Abstract

A 62-year-old man with essential hypertension and right L4-L5 hemilaminectomy was referred to rheumatology for evaluation of severe arthralgia and myalgia for 12 months. Review of symptoms was significant for night sweats and 20 pounds unintentional weight loss. Physical examination was significant for holosystolic murmur best heard at the cardiac apex of unclear chronicity. Laboratory investigations revealed elevated inflammatory markers, white blood cell count and B-type natriuretic peptide. Transoesophageal echocardiogram showed flail posterior mitral leaflet with severe mitral regurgitation and two vegetations (2.5×1 cm and 1.6×0.3 cm). Abdominal CT showed new focal splenic infarcts, and a brain MRI revealed subacute infarcts, consistent with the embolic phenomenon. Blood cultures grew Granulicatella elegans. The patient underwent mitral valve replacement surgery followed by 6 weeks of parenteral therapy with vancomycin and gentamicin, with full recovery at a 3-month follow-up.

Keywords: valvar diseases, infections, infectious diseases

Background

Infective endocarditis (IE) is associated with high morbidity and mortality. Diagnosis of IE can be challenging as symptoms can be non-specific and echocardiography is generally necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis. Nutritionally variant streptococci (NVS) are fastidious microorganisms that are well-recognised, although uncommon, cause of IE, accounting for <5% of IE cases.1–3 Granulicatella spp, part of the NVS, are a rare but life-threatening cause of IE. Due to the fastidious nature of the organism and vague symptoms, the diagnosis of IE may be delayed, leading to the formation of large, bulky vegetations and consequent embolic lesions to the brain and other organs.4 Arthralgia and myalgia as the primary presenting symptom of Granulicatella IE have not been described in the literature. It is critical to expanding the differential diagnoses of patients presenting with non-specific joint pain, fever, and a murmur of unclear chronicity, to include IE.

Case presentation

A 62-year-old man with a medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and right laminectomy for L4-L5 foraminal narrowing (2 months prior to symptom onset), presented with progressive arthralgias, generalised weakness and malaise over the last 1 year. He reported multiple painful joints including hands, knees and ankles and had associated stiffness and mild swelling in these joints without associated erythema. He had seen multiple primary care physicians for these symptoms and had been prescribed with several courses of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and prednisone, which provided minimal relief. Hence was referred to the rheumatology clinic for evaluation at our institution. The nature of the joint pain was dull and continuous, with an intensity of 5/10. It was aggravated with activity and improved only temporarily with NSAIDS (nabumetone and celecoxib). He did not report any symptoms of jaw claudication, temple tenderness, scalp sensitivity, visual disturbance or headaches. He did not have any difficulty raising his arms above the horizontal or standing from a sitting position to suggest proximal muscle weakness.

The patient had been experiencing progressive, exertional shortness of breath over the last 6 months. During this time, he also had occasional, documented fevers of up to 40°C associated with night sweats and chills. He reported a 20 pounds unintentional weight loss over the past 2 months. He denied any chest pain, focal weakness, orthopnoea or new rashes. Review of symptoms in rheumatology clinic was remarkable for intermittent, self-limited, left-sided non-radiating, 5/10 abdominal pain for last 1 day, with no alleviating or aggravating factors. He did have three episodes of non-bloody, non-bilious emesis associated with the pain. There was no significant medication or travel history and patient did not report any recent dental procedures.

On examination, the patient was alert, oriented to time, place and person and in no acute distress. Vital signs revealed a temperature of 36.4°C and a blood pressure of 129/69 mm Hg. The musculoskeletal examination revealed normal-appearing joints with no acute swelling, warmth or redness. He had no pain with a full range of motion. His gait was normal. No scalp tenderness or any focal motor or sensory deficits were reported on the examination. Auscultation of the heart revealed a normal S1 and S2, and a 4/6 ejection holosystolic murmur best heard at the cardiac apex radiating to the axilla of unclear chronicity. Oral cavity examination revealed no missing teeth, gingival inflammation or dental plaque. The rest of the examination was normal, and there were no peripheral signs of endocarditis. The presence of a holosystolic murmur prompted evaluation with transthoracic echocardiogram and referral to cardiology.

Investigations

Laboratory investigations revealed a haemoglobin of 10 g/dL (13.2–16.6 g/dL), white count of 10.7x109/L (3.4–9.6×109/L), platelet 283×10(9)/L (135–317×109/L), sodium 137 mmol/L (135–145 mmol/L), potassium 4.6 mmol/L (3.6–5.2 mmol/L), calcium 9.5 mg/dL (8.8–10.2 mg/dL), B-type natriuretic peptide of 732 pg/mL (<82 pg/mL), aspartate aminotransferase 17 U/L (8–48 U/L), alanine aminotransferase 13 U/L (7–55 U/L) and serum creatinine 0.9 mg/dL (0.8–1.3 mg/dL). Urinalysis showed only trace haemoglobin. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated at 49 mm/1 hour (0–22 mm/1 hour), but the remaining rheumatological workup was negative including C reactive protein 3.0 mg/L (<8 mg/L), rheumatoid factor <15 IU/mL (<15 IU/mL), anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibody 15.6 U (<20 U), and antinuclear antibody 0.2 U (<1.0 U).

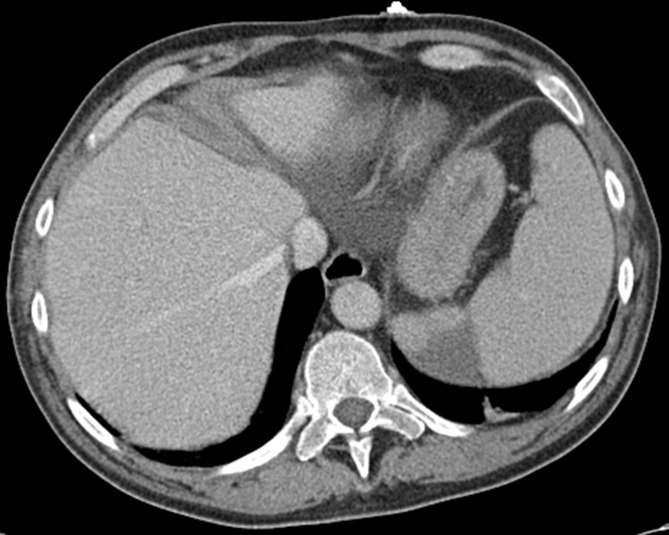

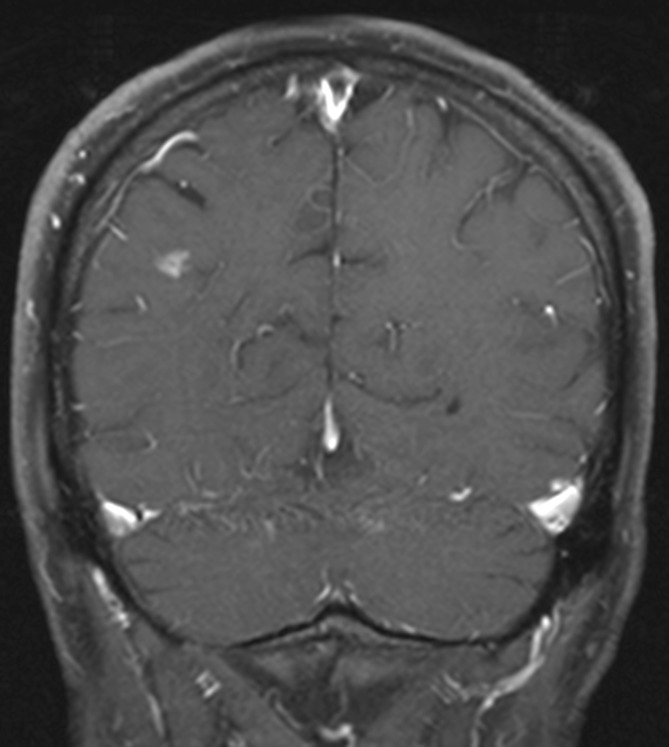

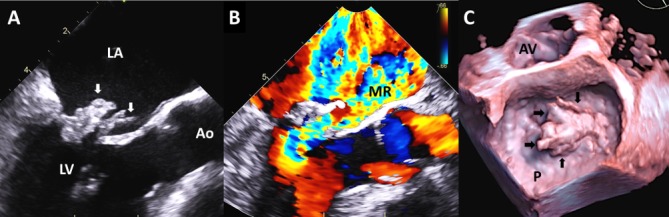

Transoesophageal echocardiogram (figure 1) revealed flail posterior mitral leaflet and one large vegetation (2.5×1 cm) on the posterior leaflet and a smaller (1.6×0.3 cm) vegetation on the anterior leaflet (video 1 and 2) with severe mitral regurgitation (video 3), and an EF of 66%. Additionally, there were vegetations attached on the chordae in the left ventricle measuring at least 1.6×0.5 cm in the ventricular side. Abdominal CT (figure 2) was remarkable for new focal splenic infarcts, and a brain (MRI) (figure 3) revealed subacute infarcts, consistent with the embolic phenomenon. A diagnostic panorex X-ray showed no definite periapical lucencies or fractures. In order to investigate low back, knees and ankles pain, the patient underwent an MRI of the lumbar spine and lower extremities, which failed to identify any signs of metastatic complications such as osteomyelitis, epidural abscess or septic arthritis.

Figure 1.

Transoesophageal echocardiogram (Panel A). Long-axis midoesophageal systolic still-frame showing a flail posterior leaflet (left arrow) and large, bulky echodensity measuring 2.5×1 cm on the posterior leaflet (left arrow), which likely represent leaflet tissue and vegetation. There is a linear, highly mobile echodensity 1.6×0.3 cm on the anterior leaflet (right arrow) also consistent with vegetation. (Panel B) Same view as panel A with colour Doppler showing torrential mitral regurgitation with anteriorly directed regurgitant jet that occupies most of the left atrium. (Panel C) 3D ‘surgeon’s view’ systolic still-frame of the mitral valve from the left atrial side showing a very large prolapsing mass (arrows) associated with the posterior leaflet (P). Ao, aorta, AV, aortic valve; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle.

Video 1.

Corresponds to figure 1A. Note flail posterior leaflet with large posterior leaflet vegetation and linear anterior leaflet vegetation. No evidence of perivalvular extension of infection.

Video 2.

Corresponds to figure 1C. Left, 2D orthogonal biplane views of the mitral valve. Right, 3D surgeon’s view showing the very large posterior leaflet mass.

Video 3.

Corresponds to figure 1B. Note torrential wide-open mitral regurgitation by colour Doppler.

Figure 2.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis. A new focal peripheral wedge-shaped area of hypoattenuation involving the spleen likely represents sequelae of an embolic infarct.

Figure 3.

MR of the brain. Several linear enhancing T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintense lesions involving the right posterior parietal and occipital cortex and the right cerebellum consistent with the embolic phenomenon.

Two sets of blood cultures drawn on admission grew a Gram-positive coccus, resembling streptococcus, at 16 hours, which was subsequently identified as Granulicatella elegans. Repeat blood cultures at 48 hours were negative. The isolate was sent to Quest Diagnostics for susceptibility testing and was found to be a pan-sensitive organism with following minimal inhibitory concentration (MICs): cefepime ≤0.5 µg/mL (S), ceftriaxone ≤0.12 µg/mL (S) S, chloramphenicol 4 µg/mL (S), clindamycin ≤0.12 µg/mL (S), erythromycin ≤0.25 µg/mL (S), levofloxacin 1 µg/mL (S), meropenem ≤0.25 µg/mL (S), penicillin ≤0.03 µg/mL (S) and vancomycin 1 µg/mL (S) which was reported 4 weeks following dismissal.

Pathology was not concomitantly obtained. Cultures of the extracted valve tissue were negative.

Treatment

The patient was empirically started on an antibiotic regimen (IV ceftriaxone and vancomycin) for mitral and aortic valve IE, pending antibiotic susceptibility data. Repeat blood cultures at 48 hours were negative. The patient underwent mitral valve replacement surgery which revealed a severely damaged mitral valve, especially the posterior leaflet, P2 scallop and infection extended all the way to the annulus with the formation of small abscesses. The anterior mitral leaflet, subvalvular apparatus and the posterior surface of the non-coronary cusp of the aortic had multiple vegetations. The patient underwent mitral valve replacement and aortic valve vegetectomy. Following this, he received 6 weeks of parenteral therapy with vancomycin and gentamicin.

Outcome and follow-up

At a 3-month follow-up visit, the patient reported resolution of all non-specific symptoms including joint pains and muscle aches with the exception of mild lower back pain. A follow-up echocardiogram showed normal ejection fraction (56%) with a trivial prosthetic mitral valve regurgitation. Surveillance blood cultures 72 hours after discontinuing antimicrobial therapy were negative.

Discussion

NVS were first described in 1961 by Frenkel and Hirsch5 as fastidious Gram-positive cocci that depend on pyridoxal or cysteine for growth in standard blood culture media. NVS are divided into two different genera, Abiotrophia and Granulicatella. NVS has been reported to cause between 5% and 6% of all cases of streptococcal endocarditis, and about 8% of NVS isolates have been reported to be G. elegans. 4

Granulicatella and Abiotrophia are normal flora of the oral mucosa, urogenital and intestinal tracts in humans.6 The most recent classification of the Granulicatella genus based on the 16S rRNA gene sequencing7 is G. adiacens, G. elegans and G. balaenopterae. Among this group, G. elegans is considered the most fastidious, requiring L-cysteine hydrochloride for growth.4 Granulicatella spp have been known to cause severe infections in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed hosts including IE, but due to their fastidious nature, they are often misdiagnosed as culture-negative endocarditis. Published case reports of IE due to Granulicatella spp is associated with poor outcomes. A recent study8 reported a mortality rate of 17% with embolic complications in 30% and perivalvular abscesses in 11% of the patients with IE due to Granulicatella spp.

Granulicatella elegans is a rare cause of IE.4 7 9–11 This organism is part of the human oral mucosa and a frequent cause of dental plaque, and hence, invasive dental procedures are a potential source for developing IE due to this organism.7 However, frequently, there are no specific risk factors that can be identified. Our patient did not report any recent dental procedure prior to symptom onset.

Clinical presentation of IE due to G. elegans can be non-specific. Majority of patients present with a history of constitutional symptoms such as weight loss, anorexia and fever for a few months, followed by heart failure or embolism.8 12 Our patient had prominent joint symptom and muscles aches for months before developing other constitutional symptoms and hence was initially referred to rheumatology for evaluation. The presence of a murmur and echocardiographic evidence of vegetations led to the diagnosis of IE, after being undiagnosed for months. This particular association of arthralgia and myalgia as primary presenting symptoms of IE due to G. elegans has not been previously reported in the literature. Some patients develop musculoskeletal symptoms due to metastatic seeding of bone and joints, with the most common site of involvement being the vertebrae.13 However, imaging was negative for bone and joint infection in our patient. Therefore, these manifestations could be immune-mediated. Previous studies have described the presence of positive rheumatoid factor and elevation of gamma globulin, though they do not clearly correlate with symptoms, and therefore their role in pathogenesis is unclear.14

Aortic and mitral valves are most frequently infected valve with Granulicatella spp. A recent review of 29 cases of Granulicatella spp endocarditis by Adam et al 8 reported aortic valve to be the most commonly involved valve, and multivalvular involvement was observed in 13% of patients. These organisms tend to form large, bulky vegetations, perhaps due to delay in diagnosis, and are associated with a high risk of embolic complications (up to 49% in one series). In our case, the diagnosis of G. elegans IE was made based on positive blood cultures. Identification of G. elegans in cultures can be difficult because of its fastidious growth and pleomorphism. Accurate identification may require a combination of special culture media including L-cysteine combined with 16S rRNA gene sequencing.7

The American Heart Association guidelines15 suggest combination therapy with ampicillin or penicillin G plus gentamicin for 4–6 weeks or vancomycin as an alternative regimen for IE due to Granulicatella spp. Prolonged antimicrobial therapy combined with valve replacement surgery (as performed in our case) is frequently required to cure these infections. IE caused by the NVS group as a whole has been reported to have treatment failure rates of 41%, despite the organisms being sensitive to the antibiotics used.16 This high clinical failure rate may be attributed to penicillin tolerance or a delay in isolating and identifying the organism, or also a delay in the initiation of appropriate antibiotics. Due to variable in vitro susceptibility results and high rates of penicillin and ceftriaxone resistance in NVS,17 some clinicians prefer to use vancomycin-based regimens for treating IE due to these organisms.

In summary, we describe an unusual case of IE caused by G. elegans that presented primarily with arthralgias and myalgias, in which consideration of only rheumatologic conditions at initial presentation caused a significant delay in the diagnosis. The patient had a holosystolic murmur on physical examination, but it was not further investigated. Providers should expand the differential diagnoses of patients presenting with new-onset musculoskeletal symptoms of unclear aetiology, especially if associated with fever and a cardiac murmur on examination and should consider endocarditis due to fastidious organisms in their evaluation.

Learning points.

Arthralgia and myalgia can be the primary presenting symptom of infective endocarditis due to Granulicatella spp for which a high index of suspicion is necessary for early diagnosis.

Delay in diagnosis is associated with the formation of bulky vegetations leading to systemic embolisation and significant damage to valvular apparatus requiring valve replacement surgery.

Reliable susceptibility testing for Granulicatella spp is only performed by specialised laboratories, and results may take several weeks due to the fastidious nature of the organism and difficulty recovering it. Therefore, empiric treatment with vancomycin and gentamicin is recommended.

Combined medical and surgical treatment may be necessary to achieve a cure of infection as a delay in diagnosis and heart failure refractory to medical therapy is common at initial diagnosis.

Footnotes

Contributors: SF: identified this unique case, conducted an extensive literature review and wrote this case. ZEG and MRS: contributed by reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Collins MD, Lawson PA. The genus Abiotrophia (Kawamura et al.) is not monophyletic: proposal of Granulicatella gen. nov., Granulicatella adiacens comb. nov., Granulicatella elegans comb. nov. and Granulicatella balaenopterae comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2000;50 Pt 1(Pt 1):365–9. 10.1099/00207713-50-1-365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Giuliano S, Caccese R, Carfagna P, et al. Endocarditis caused by nutritionally variant streptococci: a case report and literature review. Infez Med 2012;20:67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stein DS, Nelson KE. Endocarditis due to nutritionally deficient streptococci: therapeutic dilemma. Rev Infect Dis 1987;9:908–16. 10.1093/clinids/9.5.908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Casalta JP, Habib G, La Scola B, et al. Molecular diagnosis of Granulicatella elegans on the cardiac valve of a patient with culture-negative endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol 2002;40:1845–7. 10.1128/JCM.40.5.1845-1847.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Frenkel A, Hirsch W. Spontaneous development of L forms of streptococci requiring secretions of other bacteria or sulphydryl compounds for normal growth. Nature 1961;191:728–30. 10.1038/191728a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ruoff KL. Nutritionally variant streptococci. Clin Microbiol Rev 1991;4:184–90. 10.1128/CMR.4.2.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ohara-Nemoto Y, Kishi K, Satho M, et al. Infective endocarditis caused by Granulicatella elegans originating in the oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol 2005;43:1405–7. 10.1128/JCM.43.3.1405-1407.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Adam EL, Siciliano RF, Gualandro DM, et al. Case series of infective endocarditis caused by Granulicatella species. Int J Infect Dis 2015;31:56–8. 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roggenkamp A, Leitritz L, Baus K, et al. PCR for detection and identification of Abiotrophia spp. J Clin Microbiol 1998;36:2844–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Christensen JJ, Facklam RR. Granulicatella and Abiotrophia species from human clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol 2001;39:3520–3. 10.1128/JCM.39.10.3520-3523.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kitada K, Okada Y, Kanamoto T, et al. Serological properties of Abiotrophia and Granulicatella species (nutritionally variant streptococci). Microbiol Immunol 2000;44:981–5. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb02593.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patri S, Agrawal Y. Granulicatella elegans endocarditis: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. BMJ Case Rep 2016;2016 10.1136/bcr-2015-213987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sapico FL, Liquete JA, Sarma RJ. Bone and joint infections in patients with infective endocarditis: review of a 4-year experience. Clin Infect Dis 1996;22:783–7. 10.1093/clinids/22.5.783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thomas P, Allal J, Bontoux D, et al. Rheumatological manifestations of infective endocarditis. Ann Rheum Dis 1984;43:716–20. 10.1136/ard.43.5.716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 2008;139 Suppl:3s–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Al-Tawfiq JA, Kiwan G, Murrar H. Granulicatella elegans native valve infective endocarditis: case report and review. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2007;57:439–41. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mushtaq A, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Cole NC, et al. Differential Antimicrobial Susceptibilities of Granulicatella adiacens and Abiotrophia defectiva. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016;60:5036–9. 10.1128/AAC.00485-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]