Abstract

The CaVβ subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels regulate these channels in several ways. Here we investigate the role of these auxiliary subunits in the expression of functional N-type channels at the plasma membrane and in the modulation by G-protein-coupled receptors of this neuronal channel. To do so, we mutated tryptophan 391 to an alanine within the α-interacting domain (AID) in the I-II linker of CaV2.2. We showed that the mutation W391 virtually abolishes the binding of CaVβ1b and CaVβ2a to the CaV2.2 I-II linker and strongly reduced current density and cell surface expression of both CaV2.2/α2δ-2/β1b and/β2a channels. When associated with CaVβ1b, the W391A mutation also prevented the CaVβ1b-mediated hyperpolarization of CaV2.2 channel activation and steady-state inactivation. However, the mutated CaV2.2W391A/β1b channels were still inhibited to a similar extent by activation of the D2 dopamine receptor with the agonist quinpirole. Nevertheless, key hallmarks of G-protein modulation of N-type currents, such as slowed activation kinetics and prepulse facilitation, were not observed for the mutated channel. In contrast, CaVβ2a was still able to completely modulate the biophysical properties of CaV2.2W391A channel and allow voltage-dependent G-protein modulation of CaV2.2W391A. Additional data suggest that the concentration of CaVβ2a in the proximity of the channel is enhanced independently of its binding to the AID by its palmitoylation. This is essentially sufficient for all of the functional effects of CaVβ2a, which may occur via a second lower-affinity binding site, except trafficking the channel to the plasma membrane, which requires interaction with the AID region.

Keywords: calcium channel, neuron, α-interaction domain, β subunit, trafficking, G-protein, palmitoylation

Introduction

Voltage-gated calcium (CaV) channels play a major role in the physiology of excitable cells, particularly of neurons. Three families of voltage-gated calcium channels have been identified, CaV1-CaV3 (for review, see Ertel et al., 2000). The CaV1 class, L-type channels and the CaV2 class, non-L-type channels are both high-voltage-activated (HVA). These are heteromultimers composed of the pore-forming α1 subunit, associated with auxiliary CaVβ and α2δ subunits (for review, see Catterall, 2000). The CaV2 calcium channels are inhibited by Gβγ dimers (Herlitze et al., 1996; Ikeda, 1996), which is the main mechanism of presynaptic inhibition by G-protein-coupled receptors. CaVβ subunits are crucial for normal HVA channel function (for review, see Dolphin, 2003a), because they enhance expression of functional channels at the plasma membrane, modulate their biophysical properties, and promote the voltage dependence of modulation of CaV2.2 calcium channels by Gβγ dimers, although the mechanism involved remains unclear (Bichet et al., 2000; Meir et al., 2000; Canti et al., 2001). Gβγ dimers and CaVβ subunits have been shown to bind to overlapping sites in the I-II loop of CaV2 channels, and they induce opposite effects on biophysical properties of the channels (for review, see Dolphin, 2003b), shifting channels between a willing and a reluctant state that requires large depolarizations to be opened (Bean, 1989). This observation led to the hypothesis that the binding of Gβγ dimers might dissociate the CaVβ subunit from the I-II loop of the α1 subunit (Sandoz et al., 2004) and that dissociation of CaVβ was the mechanism responsible for the inhibition observed. However, there is also evidence that Gβγ dimers do not displace CaVβ subunits but alter the orientation of the subunit with respect to the α1 subunit (Hummer et al., 2003).

Here, we investigated the role of CaVβ subunits in the plasma membrane expression and G-protein modulation of CaV2.2 calcium channels by mutating the tryptophan (W391) in the α1-interacting domain (AID) in the I-II loop of CaV2.2. This amino acid has been shown both by the study that identified the AID motif and the recent structural studies to be key to the interaction between CaVβ subunits and the AID (Pragnell et al., 1994; Chen et al., 2004; Opatowsky et al., 2004; Van Petegem et al., 2004). This mutation prevents the enhancement of functional expression of CaV2.2 by CaVβ1b and also prevents modulation of CaV2.2 by this subunit. In addition, although the G-protein modulation of CaV2.2W391A was present, it was not voltage dependent. In contrast, only the expression of the channel at the plasma membrane was affected when CaVβ2a was coexpressed with this mutant channel, whereas all of the biophysical properties of the expressed CaV2.2W391A channels were still normally modulated by CaVβ2a, including the voltage dependence of G-protein modulation. Our results further show that this was dependent on palmitoylation of CaVβ2a and suggest that the effect of CaVβ subunits on the voltage-dependent properties of the CaV2.2 channels occurs not only via the high-affinity I-II linker interaction but also via low-affinity interactions, presumably with other sites on the channel.

Materials and Methods

Materials. The cDNAs used in this study were CaV2.2 (D14157), CaVβ1b (X61394), CaVβ3 (M88751), CaVβ2a(M88751), CaVβ2a-β1b chimera (Olcese et al., 1994), α2δ-2 (Barclay et al., 2001), and D2 dopamine receptor (X17458). The green fluorescent protein (GFP-mut3b, U73901) was used to identify transfected cells. All cDNAs were subcloned in pMT2.

Construction, expression, and purification of proteins. CaV2.2W391A was generated by site-directed mutagenesis with primers for CaV2.2W391A.F (5′CGGGTACCTGGAGGCGATCTTCAAGGCTGAG) and CaV2.2W391A.R (5′CTCAGCCTTGAAGATCGCCTCCAGGTACCCG).

CaV2.2 I-II loop in pGEX2T (Bell et al., 2001) [glutathione S-transferase (GST)-CaV2.2 I-II loop] was modified by PCR using Pfu polymerase (Stratagene, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) with the oligonucleotide primers 5′-ATGCTGGCCGAGGAGGACAGGAATGCAGAG-3′ and 5′-GACTCATTCCTCCGCCTTGAAGATCCACTCCAGGTAC-3′, which truncate the CaV2.2 I-II loop after the region encoding the AID. In this way, a construct was generated encoding the first 40 residues of the CaV2.2 I-II loop, incorporating the AID, fused to GST to form GST-CaV2.2(357-397)WT. Mutagenesis of GST-CaV2.2(357-397)WT was performed as described above using the primers 5′-ATCTTCAAGGCGGAGGAATGAGTCATGCTGGCCG-3′ and 5′-AGCCTCCAGGTACCCGTTGAGCTCTCGCTCGATC-3′ to substitute an alanine for W391. GST-CaV2.2(357-397)WT, GST-CaV2.2(357-397)W391A, and GST were expressed and purified as described for GST-CaV2.2 I-II loop by Bell et al. (2001). N-Terminally His-tagged Cavβ2a (H6N-Cavβ2a) and C-terminally His-tagged Cavβ1b (Cavβ1b-H6C) were expressed and purified as described by Bell et al. (2001).

Surface plasmon resonance. Assays were performed using a BIAcore 2000 (Biacore, Uppsala, Sweden) at 25°C using running buffer (20 mm Na phosphate, pH 7.5, 500 mm NaCl, and 0.005% Tween 20). Anti-GST monoclonal antibodies (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, UK) were covalently attached to the surface of CM5 dextran sensor chips according to the instructions of the manufacturer to allow the reversible immobilization of GST-fusion proteins. Approximately equivalent molar quantities ∼350 resonance units (RU) of GST-CaV2.2(357-397)WT, ∼350 RU of GST-CaV2.2(357-397)W391A, and ∼300 RU of GST were immobilized on successive flow cells of a sensor chip. The flow rate of running buffer was 25 μl/min. H6N-Cavβ2a and Cavβ1b-H6C were dialyzed against running buffer and diluted to a series of concentrations. These samples were applied for 6 min over all flow cells, and each injection was followed by a similar dissociation phase. The sensor chip surface was regenerated between injections by the application of 35 μl of 20 mm glycine/HCl, pH 2.2, at 10 μl/min and the immobilization of fresh ligand.

Sensorgrams were processed using the BIAevaluation 3.0 software (Biacore). Sensorgrams recorded from the flow cells containing GST-CaV2.2(357-397)WT and GST-CaV2.2(357-397)W391A were corrected for passive refractive index changes and for nonspecific interactions by subtraction of the corresponding sensorgram recorded from the flow cell containing GST only. Sensorgrams were fitted by nonlinear regression using Prism 4 (GraphPad Software San Diego, CA). For each sensorgram, the first 120 s of the association phase and the dissociation phase were fitted to a single exponential to determine the observed association rate kon(obs) and the dissociation rate koff. The specific association rate, kon, was calculated as kon = (kon(obs) - koff)/[CaVβ], and the dissociation constant KD was calculated as KD = koff/kon.

Cell culture and heterologous expression. The tsA-201 cells were cultured in a medium consisting of DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% nonessential amino acids. The cDNAs (all at 1 μg/μl) for CaVα1 subunits, CaVβ, α2δ-2, D2 dopamine receptor, and GFP (when used as a reporter of transfected cells) were mixed in a ratio of 3:2:2:2:0.4. The cells were transfected using Fugene6 (DNA/Fugene6 ratio of 2 μg in 3 μl; Roche Diagnostics, Lewes, UK). The tsA-201 cells were replated at low density on 35 mm tissue culture dishes on the day of recording.

Biotinylation. T75 flasks of transiently transfected tsA-201 cells were washed three times with 10 ml of PBS. Cells were incubated with 2 ml of PBS, pH 8.0, containing 800 μm EZ-link Sulfo NHS-SS-Biotin (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for 15 min at room temperature. The biotinylation reaction was terminated by addition of 10 ml of 100 mm glycine in PBS, and cells were collected by centrifugation (1000 × g) and washed an additional three times with 10 ml of PBS.

Cells were lysed by addition of 750 μl of lysis buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 1.5% Triton X-100) containing one Complete protease inhibitor tablet (Roche Diagnostics) per 10 ml, followed by brief sonication. After centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, the protein concentration of the supernatant was determined using the BCA assay (Pierce). Biotinylated proteins were precipitated by incubating 500 μg of supernatant with 50 μl of streptavidin agarose beads (Pierce) for 3 h at room temperature. Precipitated proteins were washed four times with 1 ml of lysis buffer. Proteins were eluted from the beads by incubation with 100 mm dithiothreitol in lysis buffer for 30 min, followed by an equal volume of 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Samples of supernatant and precipitated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 4-12% Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) followed by Western blotting with anti CaV2.2 II-III linker antibodies (Raghib et al., 2001).

Western blot analysis. Samples (2.5-250 μg of protein) from tsA-201 whole-cell lysates [prepared as described for COS-7 cells by Raghib et al. (2001)] or from biotinylation experiments (see above) were separated by SDS-PAGE on 4-12% Tris-glycine gels and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Immunodetection was performed with antibodies to the Cav2.2 II-III linker (Raghib et al., 2001) or β3 subunit (Canti et al., 2001) as described previously (Raghib et al., 2001).

Immunocytochemistry. Two days after transfection with CaVβ2a or CaVβ2aC3,4S, tsA-201 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5 min at room temperature. For permeabilization, cells were incubated twice for 7 min in a 0.02% solution of Triton X-100 in Tris-buffered saline. For detection of CaVβ2a or CaVβ2aC3,4S, the primary antibody used was a rabbit anti-CaVβ2a (462-600) at 0.2 μg/ml (Chien et al., 1995). The secondary antibody was an anti-rabbit IgG FITC conjugated (1:500; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). For nuclear staining, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (300 nm; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was applied. Samples were mounted in VectaShield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) to reduce photobleaching and examined on a confocal laser scanning microscope (model LSM; Ziess, Oberkochen, Germany) using a 40× objective (1.3 numerical aperture) with constant photomultiplier settings.

Whole-cell electrophysiology. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed at room temperature (22-24°C). Only fluorescent cells expressing GFP were used for recording. The single cells were voltage clamped using an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). The electrode potential was adjusted to give zero current between pipette and external solution before the cells were attached. The cell capacitance varied from 10 to 40 pF. Patch pipettes were filled with a solution containing the following (in mm): 140 Cs-aspartate, 5 EGTA, 2 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 2 K2ATP, and 10 HEPES, titrated to pH 7.2 with CsOH (310 mOsm; with a resistance of 2-3 MΩ). The external solution contained the following (in mm): 150 tetraethylammonium bromide, 3 KCl, 1.0 NaHCO3, 1.0 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 4 glucose, and 10 BaCl2, pH adjusted to 7.4 with Tris base (320 mOsm). The pipette and cell capacitance as well as the series resistance were compensated by 80%. Leak and residual capacitance current were subtracted using a P/4 protocol. Data were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 5-10 kHz. The holding potential was -100 mV, and pulses were delivered every 10 s.

Data analysis and curve fitting. Current amplitude was measured 10 ms after the onset of the test pulse, and the average over a 2 ms period was calculated and used for subsequent analysis. The current density-voltage (I-V) relationships were fitted with a modified Boltzmann equation as follows: I = Gmax × (V - Vrev)/(1 + exp(-(V - V50, act)/k)), where I is the current density (in picoamperes per picofarad), Gmax is the maximum conductance (in nanosiemens per picofarad), Vrev is the reversal potential, V50, act is the midpoint voltage for current activation, and k is the slope factor. Steady-state inactivation properties were measured by applying 5 s pulse from -120 to +20 mV in 10 mV increments, followed by a 11 ms repolarization to -100 mV before the 100 ms test pulse to +20 mV. Steady-state inactivation and activation data were fitted with a single Boltzmann equation of the following form: I/Imax = (A1 - A2)/[1 + exp((V - V50, inact)/k)] + A2, where Imax is the maximal current, and V50, inact is the half-maximal voltage for current inactivation. For the steady-state inactivation, A1 and A2 represent the proportion of inactivating and non-inactivating current, respectively. Inactivation kinetics of the currents were estimated by fitting the decaying part of the current traces with the following equation: I(t) = C + A × exp(-(t - to)/τinact), where to is zero time, C the fraction of non-inactivating current, A the relative amplitude of the exponential, and τinact is its time constant. Activation kinetics were estimated by fitting the activation phase of the current with either a single or a double exponential. Analysis was performed using pClamp6 and Origin 7. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of the number of replicates (n). Error bars indicate SEs of multiple determinations if not otherwise mentioned. Statistical significance was analyzed using Student's paired and unpaired t test, and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

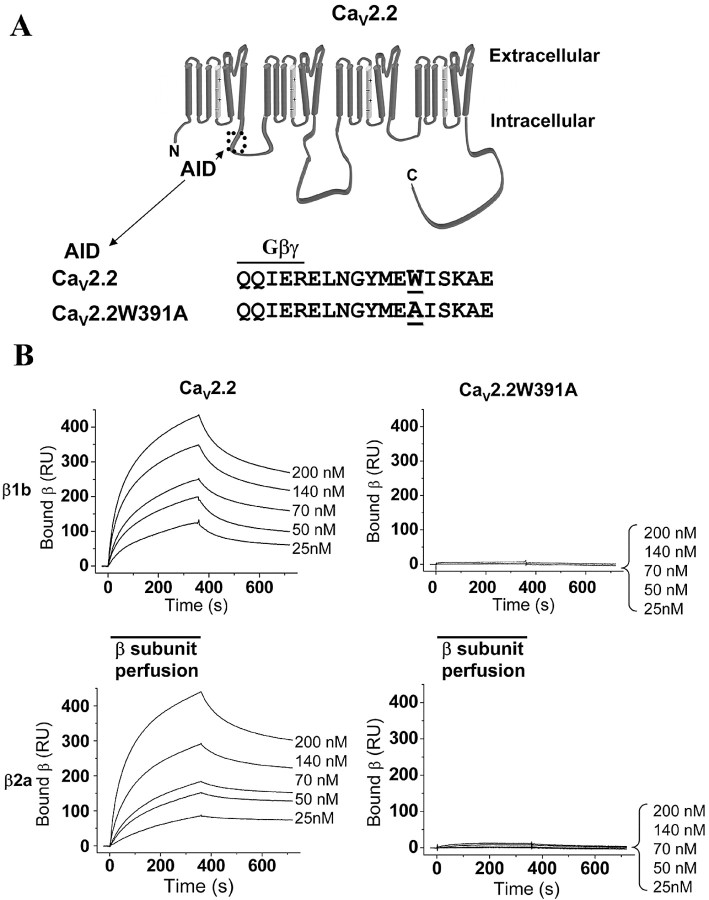

Mutation of W391A in the I-II linker of CaV2.2 disrupts both CaVβ1b and CaVβ2a subunit binding

The amino acid W391 in CaV2.2 (Fig 1A) is conserved in the AID sequence of all HVA calcium channels (for review, see Dolphin, 2003a; Richards et al., 2004) and has been described previously to be important for the binding of the CaVβ ancillary subunits to HVA calcium channels (Pragnell et al., 1994; De Waard et al., 1996; Berrou et al., 2002). The recent structural analysis of the interaction of CaVβ subunits with the CaV1.2 I-II linker showed that this residue is deeply embedded in the AID binding groove in CaVβ (Chen et al., 2004; Opatowsky et al., 2004; Van Petegem et al., 2004). We first showed by surface plasmon resonance analysis that mutation of W391 to A in the AID of CaV2.2 prevents the binding of both CaVβ1b and CaVβ2a subunit to the I-II linker of CaV2.2 (Fig. 1B). In our experiments, GST-fusion proteins corresponding to the proximal I-II linker, including the AID of CaV2.2 or CaV2.2W391A, or GST alone as control, were immobilized via an anti-GST antibody to an individual flow cell of a CM5 dextran sensor chip. CaVβ subunit solutions (25-200 nm) were perfused over all flow cells. No binding of the CaVβ subunits to the control GST-fusion protein was detected (data not shown). CaVβ1b and CaVβ2a exhibited specific binding to the I-II linker of CaV2.2. From the data shown in Figure 1B, the dissociation constants (KD) of CaVβ1b and CaVβ2a for the I-II loop of CaV2.2 were calculated to be 13.8 and 10.3 nm, respectively. Negligible binding of either CaVβ subunit was detected to the mutated CaV2.2W391A I-II linker, and thus the KD values could not be determined. We can only estimate that they must be at least 1000-fold less than for the I-II linker of the wild-type channel. From this assay, we show that the W391 present in the AID is crucial for the binding of CaVβ subunits to the proximal CaV2.2 I-II linker, and that the affinity for β binding to this construct is very similar to that observed previously for the full-length I-II linker (Bell et al., 2001).

Figure 1.

The W391A mutation prevents the binding of CaVβ1b and CaVβ2a to CaV2.2 I-II linker. A, Representation of the CaV2.2 subunit that is composed of four domains of six transmembrane segments each. The I-II linker contains an 18 amino acid domain (AID) that interacts with CaVβ subunits (dotted box). The sequence of the AID within CaV2.2 and CaV2.2W391A are given below, with W391 underlined and also showing the putative overlapping binding motif for Gβγ dimer binding. B, Representative Biacore sensorgrams showing interactions between CaVβ1b (top) or CaVβ2a (bottom) with I-II loop GST-fusion proteins from CaV2.2 (left) and CaV2.2W391A (right). The auxiliary CaVβ subunits (25-200 nm as indicated) were applied during the time indicated by the bars.

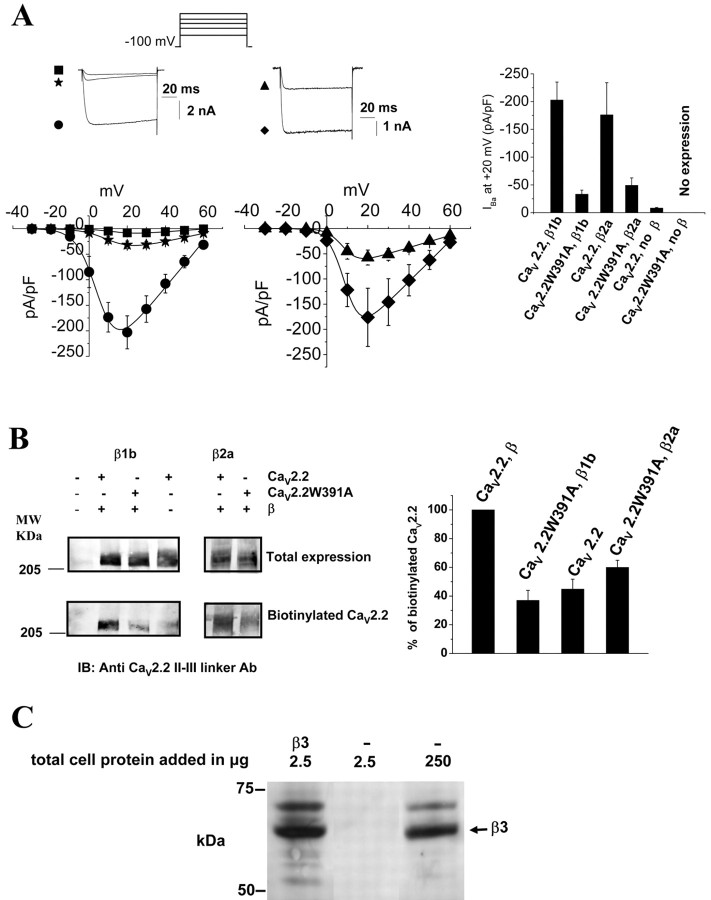

CaVβ subunit binding is essential for functional expression of N-type calcium channels at the plasma membrane

Coexpression of CaV2.2 or CaV2.2W391A with accessory CaVβ subunits allowed us to compare the biophysical properties of the wild-type and mutated channels. The α2δ-2 subunit was additionally present in all conditions in this study. The first striking effect of the W391A mutation was a large reduction of the current density for the mutated channel, consistent with a role of CaVβ binding to the I-II linker in trafficking CaV1 and CaV2 channels to the plasma membrane (Bichet et al., 2000) (Fig. 2A). The Gmax determined from the I-V relationships for CaV2.2W391A with CaVβ1b was significantly decreased by 81 ± 3% compared with the CaV2.2/β1b combination (Fig. 2A; Table 1). The reduction in Gmax was similar (94 ± 0.5%) when the wild-type channel was expressed in the absence of CaVβ (Fig. 2A; Table 1). Similarly, the Gmax was decreased by 72 ± 6% for CaVβ2a with CaV2.2W391A compared with the CaV2.2/β2a combination (Fig. 2A; Table 1). In cells transfected with CaV2.2W391A in the absence of a CaVβ subunit, none of the GFP-positive cells expressed any current (n = 21), whereas at least 90% of the GFP-positive CaV2.2/β1b-transfected cells displayed a current. This strongly suggests that CaV2.2 requires interaction via the I-II linker with a CaVβ to traffic to the plasma membrane.

Figure 2.

Role of CaVβ subunits in plasma membrane expression of CaV2.2. A, Left, I-V relationships for CaV2.2/α2δ-2 coexpressed with CaVβ1b (filled circles, left; n = 18) or CaVβ2a (diamonds, right; n = 13) or without a CaVβ subunit (filled squares, left; n = 13) compared with I-V relationships for CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2 coexpressed with CaVβ1b (filled stars, left; n = 11) or CaVβ2a (filled triangles, right; n = 14). The mean data are fitted with a modified Boltzmann function (see Materials and Methods), the V50, act and Gmax values of which are given in Table 1. Typical Ba2+ current traces at +20 mV (identified by the symbols used) are shown above the I-V relationships. Right, Mean current density at +20 mV for each of these combinations ± SEM. B, Cell surface expression of either CaV2.2 or CaV2.2WA391A expressed with α2δ-2, either without CaVβ or with CaVβ1b (left) or with CaVβ2a (right). Total expression of CaV2.2 is shown by Western blot in the top row and biotinylated CaV2.2 in the bottom row. Cells were transfected with empty vector (lane 1), CaV2.2/α2δ-2/β1b (lane 2), CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2/β1b (lane 3), CaV2.2/α2δ-2 (lane 4), CaV2.2/α2δ-2/β2a (lane 5), or CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2/β2a (lane 6). Note that only the cell surface expression is affected similarly by the W391A mutation or by the absence of CaVβ. Right, Histogram showing quantification of the mean amount of CaV2.2WA391A expressed at the plasma membrane, when coexpressed with either β1b or β2a, or CaV2.2 without CaVβ, given as a percentage of the amount of CaV2.2 expressed with the relevant CaVβ present under the same conditions. Data are mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. MW, Molecular weight. C, Western blot illustrating the endogenous expression of CaVβ3 in tsA-201 cells. Gel loaded with 2.5 μg of protein prepared from cells transfected with CaVβ3 (lane 1) compared with 2.5 or 250 μg of protein from cells transfected with an empty pMT2 vector (lanes 2, 3). An anti-β3 monoclonal antibody was used for immunoblotting.

Table 1.

Biophysical properties of Cav2.2 and Cav2.2W391A

|

|

Maximum conductance (Gmax′ nS/pF) |

Activation V50,act (I-V curves) (mV) |

Activation V50,act (tail currents) (mV) |

Inactivation V50,inact (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Cavb | ||||

| Cav2.2 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | +14.8 ± 1.5 | +24.8 ± 1.7 | −35.1 ± 2.8 |

| n = 13 | n = 8** | n = 6** | ||

| Cav2.2W391A | No expression | |||

| n = 21 | ||||

| Cavβ1b | ||||

| Cav2.2 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | +5.2 ± 1.5 | +13.6 ± 0.7 | −48.6 ± 2.2 |

| n = 18 | n = 19 | n = 11 | ||

| Cav2.2W391A | 0.8 ± 0.02 | +12.8 ± 2.1 | +23.4 ± 1.4 | −35.3 ± 3.5 |

| n = 11** | n = 12** | n = 8** | ||

| Cavβ3 | ||||

| Cav2.2 | 2.9 ± 0.07 | +7.7 ± 0.3 | N/D | −60.8 ± 0.7 |

| n = 7 | n = 6 | |||

| Cav2.2W391A | 0.46 ± 0.03 | +12.2 ± 0.9 | N/D | −32.3 ± 1.6 |

| n = 7** | n = 8** | |||

| Cavβ2a | ||||

| Cav2.2 | 4.0 ± 0.09 | +9.3 ± 0.2 | +20.4 ± 1.5 | +6.8 ± 2.3 |

| n = 13 | n = 10 | n = 17 | ||

| Cav2.2W391A | 1.2 ± 0.04 | +8.37 ± 0.3 | +21 ± 1.5 | +6.2 ± 2.6 |

| n = 14* | n = 12 | n = 18 | ||

| Cavβ2aC3,4 | ||||

| Cav2.2 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | −1 ± 0.5 | +9 ± 2.6 | −44.6 ± 0.4 |

| n = 8 | n = 10 | n = 22 | ||

| Cav2.2W391A | 1.7 ± 0.07 | +7.1 ± 0.7 | +22.5 ± 2.5 | −34.5 ± 3.2 |

| n = 7* | n = 11** | n = 10* | ||

| Cavβ2a/β1b | ||||

| Cav2.2 | 7.1 ± 0.3 | +4.9 ± 0.5 | +19.4 ± 1.5 | −11.6 ± 2.5 |

| n = 11 | n = 14 | n = 17 | ||

| Cav2.2W391A | 1.9 ± 0.08 | +5.6 ± 0.5 | +21.6 ± 1.6 | −17.5 ± 0.6 |

|

|

n = 12**

|

|

n = 14 |

n = 17 |

Statistical significance of the indicated parameter was determined by unpaired t test, comparing data obtained for the wild-type Cav2.2 channels with Cav2.2W391A when coexpressed without or with Cavβ subunits as indicated. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

We used a biotinylation assay to assess biochemically whether there were fewer channels present at the surface of the tsA-201 cells transfected with CaV2.2W391A and a CaVβ subunit or when CaV2.2 was expressed without a CaVβ subunit, compared with wild-type CaV2.2/CaVβ combination. Whereas the total expression of CaV2.2W391A was identical to the expression of CaV2.2 transfected with or without a CaVβ, the amount of biotinylated channels at the plasma membrane was clearly lower (Fig. 2B). The W391A mutation decreased by 62 ± 5 and 37 ± 3% (n = 4) the number of channels that were present at the plasma membrane when coexpressed with CaVβ1b or CaVβ2a, respectively. A similar diminution of the surface expression (by 52 ± 6%) was observed for the wild-type CaV2.2 when expressed without CaVβ (Fig. 2B). Even when the binding of CaVβ subunits to the proximal I-II linker, including the W391A AID, was negligible in vitro, some channels were still able to traffic to the plasma membrane. It is therefore possible that CaVβ subunits can bind to other binding sites present, for example, in the distal I-II linker or on the N and C terminus of the channel as suggested previously (Cornet et al., 2002; Maltez et al., 2005).

Given the foregoing results, the reason for the presence of a low level of wild-type CaV2.2 current in the absence of expressed CaVβ may therefore be the presence of an endogenous β subunit as described previously in Xenopus oocytes (Canti et al., 2001). This was examined by Western blotting using specific CaVβ antibodies. We clearly detected an endogenously expressed CaVβ3 in tsA-201 cells (Fig. 2C). This endogenous CaVβ may be responsible for trafficking wild-type CaV2.2, allowing small currents to be recorded in cells transfected without CaVβ subunits, whereas the much lower affinity of the CaV2.2W391A channel would preclude any interactions with the low level of endogenous CaVβ.

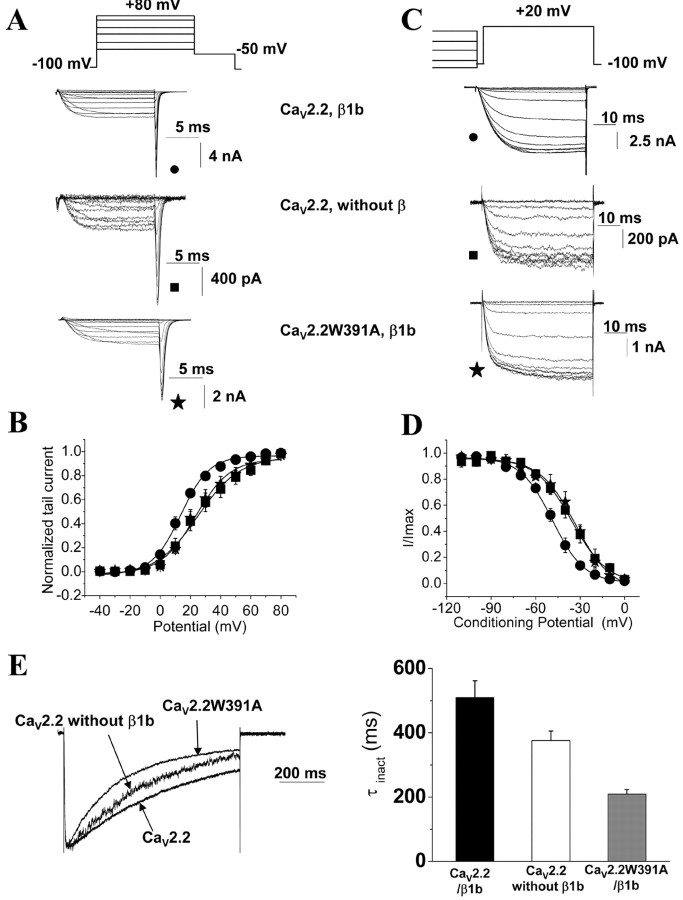

Biophysical properties of CaV2.2W391A expressed with CaVβ1b are similar to those of CaV2.2 expressed without CaVβ

CaVβ1b is known to hyperpolarize the activation and the steady-state inactivation of HVA calcium channels (for review, see Dolphin, 2003a). If the W391A mutation were effectively disrupting the binding of CaVβ1b to the channel, the biophysical properties of CaV2.2W391A should be comparable with those of CaV2.2 expressed without any CaVβ subunit. This was indeed the case, because tail current analysis showed the V50, act to be depolarized by +9.8 and +11.2 mV, respectively, for CaV2.2W391A/β1b and CaV2.2 in the absence of CaVβ compared with CaV2.2/β1b (Fig. 3A,B; Table 1), confirming the V50, act estimates obtained from the I-V relationships (Table 1). This indicated that the W391A mutation abolished the effect of CaVβ1b on the voltage dependence of activation of CaV2.2, such that it behaved like the wild-type channel expressed without a CaVβ subunit.

Figure 3.

Biophysical properties of CaV2.2 and CaV2.2W391A coexpressed with CaVβ1b. A, Representative current traces to illustrate current activation. Ba2+ tail currents were recorded after repolarizing to -50 mV after a 20 ms test pulse to between -40 and +80 mV from a holding potential of -100 mV. Top, CaV2.2/β1b; middle, CaV2.2 without any CaVβ; bottom, CaV2.2W391A/β1b, all coexpressed with α2δ-2. B, Voltage dependence of activation of CaV2.2/α2δ-2 coexpressed with CaVβ1b (filled circles) or without any CaVβ subunit (filled squares) or CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2 expressed with CaVβ1b (filled stars). The normalized data, obtained from recordings such as those shown in A, are plotted against the test pulse (n = 6-19). The mean data are fitted with a Boltzmann function, the V50, act values of which are given in Table 1. C, Representative current traces (labeled as in A) to illustrate steady-state inactivation protocols. Inward Ba2+ currents were recorded after conditioning pulses of 5 s duration, applied from a holding potential of -100 mV in 10 mV steps between -110 and +30 mV, followed by a 50 ms test pulse to +20 mV. D, Voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation of CaV2.2/α2δ-2 coexpressed with CaVβ1b (filled circles) or without any CaVβ subunit (filled squares) or CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2 expressed with CaVβ1b (filled stars). The normalized data obtained from recordings such as those shown in C are plotted against the conditioning potentials (n = 6-19). The mean data are fitted with a Boltzmann function, the V50,inact values of which are given in Table 1. E, Left, Superposition of representative current traces for the subunit combinations indicated, recorded during an 800 ms depolarizing step to +20 mV, from a holding potential of -100 mV, normalized to the peak current. Right, Mean time constants of inactivation (τinact) obtained by fitting the decaying phase of the Ba2+ currents at +20 mV with a single exponential, for CaV2.2/α2δ-2/β1b (black bar; n = 25), CaV2.2/α2δ-2 (white bar; n = 25), and CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2/β1b (gray bar; n = 14).

Another important feature of CaVβ1, β3, and β4 subunits is that they hyperpolarize the steady-inactivation curves of CaV2.2 as well as other HVA calcium channels (Bogdanov et al., 2000). The potential for half-inactivation (V50, inact) was -48.6 mV for CaV2.2 expressed with CaVβ1b (Fig. 3C,D; Table 1). Again, in agreement with the assumption that the I-II linker of the CaV2.2W391A channel does not bind CaVβ1b, we found a significant depolarizing shift of the steady-state inactivation for CaV2.2W391A/β1b [by +13 mV (Table 1)], whose steady-state inactivation curve is superimposed on that of CaV2.2 expressed without CaVβ1b (Fig. 3C,D; Table 1). CaVβ subunits are known to modulate not only the voltage dependence of the inactivation of calcium channels but also the kinetics of current decay (for review, see Dolphin, 2003a). The time constant of inactivation (τinact) of the CaV2.2W391A/β1b current at +20 mV (209.2 ± 14.5 ms; n = 14) was smaller than that of the wild-type CaV2.2/β1b combination (510.3 ± 51.6 ms; n = 25; p < 0.01), whereas the wild-type CaV2.2 expressed without a CaVβ subunit showed intermediate inactivation (Fig. 3E). The faster inactivation kinetics for the CaV2.2W391A/β1b currents might be explained by the introduction of the mutation itself, because it has been shown previously that mutations in the AID are able to alter the inactivation kinetics (Dafi et al., 2004; Berrou et al., 2005).

Altogether, these results indicate that CaV2.2W391A is not regulated by CaVβ1b in the plasma membrane. Furthermore, if, as our evidence suggests, CaV2.2 expressed without CaVβ subunit is trafficked to the plasma membrane by endogenous CaVβ, this CaVβ does not regulate the channels once they have reached the membrane, as suggested previously (Canti et al., 2001).

Differential modulation of N-type channels by CaVβ2a subunits

Despite the fact that the W391A mutation effectively decreased the expression of CaV2.2W391A channels at the plasma membrane in the presence of CaVβ2a as well as CaVβ1b, no shift of activation was observed of the I-V curves when CaVβ2a was coexpressed with CaV2.2W391A compared with the wild-type CaV2.2/β2a combination (Fig. 2A). This was confirmed by analysis of tail currents. The V50, act was equivalent when either CaV2.2 or CaV2.2W391A was coexpressed with CaVβ2a (Fig. 4A,B; Table 1).

Figure 4.

Biophysical properties of CaV2.2 and CaV2.2WA391A coexpressed with CaVβ2a. A, Representative current traces to illustrate current activation using the same protocols as described in the legend to Figure 3. Top, CaV2.2/β2a; bottom, CaV2.2W391A/β2a, all coexpressed with α2δ-2. B, Voltage dependence of activation for CaV2.2/α2δ-2 coexpressed with CaVβ2a (filled diamonds; n = 10) or CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2 expressed with CaVβ2a (filled triangles; n = 12). The normalized data obtained from recordings such as those shown in A are plotted against the test pulse. The mean data are fitted with a Boltzmann function, the V50, act values of which are given in Table 1. C, Representative current traces to illustrate steady-state inactivation using the same protocols as described in the legend to Figure 3. Top, CaV2.2/β2a; bottom, CaV2.2W391A/β2a. D, Voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation for CaV2.2/α2δ-2 coexpressed with CaVβ2a (filled diamonds; n = 17) or CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2 expressed with CaVβ2a (filled triangles; n = 18). The normalized data obtained from recordings such as those shown in C are plotted against the conditioning potentials. The mean data are fitted with a Boltzmann function, the V50, inact values of which are given in Table 1. The dotted line represents the fit for CaV2.2 without CaVβ from Figure 3D. E, Left, Superposition of representative current traces for the subunit combinations indicated, recorded during an 800 ms depolarizing step to +20 mV, from a holding potential of -100 mV and normalized to the peak current. Right, Normalized residual IBa at 600 ms, for CaV2.2/α2δ-2/β2a (black bar; n = 15) and CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2/β2a (gray bar; n = 14).

As expected, CaVβ2a depolarized the V50, inact of CaV2.2 by +42 ± 2 mV compared with CaV2.2 expressed without CaVβ (Fig. 4C,D; Table 1). However, contrary to all expectations, we found that CaVβ2a was also able to depolarize the steady-state inactivation properties of CaV2.2W391A to the same extent as for wild-type CaV2.2 (Fig. 4D; Table 1). Furthermore, CaVβ2a also slowed the inactivation kinetics of CaV2.2W391A currents (Fig. 4E), abolishing the acceleration of the inactivation observed when CaV2.2W391A was coexpressed with CaVβ1b (Fig. 3E), as noted previously for other mutations in the AID region (Dafi et al., 2004). The decay of the currents was <40% during the 800 ms depolarizing pulses and therefore could not be fitted with an exponential function, so we estimated the inactivation rate from the ratio of the current at 600 ms to that at the peak. The ratio at +20 mV was equivalent when CaVβ2a was coexpressed with either CaV2.2 (0.76 ± 0.06) or the mutated channel (0.77 ± 0.08) (Fig. 4E).

In summary, despite the fact that the W391 mutation was able to diminish the trafficking of the CaV2.2W391A channels to the plasma membrane with all of the CaVβ subunits examined and in contrast to the results obtained for CaVβ1b, the CaV2.2W391A/β2a channels expressed at the cell surface were still modulated by CaVβ2a.

Interaction with a CaVβ subunit is essential for the voltage dependence of the modulation of CaV2.2 calcium channels by G-protein activation

To investigate the importance of the W391 residue for the modulation by G-proteins of CaV2.2 calcium channels, we coexpressed a D2 dopamine receptor with the CaV2.2, CaVβ1b, α2δ-2 combination and activated the receptor with a maximal concentration (100 nm) of the agonist quinpirole. Figure 5A shows representative currents obtained before (P1) and immediately after (P2) a 100 ms depolarizing prepulse to +100 mV, before and during application of quinpirole. The currents measured at +10 mV were inhibited by quinpirole by 64.2 ± 4% for the wild-type channel (Fig. 5A, B). The P2/P1 ratio obtained from traces such as those represented in Figure 5A reflects the voltage-dependent loss of inhibition. A value of 2.3 ± 0.1 (n = 18) was obtained for P2/P1 at +10 mV for the wild-type channel expressed with CaVβ1b (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

G-protein modulation of CaV2.2 and CaV2.2W391A expressed with CaVβ1b. Top, The pulse protocol used is depicted. A 100 ms test pulse (P1) from -30 to +60 mV was applied from a holding potential of -100 mV. After 800 ms repolarization to -100 mV, a 100 ms prepulse to +100 mV was applied. The cell was repolarized for 20 ms to -100 mV, and a second pulse (P2) identical to the first one was applied. A, D, Typical current traces obtained with this protocol are represented for CaV2.2 (top) and CaV2.2W391A (bottom) coexpressed with CaVβ1b. In A, the D2 dopamine receptor is coexpressed, and the top current traces (depicted by the open symbols) are in the presence of the agonist quinpirole (100 nm). In D, Gβ1γ2 are coexpressed, and typical traces for CaV2.2/β1b and CaV2.2W391A/β1b are shown. B, I-V curves for the calcium channel combinations are shown, obtained before (filled symbols) and during (open symbols) application of 100 nm quinpirole. Top, I-V curves for CaV2.2/α2δ-2 coexpressed with CaVβ1b (circles; n = 18) Bottom, I-V curves for CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2 coexpressed with CaVβ1b (stars; n = 11) are represented. I-V curves are fitted with modified Boltzmann functions, the V50, act and Gmax parameters of which are given in Table 1. E, Top, I-V curves for Ba2+ currents during P1 for CaV2.2/α2δ-2/β1b coexpressed without (filled circles; n = 6) or with (open triangles; n = 9) Gβ1γ2. Bottom, For CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2/β1b coexpressed without (stars; n = 6) or with (open squares; n = 8) Gβ1γ2. I-V curves obtained from currents recorded during P2 when Gβ1γ2 was coexpressed with CaV2.2/α2δ-2/β1b (filled triangles; n = 9) or CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2/β1b (filled squares; n = 8) are also represented. All data were obtained in parallel on the same experimental days. C, Voltage-dependent facilitation was calculated by dividing the peak current value obtained in P2 by that obtained in P1 at the potentials of 0, +10, and +20 mV, for CaV2.2/α2δ-2 with CaVβ1b (black bars; n = 18), CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2 with CaVβ1b (white bars; n = 11) after application of quinpirole, or when Gβ1γ2 were coexpressed with CaV2.2/β1b (gray bars; n = 9), CaV2.2W391A/β1b (hatched bars; n = 8). F, Typical current traces at +20 mV for R52, 54ACaV2.2W391A (top) coexpressed with CaVβ1b before (filled circles) and after (open circles) activation of the D2 dopamine receptor. Corresponding I-V curves are represented in the bottom.

For the CaV2.2W391A/β1b currents, inhibition by quinpirole was similar, being 58.8 ± 5.2% at +10 mV (n = 11) (Fig. 5A, B). This inhibition was prevented by preincubating the cells for 16 h with 100 ng/ml pertussis toxin (PTX), as was inhibition of the wild-type currents (data not shown). However, the P2/P1 ratio was markedly diminished to 1.3 ± 0.1 at +10 mV (n = 11; p < 0.01) (Fig. 5C), demonstrating a lack of voltage-dependent loss of the G-protein modulation for the mutated channel. In agreement with this, when the CaV2.2W391A/β1b combination was coexpressed with Gβ1γ2, it resulted in tonic inhibition compared with controls in the absence of Gβ1γ2, but these currents exhibited no slowed activation and no prepulse facilitation, in contrast to the wild-type CaV2.2/β1b currents (Fig. 5C-E). Furthermore, although the V50,act of the I-V relationship was depolarized by +12.9 mV for the wild-type channel when Gβ1γ2 were cotransfected, it was only depolarized by +4.5 mV for the CaV2.2W391A channels, in agreement with a reduced voltage dependence of the modulation by Gβγ of CaV2.2W391A channels. Moreover, two arginines (R52 and R54) present in the N terminus of CaV2.2 are essential for the modulation by Gβγ of CaV2.2 calcium channels (Canti et al., 1999). After mutation of these two amino acids to alanines in the N terminus of CaV2.2W391A, quinpirole no longer inhibited the currents. This shows that these residues, and therefore Gβγ, are involved in the voltage-independent inhibition of CaV2.2W391A induced by activation of the D2 dopamine receptor by quinpirole (Fig. 5F).

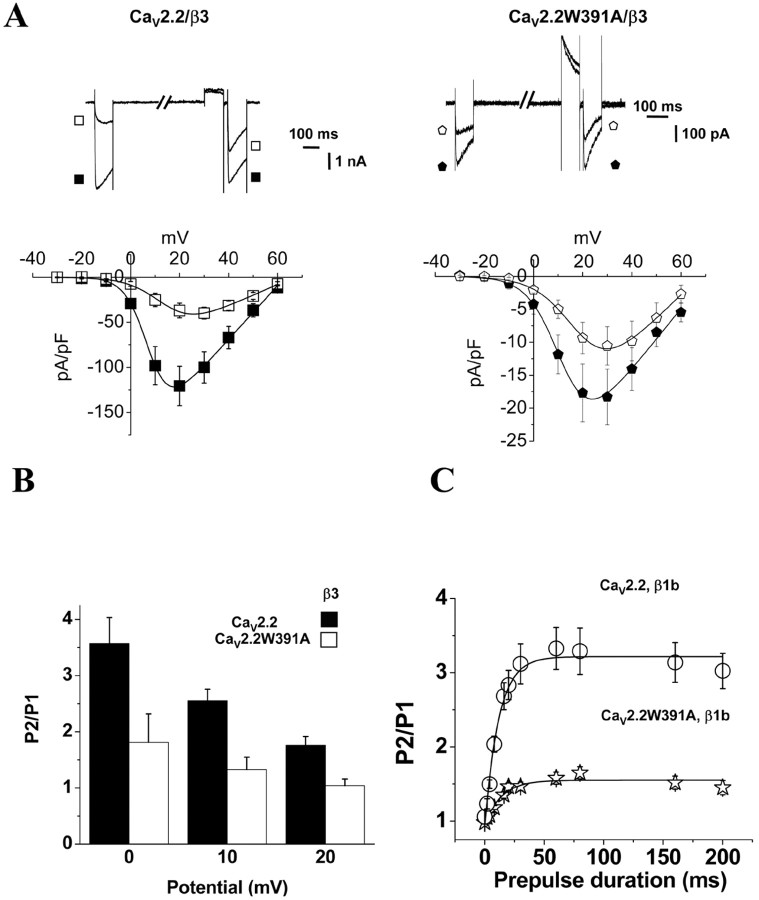

To investigate whether these data were contaminated by the increased inactivation rate of the CaV2.2W391A/β1b combination compared with wild-type CaV2.2/β1b currents, we also examined the quinpirole-mediated inhibition of the wild-type and mutated channels expressed with CaVβ3, which produces more inactivation of wild-type CaV2.2 than does CaVβ1b (Fig. 6A). Unsurprisingly, when CaV2.2W391A was coexpressed with CaVβ3, the Gmax was dramatically reduced by 83 ± 4% compared with wild-type CaV2.2/β3 (Fig. 6A; Table 1). There was also a +4.5 mV shift of the V50, act for CaV2.2W391A compared with wild-type CaV2.2/β3, and the CaVβ3 subunit did not hyperpolarize the steady-state inactivation of CaV2.2W391A (Table 1). This suggests that, like CaVβ1b, CaVβ3 is not able to modulate the biophysical properties of CaV2.2W391A. However, quinpirole still inhibited CaV2.2W391A/β3 currents by 57.8 ± 11.8% at +10 mV (p < 0.01) (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, the voltage-dependent facilitation at +10 mV was greatly diminished from 2.5 ± 0.2 when CaVβ3 was coexpressed with wild-type CaV2.2 to 1.3 ± 0.2 (n = 7; p < 0.01) for the CaV2.2W391A/β3 combination (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

The kinetics of inactivation do not contaminate the properties of G-protein modulation of CaV2.2 and CaV2.2W391A. A, Typical current traces obtained for CaV2.2/α2δ-2 and CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2 coexpressed with CaVβ3 and the D2 dopamine receptor are represented (top). I-V curves obtained for these combinations before (filled symbols) and during (100 nm) application of quinpirole (open symbols) are also shown (bottom). B, Voltage-dependent facilitation for CaV2.2/α2δ-2 (black bars; n = 7) or CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2 coexpressed with CaVβ3 (white bars; n = 7) obtained from the P2/P1 ratio when the D2 dopamine receptor was activated by 100 nm quinpirole. C, Facilitation rate of G-protein-modulated channels. The duration of the prepulse was increased from 0 to 200 ms. The P2/P1 facilitation ratios are given for each prepulse, for CaV2.2 (open circles; n = 16) and CaV2.2W391A (open stars; n = 17) coexpressed with CaVβ1b. Data are fitted with a single exponential, the time constant (τfacil) of which is given in Results.

Although the CaV2.2W391A currents exhibited faster inactivation kinetics than the wild-type currents, the decrease of facilitation observed for the CaV2.2W391A currents was not attributable to inactivation occurring during either P1 or the prepulse, because the facilitation was similar for currents formed from CaV2.2 with either CaVβ1b or CaVβ3, despite the fact that the latter showed accelerated inactivation kinetics (at +20 mV; τinact = 174.1 ± 17.1 ms; n = 7). In addition, at all prepulse durations from 5 to 200 ms, the P2/P1 ratio for the CaV2.2W391A/β1b currents remained markedly reduced compared with CaV2.2/β1b (Fig. 6C). Therefore, the inactivation occurring during the prepulse is not responsible for the apparent decrease in facilitation of CaV2.2W391A. Furthermore, the kinetics of facilitation could be fit to a single exponential, whose time constant (τfacil) for CaV2.2/β1b was 9.0 ± 1.4 ms (Fig. 6C), whereas the small residual facilitation was much slower for the CaV2.2W391A/β1b combination (τfacil = 16.7 ± 3.2 ms). These results indicate that CaVβ accelerates the kinetics of facilitation as described previously (Canti et al., 2000), but also that the presence of a CaVβ subunit, bound with high affinity to the I-II linker of CaV2.2, is essential for the voltage-dependent loss of inhibition, i.e., the ability of a +100 mV prepulse to remove Gβγ-mediated inhibition in P2.

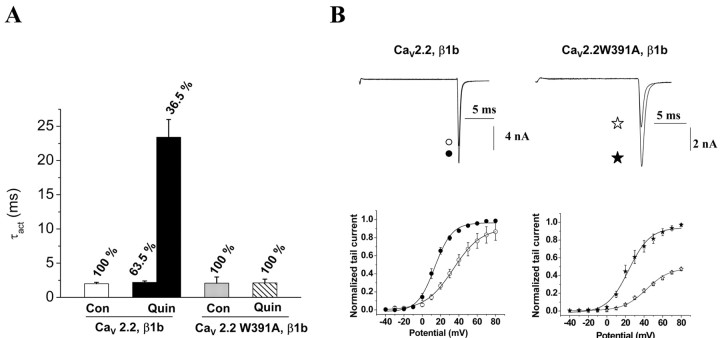

A related characteristic of the G-protein modulation of CaV2 channels is that the kinetics of current activation are slowed. Activation of the D2 dopamine receptor significantly slowed the activation kinetics of CaV2.2 channels coexpressed with CaVβ1b, increasing the time constant of activation (τact) from 2.0 ms to a combination of a similar fast τact,fast (2.2 ms) and a much slower τact,slow of 23.4 ms representing 36.5% of the current (Figs. 5A, 7A). In contrast, the activation kinetics for CaV2.2W391A/β1b measured during a pulse to +10mV were unaffected by quinpirole. τact remained fast both before (2.1 ms) and during (2.1 ms) activation of the receptor (Figs. 5A, 7A).

Figure 7.

G-protein modulation of the kinetics and voltage dependence of activation of CaV2.2 and CaV2.2W391A coexpressed with β1b. A, The τact for currents recorded in P1 as described in Figure 5 before and during perfusion of quinpirole in cells transfected with CaV2.2/α2δ-2/CaVβ1b (white and black bars, respectively; n = 18) and with CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2/β1b (gray and hatched bars, respectively; n = 11). For CaV2.2/α2δ-2/CaVβ1b in the presence of quinpirole, the data were fit by a double exponential with a fast τact and a slow τact, the percentage of each component being given above the bars. B, Activation curves derived from tail current amplitude measurements for CaV2.2/α2δ-2/β1b (left) and CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2/β1b (right). Top, Typical tail current traces recorded after a test pulse to +80 mV before (filled symbols) and during (open symbols) application of 100 nm quinpirole. Bottom, Peak tail current density, before (filled symbols) and during (open symbols) application of quinpirole, for CaV2.2/α2δ-2/β1b (circles, left) or CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2/β1b (stars, right). Data are the mean ± SEM of 12-19 cells, and the solid lines are Boltzmann functions fits, the parameters of which are given in Results.

Another hallmark of G-protein modulation is the depolarization of the voltage dependence of current activation. For the wild-type CaV2.2 coexpressed with CaVβ1b, application of quinpirole induced a +17.5 mV shift of the V50, act, from +14.6 ± 1.8 to +32.1 ± 2.5 mV (n = 19; p < 0.01) (Fig. 7B). This shift was reversible on washout of quinpirole (data not shown). There was no significant inhibition of tail current amplitude at +80 mV (13.5 ± 18.0%), indicating that all of the inhibition was entirely voltage dependent. In contrast, for CaV2.2W391A coexpressed with CaVβ1b, the tail currents were still significantly inhibited by 55.8 ± 11.9% at +80 mV (p < 0.01) (Fig. 7B). However, the V50, act for the residual CaV2.2W391A/β1b was still depolarized by application of quinpirole by +14.9 mV, from +27.5 ± 3.7 to +42.4 ± 1.9 mV (p < 0.01) (Fig. 7B), as was also true for CaV2.2 expressed without a CaVβ subunit (data not shown), possibly indicating that Gβγ can still affect the voltage dependence of gating of CaV2.2W391A by shifting the channel to a reluctant state. Altogether, these results strongly suggest that the loss of ability of CaV2.2W391A to bind CaVβ1b was accompanied by the almost complete loss of voltage dependence of the G-protein modulation of N-type calcium channels.

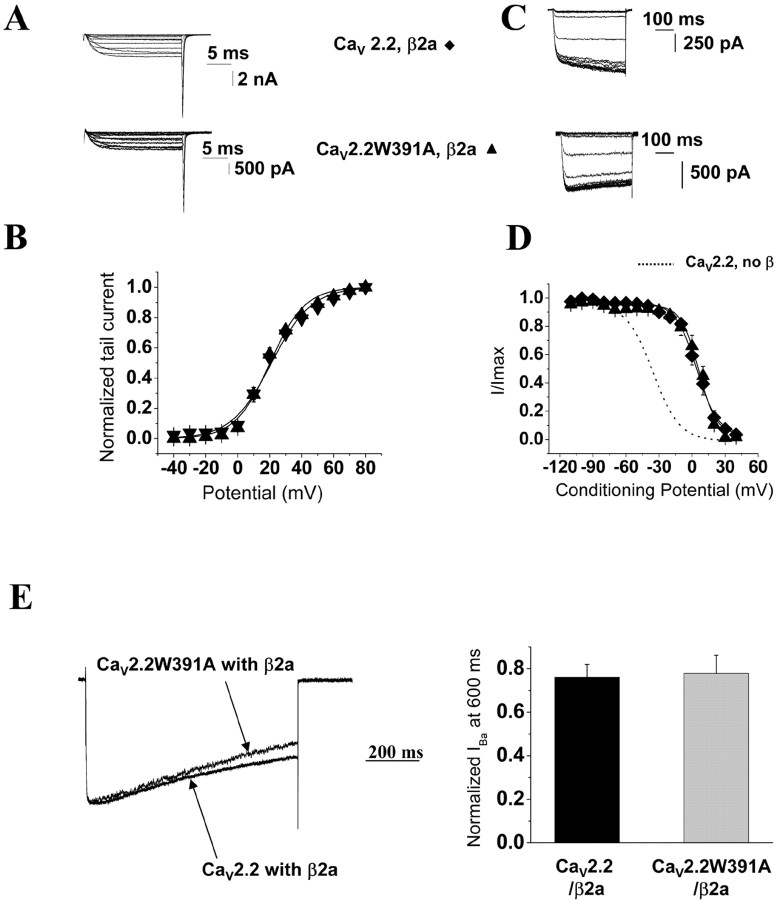

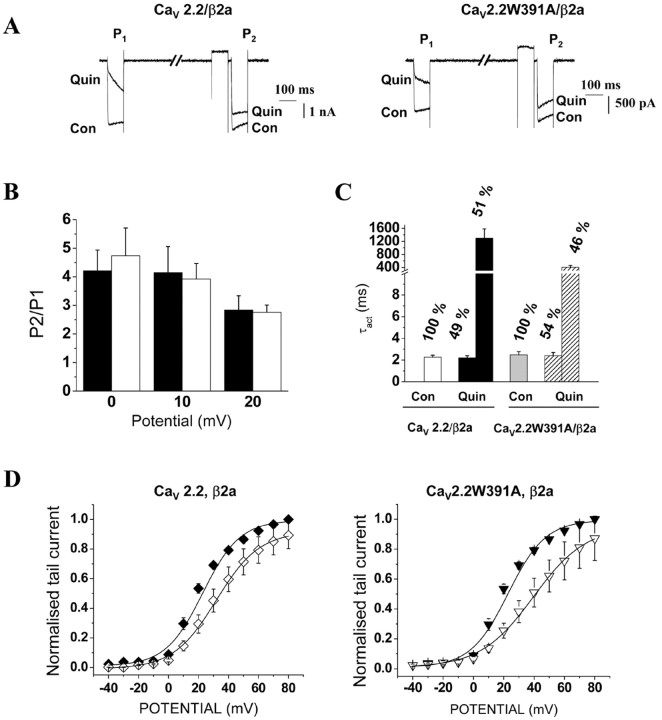

CaV2.2W391A coexpressed with CaVβ2a shows voltage-dependent G-protein modulation

When CaVβ2a was coexpressed with either CaV2.2 or CaV2.2W391A, quinpirole significantly inhibited the currents, by 64.4 ± 6.2% (p < 0.01) and 77.5 ± 6.1% (p < 0.01), respectively (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, in agreement with our evidence that CaV2.2W391A was still associated with CaVβ2a (Fig. 4), we observed voltage-dependent facilitation of the CaV2.2W391A/β2a combination, equivalent to that observed for the wild-type CaV2.2/β2a (Fig. 8A,B). The P2/P1 ratio at +10 mV was 4.3 ± 0.6 for the wild-type channel and 3.7 ± 0.4 for CaV2.2W391A (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

G-protein modulation of the kinetics and voltage dependence of activation of CaV2.2 and CaV2.2W391A coexpressed with CaVβ2a. A, The effect of quinpirole (100 nm) is compared on the CaV2.2/α2δ-2/β2a (left) and CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2/β2a (right) combinations. Representative currents traces using the P1/P2 pulse protocol shown in Figure 5, obtained before (Con) and during (Quin) application of 100 nm quinpirole. B, The P2/P1 facilitation ratios for CaV2.2/α2δ-2/β2a (black bars; n = 13) or CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2/β2a (white bars; n = 14) at potentials between 0 and +20 mV are given. C, The τact values for currents activated by +20 mV steps before and during application of quinpirole. Values are given for CaV2.2/α2δ-2/β2a in control conditions (white bars) and in the presence of quinpirole (black bars; n = 13) or for the CaV2.2W391A (gray and hatched bars, respectively; n = 14). In the presence of quinpirole, the data were fit by two exponentials, with the percentage of the total represented by each component given above the bar. D, Activation derived from normalized tail current density before (filled symbols) and during (open symbols) application of quinpirole (100 nm) for the subunit combination CaV2.2/α2δ-2/β2a (left, diamonds; n = 10) or CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2/β2a (right, triangles; n = 12). The solid lines are Boltzmann function fits to the mean data, the parameters of which are given in Results.

For the CaV2.2/β2a combination, τact was slowed by application of quinpirole from 2.2 ± 0.1 ms to a combination of a similar τact, fast (2.2 ms) and a very slow τact, slow (>400 ms), representing 51% of the current at 100 ms (Fig. 8C). The activation kinetics of CaV2.2W391A were similarly slowed from a τact of 2.4 ± 0.1 ms to a combination of a similar τact, fast (2.4 ms) and a very slow τact, slow (>400 ms), representing 46% of the current at 100 ms (Fig. 8C). From tail currents recorded before and during activation of D2 dopamine receptors, we observed an equivalent shift of V50, act of +12.0 ± 1.7 and +15.6 ± 2.3 mV for CaV2.2 and the mutated channel, respectively (Fig. 8D). At +80 mV, the control tail current amplitude was not significantly greater that that in the presence of quinpirole for CaV2.2W391A/β2a (Fig. 8D), in contrast to the results obtained when CaVβ1b was coexpressed with CaV2.2W391A. We can conclude that CaVβ2a was still able to support voltage-dependent removal of the inhibition of CaV2.2W391A induced by activation of the D2 dopamine receptors.

Palmitoylation is responsible for the ability of CaVβ2a to regulate the voltage-dependent properties of CaV2.2W391A

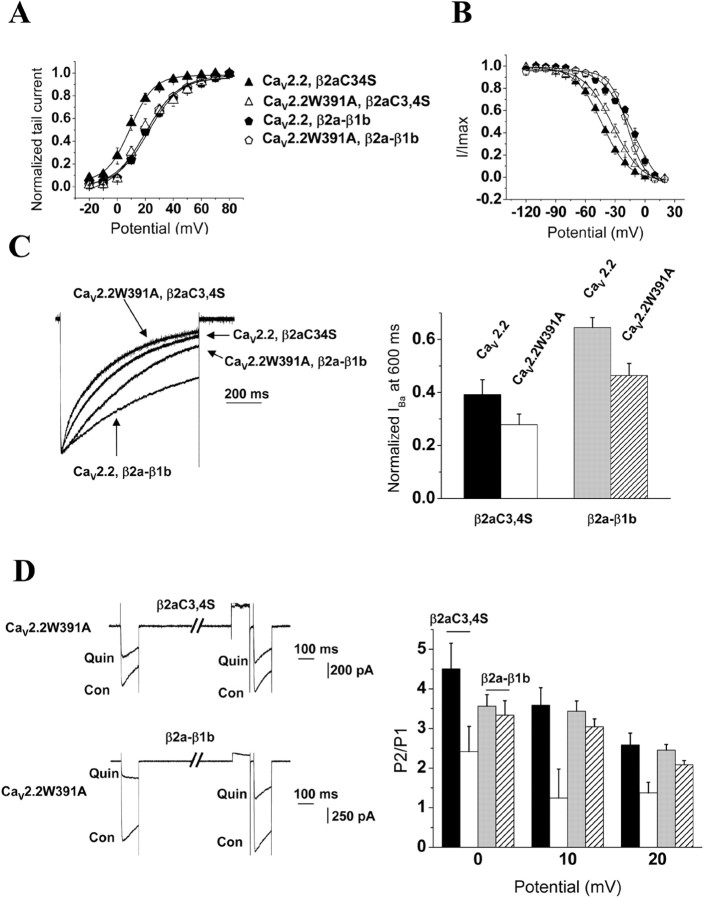

A peculiarity of CaVβ2a is that it contains two cysteines in its N terminus that are palmitoylated. Palmitoylation of these residues strongly modulates the biophysical properties of calcium channels associated with CaVβ2a, particularly their inactivation (Olcese et al., 1994; Chien et al., 1996; Qin et al., 1998; Bogdanov et al., 2000; Hurley et al., 2000; Restituito et al., 2000). To investigate the role of this palmitoylation, we used a CaVβ2a with the cysteines C3 and C4 mutated to serines (CaVβ2aC3,4S) (Bogdanov et al., 2000) that is unable to incorporate palmitate (Qin et al., 1998). Coexpressing CaV2.2 with CaVβ2aC3,4S resulted in a significant hyperpolarization of the tail current V50, act by -11.4 mV compared with CaV2.2/β2a (Fig. 9A; Table 1). The effect of CaVβ2aC3,4S was therefore similar to CaVβ1b. In contrast, when CaVβ2aC3,4S was coexpressed with CaV2.2W391A, the voltage dependence of activation of the channel did not show any hyperpolarizing shift compared with CaV2.2W391A/β2a (Fig. 9A; Table 1), suggesting that, when not palmitoylated, the CaVβ2aC3,4S subunit was not able to modulate the CaV2.2W391A channel.

Figure 9.

Effect of palmitoylation of CaVβ subunits on the modulation of CaV2.2 and CaV2.2W391A channels. A, Voltage dependence of activation of CaV2.2 (filled symbols) or CaV2.2W391A (open symbols) with either CaVβ2aC3,4S (triangles) or CaVβ2a-β1b chimera (pentagons) and α2δ-2. The solid lines are Boltzmann function fits to the mean data, the parameters of which are given in Results. B, Voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation of CaV2.2 (filled symbols) or CaV2.2W391A (open symbols) with either CaVβ2aC3,4S (triangles) or CaVβ2a-β1b chimera (pentagons) and α2δ-2. The solid lines are Boltzmann function fits to the mean data, the parameters of which are given in Results. C, Left, Representative Ba2+ current traces recorded during an 800 ms depolarizing step to +20 mV from a holding potential of -100 mV. Right, The normalized amount of residual current at 600 ms, obtained for CaV2.2 or CaV2.2W391A coexpressed with α2δ-2 and CaVβ2aC3,4S (black and white bars, respectively; n = 18 for both) or the CaVβ2a-β1b chimera (gray and hatched bars; n = 23 and n = 19, respectively). D, Left, The effect of quinpirole (100 nm) is compared for the subunit combinations CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2/β2aC3,4S (top traces) and CaV2.2W391A/α2δ-2/β2a-β1b chimera (bottom traces). Representative currents traces using the P1/P2 pulse protocol shown in Figure 5, obtained before (Con) and during (Quin) application of 100 nm quinpirole. Right, The P2/P1 ratio obtained from such traces for CaV2.2 and CaV2.2W391A coexpressed with α2δ-2 and CaVβ2aC3,4S (black and white bars; n = 7 and n = 8, respectively) or the CaVβ2a-β1b chimera (gray and hatched bars; n = 12 and n = 11 respectively).

As described previously (Qin et al., 1998; Bogdanov et al., 2000; Hurley et al., 2000; Restituito et al., 2000), coexpressing this mutated CaVβ2aC3,4S subunit with CaV2.2 significantly hyperpolarized the steady-state inactivation compared with wild-type CaVβ2a, by -51 mV (Fig. 9B; Table 1), and accelerated the kinetics of inactivation (Fig. 9C). In contrast, the steady-state inactivation V50, inact of the CaV2.2W391A channel coexpressed with CaVβ2aC3,4S was significantly depolarized by >10 mV compared with the inactivation of the CaV2.2 channel in the presence of CaVβ2aC3,4S (Fig. 9B; Table 1), suggesting a lack of modulation of CaV2.2W391A by CaVβ2aC3,4S. As expected, currents recorded from cells expressing CaV2.2W391A with CaVβ2aC3,4S also exhibited fast kinetics of inactivation, similar to those of this channel when coexpressed with CaVβ1b (Fig. 9C).

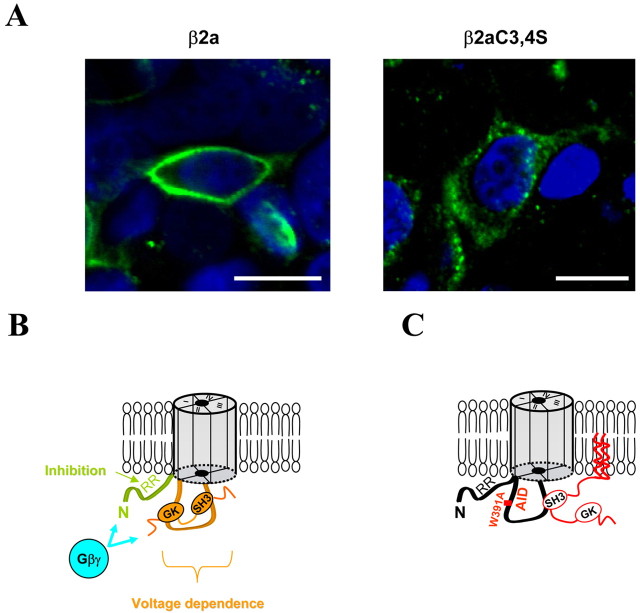

We next determined whether the G-protein modulation of the wild-type CaV2.2/β2aC3,4S combination would be affected by the lack of palmitoylation of the CaVβ subunit. The currents in this case were still inhibited by 58.9 ± 2.6% (n = 8) (Fig. 9D), and the P2/P1 facilitation ratio was 3.5 ± 0.4 at +10 mV, comparable with that for the wild-type channel coexpressed with CaVβ2a (Fig. 9D). However, when this mutated CaVβ2aC3,4S was coexpressed with the mutated CaV2.2W391A, although the currents were still significantly inhibited by activation of the D2 dopamine receptor by 61.4 ± 6.9% (n = 7) (Fig. 9D), the P2/P1 ratio was significantly diminished to 1.2 ± 0.7 at +10 mV (Fig. 9D). These results demonstrate that, when the W391A mutation in the I-II linker of CaV2.2 is accompanied by the mutation of the two palmitoylation sites in the N terminus of CaVβ2a, it abolishes the ability of CaVβ2a to support the voltage dependence of G-protein modulation of the channel. The lack of palmitoylation is confirmed by the altered distribution when expressed in tsA-201 cells, from wild-type CaVβ2a being predominantly membrane associated to diffuse expression throughout the cytoplasm for CaVβ2aC3,4S (Fig. 10A).

Figure 10.

Proposed mechanism for G-protein modulation of CaV2.2 calcium channels and the effect of palmitoylation on the interaction of CaVβ subunits with the I-II linker. A, Confocal immunofluorescent images of β2a and β2aC3,4S subunits expressed in tsA-201 cells, using an anti-β2 antibody (green). Nuclei are visualized with DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 20 μm. Note the membrane localization of the β2a subunit (left), whereas the β2aC3,4S subunit is localized to the cytoplasm (right). B, Model for the mechanism of action of Gβγ binding to the channel to inhibit its activity. The N terminus of CaV2.2 containing two arginines (R52, R54) constitutes a motif implicated in the inhibition by G-proteins, whereas the voltage-dependent facilitation (loss of inhibition induced by strong depolarization) requires a bound CaVβ subunit on the I-II linker. C, The GK domain of CaVβ subunits interacts with the AID, allowing a low-affinity binding of its SH3 domain elsewhere on the channel (e.g., to the I-II loop of CaV2.2) (Maltez et al., 2005) to modulate the properties of the channel. Palmitoylation of CaVβ by anchoring the subunit to the plasma membrane allows this low-affinity interaction to occur when the W391 in the AID is mutated to disrupt its interaction with the GK domain.

To confirm that this property was inherent to the palmitoylation of the CaVβ subunit, we used a chimera in which the N terminus of CaVβ1b was swapped with that of CaVβ2a to obtain a palmitoylatable CaVβ1b (Olcese et al., 1994). The CaVβ2a-β1b chimera was able to depolarize the V50,act of CaV2.2W391A currents (Fig. 9A), similar to CaVβ2a. The chimeric CaVβ2a-β1b subunit also significantly depolarized the steady-state inactivation of both the wild-type CaV2.2 channel and CaV2.2W391A by +37 and +17.8 mV, respectively, compared with channels containing the CaVβ1b subunit with CaV2.2 or CaV2.2W391A (Fig. 9B; Table 1). Furthermore, the chimeric CaVβ2a-β1b subunit slowed the inactivation of the wild-type channel and, to a lesser extent, the mutated CaV2.2W391A (Fig. 9C). Moreover, when coexpressed with CaVβ2a-β1b, CaV2.2W391A currents were modulated by G-protein activation in a voltage-dependent manner (Fig. 9D). CaV2.2W391A exhibited prepulse facilitation during application of quinpirole; the P2/P1 ratio in this case was 3.0 ± 0.2, which was comparable with the value obtained for the wild-type channel expressed with CaVβ2a-β1b (3.4 ± 0.2) (Fig. 9D). Altogether, these results show that the W391 is crucial for the voltage-dependent effects of CaVβ1b and CaVβ3 but not for those of palmitoylated CaVβ2a, because palmitoylation of CaVβ can restore the voltage dependence of modulation of the mutated CaV2.2W391A channel.

Discussion

CaVβ subunits are membrane-associated guanylate-kinase proteins characterized by guanylate kinase-like (GK) domain that binds to the AID motif in the I-II loop of HVA CaVa1 subunits (Fig. 1A) and an Src homology 3 domain (SH3) (Hanlon et al., 1999). The 18 amino acid AID motif contains a conserved tryptophan that is crucial for binding CaVβ (Pragnell et al., 1994; Berrou et al., 2002). Recent structural data from three groups has provided detailed information about the interaction between the AID-CaVβ complex and confirmed that this tryptophan is deeply embedded in the binding groove within the GK of CaVβ (Chen et al., 2004; Opatowsky et al., 2004; Van Petegem et al., 2004).

Requirement of CaVβ for plasma membrane expression of HVA calcium channel

One of the main effects of CaVβ subunits on HVA calcium channels is to increase current density. However, the mechanism for this increase remains controversial, being attributed to increased trafficking (Bichet et al., 2000), increased maximum open probability (Neely et al., 2004), or both. Our data agree with previous studies showing biochemically that the amount of CaV1.2 channels in the plasma membrane was increased by CaVβ subunits (Altier et al., 2002; Cohen et al., 2005). We show that fewer channels are present at the surface when no CaVβ subunits were coexpressed or when the mutated CaV2.2W391A channels were cotransfected with a CaVβ. It has been suggested that a CaVβ bound to the I-II linker may mask an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention signal present in the I-II linker of HVA calcium channels and favor the trafficking of the channel to the cell surface (Bichet et al., 2000). If the trafficking of the channel were the only process affected by the lack of a CaVβ bound to the I-II linker of CaV2.2, the reduction of the current density, as judged by the Gmax, and the amount of CaV2.2 expressed at the plasma membrane would be the same. However, the Gmax was more affected than the plasma membrane expression of CaV2.2 (81 and 62% reduction, respectively, when coexpressed with CaVβ1b). The reason for this is likely to be that CaVβ not only traffics the channel to the surface but also increases the maximum open probability of the channel, as suggested previously (Wakamori et al., 1999; Meir et al., 2000; Neely et al., 2004).

When no CaVβ was coexpressed with wild-type CaV2.2 channels, small currents remained, whereas none of the GFP-positive cells transfected with the mutated CaV2.2W391A channel alone expressed any current. This suggests that the endogenous CaVβ3 that we have identified in tsA-201 cells was responsible for trafficking some wild-type CaV2.2 to the plasma membrane, and that the markedly reduced affinity of the W391A mutated channel for CaVβ subunits prevented interaction with the endogenous CaVβ3 subunits and thus their trafficking to the plasma membrane. When a CaVβ subunit was cotransfected with CaV2.2W391A channel, a small fraction of these channels were then trafficked to the plasma membrane, presumably because the overexpressed CaVβ was able to either bind with low affinity to the mutated I-II linker of CaV2.2W391A or mask other ER retention signals that may be present on other parts of the channel (Cornet et al., 2002). Our results therefore provide very strong evidence that the binding of a CaVβ auxiliary subunit to the channel is an essential requirement for functional expression of CaV2.2 at the plasma membrane.

Role of CaVβ in voltage-dependent modulation of N-type calcium channels

Apart from their important role in trafficking, CaVβ subunits also modify the biophysical properties of calcium channels (for review, see Dolphin, 2003a). Despite our conclusion that interaction with CaVβ (either endogenous or expressed) is essential for trafficking to the plasma membrane, when CaV2.2 was expressed alone, its activation and inactivation properties were shifted to more positive potentials compared with those for CaV2.2 coexpressed with CaVβ1b or CaVβ3. The CaV2.2W391A/β1b or CaVβ3 combinations showed similar biophysical properties to wild-type CaV2.2 channels expressed without a CaVβ. Thus, although the channels required a CaVβ to be trafficked to the plasma membrane, they were not modulated by the CaVβ subunits when inserted in the plasma membrane, in agreement with our previous results suggesting two binding sites with differing affinities (Canti et al., 2001).

G-protein modulation of CaV2.2 calcium channels requires CaVβ subunits to exhibit voltage dependence

Another unexpected feature of our results was that the CaV2.2W391A/β1b currents were still inhibited by D2 dopamine receptor activation to the same extent as wild-type CaV2.2 channels, although there was no voltage-dependent relief of this inhibition. In our experiments, maximal inhibition of the CaV2.2W391A/β1b currents remained fast, occurring within <10 s, and was PTX sensitive. Furthermore, CaV2.2W391A/β1b currents were also tonically inhibited by Gβγ in a voltage-independent manner. We suggest that Gβγ dimers are involved both in the voltage-independent modulation of CaV2.2W391A/β1b currents and in the voltage-dependent modulation of the wild-type CaV2.2 currents.

Two models have been proposed for the regulation of HVA calcium channels by G-proteins. In the first, Gβγ dimers displace CaVβ from the I-II loop, resulting in the reluctant state (Sandoz et al., 2004), whereas in the second model, both Gβγ and CaVβ subunits would be able to bind to the channel at the same time (Meir et al., 2000; Hummer et al., 2003; Richards et al., 2004), with Gβγ binding producing the reluctant state. In the present study, the fact that activating the D2 dopamine receptor still leads to a large inhibition of CaV2.2W391A currents also suggests that the Gβγ has direct effects on channel gating and does not simply displace CaVβ subunits. Moreover, Van Petegem et al. (2004) speculated that, because the Gβγ-AID affinity is at least 10- to 20-fold weaker than the CaVβ-AID affinity and a major conformational change would be required for Gβγ to displace CaVβ, this was unlikely to occur (Van Petegem et al., 2004).

We showed previously that two arginines in the N terminus of CaV2 calcium channels are critical for G-protein modulation (Canti et al., 1999). By mutating these residues in the N terminus of CaV2.2W391A, we demonstrate that they are also critical for the voltage-independent inhibition of the CaV2.2W391A channel, whereas the voltage-dependent removal of this inhibition, or facilitation, involving the unbinding of Gβγ requires CaVβ to be bound to the I-II linker of the channel (Fig. 10B), as suggested previously (Meir et al., 2000).

Palmitoylation of CaVβ2a subunits allows its interaction with CaV2.2W391A

Unlike other CaVβ subunits, palmitoylated CaVβ2a depolarizes, rather than hyperpolarizes, the steady-state inactivation of HVA calcium channels (Jones et al., 1998; Restituito et al., 2000). This observation led to the conclusion that the I-II linker might constitute the inactivation gate of HVA calcium channels, with its mobility being reduced by the palmitoylation of CaVβ2a anchoring it to the plasma membrane (Restituito et al., 2000). In our study, the CaV2.2W391A channels trafficked to the plasma membrane by CaVβ2a remained modulated by this subunit, in contrast to CaVβ1b, and our evidence shows clearly that this is attributable to the palmitoylation of CaVβ2a. The mutated CaVβC3,4S subunit was not able to modulate the biophysical properties of the CaV2.2W391A channels, demonstrating that palmitoylation of CaVβ2a helps to anchor the subunit to the channel. This hypothesis was confirmed by creating a palmitoylatable CaVβ1b that was able to modulate the biophysical properties of the CaV2.2W391A channel.

As shown recently (Cohen et al., 2005; Maltez et al., 2005) and confirmed here, the AID-GK interaction is essential to traffic the channels to the plasma membrane. Our data suggest that either this interaction is not promoted by palmitoylation of CaVβ2a or CaVβ2a is not palmitoylated during the trafficking process, until the CaV2.2/β2a complex is inserted in the plasma membrane.

Short CaVβ subunits that lack the GK domain retain the ability to modulate the open probability of CaV1.2, suggesting another low-affinity binding site on the CaV subunit for the SH3 domain (Cohen et al., 2005). An interaction of the SH3 with the I-II linker has been then demonstrated that modulates biophysical properties of calcium channels such as their inactivation (Maltez et al., 2005). The authors suggest that the role of the high-affinity GK-AID interaction is to increase the local concentration of CaVβ and to promote lower-affinity interactions. In a similar way, palmitoylation of CaVβ2a, promoting its membrane localization (Fig. 10A) and thus increasing its local concentration, may allow its binding to the CaV2.2W391A channel via interaction with low-affinity binding sites, such as the C and N termini or other sites on the I-II linker (Fig. 10C), that might be critical for the voltage-dependent properties of the channel, including the voltage dependence of G-protein modulation (Walker et al., 1999; Stephens et al., 2000; Maltez et al., 2005).

We also show here that, despite differentially affecting the biophysical properties of calcium channels, CaVβ1b and CaVβ2a subunits play the same role in the voltage dependence of G-protein modulation. They are necessary for voltage-dependent facilitation presumably via the second low-affinity site. Our results therefore show conclusively that Gβγ dimers have a direct inhibitory effect on CaV2.2 channel gating, and that CaVβ subunits are required for the voltage-dependent removal of this inhibition.

Footnotes

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust. We thank the following for generous gifts of cDNAs: Dr. Y. Mori (Seriken, Okazaki, Japan) for rabbit CaV2.2, Dr. M. Rees (University College London, London, UK) for mouse α2δ-2, Dr. E. Perez-Reyes (Loyola University, Chicago, IL) for rat β2a, Dr. P. G. Strange (Reading, UK) for rat D2 dopamine receptor, M. Simon (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA) for bovine Gβ1 and Gγ2, Dr. L. Birnbaumer for the β2a-β1b chimera, T. E. Hughes (Yale University, New Haven, CT) for mut-3 GFP, and Genetics Institute (Cambridge, MA) for pMT2. We thank Dr. P. Viard and Dr. K. Page for critical reading of this manuscript. We also thank K. Chaggar and L. Douglas for technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Jérôme Leroy, Laboratory of Cellular and Molecular Neuroscience, Department of Pharmacology, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK. E-mail: j.leroy@ucl.ac.uk.

Copyright © 2005 Society for Neuroscience 0270-6474/05/256984-13$15.00/0

M.S.R. and A.J.B contributed equally to this work.

References

- Altier C, Dubel SJ, Barrere C, Jarvis SE, Stotz SC, Spaetgens RL, Scott JD, Cornet V, De Waard M, Zamponi GW, Nargeot J, Bourinet E (2002) Trafficking of L-type calcium channels mediated by the postsynaptic scaffolding protein AKAP79. J Biol Chem 277: 33598-33603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay J, Balaguero N, Mione M, Ackerman SL, Letts VA, Brodbeck J, Canti C, Meir A, Page KM, Kusumi K, Perez-Reyes E, Lander ES, Frankel WN, Gardiner RM, Dolphin AC, Rees M (2001) Ducky mouse phenotype of epilepsy and ataxia is associated with mutations in the Cacna2d2 gene and decreased calcium channel current in cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Neurosci 21: 6095-6104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean BP (1989) Neurotransmitter inhibition of neuronal calcium currents by changes in channel voltage dependence. Nature 340: 153-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell DC, Butcher AJ, Berrow NS, Page KM, Brust PF, Nesterova A, Stauderman KA, Seabrook GR, Nurnberg B, Dolphin AC (2001) Biophysical properties, pharmacology, and modulation of human, neuronal L-type (α1D, CaV1.3) voltage-dependent calcium currents. J Neurophysiol 85: 816-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrou L, Klein H, Bernatchez G, Parent L (2002) A specific tryptophan in the I-II linker is a key determinant of β-subunit binding and modulation in CaV2.3 calcium channels. Biophys J 83: 1429-1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrou L, Dodier Y, Raybaud A, Tousignant A, Dafi O, Pelletier JN, Parent L (2005) The C-terminal residues in the alpha-interacting domain (AID) helix anchor CaVβ subunit interaction and modulation of CaV2.3 channels. J Biol Chem 280: 494-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichet D, Cornet V, Geib S, Carlier E, Volsen S, Hoshi T, Mori Y, De Waard M (2000) The I-II loop of the Ca2+ channel α1 subunit contains an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal antagonized by the β subunit. Neuron 25: 177-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov Y, Brice NL, Canti C, Page KM, Li M, Volsen SG, Dolphin AC (2000) Acidic motif responsible for plasma membrane association of the voltage-dependent calcium channel β1b subunit. Eur J Neurosci 12: 894-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canti C, Page KM, Stephens GJ, Dolphin AC (1999) Identification of residues in the N terminus of α1B critical for inhibition of the voltage-dependent calcium channel by Gβγ. J Neurosci 19: 6855-6864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canti C, Bogdanov Y, Dolphin AC (2000) Interaction between G proteins and accessory subunits in the regulation of α1B calcium channels in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol (Lond) 527: 419-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canti C, Davies A, Berrow NS, Butcher AJ, Page KM, Dolphin AC (2001) Evidence for two concentration-dependent processes for beta-subunit effects on α1B calcium channels. Biophys J 81: 1439-1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA (2000) Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 16: 521-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YH, Li MH, Zhang Y, He LL, Yamada Y, Fitzmaurice A, Shen Y, Zhang H, Tong L, Yang J (2004) Structural basis of the α1-β subunit interaction of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Nature 429: 675-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien AJ, Zhao X, Shirokov RE, Puri TS, Chang CF, Sun D, Rios E, Hosey MM (1995) Roles of a membrane-localized beta subunit in the formation and targeting of functional L-type Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem 270: 30036-30044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien AJ, Carr KM, Shirokov RE, Rios E, Hosey MM (1996) Identification of palmitoylation sites within the L-type calcium channel β2a subunit and effects on channel function. J Biol Chem 271: 26465-26468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RM, Foell JD, Balijepalli RC, Shah V, Hell JW, Kamp TJ (2005) Unique modulation of L-type Ca2+ channels by short auxiliary β1d subunit present in cardiac muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H2363-H2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornet V, Bichet D, Sandoz G, Marty I, Brocard J, Bourinet E, Mori Y, Villaz M, De Waard M (2002) Multiple determinants in voltage-dependent P/Q calcium channels control their retention in the endoplasmic reticulum. Eur J Neurosci 16: 883-895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dafi O, Berrou L, Dodier Y, Raybaud A, Sauve R, Parent L (2004) Negatively charged residues in the N-terminal of the AID helix confer slow voltage dependent inactivation gating to CaV1.2. Biophys J 87: 3181-3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Waard M, Scott VE, Pragnell M, Campbell KP (1996) Identification of critical amino acids involved in α1-β interaction in voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. FEBS Lett 380: 272-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC (2003a) Beta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels. J Bioenerg Biomembr 35: 599-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC (2003b) G protein modulation of voltage-gated calcium channels. Pharmacol Rev 55: 607-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertel EA, Campbell KP, Harpold MM, Hofmann F, Mori Y, Perez-Reyes E, Schwartz A, Snutch TP, Tanabe T, Birnbaumer L, Tsien RW, Catterall WA (2000) Nomenclature of voltage-gated calcium channels. Neuron 25: 533-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon MR, Berrow NS, Dolphin AC, Wallace BA (1999) Modelling of a voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel beta subunit as a basis for understanding its functional properties. FEBS Lett 445: 366-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlitze S, Garcia DE, Mackie K, Hille B, Scheuer T, Catterall WA (1996) Modulation of Ca2+ channels by G-protein βγ subunits. Nature 380: 258-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer A, Delzeith O, Gomez SR, Moreno RL, Mark MD, Herlitze S (2003) Competitive and synergistic interactions of G protein β2 and Ca2+ channel β1b subunits with CaV2.1 channels, revealed by mammalian two-hybrid and fluorescence resonance energy transfer measurements. J Biol Chem 278: 49386-49400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley JH, Cahill AL, Currie KP, Fox AP (2000) The role of dynamic palmitoylation in Ca2+ channel inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 9293-9298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda SR (1996) Voltage-dependent modulation of N-type calcium channels by G-protein βγ subunits. Nature 380: 255-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LP, Wei SK, Yue DT (1998) Mechanism of auxiliary subunit modulation of neuronal alpha1E calcium channels. J Gen Physiol 112: 125-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltez JM, Nunziato DA, Kim J, Pitt GS (2005) Essential CaVβ modulatory properties are AID-independent. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12: 372-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meir A, Bell DC, Stephens GJ, Page KM, Dolphin AC (2000) Calcium channel β subunit promotes voltage-dependent modulation of α1B by Gβγ. Biophys J 79: 731-746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely A, Garcia-Olivares J, Voswinkel S, Horstkott H, Hidalgo P (2004) Folding of active calcium channel β1b-subunit by size-exclusion chromatography and its role on channel function. J Biol Chem 279: 21689-21694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olcese R, Qin N, Schneider T, Neely A, Wei X, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L (1994) The amino terminus of a calcium channel β subunit sets rates of channel inactivation independently of the subunit's effect on activation. Neuron 13: 1433-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opatowsky Y, Chen CC, Campbell KP, Hirsch JA (2004) Structural analysis of the voltage-dependent calcium channel β subunit functional core and its complex with the α1 interaction domain. Neuron 42: 387-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pragnell M, De Waard M, Mori Y, Tanabe T, Snutch TP, Campbell KP (1994) Calcium channel β-subunit binds to a conserved motif in the I-II cytoplasmic linker of the α1-subunit. Nature 368: 67-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin N, Platano D, Olcese R, Costantin JL, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L (1998) Unique regulatory properties of the type 2a Ca2+ channel β subunit caused by palmitoylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 4690-4695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghib A, Bertaso F, Davies A, Page KM, Meir A, Bogdanov Y, Dolphin AC (2001) Dominant-negative synthesis suppression of voltage-gated calcium channel CaV2.2 induced by truncated constructs. J Neurosci 21: 8495-8504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restituito S, Cens T, Barrere C, Geib S, Galas S, De Waard M, Charnet P (2000) The β2a subunit is a molecular groom for the Ca2+ channel inactivation gate. J Neurosci 20: 9046-9052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards MW, Butcher AJ, Dolphin AC (2004) Ca2+ channel β-subunits: structural insights AID our understanding. Trends Pharmacol Sci 25: 626-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoz G, Lopez-Gonzalez I, Grunwald D, Bichet D, Altafaj X, Weiss N, Ronjat M, Dupuis A, De Waard M (2004) CaVβ-subunit displacement is a key step to induce the reluctant state of P/Q calcium channels by direct G protein regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 6267-6272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens GJ, Page KM, Bogdanov Y, Dolphin AC (2000) The α1B Ca2+ channel amino terminus contributes determinants for β subunit-mediated voltage-dependent inactivation properties. J Physiol (Lond) 525: 377-390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Petegem F, Clark KA, Chatelain FC, Minor DL Jr (2004) Structure of a complex between a voltage-gated calcium channel β-subunit and an alpha-subunit domain. Nature 429: 671-675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamori M, Mikala G, Mori Y (1999) Auxiliary subunits operate as a molecular switch in determining gating behaviour of the unitary N-type Ca2+ channel current in Xenopus oocytes J Physiol (Lond) 517: 659-672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D, Bichet D, Geib S, Mori E, Cornet V, Snutch TP, Mori Y, De Waard M (1999) A new beta subtype-specific interaction in α1A subunit controls P/Q-type Ca2+ channel activation. J Biol Chem 274: 12383-12390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]