Abstract

Background:

Ecuador’s caesarean delivery rate far exceeds that recommended by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and the World Health Organization (WHO). Using data from three iterations of Ecuador’s nationally representative, population-based survey Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición (ENSANUT/ENDEMAIN), spanning 23 years, this study aims to compare mode of delivery outcomes by sociodemographics and labor and delivery (L&D) care institution in light of Ecuador’s major healthcare reform over the past two decades.

Methods:

Using data from the 1994, 2004, and 2012 iterations of the dataset, descriptive statistics were used to demonstrate trends in caesarean delivery based on province, year, and institution of L&D care. Logistic regression was used to test the odds of caesarean delivery based on institution of L&D care, sociodemographics, and pregnancy and birth complications. Predicted probabilities were derived from this model.

Results:

Ecuador’s rate of caesarean delivery increased from 22% in 1989 to 41% in 2012. Each year, the predicted probability of delivering by caesarean is highest in private institutions and those covered by insurance, and from 2008 to 2012, the predicted probability of delivering by caesarean in private centers is significantly higher than that in public centers. Sociodemographic characteristics also predicted risk of caesarean delivery.

Conclusions:

In order to decrease the adverse effects of caesarean delivery for women and their babies, caesarean delivery without medical indication should be reduced. Future research should investigate how mothers perceive delivering by caesarean and how medical indication is defined and used within health centers.

Introduction

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommend a national caesarean delivery rate of between 5 and 15% and suggest that anything higher may be motivated by factors other than medical risk.1 In Ecuador, caesarean delivery prevalence rose from 17.1% in 1994 to 41.2% in 2012.2 While caesarean deliveries can be imperative for the immediate health of a woman and her child, unnecessary caesarean deliveries are associated with increased morbidity and mortality for both mother and the infant.3,4 Women who deliver by caesarean are at higher risk for infection, venous thromboembolism, abnormal placentation, placenta accreta, uterine rupture, cardiac arrest, and hysterectomy than those who deliver vaginally.5,6 Further, delivery is a critical phase in perinatal experience, and considerable evidence demonstrates a relationship between mode of delivery and long-term development. Specifically, caesarean delivery has been associated with increased risk of low birthweight, reduced breast-feeding initiation and duration, and increased risk of metabolic syndrome, asthma, diabetes, gastrointestinal disease, respiratory infections, and overweight and obesity in offspring later in life.7–10

The increase in prevalence of caesarean delivery in Ecuador may be due in part to Ecuador’s social and economic change and health care system restructuring since the 1980s. Over the past three decades, Ecuador’s health care system has transitioned from primarily private to increasingly public care, and it is now made up of three separate segments: The Ministry of Health, which serves the public sector, primarily the lowest-income groups; the social security branch, which accepts insurance; and the private sector, which serves the wealthiest individuals.11 During this same era, Ecuador’s economy shifted tremendously; the gross national income (GNI) quadrupled from 2000–2014, and Ecuador emerged as a middle-income country.12 These changes have likely shaped the prevalence of caesarean delivery, the profiles of women who deliver by caesarean, and decision-making around mode of delivery.

While Ecuador’s rate of caesarean delivery is rising, little is known about the factors shaping its risk. The objectives of this study were to compare how labor and delivery (L&D) care and maternal characteristics shape risk of caesarean delivery in Ecuador from 1989 to 2012. Using Ecuador’s national health and nutrition surveys, we tested differences in rates of caesarean delivery based on L&D institution over time and analyzed how sociodemographic characteristics contribute to risk of caesarean delivery. Last, we investigated women’s motivations for selecting L&D institutions to provide context on how women select care institutions.

Methods

Sample

Data came from three iterations of Ecuador’s nationally-representative health and nutrition survey: Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Materna e Infantil (ENDEMAIN) 1994, ENDEMAIN 2004, and Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición (ENSANUT) 2012. These surveys were used together to analyze how Ecuador’s caesarean delivery rate has changed from 1989 to 2012 alongside sociodemographic characteristics and changes to the healthcare system. Surveys were cross-sectional and participants were not followed from one survey to the next. ENSANUT participants were chosen through multistage, stratified sampling based on urbanicity, region, and province. Our analytic sample includes only a woman’s most recent birth in the past five years. The total sample included more than 16,900 women ages 12 to 49. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Measures

Data on mode of delivery were collected by maternal report. While no distinctions were made between medically indicated, emergency, and elective caesarean deliveries, participants reported pregnancy and birth complications. Using this data, medical indication for caesarean delivery was defined as symptoms of preeclampsia and eclampsia (blurred vision, high blood pressure, convulsions, fainting, and extreme headache) or a fetal malpresentation during delivery. Data on these complications were available for all women in the 2012 dataset, but only for women who gave birth during or after January 1992 in the 1994 dataset and during or after January 2002 in the 2004 dataset.

Sociodemographic characteristics include maternal age, self-identified ethnicity (mestiza; indigenous; white; black; and other), primary language (Spanish; indigenous), urbanicity (urban; rural), education (none; primary school; secondary school; and superior/postdoc), income (divided into quartiles), parity (based on viable pregnancies), initial prenatal care visit month, number of prenatal care visits, and the institution of L&D care (public; social security; private; and other). Ethnicity was only available in the 2004 and 2012 datasets. The 2012 data reported more refined ethnic categories than the 2004 dataset and thus were collapsed into the 2004 categories. Monthly income was only available for the 2012 dataset. Income was recorded in US dollars and was divided into quartiles based on the distribution of the data. The quartiles are referred to as: lower (≤$50), lower-middle (>$50 and ≤$170), upper-middle (>$170 and ≤$300), and upper (>$300).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the characteristics of women and to demonstrate trends in caesarean delivery based on province, year, and institution of L&D care. Chi-square tests and t-tests were run to determine associations between sociodemographic characteristics and mode of delivery.

Next, using data pooled from 1992 to 2012, backwards stepwise selection was used to select covariates, and logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the relationship between the institution of L&D care and mode of delivery. Based on this model, we derived the predicted probability for caesarean delivery based on L&D institution using marginal standardization, which is the most appropriate method of predicting probabilities when making inferences to the overall population.13 The model was adjusted for the selected covariates: urbanicity, maternal age, parity, primary language, education, initial prenatal care month, number of prenatal care visits, and medical indications. The data used for this analysis came only from women who gave birth from 1992 – 1994, 2002 – 2004, or 2007 – 2012 due to constraints on data for pregnancy complications, which were not available from 1989 – 1991 and 1999 – 2001. Ethnicity and income were excluded from this model because they were not reported in each iteration of the dataset. Women who delivered at home, with a midwife, or elsewhere were excluded from this analysis (n=3,293). We then ran tests to determine in which L&D care institutions predicted probabilities of caesarean delivery were significantly different from each of the other L&D institution types in each of the given years. A sensitivity analysis was conducted limiting the sample to primiparous women (n = 3,453) to assess whether results from the whole sample were biased by repeated caesarean deliveries, since performing a vaginal delivery after caesarean (VBAC) is rare in Ecuador. Results from the sensitivity analysis were consistent with results from the full sample.

Last, basic descriptive statistics were run on a subset of women who gave birth from 2007 – 2012 to describe their motivations for using particular types of L&D institutions to provide additional context.

Results

Caesarean Delivery Prevalence and Utilization of Health Care

The rate of caesarean delivery in Ecuador increased from 22.43% in 1989 to 40.61% in 2012. It reached a low in 1993 at 14.51% and a high in 2008 at 44.28%. Caesarean delivery prevalence increased most in private centers, where caesarean delivery rates rose from 32.81% from 1989 – 1994 to 64.71% from 2007 – 2012 [Table 1].

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and risk factors for caesarean delivery

| ENDEMAIN 1994 (1989 – 1994) |

ENDEMAIN 2004 (1999 – 2004) |

ENSANUT 2012 (2007 – 2012) |

Total Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Sample N = 6417 |

Caesarean Delivery N = 1108 (17.27%) |

Whole Sample N = 3617 |

Caesarean Delivery N = 1282 (35.44%) |

Whole Sample N = 6893 |

Caesarean Delivery N = 2725 (39.53%) |

||

| Age | 29.93 ± 7.26 | 30.69 ± 6.66*** | 28.84 ± 7.03 | 29.80 ± 7.00*** | 28.26 ± 7.00 | 29.17 ± 7.07*** | 29.42 ± 7.38 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Mestiza | -- | -- | 3768 (77.37%) | 1094 (35.98%)*** | 5957 (76.88%) | 2324 (41.69%)*** | -- |

| Indigenous | -- | -- | 572 (11.75%) | 33 (19.53%)*** | 1102 (14.22%) | 121 (17.46%)*** | -- |

| White | -- | -- | 297 (6.10%) | 106 (41.25%)*** | 111 (1.43%) | 54 (52.43%)*** | -- |

| Black | -- | -- | 188 (3.86%) | 36 (31.58%)*** | 222 (2.87%) | 64 (32.65%)*** | -- |

| Other | -- | -- | 45 (0.92%) | 13 (36.11%)*** | 356 (4.59%) | 162 (49.54%)*** | -- |

| Language | |||||||

| Spanish | 6120 (95.37%) | 1100 (17.97%)*** | 4619 (95.10%) | 1273 (35.75%)*** | 7183 (92.70%) | 2667 (40.52%)*** | 16548 (94.43%) |

| Indigenous | 297 (4.63%) | 8 (2.69%)*** | 238 (4.90%) | 8 (14.55%)*** | 566 (7.30%) | 58 (18.65%)*** | 976 (5.57%) |

| Urbanicity | |||||||

| Urban | 3132 (48.81%) | 796 (25.42%)*** | 2480 (50.92%) | 879 (39.42%)*** | 4562 (58.86%) | 1930 (44.49%)*** | 9965 (56.85%) |

| Rural | 3285 (51.19%) | 312 (9.50%)*** | 2390 (49.08%) | 403 (29.06%)*** | 3189 (41.14%) | 795 (31.10%)*** | 7564 (43.15%) |

| Education | |||||||

| None | 501 (7.81%) | 24 (2.17%)*** | 24 (0.51%) | 5 (35.71%)*** | 121 (1.56%) | 22 (27.85%)*** | 653 (3.26%) |

| Primary school | 3171 (49.42%) | 352 (11.10%)*** | 2224 (47.49%) | 376 (27.77%)*** | 2405 (31.04%) | 616 (31.70%)*** | 8332 (41.60%) |

| Secondary school | 2123 (33.08%) | 486 (22.89%)*** | 1843 (39.36%) | 599 (36.98%)*** | 3991 (51.50%) | 1441 (39.26%)*** | 8385 (41.86%) |

| Superior/Postgrad | 622 (9.69%) | 246 (39.55%)*** | 592 (12.64%) | 285 (50.71%)*** | 1232 (15.90%) | 646 (53.79%)*** | 2661 (13.28%) |

| Income | |||||||

| Lower | -- | -- | -- | -- | 811 (25.28%) | 192 (32.82%)*** | -- |

| Lower-middle | -- | -- | -- | -- | 796 (24.81%) | 259 (37.65%)*** | -- |

| Upper-middle | -- | -- | -- | -- | 858 (26.75%) | 304 (39.02%)*** | -- |

| Upper | -- | -- | -- | -- | 743 (23.16%) | 366 (50.48%)*** | -- |

| L&D Institution | |||||||

| Public | 2287 (36.19%) | 440 (19.24%)*** | 2066 (43.17%) | 527 (25.51%)*** | 4936 (64.28%) | 1483 (30.04%)*** | 8362 (50.36%) |

| Social Security | 336 (5.32%) | 141 (41.96%)*** | 152 (3.18%) | 78 (51.32%)*** | 343 (4.47%) | 197 (57.43%)*** | 810 (4.88%) |

| Private | 1530 (24.21%) | 502 (32.81%)*** | 1399 (29.23%) | 677 (48.39%)*** | 1615 (21.03%) | 1045 (64.71%)*** | 4138 (24.92%) |

| Home/Other | 2167 (34.29%) | 20 (0.92%)*** | 1169 (24.43%) | 0*** | 785 (10.22%) | 0 | 3293 (19.83%) |

| Medical Indication for Caesarean Delivery a | |||||||

| Preeclampsia/Eclampsia | 2233 (34.80%) | 359 (16.08%) | 1192 (24.48%) | 302 (33.26%) | 3601 (46.46%) | 1345 (41.40%)** | 6441 (36.74%) |

| Malpresentation | 165 (2.57%) | 71 (43.03%)*** | 299 (6.14%) | 158 (64.49%)*** | 893 (11.52%) | 606 (72.40%)*** | 1216 (6.94%) |

| Any | 2285 (35.61%) | 390 (17.07%) | 1327 (27.25%) | 385 (37.52%) | 3981 (51.37%) | 1619 (44.87%)*** | 7529 (39.65%) |

Medical indication variables were only available from 1992 – 1994, 2002 – 2004, and 2007 – 2012.

Chi-square and t-test results are shown in shaded columns.

Significant differences in chi-square and t-tests by delivery type are denoted by:

p<0.05,

p≤0.01,

p≤0.001

Throughout the whole time period, 50.36% of women gave birth in public centers, 4.88% at social security centers, 24.92% at private centers, and 19.83% at home. Over time, women utilized public centers more and private centers less for their L&D care, and fewer women gave birth at home. In addition, women reported attending an increasing number of prenatal care appointments and reported generally attending prenatal care earlier in their pregnancies over the course of the two decades.

Sociodemographics

Descriptive statistics were calculated for women from each of the three datasets as well as for the combined sample as a whole [Table 1]. Overall, the average age of these women was 29.42 years. The vast majority of women (94.43%) in the total sample spoke Spanish as their primary language, and 56.85% of the women sampled lived in urban areas.

Risk Factors for Caesarean Delivery

In each dataset, age, ethnicity, language, urbanicity, education, income, parity, month of first primary care, number of prenatal care visits, and institution of L&D care were significantly associated with caesarean delivery [Table 1]. Malpresentation of the baby was consistently significantly associated with mode of delivery in each dataset. Preeclampsia/eclampsia was only significantly associated with mode of delivery in the 2012 dataset, and any medical indication was only significantly associated with mode of delivery in the 1994 and 2012 data.

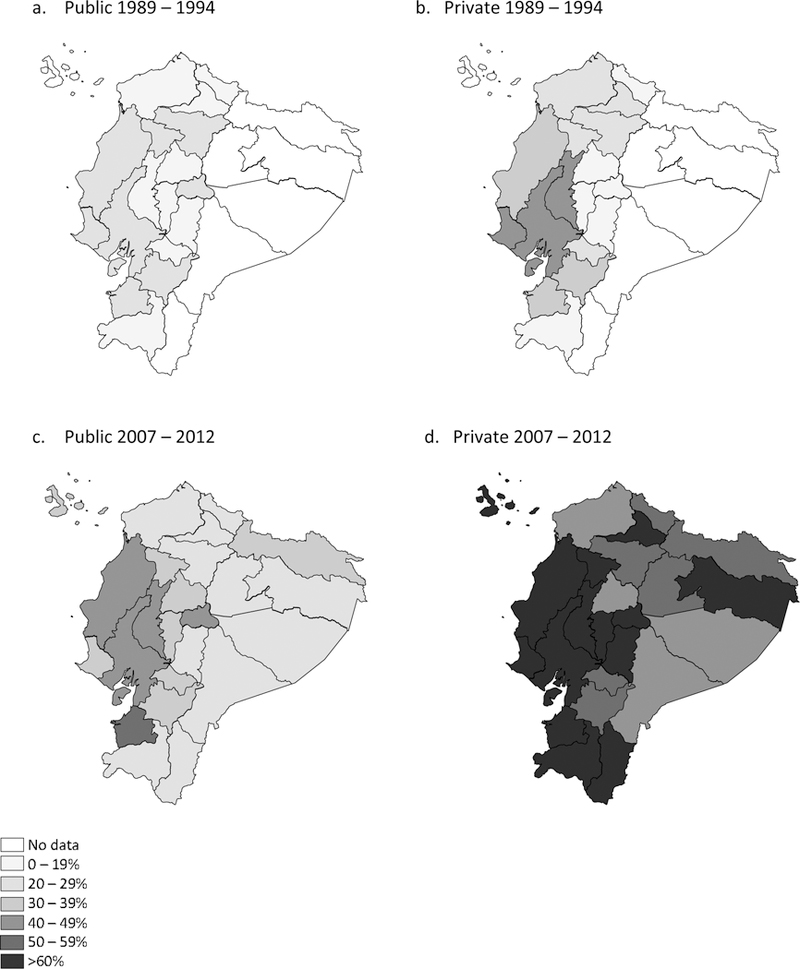

Region

Mapping caesarean delivery outcomes by L&D care institution with the 1994 and the 2012 data showed not only that region is highly predictive of caesarean delivery, but also that the prevalence of caesarean delivery has increased most dramatically in private care centers [Figure 1]. Rates of caesarean delivery have remained highest in provinces along the coast of Ecuador and lowest in the highlands and in the Amazon basin. Further, while caesarean deliveries are far less common from 1989 – 1994, rates are nonetheless high. The overall the rate of caesarean delivery in private centers during this time period is 32.75% [Figure 1b], while in public centers it is 19.23% [Figure 1a].

Figure 1.

Caesarean delivery by province and L&D care

Maps of data from 2007 to 2012 [Figures 1c, 1d] show that L&D care institution is a major predictor of caesarean delivery during this period. In many provinces, the rate of caesarean delivery in private centers is above 60% [Figure 1d]. Overall during this time period, 30.08% of births in public centers were by caesarean [Figure 1c], and 64.73% of births in private care were by caesarean [Figure 1d].

Logistic Regression

The full sample in the logistic regression model included 10,729 women who gave birth from 1992 – 1994, 2002 – 2004, or 2007 – 2012. After adjustment for covariates, models showed that births in social security institutions had the highest odds of caesarean delivery (aOR 2.01 [95% CI 1.14, 3.56]), followed by births in private institutions (1.77 [1.22, 2.56]), compared to births in public institutions [Table 2]. The model is adjusted for all of the covariates listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios for risk of caesarean delivery

| Characteristic | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| L&D Institution | |

| Public (Reference) | 1.0 |

| Social Security | 2.01 [1.14, 3.56]* |

| Private | 1.77 [1.22, 2.56]** |

| Region | |

| Urban (Reference) | 1.0 |

| Rural | 0.75 [0.68, 0.83]*** |

| Age, years | 1.05 [1.04, 1.06]*** |

| Parity | 0.84 [0.81, 0.88]*** |

| Language | |

| Spanish (Reference) | 1.0 |

| Indigenous | 0.55 [0.41, 0.75]*** |

| Education | |

| None (Reference) | 1.0 |

| Primary | 0.91 [0.59, 1.40] |

| Secondary | 1.03 [0.67, 1.59] |

| Superior/ Postgrad | 1.36 [0.87, 2.12] |

| First Prenatal Care Visit Month | 0.96 [0.94, 0.99]** |

| Number of Prenatal Care Visits | 1.02 [1.01, 1.03]*** |

| Medical Indications | |

| Preeclampsia/Eclampsia | 1.14 [1.04, 1.24]** |

| Fetal Malpresentation | 4.52 [3.93, 5.20]*** |

| Year | |

| 1992 (Reference) | 1.0 |

| 1993 | 0.89 [0.62, 1.26] |

| 1994 | 1.27 [0.85, 1.90] |

| 2002 | 1.79 [1.25, 2.57]** |

| 2003 | 1.46 [1.04, 2.06]* |

| 2004 | 1.21 [0.82, 1.69] |

| 2007 | 1.55 [0.96, 2.49] |

| 2008 | 1.74 [1.26, 2.40]*** |

| 2009 | 1.44 [1.06, 1.97]* |

| 2010 | 1.49 [1.10, 2.02]** |

| 2011 | 1.75 [1.30, 2.35]*** |

| 2012 | 2.02 [1.49, 2.72]*** |

| Year * L&D Institution | |

| 1993*Social Security | 0.91 [0.41, 2.01] |

| 1994*Social Security | 0.79 [0.31, 2.01] |

| 2002*Social Security | 0.84 [0.34, 2.11] |

| 2003*Social Security | 1.65 [0.55, 4.90] |

| 2004*Social Security | 0.79 [0.20, 3.03] |

| 2007*Social Security | 0.95 [0.24, 3.77] |

| 2008*Social Security | 1.57 [0.55, 4.49] |

| 2009*Social Security | 0.98 [0.42, 2.28] |

| 2010*Social Security | 1.17 [0.53, 2.62] |

| 2011*Social Security | 1.03 [0.51, 2.08] |

| 2012*Social Security | 1.13 [0.54, 2.37] |

| 1993*Private | 1.24 [0.75, 2.05] |

| 1994*Private | 0.95 [0.53, 1.70] |

| 2002*Private | 1.04 [0.62, 1.74] |

| 2003*Private | 1.34 [0.81, 2.22] |

| 2004*Private | 1.53 [0.87, 2.67] |

| 2007*Private | 1.23 [0.56, 2.71] |

| 2008*Private | 1.70 [1.04, 2.77]* |

| 2009*Private | 2.24 [1.40, 3.59]*** |

| 2010*Private | 2.06 [1.30, 3.27]** |

| 2011*Private | 1.99 [1.26, 3.14]** |

| 2012*Private | 2.22 [1.38, 3.58]*** |

denotes a p-value of <0.05,

denotes a p-value of ≤0.01,

denotes a p-value of ≤0.001

The is adjusted for all variables listed in the table

Age, Parity, First prenatal care visit month, and Number of prenatal care visits are analyzed continuously, and the adjusted odds ratio presented represents an incremental change in risk of caesarean delivery for each year of age, child born, month later of first prenatal care visit, and for each additional visit, respectively.

Rural women and indigenous-language speaking women are significantly less likely to deliver by caesarean than urban women and women whose primary language is Spanish. Women who had their first prenatal care visits later were less likely to deliver by caesarean. Conversely, older women and women who attended more prenatal care visits were more likely to deliver by caesarean. Last, women who reported preeclampsia/eclampsia (1.14 [1.04, 1.24]) and whose babies were badly positioned for labor (4.52 [3.93, 5.20]) had significantly greater risk of caesarean delivery.

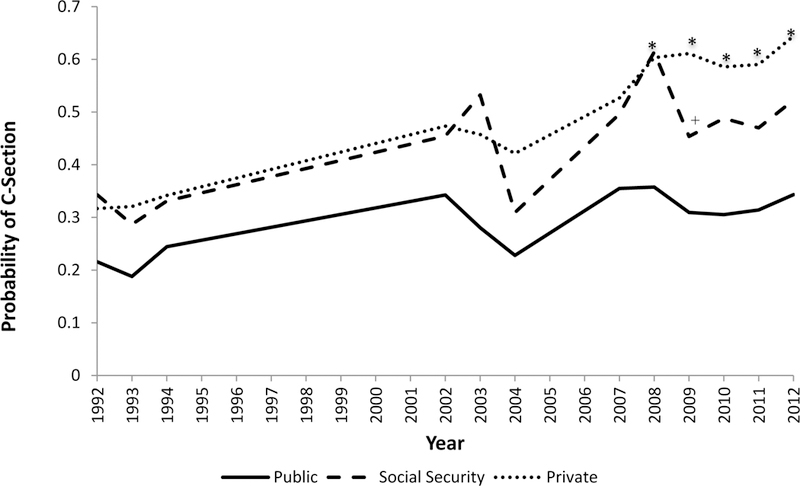

Based on this model, we derived predicted probabilities of delivering by caesarean, which showed that the predicted probability of caesarean delivery is higher in private and social security institutions than in public institutions even after controlling for maternal characteristics [Figure 2]. While the predicted probabilities of caesarean delivery in social security institutions are high, less than 10% of the population sought L&D care in these centers. From 2008 through 2012, the predicted probability of delivering by caesarean in private centers is significantly higher than that of delivering by caesarean in public centers. The predicted probability of delivering by caesarean in private centers did not significantly differ from that of delivering by caesarean in social security institutions in any year. Further, the predicted probability of delivering by caesarean in social security L&D institutions was significantly higher than that of delivering by caesarean in public institutions only in 2009.

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of caesarean delivery by L&D care and year

*denotes p-value of <0.05, where the predicted probability of caesarean delivery in private institutions is significantly higher than the predicted probability of caesarean delivery in public institutions.

+ denotes p-value of <0.05, where the predicted probability of caesarean delivery in social security institutions is significantly higher than the predicted probability of caesarean delivery in public institutions.

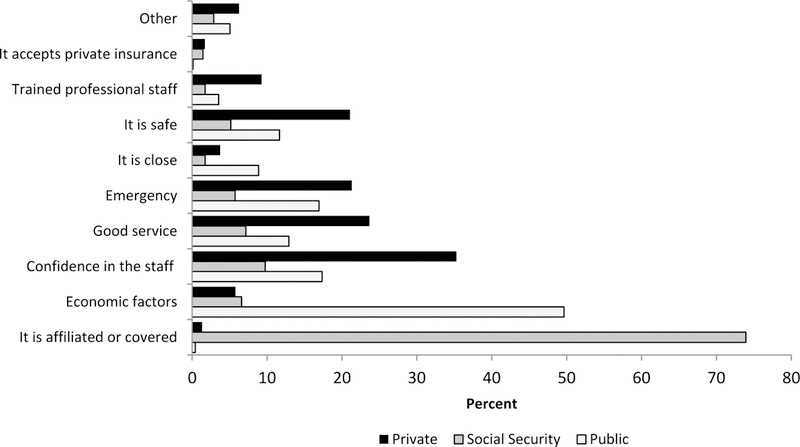

Women’s Motivations

Using a subset of women who gave birth from 2007 – 2012 (n= 7,791), we examined women’s motivations for selecting their L&D institution. Women could select more than one motivation. Results show that the primary consideration for giving birth in a public institution was economic at 49.7% [Figure 3]. The primary reason for giving birth in a social security institution (73.93%) was that it was covered by insurance, and the primary motivation for giving birth in a private institution was confidence in the staff (35.28%). Following confidence in the staff, the institution’s good service (23.66%), the fact that the patient was experiencing an emergency (21.31%), and the institution’s safety (21.07%) were reported motives.

Figure 3.

Motivation for selection of L&D institution by L&D institution

Discussion

Health Care System

While risk of caesarean delivery is increasing in all types of L&D institutions, our results show that it has been and remains highest in private institutions and lowest in public institutions. Our findings are similar to those of a WHO study that found that throughout Latin America, caesarean delivery is most common in private centers, followed by social security centers, and least common in public institutions.4

Over the past three decades, Ecuador’s health care system has transitioned from primarily private to increasingly public. In the 1980s, public funding on health was cut so that citizens would rely on the free-market’s promise of low-cost, high-quality health care,11 but throughout the 1990s, private care remained expensive and inaccessible for the majority of the population.14 Since 2000, the Ministry of Health has increased spending, and in 2008 Ecuador passed legislature guaranteeing free healthcare to all. Since then, despite increased budgets, public institutions have had difficulty keeping up with the increased patient demand, while the private sector, which includes for-profit institutions like hospitals and clinics as well as nonprofit organizations like non-governmental organizations (NGOs), has expanded. The private sector has drawn medical staff from public institutions through higher salaries, and it has maintained paying patients through the promise of high-quality and efficient healthcare.14

Given our results, which show the predicted probability of caesarean delivery to be higher in private L&D centers than public L&D centers, the economic benefits of caesarean delivery for private institutions must be considered. One study in Brazil found that caesarean deliveries increase profits due to decreased birthing time, the subsequent ability of the hospital to attend more births, and the higher cost of caesarean delivery.15 In another study on perinatal health in Latin America, the WHO found that 58% of sampled private institutions reported economic incentives for caesarean delivery, while only 24% of public institutions did.4 As public care has become increasingly accessible within Ecuador, private centers may be encouraging caesarean delivery to increase revenue in a competitive health care system in which they are losing clients to public care.

It is also possible that private centers’ wealthier, more urban patients are pushing private doctors to perform caesarean deliveries. Whether a woman’s request for caesarean is motivated by her status, her understanding of caesarean deliveries as safe, or her fear of vaginal delivery, a private center that needs to satisfy paying customers may be more likely to acquiesce a patient’s request for a caesarean delivery. Similarly, due to the unpredictability of birthing, private institutions may be more likely to resort to caesarean delivery in instances of prolonged labor even with no medical indication. Private institutions may feel a particularly strong obligation to provide caesarean deliveries to satisfy patients’ desires for caesarean deliveries or to avoid litigation in the case of poor maternal or neonatal outcomes of a vaginal delivery.15

Sociodemographics and Motivations

Our analyses show that caesarean deliveries among urban, highly educated, and white women contribute most to the high national caesarean delivery rate. Rural, less educated, and indigenous women have the lowest rates of caesarean delivery. Maps show that for both public and private institutions, the rate of caesarean delivery is highest along the coast of Ecuador, which has a generally wealthier population than those in the highlands and the Amazon. Notably, the private centers in the Northern Amazonian region of Ecuador now have a caesarean delivery rate over 60%, despite their remoteness and the lower SES of the region. These higher rates may be due to fear of vaginal delivery in a remote region and a likely small number of private health centers, which limits heterogeneity of practice. They may also be due to the fact that some private health centers in this region may be referral sites for cases of pregnancy complications, which could warrant a caesarean delivery.

Sociodemographic characteristics may influence the care that a woman seeks in a variety of ways. Some have suggested that wealthier women may choose private care, where they are more likely to deliver by caesarean.15 In fact, in Brazil, caesarean deliveries are so closely associated with wealth that researchers have found that delivering by caesarean increases a woman’s status through the implication that she has the resources to afford private health care or that she is delivering a large and healthy infant.15 Wealthier or urban women may also request a caesarean delivery if they desire greater or and medicalization for their delivery.15,16 The shift toward a “culture of caesareans”15 has been at least partially embraced by both patients and doctors in Latin America, who increasingly view caesarean deliveries as modern, predictable, and safe.4,15,17,18

Women in more remote regions or those who feel strong ties to indigenous communities may not be as likely to desire a highly medicalized pregnancy and may instead favor traditional options. One study found that prenatal care services in Ecuador are often independent from (and in conflict with) traditional belief systems, causing barriers to care, particularly among indigenous women who rely primarily on midwifery.19

Financial, geographic, or cultural factors may continue to pose barriers to the type of care that women seek. Our analysis of women’s motivations for selecting the institution of their delivery demonstrate that those who gave birth in public and social security institutions were primarily motivated by financial factors, indicating an economic constraint, and perhaps a barrier in access to the care that they desire. In contrast, women who gave birth in a private institution most often cited their confidence in the staff at the institution, indicating that the choice was made based on perception of the quality and type of care.

These results are consistent with prior findings that private care services remain financially inaccessible for most of the Ecuadorian population and that public health services are failing to deliver high-quality care.11 Our results support the claim that financial concerns prevent many individuals from accessing the kind of quality care that they may desire. Nonetheless, perceived improved quality of care through private care unnecessarily increases risk for delivering by caesarean, and therefore may not be an improvement in care.

Medical Predictors

Women’s risk of delivering by caesarean also varied by medical predictors, including month at first prenatal care visit, total number of prenatal care visits, and medical indications for caesarean delivery. Women who attended prenatal care earlier and who attended more visits overall were more likely to deliver by caesarean. These results could be explained by the fact that women with high-risk pregnancies, who are more likely to deliver by caesarean, are attending prenatal care sooner and attending more visits overall. However, rates of medical indication for caesarean delivery have not undergone a steady increase over time, which is inconsistent with increasing rates of caesarean delivery, suggesting that the increase in caesarean delivery in Ecuador is in excess.

Conclusions

Our analyses use three iterations of large-scale nationally-representative datasets to assess how L&D care has shaped risk of caesarean delivery alongside major healthcare reform in Ecuador over the past two decades. The robust datasets are nationally relevant and mitigate selection bias. We find that, while Ecuador has recently adopted universal healthcare coverage, private health care providers wield great influence on Ecuador’s health care system. This study illuminates the pathways to caesarean delivery in an under-studied setting, and its results may have implications of the rising rate of caesarean delivery globally in low- and middle-income countries.

Despite these strengths, this study has several limitations. First, data on pregnancy and birth complications come from maternal report. Consequently, medical indications were constructed through reports of complications and not from medical report of indication, which limits our understanding of which caesarean deliveries were performed in excess. Second, while literature on caesarean delivery is growing for other Latin American countries, research in Ecuador remains limited. Since there has been little qualitative data on caesarean delivery in Ecuador, it is difficult to say if the patterns that have shaped caesarean delivery elsewhere in South America are salient in Ecuador. Qualitative research is needed to better understand decision-making around caesarean deliveries within Ecuador.

To address the excess of caesarean deliveries, particularly in private centers, policies for stricter diagnosis of the medical indication for caesarean delivery and for preventing incentives for caesarean delivery may be needed. Further, policies should be supported with strategies to improve both provider and patient education about the risk and benefits of modes of delivery. To address barriers in access to care, high quality public health care should be made available in even the most rural settings. To better tailor recommendations for improvement, future projects should aim to better understand the “culture of caesareans” in Ecuador and analyze how decision-making regarding caesarean delivery is made within families and health institutions.

Acknowledgements

This research received support from the Population Research Training grant (T32 HD007168) and the Population Research Infrastructure Program (P2C HD050924) awarded to the Carolina Population Center at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Contributor Information

Johanna R. Jahnke, Department of Anthropology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a predoctoral trainee at the Carolina Population Center..

Kelly M. Houck, Department of Anthropology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill..

Margaret E. Bentley, Carla Smith Chamblee Distinguished Professor of Global Nutrition, Associate Dean for Global Health at the Gillings School of Global Public Health, and Associate Director of the Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill as well as a Fellow at the Carolina Population Center.

Amanda L. Thompson, Department of Anthropology and an Associate Professor in the Department of Nutrition at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill as well as a Fellow at the Carolina Population Center..

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freire WB, Belmont P, Rivas-Marinño G, et al. Tomo II Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición. Salud Sexual y Reproductiva. ENSANUT-ECU 2012; Quito; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Runmei M, Lao Terence T, Yonghu S, et al. Practice audits to reduce caesareans in a tertiary referral hospital in south-western China. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:488–494. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.093369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villar J, Valladares E, Wojdyla D, et al. Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: the 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Lancet. 2006;367:1819–1829. doi: 10.1016/S0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boutsikou T, Malamitsi-Puchner A. Caesarean section: Impact on mother and child. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:1518–1522. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silver RM. Implications of the first cesarean: perinatal and future reproductive health and subsequent cesareans, placentation issues, uterine rupture risk, morbidity, and mortality. Semin Perinatol. 2012;36:315–323. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blustein J, Attina T, Liu M, et al. Association of caesarean delivery with child adiposity from age 6 weeks to 15 years. Int J Obes. 2013;37(7):900–906. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho CE, Norman M. Cesarean section and development of the immune system in the offspring. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(4):249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyde MJ, Modi N. The long-term effects of birth by caesarean section: The case for a randomised controlled trial. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88:943–949. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merenstein DJ, Gatti ME, Mays DM. The association of mode of delivery and common childhood illnesses. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011. doi: 10.1177/0009922811410875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasch D, Bywater K. Health promotion in Ecuador: A solution for a failing system. Health (Irvine Calif). 2014;6:916–925. doi: 10.4236/health.2014.610115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The World Bank. World Development Indicators. https://data.worldbank.org/country/ecuador?display=default. Published 2018.

- 13.Muller CJ, Maclehose RF . Estimating predicted probabilities from logistic regression: Different methods correspond to different target populations. Int J Epidemiol. 2014:962–970. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Paepe P, Tapia RE, Santacruz EA, Unger J-P. Ecuador’s silent health reform. Int J Heal Serv. 2012;42(2):219–233. doi: 10.2190/HS.42.2.e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Béhague DP. Beyond the simple economics of Cesarean Section birthing: women’s resistance to social inequality. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2002;26:473–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chacham AS, Helena I, Perpétuo O. The incidence of caesarean deliveries in Belo Horizonte, Brazil: Social and economic determinants. Reprod Health Matters. 1998;6(11):115–121. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenwick J, Staff L, Gamble J, Creedy DK, Bayes S. Why do women request caesarean section in a normal, healthy first pregnancy? Midwifery. 2010;26:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tully KP, Ball HL. Maternal accounts of their breast-feeding intent and early challenges after caesarean childbirth. Midwifery. 2014;20:712–719. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torri MC. Choosing between traditional medicine and allopathy during pregnancy: health practices in prenatal and reproductive health care in Ecuador. J Health Manag. 2013;15(3):397–413. doi: 10.1177/0972063413492036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]