Abstract

Background

Rotator cuff disease is a widespread musculoskeletal pathology and a major cause of shoulder pain. Studies on familial predisposition suggest that genetic plays a role in the pathogenesis of rotator cuff disease. Several genes are responsible for rotator cuff disease. The aim of this study was to perform a systematic review on genetic association between rotator cuff disease and genes variations.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was performed, in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. PubMed, Medline, CINAHL, Cochrane, Embase and Google Scholar databases were searched comprehensively using the keywords: “Rotator cuff”, “Gene”, “Genetic”, “Predisposition”, “Single-nucleotide polymorphism” and “Genome-wide association”.

Results

8 studies investigating genes variations associated with rotator cuff tears were included in this review. 6 studies were case-control studies on candidate genes and 2 studies were GWASs. A significant association between SNPs and rotator cuff disease was found for DEFB1, FGFR1, FGFR3, ESRRB, FGF10, MMP-1, TNC, FCRL3, SASH1, SAP30BP, rs71404070 located next to cadherin8. Contradictory results were reported for MMP-3.

Conclusion

Further investigations are warranted to identify complete genetic profiles of rotator cuff disease and to clarify the complex interaction between genes, encoded proteins and environment. This may lead to individualized strategies for prevention and treatment of rotator cuff disease.

Level of evidence

Level IV, Systematic Review.

Keywords: Rotator cuff, Gene, Genetic, Shoulder, Predisposition

Background

Rotator cuff disease is a widespread musculoskeletal pathology and a major cause of shoulder pain [1]. This disabling condition has high prevalence, affecting 30–50% of the population older than 50 years of age [2]. Rotator cuff disease is a common health concern among working populations. The impact of this condition on earnings, missed workdays, and disability payments is relevant [2].

The etiology of rotator cuff disease is multifactorial [2–7] and its pathogenesis is not completely understood. In addition to aging, several factors can contribute to its etiopathogenesis, such as overuse, mechanical impingement, and smoking [3, 5, 8]. Studies on familial predisposition suggest that genetic plays a role in the pathogenesis of rotator cuff disease. Family members of patients with rotator cuff tears have a significantly higher risk of rotator cuff tears than general population [9, 10]. Tashjian et al. determined an increased risk of tears in family members of patients with rotator cuff tears that extends out and beyond third-cousin relationships [11]. Genetic predisposition may play a role also in clinical presentation and progression of rotator cuff tears. Genetically susceptible patients experience symptoms more often [12–15], in fact the relative risk of having a painful tear is 1.44 for siblings of a symptomatic patient [16]. These inheritable characteristics may affect any point of the sensorineural pathway. Moreover, the progression of a tear over a five-year period, is greater in siblings than in controls (tear size increased in 16.1% of siblings, compared with 1.5% of control group) [16].

Several genes are responsible for rotator cuff disease. Genetic susceptibility may affect the ultrastructure of the tendon. Achilles tendinopathy has been associated with polymorphisms of tenascin C and collagen type Va [17]. Similar mechanisms could play a role in the pathogenesis of rotator cuff disease. The genetic basis of this condition may also result from aberrations in the normal cell regulation of apoptosis and tissue regeneration.

The aim of this study was to perform a systematic review on genetic association between rotator cuff disease and candidate genes.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines with a PRISMA checklist and algorithm.

A comprehensive search of MEDLINE, PubMed, Cochrane, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Google Scholar databases using various combinations of the keywords: “Rotator cuff”, “Gene”, “Genetic”, “Predisposition”, “Genome-wide association”, “Single-nucleotide polymorphism” was performed. Three independent reviewers (U.G.L., V.C., and A.B.) conducted the search separately. All scientific journals were considered, and all relevant studies were analysed.

In order to qualify, an article must have been published in a peer-reviewed journal All articles were initially screened for relevance. The three investigators separately reviewed each abstract and completed a close reading of all articles to minimize selection bias and error. According to the Oxford Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine, only Level I to Level IV articles in English were included in our study.

We included articles that described genetic variations (single-nucleotide polymorphism, SNP) associated with rotator cuff disease. Both case-control studies focused on candidate genes and Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) were included. Studies should clearly describe the criteria used for the diagnosis of rotator cuff disease, genes and SNPs investigated. Missing data relevant to these parameters warranted exclusion from this systematic review. We did not included studies about familial predisposition, genetic variants and gene expression patterns associated with rotator cuff disease and/or healing. Literature reviews, case reports, animal and cadaveric studies, technical notes, letters to the editor, and instructional courses were excluded.

Finally, in order to avoid bias, the selected articles and their references, and the articles excluded from the study were reviewed, evaluated, and discussed by all the authors. All investigators independently extracted the type of study, number of cases and controls, diagnostic criteria of rotator cuff disease, investigated genes, mean age of cases and controls.

Quality assessment

We used the Coleman Methodology Score to assess the quality of the selected studies (CMS) [18], in which ten criteria are used to render a score ranging from 0 to 100 points (a score of 100 indicating a study that largely avoids chance, various biases, and confounding factors). The final score is defined as excellent (85 to 100 points), good (70 to 84 points), fair (50 to 69 points), and poor (< 50 points).

The subsections of the CMS are based on the subsections of the CONSORT statement outlined for randomized controlled trials, which have been modified to allow for other trial designs. Coleman criteria were subjected to modification in order to make them reproducible for this systematic review. Each study was scored by the three reviewers (U.G.L., V.C. and A.B) independently and in triplicate.

Results

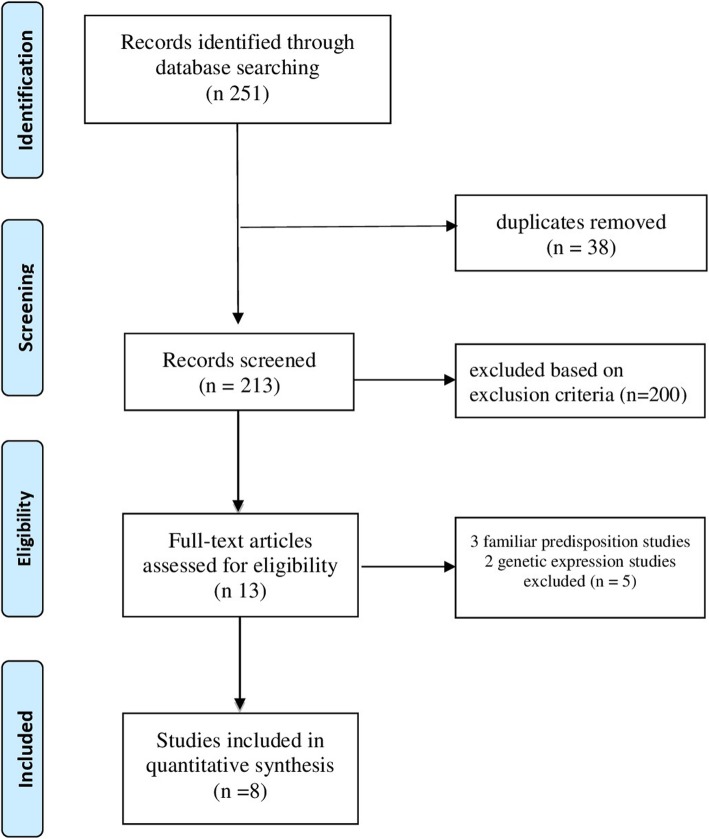

The literature search and the cross-referencing process resulted in 251 articles. 213 studies were assessed for relevance by title and abstract. 38 duplicates were removed and 200 were excluded because they did not meet inclusion criteria. After reading the remaining full-text articles, we rejected 3 studies about familial predisposition and 2 studies about genetic expression. Finally, 8 articles were included in the present review [19–26]. The flow-chart of literature search is shown in Fig. 1. Features of the studies are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2009 Flow diagram

Table 1.

Study features

| Author | Year | Type of Study | Cases | Controls | Diagnostic Criteria | Exclusion Criteria Case | Exclusion Criteria Control | Candidate Genes | Mean Age Group | Mean Age Control | Associated Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teerlink et al. [19] | 2015 | Case-control on candidate genes | 175 | 2595 | MRI | Partial-thickness rotator cuff tear, tendinopathy only, significant arthritis, prior surgery | – | DEFB1, DENND2C, ESRRB, FGF3, FGF10, FGFR1 | ESRRB (rs7157192) | ||

| Motta et al. [20] | 2015 | Case-control on candidate genes | 203 | 207 | Radiography and MRI | Older than 60 years and younger than 45 year, history of trauma, rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune syndrome, pregnancy, and use of corticosteroids. | History of shoulder pain, impingement syndrome, presence of tendinopathy in other joints | DEFB1, DENND2C, ESRRB, FGF3, FGF10, FGFR1 | 51,8 (+/−5,1) | 53,5 (+/− 5) | DEFB1, ESRRB (rs1676303), FGF3, FGF10, and FGFR1 |

| Tashjian et al. [25] | 2016 | GWAS | 311 | 2641 | MRI | Partial-thickness rotator cuff tear, tendinopathy only, significant glenohumeral arthritis, prior surgery | – | GWAS | – | – | SAP30BP on chromosome 17 (P = 3.8E-9), SASH1 on chromosome 6 (P = 1.9E-7) |

| Assunção et al. [21] | 2017 | Case-control on candidate genes | 64 | 64 | MRI (case) ultrasound (control) | age > 65 years, traumatic tears | – | MMP-1, MMP-3 | 54 ± 6 | 53 ± 6 | MMP-1, MMP-3 haplotype 2G/5A |

| Kluger et al. [22] | 2017 | case-control on candidate genes | 155 (first cohort: 59; second cohort: 96) | 76 (first cohort: 32; second, matched cohort 44) | Ultrasound | History of calcifying tendinitis, trauma or systemic disease/ inflammatory condition. | Prior operations of either shoulder, history of a humeral fracture or an infiltration or conservative shoulder treatment in the last 24 months or a systemic disease/inflammatory condition. | TNC, Col5A1, TIMP-1, MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9, and MMP-13 | – | – | TNC |

| Roos et al. [26] | 2017 | GWAS | 8357 | 94,622 | – | – | Complete rupture of rotator cuff, Infraspinatus sprain, Rotator cuff sprain, Subscapularis sprain, Supraspinatus sprain, Repair of ruptured rotator cuff (acute), Repair of ruptured rotator cuff (chronic), Reconstruction of complete rotator cuff avulsion, Shoulder arthroscopy with rotator cuff repair | GWAS | – | – | rs71404070 (next to Cadherin8) (P = 2.31 × 10− 8) |

| Longo et al. [27] | 2018 | Case-control | 93 | 206 | MRI | Primary osteoarthritis of the operated or contralateral shoulder, inflammatory joint disease. | History of shoulder pain or rotator cuff pathology diagnosed by imaging or clinical examination | col5a1 rs12722 | – | – | – |

| Salles et al. [28] | 2018 | Case-control | 146 | 125 | MRI | – | Tendinopathy history in any joint and who present no previous diagnosis of tendinopathy | FCRL3, FOXP3 | 26,93 +/− 6,03 | 21,62+/− 5,39 | FCRL3 |

Genetic variations

8 studies investigating genes variations associated with rotator cuff tears were included in this review. 6 studies were focused on candidate genes [19–24] and 2 studies were GWASs [25, 26].

The following candidate genes were investigated: DEFB1, DENND2C, ESRRB, FGF3, FGF10, FGFR1, MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9, MMP-13, Col5A1, TNC, FOXP3, FCRL3. A significant association between SNPs and rotator cuff disease was found for DEFB1, FGFR1, FGFR3, ESRRB, FGF10, MMP-1, TNC, FCRL3. Contradictory results were reported for MMP-3 [21, 22].

The two GWASs identified the following locus associated with rotator cuff tears: SASH1- rs12527089, SAP30BP - rs820218, rs71404070 located next to cadherin8 [25, 26].

Quality assessment

The mean CMS score was 71 points (range from 71 to 84), indicating that the methodological quality of the included studies was good. There was no statistically significant difference among the CMS values of the examiners.

Discussion

This systematic review outlines the current knowledge in the field of genetics in rotator cuff disease. Preliminary evidences of genetic and familiar predisposition to rotator cuff tears provided the basis for further studies that better highlight the importance of the genetic component in the pathogenesis of rotator cuff disease. In 2017, Dabija et al. [29] reviewed the literature on this topic describing the results of 4 studies investigating familiar predisposition and 3 studies investigating genes associated with rotator cuff tears. Up to day, we found other 5 studies focused on genetic variations associated with rotator cuff diseases. Even if the pathogenesis of rotator cuff disease is still largely unknown, recent studies on candidate genes and GWASs draw attention to SNPs associated with rotator cuff disease [27, 28, 30].

Several genes variations have been associated with rotator cuff tears. Interactions between genes, encoded proteins and environment play a complex role in the development of rotator cuff disease [35].

Motta et al. assessed 23 SNPs in 6 candidate genes (DEFB1, DENND2C, ESRRB, FGF3, FGF10, and FGFR1) in 203 cases and 207 controls [20]. The products of these genes are reported to have a role in tendon repair and degenerative processes. Rotator cuff disease was associated with certain haplotypes in DEFB1, FGFR1, FGFR3, and ESRRB. After adjustment by ethnic group and sex another association in FGF10 was revealed.

The association of variants in ESRRB and rotator cuff disease was further demonstrated by Teerlink et al. [19]. They identified high-risk haplotypes in the ESRRB gene comparing genotypes of 175 patients with rotator cuff tears with 2595 genetically-matched Caucasian controls. ESRRB is a protein-encoding gene classified as an orphan nuclear receptor, since its exact ligand is not known. It is involved in hearing loss [31], stem cell pluripotency [32], and cellular remodeling of energy consumption under conditions of hypoxia [33]. ESRRB induces hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) transcription, and their interaction may be involved in tenocyte apoptosis [34].

Several studies selected candidate genes on the basis of pre-existing association analyses for Achilles tendon ruptures (TNC, Col5A1, and MMP-3) [35–37], tendinopathies of the elbow (Col5A1) [38], ruptures of the posterior tibial tendon (MMP-1) [39] and matrix metalloproteinase genes MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9, MMP-13, TIMP-1 that are specifically expressed in torn rotator cuff.

Kluger et al. found no differences in genotype and allele frequencies for SNPs in MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9, MMP-13, and Col5A1 genes while six SNPs in Tenascin-C (TNC) were associated with degenerative rotator cuff tears [22]. Unlike their study, Assunção et al. [21] found a significant association between genetic polymorphism of MMP-3 and rotator cuff tearing that may be explained by the smaller number of individuals evaluated, nonpairing between cases and controls for age, and known risk factors such as high blood pressure, and racial and genetic characteristics of the population. Moreover, Assunção et al. studied a different polymorphism in MMP-1 (rs1799750) that was significantly associated with rotator cuff tearing.

In accordance with to Kluger et al. [22], no significant difference in allele and genotype frequencies of col5a1 was observed in the study by Longo et al. [23].

As demonstrated in in-vivo studies, the immune cells play a key role in the pathophysiology of rotator cuff tears. Salles et al. found an increased risk of tendinopathy associated with Fc receptor-like 3 polymorphism (FCRL3 − 169 T > C) [24]. FCRL3 is a glycoprotein of the immunoglobulin receptor superfamily, expressed in Treg cells that may play a role as a negative regulator of Treg function [40–42].

GWASs are a powerful tool to pinpoint genes that may contribute to the risk of developing rotator cuff disease. The GWAS by Tashjian et al. identified two significant SNPs associated with rotator cuff tears: SASH1 (rs12527089) and SAP30BP (rs820218) [25]. Those genes are associated with the cellular process of apoptosis. SASH1 is a tumor suppressor gene that is ubiquitous expressed and, therefore, may be a potential candidate for dysregulation in musculoskeletal tissue. SAP30BP is a ubiquitously present transcriptional regulator protein on chromosome 17. It may act as a transcriptional co-repressor of a gene related to cell survival [43].

In another GWAS, Ross et al. found a SNP located next to cadherin8 significantly associated with rotator cuff injury. It encodes a protein involved in cell adhesion [26].

Conclusion

Studies on candidate genes and GWASs identified several genes variation associated with rotator cuff tears, such as DEFB1, FGFR1, FGFR3, ESRRB, FGF10, MMP-1, TNC, FCRL3, SASH1, SAP30BP, rs71404070 located next to cadherin8.

Further investigations are warranted to identify complete genetic profile of rotator cuff disease and to clarify the complex interaction between genes, encoded proteins and environment. This may lead to individualized strategies for prevention and treatment of rotator cuff disease.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CINAHL

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- CMS

Coleman Methodology Score

- Col5A1

Collagen type V alpha 1 chain

- DEFB1

b-defensin protein

- DENND2C

DENN Domain Containing 2C

- ESRRB

Estrogen-related receptor-b

- FCRL3

FC-receptor-like 3

- FGF

Fibroblast growth factors

- FGFR

Fibroblast growth factors receptor

- FOXP3

Forkhead box P3

- GWASs

Genome-wide association studies

- HIF

Hypoxia-inducible factor

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinases

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SAP30BP

SAP30-binding protein

- SNP

Single-nucleotide polymorphism

- TNC

Tenascin-C

Authors’ contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript. UGL: manuscript preparation, study design, database interpretation and manuscript revision. VC and AB: manuscript preparation, database interpretation and statistical analysis. AG, GS and AN: manuscript preparation, figures and tables preparation, study design. JDA: Manuscript preparation and database interpretation. VD: Study design, manuscript revision.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

UGL is a member of the Editorial Board of BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Umile Giuseppe Longo, Phone: + 39 06 225411, Email: g.longo@unicampus.it.

Vincenzo Candela, Email: v.candela@unicampus.it.

Alessandra Berton, Email: a.berton@unicampus.it.

Giuseppe Salvatore, Email: g.salvatore@unicampus.it.

Andrea Guarnieri, Email: a.guarnieri@unicampus.it.

Joseph DeAngelis, Email: submission.cbm@gmail.com.

Ara Nazarian, Email: submission.cbm@gmail.com.

Vincenzo Denaro, Email: denaro.cbm@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Goodier HC, Carr AJ, Snelling SJ, Roche L, Wheway K, Watkins B, Dakin SG. Comparison of transforming growth factor beta expression in healthy and diseased human tendon. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:48. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-0947-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longo UG, Salvatore G, Rizzello G, Berton A, Ciuffreda M, Candela V, Denaro V. The burden of rotator cuff surgery in Italy: a nationwide registry study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2017;137(2):217–224. doi: 10.1007/s00402-016-2610-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Longo UG, Berton A, Papapietro N, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Epidemiology, genetics and biological factors of rotator cuff tears. Med Sport Sci. 2012;57:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000328868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Del Buono A, Oliva F, Longo UG, Rodeo SA, Orchard J, Denaro V, Maffulli N. Metalloproteases and rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2012;21(2):200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longo UG, Petrillo S, Rizzello G, Candela V, Denaro V. Deltoid muscle tropism does not influence the outcome of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Musculoskelet Surg. 2016;100(3):193–198. doi: 10.1007/s12306-016-0412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Longo UG, Forriol F, Campi S, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Animal models for translational research on shoulder pathologies: from bench to bedside. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2011;19(3):184–193. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e318205470e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Longo UG, Franceschi F, Ruzzini L, Rabitti C, Morini S, Maffulli N, Forriol F, Denaro V. Light microscopic histology of supraspinatus tendon ruptures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(11):1390–1394. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0395-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linaker CH, Walker-Bone K. Shoulder disorders and occupation. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29(3):405–423. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tashjian RZ, Hollins AM, Kim HM, Teefey SA, Middleton WD, Steger-May K, Galatz LM, Yamaguchi K. Factors affecting healing rates after arthroscopic double-row rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(12):2435–2442. doi: 10.1177/0363546510382835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamaguchi K, Ditsios K, Middleton WD, Hildebolt CF, Galatz LM, Teefey SA. The demographic and morphological features of rotator cuff disease. A comparison of asymptomatic and symptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1699–1704. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tashjian RZ, Farnham JM, Albright FS, Teerlink CC, Cannon-Albright LA. Evidence for an inherited predisposition contributing to the risk for rotator cuff disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(5):1136–1142. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvie P, Ostlere SJ, Teh J, McNally EG, Clipsham K, Burston BJ, Pollard TC, Carr AJ. Genetic influences in the aetiology of tears of the rotator cuff. Sibling risk of a full-thickness tear. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86(5):696–700. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B5.14747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberti M, Mustich A, Gadaleta MN, Cantatore P. Identification of two homologous mitochondrial DNA sequences, which bind strongly and specifically to a mitochondrial protein of Paracentrotus lividus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19(22):6249–6254. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.22.6249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foulkes T, Wood JN. Pain genes. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(7):e1000086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buskila D. Genetics of chronic pain states. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21(3):535–547. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gwilym SE, Watkins B, Cooper CD, Harvie P, Auplish S, Pollard TC, Rees JL, Carr AJ. Genetic influences in the progression of tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg. 2009;91(7):915–917. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B7.22353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Longo UG, Ronga M, Maffulli N. Acute ruptures of the achilles tendon. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2009;17(2):127–138. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e3181a3d767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, Gotzsche PC, Lang T, Consort G. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(8):663–694. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teerlink CC, Cannon-Albright LA, Tashjian RZ. Significant association of full-thickness rotator cuff tears and estrogen-related receptor-beta (ESRRB) J Shoulder Elbow Surg/ American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al] 2015;24(2):e31–e35. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motta Gda R, Amaral MV, Rezende E, Pitta R, Vieira TC, Duarte ME, Vieira AR, Casado PL. Evidence of genetic variations associated with rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(2):227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Assuncao JH, Godoy-Santos AL, Dos Santos M, Malavolta EA, Gracitelli MEC, Ferreira Neto AA. Matrix metalloproteases 1 and 3 promoter gene polymorphism is associated with rotator cuff tear. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(7):1904–1910. doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kluger R, Burgstaller J, Vogl C, Brem G, Skultety M, Mueller S. Candidate gene approach identifies six SNPs in tenascin-C (TNC) associated with degenerative rotator cuff tears. J Orthop Res. 2017;35(4):894–901. doi: 10.1002/jor.23321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Longo UG, Margiotti K, Petrillo S, Rizzello G, Fusilli C, Maffulli N, De Luca A, Denaro V. Genetics of rotator cuff tears: no association of col5a1 gene in a case-control study. BMC Med Genet. 2018;19(1):217. doi: 10.1186/s12881-018-0727-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salles JI, Lopes LR, Duarte MEL, Morrissey D, Martins MB, Machado DE, Guimaraes JAM, Perini JA. Fc receptor-like 3 (−169T>C) polymorphism increases the risk of tendinopathy in volleyball athletes: a case control study. BMC Med Genet. 2018;19(1):119. doi: 10.1186/s12881-018-0633-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tashjian RZ, Granger EK, Farnham JM, Cannon-Albright LA, Teerlink CC. Genome-wide association study for rotator cuff tears identifies two significant single-nucleotide polymorphisms. J Shoulder Elbow Surg/ American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al] 2016;25(2):174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roos TR, Roos AK, Avins AL, Ahmed MA, Kleimeyer JP, Fredericson M, Ioannidis JPA, Dragoo JL, Kim SK. Genome-wide association study identifies a locus associated with rotator cuff injury. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0189317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Longo UG, Berton A, Khan WS, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Histopathology of rotator cuff tears. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2011;19(3):227–236. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e318213bccb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denaro V, Ruzzini L, Longo UG, Franceschi F, De Paola B, Cittadini A, Maffulli N, Sgambato A. Effect of dihydrotestosterone on cultured human tenocytes from intact supraspinatus tendon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(7):971–976. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0953-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dabija DI, Gao C, Edwards TL, Kuhn JE, Jain NB. Genetic and familial predisposition to rotator cuff disease: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg/ American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al] 2017;26(6):1103–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denaro V, Ruzzini L, Barnaba SA, Longo UG, Campi S, Maffulli N, Sgambato A. Effect of pulsed electromagnetic fields on human tenocyte cultures from supraspinatus and quadriceps tendons. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90(2):119–127. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181fc7bc7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ben Said M, Ayedi L, Mnejja M, Hakim B, Khalfallah A, Charfeddine I, Khifagi C, Turki K, Ayadi H, Benzina Z, et al. A novel missense mutation in the ESRRB gene causes DFNB35 hearing loss in a Tunisian family. Eur J Med Genet. 2011;54(6):e535–e541. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Laan S, Tsanov N, Crozet C, Maiorano D. High Dub3 expression in mouse ESCs couples the G1/S checkpoint to pluripotency. Mol Cell. 2013;52(3):366–379. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lundgreen K, Lian O, Scott A, Engebretsen L. Increased levels of apoptosis and p53 in partial-thickness supraspinatus tendon tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(7):1636–1641. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Millar NL, Reilly JH, Kerr SC, Campbell AL, Little KJ, Leach WJ, Rooney BP, Murrell GA, McInnes IB. Hypoxia: a critical regulator of early human tendinopathy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(2):302–310. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.154229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mokone GG, Gajjar M, September AV, Schwellnus MP, Greenberg J, Noakes TD, Collins M. The guanine-thymine dinucleotide repeat polymorphism within the tenascin-C gene is associated with achilles tendon injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(7):1016–1021. doi: 10.1177/0363546504271986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saunders CJ, van der Merwe L, Posthumus M, Cook J, Handley CJ, Collins M, September AV. Investigation of variants within the COL27A1 and TNC genes and Achilles tendinopathy in two populations. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(4):632–637. doi: 10.1002/jor.22278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.September AV, Cook J, Handley CJ, van der Merwe L, Schwellnus MP, Collins M. Variants within the COL5A1 gene are associated with Achilles tendinopathy in two populations. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(5):357–365. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.048793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altinisik J, Meric G, Erduran M, Ates O, Ulusal AE, Akseki D. The BstUI and DpnII variants of the COL5A1 gene are associated with tennis elbow. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1784–1789. doi: 10.1177/0363546515578661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Godoy-Santos A, Cunha MV, Ortiz RT, Fernandes TD, Mattar R, Jr, dos Santos MC. MMP-1 promoter polymorphism is associated with primary tendinopathy of the posterior tibial tendon. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(7):1103–1107. doi: 10.1002/jor.22321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swainson LA, Mold JE, Bajpai UD, McCune JM. Expression of the autoimmune susceptibility gene FcRL3 on human regulatory T cells is associated with dysfunction and high levels of programmed cell death-1. J Immunol. 2010;184(7):3639–3647. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chistiakov DA, Chistiakov AP. Is FCRL3 a new general autoimmunity gene? Hum Immunol. 2007;68(5):375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagata S, Ise T, Pastan I. Fc receptor-like 3 protein expressed on IL-2 nonresponsive subset of human regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182(12):7518–7526. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meng Q, Zheng M, Liu H, Song C, Zhang W, Yan J, Qin L, Liu X. SASH1 regulates proliferation, apoptosis, and invasion of osteosarcoma cell. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;373(1–2):201–210. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article.