Abstract

This report provides an update from the U.S. Department of Agriculture - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sentinel Foods Surveillance Program, exploring changes in sodium and related nutrients (energy, potassium, total and saturated fat, and total sugar) in popular, sodium-contributing, commercially processed and restaurant foods with added sodium. In 2010–2013, we obtained 3432 samples nationwide and chemically analyzed 1654 composites plus label information for 125 foods, to determine baseline laboratory and label sodium concentrations, respectively. In 2014–2017, we re-sampled and chemically analyzed 43 of the Sentinel Foods (1181 samples), tested for significant changes of at least ±10% (p < 0.05), in addition to tracking changes in labels for 108 Sentinel Foods. Our results show that the label sodium levels of a majority of the Sentinel Foods had not changed since baseline (~1/3rd of the products reported changes, with twice as many reductions as increases). Laboratory analyses of the 43 Sentinel Foods show that eight foods had significant changes (p < 0.05); sodium content continues to be high and variable, and there was no consistent pattern of changes in related nutrients. Comparisons of changes in labels and laboratory sodium shows consistency for 60% of the products, i.e., similar changes (or no changes) in laboratory and label sodium content. The data from this monitoring program may help public health officials to develop strategies to reduce and monitor sodium trends in the food supply.

Keywords: sodium, food composition, hypertension, sodium reduction, monitoring, variability, FDA sodium reduction targets

1. Introduction

High sodium intake has been linked to increased chronic disease risk, especially for cardiovascular diseases [1,2,3]. Americans (>14 years of age) consume over 3400 mg/day on average [4], i.e., about 50% more sodium than the recommended limit of less than 2300 mg/day in the 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) [5], Healthy People 2020 [6], and the 2019 Dietary Reference Intake level recommended for Chronic Disease Risk Reduction [1]. The majority of the sodium intake in the U.S. is from commercially processed and prepared foods with added sodium [7,8]. Hence, national and international public health agencies consider reducing sodium content of these foods to be a cost-effective public health strategy [9,10,11]. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) in 2010 recommended gradual reduction in sodium content, mandatory targets for reducing sodium in these foods, and mechanisms to monitor sodium in the food supply [12]. The New York Salt Reduction Initiative (NSRI), a public-private collaboration, set voluntary sodium targets in 2009 for several packaged and restaurant food categories. Many food manufacturers and restaurant chains in the U.S. pledged to reduce sodium in their products [13,14,15,16,17]. In 2016, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued draft voluntary targets (short-term (2 year) and long-term (10 year)) for reducing sodium for 150 food categories, and estimated that their implementation would reduce sodium intakes to about 3000 mg/day over 2 years and about 2300 mg/day over 10 years [18].

In 2010, in response to the IOM recommendations to enhance monitoring and surveillance of sodium content of foods, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), initiated the Sentinel Foods Surveillance Program. Under this program, the Nutrient Data Laboratory (NDL) of USDA initiated tracking 125 Sentinel Foods using multiple means, to assess changes in their sodium contents. The list included foods such as cheddar cheese, white bread, macaroni and cheese, french fries, representing several food types and both packaged and prepared/restaurant food sources. These foods were sampled nationwide mainly in 2010–2013, and chemically analyzed in the laboratory for ‘baseline’ sodium contents [19]. In addition to sodium, the following nutrients were also tracked, as they are most likely to change as manufacturers reformulate—energy, potassium, total and saturated fat, and total sugar, henceforth referred to as ‘related nutrients’ [12]. The complete list of Sentinel Foods, the monitoring plan and its details have been published [20], and are summarized later in the ‘Methods’ section of the paper. Thereafter, NDL was to track the foods annually using information from food manufacturers such as manufacturer or restaurant websites, food labels etc. (referred to as labels hereafter), and resample the Sentinel Foods nationwide and chemically analyze them at periodic intervals.

The objective of this report is to provide an update of results from USDA-CDC Sentinel Foods Surveillance Program, exploring changes in sodium and related nutrients in selected commercially processed packaged and restaurant foods, using dual methods - food labels and laboratory analyses. We compared results from the two methods to provide insights into changes in the marketplace and the monitoring methodologies. Furthermore, we compared the resampled laboratory sodium values to the FDA’s draft voluntary sodium-reduction targets and sodium limits for ‘healthy’ foods (as done for baseline sodium contents [19]).

2. Methods

2.1. Selection of Sentinel Foods

The 125 Sentinel Foods were selected in 2010 to serve as indicators for assessing changes or temporal trends. They are comprised of commercially processed packaged foods (92 of 125) and prepared (fast food or restaurant) foods (33 of 125). Their selection was based on evaluation of sodium concentration (mg/100 g of food), frequency of consumption by respondents in the national survey (What We Eat In America (WWEIA), NHANES 2007–2008), and percentage of contribution to sodium intake, and accounted for approximately one-third of total sodium intake of the U.S. population, excluding breast-fed infants [20]. These foods continue to be popular as indicated in the latest survey (WWEIA, NHANES 2015–2016) [21]. The complete list of the 125 Sentinel Foods is available in Supplemental Table S1. The foods are grouped by food type, adapted from WWEIA Food Categories [22], for purposes of presenting the data.

2.2. Assessment of Baseline Sodium Content

NDL sampled and analyzed the Sentinel Foods staggered over the years 2010–2013 (supplemental sampling for three foods-canned corn, cheddar cheese and mozzarella cheese was done in 2014), using the protocols established under the National Food and Nutrient Analysis Program [23,24]. The salient features of the program include use of a statistically valid, 3-stage probability-proportional-to-size sampling plan, laboratory analysis of foods using valid, approved methods by pre-qualified laboratories, and multi-step quality control reviews by chemists and nutritionists. NDL developed a sampling plan for each Sentinel Food, using the most recent census data to identify cities and counties, store-based retail sales data to identify retail stores, and most recent consumer point-of-sale Nielsen data [25] to determine the market share of the brands, and the top brands to sample. Using the sampling plan, NDL purchased 3432 samples of the 125 Sentinel Foods from high-sales retail outlets at up to 12 locations nationwide (See Scheme 1). The samples included national and private-label (store brands) for the packaged foods. Prepared foods were sampled from major fast food, family-style restaurants and local restaurants, as appropriate. The sampling process and selection of brands and restaurants are detailed elsewhere [20].

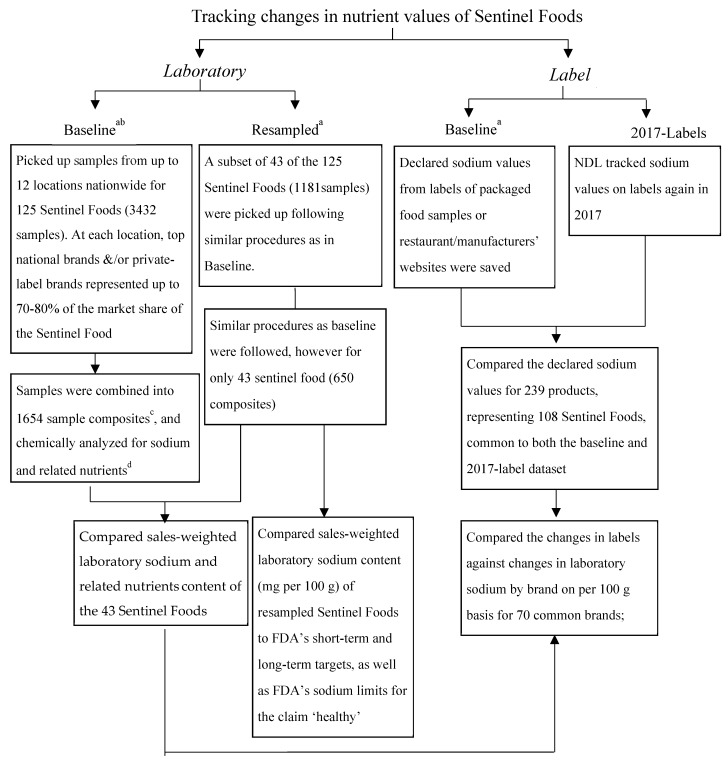

Scheme 1.

Summary of the steps, methods, and sample sizes used for tracking changes in nutrient values, as a flow chart. a Baseline Sentinel Foods were sampled in 2010–2013 and resampled in 2014–2017. b Please see Reference [20] for details on sampling plan and chemical analysis methodology. c Composite-homogenized one or more samples of the same food. d Related nutrients studied-energy, potassium, total and saturated fat, and total sugar.

The purchased samples were shipped to laboratories at Virginia Tech or Texas Tech Universities and prepared as per package directions (if needed). One or more samples, mostly of the same brand but two different locations, were further combined and homogenized into 1654 composites, to reduce cost of chemical analyses (See Scheme 1). These composites were shipped, along with blinded matrix-matched in-house or standard reference quality control materials to pre-qualified laboratories to measure sodium, potassium, total fat, saturated fat, total sugars, total nitrogen, moisture, ash, and alcohol (if applicable) concentrations per 100 g, among others. Not all composites were analyzed for all nutrients, to save on laboratory costs. For example, canned tuna and bacon were not analyzed for total sugar, and concentration was assumed to be zero. The methods of analysis and sample sizes for each nutrient/food component are listed in Supplemental Table S2. The results from chemical analysis were reviewed by chemists and nutritionists, and validated against the results from blinded reference materials [26]. NDL calculated carbohydrate by difference for each of the composites using the equation: Total carbohydrate by difference = 100 − [water, protein, total lipid, ash, and alcohol in g/100 g], and total energy based on the Atwater system [27]. The nutrient contents for sodium and related nutrients of the composites were then weighted by market share of the brands of the composites to determine nationally representative sales-weighted nutrient contents for the Sentinel Foods, using the following equation, sales-weighted mean = ∑wx/∑w, where w represents the market share of the brand of the composite, determined using point-of-sales data, and x refers to the analytical nutrient content of the composite.

Information on the nutrition facts panel (NFP) from packaged food samples or from restaurant websites, if available (henceforth referred to as labels), were saved for 110 Sentinel Foods. These generally included major national brands and 1–2 private-label brands. No labels were available for 15 foods, mainly from in-store bakery or local restaurants, such as fried rice from local Chinese restaurants. Multiple label values were saved when the sodium values were different for the same brand collected from different retail outlets. The nutrient values declared on labels and from laboratory analysis of samples mainly obtained from 2010–2013, represent the baseline nutrient values against which future assessments were compared to track changes.

2.3. Tracking Changes in Nutrient Values

The Scheme 1 summarizes the steps, methods, and sample sizes used for tracking changes in nutrient values.

Changes in label nutrient values: NDL tracked labels of Sentinel Foods again in 2017 (some labels were collected in late 2016), representing major national brands and selected private-label brands (generally Walmart® or Safeway® brands, if available). The brands and the type of product selected (e.g., Brand A crinkle fries for french fries, frozen) were based on the most recent consumer point-of-sale from Information Resources, Inc. (IRI) [28]. Sodium content declared on the label, and the source (directly from manufacturers or restaurant chains, their websites, or the NFP of the products) from where the information was obtained were saved in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. A post-hoc comparison of declared label sodium values against the analytical contents for the baseline samples, showed that the majority of the values were in agreement, supporting the use of labels as a tracking mechanism [29]. For this report, we compared the label serving weight and sodium values per serving for 108 Sentinel Foods, represented by 1–5 labels common to both the baseline and 2017-label dataset (239 products). Twenty-eight labels did not have the serving weight information listed, mainly restaurant foods; hence, we assumed the serving weight to be the same as at baseline. If there were changes in the serving size on the 2017-label, we used the 2017 serving weight to calculate sodium per 100 g (sodium per 100 g = (sodium per serving × 100)/serving weight). We determined changes in declared sodium values for each product label using the equation—change in label sodium (%) = (2017 label sodium − baseline label sodium)/(baseline label sodium) × 100, and grouped percent changes by brand into five categories—reductions in sodium values (<−20%; ≥−20% and ≤−10%), increase in sodium values (>20%; ≥10% and ≤20%), and no change (>−10% and <10%), and then determined their frequency distribution. A change of at least ±10% was considered as minimal change, as per our established criteria, based on our review of analytical variability for chemical analyses of sodium [20]. The comparisons were made for each product label, rather than Sentinel Foods, as different brands can potentially have changes in declared sodium content in different directions (i.e., reduce or increase or no change). We re-checked all changes over 20% against the label image by an alternate staff, to detect typographical errors.

Changes in laboratory nutrient contents: As per the initial monitoring plan, the 125 Sentinel Foods were to be periodically resampled and chemically analyzed every 4–8 years, and the periodicity was determined and described in detail [20]. Due to reduced funding, only a subset of 43 of the 125 foods were resampled. The initial plan was supplemented with several other data sources to identify the 43 Sentinel Foods. These data sources included—a. review of top 10 food categories for sodium intake in the U.S., to ensure adequate representation of the top categories [30]; b. dietary intake data from the latest WWEIA, NHANES, prioritizing Sentinel Foods with higher contribution to total sodium intake; c. changes in label sodium values prioritizing Sentinel Foods with changes ; d. Sentinel Foods with larger differences in label and laboratory values at baseline [29]. NDL resampled 43 Sentinel Foods staggered over years 2014–2017 (Table 1) (exception: white bread was sampled in late 2013, and packaged macaroni and cheese and ramen noodles were re-sampled in early 2018), to obtain 1181 samples, combined one or more samples into 650 composites and chemically analyzed them using similar procedures as in baseline, with one exception. Consumer point-of-sale data from Nielsen [25] used to identify brands to sample in baseline was replaced with similar data from IRI [28]. We determined the sales-weighted mean sodium content for each of the 43 resampled Sentinel Food and compared to their baseline sales-weighted mean content, and determined change using the equation: Change in laboratory sodium (%) = (resampled laboratory sodium content − baseline laboratory sodium content)/(baseline laboratory sodium content) × 100. Furthermore, for foods with at least ±10% change in laboratory sodium value, we identified changes in related nutrients (potassium, total fat, saturated fat, total calories, and total sugar per 100 g) of at least ±10%. We did not compare total fat for three foods—canned tomatoes, green beans, and tuna, as their laboratory total fat contents for both baseline and resampled foods were less than 1 g/100 g, and our review of results for reference quality control material have shown high analytical variability for such foods. The resampled laboratory data were used for further evaluations, detailed below, as they provide insights especially on the variability of the foods and help validate the changes in labels.

Table 1.

An alphabetical listing of the 43 Sentinel Foods a resampled in 2014–2017, sorted by food category b.

| Food Category | Sentinel Food Description |

|---|---|

| Breads, Rolls, Tortillas | |

| Flour tortilla | |

| Hamburger roll | |

| Taco shell, corn | |

| Wheat bread | |

| White bread | |

| Breakfast Cereals | |

| Cheerios | |

| Cheese | |

| American cheese | |

| Condiments and Sauces | |

| Barbecue sauce | |

| Catsup | |

| Dill pickles | |

| Salsa | |

| Cured Meats/Poultry | |

| Beef hot dog | |

| Ham, packaged and deli | |

| Pork bacon | |

| Pork sausage | |

| Salami | |

| Turkey, packaged and deli | |

| Grain Based Mixed Dishes | |

| Macaroni and cheese, prepared from packaged | |

| Ravioli, meat-filled, canned | |

| Meat and Poultry Mixed Dishes | |

| Chili with meat and beans, canned | |

| Mexican Mixed Dishes | |

| Beef soft taco, fast food | |

| Pizza | |

| Cheese pizza, thin crust, frozen | |

| Pepperoni pizza, regular crust, fast food or restaurant | |

| Plant-Based Protein Foods | |

| Refried beans, canned | |

| Potato Products | |

| French fries, fast food or restaurant | |

| French fries, frozen | |

| Potato salad, ready-to-eat | |

| Poultry Products | |

| Chicken nuggets, fast food or restaurant | |

| Chicken nuggets, frozen | |

| Quick Bread Products | |

| Biscuit, refrigerated dough | |

| Salad dressings and mayonnaise | |

| Italian dressing | |

| Ranch dressing | |

| Sandwiches | |

| Breaded chicken sandwich, fast food | |

| Corn dog, frozen | |

| Double cheeseburger, fast food | |

| Savory Snacks and Crackers | |

| Cheese curls | |

| Hard pretzels | |

| Microwave popcorn, butter flavor | |

| Tortilla chips, unflavored | |

| Seafood Products | |

| Canned tuna, in water | |

| Soups | |

| Ramen noodle soup, prepared from packaged | |

| Vegetable Products | |

| Green beans, canned | |

| Tomatoes, canned |

a Sentinel Foods are 125 popular, sodium-contributing, commercially processed and restaurant foods in the U.S. that have sodium added during processing or preparation. These foods will serve as indicators to assess changes over time. b Adapted from What We Eat In America Food Categories [22].

2.4. Comparison of Changes in Labels and Laboratory Sodium at Brand Level

NDL identified changes in label sodium values from baseline to 2017 for the 43 resampled foods by brand. For one food (Brand A for canned ravioli), there were two 2017-labels with different declared sodium labels, so we used the mean sodium per 100 g as the 2017-label sodium for the brand. For seven sentinel foods (11 brands), we used 2015 label data, as these foods were chemically analyzed in 2015. Furthermore, we determined mean changes in laboratory sodium content by brand, and the changes in laboratory sodium of the Sentinel Foods by brand (%) using the equation: (resampled laboratory sodium content of brand − baseline laboratory sodium content of brand)/(baseline laboratory sodium content) × 100. We compared the changes in labels against changes in laboratory sodium by brand on per 100 g basis for 70 common brands. Private-labels and few top brands that changed due to changes in market share were not included in these comparisons. We grouped the results as follows—1. No change in label or laboratory sodium content, 2. changes in label sodium but not laboratory sodium, 3. changes in laboratory sodium but not label sodium, 4. changes in both label and laboratory sodium content in the same direction, and 5. changes in label and laboratory sodium content in the opposite directions.

2.5. Comparison to FDA’s Draft Voluntary Sodium-Reduction Targets

NDL assigned FDA’s draft food categories to the 43 Sentinel Foods, based on description and source (packaged or restaurant) (Supplemental Table S3). For most foods, the assignment was direct, such as the Sentinel Food, ‘Italian Dressing’ was assigned to the FDA category ‘Salad dressing’. For few foods, substitutions were used. For example, Sentinel Food, ‘French fries, frozen’ was assigned to the FDA category, ‘Fried Potatoes without Toppings’, restaurant as sodium targets were not available for packaged frozen french fries. FDA draft categories are broader and represent many foods other than the linked Sentinel Food and FDA used food labels for packaged foods and menu data for restaurants mainly from 2010, adjusted by market share of the sales volume to determine the baseline sodium concentrations [18]. Each of the categories have target sodium concentrations indicating FDA’s sales-weighted goals for the food category, short (2-year) and long-term (10-year). We compared estimated sales-weighted laboratory sodium content (mg per 100 g) of resampled Sentinel Foods to FDA’s short-term and long-term target sodium contents by calculating percent differences and identified foods with percent difference ≥ 10%, i.e., higher than 10% of the FDA’s target sodium content. Percent difference = (sales-weighted laboratory sodium content − FDA target)/FDA target) × 100. To provide better understanding of the results, we also compared baseline sodium content of Sentinel Foods to FDA’s baseline and targets.

2.6. Comparison to FDA Sodium Limits for ‘Healthy’ Foods

NDL compared amounts of sodium per serving to the FDA limits for sodium for the nutrient content claim ‘healthy’, using the same methods as used for baseline (based on type of food and RACC (Reference Amounts Customarily Consumed) or serving size [19]). We used the baseline categorization of the Sentinel Foods as ‘individual’ or ‘meal-type/main dishes’ and serving size/RACC information, and compared the sodium contents to the FDA criteria 21 CFR §101.65(d) (2) (480 mg per serving or per RACC for individual foods with RACC > 30 g; 480 mg/50 g for individual foods with RACC ≤ 30 g; 600 mg/serving for meal-type/main dishes) [31]. FDA has several other criteria for the nutrient content claim ‘healthy’; however, comparisons were only made for the sodium criteria.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

For foods with at least ±10% change in laboratory sodium content, NDL tested for significance of difference (alpha = 0.05) using the R (version 3.4.1) [32] package EMMeans [33], after rank transforming nutrient data, fitting a ranked regression model with the ranked nutrient content as the dependent variable and the type (baseline or re-sampled) as the independent variable, and weighting by market share. Statistical tests were not done when data were skewed or multi-modal, extremely heteroscedastic, sample sizes (n) were insufficient (n < 6), or when the differences were lower than 10%. The p-values for each food, across all nutrients were then adjusted for multiple comparisons using the ‘holm’ correction procedure. We also determined measures of variability (standard deviation (SD), coefficient of variability (CV) (=SD/mean), and range for each Sentinel Food) for sodium and related nutrients. All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 3.4.1).

3. Results

3.1. Tracking Changes in Label Sodium Values

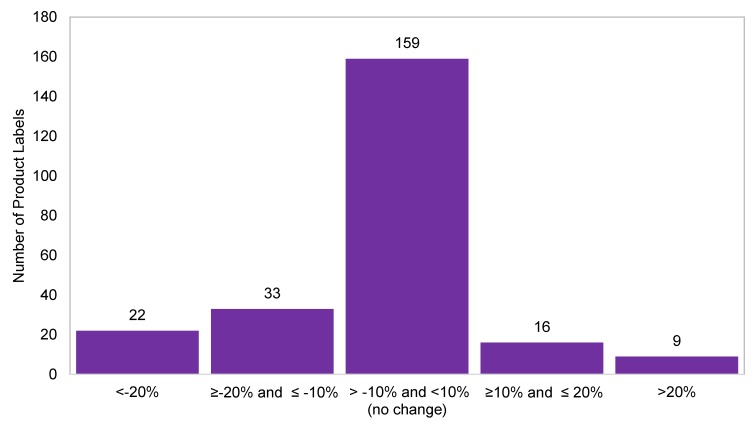

Figure 1 presents a histogram of distribution of changes (%) in the declared label sodium values of 239 products (representing 108 Sentinel Foods) from baseline to 2017. The majority (66%) of the label sodium values did not change as per our criteria (at least ±10%). Changes were observed for about one-third of the labels (80 of 239 labels). There were more than twice as many reductions (n = 55 labels) as increases in declared sodium values (n = 25 labels).

Figure 1.

Distribution of changes (%). a in the label sodium values of 239 products representing 108 Sentinel Foods b, from baseline to 2017. a Change in label sodium (%) = (2017 label sodium—baseline label sodium)/(baseline label sodium) × 100. Baseline labels were collected in 2010–2013. b Sentinel Foods: Popular, sodium-contributing, commercially processed and restaurant foods in the U.S. that are being tracked as part of the USDA-CDC sodium monitoring program [20].

Change in label sodium

Table 2 lists changes of at least ±10% in the label sodium values, between baseline and 2017, specific to brands, sorted by food category. Large changes (<−20% or >20%) in sodium content were observed for 31 of the 80 changes in labels, many of which were among top sodium contributors [30] including specific brands of American cheese, flour tortillas, pork sausage, fast food pepperoni and cheese pizza, and breaded chicken sandwich (reductions), whereas label sodium content increased for specific brands of American cheese, flour tortilla, white bread and hamburger rolls, bologna, meat and poultry frankfurters, among others. In terms of Sentinel Foods (not product labels, as in Figure 1), about half of the Sentinel Foods (n = 49 of 108) had no changes in label sodium levels for all brands examined. Sodium levels reduced for 39 foods and increased for 14 foods, consistently in the same direction for different brands of the same food. However, for six Sentinel foods-flour tortilla, fast food cheese pizza, fast food macaroni and cheese, frozen lasagna, American cheese and frozen corn dogs, some brands increased, whereas others decreased. Among the food categories represented by the 108 Sentinel Foods, there were no changes in label sodium levels since baseline among the category salad dressings and mayonnaise. Overall, changes in the sodium content of foods within categories were mixed, e.g., some foods in the cheese category decreased in sodium concentrations whereas others increased. The patterns of no change, reductions, and increases were similar irrespective of where the food was obtained from, i.e., store or restaurant. Of the 48 restaurant food labels tracked, 30 had no changes, 12 decreased, and six increased in sodium content. Similarly, for 191 packaged food labels tracked, 132 had no changes, 41 decreased, and 18 increased in sodium content. NDL tracked 37 labels for private-label products: 18 had no changes, 14 decreased, and five increased in sodium content.

Table 2.

Changes of at least ±10% in the label sodium values of Sentinel Foods a, specific to brands, sorted by food category b from baseline (2010–2013) to 2017.

| Food Item | Baseline | 2017-Label | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serving Weight (g) | Sodium Value (mg/Serving) | Sodium Value (mg/100 g) | Serving Weight (g) | Sodium Value (mg/Serving) | Sodium Value (mg/100 g) | Change from Baseline (%) c | |

| Asian Mixed Dishes | |||||||

| Vegetable egg roll (Brand A) d | 85 | 420 | 494 | 71 | 390 | 549 | 11 |

| Vegetable egg roll (Brand B) | 87 | 410 | 471 | 87 | 460 | 529 | 12 |

| Vegetable egg roll (Brand C) | 89 | 410 | 461 | 86 | 460 | 535 | 16 |

| Breads, Rolls, Tortillas | |||||||

| Flour tortilla (Brand A) | 120 | 300 | 250 | 43 | 160 | 372 | 49 |

| Flour tortilla (Brand B) | 49 | 440 | 898 | 45 | 320 | 711 | −21 |

| Hamburger roll e | 39 | 150 | 385 | 43 | 230 | 535 | 39 |

| Hamburger roll e | 39 | 150 | 385 | 43 | 230 | 535 | 39 |

| White bread | 28 | 130 | 464 | 26 | 140 | 538 | 16 |

| Breakfast Cereals | |||||||

| Cheerios | 28 | 160 | 571 | 28 | 140 | 500 | −13 |

| Frosted flakes | 30 | 140 | 467 | 29 | 150 | 517 | 11 |

| Cheese | |||||||

| American cheese (Brand A) | 19 | 250 | 1316 | 21 | 220 | 1048 | −20 |

| American cheese (Brand B) | 21 | 270 | 1286 | 19 | 340 | 1789 | 39 |

| Fried mozzarella sticks, fast food or restaurant | 2640 | 2140 | −19 * | ||||

| Mozzarella cheese, part-skim | 28 | 200 | 714 | 28 | 180 | 643 | −10 |

| Parmesan cheese, grated | 5 | 85 | 1700 | 5 | 75 | 1500 | −12 |

| Condiments and Sauces | |||||||

| Barbecue sauce (Brand A) | 36 | 370 | 1028 | 36 | 280 | 778 | −24 |

| Barbecue sauce (Brand B) | 36 | 450 | 1250 | 36 | 350 | 972 | −22 |

| Nacho cheese dip | 34 | 280 | 824 | 30 | 340 | 1116 | 36 |

| Cured Meats/Poultry | |||||||

| Beef hot dog (Brand A) | 57 | 550 | 965 | 57 | 480 | 842 | −13 |

| Beef hot dog (Brand B) | 45 | 470 | 1044 | 42 | 360 | 857 | −18 |

| Bologna | 28 | 280 | 1000 | 32 | 390 | 1219 | 22 |

| Ham, packaged and deli | 28 | 310 | 1107 | 56 | 500 | 893 | −19 |

| Meat and poultry hot dog | 45 | 350 | 778 | 45 | 420 | 933 | 20 |

| Pork sausage | 68 | 710 | 1044 | 68 | 510 | 750 | −28 |

| Turkey, packaged and deli | 51 | 460 | 902 | 28 | 210 | 750 | −17 |

| Grain Based Mixed Dishes | |||||||

| Lasagna with meat, fast food or restaurant | 421 | 2830 | 672 | 2070 | −27 * | ||

| Lasagna with meat, frozen (Brand A) | 227 | 860 | 379 | 227 | 980 | 432 | 14 |

| Lasagna with meat, frozen (Brand B) e | 215 | 670 | 312 | 297 | 820 | 276 | −11 |

| Lasagna with meat, frozen (Brand B) e | 215 | 860 | 400 | 297 | 820 | 276 | −31 |

| Macaroni and cheese, fast food or restaurant (Brand A) | 180 | 570 | 317 | 650 | 14 * | ||

| Macaroni and cheese, fast food or restaurant (Brand B) | 236 | 1530 | 648 | 1220 | −20 * | ||

| Ravioli, meat-filled, canned (Brand A) e | 252 | 700 | 278 | 425 | 750 | 176 | −36 |

| Ravioli, meat-filled, canned (Brand A) e | 252 | 950 | 377 | 425 | 750 | 176 | −53 |

| Ravioli, meat-filled, canned (Brand B) | 254 | 1050 | 413 | 254 | 750 | 295 | −29 |

| Spaghetti with meatballs, canned | 250 | 1050 | 420 | 255 | 750 | 294 | −30 |

| Meat and Poultry Mixed Dishes | |||||||

| Chicken pot pie, frozen | 234 | 800 | 342 | 200 | 750 | 375 | 10 |

| Chicken pot pie, frozen (Brand A) | 198 | 790 | 399 | 198 | 930 | 470 | 18 |

| Chicken pot pie, frozen (Brand A) | 283 | 1000 | 353 | 198 | 930 | 470 | 33 |

| Chili with meat and beans, canned | 247 | 1200 | 486 | 247 | 990 | 401 | −18 |

| Chili with meat and beans, fast food or restaurant | 1010 | 1130 | 12 * | ||||

| Mexican Mixed Dishes | |||||||

| Bean burrito, fast food | 198 | 960 | 485 | 1060 | 10 * | ||

| Pizza | |||||||

| Cheese pizza, thick crust, fast food or restaurant | 125 | 750 | 600 | 125 | 640 | 512 | −15 |

| Cheese pizza, thin crust, fast food or restaurant (Brand A) | 76 | 350 | 461 | 88 | 460 | 523 | 14 |

| Cheese pizza, thin crust, fast food or restaurant (Brand B) | 89 | 800 | 899 | 89 | 610 | 685 | −24 |

| Cheese pizza, thin crust, frozen | 146 | 890 | 610 | 149 | 750 | 503 | −17 |

| Pepperoni pizza, regular crust, fast food or restaurant | 108 | 740 | 685 | 590 | −20 * | ||

| Pepperoni pizza, thick crust, fast food or restaurant | 123 | 910 | 740 | 700 | −23 * | ||

| Plant-Based Protein Foods | |||||||

| Peanuts, dry roasted, salted | 28 | 170 | 607 | 28 | 150 | 536 | −12 |

| Refried beans, canned | 120 | 570 | 475 | 120 | 440 | 367 | −23 |

| Potato Products | |||||||

| French fries, fast food or restaurant | 117 | 270 | 231 | 111 | 230 | 207 | −10 |

| French fries, frozen (Brand A) | 84 | 360 | 429 | 84 | 290 | 345 | −19 |

| French fries, frozen (Brand B) | 84 | 410 | 488 | 84 | 270 | 321 | −34 |

| Hash browns, fast food | 168 | 810 | 482 | 169 | 1140 | 675 | 40 |

| Tater tots, frozen | 84 | 400 | 476 | 84 | 330 | 393 | −18 |

| Poultry Products | |||||||

| Chicken nuggets, fast food or restaurant | 60 | 350 | 583 | 60 | 390 | 650 | 11 |

| Chicken nuggets, frozen | 85 | 540 | 635 | 85 | 360 | 424 | −33 |

| Chicken tenders, fast food or restaurant | 201 | 1320 | 657 | 940 | −29 * | ||

| Chicken tenders, frozen | 85 | 460 | 541 | 84 | 600 | 714 | 32 |

| Quick Bread Products | |||||||

| Biscuit, refrigerated dough | 58 | 560 | 966 | 58 | 470 | 810 | −16 |

| Blueberry muffin | 50 | 150 | 300 | 47 | 190 | 404 | 35 |

| Sandwiches | |||||||

| Breaded chicken sandwich, fast food | 143 | 800 | 559 | 144 | 600 | 417 | −26 |

| Corn dog, frozen (Brand A) | 75 | 540 | 720 | 75 | 470 | 627 | −13 |

| Corn dog, frozen (Brand B) | 76 | 460 | 605 | 113 | 800 | 708 | 17 |

| Hamburger, fast food | 100 | 460 | 460 | 93 | 380 | 409 | −11 |

| Savory Snacks and Crackers | |||||||

| Cheese curls (Brand A) | 28 | 290 | 1036 | 28 | 250 | 893 | −14 |

| Cheese curls (Brand B) | 28 | 350 | 1250 | 28 | 300 | 1071 | −14 |

| Cracker, saltine | 16 | 150 | 938 | 16 | 135 | 844 | −10 |

| Microwave popcorn, butter flavor (Brand A) | 33 | 390 | 1182 | 34 | 300 | 882 | −25 |

| Microwave popcorn, butter flavor (Brand B) | 30 | 350 | 1167 | 32 | 300 | 938 | −20 |

| Potato chips, flavored | 28 | 230 | 821 | 28 | 200 | 714 | −13 |

| Tortilla chips, flavored | 28 | 250 | 893 | 28 | 210 | 750 | −16 |

| Seafood Products | |||||||

| Canned tuna, in water | 56 | 215 | 384 | 56 | 180 | 321 | −16 |

| Fish sticks, frozen | 86 | 480 | 558 | 95 | 420 | 442 | −21 |

| Fried shrimp, fast food or restaurant | 1270 | 590 | −54 * | ||||

| Soups | |||||||

| Chicken broth, canned, ready to serve | 245 | 970 | 396 | 245 | 860 | 351 | −11 |

| Sweet Bakery Products | |||||||

| Chocolate sandwich cookie | 34 | 160 | 471 | 34 | 130 | 382 | −19 |

| Vegetable Products | |||||||

| Green beans, canned (Brand A) | 116 | 400 | 345 | 121 | 320 | 264 | −23 |

| Green beans, canned (Brand B) | 116 | 330 | 284 | 120 | 290 | 242 | −15 |

| Tomatoes, canned (Brand A) | 121 | 220 | 182 | 121 | 170 | 140 | −23 |

| Tomatoes, canned (Brand B) | 121 | 220 | 182 | 121 | 180 | 149 | −18 |

a Sentinel Foods are 125 popular, sodium-contributing, commercially processed and restaurant foods in the U.S. that have sodium added during processing or preparation. These foods will serve as indicators to assess changes over time. b Adapted from What We Eat In America Food Categories. c Change in label sodium (%) = (2017 label sodium—baseline label sodium)/(baseline label sodium) × 100; per 100 g or per serving (flagged with *). d Brand A, B etc. was added after description of the food item, if there was more than one brand with change of at least ±10%. e Two different labels from the same brand, with same sodium declaration, but different related nutrient value. * The comparison was based on per serving.

3.2. Tracking Changes in Laboratory Nutrient Values

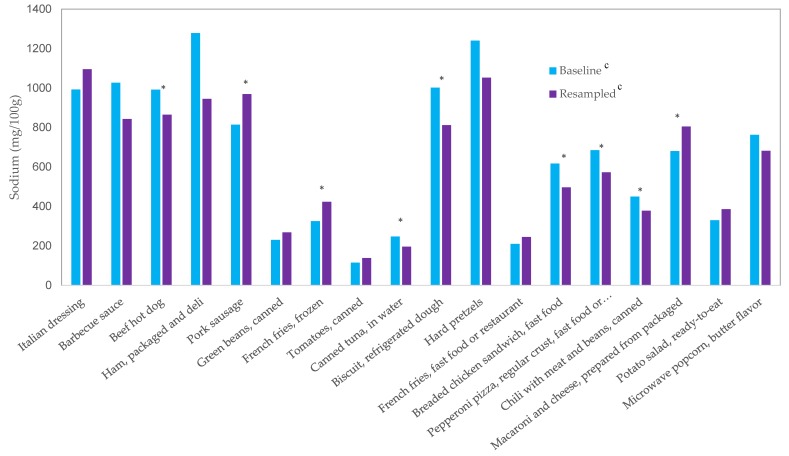

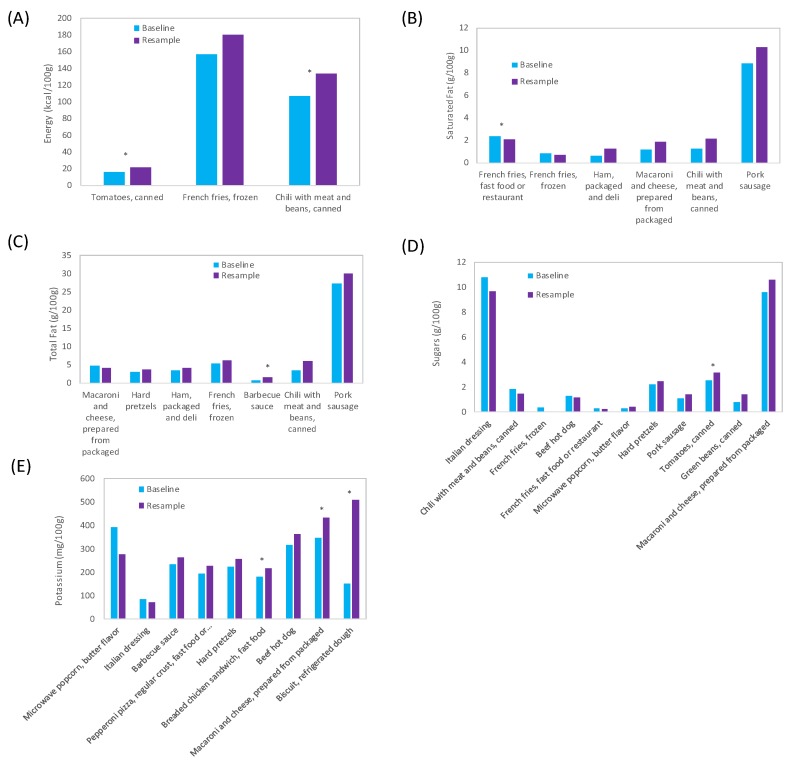

Table 3 lists baseline and resampled sales-weighted mean and variability measures for laboratory sodium content (mg per 100 g) and percent change in the sodium content. Our results show that for 25 of 43 Sentinel Foods resampled, sodium content did not change as per our criteria of at least ±10%. We observed changes for 18 of the 43 foods; for 10 of the 18 foods with changes, the sodium content reduced, whereas for the other eight foods the sodium content increased. These changes could have been due to market share changes or reformulation of products to reduce sodium. The changes were statistically significant for eight of the 43 foods (p < 0.05). The sodium concentration was 10% to 26% lower for beef hot dogs, canned tuna, refrigerated biscuit dough, fast food pepperoni pizza and canned chili with meat and beans, whereas the sodium concentration was 10% to 30% higher among pork sausage, frozen french fries, and packaged macaroni and cheese. Figure 2 presents the changes in sales-weighted mean baseline and resampled sodium content for these 18 foods sorted by relative change in sodium content. In terms of biggest absolute changes in mean sodium content, sliced ham decreased by 334 mg (26% decrease) from 1279 to 945 mg/100 g, and pork sausage increased by 155 mg (19% increase) from 814 to 969 mg/100 g. Figure 3 shows changes in related nutrient contents for 16 foods that had changes of at least ±10% for sales-weighted sodium and one or more related nutrient estimates. Of these 16 foods, there were significant changes (p < 0.05) for seven foods, as follows: increases in energy (two foods), total fat (one food), total sugar (one food), and potassium (three foods), and decrease in saturated fat for one food.

Table 3.

Laboratory sodium content of resampled a Sentinel Foods b (sales-weighted), compared to baseline c sodium content (sales-weighted), FDA’s short- and long-term sodium targets, and FDA’s sodium limit for ‘healthy’ foods d, sorted by food category e.

| Food Item | Baseline Sales-Weighted Sodium Mean (SD) f | Resampled Sales-Weighted Sodium (mg per 100 g) | Change from Baseline (%) | FDA Targets (mg per 100 g) | Difference (%) between Resampled Laboratory Sodium and FDA Target h | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | Range | CV (%) g | Short-Term | Long-Term | Short-Term | Long-Term | |||

| Breads, Rolls, Tortillas | ||||||||||

| Wheat bread | 508(48) | 10 | 472(68) | 375–573 | 15 | −7 | 420 | 300 | 13 | 58 |

| Hamburger roll | 499(34) | 5 | 493(39) | 433–548 | 8 | −1 | 440 | 300 | 12 | 65 |

| White bread | 490(40) | 6 | 490(34) | 417–526 | 7 | 0 | 440 | 300 | 11 | 63 |

| Flour tortilla | 708(73) | 16 | 712(105) | 531–873 | 15 | 1 | 580 | 410 | 23 | 74 |

| Taco shell, corn | 323(168) | 17 | 341(181) | 3−593 | 53 | 5 | 490 | 320 | −30 | 7 |

| Breakfast Cereals | ||||||||||

| Cheerios | 496(0) | 6 | 488(11) | 468–507 | 2 | −2 | 470 | 310 | 4 | 57 |

| Cheese | ||||||||||

| American cheese i | 1308(66) | 16 | 1279(142) | 1120–1540 | 11 | −2 | 1210 | 1000 | 6 | 28 |

| Condiments and Sauces | ||||||||||

| Barbecue sauce | 1026(292) | 28 | 843(166) | 623–1530 | 20 | −18 | 900 | 760 | −6 | 11 |

| Salsa | 710(37) | 12 | 657(20) | 626–692 | 3 | −7 | 500 | 350 | 32 | 88 |

| Catsup | 906(37) | 18 | 897(28) | 860–981 | 3 | −1 | 900 | 760 | 0 | 18 |

| Dill pickles | 809(218) | 18 | 850(168) | 643–1220 | 20 | 5 | 500 | 410 | 70 | 108 |

| Cured Meats/Poultry | ||||||||||

| Ham, packaged and deli | 1278(240) | 18 | 945(174) | 647–1320 | 18 | −26 | 1020 | 810 | −7 | 17 |

| Beef hot dog | 992(109) | 17 | 864(82) | 732–1040 | 9 | −13 * | 900 | 730 | −4 | 18 |

| Pork bacon i | 1684(139) | 18 | 1554(186) | 1240–2110 | 12 | −8 | 1700 | 1200 | −8 | 30 |

| Salami i | 1756(206) | 13 | 1712(182) | 1320–1950 | 11 | −3 | 1630 | 1300 | 5 | 32 |

| Turkey, packaged and deli i | 922(142) | 18 | 897(154) | 603–1150 | 17 | −3 | 900 | 780 | 0 | 15 |

| Pork sausage i | 813(103) | 13 | 969(73) | 697–1030 | 8 | 19 * | 850 | 750 | 14 | 29 |

| Grain Based Mixed Dishes | ||||||||||

| Ravioli, meat-filled, canned i,j | 282(48) | 6 | 269(13) | 249–293 | 5 | −5 | 330 | 220 | −18 | 23 |

| Macaroni and cheese, prepared from packaged i,j,k | 680(54) | 24 | 804(74) | 603–943 | 9 | 18 * | 750 | 490 | 7 | 64 |

| Meat and Poultry Mixed Dishes | ||||||||||

| Chili with meat and beans, canned i,j | 449(20) | 12 | 377(9) | 354–388 | 3 | −16 * | 330 | 220 | 15 | 72 |

| Mexican Mixed Dishes | ||||||||||

| Beef soft taco, fast food i | 559(25) | 6 | 552(18) | 530–587 | 3 | −1 | 390 | 220 | 42 | 151 |

| Pizza | ||||||||||

| Pepperoni pizza, regular crust, fast food or restaurant i,j | 684(75) | 12 | 572(34) | 503–610 | 6 | −16 * | 460 | 310 | 25 | 85 |

| Cheese pizza, thin crust, frozen i | 471(14) | 12 | 489(35) | 428–535 | 7 | 4 | 420 | 260 | 16 | 88 |

| Plant-Based Protein Foods | ||||||||||

| Refried beans, canned i | 370(43) | 18 | 373(28) | 298–411 | 8 | 1 | 290 | 250 | 29 | 49 |

| Potato Products | ||||||||||

| French fries, fast food or restaurant | 209(55) | 18 | 243(72) | 137–402 | 30 | 16 | 310 | 190 | −21 | 28 |

| Potato salad, ready-to-eat i | 329(72) | 5 | 385(41) | 338–460 | 11 | 17 | 300 | 140 | 29 | 176 |

| French fries, frozen | 324(48) | 11 | 422(120) | 179–586 | 28 | 30 * | 310 | 190 | 36 | 123 |

| Poultry Products | ||||||||||

| Chicken nuggets, frozen i | 560(50) | 15 | 529(47) | 449–679 | 9 | −5 | 570 | 420 | −7 | 26 |

| Chicken nuggets, fast food or restaurant i | 594(80) | 12 | 602(47) | 544–714 | 8 | 1 | 570 | 420 | 6 | 44 |

| Quick Bread Products | ||||||||||

| Biscuit, refrigerated dough | 1002(101) | 12 | 811(37) | 774–962 | 5 | −19 * | 820 | 500 | −1 | 62 |

| Salad dressings and mayonnaise | ||||||||||

| Ranch dressing | 901(60) | 18 | 851(39) | 705–890 | 5 | −6 | 880 | 590 | −3 | 44 |

| Italian dressing i | 992(42) | 18 | 1095(275) | 926–1630 | 25 | 10 | 880 | 590 | 25 | 86 |

| Sandwiches | ||||||||||

| Breaded chicken sandwich, fast food i | 616(32) | 18 | 496(88) | 400–721 | 18 | −20 | 470 | 310 | 6 | 60 |

| Corn dog, frozeni | 668(87) | 10 | 686(155) | 479–853 | 23 | 3 | 610 | 400 | 13 | 72 |

| Double cheeseburger, fast food i | 617(86) | 18 | 566(74) | 417–645 | 13 | −8 | 480 | 300 | 18 | 89 |

| Savory Snacks and Crackers | ||||||||||

| Hard pretzels i | 1240(272) | 17 | 1052(152) | 811–1380 | 14 | −15 | 1020 | 750 | 3 | 40 |

| Microwave popcorn, butter flavor | 762(163) | 18 | 681(96) | 516–851 | 14 | −11 | 680 | 400 | 0 | 70 |

| Cheese curls | 942(120) | 12 | 927(100) | 775–1070 | 11 | −2 | 870 | 550 | 7 | 69 |

| Tortilla chips, unflavored | 327(46) | 16 | 346(62) | 140–434 | 18 | 6 | 390 | 300 | −11 | 15 |

| Seafood Products | ||||||||||

| Canned tuna, in water | 246(58) | 18 | 194(35) | 112–242 | 18 | −21 * | 360 | 260 | −46 | −25 |

| Soups | ||||||||||

| Ramen noodle soup, prepared from packaged i,j,k | 1855(132) | 44 | 1874(124) | 1560–2130 | 7 | 1 | 1640 | 1290 | 14 | 45 |

| Vegetable Products | ||||||||||

| Green beans, canned | 229(24) | 12 | 268(46) | 183–328 | 17 | 17 | 290 | 250 | −8 | 7 |

| Tomatoes, canned | 115(37) | 18 | 138(29) | 56–184 | 21 | 20 | 290 | 250 | −52 | −45 |

a Resampled: Resampled in 2014–2017. b Sentinel Foods are 125 popular, sodium-contributing, commercially processed and restaurant foods in the U.S. that have sodium added during processing or preparation. These foods will serve as indicators to assess changes over time. c Baseline: Sampled in 2010–2013. d FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA’s short- and long-term sodium targets: See Reference [18]. FDA’s sodium limit for ‘healthy’ foods: Title 21: Food and Drugs §101.65 Implied nutrient content claims and related label statements. See Reference [34]. e Adapted from What We Eat In America Food Categories [22]. f SD: standard deviation. g CV: coefficient of variation. h Percent difference = (sales-weighted laboratory sodium content-FDA target)/FDA target × 100. i Exceeds FDA limit for sodium for ‘healthy’ foods (480 mg/serving and /RACC for individual foods with Reference Amounts Commonly Consumed (RACC) >30 g; 480 mg/50 g for individual foods with RACC ≤ 30 g; 600 mg for meal-type/main dishes) [34]. j Assigned as a main dish for FDA sodium limit for ‘healthy’ foods comparison. k Dried or condensed forms were sampled and analyzed. The nutrient values are for the samples analyzed. However, sodium content of prepared form was used for comparison to FDA sodium limit for ‘healthy’ foods. * p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Sentinel Foods with changes a of at least ±10% in the sales-weighted mean laboratory sodium content (18 of the 43 resampled Sentinel Foods) b, sorted by change in sodium content (mg per 100 g) *: p < 0.05. a Change in laboratory sodium (%) = (resampled c laboratory sodium content − baseline c laboratory sodium content)/(baseline laboratory sodium content) × 100. b Sentinel Foods: Popular, sodium-contributing, commercially processed and restaurant foods in the U.S. that are being tracked as part of the USDA’s sodium monitoring program[20]. c Baseline Sentinel Foods were sampled in 2010–2013, and then resampled in 2014–2017. * p < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Resampled Sentinel Foods with changes of at least ±10% in sales-weighted sodium and related nutrients: (A) energy, (B) saturated fat, (C) total fat (excludes foods < 1 g per 100 g), (D) sugar, and (E) Potassium since baseline. Baseline Sentinel Foods were sampled in 2010–2013, and then resampled in 2014–2017. *: p < 0.05.

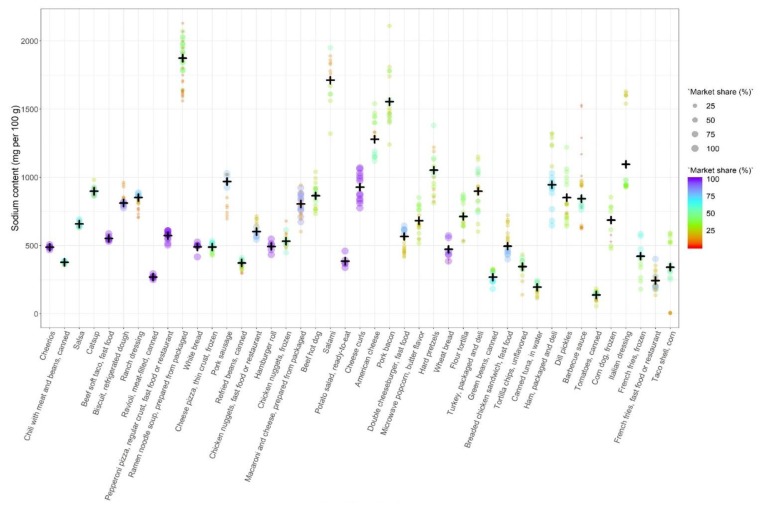

Figure 4 shows the results from laboratory analyses of sodium (mg/100 g) for individual composite samples (n = 650) for the 43 resampled foods. Taco shells, fast food and frozen french fries, Italian dressing, corn dogs, and canned tomatoes had the highest CVs. Cheerios, canned chili, salsa, catsup, and fast food soft beef tacos had the lowest CVs. Of these, for Cheerios and beef tacos only one prominent brand was sampled, whereas several brands were sampled for other foods. The range for sodium per 100 g was widest for barbecue sauce (623 to 1530 mg), pork bacon (1240 to 2110 mg), and Italian dressing (926 to 1630 mg) (all over 700 mg) among the 43 resampled foods.

Figure 4.

Variability of sodium per 100 g of the resampled Sentinel Foods (sampled in 2014–2017; n = 43 Sentinel Foods; 650 sample composites analyzed), sorted by variability (% CV). The size of the points is proportional to their market share. Color for the ease of the readers. The plus symbol indicates the sales-weighted mean sodium content (mg/100 g) for the food.

Table 3 also compares the sales-weighted laboratory sodium content (mg per 100 g) of 43 resampled Sentinel Foods to FDA’s short-term and long-term target sodium concentrations for the category. Eighteen of the 43 resampled foods have a sodium content 10% or higher than the FDA short-term targets for their assigned category, nine of the 18 foods have mean sodium content ≥20% than the short-term target. The latter includes dill pickles, fast food soft beef tacos and pepperoni pizza, flour tortillas, frozen French fries, Italian dressing, potato salad, refried beans, and salsa. Twenty-five of the 43 resampled foods had sodium content either lower or within 10% of the FDA short-term target for the assigned category. Eighteen of these 25 foods had sodium content either lower or within 10% of the short-term FDA target at baseline too. The additional seven foods that meet the short-term targets on resampling are barbecue sauce, beef frankfurters, fast food chicken sandwich, microwave popcorn, packaged ham, pretzels, and refrigerated biscuits. However, four foods that had met the short-term FDA targets at baseline had increases in their sales-weighted sodium content, and do not meet the targets anymore. These include—corn dog, pork sausage, frozen french fries, and potato salad. Only four Sentinel Foods are either lower or 10% or less of the long-term FDA targets—canned green beans, tomatoes and tuna and taco shells.

Table 3 also compares the sales-weighted laboratory sodium content (mg per 100 g) of 43 resampled Sentinel Foods to FDA’s current sodium limits for the claim ‘healthy’. About half (21 of 43) of the Sentinel Foods, exceeded the FDA sodium limit for ‘healthy’, similar to baseline results. There were some shifts in the foods as compared to the baseline. There were increases in the mean sodium content per RACC for resampled pork sausage and potato salad exceeding the ‘healthy’ limit, whereas there were reductions in sodium content below the ‘healthy’ limit for refrigerated biscuit dough, barbecue sauce, beef frankfurters, and packaged ham. FDA guidelines require the food to meet several other criteria such as for fat and saturated fat content; however, we only compared to the sodium criteria. Hence, many of these foods may still not meet the FDA overall criteria for ‘healthy’.

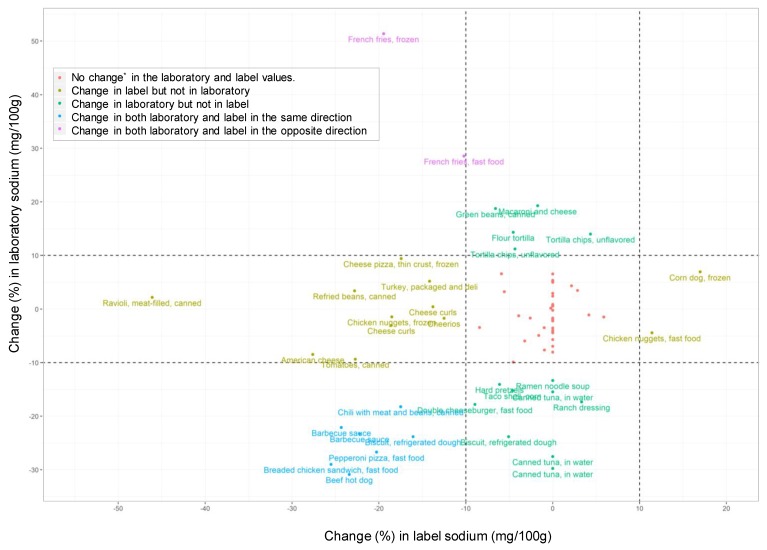

Figure 5 shows comparison of changes (%) in label and mean laboratory sodium by brand (mg per 100 g), for each of the 70 common brands. Our comparison shows the following-no change of at least ±10% in label or laboratory sodium content (n = 35 brands of the Sentinel Foods), changes in label sodium but not laboratory sodium (n = 12), changes in laboratory sodium but not label sodium (n = 14), changes in both label and laboratory sodium content in the same direction (n = 7), and changes in label (reduction) and laboratory sodium content (increase) in the opposite directions (n = 2).

Figure 5.

Comparison of changes (%) in the label and mean laboratory sodium (mg per 100 g) by brand (n = 70); * Change is defined as at least ±10% change in sodium content from baseline. To make the figure easy to read, product descriptions were shortened, and not added for products with no change in laboratory and label values (in red). Each observation represents a brand; hence, some descriptions may be repeated.

4. Discussion

This report provides an update of results from the USDA-CDC Sentinel Foods Surveillance Program. Our results show that the label sodium levels of the majority of Sentinel Foods had not changed since baseline. About one-third of the products reported changes, with twice as many reductions as increases. Laboratory analyses of the Sentinel Foods and comparisons to the current FDA sodium criteria for ‘healthy’ and short- and long-term targets for sodium reduction shows that only eight of the 43 foods had significant changes (p < 0.05) and sodium content continues to be high and variable across brands and foods. Reductions in sodium were generally not accompanied by a consistent pattern of increase in calories, total fat, saturated fat, and sugar, or change in potassium. A comparison of changes by brand using dual methodology—labels and laboratory analyses—showed consistency for 60% of the products, i.e., similar changes (or no changes) in laboratory and label sodium content. For the rest, there were changes in labels, but not validated by laboratory analyses, and vice versa. The data from this program complement other sodium monitoring efforts at CDC and FDA [18,35], and may help public health officials to strategize methods and efforts needed to reduce and monitor sodium trends in the food supply.

Our results from tracking of labels are comparable to others [36]. Previous studies reported reductions in some categories but not all, and more reductions than increases in sodium content. However, these studies reported reductions in a much larger proportion of foods. For example, Clapp et al. [36] reported sodium reduction in about half of the products from 2009 to 2015, Poti et al. [37] for seven of the 10 food group sources of sodium from 2000 to 2014 by at least 10%, and Jacobson et al. [38] in ~40% of the ~400 products monitored from 2005 to 2011. We saw reductions in only a quarter of the products. This may be related to the different time periods and our definition of change as at least ±10%, among other factors. Clapp et al. defined it as ±1%, and others calculated it as any change in the mean value [36]. Jacobson et al. [38]) also noted an increase of 2.6% in mean sodium and increase in over half of the 78 fast food restaurant foods tracked from 2005 to 2011. Wolfson et al. [39] reported no significant changes (p < 0.05) in sodium content of foods from fast food/restaurants on the menu both in 2012 and 2016. We did not observe different patterns between packaged foods and foods from fast food/restaurants. Tracking restaurant foods using labels can have additional challenges, as the labeling guidelines for menu labeling do not require listing gram weights of the serving size on the labels, as is the rule for packaged foods [40]. Hence, changes in sodium content per serving may not translate to changes in sodium per 100 g.

The use of laboratory data provides several insights into the food environment. We continue to see substantial variability among different brands for a given food. For example, laboratory sodium content of taco shells ranged 3–593 mg/100 g (label values ranged from 0–571 mg/100 g (0–160 mg/serving)). The impact of variability on sodium intake is exacerbated when the serving sizes are higher. For example, the laboratory sodium values for different brands of fast food breaded chicken sandwich ranged from 400–721 mg/100 g. Therefore, a person who had one serving of the sandwich could potentially have a difference of ~500 mg per day i.e., a difference of about 20% of the daily value, depending on what brand they chose. The high variability among top brands in sodium contents highlights the potential for sodium reduction, as some brands have lowered the sodium content of their products, overcoming the technical challenges, while continuing to maintain high sales volume. Furthermore, it emphasizes the continuing need for consumer education for reading labels before purchase, as different brands of a similar food can have very different sodium content.

We also observed considerable variation in laboratory sodium content even within a brand. Differences of over 400 mg/100 g in sodium content within a brand were observed for specific brands of bacon, and ramen noodle soup; and on the basis of serving size, we observed differences of about 200 mg/serving (~7% of the Daily Value) for specific brands of fast food pepperoni pizza, fast food cheeseburger, and ramen noodle soup. It highlights the need for food manufacturers and fast food restaurants to improve control of the manufacturing process to reduce variability and improve accuracy of labels, as a strategy for sodium reduction [35].

While all Sentinel Foods are important contributors to sodium intakes in the U.S., a review of the foods that contribute the most represent the top 10 food categories in the U.S. [21], and were chemically analyzed in our study, shows mixed results—reductions (e.g., packaged ham, fast food pepperoni pizza, and breaded chicken sandwich), increases (e.g., pork sausage, packaged macaroni and cheese), and no changes (e.g., American cheese, ramen noodle soup, and white bread). Use of analytical data allows us to compare the data against older analytical sodium content data collected before baseline [20]. The analytic data prior to baseline shows that for some of the foods, such as white bread for which no changes in sodium concentration were observed from 2010, manufacturers might have made changes before our baseline study. However, the sales-weighted mean sodium content for some top contributors such as American cheese and ramen noodle soup remained unchanged.

Our review of changes in related nutrients does not show a pattern where food manufacturers and restaurants may increase total sugar, total fat and saturated fat when they reformulate their products to reduce their sodium content, as was a concern [12,20]. For example, of the 10 foods that had reductions in sodium, only four of them had significant (p < 0.05) changes of at least ±10% in sales-weighted related nutrient estimates. These were all increases-energy in canned chili, total fat in barbeque sauce, and potassium in barbecue sauce, refrigerated biscuit dough, and fast food breaded chicken sandwich. Some of changes may not be nutritionally significant, for example, the changes (p < 0.05) in total fat for barbecue sauce from 0.6 to 1.5 g/100 g. Changes in potassium were observed in about half of the foods with sodium changes, mainly increases, and three of the foods with sodium reductions. Some of these changes, although not all, could be related to addition of potassium salts (a salt substitute), such as in refrigerated biscuit dough. We did not observe the synergistic reductions in sodium and calories, as reported by Clapp et al. [36].

Comparisons to FDA’s proposed short-term and long-term targets at baseline and on resampling, and to the FDA’s sodium limit for the claim ‘healthy’ mimics the general pattern observed for sodium content of Sentinel Foods, i.e. no changes in majority, however, for foods with changes, there are more reductions than increases in sodium content. More than half of the Sentinel Foods had sodium content either lower or within 10% the FDA short-term target for the assigned category on resampling, similar to baseline. FDA categories are broader and represent many foods, for example, canned tomatoes assigned to FDA category ’canned vegetables’ also include Sentinel foods refried beans, and green beans, that have very different sodium profiles. Furthermore, FDA used label data mainly from 2010 or before to determine the baseline values, whereas the Sentinel Foods were mainly sampled in 2010–2013, and FDA regulations allow for over-declaration of sodium content [41]. Our objective was to identify foods that had sodium content either lower or within 10% the FDA targets, and not the exact target sodium content. For example, American cheese with sodium content of 1279 mg/100 g is within 10% of the FDA target, though higher than the target of 1210 mg/100 g. This method of using within 10% for comparison may not be similar to FDA’s methods of comparison. Irrespective, reductions in sodium content are needed for many foods to meet the short-term targets, and for almost all foods to meet the long-term targets. Similar to baseline, about half of the foods exceeded the sodium limit for the current FDA criteria for a “healthy” label claim at resampling, demonstrating the need for sodium reduction. At both baseline [19], and at re-sampling all main dishes and most restaurant foods exceeded the FDA sodium limit for the claim ‘healthy’, though only limited numbers were analyzed at resampling (5 main dishes and 6 restaurant items).

Our use of dual methods to track changes-labels and laboratory analyses-provides perspectives not possible otherwise to the complexity of changes in the market place and the monitoring methodologies. Our comparison of changes in labels and laboratory analyses by brand (around similar time period and excluding private-label products), shows that 60% of the products either had no changes or changes in the same direction, based on both labels and laboratory analyses. For the rest, there were changes in labels, but not validated by laboratory analyses, and vice versa. For example, American cheese, brand A had a reduction in label sodium of 28%, but no changes in laboratory sodium values, whereas macaroni and cheese, brand A had no changes in the label sodium values, but the laboratory sodium content increased by 19%. Many foods, including canned tuna and ranch dressing (brand A) had no change in label values, but had a decrease in laboratory sodium, indicating possible stealth reduction in the product [41,42]. Only two products: fast food French fries, brand A and frozen French fries had label reductions but increases in laboratory sodium. A post-hoc analysis of the differences in baseline label and laboratory values for the Sentinel Foods showed majority of the label and laboratory sodium values were in agreement; about 19% of the label and laboratory values had differences of at least ±20% [31]. Overall, labels can provide a valid method for tracking sodium content, especially as nationwide sampling and chemical analysis is expensive and the U.S. food supply is constantly changing. Laboratory analyses are useful to validate changes in labels. Comparison of changes at the Sentinel Food level are more difficult to categorize and compare. It shows inconsistent reformulations across brands (in different directions or varying in level of change) and changes in market shares of the top brands, or combination of changes in product profiles and market shares. For some foods, substitutions of the UPC#’s were made for tracking labels or for collection of samples, further obscuring the situation.

Reducing the sodium content of commercially processed and restaurant foods has been recommended as an effective strategy to reduce sodium intake in the U.S. [12]. Reductions across the food supply are important, as it helps the consumers who may not read labels or are not aware of the need to reduce sodium. Cogswell et al. predicted a reduction of ~700 mg/day (3417 mg/day to 2719 mg/day) in the sodium intake of the U.S. population, aged 1 and older, if the sodium levels were to meet the NSRI targets [43]. The FDA draft long-term targets aim at reductions in sodium intake in the U.S., to ~2300 mg/day. Hence, continued reduction of sodium content of foods is necessary to achieve the population-wide reductions in dietary intake. Several food manufacturers have made consistent efforts and have been successful in reducing the sodium content of their products [44]. These efforts need to be continued, expanded, and accelerated along with monitoring, to ensure the efforts are sustained and any unintended consequences are averted.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of our study include the selection of foods based on dietary intake data from the national survey, use of consistent methodology (statistically valid nationwide sampling, inclusion of major national and private-label brands, chemical analysis of foods using standardized analytical methods) and a two-prong approach (labels from samples, where possible plus chemical analysis, with intent to validate changes in labels) for determining sodium content of Sentinel Foods at baseline and resampling. Furthermore, laboratory analyses can provide information on nutrients not consistently provided on labels, such as potassium.

The limitations of the study include the limited number of Sentinel Foods being tracked (albeit contributing about one-third of the sodium intake, and representative of the top food sources), hence it does not provide a comprehensive review of the changes in the sodium content of foods in the market place in the U.S. The number of foods that were chemically analyzed was further reduced due to resource limitations, leading to selection bias in resampled foods. However, labels were reviewed for all Sentinel Foods, and majority of the labels were found to be accurate when tested at baseline [29]. While similar methodology was used at both time points, except for the change in the source of market-share data, there were instances when there were changes in the products sampled, due to non-availability of the desired products or purchase of different products but very similar front-of-package. Other limitations of the study methods have been previously detailed [19,20].

5. Conclusions

This report provides an update of results from the federal inter-agency Sentinel Foods Surveillance Program. Our results show that some progress had been made in sodium reduction in the market place; however, sodium content for many highly consumed foods continued to be high and variable. Continued efforts are needed by the food manufacturers to lower the sodium content of packaged and restaurant foods, and for public health officials to monitor the progress. Further, the study provides a better understanding of the complexity of sodium monitoring, which may help public health officials to strategize methods and efforts needed to reduce and monitor sodium trends in the food supply.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/8/1754/s1, Table S1: An alphabetical listing of the 125 Sentinel Foods, sorted by food category, Table S2: Methods used for chemical analysis and sample sizes for sodium and related nutrients at baseline and resampling, Table S3: Resampled Sentinel Foods (n = 43) and the corresponding FDA category for voluntary sodium reduction targets.

Author Contributions

J.K.C.A, P.R.P. and M.E.C. designed the research; J.K.C.A, D.B.H. and P.R.P. conducted the research; J.K.C.A, Y.L. and R.B. planned and analyzed the data. J.K.C.A. wrote the manuscript; J.K.C.A. and Y.L. had primary responsibility for final content. All authors reviewed and commented on subsequent drafts of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by USDA-CDC Agreement 60-1235-0-185. And The APC was funded by USDA.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Stallings V., Harrison M., Oria M. Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC, USA: 2019. pp. 1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aburto N.J., Ziolkovska A., Hooper L., Elliott P., Cappuccio F.P., Meerpohl J.J. Effect of Lower Sodium Intake on Health: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];BMJ. 2013 346:f1326. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1326. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/346/bmj.f1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strom B.L., Yaktine A.L., Oria M. Sodium Intake in Populations: Assessment of Evidence. National Academies Press; Washington, DC, USA: 2013. pp. 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carriquiry A., Moshfegh A.J., Steinfeldt L.C., Cogswell M.E., Loustalot F., Zhang Z., Yang Q., Tian N. Trends in the Prevalence of Excess Dietary Sodium Intake—United States, 2003–2010. [(accessed on 16 July 2019)];MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2013 62:1021. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4584577/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. [(accessed on 26 March 2019)]; Available online: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/

- 6.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Food and Nutrient Consumption. NWS-19 Reduce Consumption of Sodium in the Population Aged 2 Years and Older. [(accessed on 26 March 2019)]; Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/objective/nws-19.

- 7.Drewnowski A., Rehm C. Sodium Intakes of US Children and Adults from Foods and Beverages by Location of Origin and by Specific Food Source. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];Nutrients. 2013 5:1840–1855. doi: 10.3390/nu5061840. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/5/6/1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harnack L.J., Cogswell M.E., Shikany J.M., Gardner C.D., Gillespie C., Loria C.M., Zhou X., Yuan K., Steffen L.M. Sources of Sodium in US Adults from 3 Geographic Regions. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];Circulation. 2017 135:1775–1783. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024446. Available online: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024446?url_ver = Z39.88-2003&rfr_id = ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat = cr_pub%3dpubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . Salt Reduction and Iodine Fortification Strategies in Public Health: Report of a Joint Technical Meeting Convened by the World Health Organization and The George Institute for Global Health in Collaboration with the International Council for the Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders Global Network. World Health Organization; Sydney, Australia: Mar, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith-Spangler C.M., Juusola J.L., Enns E.A., Owens D.K., Garber A.M. Population Strategies to Decrease Sodium Intake and the Burden of Cardiovascular Disease: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];Ann. Intern. Med. 2010 152:481–487. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-8-201004200-00212. Available online: https://www.annals.org/article.aspx?doi = 10.7326/0003-4819-152-8-201004200-00212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He F., Brinsden H., MacGregor G. Salt Reduction in the United Kingdom: A Successful Experiment in Public Health. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];J. Hum. Hypertens. 2014 28:345. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2013.105. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/jhh2013105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute of Medicine . Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake in the United States. National Academies Press; Washington, DC, USA: 2010. 297p. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ConAgra Foods ConAgra Foods to Reduce Sodium in Products by 20 Percent by 2015. [(accessed on 27 March 2019)]; Available online: https://www.conagrabrands.com/news-room/news-conagra-foods-to-reduce-sodium-in-products-by-20-percent-by-2015-1342465.

- 14.McDonald’s USA McDonald’s USA: Commitments to Offer Improved Nutrition Choices. [(accessed on 27 March 2019)]; Available online: https://news.mcdonalds.com/news-releases/news-release-details/mcdonalds-usa-commitments-offer-improved-nutrition-choices.

- 15.PR Newswire Kraft Foods on Track to Meet Sodium Reduction Goals Across North American Product Portfolio. [(accessed on 27 March 2019)]; Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/kraft-foods-on-track-to-meet-sodium-reduction-goals-across-north-american-product-portfolio-171344191.html.

- 16.General Mills General Mills Reports Progress on Pledge to Reduce Sodium. [(accessed on 27 March 2019)]; Available online: https://www.generalmills.com/en/News/NewsReleases/Library/2015/December/sodium-reduction.

- 17.City of New York National Salt Reduction Initiative Corporate Commitments. [(accessed on 27 March 2019)]; Available online: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/cardio/nsri-corporate-commitments.pdf.

- 18.US Food and Drug Administration Draft Guidance for Industry: Voluntary Sodium Reduction Goals: Target Mean and Upper Bound Concentrations for Sodium in Commercially Processed, Packaged, and Prepared Foods. [(accessed on 27 March 2019)]; Available online: https://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/ucm494732.htm.

- 19.Ahuja J.K., Wasswa-Kintu S., Haytowitz D.B., Daniel M., Thomas R., Showell B., Nickle M., Roseland J.M., Gunn J., Cogswell M. Sodium Content of Popular Commercially Processed and Restaurant Foods in the United States. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];Prev. Med. Rep. 2015 2:962–967. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.11.003. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211335515001606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahuja J.K., Pehrsson P.R., Haytowitz D.B., Wasswa-Kintu S., Nickle M., Showell B., Thomas R., Roseland J., Williams J., Khan M. Sodium Monitoring in Commercially Processed and Restaurant Foods. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015 101:622–631. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.084954. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4501259/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Research Service. Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center. Group, F.S.R. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics What We Eat in America, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2015–2016. [(accessed on 5 December 2018)]; Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/wweia-data-tables/

- 22.U.S. Department of Agriculture What We Eat in America: Food Categories 2011–2012. [(accessed on 27 March 2019)]; Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/1314/food_category_list.pdf.

- 23.Pehrsson P., Perry C., Daniel M. ARS, USDA Updates Food Sampling Strategies to Keep Pace with Demographic Shifts. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];Procedia Food Sci. 2013 2:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.profoo.2013.04.009. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211601X13000102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pehrsson P., Haytowitz D., Holden J. The USDA’s National Food and Nutrient Analysis Program: Update 2002. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];J. Food Compos. Anal. 2003 16:331–341. doi: 10.1016/S0889-1575(03)00049-8. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0889157503000498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Nielsen Company. [(accessed on 27 March 2019)]; Available online: https://www.nielsen.com/us/en.html.

- 26.Phillips K.M., Patterson K.Y., Rasor A.S., Exler J., Haytowitz D.B., Holden J.M., Pehrsson P.R. Quality-Control Materials in the USDA National Food and Nutrient Analysis Program (NFNAP) [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006 384:1341–1355. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-0294-0. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00216-005-0294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.US Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Research Service. Nutrient Data Laboratory USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 28 (2015) [(accessed on 24 July 2019)]; Documentation and User Guide. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400525/Data/SR/sr28/sr28_doc.pdf.

- 28.Information Resources Inc. (IRI) FreshLook Report. Dataset. Information Resources Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahuja J.K., Li Y., Nickle M.S., Haytowitz D.B., Roseland J., Nguyen Q., Khan M., Wu X., Somanchi M., Williams J. Comparison of Label and Laboratory Sodium Values in Popular Sodium-Contributing Foods in the United States. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019 119:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.08.155. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212267218318665?via%3Dihub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control Prevention Vital signs: Food categories contributing the most to sodium consumption-United States, 2007–2008. MMWR Morbid. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2012;61:92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.S. Food and Drug Administration Title 21: Food and Drugs §101.65 Implied Nutrient Content Claims and Related Label Statements. [(accessed on 28 March 2019)]; Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID = 498a0eac418638c57d5abf4bdbb3751f&mc = true&node = se21.2.101_165&rgn = div8.

- 32.R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [(accessed on 28 February 2019)]; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/

- 33.Lenth R. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. [(accessed on 28 March 2019)]; R Package Version 1.3.2. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package = emmeans.

- 34.U.S. Food and Drug Administration Guidance for Industry: A Food Labeling Guide. [(accessed on 24 July 2019)]; Available online: http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/LabelingNutrition/ucm2006828.htm.

- 35.Gillespie C., Maalouf J., Yuan K., Cogswell M.E., Gunn J.P., Levings J., Moshfegh A., Ahuja J.K., Merritt R. Sodium Content in Major Brands of US Packaged Foods, 2009. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014 101:344–353. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.078980. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/101/2/344/4494391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clapp J.E., Niederman S.A., Leonard E., Curtis C.J. Changes in Serving Size, Calories, and Sodium Content in Processed Foods From 2009 to 2015. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];Prev. Chronic Dis. 2018 15:E33. doi: 10.5888/pcd15.170265. Available online: http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29543584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poti J.M., Dunford E.K., Popkin B.M. Sodium Reduction in US Households’ Packaged Food and Beverage Purchases, 2000 to 2014. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];JAMA Intern. Med. 2017 177:986–994. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1407. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2629447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobson M.F., Havas S., McCarter R. Changes in sodium levels in processed and restaurant foods, 2005 to 2011. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013;173:1285–1291. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfson J.A., Moran A.J., Jarlenski M.P., Bleich S.N. Trends in Sodium Content of Menu Items in Large Chain Restaurants in the US. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018 54:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.08.018. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0749379717304592?via%3Dihub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.U.S. Food and Drug Administration Overview of FDA Labeling Requirements for Restaurants, Similar Retail Food Establishments and Vending Machines. [(accessed on 9 May 2018)]; Available online: https://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/LabelingNutrition/ucm248732.htm.

- 41.U.S. Food and Drug Administration Guidance for Industry: Nutrition Labeling Manual-A Guide for Developing and Using Data Bases. [(accessed on 17 February 2017)]; Available online: https://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/LabelingNutrition/ucm063113.htm#how.

- 42.Gelski J. Shhh! Sodium Reduction in Progress. Food Business News. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)]; Available online: http://www.foodbusinessnews.net/articles/news_home/Consumer_Trends/2013/10/Shhh_Sodium_reduction_in_progr.aspx?ID = %7B1D24AAE5-DF99-4070-86A1-C945A9C37E85%7D&cck = 1.

- 43.Cogswell M.E., Patel S.M., Yuan K., Gillespie C., Juan W., Curtis C.J., Vigneault M., Clapp J., Roach P., Moshfegh A. Modeled Changes in US Sodium Intake from Reducing Sodium Concentrations of Commercially Processed and Prepared Foods to Meet Voluntary Standards Established in North America: NHANES. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017 106:530–540. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.145623. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article-lookup/doi/10.3945/ajcn.116.145623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor C., Doyle M., Webb D. “The Safety of Sodium Reduction in the Food Supply: A Cross-Discipline Balancing Act”—Workshop Proceedings. [(accessed on 9 May 2019)];Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018 58:1650–1659. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2016.1276431. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10408398.2016.1276431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.