drafted the manuscript. All authors discussed actively in the protocol of the study.

Funding: This research received no specific funding from any bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. AS is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre and a THIS Institute postdoctoral fellowship. HH is a NIHR Senior Investigator. His work is supported by: (1) Health Data Research UK, which is funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Department of Health and Social Care (England), Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Health and Social Care Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland), British Heart Foundation and Wellcome Trust. (2) The BigData@Heart Consortium, funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative-2 Joint Undertaking under grant agreement No 116074. This Joint Undertaking receives support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and EFPIA; it is chaired, by DE Grobbee and SD Anker, partnering with 20 academic and industry partners and ESC. (3) The NIHR University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre. SL was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81400811 and 21534008), National Basic Research Program of China (grant number 2015CB942800), the Scientific Research Project of Health and Family Planning Commission of Sichuan Province (grant number 130029, 150149, 17PJ063 and 17PJ445), Cholesterol Fund by China Cardiovascular Foundation and China Heart House and the International Visiting Program for Excellent Young Scholars of Sichuan University.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data in this paper were obtained from published studies. No additional data are available from the authors.

References

- 1. Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. . Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:26–35. 10.1002/art.23176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu R, Han C, Wu D, et al. . Prevalence of hyperuricemia and gout in mainland China from 2000 to 2014: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015(15, supplement):1–12. 10.1155/2015/762820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kuo C-F, Grainge MJ, Zhang W, et al. . Global epidemiology of gout: prevalence, incidence and risk factors. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015;11:649–62. 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith E. March L: Global prevalence of hyperuricemia: a systematic review of population-based epidemiological studies. Arthritis & Rheumatology 2015;67:2690–2. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith E, Hoy D, Cross M, et al. . The global burden of gout: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1470–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kuo C-F, Grainge MJ, Mallen C, et al. . Rising burden of gout in the UK but continuing suboptimal management: a nationwide population study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:661–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li X, Meng X, Timofeeva M, et al. . Serum uric acid levels and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review of evidence from observational studies, randomised controlled trials, and Mendelian randomisation studies. BMJ 2017;357:j2376 10.1136/bmj.j2376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tausche A-K, Jansen TL, Schröder H-E, et al. . Gout--current diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2009;106:549–55. 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dincer HE, Dincer AP, Levinson DJ. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia: to treat or not to treat. Cleve Clin J Med 2002;69:594–608. 10.3949/ccjm.69.8.594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pittman JR, Bross MH. Diagnosis and management of gout. Am Fam Physician 1999;59:1799–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Perez-Ruiz F, Lioté F. Lowering serum uric acid levels: what is the optimal target for improving clinical outcomes in gout? Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:1324–8. 10.1002/art.23007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Singh JA, Hodges JS, Toscano JP, et al. . Quality of care for gout in the US needs improvement. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:822–9. 10.1002/art.22767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen Y, Wang C, Shang H, et al. . Clinical practice guidelines in China. BMJ 2018;360:j5158 10.1136/bmj.j5158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al. . 2012 American College of rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:1431–46. 10.1002/acr.21772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al. . 2012 American College of rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and antiinflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:1447–61. 10.1002/acr.21773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. . 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:29–42. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hamburger M, Baraf HSB, Adamson TC, et al. . 2011 recommendations for the diagnosis and management of gout and hyperuricemia. Postgrad Med 2011;123(6 Suppl 1):3–36. 10.3810/pgm.2011.11.2511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang W, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. . EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part I: diagnosis. Report of a task force of the standing Committee for international clinical studies including therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1301–11. 10.1136/ard.2006.055251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Qaseem A, McLean RM, Starkey M, et al. . Diagnosis of acute gout: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:52–7. 10.7326/M16-0569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Qaseem A, Harris RP, Forciea MA, et al. . Management of acute and recurrent gout: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:58–68. 10.7326/M16-0570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hui M, Carr A, Cameron S, et al. . The British Society for rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Rheumatology 2017;56:1056–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Multi-Disciplinary Expert Task Force on Hyperuricemia and Its Related Diseases [Chinese multi-disciplinary consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of hyperuricemia and its related diseases]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2017;56:235–48. (Original document in Chinese) 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2017.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McLean RM. The long and winding road to clinical guidelines on the diagnosis and management of gout. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:73–4. 10.7326/M16-2426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bardin T, Richette P. New ACR guidelines for gout management hold some surprises. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013;9:9–11. 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dalbeth N, Bardin T, Doherty M, et al. . Discordant American College of physicians and international rheumatology guidelines for gout management: consensus statement of the gout, hyperuricemia and Crystal-Associated disease network (G-CAN). Nat Rev Rheumatol 2017;13:561–8. 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khanna PP, FitzGerald J. Evolution of management of gout: a comparison of recent guidelines. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2015;27:139–46. 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li Q, Li X, Kwong JS-W, et al. . Diagnosis and treatment for hyperuricaemia and gout: a protocol for a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014928 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. . Agree II: advancing Guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010;182:E839–E842. 10.1503/cmaj.090449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, et al. . Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:38-47–47. 10.7326/0003-4819-160-1-201401070-00732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Deng Y, Luo L, Hu Y, et al. . Clinical practice guidelines for the management of neuropathic pain: a systematic review. BMC Anesthesiol 2016;16:12 10.1186/s12871-015-0150-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang T-W, Lai J-H, Wu M-Y, et al. . Systematic review of clinical practice guidelines in the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules and cancer. BMC Med 2013;11:191 10.1186/1741-7015-11-191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lopez-Olivo MA, Kallen MA, Ortiz Z, et al. . Quality appraisal of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements on the use of biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1625–38. 10.1002/art.24207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nagler EV, Vanmassenhove J, van der Veer SN, et al. . Diagnosis and treatment of hyponatremia: a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements. BMC Med 2014;12:231 10.1186/s12916-014-0231-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Agree II training tools. Available: http://www.agreetrust.org-resource-centre-agree-ii-training-tooles/ [Accessed Aug 01 2017].

- 35. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. . Development of the agree II, part 1: performance, usefulness and areas for improvement. Can Med Assoc J 2010;182:1045–52. 10.1503/cmaj.091714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sivera F, Andrés M, Carmona L, et al. . Multinational evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of gout: integrating systematic literature review and expert opinion of a broad panel of rheumatologists in the 3E initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:328–35. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chinese Society of Endocrinology Chinese consensus on the management of hyperuricemia and gout. Chin J Endocrinol Metab 2013;29:913–20. (Original document in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 38. Association TR Taiwan guideline for the management of gout and hyperuricemia - updated 2016. F J Rheumatol 2016;30:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kiltz U, Smolen J, Bardin T, et al. . (T2T) recommendations for gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Araújo F, Cordeiro I, Teixeira F, et al. . Portuguese recommendations for the diagnosis and management of gout. Acta Reumatol Port 2014;39:158–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chinese Rheumatology Association 2016 Chinese guideline on the diagnosis and management of gout. Chin J Intern Med 2016;55:892–9. (Original document in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 42. Neogi T, Jansen TLTA, Dalbeth N, et al. . 2015 gout classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1789–98. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Graf SW, Whittle SL, Wechalekar MD, et al. . Australian and New Zealand recommendations for the diagnosis and management of gout: integrating systematic literature review and expert opinion in the 3E initiative. Int J Rheum Dis 2015;18:341–51. 10.1111/1756-185X.12557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Federal Ministry of Health (Nigeria) National nutritional guideline on non-communicable disease prevention, control and management. Available: http://www.health.gov.ng/doc/NutritionalGuideline.pdf [Accessed 28 Jul 2017].

- 45. Manara M, Bortoluzzi A, Favero M, et al. . Italian Society of rheumatology recommendations for the management of gout. Reumatismo 2013;65:4–21. 10.4081/reumatismo.2013.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER) Clinical practice guidelines for management of gout. Available: https://www.ser.es/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/GuipClinGot_1140226_EN.pdf [Accessed 28 Jul 2017].

- 47. Hu D. The diagnosis and treatment advice of cardiovascular disease combined asymptomatic hyperuricemia (second edition). Chin J Cardiovas Res 2012;10:241–9. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yamanaka H. Japanese guideline for the management of hyperuricemia and gout: second edition. Nucleosides, Nucleotides and Nucleic Acids 2011;30:1018–29. 10.1080/15257770.2011.596496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ministry of Health Malaysia (MOH) Management of gout. Available: http://www.moh.gov.my/penerbitan/CPG2017/3893.pdf [Accessed 28 July 2017].

- 50. Li-Yu J, Salido E, Manahan S, et al. . Philippine clinical practice guidelines for the management of gout. Int J Rheum Dis [Google Scholar]

- 51. Meyers OL, Cassim B, Mody GM. Hyperuricaemia and gout: clinical guideline 2003. S Afr Med J 2003;93:961–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Management of initial gout in adults. The University of Texas at Austin, school of nursing, family nurse practitioner program. Available: http://www.alabmed.com/uploadfile/2014/0515/20140515070230703.pdf [Accessed 25 July 2017].

- 53. Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M. Developing guidelines. BMJ 1999;318:593–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Multidisciplinary Expert Task Force on Hyperuricemia and Related Diseases Chinese multidisciplinary expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of hyperuricemia and related diseases. Chin Med J 2017;130:2473–88. 10.4103/0366-6999.216416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yu K-H, Chen D-Y, Chen J-H, et al. . Management of gout and hyperuricemia: multidisciplinary consensus in Taiwan. Int J Rheum Dis 2018;21:772–87. 10.1111/1756-185X.13266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nuki G. An appraisal of the 2012 American College of rheumatology guidelines for the management of gout. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2014;26:152–61. 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang D, Yu Y, Chen Y, et al. . Assessing the quality of global clinical practice guidelines on gout using agree II instrument. J Clin Rheumatol 2018. 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, et al. . EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: management. Report of a task force of the EULAR standing Committee for international clinical studies including therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1312–24. 10.1136/ard.2006.055269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Holmer HK, Ogden LA, Burda BU, et al. . Quality of clinical practice guidelines for glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One 2013;8:e58625 10.1371/journal.pone.0058625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wu CM, Wu AM, Young BK, et al. . An appraisal of clinical practice guidelines for diabetic retinopathy. Am J Med Qual 2016;31:370–5. 10.1177/1062860615574863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Fang Y, Yao L, Sun J, et al. . Appraisal of clinical practice guidelines on the management of hypothyroidism in pregnancy using the appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation II instrument. Endocrine 2018;60:4–14. 10.1007/s12020-018-1535-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hazlewood GS, Akhavan P, Schieir O, et al. . Adding a "GRADE" to the quality appraisal of rheumatoid arthritis guidelines identifies limitations beyond AGREE-II. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:1274–85. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Palmowski Y, Buttgereit T, Dejaco C, et al. . “Official view” on glucocorticoids in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of international guidelines and consensus statements. Arthritis Care Res 2017;69:1134–41. 10.1002/acr.23185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tunnicliffe DJ, Singh-Grewal D, Kim S, et al. . Diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:1440–52. 10.1002/acr.22591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Alonso-Coello P, Irfan A, Solà I, et al. . The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: a systematic review of guideline appraisal studies. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19 10.1136/qshc.2010.042077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Devroey D, Vantomme K, Betz W, et al. . A review of the treatment guidelines on the management of low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Cardiology 2004;102:61–6. 10.1159/000077906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gavriilidis P, Roberts KJ, Askari A, et al. . Evaluation of the current guidelines for resection of hepatocellular carcinoma using the appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation II instrument. J Hepatol 2017;67:991–8. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jutkowitz E, Dubreuil M, Lu N, et al. . The cost-effectiveness of HLA-B*5801 screening to guide initial urate-lowering therapy for gout in the United States. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017;46:594–600. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Plumpton CO, Alfirevic A, Pirmohamed M, et al. . Cost effectiveness analysis of HLA-B*58:01 genotyping prior to initiation of allopurinol for gout. Rheumatology 2017;56:1729–39. 10.1093/rheumatology/kex253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Li T, Vedula SS, Scherer R. What comparative effectiveness research is needed? A framework for using guidelines and systematic reviews to identify evidence gaps and research priorities. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:367–77. 10.7326/0003-4819-156-5-201203060-00009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Brosseau L, Rahman P, Poitras S, et al. . A systematic critical appraisal of non-pharmacological management of rheumatoid arthritis with appraisal of guidelines for research and evaluation II. PLoS One 2014;9:e95369 10.1371/journal.pone.0095369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Watine J, Friedberg B, Nagy E, et al. . Conflict between guideline methodologic quality and recommendation validity: a potential problem for practitioners. Clin Chem 2006;52:65–72. 10.1373/clinchem.2005.056952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026677supp001.pdf (582.6KB, pdf)