Key Points

Question

Has the incidence of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy decreased since the introduction of the John Cunningham virus serologic test and risk-stratification recommendations?

Findings

In this multicenter study of 6318 patients with multiple sclerosis enrolled in the French multiple sclerosis registry, incidence rates were found to have decreased significantly by 23% each year since January 2013, when risk-minimization guidelines were implemented, compared with a 45% yearly increase observed before 2013.

Meaning

This study suggests that risk-minimization strategies should be continued and reinforced in the future to manage disease-modifying drug therapy in multiple sclerosis.

This study uses a French multiple sclerosis cohort to examine the risk of developing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy before and after the release of nationwide risk-minimization recommendations among people with multiple sclerosis who used natalizumab.

Abstract

Importance

Risk of developing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is the major barrier to using natalizumab for patients with multiple sclerosis (MS). To date, the association of risk stratification with PML incidence has not been evaluated.

Objective

To describe the temporal evolution of PML incidence in France before and after introduction of risk minimization recommendations in 2013.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This observational study used data in the MS registry OFSEP (Observatoire Français de la Sclérose en Plaques) collected between April 15, 2007, and December 31, 2016, by participating MS expert centers and MS-dedicated networks of neurologists in France. Patients with an MS diagnosis according to current criteria, regardless of age, were eligible, and those exposed to at least 1 natalizumab infusion (n = 6318) were included in the at-risk population. A questionnaire was sent to all centers, asking for a description of their practice regarding PML risk stratification. Data were analyzed in July 2018.

Exposures

Time from the first natalizumab infusion to the occurrence of PML, natalizumab discontinuation plus 6 months, or the last clinical evaluation.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Incidence was the number of PML cases reported relative to the person-years exposed to natalizumab. A Poisson regression model for the 2007 to 2016 period estimated the annual variation in incidence and incidence rate ratio (IRR), adjusted for sex and age at treatment initiation and stratified by period (2007-2013 and 2013-2016).

Results

In total, 6318 patients were exposed to natalizumab during the study period, of whom 4682 (74.1%) were female, with a mean (SD [range]) age at MS onset of 28.5 (9.1 [1.1-72.4]) years; 45 confirmed incident cases of PML were diagnosed in 22 414 person-years of exposure. The crude incidence rate for the whole 2007 to 2016 period was 2.00 (95% CI, 1.46-2.69) per 1000 patient-years. Incidence significantly increased by 45.3% (IRR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.15-1.83; P = .001) each year before 2013 and decreased by 23.0% (IRR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.61-0.97; P = .03) each year from 2013 to 2016.

Conclusions and Relevance

The results of this study suggest, for the first time, a decrease in natalizumab-associated PML incidence since 2013 in France that may be associated with a generalized use of John Cunningham virus serologic test results; this finding appears to support the continuation and reinforcement of educational activities and risk-minimization strategies in the management of disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis.

Introduction

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is a rare opportunistic infection caused by John Cunningham virus (JCV), a widespread polyomavirus present at latent stage in healthy individuals. In persons who are immunocompromised, JCV can infect oligodendrocytes, leading to their destruction and to clinically devastating and life-threatening consequences.1 Natalizumab, a monoclonal anti–α4 integrin antibody, selectively inhibits binding of lymphocytes on the surface of vascular endothelial cells, precluding their migration in areas of inflammation. Natalizumab has been demonstrated to be highly active in preventing disease activity in multiple sclerosis (MS).2,3

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy was not reported in MS, despite the wide use of immunosuppressants, until the description in 2005 of 2 cases in patients treated with natalizumab.4,5,6 The prevalence of natalizumab-associated PML was estimated to be 1 per 1000 patients with MS (95% CI, 0.2-2.8) after approximately 18 doses.7 This risk was constantly reevaluated by Biogen, the drug’s marketing authorization holder, and with 753 confirmed cases in approximately 177 800 exposed patients with MS, the most recent estimate reached 4.19 per 1000 patients (95% CI, 3.89-4.49) in December 2017.8

The risk of PML is a major limitation to the use of natalizumab. Considerable efforts are needed to better identify patients in whom the risk might outweigh treatment advantages. Since 2012, 3 factors have been associated with an increased risk: exposure to natalizumab for more than 24 months, previous use of immunosuppressants, and a positive JCV serologic test result.9,10 Since 2014, the JCV index has delineated the risk in patients with JCV-positive results.11

However, several experts pointed out the surprising absence of change in the incidence of PML and asked why knowledge of the risk factors did not lead to a decline in overall incidence.12,13,14

In the present study, the objectives were to describe the temporal evolution of the incidence of natalizumab-associated PML in France between April 15, 2007, and December 31, 2016, and to evaluate the association of risk-minimization procedures with PML incidence before and after January 2013.

Methods

We conducted an observational, multicenter study on data collected in OFSEP (Observatoire Français de la Sclérose en Plaques; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02889965), the registry of patients with MS in France. Patients enrolled in OFSEP provided written consent for participation. Confidentiality and safety of OFSEP data are ensured by the recommendations of the French Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL). OFSEP received approval from the Comité Consultatif sur le Traitement de l'Information en matière de Recherche dans le domaine de la Santé and CNIL for storing clinical, biological, and imaging data for research purposes. This study was covered by this general approval and did not require any additional procedure, according to French law.

Patients and Data Collection

OFSEP gathers data on patients with MS, routinely collected by all OFSEP-participating MS expert centers and MS-dedicated networks of neurologists in France, using EDMUS (European Database for Multiple Sclerosis) software to build a comprehensive database of clinical information for their patients with MS.15,16 Patients with an MS diagnosis according to current criteria, regardless of age, are included. Clinical data are collected during routine follow-up visits, usually at least once a year, retrospectively at the first visit and prospectively thereafter. Data collection is based on a minimal mandatory data set, including demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, description of MS, and disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), although much more data can be collected at the investigator’s discretion. Serious adverse events have also been systematically collected since January 2017, but PML occurrence was usually well documented previously.

Population of Interest

The population of interest comprised patients with a diagnosis of MS and PML associated with natalizumab treatment since April 15, 2007 (date of release to market in France). Eligible cases were selected from the OFSEP database. For quality control, the list of identified PML cases was sent to each center to validate the case, the certainty of PML diagnosis (whether definitive or suggestive of the disease, according to the acknowledged criteria17), the date of PML onset, and whether each patient was followed up by the center before onset or was referred because of the suggestion of PML. The OFSEP participating centers were also asked to complete PML reports that were missing. Patients in whom the presence of PML was merely suspected were excluded, as were patients referred for PML diagnostic workup who were not already included in the OFSEP database. Those cases did not contribute to the at-risk population and did not reflect the practice of the OFSEP investigators.

At-Risk Population

All patients exposed to at least 1 infusion of natalizumab since April 15, 2007, were included in the at-risk population, allowing an estimation of the person-years for exposure. Patients exposed only in the setting of clinical trials before April 2007 were excluded. The year 2017 was not included in the analysis owing to a delay in data entry in some centers that would have underestimated the at-risk population, whereas the collection of PML cases was likely to be exhaustive until December 2018. This data-entry delay has been described in other registry studies.18 Previous unpublished analyses of OFSEP data have also shown that data can be considered valid after 18 months; therefore, we censored all data on December 31, 2016.

The period of interest for each patient was defined from the date of the first natalizumab infusion to the occurrence of either the event of interest (ie, PML), natalizumab discontinuation plus 6 months (as PML cases can be diagnosed in the 6 months after stopping treatment, which still constitutes an at-risk period), or the last clinical evaluation if the patient was still under treatment.

Risk Mitigation Practice Survey

A questionnaire was sent to all centers, asking for a description of their practice regarding PML risk stratification. The survey included questions about risk factors, the timeline and process for modifying the practice in case of an indication of natalizumab, the treatment duration, and specific follow-up plans (JCV testing frequency and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] follow-up).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the incidence of natalizumab-associated PML by year, between 2007 and 2016, and stratified in 2 periods of before and after 2013. This outcome allowed us to evaluate the potential implications of the risk mitigation strategy. January 2013 was predefined as the cutoff date, as the JCV serologic test has been commonly used in France since 2012. We hypothesized that it would take at least 1 year to disseminate and apply the mitigation strategy and observe the consequences.

Secondary outcomes were the conditional survival by treatment duration and description of risk mitigation procedures among OFSEP centers.

Statistical Analysis

Crude annual PML incidence rates were estimated as the number of PML cases identified by calendar year relative to the number of person-years exposed to natalizumab each year from 2007 to 2016. A univariate Poisson regression model integrated the year as a linear covariate and patient-years exposed to natalizumab as the offset term. This model allowed estimation of the annual variation in incidence rate ratios (IRRs). A multivariate analysis was performed, adjusting for sex and age at treatment initiation, along with a stratified analysis by period before and after 2013. The variances of the regression estimators were identified through the sandwich method in which robust estimators and CIs of IRR estimators were calculated by using the delta method. Performance of the models was assessed through residuals and overdispersion of the data by Pearson residuals, residual deviance, and the Cameron and Trivedi test.19

To identify the probabilities of developing PML as a function of treatment duration, we estimated the conditional probabilities for each 12-month interval from 0 to 96 months. Each interval [Mi, Mj]i < j provides the probability of developing PML at month Mj, assuming there was no PML at month Mi. Conditional survival probabilities (S) were estimated by dividing the probability of survival at month Mj by the probability of survival at month Mi; conditional probabilities of developing PML were deduced by complementarity (1−S). Variances were given by a variation of the usual Greenwood formula for unconditional survival.20

Data analyses were performed in July 2018 with SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc), and R, version 3.4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

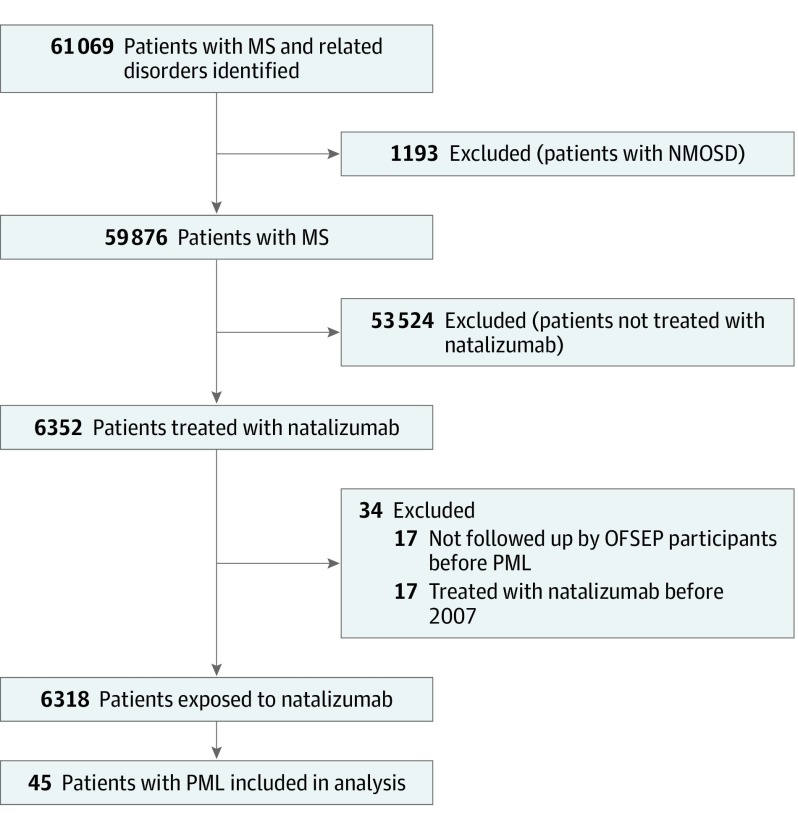

By June 15, 2018, the OFSEP cohort comprised 59 876 patients with MS. In total, 6352 (10.6%) received at least 1 infusion of natalizumab, 17 of whom were excluded because they were referred after the diagnosis of PML. A total of 6318 (10.6%) were included in the at-risk population (Figure 1), of whom 4682 (74.1%) were female, with a mean (SD [range]) age at MS onset of 28.5 (9.1 [1.1-72.4]) years. The mean (SD [range]) treatment duration was 39.6 (30.2 [0.03-164.8]) months. Of the 6318 at-risk patients, 1372 (21.7%) were exposed to at least 1 immunosuppressant before natalizumab.

Figure 1. Study Flowchart.

MS indicates multiple sclerosis; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; OFSEP, Observatoire Français de la Sclérose en Plaques (French MS registry); and PML, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

Originally, 61 cases of PML were registered in the OFSEP, and 10 additional cases were reported during the validation procedure. Twenty-six cases were excluded from the analysis, because 2 were only suggestive of PML but not confirmed by polymerase chain reaction testing of cerebrospinal fluid or brain biopsy, 7 occurred after 2016 (5 in 2017 and 2 in 2018), and 17 were not followed up by centers before the diagnosis of PML. Forty-five patients with definite PML were analyzed, of whom 31 (68.9%) were female and the mean (SD [range]) age was 28.7 (6.7 [17.4-42.6]) years at MS onset and 43.5 (7.0 [27.1-58.8]) years at PML onset. In 8 cases (17.7%), PML started after natalizumab discontinuation (5 in the first 3 months, and 3 between 3 and 6 months). The mean (SD [range]) treatment duration was 52.0 (24.2 [4.7-117.1]) months. One case (2.2%) occurred in the first 12 months of treatment, 3 in year 2, 5 in year 3, 18 in year 4, and 18 after 4 years. Ten patients (22.2%) were exposed to at least 1 immunosuppressant before natalizumab. Eleven patients (24.4%) died.

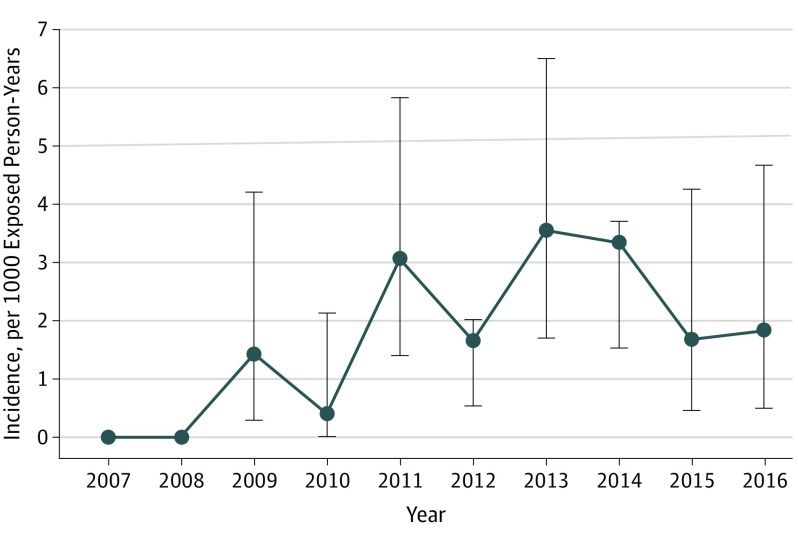

Evolution of Annual Crude Incidence Rates of PML

The crude incidence rate of PML between 2007 and 2016 was 2.00 (95% CI, 1.46-2.69) per 1000 person-years, corresponding to 45 patients with PML and 22 414 person-years exposed to natalizumab (Figure 2). Yearly incidence rates increased until 2013 (3.54 [95% CI, 1.7-6.5] per 1000 person-years) and decreased thereafter to 1.66 (95% CI, 0.45-4.26) in 2015 and 1.82 (95% CI, 0.5-4.67) in 2016. Although the natalizumab-exposed population cannot yet be exactly assessed for 2017 and 2018, we can provide the annual numbers of incident PML cases: 5 in 2017 and 2 in 2018. These data are consistent with the data for the pharmacovigilance reporting to Biogen France and confirm the demonstrated trend.

Figure 2. Evolution of Annual Crude Incidence Rates of Natalizumab-Associated Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy in France Between 2007 and 2016.

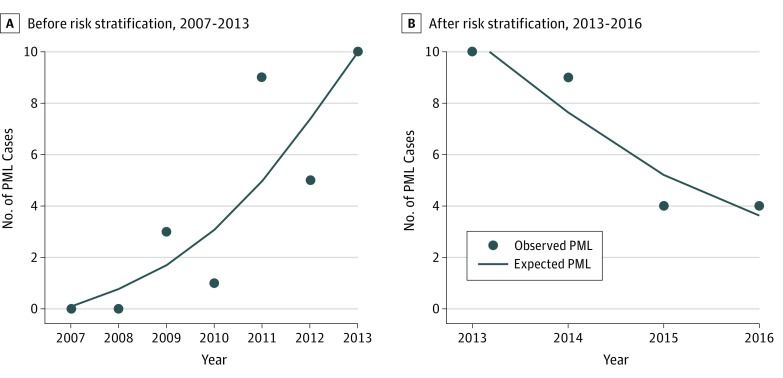

Stratification by Period

For the 2007 to 2013 period, the univariate Poisson regression showed a statistically significant increase in the incidence of PML (IRR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.15-1.80; P = .001), corresponding to a modeled yearly increase by 43.9% (Table; Figure 3). The multivariate analysis, introducing sex and age at treatment onset as covariates, confirmed the statistically significant incidence increase by 45.3% (IRR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.15-1.83; P = .001). Sex was not associated with the risk of PML. Younger patients (<30 years) were statistically significantly less likely to develop PML (IRR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.06-0.67; P = .009), with a reduction by more than 80% of their risk as compared with the oldest patients. Pearson residual analysis and residuals deviance confirmed good quality (P = .71) and good fit (P = .70) of the model, with no overdispersion (P = .24).

Table. Multivariate Analysis of the Incidence of Natalizumab-Associated Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy Evolution.

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P Value | IRR (95% CI) | Coefficient (95% CI) | P Value | IRR (95% CI) | |

| Overall, 2007-2016 | ||||||

| Year | 0.12 (−0.02 to 0.25) | .09 | 1.12 (0.98 to 1.29) | 0.12 (0.01 to 0.24) | .04 | 1.13 (1.00 to 1.27) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | NA | NA | NA | 0.22 (−0.41 to 0.86) | .49 | 1.25 (0.66 to 2.36) |

| Female | NA | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |

| Age group, y | ||||||

| <30 | NA | NA | NA | −1.19 (−1.95 to −0.43) | .002 | 0.30 (0.14 to 0.65) |

| 30-40 | NA | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |

| ≥40 | NA | NA | NA | −0.15 (−0.83 to 0.54) | .68 | 0.86 (0.43 to 1.72) |

| Before Risk Stratification, 2007-2012 | ||||||

| Year | 0.36 (0.14 to 0.59) | .001 | 1.44 (1.15 to 1.80) | 0.37 (0.14 to 0.60) | .001 | 1.45 (1.15 to 1.83) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | NA | NA | NA | 0.10 (−0.77 to 0.98) | .82 | 1.11 (0.46 to 2.65) |

| Female | NA | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |

| Age group, y | ||||||

| <30 | NA | NA | NA | −1.5927 (−2.7874 to −0.3981) | .009 | 0.203 (0.06 to 0.67) |

| 30-40 | NA | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |

| ≥40 | NA | NA | NA | −0.07 (−1.01 to 0.86) | .88 | 0.93 (0.36 to 2.37) |

| After Risk Stratification, 2013-2016 | ||||||

| Year | −0.27 (−0.36 to −0.18) | <.001 | 0.76 (0.70 to 0.84) | −0.26 (−0.50 to −0.03) | .03 | 0.77 (0.61 to 0.97) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | NA | NA | NA | −0.47 (−0.02 to 0.97) | .06 | 1.60 (0.98 to 2.63) |

| Female | NA | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |

| Age group, y | ||||||

| <30 | NA | NA | NA | −0.83 (−1.54 to −0.12) | .02 | 0.44 (0.21 to 0.88) |

| 30-40 | NA | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |

| ≥40 | NA | NA | NA | 0.04 (−0.47 to 0.54) | .89 | 1.04 (0.63 to 1.71) |

Abbreviations: IRR, incidence rate ratio; NA, not applicable.

Figure 3. Poisson Regression Graphical Representation of the Risk of Natalizumab-Associated Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML) Before and After 2013.

By contrast, in the 2013 to 2016 period, the univariate analysis found a statistically significant decrease in the incidence of PML (IRR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.70-0.84; P < .001), that is, a yearly reduction by 23.6%. This decrease remained statistically significant in the multivariate analysis (IRR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.61-0.97; P = .03), with a trend toward a more important risk in male patients (IRR, 1.60; 95% CI, 0.98-2.63; P = .06) and a statistically significantly lower risk in younger patients (IRR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.21-0.89; P = .02). Pearson residual analysis and residuals deviance confirmed good quality (P = .95) and good fit (P = .79) of the model, with no overdispersion (P = .99).

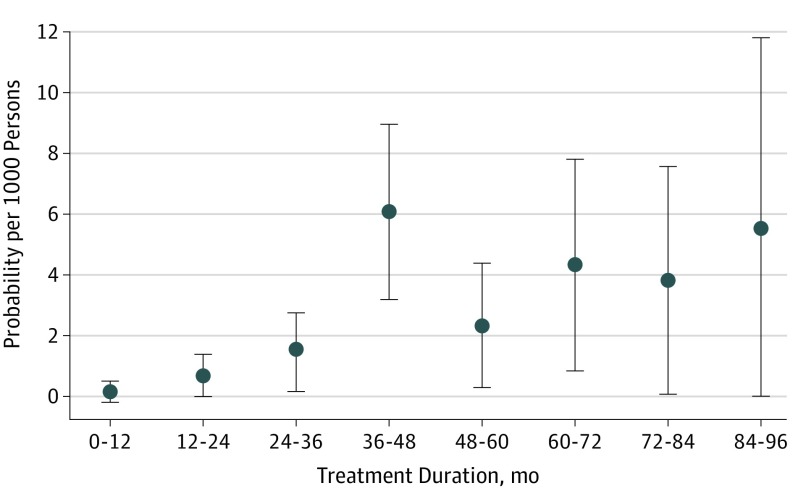

Conditional Probability of Developing PML by Treatment Duration

The probability of developing PML in a time interval, assuming the patient developed no PML before and was still exposed to natalizumab, increased from the second year onward to reach the highest figure in the fourth year of exposure, 6.1 per 1000 patients (95% CI, 3.2-8.99) (Figure 4). The decrease observed thereafter had to be considered with caution, given that CIs were wide, numbers of patients were low, and a depletion in at-risk persons for longer duration occurred as mainly patients with seronegative JCV test results continued natalizumab.

Figure 4. Conditional Survival Estimates of the Risk of Natalizumab-Associated Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy by Treatment Duration.

Risk Mitigation Procedures in Practice

The questionnaire was completed by 33 (97.1%) of the 34 participating centers. All centers declared using JCV test results in the care of their patients: 33 (97.1%) at natalizumab initiation and 1 (2.9%) after 18 months (eTable in the Supplement).

Three centers (9.1%) never used natalizumab in patients with JCV-positive results. Of 30 centers, 26 (86.7%) used JCV index, with variable high-risk thresholds: 0.7 in 2 centers, 0.9 in 22, and 1.5 in 4.

In patients with JCV-negative results, retesting is done every 6 months in 30 (90.9%) of 33 centers, more frequently (3-4 months) in 2 (6.1%), and only annually in 1 (3.0%). An MRI follow-up is done annually in 27 centers (81.8%) and every 6 months in 6 (18.2%).

In patients with JCV-positive results with a low index (according to the local threshold), retesting is done every 6 months in 24 (75%) of 32 centers, more frequently (3-4 months) in 7 (21.9%), and only annually in 1 (3.1%). An MRI follow-up is done more frequently in 28 centers (87.5%; quarterly in 11, biannually in 17 centers), after 12 (8 centers), 18 (9 centers), or 24 (8 centers) months of exposure and since onset in 3 centers (9.4%). Retesting is done annually in 4 centers (12.5%).

In patients with JCV-positive results with a high index, MRI follow-up is increased to every 3 months in 27 of 29 centers (93.1%), every 6 months in 2 centers (6.9%), after 12 months in 8 centers (27.6%), after 18 months in 12 centers (41.4%), and after 24 months in 4 centers (13.8%). After 24 months of exposure in high-index patients, 13 of 31 centers (41.9%) systematically stop natalizumab, 20 (64.5%) discuss the balance between advantages and risks as well as alternative drugs in expert consensus meetings and with the patients, and 6 (19.4%) also include CD62L dose in the discussion.

Discussion

The risk of PML is the main limitation to the use of natalizumab, one of the most effective DMTs available for preventing inflammation in MS. To our knowledge, this study is the first to describe at the national level a statistically significant decrease in the incidence of natalizumab-associated PML since 2013. In the study, 2 cases that were only suggestive of PML were excluded. Both cases occurred before 2013, and including them in the analysis would have strengthened the main result.

OFSEP is a national registry representing more than half of patients with MS in France. Recruitment into OFSEP is mainly hospital-based, but coverage of patients receiving immunoactive treatments, especially those administered in hospital centers only, is even higher. Recording of serious adverse events is mandatory since 2017. However, for such a severe condition with consequences on future treatment decisions, notification was preexisting in most cases. Identification of PML cases was likely to reach exhaustivity within the OFSEP network. Owing to the high-level expertise at all OFSEP centers, underdetection leading to underestimation of the number of cases is unlikely to have occurred, especially in the latter years of our study. The at-risk population can be considered reliable, as treatment start and stop dates are mandatory. In considering extrapolation to the whole French population, it would seem likely that, owing to the high level of expertise of OFSEP centers, risk mitigation procedures might have been applied earlier and more systematically than at non-OFSEP centers.

Until now, the only available data on the evolution of PML incidence come from Biogen.8 In December 2017, the incidence of PML was reported to be 4.19 per 1000 patients (95% CI, 3.89-4.49), without substantial evolution over time. This rate is not truly incidence, but rather the number of PML cases divided by the number of exposed patients. In 2016, Campagnolo et al21 reported that PML incidence increased by 0.067 per month until September 2013 but only 0.027 from September 2013 to June 2016, a 50% decrease in the slope of the curve. No methodologic details were given on how incidence was calculated, but we found from a previous paper that each point was computed from the total number of PML cases and the total exposure to natalizumab.22 Recently updated results confirm a stabilization of this incidence rate since mid-2016.23

Assigning causal relationships for the observed decrease in PML incidence in France since 2013 is not possible. However, we can speculate that the decrease in high-risk individuals could have been a factor. In France, natalizumab is indicated as a second-line therapy in highly active MS. Access was accompanied by a risk mitigation plan, including educational documents for neurologists, patients, and families. Testing for JCV was made available to all French neurologists and was supplied by Biogen in early 2012, and the JCV index was made available in August 2015. According to our survey, OFSEP participants not only applied the recommendations but also were even more cautious: 9.1% never used natalizumab in patients with JCV-positive results, whatever the JCV index; 82.8% used a threshold of 0.9 or less for treatment decision, rather than 1.5; 96.5% discontinued natalizumab in patients with JCV-positive results, after 24 months in one-half of patients and as early as 12 to 18 months in the other half. By contrast, few clinicians (12.1%) increase interval doses, as recently described.24

Data from the present study showed a decrease in the number of person-years exposed to natalizumab since 2012, which might be associated with the application of risk mitigation procedures and access to new DMTs, especially fingolimod, since 2012. The annualized seroconversion rate of patients using natalizumab is higher than 5%, cumulatively leading to more than 25% of patients with seronegative results receiving seropositive results after 4 years and to the discontinuation of natalizumab use in a considerable number of patients.25

In addition, this study showed that age was an independent risk factor for PML, as previously reported by the Italian registry.26 This finding might be associated with the increase in JCV seroprevalence with age27 as well as with immune senescence, to some extent.28

Although the overall incidence of PML decreased recently, PML did not disappear. Use of natalizumab was maintained despite risk factors in patients for whom the fear of a poorer control of MS activity exceeded the risk perception. Our survey showed that only 41.9% of the OFSEP centers systematically discontinued natalizumab in patients with JCV-positive results and a high index after 24 months. Unfortunately, we had no access to the JCV status in this study, as it is not systematically requested in OFSEP. However, the details of real-world practice could be explored in the future by incorporating the risk factors in systematic data collection. The situation could also change rapidly with approval of new DMTs, such as anti-CD20 agents, that are efficacious for inflammation but pose much less risk of PML. Patients at increased risk of PML, therefore, either would not be exposed to natalizumab at all or would be switched after 18 to 24 months. Among the challenges of the coming years would be to evaluate the implications of these new therapeutic strategies for long-term disability progression and for the risk of PML and other serious adverse events in patients exposed sequentially to different DMTs.

Limitations

There are 2 major limitations to our study. First, although OFSEP is the sole French national MS registry, it is not population-based and represents only one-half of patients with MS in France. OFSEP patients are more actively treated and more frequently exposed to second-line therapies.16 They are also very well described, with an exhaustive reporting of PML cases by expert MS neurologists and a comprehensive description of exposure to DMTs. Although our results may not be generalizable to the whole population of patients with MS, our results may at least reflect the situation in patients followed in MS expert centers. Second, it is not possible to assess causality in such a study, especially in the absence of JCV serologic testing results in the database. We tried to overcome this limitation by providing an almost exhaustive (33/34 centers) declarative description of the participating centers’ risk mitigation practices. In the future, causality could be explored further by collecting risk factors in detail at the individual patient level and by reproducing the same analysis in other similar MS registries, in particular those collaborating in the BigMSData network.

Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated that natalizumab-associated PML incidence in France has decreased since 2013, in a temporal concomitance with the introduction of risk mitigation guidelines. Although a causal relationship cannot be established, we believe this finding encourages the continuation and reinforcement of educational activities to prevent the risk of PML.

eTable. Survey on PML Risk Minimization Procedures Among the 34 OFSEP Participating Centers

References

- 1.Major EO, Yousry TA, Clifford DB. Pathogenesis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and risks associated with treatments for multiple sclerosis: a decade of lessons learned. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(5):467-480. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30040-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polman CH, O’Connor PW, Havrdova E, et al. ; AFFIRM Investigators . A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(9):899-910. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudick RA, Stuart WH, Calabresi PA, et al. ; SENTINEL Investigators . Natalizumab plus interferon beta-1a for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(9):911-923. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger JR. Classifying PML risk with disease modifying therapies. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;12:59-63. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Tyler KL. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy complicating treatment with natalizumab and interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):369-374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langer-Gould A, Atlas SW, Green AJ, Bollen AW, Pelletier D. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with natalizumab. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):375-381. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yousry TA, Major EO, Ryschkewitsch C, et al. Evaluation of patients treated with natalizumab for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(9):924-933. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.PML assessment update. https://www.biogen-international.com/content/corporate/en/medical-professionals/dcsecure/tysabri-update.html. Accessed July 24, 2019.

- 9.Bloomgren G, Richman S, Hotermans C, et al. Risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(20):1870-1880. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sørensen PS, Bertolotto A, Edan G, et al. Risk stratification for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients treated with natalizumab. Mult Scler. 2012;18(2):143-152. doi: 10.1177/1352458511435105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plavina T, Subramanyam M, Bloomgren G, et al. Anti-JC virus antibody levels in serum or plasma further define risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(6):802-812. doi: 10.1002/ana.24286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cutter GR, Stüve O. Does risk stratification decrease the risk of natalizumab-associated PML? Where is the evidence? Mult Scler. 2014;20(10):1304-1305. doi: 10.1177/1352458514531843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho PR, Koendgen H, Campbell N, Haddock B, Richman S, Chang I. Risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with multiple sclerosis: a retrospective analysis of data from four clinical studies. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(11):925-933. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30282-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Derfuss T, Kappos L. PML risk and natalizumab: the elephant in the room. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(11):864-865. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30335-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Confavreux C, Compston DA, Hommes OR, McDonald WI, Thompson AJ. EDMUS, a European database for multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55(8):671-676. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.8.671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vukusic S, Casey R, Rollot F, et al. ; the OFSEP Investigators . Observatoire Français de la Sclérose en Plaques (OFSEP): a unique multimodal nationwide MS registry in France [published online December 13, 2018]. Mult Scler. 2018. doi: 10.1177/1352458518815602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berger JR, Aksamit AJ, Clifford DB, et al. PML diagnostic criteria: consensus statement from the AAN neuroinfectious disease section. Neurology. 2013;80(15):1430-1438. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828c2fa1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institut de Veille Sanitaire, INSERM. Registres epidemiologiques et acces aux sources de donnees standardisees: etat des lieux et perspectives d’amelioration [in French]. Comite National des Registres. https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/Contribution_du_Comite_national_des_registres_InVs-Inserm_-propositions.pdf. Accessed July 24, 2019.

- 19.Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Regression-based tests for overdispersion in the Poisson model. J Econom. 1990;46(3):347-364. doi: 10.1016/0304-4076(90)90014-K [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenwood M. A report on the natural duration of cancer In: Greenwood M. Reports on Public Health and Medical Subjects. Ministry of Health. London, UK: HMSO; 1926: iv. https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19272700028. Accessed July 25, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campagnolo D, Dong Q, Lee L, Ho PR, Amarante D, Koendgen H. Statistical analysis of PML incidences of natalizumab-treated patients from 2009 to 2016: outcomes after introduction of the Stratify JCV® DxSelect™ antibody assay. J Neurovirol. 2016;22(6):880-881. doi: 10.1007/s13365-016-0482-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Werner MH, Huang D. Natalizumab-treated patients at high risk for PML persistently excrete JC polyomavirus. J Neurovirol. 2016;22(6):871-875. doi: 10.1007/s13365-016-0449-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giovannoni G, Kappos L, Berger J, et al. Incidence of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy and its relationship with the pattern of natalizumab exposure over time. https://onlinelibrary.ectrims-congress.eu/ectrims/2018/ectrims-2018/228448/gavin.giovannoni.incidence.of.natalizumab-associated.progressive.multifocal.html?f=listing%3D0%2Abrowseby%3D8%2Asortby%3D1%2Asearch%3Dgiovannoni. Accessed January 2, 2019.

- 24.Yamout BI, Sahraian MA, Ayoubi NE, et al. Efficacy and safety of natalizumab extended interval dosing. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;24:113-116. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2018.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vennegoor A, van Rossum JA, Leurs C, et al. High cumulative JC virus seroconversion rate during long-term use of natalizumab. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23(6):1079-1085. doi: 10.1111/ene.12988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prosperini L, Scarpazza C, Imberti L, Cordioli C, De Rossi N, Capra R. Age as a risk factor for early onset of natalizumab-related progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neurovirol. 2017;23(5):742-749. doi: 10.1007/s13365-017-0561-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsson T, Achiron A, Alfredsson L, et al. Anti-JC virus antibody prevalence in a multinational multiple sclerosis cohort. Mult Scler. 2013;19(11):1533-1538. doi: 10.1177/1352458513477925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mills EA, Mao-Draayer Y. Aging and lymphocyte changes by immunomodulatory therapies impact PML risk in multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2018;24(8):1014-1022. doi: 10.1177/1352458518775550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Survey on PML Risk Minimization Procedures Among the 34 OFSEP Participating Centers