Abstract

A number of case-control studies regarding the association of the polymorphisms in the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) genes with the risk of cancer have yielded inconsistent findings. Therefore, we have conducted a comprehensive, updated meta-analysis study to identify the impact of PD-1 and PD-L1 polymorphisms on overall cancer susceptibility. The findings revealed that PD-1 rs2227981 and rs11568821 polymorphisms significantly decreased the overall cancer risk (Odds Ratio (OR) = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.68–0.99, p = 0.04, TT vs. CT+CC; OR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.67–0.94, p = 0.006, AG vs. GG, and OR = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.70–0.96, p = 0.020, AG+AA vs. GG, respectively), while PD-1 rs7421861 polymorphism significantly increased the risk of developing cancer (OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.02–1.33, p = 0.03, CT vs. TT). The PD-L1 rs4143815 variant significantly decreased the risk of cancer in homozygous (OR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.41–0.94, p = 0.02), dominant (OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.50–0.97, p = 0.03), recessive (OR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.60–0.96, p = 0.02), and allele (OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.63–0.96, p = 0.02) genetic models. No significant association between rs2227982, rs36084323, rs10204525, and rs2890658 polymorphisms and overall cancer risk has been found. In conclusions, the results of this meta-analysis have revealed an association between PD-1 rs2227981, rs11568821, rs7421861, as well as PD-L1 rs4143815 polymorphisms and overall cancer susceptibility.

Keywords: apoptosis, PD-1, PD-L1, polymorphism, cancer, meta-analysis

1. Introduction

Cancer, a main public health issue is the leading cause of death globally. It was estimated that there will be about 18.1 million new cases of cancer and 9.6 million cancer deaths in 2018 [1]. Thus, the etiology and pathogenesis of cancer has not been elucidated completely and their understanding is decisive. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have simplified the search for potential genetic variants that are implicated in many diseases including cancer and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are well studied genetic variations found in human genome. The number of SNPs that have so far been identified to play an important role in cancer susceptibility is significant [2]. It has been proposed that the immune system plays a key role in resisting and eliminating cancer cells and can affect cancer susceptibility. One of the main hallmarks of cancer cells is the immune suppression and evasion [3].

Tumor cells express the programmed death-1-ligand 1 (PD-L1) as an adaptive, resistant mechanism to suppress the inhibitory receptor, namely programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) in order to evade host immunosurveillance [4]. PD-1, also known as PD1 and CD279, is a cell surface immunosuppressive receptor belonging to immunoglobulin superfamily and is encoded by the PDCD1 gene [5,6,7]. PD-1, is a negative regulator of the immune system and is expressed on CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, NKT cells, B cells, and monocytes [8,9]. The antitumor CD8+ T cells exhibit preferential expression of PD-1 leading to their exhaustion and functional impairment, which in turns lead to attenuated tumor-specific immunity disseminating tumor progression [10,11]. The PD-1 blockade elevates the magnitude of T cell response such as proliferation of T cells and production of effector cytokines [12]. Additionally, PD-L1 signaling through conserved sequence motifs confers resistance of cancer cells towards proapoptotic interferon (IFN)-mediated cytotoxicity [13].

PD-1/PD-L1 axis is an important pathway to maintain immune tolerance and prevent autoimmune diseases in the evolution of immunity [14,15,16]. Furthermore, it influences the balance between tumor immune surveillance and immune resistance [17,18]. Elevated PD-L1 expression in tumor cells or tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) leads to the exhaustion of T cells [19], and hence attenuated tumor-specific immunity disseminating tumor progression [20]. Gene polymorphisms might affect the normal process of gene activation and transcriptional initiation, hence influence the quantity of mRNA and encoded protein [21]. Both PD-1 and PD-L1 are polymorphic. Several studies investigated the association between genetic polymorphisms of PD-1 and PD-L1 genes and the risk of various cancers, but the finding are still inconclusive [5,6,7,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Thus, we performed a comprehensive meta-analysis in order to study the association of polymorphisms in PD-1 (rs2227981, rs2227982, rs11568821, rs7421861, rs36084323, and rs10204525) and PD-L1 (rs4143815, and rs2890658) with the risk of cancer. The locations and base pair positions of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in PD-1 and PD-L1 genes are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Locations and base pair positions of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in PD-1 and PD-L1 genes.

| Gene Name | db SNP rs # ID a | Chromosome Position | Location | Base Change | Amino Acid Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD-1 | rs2227981 | chr2:241851121 | Upstream | C/T | - |

| rs2227982 | chr2:241851281 | Exon | C/T | Ala215Val | |

| rs7421861 | chr2:241853198 | Intron | T/C | - | |

| rs11568821 | chr2:241851760 | Intron | G/A | - | |

| rs36084323 | chr2:241859444 | Upstream | G/A | - | |

| rs10204525 | chr2:241850169 | 3′UTR | A/G | - | |

| PD-L1 | rs4143815 | chr9:5468257 | 3′UTR | G/C | - |

| rs2890658 | chr9:5465130 | Intron | A/C | - |

a db = databases; rs # = reference SNP #; UTR: untranslated region.

2. Results

2.1. Study Characteristics

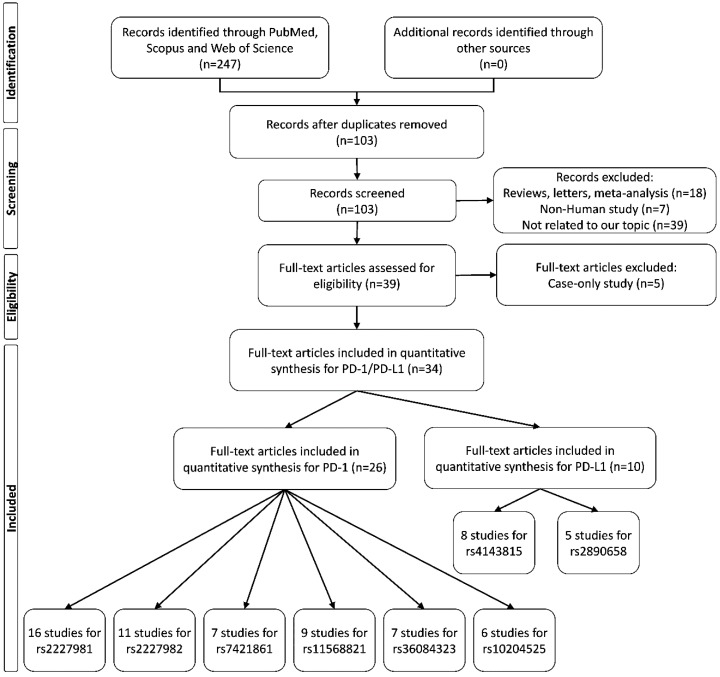

A flow diagram of the study selection process is shown in Figure 1. For PD-1 polymorphisms, 54 case-control studies from a total of 26 articles [5,6,7,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,52] examining the associations of 6 widely studied polymorphisms in PD-1 gene and cancer risk were included in this meta-analysis. There were 16 studies involving 5622 cases and 5450 controls that reported the association between PD-1 rs2227981 polymorphism and cancer. Eleven studies including 4766 cases and 5839 controls investigated the relationship between PD-1 rs2227982 polymorphism and cancer. Nine studies with 1846 cases and 1907 cases reported the association between PD-1 rs11568821 variant and cancer risk. Seven studies including 3576 cancer cases and 5277 controls studied the correlation between PD-1 rs7421861 polymorphism and cancer. Seven studies involving 3589 cases and 4314 controls examined the association between PD-1 rs36084323 polymorphism and cancer risk. Six studies including 3366 cancer cases and 4391 controls studied the relationship between PD-1 rs10204525 polymorphism and cancer.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection for this meta-analysis.

For PD-L1 polymorphisms, 13 case-control studies from 10 articles [27,38,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] that assessed the impact of two polymorphisms of PD-L1 were included in the pooled analysis. Eight studies including 3030 cases and 4145 controls evaluated the association between PD-L1 rs4143815 polymorphism and cancer risk. Five studies with 1909 cases and 1970 controls assessed the correlation between PD-L1 rs2890658 variant and cancer risk. The characteristics of all these studies are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies eligible for meta-analysis.

| First Author | Year | Country | Ethnicity | Cancer Type | Source of Control | Genotyping Method | Case/Control | Cases | Controls | HWE | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD-1 rs2227981 | CC | CT | TT | C | T | CC | CT | TT | C | T | ||||||||

| Fathi | 2019 | Iran | Asian | Squamous Cell Carcinomas of Head and Neck | HB | PCR-RFLP | 150/150 | 65 | 69 | 16 | 199 | 101 | 66 | 71 | 13 | 203 | 97 | 0.317 |

| Gomez | 2018 | Brazil | South American | Cutaneous Melanoma | PB | RT-PCR | 250/250 | 87 | 126 | 37 | 300 | 200 | 85 | 130 | 35 | 300 | 200 | 0.188 |

| Haghshenas | 2011 | Iran | Asian | Breast cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 435/328 | 194 | 191 | 50 | 579 | 291 | 137 | 145 | 46 | 419 | 237 | 0.446 |

| Haghshenas | 2017 | Iran | Asian | Thyroid cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 105/160 | 40 | 51 | 14 | 131 | 79 | 99 | 51 | 10 | 249 | 71 | 0.331 |

| Hua | 2011 | China | Asian | breast cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 486/478 | 295 | 169 | 22 | 759 | 213 | 244 | 210 | 24 | 698 | 258 | 0.012 |

| Ivansson | 2010 | Sweden | Caucasian | Cervical cancer | PB | TaqMan | 1300/810 | 471 | 603 | 226 | 1545 | 1055 | 257 | 375 | 178 | 889 | 731 | 0.064 |

| Li | 2016 | China | Asian | Cervical cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 256/250 | 45 | 167 | 44 | 257 | 255 | 62 | 101 | 87 | 225 | 275 | 0.004 |

| Li | 2017 | China | Asian | Ovarian cancer | HB | PCR-LDR | 620/620 | 351 | 233 | 36 | 935 | 305 | 319 | 250 | 51 | 888 | 352 | 0.837 |

| Ma | 2015 | China | Asian | lung cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 528/600 | 244 | 216 | 68 | 704 | 352 | 256 | 246 | 98 | 758 | 442 | 0.004 |

| Mojtahedi | 2012 | Iran | Asian | Colon cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 175/200 | 47 | 102 | 26 | 196 | 154 | 75 | 89 | 36 | 239 | 161 | 0.290 |

| Mojtahedi | 2012 | Iran | Asian | Rectal cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 25/200 | 12 | 7 | 6 | 31 | 19 | 75 | 89 | 36 | 239 | 161 | 0.290 |

| Namavar Jahromi | 2017 | Iran | Asian | Malignant Brain tumor | PB | PCR-RFLP | 56/150 | 22 | 31 | 3 | 75 | 37 | 94 | 47 | 9 | 235 | 65 | 0.346 |

| Pirdelkhosh | 2018 | Iran | Asian | NSCLC | PB | PCR-RFLP | 206/173 | 78 | 100 | 28 | 256 | 156 | 60 | 89 | 24 | 209 | 137 | 0.321 |

| Savabkar | 2013 | Iran | Asian | Gastric cancer | HB | PCR-RFLP | 122/166 | 50 | 66 | 6 | 166 | 78 | 89 | 70 | 7 | 248 | 84 | 0.136 |

| Yin | 2014 | China | Asian | Lung cancer | PB | PCR | 324/330 | 198 | 106 | 20 | 502 | 146 | 181 | 105 | 44 | 467 | 193 | 0.001 |

| Zhou | 2016 | China | Asian | ESCC | PB | PCR-LDR | 584/585 | 291 | 241 | 52 | 823 | 345 | 310 | 229 | 46 | 849 | 321 | 0.683 |

| PD-1 rs2227982 | CC | CT | TT | C | T | CC | CT | TT | C | T | ||||||||

| Fathi | 2019 | Iran | Asian | Squamous Cell Carcinomas of Head and Neck | HB | PCR-RFLP | 150/150 | 146 | 4 | 0 | 296 | 4 | 146 | 4 | 0 | 296 | 4 | 0.868 |

| Gomez | 2018 | Brazil | South American | Cutaneous Melanoma | PB | RT-PCR | 250/250 | 227 | 21 | 2 | 475 | 25 | 225 | 25 | 0 | 475 | 25 | 0.405 |

| Hua | 2011 | China | Asian | breast cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 487/506 | 111 | 249 | 127 | 471 | 503 | 95 | 268 | 143 | 458 | 554 | 0.121 |

| Ma | 2015 | China | Asian | lung cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 528/600 | 343 | 148 | 37 | 834 | 222 | 404 | 168 | 28 | 976 | 224 | 0.056 |

| Qiu | 2014 | China | Asian | esophageal cancer | HB | PCR-LDR | 616/681 | 159 | 303 | 154 | 621 | 611 | 189 | 325 | 167 | 703 | 659 | 0.245 |

| Ramzi | 2018 | Iran | Asian | Leukemia | PB | PCR-RFLP | 59/38 | 38 | 18 | 3 | 94 | 24 | 17 | 19 | 2 | 53 | 23 | 0.255 |

| Ren | 2016 | China | Asian | Breast Cancer | PB | MassARRAY | 557/582 | 172 | 257 | 128 | 601 | 513 | 137 | 299 | 146 | 573 | 591 | 0.503 |

| Tan | 2018 | China | Asian | Ovarian cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 164/170 | 87 | 60 | 17 | 234 | 94 | 111 | 48 | 11 | 270 | 70 | 0.075 |

| Tang | 2015 | China | Asian | Gastric cardia adenocarcinoma | HB | PCR-LDR | 330/603 | 75 | 168 | 87 | 318 | 342 | 163 | 292 | 148 | 618 | 588 | 0.448 |

| Tang | 2017 | China | Asian | Esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma | HB | SNPscan | 1041/1674 | 220 | 549 | 272 | 989 | 1093 | 416 | 816 | 442 | 1648 | 1700 | 0.309 |

| Zhou | 2016 | China | Asian | ESCC | PB | PCR-LDR | 584/585 | 149 | 305 | 130 | 603 | 565 | 150 | 297 | 138 | 597 | 573 | 0.702 |

| PD-1 rs7421861 | TT | TC | CC | T | C | TT | TC | CC | T | C | ||||||||

| Ge | 2015 | China | Asian | Colon cancer | HB | PCR-RFLP | 199/620 | 133 | 60 | 6 | 326 | 72 | 440 | 163 | 17 | 1043 | 197 | 0.685 |

| Ge | 2015 | China | Asian | Rectal cancer | HB | PCR-RFLP | 362/620 | 241 | 114 | 7 | 596 | 128 | 440 | 163 | 17 | 1043 | 197 | 0.685 |

| Hua | 2011 | China | Asian | Breast cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 490/512 | 333 | 146 | 11 | 812 | 168 | 370 | 130 | 12 | 870 | 154 | 0.885 |

| Qiu | 2014 | China | Asian | esophageal cancer | HB | PCR-LDR | 600/673 | 411 | 168 | 21 | 990 | 210 | 460 | 188 | 25 | 1108 | 238 | 0.295 |

| Ren | 2016 | China | Asian | Breast Cancer | PB | MassARRAY | 560/580 | 341 | 196 | 23 | 878 | 242 | 347 | 205 | 28 | 899 | 261 | 0.746 |

| Tang | 2015 | China | Asian | Gastric cardia adenocarcinoma | HB | PCR-LDR | 324/598 | 226 | 91 | 7 | 543 | 105 | 408 | 168 | 22 | 984 | 212 | 0.368 |

| Tang | 2017 | China | Asian | esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma | HB | SNPscan | 1041/1674 | 642 | 358 | 41 | 1642 | 440 | 1166 | 454 | 54 | 2786 | 562 | 0.232 |

| PD-1 rs11568821 | GG | AG | AA | G | A | GG | AG | AA | G | A | ||||||||

| Bayram | 2012 | Turkey | Asian | liver cancer | HB | PCR-RFLP | 236/236 | 191 | 45 | 0 | 427 | 45 | 180 | 56 | 0 | 416 | 56 | 0.039 |

| Fathi | 2019 | Iran | Asian | Squamous Cell Carcinomas of Head and Neck | HB | PCR-RFLP | 150/150 | 119 | 27 | 4 | 265 | 35 | 113 | 32 | 5 | 258 | 42 | 0.162 |

| Haghshenas | 2011 | Iran | Asian | Breast cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 436/290 | 365 | 63 | 8 | 793 | 79 | 231 | 55 | 4 | 517 | 63 | 0.726 |

| Haghshenas | 2017 | Iran | Asian | Thyroid cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 95/160 | 82 | 13 | 0 | 177 | 13 | 127 | 30 | 3 | 284 | 36 | 0.440 |

| Ma | 2015 | China | Asian | lung cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 528/600 | 426 | 102 | 0 | 954 | 102 | 456 | 142 | 2 | 1054 | 146 | 0.009 |

| Namavar Jahromi | 2017 | Iran | Asian | Malignant Brain tumor | PB | PCR-RFLP | 56/150 | 47 | 8 | 1 | 102 | 10 | 116 | 30 | 4 | 262 | 38 | 0.240 |

| Pirdelkhosh | 2018 | Iran | Asian | NSCLC | PB | PCR-RFLP | 206/173 | 171 | 31 | 4 | 373 | 39 | 144 | 26 | 3 | 314 | 32 | 0.168 |

| Ramzi | 2018 | Iran | Asian | Leukemia | PB | PCR-RFLP | 59/38 | 38 | 18 | 3 | 94 | 24 | 21 | 13 | 4 | 55 | 21 | 0.373 |

| Yousefi | 2013 | Asian | colon cancer | PB | 80/110 | 18 | 27 | 35 | 63 | 97 | 43 | 45 | 22 | 131 | 89 | 0.114 | ||

| PD-1 rs36084323 | GG | AG | AA | G | A | GG | AG | AA | G | A | ||||||||

| Gomez | 2018 | Brazil | South American | Cutaneous Melanoma | PB | RT-PCR | 250/250 | 226 | 18 | 6 | 470 | 30 | 225 | 25 | 0 | 475 | 25 | 0.405 |

| Hua | 2011 | China | Asian | Breast cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 490/512 | 103 | 271 | 116 | 477 | 503 | 140 | 260 | 112 | 540 | 484 | 0.673 |

| Li | 2017 | China | Asian | Ovarian cancer | HB | PCR-LDR | 620/620 | 150 | 301 | 169 | 601 | 639 | 168 | 323 | 129 | 659 | 581 | 0.251 |

| Ma | 2015 | China | Asian | lung cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 528/600 | 144 | 246 | 138 | 534 | 522 | 156 | 296 | 148 | 608 | 592 | 0.747 |

| Shamsdin | 2018 | Iran | Asian | Colon cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 76/73 | 60 | 15 | 1 | 135 | 17 | 18 | 28 | 27 | 64 | 82 | 0.059 |

| Tang | 2017 | China | Asian | esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma | HB | SNPscan | 1041/1674 | 238 | 521 | 282 | 997 | 1085 | 430 | 800 | 444 | 1660 | 1688 | 0.071 |

| Zhou | 2016 | China | Asian | ESCC | PB | PCR-LDR | 584/585 | 147 | 303 | 134 | 597 | 571 | 145 | 298 | 142 | 588 | 582 | 0.649 |

| PD-1 rs10204525 | AA | AG | GG | A | G | AA | AG | GG | A | G | ||||||||

| Li | 2013 | China | Asian | HCC | PB | TIANamp | 271/318 | 180 | 83 | 8 | 443 | 99 | 160 | 130 | 28 | 450 | 186 | 0.828 |

| Qiu | 2014 | China | Asian | esophageal cancer | HB | PCR-LDR | 600/651 | 317 | 240 | 43 | 874 | 326 | 345 | 243 | 63 | 933 | 369 | 0.039 |

| Ren | 2016 | China | Asian | Breast Cancer | PB | MassARRAY | 559/582 | 257 | 248 | 54 | 762 | 356 | 291 | 240 | 51 | 822 | 342 | 0.880 |

| Tang | 2015 | China | Asian | Gastric cardia adenocarcinoma | HB | PCR-LDR | 313/581 | 169 | 123 | 21 | 461 | 165 | 309 | 219 | 53 | 837 | 325 | 0.120 |

| Tang | 2017 | China | Asian | esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma | HB | SNPscan | 1039/1674 | 544 | 397 | 98 | 1485 | 593 | 870 | 672 | 132 | 2412 | 936 | 0.888 |

| Zhou | 2016 | China | Asian | ESCC | PB | PCR-LDR | 584/585 | 325 | 226 | 33 | 876 | 292 | 296 | 238 | 51 | 830 | 340 | 0.749 |

| PD-L1 rs4143815 | GG | CG | CC | G | C | GG | CG | CC | G | C | ||||||||

| Catalano | 2018 | Czech | Caucasian | Colon cancer | HB | TaqMan | 824/1103 | 388 | 345 | 91 | 1121 | 527 | 514 | 467 | 122 | 1495 | 711 | 0.306 |

| Catalano | 2018 | Czech | Caucasian | Rectal cancer | HB | TaqMan | 371/1103 | 167 | 162 | 42 | 496 | 246 | 514 | 467 | 122 | 1495 | 711 | 0.306 |

| Du | 2017 | China | Asian | NSCLC | HB | sequencing | 320/199 | 52 | 145 | 123 | 249 | 391 | 40 | 80 | 79 | 160 | 238 | 0.021 |

| Tan | 2018 | China | Asian | Ovarian cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 164/170 | 51 | 82 | 31 | 184 | 144 | 38 | 78 | 54 | 154 | 186 | 0.334 |

| Tao | 2017 | China | Asian | Gastric cancer | HB | Sequencing | 346/500 | 123 | 153 | 70 | 399 | 293 | 117 | 223 | 160 | 457 | 543 | 0.023 |

| Wang | 2013 | China | Asian | Gastric cancer | HB | sequencing | 205/393 | 88 | 72 | 45 | 248 | 162 | 70 | 188 | 135 | 328 | 458 | 0.746 |

| Xie | 2018 | China | Asian | HCC | HB | sequencing | 225/200 | 74 | 101 | 50 | 249 | 201 | 31 | 104 | 65 | 166 | 234 | 0.316 |

| Zhou | 2017 | China | Asian | ESCC | PB | PCR-LDR | 575/577 | 87 | 277 | 211 | 451 | 699 | 85 | 289 | 203 | 459 | 695 | 0.275 |

| PD-L1 rs2890658 | AA | AC | CC | A | C | AA | AC | CC | A | C | ||||||||

| Chen | 2014 | China | Asian | NSCLC | HB | PCR-RFLP | 293/293 | 242 | 48 | 3 | 532 | 54 | 266 | 26 | 1 | 558 | 28 | 0.671 |

| Cheng | 2015 | China | Asian | NSCLC | HB | PCR-RFLP | 288/300 | 233 | 51 | 4 | 517 | 59 | 269 | 30 | 1 | 568 | 32 | 0.867 |

| Ma | 2015 | China | Asian | lung cancer | PB | PCR-RFLP | 528/600 | 416 | 106 | 6 | 938 | 118 | 512 | 84 | 4 | 1108 | 92 | 0.785 |

| Xie | 2018 | China | Asian | HCC | HB | sequencing | 225/200 | 170 | 49 | 6 | 389 | 61 | 139 | 55 | 6 | 333 | 67 | 0.844 |

| Zhou | 2017 | China | Asian | ESCC | PB | PCR-LDR | 575/577 | 18 | 161 | 396 | 197 | 953 | 15 | 144 | 418 | 174 | 980 | 0.541 |

List of Abbreviations: HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; PB: Population-based; HB: Hospital-based; ESCC: Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; LDR: Ligase Detection Reaction; NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer; PCR-RFLP: PCR-Restriction fragment length polymorphism; HWE: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; MassARRAY®System: Nonfluorescent detection platform utilizing mass spectrometry to accurately measure PCR-derived amplicons.

2.2. Main Analysis Results

2.2.1. Association of PD-1 Polymorphisms with Cancer Risk

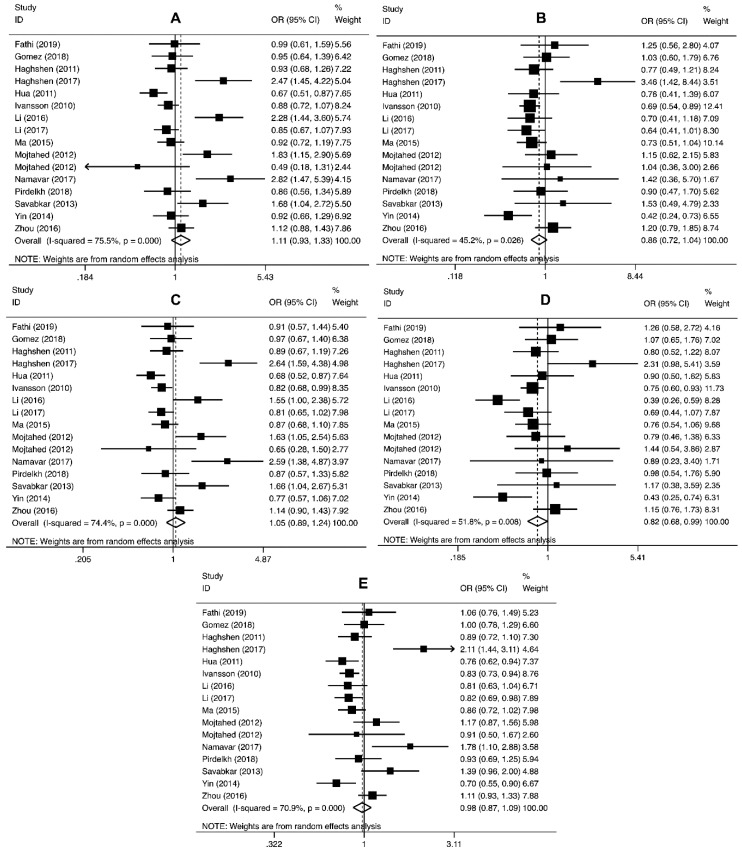

The pooled analysis involving PD-1 rs2227981 polymorphism revealed that this variant significantly decreased the overall cancer risk in recessive (OR = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.68–0.99, p = 0.04, TT vs. CT+CC) genetic models (Table 3 and Figure 2).

Table 3.

The pooled ORs and 95% CIs for the association between PD-1 and PD-L1 polymorphisms and cancer susceptibility.

| Polymorphism | n | Genetic Model | Association Test | Heterogeneity Test | Publication Bias Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | Z | p | χ2 | I2 (%) | p | Egger’s Test p | Begg’s Test p | |||

| PD-1 rs2227981 | 16 | CT vs. CC | 1.11 (0.93–1.33) | 1.16 | 0.25 | 61.22 | 75 | <0.00001 | 0.032 | 0.031 |

| TT vs. CC | 0.86 (0.72–1.04) | 1.51 | 0.13 | 27.39 | 45 | 0.03 | 0.034 | 0.024 | ||

| CT+TT vs. CC | 1.05 (0.89–1.24) | 0.64 | 0.52 | 58.58 | 74 | <0.00001 | 0.019 | 0.005 | ||

| TT vs. CT+CC | 0.82 (0.68–0.99) | 2.04 | 0.04 | 31.12 | 52 | 0.008 | 0.155 | 0.150 | ||

| T vs. C | 0.98 (0.87–1.09) | 0.43 | 0.66 | 51.48 | 71 | <0.00001 | 0.020 | 0.012 | ||

| PD-1 rs2227982 | 11 | CT vs. CC | 1.01 (0.85–1.19) | 0.09 | 0.930 | 24.53 | 59 | 0.006 | 0.359 | 0.186 |

| TT vs. CC | 1.05 (0.87–1.26) | 0.51 | 0.611 | 17.10 | 47 | 0.050 | 0.288 | 0.180 | ||

| CT+TT vs. CC | 1.02 (0.86–1.20) | 0.22 | 0.829 | 26.49 | 62 | 0.003 | 0.469 | 0.484 | ||

| TT vs. CT+CC | 1.00 (0.90–1.10) | 0.04 | 0.97 | 7.52 | 0 | 0.581 | 0.184 | 0.211 | ||

| T vs. C | 1.02 (0.92–1.12) | 0.38 | 0.707 | 20.50 | 51 | 0.025 | 0.927 | 0.715 | ||

| PD-1 rs11568821 | 9 | AG vs. GG | 0.79 (0.67–0.94) | 2.73 | 0.006 | 3.89 | 0 | 0.87 | 0.499 | 0.409 |

| AA vs. GG | 1.01 (0.47–2.14) | 0.01 | 0.99 | 13.19 | 47 | 0.07 | 0.015 | 0.091 | ||

| AG+AA vs. GG | 0.82 (0.70–0.96) | 2.42 | 0.020 | 11.30 | 29 | 0.19 | 0.613 | 0.835 | ||

| AA vs. AG+GG | 1.07 (0.54–2.13) | 0.19 | 0.846 | 11.79 | 41 | 0.11 | 0.010 | 0.095 | ||

| A vs. G | 0.88 (0.68–1.15) | 0.92 | 0.36 | 24.39 | 67 | 0.002 | 0.822 | 0.835 | ||

| PD-1 rs7421861 | 7 | CT vs. TT | 1.16 (1.02–1.33) | 2.20 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 46 | 0.09 | 0.215 | 0.881 |

| CC vs. TT | 1.00 (0.79–1.28) | 0.03 | 0.98 | 4.76 | 0 | 0.57 | 0.116 | 0.881 | ||

| CT+CC vs. TT | 1.14 (0.99–1.31) | 1.81 | 0.07 | 12.93 | 54 | 0.04 | 0.196 | 0.453 | ||

| CC vs. CT+TT | 0.96 (0.75–1.22) | 0.37 | 0.71 | 3.49 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.101 | 0.652 | ||

| C vs. T | 1.09 (0.97–1.23) | 1.42 | 0.16 | 13.02 | 54 | 0.04 | 0.200 | 0.652 | ||

| PD-1 rs36084323 | 7 | AG vs. GG | 0.92 (0.71–1.20) | 0.60 | 0.55 | 27.83 | 78 | 0.0001 | 0.042 | 0.051 |

| AA vs. GG | 1.08 (0.77–1.52) | 0.45 | 0.66 | 28.21 | 79 | 0.0001 | 0.079 | 0.188 | ||

| AG+AA vs. GG | 0.88 (0.64–1.21) | 0.79 | 0.43 | 47.46 | 87 | <0.00001 | 0.081 | 0.293 | ||

| AA vs. AG+GG | 1.06 (0.83–1.36) | 0.46 | 0.64 | 22.86 | 74 | 0.0008 | 0.137 | 0.348 | ||

| A vs. G | 0.89 (0.70–1.14) | 0.92 | 0.36 | 66.01 | 91 | <0.00001 | 0.160 | 0.453 | ||

| PD-1 rs10204525 | 6 | AG vs. AA | 0.94 (0.80–1.10) | 0.76 | 0.45 | 13.13 | 62 | 0.02 | 0.640 | 0.851 |

| GG vs. AA | 0.76 (0.53–1.09) | 1.48 | 0.14 | 19.40 | 74 | 0.002 | 0.031 | 0.091 | ||

| AG+GG vs. AA | 0.90 (0.75–1.08) | 1.10 | 0.27 | 18.41 | 73 | 0.002 | 0.399 | 0.188 | ||

| GG vs. AG+AA | 0.78 (0.57–1.09) | 1.46 | 0.14 | 16.64 | 70 | 0.005 | 0.020 | 0.039 | ||

| G vs. A | 0.89 (0.76–1.05) | 1.38 | 0.17 | 23.71 | 79 | 0.0002 | 0.172 | 0.091 | ||

| PD-L1 rs4143815 | 8 | CG vs. GG | 0.75 (0.55–1.01) | 1.89 | 0.06 | 43.76 | 84 | <0.0001 | 0.230 | 0.322 |

| CC vs. GG | 0.62 (0.41–0.94) | 2.28 | 0.02 | 52.19 | 87 | <0.00001 | 0.188 | 0.138 | ||

| CG+CC vs. GG | 0.70 (0.50–0.97) | 2.15 | 0.03 | 43.20 | 84 | <0.00001 | 0.184 | 0.138 | ||

| CC vs. CG+GG | 0.76 (0.60–0.96) | 2.30 | 0.02 | 25.19 | 72 | 0.0007 | 0.070 | 0.138 | ||

| C vs. G | 0.78 (0.63–0.96) | 2.33 | 0.02 | 61.68 | 89 | <0.00001 | 0.100 | 0.138 | ||

| PD-L1 rs2890658 | 5 | AC vs. AA | 1.36 (0.92–2.01) | 1.53 | 0.13 | 13.83 | 71 | 0.008 | 0.757 | 0.624 |

| CC vs. AA | 1.12 (0.68–1.84) | 0.45 | 0.65 | 4.31 | 7 | 0.37 | 0.032 | 0.050 | ||

| AC+CC vs. AA | 1.35 (0.89–2.04) | 1.43 | 0.15 | 16.24 | 75 | 0.003 | 0.736 | 1.000 | ||

| CC vs. AC+AA | 0.90 (0.71–1.15) | 0.83 | 0.41 | 4.25 | 6 | 0.37 | 0.041 | 0.050 | ||

| C vs. A | 1.30 (0.88–1.91) | 1.32 | 0.19 | 25.96 | 85 | <0.0001 | 0.248 | 0.142 | ||

Figure 2.

Forest plot for the association between PD-1 rs2227981 polymorphism and cancer susceptibility for CT vs. CC (A), TT vs. CC (B), CT+TT vs. CC (C), TT vs. CT+TT (D), and T vs. C (E).

In regard to PD-1 rs11568821 polymorphism, the findings indicated that this variant significantly decreased the overall cancer risk in heterozygous (OR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.67–0.94, p = 0.006, AG vs. GG) and dominant (OR = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.70–0.96, p = 0.020, AG+AA vs. GG) genetic models (Table 3).

The pooled analysis proposed that PD-1 rs7421861 polymorphism significantly increased the risk of overall cancer in heterozygous (OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.02–1.33, p = 0.03, CT vs. TT) genetic models (Table 3).

No significant association was found between PD-1 rs2227982, rs36084323, and rs10204525 polymorphisms and cancer susceptibility (Table 3).

We performed stratified analyses and the findings are summarized in Table 4. We observed that PD-1 rs2227981 significantly decreased the risk of gastrointestinal (GI) cancer (OR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.56–0.84, p = 0.000, TT vs. CC; OR = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.40–0.89, p = 0.011, TT vs. CT+CC; OR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.75–0.91, p = 0.000, T vs. C), lung cancer (OR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.44–0.97, p = 0.030, TT vs. CC; OR = 0.84, 95% CI = 0.71–0.99, p = 0.043, CT+TT vs. CC; OR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.72–0.95, p = 0.009, T vs. C), and breast cancer (OR = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.70–0.06, p = 0.012, T vs. C).

Table 4.

Stratified analysis of PD-1 and PD-L1 polymorphisms with cancer susceptibility.

| Variable | No. | CT vs. CC | TT vs. CC | CT+TT vs. CC | TT vs. CT+CC | T vs. C | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD-1 rs2227981 | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Asian | 14 | 1.16 (0.94–1.43) | 0.173 | 0.89 (0.71–1.12) | 0.312 | 1.09 (0.90–1.32) | 0.393 | 0.83 (0.66–1.04) | 0.106 | 1.00 (0.87–1.14) | 0.953 |

| Population-based | 13 | 1.12 (0.91–1.39) | 0.276 | 0.88 (0.70–1.07) | 0.175 | 1.06 (0.87–1.28) | 0.571 | 0.81 (0.66–1.01) | 0.060 | 0.97 (0.85–1.10) | 0.611 |

| Hospital-based | 3 | 1.06 (0.72–1.61) | 0.714 | 0.91 (0.53–1.59) | 0.749 | 1.04 (0.68–1.57) | 0.873 | 0.85 (0.57–1.26) | 0.421 | 1.03 (0.76–1.41) | 0.839 |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 3 | 1.13 (0.73–1.76) | 0.588 | 0.68 (0.56–0.84) | 0.000 | 0.95 (0.71–1.27) | 0.713 | 0.60 (0.40–0.89) | 0.011 | 0.83 (0.75–0.91) | 0.000 |

| Lung cancer | 3 | 0.91 (0.76–1.10) | 0.324 | 0.65 (0.44–0.97) | 0.030 | 0.84 (0.71–0.99) | 0.043 | 0.69 (0.45–1.04) | 0.079 | 0.83 (0.72–0.95) | 0.009 |

| Breast cancer | 2 | 0.78 (0.56–1.08) | 0.136 | 0.76 (0.53–1.10) | 0.147 | 0.80 (0.59–1.01) | 0.058 | 0.83 (0.59–1.17) | 0.291 | 0.82 (0.70–0.96) | 0.012 |

| PD-1 rs2227982 | CT vs. CC | TT vs. CC | CT+TT vs. CC | TT vs. CT+CC | T vs. C | ||||||

| Asian | 10 | 1.02 (0.85–1.21) | 0.845 | 1.04 (0.87–1.26) | 0.655 | 1.02 (0.86–1.22) | 0.790 | 1.00 (0.90–1.10) | 0.921 | 1.02 (0.92–1.12) | 0.708 |

| Population-based | 8 | 0.91 (0.73–1.12) | 0.363 | 0.99 (0.73–1.33) | 0.934 | 0.93 (0.741.16) | 0.507 | 0.99 (0.83–1.17) | 0.734 | 0.98 (0.85–1.14) | 0.818 |

| Hospital-based | 3 | 1.22 (1.06–1.40) | 0.006 | 1.16 (0.99–1.37) | 0.067 | 1.20 (1.05–1.37) | 0.008 | 1.02 (0.89–1.16) | 0.806 | 1.08 (0.99–1.17) | 0.077 |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 4 | 1.18 (1.04–1.34) | 0.011 | 1.12 (0.97–1.29) | 0.133 | 1.16 (1.03–1.30) | 0.017 | 1.00 (0.89–1.12) | 0.989 | 1.06 (0.98–1.34) | 0.146 |

| Breast cancer | 2 | 0.73 (0.59–0.90) | 0.004 | 0.73 (0.57–0.93) | 0.010 | 0.73 (0.60–0.89) | 0.002 | 0.89 (0.74–1.09) | 0.257 | 0.85 (0.76–0.96) | 0.010 |

| PD-1 rs7421861 | CT vs. TT | CC vs. TT | CT+CC vs. TT | CC vs. CT+TT | C vs. T | ||||||

| Hospital-based | 5 | 1.89 (1.01–1.40) | 0.042 | 1.05 (0.79–1.39) | 0.745 | 1.16 (0.98–1.38) | 0.096 | 0.99 (0.74–1.31) | 0.916 | 1.11 (0.95–1.29) | 0.192 |

| Population-based | 2 | 1.09 (0.86–1.39) | 0.478 | 0.89 (0.56–1.43) | 0.630 | 1.07 (0.84–1.37) | 0.565 | 0.88 (0.55–1.40) | 0.586 | 1.04 (0.85–1.28) | 0.692 |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 5 | 1.19 (1.01–1.40) | 0.042 | 1.05 (0.79–1.39) | 0.745 | 1.16 (0.97–1.38) | 0.096 | 1.00 (0.75–1.32) | 0.979 | 1.11 (0.95–1.29) | 0.192 |

| Breast cancer | 2 | 1.09 (0.86–1.39) | 0.478 | 0.89 (0.56–1.43) | 0.630 | 1.07 (0.84–1.37) | 0.565 | 0.88 (0.55–1.40) | 0.586 | 1.04 (0.85 (1.28) | 0.692 |

| PD-1 rs11568821 | AG vs. GG | AA vs. GG | AG+AA vs. GG | AA vs. AG+GG | A vs. G | ||||||

| Population-based | 7 | 0.80 (0.66–0.97) | 0.020 | 1.02 (0.43–2.42) | 0.968 | 0.86 (0.65–1.14) | 0.288 | 1.09 (0.50–2.38) | 0.833 | 0.92 (0.78–1.08) | 0.294 |

| Hospital-based | 2 | 0.77 (0.55–1.10) | 0.150 | 0.76 (0.20–2.90) | 0.688 | 0.77 (0.55–1.09) | 0.140 | 0.76 (0.21–3.02) | 0.736 | 0.80 (0.58–1.09) | 0.152 |

| PD-1 rs36084323 | AG vs. GG | AA vs. GG | AG+AA vs. GG | AA vs. AG+GG | A vs. G | ||||||

| Asian | 6 | 0.95 (0.71–1.25) | 0.691 | 1.05 (0.75–1.47) | 0.769 | 0.86 (0.61–1.23) | 0.412 | 1.05 (0.82–1.33) | 0.715 | 0.86 (0.67–1.12) | 0.259 |

| Population-based | 5 | 0.78 (0.50–1.21) | 0.268 | 0.88 (0.47–1.63) | 0.674 | 0.71 (0.42–1.22) | 0.219 | 0.94 (0.61–1.45) | 0.767 | 0.74 (0.49–1.12) | 0.152 |

| Hospital–based | 2 | 1.13 (0.97–1.32) | 0.127 | 1.26 (1.00–1.59) | 0.052 | 1.17 (1.01–1.35) | 0.042 | 1.93 (0.87–1.64) | 0.277 | 1.12 (1.00–1.26) | 0.05 |

| PD-1 rs10204525 | AG vs. AA | GG vs. AA | AG+GG vs. AA | GG vs. AG+AA | G vs. A | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 5 | 0.90 (0.76–1.07) | 0.227 | 0.63 (0.45–1.04) | 0.078 | 0.86 (0.70–1.04) | 0.121 | 0.72 (0.48–1.06) | 0.096 | 0.85 (0.71–1.02) | 0.077 |

| Population-based | 3 | 0.85 (0.58–1.23) | 0.382 | 0.60 (0.28–1.32) | 0.203 | 0.80 (0.52–1.32) | 0.312 | 0.65 (0.35–1.23) | 0.186 | 0.80 (0.55–1.17) | 0.246 |

| Hospital-based | 3 | 0.99 (0.88–1.22) | 0.908 | 0.90 (0.63–1.29) | 0.568 | 0.99 (0.88–1.11) | 0.831 | 0.89 (0.60–1.32) | 0.560 | 0.99 (0.90–1.08) | 0.767 |

| PD-L1 rs4143815 | CG vs. GG | CC vs. GG | CG+CC vs. GG | CC vs. CG+GG | C vs. G | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 6 | 0.68 (0.48–0.97) | 0.032 | 0.59 (0.37–0.96) | 0.033 | 0.64 (0.43–0.95) | 0.028 | 0.77 (0.58–1.02) | 0.064 | 0.76 (0.59–0.98) | 0.034 |

| Hospital-based | 6 | 0.71 (0.48–1.05) | 0.087 | 0.60 (0.36–1.00) | 0.051 | 0.67 (0.44–1.02) | 0.059 | 0.75 (0.58–0.97) | 0.030 | 0.76 (0.58–0.99) | 0.043 |

| Population-based | 2 | 0.89 (0.68–1.18) | 0.414 | 0.68 (0.29–1.59) | 0.378 | 0.82 (0.55–1.23) | 0.332 | 0.76 (0.36–1.59) | 0.460 | 0.83 (0.53–1.30) | 0.413 |

| PD-L1 rs2890658 | AC vs. AA | CC vs. AA | AC+CC vs. AA | CC vs. AC+AA | C vs. A | ||||||

| Lung cancer | 3 | 1.74 (1.37–2.19) | 0.000 | 2.48 (0.92–6.69) | 0.072 | 1.77 (1.41–2.23) | 0.000 | 2.29 (0.85–6.16) | 0.101 | 1.72 (1.39–2.13) | 0.000 |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 2 | 4.34 (0.13–148.07) | 0.415 | 4.43 (0.17–112.70) | 0.368 | 0.76 (0.53–1.10) | 0.141 | 0.84 (0.66–1.08) | 0.179 | 0.84 (0.69–1.01) | 0.070 |

| Hospital-based | 3 | 1.42 (0.72–2.96) | 0.317 | 1.61 (0.52–4.98) | 0.409 | 1.45 (0.72–2.92) | 0.296 | 1.45 (0.57–3.73) | 0.439 | 1.46 (0.75–2.82) | 0.266 |

| Population-based | 2 | 6.30 (0.39–103.18) | 0.197 | 6.85 (0.60–78.36) | 0.122 | 1.23 (0.67–2.26) | 0.503 | 0.90 (0.56–1.37) | 0.636 | 1.13 (0.65–1.97) | 0.661 |

Furthermore, we found that the PD-1 rs2227982 was associated with an increased risk of cancer in hospital based studies (OR = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.06–1.40, p = 0.006, CT vs. CC; OR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.05–1.37, p = 0.008, CT+TT vs. CC). We also found a negative correlation between the PD-1 rs2227982 polymorphism and the risk of gastrointestinal cancer (OR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.04–1.34, p = 0.011, CT vs. CC; OR = 1.16 (95% CI = 1.03–1.30, p = 0.017, CT+TT vs. CC) and breast cancer risk (OR = 0.73, 95% CI = 0.59–0.90, p = 0.004, CT vs. CC; OR = 0.73, 95% CI = 0.57–0.93, p = 0.010, TT vs. CC; OR = 73, 95% CI = 0.60–0.89, p = 0.002, CT+TT vs. CC; OR = 0.85, 95% CI = 76–0.96, p = 0.010, T vs. C). With reference to the PD-1 rs7421861, our finding proposed that this variant significantly increased the risk of cancer in hospital based studies (OR = 1.89, 95% CI = 1.01–1.40, p = 0.042, CT vs. TT) as well as gastrointestinal cancer (OR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.01–1.40, p = 0.042, CT vs. CC). Moreover, a significantly reduce cancer risk in population-based studies (OR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.66–0.97, p = 0.020, AG vs. GG) was observed regarding PD-1 rs11568821 variant. The PD-1 rs36084323 variant was however associated with an increased risk of cancer in hospital-based studies (OR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.01–1.35, p = 0.042, AG+AA vs. GG).

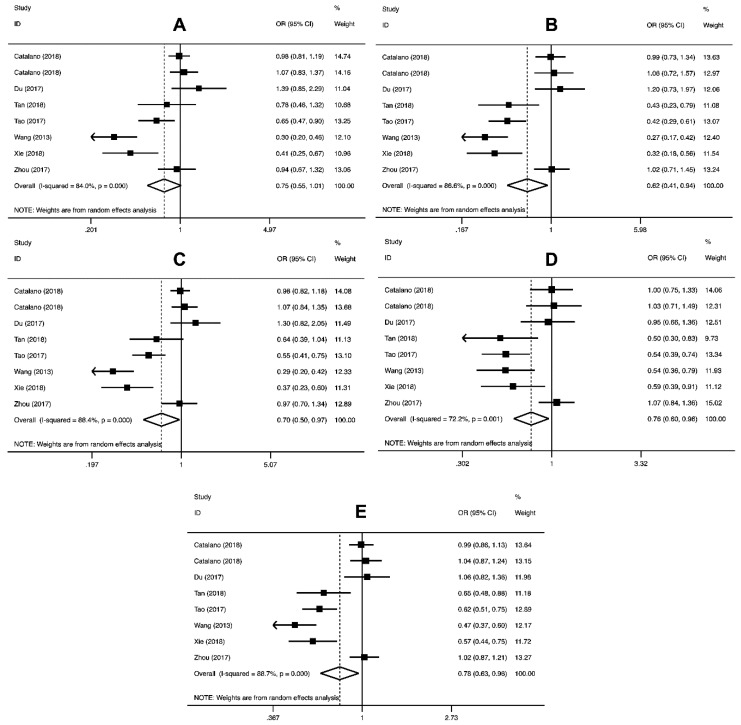

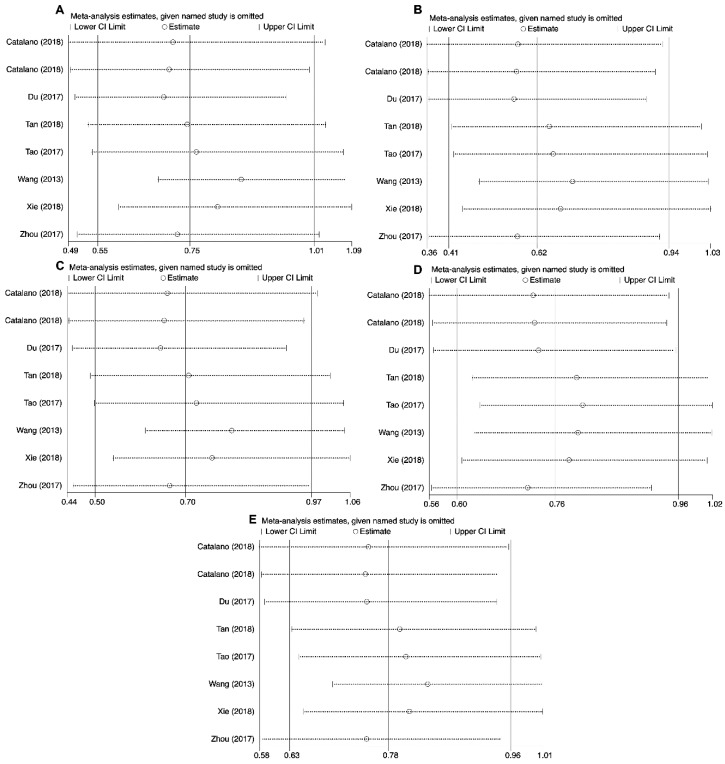

2.2.2. PD-L1 Polymorphisms and Cancer Risk

The pooled ORs results for the relationship between the PD-L1 rs4143815 and rs2890658 polymorphisms and the risk of cancer are shown in Table 3. The PD-L1 rs4143815 variant significantly decreased the risk of cancer in homozygous (OR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.41–0.94, p = 0.02), dominant (OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.50–0.97, p = 0.03), recessive (OR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.60–0.96, p = 0.02), and allele (OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.63–0.96, p = 0.02) genetic models (Table 3 and Figure 3). The pooled analysis did not support an association between PD-L1 rs2890658 polymorphism and risk of cancer susceptibility (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the relationship between PD-L1 rs4143815 polymorphism and cancer susceptibility for CG vs. GG (A), CC vs. GG (B), CG+CC vs. GG (C), CC vs. CG+GG (D), and C vs. G (E).

We did stratified analysis (Table 4) and the findings revealed that PD-L1 rs4143815 polymorphism significantly reduced the risk of gastrointestinal cancer (OR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.48–0.97, p = 0.032, CC vs. GG; OR = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.37–0.96, p = 0.033, CC vs. GG; OR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.43–0.95, p = 0.028, CG+CC vs. GG; OR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.59–0.98, p = 0.034, C vs. G) and hospital-based studies (OR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.58–0.97, p = 0.030, CC vs. CG+GG; OR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.58–0.99, p = 0.043, C vs. G). In regard to PD-L1 rs2890658, a positive correlation between this variant and the risk of lung cancer (OR = 1.74, 95% CI = 1.37–2.19, p = 0.000, AC vs. AA; OR = 1.77, 95% CI = 1.41–2.23, p = 0.000, AC+CC vs. AA; OR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.39–2.13, p = 0.000 C vs. A) was observed (Table 4).

2.3. Heterogeneity

As shown in Table 3, heterogeneity between the studies regarding the PD-1 rs2227981, PD-1 rs36084323, PD-1 rs10204525, and PD-L1 rs4143815 was observed in all genetic models. For PD-1 rs2227982 polymorphism, our results showed no evidence of heterogeneity in the recessive model (TT vs. CT+CC). Regarding PD-1 rs11568821, heterogeneity was not observed in the heterozygous, homozygous, dominant, and recessive genetic models. Similarly, no evidence of heterogeneity in the heterozygous, homozygous, and recessive genetic models of PD-1 rs7421861 was found. Heterogeneity was not detected in the homozygous and recessive genetic models of the PD-L1 rs2890658.

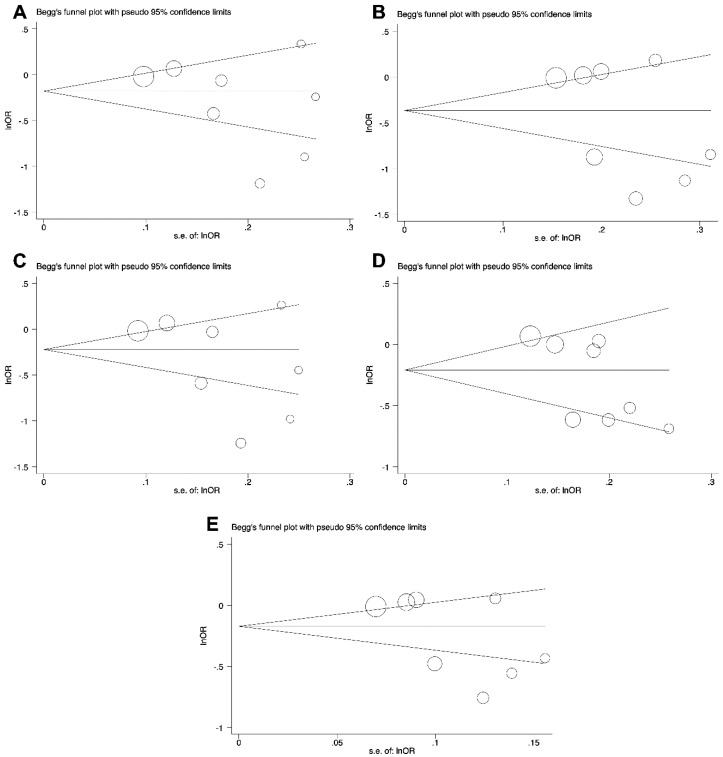

2.4. Publication Bias

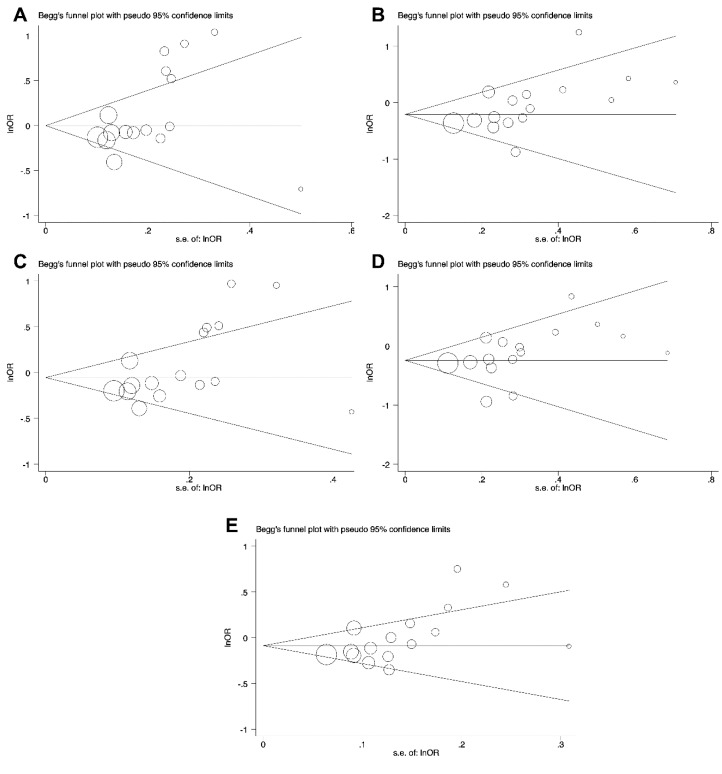

The potential publication bias of the studies included in the present meta-analysis was examined by Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test. The results of publication bias are summarized in Table 3. Based on the above analysis, no publication bias for the association of PD-1 rs2227982, PD-1 rs7421861, and PD-L1 rs4143815 variants in all genetic models and cancer risk was demonstrated (Table 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The funnel plot of PD-L1 rs4143815 for the test of publication bias for CG vs. GG (A), CC vs. GG (B), CG+CC vs. GG (C), CC vs. CG+GG (D), and C vs. G (E).

As presented in Table 3 and Figure 5, no publication bias was observed in recessive genetic model of PD-1 rs2227981. Obvious publication bias was not found in the heterozygous, dominant, and allele genetic models of the PD-1 rs11568821 and PD-L1 rs2890658 (Table 3). Moreover, the publication bias was not observed in heterozygous, dominant, recessive, and allele genetic models of the PD-1 rs36084323 and PD-1 rs10204525. (Table 3).

Figure 5.

The funnel plot of PD-1 rs2227981 polymorphism for the test of publication bias for CT vs. CC (A), TT vs. CC (B), CT+TT vs. CC (C), TT vs. CT+TT (D), and T vs. C (E).

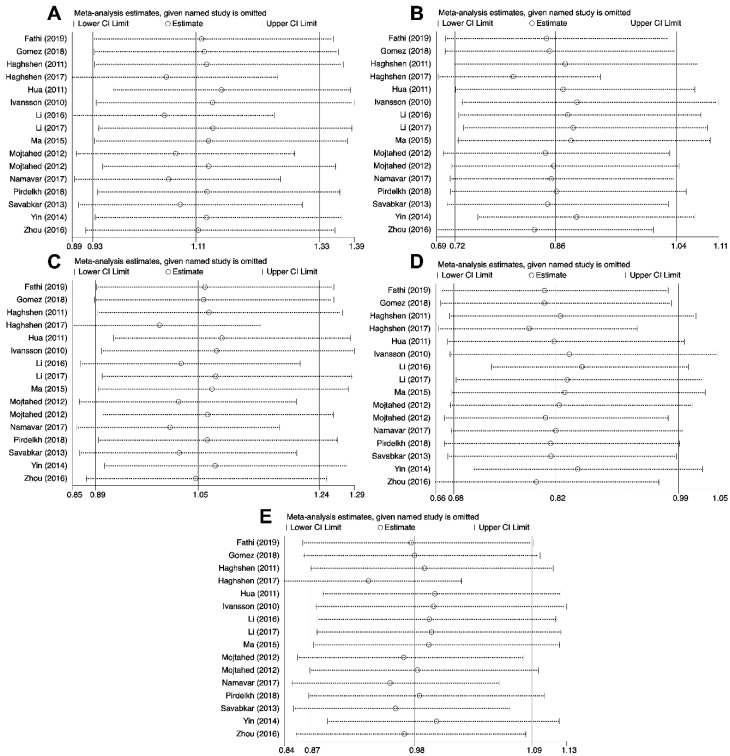

2.5. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted by replicating analysis after neglecting one study at a time to estimate the effect of quality of studies on the final findings. Taken together, our findings from the meta-analysis of the correlation between analyzed polymorphisms and cancer susceptibility remained unchanged in the heterozygous (PD-1 rs2227982, PD-1 rs36084323 and PD-1 rs10204525), homozygous (PD-1 rs2227982, PD-1 rs7421861, PD-1 rs36084323, PD-1 rs10204525 and PD-L1 rs2890658), dominant (PD-1 rs36084323 and PD-1 rs10204525), recessive (PD-1 rs2227982, PD-1 rs7421861, PD-1 rs36084323 and PD-L1 rs2890658), and allele (PD-1 rs2227982, PD-1 rs7421861 PD-1 rs10204525 and PD-L1 rs2890658) genetic models (Figure 6). In regard to PD-L1 rs4143815, the findings changed in the heterozygous, homozygous, dominant, recessive, and allele genetics models (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analyses for studies on PD-1 rs2227981 polymorphism and cancer susceptibility for CG vs. GG (A), CC vs. GG (B), CG+CC vs. GG (C), CC vs. CG+GG (D), and C vs. G (E).

Figure 7.

Sensitivity analyses for studies on PD-L1 rs4143815 polymorphism and cancer susceptibility for CG vs. GG (A), CC vs. GG (B), CG+CC vs. GG (C), CC vs. CG+GG (D), and C vs. G (E).

3. Discussion

It has been proposed that environmental and genetic factors contribute to cancer development [53,54]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) can be considered as biological markers that help scientists to recognize genes that are related to cancer [55].

PD-1 and PD-L1 are involved in the regulation of programmed cell death, which is the regulator of cancer cell proliferation as well as primary response in many cancer therapy strategies. Several studies have investigated the association between PD-1 as well as PD-L1 polymorphisms and the risk of various types of cancers; however, the findings remain discrepant. This meta-analysis provides, for the first time a quantitative estimated of the association between six SNPs of PD-1 and two SNPs of PD-L1 gene and cancer susceptibility. The findings indicated that PD-1 rs2227981 and rs11568821 polymorphisms as well as PDL-1 rs4143815 variant significantly decreased the overall cancer risk, while PD-1 rs7421861 polymorphism significantly increased the risk of overall cancer. Our findings revealed no significant association between PD-1 rs2227982, PD-1 rs36084323, PD-1 rs10204525, and PD-L1 rs2890658 polymorphisms and overall cancer risk.

We performed stratified analyses and our findings indicate that PD-1 rs2227981 significantly decreased the risk of gastrointestinal cancer, lung cancer and breast cancer. The PD-1 rs2227982 was associated with increased risk of cancer in hospital-based studies and lower risk of gastrointestinal and breast cancer. Similarly to PD-1 rs7421861, the PD-1 rs7421861 and PD-1 rs36084323 variants significantly increased the risk of cancer in hospital-based studies. The PD-1 rs11568821 was linked to reduce risk of cancer in population-based studies. Moreover, our findings revealed that PD-L1 rs4143815 polymorphism significantly reduced the risk of gastrointestinal cancer and hospital-based studies. A positive correlation between PD-L1 rs2890658 variant and the risk of lung cancer was observed.

Recently, Zou et al. [56] performed a meta-analysis of the association between PD-L1 rs4143815 polymorphism and the risk of cancer and found also a significant association between this variant and cancer risk, which is in line with our findings. Like our results, a meta-analysis conducted by Da et al. [57] revealed no significant association between PD-1 rs36084323 polymorphism and overall cancer susceptibility. Similar to previous meta-analysis conducted by Zhang et al. [58], we have also found that PD-1 rs2227981 and rs11568821 polymorphisms were associated with decreased cancer susceptibility. In another study, Dong et al. [59] conducted a meta-analysis aimed to inspect the associations between PD-1 rs2227981, rs2227982, rs7421861, and rs11568821 polymorphisms and cancer risk. There were seven studies involving 3395 cases and 2912 controls for PD-1 rs2227981, four studies including 1961 cases and 2390 controls for PD-1 rs2227982, four studies with 1975 cases and 2403 controls for PD-1 rs7421861, and four studies for PD-1 rs11568821 variant and cancer risk. They have found that rs2227981 and rs11568821 polymorphisms significantly decreased the risk of cancer. Mamat et al. [60] conducted a meta-analysis of six studies involving 1427 cases and 1811 controls and have observed no significant association between PD-1 rs2227981 polymorphism and the risk of cancer.

Nevertheless, the number of cases and controls as well as the number of polymorphisms in our meta-analysis is higher than in those previously published meta-analysis studies.

It has been proposed that gene expression could be potentially affected by genetic polymorphisms [21,61,62,63]. Alterations in the expression of PD-1 and PDL-1 were detected in many cancer types including gastric cancer, lung cancer, thyroid cancer, laryngeal carcinoma, extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma, and breast cancer [63,64,65,66,67,68,69].

PD-1/PD-L1 axis impairs T cell activation by preventing Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK and PI3K-AKT signaling pathways, which are mainly believed to promote proliferation and differentiation of T cell [70]. The inhibitory regulation of PD-1/PD-L1 is typically compared to a brake in T cell activation [71]. PD-L1 is exerted by tumors to escape from immune system. Tumor-specific PD-L1-expression was not prognostic in colorectal cancer, while high immune cell-specific PD-1 expression was associated with a prolonged overall survival [72]. It has been revealed that high expression of PD-1 on peripheral blood T cell subsets is correlated with poor prognosis of metastatic gastric cancer [73]. Fang et al. [74] reported that the peripheral blood PD-1 expression was significantly higher in breast cancer patients than benign breast tumors. PD-1 and PD-L1 expression have been shown to be associated with adverse clinicopathological features in clear cell renal carcinoma [75].

This meta-analysis has however several limitations. Firstly, there are relatively small sample sizes of studies for some polymorphisms that should be expanded. Secondly, we have included in this meta-analysis only studies published in English, thus publication bias may have occurred. Thirdly, obvious heterogeneities were found in certain polymorphisms. Differences in ethnic background, type of cancer, and other baseline characteristics of participants may contribute to between-study heterogeneities. Lastly, gene-gene and gene-environment interactions which may affect cancer susceptibility were not evaluated in this meta-analysis due to lack of sufficient data. Therefore, the results of this meta-analysis should be cautiously interpreted.

In conclusion, the current meta-analysis suggests that rs2227981 and rs11568821 polymorphisms of PD-1 and the rs4143815 polymorphism of PD-L1 were associated with protection against cancer, while PD-1 rs7421861 polymorphism significantly increased cancer risk.

4. Methods

4.1. Literature Search

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases for publications that studied the association between PD-1 and PD-L1 polymorphisms and cancer risk. The last search was updated on 18 December 2019. The following search terms were used; “programmed cell death 1 or PDCD1 or PD-1, or CD279, or programmed death-1-ligand 1 or CD274 or B7-H1” and “polymorphism or single nucleotide polymorphism or SNP or variation” and “cancer or carcinoma, or tumor”.

The process of recognizing eligible studies is presented in Figure 1. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows. (1) The studies evaluated the association between the PD-1 and PD-L1 polymorphisms and cancer risk, (2) studies with necessary information on genotype or allele frequencies to estimate ORs and 95% Cis, (3) studies with human subjects, and (4) case-control design. We excluded reviews, conference papers, and other studies that were published as abstracts only.

4.2. Data Extraction

The data were recovered from eligible articles independently by two authors. Disagreements were discussed with the third investigator. The following information was recorded for each study: first author’s name, publication year, patient’s nationality, genotypes, and allele frequencies.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

We performed a meta-analysis to assess the association between PD-1 and PD-L1 polymorphisms and cancer susceptibility. The observed genotype frequencies in the controls were tested for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) using the chi-squared test.

Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated to evaluate the association between PD-1 and PD-L1 polymorphisms and cancer risk in five genetic models, which were heterozygous, homozygous, dominant, recessive, and allele. The strength of the association between each polymorphism and cancer risk was assessed by pooled odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Z-test was used for statistical significance of the pooled OR. We estimated the between-study heterogeneity by the Q-test and I2 test: If I2 < 50% and P > 0.1, the fixed effects model was used to estimate the ORs and the 95% CI; otherwise, the random effects model was applied.

We evaluated publication bias using funnel plots for visual inspection and conducting quantitative estimations with Egger’s test.

Sensitivity analysis was achieved by excluding each study in turn to assess the stability of the results. All analyses were achieved by STATA 14.1 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

5. Conclusions

The findings of our meta-analysis proposed that PD-1 rs2227981, rs11568821, rs7421861, as well as PD-L1 rs4143815 polymorphisms associated with overall cancer susceptibility. Further well-designed studies with large sample sizes are warranted to confirm our findings.

Acknowledgments

Andrzej Malecki was supported by Institute of Physiotherapy and Health Sciences, The Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice. Saeid Ghavami was supported by Research Manitoba New Investigators Operating Grant and CancerCare Manitoba Operating grant.

Author Contributions

M.H. conceptualized and designed the study, conducted statistical analysis, and proofread the final draft. S.S., S.K., and A.M.-R. searched the literature, extracted the data, and prepared the figures. S.G. and E.W. conducted the final proofread, discussed the results, and prepared the final draft of manuscript. A.M. conducted the final proofread and provided information about cancer involvement. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R.L., Torre L.A., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stadler Z.K., Thom P., Robson M.E., Weitzel J.N., Kauff N.D., Hurley K.E., Devlin V., Gold B., Klein R.J., Offit K. Genome-wide association studies of cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:4255–4267. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.7816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redd P.S., Lu C., Klement J.D., Ibrahim M.L., Zhou G., Kumai T., Celis E., Liu K. H3K4me3 mediates the NF-kappaB p50 homodimer binding to the pdcd1 promoter to activate PD-1 transcription in T cells. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1483302. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1483302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hua Z., Li D., Xiang G., Xu F., Jie G., Fu Z., Jie Z., Da P., Li D. PD-1 polymorphisms are associated with sporadic breast cancer in Chinese Han population of Northeast China. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011;129:195–201. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ivansson E.L., Juko-Pecirep I., Gyllensten U.B. Interaction of immunological genes on chromosome 2q33 and IFNG in susceptibility to cervical cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010;116:544–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.10.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Z., Li N., Zhu Q., Zhang G., Han Q., Zhang P., Xun M., Wang Y., Zeng X., Yang C., et al. Genetic variations of PD1 and TIM3 are differentially and interactively associated with the development of cirrhosis and HCC in patients with chronic HBV infection. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2013;14:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keir M.E., Butte M.J., Freeman G.J., Sharpe A.H. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008;26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chamoto K., Al-Habsi M., Honjo T. Role of PD-1 in Immunity and Diseases. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2017;410:75–97. doi: 10.1007/82_2017_67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thommen D.S., Schumacher T.N. T Cell Dysfunction in Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:547–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He Q.F., Xu Y., Li J., Huang Z.M., Li X.H., Wang X. CD8+ T-cell exhaustion in cancer: Mechanisms and new area for cancer immunotherapy. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2019;18:99–106. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/ely006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Memarnejadian A., Meilleur C.E., Shaler C.R., Khazaie K., Bennink J.R., Schell T.D., Haeryfar S.M.M. PD-1 Blockade Promotes Epitope Spreading in Anticancer CD8(+) T Cell Responses by Preventing Fratricidal Death of Subdominant Clones to Relieve Immunodomination. J. Immunol. 2017;199:3348–3359. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gato-Canas M., Zuazo M., Arasanz H., Ibanez-Vea M., Lorenzo L., Fernandez-Hinojal G., Vera R., Smerdou C., Martisova E., Arozarena I., et al. PDL1 Signals through Conserved Sequence Motifs to Overcome Interferon-Mediated Cytotoxicity. Cell Rep. 2017;20:1818–1829. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dougan M. Checkpoint Blockade Toxicity and Immune Homeostasis in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:1547. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuol N., Stojanovska L., Nurgali K., Apostolopoulos V. PD-1/PD-L1 in disease. Immunotherapy. 2018;10:149–160. doi: 10.2217/imt-2017-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juchem K.W., Sacirbegovic F., Zhang C., Sharpe A.H., Russell K., McNiff J.M., Demetris A.J., Shlomchik M.J., Shlomchik W.D. PD-L1 Prevents the Development of Autoimmune Heart Disease in Graft-versus-Host Disease. J. Immunol. 2018;200:834–846. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J., Bu X., Wang H., Zhu Y., Geng Y., Nihira N.T., Tan Y., Ci Y., Wu F., Dai X., et al. Cyclin D-CDK4 kinase destabilizes PD-L1 via cullin 3-SPOP to control cancer immune surveillance. Nature. 2018;553:91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature25015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ribas A. Adaptive Immune Resistance: How Cancer Protects from Immune Attack. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:915–919. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Witt D.A., Donson A.M., Amani V., Moreira D.C., Sanford B., Hoffman L.M., Handler M.H., Levy J.M.M., Jones K.L., Nellan A., et al. Specific expression of PD-L1 in RELA-fusion supratentorial ependymoma: Implications for PD-1-targeted therapy. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2018;65:e26960. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng B., Ren T., Huang Y., Sun K., Wang S., Bao X., Liu K., Guo W. PD-1 axis expression in musculoskeletal tumors and antitumor effect of nivolumab in osteosarcoma model of humanized mouse. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018;11:16. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0560-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Vooght K.M., van Wijk R., van Solinge W.W. Management of gene promoter mutations in molecular diagnostics. Clin. Chem. 2009;55:698–708. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.120931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gomez G.V.B., Rinck J.A., Oliveira C., Silva D.H.L., Mamoni R.L., Lourenco G.J., Moraes A.M., Lima C.S.P. PDCD1 gene polymorphisms as regulators of T-lymphocyte activity in cutaneous melanoma risk and prognosis. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2018;31:308–317. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haghshenas M.R., Naeimi S., Talei A., Ghaderi A., Erfani N. Program death 1 (PD1) haplotyping in patients with breast carcinoma. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011;38:4205–4210. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0542-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haghshenas M.R., Dabbaghmanesh M.H., Miri A., Ghaderi A., Erfani N. Association of PDCD1 gene markers with susceptibility to thyroid cancer. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2017;40:481–486. doi: 10.1007/s40618-016-0579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X.F., Jiang X.Q., Zhang J.W., Jia Y.J. Association of the programmed cell death-1 PD1.5 C>T polymorphism with cervical cancer risk in a Chinese population. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016;15 doi: 10.4238/gmr.15016357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y., Zhang H.L., Kang S., Zhou R.M., Wang N. The effect of polymorphisms in PD-1 gene on the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer and patients’ outcomes. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017;144:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma Y., Liu X., Zhu J., Li W., Guo L., Han X., Song B., Cheng S., Jie L. Polymorphisms of co-inhibitory molecules (CTLA-4/PD-1/PD-L1) and the risk of non-small cell lung cancer in a Chinese population. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015;8:16585–16591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mojtahedi Z., Mohmedi M., Rahimifar S., Erfani N., Hosseini S.V., Ghaderi A. Programmed death-1 gene polymorphism (PD-1.5 C/T) is associated with colon cancer. Gene. 2012;508:229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Namavar Jahromi F., Samadi M., Mojtahedi Z., Haghshenas M.R., Taghipour M., Erfani N. Association of PD-1.5 C/T, but Not PD-1.3 G/A, with Malignant and Benign Brain Tumors in Iranian Patients. Immunol. Investig. 2017;46:469–480. doi: 10.1080/08820139.2017.1296858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pirdelkhosh Z., Kazemi T., Haghshenas M.R., Ghayumi M.A., Erfani N. Investigation of Programmed Cell Death-1 (PD-1) Gene Variations at Positions PD1.3 and PD1.5 in Iranian Patients with Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Middle East J. Cancer. 2018;9:13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savabkar S., Azimzadeh P., Chaleshi V., Nazemalhosseini Mojarad E., Aghdaei H.A. Programmed death-1 gene polymorphism (PD-1.5 C/T) is associated with gastric cancer. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench. 2013;6:178–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin L., Guo H., Zhao L., Wang J. The programmed death-1 gene polymorphism (PD-1.5 C/T) is associated with non-small cell lung cancer risk in a Chinese Han population. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014;7:5832–5836. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yousefi A.R., Karimi M.H., Shamsdin S.A., Mehrabani D., Hosseini S.V., Erfani N., Bolandparvaz S., Bagheri K. PD-1 Gene Polymorphisms in Iranian Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Labmedicine. 2013;44:241–244. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou R.M., Li Y., Wang N., Huang X., Cao S.R., Shan B.E. Association of programmed death-1 polymorphisms with the risk and prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Genet. 2016;209:365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qiu H., Zheng L., Tang W., Yin P., Cheng F., Wang L. Programmed death-1 (PD-1) polymorphisms in Chinese patients with esophageal cancer. Clin. Biochem. 2014;47:612–617. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramzi M., Arandi N., Saadi M.I., Yaghobi R., Geramizadeh B. Genetic Variation of Costimulatory Molecules, Including Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4, Inducible T-Cell Costimulator, Cluster Differentiation 28, and Programmed Cell Death 1 Genes, in Iranian Patients with Leukemia. Exp. Clin. Transpl. 2018 doi: 10.6002/ect.2017.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ren H.T., Li Y.M., Wang X.J., Kang H.F., Jin T.B., Ma X.B., Liu X.H., Wang M., Liu K., Xu P., et al. PD-1 rs2227982 Polymorphism Is Associated with the Decreased Risk of Breast Cancer in Northwest Chinese Women: A Hospital-Based Observational Study. Medicine. 2016;95:e3760. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan D., Sheng L., Yi Q.H. Correlation of PD-1/PD-L1 polymorphisms and expressions with clinicopathologic features and prognosis of ovarian cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2018;21:287–297. doi: 10.3233/CBM-170357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang W., Chen S., Chen Y., Lin J., Lin J., Wang Y., Liu C., Kang M. Programmed death-1 polymorphisms is associated with risk of esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma in the Chinese Han population: A case-control study involving 2740 subjects. Oncotarget. 2017;8:39198–39208. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang W., Chen Y., Chen S., Sun B., Gu H., Kang M. Programmed death-1 (PD-1) polymorphism is associated with gastric cardia adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015;8:8086–8093. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ge J., Zhu L., Zhou J., Li G., Li Y., Li S., Wu Z., Rong J., Yuan H., Liu Y., et al. Association between co-inhibitory molecule gene tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms and the risk of colorectal cancer in Chinese. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2015;141:1533–1544. doi: 10.1007/s00432-015-1915-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bayram S., Akkiz H., Ulger Y., Bekar A., Akgollu E., Yildirim S. Lack of an association of programmed cell death-1 PD1.3 polymorphism with risk of hepatocellular carcinoma susceptibility in Turkish population: A case-control study. Gene. 2012;511:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.09.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shamsdin S.A., Karimi M.H., Hosseini S.V., Geramizadeh B., Fattahi M.R., Mehrabani D., Moravej A. Associations of ICOS and PD.1 Gene Variants with Colon Cancer Risk in The Iranian Population. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2018;19:693–698. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.3.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Catalano C., da Silva Filho M.I., Frank C., Jiraskova K., Vymetalkova V., Levy M., Liska V., Vycital O., Naccarati A., Vodickova L., et al. Investigation of single and synergic effects of NLRC5 and PD-L1 variants on the risk of colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0192385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du W., Zhu J., Chen Y., Zeng Y., Shen D., Zhang N., Ning W., Liu Z., Huang J.A. Variant SNPs at the microRNA complementary site in the B7-H1 3’-untranslated region increase the risk of non-small cell lung cancer. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017;16:2682–2690. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tao L.-H., Zhou X.-R., Li F.-C., Chen Q., Meng F.-Y., Mao Y., Li R., Hua D., Zhang H.-J., Wang W.-P., et al. A polymorphism in the promoter region of PD-L1 serves as a binding-site for SP1 and is associated with PD-L1 overexpression and increased occurrence of gastric cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2016;66:309–318. doi: 10.1007/s00262-016-1936-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xie Q., Chen Z., Xia L., Zhao Q., Yu H., Yang Z. Correlations of PD-L1 gene polymorphisms with susceptibility and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma in a Chinese Han population. Gene. 2018;674:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou R.M., Li Y., Liu J.H., Wang N., Huang X., Cao S.R., Shan B.E. Programmed death-1 ligand-1 gene rs2890658 polymorphism associated with the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in smokers. Cancer Biomark. 2017;21:65–71. doi: 10.3233/CBM-170269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen Y.B., Mu C.Y., Chen C., Huang J.A. Association between single nucleotide polymorphism of PD-L1 gene and non-small cell lung cancer susceptibility in a Chinese population. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;10:e1–e6. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng S., Zheng J., Zhu J., Xie C., Zhang X., Han X., Song B., Ma Y., Liu J. PD-L1 gene polymorphism and high level of plasma soluble PD-L1 protein may be associated with non-small cell lung cancer. Int. J. Biol. Markers. 2015;30:e364–e368. doi: 10.5301/jbm.5000170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang W., Li F., Mao Y., Zhou H., Sun J., Li R., Liu C., Chen W., Hua D., Zhang X. A miR-570 binding site polymorphism in the B7-H1 gene is associated with the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma. Hum. Genet. 2013;132:641–648. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fathi F., Faghih Z., Khademi B., Kayedi T., Erfani N., Gahderi A. PD-1 Haplotype Combinations and Susceptibility of Patients to Squamous Cell Carcinomas of Head and Neck. Immunol. Investig. 2019;48:1–10. doi: 10.1080/08820139.2018.1538235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hashemi M., Bahari G., Tabasi F., Markowski J., Malecki A., Ghavami S., Los M.J. LAPTM4B gene polymorphism augments the risk of cancer: Evidence from an updated meta-analysis. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2018;22:6396–6400. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hashemi M., Moazeni-Roodi A., Ghavami S. Association between CASP3 polymorphisms and overall cancer risk: A meta-analysis of case-control studies. J. Cell Biochem. 2019;120:7199–7210. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hashemi M., Moazeni-Roodi A., Bahari G., Taheri M., Ghavami S. Association between miR-34b/c rs4938723 polymorphism and risk of cancer: An updated meta-analysis of 27 case-control studies. J. Cell Biochem. 2019;120:3306–3314. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zou J., Wu D., Li T., Wang X., Liu Y., Tan S. Association of PD-L1 gene rs4143815 C>G polymorphism and human cancer susceptibility: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019;215:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Da L.S., Zhang Y., Zhang C.J., Bu L.J., Zhu Y.Z., Ma T., Gu K.S. The PD-1 rs36084323 A > G polymorphism decrease cancer risk in Asian: A meta-analysis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2018;214:1758–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang J., Zhao T., Xu C., Huang J., Yu H. The association between polymorphisms in the PDCD1 gene and the risk of cancer: A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine. 2016;95:e4423. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dong W., Gong M., Shi Z., Xiao J., Zhang J., Peng J. Programmed Cell Death-1 Polymorphisms Decrease the Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis Involving Twelve Case-Control Studies. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0152448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mamat U., Arkinjan M. Association of programmed death-1 gene polymorphism rs2227981 with tumor: Evidence from a meta analysis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015;8:13282–13288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lim Y.W., Chen-Harris H., Mayba O., Lianoglou S., Wuster A., Bhangale T., Khan Z., Mariathasan S., Daemen A., Reeder J., et al. Germline genetic polymorphisms influence tumor gene expression and immune cell infiltration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E11701–E11710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1804506115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu Y., Zhao T., Jia Z., Cao D., Cao X., Pan Y., Zhao D., Zhang B., Jiang J. Polymorphism of the programmed death-ligand 1 gene is associated with its protein expression and prognosis in gastric cancer. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018;34:1201–1207. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Salmaninejad A., Khoramshahi V., Azani A., Soltaninejad E., Aslani S., Zamani M.R., Zal M., Nesaei A., Hosseini S.M. PD-1 and cancer: Molecular mechanisms and polymorphisms. Immunogenetics. 2018;70:73–86. doi: 10.1007/s00251-017-1015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Erdogdu I.H. MHC Class 1 and PDL-1 Status of Primary Tumor and Lymph Node Metastatic Tumor Tissue in Gastric Cancers. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2019;2019:4785098. doi: 10.1155/2019/4785098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yeo M.K., Choi S.Y., Seong I.O., Suh K.S., Kim J.M., Kim K.H. Association of PD-L1 expression and PD-L1 gene polymorphism with poor prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 2017;68:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yarchoan M., Albacker L.A., Hopkins A.C., Montesion M., Murugesan K., Vithayathil T.T., Zaidi N., Azad N.S., Laheru D.A., Frampton G.M., et al. PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden are independent biomarkers in most cancers. JCI Insight. 2019;4:126908. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.126908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu D., Cheng J., Xue K., Zhao X., Wen L., Xu C. Expression of Programmed Death-Ligand 1 in Laryngeal Carcinoma and its Effects on Immune Cell Subgroup Infiltration. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2018;2018:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s12253-018-0501-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Salhab M., Migdady Y., Donahue M., Xiong Y., Dresser K., Walsh W., Chen B.J., Liebmann J. Immunohistochemical expression and prognostic value of PD-L1 in Extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma: A single institution experience. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2018;6:42. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0359-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Botti G., Collina F., Scognamiglio G., Rao F., Peluso V., De Cecio R., Piezzo M., Landi G., De Laurentiis M., Cantile M., et al. Programmed Death Ligand 1 (PD-L1) Tumor Expression Is Associated with a Better Prognosis and Diabetic Disease in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:459. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Patsoukis N., Brown J., Petkova V., Liu F., Li L., Boussiotis V.A. Selective effects of PD-1 on Akt and Ras pathways regulate molecular components of the cell cycle and inhibit T cell proliferation. Sci. Signal. 2012;5:ra46. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.LaFleur M.W., Muroyama Y., Drake C.G., Sharpe A.H. Inhibitors of the PD-1 Pathway in Tumor Therapy. J. Immunol. 2018;200:375–383. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berntsson J., Eberhard J., Nodin B., Leandersson K., Larsson A.H., Jirstrom K. Expression of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand PD-L1 in colorectal cancer: Relationship with sidedness and prognosis. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1465165. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1465165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shi B., Li Q., Ma X., Gao Q., Li L., Chu J. High expression of programmed cell death protein 1 on peripheral blood T-cell subsets is associated with poor prognosis in metastatic gastric cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018;16:4448–4454. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fang J., Shao Y., Su J., Wan Y., Bao L., Wang W., Kong F. Diagnostic value of PD-1 mRNA expression combined with breast ultrasound in breast cancer patients. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2018;14:1527–1535. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S168531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ueda K., Suekane S., Kurose H., Chikui K., Nakiri M., Nishihara K., Matsuo M., Kawahara A., Yano H., Igawa T. Prognostic value of PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urol. Oncol. 2018;36:499. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]