Abstract

Secretory human carbonic anhydrase VI (CA VI) has emerged as a potential drug target due to its role in pathological states, such as excess acidity-caused dental caries and injuries of gastric epithelium. Currently, there are no available CA VI-selective inhibitors or crystallographic structures of inhibitors bound to CA VI. The present study focuses on the site-directed CA II mutant mimicking the active site of CA VI for inhibitor screening. The interactions between CA VI-mimic and a series of benzenesulfonamides were evaluated by fluorescent thermal shift assay, stopped-flow CO2 hydration assay, isothermal titration calorimetry, and X-ray crystallography. Kinetic parameters showed that A65T, N67Q, F130Y, V134Q, L203T mutations did not influence catalytic properties of CA II, but inhibitor affinities resembled CA VI, exhibiting up to 0.16 nM intrinsic affinity for CA VI-mimic. Structurally, binding site of CA VI-mimic was found to be similar to CA VI. The ligand interactions with mutated side chains observed in three crystallographic structures allowed to rationalize observed variation of binding modes and experimental binding affinities to CA VI. This integrative set of kinetic, thermodynamic, and structural data revealed CA VI-mimic as a useful model to design CA VI-specific inhibitors which could be beneficial for novel therapeutic applications.

Subject terms: Enzymes, Medicinal chemistry

Introduction

Human carbonic anhydrases (CAs) are widespread enzymes known for over 80 years1. CAs regulate both intracellular and extracellular pH homeostasis through the catalysis of reversible carbon dioxide hydration to bicarbonate and proton. To date, there are twelve catalytically active human CAs, which display diverse sub-cellular localization, tissue-specific expression, and kinetic properties2,3. Among a broad spectrum of CA-linked research areas, clinical investigation is a major focus due to the implication of abnormal CA levels or their activities in diseases, such as glaucoma4, epilepsy5, obesity6, and cancer7. Therefore, many efforts have been dedicated over years to design CA isoform-selective compounds exhibiting sufficient affinity properties8. These derivatives would be prospective for the translation into the clinic because of therapeutic efficacy without inducing undesired side effects caused by inhibited vital off-target CAs. However, it is a challenging task because of the high structural homology among human CAs9.

CA VI is the only secreted human CA isoform found in saliva10, serum11, milk12, respiratory airways13, and alimentary canal14. Several studies have indicated the immunological CA VI function15,16 and have presented associations of CA VI with bitter taste perception17,18 or protection of excess acidity-caused complications, including dental caries19,20 and injuries of esophageal or gastric epithelium21. The link of CA VI with certain cancers, such as that of salivary glands, has been speculated by gene comparison study22, which have shown close relation of CA VI with CA IX, a marker of tumors23. Thus, there is a demand for effective and selective CA VI inhibitors, which would be relevant to determine the exact physiological role of CA VI.

For more than five decades, the most widely applied method in the search of CA isoform selective inhibitors has been the stopped-flow assay of the catalytic activity of CO2 hydration (SFA)24,25. However, SFA has several limitations, such as the largely unknown CO2 concentration and unfeasibility to measure inhibition constant below several nM26. Therefore, biophysical techniques, such as the fluorescent thermal shift assay (FTSA) and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), are promising alternatives to screen CA-targeting derivatives. FTSA is a high-throughput method exhibiting minimized biomolecule consumption and low limitations for binding affinity, thereby both strong (picomolar) and weak (millimolar) compounds can be identified during the same experiment26–29. ITC allows the direct determination of stoichiometry and thermodynamic parameters, such as affinity, enthalpy, entropy, and heat-capacity, during a single or several titration experiments but it demands relatively large quantities of proteins and has limitations for assessing the binding affinity26,30,31.

Importantly, two types of variables can be distinguished when binding reactions are carried out by FTSA or ITC: the observed parameters obtained from experimental setup and the intrinsic values calculated according to the corresponding observed data. Most studies on the development of CA inhibitors usually provide only observed binding parameters, which are dependent on experimental conditions and might be misleading. Both the CA and inhibitor exist in different protonation states in the solution compared with ones in the complex. Therefore, protonation-deprotonation reactions are required to initiate the binding of inhibitor to CA. Only intrinsic values subtract energetic contribution of binding-linked protonation events and thus are relevant for the rational drug design32–35.

Due to the recent advances in the structural and in silico biology, production of target recombinant proteins, including CAs, in large quantities is of high demand for in vitro inhibitor screening of drug-candidates during preclinical research. The literature lists a number of host cells for expression of recombinant proteins. Among microorganisms, the enterobacterium Escherichia coli (E. coli) is selected frequently owing to numerous advantages, such as rapid growth, easy genetic manipulation, and relative cost effectiveness36,37. However, the stability of heterologous protein in E. coli can be influenced by the several factors, including mRNA instability, codon bias, protein aggregation, toxicity, and lack of post-translational modification38,39. Therefore, different, more efficient strategies to obtain functionally active recombinant proteins in high yield are required for screens of chemical compounds with the aim to identify hits in the initial stages of drug discovery.

The goal of the present study was to design a CA II-based CA VI model protein, named as CA VI-mimic, for the search of CA-isoform selective inhibitors. As CA VI-mimic, mutant of CA II containing five point mutations, such as A65T, N67Q, F130Y, V134Q, L203T, was generated via site-directed mutagenesis. CA II was selected as a core for CA VI-mimic because purification yield of CA II from E. coli is ~10-fold higher than CA VI, CA II has highest catalytic efficiency among CAs, and CA II is confirmed as a stable CA protein for X-ray crystallography. Here enzymatic activity and inhibition of CA II, CAVI-mimic, and CA VI was determined by SFA. Biophysical studies on inhibitor binding to CA II, CA VI-mimic, and CA VI were carried out by ITC and FTSA. X-ray crystallography and computational modeling were used to compare positions of several inhibitors in the active sites of CA II, CA VI-mimic, and CA VI. Observed and intrinsic thermodynamics were in line with structural results which confirmed the relevance of CA VI-mimic as a CA VI model protein. The most tested benzenesulfonamides bound to CA VI-mimic in a manner corresponding to their interactions with CA VI but not CA II, thereby emphasizing suitability of the investigated CA II mutant mimicking CA VI for inhibitor screening.

Results

Enzymatic activity of CA VI-mimic correlates with CA II, but not CA VI

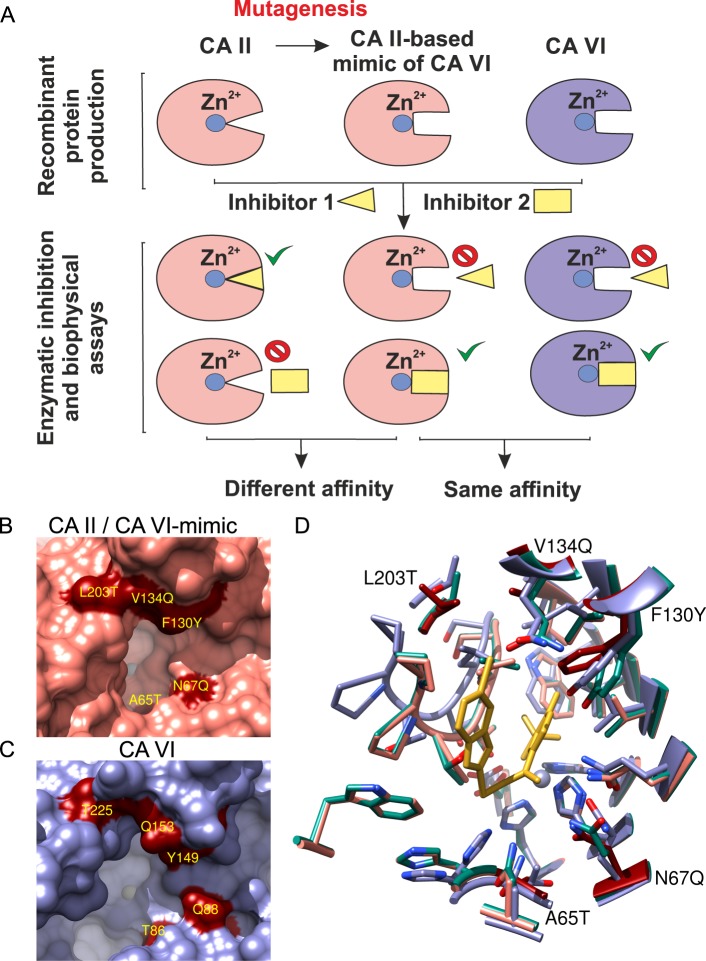

Studies on inhibitor selectivity towards diverse human CA isoforms are important to develop efficient compounds for the treatment of diseases caused by abnormal levels or activities of a particular CA isoform. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate inhibitor affinity to all human CAs, including CA VI. Since our previous study40 indicated a low yield of recombinant CA VI from E. coli, we generated CA II mutant as a CA VI model protein (CA VI-mimic) for inhibitor screening. Inhibitor affinities towards CA II and CA VI-mimic were expected to differ in the way imitating inhibitor binding to CA VI, but not CA II (Fig. 1A). Thus, negligible differences between inhibitor affinities towards CA VI and CA VI-mimic were presumed. According to computational modeling, five point mutations A65T, N67Q, F130Y, V134Q, L203T were chosen (Figs 1B–D and S1) and introduced into the active site of CA II.

Figure 1.

(A) The mimic of CA VI was prepared from CA II by site-directed mutagenesis of amino acids that differ between two CA isoforms. The CA VI-mimic protein served as a model of compound binding to CA VI. (B) Active site of CA II (PDB ID: 3KS3). Dark red molecular surfaces mark the positions of point mutations introduced in the active site of CA II to resemble CA VI by making a multiple-residue mutant of CA II (CA VI-mimic). (C) Active site of CA VI (PDB ID: 3FE4). The light blue areas are buried molecular surfaces between interacting molecules in the homodimeric complex. Dark red molecular surfaces mark the equivalent positions between multiple-residue mutant of CA II (CA VI-mimic) and CA VI. The labels belong to CA VI (CA II numbering). (D) Superposed structures of the binding pockets of CA II (rose; PDB ID: 3M96), CA VI (blue; PDB ID: 3FE4), and CA VI-mimic (green; PDB ID: 6QL2). The mutated residues of CA II are colored dark red. The zinc ion in the active site of each CA isoform is shown as a grayish sphere in panels (B–D).

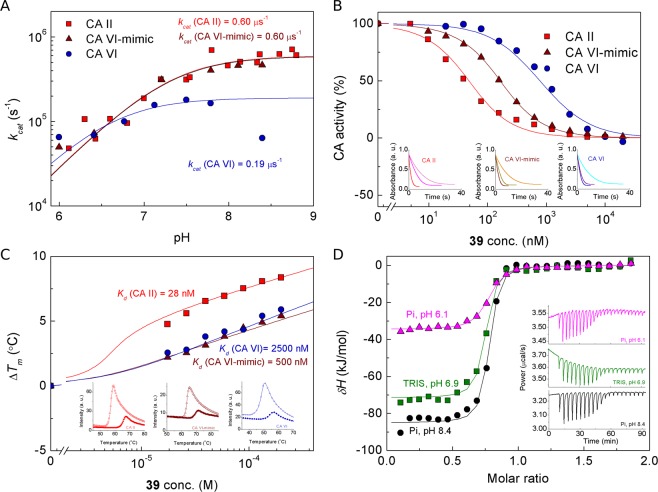

The catalytic activity of CA VI and CA VI-mimic to catalyze CO2 hydration reaction was measured by SFA (Figs 2A and S3). Analysis of kinetic data showed that site-directed mutagenesis did not significantly affect either the catalytic activity or pKa of zinc-bound water molecule of CA II. Catalytic constants (kcat) of CA II and CA VI-mimic did not differ (kcat values were 6.0 × 105 s−1), whereas kcat for CA VI was lower than CA VI-mimic by 3-fold (1.9 × 105 s−1). In the pH range 5.9–7.0 Michaelis constants (KM) as well as kcat values of the carbon dioxide hydration reaction were comparable: 7.3 ± 2.9 mM for CA II, 8.8 ± 1.8 mM for CA VI-mimic and 9.9 ± 3.2 mM for CA VI. However, in the pH range 7.1–8.4 KM values of CA VI-mimic (6.8 ± 2.0 mM) were closer to CA II (4.7 ± 1.0 mM) than to CA VI (11.3 ± 0.7 mM). Interestingly, maximum catalytic activity of CA VI was observed at pH 7.0–8.0 and it decreased at pH above 8.0. The determined pKa value of zinc-bound water molecule of CA VI was 6.6 ± 0.2. The observed inhibition constants by SFA correlated with dissociation constants determined by FTSA. Typical SFA curves of CA II, CA VI-mimic and CA VI inhibition by compound 39 are shown in Fig. 2B.

Figure 2.

Catalytic activity, inhibition and binding profiles of CA II (red squares), CA VI-mimic (wine triangles) and CA VI (royal circles). (A) The plot of kcat dependence on pH by stopped-flow CO2 hydration assay (SFA). Solid lines were fit using single protonation model. (B) Inhibition of CAs by compound 39 using SFA. Data points were fit to the Morrison eq. (solid lines)74,75. The insets show raw activity curves of CA catalyzed reaction without added inhibitor (red, wine, royal lines), CA inhibited reaction with 313 nM added compound 39 (magenta, dark yellow, purple lines) and spontaneous CO2 hydration reaction (pink, orange, cyan lines) in the absence of CA. (C) Dosing curves of compound 39 binding to CAs by fluorescent thermal shift assay (FTSA). Data points show the ΔTm as a function of the total concentration of compound 39 added and the lines are simulated using fitting parameters when temperature is 37 °C, CA concentration is 10 µM, enthalpy of unfolding is 690 kJ/mol for CA II and CA VI-mimic, and 480 kJ/mol for CA VI, enthalpy of binding is −42 kJ/mol, heat capacity of binding is −0.8 J/(molK) and the reference melting temperature is 56.8 °C for CA II, 63.1 °C for CA VI-mimic, and 47.6 °C for CA VI. The ΔTm shift is equal for CA VI-mimic and CA VI, but Kd’s differ due to different enthalpies of unfolding. The insets show CA unfolding curves at 0 and 200 µM inhibitor 39 concentrations. (D) Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) curves of EZA binding to CA VI-mimic in phosphate (Pi, pH 6.1 (▲) and 8.4 (●)) and TRIS buffer (pH 6.9 (■)) at 25 °C. Lines were fitted using single binding site model. The insets show raw data ITC curves at 10 µM CA VI-mimic concentration. Different observed enthalpies of binding illustrate the presence of binding-linked protonation reactions that must be accounted for the determination of intrinsic binding parameters.

Influence of buffer and pH for the observed binding affinity of ethoxzolamide to CA VI-mimic

Biophysical methods, such as ITC and FTSA, enable measurements of observed thermodynamics and thereafter calculations of intrinsic affinities. The observed binding profiles are altered by linked reactions and therefore, only intrinsic binding parameters can be correlated with compound structures, thereby revealing structural reasons for protein-ligand binding affinity.

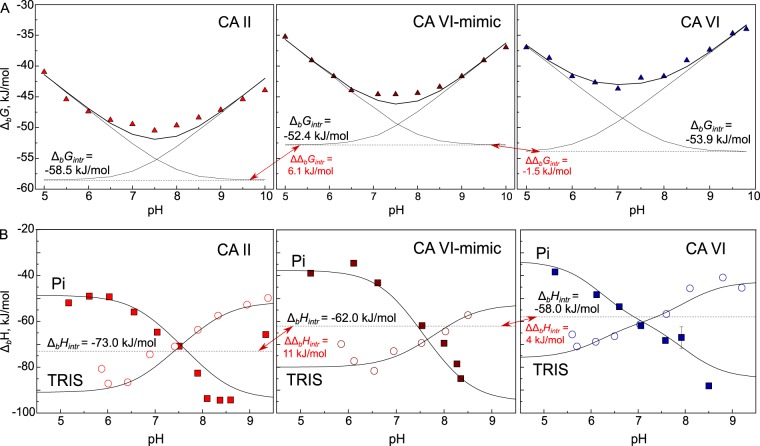

Binding energetics are significantly affected by several protonation-deprotonation events which are necessary for the binding of sulfonamide derivative to CA. Only deprotonated sulfonamides can interact with the zinc cation in the active site of pronated CA, containing zinc-coordinated water molecule (protonated hydroxy group). In this study, observed and intrinsic affinities of inhibitor binding to CA VI-mimic were determined and compared to their affinities towards CA II and CA VI. The obtained experimental data by FTSA on interactions between ethoxzolamide (EZA) and CA VI-mimic in buffers with different pH showed that pH remarkably influenced the observed binding Gibbs energy (ΔbGobs, Fig. 3A). The dependence of ΔbGobs on pH has also been observed previously40,41 when EZA binding to CA II or CA VI was measured. The strongest interaction was determined near neutral pH and became weaker both in acidic and alkaline pH. Sulfonamide group usually has pKa in the range between 7 and 10, whereas CA isoforms have pKa around 7. Therefore, diminished EZA affinity in acidic solution was because the fraction of binding-ready deprotonated form of EZA decreased by 10-fold with every pH unit. Similarly, EZA affinity decreased in alkaline solution because the fraction of binding-ready CA with the zinc-bound protonated hydroxide (water molecule) decreased. According to U-shaped curve as the global fit of experimental data extrapolated to 25 °C, intrinsic binding Gibbs energy (ΔbGintr) change upon EZA interaction with CA VI-mimic was determined to be −52.4 kJ/mol which was 7.8 kJ/mol greater than the highest experimentally observed value (−44.6 kJ/mol at pH 7.1). Difference of ΔbGintr (ΔΔbGintr) between EZA interaction with CA VI-mimic and CA VI were smaller (ΔΔbGintr = −1.5 kJ/mol) compared to that between CA VI-mimic and CA II (ΔΔbGintr = 6.1 kJ/mol).

Figure 3.

(A) Comparison of observed Gibbs energy changes (ΔbGobs) upon EZA binding to CA II (red), CA VI-mimic (dark red), and CA VI (blue) as a function of pH (25 °C). Experiments were performed by FTSA in universal buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM sodium acetate, and 25 mM sodium borate). The pKa for CA VI-mimic was determined to be 7.1. (B) The observed enthalpy changes (ΔbHobs) upon EZA binding to CA II (red), CA VI-mimic (dark red), and CA VI (blue) as a function of pH in two different buffers (sodium phosphate (Pi) and TRIS), which have different protonation enthalpies. Experiments were performed by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) at 25 °C. The dashed line shows the intrinsic binding enthalpy (ΔbHintr), which is independent of pH. The pKa for CA VI-mimic was determined to be 7.3. Thermodynamic binding parameters of EZA binding to CA II and CA VI have been previously published40,41. Red arrows indicate difference in ΔbGintr or ΔbHintr of EZA binding to CA VI-mimic compared to CA II or CA VI.

Observed standard enthalpy changes (ΔbHobs) upon EZA binding to CA VI-mimic formed an X-shaped curve which depended on pH and buffer (Fig. 3B). The same tendency has been found previously40,41 when ΔbHobs of EZA binding to CA II or CA VI was analyzed. Results were obtained by ITC titration at 25 °C in two buffers exhibiting different protonation enthalpies: sodium phosphate (Pi) and TRIS. Upon EZA-CA VI-mimic titration, more than 20 kJ/mol difference in ΔbHobs was observed in same buffer at different pHs (in TRIS buffer: −81.6 kJ/mol at pH 6.5, −57.2 kJ/mol at pH 8.5; in Pi buffer: −38.9 kJ/mol at pH 5.2, −84.9 kJ/mol at pH 8.4). To dissect protonation influence, intrinsic enthalpy (ΔbHintr) of EZA interaction with CA VI-mimic was globally fitted to be −62.0 kJ/mol. Difference of ΔbHintr (ΔΔbHintr) between EZA interaction with CA VI-mimic and CA VI were smaller (4.0 kJ/mol) compared to that between CA VI-mimic and CA II (11.0 kJ/mol). Thus, ΔbHintr were in line with ΔbGintr, confirming that CA II mutant was mimicking CA VI for EZA binding.

Furthermore, analysis of U- and X-shaped curves obtained by FTSA and ITC, respectively, led to the characterization of two important parameters of CA VI-mimic: ionization constant (pKa) and enthalpy of protonation (ΔpH) of the zinc-bound water molecule (Table 1). The pKa of CA VI-mimic was determined to be 7.2 at 25 °C as the average of two pKa values evaluated independently by two techniques: 7.1 by FTSA and 7.3 by ITC. The pKas of CA II and CA VI-mimic matched each other within the error margin of 0.2 pH unit42, whereas pKas of CA VI and CA VI-mimic significantly differed by 1.0 pH (25 °C). Thus, target five point mutations of CA II, which were introduced to design CA VI-mimic, did not affect amino acids surrounding zinc in active sites of CA II at the level causing significant difference of pKas between CA II and CA VI-mimic. Moreover, ΔpH for CA VI-mimic was assessed to be −38.0 kJ/mol at 25 °C. The difference of ΔpH between CA VI and CA VI-mimic (6.0 kJ/mol) was 2-fold lower than difference of ΔpH between CA II and CA VI-mimic (12.0 kJ/mol). Therefore, experiments with one inhibitor EZA resulted in both pKa and ΔpH for CA VI-mimic, which are essential parameters to determine intrinsic energetics of any other inhibitor binding to CA VI-mimic.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic parameters of protonation of zinc-bound hydroxide anion of studied CA isoforms as determined by FTSA and ITC at 25 °C.

| Protein | pKa | ΔpG, kJ/mol | ΔpH, kJ/mol | TΔpS, kJ/mol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA IIa | 7.1 | −40.5 | −26.0 | 14.5 |

| CA VI-mimic | 7.2 | −41.1 | −38.0 | 3.1 |

| CA VIb | 6.2 | −35.4 | −32.0 | 3.4 |

Hydrophobic substituents and fluorine substituents significantly affected intrinsic inhibitor binding affinity for CA VI-mimic

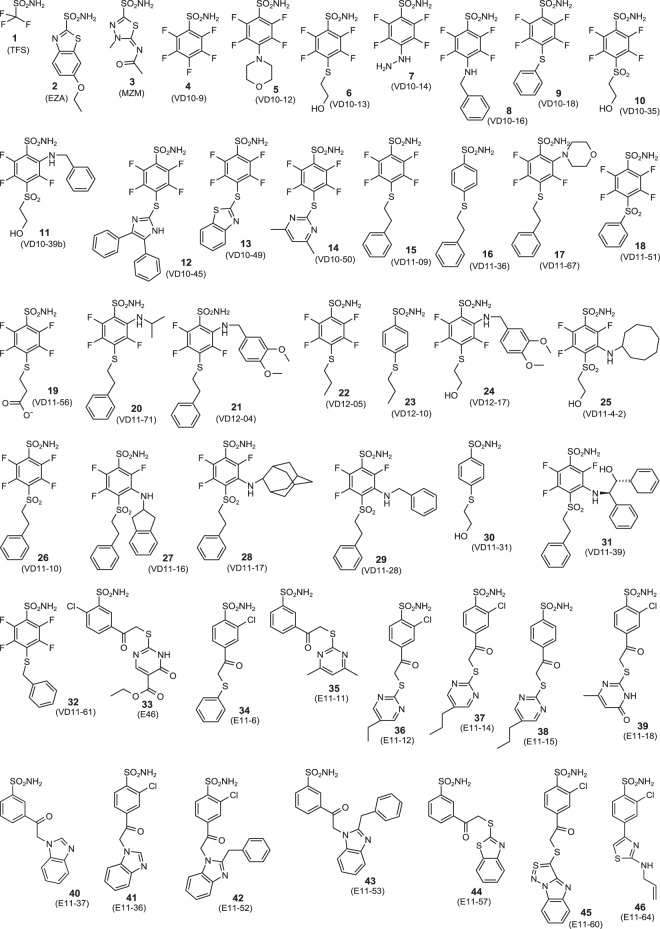

Here 43 benzenesulfonamide derivatives binding to CA VI-mimic was measured by FTSA and inhibition constants of several selected compounds were confirmed by SFA. Trifluoromethanesulfonamide (TFS), EZA, and methazolamide (MZM) were used as controls. Structures of tested compounds are shown in Fig. 4, while dissociation constants (Kd) are listed in Tables 2 and S1 (examples of raw and integrated data of inhibitor binding to CA VI-mimic by FTSA and ITC at different pHs are indicated in Fig. 2C,D, respectively).

Figure 4.

Chemical structures of 1-46 compounds designed as CA inhibitors. Compounds 1-3 are standard inhibitors of CAs that we used here as control compounds (TFS, EZA, and MZM).

Table 2.

The Kd_obs and Kd_intr values (nM) for interactions between inhibitor and three CA proteins: CA II, CA VI-mimic, and CA VI.

| Inhibitor | Lab. name | pKa_SA | K d_ obs (nM) | K d_ intr (nM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA II | CA VI-mimic | CA VI | CA II | CA VI-mimic | CA VI | |||

| 1. | TFS | 6.02 | 20 | 33 | 14 | 8.0 | 15 | 1.2 |

| 2. | EZA | 7.82 | 1.3 (<5.0) | 17 (<54) | 33 (<54) | 0.073 | 1.1 | 0.40 |

| 3. | MZM | 6.86 | 100 | 330 | 830 | 27 | 97 | 44 |

| 4. | VD10-9 | 8.12 | 46 | 130 | 430 | 1.4 | 4.7 | 2.7 |

| 5. | VD10-12 | 8.61 | 18 | 100 | 1100 | 0.19 | 1.2 | 2.4 |

| 6. | VD10-13 | 8.14 | 11 | 130 | 200 | 0.32 | 4.2 | 1.2 |

| 7. | VD10-14 | 8.84 | 91 | 330 | 1000 | 0.57 | 2.4 | 1.3 |

| 8. | VD10-16 | 8.47 | 9.1 | 200 | 1200 | 0.13 | 3.3 | 3.7 |

| 9. | VD10-18 | 7.80 | 3.4 | 140 | 200 | 0.20 | 9.8 | 2.5 |

| 10. | VD10-35 | 7.28 | 17 | 130 | 67 | 2.5 | 22 | 2.1 |

| 11. | VD10-39b | 7.85 | 83 | 140 | 130 | 4.6 | 8.8 | 1.5 |

| 12. | VD10-45 | 7.69 | 5.8 | 140 | 140 | 0.43 | 12 | 2.2 |

| 13. | VD10-49 | 7.83 | 0.65 | 110 | 200 | 0.037 | 7.2 | 2.3 |

| 14. | VD10-50 | 8.02 | 9.6 (<43) | 330 (140) | 1000 (630) | 0.37 | 15 | 7.9 |

| 15. | VD11-9 | 8.05 | 1.7 | 100 | 400 | 0.061 | 4.1 | 3.0 |

| 16. | VD11-36 | 10.1 | 12 | 500 | 1100 | 0.0039 | 0.20 | 0.077 |

| 17. | VD11-67 | 8.67 | 5900 | 100 000 | 100 000 | 55 | 1000 | 190 |

| 18. | VD11-51 | 7.07 | 3.3 | 130 | 160 | 0.68 | 31 | 6.6 |

| 19. | VD11-56 | 7.97 | 20 | 330 | 500 | 0.86 | 16 | 4.4 |

| 20. | VD11-71 | 8.67 | 500 | 2500 | 3300 | 4.6 | 26 | 6.3 |

| 21. | VD12-04 | 8.67 | 1800 | 3300 | 20 000 | 17 | 35 | 38 |

| 22. | VD12-05 | 8.15 | 2.2 | 50 | 140 | 0.065 | 1.7 | 0.86 |

| 23. | VD12-10 | 10.2 | 25 (<36) | 500 (200) | 830 (3900) | 0.0070 | 0.16 | 0.048 |

| 24. | VD12-17 | 8.67 | 1300 | 5000 | 11 000 | 12 | 52 | 21 |

| 25. | VD11-4-2 | 8.01 | 56 | 100 | 67 | 2.2 | 4.5 | 0.54 |

| 26. | VD11-10 | 7.22 | 1.2 | 67 | 140 | 0.21 | 13 | 4.8 |

| 27. | VD11-16 | 7.87 | 35 | 1000 | 2000 | 1.9 | 59 | 22 |

| 28. | VD11-17 | 7.87 | 50 | 140 | 330 | 2.6 | 8.5 | 3.6 |

| 29. | VD11-28 | 7.87 | 6.7 | 200 | 110 | 0.35 | 12 | 1.2 |

| 30. | VD11-31 | 9.96 | 140 | 1000 | 5000 | 0.070 | 0.55 | 0.50 |

| 31. | VD11-39 | 7.87 | 33 | 2000 | 1000 | 1.8 | 120 | 11 |

| 32. | VD11-61 | 8.53 | 3.3 | 140 | 330 | 0.042 | 2.1 | 0.87 |

| 33. | E46 | 8.90 | 50 | 50 | 200 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.23 |

| 34. | E11-6 | 8.70 | 5.6 | 330 | 1100 | 0.048 | 3.3 | 2.0 |

| 35. | E11-11 | 9.40 | 1000 | 2000 | 13 000 | 1.8 | 4.0 | 4.5 |

| 36. | E11-12 | 8.90 | 8.5 | 500 | 5000 | 0.047 | 3.1 | 5.7 |

| 37. | E11-14 | 8.90 | 7.1 | 330 | 3300 | 0.039 | 2.1 | 3.8 |

| 38. | E11-15 | 9.40 | 560 | 1300 | 5000 | 0.98 | 2.5 | 1.8 |

| 39. | E11-18 | 8.90 | 28 (<54) | 500 (300) | 2500 (1600) | 0.15 | 3.1 | 2.8 |

| 40. | E11-37 | 9.60 | 3600 | 3300 | 6700 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 1.5 |

| 41. | E11-36 | 8.30 | 8.3 | 500 | 3300 | 0.16 | 12 | 14 |

| 42. | E11-52 | 8.70 | 2.9 | 330 | 1400 | 0.025 | 3.3 | 2.5 |

| 43. | E11-53 | 9.60 | 1700 | 3300 | 10 000 | 1.9 | 4.2 | 2.3 |

| 44. | E11-57 | 9.60 | 140 | 500 | 3300 | 0.16 | 0.63 | 0.75 |

| 45. | E11-60 | 8.70 | 250 | 500 | 3300 | 2.2 | 4.9 | 5.9 |

| 46. | E11-64 | 9.40 | 100 | 1100 | 17 000 | 0.16 | 2.2 | 5.5 |

The observed inhibitor affinities for CA VI-mimic were obtained experimentally by FTSA (pH 7.0, 37 °C), whereas the intrinsic parameters were calculated from the corresponding observed data using pKa of 7.0 for CA VI-mimic at 37 °C as explained in the methods part. The standard error of Kd measurements is ±2-fold. The pKa values of applied sulfonamide amino group (pKa_SA) and inhibitor affinities towards CA II and CA VI have been already reported58,86. Dissociation constants Kds of selected compounds were confirmed by SFA (pH 7.5). Experiments were performed at 23 °C and observed Kds were extrapolated to 37 °C using van’t Hoff equation when enthalpy of binding is −42 kJ/mol. The values at 37 °C are given in parentheses. The determined Kds at 23 °C are given in Table S2.

According to observed thermodynamics, EZA was shown to be the strongest binder to CA VI-mimic with observed Kd (Kd_obs) of 17 nM. From a series of fluorinated benzenesulfonamides, compounds 22 and 26 bearing substituents at para position were characterized to be the most potent CA VI-mimic inhibitors bound with observed Kd (Kd_obs) in the range of 50–67 nM. The comparison between binding affinities of corresponding fluorinated and nonfluorinated compounds (6 vs 30, 15 vs 16, and 22 vs 23) showed that fluorination significantly increased observed binding affinity and diminished pKa of inhibitor sulfonamide amino group. For instance, Kd_obs for 30 and 6 binding to CA VI-mimic increased 8-fold upon fluorination (from 1000 nM to 130 nM), whereas Kd_obs for 23 and 22 increased affinity 10-fold (from 500 nM to 50 nM). Fluorines reduced pKa of sulfonamide group significantly: from 9.96 to 8.14 for inhibitors 30 and 6, respectively, and from 10.2 to 8.15 for compounds 23 and 22, respectively (Table 2). Correspondingly, chlorine in most compounds also increased observed affinity and reduced pKa of inhibitor sulfonamide amino group. For example, upon chlorination Kd_obs for 40 and 41 interaction with CA VI-mimic increased 430-fold (from 3600 nM to 8.3 nM, respectively), while pKa values were lowered by 1.30 unit (from 9.60 to 8.30, respectively).

To investigate structure-activity relationships, intrinsic Kd (Kd_intr) values for interactions between CA VI-mimic and investigated series of compounds were calculated. The largest differences between Kd_obs and Kd_intr values were determined for nonfluorinated benzenesulfonamides (16, 23, and 30), where the binding to CA VI-mimic differed 2500, 3200, and 1800-fold, respectively. Only five compounds (10, 18, 26, TFS, and MZM) exhibited lower than 10-fold difference between the Kd_obs and Kd_intr. According to intrinsic thermodynamics, the strongest binders were inhibitors 16, 23, 30, and 33 with Kd_intr in the range of 0.16–0.55 nM. Therefore, the strongest intrinsic interaction between inhibitor and CA VI-mimic was observed when inhibitor did not possess any fluorines in benzenesulfonamide scaffold and contained a hydrophobic substituent at para position, such as SCH2CH2CH3 (Kd_intr for inhibitor 23 was 0.16 nM) and SCH2CH2Ph (Kd_intr for inhibitor 16 was 0.20 nM). Exceptionally, inhibitor 33 was the strongest binder to CA VI-mimic with chlorine at ortho position and large hydrophilic group at meta position (Kd_intr was 0.31 nM). Replacement of the methyl group (inhibitor 23) by hydrophilic hydroxyl group (inhibitor 30) weakened intrinsic binding affinity more than 3-fold (from to 0.16 nM to 0.55 nM). Moving on to the structural analysis of fluorinated benzenesulfonamides, two inhibitors were determined to be the strongest binders to CA VI-mimic: compound 5 bearing 4-Morpholinyl group at para position (Kd_intr was 1.2 nM) and 22 with SCH2CH2CH3 group at para position (Kd_intr was 1.7 nM). In line with results obtained from nonfluorinated compounds, hydrophobic contacts between inhibitors and CA VI were identified to be significant because the exchange of methyl group (inhibitor 22) by hydroxyl group (inhibitor 6) or carboxyl group (inhibitor 19) weakened intrinsic interaction by 2 and 9-fold, respectively. Apparently, the number of methyl groups of substituents at para position had significant effect on intrinsic binding affinity. The inhibitor 32 with SCH2Ph bound to CA VI-mimic 2-fold stronger than inhibitor 15 with SCH2CH2Ph and 4-fold stronger than inhibitor 9 with SPh. Most often, introducing diverse substituents at meta position did not change intrinsic binding affinity significantly (6 vs 25, 26 vs 28, and 26 vs 29), except for 26 vs 31 bearing large hydrophobic group which weakened interaction 9-fold. The compound 17 bearing two large and highly hydrophobic substituents at ortho and para positions was the weakest binder not only according to the observed parameters (Kd_obs was 100 µM), but also intrinsic data (Kd_intr of 1000 nM).

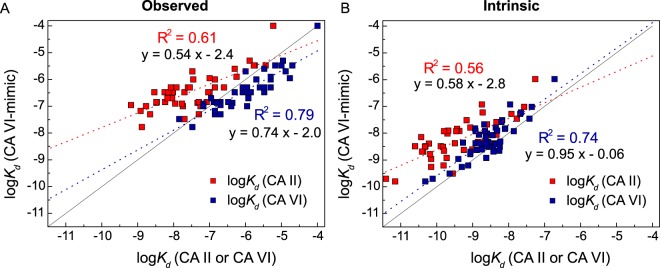

Thermodynamically CA VI-mimic binds benzenesulfonamides similarly to CA VI but differing from CA II

To evaluate if CA VI-mimic based on CA II is a suitable CA VI model protein for inhibitor screening, observed and intrinsic affinities represented by logarithmic Kd values of inhibitor binding to CA II, CA VI-mimic, and CA VI were compared by applying linear regression. A higher linear correlation was determined between observed affinities of inhibitor binding to CA VI and CA VI-mimic (R2 = 0.79) compared to the observed affinities of inhibitor interaction with CA II and CA VI (R2 = 0.61; Fig. 5A). Analysis of the calculated intrinsic parameters were in line with experimentally measured observed data, emphasizing a stronger correlation of the intrinsic thermodynamics of inhibitor binding to CA VI and CA VI-mimic (R2 = 0.74) compared to that of CA II and CA VI-mimic (R2 = 0.56; Fig. 5B). Furthermore, regression line slopes indicating the comparison of inhibitor binding to CA VI and CA VI-mimic (0.74 for observed affinity, 0.95 for intrinsic affinity) were larger than the corresponding slopes for CA II and CA VI (0.54 for observed affinity, 0.58 for intrinsic affinity), thereby indicating a lower difference between the inhibitor binding towards CA VI-mimic and CA VI compared to CA II.

Figure 5.

Comparison of logKd values representing observed (A) and intrinsic (B) inhibitor binding affinities towards CA VI-mimic and CA II (red squares) or CA VI-mimic and CA VI (blue squares). Straight line represents a model of equal affinity of inhibitor binding to pairwise proteins. Red and blue dashed lines show linear regression models for inhibitor binding to CA II and CA VI, respectively. R2 values and linear equations are indicated. Experiments were performed by FTSA (pH 7.0, 37 °C).

The influence of investigated CA II mutations on inhibitor binding thermodynamics was further analyzed by calculating the absolute error (AE) values from logarithmic observed or intrinsic Kds of inhibitor binding to CA VI-mimic, CA II, and CA VI. According to the observed thermodynamics, binding affinities of only 12 inhibitors out of 46 tested compounds towards CA VI-mimic was more similar to CA II than CA VI. For the intrinsic data, only 6 compounds were identified as CA VI-mimic binders with the affinity more alike CA II compared to CA VI. Moreover, mean absolute errors (MAEs) as the averages for each AE were also evaluated. MAEs of AEobs,CA II and AEintr,CA II were equal to 1.1, while MAEs of AEobs,CA VI and AEintr,CA VI were significantly smaller, 0.47 and 0.41, respectively. Therefore, CA VI-mimic designed via site-directed mutagenesis from CA II was characterized to be a proper model of CA VI for observed and intrinsic inhibitor binding reactions.

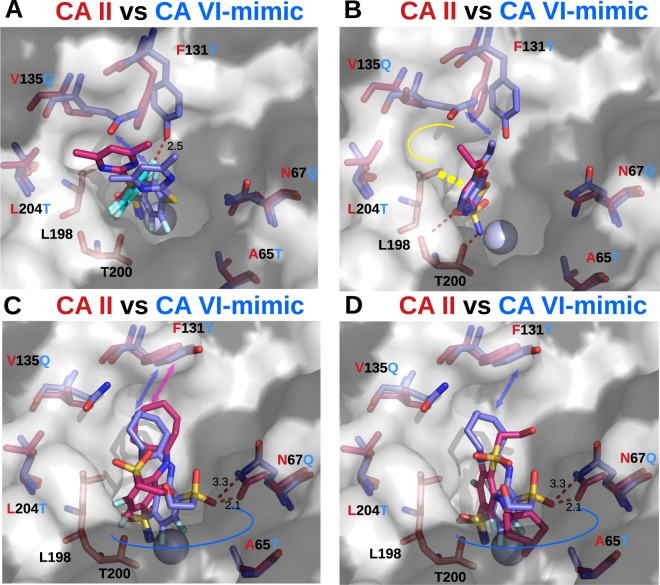

Differences in inhibitor binding affinities are due different binding modes as determined by crystallographic analysis of CA II and CA VI-mimic

Despite numerous attempts, the crystal structures of recombinant CA VI complexes with sulfonamide-based inhibitors were not obtained by soaking. Even though CA VI crystals survived soaking procedure, crystals did not contain the clear electron densities of inhibitors. The co-crystallization of CA VI protein with several inhibitors failed, as we did not obtain any crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction experiment. Most likely, CA VI complexes with sulfonamide-based inhibitors cannot be crystallized using crystallization conditions that are effective for the unbound CA VI protein.

To structurally investigate the binding of benzenesulfonamides with CA VI, we have engineered CA VI-mimic and applied in crystallographic studies. We have solved crystal structures of CA VI-mimic complexes with three inhibitors (Fig. S2): EZA (PDB ID: 6QL2), inhibitor 14 (PDB ID: 6QL1), and 25 (PDB ID: 6QL3). These complexes were compared with the corresponding complexes composed of CA II and same ligands (EZA (PDB IDs: 3CAJ (X-ray), 6BCC (neutron diffraction)), inhibitor 14 (PDB ID: 4HT0), and 25 (4PYY)). The space groups and unit cell parameters of CA VI-mimic crystals were similar to those of CA II (Table 3). There was one unique protein-ligand complex in the asymmetric unit. CA VI-mimic binding pocket was found to be similar to CA VI according to crystallographic studies (Fig. 1D) followed by thermodynamic analysis. For this reason, the insights into the compound binding mode to CA VI-mimic are likely to be valid for analyzing the ligand binding data to CA VI.

Table 3.

Data collection and refinement statistics of human CA VI-mimic and its complexes with inhibitors inhibitor 14, 25, and EZA.

| Isoform-ligand | CA VI-mimic – inhibitor 14 | CA VI-mimic - EZA | CA VI-mimic – inhibitor 25 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB ID | 6QL1 | 6QL2 | 6QL3 |

| Data-collection statistics | |||

| Space group | P1211 | P1211 | P1211 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å) | a = 42.3, b = 41.4, c = 71.2, β = 104.3° | a = 42.1, b = 41.3, c = 71.4, β = 104.2° | a = 42.2, b = 41.4, c = 71.9, β = 104.2° |

| Resolution range (Å) | 1.42–69.0 | 1.30–40.9 | 1.35–69.7 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.976300 | 0.975522 | 0.975522 |

| Radiation source | EMBL, P14 | EMBL, P14 | EMBL, P14 |

| Unique reflections number | 42097 | 56403 | 52382 |

| Rmerge, overall (outer shell) | 0.042(0.241) | 0.067 (0.334) | 0.088 (0.338) |

| I/σ overall (outer shell) | 22.7(7.2) | 13.1 (5.0) | 10.8 (4.1) |

| Multiplicity overall (outer shell) | 7.0 (6.6) | 6.9 (6.9) | 6.8 (6.7) |

| Completeness (%) overall (outer shell) | 92.8 (74.1) | 96.4 (94.5) | 98.8 (99.0) |

| Wilson B-factor | 13.2 | 13.1 | 9.3 |

| Refinement statistics: | |||

| Rwork | 0.157 | 0.119 | 0.116 |

| Rfree | 0.185 | 0.157 | 0.156 |

| RMSD bond lengths, (Å) | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.033 |

| RMSD bond angles (°) | 2.000 | 1.991 | 2.195 |

| Average B factors (Å2): | |||

| all | 16.7 | 20.4 | 15.0 |

| main-chain | 13.5 | 16.3 | 10.3 |

| side-chain | 16.2 | 21.7 | 14.8 |

| inhibitors | 26.9 | 13.3 | 17.3 |

| waters | 27.6 | 33.1 | 31.3 |

| zinc | 7.7 | 9.1 | 4.7 |

| other molecules | 40.5 | 37.0 | 36.9 |

| Number of atoms: | |||

| all | 2562 | 2380 | 2482 |

| protein | 2181 | 2111 | 2127 |

| inhibitor | 69 | 16 | 28 |

| water | 287 | 226 | 275 |

| zinc | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| other molecules | 24 | 26 | 51 |

| Ramachandran statistics (%): | |||

| most favored regions | 96 | 97 | 97 |

| additionally allowed regions | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| outliers | 0 | 0 | 0 |

All datasets were collected at 100 K, test set size was 10%.

The comparison of binding mode of inhibitor 14 in the active sites of CA VI-mimic and CA II is shown in Fig. 6A. Inhibitor 14 in the active site of CA VI-mimic had two alternative binding modes characterized by different positions of the fluorinated ring: the ring was either lodged between Leu198 and Thr200 side chains (colored cyan in Fig. 6A), or located in the hydrophilic part of active site (colored blue). On the other hand, in the active site of CA II we had only one position of fluorinated ring – between Leu198 and Thr200. It looks like the replacement of Phe130 in CA II with tyrosine in CA VI-mimic enabled additional position of fluorinated ring of ligand due to a steric collision between the fluorine atom of fluorinated ring and the oxygen atom of Tyr130 side chain (the close contact found in the structure was 2.5 Å). The alternative position of the fluorinated ring of compound 14 in the active site of CA VI-mimic probably was available only due to spatial fluctuations of Tyr130 side chain. Also, due to a significantly larger size and the hydrophilicity of the side chain of Gln134 in CA VI-mimic compared to Val134 in CA II, the hydrophobic dimethylpyrimidine tail of inhibitor 14 was repelled in CA VI-mimic (see para-group of the cyan ligand, Fig. 6A). Therefore, the change of size and the hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity of the residues 130 and 134 upon mutation could be rationalized as the main causes for the relatively significant difference in the binding affinities: inhibitor 14 bound to CA II 40-fold better than to CA VI-mimic (Kd_intr values were 0.37 nM and 15 nM for CA II and CA VI-mimic, respectively; Table 2).

Figure 6.

Differences in the binding structural modes of three compounds in CA II and CA VI-mimic as determined by X-ray crystallography. The zinc ion in active sites of CAs is shown as a light blue sphere. CA II side chain residues and ligands bound to CA II are colored pink and are shown transparent. CA VI-mimic side chains as well as its ligands are colored blue and also shown transparent. Mutated CA II side chains are labeled red for CA II, blue for CA VI-mimic. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines and distances are marked. Hydrophobic part of active site is shown as white surface, whereas hydrophilic part is shown as gray surface. (A) Compound 14 bound to active sites of CA VI-mimic (two alternative conformations of 14 are shown in cyan and blue, PDB ID: 6QL1) and CA II. The second ring of the “cyan” conformation of 14 in CA VI-mimic is not resolved in crystal structure, and not shown. (B) EZA bound to active site of CA VI-mimic (PDB ID: 6QL2) and CA II (PDB ID 3CAJ). Interaction of L198 with the first ring of compound is marked by thick dashed yellow line. Yellow line designates hydrophobic pocket for binding of para-substituent. The typical interactions for sulfonamide moiety are indicated, whereas they are omitted for clarity in other panels. (C, D) Compound 25 bound to active site of CA VI-mimic (PDB ID: 6QL3) and CA II (two alternative conformations of the ligand are indicated, PDB ID 4PYY). Blue line designates a hydrophilic part of the active site of CA VI-mimic.

The model compound EZA was bound similarly in active sites of CA II and CA VI-mimic (Fig. 6B). Some discrepancy was present only in the positions of highly flexible ethoxy moiety. The aliphatic-aromatic interactions between the methyl group of Leu198 and the first ring of EZA was present in both cases. The larger side chain of Tyr130 slightly changed the position of EZA aromatic ring in CA VI-mimic as compared with CA II due to steric conflicts. It is important also to note the role of the residue 134 interacting with the hydrophobic tail of EZA, similarly to the observation for inhibitor 14 above. The hydrophobic Val134 sidechain in CA II was mutated into hydrophilic Gln134 in CA VI, leading to the worsening of the interaction. Thus, the mutations of residues 130 and 134 were the likely reasons for 15-fold stronger binding of EZA to CA II, as determined by intrinsic thermodynamics (Kd_intr values were 0.073 nM and 1.1 nM for CA II and CA VI-mimic, respectively; Table 2).

The intrinsic binding parameters of inhibitor 25 towards CA II and CA VI-mimic were comparable (2.2 nM vs 4.5 nM, respectively; Table 2). In contrast, the binding modes of the compound found in crystal structures were different in these active sites. In CA II, inhibitor 25 had two alternative conformations: (1) the fluorinated ring located between Leu198 and Thr200, whereas the cyclooctyl ring replaced the side chain of Phe130 (Fig. 6C, pink ligand); (2) the fluorinated ring positioned in the hydrophobic part of active site, while the cyclooctyl ring – in the hydrophilic part (Fig. 6D, pink ligand). In CA VI-mimic, compound 25 had one well-defined conformation (Fig. 6C, D, blue) in which the cyclooctyl ring replaced the Tyr130 side chain, whereas the fluorinated ring occupied the hydrophilic part of active site. We can explain the presence of the single conformation of inhibitor 25 bound to CA VI-mimic. It seems that the mutation in position 67 (asparagine to glutamine) allows the position of fluorinated ring in hydrophilic part of active site when the para-substituent of ligand does not have sterical collision with side chain of residue 67 (compare side chain conformations of asparagine (CA II) and glutamine (CA VI-mimic), Fig. 6C, D). The same position of glutamine is found in the complexes of CA VI-mimic with inhibitor 14 and EZA ligands which means that compound 25 does not influence the position of side chain of residue 67 in CA VI-mimic. The replacement of asparagine (CA II) to glutamine (CA VI-mimic) creates the additional free space in the active site and allows for another binding mode.

Discussion

Nowadays enzymes encompass over one-third of drug targets investigated by large pharmaceutical companies43, thereby emphasizing the relevance of target-based drug approach. This strategy aims to identify the compounds which would exhibit the most therapeutically beneficial effect via modulating catalytic activity or expression levels of disease-associated enzymes. The present study is focused on CA VI isoform as a drug target due to the link of CA VI with several pathologies19,20,22. Even though several studies on the design of compounds targeting CA VI have been reported40,44,45, CA VI-selective inhibitor has not been discovered so far. Therefore, there is an interest in inhibitors with high affinity and selectivity against CA VI which would be crucial to reveal biological function of CA VI.

During preclinical development, numerous high-throughput screening assays are employed to design and optimize hits toward a target protein. Therefore, in vitro techniques require high quantities of recombinant proteins for the proper evaluation of compound quality, efficacy, and safety before testing in humans. Despite recent advances in molecular sciences, difficulties in the production of recombinant proteins in large scale are observed. Our previous study40 indicated low yield of CA VI from E. coli. Here we have presented a strategy to apply CA VI-mimic as CA VI model protein for the investigation on enzymatic inhibition and inhibitor binding thermodynamics. The CA VI-mimic was designed via site-directed mutagenesis from CA II by introducing five point mutations, such as A65T, N67Q, F130Y, V134Q, and L203T. Such approach to obtain CA protein based on the CA II mutant for the search of CA-selective inhibitors has been successfully applied previously. It was due to troubles to obtain sufficient amounts of recombinant CA isoforms and enabled by high structural homology between human CAs. McKenna’s group reported a number of structural studies on CA IX-mimic based on CA II mutant with 2 mutations (S65A, Q67N)46–48, 7 mutations (A65S, N67Q, E69T, I91L, F131V, K170E, L204A)49–51 or 8 mutations (A9K, S65A, Q67N, T69E, L91I, V131F, E170K, A204L)52. Our group also published the exploration on inhibition parameters and binding thermodynamics via the application of CA IX-mimic as CA II mutant with 6 mutations (S65A, Q67N, L91I, V130F, L134V, A203L) and CA XII-mimic as CA II mutant with 6 mutations (S65A, K67N, T91I, A130F, S134V, N203L)53. The significant findings of the listed studies promoted the present investigation of CA II mutant mimicking CA VI. Over 10-fold higher purification yield of CA VI-mimic compared to CA VI from E. coli allowed kinetic, thermodynamic, and structural analyses of 43 benzenesulfonamides binding to CA VI-mimic. Even though the most tested inhibitors exhibited moderate affinities towards CA VI-mimic, this study provided insight into the structure-based design of inhibitors with better affinity and selectivity towards CA VI.

The observed kinetic parameters of CA VI and CA VI-mimic are consistent with previous works. The determined catalytic constant of CA VI compares reasonable well to published kcat value (3.4 × 105 s−1)44. The difference of kcat values most likely arise from the uncertain CO2 concentration in the previous work. The CA VI-mimic had the same catalytic activity as CA II (kcat – 6.0 × 105 s−1) and confirmed previously published results that A65, N67, F130, V134, L203 amino acids in the active site of CA II are not important for catalytic activity54–56. Three times higher catalytic activity of CA VI-mimic than CA VI is an advantage in measuring nanomolar inhibition constants by SFA, because similar to all enzymatic methods it is limited by both CA activity and concentration26.

The relevance of protonation-deprotonation reactions occurring additionally upon inhibitor binding to CA has been reviewed by several groups57,58. Such protonation events have been recently confirmed by neutron crystallography59,60. To generate compounds with great affinities by rational design, it is essential to understand the structural reasons for the changes in binding affinities of the investigated compounds towards the target. Only intrinsic parameters subtract the contribution of protonation reactions occurring in conjunction with the binding reaction between the CA and inhibitor. In the present study, nonfluorinated benzenesulfonamides exhibited stronger intrinsic and weaker observed binding affinity than corresponding fluorinated compounds. This result is in line with the previous investigation34, emphasizing the impact of fluorine electronegativity on the lowering of the pKa of inhibitor sulfonamide group but not the direct recognition of CA VI-mimic surface. The diminished pKa of fluorinated inhibitors led to the elevated observed affinity due to the increased fraction of inhibitor in the deprotonated form that bound to CA VI-mimic with the protonated zinc-bound hydroxide ion in the active site. Furthermore, substituents at ortho and para, but not meta positions were identified to be significant for the molecular recognition between the compound and CA VI. However, ortho and meta-substituted benzenesulfonamides have been recently shown to act as tight CA IX binders32. Therefore, such findings confirmed that intrinsic, but not observed parameters should be applied to analyze the dependence of binding efficiency on compound chemical structures, thereby allowing important structure-thermodynamics correlations to design CA-isoform selective inhibitors.

Inhibitor binding affinity can be significantly affected by structural properties of CA VI which have been widely investigated. The crystal structure of recombinant CA VI catalytic domain, lacking signal sequence and C-terminal region, has revealed its dimeric arrangement with the active sites of monomers facing each other and directed towards the center of the dimer61. Interestingly, the recent study62 has indicated that pentraxin domain (PTX) is present in non-mammalian CA VI, whereas PTX-coding exon is not found in mammalian CA6 gene most likely due to rearrangements occurring upon the duplication of the adjacent glucose transporter genes. Instead of the PTX domain, mammalian CA VI contains a C-terminal region of at least 25 residues which is not detected in other vertebrate CA isoforms. This part of CA VI may be important to form oligomers and bind other proteins affecting CA VI enzymatic activity or causing biological effect as a consequence of CA VI-protein interactions. Therefore, in vitro and in vivo studies on targeting CA VI can yield discrepancies in results because of the structural differences between recombinant CA VI applied for inhibitor screening and endogenous CA VI of live model organisms, such as mice or zebrafish.

The combination of data obtained from enzymatic inhibition and biophysical binding methods, such as FTSA and ITC, significantly strengthens the conclusions of compound structure-activity relationships. Since techniques are based on different strategies to characterize inhibitor efficacies, the precision and accuracy of the measurements are necessary to reliably select the most potent and strongest inhibitors/binders. The uncertainty and repeatability of FTSA42 and ITC63,64 measurements have been previously discussed. Furthermore, correlation between the affinities determined by FTSA and SFA or FTSA and ITC have been recently reported26,58 and confirmed in the present study. Therefore, both enzymatic inhibition and biophysical binding techniques are necessary for precise identification of inhibitors with great affinity and selectivity towards the particular CA isoform, thereby leading to the success in clinical development.

In conclusion, this study on site-directed mutagenesis of residues in the active site of CA II to resemble CA VI gave clues to the basis for isoform specificity of benzenesulfonamides towards CA VI over CA II. The characterization of numerous properties, such as kinetics of binding, inhibition profiles and the mechanism of action, provided the deeper insight into the efficacy of CA VI-targeting inhibitors. This in vitro step is crucial because only sufficiently characterized compound can result in the success on translating experimental data to a clinical disease setting. Moreover, the present kinetic, thermodynamic, and structural information is important for experiments in silico, such as machine learning, when current binding information will be determined, filtered, and extracted.

Methods

Synthesis of CA inhibitors

The synthesis of CA inhibitors has been previously described65–68. EZA, MZM and TFS were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and were used without further purification.

Production of CA VI-mimic protein

The structural superpositions of proteins for Figs 1D and 6(A–D) were performed using UCSF Chimera v. 1.1269. The residues within 5 Å from the typical CA II inhibitor in PDB entry 3M96 in both isoforms were analyzed, and five residues which were different between the isoforms were selected to create CA VI-mimic. The structure-based alignment was generated using PROMALS3D web server70. The sequence alignment figure was prepared using TeXshade package71.

The expression vector pET15b-CA II72, encoding full length CA II (1-260), was used in site-directed mutagenesis. The residues located in CA II active site, A65, N67, F130, V134, and L203, were replaced to T, Q, Y, Q, and T, respectively. For each mutagenesis reaction two oligonucleotide primers (sense and antisense) with target mutation were used: A65T_s: 5‘CTC AAC AAT GGT CAT ACT TTC AAC GTG GAG3’ and A65T_a: CTC CAC GTT GAA AGT ATG ACC ATT GTT GAG; N67Q_s: CAA TGG TCA TAC TTT CCA GGT GGA GTT TGA TGA C and N67Q_a: GTC ATC AAA CTC CAC CTG GAA AGT ATG ACC ATT G; F130Y_s: CCA AAT ATG GGG ATT ATG GGA AAG CTG TGC AG and F130Y_a: CTG CAC AGC TTT CCC ATA ATC CCC ATA TTT GG; V134Q_s: GAT TAT GGG AAA GCT CAG CAG CAA CCT GAT GG and V134Q_a: CCA TCA GGT TGC TGC TGA GCT TTC CCA TAA TC; L203T_s: GAC CAC CCC TCC TCT TAC GGA ATG TGT GAC CTG and L203T_a: CAG GTC ACA CAT TCC GTA AGA GGA GGG GTG GTC. PCR was carried out with high fidelity Pfu DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), except V134Q created with Phusion DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Composition of PCR: 1× polymerase buffer, 50 ng template DNA, 0.2 mM dNTPmix, 125 ng each sense and antisense primer, and 1.5 U DNA polymerase. Thermal cycling conditions: initial denaturation – 95 °C for 10 min, then 18 cycles: 95 °C for 3 min, annealing – 66 °C (A65T and F130Y), 63 °C (N67Q), 71 °C (V134Q), or 72 °C (L203T) for 2 min, extension – 72 °C for 8 min, final extension – one time 72 °C for 10 min. After temperature cycling, PCR product was treated with Dpn I restriction endonuclease in order to digest the parental DNA template and to select new synthesized mutated DNA73. The mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Expression of CA VI-mimic protein was carried out in E. coli BL21(DE3) strain. Transformed cells colony was transferred to LB medium, containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin, grown at 37 °C and 220 rpm for 16 h. Then the saturated culture was diluted (1:50) in fresh LB medium, containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin and 60 µM ZnSO4 and grown to OD600 ≈ 0.8. The expression of CA VI-mimic protein was induced with 0.2 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) and 0.4 mM ZnSO4. The cells were grown over night at 19 °C, 220 rpm and harvested by centrifugation at 4000 g for 20 min at 4 °C.

The biomass was suspended in the lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, 0.15 M NaCl, and 1 mM PMSF, pH 7.4), incubated at 4 °C for 60 min and then disrupted by sonication. Debris of cells and insoluble proteins precipitated after centrifugation at 30 000 g for 25 min. The soluble CA VI-mimic protein was purified using a metal chelate and CA-affinity chromatography. For the metal chelate chromatography the column was equilibrated with 20 mM HEPES, 0.15 M NaCl (pH 7.4). For elution of CA VI-mimic protein, solution composed of 20 mM HEPES, 0.15 M NaCl, and 0.2 M imidazole (pH 7.4) was used. Eluted protein was purified using a CA-affinity column containing p-aminomethylbenzene sulfonamide-agarose (Sigma-Life Science Aldrich). Sorbent was equilibrated with 20 mM HEPES, 0.15 M NaCl (pH 7.4). For the protein elution, solution composed of 0.1 M sodium acetate and 0.5 M sodium perchlorate (pH 5.6) was used. Eluted CA VI-mimic protein was dialyzed into storage buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 0.05 M NaCl, pH 7.4, and stored at −80 °C.

The purity of CA VI-mimic protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Protein concentrations were determined by UV-vis spectrophotometry using extinction coefficient ɛ280 = 51910 M−1 cm−1 and confirmed by standard Bradford method. Molecular mass of CA VI-mimic protein was confirmed by Mass spectrometer: observed – 29192.4 Da, theoretically predicted – 29323.0 Da. The difference is due to Met residue removed during production.

Enzymatic activity and inhibition by SFA

Enzymatic activity and inhibition experiments were performed using an Applied Photophysics SX.18MV-R stopped-flow spectrophotometer at 23 °C. Saturated CO2 solution was prepared by bubbling the CO2 gas in Milli-Q water at 23 °C for 1 h. The concentration of CO2 was determined using a model described previously26.

Catalytic constants kcat and Michaelis constants KM of CA VI and CA VI-mimic were determined in a pH range from 6.0 to 8.4 using 25 mM buffer and 30–300 µM indicator systems with similar pKa values: MES (pKa 6.1) and Bromocresol Purple (pKa 6.4, λ - 590 nm, pH 6.0–6.4), MOPS (pKa 7.2) and Bromothymol Blue (pKa 7.1, λ - 615 nm, pH 6.8–7.1), HEPES (pKa 7.5) and Phenol Red (pKa 7.5, λ - 557 nm, pH 7.2–7.8), TRIS (pKa 8.06) and m-Cresol Purple (pKa 8.3, λ - 575 nm, pH 8.0–8.4). CA VI and CA VI -mimic concentration was 50–100 nM. The ionic strength of solution was maintained at 0.2 M by the addition of sodium sulfate. Maximal velocities vmax were obtained using Lineweaver-Burk coordinates, and kcat, pKa values were determined using single ionization model:

Enzyme inhibition experiments were performed using 25 mM HEPES buffer containing 0.2 M sodium sulfate and 50 µM Phenol Red indicator, pH 7.5. Enzyme concentration was 10–30 nM for CA II, and 50 nM for CA VI and 50–107 nM CA VI-mimic. Inhibitor concentration was 0–20 µM in <0.2% DMSO. Raw curves were fitted using a single exponential model and the inhibition constants were determined using Morrison equation74,75:

where [CA] is the total concentration of the active CA molecules, [I] is the total added inhibitor concentration, and IC50 is the concentration of inhibitor that achieves 50% inhibition of enzymatic activity. A dose-response curve was fitted using fixed CA concentration and assuming that it is equal to the active enzyme concentration.

Inhibitor binding by FTSA

FTSA measurements were performed using a Corbett Rotor-Gene 6000 (Qiagen Rotor-Gene Q) instrument using the blue channel (excitation 365 ± 20 nm, detection 460 ± 15 nm). Samples contained 10 µL of 10 µM CA VI-mimic protein, 10 µL of 0–200 µM inhibitor in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 containing 100 mM NaCl, 50 µM solvatochromic dye 8-anilino-1-naphthalene sulfonate (ANS) and a final DMSO concentration of 2%. The applied heating rate was 1 °C/min. The pH dependence of the observed binding constant was measured in universal buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM sodium acetate, 25 mM sodium borate at pH 5.0–10.0. Data were fitted and analyzed as previously described72,76. Experiments were repeated at least twice.

Inhibitor binding by ITC

ITC measurements were performed using a VP-ITC instrument (Microcal Inc., Northampton, USA) with 1.4 mL of 4–6 µM CA VI-mimic protein solution in the cell and 300 µL of 40–60 µM ligand solution in the syringe. A typical experiment consisted of 25–30 injections (10 µL each) added at 200–240 s intervals. In order to determine the pH dependence of the observed binding enthalpy, experiments were performed at 25 °C in 50 mM phosphate or 50 mM TRIS buffer containing 100 mM NaCl at pH 5.0–10.0 with a final DMSO concentration of 1%, equal in the syringe and the cell. Data were integrated, fitted and analyzed as previously described77. Experiments were repeated at least twice.

Calculation of the intrinsic thermodynamics

The enzymatic or biophysical assays allow the determination of observed inhibitor affinity for CA. However, observed parameters depend on buffer or pH. Therefore, observed values are only relevant for the comparison of inhibitor binding affinities towards the target using the same experimental conditions and should not be used in structure-thermodynamics correlations in drug design.

Several protonation events take place upon the interaction between the inhibitor and CA: protonation of zinc-bound hydroxide in the active site of CA, deprotonation of inhibitor sulfonamide group, bond formation between CA and inhibitor, and compensating protonation-deprotonation reactions of buffer. To develop compounds with great affinities in the rational drug design, intrinsic parameters must be determined by subtracting the contribution of protonation reactions occurring in the conjunction with the inhibitor binding to CA58.

The parameter of Kd_intr is directly related to Kd_obs and fractions of deprotonated sulfonamide-based inhibitor and CA with protonated zinc-bound hydroxide (water molecule) in the active site .

The fractions of binding-ready inhibitor and CA depend on the pKa of sulfonamide amino group (pKa_SA) and the pKa of water molecule in the active site of CA (pKa_CA), respectively.

The intrinsic Gibbs energy change () is associated with the change in Kd_intr for the binding reaction.

The Kd_intr values for the tested benzenesulfonamide binding to CA VI-mimic were calculated using the pKa of 7.0 for CA VI-mimic at 37 °C.

The was measured by ITC as the sum of enthalpies caused by inhibitor binding to CA and protonation events, such as protonation enthalpies of buffer (), sulfonamide inhibitor (), and hydroxide bound to zinc in the active site of CA ():

where is the number of protons released from the inhibitor to buffer, is the number of protons bound to zinc-bound hydroxide of CA, and is the sum of uptaken or released protons by buffer. The enthalpy of protonation of TRIS and sodium phosphate buffers at 25 °C is equal to −47.4 kJ/mol and −5.1 kJ/mol, respectively78.

Crystallization

The CA VI-mimic was concentrated by ultrafiltration to 19 mg/mL. Crystallization condition (buffer) was 0.1 M sodium BICINE (pH 9.0), 0.2 M ammonium sulfate and 2 M sodium malonate (pH 7.0). The ligand solutions for crystal soaking were made by mixing of 50 μL of corresponding reservoir solution and 1 μL of 50 mM ligand solution (in DMSO).

Data collection and crystallographic structure determination

Three datasets of X-ray diffraction (CA VI-mimic in complex with inhibitor 14 (VD10-50), 25 (VD11-4-2), and EZA) were collected at the EMBL beamline P14. The datasets were processed by XDS program79. The molecular replacement was made by MOLREP program80 using as initial model 4HT0. The 3D models of compounds were created by AVOGADRO program81. The library files which contain complete chemical and geometric descriptions of compounds were created using LIBCHECK program82,83. The models were prepared using COOT84 and refined using REFMAC85. All represented graphics were made using Pymol programs (PyMOL, version 1.8.4.0). Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited to the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB). The PDB access codes are listed in Table 3.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Gleb Bourenkov for the help with data collection at P14 EMBL beamline at PETRA III ring of the DESY synchrotron. The access to the beamline was supported by iNEXT (grant number 653706) funded by the Horizon 2020 program of the European Commission. The study was also supported by the grant S-MIP-17-87 from the Research Council of Lithuania.

Author Contributions

J.K., J.S., V.K., A.S., M.T., S.P. and D.M. participated in the conception or design of the study; J.K. produced recombinant proteins, carried out biophysical assays and analyzed thermodynamic parameters; V.K. performed computational modelling; J.S. carried out enzymatic activity and inhibition measurements; A.S. and E.M. were responsible for X-ray crystallographic analysis; J.K. wrote the first version of manuscript; J.K., V.K., J.S., A.S., E.M., M.T., S.P. and D.M. contributed to manuscript drafting and approved the final version of manuscript.

Competing Interests

D.M. declares that he has patents and patent applications pending on CA inhibitors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-49094-0.

References

- 1.Meldrum N, Roughton F. Some properties of carbonic anhydrase, the CO2 enzyme present in blood. J Physiol. 1932;75:15–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frost SC. Physiological functions of the alpha class of carbonic anhydrases. Subcell. Biochem. 2014;75:9–30. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-7359-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aggarwal M, Boone CD, Kondeti B, McKenna R. Structural annotation of human carbonic anhydrases. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2013;28:267–277. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2012.737323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mincione F, et al. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: design of thioureido sulfonamides with potent isozyme II and XII inhibitory properties and intraocular pressure lowering activity in a rabbit model of glaucoma. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:3821–3827. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thiry A, Dogné J-M, Supuran CT, Masereel B. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors as anticonvulsant agents. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7:855–864. doi: 10.2174/156802607780636726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scozzafava A, Supuran CT, Carta F. Antiobesity carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: a literature and patent review. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents. 2013;23:725–735. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2013.790957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mboge, M. Y., Mahon, B. P., McKenna, R. & Frost, S. C. Carbonic Anhydrases: Role in pH Control and Cancer. Metabolites8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Alterio V, Di Fiore A, D’Ambrosio K, Supuran CT, De Simone G. Multiple Binding Modes of Inhibitors to Carbonic Anhydrases: How to Design Specific Drugs Targeting 15 Different Isoforms? Chem. Rev. 2012;112:4421–4468. doi: 10.1021/cr200176r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinard Melissa A., Mahon Brian, McKenna Robert. Probing the Surface of Human Carbonic Anhydrase for Clues towards the Design of Isoform Specific Inhibitors. BioMed Research International. 2015;2015:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2015/453543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murakami H, Sly WS. Purification and characterization of human salivary carbonic anhydrase. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:1382–1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kivelä J, et al. Secretory carbonic anhydrase isoenzyme (CA VI) in human serum. Clin. Chem. 1997;43:2318–2322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karhumaa P, et al. The identification of secreted carbonic anhydrase VI as a constitutive glycoprotein of human and rat milk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11604–11608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121172598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leinonen JS, Saari KA, Seppänen JM, Myllylä HM, Rajaniemi HJ. Immunohistochemical demonstration of carbonic anhydrase isoenzyme VI (CA VI) expression in rat lower airways and lung. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2004;52:1107–1112. doi: 10.1369/jhc.4A6282.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaseda M, Ichihara N, Nishita T, Amasaki H, Asari M. Immunohistochemistry of the bovine secretory carbonic anhydrase isozyme (CA-VI) in bovine alimentary canal and major salivary glands. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2006;68:131–135. doi: 10.1292/jvms.68.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan P, et al. Gene expression profiling in the submandibular gland, stomach, and duodenum of CAVI-deficient mice. Transgenic Res. 2011;20:675–698. doi: 10.1007/s11248-010-9441-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patrikainen MS, Pan P, Barker HR, Parkkila S. Altered gene expression in the lower respiratory tract of Car6 (−/−) mice. Transgenic Res. 2016;25:649–664. doi: 10.1007/s11248-016-9961-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patrikainen M, Pan P, Kulesskaya N, Voikar V, Parkkila S. The role of carbonic anhydrase VI in bitter taste perception: evidence from the Car6−/− mouse model. J Biomed Sci. 2014;21:82. doi: 10.1186/s12929-014-0082-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melis M, et al. The gustin (CA6) gene polymorphism, rs2274333 (A/G), as a mechanistic link between PROP tasting and fungiform taste papilla density and maintenance. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kivela J, Parkkila S, Parkkila AK, Leinonen J, Rajaniemi H. Salivary carbonic anhydrase isoenzyme VI. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1999;520(Pt 2):315–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.t01-1-00315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimoto M, Kishino M, Yura Y, Ogawa Y. A role of salivary carbonic anhydrase VI in dental plaque. Arch. Oral Biol. 2006;51:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parkkila S, et al. Salivary carbonic anhydrase protects gastroesophageal mucosa from acid injury. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1997;42:1013–1019. doi: 10.1023/A:1018889120034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hassan MI, Shajee B, Waheed A, Ahmad F, Sly WS. Structure, function and applications of carbonic anhydrase isozymes. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:1570–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pastorek J, Pastorekova S. Hypoxia-induced carbonic anhydrase IX as a target for cancer therapy: From biology to clinical use. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2015;31:52–64. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibbons BH, Edsall JT. Rate of hydration of carbon dioxide and dehydration of carbonic acid at 25 degrees. J. Biol. Chem. 1963;238:3502–3507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khalifah RG. The carbon dioxide hydration activity of carbonic anhydrase. I. Stop-flow kinetic studies on the native human isoenzymes B and C. J. Biol. Chem. 1971;246:2561–2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smirnovienė J, Smirnovas V, Matulis D. Picomolar inhibitors of carbonic anhydrase: Importance of inhibition and binding assays. Anal. Biochem. 2017;522:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kranz JK, Schalk-Hihi C. Protein thermal shifts to identify low molecular weight fragments. Meth. Enzymol. 2011;493:277–298. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381274-2.00011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niesen FH, Berglund H, Vedadi M. The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2212–2221. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matulis D, Kranz JK, Salemme FR, Todd MJ. Thermodynamic stability of carbonic anhydrase: measurements of binding affinity and stoichiometry using ThermoFluor. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5258–5266. doi: 10.1021/bi048135v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rogez-Florent T, et al. Label-free characterization of carbonic anhydrase-novel inhibitor interactions using surface plasmon resonance, isothermal titration calorimetry and fluorescence-based thermal shift assays. J. Mol. Recognit. 2014;27:46–56. doi: 10.1002/jmr.2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garbett NC, Chaires JB. Thermodynamic studies for drug design and screening. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2012;7:299–314. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2012.666235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zubrienė A, et al. Intrinsic Thermodynamics and Structures of 2,4- and 3,4-Substituted Fluorinated Benzenesulfonamides Binding to Carbonic Anhydrases. ChemMedChem. 2017;12:161–176. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201600509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linkuvienė V, et al. Intrinsic thermodynamics of inhibitor binding to human carbonic anhydrase IX. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 2016;1860:708–718. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zubrienė A, et al. Intrinsic thermodynamics of 4-substituted-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorobenzenesulfonamide binding to carbonic anhydrases by isothermal titration calorimetry. Biophys. Chem. 2015;205:51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baranauskienė L, Matulis D. Intrinsic thermodynamics of ethoxzolamide inhibitor binding to human carbonic anhydrase XIII. BMC Biophys. 2012;5:12. doi: 10.1186/2046-1682-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosano, G. L. & Ceccarelli, E. A. Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli: advances and challenges. Front Microbiol5 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Jia, B. & Jeon, C. O. High-throughput recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli: current status and future perspectives. Open Biol6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Gopal GJ, Kumar A. Strategies for the production of recombinant protein in Escherichia coli. Protein J. 2013;32:419–425. doi: 10.1007/s10930-013-9502-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Idicula-Thomas S, Balaji PV. Understanding the relationship between the primary structure of proteins and its propensity to be soluble on overexpression in Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 2005;14:582–592. doi: 10.1110/ps.041009005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kazokaitė J, Milinavičiūtė G, Smirnovienė J, Matulienė J, Matulis D. Intrinsic binding of 4-substituted-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorobenezenesulfonamides to native and recombinant human carbonic anhydrase VI. FEBS J. 2015;282:972–983. doi: 10.1111/febs.13196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morkūnaitė V, et al. Intrinsic thermodynamics of sulfonamide inhibitor binding to human carbonic anhydrases I and II. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2015;30:204–211. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2014.908291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cimmperman, P. & Matulis, D. Chapter 8:Protein Thermal Denaturation Measurements via a Fluorescent Dye. In Chapter 8:Protein Thermal Denaturation Measurements via a Fluorescent Dye 247–274 (2011).

- 43.Holdgate GA, Meek TD, Grimley RL. Mechanistic enzymology in drug discovery: a fresh perspective. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2018;17:115–132. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nishimori I, et al. Carbonic anhydrase activators: the first activation study of the human secretory isoform VI with amino acids and amines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:5351–5357. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winum J-Y, Montero J-L, Vullo D, Supuran CT. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: glycosylsulfanilamides act as subnanomolar inhibitors of the human secreted isoform VI. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2009;74:636–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tars K, et al. Sulfocoumarins (1,2-Benzoxathiine-2,2-dioxides): A Class of Potent and Isoform-Selective Inhibitors of Tumor-Associated Carbonic Anhydrases. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:293–300. doi: 10.1021/jm301625s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Genis C, et al. Design of a carbonic anhydrase IX active-site mimic to screen inhibitors for possible anticancer properties. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1322–1331. doi: 10.1021/bi802035f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sippel KH, et al. Characterization of Carbonic Anhydrase Isozyme Specific Inhibition by Sulfamated 2-Ethylestra Compounds. Lett. Drug Des. Discovery. 2011;8:1–25. doi: 10.2174/157018011796576105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moeker J, et al. Structural Insights into Carbonic Anhydrase IX Isoform Specificity of Carbohydrate-Based Sulfamates. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2014;57:8635–8645. doi: 10.1021/jm5012935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pinard MA, Aggarwal M, Mahon BP, Tu C, McKenna R. A sucrose-binding site provides a lead towards an isoform-specific inhibitor of the cancer-associated enzyme carbonic anhydrase IX. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun. 2015;71:1352–1358. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X1501239X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahon BP, et al. Saccharin: A lead compound for structure-based drug design of carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 2015;23:849–854. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pinard MA, Boone CD, Rife BD, Supuran CT, McKenna R. Structural study of interaction between brinzolamide and dorzolamide inhibition of human carbonic anhydrases. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:7210–7215. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dudutienė V, et al. Discovery and characterization of novel selective inhibitors of carbonic anhydrase IX. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:9435–9446. doi: 10.1021/jm501003k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krebs JF, Fierke CA. Determinants of catalytic activity and stability of carbonic anhydrase II as revealed by random mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:948–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Behravan G, Jonasson P, Jonsson BH, Lindskog S. Structural and functional differences between carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes I and II as studied by site-directed mutagenesis. Eur. J. Biochem. 1991;198:589–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sjöblom B, Polentarutti M, Djinovic-Carugo K. Structural study of X-ray induced activation of carbonic anhydrase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:10609–10613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904184106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krishnamurthy VM, et al. Carbonic anhydrase as a model for biophysical and physical-organic studies of proteins and protein-ligand binding. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:946–1051. doi: 10.1021/cr050262p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Linkuvienė, V. et al. Thermodynamic, kinetic, and structural parameterization of human carbonic anhydrase interactions toward enhanced inhibitor design. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics51 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Kovalevsky A, et al. ‘To Be or Not to Be’ Protonated: Atomic Details of Human Carbonic Anhydrase-Clinical Drug Complexes by Neutron Crystallography and Simulation. Structure. 2018;26:383–390.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koruza Katarina, Mahon Brian P., Blakeley Matthew P., Ostermann Andreas, Schrader Tobias E., McKenna Robert, Knecht Wolfgang, Fisher S. Zoë. Using neutron crystallography to elucidate the basis of selective inhibition of carbonic anhydrase by saccharin and a derivative. Journal of Structural Biology. 2019;205(2):147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2018.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pilka ES, Kochan G, Oppermann U, Yue WW. Crystal structure of the secretory isozyme of mammalian carbonic anhydrases CA VI: implications for biological assembly and inhibitor development. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;419:485–489. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Patrikainen MS, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel zebrafish (Danio rerio) pentraxin-carbonic anhydrase. PeerJ. 2017;5:e4128. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Linkuvienė V, Krainer G, Chen W-Y, Matulis D. Isothermal titration calorimetry for drug design: Precision of the enthalpy and binding constant measurements and comparison of the instruments. Anal. Biochem. 2016;515:61–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paketurytė Vaida, Linkuvienė Vaida, Krainer Georg, Chen Wen-Yih, Matulis Daumantas. Repeatability, precision, and accuracy of the enthalpies and Gibbs energies of a protein–ligand binding reaction measured by isothermal titration calorimetry. European Biophysics Journal. 2018;48(2):139–152. doi: 10.1007/s00249-018-1341-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dudutienė V, et al. Functionalization of fluorinated benzenesulfonamides and their inhibitory properties toward carbonic anhydrases. ChemMedChem. 2015;10:662–687. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zubrienė A, et al. Benzenesulfonamides with benzimidazole moieties as inhibitors of carbonic anhydrases I, II, VII, XII and XIII. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2014;29:124–131. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2012.757223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dudutienė V, et al. 4-Substituted-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorobenzenesulfonamides as inhibitors of carbonic anhydrases I, II, VII, XII, and XIII. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:2093–2106. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Čapkauskaitė E, et al. Benzenesulfonamides with pyrimidine moiety as inhibitors of human carbonic anhydrases I, II, VI, VII, XII, and XIII. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 2013;21:6937–6947. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pei J, Kim B-H, Grishin NV. PROMALS3D: a tool for multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2295–2300. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Beitz E. TeXshade: shading and labeling of multiple sequence alignments using LaTeX2e. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:135–139. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cimmperman P, et al. A quantitative model of thermal stabilization and destabilization of proteins by ligands. Biophys. J. 2008;95:3222–3231. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.134973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carrigan PE, Ballar P, Tuzmen S. Site-directed mutagenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011;700:107–124. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-954-3_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Morrison JF. Kinetics of the reversible inhibition of enzyme-catalysed reactions by tight-binding inhibitors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1969;185:269–286. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(69)90420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Williams JW, Morrison JF. The kinetics of reversible tight-binding inhibition. Meth. Enzymol. 1979;63:437–467. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)63019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]