Re-opening of the culprit epicardial coronary artery in the early phase of an acute myocardial infarction does not mandatorily translate into an effective myocardial reperfusion. This is the case of the so-called “no-reflow phenomenon”, which refers to the failure to restore perfusion to the microvasculature supplying the myocardium, generally due to thrombotic occlusion of the pre-capillary and capillary bed. In ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), the incidence of no-reflow has been reported to be comprised between 11 and 41%, with a variability depending on patient, vessel, and lesion factors [1] Its appearance is associated with a worse prognosis, especially in term of short and long mortality [2,3]. Angiographic diagnosis requires documentation of an impaired (≤2) Myocardial Blush Grade (MGB), whereas a preserved TIMI flow (grade 3) alone, although associated with a lower risk of no-reflow, is not sufficient. Since there is no definitive treatment of no-reflow once it has occurred, prevention plays a pivotal role to avoiding this harmful complication. Although the mechanisms determining no-reflow are not still completely understood, it is now clear that its pathogenesis is multifactorial. In fact, injury related to ischemia, reperfusion, endothelial dysfunction, distal thromboembolism and microvascular spasm are considered the principal underlying determinants [4]. A number of clinical, serologic, angiographic and procedural parameters have been identified in several studies as predictors of no-reflow. Due to heterogeneity of the populations studied, there is a disagreement on the relative importance of some of these parameters. Not surprisingly, a high thrombus burden increases the risk of no-reflow [5,6], due to dislodgement of atherothrombotic debris causing distal embolization [7]. However, thrombus burden is only one predictor of no re-flow with other mechanisms that have to be searched in the concomitant presence of multiple, especially clinical, pro-thrombotic and/or pro-inflammatory patient characteristics. In fact, Mazhar et al. [6] showed in a cohort of 781 patients underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) that no-reflow occurred more frequently in the older (>60 years), in the presence of high thrombus burden and in case of delayed presentation from symptom onset (>4 h). Interestingly, no lesion and pharmacological associations were documented. Recently, a study of Mahmoud et al. [8] confirmed the importance of clinical and serological no-reflow predictors: among these, the authors described a high thrombus burden, a high total leucocytes count (>10,103/mm3), a high blood glucose level (>160 mg/dl) and a delayed reperfusion. In conjunction, also some procedural variables (repeated balloon inflations and high predilatation pressure) were associated with the incidence of no-reflow. The findings have been confirmed in other investigations, underlying the predominant importance of patient-related pro-thrombotic status, showing a strict link between some characteristics. Del Turco and Colleagues [9] demonstrated that elderly patients (>65 years) suffer from higher rates of no-reflow, attributable to a more pronounced pro-inflammatory state, defined by presence of higher mean values of fibrinogen, brain natriuretic peptide, leukocytes, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and C reactive protein-albumin ratio. Moreover, in a large cohort of patients undergoing pPCI, Ashraf et al. [10], found that age, diabetes, prior history of coronary artery bypass grafting, higher thrombus burden and longer lesion length were independent predictors of no-reflow. Corroborating the idea that more pronounced the patient-related thrombotic diathesis, higher the risk of suboptimal reperfusion, Kaya et al. [11] showed that the presence of atrial fibrillation is associated with 2-fold increase of risk to develop no-reflow in STEMI patients. Thus, optimal blood sugar control in patients with diabetes [12] and intensive statin therapy in those with hyperlipidemia [13] before the procedure can reduce the occurrence of no-reflow. Although these general measures are simple, their benefits are limited in individuals with acute presentation of STEMI, making prevention of re-flow more difficult in this subgroup compare than stable coronary artery patients.

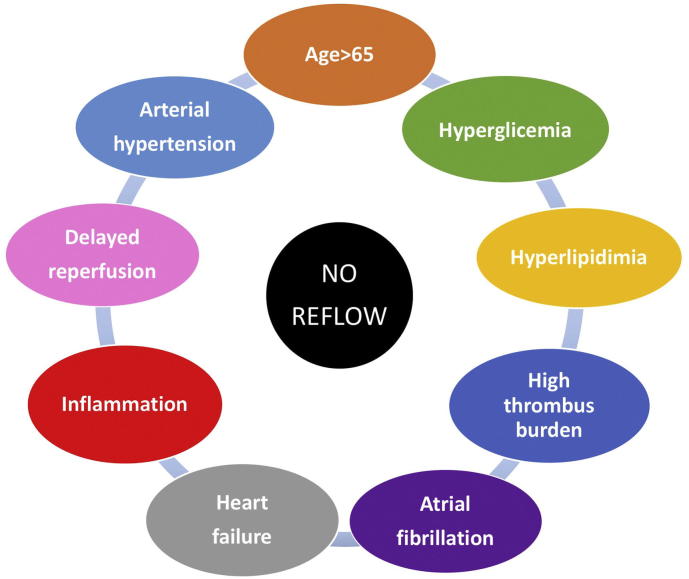

In this issue of IJC Heart & Vasculature, Stambuk et al. [14] provide new evidence insight the role of intracoronary contrast injection pressure on reperfusion during pPCI in STEMI patients. In a well-conducted prospective pilot study, Authors enrolled 100 patients and randomized them to a higher (550 pound/in.2) or lower (200 pound/in.2) injection pressure group, assessing the potential association between injection pressure and suboptimal reperfusion incidence. Baseline characteristics, comprising well-known clinical predictors of no-reflow, were homogeneously distributed between the two groups. The authors found that contrast injection pressure is not associated with the grade of myocardial reperfusion, assessed by MBG or ST segment changes in the ECG. In another words, microvascular distal embolization is not provoked by a higher pressure contrast injection. Overall incidence of reported suboptimal reperfusion (intended as MBG ≤ 2) was 31%. This subgroup of patients compared than patients who achieved a MBG 3, were older, with a more frequent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation and heart failure, confirming the hypothesis of a clinical predisposition to no-reflow. It should be noted that the authors conducted the study using routine GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors during the procedure. Of note, the recent ESC Guidelines on myocardial revascularization [15] recommend these drugs only in bail-out settings. Whether the systematic use of GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors in this study influenced the results, and whether injection pressure might have had a different effect in their absence, remains open for speculation. In conclusion, the current findings shed new light on no-reflow predictors' investigation: more than with procedural variables, no-reflow seems to be strictly linked with patient's pro-thrombotic and pro-inflammatory characteristics (Fig. 1). So, it's time to relieve pressure from the procedure, focusing our attention on the patient!

Fig. 1.

Clinical predictors of no-reflow.

References

- 1.Harrison R.W., Aggarwal A., Ou F.S., Klein L.W., Rumsfeld J.S., Roe M.T. Incidence and outcomes of no-reflow phenomenon during percutaneous coronary intervention among patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2013;111(2):178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choo E.H., Kim P.J., Chang K., Ahn Y., Jeon D.S., Lee J.M., Kim D.B., Her S.H., Park C.S., Kim H.Y., Yoo K.D., Jeong M.H., Seung K.B. The impact of no-reflow phenomena after primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a time-dependent analysis of mortality. Coron. Artery Dis. 2014;25(5):392–398. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000108. Aug. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ndrepepa G., Tiroch K., Fusaro M., Keta D., Seyfarth M., Byrne R.A. 5-year prognostic value of no-reflow phenomenon after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010;55(21):2383–2389. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rezkalla S.H., Stankowski R.V., Hanna J., Kloner R.A. Management of no-Reflow Phenomenon in the catheterization laboratory. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(3):215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.11.059. Feb 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong-bao L., Qi H., Zhi L., Shan W., Wei-ying J. Predictors and long-term prognosis of angiographic slow/no-reflow phenomenon during emergency percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevated acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Cardiol. 2010;33(12):E7–12. doi: 10.1002/clc.20634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazhar J., Mashicharan M., Farshid A. Predictors and outcome of no-reflow post primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2015;10:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2015.11.002. Nov 6. (eCollection 2016 Mar) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niccoli G., Burzotta F., Galiuto L., Crea F. Myocardial no-reflow in humans. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;54(4):281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahmoud A.H., Taha N.M., Baraka K., Ashraf M., Shehata S. Clinical and procedural predictors of suboptimal myocardial reperfusion in primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2019 Apr 19;23 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2019.100357. (eCollection 2019 Jun) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Turco S., Basta G., De Caterina A.R., Sbrana S., Paradossi U., Taddei A., Trianni G., Ravani M., Palmieri C., Berti S., Mazzone A. Different inflammatory profile in young and elderly STEMI patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI): its influence on no-reflow and mortality. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019;290:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.05.002. Sep 1. (Epub 2019 May 3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashraf T., Khan M.N., Afaque S.M., Aamir K.F., Kumar M., Saghir T., Rasool S.I., Rizvi S.N.H., Sial J.A., Nadeem A., Khan A.A., Karim M. Clinical and procedural predictors and short-term survival of patients with no reflow phenomenon after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.07.067. Jul 23. pii: S0167-5273(19)32691-9. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaya A., Keskin M., Tatlisu M.A., Uzman O., Borklu E., Cinier G., Yildirim E., Kayapinar O. Atrial fibrillation: a novel risk factor for no-reflow following primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Angiology. 2019 doi: 10.1177/0003319719840589. Apr 8:3319719840589. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malmberg K., Rydén L., Efendic S. Randomized trial of insulin-glucose infusion following by subcutaneous insulin treatment in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction (DIGAMI study): effects on mortality at 1 year. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1995;26:57–65. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00126-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X.D., Yang Y.J., Hao Y.C. Effects of pre-procedural statin therapy on myocardial noreflow following percutaneous coronary intervention: a metaanalysis. Chin. Med. J. 2013;126:1755–1760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stambuk K., Tomislav Krcmar T., Zeljkovic I. Impact of intracoronary contrast injection pressure on reperfusion during primary percutaneous coronary intervention in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a prospective randomized pilot study. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2019;24 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2019.100412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neumann F.J., Sousa-Uva M., Ahlsson A., Alfonso F., Banning A.P., Benedetto U., Byrne R.A., Collet J.P., Falk V., Head S.J., Jüni P., Kastrati A., Koller A., Kristensen S.D., Niebauer J., Richter D.J., Seferovic P.M., Sibbing D., Stefanini G.G., Windecker S., Yadav R., Zembala M.O., ESC Scientific Document Group 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur. Heart J. 2019;40(2):87–165. Jan 7. [Google Scholar]