Abstract

Background

Paraesophageal hernias (PEH) tend to occur in elderly patients and the assumed higher morbidity of PEH repair may dissuade clinicians from seeking a surgical solution. On the other hand, the mortality rate for emergency repairs shows a sevenfold increase compared to elective repairs. This analysis evaluates the complication rates after elective PEH repair in patients 80 years and older in comparison with younger patients.

Methods

In total, 3209 patients with PEH were recorded in the Herniamed Registry between September 1, 2009 and January 5, 2018. Using propensity score matching, 360 matched pairs were formed for comparative analysis of general, intraoperative, and postoperative complication rates in both groups.

Results

Our analysis revealed a disadvantage in general complications (6.7% vs. 14.2%; p = 0.002) for patients ≥ 80 years old. No significant differences were found between the two groups for intraoperative (4.7% vs. 5.8%, p = 0.627) and postoperative complications (2.2% vs. 2.8%, p = 0.815) or for complication-related reoperations (1.7% vs. 2.2%, p = 0.791).

Conclusions

Despite a higher risk of general complications, PEH repair in octogenarians is not in itself associated with increased rates of intraoperative and postoperative complications or associated reoperations. Therefore, PEH repair can be safely offered to elderly patients with symptomatic PEH, if general medical risk factors are controlled.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00464-018-06619-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Paraesophageal hernia repair, Complications, Elderly patients, Propensity score-based, Matched-pair analysis

Hiatal hernias are divided into types I–IV, of which approximately 5–15% are paraesophageal hernias (PEH) (types II–IV) [1]. PEH is defined as herniation of the stomach and/or other viscera through a dilated hiatal aperture alongside the esophagus [1, 2]. These hernias tend to be found more frequently in elderly women, although adults of any sex and age may be affected [3]. Dysphagia, vomiting, and regurgitation, often associated with retrosternal pain, are typical symptoms [3]. Pharmacological treatment is often unsatisfactory since PEH symptoms are mostly related to the mechanical effects of the hernia.

The annual incidence of acute symptoms in patients with PEH ranges between 0.7 and 7% [4, 5]. Emergency repairs of PEH are associated with a sevenfold increase in mortality compared with elective repairs [6]. Several studies showed that elective laparoscopic PEH repair has a low morbidity resulting in significantly improved quality of life [3, 7–11]. Although elective PEH repair may be used increasingly in older patients [12], the assumed higher perioperative morbidity in elderly patients may dissuade clinicians from seeking a surgical solution.

However, data on perioperative outcomes of elective PEH repair in octogenarians or older patients are sparse. One study analyzing short-term outcomes associated with PEH repair in patients aged 80 years and older revealed higher rates of minor morbidity, but no significant differences in mortality or major morbidity rates compared to younger patients [11].

In this registry-based, matched-pair analysis, intraoperative, postoperative, and general complication rates after elective PEH repair in patients ≥ 80 years were assessed and compared to younger patients.

Methods

The Herniamed Registry is a multicenter, internet-based hernia registry [13] with 644 participating hospitals and surgeons in private practice (Herniamed Study Group) in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland (status: January 5, 2018) who have shared data on their patients undergoing routine hernia surgery. All patients signed an informed consent form agreeing to participate. As part of the information provided to patients regarding participation in the Herniamed Quality Assurance Study and signing the informed consent declaration, all patients were informed that the treating hospital or medical practice should be informed about any problem occurring after the operation and that the patient should have a clinical examination if needed. All postoperative complications occurring up to 30 days after surgery are recorded.

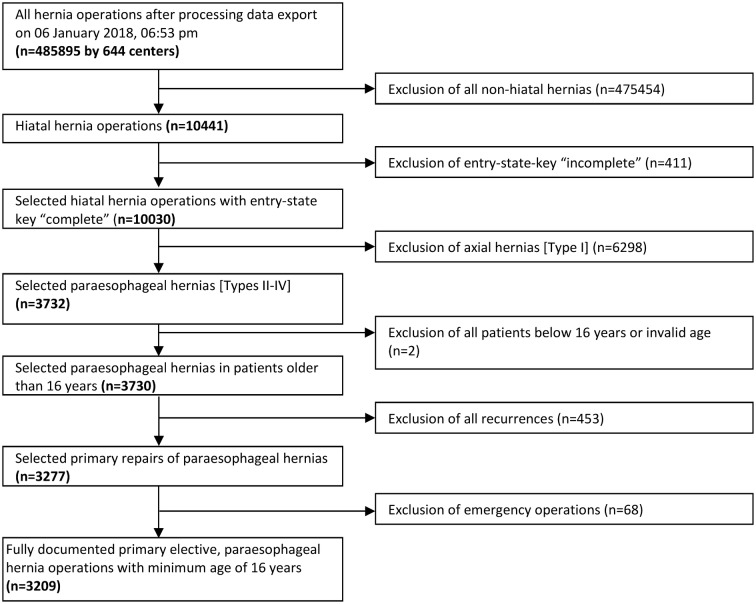

The current analysis compares the prospective data gathered on PEH repairs in octogenarians (≥ 80 years) and younger patients (< 80 years) between September 1, 2009 and January 5, 2018 using a matched-pair analysis. The main inclusion criteria were hiatal hernia operation, complete entry state, paraesophageal hernia (types II–IV), minimum age of 16 years, primary operation, and no emergency repair. In total, 3209 patients were enrolled (Fig. 1). Pairwise propensity score (PS) matching analysis was performed for these 3209 patients to obtain homogeneous comparison groups.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient inclusion

The data collected were age, body mass index (BMI), type of fundoplication, type of hiatal hernia, type of hiatal repair, American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) status, and gender.

The following risk factors were assessed as possible risk factors for an adverse outcome: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus, aortic aneurysm, immunosuppression, steroids, smoking, coagulation disorder, or antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy. All analyses were performed with the software SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and intentionally calculated to a full significance level of 5%, with the exception of post hoc analyses for single general complications. Here, adjustment for multiple testing was made using a Bonferroni correction (factor 16).

Analogous to previous registry-based analyses [14], intraoperative complications (bleeding, injury to esophagus, bowel, spleen, stomach, or liver), postoperative complications (esophageal perforation, gastric perforation, bleeding, infection, wound healing disorder, or ileus), overall complications, and complication-related reoperations were compared between age groups using, first of all, PS matching. Matched samples were analyzed with McNemar’s test. Outcomes are given as the non-diagonal elements of the 2 × 2 frequency table, which represent differences in the matched samples, the corresponding p-values, and the odds ratio (OR) estimates for matched samples. PS matching was performed using greedy algorithm and a caliper of 0.1 standard deviations. The variables used for matching were sex (male/female), type of fundoplication, BMI (kg/m2), hernia type (II, III, IV), risk factors (COPD, diabetes, aortic aneurysm, immunosuppression, steroids, smoking, coagulation disorder, anticoagulants, antiplatelet therapy), and ASA classification (I, II, III, IV). The balance of the matched sample was checked using standardized differences (also given for the original sample) that should not exceed 10% (< 0.1) after creating matched pairs. For pairwise comparison of matching parameters between age groups (for presenting the differences between the original samples), χ2 tests and t tests (Satterthwaite) were performed for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Furthermore, loess regression was performed to visualize the unadjusted relationship between age (years) and binary complication rates.

Results

Out of the 3209 patients with PEH repair, 381 (11.9%) were aged ≥ 80 years. The vast majority of the repairs were done laparoscopically in both groups, at 93.8% (< 80 years) and 91.4% (≥ 80 years), respectively.

Unadjusted analysis before matching

When comparing the frequency distribution of the different matching variables, significant differences were found. The BMI in patients ≥ 80 years old was significantly lower compared to the BMI of younger patients (mean 26.6 ± 4.5 vs. 29.0 ± 5.0; p < 0.001). Patients ≥ 80 years had significantly fewer fundoplications, larger hernias, a higher ASA score, more risk factors, and were predominately female (Table 1).

Table 1.

Unadjusted analysis for the matching variables between the two age groups

| Age | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 80 Years | ≥ 80 Years | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Fundoplication | |||||

| Fundophrenicopexy | 517 | 18.28 | 113 | 29.66 | < 0.001 |

| Nissen fundoplication | 973 | 34.41 | 110 | 28.87 | |

| Toupet fundoplication | 1044 | 36.92 | 116 | 30.45 | |

| Other | 294 | 10.40 | 42 | 11.02 | |

| Access | |||||

| Laparoscopy | 2653 | 93.81 | 348 | 91.34 | 0.075 |

| Open | 175 | 6.19 | 33 | 8.66 | |

| Type of hernia | |||||

| Mixed | 726 | 25.67 | 55 | 14.44 | < 0.001 |

| Paraesophageal | 845 | 29.88 | 74 | 19.42 | |

| Up-side-down stomach | 1257 | 44.45 | 252 | 66.14 | |

| Hiatal repair | |||||

| Other | 29 | 1.03 | 5 | 1.31 | 0.138 |

| Suture only | 1793 | 63.40 | 220 | 57.74 | |

| Suture and mesh | 967 | 34.19 | 152 | 39.90 | |

| Mesh | 39 | 1.38 | 4 | 1.05 | |

| ASA | |||||

| I | 291 | 10.29 | 8 | 2.10 | < 0.001 |

| II | 1654 | 58.49 | 120 | 31.50 | |

| III/IV | 883 | 31.22 | 253 | 66.40 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 947 | 33.49 | 86 | 22.57 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 1881 | 66.51 | 295 | 77.43 | |

| Risk factors | |||||

| Overall | |||||

| Yes | 904 | 31.97 | 166 | 43.57 | < 0.001 |

| No | 1924 | 68.03 | 215 | 56.43 | |

| COPD | |||||

| Yes | 384 | 13.58 | 81 | 21.26 | < 0.001 |

| No | 2444 | 86.42 | 300 | 78.74 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||

| Yes | 204 | 7.21 | 41 | 10.76 | 0.018 |

| No | 2624 | 92.79 | 340 | 89.24 | |

| Aortic aneurysm | |||||

| Yes | 16 | 0.57 | 3 | 0.79 | 0.486 |

| No | 2812 | 99.43 | 378 | 99.21 | |

| Immunosuppression | |||||

| Yes | 33 | 1.17 | 4 | 1.05 | 1.000 |

| No | 2795 | 98.83 | 377 | 98.95 | |

| Steroids | |||||

| Yes | 62 | 2.19 | 15 | 3.94 | 0.048 |

| No | 2766 | 97.81 | 366 | 96.06 | |

| Smoking | |||||

| Yes | 191 | 6.75 | 5 | 1.31 | < 0.001 |

| No | 2637 | 93.25 | 376 | 98.69 | |

| Coagulation disorder | |||||

| Yes | 48 | 1.70 | 15 | 3.94 | 0.009 |

| No | 2780 | 98.30 | 366 | 96.06 | |

| Antiplatelet therapy | |||||

| Yes | 224 | 7.92 | 72 | 18.90 | < 0.001 |

| No | 2604 | 92.08 | 309 | 81.10 | |

| Anticoagulation | |||||

| Yes | 47 | 1.66 | 18 | 4.72 | < 0.001 |

| No | 2781 | 98.34 | 363 | 95.28 | |

ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists status, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Standardized differences after propensity score matching

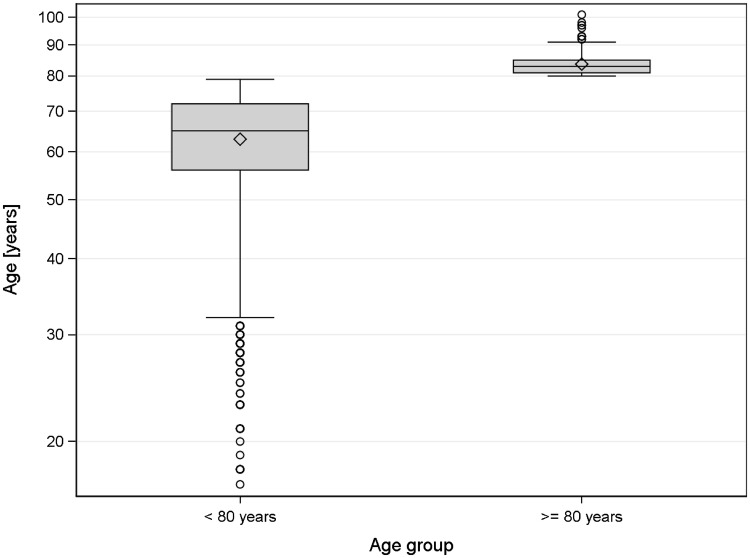

Matching was successfully applied for 360 patients ≥ 80 years (94.5%). The group < 80 years had a mean age of 68.2 years (SD 9.67), whereas the group ≥ 80 years had a mean age of 83.6 years (SD 3.21) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Age distribution within the age groups (after matching)

Table 2 shows the distribution after matching and the standardized differences in the categorical matching variables before (original sample) and after matching (matched sample). All the matching variables show a difference of less than 10%, providing a good balance of those variables in the matched sample. This also holds for BMI, which is 27.0 ± 4.4 and 26.8 ± 4.5 in patients < 80 years and patients ≥ 80 years after matching, respectively (standardized difference = 0.043).

Table 2.

Standardized differences of the categorical matching parameters before and after matching

| < 80 Years | ≥ 80 Years | Standardized difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | Matched sample | Original sample | |

| Male | 83 | 23.06 | 83 | 23.06 | 0.000 | 0.245 |

| ASA I | 6 | 1.67 | 8 | 2.22 | 0.040 | 0.345 |

| ASA II | 115 | 31.94 | 119 | 33.06 | 0.024 | 0.564 |

| ASA III–IV | 239 | 66.39 | 233 | 64.72 | 0.035 | 0.752 |

| Other fundoplication | 38 | 10.56 | 38 | 10.56 | 0.000 | 0.020 |

| Nissen fundoplication | 105 | 29.17 | 105 | 29.17 | 0.000 | 0.119 |

| Toupet fundoplication | 110 | 30.56 | 110 | 30.56 | 0.000 | 0.137 |

| Fundophrenicopexy | 107 | 29.72 | 107 | 29.72 | 0.000 | 0.269 |

| Paraoesophageal | 82 | 22.78 | 72 | 20.00 | 0.068 | 0.244 |

| Mixed | 46 | 12.78 | 54 | 15.00 | 0.064 | 0.283 |

| Up-side-down stomach | 232 | 64.44 | 234 | 65.00 | 0.012 | 0.447 |

| Risk factors | 168 | 46.67 | 154 | 42.78 | 0.078 | 0.241 |

| Risk factor: COPD | 79 | 21.94 | 77 | 21.39 | 0.013 | 0.204 |

| Risk factor: diabetes mellitus | 42 | 11.67 | 38 | 10.56 | 0.035 | 0.124 |

| Risk factor: aortic aneurysm | 2 | 0.56 | 3 | 0.83 | 0.033 | 0.027 |

| Risk factor: immunosuppression | 3 | 0.83 | 4 | 1.11 | 0.028 | 0.011 |

| Risk factor: steroids | 13 | 3.61 | 14 | 3.89 | 0.015 | 0.101 |

| Risk factor: smoking | 6 | 1.67 | 5 | 1.39 | 0.023 | 0.279 |

| Risk factor: coagulation disorder | 8 | 2.22 | 12 | 3.06 | 0.052 | 0.136 |

| Risk factor: antiplatelet therapy | 69 | 19.17 | 65 | 18.06 | 0.029 | 0.326 |

| Risk factor: anticoagulation | 13 | 3.61 | 14 | 3.89 | 0.015 | 0.175 |

ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists status, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Matched-pair analysis

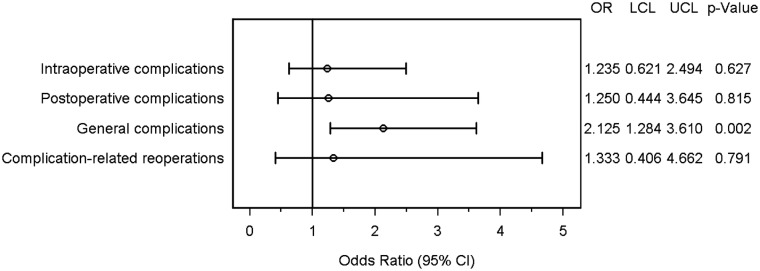

The matched-pair analysis revealed no systematic differences for intraoperative complications. There were 5.8% events only in the older group compared to 4.7% events only in younger patients (OR 1.235 [0.621; 2.494]; p = 0.627). Postoperative complications occurred in 2.8% of the matched pairs in older patients only and in 2.2% in younger patients only (OR 1.250 [0.444; 3.645]; p = 0.815). Patients ≥ 80 years showed significantly more general complications compared to the matched patients of the younger group (OR 2.125 [1.284; 3.610]; p = 0.002) (Fig. 3). On analyzing the frequency distribution of single general complications, only pneumonia showed a significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.041). There was no systematic difference in mortality (OR 2.000 [0.215; 35.199]; p = 1.000) or in any of the other general complications between the two groups (Table 3). Finally, no systematic differences were found between age groups for complication-related reoperations (1.7% vs.·2.2%, OR = 1.333 [0.406; 4.662], p = 0.791).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot—adjusted odds ratios. OR odds ratio, LCL lower confidence limit, UCL upper confidence limit

Table 3.

General complications

| Disadvantage | p-value* | OR* for matched samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 80 Years | ≥ 80 Years | OR | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||

| Fever | 1.11 | 1.11 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.079 | 12.702 |

| Urinary tract infection | 0.83 | 2.22 | 1.000 | 2.667 | 0.351 | 44.213 |

| Diarrhea | 0.56 | 0.56 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.017 | 60.294 |

| Gastritis | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| Thrombosis | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.83 | 0.28 | 1.000 | 0.333 | 0.000 | 12.420 |

| Pleural effusion | 2.50 | 4.44 | 1.000 | 1.778 | 0.497 | 7.451 |

| Pneumonia | 0.83 | 4.72 | 0.041 | 5.667 | 1.028 | 84.669 |

| COPD | 1.11 | 1.39 | 1.000 | 1.250 | 0.127 | 14.796 |

| Heart failure | 0.83 | 2.78 | 1.000 | 3.333 | 0.495 | 53.213 |

| Coronary heart disease | 0.56 | 1.11 | 1.000 | 2.000 | 0.118 | 95.634 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.28 | 0.56 | 1.000 | 2.000 | 0.024 | 1918.000 |

| Renal failure | 0.83 | 1.11 | 1.000 | 1.333 | 0.094 | 26.159 |

| Hypertensive crisis | 0.56 | 0.83 | 1.000 | 1.500 | 0.059 | 77.990 |

| Death | 0.83 | 1.67 | 1.000 | 2.000 | 0.215 | 35.199 |

| Other complications | 1.11 | 3.89 | 0.494 | 3.500 | 0.686 | 33.477 |

Relative frequency of cases with disadvantage for the respective age group (non-diagonal elements of 2 × 2 contingency table)

OR odds ratio, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

*Adjusted according to Bonferroni: factor 16

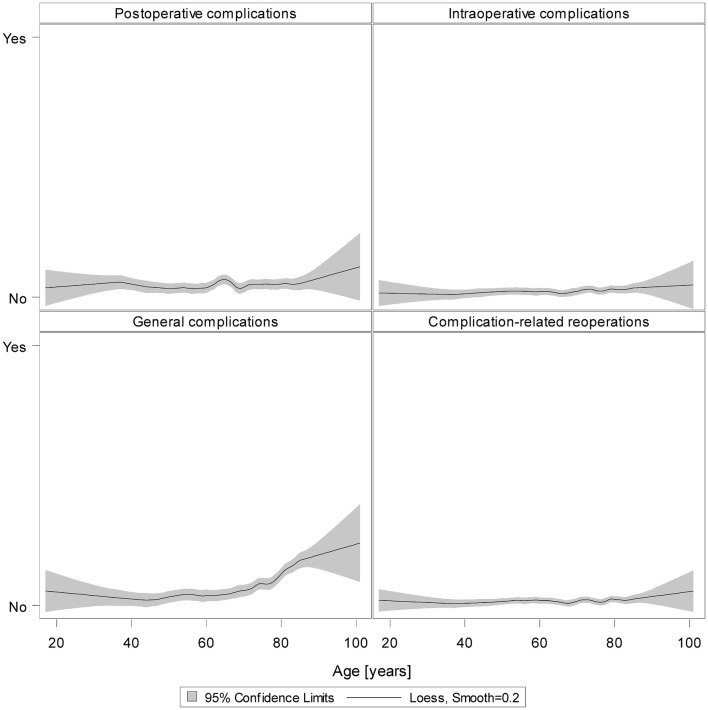

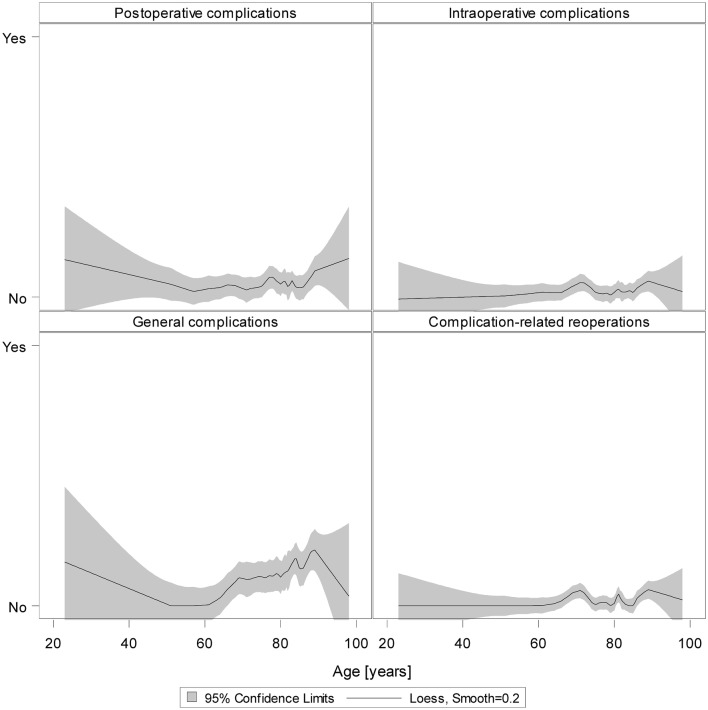

Loess regression

The results of unadjusted loess regression on all 3209 patients underline our results: Except for general complications, there were no reliable signs that more complications occurred in the older group (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Loess regression for postoperative, intraoperative, and general complications as well as complication-related reoperations for all patients (smooth = 0.2)

Furthermore, the results of unadjusted loess regression on only those patients of the matched samples revealed that the controls (patients < 80 years) who were chosen for matching because of their comparable characteristics did not show higher complication rates in higher ages only (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Loess regression for postoperative, intraoperative and general complications as well as complication-related reoperations for patients of the matched sample (smooth = 0.2)

Unadjusted analysis of 1-year follow-up data

If we restrict the analysis population to those patients with one-year follow-up data, n = 1505 patients < 80 years old (53.2%) and n = 160 patients ≥ 80 years old (42.0%) remain. Since these follow-up rates are profoundly different, one can assume that patient inclusion is strongly biased, e.g., restricted to those patients ≥ 80 years old who are relatively healthy. Nevertheless, we provide the recurrence rate, which is 4.8% in patients < 80 years old (n = 72) and 1.9% in patients ≥ 80 years old (n = 3), respectively (p = 0.092).

Discussion

This is the first propensity score-based, matched-pair analysis evaluating the complication rates of elective PEH in patients ≥ 80 years old. Our study showed that elderly patients can undergo PEH with intraoperative and postoperative surgical complication rates comparable with those of younger patients. The only general complication that was significantly more frequent after PEH in patients ≥ 80 years was pneumonia, highlighting the postoperative respiratory vulnerability of this patient population.

This study contributes to the ongoing and important discussion of balancing the perioperative risks and the supposed postoperative benefit of surgical procedures in elderly patients. Due to demographic trends in most countries, surgical patients increasingly present at an advanced age and with more comorbidities. It is accepted that advanced age in itself does not increase perioperative morbidity and mortality, and therefore there is no age limit for surgical interventions [15]. However, making therapeutic decisions for or against surgical treatment seems more challenging in older patients, since comorbidities may increase the surgical risk. Regarding PEH repair, one can argue that elective surgical treatment is the method of choice since symptoms may not be controlled with conservative treatment strategies and prevention of emergency situations with significantly higher morbidity and mortality seems appropriate [6]. There is a paucity of high-level evidence literature on elective PEH repair in elderly patients. A few studies defined elderly as > 70 years [3, 8, 9] or analyzed a very small group of elderly patients [5, 7, 10, 16], making comparison with our data difficult. Only one study evaluating elective PEH repair in 313 patients ≥ 80 years revealed a significant increase in minor morbidity (8.3% vs. 3.5%, p < 0.001), and a trend towards slightly higher mortality (1% vs. 0.4%, p = 0.16) and major morbidity (5.8% vs. 3.7%, p = 0.083) for patients ≥ 80 years [11]. The authors concluded that PEH repair can be performed with minimal morbidity and mortality in elderly patients. However, the main limitation of this study and most other observational studies is its confounding bias, especially when comparing two very different and unequal patient populations. Our propensity score, registry-based study revealed comparable rates for perioperative and postoperative surgical complications for elderly and younger patients, underlining the safety of the surgical approach itself in the older patient population.

Our findings may have some clinical impact. Since the natural course of untreated PEH is estimated to be associated with an annual symptom progression in 14% of patients, requiring emergency surgery in 1.1% of cases [17, 18], elective surgery seems important, especially for elderly patients. Our data support the concept of elective PEH repair in elderly patients with a low surgical mortality and morbidity. The surgical approach in elderly patients with PEH seems appropriate to significantly improve the quality of life [3] and prevent higher mortality and morbidity rates in emergency settings [6, 19, 20]. However, the higher rate of postoperative pneumonia in the older patient population underlines the importance of careful perioperative management and preventive strategies for general complications. Perioperative physiotherapy and respiratory training may help to reduce the risk of pulmonary complications after surgery [21].

Since this is a registry-based study, there are some limitations. Data on preventive respiratory strategies such as breathing exercises or inhalations are not recorded in the Herniamed Registry. Therefore, the potential effect of preventive respiratory physiotherapy in our patient population remains unknown. However, the following measurements are used to optimize data entry in the Herniamed Registry: signed contract with the responsible surgeon for data correctness and completeness, indication of missing data by the software, once again review of the perioperative outcome at 1-year follow-up and control of the data entry by experts as part of the certification process of hernia centers. Furthermore, to overcome the confounding bias of analyzing two different patient populations, a propensity score (PS) was applied in our study [22].

In summary, our study shows that age ≥ 80 years in itself is not a risk factor for higher intraoperative or postoperative complication rates compared to younger patients in elective PEH repair. However, careful perioperative management with prevention of respiratory complications seems of utmost importance in elderly patients. Further studies investigating recurrence rates and long-term complications are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of elective PEH repair in octogenarians and nonagenarians.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Compliance with ethical standards

Disclosures

F Köckerling—grants to fund the Herniamed Registry from Johnson & Johnson, Norderstedt; pfm medical, Cologne; Dahlhausen, Cologne; B Braun, Tuttlingen; MenkeMed, Munich and Bard, Karlsruhe. D Adolf—fees for statistical support from Herniamed gGmbH, Berlin. RF Staerkle, I Rosenblum, H Hoffmann, FS Lehmann, R Bittner, P Kirchhoff, and PM Glauser have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

References

- 1.Kahrilas PJ, Kim HC, Pandolfino JE. Approaches to the diagnosis and grading of hiatal hernia. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22(4):601–616. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lal DR, Pellegrini CA, Oelschlager BK. Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85(1):105–118. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hazebroek EJ, Gananadha S, Koak Y, Berry H, Leibman S, Smith GS. Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: quality of life outcomes in the elderly. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21(8):737–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen MS, Trastek VF, Deschamps C, Pairolero PC. Intrathoracic stomach. Presentation and results of operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;105(2):253–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallissey MT, Ratliff DA, Temple JG. Paraoesophageal hiatus hernia: surgery for all ages. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1992;74(1):23–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poulose BK, Gosen C, Marks JM, Khaitan L, Rosen MJ, Onders RP, Trunzo JA, Ponsky JL. Inpatient mortality analysis of paraesophageal hernia repair in octogenarians. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(11):1888–1892. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0625-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gangopadhyay N, Perrone JM, Soper NJ, Matthews BD, Eagon JC, Klingensmith ME, Frisella MM, Brunt LM. Outcomes of laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair in elderly and high-risk patients. Surgery. 2006;140(4):491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Louie BE, Blitz M, Farivar AS, Orlina J, Aye RW. Repair of symptomatic giant paraesophageal hernias in elderly (> 70 years) patients results in improved quality of life. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(3):389–396. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merzlikin OV, Louie BE, Farivar AS, Shultz D, Aye RW. Repair of symptomatic paraesophageal hernias in elderly (> 70 years) patients results in sustained quality of life at 5 years and beyond. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(10):3979–3984. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker DM, Rambhajan AA, Horsley RD, Johanson K, Gabrielsen JD, Petrick AT. Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair is safe in elderly patients. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(3):1186–1191. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spaniolas K, Laycock WS, Adrales GL, Trus TL. Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: advanced age is associated with minor but not major morbidity or mortality. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(6):1187–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Latzko M, Borao F, Squillaro A, Mansson J, Barker W, Baker T. Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernias. JSLS. 2014 doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stechemesser B, Jacob DA, Schug-Pass C, Kockerling F. Herniamed: an internet-based registry for outcome research in hernia surgery. Hernia. 2012;16(3):269–276. doi: 10.1007/s10029-012-0908-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Köckerling F, Bittner R, Kofler M, Mayer F, Adolf D, Kuthe A, Weyhe D. Lichtenstein versus total extraperitoneal patch plasty versus transabdominal patch plasty technique for primary unilateral inguinal hernia repair: a registry-based, propensity score-matched comparison of 57,906 patients. Ann Surg. 2017 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mennigen R, Senninger N. Is there an age limit for surgical interventions? Zentralbl Chir. 2015;140(3):304–311. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1328214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higashi S, Nakajima K, Tanaka K, Miyazaki Y, Makino T, Takahashi T, Kurokawa Y, Yamasaki M, Takiguchi S, Mori M, Doki Y. Laparoscopic anterior gastropexy for type III/IV hiatal hernia in elderly patients. Surg Case Rep. 2017;3(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s40792-017-0323-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stylopoulos N, Gazelle GS, Rattner DW. Paraesophageal hernias: operation or observation? Ann Surg. 2002;236(4):492–500. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200210000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Treacy PJ, Jamieson GG. An approach to the management of para-oesophageal hiatus hernias. Aust N Z J Surg. 1987;57(11):813–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1987.tb01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Staerkle RF, Skipworth RJ, Hansen RD, Hazebroek EJ, Smith GS, Leibman S. Acute paraesophageal hernia repair: short-term outcome comparisons with elective repair. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015;25(2):147–150. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tam V, Luketich JD, Winger DG, Sarkaria IS, Levy RM, Christie NA, Awais O, Shende MR, Nason KS. Non-elective paraesophageal hernia repair portends worse outcomes in comparable patients: a propensity-adjusted analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21(1):137–145. doi: 10.1007/s11605-016-3231-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boden I, Skinner EH, Browning L, Reeve J, Anderson L, Hill C, Robertson IK, Story D, Denehy L. Preoperative physiotherapy for the prevention of respiratory complications after upper abdominal surgery: pragmatic, double blinded, multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2018;360:j5916. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lonjon G, Porcher R, Ergina P, Fouet M, Boutron I. Potential pitfalls of reporting and bias in observational studies with propensity score analysis assessing a surgical procedure: a methodological systematic review. Ann Surg. 2017;265(5):901–909. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.