Abstract

Cardio-metabolic diseases (CMD; cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease) represent a global public health problem. Worldwide, nearly half a billion people are currently diagnosed with diabetes, and cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death. Most of these diseases can be assuaged/prevented through behavior change. However, the best way to implement preventive interventions is unclear. We aim to fill this knowledge gap by creating an evidence-based and adaptable “toolbox” for the design and implementation of selective prevention initiatives (SPI) targeting CMD. We built our toolbox based on evidence from a pan-European research project on primary-care SPIs targeting CMD. The evidence includes (1) two systematic reviews and two surveys of patient and general practitioner barriers and facilitators of engaging with SPIs, (2) a consensus meeting with leading experts to establish optimal SPI design, and (3) a feasibility study of a generic, evidence-based primary-care SPI protocol in five European countries. Our results related primarily to the five different national health-care contexts from which we derived our data. On this basis, we generated 12 general recommendations for how best to design and implement CMD-SPIs in primary care. We supplement our recommendations with practical, evidence-based suggestions for how each recommendation might best be heeded. The toolbox is generic and adaptable to various national and systemic settings by clinicians and policy makers alike. However, our product needs to be kept up-to-date to be effective and we implore future research to add relevant tools as they are developed.

Keywords: Preventive health care, Behavior change, Primary care, Prevention, Cardiovascular disease, Lifestyle-related disease, Self-efficacy

Summary box

|

What is already known about this topic? Ample evidence suggests that cardio-metabolic diseases (CMD) can be prevented through early detection of the high-risk population and subsequent lifestyle-change intervention. Many preventive interventions have been implemented in different countries, with varying success. Numerous barriers and facilitators of health care professional and patient receptiveness to such interventions have been identified, spanning systemic, operational, financial, and motivational issues. What does this study add? We synthesize the current evidence base as it relates to barriers and facilitators of patient and health professional participation in preventive CMD interventions implemented in primary care. On this basis, we then develop a generic “toolbox” for circumventing identified obstacles and harnessing facilitators in the design and implementation of such interventions. Our results are based on data from five European countries. The resulting toolbox is similarly designed for use in different communities, countries, and cultures. Policy implications Based on the evidence, we identify three central areas which should be considered by policy makers and clinicians alike when designing and implementing CMD preventive interventions. These relate to appropriate funding and stakeholders, identification of the high-risk population and risk assessment methodology, and facilitating intervention participation in health professional and patient populations. We then offer specific and applicable advice (tools) on how exactly to address these issues. |

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. Introduction

Globally, there is a clear and present need for early detection and preventive intervention against cardio-metabolic disease (CMD; cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease) (Kesteloot et al., 2005; Björck et al., 2009). Worldwide, 422 million people are currently diagnosed with diabetes mellitus (World Health Organization, 2017a). Further, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is currently the most common cause of mortality, accounting for 31% of all deaths (17.9 million deaths) worldwide (Yusuf et al., 2015; World Health Organization, 2017b). These numbers are staggering – especially when considering the fact that CMDs are preventable 80% of the time (World Health Organization, 2017b). That is, while more fixed factors, such as low socio-economic status (SES) or a family history of poor health, contribute to the likelihood of CMD, other significant precursors relate to changeable health behaviors. These include most importantly smoking, alcohol consumption, poor diet, and/or leading a sedentary lifestyle. Considering how common these risk factors are, rates of CMD will in all likelihood only escalate (Rosamond et al., 2008; Wild et al., 2004; Yusuf et al., 2001). Potential solutions to this predicament are few and far in between. Systematic and periodic general health checks in general practice have shown mixed results at best. And while more sophisticated interventions using stepwise approaches to risk assessment have gained considerable attention in the past five years, the evidence base on design and implementation strategies of preventive CMD interventions is still lacking. In the present paper, we review evidence from a recent EU-funded, pan-European research project (Determinants of Successful Implementation of Selective Prevention of Cardio-metabolic Diseases Across Europe (SPIM-EU)) to create a “toolbox” for the design and implementation of preventive CMD interventions. The toolbox contains generic, empirical, and practical recommendations (“tools”) that are designed to apply across national and cultural contexts. As a core component, however, we also offer evidence-based suggestions for how to tailor our tools to fit specific, local community settings.

1.1. Selective prevention initiatives

There are a number of different avenues for preventive action against CMD. These are typically classified in terms of the target population, and generally refer to three basic approaches: Universal, indicated, or selective prevention (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Types of preventive action targeting CMD.

| Universal prevention | Focuses on the general population. Thus, the entire population is considered to be at risk, with no regard to individual risk factors. As such, the whole population has potential to benefit from intervention. |

| Indicated prevention | Addresses already-diagnosed individuals, and/or individuals who display early signs of CMD. |

| Selective prevention | Targets sub-groups of the general population that are determined to be at increased risk of developing CMD. These populations are identified through individual risk assessment and interventions are tailored to their specific circumstances. |

Past research suggests that universal prevention strategies (e.g. legislation) alone are insufficient to control increasing CMD rates (Jørgensen et al., 2014). Indeed, selective prevention is often considered crucial in preventive strategies. This is because early identification of the high-risk population theoretically allows time to facilitate lifestyle changes. This argument is supported by studies from the UK, where a 54% reduction in CMD-mortality rates between 1981 and 2000 was attributed to behavioral changes and preventive medication in high-risk, pre-symptom populations (Unal et al., 2005). Thus, complementing universal preventive efforts with selective prevention initiatives (SPIs) may be an effective way to intervene against CMD. However, implementing such programs is often complicated by various issues. These relate principally to the reliable identification of the high-risk population, health professional and patient responsiveness to the program, and the receptiveness of the systemic setting for which the SPI is designed.

A number of methods to identify the high-risk population has been trialed in a range of settings. A particularly innovative approach, designed and tested in the Netherlands, has generated interesting results. This program – the Prevention Consultation Cardiometabolic Risk module – includes a stepwise process (Dekker et al., 2011):

-

1.

A voluntary health-risk screening of individuals deemed to be at increased risk by virtue of their age alone (45–70-year-old).

-

2.

A GP health check of the high-risk population identified in step A. In this step, the true high-risk population is identified.

-

3.

Individually tailored preventive action is then taken to reduce the risk level in the identified population.

While pilot data indicates somewhat low patient responsiveness to the program, the implementation of this SPI in the primary-care sector suggests potential for effective identification and treatment of the high-risk population (Nielen et al., 2011; Van der Meer et al., 2013). While auspicious in a Dutch setting, the feasibility of this program in other countries has yet to be tested (Brotons et al., 2005; Kringos et al., 2013). Indeed, when it comes to designing and implementing SPIs targeting CMD, there are numerous moving parts that need to be considered, including organizational implementation issues as well as GP and patient attitudes to, and uptake of a given SPI. However, these issues likely vary in significance and nature depending on cultural and systemic setting.

1.2. The SPIMEU project

The SPIMEU project focuses specifically on early detection and intervention against the development of CMD. Taking into account the considerable variation in EU countries' health care systems (specifically in terms of quality, extensiveness, and organization), we focused on how best to mobilize and implement effective selective prevention initiatives in the EU at large. The main objectives of the SPIMEU project therefore relate to establishing the feasibility of implementing CMD-SPIs in five different national health-care systems in the EU (see Table 2). Based on our empirical results from this project as well as on the broader literature, we aim to create a “toolbox” that contains evidence-based practical recommendations and “do's and don'ts” for future SPI design and implementation.

Table 2.

Health care system characteristics in the SPIMEU partner countries.

| Country | Universal health care | Type of health-care systema | Strength of primary-care sectorb | GP gatekeeping |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweden | Yes | NHS | Medium | Partial |

| Denmark | Yes | NHS | High | No |

| The Netherlands | Yes | SHI | High | Full |

| Czech Republic | Yes | Transitional | Medium | No |

| Greece | Yes | NHS | Low | No |

Transitional: Former Semashko (Soviet) system, NHS: National Health Service, SHI: Social Health Insurance based system.

2. Method

The SPIMEU project investigated the potential of evidence-based SPIs in the Netherlands, Greece, the Czech Republic, Sweden, and Denmark. In order to do this, we designed five work packages (WPs; see Table 3) focusing on various aspects of selective prevention in terms of intervention design and implementation. In WP A (Hollander and de Waard, In press), we examined the practical and structural organization of past and current SPIs in Europe. We then investigated the barriers and facilitators of patient (de Waard et al., 2018a) and GP (de Waard et al., 2018b; Wändell et al., 2018) attitudes to selective prevention of CMD (WP B & C, respectively). In WP D and E, we developed (Kral et al., In press) and feasibility tested (Lionis et al., 2018) a generic CMD-SPI in the five partner countries.

Table 3.

Aim, methods, results, and principal findings of the SPIMEU project work packages.

| WP | Aim | Method | Results | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Identification and evaluation of SPIs implemented in the EU (Hollander and de Waard, In press). |

Design: Cross-sectional online survey study. Participants: 94 European experts on CMD-SPIs. |

|

The review determined that the principal precursors for successful implementation of CMD-SPIs are sustainable financing and involvement of policy makers and health professionals. |

| B | Evaluation of common barriers/facilitators of patient and GP uptake and compliance with SPIs in European primary care systems (Wändell et al., 2018). | Design: A systematic review – one focusing on GPs and one on patients. |

|

GPs: Most common barriers were lack of time, lack of reimbursement, lack of counseling skills. Most common facilitators were positivity towards prevention. Patients: Demographic and attitudinal factors predicted CMD-SPI uptake. Barriers and facilitators overlapped, but varied across countries. |

| C | Assessment of GPs' use of SPIs, and GP and patient attitudes towards selective prevention in the five partner countries (de Waard et al., 2018a; de Waard et al., 2018b). |

Design: Two cross-sectional survey studies, one on GPs and one on patients. Participants: 575 GPs & 1354 patients, divided evenly across five SPIMEU countries. |

GP study:

|

GPs: Most GPs considered CMD-SPIs as useful and necessary. However, far from all had implemented any. Biggest barrier was patient invitation. CMD-SPIs need to be tailored to local settings and context. Patients: Uptake of CMD-SPIs in the EU is generally high. The factors that predict non-participation vary across countries. CMD-SPIs should therefore be tailored to local settings and context. |

| D | Development of practical, step-wise implementation method for SPIs (Kral et al., In press). |

Design: RAND/UCLA appropriateness method.a 32 statements on SPI use were discussed & rated. Participants: 12 CMD experts from seven EU countries. |

|

A set of 31 evidence-based recommendations for the most effective and efficient CMD-SPI implementation was developed by the panel of experts. |

| E | Development/implementation of generic patient identification and recruitment method based on SPIMEU results (Lionis et al., 2018). | Design: Feasibility study Participants: 22 GPs from the five SPIMEU countries. |

|

The SPIMEU CMD-SPI may be successfully adapted to various primary-care systems in the EU – especially in countries where CMD prevalence is high and that lack other prevention strategies. |

A validated method to synthesize the evidence and expert opinion on a given topic.

In order to design our toolbox, we reviewed all of the evidence from the SPIMEU project as well as the extant literature, carefully identifying any themes and variations in terms of SPI barriers and facilitators. On this basis, we then developed a series of recommendations designed to inform current and future CMD-SPIs. Where possible, we supplemented these recommendations with evidence-based suggestions – or tools – that may be employed to circumvent noted barriers and/or emphasize facilitators.

3. Results

3.1. Tools for the design and implementation of CMD-SPIs

All SPIMEU methodology, results, and output are freely available on the SPIMEU website (www.spimeu.org). Reviewing and synthesizing this evidence, we identified a series of themes and variations in terms of barriers and facilitators of CMD-SPIs. These related to a broad range of issues, including practical (e.g. SPI funding structure), methodological (e.g. SPI implementation method), and psychological (motivating patient/health professional participation) matters. We have arranged these issues in four central categories (see Table 4).

-

1.Funding and stakeholders

-

1.1To the furthest extent possible, all central stakeholders (e.g. policy makers, health care professionals) should be involved in the design and implementation process of SPIs.

In our systematic review of existing CMD-SPIs in the EU, we identified a total of 19 initiatives currently implemented in 16 EU countries. While the design, target population, and implementation methods varied considerably among these initiatives, a relatively clear common denominator related to the continuous participation of policy makers and primary health-care workers. Specifically, while the design and implementation of SPIs typically represented a shared responsibility among all stakeholders, policy makers (and to some extent public-health organizations) were mostly involved in the developmental phases of the SPI, whereas health-care workers typically spearheaded the execution of the project. Our review did not include an assessment of the effectiveness of the identified SPIs. Nonetheless, the sheer prevalence of implemented interventions within the EU speaks to the fruitful nature of collaboration between central stakeholders. Organizing and encouraging such collaborations may thus be key in the advancement of CMD-SPIs.

In addition, the procurement of adequate subsidies for all stages of the design and implementation process is paramount to the success of an SPI. This becomes abundantly clear when reading through this toolbox, where most – if not all – of the tools require continuous funding to realize effectively.-

1.1.1Identify and organize key stakeholders in CMD prevention

A key policy statement from the main cardiology and cardiovascular medical professional associations in the US and Europe, emphasizes stakeholder inclusiveness in CMD prevention (Arena et al., 2015). The statement identifies key organizations that could (and perhaps should) be approached when designing and implementing preventive initiatives. These include medical organizations, educational systems, health insurance companies, government, media outlets, and the food industry. Drawing on efforts such as these to facilitate productive, interdisciplinary collaborations may prove useful in the design and implementation of comprehensive CMD-SPIs.-

1.2To maximize success and effect of SPIs, funding of the initiatives should be sustainable over time

Of the 19 EU CMD-SPIs identified in our WP A review, 50% were subsidized by health care insurance, 44% by policy makers, 32% by public health organizations, and 13% by patients (Hollander and de Waard, In press). In eight countries, SPI funding sources were unclear. The capital for single-source funding of SPIs typically came from health insurance, municipal health organizations, or the government. Multi-source funded SPIs were financed by municipal authorities, government, patient organizations, and/or health-care insurance. There is currently no evidence to support either funding scheme (single- vs. multi-source) as being better than the other. However, stable funding is obviously imperative to an initiative's success, and should to be secured in full pre-implementation. Tool #1.1.1 above may be useful to this end.

-

1.1

-

2.Risk assessment & identification of the target population

-

2.1In order to facilitate accurate and efficient identification of the high-risk population, the definition of this population should be clear and concise and take into account age and pre-existing conditions.

Selective prevention is, by definition, focused on treating the high-risk segment of the general population. In order to systematically access this population, it must first be defined. Our WP D consensus meeting discussions arrived at two recommendations for the definition of the high-risk population (Kral et al., In press):-

2.1.1Age range: The target population should include (but not necessarily be limited to) people between 40 and 70 years old. Current evidence that shows that this age bracket is most likely to be at increased risk of CMDs, and also most likely to respond positively to preventive efforts.

-

2.1.2Pre-existing conditions: By definition, the high-risk population for CMD-SPIs does not include people who have been diagnosed with a CMD.

-

2.2For optimum accuracy and validity, locally validated risk-assessment tools will likely yield the best results in terms identifying the target population.

At our consensus meeting, there was unanimous agreement that CMD-risk assessment should be conducted by use of locally validated measures (Kral et al., In press). This recommendation was based on the presumably greater efficacy of local measures in terms of accuracy, reliability, and cultural appropriateness. Indeed, when implementing the WP E feasibility study, we used only locally validated risk-assessment instruments to identify the high-risk populations in the respective partner countries. In the event that no locally validated assessment tool is available, adapting one from a similar country may be feasible.

-

2.1

-

3.Health professionals – motivating participation and engagement

-

3.1The initiative should accommodate health professionals' existing workload and time constraints.

-

3.1

Table 4.

Toolbox general recommendations and sections.

| Category | Issue |

|---|---|

| 1. Funding & stakeholders | 1.1 To the furthest extent possible, all central stakeholders (e.g. policy makers, health care professionals) should be involved in the design and implementation process of SPIs. |

| 1.2 To maximize success and effect of SPIs, funding of the initiatives should be sustainable over time. | |

| 2. Risk assessment & target population identification | 2.1 In order to facilitate accurate and efficient identification of the high-risk population, the definition of this population should be clear and concise, and take into account age and pre-existing conditions. |

| 2.2 For optimum accuracy and validity, locally validated risk-assessment tools will likely yield the best results in terms identifying the target population. | |

| 3. Motivating participation and engagement of health professionals | 3.1 The initiative should accommodate health professionals' existing workload and time constraints. |

| 3.2 A clear, evidence-based protocol for the implementation of the initiative should be made available to all participating health professionals. | |

| 3.3 If needed, education in selective prevention and training in the specific initiative protocol should be made available to health professionals and their staff. | |

| 4. Motivating participation and engagement of patients | 4.1 Patient apprehensions related to potential health-check outcomes, should be anticipated and assuaged pre-implementation. |

| 4.2 Patients' feelings of powerlessness to affect their own health should be anticipated and counteracted before and during implementation. | |

| 4.3 Lack of patient knowledge in terms of the causes of and susceptibility to CMD, as well as its potential severity, should also be anticipated and counteracted pre-implementation. | |

| 4.4 Patients' potential time constraints (work/family, etc.) and/or other practical obstacles (geography, financial, etc.) may impact on their likelihood of showing up for a health check and should be accommodated to the furthest extent possible throughout implementation. | |

| 4.5 Method of invitation to participate in the SPI should be evidence-based and optimally consist of an invitation from the patient's GP, supplemented with information on the purpose and nature of a health check. |

Our systematic review (WP B) (Wändell et al., 2018) indicated that one of the most frequently reported barriers to GP participation in SPIs related to increased workload and time constraints. In other words, GPs were often overwhelmed by the added responsibilities of implementing an SPI. Our findings suggest that these barriers may be overcome by reducing responsibilities and reimbursing time and extra work load. This may be achieved in different ways depending on the local health-care setting:

-

3.1.1

Sharing the burden: In Denmark the primary care system includes general practice and municipal health centers. A current Danish prevention project refers patients at increased risk of CMD to either their GP or a health center depending on their level of risk (Larsen et al., In press). Specifically, high-risk patients are offered a health check at their GP, while those at medium risk (i.e. healthy people who engage in health-risk behaviors such as smoking) are referred to a health center for lifestyle intervention. The high-risk population is thus divided into categories based on need, spreading the burden across multiple treatment facilities.

-

3.1.2

Providing support staff: Given sufficient funding, an SPI may incorporate administrative personnel for the identification and recruitment of high-risk patients, thus minimizing the workload for health professionals. For example, in the feasibility study (WP E) (Lionis et al., 2018), the Dutch and Danish research teams were responsible for patient recruitment, risk assessment, and inviting patients to GP health checks. GPs' responsibilities were thus limited to providing researcher access to their patient lists and performing health checks. An expanded version of this protocol could entail support staff (e.g. a physician's assistant) conducting the entire health check.

-

3.1.3

Incentivizing GP participation: One of the most significant facilitators of GP SPI participation pertains to financial incentives. For instance, in the Czech Republic the government reimburses patients for the cost of GP CMD-risk assessments. This represents an important source of income for GPs. Since the inception of this initiative in 1995, Czech GPs are among the most likely in all of Europe to practice active selective prevention of CMD (WP C) (de Waard et al., 2018b; Wändell et al., 2018). Indeed, we found that 69% of Czech GPs practiced selective prevention compared to an average of 40% in the other SPIMEU countries. In other words, the evidence suggests that financial incentives may facilitate GP SPI participation in spite of existing workloads and time constraints.

-

3.2

A clear, evidence-based protocol for the implementation of the initiative should be made available to all participating health professionals.

For SPIs to be effective and sustained in practice over time, practitioners need access to and/or training in a clear, actionable, and tailored protocol. For example, past studies have found that lack of GPs' awareness of existing SPI guidelines represents a central barrier (Voogdt-Pruis et al., 2011; Ferrante et al., 2013; George et al., 2013). Similarly, other research indicates that inconsistent/unclear guidelines not only confused practitioners, but ultimately discouraged them from participating wholeheartedly or at all (George et al., 2013; Diehl et al., 2015). Devising clear and feasible protocols may be achieved by referring to past and current SPIs:

-

3.2.1Relevant steps in SPI protocols: In our review of CMD-SPIs within the EU, several common characteristics of implemented SPIs emerged. Notably, these included six basic steps:

-

1.Identification of the target population (74% of identified SPIs; see point 2 above).

-

2.Survey risk assessment of the target population (70%; see point 3 above).

-

3.Physical examination (85%).

-

4.Laboratory tests (81%).

-

5.Specific interventions for high-risk patients (74%).

-

6.A patient follow-up system (67%)

-

1.

-

3.2.2

SPIMEU selective prevention feasibility protocol: As an example of a tailored protocol for an SPI, we refer to the one developed for the feasibility study (WP E) (Lionis et al., 2018). This was a two-step protocol, including a core method and a tailored method. The core method was uniform across countries and specified the target population, the target population identification method, and comparable risk-assessment methods. By contrast, the tailored method allowed each partner country to adapt the initiative to local settings. This related predominantly to the number of participating GPs and patient invitation and communication. Using this protocol, all partner countries were able to source an eligible, target population.

-

3.3

If needed, education in the efficacy of selective prevention and training in the specific initiative protocol should be made available to health professionals and their staff.

A significant barrier to GP uptake of SPIs relates to their lack of training in communicating risk and lifestyle information to patients (Voogdt-Pruis et al., 2011; George et al., 2013; Ampt et al., 2009; Doolan-Noble et al., 2012; Krska et al., 2016; Critchley and Capewell, 2003). For those SPIs that include an IT component, insufficient GP training in IT functionality also represents a significant barrier. Noted facilitators of GP uptake include sufficient training in the given SPI protocol and motivational counseling more generally. Sufficient GP knowledge of the benefits of selective prevention also stands out as a key facilitator. In light of this, it would seem pertinent for any SPI to ensure that GPs have the knowledge and skill to execute the SPI protocol. This may be achieved by providing introductory training programs. In this context, it is also crucial that the protocol be absolutely clear and unambiguous with logical step-by-step instructions tailored to the given clinical setting (see Section 4.2 above).

-

4.Patients – motivating participation and engagement.

-

4.1Patient apprehensions related to potential health-check outcomes, should be anticipated and assuaged pre-implementation.

The evidence indicates that while worrying about one's health may inhibit preventive action (such as getting a health check), it can also have the opposite effect and facilitate this behavior – especially if the primary motivation is to ameliorate anxiety through reassurance and/or insight into individual risk (de Waard et al., 2018a; Wändell et al., 2018). Alleviating patients' uneasiness in regards to health-check outcomes is therefore an important factor in terms of facilitating patient uptake of CMD-SPIs (Koopmans et al., 2012; Griffith et al., 2012). While research on how to mitigate health-check anxieties is scarce, past findings indicate that unequivocal information about the nature and purpose of a health check might allay patient fears (Griffith et al., 2012). Similarly, GP-patient communication about the importance of preventive health checks also appears to be a central factor in assuaging patient worries and motivating uptake (de Waard et al., 2018a).-

4.1.1Reducing patient worries about health-check outcome by providing information: Past research indicates the value of educating people about three particular aspects of health screening (Griffith et al., 2012):

-

i.The nature and effects of the disease in focus (what are the symptoms? What is the prognosis? What are the causes/risk factors?)

-

ii.The relative risk of developing the disease (who is the high-risk population?),

-

iii.The benefits and procedure of a health check (how does one get a health check? What happens during/after the health check? What are the risks of not getting a health check?).

-

i.

Such information may be dispensed via media campaigns and public service announcements to the general public. Studies indicate that the efficacy of media campaigns might be significantly boosted if they are tailored to subgroups of the general populations (e.g. gender, age, race, culture) and channeled through TV, newspaper advertisements, and/or pamphlets (Griffith et al., 2012; Michie et al., 2011; Bandura, 2004).-

4.2Patients' feelings of powerlessness to affect their own health should be anticipated and counteracted before and during implementation.

We found that internal locus of control increased receptiveness to health checks. By contrast, perceived external locus of control had the opposite effect (Wändell et al., 2018). The extent to which patients feel able to influence their own health thus seems to underpin their openness to preventive action. Other research also indicates the importance of this factor in terms of sustained participation in behavioral medical interventions (Ghosh et al., 2014). As such, in an SPI it would likely be advantageous to empower the high-risk population by emphasizing the feasibility and potential of health-behavior change for reducing CMD risk. Below we list the central factors that should be taken into account.-

4.2.1Educating the high-risk population about the nature of CMD: In order to empower patients to manage their risk of CMD, educating them about the nature and progression of CMDs as well as behavioral risk factors, is imperative (Rabbone et al., 2005; Klabunde et al., 2005; Jotterand et al., 2016; Kolor, 2005). However, GPs often lack the necessary training to educate effectively in a clinical context (Jotterand et al., 2016). Thus, patient participation in CMD-SPIs may be bolstered by providing GP training in patient health education. This strategy should take into account tool 3.1 above concerning GPs' workload and scheduling issues. Providing patients at risk of CMD with additional practical CMD educational materials – such as information pamphlets, booklets, and/or media – may also help empower this population to take up CMD-SPIs.

-

4.2.2Providing support, advice, and guidance for behavior change: In addition to educating the high-risk population, providing continuous practical support to patients may similarly empower them and retain their participation over time. Past research has indicated that increased patient access to their GP clinic (e.g. via email and/or an IT-support system) for advice and guidance encourages health behavior considerably (Ghosh et al., 2014).

-

4.2.3Community health-behavior intervention: Another approach relates to mass-media awareness campaigns that target the high-risk population (Wakefield et al., 2010). These types of interventions are often based on actionable information dissemination and thus target individuals' self-efficacy and decision processes regarding a certain issue (e.g. health checks) (Larsen et al., In press; Bandura, 2004; Rimal, 2001; Maibach et al., 1991). Specifically, in contrast to people with high self-efficacy, those with low self-efficacy will most likely not be successful in changing their behavior in response to information about CMD alone (Michie et al., 2011; Bandura, 2004). However, if this information were accompanied by practical, stepwise instruction on how to change their behavior (i.e. instilling participants with a sense of self-efficacy), the probability of successful behavior change would likely be greater. Numerous studies support this premise (Michie et al., 2011; Ghosh et al., 2014; Rimal, 2001; Maibach et al., 1991).Finally, social norms within one's social network are also highly influential in terms of behavior. Research has shown strong, positive associations between the extent to which the individual perceives a certain behavior as norm-based, and his or her likelihood of engaging in that behavior (e.g. (Haslam et al., 2018; Jetten et al., 2012)). From this it follows that suggesting to the individual that similar others regularly engage in a given behavior (e.g. health checks) may implore him or her to follow suit. Examples of these types of interventions are numerous and effective (Bandura, 2004; Haslam et al., 2018; Jetten et al., 2012; Okechukwu et al., 2014; Emmons et al., 2007).

-

4.3Lack of patient knowledge in terms of the causes of and susceptibility to CMD, as well as its potential severity, should also be anticipated and counteracted pre-implementation.

In our WP B review (Wändell et al., 2018), feeling healthy and less vulnerable to CMD, and/or perceiving CMDs as less-debilitating conditions was associated with lower SPI-participation rates. While the former attitude may be well-founded (e.g. someone with a healthy lifestyle may in fact be less susceptible to CMD), the latter is surely based in misconception (OECD, 2017). Further, given the potential subtlety of CMD manifestation early in its development, it is not uncommon for people at elevated risk to feel healthy. People's misapprehensions about CMD may thus give rise to a false sense of health, and impact negatively on their motivation to take preventive action. In light of this, creating awareness around the risk and subtlety of CMD symptoms may boost participation rates in CMD-SPIs by motivating people who otherwise would have considered participation unnecessary. Priming the high-risk population by disseminating information about the causes and nature of CMDs may thus encourage preventive action. This may be accomplished by employing health promotion strategies akin to those outlined in Recommendation 4.2 above.-

4.4Patients' potential time constraints (work/family, etc.) and/or other practical obstacles (geography, financial, etc.) may impact on their likelihood of showing up for a health check and should be accommodated to the furthest extent possible throughout implementation.

Our WP B review indicated that lack of time (due to family and/or work) was a significant barrier, whereas working flexible hours or being retired (and thus having more free time) facilitated health checks (Wändell et al., 2018). These findings dovetailed nicely with our other results that indicated that walk-in health checks and easy geographical access to a GP facilitated participation in health checks. Further, we also found that low SES might facilitate health check attendance in one setting, but inhibit it in another (high SES was consistently a facilitator). Overall, our findings highlight the fact that time and access issues, as well as SES, can impact significantly on the likelihood of patients attending health checks. While past research indicates difficulty in circumventing these issues, there are some options that may be advantageous to incorporate in an SPI.-

4.4.1Support staff: The amount of time and resources that GPs have at their disposal is directly related to their availability for appointments. This may account for some of the difficulty in booking appointments reported by patients constrained by time issues. Similar to tool #3.1 above, this might be dealt with by employing support staff. Past research has suggested different types of assistance for this purpose, typically including patient navigators, physician assistants, or nurse-led initiatives (Griffith et al., 2012). Here, non-GP staff take on various duties (including basic health checks) to off-load the GP and create greater access for patients (Peart et al., 2018). These initiatives necessarily rely on relatively extensive training and detailed protocols so that the given support staff may tackle whatever responsibilities they are tasked with effectively (e.g. a health check).

-

4.4.2After-hours access: Currently there are various after-hours primary-care models implemented in Europe. Many of these involve after-hours primary-care centers or primary-care cooperatives. The former model involves primary-care centers where patients can present with or without an appointment. In the latter model, GPs within a region or municipality form multiple, rotating groups which, with the support of auxiliary staff, provide primary care in large, non-profit organizations (Grol et al., 2006). The latter model is currently implemented in Denmark and the Netherlands (Grol et al., 2006; Giesen et al., 2011) and has been somewhat instrumental in off-loading GPs' workloads and alleviating busy emergency departments (O'Malley, 2012). However, systems like these may serve a third purpose by allowing patients, who cannot schedule preventive health checks during normal working hours, to make appointments at an after-hours clinic or cooperative. Dependent on local resources, however, SPIs may need to employ extra staff for this specific purpose (particularly for walk-in centers where appointments are not possible).

-

4.4.3Mobile health service/reimbursement of transportation costs: Our findings suggested that lack of geographical access to a GP and/or health center significantly impedes patients who might otherwise be motivated and willing to get a health check (Wändell et al., 2018). Similar discoveries have also been made in past research (Hibbard et al., 2013; Fortney et al., 1995). This issue may be of particular relevance in rural or suburban settings, or in cities with poor public-transport systems. Potential solutions to this barrier may be for GPs to offer home visits and/or organize regular (e.g. annual) mobile-health clinics that cater to health-check demands. These approaches have shown some success in past research focusing on hard-to-reach populations (Liang et al., 2005; Leese et al., 2008).

-

4.5Method of invitation to participate in the SPI should be evidence-based and optimally consist of an invitation from the patient's GP, supplemented with information on the purpose and nature of a health check.

Our findings suggest that the method and content of the invitation to the initiative is a central factor in patients' choice to participate or not (Wändell et al., 2018). Effective invitation methods generally included receiving a personal invite from the GP or health center which, if not responded to, was followed up with a reminder or second invitation. The use of outreach workers in the invitation process was also identified as a facilitator. Indeed, in our feasibility study (WP E) (Lionis et al., 2018) four countries sent out paper invitations, addressed to the patient from the research team (i.e. an unknown entity to the patient). This resulted in a relatively low response rate, ranging from 30% to 50%. The Czech team, however, instructed GPs to invite their patients personally by letter or during consultation. This resulted in a 100% response rate. On this basis, it seems the invitation method of a given SPI is key to patient recruitment.-

4.5.1Three-step invitation process

Our review indicates that a basic three-step invitation process may maximize response and uptake rate:-

1.Patients should be invited by their GP.

-

2.Non-responders should be followed up with a second invitation or reminder to respond.

-

3.The invitation should be supplemented with clear and specific information about the purpose, benefits, and specific content of a health check.

-

4.1

4. Discussion

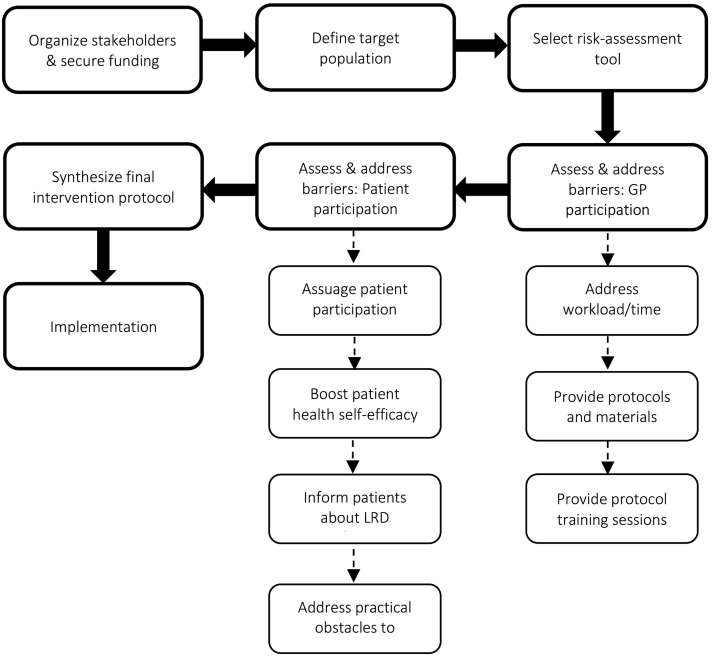

We set out to create a generic, yet tailorable toolbox for the design and implementation of CMD-SPIs. To this end, we reviewed past and present SPIs, examined facilitators and barriers to SPI uptake among both health professionals and patients, and tested the feasibility of a generic SPI model in five different countries. Based on our findings as well as the extant literature, we generated a set of generic recommendations and tools – listed above – which we hope will help develop and focus current and future SPIs. We found definite commonalities in terms of the obstacles and facilitators of CMD-SPIs across national contexts. However, given the systemic, attitudinal, and cultural differences between countries, the proposed toolbox may not always apply equally across the board. For example, tool #3.1.3 (incentivizing GP participation) may not be particularly useful in a country such as Denmark where there currently is a relatively large patient-to-GP ratio. That is, many Danish GPs are encumbered by heavy workloads and tight schedules, and may thus be reluctant to take on more work regardless of monetary incentives. Indeed, in this scenario, introducing support staff (tool #3.1.2) or sharing the extra workload with other primary-care agents (tool #3.1.1) may be more appropriate and effective. By contrast, other tools have broader relevance and value regardless of systemic or national context. For instance, tool #4.2.3 (community health-behavior intervention) targets rather fundamental human psychological dynamics (i.e. self-efficacy, motivation, social norms) that are pertinent to behavior change in a broad range of cultural and national settings (Wakefield et al., 2010; Haslam et al., 2018; Jetten et al., 2012; Montano and Kasprzyk, 2015). In this way, the presented recommendations may highlight more or less omnipresent issues, but the extent to which these can be dealt with using the suggested tools (or at all) may differ depending on local settings. In other words, an entirely generic, one-size-fits-all solution to the design and implementation of CMD-SPIs, may be impractical if not impossible in a European context. In all likelihood, certain components of a given SPI will nearly always need to be tailored to the specific national context and system in which they will be implemented. As such, while we have presented a set of general recommendations and tools, the onus is ultimately on the stakeholders of a given SPI to decide which tools are relevant to their particular program, and how these tools are best tweaked and implemented in the relevant setting. In Fig. 1 below, we have provided an overview process flowchart of how the toolbox might be implemented.

Fig. 1.

Overview flowchart of toolbox implementation process.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

One of the main strengths of this toolbox is the comprehensiveness of the WPs that inform each of the recommendations and tools outlined above. The vast majority of our evidence was collected in the five SPIM-EU countries (the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, Greece, Sweden, and Denmark), which collectively are good representations of the different types of health care systems that currently exist in Europe (see Table 1). As such, the recommendations and tools that we have developed based on SPIMEU data, presumably apply or can be adapted to many different settings within the EU.

Another strength relates to the methodological rigor of each of the empirical studies that underpin the toolbox. In particular, we conducted three reviews (one based on key informants and experts) (Hollander and de Waard, In press), as well as two systematic literature reviews (de Waard et al., 2018a; Wändell et al., 2018), two multi-national survey studies (de Waard et al., 2018b), an international expert consensus meeting (Kral et al., In press), and a multi-national feasibility study (Lionis et al., 2018) (see Table 2). The systematic reviews were executed according to validated review guidelines. Similarly, the consensus meeting was conducted using the validated Rand/UCLA appropriateness method (the RAM) (Fitch et al., 2001) and included 14 internationally renowned experts in cardiology, epidemiology, and/or general practice. Finally, the feasibility study directly tested the practicality of implementing a generic SPI in each SPIM-EU country. The collection of high-quality evidence generated in each of these WPs, places us in a unique position to create an evidence-based, state-of-the-art SPI toolbox.

In terms of limitations, we have not yet conducted any follow-up studies. This has left a few questions that emerged from our initial findings unanswered. For example, the association between SES and the likelihood of engaging in preventive health behavior was quite ambiguous, with some studies indicating a positive relationship and others a negative one. Given the social inequality in lifestyle-related disease that currently exists in most of the world, not least in the EU (Mackenbach et al., 2008; Di Cesare et al., 2013; Dalstra et al., 2005; Galobardes et al., 2003; Cooper, 2001), it would certainly seem germane to examine this relationship further to clarify exactly how these two variables relate.

Another limitation relates to the validation of the toolbox. That is, while the recommendations and tools listed above have been derived from the evidence, some have as yet not been tested. For example, while past research may suggest that mobile health-check services (tool #4.4.3) might get at hard-to-reach populations, this has – to our knowledge – not been attempted in the context of SPI implementation. We therefore strongly encourage potential users of this toolbox to record their implementation methods and results for evaluation and amendment purposes. A concerted and sustained effort to revise and update this toolbox will secure its relevance and applicability over time.

4.2. Future directions

While this toolbox is comprehensive in scope, there are nonetheless certain matters that we have been unable to draw firm conclusions about. One issue that is particularly worth noting relates to GP (de)motivation to participate in SPIs. In the above sections we have identified various barriers, including insufficient funding, increased workload, lack of knowledge of available protocols, etc. However, another factor that may dissuade GPs from engaging with SPIs might relate to more fundamental matters. Particularly, we believe that the somewhat ambiguous nature of the evidence for the effectiveness of such programs (e.g. in terms of cost-effectiveness, feasibility, high-risk population identification, health check invitation and attendance) likely plays a significant role in the extent to which GPs choose to participate or not. For instance, the cost-effectiveness of SPIs has yet to be conclusively demonstrated, and while some studies indicate a positive impact of SPIs on health and health behavior, others report small, mixed, or no effects (Van der Meer et al., 2013; Li et al., 2008). Thus, we argue that this opacity in the evidence base may contribute to GPs' reluctance to participate in SPIs. To remedy this situation more research is needed to clearly identify the value and feasibility of SPIs in combating CMD. To this end, we propose three main avenues for future research: 1) High-quality studies (e.g. stepped-wedge trials) that account for the various limitations of past research. 2) Assessing the effectiveness of current and past SPI programs (e.g. a metaanalysis of those programs identified in Hollander & de Waard (Hollander, In press (Kral et al., In press)) that also report effect sizes) in terms of feasibility, cost-effectiveness, effectiveness of patient invitations, health-check attendance, and overall health outcomes over time. 3) Encouraging current and future SPIs to incorporate comprehensive and rigorous impact evaluation components as core features in their programs.

Disclaimer

The content of this protocol represents the views of the author only and is his/her sole responsibility; it cannot be considered to reflect the views of the European Commission and/or the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency or any other body of the European Union. The European Commission and the Agency do not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains.

Funding

This protocol is part of the project/joint action ‘663309/SPIM EU’ which has received funding from the European Union's Health Program (2014–2020).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests with the publication of this material.

References

- Ampt A.J. Attitudes, norms and controls influencing lifestyle risk factor management in general practice. BMC Fam. Pract. 2009;10(1):59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-10-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arena R. Healthy lifestyle interventions to combat noncommunicable disease—a novel nonhierarchical connectivity model for key stakeholders: a policy statement from the American Heart Association, European Society of Cardiology, European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, and American College of Preventive Medicine. Eur. Heart J. 2015;36(31):2097–2109. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ. Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björck L. Modelling the decreasing coronary heart disease mortality in Sweden between 1986 and 2002. Eur. Heart J. 2009;30(9):1046–1056. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotons C. Prevention and health promotion in clinical practice: the views of general practitioners in Europe. Prev. Med. 2005;40(5):595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper R.S. Social inequality, ethnicity and cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2001;30(suppl_1):S48. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.suppl_1.s48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley J.A., Capewell S. Mortality risk reduction associated with smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;290(1):86–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalstra J.A. Socioeconomic differences in the prevalence of common chronic diseases: an overview of eight European countries. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005;34(2):316–326. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waard A.-K.M. Barriers and facilitators to participation in a health check for cardiometabolic diseases in primary care: a systematic review. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2018;25(12) doi: 10.1177/2047487318780751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waard A.-K.M. Selective prevention of cardiometabolic diseases: activities and attitudes of general practitioners across Europe. Eur. J. Pub. Health. 2018;29(1) doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J. Summary of the practice guideline'the prevention visit'from the Dutch College of General Practitioners. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 2011;155(18):A3428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cesare M. Inequalities in non-communicable diseases and effective responses. Lancet. 2013;381(9866):585–597. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61851-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl K. Physician gender and lifestyle counselling to prevent cardiovascular disease: a nationwide representative study. Journal of Public Health Research. 2015;4(2) doi: 10.4081/jphr.2015.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolan-Noble F., Tracey J., Mann S. Why are there gaps in our management of those with high cardiovascular risk? Journal of Primary Health Care. 2012;4(1):21–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons K.M. Social influences, social context, and health behaviors among working-class, multi-ethnic adults. Health Educ. Behav. 2007;34(2):315–334. doi: 10.1177/1090198106288011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante D. Barriers to prevention of cardiovascular disease in primary care settings in Argentina. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica. 2013;33:259–266. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892013000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch K. RAND CORP; SANTA MONICA CA: 2001. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User's Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Fortney J.C. The effects of travel barriers and age on the utilization of alcoholism treatment aftercare. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1995;21(3):391–406. doi: 10.3109/00952999509002705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galobardes B. Trends in risk factors for lifestyle-related diseases by socioeconomic position in Geneva, Switzerland, 1993–2000: health inequalities persist. Am. J. Public Health. 2003;93(8):1302–1309. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George P.P. Right-siting chronic kidney disease care-a survey of general practitioners in Singapore. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2013;42(12):646–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh K. Communications of the Association for Information Systems. Vol. 34. 2014. Media reinforcement for psychological empowerment in chronic disease management; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Giesen P. Quality of after-hours primary care in the Netherlands: a narrative review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011;155(2):108–113. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith K.A. African Americans with a family history of colorectal cancer: barriers and facilitators to screening. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2012;39(3):299–306. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.299-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R., Giesen P., van Uden C. After-hours care in the United Kingdom, Denmark, and the Netherlands: new models. Health Aff. 2006;25(6):1733–1737. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.6.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam C. Routledge; 2018. The New Psychology of Health: Unlocking the Social Cure. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard J.H., Greene J., Overton V. Patients with lower activation associated with higher costs; delivery systems should know their patients' ‘scores’. Health Aff. 2013;32(2):216–222. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander M., de Waard A.K.M. A survey of selective cardio-metabolic prevention programs in Europe. European Journal of Primary Care. 2019 In press. xx(xx): p. xx-xx. [Google Scholar]

- Jetten J., Haslam C., Haslam A. Psychology Press; 2012. The Social Cure: Identity, Health and Well-being. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen T. Effect of screening and lifestyle counselling on incidence of ischaemic heart disease in general population: Inter99 randomised trial. Br. Med. J. 2014;348:g3617. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jotterand F., Amodio A., Elger B.S. Patient education as empowerment and self-rebiasing. Med. Health Care Philos. 2016;19(4):553–561. doi: 10.1007/s11019-016-9702-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesteloot H., Sans S., Kromhout D. Dynamics of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in Western and Eastern Europe between 1970 and 2000. Eur. Heart J. 2005;27(1):107–113. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klabunde C.N. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of reports from primary care physicians and average-risk adults. Med. Care. 2005:939–944. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000173599.67470.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolor B. Patient education and treatment strategies implemented at a pharmacist-managed hepatitis C virus clinic. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy. 2005;25(9):1230–1241. doi: 10.1592/phco.2005.25.9.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans B. Non-participation in population-based disease prevention programs in general practice. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):856. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Král N., de Waard A.K.M., Schellevis F.G., Korevaar J.C., Lionis C., Carlsson A.C., Larrabee Sonderlund A., Sondergaard J., Larsen L.B., Hollander M., Thilsing T., Angelaki A., de Wit N., Seifert B. What should selective cardiometabolic prevention programmes in European primary care look like? A consensus-based design by the SPIMEU group. European Journal of General Practice. 2019:1–8. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2019.1641195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kringos D. The strength of primary care in Europe: an international comparative study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013;63(616):e742–e750. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X674422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krska J., du Plessis R., Chellaswamy H. Views of practice managers and general practitioners on implementing NHS Health Checks. Primary Health Care Research & Development. 2016;17(2):198–205. doi: 10.1017/S1463423615000262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, L.B., Sondergaard, J., Thomsen, J. L., Halling, A., Sonderlund, A. L., Christensen, J. R., & Thilsing, T., Personal digital health profiles and attendance in a step-wise model to prevent chronic disease - a cross-sectional study of patient characteristics, health care usage, and uptake of a targeted intervention. Fam. Pract., (Under review).

- Leese G.P. Screening uptake in a well-established diabetic retinopathy screening program: the role of geographical access and deprivation. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(11):2131–2135. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. The long-term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 20-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;371(9626):1783–1789. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60766-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang T.S. Rapid HIV testing of clients of a mobile STD/HIV clinic. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2005;19(4):253–257. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lionis C., Angelaki A., Bertsias A. Final report on feasibility studies - SPIMEU deliverable 8.3. 2018. http://spimeu.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2018/09/Deliverable-8.3-Report-of-the-feasibility-study-1.pdf

- Mackenbach J.P. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358(23):2468–2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maibach E., Flora J.A., Nass C. Changes in self-efficacy and health behavior in response to a minimal contact community health campaign. Health Commun. 1991;3(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Michie S., Van Stralen M.M., West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011;6(1):42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montano D.E., Kasprzyk D. Health Behavior: Theory, Research and Practice. 2015. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model; pp. 95–124. [Google Scholar]

- Nielen M. An evidence-based cardiometabolic health check in general practice. Huisarts Wet. 2011;54:414–419. [Google Scholar]

- OECD . 2017. Health at a Glance 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Okechukwu C., Davison K., Emmons K. Social Epidemiology. 2014. Changing health behaviors in a social context; p. 365. [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley A.S. After-hours access to primary care practices linked with lower emergency department use and less unmet medical need. Health Aff. 2012;32(1):175–183. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peart A. Patient navigators facilitating access to primary care: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbone I. Role of health care providers in educational training of patients with diabetes. Acta bio-medica: Atenei Parmensis. 2005;76:63–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimal R.N. Perceived risk and self-efficacy as motivators: understanding individuals' long-term use of health information. J. Commun. 2001;51(4):633–654. [Google Scholar]

- Rosamond W. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2008 update. Circulation. 2008;117(4):e25–e146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unal B., Critchley J.A., Capewell S. Modelling the decline in coronary heart disease deaths in England and Wales, 1981–2000: comparing contributions from primary prevention and secondary prevention. Br. Med. J. 2005;331(7517):614. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38561.633345.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meer V. Cardiometabolic prevention consultation in the Netherlands: screening uptake and detection of cardiometabolic risk factors and diseases–a pilot study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013;14(1):29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voogdt-Pruis H.R. Experiences of doctors and nurses implementing nurse-delivered cardiovascular prevention in primary care: a qualitative study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011;67(8):1758–1766. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield M.A., Loken B., Hornik R.C. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet. 2010;376(9748):1261–1271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wändell P.E. Barriers and facilitators among health professionals in primary care to prevention of cardiometabolic diseases: a systematic review. Fam. Pract. 2018;35(4):383–398. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmx137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild S. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(5):1047–1053. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . WHO Regional Office for Europe; Copenhagen, Denmark: 2017. Diabetes-data and Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2017. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs) Fact Sheet. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part II: variations in cardiovascular disease by specific ethnic groups and geographic regions and prevention strategies. Circulation. 2001;104(23):2855–2864. doi: 10.1161/hc4701.099488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S. The World Heart Federation's vision for worldwide cardiovascular disease prevention. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):399–402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]