Abstract

Access to continuous water supply is key for improving health and economic outcomes in rural areas of low- and middle-income countries, but the factors associated with continuous water access in these areas have not been well characterized. We surveyed 4786 households for evidence of technical, financial, institutional, social, and environmental predictors of rural water service continuity (WSC), defined as the percentage of the year that water is available from a source. Multiply imputed fractional logistic regression models that account for the survey design were used to assess operational risks to WSC for piped supply, tube wells, boreholes, springs, dug wells, and surface water for the rural populations of Bangladesh, Pakistan, Ethiopia, and Mozambique. Multivariable regressions indicated that households using multiple water sources were associated with lower WSC in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Mozambique. However, the possibility must be considered that households may use more than one water source because services are intermittent. Water scarcity and drought were largely unassociated with WSC, suggesting that service interruptions may not be primarily due to physical water resource constraints. Consistent findings across countries may have broader relevance for meeting established targets for service availability as well as human health.

Keywords: intermittent supply, continuous supply, rural water supply, service availability, low- and middle-income countries

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

While access to water services has increased globally over recent decades,1 an estimated 925 million people are served by piped-to-premise water supplies that are intermittent.2 Pressure loss in an intermittent piped system can result in groundwater infiltration, surface water infiltration, and biofilm growth that can contaminate water supplies.3,4 Non-networked sources can also supply water intermittently. When water services of any type are interrupted, households may resort to using less water, storing water, and/or using less accessible and potentially contaminated water sources.5,6 Risk assessment models suggest that the annual health benefits of a safe drinking water source can be eliminated in just a few days of compromised service.7

Cross-sectional surveys spanning four decades show that a high percentage of water sources in low- and middle-income countries do not supply water at the time of data collection, especially in rural areas.8,9,18–20,10–17 Studies have identified various factors associated with reduced water source functionality (whether the water source was operational on the day of observation),8,9,21–26 reliability (whether the water source had previously broken down),25 and continuity (whether the water source provided service 24 hours per day).27,28 The problem with these data is that such binary outcomes do not capture the temporal variability of water services and offer poor indicators to assess the cumulative risk over time posed by intermittent water services.29 Best available estimates suggest that intermittency from piped-to-premise water supplies alone may account for 109 000 diarrheal disability adjusted life years and 1560 deaths globally each year,2 but the predictors of intermittent supply are poorly understood.

The aim of this study was to assess possible technical, financial, institutional, social, and environmental predictors of water service continuity (WSC), defined as the percentage of the year that water is available to households, of household taps, tube wells/boreholes, dug wells, springs, and surface water for the rural populations of four low and lower-middle income countries: Bangladesh, Pakistan, Ethiopia, and Mozambique. Specifically, because interrupted services can result in households using multiple water sources, this study conceptualizes rural water service delivery through overall user experience instead of water sources individually. Factors associated with WSC may reflect rural water service issues such as insufficient cost recovery,30 seasonal service,31 poor maintenance,32 and using multiple sources.33 Similar findings across countries may point to consistent underlying causes of intermittency and may guide the development of strategies to achieve global targets for water service availability.

Materials and Methods

Data Collection

In 2014, we collected survey data on water services that were representative of the rural populations of four countries—Bangladesh, Pakistan, Ethiopia, and Mozambique. These countries are located within sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, where an estimated 57 and 14% of people are without access to a “basic water source” as defined by the United Nations (i.e., an improved water source not exceeding a 30-minute round trip collection time including queueing), respectively.34 Under our supervision, field teams administered surveys to communities and households within those communities in rural Bangladesh, Pakistan, Ethiopia, and Mozambique (Table S1). The household survey collected data on publicly and privately available water services as perceived by households, while the community surveys assessed water services at the community level. Survey data from all countries were imported into Stata S/E 15.0,35 merged, and cleaned.

To supplement survey data, raster data of surface water and groundwater consumption and availability were obtained from Mekonnen and Hoekstra.36 Water scarcity indices indicate the ratio of the... blue water footprint to the blue water availability, where blue water is freshwater and includes groundwater and surface water. A water scarcity index below 1.0 indicates low scarcity, 1.0 to 1.5 signifies moderate scarcity, 1.5 to 2.0 equates to significant scarcity, and above 2.0 is severe scarcity.36 The raster model has high spatial resolution (30 × 30 arc-min), high duration and frequency of estimates (the index was calculated monthly over the 10-year period of 1996 to 2015), and includes environmental flow requirements. Using Global Positioning System coordinates, we matched water sources to their respective water scarcity index in QGIS and then imported data into Stata S/E 15.0.37

Sampling Strategy

For survey data, we included only rural areas in the sampling frame, adopting the definition of “rural” used by census authorities within each country. We estimated the required sample size for the questionnaires using EpiInfo 7.2.38 We aimed for a target sample size of 1200 households in 60 clusters (20 households in each cluster) to allow for non-response and to increase power. Further information about sample size calculations and sampling areas is included only in the Supporting Information.

We used a three-stage sampling design for household and community survey data collection. In the first stage, we used a probability proportional to size method39 to randomly select about 60 rural census enumeration areas in each country. Probability of selection for enumeration areas was based on the number of households within each enumeration area, which was provided by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, the Central Statistics Agency of Ethiopia, and the National Institute of Statistics in Mozambique. In the second stage, we segmented enumeration areas with more than 300 households into smaller clusters (i.e., communities) and randomly selected one of the clusters with equal probability. The third stage involved systematic random sampling of 20 households within each cluster with equal probability. We derived household design weights by multiplying the inverse probability-of-selection for the three stages. All public water sources in the sampled clusters were included in the community interview.

Field teams conducted household and community surveys over 14 weeks in 2014 (February-March in Pakistan, May-June in Bangladesh, July-September in Mozambique, and October-December in Ethiopia). In all, teams collected data from 4786 households in 242 census enumeration areas. More information about the study design and methods can be found in the Supporting Information and in previous reports.40–45

Survey Design

The survey included community and household questionnaires. We first interviewed a group of 8 to 12 key community members with the purpose of enumerating publicly available water sources within the community and to allocate them identification codes. These codes aided in referencing public water sources identified in the household survey. Data incorporated from the community surveys were: the number of community water sources, community rurality index, and if the community experienced a drought or flood in the past year.

For the household survey, the preferred respondent was an adult female within the household who we identified as most knowledgeable of the household composition and water management. If this person was not available at the time of the interview, we interviewed any adult (≥ 18 years) from the household with sufficient knowledge of household water use and willingness to participate. Household survey data incorporated into our study included a listing of all unimproved and improved water sources and types used by the household; data used to derive household wealth quintiles; if the household regularly paid tariffs to use water sources; if the household financially contributed to the construction of water sources; household perception of appearance, taste, safety, odor, and accessibility of water from sources; round trip travel time to water sources; number of water sources used by the household; whether the household owned the water source; if the household had to leave the plot to use the water source; and if the household used the source for drinking. Both household and community surveys were cross-sectional, yet they asked respondents to self-report time-varying data.

Outcome and Predictor Variables

We defined the outcome variable for this analysis, WSC, as the percentage of the year that water of any quality is available to a household from a water source. We calculated WSC using

| (1) |

where WSH represents the typical hours per day of service (out of 24), WSD is the usual days per month of service (out of 30), and WSM denotes the typical months per year of service (out of 12). The unit of analysis in this study was household-water source combinations, such that WSC was calculated for each water source utilized by a household.

Based on the literature, we hypothesized that the following predictor variables in the dataset might have effects on WSC: water source type;10,46 household wealth quintile;6 regular tariff payment;9,24,47 financial contributions to water source construction;48 the number of community water sources;21,24 community rurality index;6 water scarcity;49–51 drought in the past year;51 flood in the past year;46,49 water quality (appearance, taste, perception of safety, and odor);9,52 water source accessibility;10 round-trip travel time to the water source;53 number of water sources used by the household;10,48 and ownership of the water source.10 To determine wealth quintiles, we estimated wealth indices from key indicators related to household wealth (i.e., characteristics of the dwelling and asset ownership) using principal component analysis and previously established methods.54,55 For the number of community water sources, only improved water sources were summed to represent available protected sources. We derived the community rurality index, which summarizes the extent to which a household is rurally located or removed from development, by tallying specific amenities within the community. We gave each amenity an equivalent weight: a primary school, secondary school, health center, hospital, post office, bank, market, bus stop, mobile phone network, local NGO office, and local government office. The rurality index is a three-level categorical variable, where communities with fewer than three amenities have a high rurality index and those with more than seven have a low rurality index. Survey questions, further variable definitions, and the rationale for including independent variables are available in the Supporting Information.

Multiple Imputation

We handled missing data using multiple imputation by chained equations.56–58 All variables listed in the Outcome and Predictor Variables section were included in imputation models with the exception of predictors missing more than 20% of data, which were excluded prior to imputation. When fewer than 20% of observations were missing, we used multiple imputation by chained equations to impute missing data by generating 50 imputation datasets. We included two auxiliary variables in imputation models: if the household had to leave the plot to use the water source and if they used the source for drinking. Imputation models used logistic regression for binary variables (regular tariff payment, financial contributions to water source construction, drought, flood, water appearance, taste, odor, safety in drinking, water source accessibility, ownership of the water source), and truncated regression58 (WSC and community rurality index) or predictive mean matching59,60 (number of community water sources, round trip travel time, and water scarcity index) for continuous variables.

Descriptive Analysis and Survey Estimation

As some households used more than one water source, the number of survey observations exceeded the number of sampled households. We assigned household-level survey weights for each household-water source combination, and those weights were incorporated using survey estimation techniques.61 We then conducted descriptive data analysis to determine the following estimates for the rural population of each country: the proportions of household-water source combinations of each water source type; WSC of each water source type; and water services across hourly, daily, monthly, and yearly time-scales. Estimates are representative of all water sources used by households (i.e., household-water source combinations) in rural populations. As multiple households may rely on the same water source, estimates are not representative of all independent water sources in rural populations.

Fractional Logistic Regression

After categorizing water source types with less than 10% of the sample size as “other” water sources, we tested all variables for multi-collinearity using variance inflation factors. Then, we used survey estimation fractional logistic regression62 to provide estimates of operational risks to water service by testing for associations between independent variables and WSC. Fractional logistic regression is a quasi-maximum-likelihood estimation method that assumes the conditional mean WSC follows a logit distribution bounded (0,1), while allowing for actual values of WSC to exist on the range [0,1].62

Multivariable regression models for each country included all variables listed in the Outcome and Predictor Variables section in the regression models, except for those with greater than 20% missingness. Due to the exploratory nature of this work, we calculated odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) and highlighted predictors associated with WSC with nominal significance (p < 0.05). To account for the risk of Type I error inherent in multiple hypothesis testing, we calculated false discovery rate q-values (Table S2) independently for each country using qqvalue63 in Stata with the Holm multiple-test method.64 We also conducted univariable regressions, which are located in the Supporting Information (Figures S1–S4).

Odds ratios indicate the direction of association between a predictor and an outcome in our nonlinear models: an OR significantly greater than 1 indicates the predictor is associated with greater WSC, while an OR significantly less than 1 indicates that the predictor is associated with lower WSC. To concretize these abstract associations into tangible scenarios, we calculated the predicted WSC when changing an independent variable and holding other variables to reference values (specified in the Results).

Results

Descriptive Data

A total of 2111 (Bangladesh), 1671 (Pakistan), 2230 (Ethiopia), and 1322 (Mozambique) household-water source combinations were observed and incorporated into the analysis. Tube wells/boreholes were the most common water source in Bangladesh (53.2%, CI = 50.0−56.4%) and Pakistan (50.6%, CI = 41.7−59.5%), in comparison to surface water in Ethiopia (47.2%, CI = 38.5−55.9%) and dug wells in Mozambique (46.2%, CI = 33.7−58.8%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Estimates of the proportion of household-water source combinations of each water source type for the rural population of each country.

| Bangladesh | Pakistan | Ethiopia | Mozambique | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (%) | CI* (%) | Cases (%) | CI (%) | Cases (%) | CI (%) | Cases (%) | CI (%) | |

| Water source type | ||||||||

| Tube well / borehole | 53.2 | 50.0–56.4 | 50.6 | 41.7–59.5 | 14.1 | 7.5–20.7 | 25.2 | 16.0–34.5 |

| Piped supply | 3.5 | 1.6–5.4 | 40.1 | 29.9–50.3 | 7.3 | 2.0–12.5 | 3.1 | 0.4–5.8 |

| Dug well | 0.4 | 0.01–0.8 | 1.8 | −0.08–3.6 | 3.1 | 0.7–5.6 | 46.2 | 33.7–58.8 |

| Spring | - | - | - | - | 28.1 | 18.1–38.0 | 1.9 | −1.1–4.9 |

| Surface water | 39.7 | 36.5–42.8 | 6.1 | 0.1–12.1 | 47.2 | 38.5–55.9 | 23.4 | 12.2–34.6 |

| Other | 3.2 | 1.3–5.0 | 1.5 | 0.4–2.5 | 0.2 | −0.09–0.5 | 0.1 | −0.05–0.3 |

Estimated total number of household-water source combinations in the rural populations: Bangladesh (49 587 000), Pakistan (15 269 000), Ethiopia (27 686 000), and Mozambique (3 443 000).

CI – 95% confidence intervals

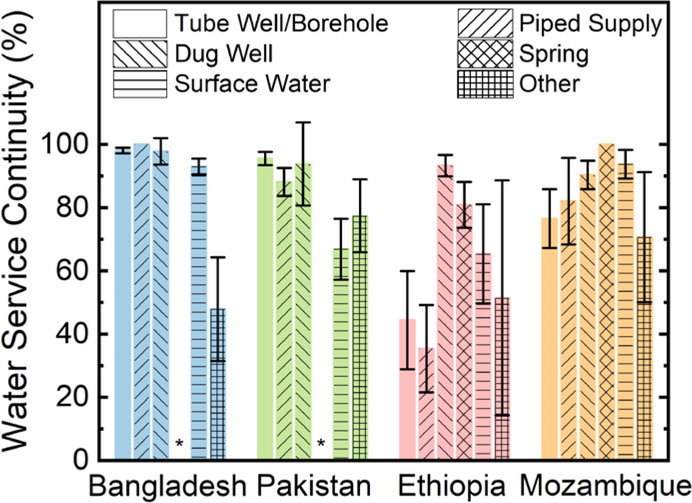

In Ethiopia and Mozambique, tube wells/boreholes, piped supply, and other water sources had the lowest WSC (Figure 1). In Ethiopia, WSC was less than 50% for both tube wells/boreholes (44.4%, CI = 28.8−60.0%) and piped supply (35.4%, CI = 21.6−49.2%). Piped supply and tube wells/boreholes were on average the least interrupted sources in Bangladesh and Pakistan, respectively.

Figure 1.

Estimates of water service continuity (WSC) for household-water source combinations for the rural population of each country (with 95% confidence intervals –). A WSC of 100% indicates uninterrupted water supply over a year, while a WSC of 0% suggests no water supply over a year. An asterisk (*) indicates no observed cases.

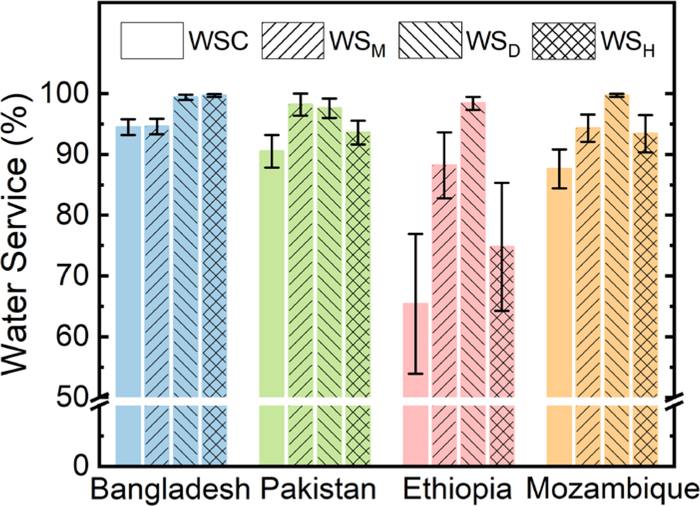

The time-scale of water supply cycles varied, as shown by stratifying WSC by the typical hours per day of service, days per month of service, and months per year of service (Figure 2). Water sources in all countries had high levels of water service on a day-to-day basis, as all countries had typical service for over 97.5% of the days per month. Less than 24-hour service during the day was the most common form of intermittency in Pakistan (93.6%, CI = 91.7−95.6%), Ethiopia (74.8%, CI = 64.3−85.4%), and Mozambique (93.4%, CI = 90.4−96.5%). On the other hand, inactive months during the year was the leading type of water source intermittency in Bangladesh (94.7%, CI = 93.4−96.0%).

Figure 2.

Water service (WS) estimates (with 95% confidence intervals –) across different time-scales for the rural population of each country. WSM denotes the typical months per year of service, WSD is the usual days per month of service, and WSH represents the typical hours per day of service. WSC is the composite variable that combines WSM, WSD, and WSH constituents in accordance with Equation 1. A WS of 100% indicates non-interrupted water supply over the given time-scale, while a WS of 0% suggests no water supply over that time-scale.

The percentage of missing data for each variable (in order of Bangladesh, Pakistan, Ethiopia, and Mozambique) were: regular tariff payment (< 0.1, 0.6, 0.0, 0.0%); financial contribution to water source construction (0.8, 0.5, 0.2, 0.4%); number of community water sources (4.3, 8.8, 21.4, 37.7%); community rurality index (1.1, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0%); water scarcity index (10.1, 6.9, 3.3, 7.8%); flood and drought in the past year (1.1, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0%); appearance, taste, and odor of water (43.9, 23.1, 37.4, 3.1%); perception of safety in drinking water (43.8, 23.4, 37.5, 3.3%); water source accessibility (64.8, 75.0, 2.6, 6.5%), round trip travel time to the water source (0.0, 0.0, 0.0, < 0.1%), household ownership of the water source (0.4, 4.8, 0.2, < 0.1%). Further descriptive data are available in the Supporting Information (Table S3–S6).

Bangladesh

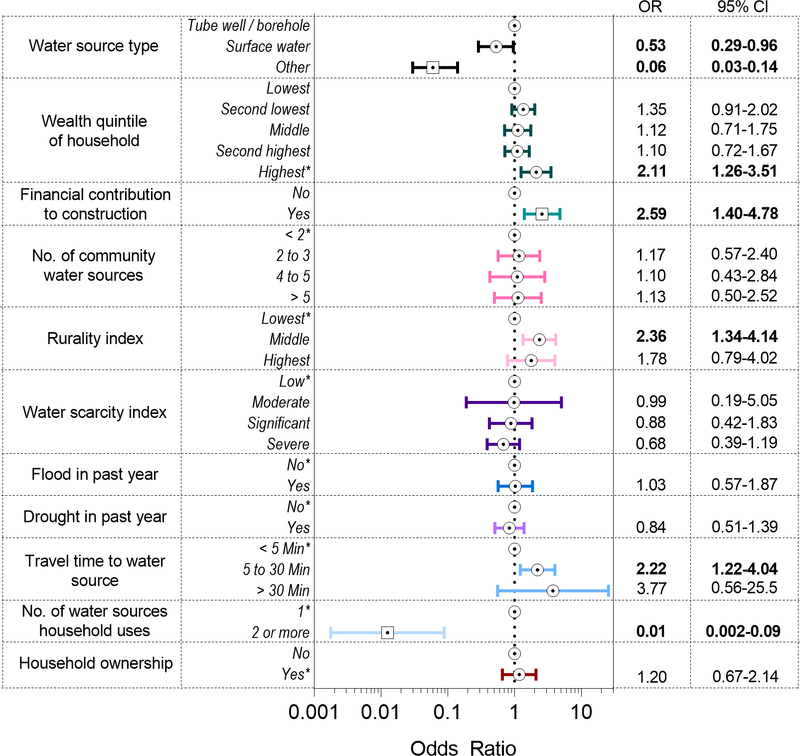

Multivariable regression analysis revealed that WSC was significantly (p < 0.05) lower in Bangladesh for surface water (q = 0.54) and other water sources (q < 0.001) compared to tube wells/boreholes (Figure 3). WSC was also significantly lower when households used multiple water sources instead of relying on a single source (q = 0.001). Holding other variables at reference values (Figure 3), the regression model predicted households using multiple water sources to have water sources with WSC of 99% (CI = 97−99%) for tube wells/boreholes, 98% (CI = 95−99%) for surface water, and 83% (CI = 66−93%) for other water sources but predicted a WSC of ~100% for households relying on one water source. WSC significantly increased when households financially contributed to water source construction (q = 0.06) and were in the highest wealth quintile (q = 0.09). WSC was also significantly higher for households living in communities with an intermediate rurality index instead of a low rurality index (q = 0.06), and traveled between 5 and 30 minutes roundtrip to fetch water compared with under 5 minutes (q = 0.16). However, there were no significant differences between WSC and households falling in the lowest and highest rurality index or households traveling less than 5 minutes and more than 30 minutes roundtrip for water. Environmental predictors—water scarcity index, flood, or drought—were not significantly associated with WSC. In the univariable regression, privately owned water sources had significantly higher WSC (Figure S1), but no association was found in multivariable analysis.

Figure 3.

Multivariable fractional logistic regression for Bangladesh indicating the odds ratios (OR) of water service continuity (WSC). All listed predictors were included in the regression model. An OR of greater than 1 indicates the factor is associated with increased WSC, while an OR less than 1 signifies an association with reduced WSC. Predictors with significant p-values are bold (p < 0.05), while significant q-values (q < 0.05) have a boxed data point. Bounds around data points denote 95% confidence intervals (CI). Reference values used for WSC predictions are noted by an asterisk (*).

Pakistan

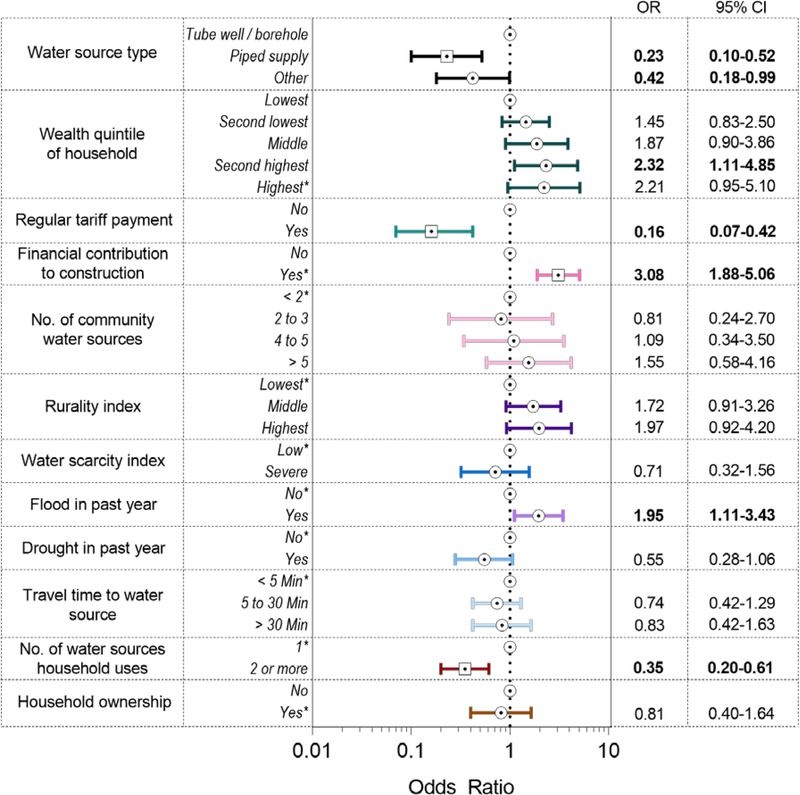

In Pakistan, WSC was significantly (p < 0.05) lower for piped supply (q = 0.01) and other water sources (q = 0.67) compared to tube wells/boreholes (Figure 4). WSC was also significantly lower when tariffs were regularly paid by households (q = 0.01) and when households used multiple water sources (q = 0.01). On the other hand, WSC was significantly higher for households in the second highest wealth quintile compared to the lowest quintile (q = 0.40) and for households that financially contributed to water source construction (q = 0.001). When households financially contributed to water source construction, while holding other variables at reference values (Figure 4), the model predicted higher WSC for tube wells/boreholes (WSC = 95%, CI = 75−99%), piped supply (WSC = 80%, CI = 47−95%), and other water sources (WSC = 88%, CI = 51−98%) compared to when financial contributions were not made for tube wells/boreholes (WSC = 85%, CI = 51−97%), piped supply (WSC = 57%, CI = 23−85%), and other water sources (WSC = 70%, CI = 28−94%). WSC was also significantly higher for households within communities where a flood occurred within the past year (q = 0.33). Household-owned water sources had significantly higher WSC in univariable analysis (Figure S2), but no significant difference was found in multivariable analysis.

Figure 4.

Multivariable fractional logistic regression for Pakistan indicating the odds ratios (OR) of water service continuity (WSC). All listed predictors were included in the regression model. An OR of greater than 1 indicates the factor is associated with increased WSC, while an OR less than 1 signifies an association with reduced WSC. Predictors with significant p-values are bold (p < 0.05), while significant q-values (q < 0.05) have a boxed data point. Bounds around data points denote 95% confidence intervals (CI). Reference values used for WSC predictions are noted by an asterisk (*).

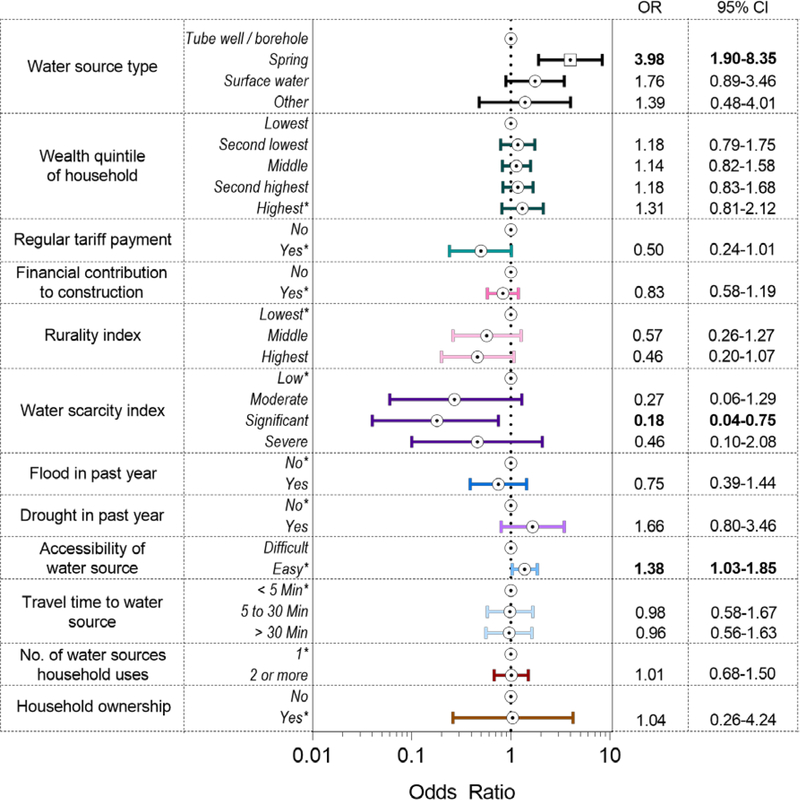

Ethiopia

In Ethiopia, WSC was significantly (p < 0.05) lower for households in regions with significant water scarcity indices (q = 0.41) but not for other water scarcity categories in the multivariable analysis (Figure 5). Springs (q = 0.01) were associated with significantly higher WSC compared to tube wells/boreholes. The model predicted WSC for springs (WSC = 91%, CI = 54−99%), surface water (WSC = 82%, CI = 36−97%), and other water sources (WSC = 79%, CI = 42−95%) to be higher than tube wells/boreholes (WSC = 73%, CI = 24−96%) when holding other variables at reference values (Figure 5). Easily accessible water sources were also linked with higher WSC (q = 0.67). Neither the use of multiple water sources nor water source ownership were associated with significantly higher WSC in multivariable or univariable regressions (Figure S3).

Figure 5.

Multivariable fractional logistic regression for Ethiopia indicating the odds ratios (OR) of water service continuity (WSC). All listed predictors were included in the regression model. An OR of greater than 1 indicates the factor is associated with increased WSC, while an OR less than 1 signifies an association with reduced WSC. Predictors with significant p-values are bold (p < 0.05), while significant q-values (q < 0.05) have a boxed data point. Bounds around data points denote 95% confidence intervals (CI). Reference values used for WSC predictions are noted by an asterisk (*).

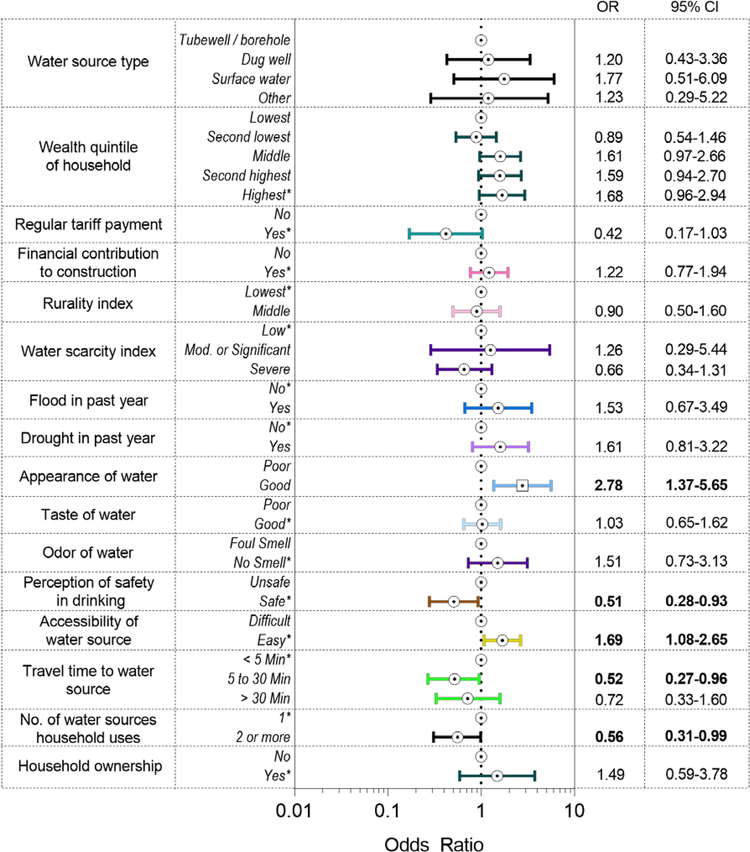

Mozambique

In Mozambique, WSC was significantly (p < 0.05) lower when households perceived the water source to be safe for drinking (q = 0.61) and households had a roundtrip travel time to the water source between 5 and 30 minutes (compared to less than 5 minutes) (q = 0.75) (Figure 6). WSC was also significantly lower when households used multiple water sources (q = 0.85). WSC was significantly higher when households perceived the water source to be easily accessible (q = 0.48) and the water to have good appearance (q = 0.13). Holding other variables at reference values (Figure 6), the model predicted sources with good water appearance to have higher WSC for tube wells/boreholes (WCS = 97%, CI = 88−99%), dug wells (WCS = 98%, CI = 90−100%), surface water (WCS = 99%, CI = 93−100%), and other water sources (WCS = 98%, CI = 92−99%) compared to tube wells/boreholes (WCS = 93%, CI = 77−98%), dug wells (WCS = 94%, CI = 80−99%), surface water (WCS = 96%, CI = 85−99%), and other water sources (WCS = 94%, CI = 85−98%) with poor water appearance. No measured environmental factors (i.e., water scarcity index, flood, or drought) were significant predictors of WSC in the multivariable analysis. Household ownership was not significantly associated with WSC in multivariable or univariable regressions (Figure S4).

Figure 6.

Multivariable fractional logistic regression for Mozambique indicating the odds ratios (OR) of water service continuity (WSC). All listed predictors were included in the regression model. An OR of greater than 1 indicates the factor is associated with increased WSC, while an OR less than 1 signifies an association with reduced WSC. Predictors with significant p-values are bold (p < 0.05), while significant q-values (q < 0.05) have a boxed data point. Bounds around data points denote 95% confidence intervals (CI). Reference values used for WSC predictions are noted by an asterisk (*).

Discussion

Water services in low- and middle-income countries may face technical, financial, institutional, social, or environmental constraints (e.g., drought) that can cause water sources to become intermittent.5 Target 6.1 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) specifies that one required component of safely managed drinking water is that “household respondents either report having access to sufficient water when needed, or having water available at least 50% of the time (i.e., at least 12 hours per day or 4 days per week).”65 However, even a small interruption to service can expose households to unsafe water as they change to distant alternative sources that may be unfit for drinking water use, or as they use an existing piped system at risk of contamination due to reduced pressure.66 Provision of uninterrupted services is then necessary (though not sufficient) to protect water quality and public health. WSC as defined here focuses on any intermittency of service and, therefore, is distinct from Target 6.1 in the SDGs.

We analyzed water services of the rural populations of Bangladesh, Pakistan, Ethiopia, and Mozambique and found WSC to be variable across countries and water source types. Though the results presented here should not be given a causal interpretation – directionality of association cannot be inferred from cross-sectional analysis – we found significant associations between households’ use of multiple water sources and lower WSC in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Mozambique. Another study also discovered a similar negative association between households having a reliable alternative source (a source within 1 km that has water during the dry season) and a working primary water source, which they explained by households with several sources placing less demand for a working primary source.21 Therefore, it could be that water sources are intermittent because households have access to multiple sources. Access to multiple sources could limit the need for a single source to supply all water needs and potentially suppress community investment in the primary source. An additional explanation for the identified association is the inverse: households use multiple water sources to access reliable supply because their preferred sources are intermittent, as a coping strategy to maintain consistent access for different times and/or needs.4,67

While data from the United Nations Joint Monitoring Programme show disparities in water access across wealth quintiles,34 to our knowledge, no previous study has demonstrated a direct connection between household wealth and water service intermittency. Households in the highest wealth quintile in Bangladesh as well as the second highest wealth quintile in Pakistan had significantly higher WSC compared to the lowest quintile. This suggests that households in the lowest quintiles of Bangladesh and Pakistan are not only less likely to access water free from contamination,6 but these households are also less likely to receive continuous water supply.

In Bangladesh and Pakistan, households that financially supported construction of water sources were more likely to have sources with higher WSC. This finding is consistent with previous literature noting a link between communal feelings of ownership and sustained water services.68 Financial contributions to water source construction may be an expression of household demand for water as well.21 The association between good water appearance and WSC in Mozambique can be explained by greater water quality increasing household demand for water in the form of willingness to pay.52 Physical water source ownership by households (an indicator of excludability) was not significantly associated with WSC in multivariable analyses for any country. While a previous work found an association between private ownership and higher handpump functionality, it did not control for socioeconomic characteristics.25 Our univariable analysis for Bangladesh and Pakistan also showed household ownership to be related to higher WSC, but an association was not apparent after moderating for household wealth quintile and other factors in multivariable regressions. The lack of association between water source ownership and WSC is of particular interest amidst the consideration of self-supply as a service delivery model.69 Further investigation is required to explore the relationship between household ownership and continuity of supply after controlling for household wealth.

Several other counterintuitive findings from this study have possible explanations. Regular tariff payment was associated with significantly lower WSC in Pakistan, but it may be that water sources with tariffs are more likely to experience supply interruptions, such as from planned maintenance interventions or if water sources require operator supervision to collect tariffs per use at the source. Our proxy for “safe water” only accounted for user perception and not physicochemical properties of water supply (microbial and chemical composition data were not available) and may have produced a spurious association between safe water and lower WSC in Mozambique. In Bangladesh a 5- to 30-minute travel time was associated with higher WSC than a less than 5-minute travel time to the water source, but this may be due to households electing to use distant water sources because they proved most reliable. Lastly, the associations between greater WSC and the intermediate rurality index in Bangladesh was also unexpected. It may be that more economically developed areas (low rurality index) require more water and, therefore, place more stress on sources during dry months, while less developed areas (higher rurality index) may have more secure water access and not be subjected to this problem. This inference is supported by the fact that intermittency in Bangladesh was primarily on a month-to-month basis.

With the exception of significant water scarcity in Ethiopia, no water scarcity or drought predictors were apparently associated with WSC after controlling for other factors. This finding supports previous literature suggesting that physical water resource constraints are not the sole cause of interrupted service.70 However, even if physical water scarcity plays a small role in household water security,51 water scarcity can emerge as a product of management, socio-economic, or political factors.49,70,71 Also unexpectedly, tariff payments and private ownership of water sources did not contribute to higher WSC. Rather, households using one water source had the highest WSC in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Mozambique, either because those households express greater demand on sustained performance or because households using multiple water sources are doing so because their preferred sources are intermittent. Generally, few consistent trends emerged, perhaps due to contextual differences between countries and water source types, suggesting that service intermittency may be difficult to attribute to any ubiquitous set of operational factors.

Limitations

There are several limitations in the survey design, data analysis, and interpretation. With the cross-sectional design of the survey, causal inference is not possible. We collected surveys at different times of the year for each country without considering seasonal climate variations, which impedes cross-country comparability. As WSC is likely to vary over time and households, self-reported outcome data based on their usual experience, we expect substantial recall error. Other error in WSC data could have arisen from households irregularly using water sources. Reported WSC data are also not representative of all water services available but rather services that households use, which may be the most continuous sources.

Regarding the analysis, households sharing water sources could have resulted in unmeasured clustering, which was only controlled for using Huber-White robust standard errors. As a composite variable, WSC equivalently weights hourly, daily, and monthly components of intermittency. A water source operating diurnally (e.g., 12 hours per day, 30 days per month, and 12 months per year) yields the same WSC as one functioning seasonally (e.g., 24 hours per day, 30 days per month, and 6 months per year), although the former may be a better service than the latter. Predictors are also likely to interact with each component of WSC differently and the incorporation of several water source types may have masked water source-specific predictors. We conducted regression analyses that included water source-predictor interactions to evaluate water source-specific associations with WSC (Table S7–S8). Results were broadly consistent with the presented models, except in a few cases where we have accordingly deemphasized results. The potential predictors of WSC in the models are not exhaustive, nor can we rule out unmeasured confounding in this observational dataset. Concerning data interpretation, the presence of many hypotheses increases the risk of Type I error: apparent associations may be due to chance.

Country-specific results are likely not generalizable to other rural settings, although common factors among countries may illuminate aspects of rural water service delivery that may be true on a broader scale. Future research should address how identified predictors are related to providing continuous water services for specific water sources on different time-scales in rural regions of low- and middle-income countries. In this way, elucidating the mechanisms that underlie the predictors of WSC can inform policy responses that better service delivery approaches and maximize health and economic outcomes for rural communities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the UK Department for International Development through the VFM-WASH Consortium led by Oxford Policy Management (PO 6148). The MPhil studentship for R.M.D. was financially supported by a Gates Cambridge Scholarship. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.K. government or Gates Cambridge Trust. The authors also acknowledge the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship awarded to R.M.D. M.O.G. was supported in part by funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (P30 ES019776).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Number of community and household surveys (Table S1), sampling strategy, rationale and definitions for variables, multivariable fractional logistic regression models q-values (Table S2), univariable fractional logistic regression models (Figure S1–S4), sample size and mean WSC for each predictor (Table S3), water service across different time-scales and stratified by water source type (Table S4), water service estimates across water source types (Table S5), water service estimates across different time-scales (Table S6), multivariable fractional logistic regression models with water source-predictor interactions (Table S7), multivariable linear regression models with water source-predictor interactions (Table S8).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- (1).WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme. Progress on Sanitation and Drinking Water: 2015 Update and MDG Assessment; 2015. 10.1007/s13398-014-0173-7.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Bivins AW; Sumner T; Kumpel E; Howard G; Cumming O; Ross I; Nelson K; Brown J Estimating Infection Risks and the Global Burden of Diarrheal Disease Attributable to Intermittent Water Supply Using QMRA. Environ. Sci. Technol 2017, 51 (13), 7542–7551. 10.1021/acs.est.7b01014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Coelho ST; James S; Sunna N; Abu Jaish A; Chatiia J Controlling Water Quality in Intermittent Supply Systems. Water Sci. Technol. Water Supply 2003, 3 (1–2), 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Shaheed A; Orgill J; Montgomery MA; Jeuland MA; Brown J Why “ Improved ” Water Sources Are Not Always Safe. Bull. World Health Organ. 2014, 92, 283–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kumpel E; Nelson KL Intermittent Water Supply: Prevalence, Practice, and Microbial Water Quality. Environ. Sci. Technol 2016, 50 (2), 542–553. 10.1021/acs.est.5b03973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).WHO/UNICEF. Safely Managed Drinking Water - Thematic Report on Drinking Water 2017; Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Hunter PR; Zmirou-Navier D; Hartemann P Estimating the Impact on Health of Poor Reliability of Drinking Water Interventions in Developing Countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407 (8), 2621–2624. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Cronk RD; Bartram J Factors Influencing Water System Functionality in Nigeria and Tanzania: A Regression and Bayesian Network Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol 2017, 51, 11336–11345. 10.1021/acs.est.7b03287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Foster T Predictors of Sustainability for Community-Managed Handpumps in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Uganda. Environ. Sci. Technol 2013, 47 (21), 12037–12046. 10.1021/es402086n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Harvey P; Reed R Rural Water Supply in Africa: Building Blocks for Handpump Sustainability; Water, Engineering and Development Centre: Leicestershire, U.K., 2004. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Adank M; Kumasi TC; Chimbar TL; Atengdem J; Agbemor BD; Dickinson N; Abbey E The State of Handpump Water Services in Ghana: Findings from Three Districts In 37th WEDC International Conference; Hanoi, Vietnam, 2014; pp 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- (12).McPherson HJ; McGarry MG User Participation and Implementation Strategies in Water and Sanitation Projects. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev 1987, 3 (1), 23–30. 10.1080/07900628708722330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Mwathunga E; MacDonald AM; Bonsor HC; Chavula G; Banda S; Mleta P; Jumbo S; Gwengweya G; Ward J; Lapworth D; Whaley L; Lark RM UPGro Hidden Crisis Research Consortium: Survey 1 Country Report – Malawi; 2017.

- (14).Owor M; MacDonald A; Bonsor H; Okullo J; Katusiime F; Alupo G; Berochan G; Tumusiime C; Lapworth D; Whaley L; Lark R UPGro Hidden Crisis Research Consortium: Survey 1 Country Report – Uganda; 2017.

- (15).Howe CW; Dixon JA Inefficiencies in Water Project Design and Operation in the Third World: An Economic Perspective. Water Resour. Res 1993, 29 (7), 1889–1894. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Cairncross S; Carruthers I; Curtis D; Feachem R; Bradley D; Baldwin G Evaluation for Village Water Supply Planning; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: West Sussex, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Foster T; Willetts J; Lane M; Thomson P; Katuva J; Hope R Risk Factors Associated with Rural Water Supply Failure: A 30-Year Retrospective Study of Handpumps on the South Coast of Kenya. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 626, 156–164. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Kebede S; MacDonald AM; Bonsor HC; Dessie N; Yehualaeshet T; Wolde G; Wilson P; Whaley L; Lark RM UPGro Hidden Crisis Research Consortium: Unravelling Past Failures for Future Success in Rural Water Supply. Survey 1 Results - Country Report Ethiopia; 2017.

- (19).Anscombe JR Consultancy Services: Quality Assurance of UNICEF Drilling Programmes for Boreholes in Malawi; Mangochi, Malawi, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Asian Development Bank. Impact of Rural Water Supply and Sanitation in Punjab, Pakistan; 2008.

- (21).Whittington D; Davis J; Prokopy L; Komives K; Thorsten R; Lukacs H; Bakalian A; Wakeman W How Well Is the Demand-Driven, Community Management Model for Rural Water Supply Systems Doing? Evidence from Bolivia, Peru and Ghana. Water Policy 2009, 11 (6), 696–718. 10.2166/wp.2009.310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Marks SJ; Komives K; Davis J Community Participation and Water Supply Sustainability: Evidence from Handpump Projects in Rural Ghana. J. Plan. Educ. Res 2014, 34 (3), 276–286. 10.1177/0739456X14527620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Alexander KT; Tesfaye Y; Dreibelbis R; Abaire B; Freeman MC Governance and Functionality of Community Water Schemes in Rural Ethiopia. Int. J. Public Health 2015, 60 (8), 977–986. 10.1007/s00038-015-0675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Fisher MB; Shields KF; Chan TU; Christensen E; Cronk RD; Leker H; Samani D; Apoya P; Lutz A; Bartram J Understanding Handpump Sustainability: Determinants of Rural Water Source Functionality in the Greater Afram Plains Region of Ghana. Water Resour. Res 2015, 51 (10), 8431–8449. 10.1002/2014WR016770.Received. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Foster T; Shantz A; Lala S; Willetts J Factors Associated with Operational Sustainability of Rural Water Supplies in Cambodia. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol 2018, 4 (10), 1577–1588. 10.1039/C8EW00087E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Anthonj C; Fleming L; Cronk R; Godfrey S; Ambelu A; Bevan J; Sozzi E; Bartram J Improving Monitoring and Water Point Functionality in Rural Ethiopia. Water 2018, 10 (11), 1591 10.3390/w10111591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Cronk R; Bartram J Identifying Opportunities to Improve Piped Water Continuity and Water System Monitoring in Honduras , Nicaragua , and Panama : Evidence from Bayesian Networks and Regression Analysis. J. Clean. Prod 2018, 196, 1–10. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kaminsky J; Kumpel E Dry Pipes: Associations between Utility Performance and Intermittent Piped Water Supply in Low and Middle Income Countries. Water 2018, 10 (8), 1032 10.3390/w10081032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Carter R; Ross I Beyond “Functionality” of Handpump-Supplied Rural Water Services in Developing Countries. Waterlines 2015, 35 (1), 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Harvey PA Cost Determination and Sustainable Financing for Rural Water Services in Sub-Saharan Africa. Water Policy 2007, 9 (4), 373–391. 10.2166/wp.2007.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Kelly E; Shields KF; Cronk R; Lee K; Behnke N; Klug T; Bartram J Seasonality, Water Use and Community Management of Water Systems in Rural Settings: Qualitative Evidence from Ghana, Kenya, and Zambia. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 629, 715–721. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Montgomery M. a.; Bartram J; Elimelech M Increasing Functional Sustainability of Water and Sanitation Supplies in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa. Environ. Eng. Sci 2009, 26 (5), 1017–1023. 10.1089/ees.2008.0388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Foster T; Willetts J Multiple Water Source Use in Rural Vanuatu: Are Water Users Choosing the Safest Option for Drinking? Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2018, 28 (6), 579–579. 10.1080/09603123.2018.1491953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).WHO/UNICEF. Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene; 2017.

- (35).StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Mekonnen M; Hoekstra A Four Billion People Experience Water Scarcity. Sci. Adv 2016, 2 (2), 1–6. 10.1126/sciadv.1500323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).QGIS. QGIS: A Free and Open Source Geographic Information System http://www.qgis.org/en/site/index.html (accessed Jul 8, 2017).

- (38).Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epi InfoTM https://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/index.html (accessed Aug 2, 2018).

- (39).Skinner CJ Probability Proportional to Size (PPS) Sampling In Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences; John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2006; pp 1–5. 10.1002/9781118445112.stat03346.pub2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Zaman R; Mujica A; Ross I; Incardona B; Burr P Improving VFM and Sustainability in WASH Programmes (VFM-WASH): Report of a WASH Sustainability Survey in Bangladesh; 2015.

- (41).Mujica A; Burr P; Zaman R; McIntosh K; Incardona B Improving VFM and Sustainability in WASH Programmes (VFM-WASH): Report of a WASH Sustainability Survey in Pakistan; 2015.

- (42).Tincani L; Ross I; Mujica A; McIntosh K; Burr P Improving VFM and Sustainability in WASH Programmes (VFM-WASH): Report of a WASH Sustainability Survey in Ethiopia; 2015.

- (43).Mujica A; Ross I; McIntosh K; Burr P; Zaman R Improving VFM and Sustainability in WASH Programmes (VFM-WASH): Report of a WASH Sustainability Survey in Mozambique; 2015.

- (44).Tincani L; Ross I; Zaman R; Burr P; Mujica A; Evans B Improving VFM and Sustainability in WASH Programmes (VFM-WASH): Regional Assessment of the Operational Sustainability of Wter and Sanitation Services in Sub-Saharan Africa; 2015.

- (45).Burr P; Ross I; Zaman R; Mujica A; Tincani L; White Z; Evans B Improving Value for Money and Sustainability in WASH Programmes (VFM-WASH): Regional Assessment of the Operational Sustainability of Water and Sanitation Services in South Asia; 2015.

- (46).Howard G; Katrina C; Pond K; Brookshaw A; Hossain R; Bartram J Securing 2020 Vision for 2030: Climate Change and Ensuring Resilience in Water and Sanitation Services. J. Water Clim. Chang 2010, 1, 2–16. 10.2166/wcc.2010.205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Carter R; Tyrrel S; Howsam P Strategies for Handpump Water Supply Programmes in Less-Developed Countries. J. Chart. Inst. Water Environ. Manag 1996, 10 (2), 130–136. 10.1111/j.1747-6593.1996.tb00022.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Parry-Jones S; Reed R; Skinner BH Sustainable Handpump Projects in Africa: A Literature Review; Water, Engineering and Development Centre: Leicestershire, U.K., 2001. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Simukonda K; Farmani R; Butler D Intermittent Water Supply Systems: Causal Factors, Problems and Solution Options. Urban Water J. 2018, 15 (5), 488–500. 10.1080/1573062X.2018.1483522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Totsuka N; Trifunovic N; Vairavamoorthy K Intermittent Urban Water Supply under Water Starving Situations In 30th WEDC International Conference; 2004; pp 505–512. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Calow RC; MacDonald AM; Nicol AL; Robins NS Ground Water Security and Drought in Africa: Linking Availability, Access, and Demand. Ground Water 2010, 48 (2), 246–256. 10.1111/j.1745-6584.2009.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Genius M; Tsagarakis KP Water Shortages and Implied Water Quality: A Contingent Valuation Study. Water Resour. Res 1999, 42 (12), W12407 10.1029/2005WR004833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Cairncross S The Benefits of Water Supply In Developing World Water II; Grosvenor Press: London, 1987; pp 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Rutstein SO; Johnson K DHS Comparative Reports 6: The DHS Wealth Index; 2004.

- (55).Filmer D; Pritchett L Estimating Wealth Effects without Expenditure Data-or Tears: An Application to Educational Enrollments in States of India. Demography 2001, 38 (1), 115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Azur MJ; Stuart EA; Frangakis C; Leaf PJ Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations: What Is It and How Does It Work? Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res 2012, 20 (1), 40–49. 10.1002/mpr.329.Multiple. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Buuren S. Van. Multiple Imputation of Discrete and Continuous. Stat. Methods Med. Res 2007, 16, 219–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Raghunathan TE; Lepkowski JM; Hoewyk J. Van; Solenberger P A Multivariate Technique for Multiply Imputing Missing Values Using a Sequence of Regression Models. Surv. Methodol 2001, 27 (1), 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Rubin DB Adjusted Weights and Multiple Imputations Statistical Matching Using File Concatenation With Adjusted Weights and Multiple Imputations. J. Bus. Econ. Stat 1986, 4 (1), 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- (60).Schenker N; Taylor JMG Partially Parametric Techniques for Multiple Imputation 1 Keywords : Comput. Stat. Data Anal 1996, 22, 425–446. [Google Scholar]

- (61).Kreuter F; Valliant R A Survey on Survey Statistics: What Is Done and Can Be Done in Stata. Stata J 2007, 7 (1), 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- (62).Papke LE; Wooldridge JM Econometric Methods for Fractional Response Variables with an Application to 401(k) Plan Participation Rates. J. Appl. Econom 1996, 11 (6), 619–632. 10.2307/2285155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Newson RB Frequentist Q-Values for Multiple Test Procedures. Stata J. 2010, 10 (4), 568–584. https://doi.org/TheStataJournal. [Google Scholar]

- (64).Holm S A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scand. J. Stat 1979, 6 (2), 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- (65).WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme. JMP Methodology: 2017 Update & SDG Baselines; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- (66).Kumpel E; Nelson KL Comparing Microbial Water Quality in an Intermittent and Continuous Piped Water Supply. Water Res. 2013, 47 (14), 5176–5188. 10.1016/j.watres.2013.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Shaheed A; Orgill J; Ratana C; Montgomery MA; Jeuland MA; Brown J Water Quality Risks of “improved” Water Sources: Evidence from Cambodia. Trop. Med. Int. Heal 2014, 19 (2), 186–194. 10.1111/tmi.12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Marks SJ; Komives K; Davis J Community Participation and Water Supply Sustainability. J. Plan. Educ. Res 2014, 34 (3), 276–286. 10.1177/0739456X14527620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Lockwood H; Smits S Supporting Rural Water Supply: Moving towards a Service Delivery Approach; Practical Action Publishing: Rugby, U.K., 2011. [Google Scholar]

- (70).Galaitsi SE; Russell R; Bishara A; Durant JL; Bogle J; Huber-Lee A Intermittent Domestic Water Supply: A Critical Review and Analysis of Causal-Consequential Pathways. Water (Switzerland) 2016, 8 (7), 274 10.3390/w8070274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Mehta L Whose Scarcity? Whose Property? The Case of Water in Western India. Land use policy 2007, 24 (4), 654–663. 10.1016/j.landusepol.2006.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.