Abstract

A 67-year-man presented to the emergency department with massive hemoptysis, coughing up about 250 mL frank blood in 2–3 hours. Physical examination was significant for tachycardia, tachypnea and blood around the mouth. A CT of the chest did not reveal any aetiology of hemoptysis. Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy was remarkable for an actively oozing 1×1 cm sessile subglottic polyp on the anterior tracheal wall. CT neck revealed a 2.5×2.4 cm pretracheal soft tissue mass, bulging into the subglottic trachea. Fine needle aspiration confirmed papillary thyroid carcinoma with BRAF mutation. The patient underwent radical resection and surgical pathology confirmed a 2.5 cm papillary thyroid carcinoma with extensive extra-thyroid extension into the tracheal mucosa. Invasion of the trachea and surrounding structures like larynx and oesophagus is not usual for papillary thyroid carcinoma and may be associated with aggressive cancer behaviour and relatively poor outcome and prognosis.

Keywords: thyroid disease, cancer, carcinogenesis, surgery

Background

Primary tracheal tumours are predominantly malignant. Thyroid, larynx, lung, breast and colon cancers may metastasize to the trachea as well. Papillary thyroid carcinoma is the most common thyroid cancer with excellent prognosis and survival (>95% 5-year survival rate). Invasion of the upper aerodigestive tract is not usual for papillary thyroid carcinoma and such an invasion may be a marker of aggressive cancer behaviour and relatively poor outcome and prognosis. We present a case of massive hemoptysis due to tracheal invasion by papillary thyroid carcinoma, which is relatively unusual for this cancer.

Case presentation

A 67-year-old man presented to the emergency department complaining of cough with bright red blood that had started after waking up that morning. He reported having cough, hoarseness and occasional night sweats for the last 6 weeks. The cough was initially dry but had become productive 3 days before presentation to the emergency department.

His past medical history was significant for atrial fibrillation on warfarin, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea (on continuous positive airway pressure therapy), allergic rhinitis, morbid obesity (body mass index 42), tobacco abuse of 50 pack years, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, osteoarthritis (both knees) and benign prostate hyperplasia. He was a construction worker operating heavy machinery till 15 years prior. He had to be admitted to the medical intensive care unit, after he coughed up about 250 mL frank blood in the first 2–3 hours. Warfarin was reversed with vitamin K and fresh frozen plasma.

Vital signs were remarkable for tachycardia, tachypnea and oxygen saturation 93% on room air. Physical examination was significant for morbid obesity, blood around the mouth, irregular pulse, diminished breath sounds at bilateral lung bases and chronic bilateral lower extremity oedema. Epistaxis was not observed.

Investigations

Admission labs revealed mild leukocytosis 11.7×109/L (64% neutrophils, 21% lymphocytes, 11% monocytes and 4% eosinophils), haemoglobin 14.6 g/dL (baseline 15 g/dL), platelets 258×109/L and INR 2.6. Electrolytes, renal and liver function tests were unremarkable. Chest radiograph showed a mildly enlarged heart and right basilar atelectasis (figure 1). A CT of the chest was negative for pulmonary embolism (figure 2) and significant only for several scattered sub-5 mm pulmonary nodules. Bedside flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy was remarkable for an actively oozing 1×1 cm sessile subglottic polyp on the anterior tracheal wall, 0.5 cm below the vocal cords (figure 3). Visual inspection of the remainder of the tracheobronchial tree showed normal anatomy without additional sources of bleeding. Serial bronchoalveolar lavage specimens ruled out diffuse alveolar haemorrhage. A CT neck was requested for further evaluation and revealed a 2.5×2.4 cm pretracheal soft tissue mass at the level of cricothyroid membrane, bulging into the subglottic trachea (figure 4). Ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration of the pre-tracheal mass was performed and confirmed papillary thyroid carcinoma, positive for BRAF mutation.

Figure 1.

Chest radiograph (PA view) showing mildly enlarged heart and right basilar atelectasis.

Figure 2.

CT angiogram chest ruling out pulmonary embolism.

Figure 3.

Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealing an actively bleeding sessile subglottic polyp on the anterior tracheal wall just distal to vocal cord opening.

Figure 4.

CT neck showing pretracheal soft tissue mass at the level of cricothyroid membrane bulging into the subglottic trachea.

Treatment

The patient underwent total thyroidectomy, central compartment neck dissection, tracheal resection, slide tracheoplasty and microlaryngoscopy with excision of the vocal fold carcinoma. A lesion of about 4 cm in diameter was found in the superior isthmus of the pyramidal thyroid lobe and appeared fixed to the thyroid cartilage and cricothyroid membrane. Microlaryngoscopy showed tracheal invasion anteriorly, superior to the cricoid cartilage. Surgical pathology confirmed a 2.5 cm classic (conventional) papillary thyroid carcinoma arising in the pyramidal thyroid lobe with extensive extra-thyroid extension through cricothyroid membrane into the tracheal mucosa (figures 5 and 6). There was no regional lymph node metastasis. The final clinical stage was IVA (T4a, N0, M0; tumour, node, metastases (TNM)). Subsequently the patient underwent radioactive iodine therapy and external beam radiation.

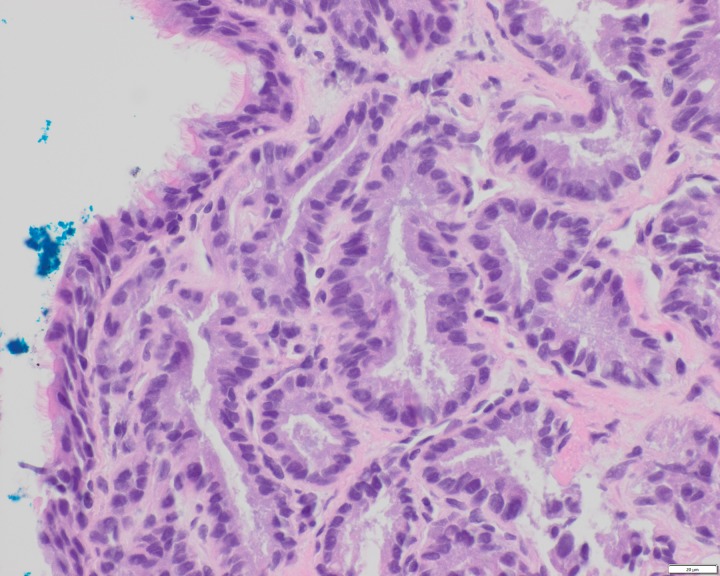

Figure 5.

Papillary thyroid carcinoma invading cricothyroid membrane and extending into the tracheal mucosa (H&E stain 100x).

Figure 6.

Papillary thyroid carcinoma invading cricothyroid membrane and extending into the tracheal mucosa (H&E stain 400x).

Outcome and follow-up

The patient has been following up with otolaryngology and endocrinology regularly. He is on thyroid hormone replacement and continues to do well without any disease recurrence, 27 months post treatment.

Discussion

Papillary thyroid carcinoma accounts for 84%–91% of the thyroid cancers.1 2 It shows a slight prevalence in females (F:M, 2.5:1).2 BRAF mutation is the most common genetic abnormality found in papillary thyroid carcinoma with the incidence of about 60%.2 Our patient was also found to have a BRAF mutation. Papillary thyroid carcinoma most commonly presents as a thyroid nodule. Thyroid nodules can be screened with ultrasound and fine needle aspiration can confirm the diagnosis. Age more than 50 years (as in our patient) and microcalcification on thyroid ultrasound may be associated with BRAF mutation in papillary thyroid carcinoma patients without Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.2 3 The presence of a solid component on thyroid ultrasound may be a predictor of BRAF mutation in papillary thyroid carcinoma patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.3 BRAF mutation is a risk factor for aggressive cancer behaviour and cancer recurrence and associated with male gender, tumour size more than 1 cm, lymph node metastasis, extra-thyroid extension, multifocal disease, advanced clinical stage and classic and tall cell papillary carcinoma variants.4 Our patient had several of these factors associated with BRAF mutation including male gender, tumour size 2.5 cm, extra-thyroid extension into the trachea and advanced stage (IVA). Our patient had classic (conventional) papillary thyroid carcinoma with BRAF mutation and tracheal invasion, which is another novel feature of the case.

Tracheal invasion is also considered a risk factor for cancer recurrence, distant metastasis and shorter disease-free and disease-specific survival.5 Tracheal invasion associated with papillary thyroid carcinoma is more common in male and older adult patients and hemoptysis is the most common symptom in such cases.6 Other common symptoms are hoarseness, neck mass, dyspnea and dysphagia. Distant metastases are most common to the lungs, followed by bone and mediastinal lymph nodes.6 7 Respiratory failure and hemoptysis due to pulmonary metastasis lead to death in most cases.6 Our patient presented with massive hemoptysis due to tracheal invasion and also reported hoarseness for the last 6 weeks. He did not have any distant metastasis and continues to be free of disease recurrence, to date.

Surgery aiming at complete excision with negative margins versus conservative approach with shaving or peeling techniques to remove gross disease and postoperative radioactive iodine and radiotherapy are the main treatment modalities, depending on the extent of the disease and comorbid conditions.6–9 Our patient was a good surgical candidate and underwent radical resection, followed by radioactive iodine therapy and external beam radiation. About 5% patients develop metastatic disease which does not respond to the traditional therapy. Targeted therapy aimed against mutations may be helpful in treating advanced and recurrent disease and potential future.10

In conclusion, papillary thyroid carcinoma is the most common thyroid cancer with a generally excellent prognosis. The cancer usually does not invade the surrounding structures. Invasion of the trachea and other surrounding structures like larynx and oesophagus may be associated with aggressive cancer behaviour and worse prognosis.

Learning points.

Papillary thyroid carcinoma is the most common thyroid cancer. Mutations including BRAF V600E, RET/PTC and RAS play an important role in the carcinogenesis process and prognosis. BRAF mutation is a risk factor for cancer recurrence, poor response to radioactive iodine therapy and cancer related mortality.

Papillary thyroid carcinoma most commonly spreads to the regional lymph nodes. Invasion of the upper aerodigestive tract is a risk factor for cancer recurrence, distant metastasis and associated with shorter disease-free and disease-specific survival.

Hemoptysis is the most common symptom of papillary thyroid carcinoma invading the tracheal mucosa. Respiratory failure and hemoptysis due to pulmonary metastasis most commonly lead to death in such cases.

Targeted therapy aimed against mutations may be helpful in treating advanced and recurrent disease and potential future.

Footnotes

Contributors: WA and AS were involved in direct patient care with full access to the patient data and drafted the initial manuscript. SJ and SG reviewed the manuscript, provided feedback and helped in the final editing of the manuscript. WA followed up with the patient.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Lim H, Devesa SS, Sosa JA, et al. Trends in thyroid cancer incidence and mortality in the United States, 1974-2013. JAMA 2017;317:1338–48. 10.1001/jama.2017.2719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fakhruddin N, Jabbour M, Novy M, et al. BRAF and NRAS mutations in papillary thyroid carcinoma and concordance in BRAf mutations between primary and corresponding lymph node metastases. Sci Rep 2017;7:4666 10.1038/s41598-017-04948-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang Q, Liu BJ, Ren WW, et al. Association between BRAF V600E mutation and ultrasound features in papillary thyroid carcinoma patients with and without hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Sci Rep 2017;7:4899 10.1038/s41598-017-05153-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li C, Lee KC, Schneider EB, et al. BRAF V600E mutation and its association with clinicopathological features of papillary thyroid cancer: a meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:4559–70. 10.1210/jc.2012-2104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hotomi M, Sugitani I, Toda K, et al. A novel definition of extrathyroidal invasion for patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma for predicting prognosis. World J Surg 2012;36:1231–40. 10.1007/s00268-012-1518-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim H, Jung HJ, Lee SY, et al. Prognostic factors of locally invasive well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma involving the trachea. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2016;273:1919–26. 10.1007/s00405-015-3724-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tsukahara K, Sugitani I, Kawabata K. Surgical management of tracheal shaving for papillary thyroid carcinoma with tracheal invasion. Acta Otolaryngol 2009;129:1498–502. 10.3109/00016480902725239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shenoy AM, Burrah R, Rao V, et al. Tracheal resection for thyroid cancer. J Laryngol Otol 2012;126:594–7. 10.1017/S002221511200059X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ito Y, Fukushima M, Yabuta T, et al. Local prognosis of patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma who were intra-operatively diagnosed as having minimal invasion of the trachea: a 17-year experience in a single institute. Asian J Surg 2009;32:102–8. 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60019-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brose MS, Cabanillas ME, Cohen EE, et al. Vemurafenib in patients with BRAF(V600E)-positive metastatic or unresectable papillary thyroid cancer refractory to radioactive iodine: a non-randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1272–82. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30166-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]