Fever is a pathophysiological response in which the body’s normal thermoregulatory set-point is adjusted upwards leading to an increase in body temperature. In contrast, hyperthermia occurs from excessive heat production or insufficient thermoregulation (e.g. heat stroke or drug reactions). Although temperature elevation is common in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) patients, a newly elevated body temperature should prompt consideration of a diagnostic evaluation. It is always prudent to consider the possibility of infection; however, for critically patients with acute brain pathologies in particular, elevated body temperature is common, even in the absence of infection. Body temperature may be elevated due to drugs, particularly antipsychotic, serotonergic, sympathomimetic, anaesthetic, and anticholinergics drugs[1]. Thyrotoxicosis and phaeochromocytoma should also be considered in the differential diagnosis. Often elevated temperature is multifactorial and, in many patients, particularly after major surgery, a specific cause is not found.

Although body temperature is recorded assiduously in the ICU[2], it is often unclear when or how to intervene when a patient’s body temperature is elevated. A recent individual patient data meta-analysis reported that more active fever management did not increase survival compared with less active fever management in an all-comers population of critically ill adults[3]. Survival by treatment group was similar in a range of subgroups defined by age, illness severity, receipt of specific organ supports, and presence versus absence of high fever at baseline. These data suggest that, in general, when it comes to active management of fever in ICU patients, although less may not be more, doing less to treat fever results in similar outcomes to doing more.

FEVER IN PATIENTS WITH INFECTIONS

Fever is a broadly conserved biological response to infection across many animal species including insects, reptiles, fish, and mammals[4]. It is logical that a response that occurs in such diverse species has an evolutionary advantage, particularly given that fever is metabolically costly[5]. Fever therapies have even been used in humans to treat infections including gonorrhoea and syphilis[4]. However, for patients with fever and suspected infection, the common practice of administering paracetamol to treat fever does not appear to either improve or worsen patient outcomes[6]. Moreover, in a phase two study evaluating active cooling to target normothermia in patients with sepsis who were sedated and mechanically ventilated, active temperature management reduced early mortality compared with usual care[7]. Routine cooling of septic patients to normothermia is the subject of ongoing research and is best considered an experimental therapy[8]. However, it important to note that cooling critically ill patients with infections to below a normal body temperature may be harmful[9, 10] and, if cooling is employed, particular care should be taken to avoid hypothermia.

TEMPERATURE MANAGEMENT IN PATIENTS WITH HYPOXIC BRAIN INJURIES

One group of patients where more stringent temperature management is recommended is those with hypoxic brain injuries. Therapeutic hypothermia improves survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes in neonates with moderate to severe hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy[11]. In adults, two phase two trials comparing therapeutic hypothermia at 32 to 34°C with a permissive approach to temperature management suggested that therapeutic hypothermia increased survival and improved neurological outcomes following out of hospital cardiac arrest[12, 13]. A subsequent trial comparing two hypothermia regimens (33°C and 36°C) showed that these resulted in similar outcomes[14]. Following this trial, there was widespread de-adoption of a 33°C target in Australian and New Zealand ICUs, which was associated with an increase frequency of fever, and a trend towards decreased survival[15]. Although further research evaluating temperature management in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients is underway, current guidelines recommend avoidance of fever in this group of patients[16].

TEMPERATURE MANAGEMENT IN PATIENTS WITH TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURIES

Thermoregulatory disturbances often complicate acute brain pathologies. Aggressive management of elevated body temperature is typically considered desirable in patients with brain pathologies such as traumatic brain injury (TBI), and stroke. Although a body temperature of over 39°C in the first 24 hours in ICU is associated with increased mortality risk in such patients[17], it is possible that fever is a marker of brain damage rather than a modifiable risk factor for adverse outcomes. Although strict maintenance of normothermia in patients with TBI might improve outcomes compared to a reactive approach of treating fever when it occurs, this is largely untested. Systematic evaluation of prophylactic normothermia in patients with TBI in a randomised trial is needed. However, in such patients, hypothermia reduces intracranial hypertension but appears to worsen outcomes compared with alternative approaches to reducing intracranial pressure[18].

SEVERE TEMPERATURE ELEVATION AND HYPERTHEMIA

Active control of temperature is clearly preferred in some situations. Very high body temperature is associated with increased mortality risk in most ICU patient groups[17, 19]. As peripheral thermometry can substantially underestimate core body temperature[20] and temperature can rise rapidly[1], it is prudent to monitor core body temperature continuously in critically ill patients with fever. Although uncommon, there are certainly instances where patients develop extremely high body temperature (>42°C) and die soon after[6]. In such patients, it is plausible that death is a direct consequence of elevated temperature. If a patient is critically ill, we submit that it is nearly always best to prevent core body temperature from exceeding 41°C.

In patients with hyperthermia, rather than fever, careful monitoring of body temperature and early intervention using physical cooling measures with or without neuromuscular paralysis is prudent. In this situation, impaired heat loss and/or excessive heat production can result in life-threatening complications such as rhabdomyolysis and secondary hyperkalaemia, metabolic acidosis, multi-organ failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation[1].

In patients with muscle rigidity and agitation, benzodiazepines can be used to reduce the generation of heat[1]. Although use of bromocriptine and dantrolene have been reported in patients with neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and chlorpromazine and cyproheptadine can be used in serotonin syndrome, most patients with hyperthermia can be managed with supportive care and conventional cooling methods rather than requiring specific drug therapies[1]. One notable exception to this is in patients with malignant hyperthermia where dantrolene should be administered promptly[1].

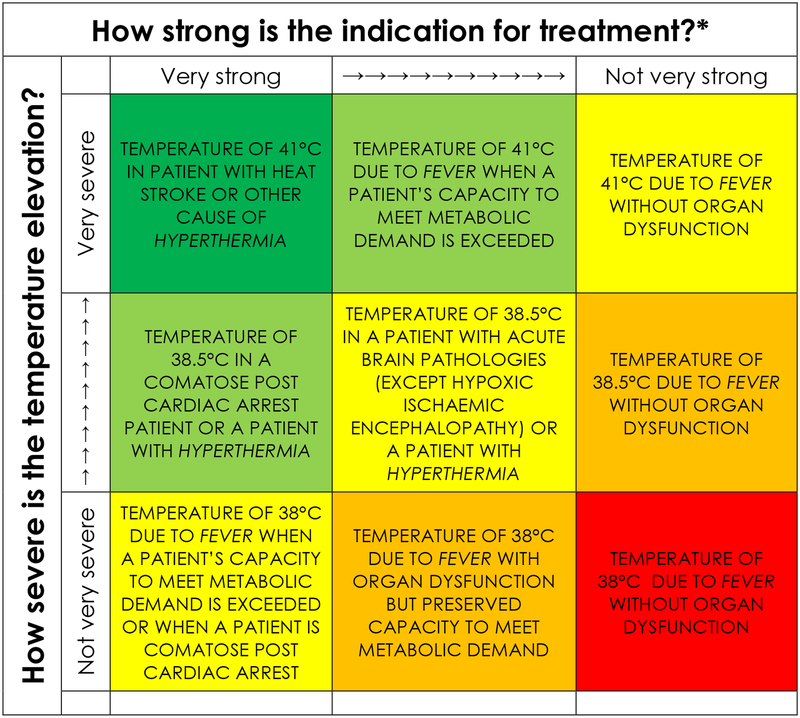

A suggested approach to management of elevated body temperature is shown in Figure 1. Prompt temperature reduction makes sense in patients with severely elevated body temperature due to hyperthermia because in these patients the primary problem may be failed thermoregulation. However, in many patient groups with elevated temperature we simply do not know whether less intervention is better when it comes to active temperature control in the critically ill.

Figure 1. When to Initiate Active Management of Elevated Body Temperature in the Critically II*.

* A strong indication for treatment combined with a severely elevated temperature is reflected by dark green shading, which corresponds to a situation where active management elevated body temperature very reasonable; red shading indicates situations where active temperature management may be less desirable; other shades indicate different degrees of certainty about the appropriateness of treatment.

Acknowledgements / Funding:

Dr. Young is the current recipient of a Health Research Council of New Zealand Clinical Practitioner Fellowship. Dr. Prescott is supported by K08 GM115859 from the US National Institutes of Health. The views in this manuscript do not reflect the position or policy of the US government or Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement:

Dr Young reports receiving speaker’s fees from Bard Healthcare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jamshidi N, Dawson A, (2019) The hot patient: acute drug-induced hyperthermia. Aust Prescr 42: 24–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cutuli SL, Osawa EA, Glassford NJ, Marshall D, Eyeington CT, Eastwood GM, Young PJ, Bellomo R, (2018) Body temperature measurement methods and targets in Australian and New Zealand intensive care units. Crit Care Resusc 20: 241–244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young PJ, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Niven DJ, Schortgen F, Saxena M, Beasley R, Weatherall M, (2019) Fever control in critically ill adults. An individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Intensive Care Med [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young PJ, Saxena M, (2014) Fever management in intensive care patients with infections. Crit Care 18: 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baracos VE, Whitmore WT, Gale R, (1987) The metabolic cost of fever. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 65: 1248–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young P, Saxena M, Bellomo R, Freebairn R, Hammond N, van Haren F, Holliday M, Henderson S, Mackle D, McArthur C, McGuinness S, Myburgh J, Weatherall M, Webb S, Beasley R, Investigators H, Australian, New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials G, (2015) Acetaminophen for Fever in Critically Ill Patients with Suspected Infection. N Engl J Med 373: 2215–2224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schortgen F, Clabault K, Katsahian S, Devaquet J, Mercat A, Deye N, Dellamonica J, Bouadma L, Cook F, Beji O, Brun-Buisson C, Lemaire F, Brochard L, (2012) Fever control using external cooling in septic shock: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185: 1088–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young PJ, Bailey MJ, Beasley RW, Freebairn RC, Hammond NE, Haren FM, Harward ML, Henderson SJ, Mackle DM, McArthur CJ, McGuinness SP, Myburgh JA, Saxena MK, Turner A, Webb SA, Bellomo R, The ACTG, (2017) Protocol and statistical analysis plan for the Randomised Evaluation of Active Control of Temperature versus Ordinary Temperature Management (REACTOR) trial. Crit Care Resusc 19: 81–87 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Itenov TS, Johansen ME, Bestle M, Thormar K, Hein L, Gyldensted L, Lindhardt A, Christensen H, Estrup S, Pedersen HP, Harmon M, Soni UK, Perez-Protto S, Wesche N, Skram U, Petersen JA, Mohr T, Waldau T, Poulsen LM, Strange D, Juffermans NP, Sessler DI, Tonnesen E, Moller K, Kristensen DK, Cozzi-Lepri A, Lundgren JD, Jensen JU, Cooling, Surviving Septic Shock Trial C, (2018) Induced hypothermia in patients with septic shock and respiratory failure (CASS): a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Respir Med 6: 183–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mourvillier B, Tubach F, van de Beek D, Garot D, Pichon N, Georges H, Lefevre LM, Bollaert PE, Boulain T, Luis D, Cariou A, Girardie P, Chelha R, Megarbane B, Delahaye A, Chalumeau-Lemoine L, Legriel S, Beuret P, Brivet F, Bruel C, Camou F, Chatellier D, Chillet P, Clair B, Constantin JM, Duguet A, Galliot R, Bayle F, Hyvernat H, Ouchenir K, Plantefeve G, Quenot JP, Richecoeur J, Schwebel C, Sirodot M, Esposito-Farese M, Le Tulzo Y, Wolff M, (2013) Induced hypothermia in severe bacterial meningitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 310: 2174–2183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tagin MA, Woolcott CG, Vincer MJ, Whyte RK, Stinson DA, (2012) Hypothermia for neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 166: 558–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, Jones BM, Silvester W, Gutteridge G, Smith K, (2002) Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med 346: 557–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study G, (2002) Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 346: 549–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nielsen N, Wetterslev J, Cronberg T, Erlinge D, Gasche Y, Hassager C, Horn J, Hovdenes J, Kjaergaard J, Kuiper M, Pellis T, Stammet P, Wanscher M, Wise MP, Aneman A, Al-Subaie N, Boesgaard S, Bro-Jeppesen J, Brunetti I, Bugge JF, Hingston CD, Juffermans NP, Koopmans M, Kober L, Langorgen J, Lilja G, Moller JE, Rundgren M, Rylander C, Smid O, Werer C, Winkel P, Friberg H, Investigators TTMT, (2013) Targeted temperature management at 33 degrees C versus 36 degrees C after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 369: 2197–2206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salter R, Bailey M, Bellomo R, Eastwood G, Goodwin A, Nielsen N, Pilcher D, Nichol A, Saxena M, Shehabi Y, Young P, Australian, New Zealand Intensive Care Society Centre for O, Resource E, (2018) Changes in Temperature Management of Cardiac Arrest Patients Following Publication of the Target Temperature Management Trial. Crit Care Med 46: 1722–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donnino MW, Andersen LW, Berg KM, Reynolds JC, Nolan JP, Morley PT, Lang E, Cocchi MN, Xanthos T, Callaway CW, Soar J, Force IAT, (2015) Temperature Management After Cardiac Arrest: An Advisory Statement by the Advanced Life Support Task Force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation and the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation. Circulation 132: 2448–2456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saxena M, Young P, Pilcher D, Bailey M, Harrison D, Bellomo R, Finfer S, Beasley R, Hyam J, Menon D, Rowan K, Myburgh J, (2015) Early temperature and mortality in critically ill patients with acute neurological diseases: trauma and stroke differ from infection. Intensive Care Med 41: 823–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrews PJ, Sinclair HL, Rodriguez A, Harris BA, Battison CG, Rhodes JK, Murray GD, Eurotherm Trial C, (2015) Hypothermia for Intracranial Hypertension after Traumatic Brain Injury. N Engl J Med 373: 2403–2412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young PJ, Saxena M, Beasley R, Bellomo R, Bailey M, Pilcher D, Finfer S, Harrison D, Myburgh J, Rowan K, (2012) Early peak temperature and mortality in critically ill patients with or without infection. Intensive Care Med 38: 437–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxena MK, Taylor C, Billot L, Bompoint S, Gowardman J, Roberts JA, Lipman J, Myburgh J, (2015) The Effect of Paracetamol on Core Body Temperature in Acute Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomised, Controlled Clinical Trial. PLoS One 10: e0144740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]