Abstract

Insects are the only known animals in which sexual differentiation is controlled by sex-specific splicing. The doublesex transcription factor produces distinct male and female isoforms, which are both essential for sex-specific development. dsx splicing depends on transformer, which is also alternatively spliced such that functional Tra is only present in females. This pathway has evolved from an ancestral mechanism where dsx was independent of tra and expressed and required only in males. To reconstruct this transition, we examined three basal, hemimetabolous insect orders: Hemiptera, Phthiraptera, and Blattodea. We show that tra and dsx have distinct functions in these insects, reflecting different stages in the changeover from a transcription-based to a splicing-based mode of sexual differentiation. We propose that the canonical insect tra-dsx pathway evolved via merger between expanding dsx function (from males to both sexes) and narrowing tra function (from a general splicing factor to dedicated regulator of dsx).

Research organism: Other

Introduction

Sex determination and sexual differentiation evolve on drastically different time scales. Sex determination (that is, the primary signal directing the embryo to develop as male or female) can be either environmental or genetic. Genetic sex determination can in turn be either male- or female-heterogametic (with or without heteromorphic sex chromosomes), mono- or polygenic, or haplo-diploid, among other mechanisms (Charlesworth, 1996; Graves, 2006; Ellegren, 2000; Jablonka and Lamb, 1990; Ser et al., 2010; Beye et al., 2003; Merchant-Larios and Díaz-Hernández, 2013). Primary sex determination is among the most rapidly evolving developmental processes. In African clawed frogs, medaka, salmon, and other animals, there are many examples of recently evolved sex-determining genes, so that the primary sex determination genes can differ between closely related species (Bewick et al., 2011; Roco et al., 2015; Myosho et al., 2012; Takehana et al., 2008; Li et al., 2011; Tree of Sex Consortium et al., 2014). The signals initiating male or female development can vary even within species, as seen in cichlids, zebrafish, house flies, and ranid frogs (Ser et al., 2010; Anderson et al., 2012; Liew et al., 2012; Tomita and Wada, 1989; Meisel et al., 2016; Nakamura, 2009).

In contrast, sexual differentiation (that is, the set of molecular mechanisms that translates the primary sex-determining signal into sexually dimorphic development of specific organs) tends to remain stable for hundreds of millions of years despite the rapid evolution of both sex determination and the multitude of anatomical, physiological, and behavioral manifestations of sexual dimorphism. This fits the broader ‘hourglass’ pattern of developmental evolution, where the most upstream and downstream tiers of developmental hierarchies diverge more rapidly than the middle tiers (Duboule, 1994; Hanken and Carl, 1996; Hazkani-Covo et al., 2005). In the case of vertebrate sexual development, this middle tier is comprised of sex hormones and their receptors, which are largely conserved from mammals to fish, as are the key components of the network of transcription factors and signaling pathways that toggle gonad development between ovary and testis (Raymond et al., 1999; Brennan and Capel, 2004; Hau, 2007; Maatouk et al., 2008; Matson et al., 2011; Lindeman et al., 2015; Herpin and Schartl, 2015). In nematodes, key components of the sexual differentiation pathway are conserved between Caenorhabditis and Pristionchus, which are separated by 200–300 million years (Pires-daSilva and Sommer, 2004).

Similarly, the insect sexual differentiation pathway, while unique among metazoans, shows deep conservation across 300 million years of insect evolution (Ohbayashi et al., 2001; Suzuki et al., 2003; Cho et al., 2007; Hasselmann et al., 2008; Oliveira et al., 2009; Saccone et al., 2002; Shukla and Palli, 2012a; Shukla and Palli, 2012b). This pathway has three distinctive features. First, the doublesex (dsx) gene is spliced into a male-specific isoform in males and a female-specific isoform in females; the two isoforms encode transcription factors that share a common N-terminal DNA-binding domain but have mutually exclusive C-termini, which lead them to have distinct and often opposite effects on downstream gene expression and morphological development (Baker and Wolfner, 1988; Burtis and Baker, 1989; Baker, 1989; McKeown, 1992; Coschigano and Wensink, 1993; Arbeitman et al., 2004; Rideout et al., 2010). Second, alternative splicing of dsx is controlled by the RNA splicing factor transformer (tra); and third, tra itself is alternatively spliced so that it produces a functional protein only in females, while in males a premature stop codon results in a truncated, non-functional Tra protein (Boggs et al., 1987; Inoue et al., 1992; Sosnowski et al., 1989; Hoshijima et al., 1991; Verhulst et al., 2010). Thus, the male-specific dsx isoform is produced by default, while the production of the female dsx isoform requires active intervention by tra. Despite some differences in details, the transformer-doublesex splicing cascade is conserved among insect orders separated by >300 million years, including Diptera, Coleoptera, and Hymenoptera, indicating that this pathway was already present in the last common ancestor of holometabolous insects (Cho et al., 2007; Shukla and Palli, 2012a; Shukla and Palli, 2012b; Ruiz et al., 2005). The one exception to this rule is found in Lepidoptera, where tra has been secondarily lost and dsx splicing is regulated instead by a male-specific protein and a female-specific piRNA (Kiuchi et al., 2014).

Although conserved within insects, the transformer-doublesex splicing pathway appears to be unique among animals, as nothing similar has been observed in any other animal group. The differences in the molecular basis of sexual differentiation between insects, nematodes, and vertebrates are fundamental. In insects, dsx and tra operate in a mostly cell-autonomous manner, as evidenced for example by dramatic insect gynandromorphs (Steinmann-Zwicky et al., 1989; Janzer and Steinmann-Zwicky, 2001; Robinett et al., 2010; Pereira et al., 2010). In vertebrates, sexual differentiation is largely non-cell-autonomous. During embryonic development, the originally bipotential vertebrate gonad is biased to become either ovary or testis under the influence of the primary sex-determining signal, which can be either genetic or environmental (Raymond et al., 1999; Devlin and Nagahama, 2002; Kim and Capel, 2006; Shoemaker et al., 2007). Subsequently, male or female hormones produced by the gonad act through nuclear receptor signaling to direct somatic tissues to differentiate in sex-specific ways. In rhabditid nematodes such as Caenorhabditis elegans, a multi-step cell signaling cascade involving secreted ligands, transmembrane receptors, and post-translational protein modification results in sex-specific expression of several transcription factors that direct male or female/hermaphrodite development of particular cell lineages (Barnes and Hodgkin, 1996; Pilgrim et al., 1995; Pires-daSilva, 2007; Berkseth et al., 2013).

The deep conservation of fundamentally different mechanisms of sexual differentiation in different animal phyla presents an intriguing question: how do such disparate mechanisms evolve in the first place? Comparison of nematode, crustacean, insect, and vertebrate modes of sexual differentiation suggests that the insect-specific mechanism based on alternative splicing of dsx evolved from a more ancient mechanism based on male-specific transcription of an ancestral dsx homolog. dsx is part of the larger Doublesex Mab-3 Related Transcription factor (DMRT) gene family, which is apparently the only shared element of sexual differentiation pathways across metazoans (Kopp, 2012; Matson and Zarkower, 2012). Dmrt1 is involved in the specification and maintenance of testis fate in mammals and other vertebrates, while repressing ovarian differentiation (Matson et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2003; Webster et al., 2017). Due to their function in the androgen-producing Sertoli cells, vertebrate Dmrt1 genes also play a crucial role in the development of secondary sexual characters. In C. elegans, mab-3 and several other DMRT family genes are responsible for the specification of various male-specific cells, structures, and behaviors (Shen and Hodgkin, 1988; Portman, 2007; Mason et al., 2008; Siehr et al., 2011; Serrano-Saiz et al., 2017). However, in both vertebrates and nematodes, the DMRT genes involved in sexual differentiation are not spliced sex-specifically, but are transcribed in a predominantly male-specific fashion, promote the development of male-specific traits, and are dispensable for female sexual differentiation. In contrast, the insect dsx acts as a bimodal switch that plays active roles in both male- and female-specific differentiation through its distinct male and female splicing isoforms. In the absence of Dsx, both males and females develop as intersexes with phenotypes intermediate between males and females (Rideout et al., 2010; Baker and Ridge, 1980).

In the closest relative of insects that has been studied to date, the branchiopod crustacean Daphnia magna, dsx acts in a manner similar to vertebrates and nematodes rather than insects: it is transcribed male-specifically, is not alternatively spliced, controls the development of male-specific structures, and is dispensable in females (Kato et al., 2011). The D. magna tra gene is not spliced sex-specifically and does not differ in expression between males and females (Kato et al., 2010). dsx also shows male-biased transcription and no sex-specific splicing in the shrimp Fenneropenaeus chinensis (Li et al., 2018) and in the mite Metaseiulus occidentalis (Pomerantz and Hoy, 2015). Thus, the origin of the transformer-doublesex splicing cascade was a key event in the evolution of sexual differentiation in insects.

To understand the evolutionary transition from a transcription-based to a splicing-based mode of sexual differentiation, it is necessary to focus on the phylogenetic interval between branchiopod crustaceans and holometabolous insects. This interval spans several crustacean groups, non-insect hexapods, and many hemimetabolous insect orders, and encompasses a broad range of body plans and developmental mechanisms. Unfortunately, the development of these groups remains poorly studied compared to holometabolous insects; in particular, very little is known about sexual differentiation in hemimetabolous insects.

To explore the origin of the insect sexual differentiation pathway based on the transformer-doublesex axis, we examined the expression of these genes in three hemimetabolous insects: the kissing bug Rhodnius prolixus (Hemiptera), the louse Pediculus humanus (Phthiraptera), and the German cockroach Blattella germanica (Blattodea) (Figure 1—figure supplement 1). We find that distinct male and female dsx isoforms are conserved through Blattodea, the most basal insect order studied to date. However, only R. prolixus shows the canonical sex-specific pattern of tra splicing. In B. germanica, we show that tra nevertheless controls female dsx splicing and is necessary for female sexual differentiation, as in holometabolous insects. Surprisingly, the B. germanica dsx gene is required for male sexual differentiation, but appears to be dispensable in females; in this respect, the cockroach is more similar to crustaceans and non-arthropod animals than to holometabolous insects. Together, our results suggest that the splicing-based mode of sexual differentiation based on the transformer-doublesex regulatory pathway has evolved in a gradual fashion in hemimetabolous insects.

Results

doublesex and transformer orthologs are present in hemimetabolous insects

Although dsx, Dmrt1, and other DMRT genes have prominent roles in sexual differentiation (Raymond et al., 1999; Burtis and Baker, 1989; Kopp, 2012; Matson and Zarkower, 2012; Shen and Hodgkin, 1988) many DMRT paralogs are involved in other developmental processes, and most have phylogenetically restricted distributions (Wexler et al., 2014). The number of DMRT paralogs varies among animal taxa; for example, Drosophila melanogaster has four, while C. elegans has 11 (Wexler et al., 2014). To identify dsx orthologs in hemimetabolous insects for functional study, we performed a phylogenetic analysis of arthropod DMRT genes (Supplementary file 1). By mining arthropod gene models, we recovered the deeply conserved Dmrt11E, Dmrt93B, and Dmrt99B subfamilies in addition to a large clade containing dsx orthologs. The dsx clade contained sequences from several basal insect orders, crustaceans, and chelicerates (Figure 1—figure supplement 1), and included experimentally characterized dsx genes from the branchiopod crustacean D. magna (NCBI accession number BAJ78307.1), the decapod crustacean F. chinensis (AUT13216.1), and the mite M. occidentalis (XP003740429.2 and XP003740430.1). In these species, the dsx genes are not spliced sex-specifically, but are transcribed in a strongly male-biased fashion (Kato et al., 2011; Li et al., 2018; Pomerantz and Hoy, 2015). dsx genes from holometabolous insects, which direct male and female differentiation via alternative splice forms, are also present in this clade. There are marked departures in this gene tree from the arthropod species tree. Notably, many hemipteran dsx sequences group with chelicerates and crustaceans instead of insects, although with low support. The clustering of crustacean and chelicerate dsx genes, which control male sexual development via male-specific upregulation, with holometabolous dsx genes that control male and female development via alternative spliceforms indicates that sex-specific dsx isoforms evolved after the origin of the dsx clade.

Puzzled by the clustering of hemipteran dsx genes with those from chelicerates and crustaceans, we conducted a synteny analysis. While the robustness of this analysis is dependent on the quality of genome assembly, the transcription factor prospero (pros) is on the same scaffold as dsx, with an intervening distance between 17 and 245 kb (Supplementary file 2), in seven different holometabolous and hemimetabolous insect orders (Ephemeroptera, Blattodea, Phthiraptera, Thysanoptera, Hymenoptera, Coleoptera and Lepidoptera). However, in Hemiptera, tBLASTn searches of the prospero-containing scaffolds, ranging in size from ~120 kb to 17 Mb (mean 2.75 Mb), did not identify neighboring DMRT genes (Supplementary file 3). Work in the planthopper Nilaparvata lugens suggests that at least some of the hemipteran dsx genes are alternatively spliced and are necessary for male development (Zhuo et al., 2018). We conclude that hemipterans have dsx orthologs, but the synteny between pros and dsx was lost in the common ancestor to true bugs, and Dsx protein sequences evolved rapidly in this clade.

Transformer proteins have repetitive sequences that evolve rapidly, posing greater difficulties for phylogenetic analysis. Previous studies of insect tra genes have identified these genes via the characteristic arginine/serine rich (RS) domain (Hasselmann et al., 2008), used BLAST to detect a tra candidate and demonstrated congruence between a species tree and a gene tree (Kato et al., 2010), or simply concluded that a candidate tra gene was indeed transformer after knocking it down and obtaining a sex-specific phenotype (Shukla and Palli, 2012a). tra is related to, but is not part of, a large family of genes structurally defined by the presence of an RNA binding domain and at least one RS domain (Long and Caceres, 2009). These proteins, called SR family genes for their amino acid composition, commonly function in pre-mRNA splicing (Long and Caceres, 2009). Because most insect tra genes lack an RNA binding domain (see below), they are classified as RS-like proteins. Our maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis of Tra proteins, along with three previously studied SR family genes (Transformer-2, which is not an ortholog of Transformer; SFRS; and Pinin) shows that putative tra genes from some hemimetabolous insects including R. prolixus, P. humanus, and B. germanica cluster with experimentally characterized holometabolous tra genes and with the D. magna tra, although with low support (Figure 1—figure supplement 1). Despite poor phylogenetic resolution, the putative tra genes identified in R. prolixus, P. humanus, and B. germanica provided an avenue for experimental analysis of sexual differentiation in hemimetabolous insects.

Prior work has shown that dsx is arthropod-specific (Wexler et al., 2014); the present analyses confirm that dsx was probably present in the last common ancestor of arthropods. More research is needed to pinpoint the origin of tra, but the poorly conserved and highly repetitive nature of Tra proteins suggests that this problem might be intractable.

tra splicing follows the holometabolous sex-specific pattern in R. prolixus but not in P. humanus or B. germanica

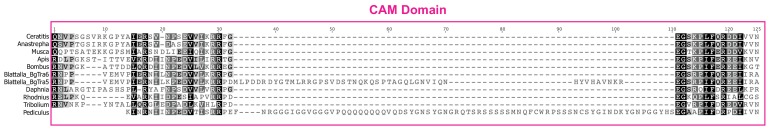

Insect Tra proteins are defined by three key features: (1) an arginine-serine rich (RS) domain, (2) a proline rich domain, and, (3) for all non-Drosophila tra sequences, an auto-regulatory CAM domain named for the three genera in which it was discovered, Ceratitis-Apis-Musca (Verhulst et al., 2010; Hediger et al., 2010; Tanaka et al., 2018). In the holometabolous insect orders Diptera, Coleoptera, and Hymenoptera, a premature male-specific stop codon truncates the tra coding sequence, making the male Tra protein unable to regulate dsx splicing (Hasselmann et al., 2008; Boggs et al., 1987; Inoue et al., 1992; Sosnowski et al., 1989). These insects produce a male-specific dsx isoform by default, while females produce a female-specific dsx isoform as a result of having functional Tra. To understand when tra-dependent alternative splicing of dsx evolved, we identified tra isoforms expressed in sexually dimorphic tissues of males and females from three hemimetabolous insect orders (Hemiptera: R. prolixus; Phthiraptera: P. humanus; and Blattodea: B. germanica). We find that the characteristic holometabolous-like pattern of sex-specific splicing of tra, with a male-specific premature stop codon, is present in R. prolixus but not in P. humanus or B. germanica. Instead, P. humanus and B. germanica display novel patterns of alternative splicing, which include the presence of female-biased truncated tra isoforms and an interrupted CAM domain.

Rhodnius prolixus

In R. prolixus, we identified a tandem duplication of tra on scaffold KQ034193 (Rhodnius-prolixus-CDC_SCAFFOLDS_RproC3, v.1) via tBLASTn searches of the R. prolixus genome (Mesquita et al., 2015). In the phylogenetic tree of arthropod SR proteins (Figure 1—figure supplement 1), the two R. prolixus paralogs (RpTraA and RpTraB) cluster within a clade that also contains dipteran, hymenopteran, and coleopteran Tra proteins. The downstream R. prolixus tra paralog, which we call RpTraB, encodes conserved Tra amino acid residues at its N-terminus, including the CAM domain and an RS domain, but is truncated at the C-terminus and lacks a proline-rich domain (Figure 1—figure supplement 2). In contrast, the upstream RpTraA paralog encodes a full-length Tra protein with a C-terminal proline-rich domain. Interestingly, RpTraA is also predicted to contain a partial RNA Recognition Motif (RRM) (Figure 1—figure supplement 3), a feature which has not been described in previous studies of Tra proteins. However, when we inspected predicted protein domains in Tra sequences from Branchiopoda, Copepoda, Blattodea, Hemiptera, Hymenoptera, Coleoptera, and Diptera with CCD/SPARCLE software via NCBI (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2017), we found putative RRM domains in Apis mellifera CSD, R. prolixus TraA, a predicted Tra protein from the copepod crustacean Tigriopus californicus, and the cockroach B. germanica Tra ortholog (Figure 1—figure supplement 3). The absence of the RRM domain from most arthropod Tra sequences suggests that insect Tra proteins once had a functional RRM domain but lost RNA-binding activity over time, perhaps due to the association between Tra and the RNA-binding protein Tra-2 (48). RpTraA and RpTraB are the first reported tra duplicates outside of Hymenoptera, where tra duplications sometimes result in functional innovation (Hasselmann et al., 2008; Geuverink and Beukeboom, 2014).

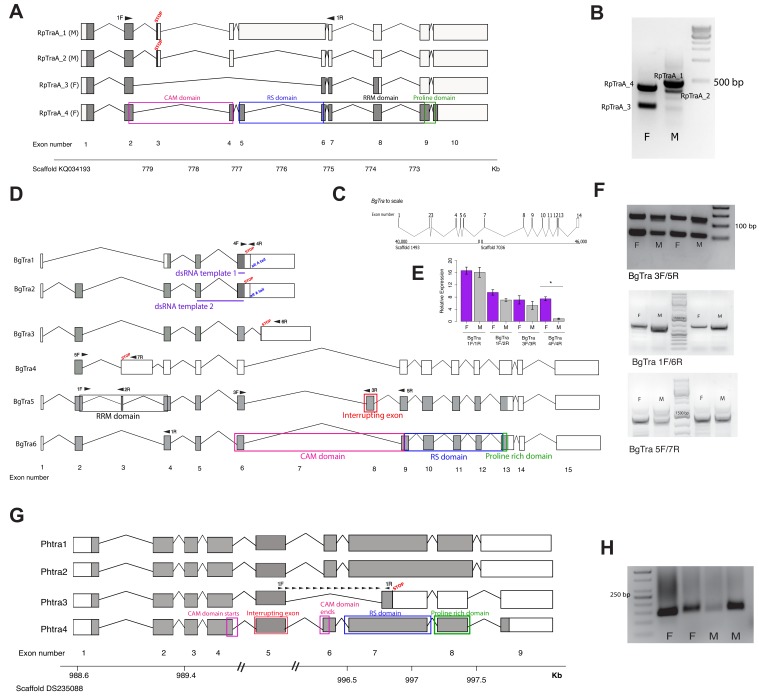

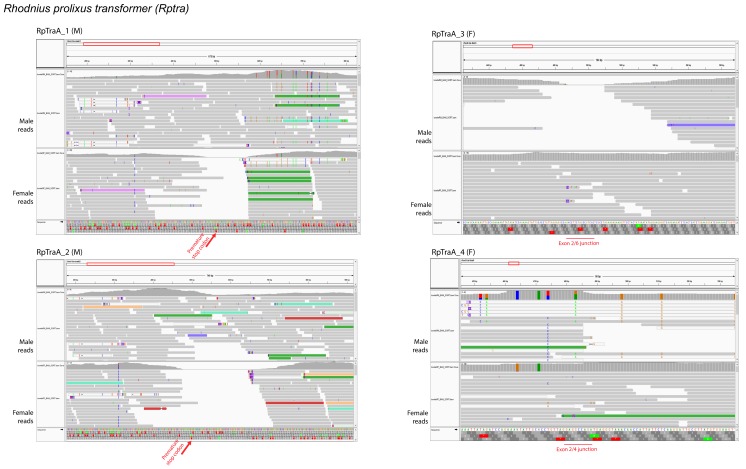

To investigate whether RpTraA is expressed similarly to holometabolous tra orthologs, we conducted 5’ and 3’ Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) to obtain the sets of isoforms expressed in male and female R. prolixus. Using separate male and female RNA samples, we also generated de novo transcriptome assemblies using Illumina sequencing and Trinity software (Grabherr et al., 2011). We were unable to recover RpTraB from adult male or female gonad transcriptomes, nor could we recover any RpTraB product by RT-PCR. We found two female-specific RpTraA transcripts (RpTraA_3 and RpTraA_4) and two male-specific transcripts (RpTraA_1 and RpTraA_2) (Figure 1A). All transcripts were identified as sex-specific based on their presence/absence in male and female RACE and RNA-seq libraries, and their sex-specificity was further confirmed by RT-PCR (Figure 1B). As in the holometabolous tra splicing, both male-specific transcripts (RpTraA_1 and RpTraA_2) contain stop codons near the N-terminus and thus encode truncated proteins that are almost certainly incapable of regulating RNA splicing (Figure 1A). Only the RpTraA_4 transcript encodes a complete Tra protein with the CAM domain followed by an RS domain, RRM domain, and a proline-rich domain (Figure 1A). The female-specific RpTraA_3 lacks the stop codon found in male RpTraA transcripts, but has truncated RS and CAM domains and lacks the proline-rich domain. The mapping of male and female RNA-seq reads to the four RpTraA isoforms identified by RACE further confirmed the sex-specificity of these isoforms: no female reads mapped to the male-specific stop codons in RpTraA_1 and RpTraA_2, and no male reads mapped to female-specific exon junctions of RpTraA_3 and RpTraA_4 (Figure 1—figure supplement 4). This pattern – a male-specific premature stop codon that is located in an alternatively spliced exon and results in the production of full-length Tra protein in females but not in males – follows the same pattern as in holometabolous insects including D. melanogaster, A. mellifera, and Tribolium castaneum (Hasselmann et al., 2008; Shukla and Palli, 2012a; Sosnowski et al., 1989). Our detection of truncated Tra isoforms in males but not females in a hemipteran suggests that at least some elements of the sexual differentiation mechanism based on the alternative splicing of tra may predate holometabolous insects.

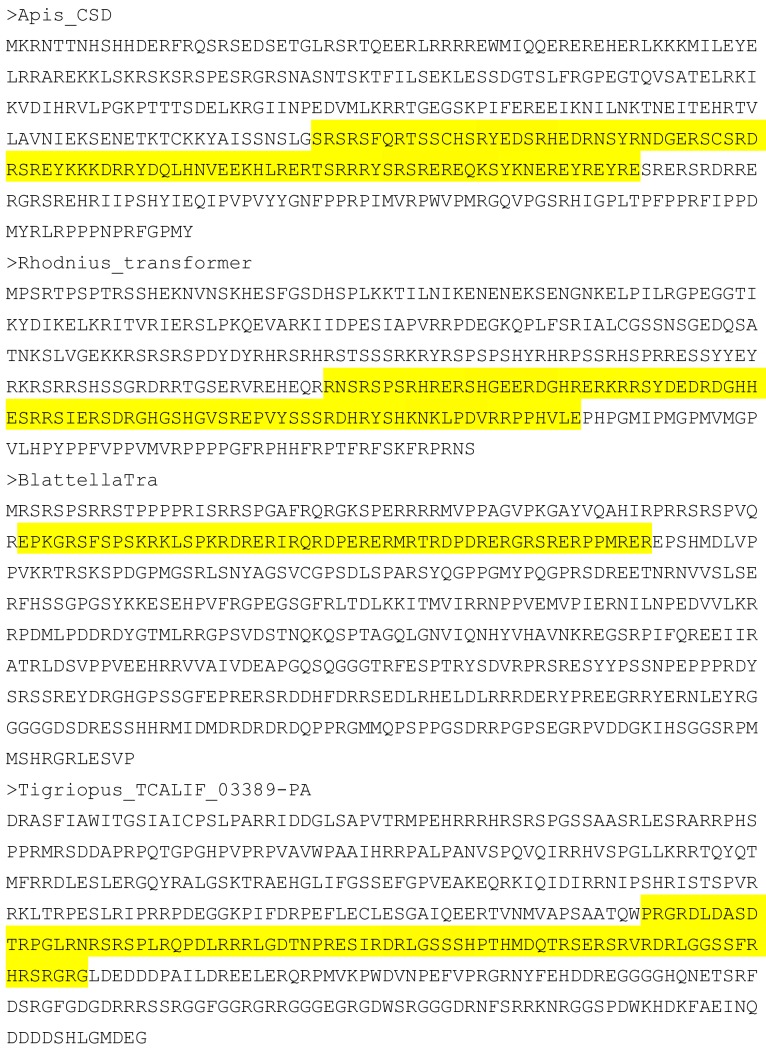

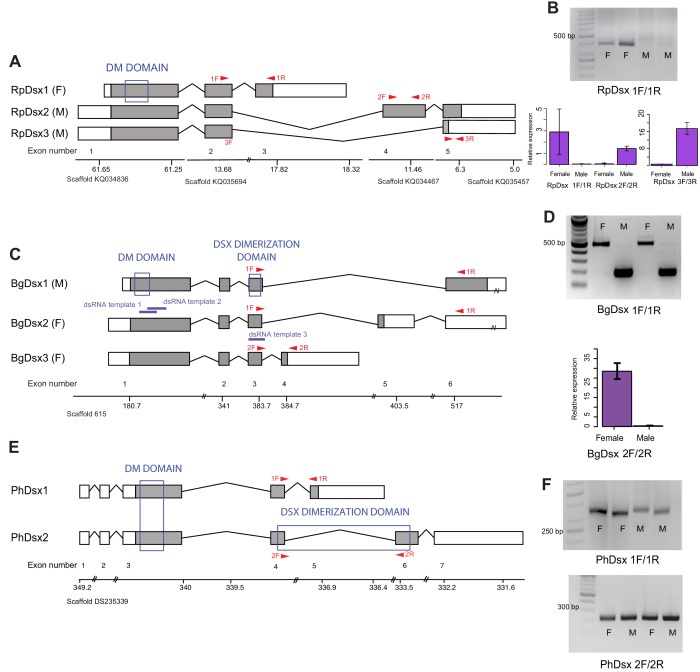

Figure 1. Transformer splicing follows the holometabolous pattern in the kissing bug Rhodnius prolixus, but not in the cockroach Blattella germanica or louse Pediculus humanus.

Schematics showing transformer transcripts isolated from R. prolixus, B. germanica, and P. humanus. Coding sequences are in gray, UTRs are in white. All genes are shown as transcribed from left to right. (A) Four transcripts isolated from RpTraA with 5’ and 3’ RACE and confirmed by RNA-seq. Sex-specificity of each transcript is noted in parentheses at the end of the transcript name. Stop codon in the male-specific 3rd exon is indicated with ‘STOP.’ Predicted Transformer protein domains are shown with colored boxes and labels, using RpTraA_4 as example. (B) PCR on male and female cDNA with RpTraA primers (RpTra_checkF + RpTra_checkR in Supplementary file 7) indicated by black arrows in (A) confirms the sex-specificity of each transcript; all amplicons were verified by Sanger sequencing. (C) BgTra spans two scaffolds in the B. germanica genome. Genome coordinates are shown at the beginning and end of each scaffold. Both scaffolds continue beyond BgTra; scaffold 1493 is 552 kb and scaffold 7036 is 55 kb. (D) Six BgTra transcripts were recovered in PacBio Isoseq data and verified by exon-specific RT-PCR. BgTra1, BgTra2 and BgTra4 were recovered from the female Isoseq dataset; BgTra3, BgTra5, and BgTra6 were recovered from the male Isoseq dataset; however, PCR and qPCR on male and female cDNA showed the presence of BgTra3-6 in both sexes (E, F). Nucleotides that code for important protein domains are color-coded as in panel A, using BgTra5 and BgTra6 as examples. BgTra1 and BgTra2 have alternative polyadenylation sites, marked with blue text. In BgTra1 and BgTra2, exon six extends ~500 bp further 3’ than in all other transcripts. The 3’ end of exon six in BgTra3-6 falls six bp upstream of the stop codon that ends the conceptual translation of BgTra1 and BgTra2. Exon 8 codes for 47 amino acids that interrupt the CAM domain, which spans the end of exon six and the start of exon 9. Purple lines show the locations of dsRNA used for RNAi knock-down. Black arrows indicate locations of primers used for RT-PCR and qPCR. (E) qPCR expression of different BgTra isoforms. The truncated transcripts BgTra1 and BgTra2 are strongly female-biased, while the remaining transcripts are sexually monomorphic. (F) RT-PCR expression of different BgTra isoforms. Top panel: both males and females express transcripts with and without the exon interrupting the CAM domain. The shorter band contains BgTra isoforms that skip exon eight and contain an intact CAM domain; the larger product contains exons 6, 8, and 9. Middle panel: both males and females express exon 7, found only in BgTra3 and producing a truncated transcript. Bottom panel: both males and females express the extended exon three with a premature stop codon found in BgTra4. (G) Four PhTra transcripts isolated from P. humanus by 5’ and 3’ RACE. PhTra3 has a premature stop codon and is found in both sexes, as shown by RT-PCR on male and female cDNA in panel (H). Forward primer for PCR shown in (H) spanned the exon 5/7 junction (marked with black arrows in panel (G)); reverse primer for this PCR is in exon 7 (also noted with a black arrow). All PhTra isoforms contain the ‘interrupting exon’ inside of the CAM domain. Double bars on scaffold in panel (G) represent breaks in scaffold scale.

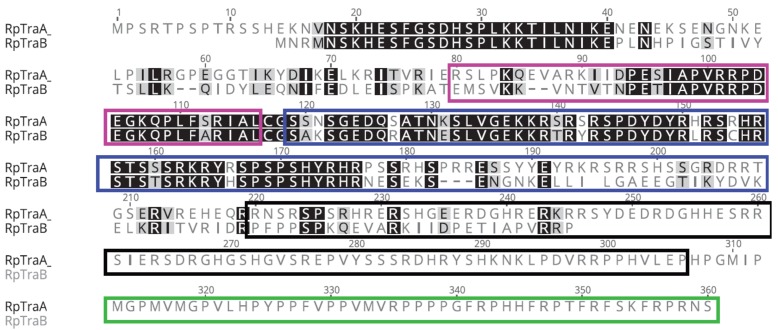

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Three trees: a simplified arthropod phylogeny showing species studied, and gene trees for dsx and tra.

Figure 1—figure supplement 2. MAFFT protein alignment of RpTraB and the longer female-specific isoform of RpTraA from Rhodnius prolixus.

Figure 1—figure supplement 3. RRM domains found in select Transformer proteins.

Figure 1—figure supplement 4. RNA-seq supports the sex-specificity of RpTra isoforms.

Figure 1—figure supplement 5. MAFFT protein alignment of the complete CAM domain in nine different insect species and one crustacean.

Blattella germanica

To characterize tra isoforms in male and female German cockroaches, we sequenced full-length transcripts using a combination of PacBio RNA Isosequencing and 5’ and 3’ RACE on male and female samples. Our tBLASTn search of the B. germanica genome revealed a single putative tra ortholog (BgTra) based on its clustering with A. mellifera and R. prolixus tra genes (Figure 1—figure supplement 1C). Both PacBio RNA Isosequencing and 5’/3’ RACE revealed that BgTra spans over 86 kb of genomic sequence on two separate scaffolds (genome assembly: i5K Bger Scaffolds v.1) (Figure 1C). The gene model of BgTra contains all previously described functional domains of insect Tra proteins – a CAM domain, an RS domain, and a proline rich domain (Figure 1D). Six transcripts, BgTra1-6, were supported by Isoseq and confirmed by Sanger sequencing of RT-PCR products; BgTra1-2 were further confirmed by 3’ RACE, and all but BgTra4 were confirmed by 5’ RACE. Three transcripts (BgTra1-3) are truncated and do not extend past the CAM domain, while BgTra4 contains a premature stop codon (Figure 1D). The remaining two transcripts – BgTra5 and BgTra6 – encode predicted full-length Tra proteins. BgTra6 contains an intact CAM domain, while in BgTra5 this domain is interrupted by an in-frame exon. In addition, BgTra5 contains a prediced RRM domain (Figure 1D).

Unlike holometabolous insects and R. prolixus, the production of full-length Tra protein is clearly not limited to females in B. germanica. Although BgTra1, BgTra2, and BgTra4 were originally isolated by Isoseq from female samples, and BgTra3, BgTra5, and BgTra6 from male samples, RT-PCR and qPCR revealed the presence of all isoforms in both sexes (Figure 1E,F). Two of the short isoforms with a truncated CAM domain and lacking the RS and proline-rich domains (BgTra1-2) have strongly female-biased expression (Figure 1E), while another truncated isoform, BgTra3, has a slight male bias (Figure 1F). Importantly, the two full-length isoforms containing all of the Tra functional domains, BgTra5-6, are expressed at sexually monomorphic levels (Figure 1E,F).

Pediculus humanus

The louse P. humanus shows a pattern of tra splicing similar to that in the cockroach. Using a tBLASTn search followed by 5’ RACE, we identified a single gene, PhTra, in the P. humanus genome, which clustered with other tra orthologs in our phylogenetic analyses (Figure 1—figure supplement 1C). Using 5’ and 3’ RACE and Illumina RNA-seq followed by de novo transcriptome assembly, we identified four PhTra isoforms (Figure 1G). PhTra1 and PhTra4 were found in both male and female RACE libraries, as well as in the female RNA-seq assembly. PhTra2 and PhTra3 were amplified in only the male RACE library, and were not found in either male or female transcriptome assemblies. PhTra3 differs from the other isoforms in containing a premature stop codon in the middle of the RS domain (Figure 1G). RT-PCR shows that this isoform is present in both males and females (Figure 1H). The remaining three PhTra isoforms encode full-length proteins including an RS-domain and a proline-rich domain, but contain an exon that interrupts the CAM domain, as in some BgTra isoforms (Figure 1D, Figure 1—figure supplement 5). The location of this exon is conserved between PhTra and BgTra. In both tra orthologs, the CAM domain is interrupted immediately before two highly conserved resides – a glutamic acid followed by a glycine. Remnants of this interrupting exon, which is only found in hemimetabolous tra orthologs, are detected in a conserved exon junction right before these two amino acids in the tra orthologs of holometabolous insects (Hediger et al., 2010).

Overall, our comparison of R. prolixus, B. germanica, and P. humanus shows that the sex-specific splicing of tra, which is typical of holometabolous insects and limits Tra protein function to females, is found in some but not all hemimetabolous insects.

doublesex splicing follows the holometabolous, sex-specific pattern in some but not all hemimetabolous insects

In holometabolous insects, the Doublesex transcription factor has male- and female-specific isoforms. The male and female proteins share the DNA-binding DM domain and an oligomerization domain that promotes homodimerization of the transcription factor. This domain is essential to Dsx function, as the protein can only bind DNA efficiently as a dimer (Erdman et al., 1996; Cho and Wensink, 1998). Male- and female-specific exons at the 3’ end of dsx transcripts are responsible for sex-specific expression of Dsx target genes. We recovered one dsx ortholog each from R. prolixus (RpDsx), P. humanus (PhDsx), and B. germanica (BgDsx) (Figure 1—figure supplement 1). To test for the presence of sex-specific dsx isoforms, we isolated dsx transcripts using PacBio Isosequencing, Illumina RNA-sequencing, and 5’ and 3’ RACE on sexually dimorphic tissues. In all three species, we identified alternatively spliced dsx transcripts that follow the canonical holometabolous pattern characterized by a common N-terminus and mutually exclusive C-termini. Sex-specific dsx splicing is conserved through B. germanica, although in P. humanus both alternatively spliced isoforms are sexually monomorphic.

Rhodnius prolixus

5’ and 3’ RACE revealed three RpDsx isoforms, one of which was isolated from female RNA samples (RpDsx1) and two from male samples (RpDsx2 and RpDsx3) (Figure 2A). We also retrieved RpDsx1 from our Trinity de novo transcriptome of R. prolixus female gonads; we were unable to retrieve any dsx isoforms from our male R. prolixus transcriptome. RT-PCR confirmed that RpDsx1 was indeed female-specific, and qPCR showed female-specific expression of RpDsx1 and male-specific expression of RpDsx2 and RpDsx3 (Figure 2B). RpDsx1 and RpDsx2 had low expression in R. prolixus gonads, whereas RpDsx3 was expressed at a 6- to 8-fold higher level than either RpDsx1 or RpDsx2 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Doublesex shows sex-specific splicing in some but not all hemimetabolous insects.

Schematics showing doublesex transcripts isolated from Rhodnius prolixus, Blattella germanica, and Pediculus humanus. Coding sequences are in gray and UTRs in white. Sex-specificity of each transcript is noted in parentheses at the end of the transcript name. Transcripts are shown mapped to genomic scaffolds; double bars show breaks in scale. Functional domains are labeled and indicated by blue boxes. (A) Three dsx transcripts isolated from R. prolixus span multiple genomic scaffolds. RpDsx1 was isolated from 3’ and 5’ RACE libraries made from female RNA; RpDsx2 and RpDsx3 were cloned from RACE libraries synthesized from male RNA. (B) Top panel: RT-PCR showing female-specificity of RpDsx1, using primers in exons 2 and 3, as indicated with red arrows in (A). Bottom panel: qPCR showing female-specific expression of RpDsx1, and male-specific expression of RpDsx2 and RpDsx3, using primers indicated with red arrows in (A). Forward primer 3F spanned the exon 2/5 junction. (C) Three dsx transcripts isolated by 3’ and 5’ RACE and PacBio Isosequencing from B. germanica. The 3’ UTR of BgDsx1 and BgDsx2 contains a retrotransposon (marked with a break) and cannot be mapped to a single scaffold of the roach genome. Purple lines show the locations of dsRNA used for RNAi. Red arrows show primer locations for RT-PCR and qPCR. (D) Sex-specific expression of BgDsx isoforms. Top panel, PCR on cDNA of adult male and female fat body and reproductive tract with primers in exons 3 and 6. The larger band found exclusively in females contains the alternatively included exon 5, as confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Bottom panel, qPCR for exon 3/4 junction shows amplification only in females. (E) Two dsx transcripts isolated by 3’ and 5’ RACE from P. humanus male and female samples. (F) RT-PCR shows the presence of both PhDsx transcripts in both sexes.

Predicted proteins encoded by all three transcripts share the DM domain at their N-termini. However, we failed to detect an oligomerization domain in any of the RpDsx transcripts using either NCBI’s CDD/SPARCLE domain predictor software (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2017) or EMBL’s InterPro (Mitchell et al., 2019). We were similarly unable to detect an oligomerization domain in the Dsx protein sequences of another hemipteran – the planthopper N. lugens (Zhuo et al., 2018) – raising the possibility that hemipteran Dsx has lost this domain and thus has significant functional differences from the Dsx transcription factors of holometabolous insects (Zhuo et al., 2018).

Blattella germanica

With a combination of PacBio isosequencing and RACE, we recovered three dsx isoforms from B. germanica, each with a different terminal 3’ exon and 5’ and 3’ UTRs (Figure 2C). Like dsx genes described from the holometabolous orders Hymenoptera, Coleoptera, Lepidoptera, and Diptera (Suzuki et al., 2003; Cho et al., 2007; Burtis and Baker, 1989; Kijimoto et al., 2012), these isoforms are identical at their N-termini but differ by alternative splicing at the C-termini. The shared N-terminal sequence contains both the DM domain and the oligomerization domain (Figure 2C). RT-PCR and qPCR revealed that BgDsx1 is found only in males, while BgDsx2 and BgDsx3 are female-specific (Figure 2D). This pattern of sexually dimorphic splicing, in which male and female transcripts share the DM domain but have different C-terminal domains, is typical of dsx in holometabolous insects (Cho et al., 2007; Shukla and Palli, 2012b; Ruiz et al., 2005).

Pediculus humanus

5’ and 3’ RACE identified two PhDsx isoforms, PhDsx1 and PhDsx2, both of which were found in both male and female RACE libraries (Figure 2E). While both PhDsx1 and PhDsx2 have DM domains at their N-termini, alternative exon inclusion at the C-terminus yields a predicted Dsx dimerization domain in PhDsx2 but not PhDsx1. RT-PCR on a different set of male and female louse samples confirmed that both PhDsx1 and PhDsx2 were expressed in both sexes (Figure 2F).

The order Blattodea, which includes cockroaches, is the most basal insect group in which dsx splicing has been examined to date. Thus, our results suggest that sex-specific dsx splicing appeared early in insect evolution, and the sharing of isoforms between sexes in P. humanus may represent a secondary loss of sex-specificity.

tra is necessary for female, but not male development in B. germanica

B. germanica has a number of overt sexually dimorphic traits. Adult females are darker and have a rounded abdomen, while male abdomens are more slender (Figure 3A). Males also have a tergal gland that produces a mixture of oligosaccharides and lipids upon which females feed prior to copulation (Nojima et al., 1999). This gland, located on the dorsal abdomen under the wings, appears externally as invagination in the 7th and 8th tergites, resulting in a complex structure with depressions and holes that lead to the internal glands (Figure 3B) (Ylla and Belles, 2015). Finally, the ovaries, testes, and accessory glands that compose the male and female reproductive systems can be easily distinguished upon dissection (Figure 3C,D). To test whether BgTra, with its novel splicing pattern, functions to produce male and female traits similarly to its holometabolous orthologs, we used RNAi to knock it down at different stages of development.

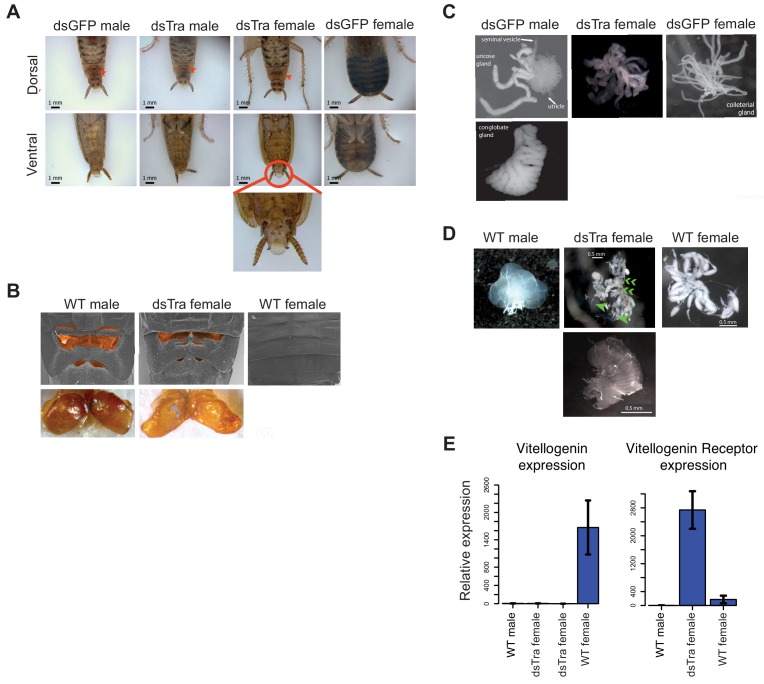

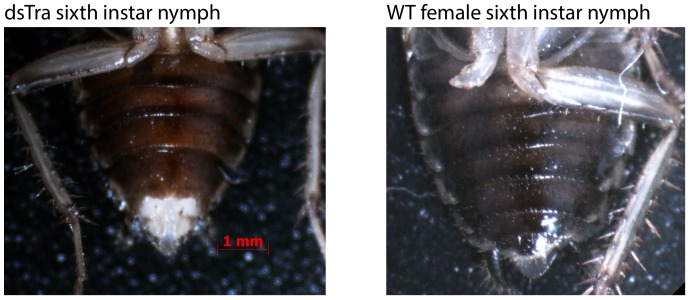

Figure 3. BgTra is necessary for female-specific but not male-specific sexual differentiation in Blattella germanica.

(A) dsBgTra females, injected with dsBgTra in their 4th, 5th, and 6th instars, molt to adults with a masculinized abdomen, in contrast to control animals injected with dsGFP. Top row, dorsal view. Bottom row, ventral view. The tergal gland in wild-type males and dsBgTra females is indicated with red arrows. Red circle outlines abnormal tissue extrusion typical of dsBgTra females; zoomed-in view of this tissue is shown below. (B) Scanning electron microscopy (top row) and light microscopy (bottom row) reveal developed male-like tergal glands (shaded orange in SEMs and dissected for light microscopy) in dsBgTra females compared to wild-type (WT) females. (C) dsBgTra females have malformed, partly masculinized colleterial glands. Left column shows wild-type male accessory glands composed of seminal vesicles, utricles, uricose glands, and a conglobate gland. Right column, wild-type female colleterial gland. Center column, gland dissected from dsBgTra female is located in the same position as the wild-type colleterial gland, but shows thickened tubules reminiscent of the male accessory glands. (D) dsBgTra female gonads are deformed or intermediate between male and female gonads. Left column shows testis of a 5-day-old wild-type male. Middle column, top image shows disorganized gonad tissue in a typical 2-week-old dsBgTra female. Most individuals (n = 12) had underdeveloped ovaries with some undifferentiated tissue, some ovarioles (green arrows), and some sclerotized cuticle (green chevrons) not normally found in the ovary. Middle column, bottom shows that some dsBgTra females (n = 3) have intersex gonads composed of both ovarian and testicular tissue (indicated by green arrow). Right column shows ovaries of a 2-day-old wild-type female. (E) vitellogenin, an egg yolk protein, production is under the control of BgTra. Left: qPCR measuring relative vitellogenin expression in the fat body of males and females treated with dsBgTra. Right: relative upregulation of vitellogenin receptor transcription in the gonads of dsBgTra females, presumably due to the lack of circulating vitellogenin. vitellogenin and vitellogenin receptor gene expression was normalized to actin.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. dsBgTra reduces BgTra expression in males and females of Blattella germanica.

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. Abnormal morphology in 6th instar dsBgTra female nymphs of Blattella germanica.

In separate experiments, we injected female and male 4th, 5th and 6th instars with two overlapping double-stranded RNA sequences common to all BgTra isoforms (Figure 1B). BgTra expression levels were reduced to similar, very low levels in both males and females despite starting from a higher baseline level in females (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). Females treated with dsBgTra developed normally until the 6th instar, which took 16–21 days instead of the normal 8 days. Sixth instar female nymphs had an abnormal extrusion of tissue at the level of the last abdominal sternite (Figure 3—figure supplement 2). Like wild-type females, dsBgTra females had five visible abdominal sternites, but the last sternite had an abnormal morphology with a ‘cut away’ shape through which soft tissue was visible (Figure 3—figure supplement 2). dsBgTra female nymphs molted into masculinized adults (Figure 3). All dsBgTra-treated female nymphs that molted to adults (n = 25) showed the slender abdomen tapered at the posterior end, which is typical of males (Figure 3A), and all had well developed tergal glands (Figure 3B). To test whether the tergal glands of masculinized females were functional, we extracted the oligosaccharides from the tergal glands of 11 dsBgTra females and 10 wild-type adult males and analyzed them by mass spectrometry. All of the 26 oligosaccharides present in the wild-type male tergal glands were also observed in dsBgTra female adults; these BgTra-depleted adults did not have any additional oligosaccharides not found in wild-type adult males (Figure 4—figure supplement 1).

Internally, most adults that molted from the dsBgTra-treated female nymphs had underdeveloped ovaries containing large areas of undifferentiated tissue (Figure 3D). Some dsBgTra females had intersexual gonads (‘ovotestes’) containing both ovarian and testicular tissue (Figure 3D). The colleterial gland, which is located at the base of the abdomen and is responsible for egg case protein production, was also partly masculinized, displaying thickened tubules reminiscent of male accessory glands (Figure 3C).

In contrast, male nymphs subjected to an equivalent BgTra RNAi treatment progressed normally through development. All dsBgTra male nymphs molted into adult males with wild-type external and internal morphology (n = 20); these adults were fertile, producing broods of normal size and number.

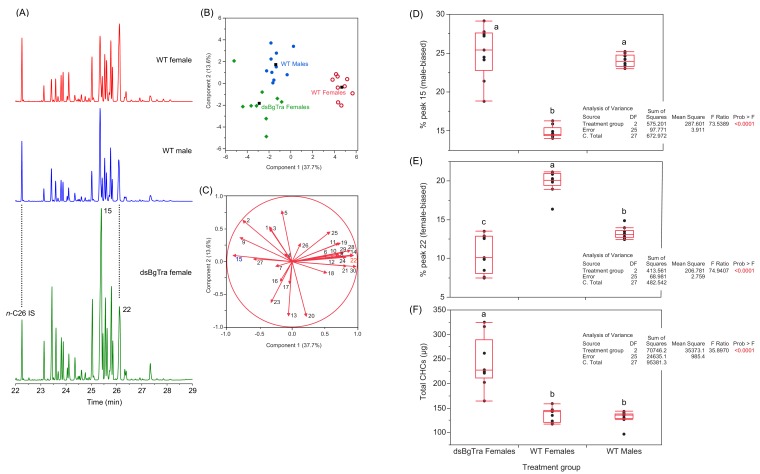

In D. melanogaster, the sex determination pathway regulates the production of sex-specific cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) (Ferveur et al., 1997; Shirangi et al., 2009). We find that in B. germanica, male and female CHC production is controlled by BgTra. The CHC profile of dsBgTra females is more similar to that of wild-type males than wild-type females; in particular, the precursor of the female contact sex pheromone is depleted in dsBgTra females, while the abundance of male-biased CHCs is increased (Figure 4—figure supplement 2). dsBgTra females have significantly more total CHCs than either wild-type males or wild-type females (Figure 4—figure supplement 2), a phenomenon likely explained by their non-functional ovaries. In wild-type females, large amounts of hydrocarbons are provisioned to the maturing oocytes (Fan et al., 2008). In ovariectomized wild-type females, some of the excess hydrocarbons which were destined to provision the ovaries are shunted to the cuticle (Schal et al., 1994); a similar process may be at work in dsBgTra females.

In addition to its female-specific effect on external and internal morphology, BgTra RNAi had a female-specific effect on gene expression. Expression of vitellogenin (yolk protein) in the fat body is high in wild-type adult females and absent in males. In dsBgTra females, vitellogenin expression was reduced to undetectable levels, similar to wild-type males (Figure 3E). Perhaps in response to the shortage of vitellogenin, expression of the vitellogenin receptor was upregulated in the gonads of dsBgTra females (Figure 3E). Overall, we conclude that BgTra, like its holometabolous insect orthologs, is required for female sexual differentiation but is dispensable in males. This is despite the fact that, in contrast to holometabolous insects, BgTra produces functional isoforms in males as well as in females.

tra represses male-specific behavior in female cockroaches

In D. melanogaster, sex-specific behavior is indirectly under the control of tra via the fruitless (fru) transcription factor (Ryner et al., 1996; Heinrichs et al., 1998; Kimura et al., 2005). fru orthologs also control courtship behavior in other dipterans and in B. germanica, and fru shows conserved sex-specific splicing across holometabolous insects (Meier et al., 2013; Clynen et al., 2011; Salvemini et al., 2010). In D. melanogaster females, Tra prevents expression of fru isoforms that direct male courtship behavior (Heinrichs et al., 1998). To test whether BgTra also controls sex-specific behavior in B. germanica, we exposed ten masculinized dsBgTra female adults to antennae clipped from sexually mature wild-type females. In typical courtship, wild-type males are stimulated by a contact sex pheromone on the female antenna. Upon contact with a female antenna, wild-type males orient their abdomen towards the antenna and raise their wings to display the tergal glands. As the female feeds on tergal gland secretions, the male extends his abdomen, grasps the female’s genitalia, and copulation follows (Roth and Willis, 1952). Wild-type females do not show the wing-raising behavior. Nine out of ten masculinized dsBgTra female adults showed the same response as wild-type males, although the mean lag time between introduction of the female antenna and wing raising was longer in dsBgTra females (mean = 19.9 s) than in wild-type males (mean = 4.9 s) (Welch’s t-test, p=0.02) (Figure 4A,B). These results indicate that dsBgTra females, unlike wild-type females, perceive wild-type female sex pheromone and respond with courtship behavior. Similar to its function in holometabolous insects, BgTra is required to repress male-specific behavior in B. germanica.

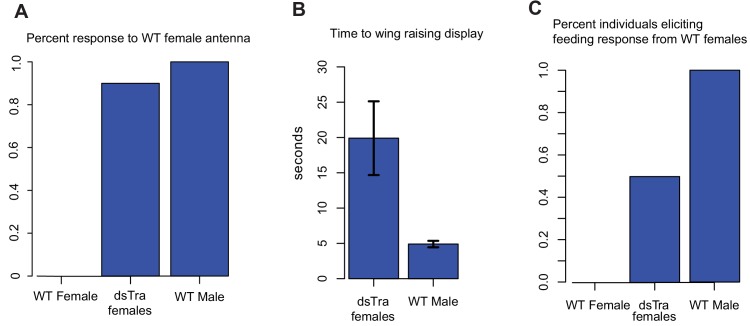

Figure 4. dsBgTra females perform male courtship behavior and elicit courtship responses from wild-type females.

In courtship, wild type male Blattella germanica raise their wings to display their tergal gland. When courtship is successful, wild type females feed upon the secretions of this gland prior to copulation. dsBgTra females (n = 10), wild-type females (n = 10), and wild-type males (n = 10) were exposed to an antenna clipped from a wild-type, 7 day old virgin female, and their response times in seconds were compared. (A) Nine out of ten dsBgTra females performed the stereotypical male wing-raising courtship display in response to a female antenna compared to 0/10 of wild-type females within the one minute of observation time. (B) However, dsBgTra females took longer than wild-type males to respond with the wing-raising display. Wild-type females did not respond to the stimulus throughout the duration of the one-minute observation time. (C) 5/10 dsBgTra females elicited feeding response from wild-type females after raising their wings. Wild-type females, lacking tergal glands, do not elicit a feeding response from other wild-type females.

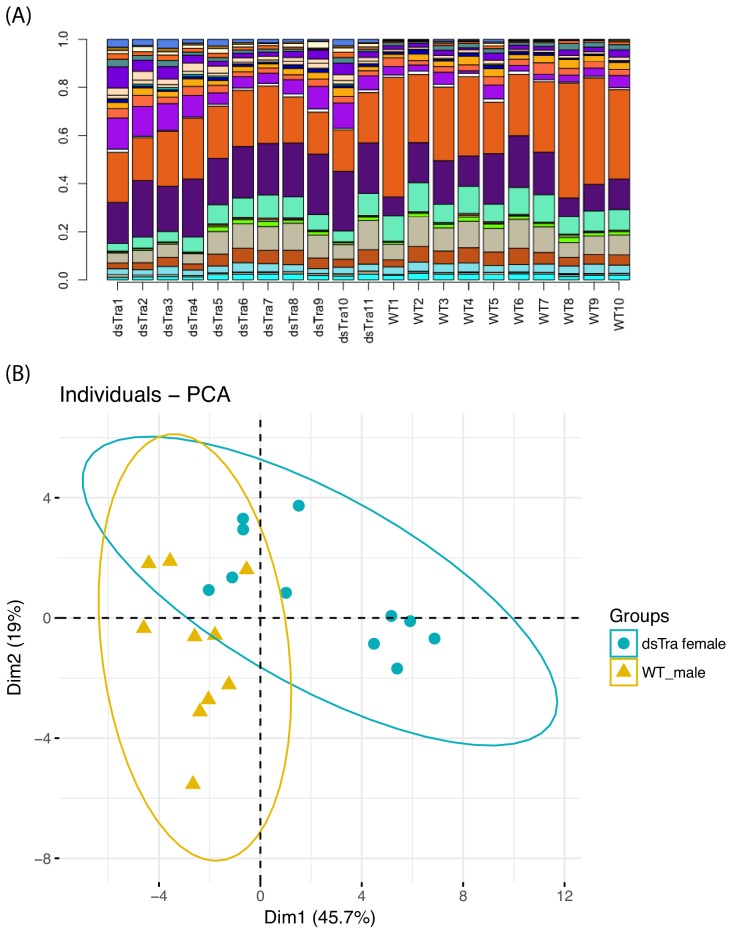

Figure 4—figure supplement 1. BgTra controls sex-specific oligosaccharide synthesis in tergal glands (A) Relative abundance of oligosaccharides in tergal glands derived from dsBgTra females (dsTra1-dsTra10) and wild-type males (wt1-wt10).

Figure 4—figure supplement 2. BgTra controls production of sex-specific cuticular hydrocarbons.

In a separate set of experiments, we tested whether wild-type females respond to the wing-raising display of masculinized dsBgTra females. In five out of ten instances, wild-type females began feeding on the tergal glands of dsBgTra females, confirming the functionality of these glands (Figure 4C). Overall, the results indicate that dsBgTra females express male sexual traits that attract wild-type females.

BgTra is necessary for female, but not male embryonic viability

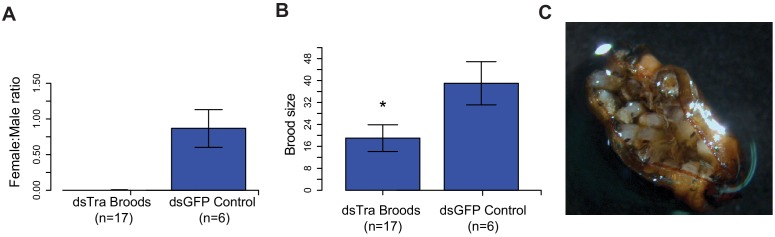

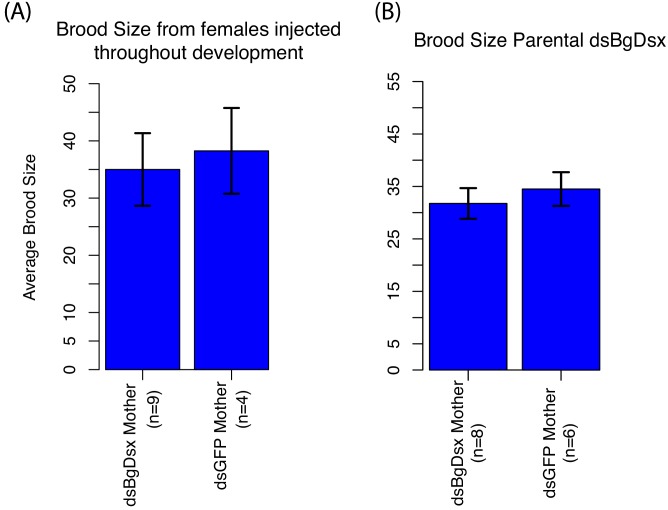

We also found that BgTra is crucial for female embryonic development. Three-day-old adult females injected with dsBgTra produced all-male broods (Figure 5A), suggesting that maternal dsBgTra treatment either masculinizes or kills female progeny. Female-specific lethality appears more likely for two reasons. First, the number of offspring in the all-male broods from dsBgTra females was about 50% of the offspring from dsGFP-injected control females (Figure 5B). Second, all the broods that hatched from dsBgTra mothers contained dead embryos remaining in the ootheca (Figure 5C). One possibility is that BgTra may affect dosage compensation in the cockroach, which has male, XX/XO sex determination (Stevens, 1905). When T. castaneum females are injected with dsRNA targeting tra, they also produce all-male broods with much reduced survival (Shukla and Palli, 2012a). These results suggest that tra could either have a deeply conserved role in dosage compensation, or has repeatedly evolved a role in this process.

Figure 5. Maternal knockdown of BgTra in Blattella germanica results in all-male broods..

(A) Females injected with dsBgTra (n = 17) three days after emergence and mated to wild type males produced all-male broods, compared to control females injected with dsBgGFP (n = 6) (B) Brood sizes from mothers injected with dsBgTra were significantly smaller than the dsGFP controls (Welch’s t-test, p=0.001). (C) Image of a typical ootheca (egg case) from a dsBgTra mother that failed to hatch. Of 22 mothers injected with dsTra, five egg cases failed to hatch completely. The remaining oothecae had 5–19 dead embryos remaining within it after all males had emerged. Variability in the number of dead embryos can be attributed to surviving offspring eating dead embryos, which was observed by the authors.

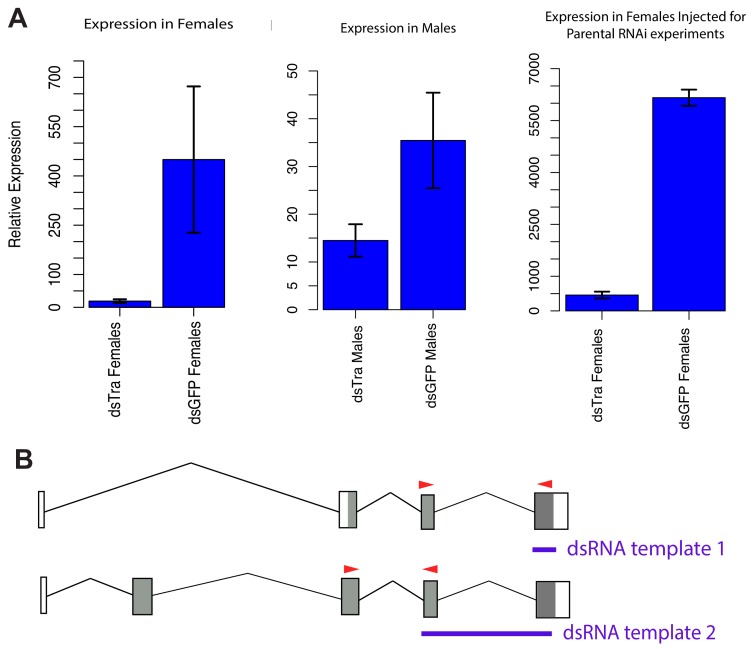

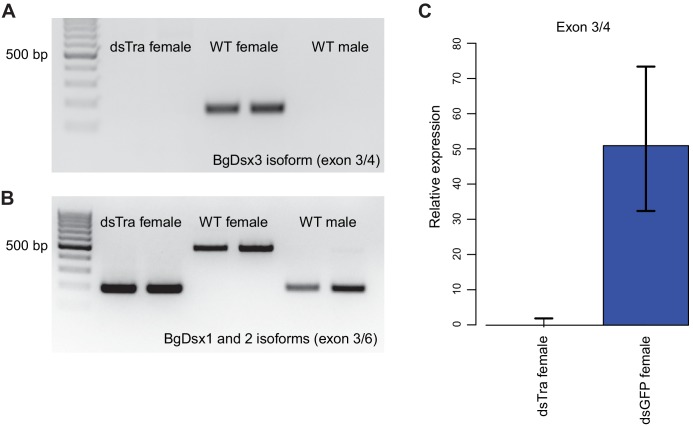

B. germanica BgTra controls sex-specific splicing of BgDsx

In B. germanica, BgDsx has two female-specific and one male-specific isoform (Figure 2C). Because dsx splicing is under the control of tra in most holometabolous insects, we tested whether BgTra RNAi affected the production of sex-specific BgDsx isoforms. qPCR and RT-PCR revealed that in dsBgTra females, BgDsx splicing switched completely from the female to the male pattern (Figure 6). Neither of the two female-specific transcripts were present in dsBgTra females, whereas the male-specific BgDsx isoform was present in abundance similar to wild-type males (Figure 6). As expected, no change in BgDsx splicing was observed in dsBgTra males (data not shown). This is similar to the pattern of tra-dependent female dsx splicing seen in holometabolous insects such as D. melanogaster and T. castaneum (Shukla and Palli, 2012b; Inoue et al., 1992). However, in contrast to holometabolous insects, male-specific dsx splicing in the cockroach is unlikely to be due to the absence of functional Tra protein in males, since BgTra produces the same full-length transcript isoforms in both sexes (Figure 1D–F).

Figure 6. BgTra controls sex-specific splicing of BgDsx.

(A) RT-PCR showing that the female-specific BgDsx exon 3/4 junction (Figure 2B,C) is absent in dsBgTra females (B) RT-PCR showing that the male-specific BgDsx exon 3/5 junction (Figure 2B) is present in dsBgTra females. dsBgTra females do not express any of the female-specific BgDsx isoforms. (C) qPCR shows complete absence of the female-specific BgDsx exon 3/4 junction in dsBgTra females.

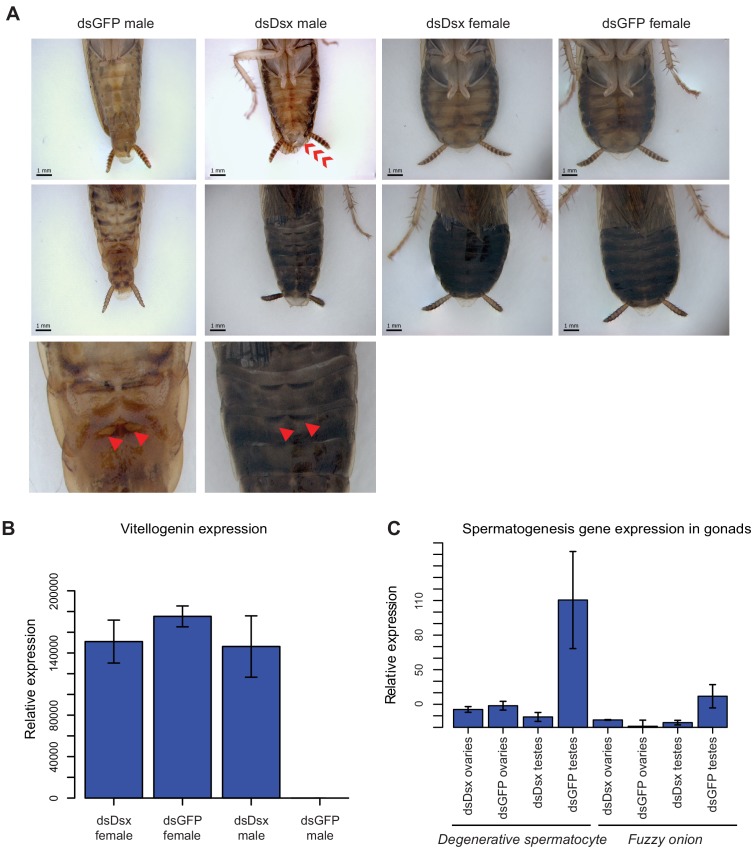

BgDsx is necessary for male-specific but not female-specific sexual differentiation

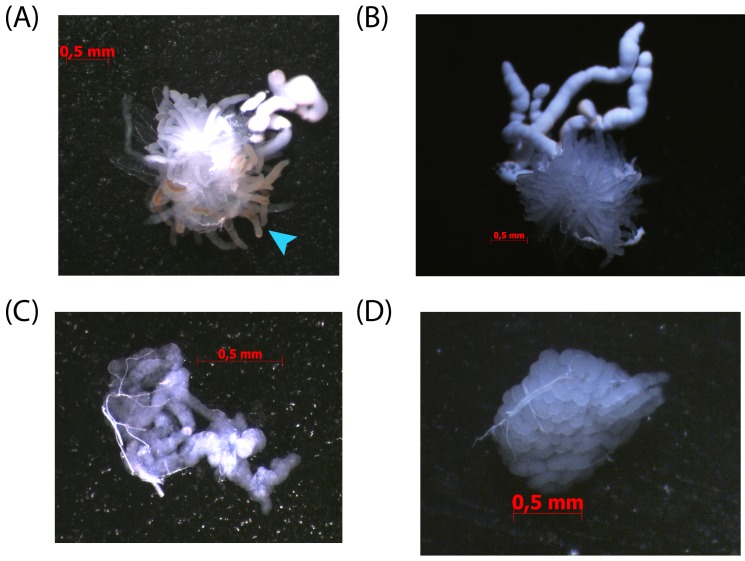

In separate experiments, we injected three different dsRNAs targeting BgDsx. Two of these dsRNAs targeted the DNA-binding domain shared by male and female BgDsx transcripts; a third dsRNA targeted the Dsx Dimerization Domain, also shared between males and females (Figure 2). Surprisingly, we observed that BgDsx transcript abundance increased after injection with dsBgDsx in both males and females (Figure 7—figure supplement 1), making it difficult to measure the efficiency of RNAi treatment. Increased expression of a target gene after dsRNA treatment has been previously described (Nakamura and Extavour, 2016), and there is not always a strong relationship between transcript abundance and RNAi phenotype (Xiang et al., 2017). Most plausibly, the upregulation observed after a dsRNA treatment results from a rebound effect on the transcription of the targeted gene. Although the effect of RNAi on BgDsx transcript abundance was similar in males and females, its effect on adult morphology and downstream gene expression was markedly different between the two sexes.

Both males and females injected with dsBgDsx during 4th, 5th, and 6th instars progressed normally through nymphal development. However, upon the adult molt, all males injected with dsBgDsx targeting the DM domain (n = 23) had an abnormal extrusion of tissue at the tip of their abdomen (Figure 7A). This extrusion appears to be an outgrowth of the ejaculatory duct (Figure 7—figure supplement 2). A range of body shapes was observed in these adults, from slender abdomens typical of wild-type males to the rounder abdomens typical of females. The tergal glands of dsBgDsx males also ranged from fully developed to severely reduced (Figure 7A). Moreover, the dsBgDsx males showed darker pigmentation, similar to wild-type females, especially on the dorsal side (Figure 7A). Because of their malformed ejaculatory ducts, dsBgDsx males were not able to mate, making it impossible to assess their fertility. Dissection of dsBgDsx males revealed apparently normal testes (n = 15), with morphologically normal sperm indistinguishable from wild-type B. germanica sperm (n = 3). However, the conglobate glands of dsBgDsx males failed to mature over the first week of adult life, while tissue discoloration was observed in the utricles (Figure 7—figure supplement 3).

Figure 7. dsBgDsx RNAi in Blattella germanica feminizes males but has no effect in females (A) dsBgDsx males have reduced tergal glands (red arrow), darker female-like pigmentation, and an extrusion of tissue at the distal end of the abdomen (red chevron) compared to dsGFP injected males (see also Figure 7—figure supplement 3).

Females are unaffected by dsBgDsx treatment. Bottom row shows zoomed-in view of dorsal segments containing the tergal gland. The openings from which tergal glands secrete their oligosaccharides and lipids in dsGFP males (red arrows) are greatly reduced in dsBgDsx males. (B) BgDsx represses vitellogenin expression in males, but has no effect in females (n = 3 biological replicates per treatment). (C) BgDsx controls the expression of two spermatogenesis-related genes in males, but has no effect on their expression in females. qPCR showing the expression of two genes important for Drosophila melanogaster spermatogenesis, degenerative spermatocyte and fuzzy onions, relative to actin (n = 3 biological replicates for all columns).

Figure 7—figure supplement 1. BgDsx RNAi causes an increase in BgDsx transcript abundance in both males and females of Blattella germanica.

Figure 7—figure supplement 2. Representative sampling of tissue extrusions found in dsBgDsx males of Blattella germanica (light blue arrowheads).

Figure 7—figure supplement 3. The conglobate glands and utricles of dsBgDsx males of Blattella germanica fail to properly mature.

Figure 7—figure supplement 4. BgDsx has no effect on brood size in females of Blattella germanica that were injected with dsBgDsx either at multiple stages throughout nymphal development (A) or as virgin adult females (B).

Females injected with BgDsDsx targeting either the DM domain or the Dsx Dimerization domain molted into adults with no visible external abnormalities (Figure 7A), and had apparently normal gonads and reproductive tracts. Adult dsBgDsx females elicited courtship from wild-type males, mated with them, and produced broods whose size was not significantly different from those of control females (Figure 7—figure supplement 4). When virgin females received dsBgDsx injections 3 days before mating, they produced broods of normal size with normal sex ratio (Figure 7—figure supplement 4). Thus, it appears that BgDsx controls many though not all male-specific traits, but has no obvious effect on female-specific development. This is clearly different from holometabolous insects, where dsx plays active roles in both male and female sexual differentiation, and where dsx mutants develop into intersexes that are intermediate in phenotype between males and females (Baker and Ridge, 1980).

To test whether BgDsx controlled sex-specific gene expression, we examined the expression of two genes, fuzzy onions (fzo) and degenerative spermatocyte (des), that function in spermatogenesis in D. melanogaster and have homologs throughout metazoans (Hales and Fuller, 1997; Mozdy and Shaw, 2003; Endo et al., 1996; Endo et al., 1997). Expression of both genes was greatly reduced in the testes of dsBgDsx males compared to the testes of wild-type males, whereas no significant effect was seen in the ovaries of dsBgDsx females (Figure 7C). Conversely, the female-specific vitellogenin gene was strongly upregulated in the fat body of dsBgDsx males compared to wild-type males, reaching the level normally seen in wild-type females (Figure 7B). In contrast, vitellogenin expression was not affected in dsBgDsx females (Figure 7B). Together, these results suggest that BgDsx controls downstream gene expression in males but not in females. This pattern, while different from holometabolous insects, has been observed in the hemipteran N. lugens, where a dsx ortholog has a female-specific isoform that appears to play no role in vitellogenin production (Zhuo et al., 2018). In D. melanogaster, yolk protein genes are upregulated by the female-specific isoform of dsx and repressed by the male-specific isoform, so that dsx mutants show an intermediate level of yolk protein gene expression (Coschigano and Wensink, 1993).

Discussion

The sex determination pathway must by necessity produce a bimodal output: male or female. How this output is achieved varies considerably across animal taxa and can rely on molecular processes as different as systemic nuclear hormone signaling, post-translational protein modification, or, in the case of insects, sex-specific alternative splicing. In this paper, we examined sexual differentiation in hemimetabolous insects to investigate the evolutionary origin of this unique mode of sexual differentiation.

The canonical transformer-doublesex pathway of holometabolous insects has three derived features that are not found in non-insect arthropods or in non-arthropod animals: (Charlesworth, 1996) the presence of distinct male- and female-specific splicing isoforms of dsx that play active roles in both male and female sexual development; (Graves, 2006) the production of functional Tra protein in females but not males; and (Ellegren, 2000) the control of female-specific dsx splicing by Tra. Our work in hemimetabolous insects suggests that these elements evolved separately and at different times, and that the definitive tra-dsx axis was assembled in a stepwise or mosaic fashion.

Sex-specific splicing of doublesex predates its role in female sexual differentiation

Distinct male and female dsx isoforms have been reported in all holometabolous insects examined, as well as in the planthopper N. lugens (Hemiptera) (Zhuo et al., 2018). Our results confirm the presence of male and female dsx isoforms in another hemipteran, R. prolixus, and show that this pattern is conserved through Blattodea – the most basal insect order studied to date. This suggests that sex-specific splicing of dsx was likely the first feature of the canonical insect sexual differentiation pathway to evolve. In P. humanus (Phthiraptera), the alternative splicing of dsx follows the usual pattern, with a common N-terminal domain and alternative C-termini, but we found that both dsx isoforms are present in both sexes. Previous work in the hemipteran Bemisia tabaci also failed to detect sex-specific dsx isoforms (Guo et al., 2018), suggesting that some insects may have secondarily lost sex-specific dsx splicing.

We did not detect any role for the cockroach dsx gene in female sexual differentiation in B. germanica. Recent work in the Hemipteran N. lugens produced similar results: despite the presence of male and female dsx isoforms, N. lugens females developed normally following dsx RNAi knockdown, while the males were strongly feminized (Zhuo et al., 2018). Together, these results suggest that in at least some hemimetabolous insects, dsx is spliced as in holometabolous insects, but may function as in the crustacean D. magna, where dsx is necessary for male but not female development (Kato et al., 2011).

The existence of a female-specific dsx isoform in the absence of a female-specific dsx function is, of course, surprising. Although we examined multiple features of female external and internal anatomy, gene expression, behavior, and reproduction in B. germanica dsBgDsx females, we cannot rule out that dsx performs some subtle or spatially restricted function in female cockroaches. Such relatively minor and tissue-specific role, if it exists, could provide a crucial stepping stone in the origin of the classical dsx function as a bifunctional switch that is indispensable for female as well as male development. One possibility is that, similar to other transcription factors, dsx originally evolved alternative splicing as a way of promoting the development of different cell types. If some dsx isoforms evolved functions that were dispensable for male sexual development, dsx could gradually lose its ancestral pattern of male-limited transcription, opening the way for the evolution of new isoforms with first subtle, but eventually essential, functions in females.

The role of train sexual differentiation predates canonical sex-specific splicing of tra

The opposite pattern is observed for transformer, which apparently evolved a sex-specific role before that role came to be mediated by a male-specific stop codon. In most holometabolous insects, alternative splicing of tra produces a functional protein in females but not in males, due to a premature stop codon in a male-specific exon near the 5’ end of tra. In hemimetabolous insects, we only observe this type of sex-specific splicing in R. prolixus. In B. germanica and P. humanus, full-length and presumably functional Tra proteins that include all of the important functional domains are produced in both males and females. The female-limited function of Tra in the cockroach could result from higher expression of truncated BgTra isoforms in females (see below), or from sex-specific expression of unknown cofactors of Tra. In either case, the function of tra in female sexual differentiation predates the evolution of female-limited Tra protein expression.

Although they lack the canonical sex-specific splicing observed in holometabolous insects, the tra genes of B. germanica and P. humanus show a different pattern of alternative splicing affecting the CAM domain, which plays a role in tra autoregulation in holometabolous insects (Tanaka et al., 2018). In some tra isoforms, read-through of an exon containing the 5’ half of the CAM domain results in a premature stop codon; in B. germanica and P. humanus, these transcripts are found in both sexes. In BgTra, isoforms with an intact reading frame come in two types. Some of these intact isoforms contain an in-frame exon spliced into the middle of the CAM domain; in the others, this exon is spliced several base pairs upstream of the stop codon, producing an uninterrupted CAM domain. In P. humanus, we only isolated tra isoforms with an exon interrupting the CAM domain. The splice junction in the middle of the CAM domain is conserved in holometabolous insects (Hediger et al., 2010), and the amino acid residues flanking this junction are necessary for female-specific autoregulation of tra in the housefly (Tanaka et al., 2018). It remains to be determined whether the CAM domain is involved in tra autoregulation in hemimetabolous insects, but if so, the truncated or interrupted isoforms would likely be incapable of autoregulation, with potentially important consequences for the splicing of tra and its downstream targets. Interestingly, the evolution of the canonical holometabolous splicing of tra, with a male-specific premature stop codon, coincided with a loss of tra isoforms with an interrupted CAM domain. In fact, the splicing pattern of tra in R. prolixus suggests that the male-specific stop codon originally evolved in the middle of the CAM domain (Figure 1A). This change may indicate a transition from an ancestral state where both sexes had functional as well as non-functional Tra isoforms, to the derived holometabolous condition where functional Tra protein is confined to females, and non-functional Tra to males.

The role of tra in regulating dsx splicing predates sex-specific expression of Tra protein

Although the function of tra in female sexual development in B. germanica does not appear to be mediated by dsx, we find that tra is necessary for sex-specific dsx splicing in the cockroach, as it is in all holometabolous insects except Lepidoptera (Kiuchi et al., 2014). The mechanism of dsx regulation by tra is likely to be different in B. germanica compared to holometabolous insects. In the latter, functional Tra protein is absent in males but present in females, where it dimerizes with the RNA-binding protein Tra-2 to regulate the splicing of dsx and fru (Hoshijima et al., 1991; Heinrichs et al., 1998; Nagoshi et al., 1988). In the cockroach, however, full-length Tra proteins containing all the functional domains are expressed at similar levels in both sexes, so that male-specific splicing of dsx in males cannot be explained by lack of Tra. It could be due instead to an interaction of Tra with different binding partners in males vs females. We note that while the D. melanogaster Tra protein does not contain an RNA-binding domain and does not bind to RNA without Tra-2, the cockroach Tra protein, as well as those of some other insects and crustaceans, contain predicted RNA recognition motifs (Inoue et al., 1992). Thus, it is possible that Tra first evolved its function in regulating alternative splicing as a broadly acting RNA-binding protein that worked in concert with other splicing factors, before losing its ability to bind RNA and becoming a dedicated partner of Tra-2 with a narrow range of downstream targets. If so, the situation we find in B. germanica may represent a transitional stage in the evolution of the canonical tra-dsx axis, where dsx is one of many Tra targets, rather than the main mediator of its female-specific function. In this scenario, the tra-dsx axis evolved via merger between expanding dsx function (from males to both sexes) and narrowing tra function (from a general splicing factor to the dedicated regulator of dsx).

Evolution of the insect sexual differentiation pathway: stepwise or mosaic?

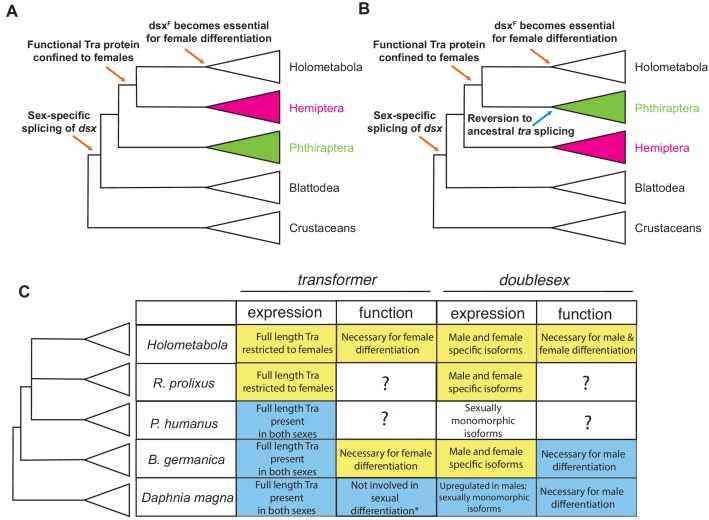

A more extensive sampling of hemimetabolous insects will no doubt be necessary to reconstruct the full series of events that produced the familiar holometabolous mode of sexual differentiation, and to determine the timing of the key synapomorphies among the variety of lineage-specific changes. Based on our limited taxon sampling, we can propose a tentative model. We suggest that the canonical insect mechanism of sexual differentiation based on sex-specific splicing of dsx and tra evolved gradually in hemimetabolous insects, and may not have been fully assembled until the last common ancestor of the Holometabola (Figure 8). In crustaceans, mites, and non-arthropod animals, dsx and its homologs act as male-determining genes that are transcribed in a male-specific fashion and are dispensable for female sexual differentiation (Kato et al., 2011; Li et al., 2018; Pomerantz and Hoy, 2015). One of the earliest events in insects was the evolution of sex-specific dsx splicing, where dsx is transcribed in both sexes but produces alternative isoforms in males vs females. We do not know whether Tra was involved in sex-specific dsx splicing from the beginning, or evolved this function later; in either case, the function of tra in controlling female sexual differentiation may well predate its role in regulating dsx splicing. Eventually, however, Tra became essential for the expression of female-specific dsx isoforms. At the next step, expression of functional Tra protein became restricted to females due to the origin of a male-specific exon with a premature stop codon at the 5’ end of the tra gene. As this process unfolded, female-specific dsx isoforms gradually evolved female-specific functions, which may have been minor at first but became essential at or before the origin of holometabolous insects (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Evolutionary assembly of the insect sexual differentiation pathway.

Uncertainty in the relationships among Hemiptera, Phthiraptera, and Holometabola (Misof et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2018; Freitas et al., 2018; Li et al., 2015) means that the sequence of events in the evolution of the tra-dsx axis is unclear. If Hemiptera (pink) are the sister group of Holometabola, the key molecular innovations have evolved in a stepwise order (A). If Phthiraptera (green) are the sister of Holometabola instead, the evolution of the tra-dsx axis must have followed a more mosaic pattern, with at least some secondary reversions (B). (C) Summary of tra and dsx expression and function in the three hemimetabolous insect orders in comparison to the canonical holometabolous mechanism and to Daphnia. No effect on sexual differentiation has been reported following tra knock-down in Daphnia (asterisk) (Kato et al., 2011). Hypothesized ancestral states are shown in blue; hypothesized derived states in yellow. Within Holometabola, subsequent events in the evolution of the tra-dsx axis include a secondary loss of tra in Lepidoptera, loss of the CAM domain of Tra in Drosophila, and the evolution of Sex-lethal (Sxl) as the upstream regulator of tra splicing in Drosophila.

The details of this model depend on the phylogenetic relationships of hemimetabolous insect orders and the holometabolous clade, which remain controversial. Despite rapidly growing amounts of data, phylogenetic analyses have had limited success in identifying the closest outgroup to Holometabola. In some phylogenies, that outgroup is Hemiptera (Figure 8A) (Sasaki et al., 2013); in others it is Psocodea, which includes lice (Figure 8B) (Ishiwata et al., 2011; Misof et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2018); in all molecular phylogenies to date, the relevant nodes are not strongly supported. In fact, some phylogenies show Hemiptera and Psocodea as a polytomy (Freitas et al., 2018; Li et al., 2015). The holometabolous splicing pattern of tra is seen in R. prolixus but not in the cockroach or louse, suggesting that either Hemiptera are the closest outgroup to holometabolous insects, or the splicing of tra in P. humanus represents a reversion to an ancestral state (Figure 8).

Our study of transformer and doublesex expression and function across hemimetabolous insects establishes a broad outline for the origin of the unique insect-specific mode of sexual differentiation via alternative splicing. Comparative and functional work in other basal insects, non-insect hexapods, and crustaceans will be needed to determine the ancestral functions of tra, the roles of female-specific dsx isoforms in hemimetabolous insects, and other details of this emerging model.

Materials and methods

DMRT and SR family gene trees

To differentiate dsx orthologs from other DMRT paralogs, we made phylogenetic trees of arthropod DMRT genes. DMRT protein sequences from previously studied arthropods (Wexler et al., 2014) (D. melanogaster, A. mellifera, B. mori, T. castaneum, R. prolixus, D. magna, and I. scapularis) were used as queries (Supplementary file 4) in BLASTP searches of predicted gene models from 22 other arthropod species (Supplementary file 1). Hits with e-values lower than 0.01 were retained and added to the file that included the original DMRT queries. This sequence file was multiply aligned with the MAFFT program using the –geneafpair setting (Katoh et al., 2002). Upon alignment, sequences without the characteristic DMRT DNA-binding domain CCHHCC motif were discarded, and the entire multiple alignment was rerun.

We used a similar procedure to identify tra orthologs in hemimetabolous insects. For the RS family gene tree, the query file consisted of Tra, Transformer-2, Pinin, and SFRS protein sequences from D. melanogaster, B. germanica, and D. magna (Supplementary file 5), and a BLASTP search was performed on the same arthropod species, retaining hits with e-values <0.01. After sequences were multiply aligned with the MAFFT algorithm, gaps in the alignment were trimmed with trimAl using the –automated1 setting (Capella-Gutierrez et al., 2009).

To construct gene trees for DMRT and RS families, prottest3.4 (Darriba et al., 2011) was used for model selection for the amino acid alignment; RAxML8.2.9 was used to build a maximum likelihood tree with a WAG + G model for both the SR family gene tree and the DMRT gene tree (Stamatakis, 2014).

Cockroach husbandry

Functional experiments were conducted with two German cockroach B. germanica strains: Orlando Normal, obtained from Coby Schal’s laboratory at North Carolina State University; and Barcelona strain from Xavier Belles’s laboratory at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology. B. germanica were kept in an incubator at 29°C and fed Iams dog food ad libitum.

PacBio isosequencing

Pacific Biosystems (PacBio) isosequencing was performed separately on male and female B. germanica tissues. We reasoned that sexually dimorphic tissues were likely to express doublesex and transformer, including any sex-specific isoforms of these genes that might exist. We extracted RNA from reproductive organs (gonad and colleterial glands) and fat body of a seven day old virgin female and from reproductive organs (gonad, conglobate gland, accessory glands, and seminal vesicles) and fat body of two seven day old males for library preparation. Tissues were pooled in Trizol, and a separate RNA extraction was done for each sex. Clontech SMARTER PCR cDNA synthesis kit and PrimeSTAR GXL DNA polymerase were used for cDNA synthesis; a cDNA SMRTbell kit was then used to add sequencing adapters. The male and female libraries were run on separate SMRT cells on the PacBio Sequel instrument, and the PacBio SMRTLink software was used for downstream data processing. We used tBLASTn to search the high and low quality polished consensus isoforms for BgTra and BgDsx transcripts. We obtained additional isoforms searching the sets of circular consensus sequences. All splice junctions from BgTra and BgDsx Isosequencing-generated transcripts were verified with RT-PCR. When the coding sequence of PacBio-generated isoforms disagreed with the B. germanica genome, sequence was verified by Sanger sequencing.

Illumina RNA sequencing

To identify dsx and tra isoforms in R. prolixus and P. humanus, we used Trizol to extract RNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For R. prolixus, we extracted RNA separately from male and female gonad tissue. For P. humanus, adults were sexed and pooled before RNA extraction. For both insects, 1 µg of RNA was used to construct each library using the NEBNext kit and Oligos. Libraries were quantified with NEBNext Quant Kit and sequenced using 150 bp paired-end reads on an Illumina HiSeq4000 machine. Poor quality reads were discarded with FastQC (default parameters) (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) and trimmed with trimmomatic 0.36 using suggested filters (LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:36) (Bolger et al., 2014). Trinity 2.1.1 with default parameters was used for de novo assembly of the male and female transcriptomes (Haas et al., 2013).

5’/3’ RACE

The Clontech 5’/3’ SMARTer Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) kit was used to make RACE libraries from male and female R. prolixus, P. humanus, and B. germanica total RNA. All RNA extractions were performed using Invitrogen TRIzol Reagent according to the provided protocol. For R. prolixus and B. germanica, we combined gonad tissue, reproductive tract tissue, and fat body from a single male or a single female to make the male and female RACE libraries, respectively. P. humanus RNA was extracted from pools of between 6–10 whole adult males or females.

For all species, 5’ RACE cDNA fragments were amplified using gene-specific primers (Supplementary file 7) and kit-provided UPM primers and Clontech Advantage 2 Polymerase. Thermocycling conditions were: 95°C for two mins; 36 cycles of (95°C for 30 s, a primer-specific annealing temperature for 30 s, 68°C for 2.5 min); 95°C for 7 min. 3’ RACE cDNA fragments were amplified using single or nested PCRs with gene-specific primers and either Clontech Advantage 2 Polymerase or SeqAmp DNA Polymerase (Supplementary file 7). Clontech Advantage 2 PCRs were performed using the above cycling conditions, and SeqAmp DNA Polymerase touchdown thermocycling conditions were: 5 cycles of (94°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1–2 min); 5 cycles of (94°C for 30 s, 68°C for 1–2 min); 35 cycles of (94°C for 30 s, 66°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1–2 min). Nested PCRs used diluted (1:50) outer PCRs as template, a nested gene-specific primer and the UPM short primer, and 25 cycles of (94°C for 30 s, 65°C for 30 s, 72°C for 2 min). All PCR products were gel-purified using Qiagen QIAquick or Macherey-Nagel NucleoSpin gel and PCR clean up kits. PCR products produced by Advantage 2 Polymerase were cloned into the Invitrogen TOPO PCRII vector and SeqAmp DNA Polymerase PCR products were cloned into linearized pRACE vector (provided with the SMARTer RACE kit) with an In-Fusion HD cloning kit. Between 6–10 colonies were Sanger sequenced per PCR reaction with M13F-20 and M13R sequencing primers.

Reverse-transcription PCR tests of isoform sex-specificity