Abstract

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is a form of non-melanoma skin cancer responsible for more deaths in the USA than all other skin cancers combined. Some features, including anatomic site, are considered high risk in nature and pose a challenge for complete tumour removal. We present a case of a 62-year-old male surgeon with a multiply recurrent cSCC of the right conchal bowl. The tumour described herein was doubly recurrent to excision with a standard margin and could ultimately not be cleared with Mohs micrographic surgery. Ultimately, it necessitated auriculectomy and parotidectomy. This case exemplifies the pitfalls of traditional wide local excision with standard pathologic processing for high-risk cSCC.

Keywords: dermatology, skin cancer, surgical oncology, healthcare improvement and patient safety

Background

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most common skin cancer in the USA. These malignant neoplasms typically develop from long-term unprotected sun exposure, with ultraviolet (UV) solar radiation being the primary modifiable risk factor.1 cSCC, along with other skin cancers, is considered to be curable diseases with surgical removal being the primary treatment modality. While a variety of techniques may be used for removal of cSCC, only two utilise histological evaluation to confirm tumour clearance: standard wide local excision (WLE) and Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS).2 WLE entails the removal of a tumour with a standard peripheral margin, with postoperative analysis of frozen or paraffin-embedded bread-loafed tissue sections.3 MMS is a surgical technique that seeks to ensure the clearance of cSCC while sparing as much healthy tissue as possible.4 It is performed by the sequential removal of thin layers of tissue around a skin cancer, both peripherally and deep, which are then immediately transferred to the histopathology laboratory for processing.4 These specimens are flattened, frozen and tangentially sectioned, making it possible to evaluate 100% of the surgical margin for tumour clearance.4 The process is repeated until negative margins are achieved.

Compared with other sun-exposed sites, lesions on the ear are considered high risk and have an increased rate of morbidity and mortality. Lesions found in high-risk areas such as the ear often pose a challenge for tumour clearance and require complete histological removal to prevent recurrence. This report describes a case of a patient with a recurrent cSCC of the right conchal bowl, which failed standard WLE twice and ultimately necessitated parotidectomy and auriculectomy.

Case presentation

A 62-year-old man was referred to our centre in April of 2018 for evaluation and treatment of a recurrent invasive cSCC of the right conchal bowl. A year prior, in April of 2017, the tumour was treated twice by an outside provider with a standard WLE, in which pathology specimens were processed using bread-loafed frozen sections. While the synoptic report for the procedure did report clear margins, the exact millimetre clearance achieved was not noted by the pathologist and cannot be established. In January of 2018, an eschar-like lesion was noted in the right conchal bowl by his general dermatologist, who prescribed a 2-week course of topical 5-fluorouracil. The lesion did not resolve after this and was therefore rebiopsied by his general dermatologist in March of 2018 and found to be a recurrent invasive cSCC.

When he was referred for MMS in April of 2018, the patient was found to have a 2.5×1.5 cm hyperkeratotic plaque of the right conchal bowl causing conchal and retroauricular oedema (figure 1). No lymphadenopathy was appreciated during a cervical, postauricular, preauricular and submandibular lymph node exam.

Figure 1.

Initial presentation of a 2.5×1.5 cm eroded, hyperkeratotic papule.

Treatment

After two attempts to remove the tumour with standard WLE, MMS was recommended due to the need for complete surgical margin evaluation. After 2 days of MMS ending in May of 2018, a total of 32 tissue specimens were removed and microscopically evaluated, with a persistence of tumour in the deep surgical margins, extending into the external ear canal and surrounding soft tissue. Intraoperative histopathological analysis was unable to confirm any perineural invasion but did reveal widespread moderately differentiated squamous epithelial cells adjacent to small diameter nerves (figure 2). Due to the depth of tumour penetration, local anesthesia could no longer be adequately administered without severe discomfort, and the procedure was aborted (figure 3). He was referred to a head and neck surgeon and ultimately underwent a right-sided parotidectomy and auriculectomy, further dissection of 12 cervical and two parotid lymph nodes proving no metastasis and reconstruction with a left anterolateral thigh free flap (figure 4). The final histology report determined the tumour to be 2.5 cm in diameter, with a depth of invasion of 1.5 cm and perineural invasion present. Bony and lymphovascular invasion was not identified, and the surgical margins were deemed clear. The patient was staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (8th ed.) with a tumour, node, metastases (TNM) rating of T3N0M0. He finished a course of adjuvant radiotherapy to the right free flap area 5 months after repair.

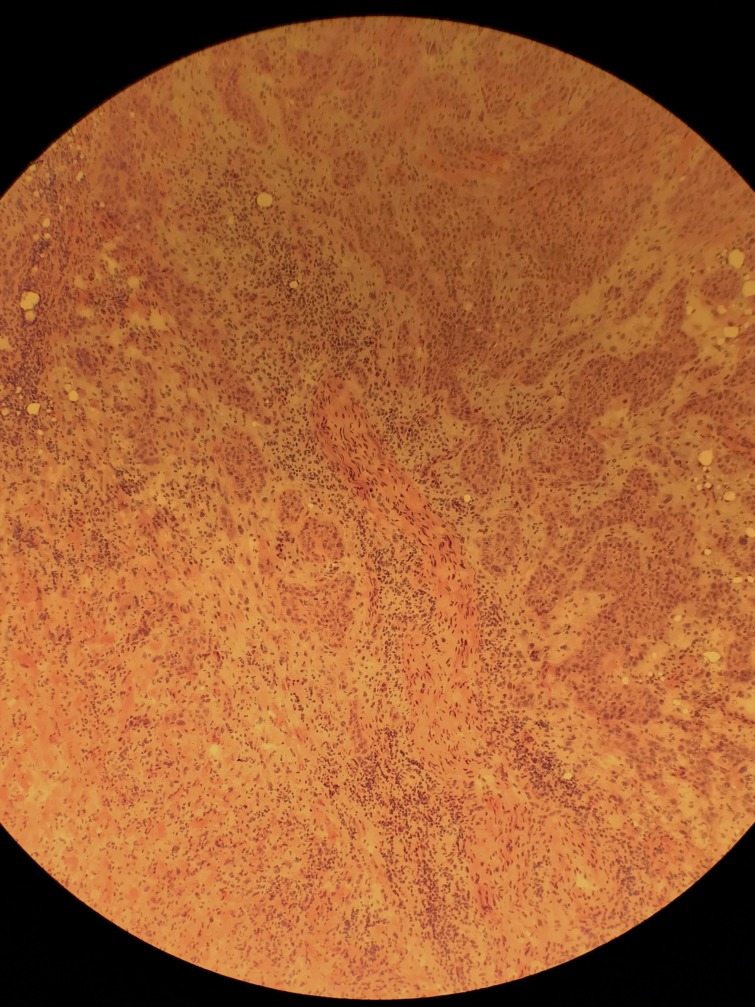

Figure 2.

Histopathology slide showing cord-like nests of moderately differentiated atypical squamous epithelial cells exhibiting eosinophilic cytoplasm adjacent to a small diameter nerve.

Figure 3.

Post-MMS defect. MMS, Mohs micrographic surgery.

Figure 4.

The patient s/p right auriculectomy and parotidectomy.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient is currently followed by his general dermatologist for total body skin examinations and lymph node exams every 6 weeks. He remains without any recurrences of cSCC on the right ear after 8 months, at the time of writing.

Discussion

cSCCs commonly present on the external ear and are believed to develop as a result of UV radiation–induced DNA mutations resulting from long-term unprotected sun-exposure.5 6 Furthermore, studies have shown a threefold higher risk of metastasis for cSCC of the external ear.7 This likely underpins the 4.67-fold increase in the risk ratio of disease-specific death associated with auricular cSCC.8Compared with other anatomical locations of the head, cSCC of the ear is associated with elevated rates of lymph node metastasis.9 In fact, cSCC of the ear carries an elevated absolute risk of 9% of lymph node metastasis compared with a baseline absolute risk of 5% for other sun-exposed sites.9

High-risk clinical and histological features of cSCC included a large tumour size (>2 cm), thick or deeply invasive lesion (>4 mm), recurrence, presence of perineural invasion (nerve diameter >0.1 mm), lymphovascular invasion, location near the parotid gland (ear, temple, forehead and anterior scalp) and immunosuppressed state.10 11 Our patient demonstrated five of the eight aforementioned risk factors. The high-risk nature of auricular cSCC is thought to be a function of thinner skin in this area, lack of subcutaneous fat and proximity to underlying cartilage.12

Proper and prompt management of auricular cSCC is necessary to avoid extensive morbidity. Currently, the standard of treatment for cSCC is complete surgical clearance with histologically clear margins.13 Standard practice in the USA by non-Mohs surgeons utilises a 4–6 mm margin of clinically normal-appearing skin as per the clinical guidelines provided by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).14 While this standard margin followed by bread-loaf sectioning is often used for these tumours, it has not been comprehensively studied on high-risk anatomic areas such as the ear. In contrast, numerous reports have demonstrated the value of complete margin examination on high-risk anatomic areas. Recently, a retrospective cohort study found that primary cSCC of the head and neck treated with MMS had a threefold lower risk of recurrence than those tumours treated with standard excision and bread-loaf pathologic processing when adjusted for tumour size and deep tumour invasion.15 The patient presented herein was treated with MMS after having been multiply recurrent to standard excision (twice) and chemotherapy.

While there are no head-to-head data directly comparing MMS to standard WLE among patients with high-risk auricular cSCC, studies have shown that recurrent cSCC, tumours with perineural invasion, poorly differentiated tumours and those with diameters greater than 2 cm all had lower recurrence rates with MMS when compared with standard WLE.8 This is likely due to the fact that MMS histological sectioning allows for examination of 100% of the margin compared with less than 1% of the margin visualised via standard bread-loaf vertical sectioning.13 Furthermore, bread-loaf vertical sectioning is subject to skip areas that are big enough for the tumour to remain undetected.13 On the contrary, MMS utilises tangential sectioning of frozen tissue samples in order to assess tumour presence in both the peripheral and deep margins simultaneously, precluding the creation of skip areas.13 For these reasons, MMS is considered the gold standard of care for high-risk cSCCs, which is supported by the NCCN in their 2018 guidelines.14 However, many of these high-risk tumours are still being primarily treated with excisions followed by bread-loaf sectioning.

In conclusion, this case illustrates the high-risk nature of auricular cSCCs as well as the downsides to incomplete histological evaluation for complicated tumours. A prospective comparative study would be beneficial in unifying surgical subspecialties towards a proven standard of surgical care for high-risk auricular cSCC.

Learning points.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is a common malignant neoplasm of the skin that typically develops from ultraviolet radiation–induced DNA damage resulting from long-term, unprotected sun exposure.

cSCC of the ear is considered a high-risk cSCC, as this location carries elevated rates of recurrence, metastasis and disease-related death.

High-risk cSCC should be treated primarily with a modality that utilises complete histological margin evaluation.

Footnotes

Contributors: JJ was involved in the patient’s care, gathered all data and wrote the case report. RDS was the patient’s surgeon and supervised his care, as well as critically reviewed the case report.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Watson M, Holman DM, Maguire-Eisen M. Ultraviolet radiation exposure and its impact on skin cancer risk. Semin Oncol Nurs 2016;32:241–54. 10.1016/j.soncn.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fahradyan A, Howell A, Wolfswinkel E, et al. . Updates on the management of non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC). Health Care 2017;5:82 10.3390/healthcare5040082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brodland DG, Zitelli JA. Surgical margins for excision of primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;27:241–8. 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70178-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pennington BE, Leffell DJ. Mohs micrographic surgery: established uses and emerging trends. Oncology 2005;19:1165–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ahmad I, Das Gupta AR. Epidemiology of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the pinna. J Laryngol Otol 2001;115:85–6. 10.1258/0022215011907497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rass K, Reichrath J. UV damage and DNA repair in malignant melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 2008;624:162–78. 10.1007/978-0-387-77574-6_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brantsch KD, Meisner C, Schönfisch B, et al. . Analysis of risk factors determining prognosis of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:713–20. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70178-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thompson AK, Kelley BF, Prokop LJ, et al. . Risk factors for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma recurrence, metastasis, and disease-specific death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol 2016;152:419–28. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.4994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. Implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992;26:976–90. 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70144-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Veness MJ. High-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Biomed Biotechnol 2007;2007:80572 10.1155/2007/80572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Karia PS, Morgan FC, Ruiz ES, et al. . Clinical and incidental perineural invasion of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and pooled analysis of outcomes data. JAMA Dermatol 2017;153:781–8. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beecher SM, Joyce CW, Elsafty N, et al. . Skin Malignancies of the Ear. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2016;4:e604 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abide JM, Nahai F, Bennett RG. The meaning of surgical margins. Plast Reconstr Surg 1984;73:492–7. 10.1097/00006534-198403000-00030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Squamous cell skin cancer. 2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/squamous.pdf

- 15. van Lee CB, Roorda BM, Wakkee M, et al. . Recurrence rates of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck after Mohs micrographic surgery vs. standard excision: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Dermatol 2019;181:338–43. 10.1111/bjd.17188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]