Abstract

Indonesia’s oil palm expansion during the last two decades has resulted in widespread environmental and health damages through land clearing by fire and peat conversion, but it has also contributed to rural poverty alleviation. In this paper, we examine the role that decentralization has played in the process of Indonesia’s oil palm development, particularly among independent smallholder producers. We use primary survey information, along with government documents and statistics, to analyze the institutional dynamics underpinning the sector’s impacts on economic development and the environment. Our analysis focuses on revenue-sharing agreements between district and central governments, district splitting, land title authority, and accountability at individual levels of government. We then assess the role of Indonesia’s Village Law of 2014 in promoting rural development and land clearing by fire. We conclude that both environmental conditionality and positive financial incentives are needed within the Village Law to enhance rural development while minimizing environmental damages.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13280-018-1135-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Decentralization, Indonesia, Oil palm, Smallholders, Village Law

Introduction

Indonesia’s thriving oil palm sector is widely recognized for its detrimental contributions to tropical deforestation, land-based carbon emissions, fire-induced haze, and biodiversity loss. Fires used to clear land for oil palm in forested and peat areas—extending far beyond fires used for traditional slash-and-burn (swidden) agriculture in scope and duration—are responsible for much of the sector’s environmental damages, particularly in dry, El Niño years (Marlier et al. 2015; World Bank 2016; Alisjahbana and Busch 2017; Macdonald and Toth 2017). However, the positive impacts of oil palm expansion on rural development in Indonesia are generally less well appreciated by environmental scientists, despite a growing body of empirical studies documenting improvements in farmer incomes, assets, food security, and community livelihoods in regions where oil palm is grown (Rist et al. 2010; Cahyadi and Waibel 2016; Edwards 2017; Euler et al. 2017; Gatto et al. 2017). Here we examine the institutional dynamics underpinning both environmental and social change associated with Indonesia’s oil palm sector, and ask: What role has the radical shift toward decentralized governance since the end of President Suharto’s long-standing reign in 1998 played in these processes?

Indonesia’s decentralization reform, passed in 1999 and launched officially in 2001, was among the world’s most ambitious decentralization efforts to date, affecting over 210 million people from diverse cultural, ethnic, and economic backgrounds throughout the country’s massive archipelago (Firman 2010; Pepinski and Wihardja 2011; Burgess et al. 2012). Through favorable fiscal incentives to districts and ambiguous governmental authority over land titles and resource management, decentralization policies have helped fuel rapid oil palm growth in Indonesia, mainly through area expansion. More than three-fourths of the country’s palm oil production has come on line since decentralization policies were introduced, and most of the growth has occurred in the heavily forested, “outer” islands of Sumatra and Kalimantan that had not seen much economic and social development prior to 2000 (Directorate General of Estate Crops 2016). Although large plantations were the foundation of early industry growth and remain important today, smallholders have been by far the fastest growing subsector of oil palm planted area since decentralization began. Smallholder producers now account for roughly 40% of Indonesia’s total planted area of oil palm (Box 1).

| Box 1 Oil palm planted area in Indonesia by producer classification, 1970–2017 | |

|---|---|

|

Figure B1 shows the area planted to oil palm (‘000 ha) in Indonesia by private-sector companies (dark gray), state-owned plantations (medium gray) and smallholder producers (light gray). President Suharto (1967–1998) began to push investments in the oil palm sector shortly after his rise to power. At the time all of Indonesia’s oil palm land was owned by either the state government or private corporations; the minimum size for a forest exploitation permit was 50 000 ha, excluding local and small-scale oil palm operations (Arnold 2008). There were virtually no smallholder oil palm farmers until 1979, when Indonesia began the first of several programs designed to bring smallholders into the burgeoning oil palm industry. These programs are typically referred to as plasma schemes, borrowing a term from biology: private companies were given large land concessions to develop a central, “nucleus” oil palm estate. The nucleus company also developed adjacent land on behalf of local farmers, termed “plasma” smallholders. The partnership allowed smallholders to engage in oil palm production in spite of high capital and technology requirements that formed major barriers to entry. Smallholders were required to sell their fruit back to the nucleus company until development costs were repaid, offering the nucleus company greater economies of scale. Decentralization reforms, beginning after the resignation of Suharto, contributed to rapid oil palm expansion, especially among independent smallholders. The figure highlights the rise in the share of oil palm plantings by smallholders since the introduction of decentralization. 2017 Data are preliminary estimates.

Data source Directorate General of Estate Crops (2016)

|

The dramatic shift toward decentralized governance over financial and natural resources, coupled with the rising role of smallholders in the oil palm sector, have fundamentally altered Indonesia’s rural landscape since the turn of the century. In light of these transitions, the main goals of this paper are (1) to identify the processes that link decentralization to oil palm expansion in Indonesia, especially among smallholders,1 and (2) to assess the economic development and environmental outcomes of oil palm development under an increasingly decentralized governance structure. We begin by discussing the economic context for Indonesia’s oil palm boom, and then present our conceptual framework and methods for analyzing the role of decentralization in oil palm expansion. Our framework draws on Indonesia’s experience, as well as the experience of other countries around the world that have undergone various forms of political and economic decentralization. As in most studies of decentralization, it is difficult to disentangle the role of institutions from broader economic trends when assessing social and environmental outcomes, as the two are tightly interconnected (Bardhan 2002). Our aim is thus to explore the institutional variables that have contributed to Indonesia’s oil palm boom, not to assign causality.

Having laid the foundation, we examine, in greater detail, the features of decentralization in Indonesia’s governance structure that have facilitated rapid growth in oil palm production, particularly by independent smallholders. The Village Law of 2014 represents the country’s most recent phase of fiscal decentralization; by devolving economic authority of economic development to the local level, this law has major implications for both poverty alleviation and environmental outcomes throughout the country. We assess how the Village Law of 2014, as written, is likely to influence the social and environmental consequences of oil palm expansion, and what aspects of the Law could be adjusted to address not only economic goals but also sustainability objectives. We conclude with a perspective on the challenges that Indonesia continues to face—and some solutions that may be at hand—as the country grapples with misalignments in responsibilities, rewards, and policymaking authority among various levels of governance.

Indonesia’s booming oil palm sector

Palm oil is now the most-consumed vegetable oil worldwide, having recently replaced soy oil as the leader (Byerlee et al. 2017). In response to robust demand at home and abroad, Indonesia has invested heavily in the oil palm sector as a means of increasing foreign exchange revenue, supplying domestic vegetable oil markets, and alleviating rural poverty. Between 1990 and 2016, palm oil production in Indonesia rose from 2.4 million metric tons (MMT) to over 33 MMT, while the area planted with oil palms grew from 1.1 million hectares (ha) to over 11 million ha (Directorate General of Estate Crops 2016). Area expansion accounts for roughly 90% of the country’s production growth. Indonesia emerged as the world’s largest producer of crude palm oil (CPO) in 2006 and as the top exporter of CPO in 2008. It produces roughly half of the global output and exports about 85% of what it grows—worth around USD 21.3 thousand million in 2017 (Kementerian Pertanian n.d.).2

Rapid growth in Indonesia’s oil palm sector between 2000 and 2016 was driven by both economic and institutional factors. Currency devaluation and trade liberalization in the wake of the Asian financial crisis in 1997 supported the expansion in export-oriented agriculture in Indonesia (Rada and Regmi 2010; Byerlee et al. 2017). Population growth, income growth, and the introduction of biodiesel mandates in Indonesia and other large, consuming regions such as China, India, and the EU provided the impetus for growth in CPO demand and prices. Global biodiesel production grew at an annual rate of 23% on average between 2005 and 2015, reaching 35 thousand million liters in 2016. Indonesia maintains an aggressive agenda to develop palm-based biodiesel and currently has the world’s highest targeted blending mandate, set at B30 by 2020 (Naylor and Higgins 2017).3

CPO prices rose sharply in 2006, coinciding with the commodity boom involving energy and agriculture (Naylor and Falcon 2008, 2010). CPO prices then crashed with the global recession, and climbed again through mid-2011. Despite high price volatility, positive profit margins created private economic incentives for area expansion and investments in supply chain development, especially milling and refining facilities. High returns to both land and labor in oil palm relative to other tropical crops, such as rubber, also led many producers, large and small, to concentrate their efforts in the oil palm sector (Feintrenie et al. 2010; Budidarsono et al. 2012; Euler et al. 2017). Given the perennial nature of oil palm production—with harvests of palm oil beginning 3–5 years after planting and extending out for roughly 25 years before replanting is required to raise yields—it is not too surprising that Indonesia’s output has continued to rise since 2011 despite a downturn in real CPO prices. During this time, Indonesia has also deepened its decentralized governing structure down to the village scale. We now turn to the role of decentralization in oil palm development.

Framework of analysis

Decentralization policies have been introduced in the majority of developing economies throughout Asia, Latin America, and Africa since the 1970s, largely in response to failures in centralized governance from the post-independence era (Bardhan 2002; Ribot et al. 2006; Firman 2010). During the 1980s and 1990s, decentralization initiatives proliferated following the international debt crisis and the dissolution of the Soviet Republic (USSR), and were promoted widely by international development and finance agencies to improve economic performance, efficiency, equity, and accountability (World Bank 2000).

Indonesia introduced decentralization reforms fairly late in comparison to the rest of the Global South, yet the speed and scale of its reform was massive, as were its implications for resource-rich regions of the country. After three decades of centralized political and financial control under President Suharto (1967–1998), authority over fiscal management and natural resource use was largely transferred in 2001 from the central to district (kabupaten) level—encompassing nearly 300 diverse districts throughout the nation (Fitrani et al. 2005; Nasution 2016). In addition, democratic processes were supported through open elections and the participation of multiple political parties (Aspinall 2011). Governance authority has since devolved further to the local level through the Village Law of 2014 (Law 6/2014). The ongoing process of decentralization and democratization in Indonesia, while far from perfect, has fundamentally altered political and financial relationships among layers of governments (Aspinall and Fealy 2003; Hill 2014). Our main interest here is how the decentralization process has created incentives for extensive (rather than intensive) oil palm production, and how the pattern of oil palm expansion in a decentralized system has promoted rural development and affected environmental outcomes.

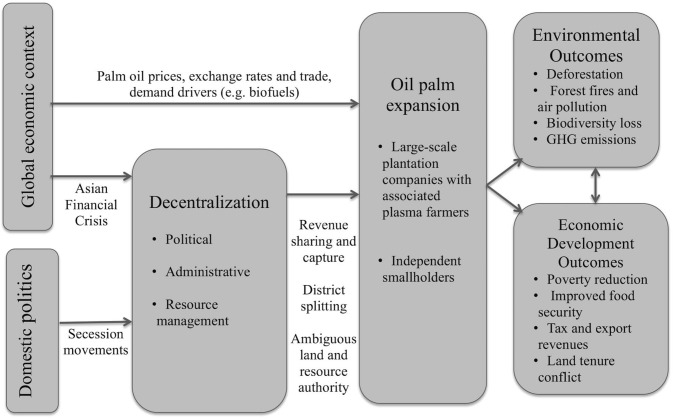

Figure 1 illustrates a simple conceptual framework for thinking about decentralization, oil palm development, and social/environmental impacts in Indonesia. In developing this framework, we build on an extensive literature on decentralization within the institutional and development economics fields, including Oates (1999), Manor (1999), Agrawal and Ribot (1999), and Bardhan (2002, 2016). We also draw on literature in the decentralization and resource management area, mainly as applied to governance and forest management both within and outside of Indonesia (see, e.g., McCarthy 2004; Resosudarmo 2004; Ribot et al. 2006; Palmer and Engel 2007; Firman 2010; Pepinski and Wihardja 2011; Pal and Wahhaj 2017).

Fig. 1.

Framework for assessing interactions between Indonesia’s decentralization and oil palm expansion

Like many other countries that had adopted decentralization policies earlier, pressure on the Suharto administration to reform came from economic and political forces external to the President’s central leadership (Fig. 1, left). In 1998, the Suharto government was mired in the economic fallout from the Asian financial crisis, and it faced increasing political pressure from regional secession movements. Similar to Uganda, decentralization policies in Indonesia were implemented in large part to promote social stability and to avert political disintegration, and the goals of reform were therefore not fully compatible with the stated economic goals of improved efficiency and equity (Aspinall and Fealy 2003; Fitrani et al. 2005; Ribot et al. 2006).

Decentralization policies are generally grouped in three categories—political, administrative, and resource management—and all apply to our analysis of Indonesia. Political decentralization represents some degree of democratization, where policies are designed to improve accountability between policymakers and constituents in their jurisdictions through election processes for political representatives. Administrative decentralization represents the transfer of public service and public finance responsibilities and funding capabilities (e.g., block grants) from central to lower levels of governance. Decentralization of resource management represents the transfer of rights and responsibilities for resource management, along with some degree of revenue capture, from central to local user groups and communities. The incentives that decentralization reform provide for extensive oil palm production are likely to depend on the specific laws surrounding revenue-sharing agreements for individual resources (e.g., forests versus plantation agriculture) and rules governing fiscal transfers between central to district governments. Laws governing land rights, forest conservation, and land clearing by fire under decentralization, as well as the enforcement of those laws, are also likely to influence the extent of oil palm expansion by large plantations and smallholders.

Experience from Indonesia and other developing countries shows that decentralization efforts are frequently compromised by weak administrative capacity, low funding support for resource management and service provision, poor political accountability, and the absence of a strong civil society needed to ensure local representation.4 These problems may be worsened by fiscal or political incentives that lead to spatial fragmentation of local governments (Grossman and Lewis 2014; Pierskalla 2016). As a consequence, decentralization reform often leads to local corruption, resource capture by local elites or the military, and the monopolization of governance roles by the elite, as seen in many forest-rich regions of Indonesia (McCarthy 2004; Burgess et al. 2012). Moreover, insufficient local capacity may allow central line ministries to retain control over valuable natural resources despite the promise of decentralization (Ribot et al. 2006). Understanding how such outcomes apply specifically to Indonesia’s oil palm expansion requires a close examination of the country’s decentralization laws and their enforcement, the topic we turn to after describing our research methods.

Methods

We conducted research in Jakarta and in five oil palm provinces across Sumatra and Kalimantan between March 2016 and February 2018. Information and data were obtained through key informant interviews, focus group discussions, and secondary data sources, following standard methods for qualitative data collection and analysis (Kvale 1996; see also McCarthy et al. 2012; Obidzinski et al. 2012). We also drew on more than 70 years of collective experience on Indonesia as an author team; our experience includes prior policy advising and field-based research in and on Indonesia. Our research was largely inductive in nature, drawing on personal interviews, official data, government reports, and evidence from published literature to infer the primary pathways by which decentralization has influenced smallholder oil palm expansion in Indonesia during the last two decades.

Our field research covered seven key stakeholder categories: Indonesia’s central government, regional governments, village governments, international development organizations, private-sector companies, NGO and research organizations, and smallholder oil palm farmers and rural community members. The methods used to collect data are described more fully in Appendix S1. The content of each interview was recorded in detailed field notes. Notes from each interview were analyzed independently, identifying key information and concepts. The individual notes were also analyzed in aggregate, during which time common themes emerged and differences between stakeholder groups or regional variations were identified. The large number of interviews, conducted across a diverse set of field sites, made it possible to identify common pathways of oil palm development despite the large variations across time, space, and actors. We also collected reports and official statistics during visits to government offices and from public government websites to augment and corroborate the information and data from personal interviews. We conducted a total of 86 key informant interviews and 17 focus group discussions that included 175 smallholder farmers and community members.

Indonesia’s decentralization

Indonesia had one of the world’s most highly centralized governments prior to the 1997/98 Asian financial crisis. Under President Suharto, strategic management of the oil palm sector, and most other natural resource industries, was essentially controlled by the central government. The vast majority of total government revenues went to the central government in Jakarta, including nearly all revenues derived from natural resource extraction. Regional governments, whose main function was to implement centrally mandated policies, relied on direct subsidies and conditional grants from the central government.5 These funds were generally allocated according to population and without consideration to the resource-richness of a region. Perversely, some of the most resource-rich regions of the country were also among the poorest. By the mid-1990s, provincial and district governments were advocating aggressively for greater regional autonomy. Regional governments vied for administrative control over natural resources and demanded that a greater share of earnings remain within the producing region (Barr et al. 2006).

At the time of President Suharto’s resignation in 1998, secession movements were gaining momentum throughout the country, raising concerns over whether Indonesia could survive as a unified nation. A key issue in virtually all the cases was the control over natural resources. In an effort to quell secession sentiments, the new government of President B. J. Habibie (formerly Suharto’s Vice President) introduced a set of decentralization policies in 1999, ushering in a new era of reform (dubbed “reformasi” by Indonesians and “big bang decentralization” by the international community). Over the next few years, the reform process shifted power away from the central government and toward regional leaders (Barr et al. 2006).

With decentralization, authority was devolved to regional governments except for “foreign policy, defense and security, judicial, monetary and fiscal, religious, and other areas.” Importantly, the list of “other areas” included “the efficient use of natural resources” (Law 22/1999 Article 7). The majority of responsibilities, including public works, health, education and culture, agriculture, communications, industry and trade, investment, environment, land affairs, cooperatives, and man power became obligations of district governments (Article 11). Provincial governments were largely skipped over due to concerns that providing provinces with too much authority could stoke separatism.

Although substantial administrative and fiscal authority shifted to district governments, central ministries such as agriculture, education, and forestry were retained, and these Ministers remained a part of the President’s Cabinet. Difficulties in coordinating the responsibilities of different layers of government were, and remain, a challenge. Local elections were introduced, ending the hierarchical formation of regional governments. In principle, district and village officials became downwardly accountable to their constituents through democracy rather than upwardly accountable to the central government in Jakarta (Barr et al. 2006), reflecting the process of political decentralization (Fig. 1).

Based on a synthesis of our field interviews, official reports, and published literature, we identify four specific features of this early decentralization process that have been particularly important for developments within Indonesia’s oil palm sector: new revenue-sharing agreements between central and regional governments, district splitting, ambiguous authority over land titles, and the lack of accountability over natural resource management. The first two features represent administrative decentralization processes, while the latter two reflect unresolved issues of natural resource decentralization (Fig. 1). Together, these features have contributed to unbridled growth in oil palm area, the rise of independent smallholders, widespread deforestation and land clearing by fire, and land tenure conflicts. The reforms have also resulted in significant increases in rural incomes and reductions in poverty within oil palm-producing districts, and have thus presented the most difficult type of environment-versus-development tradeoffs for Indonesia’s President and Parliament.

Revenue-sharing agreements

The introduction of new revenue-sharing laws was one of the most significant changes to come out of the decentralization process. Regional governments were given considerably more autonomy in managing their own budgets and were allowed to retain a much larger share of revenues generated within their districts, particularly from natural resource use. As an indication of the devolution of fiscal authority, regional public expenditures as a share of total national expenditures nearly doubled from 17% in 2000 to 31% in 2002 after decentralization laws took effect (World Bank 2003). In 2018, approximately 35% of the central budget is to be transferred to regional governments (Law 17/2017).

Two key revenue-sharing laws—Law 25/1999 on Revenue Sharing and Law 33/2004 on Fiscal Balance—stipulated how revenues from natural resources were to be shared between levels of government. While these laws covered forestry, fisheries, mining, and oil and gas, revenues earned from oil palm and other estate crops were not subject to revenue sharing. This omission directly propelled growth in oil palm production. Many district heads (bupatis) chose to allocate permits to agro-industrial plantations over timber operations because they could gain greater control in licensing and regulation of the agricultural sector and were not required to share revenues with the central government (Barr et al. 2006). In particular, bupatis preferred oil palm because it was consistently more profitable than other estate crops and awarded companies thousands of hectares of forest for development as a result (Feintrenie et al. 2010; Sayer et al. 2012).

An estimated two-thirds of Indonesia’s oil palm has been planted in previously forested areas, often associated with illegal burning or illegal logging (Carlson et al. 2013; Lawson et al. 2014; Macdonald and Toth 2017). In many cases forested areas were targeted over non-forested areas for concessions, as logging revenues during crop establishment provide a significant source of income for concession holders (Budidarsono et al. 2012). Timber revenues from oil palm concessions can even exceed those of actual timber concessions; forests can be clear-cut for oil palm establishment,6 while timber concessions are required to practice selective logging in accordance with Ministry of Forestry regulations (EIA 2014).

District splitting

In addition to new revenue-sharing arrangements, decentralization laws provided incentives for districts to split into multiple, smaller jurisdictions as a way to increase the per capita funding received from the central government.7 The total number of rural districts in Indonesia—which had remained largely static for decades—exploded in the years following decentralization, growing from 268 in 2000 to 416 in 2017 (Nasution 2016; Kementerian Dalam Negeri 2017). Block grants from the central government meant that a split district effectively received twice the per capita revenues as the original single district (Fitrani et al. 2005). District splitting also substantially increased the number of local government jobs and the magnitude of local rents (Bazzi and Gudgeon 2017).

District splitting has resulted in serious environmental challenges, particularly when it has involved ethnic fractionalization (Bazzi and Gudgeon 2017). Studies by Burgess et al. (2012) and MacDonald and Toth (2017) reveal that a single district split is estimated to increase the provincial deforestation rate by 8.2% and the number of forest fires by 4.3–6.7%. Evidence from these studies suggests that greater competition between districts, increased opportunities for corruption, and a lack of administrative capacity to enforce environmental laws are the main causes of escalated fires and deforestation as new districts are formed. Similar outcomes have been found in other tropical and Southeast Asian nations (Verbrugge 2015; Lipscomb and Mobarak 2017).

Ambiguous authority over land titling

Indonesian laws are often written ambiguously or in conflict with preexisting laws, and it is not uncommon to find discontinuities within individual laws (Barr et al. 2006; Arnold 2008). One of the foundational laws of decentralization, Law 22/1999 on Regional Governance, contained contradictory articles that allowed both central and district governments to claim control over natural resources (Articles 7 and 11). This set of articles also permitted multiple levels of government to claim authority over oil palm development. Both provincial and district governments have routinely given out permits for oil palm development since decentralization began—as have many village heads—often without consultation with one another or with the central government. This process has essentially created concessions that are sanctioned by one level of government but illegal according to another (Lawson et al. 2014; Potter 2015; Gaveau et al. 2016b).

Poor communication and coordination among levels of government has led to over-permitting of land for oil palm expansion. As one example, 1.4 million ha of land have been allocated to oil palm concessions in the Barito Selatan District of Central Kalimantan, despite the district’s total area being only 830 000 ha (Potter 2015). Concessions given to corporate plantations overlap one other; they also overlap with land claimed by smallholders and indigenous communities, giving rise to social conflict and local land disenfranchisement. Overlapping concessions create a “race to the bottom,” wherein each company clears and develops faster and more extensively than they otherwise would in order to strengthen its claim to an area and prevent competition from entering the region (Arnold 2008). Our field interviews and focus group conversations suggest that this practice extends to smallholders, who also clear land, mainly via fire, and plant oil palm for the purpose of establishing land claims.

Lack of accountability

Overlapping government claims have led to poor enforcement of land policy, particularly in remote regions of Indonesia. The central government currently plays a minor role in rural land monitoring, even in national parks that are technically under its jurisdiction. For example, in Tesso Nilo National Park (Riau Province, Sumatra), the Ministry of Forestry provides only 18 forest police to patrol an area of more than 80 000 ha (Potter 2015). Minimal enforcement, coupled with local economic interests in developing oil palm in protected areas, has allowed oil palm encroachment to extend to over 80% of Tesso Nilo’s total area (EoF 2016). Large multinational oil palm companies have also been complicit in land clearing within national parks (WWF-Indonesia 2013).

Similar situations play out across Indonesia: according to the Ministry of Forestry, half of Riau’s 4 million ha of oil palm planted area and the majority of plantations in Central Kalimantan could be considered illegal (Colchester et al. 2011; Antara News 2014). The share of Indonesian oil palm concessions that are considered illegal (due to improper or unlawful land clearing) is estimated to be as high as 80% by some definitions (Lawson et al. 2014). In the absence of central control, most rural land enforcement is carried out at the district level. Local and regional governments often lack the financial resources and administrative capacity to monitor and enforce environmental and land use laws. There is also an overwhelming push by regional leaders toward revenue generation at the expense of sustainable production and environmental protection (McCarthy and Zen 2010; Anderson et al. 2016).

Even in cases where district governments aim to promote sustainable oil palm development, rent-seeking behavior by local officials often stands in the way. Corruption has long been a problem in Indonesia dating back to the Suharto era and before, and it has persisted both in spite of and because of decentralized governance. In 2014, more than half of Indonesia’s district heads were thought to be under investigation for corruption (Kapoor 2014). Natural resource management and oil palm development have historically been targets for corruption as they provide major opportunities for rent seeking (e.g., CIFOR 2010; Sjarina et al. 2013; EIA 2014). Local officials regularly collect illegal levies for personal gain; for example, basic tasks like traffic control and paperwork (including paperwork for oil palm permitting) are seen as opportunities for rent seeking and patronage (McCarthy and Zen 2010; ICG 2012).8 The convoluted nature of decentralized oil palm governance provides opportunities for a large number of provincial, district, and local leaders to regulate and gain personally from the industry’s expansion.

The rise in independent smallholders

Indonesia’s political and economic decentralization process has coincided with the rising share of smallholder participation in the oil palm sector (Box 1). “Smallholders” encompass producers of widely varying plot sizes, although the average is around 2 ha each.9 Smallholders are typically separated into two categories defined by their initial development conditions: plasma smallholders who are affiliated with plantation companies and receive assistance during crop establishment, and independent smallholders who receive no assistance. In practice there is an array of business models and considerable ambiguity. The wide diversity of smallholder production systems for oil palm is evident from our field interviews, official reports, and published literature, as described throughout this section. Some farmers begin as plasma smallholders before severing ties with the company. Some smallholders are both independent and plasma farmers, using earnings from plasma plots to buy more land of their own (Cramb and McCarthy 2016). A growing class of absentee landowners further blurs the lines between smallholder and private companies (Jelsma et al. 2017).

Within this mix of smallholders, the share of independent producers has been increasing during the last decade. Independent smallholders currently account for roughly one third of Indonesia’s total planted area of oil palm (SPKS n.d.; Directorate General of Estate Crops 2016), and the area of oil palm under independent smallholder control is now roughly three times that of the area under plasma smallholder control. Growth in the independent smallholder subsector has been aided by the simultaneous increase in growth by multinational corporations. The rapid proliferation of corporate plantations and mills has greatly expanded areas that fall within mill catchment areas, opening up more land for potential smallholder oil palm development (Budidarsono et al. 2012).10 Growth in milling capacity creates a nearly inexhaustible demand for locally produced oil palm fruits (FFBs, fresh fruit bunches), thereby lowering the barrier to entry for smallholders.

According to a household survey conducted as part of the 2013 Indonesian Agricultural Census, 89% of oil palm-producing households operated without any formal partnership with private companies (BPS 2013). Instead, a variety of informal relationships have sprung up between mid-sized oil palm enterprises and independent smallholders during the last 15 years—relationships that are widely observed in the field but not well documented in the literature. Mill capacity is often substantially greater than what a given company’s own land can produce, and it therefore purchases FFB from independent smallholders to raise its mill throughput. Increased local FFB demand, in turn, induces more smallholders to enter the industry or expand production. The company thus gains direct access to greater volumes of FFB without being legally accountable for land clearing via fires or encroachment into forests.

This process has led to increased land clearing, both legal and illegal, in regions where oil palm is produced. Land clearing by independent smallholders has been facilitated by administrative decentralization and by unsolved issues of natural resource authority among different levels of government, as discussed in the previous section and depicted in Fig. 1. Our field interviews revealed that oil palm expansion of this nature has become significantly more common since 2010. There has been little effort to prevent smallholders from moving into undeveloped areas surrounding oil palm mills.

Regional and local governments frequently promote the expansion of oil palm as an engine of economic growth and poverty alleviation irrespective of its environmental impact (Edwards and Heiduk 2015; Anderson et al. 2016; Gatto et al. 2017). A number of empirical studies show that rising returns to land and labor in Indonesia’s oil palm sector have contributed directly and indirectly to gains in agricultural household expenditures and incomes (Alwarritzi et al. 2015; Cahyadi and Waibel 2016; Euler et al. 2017), wealth and assets (Susila 2004; Gatto et al. 2017), food security (Euler et al. 2017), and broader livelihoods (Feintrenie et al. 2010; Rist et al. 2010). At the community level, studies have also documented faster poverty reduction, consumption growth, and infrastructure development in areas where oil palm is cultivated (Susila 2004; Hunt 2010; Sayer et al. 2012; Gatto et al. 2017).

Despite increasing evidence from empirical analyses regarding the economic development benefits of oil palm expansion, rapid growth in the independent smallholder sector remains problematic. Independent smallholders typically have few options but to clear more land, usually by fire, in order to make ends meet or to improve their incomes. Their oil palm yields fall well below those of plasma smallholders, especially in regions where nucleus-plasma companies have not existed previously (Gatto et al. 2017). The yield gap, indicated in Table 1, reflects the limited access that most independent smallholders have to high-quality inputs (e.g., certified planting material and chemical fertilizers), credit, and cash (Samosir et al. 2013; Glenday et al. 2016).11 Decentralized rural development offers some opportunities to improve input markets for independent smallholders—particularly through the Village Law of 2014 described below—but raising yields still does not guarantee a reduction in extensive land clearing, even with a moratorium on new land concessions in place.

Table 1.

Palm oil yields

| Crude palm oil yield (tons/ha/year) | |

|---|---|

| Global maximum theoretical yielda | 18 |

| Existing high-yielding varietiesb | 9–10 |

| Well-managed plantation (economic maximum yield)c | 5.5–6 |

| World average | 4 |

| Indonesian averaged | 3.7 |

| Indonesian independent smallholdere | 1.5–3 |

The Village Law of 2014

The Village Law of 2014 legislates a direct allocation of state funds to the country’s approximately 75 000 rural villages (desa), and thus represents a further step in Indonesia’s administrative decentralization process. Block grant transfers comprise the majority of an average village’s total budget, which in early 2018 was estimated at IDR 1.5 thousand million ($112 000). Under the Village Law, each village receives approximately $60 000 per year from the central government (known as Dana Desa) in addition to the district transfers it receives (Alokasi Dana Desa) (see Appendix S2 for further details).

In order to receive Dana Desa funding, each village must submit a Rural Development Plan to the district head, which, at least in principle, is drafted in consultation with local residents. The benefit of implementing development plans at the village scale is that there is more direct accountability than at regional or central scales, thus elevating the impact of political decentralization shown in Fig. 1. Nonetheless, corruption, rent-seeking behavior, and administrative capacity constraints can still limit the implementation of local, “pro-poor” development initiatives. Our field interviews suggest that the village planning process is controlled by local elites in many villages.

Although the Village Law is not specific to oil palm, the crop’s prominence ensures that the new law will play a central role in village-led development. Oil palm is already cultivated in over 20 000 of the approximately 30 000 rural villages of Sumatra and Kalimantan (BPS 2014; Kementerian Dalam Negeri 2017). The law may thus prove a powerful tool in improving smallholder productivity and welfare and has the potential to spur local economic growth. Dana Desa funds can be used, for example, to improve smallholder access to inputs and technical support, both through government assistance programs or more market-based approaches. Village governments can also partner with local businesses or create village-owned enterprises (Article 87).12

Despite the benefits of village-based incentives, it remains to be seen whether or not these economic opportunities will lead to worsened environmental outcomes. As in the earlier case of decentralization at the district scale, the 2014 Village Law is devoid of environmental standards and is plagued by ambiguous responsibilities and resource claims at different levels of government. While the law gives considerable new powers to village governments, it does not explicitly remove authority from line ministries, which complicates responsibilities concerning the provision of agricultural inputs and public services (Lewis 2015). Overlapping governance of land and natural resources also encourages a “race to the bottom” in terms of deforestation and land clearing by fire, and generates conflicts between villages and higher levels of government over land rights. Many land issues arise because different government agencies use conflicting maps and spatial plans.13 Village heads have historically allocated land to local residents without taking preexisting permits into consideration, and it is likely that this practice will continue under the Village Law (e.g., McCarthy 2010; Colchester and Chao 2013).

One important warning seems warranted as the Village Law unfolds. Unconditional block grants from the central budget to village budgets carry the risk of imposing large social costs in terms of environmental damage and inequitable income distribution. Recent studies indicate that oil palm expansion in Indonesia has benefitted all income classes in the regions where the crop is grown; marginal gains have often been highest for the lowest income quintile, but absolute gains have tended to favor larger, wealthier farmers and village elites (Euler et al. 2017). There are few, if any, avenues under the law to prevent a village from choosing a development trajectory that disproportionately benefits the elite or that severely damages the environment. Unless the Village Law is re-drafted to enforce existing environmental laws explicitly, local leaders will likely exploit the ambiguity in the overlapping legal structure for their own benefit. In the absence of conditionality, villages are essentially given the responsibility for local economic development without having the instruments to ensure that the development process is sustainable.

Conclusions and a path forward

This article provides an institutional lens for understanding how Indonesia has managed the multiple goals of economic growth, poverty alleviation, environmental protection, and improved governance, particularly in resource-rich regions where oil palm is grown. Decentralization is a dynamic process in Indonesia, and the Village Law of 2014 represents the central government’s ongoing commitment to local accountability, regionally based resource management, and the devolution of development priorities to the village scale.

Although decentralization of political, administrative, and resource management responsibilities has been pursued in Indonesia for almost two decades, there remain serious bureaucratic impasses. The social impacts of decentralization on equity and the environment also remain unresolved. New revenue-sharing agreements and the splitting of districts, both stemming from Indonesia’s decentralization laws, have helped facilitate the rise in independent smallholders and have reduced rural poverty. Yet independent smallholders have few options but to clear land by fire in order to earn a viable living, exacerbating the trade-off between economic development and environmental protection.

Based on evidence presented in this paper, three conclusions related to Indonesia’s decentralization process seem warranted. First, problems arising from oil palm expansion and forest clearing in the “outer” (non-Java) islands continue to be plagued by overlapping claims on land that have become more complicated and obscure through the process of decentralization. Our field interviews reveal that it is not uncommon to find the central government, the provincial or district government, and the local government (and corporate concession holders) simultaneously asserting legitimate claims to a single area. Limited progress has been made in resolving these overlaps or protecting forests, even in conservation areas. Until settled, everyone and no one has responsibility for sustainable development in oil palm regions, regardless of whether large corporate plantations, external investors, or independent smallholders own and clear the land.

Second, the changing structure of governance and revenue-sharing responsibilities under decentralization, while beneficial for averting secession movements and alleviating rural poverty in Indonesia, remain inefficient. “Siloed” central ministries continue to issue decrees and regulations, but often without informed views of political and economic dynamics at the district or village level. District leaders (bupatis) and village headpersons have much of the responsibility for development, but generally have inadequate authority, staff, and finance to implement a sustainable development agenda. When problems arise, varying levels of government have tended to blame other levels and skirt direct responsibility. Our field interviews suggest that widespread use of external facilitators would help local leaders, in particular, to design sustainable development strategies and allocate village funds more efficiently.

Finally, there remains tension in policy tactics in Indonesia between the use of regulations and economic incentives (aka, sticks vs. carrots) in achieving sustainable development objectives around oil palm. The central government has tended to favor directives that limit expansion of palm oil concessions, create bans on burning, and augment the authority of local police and military commanders (vs. village residents) in fire prevention and fire fighting. The use of economic incentives—especially for curtailing the use of fire among the rapidly growing number of independent smallholder producers—remains largely untested. India’s recent program of ecological transfers, in which residents are paid to leave forests standing, represents an important example of such an activity (Busch and Mukherjee 2017).

Indonesia’s decentralization bears ample similarities with other countries’ reforms, and the story told here particularly resonates in resource-intensive economies facing comparable environment–development tradeoffs. While there are certainly lessons to be learned for other countries from Indonesia’s experience, and vice versa, any single case study will always have limited external validity beyond the case in question.

The Indonesian government is now choosing its own path that may prove promising in balancing its economic and environmental objectives. First, it is supporting new initiatives that involve large private-sector oil palm companies working with smallholders in clusters to reduce fires and increase smallholder productivity. Second, it is starting to map out a new Grand Design for fire prevention through a system of positive financial incentives.14 If there can be additional agreement across ministries on the focus of this program, and greater clarification on the responsibilities of each layer of government in implementing the program, Indonesia may have more success in achieving its sustainable development goals. In all of these efforts, however, smallholder producers operating within a decentralized form of governance provide both the greatest challenges and the largest opportunities for enhancing rural development while minimizing environmental degradation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sudarno Sumarto, Paul Heytens, James Leape, John Hartmann, Donald Emmerson and two anonymous reviewers for helpful feedback on the manuscript, and Gracia Hadiwidjaja for her comprehensive assistance in the field.

Biographies

Rosamond L. Naylor

is the William Wrigley Professor of Earth System Science, and Senior Fellow and Founding Director of the Center on Food Security and the Environment at the Stanford University.

Matthew M. Higgins

is a Social Science Research Professional and Project Manager for the Center on Food Security and the Environment’s Indonesian Oil Palm Project at the Stanford University.

Ryan B. Edwards

is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Dartmouth College in the Department of Economics.

Walter P. Falcon

is the Farnsworth Professor of International Agricultural Policy (Emeritus) and Senior Fellow at the Stanford University.

Footnotes

Our focus in this article is on smallholders, despite the important role still played by plantations in producing and milling palm oil. The plantation sector has been covered extensively in the literature (see for example, Cramb and McCarthy 2016; Gaveau et al. 2016a; Seymour and Busch 2016). Many of these documents deal with the dynamics of certifying sustainable-production practices, which, because of cost and complexity, are of limited relevance to independent smallholders. The plantation story is related, but because of length restrictions we have largely excluded it in this article.

By comparison, the value of US soy exports was nearly identical at USD 21.5 billion for the 2017 calendar year (USCB n.d.).

B30 refers to a 30% biodiesel content requirement in diesel fuel mixes. CPO exports are taxed according to a variable levy, and the tax revenues go into a CPO fund that is used for investments in Indonesia’s biodiesel industry and smallholder producers (Byerlee et al. 2017).

For example, Ribot et al. (2006) discuss impediments to decentralization of resource management in six countries: Senegal, Uganda, Nepal, Indonesia, Bolivia, and Nicaragua.

The Indonesian government is split into five levels of administration: central government, provinces, districts (kabupaten), subdistricts (kecamatan), and villages (desa). In 2017, there were 34 provinces, 416 kabupaten, 7492 kecamatan, and 74 851 desa (Kementerian Dalam Negeri 2017). Kota (98 in 2017) and kelurahan (8500 in 2015) refer to cities and urban villages (wards), respectively, and will not be discussed in this paper. The term “regional” is used as a general term referring to subnational governments, usually districts. The terms “village government” and “local government” are used interchangeably.

A maximum of 90% of natural forests within an oil palm concession can be converted legally (Lawson et al. 2014).

For information on the regulations for splitting districts, see Law 22/1999 on Regional Governance or Law 32/2004 on Regional Autonomy.

Recent examples of district police complicit in illegal oil palm development are well documented (EIA 2014). In 2014 then-Governor of Riau Province Annas Maamun was arrested for accepting roughly USD 150 000 in bribes from a major oil palm company in exchange for issuing 2432 ha of land-conversion permits for new oil palm development. The former governor was convicted in June 2015 and sentenced to 6 years in prison.

Legally, a smallholder can manage up to 25 ha. If a farmer acquires greater than 25 ha, they are supposed to register as a small business, although this rarely occurs. Some “smallholders” manage several hundred hectares of land in various locations (Jelsma et al. 2017).

After harvest, FFBs must be milled within 48 h to meet international quality standards. As a result, each mill creates a “supply shed” defined by its capacity utilization and its distance/time from oil palm areas (Byerlee et al. 2017).

In addition, research on comparable systems in Malaysia (Martin et al. 2015), along with evidence from our field interviews in Indonesia, indicate that independent smallholders receive up to 25% lower prices by weight for FFB than plasma smallholders selling to the same mill, mainly as a result of inferior fruit quality and their reliance on intermediaries to transport and sell FFB to the mills.

A wide variety of village-owned enterprises have already been launched under the Village Law, many of which target problems facing smallholder farmers. Our field survey revealed, for example, that the village of Batu Rijal, Dharmasraya, West Sumatra launched a nursery for high-quality oil palm seedlings, which are sold to smallholder farmers at a reduced price. Other villages, such as Sungai Besar and Sungai Pelang in the District of Ketapang, West Kalimantan operate crop aggregation companies that enable villagers to bargain collectively for higher prices. Some villages (e.g., Muara Siran in Kutai Kartanegara District, East Kalimantan and Samurangau in Paser District, East Kalimantan) also use Dana Desa funds to provide microcredit services to villagers.

The “One Map” initiative seeks to merge existing regional, local, and ministerial maps in order to create a single reference map for the entire country although “One Map” was first proposed in 2010, little progress has been made as of November 2018 because many regional governments, corporations, and ministries have been reluctant to provide concession data out of fear that these data will reveal instances of illegality or corruption.

For reference on Indonesia’s Grand Design, see https://www.cifor.org/library/6669/grand-design-pencegahan-kebakaran-hutan-kebun-dan-lahan-2017-2019/.

Contributor Information

Rosamond L. Naylor, Email: roz@stanford.edu

Matthew M. Higgins, Email: higgins2@stanford.edu

Ryan B. Edwards, Email: ryan.b.edwards@dartmouth.edu

Walter P. Falcon, Email: wpfalcon@stanford.edu

References

- Agrawal A, Ribot J. Accountability and decentralization: A framework for South Asian and West African cases. Journal of Developing Areas. 1999;33:473–502. [Google Scholar]

- Alisjahbana AS, Busch JM. Forestry, forest fires, and climate change in Indonesia. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies. 2017;53:111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Alwarritzi W, Nanseki T, Chomei Y. Analysis of the factors influencing technical efficiency among oil palm smallholder farmers in Indonesia. Procedia Environmental Sciences. 2015;28:630–638. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ZR, Kusters K, McCarthy J, Obidzinski K. Green growth rhetoric versus reality: Insights from Indonesia. Global Environmental Change. 2016;38:30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Antara News. 2014. Riau’s two million hectares of oil palm plantation illegal: Minister. Published 6 August 2014. http://www.antaranews.com/en/news/95203/riaus-two-million-hectares-of-oil-palm-plantation-illegal-minister. Accessed 15 Aug 2016.

- Arnold LL. Deforestation in decentralized Indonesia: What’s law got to do with it? Law, Environment, and Development Journal. 2008;4:75. [Google Scholar]

- Aspinall, E., and G. Fealy. 2003. Local power and politics in Indonesia: Decentralization and democratization. Indonesia update series. Singapore: ISEAS.

- Aspinall E. Democratization and ethnic politics in Indonesia: Nine theses. Journal of East Asian Studies. 2011;11:289–318. [Google Scholar]

- Badan Pusat Statistik, BPS (Central Bureau of Statistics). 2013. Sensus pertanian 2013 (Agricultural Census). Angka nasional hasil survei ST2013—subsektor rumah tangga usaha perkebunan (National figures of estate crop cultivation households, results of ST2013 subsector survey). BPS Catalog 510616 (in Indonesian, dataset).

- Badan Pusat Statistik, BPS (Central Bureau of Statistics). 2014. Pendataan Potensi Desa (PODES) 2014 (Data collection for village potential). ID Number 00-PODES-2014-M1. http://microdata.bps.go.id/mikrodata/index.php/catalog/599. Accessed 20 April 2017 (in Indonesian, dataset).

- Bardhan P. Decentralization of governance and development. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2002;16:185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Bardhan P. State and development: The need for a reappraisal of the current literature. Journal of Economic Literature. 2016;54:862–892. [Google Scholar]

- Barr C, Resosudarmo IAP, Dermawan A, McCarthy J, Moeliono M, Setiono B. Decentralization of forest administration in Indonesia: Implications for forest sustainability, economic development, and community livelihoods. Bogor: Center for International Forestry Research; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzi, S., and M. Gudgeon. 2017. The political boundaries of ethnic divisions. Boston University Working Paper.

- Budidarsono, S., S. Dewi, M. Sofiyuddin, and A. Rahmanulloh. 2012. Socioeconomic impact assessment of palm oil production. Palm oil series. Technical Brief No. 27. Bogor: World Agroforestry Centre, ICRAF SEA Regional Office.

- Burgess R, Hansen M, Olken BA, Potapov P, Sieber S. The political economy of deforestation in the tropics. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2012;127:1707–1754. [Google Scholar]

- Busch J, Mukherjee A. Encouraging state governments to protect and restore forests using ecological fiscal transfers: India’s tax revenue distribution reform. Conservation Letters. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Byerlee D, Falcon WP, Naylor RL. The tropical oil crop revolution: Food, feed, fuel, and forests. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cahyadi ER, Waibel H. Contract farming and vulnerability to poverty among smallholders in Indonesia. Journal of Development Studies. 2016;52:681–695. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson KM, Curran LM, Asner GP, Pittman AM, Trigg SN, Adeney JM. Carbon emissions from forest conversion by Kalimantan oil palm plantations. Nature Climate Change. 2013;3:283–287. [Google Scholar]

- CIFOR. 2010. Position case of Tengku Azmun Jafaar. Integrated law enforcement approach. Bogor: Center for International Forestry Research. http://www.cifor.org/ilea/_ref/indicators/cases/decision/Tengku_Azmun_Jaafar.htm.

- Colchester, M., and S. Chao, eds. 2013. Conflict or consent? The oil palm sector at a crossroads. FPP, Sawit Watch, and Tuk Indonesia. http://www.forestpeoples.org/sites/fpp/files/publication/2013/11/conflict-or-consentenglishlowres.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2017.

- Colchester, M., N. Jiwan P. Anderson, A. Darussamin, and A. Kiky. 2011. Securing high conservation values in Central Kalimantan: Report of the field investigation in Central Kalimantan of the RSPO Ad Hoc Working Group on High Conservation Values in Indonesia. In Roundtable on sustainable palm oil. http://www.forestpeoples.org/sites/fpp/files/publication/2012/08/final-report-field-investigation-rspo-ad-hoc-wg-hcv-indo-july-20113.pdf.

- Corley RHV, Tinker PB. The oil palm. 5. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cramb R, McCarthy J, editors. The oil palm complex: Smallholders, agribusiness and the state in Indonesia and Malaysia. Singapore: NUS Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate General of Estate Crops . Tree crop estate statistics of Indonesia, palm oil, 2015–2017. Jakarta: Department of Agriculture; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, R.B. 2017. Tropical oil crops and rural poverty. Stanford University Center on Food Security and the Environment Working Paper. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3040400&download=yes. Accessed 2 July 2018.

- Edwards SA, Heiduk F. Hazy days: Forest fires and the politics of environmental security in Indonesia. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs. 2015;34:65–94. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Investigation Agency, EIA. 2014. Permitting crime: How palm oil expansion drives illegal logging in Indonesia. Environmental Investigation Agency UK. https://eia-international.org/wp-content/uploads/Permitting-Crime.pdf.

- Euler M, Krishna V, Schwarze S, Siregar H, Qaim M. Oil palm adoption, household welfare, and nutrition among smallholder farmers in Indonesia. World Development. 2017;93:219–235. [Google Scholar]

- Eyes on the Forest, EoF. 2016. No one is safe: Illegal Indonesian palm oil spreads through global supply chains despite global sustainability commitments and certification. Eyes on the Forest Investigative Report. http://www.eyesontheforest.or.id/attach/EoF%20(06Apr16)%20No%20One%20is%20Safe%20English%20FINAL.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2017.

- Feintrenie L, Chong WK, Levang P. Why do farmers prefer oil palm? Lessons learnt from Bungo District, Indonesia. Small-Scale Forestry. 2010;9:379–396. [Google Scholar]

- Firman T. Decentralization reform and local government proliferation in Indonesia: Towards a fragmentation of regional development. Review of Urban and Regional Studies. 2010;21:143–157. [Google Scholar]

- Fitrani F, Hofman B, Kaiser K. Unity in diversity? The creation of new local governments in a decentralizing Indonesia. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies. 2005;4:57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Gatto M, Wollni M, Asnawi R, Qaim M. Oil palm boom, contract farming, and rural economic development: Village-level evidence from Indonesia. World Development. 2017;95:127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Gaveau DLA, Sheil D, Husnayaen, Salim MA, Arjasakusuma S, Ancrenaz M, Pacheco P, Meijaard E. Rapid conversion and avoided deforestation: Examining four decades of industrial plantation expansion in Borneo. Scientific Reports. 2016 doi: 10.1038/srep32017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaveau DLA, Pirard R, Salim MA, Tonoto P, Yaen H, Parks SA, Carmenta R. Overlapping land claims limit the use of satellites to monitor no-deforestation commitments and no-burning compliance. Conservation Letters. 2016;10:257–274. [Google Scholar]

- Glenday, S., G. Paoli, G. Limberg, and J. Schweithelm. 2016. Indonesian oil palm smallholder farmers: Access to credit and investment finance. Bogor: Daemeter. http://daemeter.org/new/uploads/20161105173525.Daemeter_SHF_2016_WP2_ENG_compressed.pdf. Accessed 26 June 2017.

- Grossman G, Lewis J. Administrative unit proliferation. American Political Science Review. 2014;108:196–217. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, H. 2014. Regional dynamics in a decentralized Indonesia. Indonesia update series. Singapore: ISEAS.

- Hunt C. The costs of reducing deforestation in Indonesia. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies. 2010;46:187–92. [Google Scholar]

- International Crisis Group, ICG. 2012. Indonesia: The deadly cost of poor policing. Asia Report No. 218. https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-east-asia/indonesia/indonesia-deadly-cost-poor-policing. Accessed 26 June 2017.

- Jelsma I, Schoneveld GC, Zoomers A, van Westen ACM. Unpacking Indonesia’s independent oil palm smallholders: An actor-disaggregated approach to identify environmental and social performance challenges. Land Use Policy. 2017;69:281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, K. 2014. Arrest of Indonesia’s first woman governor a blow for coalition. Reuters. Published 9 Feb 2014. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-indonesia-politics-banten-idUSBREA180XC20140209. Accessed 18 July 2016.

- Kementerian Dalam Negeri (Ministry of Home Affairs). 2017. Kode dan data wilayah administrasi Pemerintahan. Permendagri No. 137-2017. Administrative area codes and data. http://www.kemendagri.go.id/media/documents/2015/02/25/l/a/lampiran_i.pdf. Accessed 30 June 2018 (in Indonesian).

- Kementerian Pertanian (Ministry of Agriculture). n.d. Basis data ekspor-impor komoditi pertanian (Agricultural commodity export–import database). http://database.pertanian.go.id/eksim/index1.asp. Accessed 29 March 2017 (in Indonesian, dataset).

- Kvale S. Interviews: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, S., A. Blundell, B. Cabarle, N. Basik, M. Jenkins, and K. Canby. 2014. Consumer goods and deforestation: An analysis of the extent and nature of illegality in forest conversion for agriculture and timber plantations. Forest Trends Report Series. http://www.forest-trends.org/documents/files/doc_4718.pdf. Accessed 26 June 2017.

- Lewis BD. Decentralising to villages in Indonesia: Money (and other) mistakes. Public Administration and Development. 2015;35:347–359. [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb M, Mobarak AM. Decentralization and pollution spillovers: Evidence from the re-drawings of county borders in Brazil. Review of Economic Studies. 2017;84:464–502. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, J., and R. Toth. 2017. Where there is fire there is haze: The economic and political causes of Indonesia’s forest fires. University of Sydney Working Paper.

- Malaysia Palm Oil Board, MPOB. 2011. Oil palm in Malaysia. http://www.palmoilworld.org/about_malaysian-industry.html. Accessed 28 Sep 2016.

- Manor, J. 1999. The political economy of democratic decentralization. Directions in Development No. 19080. The World Bank.

- Marlier ME, DeFries RS, Kim PS, Koplitz SN, Jacob DJ, Mickley LJ, Myers SS. Fire emissions and regional air quality impacts from fires in oil palm, timber, and logging concessions in Indonesia. Environmental Research Letters. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Martin S, Rieple A, Chang J, Boniface B, Ahmed A. Small farmers and sustainability: Institutional barriers to investment and innovation in the Malaysian palm oil industry in Sabah. Journal of Rural Studies. 2015;40:46–58. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JF. Changing to gray: Decentralization and the emergence of volatile socio-legal configurations in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. World Development. 2004;32:1199–1223. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JF. Processes of inclusion and adverse incorporation: Oil palm and agrarian change in Sumatra, Indonesia. Journal of Peasant Studies. 2010;37:821–850. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2010.512460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JF, Zen Z. Regulating the oil palm boom: Assessing the effectiveness of environmental governance approaches to agro-industrial pollution in Indonesia. Law and Policy. 2010;32:153–179. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JF, Gillespie P, Zen Z. Swimming upstream: Local Indonesian production networks in “globalized” palm oil production. World Development. 2012;40:555–569. [Google Scholar]

- Nasution, A. 2016. Government decentralization program in Indonesia. Asian Development Bank Institute. Working Paper No. 601.

- Naylor, R.L., and W.P. Falcon. 2008. Our daily bread: A current review of the world food crisis. Boston Review. http://bostonreview.net/rosamond-naylor-and-walter-falcon-our-daily-bread-global-food-crisis.

- Naylor RL, Falcon WP. Food security in an era of economic volatility. Population Development Review. 2010;36:693–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor RL, Higgins MM. The political economy of biodiesel in an era of low oil prices. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2017;77:695–705. [Google Scholar]

- Oates WE. An essay on fiscal federalism. Journal of Economic Literature. 1999;37:1120–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Obidzinski K, Adriani R, Komarudin H, Andrianto A. Environmental and social impacts of oil palm plantations and their implications for biofuels production in Indonesia. Ecology and Society. 2012;17:25. [Google Scholar]

- Pal S, Wahhaj Z. Fiscal decentralization, local institutions and public good provision: Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Comparative Economics. 2017;45:383–409. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer C, Engel S. For better or worse? Local impacts of the decentralization of Indonesia’s forest sector. World Development. 2007;35:2131–2149. [Google Scholar]

- Pepinski TB, Wihardja MM. Decentralization and economic performance in Indonesia. Journal of East Asian Studies. 2011;11:337–371. [Google Scholar]

- Pierskalla J. Splitting the difference? The politics of district creation in Indonesia. Comparative Politics. 2016;48:249–268. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, L. 2015. Who is ‘land grabbing’? Who is deforesting? Will certification help prevent bad practice? In Land grabbing, conflict and agrarian-environmental transformations: Perspectives from East and Southeast Asia Conference, 5–6 June 2015. Conference Paper No. 40. Chiang Mai: Chiang Mai University. http://www.iss.nl/fileadmin/ASSETS/iss/Research_and_projects/Research_networks/BICAS/CMCP_40-_Potter.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2017.

- Rada, N., and A. Regmi. 2010. Trade and food security implications from the Indonesian agricultural experience. USDA International Agriculture and Trade Outlook No. WRS-10-01.

- Resosudarmo IAP. Closer to people and trees: Will decentralization work for the people and the forests of Indonesia? European Journal of Development Research. 2004;16:110–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ribot J, Agrawal A, Larson A. Recentralizing while decentralizing: How national governments reappropriate forest resources. World Development. 2006;34:1864–1886. [Google Scholar]

- Rist L, Feintrenie L, Levang P. The livelihood impacts of oil palm: Smallholders in Indonesia. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2010;19:1009–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Samosir, Y.M.S., B. Drajat, and P. Gillespie. 2013. Fertilizer and oil palm in Indonesia: An overview of the industry and challenges for small-scale oil palm farmer applications. Bogor: Daemeter. http://daemeter.org/new/uploads/20130905132708.Final_Fertiliser_and_independent_smallholders_in_Indonesia____Background_and_Challenges.pdf. Accessed 4 April 2017.

- Sayer J, Ghazoul J, Nelson P, Boedhihartono AK. Oil palm expansion transforms tropical landscapes and livelihoods. Global Food Security. 2012;1:114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Serikat Petani Kelapa Sawit, SPKS (Oil Palm Smallholders Union). n.d. Strengthening independent smallholders in Indonesia. http://www.rspo.org/file/strengthening_independent_smallholders_in_indonesia_PDF_by_SPKS.pdf. Accessed 25 Sep 2017.

- Seymour F, Busch J. Why forests? Why now? The science, economics, and politics of tropical forests and climate change. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sjarina, A., J.D. Widoyoko, and L. Abid. 2013. Exhausting the earth, snatching the chair: Politic-business patron practice in land conversion—A case study and policy recommendation. Indonesia Corruption Watch Policy Paper. http://www.antikorupsi.org/sites/antikorupsi.org/files/doc/Kajian/policybriefrisetpatronasebisnispolitikdandeforestasi.pdf. Accessed 26 June 2017.

- Susila WR. Contribution of oil palm industry to economic growth and poverty alleviation in Indonesia. Jurnal Penelitian dan Pengembangan Pertanian. 2004;23:107–113. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau, USCB. n.d. US trade home—Exports. https://usatrade.census.gov/data/Perspective60/View/dispview.aspx. Accessed 30 June 2018 (dataset).

- Verbrugge B. Decentralization, institutional authority, and mineral resource conflict in Mindanao, Philippines. World Development. 2015;67:449–460. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2000. Chapter 5: Decentralization: rethinking government. In World development report: Entering the 21st century. Washington, DC

- World Bank. 2003. Decentralizing Indonesia: A regional public expenditure review overview report. Public expenditure review (PER). Washington, DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/14632. Accessed 26 June 2017.

- World Bank. 2016. The cost of fire: An economic analysis of the 2015 fire crisis. Indonesia Sustainable Landscapes Knowledge Note 1. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/643781465442350600/Indonesia-forest-fire-notes.pdf.

- WWF-Indonesia. 2013. Palming off a national park: Tracking illegal oil palm fruit in Riau, Sumatra. https://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/palming-off-a-national-park-tracking-illegal-oil-palm-fruit-in-riau-sumatra. Accessed 26 June 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.