Abstract

Suppressing HIV viral load through daily antiretroviral therapy (ART) substantially reduces the risk of HIV transmission, however, the potential population impact of treatment as prevention (TasP) is mitigated due to challenges with sustained care engagement and ART adherence. For an undetectable viral load (VL) to inform decision making about transmission risk, individuals must be able to accurately classify their VL as detectable or undetectable. Participants were 205 HIV-infected young men who have sex with men (YMSM) and transgender women (TGW) from a large cohort study in the Chicago area. Analyses examined correspondence among self-reported undetectable VL, study-specific VL, and most recent medical record VL. Among HIV-positive YMSM/TGW, 54% had an undetectable VL (<200 copies/mL) via study-specific laboratory testing. Concordance between self-report and medical record VL values was 80% and between self-report and study-specific laboratory testing was 73%; 34% of participants with a detectable study-specific VL self-reported an undetectable VL at last medical visit, and another 28% reported not knowing their VL status. Periods of lapsed viral suppression between medical visits may represent a particular risk for the TasP strategy among YMSM/TGW. Strategies for frequent viral load monitoring, that are not burdensome to patients, may be necessary to optimize TasP.

Keywords: Viral Load, undetectable, Medical Records, treatment as prevention, young MSM

INTRODUCTION

The landmark HPTN 052 study established that viral suppression, achieved through antiretroviral therapy (ART), reduced the risk of HIV transmission by 96% in serodiscordant heterosexual couples [1]. More recently, a study of 1,166 male-female and male-male couples [2] and a study of 358 male-male couples [3] engaging in condomless sex while the HIV positive partner was virally suppressed reported no phylogenetically linked transmissions to the HIV negative partner. Studies have shown associations between ART scale up and reduced HIV incidence at the community level [4–6]. From these findings, the concept of “treatment as prevention” (TasP) has been advanced as a strategy that simultaneously reduces the harmful impact of ongoing HIV replication [7] in infected persons as well as transmission risk [8].

Questions have been raised about the real-world, population-level impact of TasP due to the challenges of achieving high levels of engagement in care and viral suppression among HIV-infected individuals [9]. For example, a retrospective study of 38,000 serodiscordant couples in China found that treating the HIV-infected partners reduced the risk of HIV transmission by 26% [10], suggesting lower protective effects in real-world settings than in clinical trials. Other questions have been raised as to whether the protective benefits of TasP may be reduced or eliminated by increases in condomless sex [11]. In 2008, Switzerland’s National HIV/AIDS Commission released recommendations on condom use stating that HIV-positive persons may discontinue condom use if their viral load (VL) was suppressed to undetectable levels for at least 6 months on ART and if they had no other STIs [12]. These recommendations were widely discussed among professionals in the global HIV communities and evidence suggests they have impacted condom use decision making. For example, Newcomb and colleagues reported that most MSM recruited through a geospatial sexual networking app had a discussion in which a potential partner who was HIV positive stated that they had an undetectable VL and this disclosure was often linked to a desire to have sex without a condom [13]. Advocates have called for recognition of an undetectable VL as a “third HIV status” and that “undetectable = untransmittable.” These messages are laudable in terms of reducing stigma, anxiety about transmission, and educating about the impact of viral suppression to undetectable levels; however, real-world evidence outside of highly controlled trials is still limited.

Research is needed to identify possible vulnerabilities in the TasP strategy. Reliability is a critical consideration—viral suppression to an undetectable level can only eliminate the risk of HIV transmission if one is indeed undetectable at the time of sexual contact. Errors could occur because of incorrectly remembering VL from the most recent medical visit or because VL changed since that time. Health literacy research over a decade ago examined concordance of self-reported VL with medical records. One study found that 26% of the HIV positive participants were unable to correctly describe VL [14] and other studies found moderate agreement between self-reported VL and medical records [15, 16]. Agreement between self-report and medical records for CD4 T cell count was higher than for VL, which may reflect that CD4 count had been emphasized as a health indicator for much longer than VL, potentially elevating the salience as a patient-provider discussion topic. With the more recent advent of TasP and highly publicized discussions of VL rebound when ART stops in the context of research to eradicate HIV, viral suppression has taken on increased salience among HIV patients and providers.

The current study examines correspondence between self-reported undetectable VL at last medical visit and current study-specific VL in a large cohort of young men who have sex with men (YMSM) and transgender women (TGW) with HIV. Supplemental analyses were performed from participants on whom medical records could be accessed by the research team. Younger people may have worse health literacy than older adults because of less experience with healthcare, or the opposite may be true because of greater fluency with technology for managing information. YMSM are important in the HIV epidemic because they are the only risk group in the US to recently be showing increases in the number of new HIV infections [17] and because young people have consistently been found to have poorer outcomes at each stage of the cascade of HIV care [18].

METHODS

Study Design & Recruitment

Data were collected between February 2015 and June 2017 as part of RADAR, a longitudinal cohort study of YMSM and YTGW living in the Chicago metropolitan area [19, 20]. The primary objective of this cohort study is to apply a multilevel perspective [21] to a syndemic of health issues associated with HIV among YMSM and YTGW [22].

Diverse methods for participant recruitment were selected in order to achieve the multiple cohort, accelerated longitudinal design [23]. First, a subset of participants from two cohorts, Project Q2 (n=67) and Crew 450 (n=162), who were first recruited in 2007 and 2010 respectively, were eligible for enrollment. In 2015, a third cohort (current n=468) was recruited. Participants were recruited using a variety of methods including venue based recruiting, social media (e.g. Facebook), and incentivized snow ball sampling. At the time of enrollment into their original respective cohorts, all participants were between 16 and 20 years of age, born male, spoke English, and had a sexual encounter with a man in the previous year or identified with a sexual minority label (e.g., “gay”). Next, the RADAR cohort was expanded through an iterative process where serious romantic partners were recruited at each visit, thereby creating a dynamic dyadic network. Romantic partners who were assigned male at birth were eligible for enrollment into the cohort regardless of gender identity or sexual orientation. Romantic partners who were assigned female at birth, or were older than 29, completed a study visit but were not enrolled in the cohort. Lastly, cohort members were allowed to refer a maximum of three YMSM peers for enrollment into the study as long as they were between 16 and 29 years of age.

Measures

Demographics.

Demographic information was self-reported at each visit. Participants reporting a Hispanic/Latino ethnicity were coded as such, regardless of their racial identity.

HIV status.

At each study visit, participants not previously diagnosed with HIV received HIV testing with the Alere Determine™ HIV 1/2 Ag/Ab Combo 4th generation rapid test. Laboratory confirmation of this rapid HIV diagnostic test followed current recommendations [24, 25].

HIV care cascade.

The HIV care cascade was calculated as five stages [9]. Diagnosis of HIV infection was defined by laboratory-confirmed detection of HIV-1 or −2 infection, as described above. Linkage to care, engagement in care, and ART initiation were defined using the following interviewer administered questions, respectively: “Have you ever seen a health care provider for HIV related care?”, “In the past 6 months, how many times have you seen a health care provider for HIV related care?”, and “Have you ever taken any HIV medications that were prescribed to you?”. A participant had to have seen a health care provider for HIV-related care at least once in the past 6 months to be considered engaged in care. Following the convention of recent studies of TasP [2, 3] and HIV surveillance [26–29], a participant was considered to be virally suppressed if their VL was <200 copies/mL as assessed through study-specific laboratory testing (described below).

Medication adherence.

Participants who were currently taking an ART medication were asked: “When was the last time you missed a dose of any of these HIV medications? If you took only a portion of a dose on one or more days, please report that dose(s) as being missed”. Response options ranged from past week to never missing a dose [30]. Participants who indicated missing a dose in the prior week were subsequently administered a 7-day timeline follow-back to more precisely determine the total number of missed doses. Participants indicating having missed two or more doses in the past week were classified as non-adherent.

Viral load.

There were three different sources for VL data. First, during the computer-assisted self-interview prevalent HIV-positive participants were asked, “What was the result of your most recent viral load test (undetectable, detectable, I don’t know)?” (referred to as self-report). Next, each HIV positive participant provided a blood sample which was treated with EDTA-anticoagulation agent and from which plasma VL testing was performed with the Abbott RealTime HIV-1 RNA PCR (sensitivity of 40 copies/mL; referred to as “study-specific”). Lastly, all participants were requested to sign an authorization for release of medical records from their primary healthcare provider as well as the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH). Medical records (service date and VL) retrieved via primary healthcare providers were separately extracted by two trained research staff members and resulting data was reviewed by a third staff member for quality assurance. Medical records retrieved from CDPH were electronically accessed via their Enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting System (eHARS). An undetectable VL was defined as fewer than 200 copies/mL for both study-initiated laboratory testing and data extracted from medical records. “Blips,” or transient small increases in VL during prolonged viral suppression, were defined as >1000 copies/mL [31].

Condomless anal sex (CAS).

Participants’ were asked to identify their most recent sex partners (maximum of 4) in the past 6 months and provide information on their sexual behavior with each. Data on sexual partnership, including partner HIV status, number of insertive and receptive anal sex acts, and condom usage, was collected using the HIV-Risk Assessment for Sexual Partnerships (H-RASP)[32, 33]. From these data, participants were coded as having engaged in insertive or receptive condomless anal sex in the past 6 months with an HIV negative partner or unknown status partner (No/Yes). The relationship between CAS and VL was adjusted using demographic variables in order to remove any potentially confounding effects.

Analytic Sample

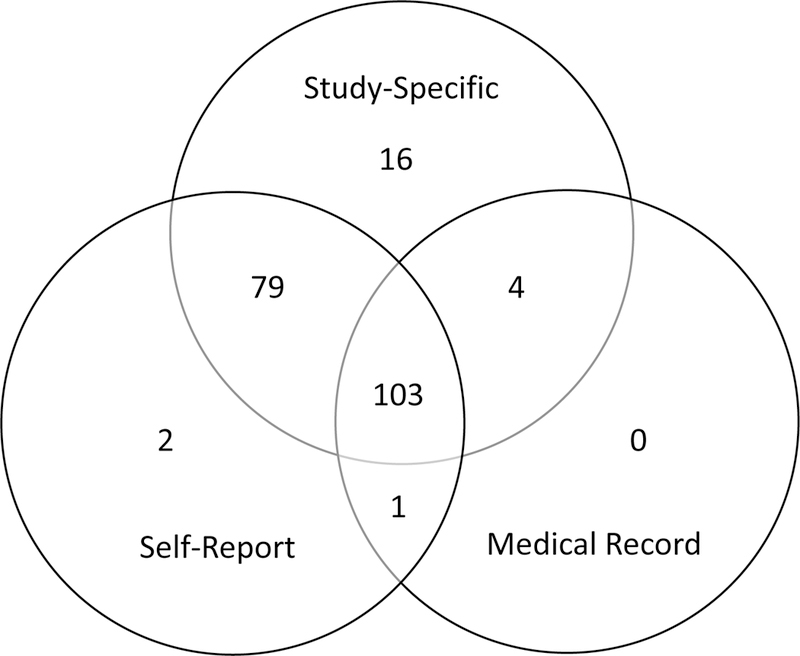

HIV-positive participants who had completed a study visit prior to July 1, 2017, were included in these analyses (n=214). Because rapid HIV testing occurred after a participant completed the survey portion of their visit, incident HIV-positive cases were not asked questions specific to their positive status nor were they approached to sign an authorization for release of medical records. In these instances, data were taken from their first subsequent visit where they would have been aware of their positive status prior to beginning the survey. However, there were nine participants who had not completed this 6-month follow-up visit at time of analysis, so 205 participants were included in the final analytic sample. Missing data was present for each of the three VL data sources so sample sizes for self-report, study-specific, and medical record sources were 185, 202, and 108 respectively (see Figure 1, a Venn diagram that illustrates sample sizes for pairwise comparisons reported in subsequent analyses). Medical records were obtained from 148 (72.2%) participants, 133 (64.9%) contained at least one VL value, and 108 (52.7%) contained a VL value within one year prior to the survey completion date. Comparing participants from whom we did or did not receive medical records, no significant differences were found in time since diagnosis, log viral load, age, or race/ethnicity.

Figure 1.

Sample size of viral load data sources

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of the analytic sample (n=205) are displayed in Table I. The mean age was 24.4 (SD=4.2) years and the median time since HIV diagnosis was 2.6 years (IQR: 0.8 – 4.7). The majority of participants self-identified as black or African American (132, 64.4%), followed by Hispanic/Latino (46, 22.4%), multi-racial (16, 7.8%), white (8, 3.9%), and other (3, 1.5%). In terms of gender identity, 181 (88.3%) participants identified as male while 22 (10.7%) identified as transgender female and 2 (1.0%) identified as a different category.

Table I.

Demographic characteristics of HIV positive sample (n=205)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (M=24.4, SD=4.2) | ||

| 16–20 | 34 | 16.6 |

| 21–24 | 104 | 50.7 |

| 25–29 | 53 | 25.9 |

| 30+ | 14 | 6.8 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Black or African American | 132 | 64.4 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 46 | 22.4 |

| White | 8 | 3.9 |

| Multi-Racial | 16 | 7.8 |

| Other | 3 | 1.5 |

| Birth Sex | ||

| Male | 205 | 100.0 |

| Female | 0 | 0.0 |

| Gender Identity | ||

| Male | 181 | 88.3 |

| Transgender | 22 | 10.7 |

| Not Listed | 2 | 1.0 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Gay | 161 | 78.5 |

| Bisexual | 25 | 12.2 |

| Queer | 2 | 1.0 |

| Unsure/Questioning | 3 | 1.5 |

| Straight/Heterosexual | 9 | 4.4 |

| Not Listed | 5 | 2.4 |

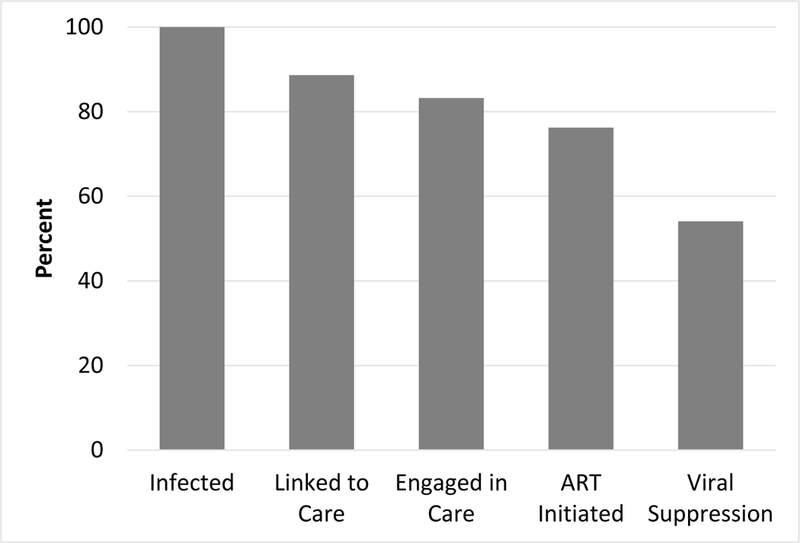

The percent of participants who met or exceeded the criteria for each of the stages of the cascade of care is shown in Figure 2. Of the 205 HIV-positive participants, 9.8% (n=20) had missing data and thus were excluded from this analysis. All participants knew they were HIV-positive at time of data collection, 88.6% had been linked to care, 83.2% were engaged in care in the prior 6 months, 76.2% had initiated ART, and 54.1% were virally suppressed via study-specific laboratory testing. Among those who had ever taken ART, 91.5% (n=129) were currently taking ART. Of the active ART users, 11.3% reported ART non-adherence in the past week.

Figure 2.

HIV care cascade (n=185)

Note: Linked to care defined as ever seeing a healthcare provider for HIV related care. Engaged in care defined as seeing a provider for HIV care in prior 6 months. ART initiation defined as having ever taken ART medications. Viral suppression defined as VL <200 copies/mL as assessed through study-specific laboratory testing.

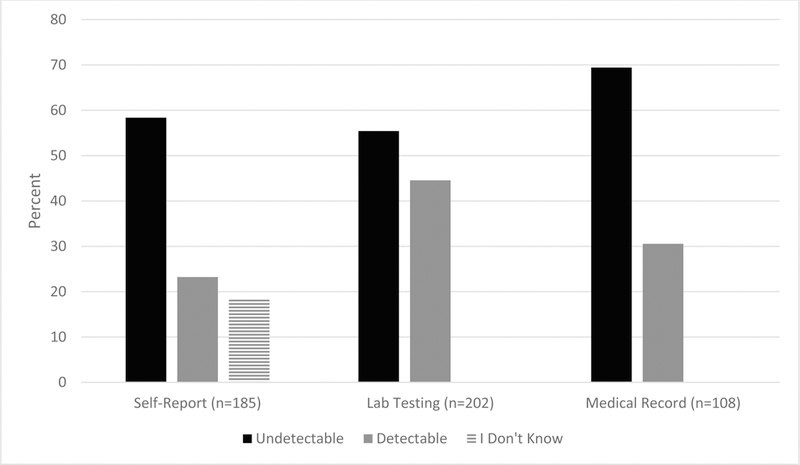

VL statuses from self-report (n=185), study-specific (n=202), and medical record data (n=108) sources are depicted in Figure 3. For self-report, 58.4% were undetectable, 23.2% detectable, and 18.4% did not know their VL status. There were eight instances where participants self-reported having an undetectable VL, but were not currently taking ART medication; this represented 8.4% of all self-reported undetectable VL responses.

Figure 3.

Viral load status from self-report, study-specific laboratory testing, and medical record data sources

Note: For study-specific lab testing and medical records undectable was defined as VL <200 copies/mL.

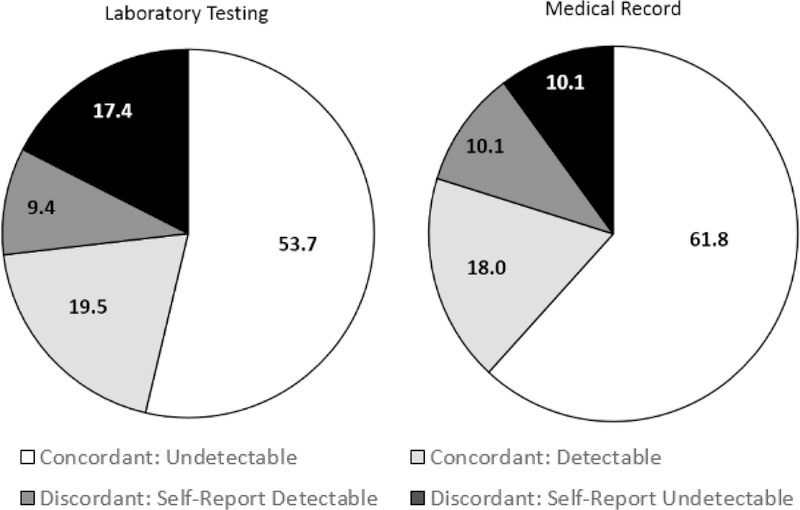

For study-specific laboratory testing, 55.4% had an undetectable VL while 44.6% had a detectable status. Among those with a detectable VL, 86.7% had >1,000 copies/mL. For the participants who self-reported an undetectable or detectable VL (i.e., eliminating those reporting unknown VL status) and for whom study-specific VL data were available L (n=149), concordance was 73.2% (Figure 4, left). Among the participants who had a study-specific detectable VL and self-reported data (n=76), 34.2% self-reported an undetectable VL (Figure 4, right). Sensitivity analyses using a more conservative cutoff for undetectable VL defined by the lower limit of detection of our laboratory assay (40 copies/mL) showed similar proportions of concordance between study-specific values and self-report data (e.g., 20.8% were detectable on laboratory assay but self-reported undetectable versus 19.5% as shown in Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Concordancy of self-report viral load status with study-specific laboratory testing (n=149) and medical record (n=89).

Note: For study-specific lab testing and medical records undectable was defined as VL <200 copies/mL.

Within the subset of 108 participants with abstracted medical record data, 69.4% (n=75) had an undetectable VL, while 30.6% (n=33) had a detectable VL. Concordance between self-report and medical record data (n=89) was 79.8%. Among those who had a detectable viral load in their medical record, 27.3% self-reported differently that they had an undetectable viral load. The median number of days between survey completion date and participants’ most recent medical record in which VL data was present was 76 days (IQR: 36 – 145). No significant differences (p > .05) were found between the aforementioned concordance using medical record data from the previous year and when a less restrictive criteria of the previous two years was used (77.3%, n=97).

After controlling for age and race, no statistically significant differences were found when examining the associations between self-reported VL detection status and odds of engaging in insertive or receptive condomless anal sex (CAS) with an HIV negative partner in the past 6 months (see Table II). Among the participants who self-reported a detectable VL and reported having sex with an HIV negative partner (n=29), 41.4% reported engaging in both insertive and receptive CAS, in the past 6 months. For study-specific VL detection status, unlike self-reported, participants with a detectable VL were found to be significantly more likely to report insertive CAS (OR=3.51; 95% CI: 1.31–9.44), but not receptive CAS (OR=1.33; 95% CI: 0.55–9.44). Among this group (n=37), 48.6% and 51.4% of participants reported engaging in insertive and receptive CAS, respectively, in the past 6 months with an HIV negative or unknown status partner.

Table II.

Associations between viral suppression and condomless anal sex within serostatus unknown/ serodiscordant sexual partnerships using logistic regression

| Insertive CAS | Receptive CAS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% OR | OR | 95% OR | |||

| Model 1 | ||||||

| Self-report VL status (ref=Undetectable) | 2.33 | 0.89 | 6.09 | 0.85 | 0.35 | 2.08 |

| Race (ref=Non-Black) | 0.48 | 0.21 | 1.09 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 1.15 |

| Age | 1.11 | 1.00 | 1.24 | 1.01 | 0.91 | 1.11 |

| Model 2 | ||||||

| Study-specific VL status (ref=Undetectable) | 3.77 | 1.48 | 9.57 | 1.65 | 0.72 | 3.80 |

| Race (ref=Non-Black) | 0.35 | 0.14 | 0.86 | 0.45 | 0.20 | 0.99 |

| Age | 1.09 | 0.99 | 1.21 | 1.01 | 0.92 | 1.11 |

CAS = condomless anal sex; OR = odds ratio

DISCUSSION

In a community sample of predominately racial/ethnic minority HIV positive YMSM and TGW living in the Chicago area, nearly 80% had made it to the stage in the cascade of care of initiating ART within a median of 3.4 months after diagnosis. Approximately half were currently virally suppressed based on study-specific laboratory tests. The estimated proportion achieving viral suppression is similar to the U.S. estimates of 55.5% among men aged ≥ 13 years [34] and Chicago surveillance estimates of 48% [35].

This study focused on concordance between self-reported undetectable VL, study-specific laboratory testing and VL from the most recent medical record data available. The overall proportion of participants with an undetectable VL across each of these methods varied, with the highest estimates from medical record chart review (69.4%), then self-report (58.4%) and study-specific testing (55.4%). Why was the proportion of YMSM with viral suppression highest in medical records? One possibility is the “white coat adherence” phenomenon where medication adherence improves in the time immediately preceding clinic visits to receive affirmations or avoid lecturing on the need for increased adherence. One such study found that approximately two thirds of participants had superior ART adherence in the days leading up to a clinic visit [36]. We posit that when participants have a VL test during their study-specific visit it is less salient because there is no clinical encounter with a provider who might critique treatment compliance if VL is detectable. As such, we hypothesize that VL values from study-specific tests may more accurately reflect modal VL status among YMSM because of the lack of a “white coat effect.” If this is true, then surveillance system estimates of viral suppression that primarily rely on VL values obtained from routine medical care likely are overestimating viral suppression in the community [37] and community-based cohort studies with VL testing represent an important complement. Another explanation is instability in viral suppression over time. Study-specific laboratory testing reflected the participants current VL, which was a median of three months from the time of their medical visit, and for 10.1% of participants VL changed to detectable levels. Such fluctuations in viral suppression have been reported in prior epidemiological studies [38] and criteria for VL suppression in the care cascade may need to be made more stringent to better represent sustained viral suppression.

Concordance was approximately 7% higher between self-report and medical records (79.8%) than between self-report and study-specific data (73.2%), suggesting slightly greater accuracy in self-reported recollection of VL status from most recent medical visit than is reflected in current viral suppression. Of most relevance to HIV transmission was that 34.2% of participants who had a detectable viral load at the time of study visit self-reported an undetectable VL at their last medical visit. Another 27.6% of participants with a detectable VL at the study visit reported not knowing their VL status at the prior medical care provider visit. It is estimated that persons who are virally suppressed account for only a small proportion (2.5%) of HIV transmissions in the U.S. [39]. As is sometimes the case, there may be different considerations at the population and individual levels. At an individual level, a person may make decisions about the HIV transmission risk of condomless sex practices based on their recall of their most recent medical visit. Such discussions and decisions among MSM have recently been described in the literature [13, 40]. Our findings suggest that, at least among YMSM in our community sample, a significant proportion may incorrectly assume they have an undetectable VL. This represents a potentially significant limitation of TasP in a real world community setting when coupled with the fact that those who had a detectable VL based on laboratory assays were 3.8 times more likely to report insertive condomless anal sex with an HIV negative or unknown status partner than those who had an undetectable VL.

Findings from our study must be interpreted in the context of study limitations. First, study-specific laboratory obtained VL values came from a single time point and may not represent the participants modal VL over time. One potential consideration is that some proportion of the detectable VLs that were found using study-specific laboratory tests represented “blips” or transient small increases in VL during prolonged viral suppression [31]. Because 86.7% of participants classified as having a detectable VL had >1,000 copies in study laboratory assays it is unlikely these estimates could be completely explained by viral load “blips” or small differences between VL assays used for the study and clinical care. Sensitivity analyses setting the threshold for a detectable VL to >1,000 did not change the pattern of findings (results not reported). Second, self-reported VL was based on recalled VL from most recent medical visit and may not represent participants’ beliefs about their current VL. Future studies on the implementation of viral suppression as strategy to prevent HIV transmission should specifically ask about participants’ beliefs about their current viral suppression at the time samples are collected for VL assays. Third, there were a number of participants who refused to provide medical record releases or provided information for a provider from whom they were no longer actively receiving care. This could suggest that these individuals were less engaged with providers, or some care interruption was present. As such we consider our comparisons with data obtained from medical records to be exploratory. Fourth, in regards to medical record data, our study assumes participants had been given their VL testing results; however, this was not confirmed. Finally, the sample was a community sample rather than a probability sample, and, as such, findings may not generalize to the population of HIV positive YMSM.

Secondary HIV prevention efforts should emphasize the value of suppressive ART (TasP) for reducing transmission risk for HIV positive YMSM, but given nearly a third of those with a detectable viral load self-reported an undetectable status it is important to acknowledge this challenge to TasP; condom use is advisable unless sustained viral suppression can be confirmed. For primary HIV prevention, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and condom use promotion should continue. Epidemiological studies may benefit from developing and using measures of sustained viral load to assess the care cascade. Clinical care of YMSM could be enhanced by improving communication and counseling about importance of consistent ART adherence, and confirmation of ongoing and current viral suppression, before any condomless sex is advisable under the undetectable = untransmitable framework. In addition, recommendation of consistent use of condoms and/or PrEP by HIV uninfected partners would reduce risk of transmission. This study also suggests the potential significance of future innovations that improve adherence to daily ART medication, including the development of longer acting ART delivery systems which may require less frequent dosing, the creation of efficiencies for frequent VL monitoring, and/or the development of a “functional cure” after stopping ART that would maintain viral suppression.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the contributions of the RADAR study staff, particularly Antonia Clifford, Justin Franz, Roky Truong, Peter Cleary, and Hannah Hudson. Laboratory tests were performed by the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital Special Infectious Diseases Laboratory in Chicago, Illinois. Viral load data was obtained from some participants from the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH), and we thank them for providing these data with the consent of participants under the terms of our data use agreement. CDPH disclaims responsibility for any analysis, interpretations, or conclusions. B.M., R.D., and M.N. conceptualized the study. D.T.R, T.A.R., and E.M. obtained and extracted medical record data. R.T.D. supervised collection of laboratory data. D.T.R. performed statistical analyses. B.M. and D.T.R. drafted the article. All authors reviewed and approved the final article.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (U01DA036939). We acknowledge the support of the Third Coast Center for AIDS Research (P30AI117943) and the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (UL1TR001422). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest: Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen MS, et al. , Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med, 2011. 365(6): p. 493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodger AJ, et al. , Sexual activity without condoms and risk of hiv transmission in serodifferent couples when the hiv-positive partner is using suppressive antiretroviral therapy. JAMA, 2016. 316(2): p. 171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bavinton B, et al. , HIV treatment prevents HIV transmission in male serodiscordant couples in Australia, Thailand and Brazil, in International AIDS Society. 2017: Paris. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das M, et al. , Decreases in community viral load are accompanied by reductions in new HIV infections in San Francisco. PLoS One, 2010. 5(6): p. e11068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montaner JS, et al. , Association of highly active antiretroviral therapy coverage, population viral load, and yearly new HIV diagnoses in British Columbia, Canada: A population-based study. Lancet, 2010. 376(9740): p. 532–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solomon SS, et al. , Community viral load, antiretroviral therapy coverage, and HIV incidence in India: A cross-sectional, comparative study. The Lancet HIV. 3(4): p. e183–e190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents, Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2016, Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Programmatic update: Antiretroviral treatment as prevention (TASP) of HIV and TB. 2012. 22 December 2016]; Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70904/1/WHO_HIV_2012.12_eng.pdf.

- 9.Gardner EM, et al. , The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis, 2011. 52(6): p. 793–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jia Z, et al. , Antiretroviral therapy to prevent HIV transmission in serodiscordant couples in China (2003–11): a national observational cohort study. Lancet, 2013. 382(9899): p. 1195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bezemer D, et al. , A resurgent HIV-1 epidemic among men who have sex with men in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy. AIDS, 2008. 22(9): p. 1071–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vernazza P, et al. , Les personnes séropositives ne souffrant d’aucune autre MST et suivant un traitement antirétroviral efficace ne transmettent pas le VIH par voie sexuelle. Bulletin des médecins suisses, 2008. 89(5). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newcomb ME, et al. , Partner Disclosure of PrEP Use and Undetectable Viral Load on Geosocial Networking Apps: Frequency of Disclosure and Decisions about Condomless Sex. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolf MS, et al. , Relation between literacy and HIV treatment knowledge among patients on HAART regimens. AIDS Care, 2005. 17(7): p. 863–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalichman SC, Rompa D, and Cage M, Reliability and validity of self-reported CD4 lymphocyte count and viral load test results in people living with HIV/AIDS. Int J STD AIDS, 2000. 11(9): p. 579–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunningham CO, et al. , A comparison of HIV health services utilization measures in a marginalized population: self-report versus medical records. Med Care, 2007. 45(3): p. 264–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CDC. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015. 2016 30 January 2017]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/.

- 18.Zanoni BC and Mayer KH, The adolescent and young adult HIV cascade of care in the United States: exaggerated health disparities. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 2014. 28(3): p. 128–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mustanski B, et al. , Effects of parental monitoring and knowledge on substance use and HIV risk behaviors among young men who have sex with men: Results from three studies. AIDS and Behavior, 2017. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macapagal K, et al. , HIV Prevention Fatigue and HIV Treatment Optimism Among Young Men Who Have Sex With Men. AIDS Educ Prev, 2017. 29(4): p. 289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson BT, et al. , A network-individual-resource model for HIV prevention. AIDS Behav, 2010. 14(Suppl 2): p. 204–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mustanski B, et al. , Psychosocial health problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: Preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 2007. 34(1): p. 37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duncan SC, Duncan TE, and Hops H, Analysis of longitudinal data within accelerated longitudinal designs. Psychological Methods, 1996. 1(3): p. 236–248. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Association of Public Health Laboratories. Laboratory testing for the diagnosis of HIV infection: Updated recommendations. 2014 11 April 2017]; Available from: 10.15620/cdc.23447. [DOI]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Association of Public Health Laboratories. Technical update on HIV-½ differentiation assays. 2016 11 April 2017]; Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/40790.

- 26.Torian LV, Xia Q, and Wiewel EW, Retention in care and viral suppression among persons living with HIV/AIDS in New York City, 2006–2010. Am J Public Health, 2014. 104(9): p. e24–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yehia BR, et al. , Impact of age on retention in care and viral suppression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2015. 68(4): p. 413–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doshi RK, et al. , High rates of retention and viral suppression in the US HIV safety net system: HIV care continuum in the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, 2011. Clin Infect Dis, 2015. 60(1): p. 117–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen SM, et al. , HIV viral suppression among persons with varying levels of engagement in HIV medical care, 19 US jurisdictions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2014. 67(5): p. 519–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chesney MA, et al. , Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG Adherence Instruments. Aids Care, 2000. 12(3): p. 255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fung IC, et al. , The clinical interpretation of viral blips in HIV patients receiving antiviral treatment: are we ready to infer poor adherence? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2012. 60(1): p. 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mustanski B, Starks T, and Newcomb ME, Methods for the design and analysis of relationship and partner effects on sexual health. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 2014. 43(1): p. 21–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swann G, Newcomb ME, and Mustanski B, Validation of the HIV Risk Assessment of Sexual Partnerships (H-RASP): Comparison to a 2-Month Prospective Diary Study. Arch Sex Behav, 2017. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.CDC. Selected National HIV Prevention and Care Outcomes. 2016 28 February 2017]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/slideSets/index.html.

- 35.Chicago Department of Public Health, HIV/STI Surveillance Report 2016. 2016: Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Podsadecki TJ, et al. , “White coat compliance” limits the reliability of therapeutic drug monitoring in HIV-1-infected patients. HIV Clin Trials, 2008. 9(4): p. 238–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lesko CR, et al. , Measuring the HIV Care Continuum Using Public Health Surveillance Data in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2015. 70(5): p. 489–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nosyk B, et al. , The cascade of HIV care in British Columbia, Canada, 1996–2011: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis, 2014. 14(1): p. 40–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skarbinski J, et al. , Human immunodeficiency virus transmission at each step of the care continuum in the United States. JAMA Intern Med, 2015. 175(4): p. 588–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuhn E, et al. , Viral load strategy: impact on risk behaviour and serocommunication of men who have sex with men in specialized care. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2016. 30(9): p. 1561–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]