Abstract

Recent linkage studies have identified a significant association of the neuregulin gene with schizophrenia, but how neuregulin is involved in schizophrenia is primarily unknown. Aberrant NMDA receptor functions have been implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Therefore, we hypothesize that neuregulin, which is present in glutamatergic synaptic vesicles, may affect NMDA receptor functions via actions on its ErbB receptors enriched in postsynaptic densities, hence participating in emotional regulation and cognitive processes that are impaired in schizophrenia. To test this, we examined the regulation of NMDA receptor currents by neuregulin signaling pathways in prefrontal cortex (PFC), a prominent area affected in schizophrenia. We found that bath perfusion of neuregulin significantly reduced whole-cell NMDA receptor currents in acutely isolated and cultured PFC pyramidal neurons and decreased NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs in PFC slices. The effect of neuregulin was mainly blocked by application of the ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor, IP3 receptor (IP3R) antagonist, or Ca2+ chelators. The neuregulin regulation of NMDA receptor currents was also markedly attenuated in cultured neurons transfected with mutant forms of Ras or a dominant-negative form of MEK1 (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1). Moreover, the neuregulin effect was prevented by agents that stabilize or disrupt actin polymerization but not by agents that interfere with microtubule assembly. Furthermore, neuregulin treatment increased the abundance of internalized NMDA receptors in cultured PFC neurons, which was also sensitive to agents affecting actin cytoskeleton. Together, our study suggests that both PLC/IP3R/Ca2+ and Ras/MEK/ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) signaling pathways are involved in the neuregulin-induced reduction of NMDA receptor currents, which is likely through enhancing NR1 internalization via an actin-dependent mechanism.

Keywords: neuregulin, ErbB receptors, NMDA receptors, schizophrenia, internalization, actin

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a devastating psychiatric disease with high heritability. Recent genome-wide linkage analysis and large-scale profiling of gene expression have implicated the neuregulins (NRGs) and their receptors as the potential susceptibility genes for schizophrenia (Harrison and Owen, 2003; Corfas et al., 2004). The neuregulins constitute a family of proteins coded by four distinct genes (NRG-1 to NRG-4), each of which contains an epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domain (Holmes et al., 1992). The neuregulins signal through three receptors, ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4, that are members of the EGF receptor-related family of tyrosine kinases (Fischbach and Rosen, 1997). Although NRG-1 has been associated with schizophrenia in diverse populations (Stefansson et al., 2002, 2003; Williams et al., 2003), and a significant reduction in the level of ErbB3 expression has been found in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of schizophrenics (Hakak et al., 2001; Tkachev et al., 2003), the mechanisms underlying the involvement of NRG/ErbB in schizophrenia are unclear. One mechanism may be associated with the key role of NRG/ErbB signaling in a spectrum of neurodevelopmental processes in the CNS, including neuronal migration (Anton et al., 1997; Rio et al., 1997), regulation of transmitter receptor expression (Ozaki et al., 1997; Yang et al., 1998; Rieff et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2001), oligodendrocyte development, and myelination (Vartanian et al., 1999; Fernandez et al., 2000). The role of NRG/ErbB signaling in the adult CNS, which could also contribute to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, is primarily unknown.

NRGs and their ErbB receptors are continually expressed in mature brain and accumulate at synapse-rich regions (Pinkas-Kramarski et al., 1994; Corfas et al., 1995; Gerecke et al., 2001), suggesting that NRGs are involved in the maintenance and/or regulation of synaptic structure and function in adult brain. Moreover, it has been found that ErbB4 associates with postsynaptic density-95 (PSD-95) and NMDA receptors (NMDARs) at PSDs of excitatory terminals (Garcia et al., 2000), and PSD-95 enhances NRG signaling by facilitating ErbB4 dimerization (Huang et al., 2000). The colocalization of NMDA and ErbB receptors at PSDs offers the potential for their interactions.

The NMDA glutamate receptor (GluR), which contains an intrinsic ligand-gated ion channel, plays a central role in the regulation of synaptic plasticity. Mounting evidence has suggested that glutamatergic transmission via NMDA receptors is especially involved in schizophrenia (Tsai and Coyle, 2002). Systemic administration of noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonists produces schizophrenia-like behavioral symptoms (Jentsch and Roth, 1999). The expression of NMDA receptor subunits is altered in prefrontal cortex of schizophrenia patients (Akbarian et al., 1996). Therefore, the NMDA receptor is potentially an important target of the NRG/ErbB signaling involved in schizophrenia. In this paper, we demonstrate that NRG, by activating ErbB receptor-mediated signaling pathways, inhibits NMDAR-mediated currents through a mechanism involving the internalization of NMDA receptors that is dependent on actin cytoskeleton.

Materials and Methods

Acute-dissociation procedure and primary neuronal culture. PFC neurons from young adult (3-5 weeks postnatal) Sprague Dawley rats were acutely dissociated using procedures similar to those described previously (Wang et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2004). All experiments were performed with the approval of State University of New York at Buffalo Animal Care Committee. After incubation of brain slices in a NaHCO3-buffered saline, PFC was dissected and placed in an oxygenated chamber containing papain (0.8 mg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in HEPES-buffered HBSS (Sigma) at room temperature. After 40 min of enzyme digestion, tissue was rinsed three times in the low-Ca2+, HEPES-buffered saline and mechanically dissociated with a graded series of fire-polished Pasteur pipettes. The cell suspension was then plated into a 35 mm Lux Petri dish, which was then placed on the stage of a Nikon (Tokyo, Japan) inverted microscope.

Rat PFC cultures were prepared as described previously (Wang et al., 2003). Briefly, PFC was dissected from 18 d rat embryos, and cells were dissociated using trypsin and trituration through a Pasteur pipette. The neurons were plated on coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine in DMEM with 10% fetal calf serum at a density of 1 × 105 cells/cm2. When neurons attached to the coverslip within 24 h, the medium was changed to Neurobasal with B27 supplement. Neurons were maintained for 2-3 weeks before being used for recordings.

Whole-cell recordings. Recordings of whole-cell ligand-gated ion channel currents used standard voltage-clamp techniques (Wang et al., 2003; Tyszkiewicz et al., 2004). The internal solution consisted of the following (in mm): 180 N-methyl-d-glucamine, 40 HEPES, 4 MgCl2, 0.1 BAPTA, 12 phosphocreatine, 3 Na2ATP, 0.5 Na2GTP, 0.1 leupeptin, pH 7.2-7.3, 265-270 mOsm/L. The external solution consisted of the following (in mm): 127 NaCl, 20 CsCl, 10 HEPES, 1 CaCl2, 5 BaCl2, 12 glucose, 0.001 TTX, 0.02 glycine, pH 7.3-7.4, 300-305 mOsm/L. Recordings were obtained with a Molecular Devices (Union City, CA) 200B patch-clamp amplifier that was controlled and monitored with an IBM personal computer running pClamp (version 8) with a DigiData 1320 series interface (Molecular Devices). Electrode resistances were typically 2-4 MΩ in the bath. After seal rupture, series resistance (4-10 MΩ) was compensated (70-90%) and periodically monitored. The cell membrane potential was held at -60 mV. The application of NMDA (100 μm) evoked a partially desensitizing inward current. NMDA was applied for 2 s every 30 s to minimize desensitization-induced decrease of current amplitude. Peak values were measured for generating the plot as a function of time and drug application. Drugs were applied with a gravity-fed “sewer pipe” system. The array of application capillaries (inner diameter, ∼150 μm) was positioned a few hundred micrometers from the cell under study. Solution changes were effected by the SF-77B fast-step solution stimulus delivery device (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT).

A glutathione S-transferase fusion protein encoding the EGF-like domain of rat NRG-β1 (Fu et al., 1999, 2001) and the full-length class I isoform of NRG-β1 protein (Ozaki et al., 2000) were prepared as described previously. Actin agents latrunculin B (lat B), cytochalasin D (cyto D), and phalloidin, microtubule agents colchicine and Taxol (Sigma) as well as second-messenger reagents genistein, 1-(6-[(17β-methoxyestra-1,3,5 [10]-trien-17-yl) amino] hexyl)-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione (U73122), 2-aminoethoxy-diphenylborane (2APB), 3-(N-[dimethylamino]propyl-3-indolyl)-4-(3-indolyl)maleimide (Gö6850), 1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(o-aminophenylmercapto) butadiene (U0126), wortmannin, 4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine (PP2), roscovitine, and myristoylated protein kinase A inhibitor amide 14-22 (PKI14-22) (Cal-biochem, La Jolla, CA) were made up as concentrated stocks in water or DMSO and stored at -20°C. Stocks were thawed and diluted immediately before use.

Data analyses were performed with AxoGraph (Molecular Devices), Kaleidagraph (Albeck Software, Reading, PA), Origin 6 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA), and Statview (Abacus Concepts, Calabasas, CA). ANOVA tests were performed to compare the differential degrees of current modulation between groups subjected to different treatments. The dose-response data were fitted with the following equation:  , where R is the percentage reduction, C is the concentration, τ is the EC50, and S is the slope factor.

, where R is the percentage reduction, C is the concentration, τ is the EC50, and S is the slope factor.

Electrophysiological recordings in slices. To evaluate the regulation of NMDAR-mediated EPSCs by NRG in PFC slices, the whole-cell voltage-clamp recording technique (Wang et al., 2003; Zhong et al., 2003) was used. Electrodes were filled with the following internal solution (in mm): 130 Cs-methanesulfonate, 10 CsCl, 4 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 2.2 N-ethyl bromide quaternary salt, 12 phosphocreatine, 5 MgATP, 0.5 Na2GTP, 0.1 leupeptin, pH 7.2-7.3, 265-270 mOsm/L. The slice (300 μm) was placed in a perfusion chamber attached to the fixed stage of an upright microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) and submerged in continuously flowing oxygenated artificial CSF (ACSF). Cells were visualized with a 40× water-immersion lens and illuminated with near-infrared (IR) light, and the image was detected with an IR-sensitive CCD camera. A Multiclamp 700A amplifier was used for these recordings. Tight seals (2-10 GΩ) from visualized pyramidal neurons were obtained by applying negative pressure. The membrane was disrupted with additional suction, and the whole-cell configuration was obtained. The access resistances ranged from 13 to 18 MΩ and were compensated 50-70%.

For the recording of NMDAR-mediated EPSCs, cells were bathed in ACSF containing CNQX (20 μm) and bicuculline (10 μm) to block AMPA/kainate receptors and GABAA receptors. Evoked currents were generated with a 50 μs pulse from a stimulation isolation unit controlled by a S48 pulse generator (Astro-Med, West Warwick, RI). A bipolar stimulating electrode (FHC, Bowdoinham, ME) was positioned ∼100 μm from the neuron under recording. Before stimulation, cells (voltage clamped at -70 mV) were depolarized to +60 mV for 3 s to fully relieve the voltage-dependent Mg2+ block of NMDAR channels. Application of the NMDAR antagonist d-APV (50 μm) blocked the EPSCs, indicating that these synaptic currents were indeed mediated by NMDA receptors. The Clampfit program (Molecular Devices) was used to analyze evoked synaptic activity. The amplitude of EPSC was calculated by taking the mean of a 2-4 ms window around the peak and comparing with the mean of a 4-8 ms window immediately before the stimulation artifact.

Transfection and small interfering RNA. Cultured PFC neurons [11 d in vitro (DIV)] were transfected with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged dominant-negative (dn) Ras (S17→ N) (Feig and Cooper, 1988) or constitutively active (ca) Ras (G12→ V) (Sweet et al., 1984; Krengel et al., 1990) or cotransfected with a plasmid encoding enhanced GFP (EGFP) and a plasmid containing either the wild-type (wt) MEK1 [MAP (mitogen-activated protein) kinase kinase 1] or the dominant-negative MEK1 (carrying M substitution at K97) construct (Kim et al., 2004). Transfection was conducted with the Lipofectamine 2000 method according to the manual (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). Two to 3 d after transfection, electrophysiological recordings were performed on the GFP-positive neurons.

To suppress the expression of calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) in cultured neurons, we used the small interfering RNA (siRNA), a potent agent for sequence-specific gene silencing (McManus and Sharp, 2002). The siRNA oligonucleotide sequences selected from α-CaMKII mRNA were: 5′-GGAGUAUGCUGCCAAGAUUtt-3′ (sense) and 5′-AAUCUUGGCAGCAUACUCCtg-3′ (antisense). siRNA was synthesized by Ambion (Austin, TX) and cotransfected with EGFP into cultured PFC neurons (11 DIV) using the Lipofectamine 2000 method. Cultures were used 2-3 d after transfection.

Immunocytochemical staining. After treatment, neurons cultured on coverslips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature and washed three times with PBS. Neurons were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, followed by 1 h incubation with 5% bovine serum albumin to block nonspecific staining. Next, neurons were incubated with anti-CaMKII α subunit antibody (1:200; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) or anti-phospho-p44/42 MAP kinase (Thr202/Tyr 204) antibody (1:100; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) at 4°C overnight. After washing off the primary antibodies, the cells were incubated with a rhodamine (or FITC)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200; Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing in PBS for three times, the coverslips were mounted on slides with Vectashield mounting media (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Fluorescent images were obtained using a 100× objective with a cooled CCD camera mounted on a Nikon microscope.

The internalized NR1 subunit of NMDA receptors was detected as described previously (Wang et al., 2003). Briefly, surface NR1 was labeled with a polyclonal anti-NR1 extracellular domain antibody (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) in living cells for 20 min at 37°C in the culture medium. After washing, neurons were treated with neuregulin for 5 min at 37°C. In some experiments, neurons were preincubated with various agents (20 or 60 min before adding neuregulin). Immediately after neuregulin treatment, the antibody that binds to the remaining surface NR1 was striped off with an acid solution (0.5 m NaCl, 0.2N acetic acid) at 4°C for 4 min. Cells were then washed, fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with a monoclonal anti-NR1 antibody (1:200; Upstate Biotechnology) for 2 h at room temperature. The internalized NR1 (labeled with a polyclonal NR1 antibody) was detected with a rhodamine-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody, whereas the total NR1 (labeled with a monoclonal NR1 antibody) was detected with a FITC-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody. Staining of internalized and total GluR1 was done in the same way. Surface GluR1 was labeled with a polyclonal anti-GluR1 extracellular domain antibody (1:50; Oncogene Sciences, Uniondale, NY) in living cells for 20 min. The total GluR1 was labeled with a monoclonal anti-GluR1 antibody (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Labeled cells were imaged using a 100× objective with a cooled CCD camera mounted on a Nikon microscope. All specimens were imaged under identical conditions and analyzed using identical parameters. Levels of internalized and total NR1 or GluR1 immunoreactivity on the same length of dendrites and the same area of somas in cells treated with various agents were compared using Image J software and normalized to the immunoreactivity of untreated neurons. The internalized-to-total ratio was determined by dividing the computed red fluorescence (internalized) by the green fluorescence (total). Two controls were done for measuring the basal level of internalized receptors, namely 0 min control (cells were subjected to acid stripping immediately after antibody labeling) and 5 min control (cells were subjected to acid stripping 5 min after antibody labeling). Three to four independent experiments for each of the treatments were performed. On each coverslip, the immunofluorescence intensity of four to six neurons was quantified. For each neuron, the immunoreactivity of soma (within a 15 × 15 μm area) and three to four neurites (50 μm each) were measured. Quantitative analyses were conducted blindly (without knowledge of experimental treatment).

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting. Cultured PFC neurons (2 × 106 cells) were treated with neuregulin or vehicle for 5 min and then collected and homogenized in 500 μl of lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 50 mm NaPO4, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 50 mm NaF, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 1 mm PMSF, and 1 mg/ml leupeptin). Lysates were centrifuged at 4°C at 16,000 × g, and supernatant fractions were incubated with antibodies against NMDA receptor subunits (4 μl each; Upstate Biotechnology) for 1 h at 4°C, followed by incubation with protein A/G plus agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at the same condition. Immunoprecipitates were washed for three times with the lysis buffer and then boiled in 2× SDS loading buffer for 5 min and separated on 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Western blotting was performed using the ECL method according to the manufacturer's protocol (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Antibodies used for blotting include the following: anti-phospho-p44/42 MAP kinase (Thr202/Tyr 204) (1:1000), anti-NR1 (1:5000), anti-NR2A (1:1000), anti-NR2B (1:1000), and anti-p-tyrosine (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Quantitation was obtained from densitometric measurements of immunoreactive bands on films.

Results

Activation of neuregulin signaling reduces NMDAR-mediated currents in PFC pyramidal neurons

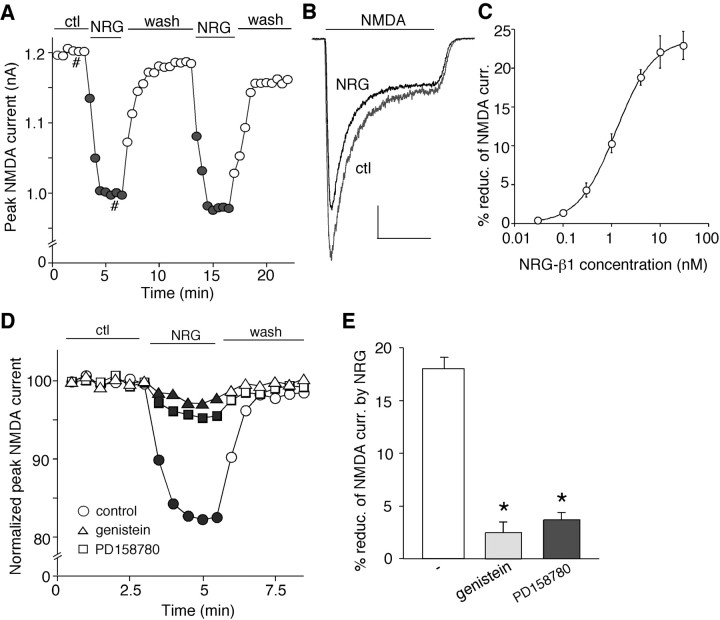

To test whether NMDA receptor is a potential target of the neuregulin signaling, we examined the effect of NRG on NMDA receptor-mediated currents in PFC pyramidal neurons. Because the structure and function of NRG-1 have been characterized extensively (Holmes et al., 1992; Ozaki et al., 1997; Yang et al., 1998), and the gene encoding NRG-1 has been identified as a potential susceptibility gene for schizophrenia (Corfas et al., 2004), we used a recombinant polypeptide containing the EGF domain of the β-type NRG-1 (hereafter referred to as NRG) in this study. Whole-cell recordings of NMDA (100 μm)-evoked ionic currents in dissociated or cultured PFC pyramidal neurons (Wang et al., 2003, Tyszkiewicz et al., 2004) were first performed. As shown in Figure 1, A and B, bath application of NRG (4 nm) reversibly reduced the amplitude of NMDAR currents. After recovery, the second application of NRG produced a similar reduction of NMDAR currents. Dose-response experiments (Fig. 1C) show that different concentrations of NRG inhibited NMDR currents to different extents (1 nm: 10.3 ± 1.2%, n = 8; 4 nm: 18.8 ± 1.0%, n = 10; 10 nm: 22.4 ± 2.7%, n = 6; 100 nm: 22.6 ± 2.0%, n = 5), and the EC50 was ∼1.2 nm. The full-length NRG-β1 protein (5 nm) gave a similar effect, inhibiting NMDAR currents by 17.3 ± 0.5% (n = 7).

Figure 1.

Neuregulin reversibly reduced NMDA receptor currents in PFC pyramidal neurons. A, Plot of peak NMDAR current showing that bath application of the polypeptide containing the EGF domain of NRG-β1 (NRG; 4 nm) decreased NMDA (100 μm)-elicited ionic currents in a dissociated neuron. B, Representative current traces taken from the records used to construct A (at time points denoted by #). Calibration: 0.2 nA, 1 s. C, Dose-response data showing the percentage of reduction (reduc.) of NMDAR currents (curr.) by different concentrations of the EGF domain of NRG-β1. Error bars represent SEM. D, Plot of normalized peak NMDAR currents showing that the broad-spectrum tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein (20 μm) or the more specific ErbB inhibitor PD158780 (1 μm) mainly blocked the NRG reduction of NMDAR currents. E, Cumulative data (mean ± SEM) showing the percentage reduction (reduc.) of NMDAR currents (curr.) by NRG (4 nm) in the absence (-) or presence of genistein or PD158780. *p < 0.01; ANOVA; compared with (-). ctl, Control. Error bars represent SEM.

Because NRG receptors (ErbB2-4) are tyrosine kinases, we then examined whether the broad-spectrum tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein or the more specific ErbB inhibitor 4-[(3-(bromophenyl)-amino]-6-(methylamino)-pyrido[3,4-d]pyridimine (PD158780) (Fry et al., 1997) was able to block the NRG effect on NMDAR currents. As shown in Figure 1D, in the presence of genistein (20 μm) or PD158780 (1 μm), NRG (4 nm) failed to suppress NMDAR currents. In a sample of freshly isolated and cultured PFC neurons (Fig. 1E), NRG produced a significant inhibitory effect on NMDAR currents (18.7 ± 1.4%; n = 80; data pooled together), and this effect of NRG was markedly attenuated by genistein (2.8 ± 0.7%; n = 10) or PD158780 (4.1 ± 0.9%; n = 7).

To determine whether NRG affects synaptic NMDA receptors, we examined the effect of NRG on NMDAR EPSCs in PFC slices. Application of NRG (4 nm) potently reduced the amplitude of NMDAR EPSCs in a reversible manner. The time course and current traces from a representative cell is shown in Figure 2, A and B. In a sample of PFC pyramidal neurons we examined, NRG induced a significant reduction of the mean amplitude of NMDAR EPSCs (36.7 ± 3.7%; n = 8) (Fig. 2E). The bigger effect of NRG found in slices than in dissociated neurons suggests that NRG signaling may preferably affect synaptic NMDA receptors. Thus, NRG had a larger impact on NMDAR EPSCs that were evoked by stimulation of synaptic NMDA receptors than on NMDAR currents in isolated neurons in which both extrasynaptic and synaptic NMDA receptors were stimulated.

Figure 2.

NRG reduced the amplitude, but not the paired-pulse ratio, of NMDAR EPSCs in PFC slices. A, Plot of peak NMDAR EPSCs showing that NRG (4 nm) application reversibly reduced the amplitude of NMDAR-mediated synaptic responses. B, Representative current traces (average of 3 trials) taken from the records used to construct A (at time points denoted by #). Calibration: 50 pA, 0.1 s. C, Plot of peak NMDAR EPSCs evoked by double pulses (interstimuli interval, 100 ms) as a function of time and NRG application. D, Representative traces of NMDAR EPSCs (average of 3 trials) taken from the records used to construct C (at time points denoted by #). Calibration: 50 pA, 0.1 s. E, Cumulative data (mean ± SEM) showing the percentage of change of NMDAR EPSC amplitude and PPR by NRG. ctl, Control.

We further examined the effect of NRG on NMDAR EPSCs evoked by paired pulses, a measure that is sensitive to changes in the probability of transmitter release (Manabe et al., 1993). Consistent with our previous results (Wang et al., 2003), when double pulses with 100 ms intervals were delivered to PFC neurons, the second NMDAR EPSC showed larger amplitude than the first one (a phenomenon called paired-pulse facilitation). Application of NRG reduced the amplitudes of NMDAR EPSC triggered by both pulses (Fig. 2C,D) but did not cause a significant change in the ratio of this paired-pulse facilitation [paired-pulse ratio (PPR); control, 1.52 ± 0.1; NRG, 1.53 ± 0.1; n = 7] (Fig. 2E). This result suggests that activation of NRG signaling is likely to induce a change in postsynaptic NMDA receptors rather than glutamate release.

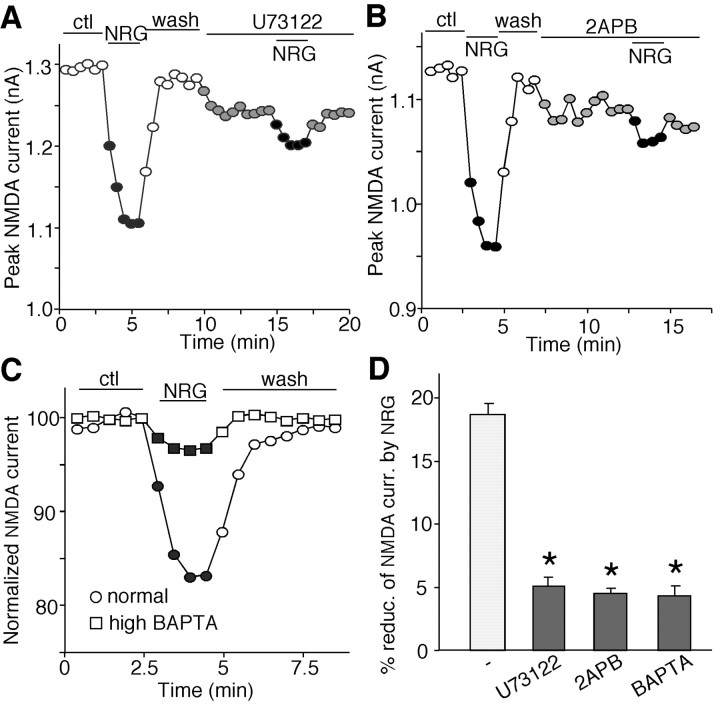

Activation of the phospholipase C/ionsitol-1,4,5-triphosphate/Ca2+ pathway is required for the neuregulin modulation of NMDA receptor currents

We next examined the signaling mechanism underlying the reduction of NMDAR currents by NRG. Because one of the common intracellular signaling molecules that can be activated by receptor tyrosine kinases is the γ-isozymes of phospholipase C (PLC) (Exton 1996), we first tested the role of PLC pathway in the NRG modulation of NMDAR currents. As shown in Figure 3A, application of the PLC inhibitor U73122 (1 μm) significantly blocked the NRG-induced decrease of NMDAR currents, suggesting the involvement of the PLC pathway. PLC activation catalyzes the hydrolysis of membrane phosphoinositol lipids, which leads to the release of ionsitol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol. IP3 binding to IP3 receptors (IP3R) can trigger the release of calcium from internal calcium stores. Thus, we examined the role of Ca2+ in NRG regulation of NMDAR currents. As shown in Figure 3B, 2APB (30 μm), a membrane-permeable IP3R antagonist, substantially blocked the NRG-induced decrease of NMDAR currents. Dialysis with the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA (10 mm) also mostly prevented NRG from decreasing NMDAR currents (Fig. 3C). As summarized in Figure 3D, the effect of NRG on NMDAR currents was significantly (p < 0.01; ANOVA) attenuated in the presence of U73122 (3.9 ± 0.5%; n = 8), 2APB (3.4 ± 0.3%; n = 8), or BAPTA (3.2 ± 0.6%; n = 8). These results suggest that the PLC/IP3/Ca2+ signaling pathway is involved in the NRG regulation of NMDAR currents.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of the PLC/IP3/Ca2+ pathway blocked the NRG reduction of NMDAR currents. A, B, Plot of peak NMDAR currents showing that the PLC inhibitor U73122 (1 μm; A) or the IP3 receptor antagonist 2APB (15 μm; B) essentially blocked the NRG (4 nm) effect on NMDAR currents. C, Plot of normalized peak NMDAR currents showing that dialysis with the high BAPTA (10 mm) internal solution blocked the NRG effect on NMDAR currents. D, Cumulative data (mean ± SEM) showing the percentage reduction (reduc.) of NMDAR currents (curr.) by NRG under various treatments. *p < 0.01; ANOVA; compared with (-). ctl, Control.

CaMKII and PKC are two major downstream signaling molecules that can be activated by the PLC signaling pathway. Previous studies have shown that both kinases are able to modulate NMDA receptors (Leonard et al., 1999; Lan et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2003). We then tested whether they are involved in NRG regulation of NMDAR currents. To examine the role of CaMKII, we suppressed CaMKII protein expression in cultured PFC neurons by transfecting an siRNA directed against CaMKII. GFP was cotransfected with CaMKII siRNA, and the expression of CaMKII was detected with the immunocytochemical approach. We found that in GFP-positive neurons (supplemental Fig. 1A, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), the transfected CaMKII siRNA markedly abolished the expression of CaMKII (top), whereas without CaMKII siRNA, the expression of CaMKII was normal (bottom). Then, we examined the NRG effect on NMDAR currents in CaMKII siRNA-transfected neurons. As shown in supplemental Figure 1B (available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), NRG decreased NMDAR currents in the GFP-positive neuron transfected with CaMKII siRNA to the same degree as in the control neuron transfected with GFP alone. To examine the role of PKC, we inhibited PKC activity by application of the selective PKC inhibitor Gö6850. As shown in supplemental Figure 1C (available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), Gö6850 (1 μm) failed to block the NRG-induced decrease of NMDAR currents. As summarized in supplemental Figure 1D (available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), NRG reduced NMDAR currents by 16.9 ± 1.4% (n = 10) in cultured neurons transfected with CaMKII siRNA, 17.2 ± 1.3% (n = 10) in the presence of Gö6850, neither of which was significantly different from the effect of NRG in control neurons (18.1 ± 0.8%; n = 8). These results suggest that CaMKII or PKC are not involved in the NRG modulation of NMDAR currents.

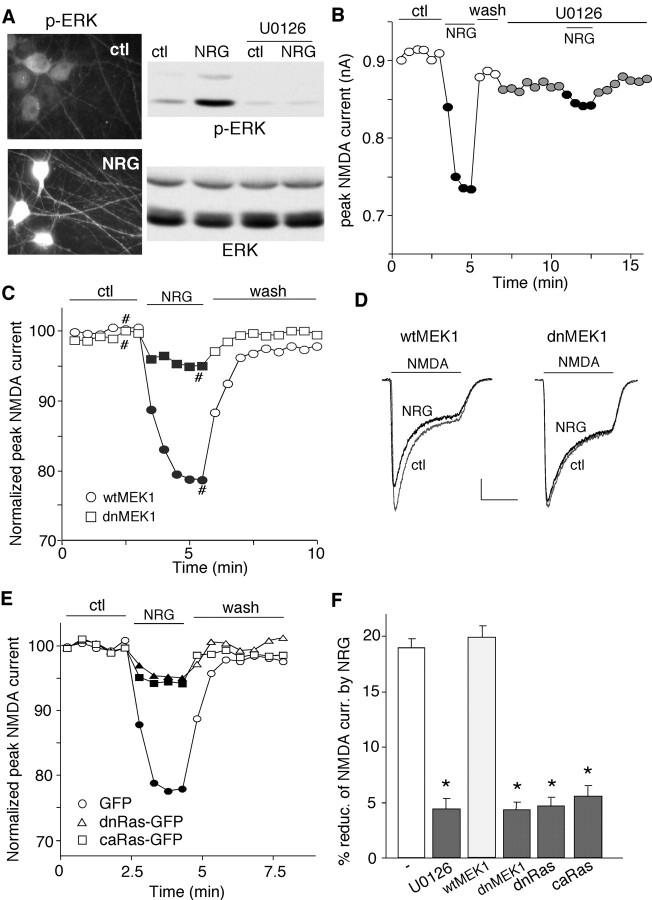

The Ras/MEK/ERK pathway is involved in the neuregulin modulation of NMDA receptor currents

Previous studies have shown that activation of p44/42 MAP kinase [ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase)] is essential for NRG-mediated expression of acetylcholine receptors at the neuromuscular junction (Si et al., 1996; Tansey et al., 1996; Altiok et al., 1997), we then examined the involvement of ERK signaling in NRG modulation of NMDAR currents. Immunocytochemical staining and Western blotting analysis indicated that NRG treatment of cultured PFC neurons induced a strong increase in ERK phosphorylation (Thr202/Tyr 204) and activation (Fig. 4A), which was blocked by U0126 (20 μm), a specific inhibitor of MEK (the upstream kinase of ERK). Application of U0126 (20 μm) significantly blocked the NRG-induced decrease of NMDAR currents (Fig. 4B), suggesting the involvement of ERK. To further confirm it, we blocked the ERK signaling by overexpressing a dominant-negative mutant of MEK1 that is catalytically inactive (Mansour et al., 1994). As shown in Figure 4, C and D, in the neuron transfected with dnMEK1, NRG showed little effect on NMDAR currents, whereas in the neuron transfected with wt-MEK1, NRG produced a significant reduction of NMDAR currents.

Figure 4.

The Ras/MEK/ERK pathway was involved in the NRG reduction of NMDAR currents. A, Immunocytochemical staining (left) and Western blotting (right) showing that application of NRG (4 nm, 2 min) markedly increased phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK) in cultured PFC neurons. Incubation with the MEK inhibitor U0126 (20 μm, 5 min) abolished the NRG-induced increase of p-ERK. B, Plot of peak NMDAR currents showing that U0126 (20 μm) prevented NRG from suppressing NMDAR currents. C, Plot of normalized peak NMDAR currents as a function of time and NRG application in GFP-positive neurons cotransfected with either dnMEK1 or wtMEK1. D, Representative current traces taken from the records used to construct C (at time points denoted by #). Calibration: 0.2 nA, 1 s. E, Plot of normalized peak NMDAR currents as a function of time and NRG application in neurons transfected with GFP alone, GFP-tagged dnRas, or GFP-tagged caRas. F, Cumulative data (mean ± SEM) showing the percentage reduction (reduc.) of NMDAR currents (curr.) by NRG under various conditions. *p < 0.01; ANOVA; compared with (-). ctl, Control.

We then tested the involvement of Ras, the upstream molecule of MEK/ERK signaling, in the NRG regulation of NMDAR currents. We transfected neurons with a dominant-negative form of Ras (S17→ N) or a constitutively active form of Ras (G12→ V) in these neurons to prevent the potential activation of Ras by the NRG signaling. As shown in Figure 4E, the NRG effect on NMDAR currents was greatly attenuated in cultured neurons transfected with either dnRas or caRas. As summarized in Figure 4F, in the presence of U0126, NRG reduced NMDAR currents by 4.3 ± 0.9% (n = 12), which was significantly (p < 0.01; ANOVA) smaller than the effect of NRG in control neurons (18.7 ± 0.8%; n = 10). Moreover, NRG produced little effect on NMDAR currents in neurons transfected with dnMEK1 (4.3 ± 0.7%; n = 13), dnRas (4.5 ± 0.7%; n = 14), or caRas (5.4 ± 0.9%; n = 11), which was significantly (p < 0.01; ANOVA) different from the effect of NRG in neurons transfected with wild-type MEK (19.8 ± 1.0%; n = 10). These results suggest that the Ras/MEK/ERK pathway is involved in the NRG reduction of NMDAR currents.

We also examined the potential involvement of several other key molecules that are linked to NRG signaling and can potentially modulate NMDA receptors, including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), Src, and cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (cdk5) (Tansey et al., 1996; Fu et al., 2001; Li et al., 2001; Salter and Kalia, 2004). As shown in supplemental Figure 2A (available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), the NRG-induced reduction of NMDAR currents was intact in the presence of wortmannin (1 μm), a specific PI3K inhibitor. Application of the nonreceptor tyrosine kinase Src inhibitor PP2 (5 μm; supplemental Fig. 2B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) or the specific Cdk5 inhibitor roscovitine (40 μm; supplemental Fig. 2C, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material) also failed to block the NRG-induced reduction of NMDAR currents. The effect of NRG on NMDAR currents in the absence or presence of various inhibitors is summarized in supplemental Figure 2D (available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Comparing to the effect in control neurons (18.4 ± 1.1%; n = 8), NRG produced a similar reduction of NMDAR currents in the presence of wortmannin (16.4 ± 0.9%; n = 9), PP2 (18.4 ± 0.9%; n = 8), roscovitine (16.4 ± 2.2%; n = 8), or the PKA inhibitor PKI14-22 (0.1 μm; 18.6 ± 2.0%; n = 8), suggesting the lack of involvement of PI3K, Src, Cdk5, or PKA in the regulation of NMDAR currents by neuregulin.

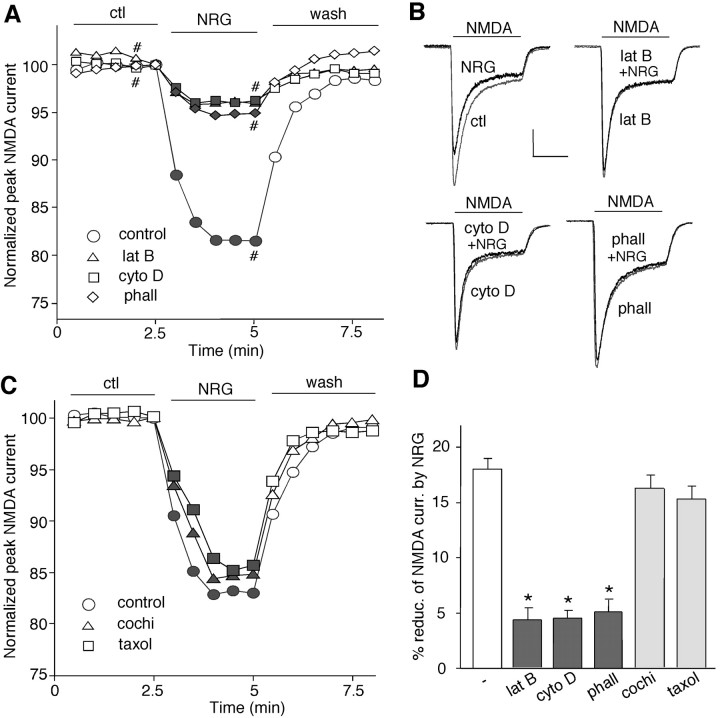

The neuregulin modulation of NMDA receptors is dependent on the integrity of actin

Emerging evidence has suggested that the trafficking of NMDA receptors plays an important role in regulating the function of these channels at the cell membrane (Carroll and Zukin, 2002; Wenthold et al., 2003). Cytoskeleton proteins, such as actin and microtubule, are often critically involved in the trafficking of membrane receptors (Rogers and Gelfand, 2000). To determine whether the neuregulin modulation of NMDAR currents is affected by the integrity of filamentous actin (F-actin) (Rosenmund and Westbrook, 1993), we examined the effect of NRG on NMDAR currents in the presence of agents that interfere with actin filaments. Application of the actin-depolymerizing agent latrunculin B (5 μm, 20 min) or cytochalasin D (5 μm, 20 min) reduced NMDAR currents (lat B: 21.8 ± 4.2%, n = 8; cyto D: 19.5 ± 3.7%, n = 8), consistent with previous results (Rosenmund and Westbrook, 1993). In the presence of latrunculin B or cytochalasin D, subsequent application of NRG had no additional effect on NMDAR currents (Fig. 5A, B). Dialysis with the F-actin stabilizer phalloidin (2 μm) also essentially blocked the effect of NRG (Fig. 5A, B). On the other hand, the NRG effect on NMDAR currents was not affected by the microtubule depolymerizer colchicine (30 μm) or the microtubule stabilizer Taxol (10 μm) (Fig. 5C). As summarized in Figure 5D, the effect of NRG on NMDAR currents was significantly (p < 0.01; ANOVA) attenuated in the presence of latrunculin B (4.2 ± 1.0%; n = 13), cytochalasin D (4.4 ± 0.8%; n = 8), or phalloidin (4.9 ± 1.1%; n = 9) but not colchicine (16.4 ± 1.2%; n = 10) or Taxol (15.8 ± 1.2%; n = 10). These results suggest that the neuregulin regulation of NMDAR currents is dependent on the integrity of actin cytoskeleton rather than microtubule network.

Figure 5.

The NRG effect on NMDAR currents was dependent on actin cytoskeleton but not microtubule. A, Plot of normalized peak NMDAR currents showing that the NRG effect on NMDA currents was markedly attenuated by the actin-depolymerizing agent latrunculin B (5 μm) or cytochalasin D (5 μm) and by the actin stabilizer phalloidin (2 μm; added to the internal solution). B, Representative current traces taken from the records used to construct A (at time points denoted by #). Calibration: 0.2 nA, 1 s. C, Plot of normalized peak NMDAR currents showing that the microtubule depolymerizer colchicine (30 μm) or the microtubule stabilizer Taxol (10 μm) failed to affect the NRG modulation of NMDAR currents. D, Cumulative data (mean ± SEM) showing the percentage of reduction (reduc.) of NMDAR currents (curr.) by NRG in the presence of various chemicals that interfere with actin or microtubule stability. *p < 0.01; ANOVA; compared with (-). ctl, Control; phall, phalloidin; cochi, colchicine.

Neuregulin increases NMDA receptor internalization through an actin-dependent mechanism

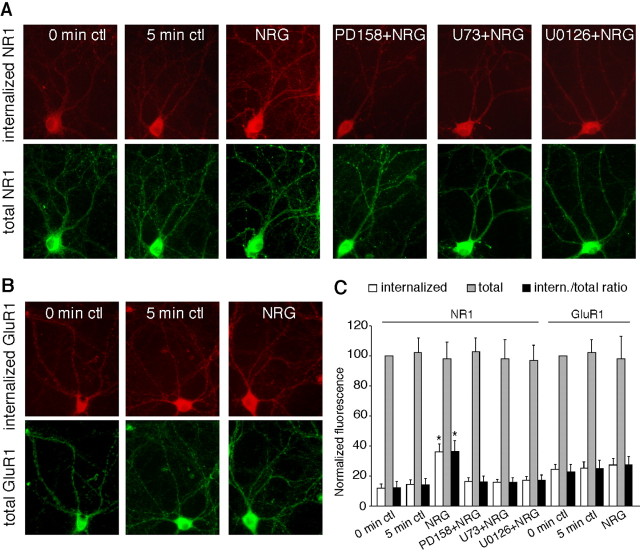

To further confirm the involvement of NMDAR trafficking in the neuregulin regulation of NMDAR currents, we then examined the effect of NRG on NR1 internalization in cultured PFC neurons. As shown in Figure 6A, NRG treatment (5 min) induced a marked increase in internalized NR1 in both cell body and dendrites, compared with both 0 and 5 min control cells (which exhibited similar levels of internalized NR1), whereas the total NR1 was not altered by NRG treatment. Quantification analysis (Fig. 6C) indicated that the ratio of internalized NR1 to total NR1 was 14.1 ± 4.4% (n = 25) in control cells and was increased to 36.5 ± 7.2% (n = 25; p < 0.01; ANOVA) in NRG-treated cells. Application of the specific ErbB inhibitor PD158780 blocked the NRG-induced increase of NR1 internalization [16.2 ± 3.8% (ratio); n = 16] (Fig. 6A, C, PD158780 + NRG), suggesting the mediation through ErbB receptor tyrosine kinases.

Figure 6.

NRG treatment increased NR1 internalization in cultured PFC neurons. A, Immunocytochemical images showing the staining of internalized and total NR1 in representative neurons treated without or with NRG (5 min) in the absence or presence of various agents (20 min preincubation), including the ErbB kinase inhibitor PD158780 (1 μm), PLC inhibitor U73122 (1 μm), or MEK inhibitor U0126 (20 μm). B, Immunocytochemical images showing the staining of internalized and total GluR1 in representative neurons treated without or with NRG. C, Quantitation of internalized, total, and internalized (intern.)/total ratio of NR1 or GluR1 in neurons treated without or with NRG in the absence or presence of various agents. Values are expressed as a percentage of the 0 min control of total NR1 or GluR1. U73, U73122. *p < 0.01; ANOVA; compared with control. Error bars represent SEM. ctl, Control.

We then tested whether the signaling pathways involved in NRG reduction of NMDAR currents were also involved in the NRG increase of NR1 internalization. As shown in Figure 6, A and C, the PLC inhibitor U73122 and MEK inhibitor U0126, both of which blocked NRG reduction of NMDAR currents, also abolished the NRG-induced increase of NR1 internalization [U73122 plus NRG: 15.9 ± 3.2% (ratio), n = 16; U0126 plus NRG: 17.3 ± 3.5% (ratio), n = 16]. U73122 or U0126 alone did not alter the levels of internalized NR1 protein (data not shown). None of these treatments caused any change on total NR1 (Fig. 6A, C). In contrast to the effect of NRG on NR1 internalization, NRG treatment did not alter the AMPA receptor GluR1 subunit internalization or the total level of GluR1 (Fig. 6B, C). The ratio of internalized GluR1 to total GluR1 was 24.8 ± 5.6% (n = 16) in control cells and 27.3 ± 5.7% (n = 16) in NRG-treated cells (Fig. 6C).

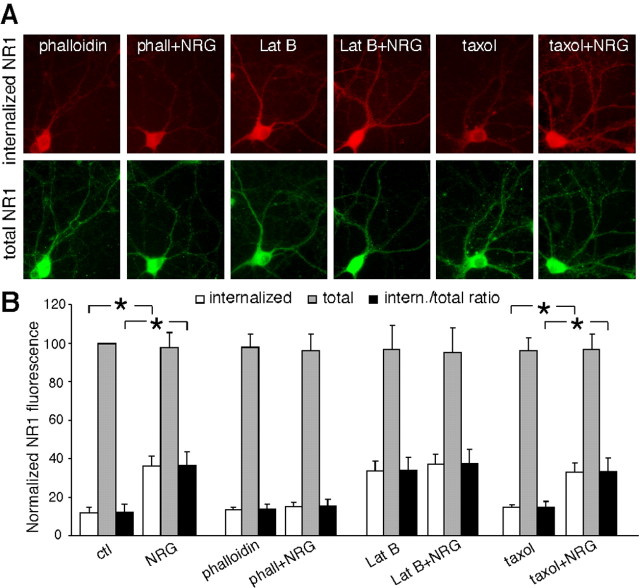

Next, we examined whether the NRG-induced increase of NR1 internalization was affected by agents that interfere with actin or microtubule. As shown in Figure 7, A and B, application of the membrane-permeable actin stabilizer phalloidin oleate (0.5 μm) blocked the enhancing effect of NRG on NR1 internalization [phalloidin: 13.9 ± 2.5% (ratio), n = 18; phalloidin plus NRG: 15.3 ± 3.8% (ratio), n = 18], whereas phalloidin itself did not alter the levels of internalized NR1 protein. The actin-depolymerizing agent latrunculin B itself increased NR1 internalization and occluded the effect of subsequently applied NRG [lat B: 34.1 ± 6.7% (ratio), n = 18; lat B plus NRG: 37.6 ± 7.3% (ratio), n = 18]. Moreover, the NRG effect on NR1 internalization was intact in the presence of the microtubule stabilizer Taxol [Taxol: 14.9 ± 3.1% (ratio), n = 18; Taxol plus NRG: 33.5 ± 6.8% (ratio), n = 18; p < 0.01; ANOVA)], and Taxol alone did not alter NR1 internalization. The level of total NR1 was not changed by any of these treatments (Fig. 7A, B). These results suggest that activation of neuregulin signaling increases NR1 internalization through an actin-dependent mechanism.

Figure 7.

The NRG-induced increase of NR1 internalization was via an actin-dependent mechanism. A, Immunocytochemical images showing the staining of internalized and total NR1 in representative neurons treated without or with NRG (5 min) in the presence of various agents (1 h preincubation), including the actin stabilizer phalloidin oleate (0.5 μm), the actin depolymerizer latrunculin B (5 μm), or the microtubule stabilizer Taxol (10 μm). B, Quantitation of internalized, total, and internalized (intern.)/total ratio of NR1 in neurons treated without or with NRG in the absence or presence of various agents. Values are expressed as a percentage of the 0 min control (ctl) of total NR1. phall, Phalloidin. *p < 0.01; ANOVA. Error bars represent SEM.

Because tyrosine phosphorylation of NMDA receptors regulates the channel activity and trafficking (Wang and Salter, 1994; Vissel et al., 2001), we would like to know whether the NRG modulation of NMDAR currents is through the direct phosphorylation of NMDA receptors by the ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase. Thus, we examined whether NRG treatment altered the tyrosine phosphorylation of NMDA receptor subunits. As shown in supplemental Figure 3, A and B (available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), the tyrosine phosphorylation of NR1, NR2A, and NR2B subunits was not significantly changed by NRG treatment. The total level of NR1, NR2A, and NR2B was also unchanged by NRG treatment. It suggests that the NRG reduction of NMDAR currents is not attributable to the change of NMDA receptor tyrosine phosphorylation.

Because NRG treatment induced NR1 internalization, we further tested whether the internalization is mediated via a clathrin/dynamin-dependent pathway (Vissel et al., 2001; Nong et al., 2003). We tested the effect of NRG on the NMDAR current in cells dialyzed with the dynamin inhibitory peptide QVPSRPNRAP, which competitively blocks binding of dynamin to amphiphysin (Gout et al., 1993) and thus prevents endocytosis when administered intracellularly (Lissin et al., 1998; Kittler et al., 2000). As shown in Figure 8A, when NMDAR endocytosis was inhibited by the dynamin inhibitory peptide (50 μm), NRG failed to suppress NMDAR currents, whereas the effect of NRG was intact in the presence of a scrambled control peptide (50 μm). As summarized in Figure 8B, NRG had significantly smaller effect in neurons dialyzed with the dynamin inhibitory peptide (3.9 ± 0.7%; n = 9), compared with the control peptide (18.9 ± 1.7%; n = 8). These results suggest that the mechanism underlying the NRG-induced downregulation of NMDAR currents is a decrease of functional surface NMDA receptors mediated by clathrin/dynamin-dependent endocytosis.

Figure 8.

The NRG reduction of NMDAR currents was through a mechanism involving the NMDAR internalization mediated by a clathrin/dynamin-dependent pathway. A, Plot of normalized (Norm.) peak NMDAR currents as a function of time and NRG application in neurons dialyzed with the dynamin inhibitory (inh.) peptide (pep; 50 μm) or a scrambled control peptide (50 μm). ctl, Control. B, Cumulative data (mean ± SEM) showing the percentage of reduction (reduc.) of NMDAR currents (curr.) by NRG (4 nm) in neurons injected with the dynamin inhibitory (inh.) peptide (pep.) or a scrambled (scram.) control peptide. *p < 0.01; ANOVA.

Discussion

Neuregulin is present in glutamatergic synaptic vesicles, and ErbB receptors are enriched in the PSD subcellular fraction (Garcia et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2000). Moreover, ErbB4 interacts with PSD-95 in the adult brain and colocalizes with NMDA receptors in neuronal synapses (Garcia et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2000). Therefore, it has been suggested that neuregulin may play a role in modulating NMDAR-dependent synaptic plasticity (Huang et al., 2000; Buonanno and Fischbach, 2001). The potential interactions between NRG and NMDA receptors are further supported by the finding that NRG-1 induces a large increase in the NMDA receptor NR2C subunit mRNA in cerebellar slices (Ozaki et al., 1997). In addition, NRG+/- mice exhibit a significant decrease in the number of functional NMDA receptors in prefrontal cortex (Stefansson et al., 2002). Nevertheless, direct measurement of the impact of NRG/ErbB signaling on NMDA receptor functions has been lacking. In this study, we demonstrate that there exists a functional interaction between NRG/ErbB signaling and NMDA receptors. Activation of the NRG signaling with a polypeptide containing the EGF domain of NRG-β1 produces a significant reduction of the NMDA receptor-mediated ionic currents and synaptic currents in PFC pyramidal neurons.

Because multiple signaling cascades could converge to regulate NMDA receptors, we have examined signaling mechanisms underlying the NRG action. After NRG stimulation, ErbB receptors are homodimerized or heterodimerized, and subsequently, tyrosine residues in the C termini become phosphorylated, which serve as binding sites for cytoplasmic signaling molecules such as the γ-isozymes of PLC (Exton, 1996). Activated PLC will catalyze the hydrolysis of phospholipid, releasing IP3, which mobilizes Ca2+ from intracellular stores, and diacylglycerol, which activates PKC. Our data showed that inhibition of PLC, IP3 receptor, or [Ca2+]i abolished the NRG regulation of NMDAR currents, suggesting the involvement of the PLC/IP3R/Ca2+ signaling pathway in the action of NRG. CaMKII and PKC, two downstream targets of PLC, appear to play no role in this process.

Another important downstream signaling molecule that can be activated by the ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase is the ERK subgroup of MAP kinases. Many studies have shown that activation of ERK is essential for NRG-mediated expression of ACh receptor (AChR) subunits at the neuromuscular junction (Si et al., 1996; Tansey et al., 1996; Altiok et al., 1997). Our data showed that suppression of Ras or ERK activation with dominant inhibitory mutants eliminated the ability of NRG to regulate NMDAR currents, suggesting the involvement of the Ras/MEK/ERK signaling pathway in the action of NRG. Interestingly, expression of a dominant-negative mutant of Ras or a constitutively active Ras mutant both interfered with NRG effects on NMDAR currents. The explanation is as follows. In a normal Ras-GTPase cycle, guanine-nucleotide-exchange factors (GEFs) activate Ras by promoting nucleotide exchange on Ras, and GTPase-activating proteins inactivate Ras by promoting GTP hydrolysis by Ras. The dominant-negative RasS17N mutant blocks activation of endogenous Ras by binding more tightly to RasGEF than does normal Ras (Feig and Cooper, 1988). Because RasS17N cannot engage downstream targets even when bound to GTP, it prevents the formation of functional GTP-bound Ras in cells. On the other hand, the constitutively active RasG12V mutant has deficiency in the GTPase activity (Sweet et al., 1984; Krengel et al., 1990). Because RasG12V is locked at the active state, it prevents any additional activation of Ras in response to stimuli. Thus, if the NRG regulation of NMDAR currents requires the elevation of Ras activity, the effect will be lost in neurons transfected with either form of mutant Ras. Our data have confirmed this hypothesis.

Several other signaling molecules, such as PI3K and cdk5, have also been implicated in the NRG-induced AChR expression (Tansey et al., 1996; Fu et al., 2001). However, inhibition of these kinases did not affect the NRG regulation of NMDAR currents; thus, we ruled out the involvement of these molecules. Interestingly, PSD-95, the postsynaptic protein associated with NMDA receptors (Kornau et al., 1995), regulates NRG-mediated activation of ERK (Huang et al., 2000). It awaits to see whether PSD-95 also facilitates the NRG regulation of NMDA receptor currents.

To understand how the NRG-induced elevation of intracellular Ca2+ and activation of ERK lead to the downregulation of NMDA receptor currents, we examined the role of cytoskeleton dynamics that can be regulated by these intracellular second messengers. F-actin is a major component of the cytoskeleton in postsynaptic densities at glutamatergic synapses (Matus et al., 1982; Allison et al., 1998). It continuously undergoes dynamic remodeling (Fischer et al., 1998, 2000; Matus, 2000) and can be rapidly depolymerized by calcium (Pollard and Cooper, 1986) or activation of ERK (Kutsuna et al., 2004). NMDA receptors are associated with actin filaments via actin binding proteins, such as α-actinin (Wyszynski et al., 1997; Krupp et al., 1999) and spectrin (Wechsler and Teichberg, 1998). The activity of NMDA receptors is dependent on the integrity of F-actin, and actin depolymerization resulting from influx of Ca2+ causes a downregulation of NMDA channel activity (Rosenmund and Westbrook, 1993). Moreover, depolymerizing F-actin causes a 40% decrease of synaptic NMDA receptor clusters (Allison et al., 1998) and a selective depression of NMDAR-mediated synaptic transmission (Sattler et al., 2000). In this study, we found that the NRG-induced decrease of NMDAR currents was prevented by agents interfering with actin filaments but was not affected by microtubule-perturbing agents. It suggests that NRG regulates NMDA receptors via a mechanism depending on the integrity of actin cytoskeleton.

NMDA receptor function can be regulated by at least two mechanisms. One is to change the phosphorylation state of NMDA receptors, thereby altering the biophysical properties of these channels (Wang and Salter, 1994; Westphal et al., 1999). The other is to change the trafficking of NMDA receptors, thereby altering the number of functional channels on the synaptic membrane (Carroll and Zukin, 2002; Wenthold et al., 2003). In this study, we found that NRG induced a significant increase in NR1 subunit internalization in cultured PFC neurons but did not cause a significant change in the tyrosine phosphorylation of NMDA receptor subunits. Consistent with the actin dependence of the NRG effect on NMDAR currents, the NRG regulation of NR1 internalization was also sensitive to agents affecting actin cytoskeleton. Furthermore, electrophysiological data show that the NR1 internalization is mediated via a clathrin/dynamin-dependent pathway. These results suggest that the NRG-mediated downregulation of NMDAR currents could occur through the increased NR1 endocytosis through clathrin-coated pits via an actin-dependent mechanism.

Actin depolymerization has been shown to enhance the internalization of AMPA receptors (Zhou et al., 2001). NMDA receptors, however, are more closely linked to the actin cytoskeleton (Wyszynski et al., 1997; Wechsler and Teichberg, 1998; Krupp et al., 1999). Consistent with our physiological results, other functional studies have also shown that the NMDAR activity is dependent on the state of polymerization of F-actin (Rosenmund and Westbrook, 1993; Lei et al., 2001). In addition, our data provide direct evidence showing that NMDA receptor internalization can be enhanced by actin depolymerization, suggesting that the stability of surface NMDA receptors is dependent on an intact actin cytoskeleton.

In summary, this study has revealed a novel function of neuregulin in mature neurons (i.e., the regulation of NMDA receptor channel activity). Activation of the NRG/ErbB signaling causes the elevation of intracellular Ca2+ and activation of ERK, which in turn enhance the actin depolymerization, leading to the increased NMDA receptor internalization and the reduced NMDAR-mediated currents. Given the key role of NMDA receptors in schizophrenia (Tsai and Coyle, 2002), the regulation of NMDAR function could be one of the mechanisms underlying the involvement of neuregulin in this neuropsychiatric disorder (Harrison and Owen, 2003).

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS48911, MH63128, and AG21923, National Science Foundation Grant IBN-0117026, and a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Independent Investigator Award to Z.Y. and by grants from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong SAR (HKUST 6103/00M) to N. Y. I. We thank Xiaoqing Chen for her technical support. The full-length neuregulin protein was kindly provided by Drs. Miwako Ozaki and Hiroyuki Nawa.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Zhen Yan, Department of Physiology and Biophysics, State University of New York at Buffalo, 124 Sherman Hall, Buffalo, NY 14214. E-mail: zhenyan@buffalo.edu.

Copyright © 2005 Society for Neuroscience 0270-6474/05/254974-11$15.00/0

References

- Akbarian S, Sucher NJ, Bradley D, Tafazzoli A, Trinh D, Hetrick WP, Potkin SG, Sandman CA, Bunney Jr WE, Jones EG (1996) Selective alterations in gene expression for NMDA receptor subunits in prefrontal cortex of schizophrenics. J Neurosci 16: 19-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison DW, Gelfand VI, Spector I, Craig AM (1998) Role of actin in anchoring postsynaptic receptors in cultured hippocampal neurons: differential attachment of NMDA versus AMPA receptors. J Neurosci 18: 2423-2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altiok N, Altiok S, Changeux JP (1997) Heregulin-stimulated acetylcholine receptor gene expression in muscle: requirement for MAP kinase and evidence for a parallel inhibitory pathway independent of electrical activity. EMBO J 16: 717-725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton ES, Marchionni MA, Lee KF, Rakic P (1997) Role of GGF/neuregulin signaling in interactions between migrating neurons and radial glia in the developing cerebral cortex. Development 124: 3501-3510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonanno A, Fischbach GD (2001) Neuregulin and ErbB receptor signaling pathways in the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol 11: 287-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll RC, Zukin RS (2002) NMDA-receptor trafficking and targeting: implications for synaptic transmission and plasticity. Trends Neurosci 25: 571-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Greengard P, Yan Z (2004) Potentiation of NMDA receptor currents by dopamine D1 receptors in prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 2596-2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corfas G, Rosen KM, Aratake H, Krauss R, Fischbach GD (1995) Differential expression of ARIA isoforms in the rat brain. Neuron 14: 103-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corfas G, Roy K, Buxbaum JD (2004) Neuregulin 1-erbB signaling and the molecular/cellular basis of schizophrenia. Nat Neurosci 7: 575-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exton JH (1996) Regulation of phosphoinositide phospholipases by hormones, neurotransmitters, and other agonists linked to G proteins. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 36: 481-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig LA, Cooper GM (1988) Inhibition of NIH 3T3 cell proliferation by a mutant ras protein with preferential affinity for GDP. Mol Cell Biol 8: 3235-3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez PA, Tang DG, Cheng L, Prochiantz A, Mudge AW, Raff MC (2000) Evidence that axon-derived neuregulin promotes oligodendrocyte survival in the developing rat optic nerve. Neuron 28: 81-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach GD, Rosen KM (1997) ARIA: a neuromuscular junction neuregulin. Annu Rev Neurosci 20: 429-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M, Kaech S, Knutti D, Matus A (1998) Rapid actin-based plasticity in dendritic spines. Neuron 20: 847-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M, Kaech S, Wagner U, Brinkhaus H, Matus A (2000) Glutamate receptors regulate actin-based plasticity in dendritic spines. Nat Neurosci 3: 887-894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry DW, Nelson JM, Slintak V, Keller PR, Rewcastle GW, Denny WA, Zhou H, Bridges AJ (1997) Biochemical and antiproliferative properties of 4-[ar(alk)ylamino]pyridopyrimidines, a new chemical class of potent and specific epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Biochem Pharmacol 54: 877-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu AK, Cheung WM, Ip FC, Ip NY (1999) Identification of genes induced by neuregulin in cultured myotubes. Mol Cell Neurosci 14: 241-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu AK, Fu WY, Cheung J, Tsim KW, Ip FC, Wang JH, Ip NY (2001) Cdk5 is involved in neuregulin-induced AChR expression at the neuromuscular junction. Nat Neurosci 4: 374-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia RA, Vasudevan K, Buonanno A (2000) The neuregulin receptor ErbB-4 interacts with PDZ-containing proteins at neuronal synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 3596-3601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerecke KM, Wyss JM, Karavanova I, Buonanno A, Carroll SL (2001) ErbB transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptors are differentially expressed throughout the adult rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol 433: 86-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gout I, Dhand R, Hiles ID, Fry MJ, Panayotou G, Das P, Truong O, Totty NF, Hsuan J, Booker GW (1993) The GTPase dynamin binds to and is activated by a subset of SH3 domains. Cell 75: 25-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakak Y, Walker JR, Li C, Wong WH, Davis KL, Buxbaum JD, Haroutunian V, Fienberg AA (2001) Genome-wide expression analysis reveals dysregulation of myelination-related genes in chronic schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 4746-4751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PJ, Owen MJ (2003) Genes for schizophrenia? Recent findings and their pathophysiological implications. Lancet 361: 417-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes WE, Sliwkowski MX, Akita RW, Henzel WJ, Lee J, Park JW, Yansura D, Abadi N, Raab H, Lewis GD, Shepard HM, Kuang WJ, Wood WI, Goeddel DV, Vandlen RL (1992) Identification of heregulin, a specific activator of p185erbB2. Science 256: 1205-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YZ, Won S, Ali DW, Wang Q, Tanowitz M, Du QS, Pelkey KA, Yang DJ, Xiong WC, Salter MW, Mei L (2000) Regulation of neuregulin signaling by PSD-95 interacting with ErbB4 at CNS synapses. Neuron 26: 443-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch JD, Roth RH (1999) The neuropsychopharmacology of phencyclidine: from NMDA receptor hypofunction to the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 20: 201-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim IJ, Drahushuk KM, Kim WY, Gonsiorek EA, Lein P, Andres DA, Higgins D (2004) Extracellular signal-regulated kinases regulate dendritic growth in rat sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci 24: 3304-3312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittler JT, Delmas P, Jovanovic JN, Brown DA, Smart TG, Moss SJ (2000) Constitutive endocytosis of GABAA receptors by an association with the adaptin AP2 complex modulates inhibitory synaptic currents in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 20: 7972-7977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornau HC, Schenker LT, Kennedy MB, Seeburg PH (1995) Domain interaction between NMDA receptor subunits and the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95. Science 269: 1737-1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krengel U, Schlichting L, Scherer A, Schumann R, Frech M, John J, Kabsch W, Pai EF, Wittinghofer A (1990) Three-dimensional structures of H-ras p21 mutants: molecular basis for their inability to function as signal switch molecules. Cell 62: 539-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupp JJ, Vissel B, Thomas CG, Heinemann SF, Westbrook GL (1999) Interactions of calmodulin and alpha-actinin with the NR1 subunit modulate Ca2+-dependent inactivation of NMDA receptors. J Neurosci 19: 1165-1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutsuna H, Suzuki K, Kamata N, Kato T, Hato F, Mizuno K, Kobayashi H, Ishii M, Kitagawa S (2004) Actin reorganization and morphological changes in human neutrophils stimulated by TNF, GM-CSF, and G-CSF: the role of MAP kinases. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C55-C64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan JY, Skeberdis VA, Jover T, Grooms SY, Lin Y, Araneda RC, Zheng X, Bennett MV, Zukin RS (2001) Protein kinase C modulates NMDA receptor trafficking and gating. Nat Neurosci 4: 382-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei S, Czerwinska E, Czerwinski W, Walsh MP, MacDonald JF (2001) Regulation of NMDA receptor activity by F-actin and myosin light chain kinase. J Neurosci 21: 8464-8472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard AS, Lim IA, Hemsworth DE, Horne MC, Hell JW (1999) Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II is associated with the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 3239-3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li BS, Sun MK, Zhang L, Takahashi S, Ma W, Vinade L, Kulkarni AB, Brady RO, Pant HC (2001) Regulation of NMDA receptors by cyclin-dependent kinase-5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 12742-12747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissin DV, Gomperts SN, Carroll RC, Christine CW, Kalman D, Kitamura M, Hardy S, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC, von Zastrow M (1998) Activity differentially regulates the surface expression of synaptic AMPA and NMDA glutamate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 7097-7102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Ford B, Mann MA, Fischbach GD (2001) Neuregulins increase α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and enhance excitatory synaptic transmission in GABAergic interneurons of the hippocampus. J Neurosci 21: 5660-5669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe T, Wyllie DJ, Perkel DJ, Nicoll RA (1993) Modulation of synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation: effects on paired pulse facilitation and EPSC variance in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. J Neurophysiol 70: 1451-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour SJ, Matten WT, Hermann AS, Candia JM, Rong S, Fukasawa K, Vande Woude GF, Ahn NG (1994) Transformation of mammalian cells by constitutively active MAP kinase kinase. Science 265: 966-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matus A (2000) Actin-based plasticity in dendritic spines. Science 290: 754-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matus A, Ackermann M, Pehling G, Byers HR, Fujiwara K (1982) High actin concentrations in brain dendritic spines and postsynaptic densities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 79: 7590-7594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus MT, Sharp PA (2002) Gene silencing in mammals by small interfering RNAs. Nat Rev Genet 3: 737-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nong Y, Huang YQ, Ju W, Kalia LV, Ahmadian G, Wang YT, Salter MW (2003) Glycine binding primes NMDA receptor internalization. Nature 422: 302-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki M, Sasner M, Yano R, Lu HS, Buonanno A (1997) Neuregulin-beta induces expression of an NMDA-receptor subunit. Nature 390: 691-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki M, Tohyama K, Kishida H, Buonanno A, Yano R, Hashikawa T (2000) Roles of neuregulin in synaptogenesis between mossy fibers and cerebellar granule cells. J Neurosci Res 59: 612-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkas-Kramarski R, Eilam R, Spiegler O, Lavi S, Liu N, Chang D, Wen D, Schwartz M, Yarden Y (1994) Brain neurons and glial cells express Neu differentiation factor/heregulin: a survival factor for astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 9387-9391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard TD, Cooper JA (1986) Actin and actin-binding proteins. A critical evaluation of mechanisms and functions. Annu Rev Biochem 55: 987-1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieff HI, Raetzman LT, Sapp DW, Yeh HH, Siegel RE, Corfas G (1999) Neuregulin induces GABAA receptor subunit expression and neurite out-growth in cerebellar granule cells. J Neurosci 19: 10757-10766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rio C, Rieff HI, Qi P, Khurana TS, Corfas G (1997) Neuregulin and erbB receptors play a critical role in neuronal migration. Neuron 19: 39-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SL, Gelfand VI (2000) Membrane trafficking, organelle transport, and the cytoskeleton. Curr Opin Cell Biol 12: 57-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund C, Westbrook GL (1993) Calcium-induced actin depolymerization reduces NMDA channel activity. Neuron 10: 805-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter MW, Kalia LV (2004) Src kinases: a hub for NMDA receptor regulation. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 317-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler R, Xiong Z, Lu WY, MacDonald JF, Tymianski M (2000) Distinct roles of synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in excitotoxicity. J Neurosci 20: 22-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si J, Luo Z, Mei L (1996) Induction of acetylcholine receptor gene expression by ARIA requires activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 271: 19752-19759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson H, Sigurdsson E, Steinthorsdottir V, Bjornsdottir S, Sigmundsson T, Ghosh S, Brynjolfsson J, Gunnarsdottir S, Ivarsson O, Chou TT, Hjaltason O, Birgisdottir B, Jonsson H, Gudnadottir VG, Gudmundsdottir E, Bjornsson A, Ingvarsson B, Ingason A, Sigfusson S, Hardardottir H, et al. (2002) Neuregulin 1 and susceptibility to schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet 71: 877-892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson H, Sarginson J, Kong A, Yates P, Steinthorsdottir V, Gudfinnsson E, Gunnarsdottir S, Walker N, Petursson H, Crombie C, Ingason A, Gulcher JR, Stefansson K, St Clair D (2003) Association of neuregulin 1 with schizophrenia confirmed in a Scottish population. Am J Hum Genet 72: 83-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet RW, Yokoyama S, Kamata T, Feramisco JR, Rosenberg M, Gross M (1984) The product of ras is a GTPase and the T24 oncogenic mutant is deficient in this activity. Nature 311: 273-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tansey MG, Chu GC, Merlie JP (1996) ARIA/HRG regulates AChR epsilon subunit gene expression at the neuromuscular synapse via activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Ras/MAPK pathway. J Cell Biol 134: 465-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkachev D, Mimmack ML, Ryan MM, Wayland M, Freeman T, Jones PB, Starkey M, Webster MJ, Yolken RH, Bahn S (2003) Oligodendrocyte dysfunction in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Lancet 362: 798-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai G, Coyle JT (2002) Glutamatergic mechanisms in schizophrenia. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 42: 165-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyszkiewicz JP, Gu Z, Wang X, Cai X, Yan Z (2004) Group II metabotropic glutamate receptors enhance NMDA receptor currents via a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism in pyramidal neurons of prefrontal cortex. J Physiol (Lond) 554: 765-777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian T, Fischbach G, Miller R (1999) Failure of spinal cord oligodendrocyte development in mice lacking neuregulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 731-735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissel B, Krupp JJ, Heinemann SF, Westbrook GL (2001) A use-dependent tyrosine dephosphorylation of NMDA receptors is independent of ion flux. Nat Neurosci 4: 587-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhong P, Gu Z, Yan Z (2003) Regulation of NMDA receptors by dopamine D4 signaling in prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci 23: 9852-9861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YT, Salter MW (1994) Regulation of NMDA receptors by tyrosine kinases and phosphatases. Nature 369: 233-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler A, Teichberg VI (1998) Brain spectrin binding to the NMDA receptor is regulated by phosphorylation, calcium and calmodulin. EMBO J 17: 3931-3939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenthold RJ, Prybylowski K, Standley S, Sans N, Petralia RS (2003) Trafficking of NMDA receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 43: 335-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal RS, Tavalin SJ, Lin JW, Alto NM, Fraser ID, Langeberg LK, Sheng M, Scott JD (1999) Regulation of NMDA receptors by an associated phosphatase-kinase signaling complex. Science 285: 93-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams NM, Preece A, Spurlock G, Norton N, Williams HJ, Zammit S, O'Donovan MC, Owen MJ (2003) Support for genetic variation in neuregulin 1 and susceptibility to schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 8: 485-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyszynski M, Lin J, Rao A, Nigh E, Beggs AH, Craig AM, Sheng M (1997) Competitive binding of alpha-actinin and calmodulin to the NMDA receptor. Nature 385: 439-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Kuo Y, Devay P, Yu C, Role L (1998) A cysteine-rich isoform of neuregulin controls the level of expression of neuronal nicotinic receptor channels during synaptogenesis. Neuron 20: 255-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong P, Gu Z, Wang X, Jiang H, Feng J, Yan Z (2003) Impaired modulation of GABAergic transmission by muscarinic receptors in a mouse transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. J Biol Chem 278: 26888-26896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Xiao M, Nicoll RA (2001) Contribution of cytoskeleton to the internalization of AMPA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 1261-1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]