This study investigates how pragmatic or explanatory cardiovascular randomized clinical trials are and if this has changed over time.

Key Points

Question

How pragmatic or explanatory are cardiovascular randomized clinical trials?

Findings

In this study of 616 cardiovascular randomized clinical trials, the level of pragmatism assessed by the Pragmatic Explanatory Continuum Index Summary–2 score increased moderately from 2000 to 2015. The increase occurred mainly in the eligibility, setting, and flexibility of intervention delivery, and primary end point domains of the trial design.

Meaning

Knowing more about current trials will help researchers in the design and delivery of cardiovascular trials that are required for broader application of the studied interventions.

Abstract

Importance

Pragmatic trials test interventions using designs that produce results that may be more applicable to the population in which the intervention will be eventually applied.

Objective

To investigate how pragmatic or explanatory cardiovascular (CV) randomized clinical trials (RCT) are, and if this has changed over time.

Data Source

Six major medical and CV journals, including New England Journal of Medicine, Lancet, JAMA, Circulation, European Heart Journal, and Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Study Selection

All CV-related RCTs published during 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015 were identified and included.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Included RCTs were assessed by 2 independent adjudicators with expertise in RCT and CV medicine.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The outcome measure was the level of pragmatism evaluated using the Pragmatic Explanatory Continuum Index Summary (PRECIS)–2 tool, which uses a 5-point ordinal scale (ranging from very pragmatic to very explanatory) across 9 domains of trial design, including eligibility, recruitment, setting, organization, intervention delivery, intervention adherence, follow-up, primary outcome, and analysis.

Results

Of 616 RCTs, the mean (SD) PRECIS-2 score was 3.26 (0.70). The level of pragmatism increased over time from a mean (SD) score of 3.07 (0.74) in 2000 to 3.46 (0.67) in 2015 (P < .001 for trend; Cohen d relative effect size, 0.56). The increase occurred mainly in the domains of eligibility, setting, intervention delivery, and primary end point. PRECIS-2 score was higher for neutral trials than those with positive results (P < .001) and in phase III/IV trials compared with phase I/II trials (P < .001) but similar between different sources of funding (public, industry, or both; P = .38). More pragmatic trials had more sites, larger sample sizes, longer follow-ups, and mortality as the primary end point.

Conclusions and Relevance

The level of pragmatism increased moderately over 2 decades of CV trials. Understanding the domains of current and future clinical trials will aid in the design and delivery of CV trials with broader application.

Introduction

Pragmatic trials have the primary goal of informing decision-makers (patients, clinicians, health care administrators, and policy makers) about the comparative effectiveness of biomedical and behavioral interventions by enrolling a population relevant to the study intervention and representative of the populations in which the intervention will be eventually applied and by streamlining and simplifying the trial-related procedures.1 They carry the potential to address some of the limitations of randomized clinical trials (RCT) such as the lack of external validity, high cost, and lengthy processes, often by streamlining the trial design and implementation. Since the concept of pragmatic and explanatory RCTs was first described in 1967,2,3 trialists have increasingly focused on how their trial design decisions can serve the intended purpose of their study. As a part of efforts to understand the nature of pragmatic RCTs,4,5 the Pragmatic Explanatory Continuum Index Summary (PRECIS) was developed to aid trialists make design decisions consistent with the intended purpose of a trial.4

The updated 2015 version of the PRECIS tool can be used to assess the trial decisions on 9 domains of trial design including the eligibility criteria, recruitment, setting, organization, the flexibility of intervention delivery, the flexibility of adherence to the intervention, follow-up, primary outcome, and primary analysis.6,7 Several studies tested the role of the PRECIS tool in the trial design phase and its ability to provide a framework to stimulate discussion among study investigators,5 and it has also been used retrospectively in evaluating RCTs.8,9,10,11,12 However, there is a paucity of data on how the landscape of cardiovascular (CV) RCTs have changed over the past few decades in terms of their placement on the pragmatic-explanatory continuum. The aim of this study was to investigate how pragmatic or explanatory CV RCTs are and to study the change in the domains and overall level of pragmatism in CV trials over the past 2 decades.

Methods

Cardiovascular RCTs that were published in 6 top-ranked medical and CV journals (based on impact factors) in 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015 were included in this study. Secondary analyses, substudies, follow-up studies, experimental and observational studies, commentaries, preliminary results, methodology articles, and those that were not CV related or not published in the mentioned time frame were excluded.

Search Strategy and Study Selection

The literature search and screening started in November 2016. Based on impact factors, 3 top-ranked medical journals (ie, New England Journal of Medicine, JAMA, and The Lancet), as well as 3 top-ranked CV journals (ie, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Circulation, European Heart Journal) were selected. As these CV journals publish the majority of CV RCTs, it was not feasible to assess all trials (4390 RCTs published between January 2000 and December 2015 using the search strategy; eTable 1 in the Supplement); therefore, we selected 4 full years of publications (ie, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015) spanning a period of change that may reflect trials started or completed in the 1990s through 2015. These years were selected to show the trend of change in the publication of pragmatic vs explanatory trials. We searched PubMed using the journal name, the medical subject heading term of “cardiovascular diseases,” and the publication type of “randomized controlled trial,” filtered to the publication date between January 1 and December 31 of each year. For example, we searched “Lancet”[jour] AND “Cardiovascular Diseases”[MeSH] AND “Randomized Controlled Trial” [Publication Type] AND (“2000/01/01”[PDAT]: “2000/12/31”[PDAT]).

Data Extraction

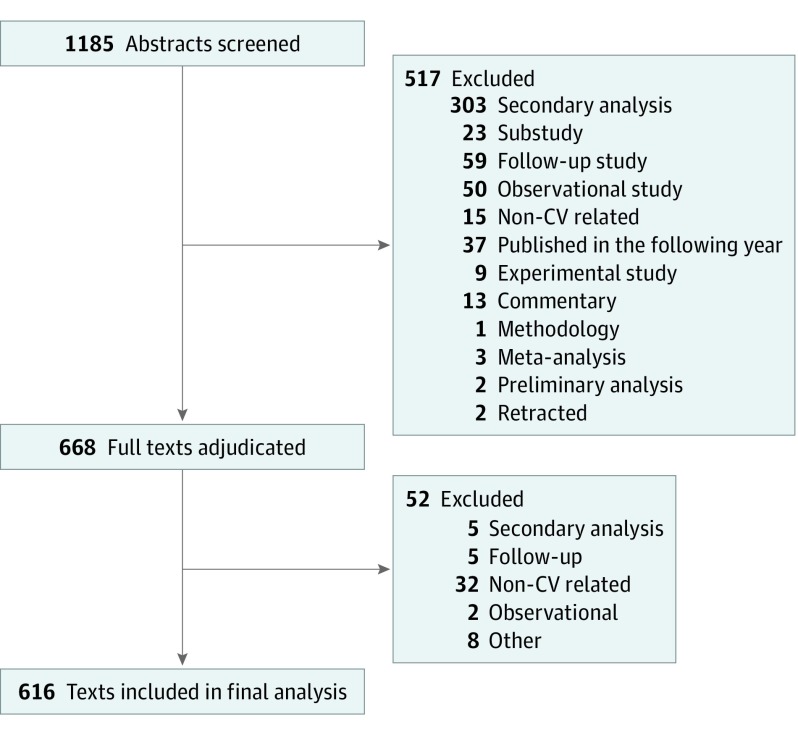

All 1185 abstracts were screened for the abovementioned eligibility criteria by 1 adjudicator (N.S.) to ensure they were clinical trials. After excluding 517 articles (Figure 1), the full text of the remaining 668 studies were assessed by 2 independent adjudicators with expertise in RCT and CV medicine (N.S., D.D., A.K.G., P.G., A.G., A.X.D., S.H., H.E.B., S.V., Z.K., and J.A.E.). All adjudicators were trained using the main relevant publications and the PRECIS toolkit from the precis-2.org website. Fifty-two additional studies were excluded in this phase for being identified as secondary analyses (n = 5), follow-up (n = 5), observational (n = 2), non-CV (n = 32), nonrandomized (n = 3), and experimental and pharmacokinetic (n = 2) studies, and for not being published in the study time frame (n = 3). Two adjudicators (N.S., D.D., A.K.G., P.G., A.G., A.X.D., S.H., H.E.B., S.V., Z.K., and J.A.E.) extracted information regarding study phase, sample size, numbers of involved sites and countries, follow-up duration, source of funding, trial design, and PRECIS-2 for each trial. In case of disagreement between adjudicators, the study was reviewed and arbitrated by the chair of the adjudication committee (J.A.E.). Trials were categorized based on the results to (1) neutral (negative), (2) negative for primary end point but positive for secondary end points, and (3) positive trials. Noninferiority trials that showed noninferiority for the primary end point was considered as positive trial in this analysis.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Literature Search .

CV indicates cardiovascular.

PRECIS-2 Tool

The PRECIS-2 tool was used to score the different domains of trial design for each trial.6 As demonstrated in eFigure 1 in the Supplement, the tool is a 9-spoked wheel, each spoke representing 1 of 9 domains of trial design (including eligibility criteria, recruitment, setting, organization, the flexibility of intervention delivery, the flexibility of adherence to the intervention, follow-up, primary outcome, and primary analysis). Trials with an explanatory approach got scores nearer to the hub, and those with pragmatic designs received scores closer to the rim of the wheel. A 5-point Likert scale was used to rate the level of pragmatism in each trial design domain: (1) very explanatory, (2) rather explanatory, (3) equally pragmatic/explanatory, (4) rather pragmatic, and (5) very pragmatic. Although there are other tools to evaluate the level of pragmatism in RCTs,13,14,15 the PRECIS-2 was used owing to its standardization and more comprehensive domains. Adjudicators scored trials separately on a web-based form provided through REDCap.16

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were summarized as frequency and percentages and compared between groups using the Pearson χ2 test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were summarized as mean and SD and compared applying the 1-way analysis of variance. For each domain in an RCT, the mean of the scores was taken as the PRECIS score. An RCT-specific summary PRECIS-2 score was calculated by calculating the mean of the scores over the 9 domains, referred to as mean PRECIS-2 score. In case of missing data on a specific domain, the mean PRECIS-2 score was based on the remaining domains with nonmissing score. The levels of pragmatism as quantified using the mean PRECIS-2 score were compared between different characteristics of RCTs using analysis of variance. The Cohen d was used to quantify the mean difference between groups relative to the variation.17 The changes or difference between groups can be interpreted as small, medium, or large, if the Cohen d was 0.2 to 0.49, 0.5 to 0.79, and 0.8 or more, respectively.17 Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to evaluate the degree of its linear relationship with continuous factors including sample size or the duration of follow-up in the trial. A simple linear regression was fitted to test for linear trend in the temporal change over the years of publication. The assumption of normality has been checked for the analyses and (log) transformations were applied when appropriate. The association between the type of trial (explanatory vs pragmatic), the internal validity and the trial result were evaluated using the χ2 test. A 2-sided P ≤ .05 was considered to be statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute), and R package version 3.5 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) was used to generate the figures.

Results

Trial Characteristics

There were 616 RCTs in total, with 172, 168, 137, and 139 studies, published in 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015, respectively. Among those, 423 studies (69.6%) involved more than 1 site, and 238 studies (38.8%) involved more than 1 country. Sources of funding were public only in 210 (39.3%), private/industry in 215 (40.3%), and both public and private/industry funding in 109 RCTs (20.4%). In 82 RCTs (13%), the funding was not reported.

Overall, 46 (7.5%) were crossover and 7 (1.1%) were cluster-randomized trials. Type of intervention was identified as pharmaceutical in 343 studies (55.7%), procedure and device studies in 193 (31.3%), and behavioral and health care system interventions in 80 studies (13%). Trial phase was not clear for 16 studies, but among the others, 13 (2.2%), 254 (42.3%), 212 (35.3%), and 121 (20.2%) studies were identified as phase I, II, III, and IV, respectively. Among phase II trials, 105 (41.3%) and 110 studies (43.3%) were further classified as IIa and IIb, respectively.

Among 616 RCTs, 380 (61.7%) were positive for their primary end point. Fifty-six trials (9.1%) were positive for secondary end points but did not achieve the primary end point, and 180 (29.2%) were identified as neutral or negative.

PRECIS-2 Scores

The PRECIS scores across 9 trial design domains as well as the summary PRECIS-2 score are presented in eTable 2 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement. The mean (SD) PRECIS-2 score was 3.26 (0.70) among 616 RCTs. The primary end point and statistical analysis domains had the lowest and highest PRECIS-2 scores, respectively.

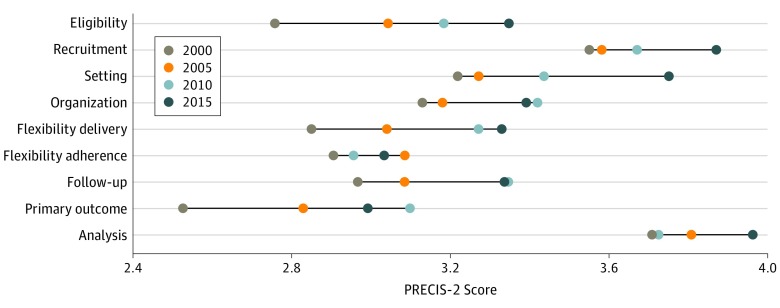

The level of pragmatism increased over time from a mean (SD) score of 3.07 (0.74) in 2000 to 3.46 (0.67) in 2015 (P < .001 for trend; Cohen d relative effect size, 0.56) (Table). The increase in pragmatism occurred mainly in the domains of eligibility, setting, intervention delivery, and primary end point (Figure 2).

Table. Study Characteristics and Level of Pragmatism.

| Factors | No. (%) | Score, Mean (SD) | Effect Size: Cohen d | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 616 (100) | 3.26 (0.70) | NA | NA |

| Year of publication | ||||

| 2000 | 172 (27.9) | 3.07 (0.74) | [Reference] | <.001a |

| 2005 | 168 (27.3) | 3.21 (0.64) | 0.21 | |

| 2010 | 137 (22.2) | 3.37 (0.66) | 0.43 | |

| 2015 | 139 (22.6) | 3.46 (0.67) | 0.56 | |

| Journal | ||||

| General medicine: NEJM/Lancet/JAMA | 224 (36.4) | 3.55 (0.58) | 0.67 | <.001 |

| Cardiology: EHJ/JACC/Circulation | 392 (63.6) | 3.10 (0.71) | [Reference] | |

| Trial phase | ||||

| I/II | 267 (44.5) | 2.97 (0.67) | [Reference] | <.001 |

| III/IV | 333 (55.5) | 3.49 (0.63) | 0.81 | |

| Crossover design | ||||

| No | 568 (92.5) | 3.31 (0.68) | [Reference] | <.001 |

| Yes | 46 (7.49) | 2.69 (0.59) | −0.92 | |

| Cluster-randomized | ||||

| No | 609 (98.9) | 3.26 (0.70) | [Reference] | .13 |

| Yes | 7 (1.14) | 3.66 (0.59) | 0.58 | |

| No. of arms | ||||

| 1-2 | 491 (79.7) | 3.31 (0.69) | [Reference] | <.001 |

| ≥3 | 125 (20.3) | 3.07 (0.68) | −0.34 | |

| Type of intervention | ||||

| Medicinal | 343 (55.7) | 3.14 (0.69) | [Reference] | <.001 |

| Procedure or device | 193 (31.3) | 3.38 (0.67) | 0.35 | |

| Behavioral or health system intervention | 80 (13.0) | 3.48 (0.67) | 0.49 | |

| Placebo-controlled | ||||

| No | 382 (62.0) | 3.36 (0.70) | [Reference] | <.001 |

| Yes | 234 (38.0) | 3.11 (0.66) | −0.37 | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel | ||||

| No | 312 (51.2) | 3.38 (0.69) | [Reference] | <.001 |

| Yes | 297 (48.8) | 3.14 (0.69) | −0.34 | |

| Blinding of outcome assessors | ||||

| No | 74 (12.7) | 3.41 (0.62) | [Reference] | .055 |

| Yes | 507 (87.3) | 3.25 (0.70) | −0.24 | |

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Mortality | 27 (4.38) | 4.05 (0.37) | 1.5 | <.001 |

| Mortality in a composite | 168 (27.3) | 3.63 (0.53) | 0.89 | |

| Other | 421 (68.3) | 3.07 (0.67) | [Reference] | |

| Central adjudication for primary end point | ||||

| No | 370 (60.1) | 3.11 (0.72) | [Reference] | <.001 |

| Yes | 246 (39.9) | 3.50 (0.59) | 0.59 | |

| Trial results | ||||

| Neutral (negative) | 180 (29.2) | 3.42 (0.66) | [Reference] | <.001 |

| Negative for primary but positive for secondary outcomes | 56 (9.09) | 3.38 (0.67) | 0.07 | |

| Positive for primary outcome | 380 (61.7) | 3.17 (0.70) | 0.36 | |

| Type of fundingb | ||||

| Public only | 210 (39.3) | 3.34 (0.71) | [Reference] | .38 |

| Private only | 215 (40.3) | 3.25 (0.69) | −0.13 | |

| Public and private | 109 (20.4) | 3.30 (0.60) | −0.07 |

Abbreviations: EHJ, European Heart Journal; JACC, Journal of the American College of Cardiology; NA, not applicable; NEJM, New England Journal of Medicine.

P value for trend test.

The private category includes both private and industry types of funding.

Figure 2. Change in Pragmatism Over Time Across Different Domains of Trial Design.

PRECIS indicates Pragmatic Explanatory Continuum Index Summary.

Although the level of pragmatism increased over time in both general medicine and CV journals, the general medicine category had a greater increase in the mean PRECIS-2 score, compared with CV journals (P for trend < .001). Randomized clinical trials that were published in general medicine journals had higher PRECIS-2 scores compared with those published in CV journals (Table; eFigure 3 in the Supplement). The domains of setting and primary outcome had the highest difference in pragmatism between trials published in general medicine and CV journals (eFigure 3D in the Supplement).

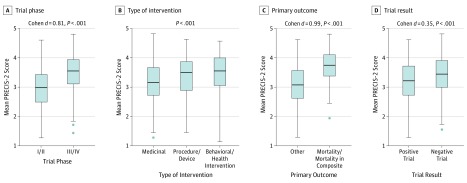

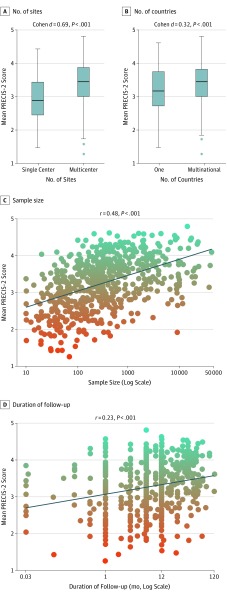

PRECIS-2 scores were higher for neutral trials than those with positive results (mean [SD], 3.42 [0.66] vs 3.17 [0.70]; P < .001) and in phase III/IV trials compared with phase I/II trials (mean [SD], 3.49 [0.63] vs 2.97 [0.67]; P < .001) (Figure 3). Furthermore, trials that involve more sites and countries, had larger sample sizes, had longer follow-ups, and those with mortality (alone or in a composite) as their primary end point were found to be more pragmatic (Table and Figure 4). There was no significant difference in the level of pragmatism between different sources of funding (public, private/industry, or both; mean [SD], 3.34 [0.71] vs 3.25 [0.69] vs 3.30 [0.60], respectively; P = .38). Crossover-designed RCTs had a significantly lower PRECIS-2 score compared with their counterparts (ie, parallel-designed RCTs) (mean [SD], 2.69 [0.59] vs 3.31 [0.68]; P < .001). Cluster-randomized trials had numerically higher PRECIS scores than RCTs with individual participant randomization, but the difference was not significant (mean [SD], 3.66 [0.59] vs 3.26 [0.70]; P = .13). Trials with behavioral and health care system interventions had higher (ie, more pragmatic) PRECIS-2 scores (mean [SD], 3.48 [0.67]) than RCTs with pharmaceutical (mean [SD], 3.14 [0.69]) and device or procedural (mean [SD], 3.38 [0.67]) interventions (P < .001). The PRECIS-2 scores as evaluated by the Cochrane risk of bias tool were not clinically meaningful (Cohen d effect size, 0.19; eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Figure 3. Level of Pragmatism by Trial Phase, Type of Intervention, Primary Outcome, and Trial Results.

PRECIS indicates Pragmatic Explanatory Continuum Index Summary.

Figure 4. Correlation Between PRECIS-2 Score With Sample Size, Number of Sites and Countries, and Follow-up Period.

PRECIS indicates Pragmatic Explanatory Continuum Index Summary.

Sensitivity Analysis

The results (increase in pragmatic RCTs from 2000 to 2015, difference between journal types, trial phases, types of intervention, study end points, larger sample sizes, more sites, and longer follow-up periods in pragmatic trials) remained consistent when pragmatic trials were defined as those with PRECIS-2 scores of 4 or more in at least 4 domains, provided the scores of the other domains were 3 or more18 (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Overall, 212 RCTs were identified as phase III, ranging from 46 phase III RCTs (21.7%) in 2000 to 62 trials (29.2%) in 2015. The PRECIS-2 score was similar between the years of study (mean [SD] score, 3.53 [0.56]) and the trend over time was nonsignificant (mean [SD], 3.45 [0.61], 3.57 [0.51], 3.60 [0.49], 3.51 [0.62] in 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015, respectively; P = .65). We also investigated phase III and IV trials combined, and the trend of change in pragmatism over time was not significant (mean [SD], 3.48 [0.64], 3.41 [0.65], 3.52 [0.58], and 3.56 [0.63] in 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015, respectively; P = .43).

Twenty-three (3.7%) and 19 studies (3.1%) were self-identified by authors as pragmatic and explanatory RCTs, respectively. The PRECIS-2 score was higher (mean [SD], 3.83 [0.78] vs 3.25 [0.68]) and lower (mean [SD], 2.92 [0.69] vs 3.25 [0.68]) in the self-identified pragmatic and explanatory trials, respectively, compared with those that did not mention pragmatism or the explanatory nature (eTable 5 and eFigure 4 in the Supplement). The self-identified pragmatic trials were more pragmatic than others in the primary outcome, setting, follow-up, and eligibility domains of the trial design (eTables 6 and 7 in the Supplement). The interadjudicator differences were not significant (eTable 8 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This study showed a moderate increase in the level of pragmatism in CV trials over 2 decades. The increase in pragmatism occurred mainly in the domains of eligibility, setting, intervention delivery, and primary end point. No RCT was completely explanatory or pragmatic in the trials sampled, consistent with the assumption of the developers of the PRECIS and PRECIS-2 tools, that trials are designed on a spectrum connecting these 2 extremes rather than dichotomous decisions of either pragmatic or explanatory nature.6

Pragmatic Trials and Guidelines

A 2019 study reviewed current recommendations of 2 major CV professional organizations’ practice guidelines and found that only 8.5% to 14.2% of recommendations were based on high-quality evidence, derived from multiple RCTs or meta-analyses of high-quality RCTs.19 Despite attempts to simplify and boost the conduct of RCTs, the evidence gap remains with only 11.6% and 8.5% of recommendations being backed by high-quality evidence in 2009 and 2019, respectively.19,20 To fill the abovementioned gap, streamlining the design of RCTs across all 9 domains is needed to focus on key questions in CV medicine. Unlike explanatory trials, which are aimed to maximize internal validity to demonstrate that the intervention is indeed the cause of increased/decreased outcome, the main focus in pragmatic trials is often maximizing external validity or generalizability of findings by mimicking the real-world setting and minimizing the alterations to usual processes of care while preserving internal validity.

Trial Characteristics and Degree of Pragmatism

Previous studies have suggested that most pragmatic trials that explore research questions that are important for optimizing the care for patients and health care systems are commonly funded by public or public-private partnerships.21 However, we did not find any difference in the level of pragmatism between different types of funding. There are fewer regulatory restrictions on interventions such as behavioral or health care system interventions. In our study, behavioral or health care system interventions had a higher level of pragmatism than medicinal or device/procedural interventions.

In the study of Dal-Ré et al,18 among 89 medicinal RCTs self-labeled as pragmatic or naturalistic, 36% had rather explanatory features and were placebo-controlled single-center or early phase trials. Conversely, in our study, trials that identified themselves as pragmatic had higher PRECIS-2 scores.

There was an increase in the level of pragmatism by increase in the phase of the RCTs. In principle, the pragmatic RCTs should investigate the effectiveness of already-marketed drugs rather than those still in the process of regulatory licensing, which requires strict protocols aiming maximized internal validity.18 Hence, it seems appropriate for the higher-phase trials (ie, phase III/IV) to be more pragmatic than phase I/II RCTs. We did not identify a trend of greater pragmatism over the 2 decades in phase III or IV trials; however, it is plausible that a reemphasis on pragmatic RCT has occurred in more recent years and this change will be evident in the coming years. Conversely, the large simple trials that lead to changes in practice in, for example, acute myocardial infarction, were also very pragmatic.

We used the PRECIS-2 tool for appraising trials to assess their placement in the pragmatic-explanatory continuum. Knowledge translation and dissemination efforts, including journal publications, may want to include the PRECIS-2 wheel assessment with the rationale behind the assigned scores in the same way journals require reporting the CONSORT checklist.22

Strengths and Limitations

There are strengths and limitations requiring mention. As we only included RCTs that were published in the general medicine and CV journals, the findings might not be generalizable to trials published in other journals and there is a possibility of publication bias. The assessment of all published trials in a 2-decade period was not feasible for our group. We restricted the adjudications to the main primary publication of trials. Pilot projects, methodology articles, and rationale articles, although not available for all RCTs,5,21 may be able to provide in-depth information on the nuances of the trial design for further assessment. It was not feasible to contact more than 600 investigative teams to clarify elements regarding their trial so we relied on publication materials; however, it is unlikely this clarification would have shifted the results meaningfully.

Conclusions

The level of pragmatism increased moderately over time in CV trials. Greater focus on the design and delivery of CV trials will be required for filling the knowledge gap and for the broad application of the studied interventions.

eTable 1. Number of randomized clinical trials identified with including different study publication years

eTable 2. Level of pragmatism across different design domains

eTable 3. PRECIS-2 scores in studies with different levels of risk determined by Cochrane risk of bias tool

eTable 4. Study characteristics between pragmatic and non-pragmatic randomized clinical trials

eTable 5. Self-identified pragmatic and explanatory trials

eTable 6. PRECIS-2 score across different domains of trial design in self-identified pragmatic or explanatory randomized clinical trials and others

eTable 7. Trial phase, placebo use and number of sites in self-identified pragmatic and explanatory trials compared to otherseTable 8. Number of studies with ≥1, ≥2, and ≥3 difference between two adjudicators for each PRECIS-2 domain

eFigure 1. The PRagmatic-Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary 2 (PRECIS-2) wheel

eFigure 2. PRECIS-2 score across different domains of trial design

eFigure 3. The level of pragmatism between trials published in different journals (e3A) and journal categories (e3B), the trend over time of pragmatism (e3C), and PRECIS-2 scores across different domains between general medicine and cardiology journals (e3D)

eFigure 4. PRECIS-2 score between self-identified pragmatic and explanatory trials compared to others

eReferences.

References

- 1.Califf RM, Sugarman J. Exploring the ethical and regulatory issues in pragmatic clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2015;12(5):436-441. doi: 10.1177/1740774515598334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz D, Lellouch J. Explanatory and pragmatic attitudes in therapeutical trials. J Chronic Dis. 1967;20(8):637-648. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(67)90041-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz D, Lellouch J. Explanatory and pragmatic attitudes in therapeutical trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):499-505. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M, Oxman AD, et al. A pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS): a tool to help trial designers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):464-475. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson KE, Neta G, Dember LM, et al. Use of PRECIS ratings in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory. Trials. 2016;17:32. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1158-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, Donnan P, Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ. 2015;350:h2147. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loudon K, Zwarenstein M, Sullivan F, Donnan P, Treweek S. Making clinical trials more relevant: improving and validating the PRECIS tool for matching trial design decisions to trial purpose. Trials. 2013;14:115. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bratton DJ, Nunn AJ. Alternative approaches to tuberculosis treatment evaluation: the role of pragmatic trials. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(4):440-446. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glasgow RE, Gaglio B, Bennett G, et al. Applying the PRECIS criteria to describe three effectiveness trials of weight loss in obese patients with comorbid conditions. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(3 Pt 1):1051-1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01347.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koppenaal T, Linmans J, Knottnerus JA, Spigt M. Pragmatic vs. explanatory: an adaptation of the PRECIS tool helps to judge the applicability of systematic reviews for daily practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(10):1095-1101. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luoma KA, Leavitt IM, Marrs JC, et al. How can clinical practices pragmatically increase physical activity for patients with type 2 diabetes? a systematic review. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(4):751-772. doi: 10.1007/s13142-017-0502-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witt CM, Manheimer E, Hammerschlag R, et al. How well do randomized trials inform decision making: systematic review using comparative effectiveness research measures on acupuncture for back pain. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e32399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bossie CA, Alphs LD, Williamson D, Mao L, Kurut C; ASPECT-R RATER TEAM . Inter-rater Reliability Assessment of ASPECT-R: (A Study Pragmatic-Explanatory Characterization Tool-Rating). Innov Clin Neurosci. 2016;13(3-4):27-31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alphs LD, Bossie CA. ASPECT-R: a tool to rate the pragmatic and explanatory characteristics of a clinical trial design. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2016;13(1-2):15-26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tosh G, Soares-Weiser K, Adams CE. Pragmatic vs explanatory trials: the pragmascope tool to help measure differences in protocols of mental health randomized controlled trials. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(2):209-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for Behavioral Sciences. Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dal-Ré R, Janiaud P, Ioannidis JPA. Real-world evidence: How pragmatic are randomized controlled trials labeled as pragmatic? BMC Med. 2018;16(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1038-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fanaroff AC, Califf RM, Windecker S, Smith SC Jr, Lopes RD. Levels of Evidence Supporting American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology Guidelines, 2008-2018. JAMA. 2019;321(11):1069-1080. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM, Smith SC Jr. Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines. JAMA. 2009;301(8):831-841. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janiaud P, Dal-Ré R, Ioannidis JPA. Assessment of pragmatism in recently published randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(9):1278-1280. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Loudon K. PRECIS-2 helps researchers design more applicable RCTs while CONSORT Extension for Pragmatic Trials helps knowledge users decide whether to apply them. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;84:27-29. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Number of randomized clinical trials identified with including different study publication years

eTable 2. Level of pragmatism across different design domains

eTable 3. PRECIS-2 scores in studies with different levels of risk determined by Cochrane risk of bias tool

eTable 4. Study characteristics between pragmatic and non-pragmatic randomized clinical trials

eTable 5. Self-identified pragmatic and explanatory trials

eTable 6. PRECIS-2 score across different domains of trial design in self-identified pragmatic or explanatory randomized clinical trials and others

eTable 7. Trial phase, placebo use and number of sites in self-identified pragmatic and explanatory trials compared to otherseTable 8. Number of studies with ≥1, ≥2, and ≥3 difference between two adjudicators for each PRECIS-2 domain

eFigure 1. The PRagmatic-Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary 2 (PRECIS-2) wheel

eFigure 2. PRECIS-2 score across different domains of trial design

eFigure 3. The level of pragmatism between trials published in different journals (e3A) and journal categories (e3B), the trend over time of pragmatism (e3C), and PRECIS-2 scores across different domains between general medicine and cardiology journals (e3D)

eFigure 4. PRECIS-2 score between self-identified pragmatic and explanatory trials compared to others

eReferences.