Abstract

Living cells contain numerous membrane-less RNA/protein (RNP) bodies that assemble by intracellular liquid-liquid phase separation. The properties of these condensed phase droplets are increasingly recognized as important in their physiological function within living cells, and also through the link to protein aggregation pathologies. However, techniques such as droplet coalescence analysis or standard microrheology do not always enable robust property measurements of model RNA/protein droplets in vitro. Here, we introduce a microfluidic platform that drives protein droplets into a single large phase, which facilitates viscosity measurements using passive microrheology and/or active two-phase flow analysis. We use this technique to study various phase separating proteins from structures including P granules, nucleoli, and Whi3 droplets. In each case, droplets exhibit simple liquid behavior, with shear rate-independent viscosities, over observed timescales. Interestingly, we find that a reported order of magnitude difference between the timescale of Whi3 and LAF-1 droplet coalescence is driven by large differences in surface tension rather than viscosity, with implications for droplet assembly and function. The ability to simultaneously perform active and passive microrheological measurements enables studying the impact of ATP-dependent biological activity on RNP droplets, which is a key area for future research.

Introduction

The interior of living cells is highly structured into numerous different types of organelles, which help to organize thousands of simultaneous biomolecular reactions. Canonical organelles are membrane-bound vesicle-like structures, which compartmentalize the cytoplasm using selectively permeable membranes. However, many or even most organelles are membrane-less assemblies, which despite having no lipid bilayer still form compositionally well-defined compartments1. These membrane-less organelles often contain both RNA and protein, and are referred to as RNA granules or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) bodies. Examples include P granules, nucleoli, and Whi3 assemblies (Fig. 1a). Such RNP bodies are typically highly dynamic, freely exchanging components with the surrounding cytoplasm or nucleoplasm. This exchange is likely important to their function as dynamic microreactors, concentrating protein and RNA components and thereby increasing local reaction rates2,3. Conversely, some RNP bodies, such as stress granules, appear to play more of a sequestering role, whereby molecular interactions are slowed or even completely inhibited by sequestration into the body4. Furthermore, RNP bodies are also increasingly recognized as being linked to various protein aggregation pathologies5.

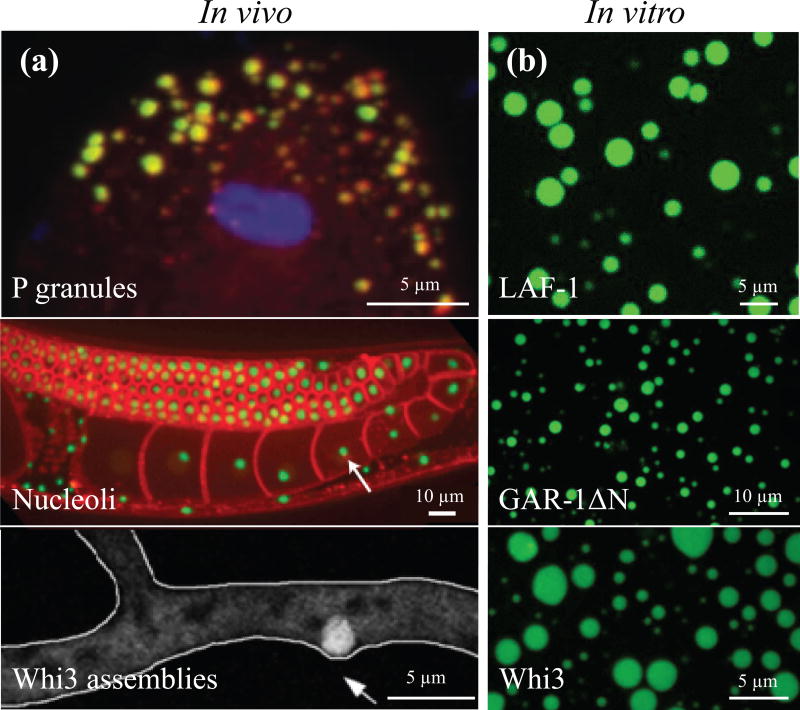

figure 1.

bottom-up reconstitution approach to study membrane-less organelles. (a) p granules (yellow) within the c. elegans embryo, (adapted from elbaum-garfinkle et al6). nucleoli (green) within the c. elegans hermaphrodite gonad with cell membranes in red, (adapted from weber et al7). whi3 assemblies (white circle) in the hypha of the multinucleate fungus ashbya gossypii, (adapted from lee et al8). (b) in vitro droplets of fluorescently labeled laf-1 (125 mm nacl, ~3.5 µm laf-1), gar-1δn (150 mm nacl, ~10 µm gar-1δn), and whi3 proteins (150 mm kcl, 9 µm whi3, 50 nm bni1).

Despite their biological importance, a mechanistic biophysical framework underlying RNP assembly has only recently begun to emerge. Key insights into RNP body assembly have come from the study of the C. elegans embryo, where germline P granules are implicated in specification of progenitor germ cells. P granules were found to localize to germ cells by first dissolving throughout the entire one-cell embryo and only condensing in the posterior, a process dependent on gradients in polarity proteins9,10. These condensed P granules are seen to drip, fuse, and relax to spherical shapes after fusion or shearing, which are behaviors characteristic of viscous liquids9,11. These findings suggested that P granule localization occurs through a spatially-varying liquid-liquid phase separation. Nucleoli also exhibit liquid-like behaviors including fusion, dripping, and power law size scaling characteristic of coarsening emulsions12. Additionally, nucleoli exhibit concentration-dependent assembly and growth dynamics characteristic of a phase transition7,13. Phase transitions increasingly appear to be a ubiquitous mechanism for assembling various other types of RNP bodies, including nuage bodies14, stress granules15, multivalent signaling proteins16, and paraspeckles17.

Many proteins that are enriched in RNP bodies are at least partially unstructured, exhibiting dynamic conformational heterogeneity18. These so-called intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) or low complexity sequence (LCS) proteins are strongly implicated in promoting RNP body assembly14,19. For example, the intrinsically disordered region (IDR) of the RNA helicase Ddx4, a key nuage body protein20, forms droplets in nuclei of HeLa cells when expressed at high concentrations14. Moreover, a closely related P granule RNA helicase, LAF-1, in vitro forms liquid droplets at physiological concentrations, and together with other disordered proteins21 appears to play a key role in P granule assembly6. Similarly, FIB1, a methyltransferase protein responsible for modification of ribosomal RNA in nucleoli, also exhibits concentration-dependent phase separation in vitro13,22. More recently, the IDRs of FUS and RBM14 appear to be essential for paraspeckle targeting and formation17.

IDPs are not only found in physiological liquid-like assemblies, but are also closely associated with irreversible pathological aggregates5,23–26. For example, the purified protein FUS forms solid gels containing amyloid-like fibers27,28, contrasting with the dynamic liquid-like behavior observed in RNP bodies. Moreover, recent evidence with in vitro FUS droplets suggests that IDP phases are often metastable, beginning as liquids but showing signatures of gelation over time28–30. Similar behavior is observed in other IDPs, including other ALS related proteins such as hnRNPA130,31, the Q-rich fungal protein Whi332, and the nucleolar protein FIB122. Since these more solid-like gel phases are expected to slow component diffusion, and thus also reaction rates, these studies raise important questions about the time-dependent progression of biophysical properties and function of RNP bodies6,33,34.

Despite these essential questions about the biophysical nature of RNP bodies, few measurements exist of their viscoelastic properties. Within living cells, the large number of components complicates experimental interpretation, and many recent studies make use of "bottom up" approaches to reconstitute liquid-phase RNP bodies in vitro, using purified proteins and RNA6,29–31,35. Droplet properties may be estimated from the timescale of droplet coalescence9,12,36, but this only gives the ratio of two liquid properties: viscosity and surface tension. Furthermore, this estimate is only accurate if the droplets are simple viscous liquids, precluding the study of viscoelastic fluids. Microrheology is one possible technique that has been employed to directly measure droplet viscoelasticity6,28,32. However, microrheology requires the uptake of probe particles within the condensed phase, which is not always feasible. Moreover, in cases where droplets are small this technique proves increasingly challenging, due to boundary effects or poor particle statistics. Larger droplets are not always achieved at reasonable timescales (i.e., for viscous or low surface tension droplets) when droplet growth is driven by Ostwald ripening or diffusion and coalescence. Even where particles can be incorporated into sufficiently large droplets, unambiguous extraction of droplet properties is only possible for systems in equilibrium, preventing the introduction of ATP-dependent biological activity into in vitro reconstitution studies. Thus, there are few techniques broadly applicable for probing the viscoelasticity of reconstituted liquid-like RNP bodies, which slows progress towards understanding the assembly, properties, and function of this class of organelles.

Here, we overcome these challenges by developing a microfluidic platform that can be used with a variety of different RNA/protein droplet systems. We demonstrate the ability of this system to coalesce droplets for on-chip passive microrheology studies, and also for active rheological measurements using shear stresses applied to a stream of the flowing condensed phase.

Materials and Methods

Protein Purification and In Vitro Transcription

Full-length LAF-1, Whi3, and GAR-1ΔN fragments were tagged with 6×-His and expressed in E. coli using standard procedures. Whi3 purification and BNI1 mRNA transcription were performed following Zhang et al32. Briefly, Whi3 was purified on Ni-NTA (Qiagen) resin and stored in Whi3 elution buffer at −80°C. BNI1 DNA template was obtained using a T7 promoter cloned to the 5’ end of BNI1. DNA template was extracted and transcribed using standard procedures. GAR-1ΔN was purified on Ni-NTA agarose resin (Qiagen) and stored in Ni-elution buffer at −80°C. LAF-1 purification was performed following Elbaum-Garfinkle et al6. LAF-1 was purified on Ni-NTA agarose resin (Qiagen) followed by a HiTrap Heparin column (GE) and stored in Heparin elution buffer. For LAF-1 and GAR-1ΔN, glycerol was added to 10% (vol/vol) before flash freezing in liquid nitrogen and storing at −80°C. See Supplementary Methods for more details.

Device Design and Microfabrication

The microfluidic devices were designed using AutoCAD and fabricated using standard photolithography and soft lithography techniques. Devices had a standard T-junction geometry (Fig. S1a) or box geometry (Fig. S1b) and were 10 µm high.

Device Operation

To achieve on-chip coalescence of GAR-1ΔN, LAF-1, and Whi3, microfluidic devices were prepared with specific surface treatment protocols, (see Supplementary Methods for more details). For microrheology-only experiments (Fig. S1b), a mixed solution of protein droplets and red fluorescent PEG-passivated or –COOH microspheres (Invitrogen) of 0.5 µm diameter were inserted into the top channel at 50 µL/hr and flow was stopped for image analysis. For T-junction devices (Fig. S1a), homogeneous protein solution at the liquid-liquid phase boundary and PEG-passivated microspheres were inserted into the main channel and flow was from left to right at 10 µL/hr. Protein droplets and PEG-passivated or –COOH microspheres were supplied via the orthogonal inlet channel and flow was from bottom to top at 50 µL/hr. After ~30 min – 1 hr, lower flow rates obtained by hydrostatic pressure for both syringes are used for image analysis. In this approach, syringes were removed from the syringe pump and fixed above the device (~ 2–3 feet).

Image Analysis for Microrheology

Microrheology analysis was performed as previously described6,32,37. Red fluorescent microspheres were encapsulated in protein phases as described above. Briefly, measurements were taken at 150-ms time intervals for 150 s and beads were analyzed away from interfaces to minimize boundary effects. Mean-squared displacement (MSD) data were fit to the form MSD = 4Dtα + NF, where α is the diffusive exponent, D is diffusion coefficient, and NF is a constant representing the noise floor. Here, NF was determined experimentally for beads stuck to a coverslip; we find NF ≈ 2×10−5 µm2/s.

Flow Analysis

Velocity profiles are determined in both the protein-lean and protein-rich phases, discussed below. Analysis of time-lapse images of spherical probe particles is used to calculate velocity profiles. In the protein-lean phase, probe particles form streaks due to high fluid velocities and long enough exposure times. Velocity profiles are calculated at a given height in the device by dividing the streak length by the exposure time. In the protein-rich phase probe particles flow slower. Thus, velocities are calculated using the same particle-tracking algorithm used for microrheology. See Supplementary Methods for more details.

Results

To study RNP bodies using a bottom-up reconstitution approach, a number of key protein components were purified. LAF-1, GAR-1, and Whi3 are three proteins known to be important in P granules6, nucleoli38, and Whi3 assemblies8,32, respectively; we use the variant GAR-1ΔN due to technical challenges encountered with full length GAR-1. After purification, all three proteins phase separate in vitro to form spherical droplets (Fig. 1b), reminiscent of those seen in vivo (Fig. 1a). In each of these cases, this phase separation is protein and salt concentration-dependent; interestingly, a lower salt concentration and higher protein concentration favors phase separation. In the case of Whi3, specific mRNA binding partners (i.e., cyclin transripts, CLN3, and formin transcripts, BNI1) shifts the droplet phase boundary down, approaching physiological protein concentrations at physiological salt concentration. Such protein droplets appear to be liquid-like, exhibiting round morphologies after coalescence6,32. Measuring the relaxation time of coalescing droplets enables an estimation of the inverse capillary velocity, μ1/γ, where μ1 is droplet viscosity and γ is the interfacial tension. The reported inverse capillary velocities of Whi3 and LAF-1 droplets exhibit over an order of magnitude difference6,32. However, one cannot infer from coalescence measurements alone whether this difference is dominated by viscosity or surface tension, which are material properties with potentially unique implications for droplet assembly and function22.

On-Chip Passive Microrheology

Measuring the viscosity within protein droplets poses unique challenges. Recent microrheology6,32 techniques used to probe droplet material properties require large droplets relative to bead size, in order to avoid boundary effects. Moreover, small droplets can also be particularly problematic if beads do not readily enter the condensed phase. Additionally, experimental statistics are inherently limited by the incorporated bead density. We find that phase separation of Whi3 and GAR-1ΔN typically leads to a smaller equilibrium droplet volume fraction than for LAF-1, resulting in smaller droplets. Fig. S2 shows GAR-1ΔN after 1 hr phase separation, demonstrating relatively small droplets in which beads are not well-incorporated. To overcome these limitations, we developed a microfluidic approach to coalesce many small droplets into a large continuous condensed protein phase, enabling facile tracking of many particles in a single experiment.

Coalescence is achieved by flowing protein droplets into a microfluidic device where the inlet is filled with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) pillars (Fig. 2a). A whole device schematic is depicted in Fig. S1a. Many protein droplets (green) flow from the circular inlet hole to the rectangular channel, adhere to the bottom glass, top PDMS surface, or PDMS pillars, and coalesce to form a large condensed protein stream (Fig. 2a). Due to favorable droplet-PDMS interactions, inclusion of PDMS pillars traps protein droplets. Favorable droplet-droplet interactions and flow drives coalescence as passing droplets are forced to come into contact with the adhered droplets39; microfluidic devices lacking PDMS pillars did not produce a large droplet phase for Whi3 and GAR-1ΔN. The time sequence in Fig. 2a shows protein droplets sticking to PDMS posts, outlined in yellow, and coalescing with each other to form condensed protein streams within 2 minutes. The generated protein stream is then collected within 10 minutes into the boxed region of the device (Fig. 2b) for subsequent measurements within 2 hours after phase separation.

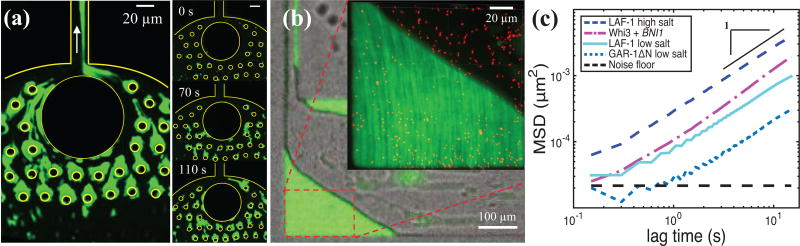

figure 2.

microfluidic-assisted coalescence of protein droplets (e.g., laf-1) into a single protein stream used for microrheology. (a) protein droplets (green) stick to pdms posts and coalesce into a protein-rich stream. right panel shows time-lapse of coalescence; scale bar = 20 µm. (b) brightfield and fluorescent images of a large protein-rich phase in the box microfluidic device. (inset) zoomed in fluorescent image of red tracer beads embedded in the protein-rich phase. (c) msd versus lag time for laf-1 at high salt (250 mm nacl, dark blue dashed line), whi3 at physiological salt in the presence of 53 nm bni1 mrna (150 mm kcl, pink dash-dotted line), laf-1 at low salt (125 mm nacl, cyan solid line), gar-1δn at low salt (150 mm nacl, blue dotted line), and the noise floor (black dashed line). black solid line has a slope of 1; the noise floor is ~ 2 × 10−5 µm2.

Coalescence of sub-micron sized droplets into a single large (~100 µm wide) condensed protein phase generates an ideal experimental platform for microrheology measurements. Particle tracking microrheology relates the motion of tracer beads to the viscoelasticity of the soft material in which they are diffusing. After a substantial protein phase is formed (~20 min), the flow is stopped, and the tracer bead motion is tracked over time and corrected for any remaining drift in the device. The corresponding MSD and viscosity is determined using previously published techniques6,32. The MSD versus lag time for LAF-1 at high salt (250 mM NaCl), Whi3 at physiological salt (150 mM KCl) in the presence of 53 nM BNI1 mRNA, LAF-1 at low salt (125 mM NaCl), GAR-1ΔN at low salt (150 mM NaCl), and the noise floor is shown in Fig. 2c. For LAF-1, decreasing salt concentration causes the bead MSD to shift down, indicating slower bead motion6. At low salt, GAR-1ΔN reaches even lower MSD values. The MSD data were fit to the form MSD = 4Dtα + NF. Using the measured noise floor, NF ~ 2 × 10−5 µm2, α= 0.99 for LAF-1 low salt, 0.97 for LAF-1 high salt, 1.05 for Whi3 with BNI1 mRNA, and 1.04 for GAR-1ΔN low salt; given measurement error, these values are all consistent with a pure viscous liquid (α=1) on these timescales. The diffusion coefficient obtained from the fit, D, and the bead size, R, are then used to determine the droplet viscosity, μ1, from the Stokes-Einstein relation: μ1 = kBT/6πDR, where kBT is the thermal energy scale.

Viscosity values are 51 ± 8 Pa.s for LAF-1 low salt, 13 ± 2 Pa.s for LAF-1 high salt, 198 ± 55 Pa.s for GAR-1ΔN low salt, and 34 ± 10 Pa.s for Whi3 with BNI1 mRNA. For LAF-1 and Whi3, measured values are similar to those previously reported6,32; to our knowledge, these are the first published data on GAR-1ΔN viscosity.

Measuring Viscosity Using ‘Flow’

The experimental protein systems described above are all in apparent equilibrium, where passive thermal microrheology is applicable. However, the properties and fluctuation dynamics of non-equilibrium systems are of particular interest, and nonequilibrium features, such as ATP-dependent activity, are known to impact the properties and dynamics of intracellular RNP bodies12,22,40. Moreover, even in equilibrium systems, it can be challenging to accurately determine the MSD for passive microrheology.

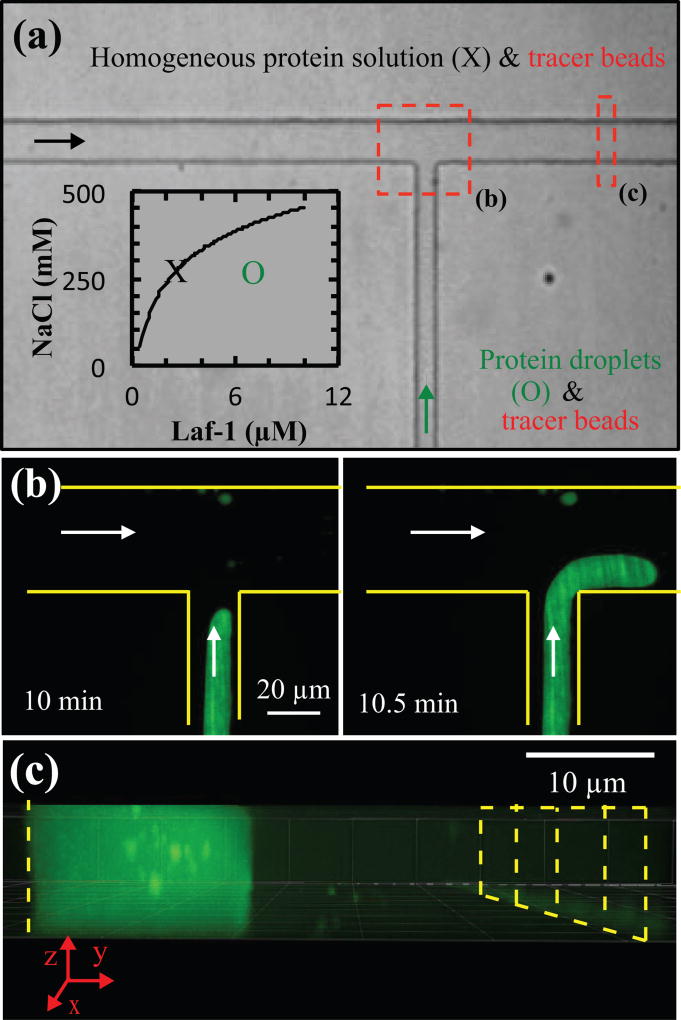

To overcome these challenges, we tested whether the driven flow within our microfluidic platform could be used to probe the properties of the condensed phase, similar to approaches recently described for other types of multiphase fluids41–46. Protein solution at the liquid-liquid phase boundary (i.e., point X in Fig. 3a inset) was inserted into the main channel, and phase-separated protein solution (i.e., point O in Fig. 3a inset) was supplied via the orthogonal inlet channel. As described above and shown in Fig. 2a, protein droplets coalesce to form a single stream within 2 minutes. Adjusting the flow rates supplied to the main and orthogonal channels controls the transverse position and velocity of the resultant protein stream (Fig. 3b). This protein stream fills the entire height of the device and a portion of the width of the device, with the homogeneous protein solution filling the remainder of the device (Fig. 3c).

figure 3.

setup of protein stream for flow analysis. (a) protein solution at the phase boundary (e.g., x in inset) and peg-passivated probe particles flow along the main channel from left to right, and protein droplets (e.g., o in inset) and peg-passivated or -cooh probe particles are supplied via the orthogonal inlet channel; arrows indicate the direction of flow. area indicated by red dashed boxes is shown in panels b and c. (b) the position and velocity of the protein stream is manipulated using the main and orthogonal channels. (c) the protein-rich stream fills the entire height of the microfluidic device with the protein-lean phase filling the remaining width of the channel. yellow dashed and solid lines outline the channel walls.

Inclusion of microbeads in protein solutions in both channels (see Methods) enables the velocity profiles of both protein phases to be determined (Fig. 3a). Flow rates are controlled using hydrostatic pressure (see Methods) after ~ 30 minutes to 1 hr to obtain lower velocities in the homogeneous protein solution or protein-lean phase. Velocity profiles in the protein-lean and protein-rich (condensed protein) phase are determined far enough from the T-junction (red dashed box in Fig. 4a) so that the protein-rich/protein-lean interface is flat (Fig. 4b y = 0). Analysis of time-lapse images of PEG-passivated probe particles is used to calculate velocity profiles (see Methods). In the protein-lean phase, probe particles appear as streaks due to high fluid velocities relative to the exposure time (top of Fig. 4b − w2 < y < 0). Probe particles in the protein-rich phase appear spherical due to slower fluid velocities resulting from the higher viscosity (bottom of Fig. 4b, w1 > y > 0).

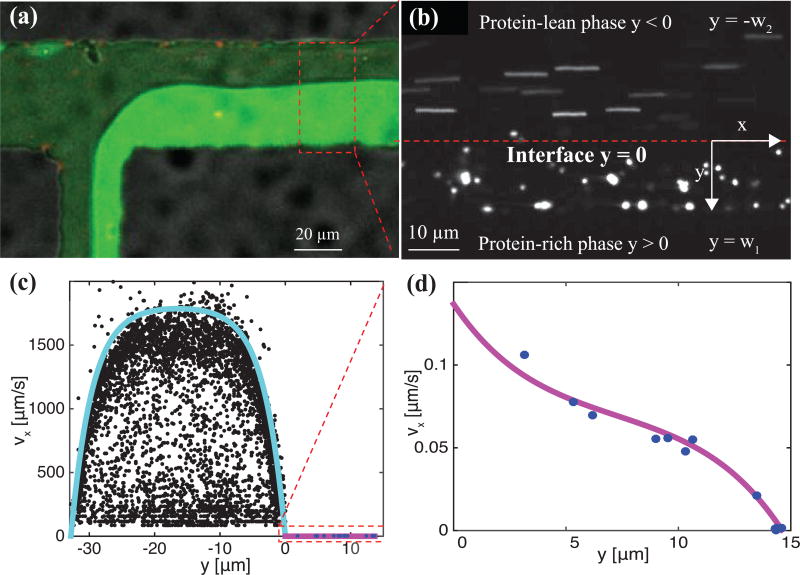

figure 4.

red peg-passivated probe particles are used to quantify velocity profiles in the protein-rich (green) and protein-lean (black) phase. (a) velocity profiles are quantified far from the t-junction (i.e., red dashed box) where the protein-rich/protein-lean interface is mostly flat. (b) to quantify velocity profiles in the protein-lean phase, the length of probe particle streaks and corresponding exposure times are used. velocity profiles in the protein-rich phase are determined by microparticle tracking velocimetry. the red-dashed line denotes the protein-rich/protein-lean interface and particle streaks and single particles are seen in the protein-lean and protein-rich phases, respectively. (c) measured velocity profiles in the protein-lean (filled black circles) and protein-rich (filled blue circles) phase. (d) zoomed in view of protein-rich (filled blue circles) phase. lines are drawn using Eqs. (1) and (2) with β = −0.15 pa/m and μ1= 26.8 pa.s.

The position of the fluid-fluid interface and the velocity profiles in each fluid are controlled by the ratio of the viscosities between the protein-lean and protein-rich phases and pressure drop in the channel. The viscosity of the protein-lean phase was determined using microrheology and is close to that of water. Thus, modeling the velocity profiles given an interface position determines both the pressure drop and the protein-rich phase viscosity or protein droplet viscosity. Solving the Navier-Stokes equations in both the protein-rich and protein-lean phases and equating the velocity and shear stresses at the interface determine both velocity profiles (Supplementary Methods).

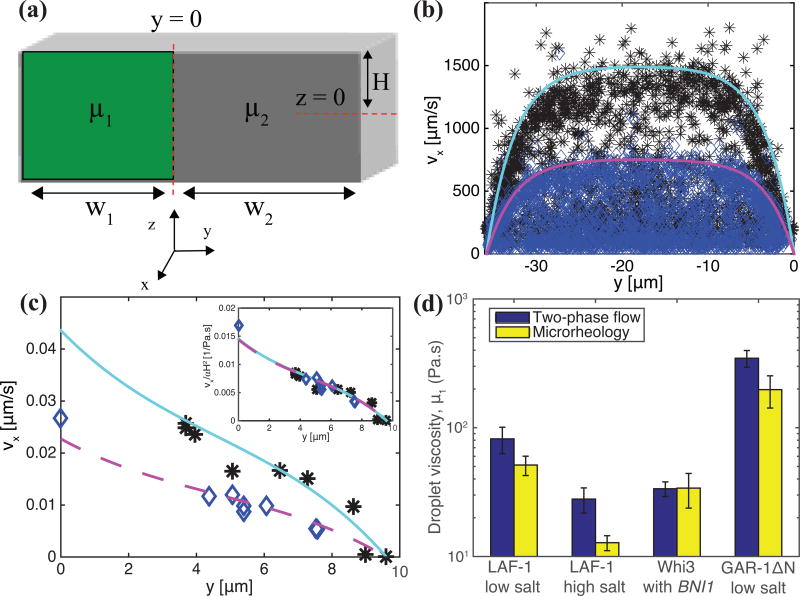

We present a side view schematic (Fig. 5a), shown with overlaid model parameters for flow in the x direction, of protein-rich and protein-lean phases within the microfluidic devices with viscosities μ1 and μ2, respectively. At the solid surfaces (PDMS walls at y = −w2, y = w1, and z = H and glass surface at z = −H), the velocities of the protein-rich and protein-lean phases are zero. At the fluid-fluid interface at y = 0, the velocities and shear stresses in each phase are equated. The resulting velocity profiles in the protein-rich (i.e., νx,1(y, z)) and protein-lean (i.e., νx,2 (y, z)) phase are

| (1) |

| (2) |

where β is the pressure gradient, are eigenvalues, and C1 and C2 are constants (defined in Supplementary Methods). In the limit μ1 >> μ2, as is the case here, the velocity at the fluid-fluid interface is almost zero and the maximum value of νx,2 (y, z) at a given z plane is strongly controlled by β. Accordingly, β is found by fixing μ1/μ2 at 1000 or greater and fitting the velocity profile in the protein-lean phase, νx,2 (y, z), to β. With this value of β, the ratio μ1/μ2 is used to fit the velocity profile in the protein-rich phase, νx,1(y, z). In Fig. 4c and 4d the velocity profiles are well described by this 2d analytical model.

figure 5.

(a) model symbols and geometry. measured velocity profiles in the (b) protein-lean phase and (c) protein-rich phase at high (black asterisks) and low (blue diamonds) shear rates. cyan and magenta lines are drawn using Eqs. (1) and (2) with β = −0.12 pa/m and μ1 = 65 pa.s and β = −0.06 pa/m and μ1 = 63 pa.s, respectively. (d) protein-rich phase viscosity, μ1, for each protein investigated measured using microrheology (yellow bars) and two-phase flow analysis (blue bars). typical error bars are shown and represent standard deviation of at least three replicates.

Eqs. (1) and (2) assume the protein-rich phase has constant viscosity, independent of shear stress or shear rate. To test this hypothesis we varied the shear rate by using higher flow rates and measured the viscosity. Fig. 5 depicts the velocity profiles for two shear rates applied to LAF-1 low salt condensed phase in the protein-lean (Fig. 5b) and protein-rich (Fig. 5c) phases with blue diamonds and black asterisks corresponding to low and high shear rates, respectively. Due to the higher flow rates at high shear, the maximum velocity in both the protein-rich and protein-lean phases is greater. Fitting the velocity profiles to values of β and μ1/μ2 results in protein-rich phase viscosities of 63 Pa.s and 65 Pa.s for high and low shear, respectively. Thus, the protein-rich phase viscosity is approximately independent of shear rates in the range of flow rates used here.

Using Eqs. (1) and (2), condensed protein phase viscosities are measured and compared to microrheology measurements of LAF-1, Whi3, and GAR-1ΔN protein droplets no later than 2 hours after phase separation. Fig. 5d shows the comparison between viscosities of LAF-1, Whi3, and GAR-1ΔN droplets determined using microrheology and this two-phase flow approach. Protein-rich phase viscosities measured using flow analysis are in reasonable agreement with those using particle-tracking microrheology. Importantly, this flow method also accurately captures the trend of decreasing LAF-1 droplet viscosity with increasing salt concentration6 and the relative differences in droplet viscosity between different proteins. The decrease in droplet viscosity with increasing salt concentration reflects reduced intermolecular interaction strength6 and is consistent with salt disrupting the protein phase separation. The much higher viscosity of GAR-1ΔN indicates stronger intermolecular interactions between GAR-1ΔN molecules than between LAF-1 or Whi3 molecules.

Discussion and Conclusion

In recent years, increasing numbers of intracellular RNP bodies have been shown to exhibit liquid-like properties1,3,47. But we are only beginning to determine the physical mechanisms that give rise to these collective assemblies, and the molecular features that dictate mesoscopic properties and their impact on function. For example, surface tension was recently shown to be a key parameter controlling the architecture of the nucleolus22. Moreover, surface tension is known to influence the assembly and coarsening kinetics of condensed phases, which thus dictates the droplet size distribution. While larger RNP bodies may be expected to process more molecules, they may be inefficient microreactors due to decreased transport efficiency in larger volumes. Molecular encounter rates will clearly also be strongly impacted by droplet viscosity, providing another potentially tunable parameter for controlling droplet functionality.

Establishing how RNP body properties could be regulated requires first measuring these properties, however there are still few studies that undertake systematic analysis of droplet properties. While previous work analyzing droplet coalescence has determined that the inverse capillary velocity of Whi3 (9 s/µm) and LAF-1 (0.12 s/µm) vary by almost two orders of magnitude, measurements using our microfluidic platform show their viscosities only differ by roughly two-fold (34 Pa.s versus 82 Pa.s for flow analysis, respectively). Together with the reported inverse capillary velocities, this yields droplet surface tensions of 4 and 680 µN/m for Whi3 and LAF-1, respectively, indicating that a significant difference in surface tension drives the variance in droplet coalescence timescales. Future studies of surface tension and droplet viscoelasticity as a function of shear rate, and the age of the condensed phase, will be required to elucidate whether such in vitro droplets remain as Newtonian fluids, and whether they can transition into potentially pathological solid states.

A clear advantage of using our platform for microfluidic-facilitated coalescence is that it enables viscosity measurements of small droplets, which previously could not be performed with some proteins, including GAR-1ΔN and Whi3 with low concentrations of mRNA. Furthermore, this microfluidic approach requires minimal volumes of protein solution. This step is important since IDPs can be challenging to express and purify in large quantities, as they often form inclusion bodies48. As little as 10 µL of phase-separated protein solution enabled viscosity measurements both by microrheology and flow analysis; previous microrheology methods6,32 required roughly six-fold more material, 60–80 µL of phase-separated protein solution.

Using flow analysis to measure droplet viscosity offers several advantages over passive microrheology. Because this method actively shears the condensed droplet phase and uses the resulting velocity profiles to measure viscosity, this enables the analysis of non-equilibrium systems. Such an active microrheological approach could also be essential for high viscosity phases. Closer inspection of Fig. 2c also reveals that protein droplets more viscous than GAR-1ΔN (198 ± 55 Pa.s) would challenge analysis, since the MSD becomes very close to the noise floor (black dashed line); measurements on longer timescales would lead to MSD further from the noise floor, but introduce complications arising from microscope stage drift49. Reliable velocity profiles at shorter timescales in the protein-rich phase, and thus accurate viscosities by flow analysis, can be obtained by using higher flow rates in the protein-lean phase.

Despite the power of purified RNA/protein droplet systems, it is important to recognize that in vivo many other proteins reside within RNP bodies, and various forms of biological activity may drive the droplets out of equilibrium50–54. To build complexity into in vitro systems requires determining how much and how fast separate components affect material properties such as viscosity. The second inlet of this design offers a simple method to introduce an additional component and measure the effect that it has on the protein-rich phase viscosity. More complexity could be built in by designing additional channels and valves. Our device will also be useful in future studies due to its enabling of simultaneous active and passive rheological measurements. Combining these two approaches has proven useful in elucidating interesting physics in various non-equilibrium materials, particularly the cytoskeleton55,56. We anticipate that approaches such as those described here will be useful in understanding the intersection of equilibrium assembly/properties with nonequilibrium tuning, which is likely key to pathological dysregulation of condensed intracellular phases36,40,57–59.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Brangwynne laboratory for discussions. We also thank Sravanti Uppaluri for help with initial device fabrication and image analysis, and Erin Langdon and Amy Gladfelter for assistance with Whi3 constructs. We acknowledge funding from the Princeton Center for Complex Materials, a MRSEC supported by NSF Grant DMR 1420541. This work was also supported by an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (1DP2GM105437-01), an NSF CAREER award (1253035), and an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship award (DGE 1148900).

References

- 1.Brangwynne CP, Tompa P, Pappu RV. Nat. Phys. 2015;11:899–904. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strzelecka M, Trowitzsch S, Weber G, Lührmann R, Oates AC, Neugebauer KM. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:403–409. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brangwynne CP. Soft Matter. 2011;7:3052–3059. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balagopal V, Parker R. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009;21:403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li YR, King OD, Shorter J, Gitler AD. J Cell Biol. 2013;201:361–372. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201302044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elbaum-Garfinkle S, Kim Y, Szczepaniak K, Chen CC-H, Eckmann CR, Myong S, Brangwynne CP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:7189–7194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504822112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weber SC, Brangwynne CP. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:641–646. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee C, Occhipinti P, Gladfelter AS. J Cell Biol. 2015;208:533–544. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201407105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brangwynne CP, Eckmann CR, Courson DS, Rybarska A, Hoege C, Gharakhani J, Jülicher F, Hyman AA. Science. 2009;324:1729–1732. doi: 10.1126/science.1172046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee CF, Brangwynne CP, Gharakhani J, Hyman AA, Jülicher F. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013;111:088101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.088101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aarts DGAL, Schmidt M, Lekkerkerker HNW. Science. 2004;304:847–850. doi: 10.1126/science.1097116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brangwynne CP, Mitchison TJ, Hyman AA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:4334–4339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017150108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berry J, Weber SC, Vaidya N, Haataja M, Brangwynne CP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:E5237–E5245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509317112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nott TJ, Petsalaki E, Farber P, Jervis D, Fussner E, Plochowietz A, Craggs TD, Bazett-Jones DP, Pawson T, Forman-Kay JD, Baldwin AJ. Mol. Cell. 2015;57:936–947. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wippich F, Bodenmiller B, Trajkovska MG, Wanka S, Aebersold R, Pelkmans L. Cell. 2013;152:791–805. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li P, Banjade S, Cheng H-C, Kim S, Chen B, Guo L, Llaguno M, Hollingsworth JV, King DS, Banani SF, Russo PS, Jiang Q-X, Nixon BT, Rosen MK. Nature. 2012;483:336–340. doi: 10.1038/nature10879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hennig S, Kong G, Mannen T, Sadowska A, Kobelke S, Blythe A, Knott GJ, Iyer KS, Ho D, Newcombe EA, Hosoki K, Goshima N, Kawaguchi T, Hatters D, Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Hirose T, Bond CS, Fox AH. J Cell Biol. 2015;210:529–539. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201504117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2014;83:553–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-072711-164947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Der Lee R, Buljan M, Lang B, Weatheritt RJ, Daughdrill GW, Dunker aK, Fuxreiter M, Gough J, Gsponer J, Jones DT, Kim PM, Kriwacki RW, Old CJ, Pappu RV, Tompa P, Uversky VN, Wright PE, Babu MM. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:6589–6631. doi: 10.1021/cr400525m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang L, Diehl-Jones W, Lasko P. Development. 1994;120:1201–1211. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.5.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang JT, Smith J, Chen B-C, Schmidt H, Rasoloson D, Paix A, Lambrus BG, Calidas D, Betzig E, Seydoux G. Elife. 2014;3:e04591. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feric M, Vaidya N, Harmon TS, Mitrea DM, Zhu L, Richardson TM, Kriwacki RW, Pappu RV, Brangwynne CP. Cell. 2016;165:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HJ, Kim NC, Wang Y-D, Scarborough EA, Moore J, Diaz Z, MacLea KS, Freibaum B, Li S, Molliex A, Kanagaraj AP, Carter R, Boylan KB, Wojtas AM, Rademakers R, Pinkus JL, Greenberg SA, Trojanowski JQ, Traynor BJ, Smith BN, Topp S, Gkazi A-S, Miller J, Shaw CE, Kottlors M, Kirschner J, Pestronk A, Li YR, Ford AF, Gitler AD, Benatar M, King OD, Kimonis VE, Ross ED, Weihl CC, Shorter J, Taylor JP. Nature. 2013;495:467–473. doi: 10.1038/nature11922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramaswami M, Taylor JP, Parker R. Cell. 2013;154:727–736. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gitler AD, Shorter J. Prion. 2011;5:179–187. doi: 10.4161/pri.5.3.17230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alberti S, Halfmann R, King O, Kapila A, Lindquist S. Cell. 2009;137:146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kato M, Han TW, Xie S, Shi K, Du X, Wu LC, Mirzaei H, Goldsmith EJ, Longgood J, Pei J, Grishin NV, Frantz DE, Schneider JW, Chen S, Li L, Sawaya MR, Eisenberg D, Tycko R, McKnight SL. Cell. 2012;149:753–767. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murakami T, Qamar S, Lin JQ, Schierle GSK, Rees E, Miyashita A, Costa AR, Dodd RB, Chan FTS, Michel CH, Kronenberg-Versteeg D, Li Y, Yang S-P, Wakutani Y, Meadows W, Ferry RR, Dong L, Tartaglia GG, Favrin G, Lin W-L, Dickson DW, Zhen M, Ron D, Schmitt-Ulms G, Fraser PE, Shneider NA, Holt C, Vendruscolo M, Kaminski CF, George-Hyslop PS. Neuron. 2015;88:678–690. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel A, Lee HO, Jawerth L, Maharana S, Jahnel M, Hein MY, Stoynov S, Mahamid J, Saha S, Franzmann TM, Pozniakovski A, Poser I, Maghelli N, Royer LA, Weigert M, Myers EW, Grill S, Drechsel D, Hyman AA, Alberti S. Cell. 2015;162:1066–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin Y, Protter DSW, Rosen MK, Parker R, Lin Y, Protter DSW, Rosen MK, Parker R. Mol. Cell. 2015;60:208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molliex A, Temirov J, Lee J, Kim HJ, Mittag T, Taylor JP, Molliex A, Temirov J, Lee J, Coughlin M, Kanagaraj AP, Kim HJ. Cell. 2015;163:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang H, Elbaum-Garfinkle S, Langdon EM, Taylor N, Occhipinti P, Bridges AA, Brangwynne CP, Gladfelter AS. Mol. Cell. 2015;60:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weber SC, Brangwynne CP. Cell. 2012;149:1188–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo L, Shorter J. Mol. Cell. 2015;60:189–192. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aumiller WM, Keating CD. Nat. Chem. 2016;8:129–137. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hubstenberger A, Noble SL, Cameron C, Evans TC. Dev. Cell. 2013;27:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feric M, Brangwynne CP. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013;15:1253–1259. doi: 10.1038/ncb2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang C, Meier UT. EMBO J. 2004;23:1857–1867. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fidalgo LM, Abell C, Huck WTS. Lab Chip. 2007;7:984–986. doi: 10.1039/b708091c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kroschwald S, Maharana S, Mateju D, Malinovska L, Nüske E, Poser I, Richter D, Alberti S. Elife. 2015;4:e06807. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galambos P, Forster F. ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. Anaheim, CA: 1998. pp. 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Groisman A, Quake SR. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004;92:094501–1. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.094501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Groisman A, Enzelberger M, Quake SR. Science. 2003;300:955–958. doi: 10.1126/science.1083694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guillot P, Panizza P, Salmon J, Joanicot M, Colin A, Bruneau C, Colin T. Langmuir. 2006;22:6438–6445. doi: 10.1021/la060131z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guillot P, Moulin T, Kötitz R, Guirardel M, Dodge A, Joanicot M, Colin A, Bruneau C-H, Colin T. Microfluid. Nanofluidics. 2008;5:619–630. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guillot P, Colin A. Microfluid. Nanofluidics. 2014;17:605–611. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hyman AA, Weber CA, Jülicher F. Annu. Rev. cell Dev. Biol. 2014;30:39–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fink AL. Fold. Des. 1998;3:9–23. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(98)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moschakis T, Murray BS, Dickinson E. Langmuir. 2006;22:4710–4719. doi: 10.1021/la0533258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsai RYL, McKay RDG. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:179–184. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Finch RA, Revankar GR, Chan PK. J Biol. Chem. 1993;268:5823–5827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bleichert F, Baserga SJ. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:339–352. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andersen J, Lam Y, Leung A, Ong S-E, Lyon C, Lamond A, Mann M. Nature. 2005;433:77–83. doi: 10.1038/nature03207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zwicker D, Decker M, Jaensch S, Hyman AA, Jülicher F. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:E2636–E2645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404855111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mizuno D, Tardin C, Schmidt CF, Mackintosh FC. Science. 2007;315:370–373. doi: 10.1126/science.1134404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bertrand OJN, Fygenson DK, Saleh OA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:17342–17347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208732109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jackrel ME, Desantis ME, Martinez BA, Castellano LM, Stewart RM, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA, Shorter J. Cell. 2014;156:170–182. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Buchan JR, Kolaitis RM, Taylor JP, Parker R. Cell. 2013;153:1461–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sweeny EA, Jackrel ME, Go MS, Sochor MA, Razzo BM, DeSantis ME, Gupta K, Shorter J. Mol. Cell. 2015;57:836–849. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.