Abstract

Glioblastoma is the most aggressive common brain tumor in adults. Curcumin, from Curcuma longa, is an effective antitumor agent. Although the same proteins control both autophagy and cell death, the molecular connections between them are complicated and autophagy may promote or inhibit cell death. We investigated whether curcumin affects autophagy, which regulates curcumin-mediated tumor cell death in A172 human glioblastoma cells. When A172 cells were incubated with 10 μM curcumin, autophagy increased in a time-dependent manner. Curcumin-induced cell death was reduced by co-incubation with the autophagy inhibitors 3-methyladenine (3-MA), hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), and LY294002. Curcumin-induced cell death was also inhibited by co-incubation with rapamycin, an autophagy inducer. When cells were incubated under serum-deprived medium, LC3-II amount was increased but the basal level of cell viability was reduced, leading to the inhibition of curcumin-induced cell death. Cell death was decreased by inhibiting curcumin-induced autophagy using small interference RNA (siRNA) of Atg5 or Beclin1. Therefore, curcumin-mediated tumor cell death is promoted by curcumin-induced autophagy, but not by an increase in the basal level of autophagy in rapamycin-treated or serum-deprived conditions. This suggests that the antitumor effects of curcumin are influenced differently by curcumin-induced autophagy and the prerequisite basal level of autophagy in cancer cells.

Keywords: Curcumin, Autophagy, Glioblastoma, Antitumor activity

INTRODUCTION

Curcumin is the most studied dietary phytochemical. It originated from the rhizome of Curcuma longa Linn (Zingiberaceae) (Gupta et al., 2006; Fu et al., 2018). Curcumin is an antioxidant with analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, and antimicrobial activities (Ak and Gulcin, 2008; Anand et al., 2008; Sa and Das, 2008; Shehzad et al., 2010; Wilken et al., 2011). It also has anticancer activity, affecting tumor initiation, proliferation, progression, metastasis, invasion, and angiogenesis (Kawamori et al., 1999; Kunnumakkara et al., 2008). Curcumin-mediated anticancer activity is associated with the inhibition of cell growth and the induction of apoptosis and autophagy (Klinger and Mittal, 2016; Lee et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017; Veeran et al., 2017). Curcumin induces autophagy and apoptosis in human gastric cancer cells (Li et al., 2017; Fu et al., 2018), human colon cancer cells (Zhang et al., 2016), brain tumor cells (Zanotto-Filho et al., 2015), and Sf9 insect cells (Veeran et al., 2017).

Autophagy is characterized by the formation of large double-membrane vesicles, called autophagosomes, in the cytosol. An autophagosome is formed by the hierarchical recruitment of autophagy-related (Atg) proteins, including LC3 and Beclin1, to phagophore assembly sites (Codogno et al., 2011). These vesicles dock and fuse with lysosomes to deliver their contents into the hydrolytically active lumen (Monastyrska et al., 2009). Many stress pathways elicit autophagy and apoptosis sequentially within the same cell. Defective autophagy plays an important role in human pathologies, including cancer, neurodegeneration, and infectious diseases (He and Klionsky, 2009). The autophagy machinery is regulated by molecular mechanisms from transcriptional activation to post-translational protein modification (He and Klionsky, 2009; Marino et al., 2014; Abdul Rahim et al., 2017).

Generally, autophagy blocks the induction of apoptosis, and apoptosis-associated caspase activation shuts off the autophagic process. However, autophagy or autophagy-relevant proteins may promote the induction of apoptosis or necrosis, which leads to autophagic cell death (ACD) (Marino et al., 2014). Therefore, disruption of the relationship between autophagy and ACD has important pathophysiological consequences for preventing or treating diseases (Yonekawa and Thorburn, 2013; Marino et al., 2014).

In cancer cells, a complex relationship exists between autophagy as a suppressor and promoter of tumor progression (Noonan et al., 2016). The connections between autophagy and cell death are complicated (Lefranc and Kiss, 2006). ACD is induced in breast tumor cells, lung cancer cells, and glioblastoma; therefore, stress-induced autophagy is not, of necessity, cytoprotective in function (Sharma et al., 2014). Although many chemotherapeutic drugs and radiation promote ACD by inhibiting autophagy, drugs in combination with radiation, chemotherapeutic agents, and various drug combinations promote ACD (Sharma et al., 2014).

Brain malignancies have a poor prognosis despite multimodal treatment with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy (Zanotto-Filho et al., 2015; Klinger and Mittal, 2016). Malignant gliomas are characterized by diffuse infiltration of the brain parenchyma (Lefranc and Kiss, 2006). Glioblastomas, the largest group of malignant gliomas, show cytoplasmic overexpression of autophagic proteins to varying extents. Atg proteins are increased in glioblastoma patients after radiotherapy (Giatromanolaki et al., 2014). To augment the limited therapeutic options for glioblastoma, the potential chemotherapeutic benefits of compounds from natural products have been studied (Klinger and Mittal, 2016). However, little is known about their role in ACD. Temozolomide is the most efficacious drug against glioblastoma, and it exerts cytotoxic activity through proautophagic processes (Lefranc and Kiss, 2006). However, the mechanism underlying the curcumin-induced anticancer effect associated with the induction of autophagy is not clear. Therefore, we investigated whether curcumin-induced autophagy contributes to enhanced ACD using A172 human glioblastoma cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and plasmids

MTT [3(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide], trypan blue solution, curcumin and 3-methyladenine (3-MA) were purchased from the Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies reactive with α-tubulin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Antibodies reactive with LC3 were obtained from NOVUS Biologicals (Littleton, CO, USA). 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA). We purchased autophagy antibody sampler kit including antibodies reactive with Atg3, Atg5, Atg7, Atg12, Atg16L1, LC3A, LC3B and Beclin-1 from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). LY294002 was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Rapamycin and hydroxyquinoline (HCQ) were obtained from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA). Except where indicated, all other materials are obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

pEGFP-C2 plasmid was kindly provided by Prof. Mi-Ock Lee, College of Pharmacy, Seoul National University (Seoul, Korea). pGFP-LC3 plasmid was kindly provided by Prof. Dong-Hyung Cho, Graduate School of East-West Medical Science, Kyung Hee University (Yongin, Korea).

Cell culture

A172 human glioblastoma cells were obtained from the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB) cell bank (Daejeon, Korea). Cells were maintained and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY, USA), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 U/mL streptomycin. Then, cells were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of humidified incubator with 5% CO2 and 95% air (Lee et al., 2015; Ryu et al., 2015).

Cytotoxicity assay

Cell survival was quantified by counting cells with trypan blue exclusion assay or by using colorimetric assay described for measuring intracellular succinate dehydrogenase content with MTT (Yang et al., 2014). Confluent cells were cultured with various concentrations of each reagent for 24 h. Cells were then incubated with 50 μg/ml of MTT at 37°C for 2 h. Formazan formed by MTT were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). Optical density (OD) was read at 540 nm.

Measurement of DNA condensation

Cells with the indicated condition were grown on coverslip for 24 h and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution freshly prepared in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min. Then, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Nucleus was visualized by staining cells with 4′,6-di-amidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Then, cells were observed and photographed at 400X or 1,000X magnification under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Number of cells with DNA-condensed nucleus was counted and calculated to a percentage of total cell number.

Transfection of nucleic acids

Each plasmid DNA was transfected into cells as follows. Briefly, each nucleic acid and lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Calsbad, CA, USA) was diluted in serum-free medium and incubated for 5 min, respectively. The diluted nucleic acid and lipofectamine 2000 reagent was mixed by inverting and incubated for 20 min to form complexes. In the meanwhile, cells were stabilized by the incubation with culture medium without antibiotics and serum for at least 2 h prior to the transfection. Pre-formed complexes were added directly to the cells and cells were incubated for an additional 6 h. Then, culture medium was replaced with antibiotic and 10% FBS-containing DMEM and incubated for 24 h-72 h prior to each experiment.

Measurement of autophagy activation

Autophagy was determined by the observation of LC3 puncta-positive structures, which are the essential dynamic process in autophagosome formation (Wu et al., 2015; Yao et al., 2017). Cells were transfected with GFP-LC3 plasmid DNA and treated with curcumin for an appropriate time. Then, cells were fixed with 4% PFA solution freshly prepared in PBS for 10 min. Then, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Nucleus was visualized by staining cells with DAPI. Then, the number of GFP-LC3 punctas was counted within each sample and autophagic cells were determined by counting the number of cells with GFP-LC3 punctate structure under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon).

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed using a standard protocol. Cells were lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer containing 0.5% Nonidet P-40 (vol/vol) in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3); 150 mM NaCl; protease inhibitors (2 μg/ml aprotinin, pepstatin, and chymostatin; 1 μg/ml leupeptin and pepstatin; 1 mM phenyl-methyl sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF); and 1 mM Na4VO3. Lysates were incubated for 1 h on ice before centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. Protein concentration in each supernatant was measured using a SMARTTM BCA protein assay kit (iNtRON Biotech. Inc., Seoul, Korea). Proteins were denatured by boiling for 5 minutes in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer. Proteins were separated by 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes by electro-blotting. Following transfer, equal loading of protein was verified by Ponceau staining. The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6; 150 mM NaCl; 0.5% Tween 20) and incubated with the indicated antibodies. Bound antibodies were visualized with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies with the use of enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Primary and HRP-labelled secondary anti-IgG antibodies were diluted 1:1,000 and 1:5,000, respectively in TBST containing 0.5% Tween 20. Immunoreactive bands were detected using X-ray film.

Statistical analyses

Experimental differences were tested for statistical significance using ANOVA and Students’ t-test. p-value of <0.05 or <0.01 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Curcumin-induced cell death and autophagy

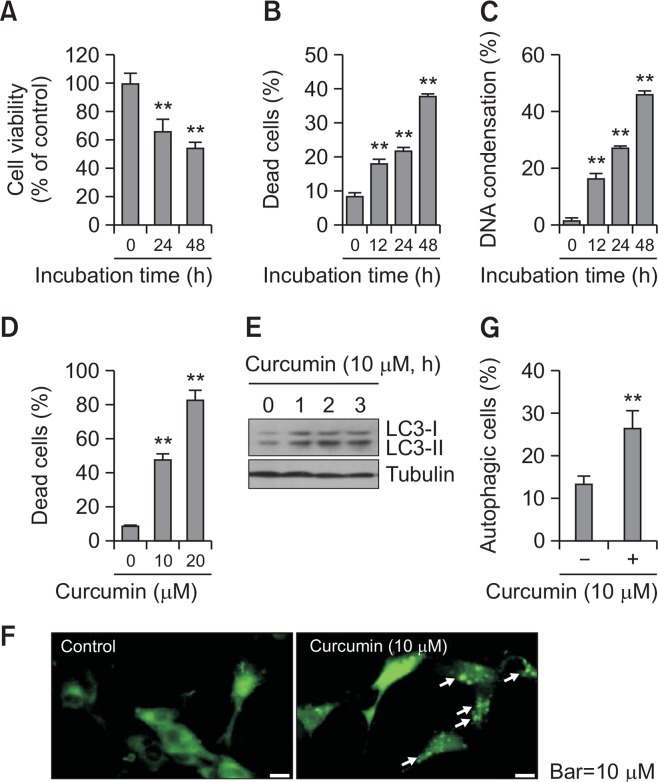

Given that malignant glioma has a poor prognosis (Zanotto-Filho et al., 2015; Klinger and Mittal, 2016) and curcumin-mediated anticancer activity is associated with cell growth inhibition and the induction of apoptosis and autophagy (Klinger and Mittal, 2016; Lee et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017; Veeran et al., 2017), we observed changes in curcumin-induced cell death and autophagy in A172 human glioblastoma cells. Cell viability was measured with the MTT assay (Fig. 1A). The percentage of cell death were counted using the trypan blue exclusion method (Fig. 1B, 1D) or DAPI staining (Fig. 1C). When A172 cells were treated with 10 μM curcumin for 24 or 48 h, cell viability was reduced to 65 and 52%, respectively, compared with the control (Fig. 1A). When A172 cells were treated with 10 μM curcumin for 12, 24, or 48 h, the percentage of dead trypan blue-positive cells was increased to 18, 22, and 40%, respectively, compared with 8% in the control (Fig. 1B). In addition, the percentage of cells with DNA condensation increased to 16, 27, and 54%, respectively, on treatment with 10 μM curcumin for 12, 24, and 48 h, as compared with 3% in the control (Fig. 1C). When A172 cells were treated with 10 or 20 μM curcumin for 24 h, the percentage of dead trypan blue-positive cells increased to 48 and 82%, respectively, versus 9% in the control (Fig. 1D). This demonstrated that curcumin is effective in A172 human glioblastoma cell death.

Fig. 1.

Curcumin treatment enhanced cell death and autophagy in glioblastoma cells. (A–C) A172 glioblastoma cells were treated with 10 μM curcumin for 12, 24, and 48 h. Then, cell viability was measured by MTT assay as described in materials and methods (A). Dead cells were estimated by trypan blue exclusion assay (B). DNA condensation was assessed by DAPI staining (C). (D) A172 cells were treated with 10 or 20 μM curcumin for 24 h and dead cells were estimated by trypan blue exclusion assay. (E–G) A172 cells were treated with 10 μM curcumin for 1, 2 and 3 h. Cell lysates were prepared and LC3 proteins were detected by western blotting (E). LC3 puncta formation was observed under fluorescence microscope with 1,000X magnification. Arrows indicated representative LC3 puncta (F). Autophagic cells with LC3 puncta were counted (G). Data in bar graph represent mean ± SED. **p<0.01, significantly different from curcumin-untreated control (A–D, G).

Autophagy is characterized by autophagosome formation via hierarchical recruitment of Atg proteins, including LC3 and Beclin1, to phagophore assembly sites (Codogno et al., 2011), and we observed changes in the amount of LC3-II, a marker of autophagy. LC3-I and LC3-II increased time-dependently on treatment with 10 μM curcumin for 1, 2 and 3 h (Fig. 1E). In addition, when LC3 puncta structures were visualized by transfection with GFP-LC3 plasmid DNA, the treatment with 10 μM curcumin increased the number of autophagic cells with LC3 puncta (Fig. 1F). The percentage of cells with LC3 puncta increased to 26% in the curcumin-treated group compared with 13% in the control (Fig. 1G). These results suggest that curcumin-mediated cell death is associated with autophagy induced by treatment with curcumin.

Curcumin-induced cell death was decreased by co-treatment with autophagy inhibitors

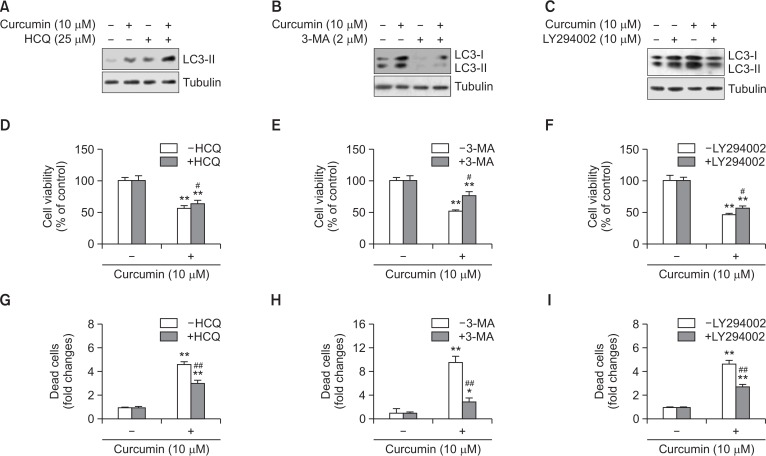

To confirm the effect of curcumin-induced autophagy on curcumin-mediated cytotoxicity, cells were co-treated and incubated with the autophagy inhibitors 3-methyladenine (3-MA), hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), or LY294002 in the presence of 10 μM curcumin for 3 or 24 h. Autophagic flux using HCQ inhibits the autophagosomal lysosome degradation induced by curcumin, which accumulates LC3-II (Fig. 2A). 3-MA and LY294003 reduced LC3-II accumulation in the group co-treated with curcumin and inhibitors (Fig. 2B, 2C). Then, cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay or trypan blue exclusion assay. In the MTT assay, cell viability increased to ∼63% on co-treatment with curcumin and HCQ versus ∼56% in the curcumin-treated group (Fig. 2D), ∼51% on co-treatment of curcumin with 3-MA versus 76% in the curcumin-treated group (Fig. 2E), and ∼56% on co-treatment with curcumin and LY294002 versus ∼48% in the curcumin-treated group (Fig. 2F). Cell death was determined with the trypan blue exclusion assay. The fold change in cell death increased to ∼4.8 on co-treatment with curcumin and HCQ versus ∼2.9 in the curcumin-treated group (Fig. 2G), ∼8.9 fold on co-treatment of curcumin with 3-MA versus ∼2.8 fold in the curcumin-treated group (Fig. 2H), and ∼4.8 fold on co-treatment with curcumin and LY294002 versus ∼2.9 fold in the curcumin-treated group (Fig. 2I). These results suggest that curcumin-induced autophagy enhances curcumin-mediated A172 glioblastoma cell death.

Fig. 2.

Autophagy inhibitors attenuated curcumin-induced cell death. (A–C) A172 glioblastoma cells were treated with 10 μM curcumin in the presence of autophagy inhibitors such as hydroxyquinoline (HCQ) (A), 3-methyladenine (3-MA) (B) or LY294002 (C) for 3 h. Then, cell lysates were prepared and LC3 proteins were detected by western blotting. (D–I) A172 cells were treated with 10 μM curcumin in the presence of autophagy inhibitors such as HCQ (D, G), 3-MA (E, H) or LY294002 (F, I) for 24 h. Then, cell viability was measured by MTT assay as described in materials and methods (D–F). Dead cells were estimated by trypan blue exclusion assay (G–I). Data in bar graph represent mean ± SED. *p<0.05; **p<0.01, significantly different from curcumin-untreated and each autophagy inhibitor-untreated control. #p<0.05; ##p<0.01, significantly different from curcumin-treated and each autophagy inhibitor-untreated control.

Curcumin-induced cell death was decreased by the autophagy inducer rapamycin

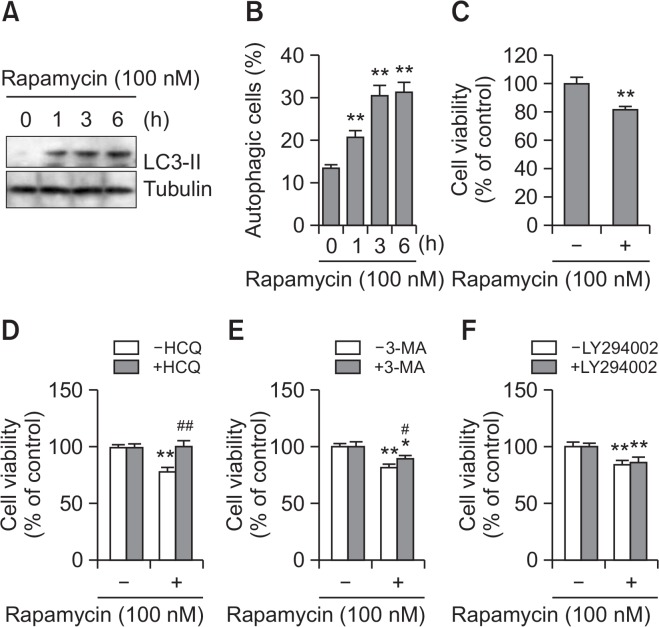

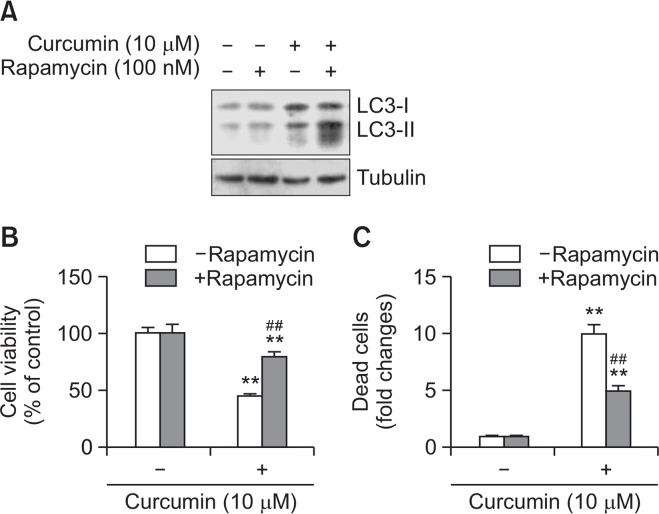

To confirm the role of autophagy in curcumin-mediated cell death, we examined the effects of the autophagy inducer rapamycin on A172 glioblastoma cell death (Arcella et al., 2013). As shown in Fig. 3, rapamycin treatment increased the amount of LC3-II (Fig. 3) and number of autophagic cells (Fig. 3B). Cell viability was decreased in rapamycin-treated cells (Fig. 3C). When cell death was determined with the trypan blue exclusion assay, rapamycin resulted in some increase (Fig. 3D, 3E) or little change (Fig. 3F) in cell death in the groups co-treated with HCQ (Fig. 3D), 3-MA (Fig. 3E), and LY294002 (Fig. 3F), compared with ∼20% in the rapamycin-treated group. This suggests that autophagy induction enhances rapamycin-mediated A172 glioblastoma cell death. We also examined the effect of rapamycin on curcumin-mediated cell death. Co-treatment with rapamycin and curcumin enhanced the amount of LC3-II (Fig. 4A). Cell viability with the MTT assay was ∼72% on co-treatment with curcumin and rapamycin versus ∼48% in the curcumin-treated group (Fig. 4B). When cell death was determined with the trypan blue exclusion assay, the fold change in curcumin-induced cell death decreased to ∼5.1 on pretreatment with rapamycin versus ∼9.9 in the curcumin-treated group (Fig. 4C). The data suggest that rapamycin-mediated enhancement of the basal level of autophagy decreased curcumin-induced tumor cell death.

Fig. 3.

Cell death was increased by the treatment with rapamycin, autophagy inducer. (A–C) A172 glioblastoma cells were treated with 100 nM rapamycin for 1, 3, and 6 h. Cell lysates were prepared and LC3 proteins were detected by western blotting (A). Autophagic cells with LC3 puncta were counted under fluorescence microscope with 1,000X magnification (B). Cell viability was measured by MTT assay as described in materials and methods (C). (D–F) A172 cells were treated with 100 nM rapamycin in the presence of autophagy inhibitors such as HCQ (D), 3-MA (E) or LY294002 (F) for 24 h. Then, cell viability was measured by MTT assay as described in materials and methods. Data in bar graph represent mean ± SED. *p<0.05; **p<0.01, significantly different from rapamycin-untreated and each autophagy inhibitor-untreated control. #p<0.05; ##p<0.01, significantly different from rapamycin-treated and each autophagy inhibitor-untreated control.

Fig. 4.

Rapamycin attenuated curcumin-induced cell death. (A) A172 glioblastoma cells were treated with 10 μM curcumin in the presence of 100 nM rapamycin, autophagy inducer. Cell lysates were prepared and LC3 proteins were detected by western blotting. (B, C) A172 cells were treated with 10 μM curcumin for 24 h. Then, cell viability was measured by MTT assay as described in materials and methods (B). Dead cells were estimated by trypan blue exclusion assay (C). Data in bar graph represent mean ± SED. **p<0.01, significantly different from curcumin-untreated and rapamycin-untreated control. ##p<0.01, significantly different from curcumin-treated and rapamycin-untreated control.

Curcumin-induced cell death was decreased by serum-deprived autophagy

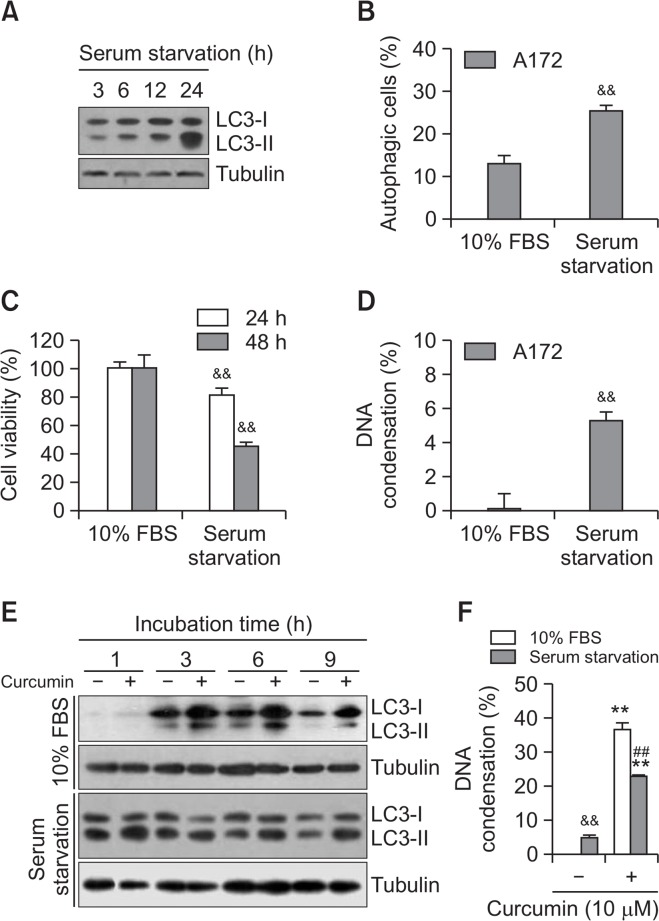

To confirm the effect of an increased basal level of autophagy on curcumin-mediated cell death, A172 cells were incubated under serum starvation. Time-dependent serum starvation enhanced the amount of LC3-II (Fig. 5A), which is consistent with the increase in autophagic cells with LC3 punta formation (Fig. 5B). With the MTT assay, cell viability was ∼85% and ∼45% on 24- and 48-h incubation under serum starvation, respectively (Fig. 5C). Cell death under serum starvation was confirmed by the increased in the percentage of cells with DNA condensation to 25% on 12 h incubation (Fig. 5D). Then, we examined the effect of serum starvation on curcumin-mediated cell death. When cells were treated with curcumin, the amount of LC3-II was time-dependently enhanced on incubation with 10% serum (Fig. 5E, top). However, few changes were observed on treatment with curcumin under serum starvation (Fig. 5E, bottom). With the trypan blue exclusion assay, the percentage of curcumin-treated cells with DNA condensation decreased to 23% on incubation under serum starvation versus 47% in the curcumin-treated group (Fig. 5F). This provides additional evidence that curcumin-induced glioblastoma cell death is reduced by enhancement of the basal level of autophagy under serum starvation.

Fig. 5.

Autophagy by serum starvation inhibited curcumin-induced cell death. (A) A172 glioblastoma cells were incubated under serum starvation for 3, 6, 12, 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared and LC3 proteins were detected by western blotting. (B) A172 cells were incubated under serum starvation for 6 h. Autophagic cells with LC3 puncta were counted under fluorescence microscope with 1,000X magnification (B). (C) A172 cells were incubated under serum starvation for 24 and 48 h. Then, cell viability was measured by MTT assay as described in materials and methods. (D) A172 cells were incubated under serum starvation for 12 h. DNA condensation was assessed by DAPI staining. (E, F) A172 cells were treated with 10 μM curcumin in the presence or absence of 10% serum for 1, 3, 6 and 9 h. Cell lysates were prepared and LC3 proteins were detected by western blotting (E). DNA condensation at 6 h was assessed by DAPI staining (F). Data in bar graph represent mean ± SED. &&p<0.01, significantly different from control in the presence of 10% serum (B–D, F). **p<0.01, significantly different from curcumin-untreated each control in the presence or absence of 10% serum (F). ##p<0.01, significantly different from curcumin-treated in the presence of 10% serum (F).

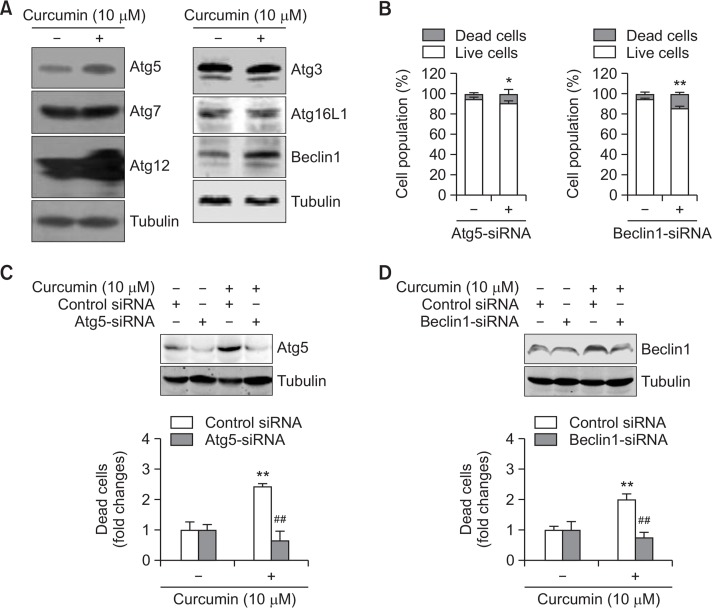

Curcumin-induced cell death is mediated by the autophagy proteins Atg5 and Beclin1

To determine which autophagy proteins are associated with curcumin-induced cell death, we observed the changes in Atg3, Atg5, Atg7, Atg12, Atg16L1, and Beclin1. Treatment with 10 μM curcumin for 3 h increased the Atg5, Atg12, and Beclin1 expression (Fig. 6A). When Atg5 or Beclin1 expression was inhibited by small interference RNA (siRNA), cell viability was reduced in the cells not treated with curcumin (Fig. 6B). The curcumin-induced expression of Atg5 and Beclin1 was also inhibited by Atg5-siRNA and Beclin1-siRNA, respectively (Fig. 6C and 6D, top). Using the trypan blue exclusion assay, the fold change in curcumin-induced cell death decreased to ∼0.7 on transfection with Atg5-siRNA versus ∼2.4 in the curcumin-treated group (Fig. 6C, bottom). The fold change in curcumin-induced cell death decreased to ∼0.8 on transfection with Beclin1-siRNA versus ∼3.6 in the curcumin-treated group (Fig. 6D, bottom). Therefore, curcumin-induced A172 glioblastoma cell death via autophagy is mediated by Atg5 and Beclin1.

Fig. 6.

Curcumin-induced cell death was reduced by the inhibition of autophagy proteins, Atg5 and Beclin1. (A, B) A172 glioblastoma cells were treated with 10 μM curcumin for 3 (A) and 6 (B) h. Cell lysates were prepared and each autophagy protein (Atg3, Atg5, Atg7, Atg12, Atg16L1 and Beclin1) was detected by western blotting (A). Dead cells were estimated by trypan blue exclusion assay (B). (C, D) Atg5 or Beclin1 proteins in A172 cells were reduced by the transfection with Atg5-siRNA (C) or Beclin1-siRNA (D) and the incubation for 24 h. Then, cells were treated with 10 μM curcumin for 3 (top) and 6 (bottom) h. Cell lysates were prepared and LC3 proteins were detected by western blotting (top). Dead cells were estimated by trypan blue exclusion assay (bottom). Data in bar graph represent mean ±SED. *p<0.05; **p<0.01, significantly different from control siRNA-treated (B) or curcumin-untreated (C, D) group. ##p<0.01, significantly different from curcumin-treated and control siRNA-treated group (C, D).

DISCUSSION

Glioblastoma is a devastating primary brain tumor that is resistant to conventional therapies (Zanotto-Filho et al., 2015). Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is among the most incurable neoplasms with the worst 5-year survival rates (Lefranc and Kiss, 2006; Tykocki and Eltayeb, 2018). Preclinical in vitro and in vivo data show that curcumin is effective for treating brain tumors, including GBM (Klinger and Mittal, 2016). Curcumin, derived from the turmeric rhizome, has therapeutic potential due to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiproliferative properties (Klinger and Mittal, 2016). Curcumin also induces autophagy and apoptosis in various human cancer cells (Zanotto-Filho et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017; Fu et al., 2018). Glioblastomas show cytoplasmic overexpression of autophagic proteins to varying extents (Giatromanolaki et al., 2014). Therefore, we investigated whether curcumin-induced autophagy contributes to the antitumor effects of curcumin on A172 human glioblastoma cells. We observed autophagy induction by curcumin. Our data showed that autophagy inhibitors reduced curcumin-induced cell death, which was also inhibited by co-incubation with an autophagy inducer or increased basal level of LC3 under serum starvation. Moreover, curcumin-induced cell death was inhibited by the inhibition of Atg5 or Beclin1 gene expression. The data showed that curcumin-induced autophagy could be beneficial in curcumin-mediated tumor cell death, but not via the increase in basal level of autophagy. Tumor cell death is influenced differently by antitumor agent-induced autophagy and the prerequisite level of autophagy in cancer cells. This suggests that clinicians should carefully regulate autophagy in brain tumor cells so as not to induce resistance to antitumor agents.

Under stress, both autophagy and apoptosis occur (Li et al., 2017); which of these processes may have the upper hand depending on the time and the strength of stimulation. Under stress, autophagy inhibits early cell death processes. If the stress continues, autophagy does not lead to the recovery of damaged organelles and dead cells increase (Marino et al., 2014; Cassel et al., 2017). Therefore, early regulation of autophagy can increase cell death induced by antitumor drugs (Zanotto-Filho et al., 2015). Our data showed that curcumin-induced autophagy enhanced the antitumor effects of curcumin.

Glioblastoma is resistant to conventional therapies and temozolomide is the most efficacious cytotoxic drug for glioblastoma, exerting its cytotoxic activity via proautophagic processes (Lefranc and Kiss, 2006). Curcumin inhibits gastric cancer cell proliferation and induces autophagy and apoptosis (Fu et al., 2018). Combining temozolomide with curcumin, autophagy reduced the efficacy of temozolomide/curcumin (Zanotto-Filho et al., 2015). Consequently, use of agents that interfere with autophagy may represent a new strategy to improve brain tumor treatment (Giatromanolaki et al., 2014). However, we found that agents interfering with autophagy inhibited curcumin-induced cell death.

Although three autophagy inhibitors (3-MA, LY294002, and HCQ) have a different mechanism of action, their inhibitory effects on curcumin-induced cytotoxicity look similar. HCQ inhibits the autophagic flux by reducing the fusion of autophagosome and lysosome (Mauthe et al., 2018). 3-MA inhibits the formation of autophagosome (Wu et al., 2010). LY294002 is a potent, cell permeable inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) that inhibit autophagic sequestration (Blommaart et al., 1997). So, our data suggest that curcumin could induce autophagy by acting on multi-sites of autophagy pathway. In the meanwhile, curcumin-induced cell death was decreased by the autophagy inducer rapamycin or by serum starvation, although rapamycin treatment and serum starvation enhanced the amount of LC3-II increased by curcumin. Then, the autophagy level enhanced by both conditions was called as the basal level of autophagy. It was distinguished from curcumin-induced autophagy, which increased cell death. Results suggest that the basal level of autophagy already induced by rapamycin or serum starvation decreased curcumin-induced glioblastoma cell death.

Curcumin is a promising compound, with low toxicity at large doses, which should be evaluated in clinical trials of the treatment of human brain tumors (Klinger and Mittal, 2016). The effects of curcumin are potentiated by G2/M cell cycle arrest, apoptotic activation, autophagy induction, signaling disturbance, and the inhibition of invasion and metastasis (Klinger and Mittal, 2016). Most important signaling pathways are controlled by PI3K, Akt, and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (Lefranc and Kiss, 2006). Tumor cell death induced by anticancer drugs is also regulated by various other signaling molecules, including JNK, Erk, c-myc, and NF-kB (Tashiro et al., 1998; Fan et al., 2000; Stadheim et al., 2001; Bressin et al., 2006; Calvino et al., 2015). Curcumin activates the P53 signaling pathway by up-regulating P53 and P21, which also inhibit the PI3K pathway by down-regulating PI3K, p-Akt, and p-mTOR (Fu et al., 2018). We observed the increased expression of Atg proteins (LC3-II, Beclin1, Atg12, and Atg5) in curcumin-treated cells. Our data also showed that Atg5-siRNA and Beclin1-siRNA inhibited curcumin-induced cell death. Therefore, the antitumor effects of curcumin in glioblastoma cells could be augmented by inducing autophagy. Although we did not clarify what signaling molecules are involved in the communication between autophagy and apoptosis in curcumin-induced cell death, autophagy regulation might be associated with the induction of drug resistance in glioblastoma cells.

In conclusion, we found that the antitumor activity of curcumin is associated with autophagy induction via the increased expression of Atg5 and Beclin1 in glioblastoma cells. This suggests that autophagy induction may be necessary for the antitumor activity of curcumin. It also suggests that a decrease in autophagy induced by other factors could inhibit the antitumor activity of curcumin, leading to the induction of drug resistance to antitumor agents. Therefore, patients who are to be treated with curcumin should be given autophagy modifiers. Care should also be taken to regulate autophagy so as not to induce resistance to antitumor agents by modifying autophagy in brain tumor cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the R&D program for Society of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science,ICT & Future Planning (Grant from Mid-career Researcher Program: #2016R1A2B4007446 and #2018R1A2A3075602), Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We wish to confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

REFERENCES

- Abdul Rahim SA, Dirkse A, Oudin A, Schuster A, Bohler J, Barthelemy V, Muller A, Vallar L, Janji B, Golebiewska A, Niclou SP. Regulation of hypoxia-induced autophagy in glioblastoma involves ATG9A. Br. J Cancer. 2017;117:813–825. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ak T, Gulcin I. Antioxidant and radical scavenging properties of curcumin. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;174:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand P, Thomas SG, Kunnumakkara AB, Sundaram C, Harikumar KB, Sung B, Tharakan ST, Misra K, Priyadarsini IK, Rajasekharan KN, Aggarwal BB. Biological activities of curcumin and its analogues (Congeners) made by man and Mother Nature. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;76:1590–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcella A, Biagioni F, Antonietta Oliva M, Bucci D, Frati A, Esposito V, Cantore G, Giangaspero F, Fornai F. Rapamycin inhibits the growth of glioblastoma. Brain Res. 2013;1495:37–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blommaart EF, Krause U, Schellens JP, Vreeling-Sindelarova H, Meijer AJ. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors wortmannin and LY294002 inhibit autophagy in isolated rat hepatocytes. Eur J Biochem. 1997;243:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.0240a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressin C, Bourgarel-Rey V, Carre M, Pourroy B, Arango D, Braguer D, Barra Y. Decrease in c-Myc activity enhances cancer cell sensitivity to vinblastine. Anticancer Drugs. 2006;17:181–187. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200602000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvino E, Tejedor MC, Sancho P, Herraez A, Diez JC. JNK and NFkappaB dependence of apoptosis induced by vinblastine in human acute promyelocytic leukaemia cells. Cell Biochem Funct. 2015;33:211–219. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassel M, de Paiva Camargo M, Oliveira de Jesus LW, Borella MI. Involution processes of follicular atresia and post-ovulatory complex in a characid fish ovary: a study of apoptosis and autophagy pathways. J Mol Histol. 2017;48:243–257. doi: 10.1007/s10735-017-9723-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codogno P, Mehrpour M, Proikas-Cezanne T. Canonical and non-canonical autophagy: variations on a common theme of self-eating? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;13:7–12. doi: 10.1038/nrm3249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan M, Goodwin M, Vu T, Brantley-Finley C, Gaarde WA, Chambers TC. Vinblastine-induced phosphorylation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL is mediated by JNK and occurs in parallel with inactivation of the Raf-1/MEK/ERK cascade. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29980–29985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Wang C, Yang D, Zhang X, Wei Z, Zhu Z, Xu J, Hu Z, Zhang Y, Wang W, Yan R, Cai Q. Curcumin regulates proliferation, autophagy and apoptosis in gastric cancer cells by affecting PI3K and P53 signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:4634–4642. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, Mitrakas A, Kalamida D, Zois CE, Haider S, Piperidou C, Pappa A, Gatter KC, Harris AL, Koukourakis MI. Autophagy and lysosomal related protein expression patterns in human glioblastoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15:1468–1478. doi: 10.4161/15384047.2014.955719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta KK, Bharne SS, Rathinasamy K, Naik NR, Panda D. Dietary antioxidant curcumin inhibits microtubule assembly through tubulin binding. FEBS J. 2006;273:5320–5332. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamori T, Lubet R, Steele VE, Kelloff GJ, Kaskey RB, Rao CV, Reddy BS. Chemopreventive effect of curcumin, a naturally occurring anti-inflammatory agent, during the promotion/progression stages of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59:597–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinger V, Mittal S. Therapeutic potential of curcumin for the treatment of brain tumors. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:9324085. doi: 10.1155/2016/9324085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunnumakkara AB, Anand P, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin inhibits proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis and metastasis of different cancers through interaction with multiple cell signaling proteins. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:199–225. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Park S, Kim SY, Um SH, Moon EY. Curcumin hampers the antitumor effect of vinblastine via the inhibition of microtubule dynamics and mitochondrial membrane potential in HeLa cervical cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 2016;23:705–713. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Ryu YK, Ji YH, Kang JH, Moon EY. Hypoxia/reoxygenation-experienced cancer cell migration and metastasis are regulated by Rap1- and Rac1-GTPase activation via the expression of thymosin beta-4. Oncotarget. 2015;6:9820–9833. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefranc F, Kiss R. Autophagy, the Trojan horse to combat glioblastomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20:E7. doi: 10.3171/foc.2006.20.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Zhou Y, Yang J, Li H, Zhang H, Zheng P. Curcumin induces apoptotic cell death and protective autophagy in human gastric cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2017;37:3459–3466. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino G, Niso-Santano M, Baehrecke EH, Kroemer G. Self-consumption: the interplay of autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:81–94. doi: 10.1038/nrm3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauthe M, Orhon I, Rocchi C, Zhou X, Luhr M, Hijlkema KJ, Coppes RP, Engedal N, Mari M, Reggiori F. Chloroquine inhibits autophagic flux by decreasing autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagy. 2018;14:1435–1455. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1474314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monastyrska I, Rieter E, Klionsky DJ, Reggiori F. Multiple roles of the cytoskeleton in autophagy. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2009;84:431–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan J, Zarrer J, Murphy BM. Targeting autophagy in glioblastoma. Crit Rev Oncog. 2016;21:241–252. doi: 10.1615/CritRevOncog.2016017008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu YK, Lee JW, Moon EY. Thymosin beta-4, actin-sequestering protein regulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression via hypoxia-inducible nitric oxide production in HeLa cervical cancer cells. Biomol. Ther (Seoul) 2015;23:19–25. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2014.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sa G, Das T. Anti cancer effects of curcumin: cycle of life and death. Cell Div. 2008;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K, Le N, Alotaibi M, Gewirtz DA. Cytotoxic autophagy in cancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:10034–10051. doi: 10.3390/ijms150610034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehzad A, Wahid F, Lee YS. Curcumin in cancer chemoprevention: molecular targets, pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and clinical trials. Arch. Pharm (Weinheim) 2010;343:489–499. doi: 10.1002/ardp.200900319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadheim TA, Xiao H, Eastman A. Inhibition of extra-cellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) mediates cell cycle phase independent apoptosis in vinblastine-treated ML-1 cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1533–1540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro E, Simizu S, Takada M, Umezawa K, Imoto M. Caspase-3 activation is not responsible for vinblastine-induced Bcl-2 phosphorylation and G2/M arrest in human small cell lung carcinoma Ms-1 cells. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1998;89:940–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1998.tb00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tykocki T, Eltayeb M. Ten-year survival in glioblastoma. A systematic review. J Clin Neurosci. 2018;54:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeran S, Shu B, Cui G, Fu S, Zhong G. Curcumin induces autophagic cell death in Spodoptera frugiperda cells. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2017;139:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilken R, Veena MS, Wang MB, Srivatsan ES. Curcumin: A review of anti-cancer properties and therapeutic activity in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:12. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Lao Y, Xu N, Wang X, Tan H, Fu W, Lin Z, Xu H. Guttiferone K induces autophagy and sensitizes cancer cells to nutrient stress-induced cell death. Phytomedicine. 2015;22:902–910. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YT, Tan HL, Shui G, Bauvy C, Huang Q, Wenk MR, Ong CN, Codogno P, Shen HM. Dual role of 3-methyl-adenine in modulation of autophagy via different temporal patterns of inhibition on class I and III phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10850–10861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.080796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang DH, Lee JW, Lee J, Moon EY. Dynamic rearrangement of F-actin is required to maintain the antitumor effect of trichostatin A. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e97352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao CW, Kang KA, Piao MJ, Ryu YS, Fernando P, Oh MC, Park JE, Shilnikova K, Na SY, Jeong SU, Boo SJ, Hyun JW. Reduced autophagy in 5-fluorouracil resistant colon cancer cells. Biomol. Ther (Seoul) 2017;25:315–320. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2016.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonekawa T, Thorburn A. Autophagy and cell death. Essays Biochem. 2013;55:105–117. doi: 10.1042/bse0550105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanotto-Filho A, Braganhol E, Klafke K, Figueiro F, Terra SR, Paludo FJ, Morrone M, Bristot IJ, Battastini AM, Forcelini CM, Bishop AJ, Gelain DP, Moreira JC. Autophagy inhibition improves the efficacy of curcumin/temozolomide combination therapy in glioblastomas. Cancer Lett. 2015;358:220–231. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Wang J, Xu J, Lu Y, Jiang J, Wang L, Shen HM, Xia D. Curcumin targets the TFEB-lysosome pathway for induction of autophagy. Oncotarget. 2016;7:75659–75671. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]