Abstract

Background

Transplantation is the treatment of choice for many patients with end-stage organ disease. Despite advances in immunosuppression, long-term outcomes remain suboptimal, hampered by drug toxicity and immune-mediated injury, the leading cause of late graft loss. The development of therapies that promote regulation while suppressing effector immunity is imperative to improve graft survival and minimize conventional immunosuppression. Notch signaling is a highly conserved pathway pivotal to T cell differentiation and function, rendering it a target of interest in efforts to manipulate T cell-mediated immunity.

Methods

We investigated the pattern of Notch-1 expression in effector and regulatory T cells (Tregs) in both murine and human recipients of a solid organ transplant. Using a selective human anti-Notch-1 antibody (aNotch-1), we examined the effect of Notch-1 receptor inhibition in full MHC-mismatch murine cardiac and lung transplant models, and in a humanized skin transplant model. Based on our findings, we further employed a genetic approach to investigate the effect of selective Notch-1 inhibition in Tregs.

Results

We observed an increased proportion of Tregs expressing surface and intracellular (activated) Notch-1 compared to conventional T cells (Tconv), both in transplanted mice and in the peripheral blood of transplanted patients. In the murine cardiac transplant model, peri-transplant administration of aNotch-1 (days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10) significantly prolonged allograft survival compared to IgG-treated controls. Similarly, aNotch-1 treatment improved both histological and functional outcomes in the murine lung transplant model. The use of aNotch-1 resulted in a reduced proportion of both splenic and intra-graft Tconv, while increasing the proportion of Tregs. Furthermore, Tregs isolated from aNotch-1 treated mice showed enhanced suppressive function on a per-cell basis, confirmed with selective Notch-1 deletion in Tregs (Foxp3EGFPCreNotch1fl/fl). Notch-1 blockade inhibited the mTOR pathway and increased the phosphorylation of STAT5 in murine Tregs. Notch-1low Tregs isolated from human peripheral blood exhibited more potent suppressive capacity than Notch-1high Tregs. Lastly, the combination of aNotch-1 with costimulation blockade induced long-term tolerance in a cardiac transplant model, and this tolerance was dependent on CTLA-4 signaling.

Conclusion

Our data reveal a promising, clinically relevant approach for immune modulation in transplantation by selectively targeting Notch-1.

Keywords: Transplant, Immunology, Cardiac transplant, Lung transplant, Notch, Regulatory T cells, Tolerance

INTRODUCTION

Transplantation is the treatment of choice for many patients with end-stage kidney, liver, lung or heart disease, and is associated with significant improvement in both the quality and quantity of life1. Despite advances in cross-matching techniques and immunosuppression, the rate of allograft loss due to immune-mediated injury remains high2: current drug regimens non-selectively target both effector and regulatory T cells3, thereby failing to promote a more regulatory, tolerogenic profile, while generating a variety of adverse sequelae4. The ability to selectively influence T cell fate is of paramount interest in the field of transplantation: potential approaches include deletion of peripheral alloreactive effector T cells with induction therapy, inhibition of T cell activation by costimulatory blockade, interference with cytokine signaling, and promotion of active regulation by harnessing the regulatory potential of Tregs5, 6.

Notch signaling is an evolutionally highly conserved pathway that plays a significant role in immune cell fate-determination and differentiation7. The mammalian Notch family consists of four Notch receptors (Notch-1 – 4), and five ligands (delta-like ligand (DLL)-1, 3 and 4, Jagged-1 and 2)8. Notch-1 is critical to T cell lineage commitment9, 10, and an increasing body of data indicates that Notch is further involved in T cell survival and the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into various T helper cell subsets in the periphery11, 12.

Previous work by our group and others explored the role of Notch ligands on antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and demonstrated that blockade of the Notch ligand DLL1 prolonged allograft survival, while an agonistic antibody directed against Jagged2 precipitated rejection in an MHC class II-mismatched murine cardiac transplant model where graft survival is Treg-dependent13, 14. In a murine model of bone marrow transplantation, blockade of both DLL1 and DLL4 was shown to ameliorate both acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)15, 16, while T-cell-specific pan-Notch inhibition via expression of dominant negative Mastermind-like 1 (DNMAML) prolonged cardiac allograft survival, ameliorated GVHD and reduced the severity of disease in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a mouse model of multiple sclerosis17–19. More recently, Treg-specific deletion of Notch-1 was also shown to improve GVHD20. These data suggested that Notch signaling in APCs and T cells could be a potentially valuable therapeutic target in efforts to manipulate the alloimmune response. It is clear, however, that a highly targeted approach is required: pharmacological pan-Notch receptor inhibition using γ-secretase inhibitors (GSIs) was complicated by severe intestinal toxicity in mice21, mandating more selective Notch signaling inhibition to enhance the translational potential of this strategy.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that Notch-1 blockade could prolong allograft survival in murine organ transplant models, predominantly by targeting Treg subset. First, we showed that Notch-1 is highly expressed in Tregs compared to conventional T cells (Tconv), in both murine and human transplant recipients, confirming it as a potential target of interest in clinical transplantation. Next, we showed that mice treated with aNotch-1 demonstrated prolonged graft survival, fewer graft-infiltrating cells, and an increased proportion of intra-graft Tregs in full MHC-mismatch cardiac and lung transplant models. Tregs isolated from aNotch-1-treated mice showed more proliferation, less apoptosis and had greater suppressive properties. Treg-intrinsic effect of Notch-1 was confirmed using Foxp3EGFPCreNotch1fl/fl mice, where Notch-1 is deleted only in Foxp3-expressing Tregs. We further showed that Notch-1 blockade promoted tolerance synergistically with costimulation blockade in the full-MHC mismatch cardiac transplant model; this tolerance was dependent on CTLA-4 signaling and was allo-specific. Lastly, to explore the translational potential of this strategy, we tested the use of aNotch-1 treatment in a humanized skin transplant model: recipients treated with aNotch-1 had fewer graft-infiltrating T cells and lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines compared to controls. Our findings suggest an important role of Notch-1 in alloimmunity, particularly in acute rejection, and identify a potential target for manipulation of the T cell response and promotion of immune regulation by specifically enhancing the proportion and suppressive function of Tregs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Statement on Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Mice

C57BL/6J (B6, H-2b/I-Ab), BALB/c (H-2d/I-Ad), Rag1−/− (on C57BL/6 background) and NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtmWjl/SzJ (NSG) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Foxp3-GFP mice and Foxp3EGFPCreNotch1fl/fl mice were a generous gift from the Rudensky22 and Chatila20 laboratories, respectively. All animals were housed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Animal Care guidelines. The Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital Animal Management Committee approved all experiments (protocol numbers #5050 and 2016N000250, respectively).

Human kidney transplant cohort

Renal transplant recipients at our institution were recruited to a prospective, observational trial, for which they were eligible if admitted at least 14 days post-transplant to undergo a clinically-indicated graft biopsy for investigation of an acute rise in serum creatinine. The clinical research protocol was approved by the human research committee at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (IRB 2008P-00070); participants provided written informed consent. Blood was collected at the time of biopsy and a follow-up sample obtained 3 months later, during clinical quiescence. Immunosuppression consisted of anti-thymocyte globulin (1.5 mg/kg/day × 4 days) and IV methylprednisolone induction with tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil, followed by steroid withdrawal 1 week post-transplant in all but high-immunological risk patients. Blood samples taken at the 3-month follow-up were used for analysis. The demographics of this cohort are shown in Table S1.

Human peripheral mononuclear cell (PBMC) isolation

Human PBMCs were isolated from heparinized blood samples from healthy donors or kidney transplant recipients by density gradient centrifugation using Lymphoprep (StemCell technologies) and cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen in 10% DMSO-Human Serum AB (GemCell) until use.

Antibodies for animal studies

The anti-Notch-1 antibody (aNotch-1) and its control IgG antibody were generously provided by Dr. Christian Siebel at Genentech, Inc.. Briefly, aNotch-1 was generated using phage display technology; it is a fully human IgG1 antibody which potently inhibits the Notch-1 paralogue but no other Notch receptors, and binds with similarly high affinity to both the mouse and human orthologues23. aNotch-1 was administered at a dose of 5 mg/kg on days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 & 10 post-transplantation, unless otherwise stated; IgG was administered as a control antibody at the same dose and on the same schedule, according to the respective experiments. CTLA4-Ig (purchased from Bio X Cell) was given as a single dose (sCTLA4Ig; 250 μg/mouse, intraperitoneally) on day 2 post-transplantation. Rat anti-mouse CD25 mAb (PC61 clone; aCD25; 250 μg/mouse, intraperitoneally) was administered on days −6 and −1 before transplantation. Anti-CTLA4 (purchased from Bio X Cell, 400 μg/dose) was administered intraperitoneally on day 61, 63 and 65 post-cardiac transplantation.

Murine cardiac, skin and lung transplantation and thymectomy

Eight-week-old mice were used as allograft recipients throughout; the number of mice used in each experiment is documented in the figure legends.

Vascularized intra-abdominal heterotopic cardiac transplantation was performed as previously described, under isoflurane anesthesia (5% for induction and 2–3% for maintenance)24. Graft survival was assessed by daily palpation; rejection was defined as complete cessation of cardiac contractility and was confirmed by direct visualization.

Skin transplantation was performed as follows: briefly, 1 cm2 sections of tail skin were transplanted to the dorsal trunk of the recipient animals, under isoflurane anesthesia. Rejection was defined as complete loss of the skin graft from the transplant site. Lung transplant was performed as previously described25. Briefly, mice were intubated and mechanically ventilated under isoflurane anesthesia using a small animal ventilator (Harvard Apparatus). Peak airway pressure was measured at the end of the study to evaluate lung function, as previously described25. Thymectomy was performed via a retrosternal approach using an aspiration technique, as described by Lurie et al26.

Humanized skin transplant model

NSG mice reconstituted with human hematopoietic cells (hu-CD34) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Peripheral chimerism at levels exceeding 20% was confirmed by flow cytometry. Human skin was obtained as discarded tissue from plastic surgery (BWH IRB 2016P001844). A full thickness (1 cm2 section) human skin graft was transplanted to the dorsum of an anesthetized murine recipient using a sterile monofilament, non-absorbable suture. The grafted skin was monitored for signs of rejection, primarily change in color and necrosis. The skin graft, peripheral blood, spleen and lymph nodes were harvested for analyses on day 22 post-transplantation.

Isolation of intragraft lymphocytes

To isolate cells from the cardiac allografts, hearts were excised, minced and digested with 500 U/ml collagenase (Worthington Biochemical) for 30 minutes at 37˚C. Lungs were digested with 0.1 mg/ml collagenase D (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes at 37˚C, followed by Buffer 2 (0.1 M EDTA in PBS, pH 7.2) for 5 minutes before final suspension in Buffer 3 (5 mM EDTA, 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in PBS, pH 7.2). Human skin grafts were incubated with 30 Kunitz units/ml DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.2% collagenase type I (Invitrogen) for 2 hours at 37˚C with shaking (350 rpm). Isolated cells were then mechanically dissociated through a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences), and RBCs lysed using hypotonic ACK buffer (Lonza).

Histological and Immunohistochemical Assessment of Allografts

Five μm-thick, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections were stained with standard Haematoxylin/Eosin stain (H&E), while sections from murine cardiac and lung allografts were also stained with an Elastin stain; acute cellular rejection was semi-quantitatively graded (0R-3R, for cardiac allograft; and A0-A4 for lung allograft) according to the revised International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) guidelines. The extent of cellular infiltration and myocyte loss was also assessed.

Flow cytometry

Anti-mouse antibodies directed against CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53–6.7), CD25 (PC61), CD44 (IM7), CD62L (MEL-14), CTLA-4 (UC10–4F10–11), IL-17A (TC11–18H10), IL-4 (11B11), Thy1.2 (53–2.1), 7-AAD and Annexin V were purchased from BD Biosciences; antibodies directed against H-2Kb (AF6–88.5.5.3), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), mCD45 (30-F11), TIM-3 (F38–2E2) and Foxp3 (FJK-16s) were purchased from eBioscience; anti-phospho-S6 (Ser235/236) and phosphor-Stat5 (Tyr694) were from Cell Signaling, while antibodies against CD19 (6D5), CD11b (M1/70), F4/80 (BM8), B220 (RA3–6B2), Thy1.1 (OX-7), PD-1 (RMP1–30), LAG-3 (C9B7W), CD28 (37.51), ICOS (C398.4A), IL-10 (JES5–16E3), CD69 (H1.2F3), Nrp1 (3E12), TGF-β (TW7–16B4), Ki-67 (16A8), Helios (22F6) and Notch-1 (mN1A) were purchased from Biolegend, and goat anti-human IgG-Alexa488 was purchased from Invitrogen. Anti-human antibodies against CD3 (UCHT1), CD4 (OKT4), CD127 (A019D5), CD25 (M-A251), Notch-1 (MHN1–519) were purchased from Biolegend; anti-Foxp3 (236A/E7) was purchased from eBioscience and anti-hCD45 from BD Biosciences.

Cell suspensions were Fc-blocked for 20 min prior to staining for surface markers for 30 minutes in FACS buffer (2% rat serum in PBS) on ice. Intracellular staining of Foxp3 and IFN-γ was performed using the Fixation/Permeabilization Kit (eBioscience). For cytokine detection, cell suspensions were incubated for 6 hours with 50 ng/mL of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), 500 ng/mL ionomycin, and GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) in 10% FBS-RPMI, followed by surface staining, permeabilization, and intracellular staining of IFN-γ. Evaluation of apoptotic cells was performed using the Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Pharmingen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences) and BD FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Data obtained were analyzed using FlowJo software (version X, Tree Star).

Mixed lymphocyte reactions

Mixed lymphocyte reactions (MLR) were performed as described below and alloreactivity was assessed using ELISPOT assays (Granzyme B (R&D Systems), IFN-γ and IL-4 (BD Biosciences) and a Luminex-based multiplex cytokine assay (Millipore). Briefly, 0.5 × 106 splenocytes from either IgG- or aNotch-1-treated transplant recipients were cultured with 0.5 × 106 irradiated (30 Gy) allogeneic BALB/c splenocytes for 16 hours (Granzyme B), 24 hours (IFN-γ) or 48 hours (IL-4). Cytokine-linked spots were visualized and counted using an ELISPOT image analyzer (Cellular Technology); results were generated as spots/0.5 × 106 splenocytes. For the Luminex assays, cell-free supernatants of individual wells (plated in triplicate) were collected after 72 hours of MLR at 37˚C and 5% CO2 and analyzed using a pre-configured 11-plex mouse cytokine detection kit, as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Treg isolation and suppression assay

The mouse Treg suppression assay was performed using a proliferation dye-dilution assay. Foxp3-GFP and Foxp3EGFPCreNotch1fl/fl mice were sensitized by intraperitoneal injection of 15 × 106 splenocytes from naïve BALB/c mice on day 0; Foxp3-GFP mice subsequently received either 5 mg/kg IgG or aNotch-1 on days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 & 12; The mice were sacrificed on day 14; the spleen and lymph nodes were harvested and CD4+ cells were enriched using a mouse CD4+ isolation kit (Stem Cell Technologies). Tconv (CD4+Foxp3GFP−) and Tregs (CD4+Foxp3GFP+) were sorted using a FACSAria cell sorter. The flow-sorted CD4+GFP(Foxp3)+ cells were then co-cultured in varying ratios (1:1, 1:2, 1:4 and 1:8) with Tconv loaded with CellTrace Violet dye, as per the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen), in RPMI with 10% FCS for 96 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2 in the presence of anti-mouse CD3/CD28-conjugated beads (ThermoFisher). Cells were stained with viability dye (7-AAD, BD Biosciences) and cell proliferation was analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences).

The human Treg suppression assay was performed using a proliferation dye-dilution assay. Human Tregs (CD4+CD127−CD25+) and Tconv (CD4+CD127+CD25−) were flow-sorted from human PBMC using a FACSAria. Tconv were labeled with Cell Trace Violet (Invitrogen) and cultured with 5,000 Tregs per well in different ratios (Treg:Tconv 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, 1:8) in the presence of anti-human CD3/CD28-conjugated beads (Treg inspector beads, Miltenyi Biotech) in RPMI with 5% human serum for 5 days at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were stained with viability dye (7-AAD) and cell proliferation was analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences).

Statistical Analyses

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed, and a log-rank test was used to compare the groups. For paired two group comparisons, we used the paired t-test. For independent two group comparisons, we first tested the equality of variance by Levene’s test: if the equality of the variance held, we used the unpaired Student’s t-test for analysis; if the equality did not hold, we used Welch’s t-test for the comparison. Two-sample t-tests were corrected for multiple comparison using Holm-Sidak method. For multiple group comparisons, the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or two-way ANOVA test was used to determine differences, depending on the number of comparison groups. Multiple comparisons between levels were checked with Tukey post-hoc tests. Differences were considered significant for p ≤ 0.05. Prism software was used for data analysis and drawing graphs (GraphPad Software, Inc., San-Diego, CA). Data represent mean ± SD with at least 3 samples per studied group for all experiments. Morpheus matrix visualization and analysis tool (Broad Institute; https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus) was used to create a heatmap of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the markers analyzed; MFI values in the heat map were represented using the minimum and maximum of each independent row.

RESULTS

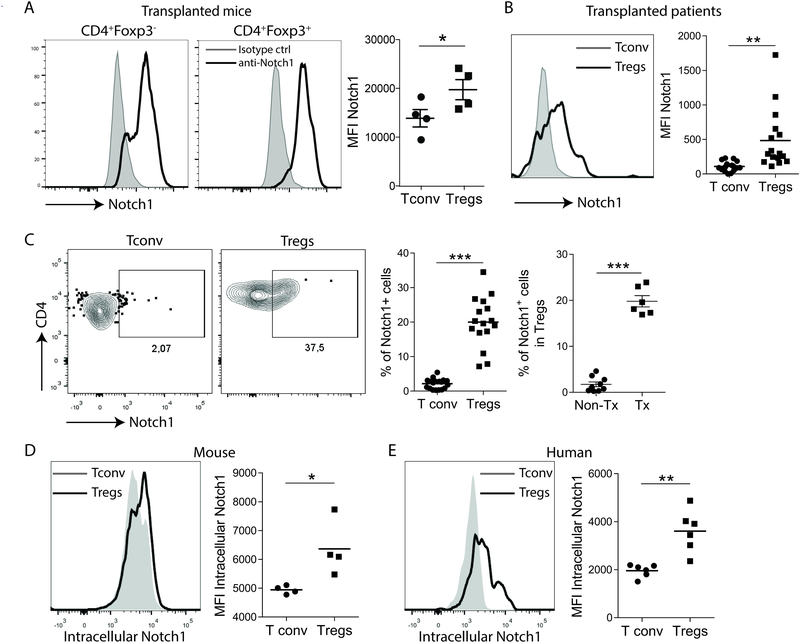

Notch-1 was highly expressed in Tregs compared to conventional T cells in mice and kidney transplant patients

As Notch-1 is critical in T helper cell differentiation27, we first examined the differential Notch-1 expression in Tconv and Tregs in the transplant setting. In the full MHC-mismatch murine cardiac transplant model, in which hearts retrieved from BALB/c mice (I-Ad/H-2d) were transplanted into C57BL/6J (B6; I-Ab/H-2b) recipients, a greater proportion of Tregs (CD4+Foxp3+) expressed surface Notch-1 than Tconv (CD4+FoxP3−, Figure 1A). This pattern of expression was also seen in kidney transplant patients (Figure 1B), while the proportion of Notch-1+Tregs was significantly higher in kidney transplant patients than non-transplanted healthy control subjects (Figure 1C). Upon ligand-receptor interaction and consequent receptor activation, the intracellular domain of Notch-1 is cleaved and translocates from the cellular surface into the nucleus, where it forms a nuclear transcription complex and promotes target gene transcription7, 28. We found that both mouse and human Tregs have a higher expression of activated intracellular Notch-1 compared to Tconv cells (Figure 1D and E), indicating that Notch-1 signaling pathway is more activated in Tregs. These results suggest that Notch-1 signaling within the Treg population might play a role in immune regulation in the transplant setting.

Figure 1. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) express higher levels of Notch-1 than conventional T cells (Tconv).

A, Mouse splenic Tregs (CD4+Foxp3+) expressed higher levels of Notch-1 than Tconv (CD4+Foxp3−) on day 7 post full MHC-mismatch cardiac transplantation. Representative flow cytometry plots illustrating the MFI of Notch-1 in Tconv and Tregs are shown (mean±SD, n=4, paired t-test, *p<0.05). B, In kidney transplant patients, Tregs (CD4+Foxp3+) in peripheral blood showed significantly higher expression of Notch-1 compared to Tconv. Histograms of Notch-1 expression in Tregs (black line) and Tconv (gray area) are shown (n=16, paired t-test, **p<0.01). C, Notch-1-positive cells comprised 2–3% and 20% of Tconv and Tregs, respectively, in kidney transplant recipients (left, n=16, paired t-test, ***p<0.001), with significant differences compared to healthy volunteers (right, n=8; representative flow cytometry plots of Notch-1 staining in Tconv and Tregs showing percentages of Notch-1-positive Tregs in non-transplant healthy volunteers (non-Tx) and kidney transplant patients (Tx) are shown; Welch’s t-test, ***p<0.001). D, Expression of intracellular Notch-1 by murine Tregs (black line) and Tconv (gray area) (n=4, paired t-test, *p<0.05). E, Human Tregs (black line) express more intracellular Notch-1 than T conv (gray area) (n=6, paired t-test, **p<0.01).

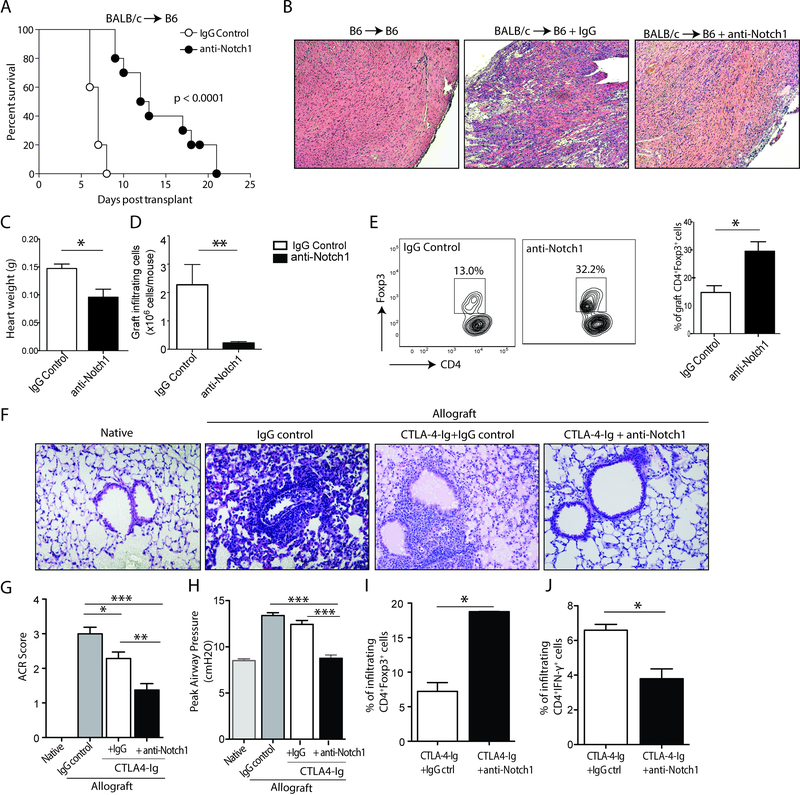

Inhibition of Notch-1 prolongs allograft survival in a full MHC-mismatch cardiac transplant model

To better understand the importance of Notch-1 signaling in alloimmunity, we tested the therapeutic effect of Notch-1 blockade in a full MHC-mismatch mouse cardiac transplant model. Recipient mice were treated with either control IgG or aNotch-1 at a dose of 5 mg/kg on days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 & 10 post-transplant. Allograft survival was significantly prolonged in aNotch-1-treated recipients compared to IgG-treated controls (MST 12.5 vs 7 days, p<0.0001), without associated toxicity (Figure 2A). Histological analyses of explanted allografts on day 7 post-transplant showed a diffuse lymphocyte infiltrate with multifocal myocyte damage in control IgG-treated mice. In contrast, preserved cardiac architecture with less cellular infiltrate was observed in aNotch-1-treated mice (Figure 2B). Grafts isolated from aNotch-1-treated mice weighed significantly less than those isolated from IgG-treated controls (Figure 2C). Similarly, the numbers of graft-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes were significantly lower in aNotch-1-treated mice (Figure 2D). Interestingly, however, the percentage of CD4+Foxp3+ cells isolated from grafts of aNotch-1-treated recipients was significantly higher compared to IgG-treated controls (Figure 2E).

Figure 2. Anti-Notch-1 treatment prolonged allograft survival in a full MHC- mismatch transplant model.

A, Significant prolongation in survival of full MHC-mismatch (BALB/c) cardiac allografts in B6 mice treated with aNotch-1 (5 mg/kg i.p. on days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, & 10 post-transplant) compared to control IgG by log-rank test (MST 12.5 vs. 7 days, n=6–10 mice per group; p<0.001). B, Histological appearance (H&E stain, 10X magnification) of the cardiac architecture, showing preserved cardiac myocyte arrangement and fewer infiltrating lymphocytes in mice treated with aNotch-1 (right) compared to those treated with IgG (middle); a syngeneic (B6 →B6) graft is shown for comparison (left); samples from a single representative mouse from each group shown, appearances characteristic on at least 3 repeat experiments. Cardiac allografts isolated from mice treated with aNotch-1 weighed significantly less (C; t-test, *p<0.05) and had fewer graft-infiltrating cells compared to those treated with IgG control (D; t-test, **p<0.01). E, Graft-infiltrating CD4+ lymphocytes isolated from mice treated with aNotch-1 were shown to contain a higher proportion of Tregs (CD4+Foxp3+) compared to IgG-treated controls (representative flow cytometry plots shown on left; t-test, *p<0.05, n=4 per group. In a full MHC-mismatch orthotopic lung transplant model (BALB/c to B6), histological appearance of the lung allograft (F; H&E stain, 20X magnification) demonstrates preserved airway patency and minimal lymphocyte infiltration in mice treated with aNotch-1 and CTLA4-Ig (right) compared to those treated with control IgG and CTLA4-Ig (second from right). A contralateral native lung (left) and an allograft without any treatment (second from left) are shown for reference. G, Lung allografts retrieved from mice treated with aNotch-1 and CTLA4-Ig showed significantly better ACR scores compared with IgG-treated controls (n=3 per group). H, Peak airway pressures were significantly lower in aNotch-1 and CTLA4-Ig-treated mice compared to controls. Graft-infiltrating cells isolated from lung allografts treated with aNotch-1 and CTLA4-Ig demonstrated I, a higher proportion of CD4+Foxp3+ cells and J, a lower proportion of CD4+IFN-γ-producing cells compared to CTLA-4-Ig-treated group (one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test (G-H), t-test (I-J), *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001).

Notch-1 blockade prevents allograft rejection in mouse lung transplant model

Next, we tested aNotch-1 in an orthotopic full MHC-mismatch lung transplant model (BALB/c → B6), which is a more stringent transplant model. Mice were given one dose of CTLA4-Ig on day 2 and treated either with control IgG or aNotch-1 (5 mg/kg, days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 post-transplantation). Lung allografts treated with CTLA4-Ig and control IgG were visibly shrunken and discolored with hemorrhage compared to control isografts, whereas CTLA4-Ig and aNotch-1-treated allografts appeared healthier with significantly fewer signs of injury (Supplemental Figure S1). In accordance with the macroscopic observations, histological evaluation revealed that the combination therapy of CTLA4-Ig and aNotch-1 significantly modified the anti-graft response (Figure 2F), indicated by a significant decrease in the acute cellular rejection scores (ACR, Figure 2G), as well as in peak airway pressures (Figure 2H). Similar to the heart transplant model, there was an increased percentage of Tregs infiltrating the lung allografts (Figure 2I) and a lower percentage of graft-infiltrating IFN-γ-producing T cells in the aNotch-1 treated group (Figure 2J). The combined data from both murine cardiac and lung transplant models suggest that Notch-1 blockade could be an effective strategy to prevent acute rejection and promote regulation.

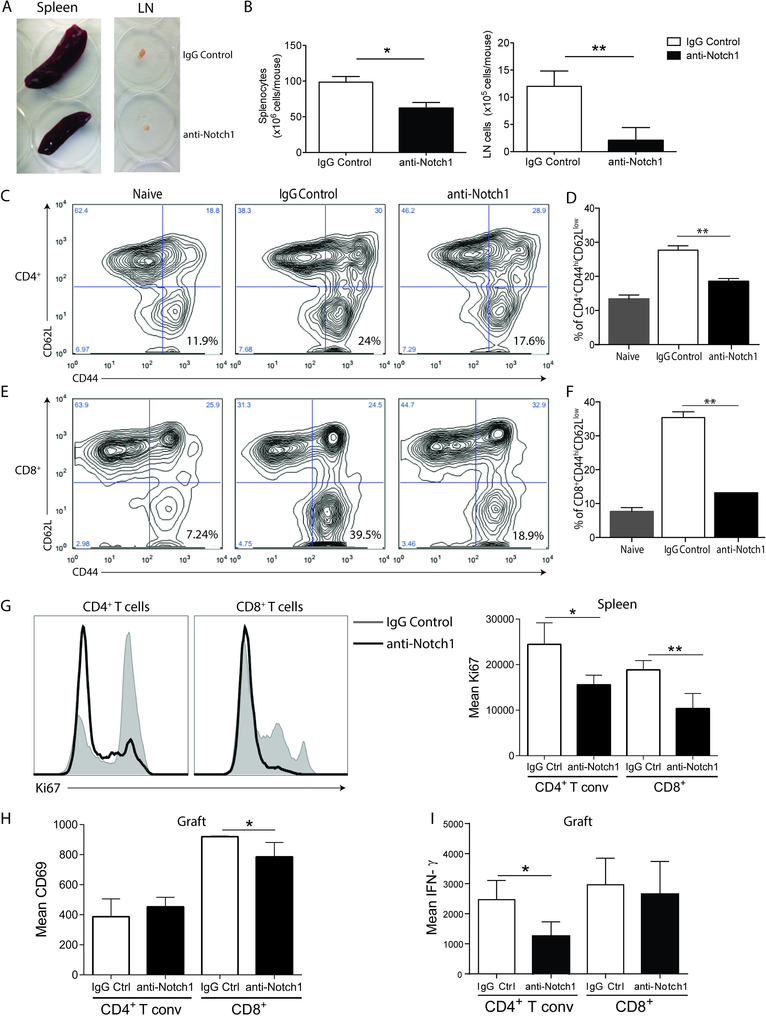

Notch-1 blockade significantly reduced the frequency and function of splenic effector memory T cells

To determine the mechanisms by which blockade of Notch-1 confers allograft protection, we first examined the effect of aNotch-1 on the spleen and draining lymph nodes (dLN, bilateral para-aortic lymph nodes) retrieved on day 7 post-transplantation. Spleens and dLN retrieved from aNotch-1-treated mice were smaller (Figure 3A) with fewer lymphocytes than those retrieved from mice treated with IgG (Figure 3B). Furthermore, the percentage of T effector/memory cells (CD44hiCD62Llow) in splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was significantly lower in aNotch-1-treated mice compared to IgG-treated controls (Figure 3C–F). We also found lower expression of the proliferation marker Ki67 in both CD4+Foxp3− and CD8+ splenic T cells (Figure 3G). Intragraft T cells had lower expression of the activation marker CD69 in CD8+ T cells (Figure 3H) and lower production of IFN-γ by CD4+ T cells compared to IgG-treated controls (Figure 3I), suggesting impaired activation of these cells. No differences in CD28 expression or IL-17 production were seen within these subsets.

Figure 3. Inhibition of Notch-1 reduced the splenic effector/memory T cell population and production of inflammatory cytokines.

A, Macroscopic appearances of spleens and lymph nodes isolated from IgG or aNotch-1-treated mice on day 7 post transplantation; a single representative mouse from each group is shown. B, Absolute number of splenocytes (left) and draining lymph nodes (dLN) cells (right) in mice treated with aNotch-1 or control IgG: aNotch-1-treated mice had fewer splenocytes and dLN cells compared with IgG-treated controls (Welch’s t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01). C-F, aNotch-1-treated mice showed lower frequency of CD4+ T effector cells (Teff; defined as CD44hiCD62Llow, C and D) and CD8+ effector cells (E and F), compared to IgG-treated mice (representative flow cytometry plots shown (C & E; n=4 per group; D & F; one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test, ** p<0.01). G, Expression of the proliferation marker Ki67 in splenic CD4+ Tconv and CD8+ T cells from IgG or aNotch-1-treated mice on day 7 post-transplant. CD69 expression (H) or IFN-γ production (I) in graft-infiltrating CD4+ Tconv and CD8+ T cells from IgG or aNotch-1-treated mice on day 7 post-transplant. G-I, n=4–5 mice per group, *p<0.05, **p<0.01 by two sample t-tests with multiple testing correction using Holm-Sidak method; alpha=0.05, number of t-tests=2.

In addition, cellular supernatants collected following the incubation of splenocytes isolated from IgG- and aNotch-1-treated mice on day 7 post-transplant with irradiated donor-type splenocytes were examined for cytokine production by Luminex (Supplemental Figure S2). Supernatants collected from aNotch-1-treated mice demonstrated significantly lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines compared to IgG-treated controls, including IL-1β, IL-6, IFN-γ and TNF-α. Neither the levels of IL-17 (1.37±0.002 vs 2.72±0.83 pg/mL; p=0.1), nor those of IL-5 (1.75±0.25 vs 1.65±0.12; p=0.77), were significantly different between groups (data not shown). There was a significant, albeit modest, reduction in the levels of IL-10 in the supernatants collected from aNotch-1-treated mice compared to IgG-treated controls (35.1±10.95 vs 98.9±25.38; p=0.04). These data were mirrored by the detection of significantly lower amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokine production by splenocytes isolated from aNotch-1-treated mice when stimulated by irradiated donor-type splenocytes and assessed by ELISPOT: Granzyme B (177.3±9.5 vs 313.0±20.2 spots/0.5×106 splenocytes in IgG-treated controls; p=0.0037) and IFN-γ (497.7±67.95 vs 1063±29.36 spots/0.5×106 splenocytes in IgG-treated controls; p=0.0016); IL-4 secretion was unaffected (117.0±42.55 vs 117.3±16.05 spots/0.5×106 splenocytes in IgG-treated controls; p=0.99; data not shown). Taken together, these data indicated that Notch-1 blockade inhibited effector T cells both quantitatively and functionally.

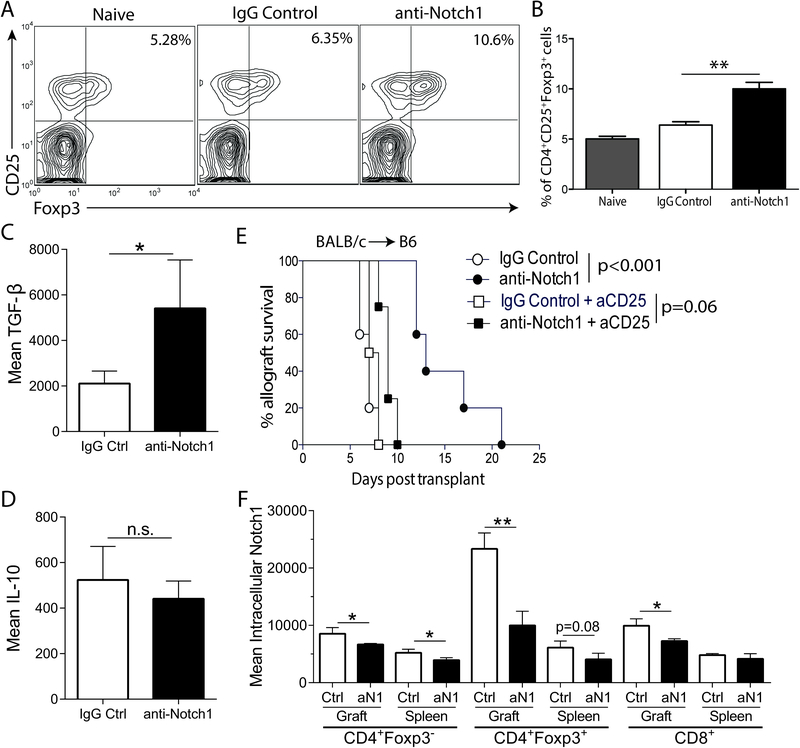

Tregs are essential for prolongation of allograft survival upon Notch-1 blockade

The balance between the effector and regulatory arms of the alloimmune response determines whether the fate of the allograft is rejection or tolerance. We hypothesized that aNotch-1 mediates its effects by enhanced suppression of effector T cells. To test this, we next examined the effect of aNotch-1 on Tregs. First, we found that aNotch-1 treated mice demonstrated a higher percentage of splenic Tregs (CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ cells) compared with control IgG-treated mice on day 7 post-transplantation (Figure 4A and B). To investigate the phenotype of Tregs isolated following aNotch-1 treatment, we examined the expression of co-signaling molecules and intracellular cytokines in intragraft and splenic Tregs from mice 7 days after full-MHC-mismatched cardiac transplantation. We observed a trend of higher expression of LAG3 and CTLA-4 in intragraft and splenic Tregs (Supplemental Figure S3A and B, respectively). Interestingly, we found that intragraft Tregs produced more TGF-β (Figure 4C), while IL-10 expression was not significantly altered (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Prolongation of allograft survival achieved by aNotch-1 is Treg-dependent.

A-B, Percentage of splenic Tregs (CD4+CD25+Foxp3+) was significantly increased in aNotch-1 treated mice compared to controls upon isolation on day 7 post full MHC-mismatch cardiac transplantation (representative flow cytometry plots, pre-gated on CD4+ cells, are shown in panel A). The percentage of Tregs in CD4+ cells on day 7 post-transplantation (mean±SEM; n=3; one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test, **p<0.01). Production of TGF-β (C) and IL-10 (D) by graft-infiltrating Tregs from IgG or aNotch-1-treated mice on day 7 post-transplant (n=4–5 mice per group, *p<0.05 by t test). E, Graft survival in full MHC-mismatch cardiac transplant model with pre-transplant depletion of Tregs with anti-CD25 antibody (day −6 and −1). Pre-transplant depletion of Tregs abrogated the prolonged graft survival. Graft survival in mice treated with combined anti-CD25 and aNotch-1 similar to anti-CD25 and IgG-treated group (MST 9 vs 7.5 days, respectively; n=5 per group). F, Expression of intracellular Notch-1 in splenic or graft-infiltrating CD4+Foxp3− (Tconv), CD4+Foxp3+ (Tregs) or CD8+ T cells from IgG or aNotch-1-treated mice on day 7 post-transplant (n=4–5 mice per group, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, by two sample t-tests with multiple testing correction using Holm-Sidak method; alpha=0.05 and number of t-tests=6).

To study whether Tregs were required for the prolonged allograft survival in aNotch-1-treated mice, we depleted Tregs prior to transplantation using rat anti-mouse CD25 mAb on days −6 and −1 before transplant. Pre-transplant anti-CD25 treatment abolished the significant prolongation of allograft survival previously seen upon Notch-1 blockade (MST 9 (aNotch-1+anti-CD25) vs 7.5 days (IgG+anti-CD25)), suggesting that Tregs are necessary for aNotch-1-mediated survival prolongation (Figure 4E). Next, we asked whether this Treg-dependent prolongation of allograft survival was mediated by central (thymic) or peripheral Tregs. To test this, we performed thymectomy two weeks prior to transplantation. Interestingly, thymectomized mice treated with aNotch-1 displayed a graft survival advantage compared to those treated with IgG, indicating a thymus-independent effect (Supplemental Figure S4A). Further, these mice displayed increased frequency of splenic Tregs compared to IgG-treated controls (Supplemental Figure S4B). These results suggest that aNotch-1 treatment potentiates peripheral Tregs, which then contribute to the prolongation of allograft survival.

Lastly, we confirmed that in vivo aNotch-1 therapy blocked Notch signaling in graft-infiltrating and splenic T cells by evaluating levels of intracellular (activated) Notch-1. We found that Tregs expressed the highest levels of intracellular Notch-1 when compared to Tconv and CD8+ T cells upon transplantation (Figure 4F). Anti-Notch1 treatment significantly decreased intracellular Notch-1 in Tregs and Tconv in both graft and spleen, and in intragraft CD8+ T cells (Figure 4F), indicating that aNotch-1 therapy successfully inhibited downstream Notch-1 signaling on T cells.

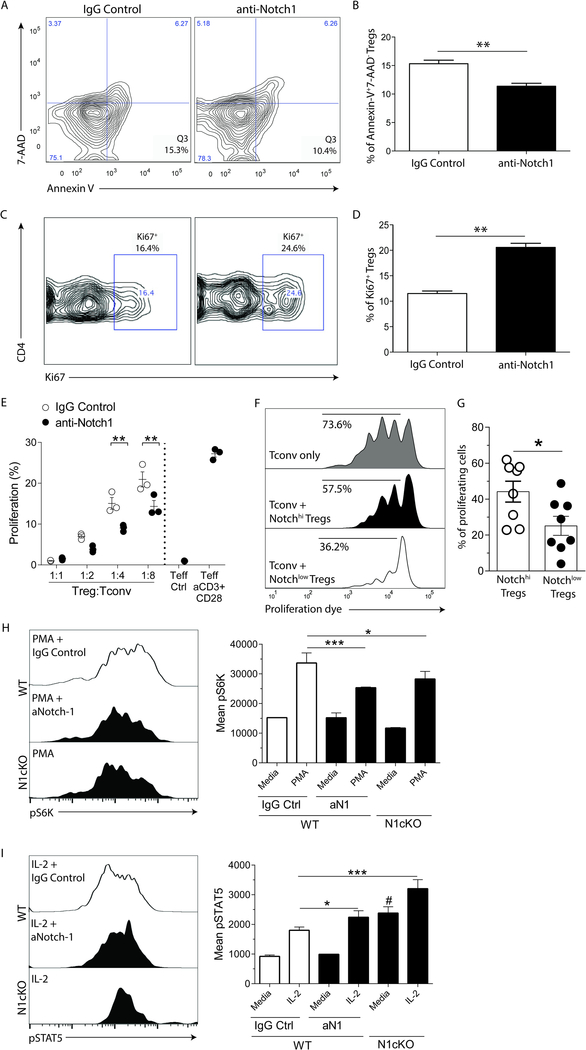

Notch-1 blockade enhances the survival, proliferation and suppressive function of Tregs

We then sought to investigate the mechanisms underlying the increase in the Treg population, and to investigate whether inhibition of Notch-1 altered Treg function. We found that splenic Tregs (CD4+CD25+Foxp3+) isolated from aNotch-1-treated mice on day 7 post-transplant had a significantly lower rate of apoptosis compared to IgG-treated controls (Figure 5A and B). We next investigated the rate of proliferation within the Treg subset using Ki67 staining; indeed, Tregs isolated from aNotch-1-treated mice demonstrated a significantly higher proportion of Ki67+ Tregs compared to those isolated from IgG-treated controls (Figure 5C and D).

Figure 5. Tregs isolated from mice treated with aNotch-1 were less apoptotic and more proliferative, compared with IgG control-treated mice.

A-B, Rates of apoptotic (AnnexinV+7-AAD−) splenic Tregs isolated from mice treated with aNotch-1 on day 7 post-transplantation compared to IgG-treated controls (representative flow cytometry plots are shown (left); t-test, **p<0.01; n=4 per group). C-D, Proportion of proliferating (Ki67+) Tregs isolated from mice treated with aNotch-1 on day 7 post-transplantation compared to IgG-treated controls (representative flow cytometry plots are shown (left); t-test, **p<0.01; n=4 per group). E, Tregs isolated from mice treated with aNotch-1 showed greater suppressive function than those isolated from IgG-treated controls. Tregs were flow-sorted as CD4+Foxp3(GFP+) cells from mice treated with aNotch-1 or control IgG, on day 14 post-cardiac transplantation. They were then incubated in varying ratios (1:1, 1:2, 1:4, 1:8) ex vivo with CD4+Foxp3(GFP−) cells isolated from control-treated mice (Tconv) and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 conjugated beads for 72 hours. Their suppressive function was assessed by CellTrace Violet proliferation dye dilution assay (p values at different ratio of Tconv:Tregs shown, **p<0.01, n=3 per group, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test). F-G, Human Treg suppression assay. Tconv (CD4+CD127+CD25−), Notch-1hiTregs (CD4+CD127−CD25+Notch-1hi), and Notch-1lowTregs (CD4+CD127−CD25+Notch-1low) were flow-sorted from healthy control subjects and co-cultured at different ratios (1:1 to 1:8) with Tconv stained with CellTrace Violet proliferation dye; representative flow cytometry plots of the human Treg suppression assay at a 1:2 Treg:Tconv ratio (F) and the percentage of proliferating cells in suppression assay culture with Notch-1hi vs Notch-1lo Tregs (G; paired t-test, *p<0.05; n=8) are shown. H, Expression of phosphorylated-S6 kinase (pS6K), a marker for activated mTOR pathway, in WT Tregs treated with IgG control or aNotch1 or N1cKO Tregs. PMA stimulation for 30min was used to induce the expression of pS6K, and the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) was obtained by flow cytometry. I, Expression of phosphorylated-STAT5 (pSTAT5) in WT Tregs treated with IgG control or aNotch1 or N1cKO Tregs. IL-2 stimulation (10 ng/ml) for 30min was used to induce the expression of pSTAT5, and the MFI was obtained by flow cytometry. H-I, experiments were performed with a pool of three mice in triplicates, and analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test, *p<0.05, #p<0.001 (compared to WT IgG control), ***p<0.001.

To address whether Tregs from aNotch-1-treated mice had greater suppressive capacity, we examined Treg function using an in vitro suppression assay. Flow-sorted Tregs (CD4+Foxp3+) were incubated with Tconv cells (CD4+Foxp3−) in different Treg:Tconv ratios, and cell proliferation was assessed by a proliferation dye-dilution assay. Tregs isolated from aNotch-1-treated mice suppressed Tconv proliferation more potently compared to those isolated from IgG-treated mice (Figure 5E). Next, to investigate whether the surface expression level of Notch-1 correlates with Treg function in human kidney transplant recipients, we performed an in vitro suppression assay using Tregs flow-sorted according to high or low Notch-1 expression. In accordance with the animal data, Tregs with lower Notch-1 expression exhibited more potent suppressive function (Figure 5F and G). We subsequently investigated molecular pathways potentially responsible for the effects of aNotch1 therapy. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway is known to inhibit Treg differentiation and function 29, 30; it has multiple downstream targets, including the phosphorylation level of S6K-1 (pS6K)31, which induces protein translation and enhances cellular survival and proliferation. We hypothesized that aNotch-1 inhibits the mTOR pathway, thereby enhancing Treg function. We treated WT T cells with PMA/Ionomycin in the presence of aNotch-1 or control IgG. We also isolated cells from Foxp3EGFPCreNotch1fl/fl mice (N1cKO), wherein Notch-1 is specifically deleted within the Treg population (Supplemental Figure S5). Indeed, as shown in Figure 5H, aNotch1-treated or N1cKO Tregs had lower levels of pS6K; no differences were found in Tconv cells. We next investigated the effect of Notch-1 signaling on STAT5, another transcription factor known to support Treg function and differentiation32. In the presence of IL-2, Notch-1 blockade or deficiency increased the phosphorylation of STAT5 in Tregs (Figure 5I). In summary, interruption of Notch-1 signaling enhances Treg survival, proliferation and suppressive functions by inhibiting the mTOR pathway and increasing STAT5 phosphorylation.

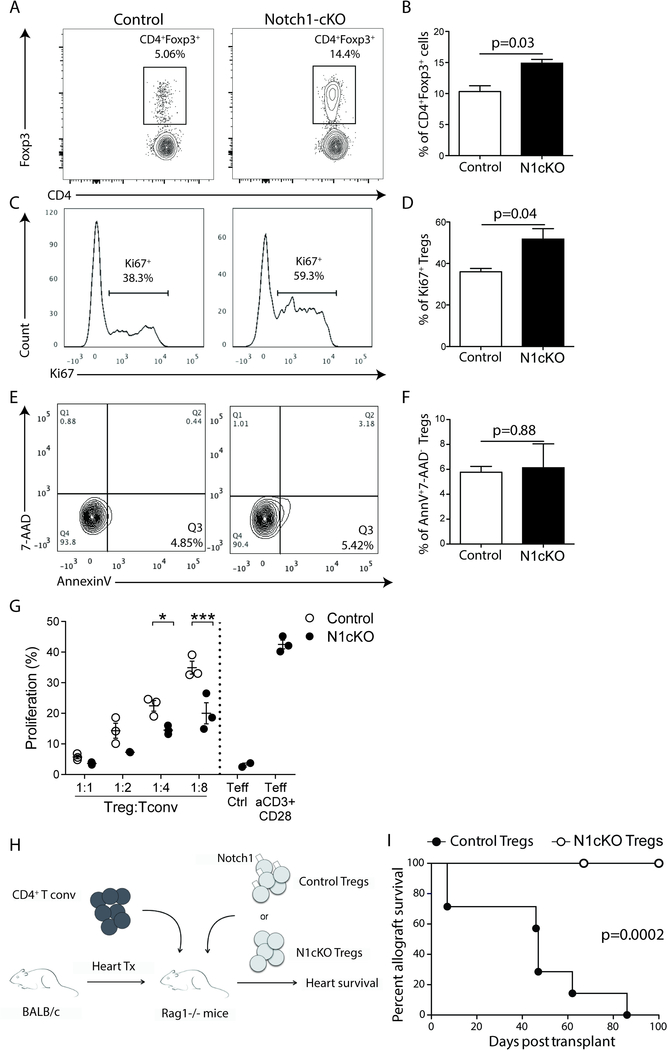

Notch-1 signaling has a Treg-intrinsic effect on Treg proliferation and function

To determine whether these results were due to Treg-intrinsic effects of Notch-1 signaling, we employed Foxp3EGFPCreNotch1fl/fl mice (N1cKO), which allowed efficient, selective deletion of Notch-1 within Tregs. Naïve N1cKO mice showed an increased proportion of Foxp3+ Tregs when compared to Foxp3Cre controls (Figure 6A and B). In addition, a significantly higher proportion of N1cKO Tregs expressed Ki67+ compared to controls, indicating increased proliferation (Figure 6C and D), though we did not observe significant differences in apoptosis between the two groups (Figure 6E and F). Furthermore, N1cKO Tregs exhibited more potent inhibition in an in vitro suppression assay (Figure 6G). Finally, to assess a Treg-intrinsic function of Notch-1 in vivo, we adoptively transferred Tconv and Tregs, isolated from either control or N1cKO mice, into RAG1−/− mice then recipient of a full MHC-mismatch cardiac transplant (Figure 6H). Graft survival in recipients of N1cKO Tregs far exceeded that seen in recipients of control Tregs (Figure 6I; MST >100 vs 47 days; p=0.0002), confirming a Treg-intrinsic effect of Notch-1 signaling on prolongation of allograft survival.

Figure 6. Treg-specific deletion of Notch-1 enhanced Treg survival and suppression function.

A-B, Representative flow cytometry plots and proportion of splenic Tregs (CD4+Foxp3+) isolated from either control mice (Foxp3Cre) or Notch-1 conditional knockout mice (N1cKO; Notch-1f/fFoxp3Cre; t-test, p=0.03; n=3 per group). C-D, Representative flow cytometry plots and proliferation of Tregs isolated from either control mice (Foxp3Cre) or N1cKO mice, as indicated by expression of Ki67 (t-test, p=0.04; n=3 per group). E-F, Representative flow cytometry plots and rates of apoptosis of splenic Tregs (CD4+Foxp3+) isolated from either control mice (Foxp3Cre) or N1cKO mice using the apoptotic markers Annexin V and 7-AAD (t-test, p=0.88, n=3 per group). G, CD4+GFP.Foxp3+ Tregs isolated either from control mice (Foxp3Cre) or N1cKO mice were incubated in varying ratios (1:1, 1:2, 1:4, 1:8) ex vivo with CD4+GFP.Foxp3− (Tconv) isolated from control mice and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 conjugated beads for 72 hours. The suppressive function was measured by the proliferation of Tconv cells using CellTrace Violet dilution (p values at different ratio of Tconv:Tregs shown, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, n=3 per group, two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test). H, Schematic of the transplant model utilized to assess the function of Notch-1 on Tregs in vivo, in which Rag−/− mice received a BALB/c cardiac allograft; on day 1 post-transplant, the mice were injected with 1 ×106 CD4+GFP.Foxp3− cells and either 6.5 ×105 control (Foxp3-Cre) or N1cKO Tregs. I, Graft survival in mice who received N1cKO Tregs compared to that in those received control Tregs (MST >100 vs 47 days; p=0.0002; n=8 & 7, respectively).

aNotch-1 promotes allograft tolerance synergistically with costimulation blockade

We then sought to evaluate whether transient treatment with aNotch-1 could act synergistically with costimulation blockade to promote graft tolerance. Indeed, the administration of single dose CTLA4-Ig on day 2 (sCTLA4-Ig) in conjunction with aNotch-1 on days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 achieved allograft tolerance (allograft survival >100 days) in all mice treated, compared to a median survival of 42 days in mice treated with sCTLA4-Ig alone (p<0.001; Figure 7A). To investigate the underlying mechanism, we analyzed T cell populations in the graft and spleen of mice 21 days post-transplant. We found that splenic CD4+ T conv and CD8+ T cells expressed less CD28 (Figure 7B) and produced less IFN-γ (Figure 7C), while intra-graft CD4+ T conv and CD8+ T cells produced less IL-17 (Figure 7D). Immunophenotypic characterization of the graft-infiltrating Tregs showed significantly higher expression of CTLA-4 and LAG3 (Figure 7E). Interestingly, graft-infiltrating CD4+ T conv and CD8+ T cells also demonstrated upregulation of CTLA-4 (Figure 7F), while LAG3 was upregulated in CD8+ T cells (Figure 7G). To confirm the potentially critical role of the co-inhibitory CTLA-4 pathway in vivo, we treated tolerant mice with three doses of anti-CTLA-4 antibody: indeed, CTLA-4 blockade broke the tolerance and mice promptly rejected the allograft (Figure 7A). Furthermore, to determine whether this tolerance was allospecific, and to investigate the robustness of this response, tolerant mice treated with aNotch-1 and sCTLA4-Ig with initial graft survival exceeding 100 days were subsequently challenged with a second cardiac graft from the same donor strain (BALB/c) or from a third-party strain (CBA) in the absence of any further treatment. Survival of the second BALB/c grafts also exceeded 100 days (n=3), while recipients challenged with a third-party allograft (CBA) rejected their allograft by day 13 (Supplemental Figure S6), indicating that Notch-1 inhibition promotes robust alloantigen-specific tolerance and is a promising novel immune regulatory strategy in transplantation.

Figure 7. Combined aNotch-1 and CTLA-4Ig treatment induces tolerance in a CTLA-4 dependent manner.

Murine recipients of full MHC-mismatch cardiac transplantation received aNotch-1 or IgG control (days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10), combined with single dose CTLA4-Ig (250 μg/mouse, i.p.) given on day 2 post-transplantation. A, Combined therapy significantly prolonged the allograft survival to more than 100 days (filled circle with line), when compared to sCTLA4-Ig with control IgG (open circle, n=5 per group, p<0.001). One group received anti-CTLA-4 antibody on days 61–65 (filled circle with dotted line), which completely abolished the tolerance response induced by aNotch-1+sCTLA-Ig treatment (n=5 per group, p<0.001). B, Expression of CD28 and C, IFN-γ production by splenic CD4+ Tconv or CD8+ T cells on day 21 post-transplant. D, IL-17 production by Tconv isolated from heart allografts on day 21 after transplantation. E, Heatmap representing the expression of relevant markers (e.g. co-stimulatory/co-inhibitory molecules) by graft-infiltrating Tregs on day 21 post-transplant. F, CTLA-4 and G, LAG3 expression by Tconv, Tregs or CD8+ T cells isolated from cardiac allografts on day 21 post-transplant. A-F, n=4–5 mice per group, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, analyzed by t-test (D) or two-sample t-tests with multiple testing correction using Holm-Sidak method; alpha=0.05, number of t-tests=2 (B and C), 3 (F and G).

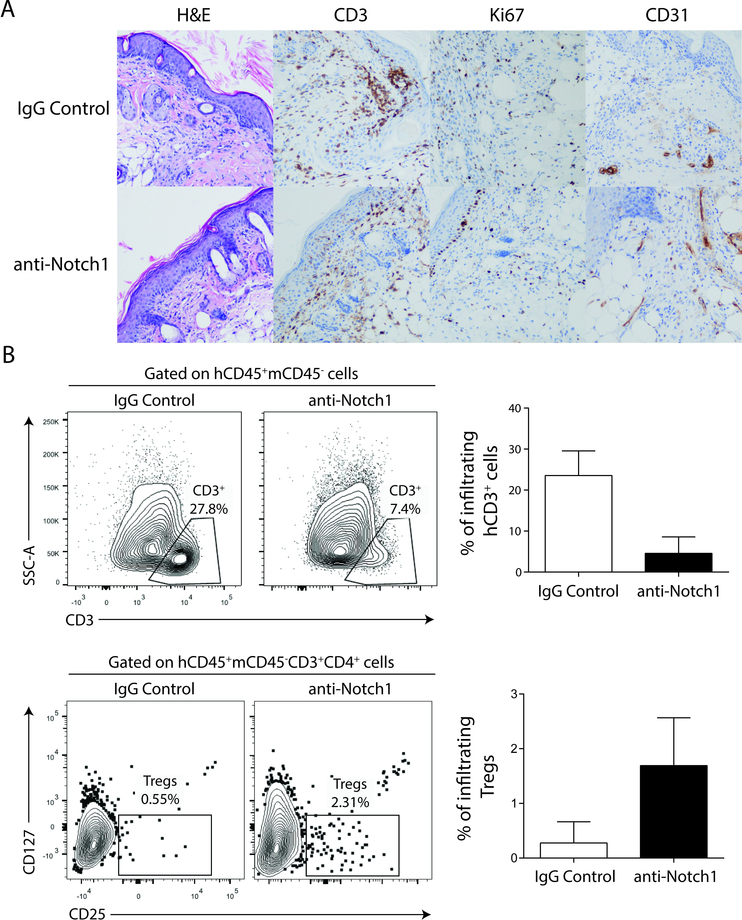

aNotch-1 treatment improved graft histology and ameliorated immune cell infiltration in a humanized skin transplant model

Finally, to explore the translational potential of Notch-1 blockade, we tested aNotch-1 treatment in a humanized skin transplant model. In this model, NSG mice (Nod-scid-gamma null mice33) were reconstituted with human CD34+ pluripotent hematopoietic cells, with hCD45+ cells constituting approximately 20% of peripheral blood cells (Supplemental Figure S7). Human immune cell-reconstituted mice were then transplanted with full-thickness human skin grafts and treated with either control IgG or aNotch-1 (days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10). Histological analysis revealed a reduced CD3+ Ki67+ infiltrate, in addition to evidence of enhanced vascularization (increased expression of CD31+ cells) to support engraftment in the aNotch-1-treated mice compared to IgG-treated controls (Figure 8A). Enumeration and characterization of CD3+ cells within the skin grafts confirmed reduced intragraft T cell infiltration in aNotch-1-treated mice but demonstrated a higher percentage of infiltrating Tregs than seen in IgG-treated controls (Figure 8B). In addition, secretion of the pro-inflammatory serum cytokines IFN-γ and IL-6 was significantly lower in aNotch-1-treated mice compared to controls (95±36 vs 355.25±112.5 pg/ml and 101±26 vs 220.5±52 pg/ml, mean±S.D. respectively). Taken together, aNotch-1 treatment modified the alloimmune response in this model, providing evidence for the potential translational relevance of this strategy.

Figure 8. Anti-Notch-1 treatment reduced T cell graft infiltration in a humanized skin transplant model.

NSG mice reconstituted with human CD34+ hematopoietic cells (human chimerism rate ~20% in peripheral blood) were transplanted with full thickness human skin grafts (carrying different HLA alleles from CD34+ cell donor). Recipients were treated with aNotch-1 or control IgG (5 mg/kg, i.p., days 0, 2, 4, 6 and 8) and analyzed on day 22 post-transplant. A, Allograft histology on day 22 post-transplant, showing more abundant CD3+ cellular infiltrates and proliferating (Ki67+) cells in skin transplants isolated from IgG-treated controls compared with aNotch-1-treated mice, while grafts isolated from aNotch-1 treated mice had greater vascularization as evident by CD31+ staining. B, Skin allograft-infiltrating human T cells and Tregs were analyzed as hCD45+mCD45−hCD3+ (top), and hCD45+mCD45−hCD3+hCD4+hCD127−hCD25+ cells (bottom), respectively. Grafts isolated from aNotch-1-treated mice showed less human T cell infiltration, but a greater proportion of Tregs.

DISCUSSION

Herein, we report that peri-transplant inhibition of Notch-1 signalling, achieved by use of a fully human IgG antibody, successfully prolonged graft survival in the stringent cardiac and lung transplant models, and in a humanized full-thickness skin transplant model, in the absence of significant systemic toxicity. These data support the efficacy of aNotch-1 as a potent modulator of the alloimmune response.

Although the modern era of immunosuppression has achieved improved early graft survival, we have been singularly unsuccessful in improving longer-term outcomes. Most immunosuppressive agents in clinical use, including steroids, calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) and anti-metabolites, induce global inhibition of the immune system, affecting both the effector and regulatory components3, and fail to achieve a favorable, pro-regulatory milieu. Moreover, the use of CNIs is not without significant adverse sequelae, including renal toxicity and an increased risk of development of both infections and malignancies. One of the striking findings upon Notch-1 blockade in our models, therefore, was the simultaneous decrease in effector T cells and increase in both proportion and function of Tregs. Such an immunomodulatory effect is of vital importance for the improvement of long-term graft survival and minimization of conventional maintenance immunosuppression. Though preliminary work suggests that adoptive transfer of ex vivo-expanded natural Tregs is effective in controlling rejection34 and preventing GVHD35, we believe that promoting regulation through blockade of Notch-1 has many advantages over cellular therapy, including the lack of requirement for ex vivo Treg expansion and potential issues of Treg instability.

The potential role of Notch signaling in Tregs was first highlighted by the demonstration of significant upregulation of deltex, a positive regulator of the Notch pathway, in CD4+ CD25+ cells compared with CD4+CD25− cells, prior to the identification of Foxp3 as a Treg marker36. Subsequently, overexpression of Notch-3 on T cells was shown to lead to accumulation of Tregs in the thymus and periphery37. In another study, overexpression of Jagged2 on hematopoietic progenitor cells led to enhanced Treg expansion and protection against autoimmune diabetes38. In a mouse model of GVHD, inhibition of global Notch signaling has been shown to result in accumulation of pre-existing nTregs 39, although the mechanisms underlying this were not fully explored. The importance of Notch-1 signaling in Treg homeostasis was further supported by Notch-1 conditional knockout mice in a GVHD model20.

Our data indicated that the expansion of Tregs was due both to decreased peripheral Treg apoptosis and increased Treg proliferation, independent of the thymus. Our Treg apoptosis data contrasts with a study by Perumalsamy et al40 that showed Notch-1 signaling protected Tregs from in vitro apoptosis induced by the absence of IL-2; however, the susceptibility of Notch-1−/− Tregs to apoptosis was reversed by addition of exogenous IL-2 in vitro, and although Notch-1−/− Tregs were also shown to have impaired in vivo survival in congenic hosts, these Tregs were activated in vitro and were not subjected to an antigenic challenge in vivo, which may account for the differences seen40.

In our study, Tregs were critical to the enhanced graft survival achieved with Notch-1 blockade, as depletion of Tregs pre-transplant in mice subsequently treated with aNotch-1 abrogated the survival advantage previously seen with aNotch-1 alone; these data were supported by the achievement of long-term graft survival following the adoptive transfer of N1cKO Tregs in the Rag1−/− recipients, which further provided evidence of a Treg-intrinsic role for Notch-1 signaling. In vitro, Tregs isolated from aNotch-1-treated mice were demonstrated to be more suppressive than those isolated from IgG-treated controls; investigation of the mechanisms underlying this revealed that inhibition or selective deletion of Notch-1 increased phosphorylation of STAT5 and inhibited the mTOR signaling pathway, evidenced by the reduced phosphorylation of S6K. These combined effects enhanced Treg survival, proliferation and suppressive functions. Shan et al demonstrated an interplay between mTOR and STAT5 signaling in which mTOR inhibition leads to upregulation in phospho-STAT5 levels, leading to increased Treg function41. Notch signaling has been previously shown to activate the kinase complex mTORC2 and its downstream AKT signaling via the noncanonical pathway40, 42, 43. Indeed, using Notch-1-overexpressing Tregs, Charbonnier et al had shown greater activation of mTORC2 and AKT, disrupting Treg stability20. They also observed lower expression of Treg cell markers in Notch-1-overexpressing Tregs such as Foxp3, CTLA-4 and CD25, thought to be mediated by the canonical pathway20. Using a complementary approach to our Notch-1 blocking antibody, we demonstrated higher expression of the coinhibitory molecule CTLA-4 (CD152) on graft-infiltrating Tregs upon Notch-1 deletion. CTLA-4 is constitutively expressed by Tregs, and is central to their normal homeostasis44, 45 and suppressive function, shown to be due to both cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic mechanisms46, 47. Overall, Notch-1 blockade is capable of promoting and enhancing Tregs both through mTOR pathway inhibition, increased STAT5 phosphorylation and upregulation of co-inhibitory pathways such as CTLA-4.

Antigen-specific tolerance is the holy grail of transplantation. We demonstrated that transient Notch-1 inhibition combined with a single dose of costimulation blockade (CTLA4-Ig) achieved long-term graft survival. While CTLA4-Ig has been shown to be highly effective in prolonging allograft survival in multiple rodent models48, there are concerns about its deleterious effects on the Treg population, thought due to its competitive inhibition of B7–1/2, which, in addition to inhibiting CD28, also blocks the CTLA-4/B7 interaction, and, consequently, inhibitory cell-intrinsic signaling. Indeed, use of Belatacept, a fusion protein composed of the extracellular domain of CTLA-4 receptor and the Fc fragment of human IgG1 immunoglobulin, in human transplant recipients has not been without complication, with higher rates of severe acute rejection reported in the initial trials49 thought to be partially related to adverse effects on the Treg population 50. However, given the significant survival advantage seen in our combination-treated mice, it is possible that the beneficial effects of Notch-1 blockade on the Treg population, achieved by both inhibition of mTOR signaling and upregulation of CTLA-4, have superseded the possible disadvantage conferred by sCTLA4-Ig alone, and suggests that this may be a promising therapeutic combination.

In summary, Notch signaling is critical for the fine-tuning of the immune response. Our data demonstrate a critical role of Notch-1 in Treg-mediated alloimmunity and identify a promising target for manipulation of the T cell response and promotion of immune regulation. Furthermore, the availability of a selective, human Notch-1 antibody, which requires only transient use to achieve long-lasting results, suggests that this approach could be efficiently translated into novel strategies of immunosuppression in solid organ transplantation in humans.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

What Is New?

Notch-1 is a potent novel target to modulate allo-immunity.

Blockade of Notch-1 signaling prolongs allograft survival and enhances tolerance in animal transplant models in a regulatory T cell-dependent manner.

What Are The Clinical Implications?

Most immunosuppressive agents in clinical use induce global inhibition of the immune system, including suppression of beneficial Tregs.

Our data suggest that the Notch-1 signaling pathway is a potential clinically relevant target to control effector function and promote immune regulation after transplantation.

Tipping the balance towards regulation may minimize the need for higher doses of immunosuppressive drugs, reducing toxicity and improving long-term outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Xiang Xiao for helpful discussions and Deneen Kozoriz at the BWH flow cytometry core facility for her technical help in cell sorting.

Sources of Funding

C.N.M. was supported by an American Society of Transplantation Basic Science Fellowship Grant, N.M. is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH, T32DK007527), T.A.C is supported by NIH (R01AI11569), L.V.R. was supported by American Heart Association Career Development Award (12FTF12070328) and N.N. was supported by NIH (R56AI101150).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ and Port FK. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1725–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Zoghby ZM, Stegall MD, Lager DJ, Kremers WK, Amer H, Gloor JM and Cosio FG. Identifying specific causes of kidney allograft loss. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:527–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camirand G and Riella LV. Treg-Centric View of Immunosuppressive Drugs in Transplantation: A Balancing Act. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:601–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nankivell BJ, Borrows RJ, Fung CL, O’Connell PJ, Allen RD and Chapman JR. The natural history of chronic allograft nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2326–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lechler RI, Garden OA and Turka LA. The complementary roles of deletion and regulation in transplantation tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng XX, Sanchez-Fueyo A, Domenig C and Strom TB. The balance of deletion and regulation in allograft tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2003;196:75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radtke F, MacDonald HR and Tacchini-Cottier F. Regulation of innate and adaptive immunity by Notch. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:427–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kopan R and Ilagan MXG. The Canonical Notch Signaling Pathway: Unfolding the Activation Mechanism. Cell. 2009;137:216–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radtke F, Wilson A, Stark G, Bauer M, van Meerwijk J, MacDonald HR and Aguet M. Deficient T Cell Fate Specification in Mice with an Induced Inactivation of Notch1. Immunity. 1999;10:547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pui JC, Allman D, Xu L, DeRocco S, Karnell FG, Bakkour S, Lee JY, Kadesch T, Hardy RR, Aster JC and Pear WS. Notch1 Expression in Early Lymphopoiesis Influences B versus T Lineage Determination. Immunity. 1999;11:299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amsen D, Blander JM, Lee GR, Tanigaki K, Honjo T and Flavell RA. Instruction of Distinct CD4 T Helper Cell Fates by Different Notch Ligands on Antigen-Presenting Cells. Cell. 2004;117:515–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tu L, Fang TC, Artis D, Shestova O, Pross SE, Maillard I and Pear WS. Notch signaling is an important regulator of type 2 immunity. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1037–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riella LV, Ueno T, Batal I, De Serres SA, Bassil R, Elyaman W, Yagita H, Medina-Pestana JO, Chandraker A and Najafian N. Blockade of Notch Ligand Delta1 Promotes Allograft Survival by Inhibiting Alloreactive Th1 Cells and Cytotoxic T Cell Generation. J Immunol. 2011;187:4629–4638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riella LV, Yang J, Chock S, Safa K, Magee CN, Vanguri V, Elyaman W, Lahoud Y, Yagita H, Abdi R, Najafian N, Medina-Pestana JO and Chandraker A. Jagged2-signaling promotes IL-6-dependent transplant rejection. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:1449–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran IT, Sandy AR, Carulli AJ, Ebens C, Chung J, Shan GT, Radojcic V, Friedman A, Gridley T, Shelton A, Reddy P, Samuelson LC, Yan M, Siebel CW and Maillard I. Blockade of individual Notch ligands and receptors controls graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1590–1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radojcic V, Paz K, Chung J, Du J, Perkey ET, Flynn R, Ivcevic S, Zaiken M, Friedman A, Yan M, Pletneva MA, Sarantopoulos S, Siebel CW, Blazar BR and Maillard I. Notch signaling mediated by Delta-like ligands 1 and 4 controls the pathogenesis of chronic GVHD in mice. Blood. 2018;132:2188–2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood S, Feng J, Chung J, Radojcic V, Sandy-Sloat AR, Friedman A, Shelton A, Yan M, Siebel CW, Bishop DK and Maillard I. Transient Blockade of Delta-like Notch Ligands Prevents Allograft Rejection Mediated by Cellular and Humoral Mechanisms in a Mouse Model of Heart Transplantation. J Immunol. 2015;194:2899–2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Sandy AR, Wang J, Radojcic V, Shan GT, Tran IT, Friedman A, Kato K, He S, Cui S, Hexner E, Frank DM, Emerson SG, Pear WS and Maillard I. Notch signaling is a critical regulator of allogeneic CD4+ T-cell responses mediating graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2011;117:299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandy AR, Stoolman J, Malott K, Pongtornpipat P, Segal BM and Maillard I. Notch Signaling Regulates T Cell Accumulation and Function in the Central Nervous System during Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2013;191:1606–1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charbonnier L-M, Wang S, Georgiev P, Sefik E and Chatila TA. Control of peripheral tolerance by regulatory T cell–intrinsic Notch signaling. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:1162–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Es JH, van Gijn ME, Riccio O, van den Born M, Vooijs M, Begthel H, Cozijnsen M, Robine S, Winton DJ, Radtke F and Clevers H. Notch/γ-secretase inhibition turns proliferative cells in intestinal crypts and adenomas into goblet cells. Nature. 2005;435:959–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Williams LM, Dooley JL, Farr AG and Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity. 2005;22:329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Y, Cain-Hom C, Choy L, Hagenbeek TJ, de Leon GP, Chen Y, Finkle D, Venook R, Wu X, Ridgway J, Schahin-Reed D, Dow GJ, Shelton A, Stawicki S, Watts RJ, Zhang J, Choy R, Howard P, Kadyk L, Yan M, Zha J, Callahan CA, Hymowitz SG and Siebel CW. Therapeutic antibody targeting of individual Notch receptors. Nature. 2010;464:1052–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corry RJ, Winn HJ and Russell PS. Primarily vascularized allografts of hearts in mice. The role of H-2D, H-2K, and non-H-2 antigens in rejection. Transplantation. 1973;16:343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Perrot M, Young K, Imai Y, Liu M, Waddell TK, Fischer S, Zhang L and Keshavjee S. Recipient T cells mediate reperfusion injury after lung transplantation in the rat. J Immunol. 2003;171:4995–5002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lurie D, Cicciarelli JC and Myers WL. Thymectomy in the adult mouse: a new approach. Lab Anim Sci. 1977;27:235–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radtke F, Fasnacht N and MacDonald HR. Notch Signaling in the Immune System. Immunity. 2010;32:14–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu L, Aster JC, Blacklow SC, Lake R, Artavanis-Tsakonas S and Griffin JD. MAML1, a human homologue of Drosophila mastermind, is a transcriptional co-activator for NOTCH receptors. Nat Genet. 2000;26:484–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sauer S, Bruno L, Hertweck A, Finlay D, Leleu M, Spivakov M, Knight ZA, Cobb BS, Cantrell D, O’Connor E, Shokat KM, Fisher AG and Merkenschlager M. T cell receptor signaling controls Foxp3 expression via PI3K, Akt, and mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7797–7802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun IH, Oh MH, Zhao L, Patel CH, Arwood ML, Xu W, Tam AJ, Blosser RL, Wen J and Powell JD. mTOR Complex 1 Signaling Regulates the Generation and Function of Central and Effector Foxp3(+) Regulatory T Cells. J Immunol. 2018;201:481–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng Y, Collins SL, Lutz MA, Allen AN, Kole TP, Zarek PE and Powell JD. A role for mammalian target of rapamycin in regulating T cell activation versus anergy. J Immunol. 2007;178:2163–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burchill MA, Yang J, Vogtenhuber C, Blazar BR and Farrar MA. IL-2 receptor beta-dependent STAT5 activation is required for the development of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:280–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shultz LD, Lyons BL, Burzenski LM, Gott B, Chen X, Chaleff S, Kotb M, Gillies SD, King M, Mangada J, Greiner DL and Handgretinger R. Human lymphoid and myeloid cell development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2R gamma null mice engrafted with mobilized human hemopoietic stem cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:6477–6489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng SG, Meng L, Wang JH, Watanabe M, Barr ML, Cramer DV, Gray JD and Horwitz DA. Transfer of regulatory T cells generated ex vivo modifies graft rejection through induction of tolerogenic CD4+CD25+ cells in the recipient. Int Immunol. 2006;18:279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Ianni M, Falzetti F, Carotti A, Terenzi A, Castellino F, Bonifacio E, Del Papa B, Zei T, Ostini RI, Cecchini D, Aloisi T, Perruccio K, Ruggeri L, Balucani C, Pierini A, Sportoletti P, Aristei C, Falini B, Reisner Y, Velardi A, Aversa F and Martelli MF. Tregs prevent GVHD and promote immune reconstitution in HLA-haploidentical transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:3921–3928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ng WF, Duggan PJ, Ponchel F, Matarese G, Lombardi G, Edwards AD, Isaacs JD and Lechler RI. Human CD4(+)CD25(+) cells: a naturally occurring population of regulatory T cells. Blood. 2001;98:2736–2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anastasi E, Campese AF, Bellavia D, Bulotta A, Balestri A, Pascucci M, Checquolo S, Gradini R, Lendahl U, Frati L, Gulino A, Di Mario U and Screpanti I. Expression of activated Notch3 in transgenic mice enhances generation of T regulatory cells and protects against experimental autoimmune diabetes. J Immunol. 2003;171:4504–4511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kared H, Adle-Biassette H, Fois E, Masson A, Bach JF, Chatenoud L, Schneider E and Zavala F. Jagged2-expressing hematopoietic progenitors promote regulatory T cell expansion in the periphery through notch signaling. Immunity. 2006;25:823–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandy AR, Chung J, Toubai T, Shan GT, Tran IT, Friedman A, Blackwell TS, Reddy P, King PD and Maillard I. T Cell-Specific Notch Inhibition Blocks Graft-versus-Host Disease by Inducing a Hyporesponsive Program in Alloreactive CD4+ and CD8+ T Cells. J Immunol. 2013;190:5818–5828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perumalsamy LR, Marcel N, Kulkarni S, Radtke F and Sarin A. Distinct spatial and molecular features of notch pathway assembly in regulatory T cells. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shan J, Feng L, Sun G, Chen P, Zhou Y, Xia M, Li H and Li Y. Interplay between mTOR and STAT5 signaling modulates the balance between regulatory and effective T cells. Immunobiology. 2015;220:510–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perumalsamy LR, Nagala M, Banerjee P and Sarin A. A hierarchical cascade activated by non-canonical Notch signaling and the mTOR-Rictor complex regulates neglect-induced death in mammalian cells. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:879–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee K, Nam KT, Cho SH, Gudapati P, Hwang Y, Park DS, Potter R, Chen J, Volanakis E and Boothby M. Vital roles of mTOR complex 2 in Notch-driven thymocyte differentiation and leukemia. J Exp Med. 2012;209:713–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bour-Jordan H, Esensten JH, Martinez-Llordella M, Penaranda C, Stumpf M and Bluestone JA. Intrinsic and extrinsic control of peripheral T-cell tolerance by costimulatory molecules of the CD28/ B7 family. Immunol Rev. 2011;241:180–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Read S, Greenwald R, Izcue A, Robinson N, Mandelbrot D, Francisco L, Sharpe AH and Powrie F. Blockade of CTLA-4 on CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells abrogates their function in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;177:4376–4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poirier N, Azimzadeh AM, Zhang T, Dilek N, Mary C, Nguyen B, Tillou X, Wu G, Reneaudin K, Hervouet J, Martinet B, Coulon F, Allain-Launay E, Karam G, Soulillou JP, Pierson RN 3rd, Blancho G and Vanhove B. Inducing CTLA-4-dependent immune regulation by selective CD28 blockade promotes regulatory T cells in organ transplantation. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:17ra10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wing K, Onishi Y, Prieto-Martin P, Yamaguchi T, Miyara M, Fehervari Z, Nomura T and Sakaguchi S. CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science. 2008;322:271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baliga P, Chavin KD, Qin L, Woodward J, Lin J, Linsley PS and Bromberg JS. CTLA4Ig prolongs allograft survival while suppressing cell-mediated immunity. Transplantation. 1994;58:1082–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vincenti F, Charpentier B, Vanrenterghem Y, Rostaing L, Bresnahan B, Darji P, Massari P, Mondragon-Ramirez GA, Agarwal M, Di Russo G, Lin CS, Garg P and Larsen CP. A phase III study of belatacept-based immunosuppression regimens versus cyclosporine in renal transplant recipients (BENEFIT study). Am J Transplant. 2010;10:535–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riella LV, Liu T, Yang J, Chock S, Shimizu T, Mfarrej B, Batal I, Xiao X, Sayegh MH and Chandraker A. Deleterious effect of CTLA4-Ig on a Treg-dependent transplant model. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:846–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.