Abstract

The olfactory system is able to detect a large number of chemical structures with a remarkable sensitivity and specificity. Odorants are first detected by odorant receptors present in the cilia of olfactory neurons. The activated receptors couple to an olfactory-specific G-protein (Golf), which activates adenylyl cyclase III to produce cAMP. Increased cAMP levels activate cyclic nucleotide-gated channels, causing cell membrane depolarization. Here we used yeast two-hybrid to search for potential regulators for Gαolf. We found that Ric-8B (for resistant to inhibitors of cholinesterase), a putative GTP exchange factor, is able to interact with Gαolf. Like Gαolf, Ric-8B is predominantly expressed in the mature olfactory sensory neurons and also in a few regions in the brain. The highly restricted and colocalized expression patterns of Ric-8B and Gαolf strongly indicate that Ric-8B is a functional partner for Gαolf. Finally, we show that Ric-8B is able to potentiate Gαolf-dependent cAMP accumulation in human embryonic kidney 293 cells and therefore may be an important component for odorant signal transduction.

Keywords: olfactory neurons, signal transduction, GEF, G-protein, G-protein-coupled receptors, odorant receptors, synembryn

Introduction

Odorant signal transduction initiates when odorants bind and activate a large number of odorant receptors located in the cilia of the olfactory neurons in the nose (Buck and Axel, 1991; Buck, 2000). The activated receptors then couple to the olfactory-specific G-protein Gαolf to stimulate adenylyl cyclase type III. The concentration of cAMP in the cilia rises triggering the opening of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels, membrane depolarization, and generation of action potentials in the olfactory axon (Firestein, 2001; Ronnett and Moon, 2002; Mombaerts, 2004).

The odorant-induced production of cAMP is typically rapid and transient (Boekhoff et al., 1990; Breer et al., 1990). The ability of olfactory sensory neurons to adapt to odors allows the olfactory system to detect over a broader range of stimuli and also to rapidly recover the ability to sense an odorant. A large number of possible molecular mechanisms for signal termination have been described, such as odorant receptor phosphorylation (Boekhoff and Breer, 1992; Peppel et al., 1997), inhibition of adenylyl cyclase (Wei et al., 1998; Sinnarajah et al., 2001), stimulation of cAMP hydrolysis via activation of phosphodiesterases (Borisy et al., 1992), and cAMP-gated channel regulation (Chen and Yau, 1994; Kurahashi and Menini, 1997; Zufall and Leinders-Zufall, 2000; Munger et al., 2001). The regulatory mechanisms described so far involve all components of the signaling cascade, except Gαolf. Therefore, it is not clear yet whether Gαolf can also be a target for regulatory events in the olfactory sensory neurons.

It is generally believed that the activation of heterotrimeric G-proteins is exclusively accomplished by the action of G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCRs), with only a few receptor-independent activators of G-protein signaling described (Strittmatter et al., 1990; Sato et al., 1996; Luo and Denker, 1999; Cismowski et al., 2000). Recently, two new mammalian heterotrimeric Gα GTP exchange factors (GEFs) [Ric-8A and Ric-8B (for resistant to inhibitors of cholinesterase)] were identified (Tall et al., 2003). GEFs catalyze the exchange of GDP for GTP to generate an activated form of Gα, which is then able to activate a variety of effectors (Sprang, 2001). Biochemical characterization indicated that Ric-8A functions as a GEF for Gαq, Gαi1, and Gαo but not for Gαs (Tall et al., 2003). Ric-8B, conversely, was shown to interact with Gαs and Gαq (Tall et al., 2003).

To search for potential regulators for the olfactory G-protein, we used yeast two-hybrid to screen an olfactory epithelium (OE) cDNA library using Gαolf as bait and found Ric-8B. We performed Northern blot analysis and show that Ric-8B is specifically expressed in the olfactory epithelium. In situ hybridization experiments indicated that Ric-8B is expressed in mature olfactory sensory neurons and that the expression colocalizes with that of Gαolf in the olfactory epithelium. Ric-8B is also expressed in the regions of the brain previously shown to contain Gαolf, such as the striatum, nucleus accumbens, and olfactory tubercle. In addition, our results show that Ric-8B is able to potentiate the ability of Gαolf to activate cAMP production in heterologous cells, indicating that this putative GEF can regulate the function of Gαolf.

Materials and Methods

Yeast two-hybrid screen. Yeast two-hybrid screening was performed using the DupLEX-A system (OriGene Technologies, Rockville, MD). The complete coding region of Gαolf was obtained by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and subcloned into the EcoRI/XhoI sites of the yeast bait expression vector pGilda (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) in fusion with the LexA DNA binding domain. The construct was transformed together with the lacZ reporter pSH18-34 into yeast strain RFY206 by the lithium acetate method (Golemis et al., 1999). An oligo-dT-primed cDNA library was prepared from mouse (C57BL/6J) OE poly(A+) RNA using the cDNA synthesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The cDNA was directionally cloned into the EcoRI/XhoI sites of the pJG4-5 target vector, in fusion with the B42 activator domain. The ligated products were electroporated into Escherichia coli DH5α and resultant transformants (5 × 106 with an average insert size of 0.7 kb) were plated onto Luria-Bertani medium/ampicillin at a density of 5 × 105 colonies per plate (150 mm). The plasmid library was then purified using a Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) column after scraping the cells from the plate and was transformed into the yeast strain EGY48 using the lithium acetate method. Yeast transformations were done with an efficiency of 104 colony forming units/μg DNA. The RFY206 strain containing the bait and the reporter (2 × 107 cells) was mated with the strain EGY48 containing the library (107 cells) as described by Golemis et al. (1999). Diploids were induced with galactose for the expression of both the bait and the library-encoded proteins, and interactors were selected on quadruple-deficient plates (Leu-, Trp-, His-, Ura-). Positive colonies were then assayed for β-galactosidase activity. The clones that grew on quadruple-deficient plates and turned blue in the β-galactosidase assay in the presence of galactose but not of glucose were selected. The cDNA inserts in the selected clones were analyzed through yeast-colony PCR using specific primers matching the pJG4-5 vector, and the DNA sequences were determined by automated sequencing. Clones of interest had their plasmids isolated and transformed into E. coli DH5α. The E. coli clones containing the pJG4-5 library constructs were rescued, and their plasmids were isolated. The plasmids were cotransformed with the lacZ reporter pSH18-34 into EGY48 and mated with the strain containing the bait to confirm the interactions.

Yeast interaction mating tests. Interactions between different baits and targets were checked using the method described by Finley and Brent (1994). Baits strains that harbor the lacZ reporter pSH18-34 and express different regions of Gαolf were prepared as described above. Briefly, bait strains were streaked in horizontal rows on a Glu His- Ura- plate and target strains in vertical columns on a Glu Trp- plate. The two plates were then replica plated onto a yeast/peptone/dextrose (YPD) plate, in which strains mated and formed diploids at the intersections of the streaks. The YPD plate was replica plated onto two indicator plates containing the following: (1) Gal His- Ura- Trp- 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-gal) (shown in Fig. 1c); and (2) Gal Leu- His- Ura- Trp- (data not shown). Replicas were also plated onto control plates containing glucose instead of galactose, but no interactions were observed (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Ric-8B interacts with Gαolf. a, Amino acid sequence alignment of mouse Ric-8B and Ric-8A. Shaded sequences indicate areas of amino acid identity. The nine synembryn signatures are underlined in gray. The region corresponding to exon 9 is underlined in black. b, Schematic representation of the Ric-8B gene structure. Exons are represented by black boxes, and introns are represented by thick lines. The initiator methionine ATG codon is in exon 1, and the stop codon is in the beginning of exon 10. The Ric-8B cDNA contains all of the 10 exons. The alternative spliced variant (denominated Ric-8BΔ9) also identified in the two-hybrid screen does not contain exon 9, as indicated. c, Interaction between Ric-8B and Gαolf. Bait strains expressing full-length Gαolf (amino acids 1-381) or different regions of Gαolf (amino acids 1-42, 72-188, or 352-381) were mated with target strains expressing full-length Ric-8B or Ric-8BΔ9. X-gal was used to score positive interactions. pBait (B), which constitutively expresses a LexA bait fusion protein that interacts with the fusion protein from pTarget (T), was used as positive control.

Northern blot. Total RNA was prepared from tissues from C57BL/6J mice using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The total RNA samples (10 μg) were size fractionated on formaldehyde gels and blotted onto a Hybond N+ nylon membrane (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The membrane was hybridized overnight at 37°C in hybridization buffer [6× saline-sodium phosphate EDTA (SSPE), 5× Denhardt's solution, 0.1 mg/ml sheared herring sperm DNA, 0.5% SDS, and 50% formamide] with a 32P-labeled probe prepared from Ric-8B (from the region corresponding to the entire coding region; GenBank accession number AY940666) by random priming (Invitrogen). The membrane was washed twice in 0.1% SDS and 0.5× SSPE at 65°C for 30 min and analyzed using a Storm 840 PhosphorImager (Amersham Biosciences).

RT-PCR. RNA was prepared from different mouse tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). First, 1 μg of total RNA plus 100 ng of oligo-dT in 13.5 μl of DEPC-treated water were incubated for 2 min at 70°C. The reaction was rapidly chilled on ice and used to synthesize cDNA in 20 μl of 1 × Superscript II first-strand buffer containing 0.5 mm deoxy NTP (dNTP), 3 mm MgCl2, 20 U of RNase inhibitor (RNaseOUT; Invitrogen), and 200 U of Superscript II reverse transcriptase at 42°C for 60 min. The product was diluted to 100 μl with DEPC-treated water. PCRs (25 μl) containing 5 μl of cDNA, 0.2 mm dNTP, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.5 μm each of forward and reverse primers, and 1.25 U of Platinum TaqDNA polymerase (Invitrogen) were heated to 95°C for 2 min, followed by 25 (Ric-8B) or 30 [Gαolf and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)] thermal cycles of 95°C for 45 s, 58°C (Ric-8B), 57°C (Gαolf), or 55°C (GAPDH) for 45 s, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final incubation at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were analyzed in 1.5% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide.

The primers AAGCTGGTTCGTCTCATGAC (forward) and GTCTGTGTCCGAGCTGGTC (reverse) were used to amplify the region across the ninth exon-containing isoform of Ric-8B, and the primers ATGGGGTGTTTGGGCAACAG (forward) and TCACAAGAGTTCGTACTGCTTG (reverse) were used to amplify Gαolf.

In situ hybridization. In situ hybridization was performed according to Schaeren-Wiemers and Gerfin-Moser (1993). Noses or brains were dissected, respectively, from 2- and 6-week-old mice and freshly embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). Sequential 20 μm sections were prepared with a cryostat and hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled cRNA probes prepared from Ric-8B (region corresponding to nucleotides 790-2256), Gαs, and Gαolf (corresponding to the full coding regions) cDNAs. Color reactions were performed for 1.5 h in the olfactory epithelium and overnight in the brain, except for the Gαs reaction on the coronal brain section, which was performed for 1.5 h.

Tissue culture cAMP detection. The cDNAs corresponding to the full-length sequence of Ric-8B, Ric-8BΔ9 (GenBank accession number AY940667), Gαolf, and dopamine D1 receptor (D1R) were cloned by PCR using cDNAs prepared from mouse olfactory epithelium and subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 expression vector containing a FLAG epitope. Expression vectors for Gαs and the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) were kindly provided by Stephen Liberles and Linda Buck (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA). Gαolf and Ric-8B protein expression was checked by Western blot using, respectively, an anti-Gαolf antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and an anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (data not shown).

Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, 1 mm glutamine, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 50 U/ml penicillin at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells (0.5 × 105) were plated into each well of a 96-well plate for 16-20 h and transfected using lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen) with constructs expressing the different cDNAs (100 ng/well). After 3 h of transfection, medium was replaced by serum-free media containing the agonist (10 μm), and cells were incubated for another 40 h. Shorter periods of agonist stimulation (10, 30, or 120 min) produced similar results (see Fig. 5c). cAMP was measured using the cAMP Enzymeimmunoassay (Amersham Biosciences) following the protocol of the manufacturer.

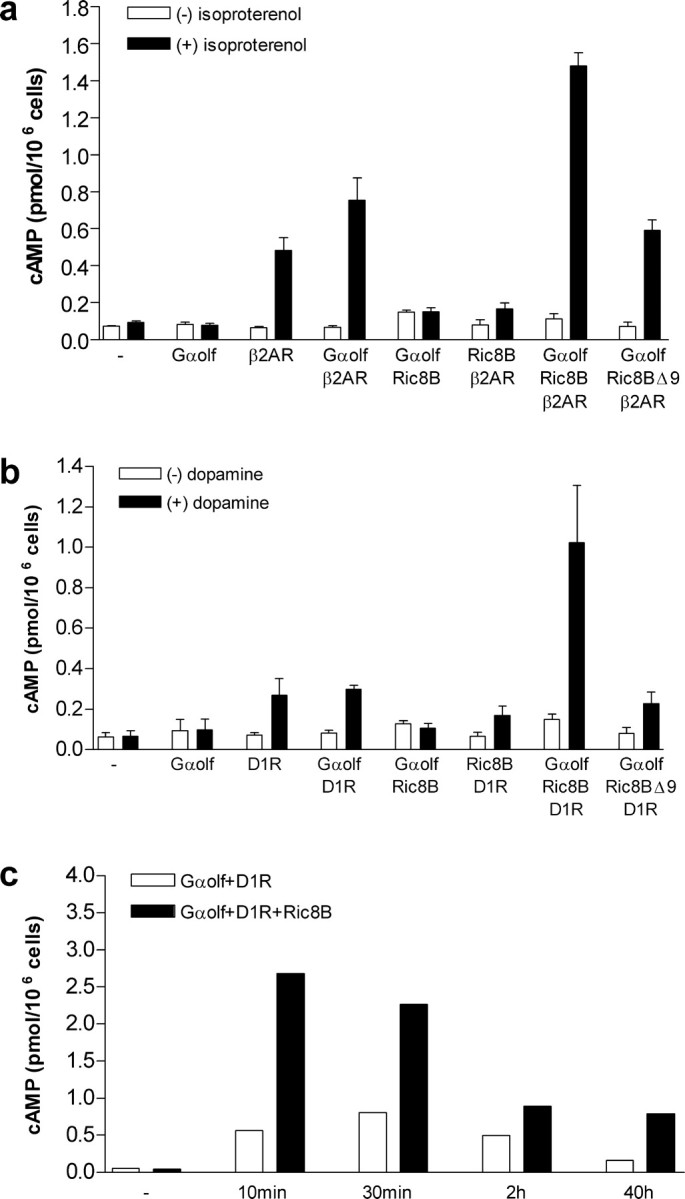

Figure 5.

Amplification of cAMP accumulation by Ric-8B. a, Production of cAMP was measured in HEK293 cells transfected as indicated with Gαolf, Ric-8B, Ric-8BΔ9, Gαs, and β2AR expression vectors. Activation was recorded in the absence (white bars) or presence (black bars) of 10 μm isoproterenol. The data are expressed as the means ± SE from three different experiments, each performed in duplicate. cAMP accumulation is presented as picomoles per million cells. - indicates untransfected cells (control). b, Same as in a, except that cells were transfected with D1R instead of β2AR and the agonist was dopamine (10 μm). c, Cells were cotransfected with Gαolf and D1R (white bars) or with Gαolf, D1R, and Ric-8B (black bars). Production of cAMP was measured after dopamine stimulation for the indicated periods of time. - indicates that no dopamine was added. The data are expressed as the means of two independent experiments.

Results

Gαolf interacts with Ric-8B

An olfactory epithelium cDNA library was screened with Gαolf as bait (see Materials and Methods). We obtained 74 clones. Of these, 64 showed strong interactions (strong blue color developed after 12 h of incubation in the presence of X-gal), and the other 10 showed comparatively much weaker interactions with the bait (detected after 24 h in the presence of X-gal). The 64 clones showing strong interaction with Gαolf encode the full-length sequence of Ric-8B. Ric-8B cDNA is 1683 bp long and encodes a protein of 560 amino acids (Fig. 1a). The deduced amino acid sequence does not show conserved motifs or any other valuable information on the protein, except that Ric-8B shares ∼40% amino acid sequence identity with Ric-8A, which was shown to work as a GEF for a subset of Gα subunits (Tall et al., 2003). These two proteins share nine conserved synembryn signatures that show 58-90% amino acid sequence identity (Fig. 1a). However, whether Ric-8B acts as a GEF has yet to be determined.

The remaining clones (which showed weaker interactions with Gαolf) contained an alternatively spliced variant of Ric-8B that lacks exon 9 (denominated here as Ric-8BΔ9) (Fig. 1a,b), indicating that this region of Ric-8B is important for the interaction between Ric-8B and Gαolf.

We next asked which region of Gαolf is required for the interaction with Ric-8B. Baits containing different regions of Gαolf were constructed and checked for their ability to interact with Ric-8B (Fig. 1c). A fragment containing only the last 30 amino acids of Gαolf (Gαolf 352-381) retained the ability to interact with Ric-8B, but baits containing N-terminal (Gαolf 1-42) or central regions (Gαolf72-188) of Gαolf showed no interaction, indicating that the C-terminal region of Gαolf is involved in the interaction. It has been demonstrated previously that the C-terminal region of Gα subunits plays an important role in specifying receptor interaction (Conklin et al., 1993). Hence, if olfactory receptors (ORs) and Ric-8B can both interact with the C-terminal region of Gαolf, it is possible that these interactions are mutually exclusive.

Consistent with what was observed during the screening, we could barely detect interaction between Ric-8BΔ9 and Gαolf. Conversely, Ric-8BΔ9 retains the ability to interact with the C-terminal region of Gαolf (Fig. 1c). These results suggest the existence of a second domain in Gαolf besides the C terminus that is involved in binding to Ric-8B and that the sequence corresponding to exon 9 of Ric-8B is required.

Tissue distribution of Ric-8B expression

We next performed Northern blot experiments to examine the tissue distribution of Ric-8B expression. Total RNA prepared from 10 different mouse tissues was size fractionated, blotted onto membranes, and hybridized with a 32P-labeled probe corresponding to the Ric-8B cDNA. Control hybridization was performed with a probe prepared from GAPDH. The Ric-8B probe hybridized to two major bands of ∼2 and 3 kb only in the olfactory epithelium (Fig. 2a). A smaller and fainter band was also detected in the skeletal muscle, but, in general, no other tested tissue showed Ric-8B expression. We also used RT-PCR, which is a more sensitive method than Northern blot, to amplify Ric-8B and Gαolf from the same tissues analyzed in Figure 2a. Using this method, we were able to detect lower levels of Ric-8B expression also in the eye, brain, skeletal muscle, and heart (Fig. 2b). Gαolf expression was restricted to the olfactory epithelium and the brain (Fig. 2b). These data show that Ric-8B gene is preferentially transcribed in the olfactory epithelium and, to a lower extent, in the brain, eye, and muscle.

Figure 2.

Ric-8B is mainly expressed in the olfactory epithelium. a, Northern blot analysis of mouse total RNA: 1, olfactory epithelium; 2, whole eye; 3, brain; 4, skeletal muscle; 5, heart; 6, kidney; 7, liver; 8, lung; 9, testis; 10, thymus. A probe prepared from Ric-8B was hybridized using stringent conditions. Hybridization with GAPDH probe indicated that similar amounts of RNA were loaded in each lane. Sizes are given in kilobases. b, RT-PCR was conducted to amplify Ric-8B, Gαolf, and GAPDH from the same tissues as in a. (-), Negative control (no cDNA was added to the reaction). c, Semiquantitative RT-PCR was conducted to amplify Ric-8B from olfactory epithelium RNA after 20, 25, 30, and 35 cycles, as indicated. The PCR product sizes expected for Ric-8B using the primers that flank the ninth exon are 462 bp (Ric-8B) and 342 bp (Ric-8BΔ9). M, Molecular weights are given in kilobases.

Because we identified two different splicing variants of the Ric-8B mRNA during the screening (Fig. 1a,b), we conducted semiquantitative RT-PCR experiments with primers that amplify across the ninth exon to determine which isoform is predominant in the olfactory epithelium. Our results indicate that Ric-8B and Ric-8BΔ9 isoforms are expressed in equivalent amounts (Fig. 2c).

Expression of Ric-8B and Gαolf is colocalized in the olfactory epithelium

It was demonstrated previously that Ric-8B interacts with Gαs subunits (Tall et al., 2003). It is therefore not surprising that Gαolf also interacts with Ric-8B, because Gαolf shows 88% amino acid sequence identity to Gαs (Jones and Reed, 1989). This raises the question of which one of the two subunits, Gαs or Gαolf, is the real biological target for Ric-8B. To address this question, we compared the localization of Ric-8B, Gαs, and Gαolf expression in the OE and in the brain.

In situ hybridization experiments were performed with digoxigenin-labeled antisense cRNA probes for Ric-8B, Gαs, and Gαolf. High-stringency conditions were used to ensure that probes detected only very closely related transcripts. The olfactory sensory neurons in the olfactory epithelium express Ric-8B, Gαolf, and Gαs (Fig. 3a-c), but the localization of the neurons expressing the different genes within the epithelium differs: whereas Ric-8B and Gαolf are predominantly expressed in mature neurons located in the broad central area of the epithelium, Gαs is expressed throughout the epithelium, including the basal layer that contains precursors and immature neurons (Fig. 3g-i). No signal was detected when the corresponding sense probes were used (Fig. 3d-f). Figure 3j-l shows hybridization of probes for Ric-8B (j), Gαolf (k), and olfactory marker protein (OMP) (l) to coronal sections through an anterior part of the nose that contains both olfactory and vomeronasal epithelia neurons. OMP is expressed in both types of neurons. Like Gαolf (Berghard et al., 1996), Ric-8B is not expressed in the vomeronasal neurons.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Ric-8B mRNA in the olfactory system. a-f, Coronal sections through the nasal cavity were hybridized with antisense digoxigenin-labeled probes specific for Ric-8B (a), Gαolf (b), and Gαs (c). Corresponding sense digoxigenin-labeled probes were used as negative controls (d-f). Neurons in the olfactory epithelium that hybridize with the Ric-8B probe show a pattern typical of that seen with the Gαolf probe. g-i, Magnified regions from a-c showing the distribution of stained cells within the olfactory epithelium. Ric-8B (g) and Gαolf (h) probes hybridize to mature neurons (ON) but not to the most apical layer of cells closest to the lumen [supporting cells (SC)] or to the immature neurons localized in the basal layer of the epithelium (BC). The Gαs probe (i), conversely, hybridizes preferentially to immature cells localized in the basal layer of the epithelium. j-l, Sections cut through the olfactory and vomeronasal epithelia. Ric-8B (j) and Gαolf (k) probes hybridize to neurons in the olfactory epithelium but not to vomeronasal neurons. OMP (l) is expressed in the olfactory and vomeronasal epithelia.

Expression of Ric-8B and Gαolf is colocalized in the brain

As reported previously, Gαs is widely expressed in the brain, except in the striatum, nucleus accumbens, and olfactory tubercle (Belluscio et al., 1998; Zhuang et al., 2000) (Fig. 4). Although Gαolf is preferentially expressed in the olfactory epithelium, it is also expressed in some regions of the brain, namely the striatum (made up of the caudate nucleus and putamen), nucleus accumbens, olfactory tubercle, piriform cortex, dentate gyrus, CA3 region of the hippocampus, and Purkinje cells of the cerebellum (Belluscio et al., 1998; Zhuang et al., 2000) (Fig. 4c,h). This non-overlapping pattern of Gαs and Gαolf expression in the brain suggests that Gαolf is the functional G-protein that stimulates cAMP production in the regions that lack Gαs.

Figure 4.

Comparison of mRNA expression patterns for Ric-8B, Gαolf, and Gαs in the adult mouse brain. a-f, Sagittal brain sections were hybridized with antisense digoxigenin-labeled probes specific for Ric-8B (a), Gαolf (c), and Gαs (e). Corresponding sense digoxigenin-labeled probes were used as negative controls (b, d, f). g-i, Coronal brain sections were hybridized with antisense digoxigenin-labeled probes specific for Ric-8B (g), Gαolf (h), and Gαs (i). Ric-8B is expressed in regions known to express high levels of Gαolf and that show little or no expression of Gαs: the striatum (St), nucleus accumbens (Na), and olfactory tubercle (Ot). Ric-8B expression was also detected in the piriform cortex (Pc), dentate gyrus (Dg), and CA3 region of the hippocampus, in which both Gαolf and Gαs are also expressed. Ce, Cerebellum.

We performed in situ hybridization to determine the distribution of Ric-8B mRNA in the brain. Sagittal (Fig. 4a-f) and coronal (Fig. 4g-i) sections cut through the mouse brain were hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled antisense cRNA probes for Ric-8B (Fig. 4a,g), Gαolf (Fig. 4c,h), and Gαs (Fig. 4e,i). Interestingly, Ric-8B mRNA was colocalized with that of Gαolf, except for the Purkinje cells in the cerebellum, in which no Ric-8B mRNA was detected. As mentioned above, Ric-8B is able to interact with both Gαs and Gαolf subunits in the yeast two-hybrid system (Fig. 1c) (Tall et al., 2003). Nevertheless, the fact that Ric-8B is predominantly expressed in regions that show expression of Gαolf and little or no expression of Gαs strongly indicates that Gαolf must be its physiological interactor.

Ric-8B activates cAMP accumulation in the presence of Gαolf

Previous studies had shown that the β2AR can couple with Gαolf (Jones and Reed, 1989; Liu et al., 2001). To verify whether Ric-8B is able to regulate the activity of Gαolf, we transfected HEK293 cells with the expression vectors for Gαolf and the β2AR in the presence or absence of Ric-8B. cAMP production in each case was measured and compared with the cAMP levels of untransfected cells. Both expression of β2AR alone and coexpression of Gαolf and β2AR increased cAMP accumulation to similar levels (five-fold to sevenfold the control levels) in the presence of the agonist isoproterenol (Fig. 5a). These results indicate that the β2AR is able to couple to endogenous pathways to induce cAMP accumulation in HEK293 cells and are consistent with previous observations that Gαolf works poorly in heterologous systems when compared with Gαs (Jones and Reed, 1989; Jones et al., 1990). Surprisingly, the coexpression of Gαolf, β2AR, and Ric-8B induced much higher levels of cAMP accumulation in the presence of isoproterenol (∼15-fold the control levels) (Fig. 5a). This amplification effect is dependent on receptor activation, because no effect was detected when Gαolf was cotransfected with Ric-8B alone (Fig. 5a). It is also dependent on Gαolf, because no effect was observed when Ric-8B was cotransfected with β2AR alone (Fig. 5a).

Interestingly, Ric-8BΔ9, the alternatively spliced version of Ric-8B lacking exon 9, showed no significant effect on the Gαolf-dependent cAMP generation: in the presence of isoproterenol, the levels of cAMP accumulation in cells coexpressing Gαolf, β2AR, and Ric-8BΔ9 were similar to the ones in cells coexpressing only Gαolf and β2AR (Fig. 5a). The expression levels of Ric-8B and Ric-8BΔ9 protein in HEK293 cells were checked through Western blotting and indicated that both isoforms are expressed in equivalent amounts (data not shown). In conjunction with the fact that Ric-8B interacts with Gαolf although Ric-8BΔ9 does not (Fig. 1c), these results indicate that the signaling amplification effect caused by Ric-8B depends on a direct interaction between Gαolf and Ric-8B.

It has been shown previously that coupling of D1Rs to adenylyl cyclase in the striatum is mediated by Gαolf (Hervé et al., 1993, 2001; Zhuang et al., 2000). To verify whether Ric-8B is also able to regulate D1R signaling through Gαolf, we performed experiments identical to the ones described above, except that we now used D1R instead of β2AR and dopamine instead of isoproterenol as the agonist. We observed that D1R is also able to couple to endogenous HEK293 pathways when expressed alone or in conjunction with Gαolf (threefold the control levels) (Fig. 5b) but less efficiently than β2AR. As shown for β2AR, coexpression of D1R, Gαolf, and Ric-8B resulted in amplification of cAMP accumulation in the presence of the agonist, whereas coexpression of D1R, Gαolf, and Ric-8BΔ9 did not (Fig. 5b). Because Ric-8B is expressed in the striatum, these results suggest that it might also be involved in the regulation of the dopamine signaling pathways in the brain.

We also performed the cAMP accumulation experiments with agonist stimulation for different periods of time, as indicated in Figure 5c. In these experiments, we compared the amounts of cAMP accumulation in cells coexpressing Gαolf and D1R (white bars) with cells coexpressing Gαolf, D1R, and Ric-8B (black bars) after 10 min, 30 min, 2 h, and 40 h of dopamine stimulation. The Ric-8B-induced amplification effect was observed at all tested times. Although the average amplification effect was approximately the same for each time (cAMP produced in the presence of Ric-8B is between 2.5- and 5-fold the cAMP produced in the absence of Ric-8B), the shorter the periods of agonist stimulation, the higher was the total amount of cAMP produced. These results indicate that Ric-8B can directly modulate signaling through the dopamine receptor, possibly through a direct effect on GTP exchange.

Discussion

The transduction of chemical signals by ORs represents the initial step in a cascade of events that ultimately leads to the discrimination and perception of odorants. ORs signal through the downstream components Gαolf, type III adenylyl cyclase, and a cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel, which are highly enriched in the cilia of olfactory neurons (Ronnett and Moon, 2002; Mombaerts, 2004). The observation that knock-out mice for these three proteins are anosmic (they lack the sense of smell) (Brunet et al., 1996; Belluscio et al., 1998; Wong et al., 2000; Zheng et al., 2000) is consistent with a fundamental role for these components in olfactory sensory transduction.

In an effort to identify possible regulators for odor signal transduction, we screened a mouse olfactory epithelium cDNA library with Gαolf as bait. The interacting clones encode Ric-8B. Ric-8 was first isolated from a Caenorhabditis elegans screening for mutants resistant to inhibitors of cholinesterase (Ric) (Miller et al., 1996). These mutants were selected for their ability to survive the effects of inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase, which cause a toxic accumulation of secreted acetylcholine at synapses (Miller et al., 2000). The Ric mutant genes code for proteins that function in neurotransmitter secretion, causing a decrease in the amount of acetylcholine at the synapses, what compensates for the drug-induced accumulation of the neurotransmitter.

In addition to its role in the adult nervous system, Ric-8 is also required to regulate a subset of centrosome movements in the early embryo and therefore is also denominated synembryn (Miller and Rand, 2000). Ric-8B and Ric-8A are the mammalian homologs for the C. elegans Ric-8/synembryn. A recent study demonstrated that Ric-8A is a GEF for a subset of Gα-proteins (Tall et al., 2003). The fact that Ric-8B is related to Ric-8A in amino acid sequence (both sequences show conserved synembryn motifs) (Fig. 1a) and also binds Gα subunits suggests that Ric-8B may also be a GEF.

Consistent with the possible role as a GEF, Ric-8B is able to potentiate Gαolf-dependent cAMP accumulation in HEK293 cells. In this case, the β2AR would activate Gαolf, which would hydrolyze GTP. Ric-8B would bind to Gαolf and catalyze the release of GDP and the subsequent uptake of GTP, reactivating it. However, whether Ric-8B is really a GEF and works as a GEF for Gαolf still needs to be determined. It is also possible that Ric-8B is an effector for Gαolf and serves as a GEF for downstream targets, as was shown for other GEF proteins. It has been demonstrated, for example, that Gα13 directly activates p115RhoGEF, which in turn promotes GDP dissociation from the small GTPase Rho, allowing it to be activated again by GTP (Hall, 1998).

To date, a very small number of GEFs for heterotrimeric G-proteins has been described. It has been demonstrated, for example, that GAP-43, an intracellular protein closely associated with neuronal growth, stimulates GTP-γ-S binding to Go, which is a major component of the neuronal growth cone membrane (Strittmatter et al., 1990). Proteins that activate heterotrimeric G-protein signaling in a receptor-independent manner were also identified using a functional screen in yeast (Cismowski et al., 1999). One of these proteins, denominated AGS1 (for activator of G-protein signaling 1), functions as a GEF for Gαi/Gαo (Cismowski et al., 2000). Another protein, Pcp2 (Purkinje cell protein-2), expressed in Purkinje cells and retinal bipolar neurons was shown to function as a GEF for Gαo (Luo and Denker, 1999). It is still not clear whether these proteins work together with activated GPCRs to enhance or prolong signaling or if they function in the absence of a cell surface receptor.

It has been shown that Ric-8A functions as a GEF only for monomeric Gα subunits, which differs from the mechanism used by conventional GPCRs (Tall et al., 2003). If this is also the case for Ric-8B, it would mean that activation of G-protein by this putative GEF would depend on GPCR activation. That is, GPCR binding would lead to dissociation of Gα and Gβγ subunits, and Ric-8B would then bind to Gα and promote the exchange of GDP for GTP before it reassociates with Gβγ. This would ultimately lead to the amplification of the signal generated through receptor activation. Alternatively, it could be that monomeric Gα subunits residing on internal cellular membranes are the targets for the Ric-8 proteins (Pimplikar and Simons, 1993; Denker et al., 1996).

In our results with HEK293 cells, we could only detect increased Gαolf activity by Ric-8B in the presence of an activated GPCR. This result is in agreement with the fact that Ric-8A cannot activate heterotrimeric G-proteins and indicates that the function of the Ric-8 proteins depends on receptor activation. A protein member of the synembryn family (denominated hSyn) was also identified in humans (Klattenhoff et al., 2003). This protein, which is able to interact with Gαs and Gαq, is translocated to the plasma membrane in neuronal-derived cultured cells in response to isoproterenol or carbachol, indicating that its activity is also dependent on receptor activation (Klattenhoff et al., 2003).

A putative GEF for Gαolf

It is known that the efficiency of signal transduction by GPCRs varies among different tissues. The α2 adrenergic receptors, for example, differ in their coupling to adenylyl cyclase when expressed over a range of receptor or G-protein concentrations in the two different cell types NIH-3T3 and PC12 (Sato et al., 1995). This is probably caused by the presence of different types of accessory proteins that might influence or enhance ligand-induced signaling. Although Gαolf is almost identical to Gαs in the amino acid sequence, it has been known for a long time that Gαolf works poorly in heterologous systems when compared with Gαs (Jones and Reed, 1989; Jones et al., 1990). We show here that addition of Ric-8B to such a system can significantly improve the function of Gαolf. This indicates that, indeed, accessory factors present in the olfactory neurons can play important roles in the efficiency of receptor coupling to Gαolf. β2AR has motifs that are conserved among ORs, and it has been demonstrated recently that the mouse β2AR can substitute for an OR in glomerular formation when expressed from an OR locus (Feinstein et al., 2004). These results indicate that there are functional similarities between β2AR and ORs. It remains to be determined whether functional expression of ORs in heterologous systems, which is usually very inefficient (for review, see Mombaerts, 2004), can also be improved by coexpression with Gαolf and Ric-8B.

The olfactory system has evolved to detect rapid chemical signal changes in the environment. Rapid activation and rapid inactivation of the cAMP signal are fundamental for the proper functioning of the system. To be able to follow a scent trail released by an escaping prey or to be able to detect all of the chemical information present in a transient wind blow carrying the scent of a predator, it would be greatly advantageous to have an amplification mechanism for the olfactory signaling. Nevertheless, additional experiments should be performed to determine the physiological role of Ric-8B in vivo. It will be interesting, for example, to determine how mice that are deficient for Ric-8B compare with wild-type mice in terms of olfactory responses.

A role for Ric-8B in the brain

Gαolf is expressed at high levels in some regions in the brain. Some of these regions, such as the striatum, nucleus accumbens, and olfactory tubercle, show very little or no expression of Gαs, suggesting that Gαolf may also function as an essential signaling G-protein in more central brain regions. The regions that express Gαolf are responsible for the initiation and patterning of important behaviors, such as the control of the locomotor activity, drug reward, and habit formation (Gerdeman et al., 2003). In addition, these regions have been implicated in a series of neuropsychiatric and motor disorders, such as Parkinson's and Huntington diseases and Tourette's syndrome (Graybiel, 2000; Gerdeman et al., 2003). It was demonstrated that Gαolf knock-out mice show altered locomotor activities in response to cocaine or other D1 receptor agonists (Zhuang et al., 2000). Thus, Gαolf present in the striatum probably plays a role in the signal transduction mediated by D1 receptors in this area. It was also demonstrated that adenosine A2a receptors in striatum couple to Gαolf (Kull et al., 2000). Because we found that Ric-8B is specifically coexpressed with Gαolf in these same regions, it is possible that this putative GEF plays an important role in controlling critical aspects of the striatum function.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnológico. We thank Linda Buck, Steve Lieberles, and James Contos for critically reading this manuscript. We are also grateful to Ronaldo B. Quaggio for help with the acquisition of microscope images. We also thank Glaucia M. Souza and Rachel Bagatini for assistance during the Northern blot experiments.

Correspondence should be addressed to Bettina Malnic, Departamento de Bioquímica, Instituto de Química, Universidade de São Paulo, C.P. 26077, CEP 05513-970, São Paulo, Brazil. E-mail: bmalnic@iq.usp.br.

Copyright © 2005 Society for Neuroscience 0270-6474/05/253793-08$15.00/0

L.E.C.V.D. and A.F.M. contributed equally to this work.

References

- Belluscio L, Gold GH, Nemes A, Axel R (1998) Mice deficient in G(olf) are anosmic. Neuron 20: 69-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghard A, Buck LB, Liman ER (1996) Evidence for distinct signaling mechanisms in two mammalian olfactory sense organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 2365-2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boekhoff I, Breer H (1992) Termination of second messenger signaling in olfaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 471-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boekhoff I, Tareilus E, Strotmann J, Breer H (1990) Rapid activation of alternative second messenger pathways in olfactory cilia from rats by different odorants. EMBO J 9: 2453-2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisy F, Ronnet G, Cunningham A, Juilfs D, Beavo J, Snyder S (1992) Calcium/calmodulin-activated phosphodiasterase expressed in olfactory receptor neurons. J Neurosci 12: 915-923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breer H, Boekhoff I, Tareilus E (1990) Rapid kinetics of second messenger formation in olfactory transduction. Nature 345: 65-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet LJ, Gold GH, Ngai J (1996) General anosmia caused by a targeted disruption of the mouse olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel. Neuron 17: 681-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck L, Axel R (1991) A novel multigene family may encode odorant receptors: a molecular basis for odor recognition. Cell 65: 175-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck LB (2000) The molecular architecture of odor and pheromone sensing in mammals. Cell 100: 611-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TY, Yau KW (1994) Direct modulation by Ca2+-calmodulin of cyclic nucleotide-activated channel of rat olfactory receptor neurons. Nature 368: 545-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cismowski MJ, Takesono A, Ma C, Lizano JS, Xie X, Fuernkranz H, Lanier SM, Duzic E (1999) Genetic screens in yeast to identify mammalian nonreceptor modulators of G-protein signaling. Nat Biotechnol 17: 878-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cismowski MJ, Ma C, Ribas C, Xie X, Spruyt M, Lizano JS, Lanier SM, Duzic E (2000) Activation of heterotrimeric G-protein signaling by a Ras-related protein. J Biol Chem 275: 23421-23424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin BR, Farfel Z, Lustig KD, Julius D, Bourne HR (1993) Substitution of three amino acids switches receptor specificity of Gqα to that of Giα. Nature 363: 274-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denker SP, Mc Caffery JM, Palade GE, Insel PA, Farquhar MG (1996) Differential distribution of alpha subunits and beta gamma subunits of heterotrimeric proteins in Golgi membranes of the exocrine pancreas. J Cell Biol 133: 1027-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein P, Bozza T, Rodriguez I, Vassalli A, Mombaerts P (2004) Axon guidance of mouse olfactory sensory neurons by odorant receptors and the β2 adrenergic receptor. Cell 117: 833-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley RL, Brent R (1994) Interaction mating reveals binary and ternary connections between Drosophila cell cycle regulators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 12980-12984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestein S (2001) How the olfactory system makes scents of scents. Nature 413: 211-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdeman GL, Partridge JG, Lupica CR, Lovinger DM (2003) It could be habit forming: drugs of abuse and striatal synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci 26: 184-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golemis E, Serebriiskii I, Finley R, Kolonin M, Gyuris J, Brent R (1999) Interaction trap/two-hybrid system to identify interacting proteins. In: Current protocols in molecular biology, pp 20.1.1-20.1.40. New York: Wiley. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Graybiel AM (2000) The basal ganglia. Curr Biol 10: R509-R511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A (1998) G proteins and small GTPases: distant relatives keep in touch. Science 280: 2074-2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervé D, Lévi-Strauss M, Marey-Semper I, Verney C, Tassin J-P, Glowinski J, Girault JA (1993) Golf and Gs in rat basal ganglia: possible involvement of Golf in the coupling of dopamine D1 receptor with adenylyl cyclase. J Neurosci 13: 2237-2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervé D, Le Moine C, Corvol JC, Belluscio L, Ledent C, Fienberg AA, Jaber M, Studler JM, Girault JA (2001) Gαolf levels are regulated by receptor usage and control dopamine and adenosine action in the striatum. J Neurosci 21: 4390-4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DT, Reed RR (1989) Golf: an olfactory neuron-specific G-protein involved in odorant signal transduction. Science 244: 790-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DT, Masters SB, Bourne HR, Reed RR (1990) Biochemical characterization of three stimulatory GTP-binding proteins. J Biol Chem 265: 2671-2676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klattenhoff C, Montecino M, Soto X, Guzmán L, Romo X, García MLA, Mellstrom B, Naranjo JR, Hinrichs MV, Olate J (2003) Human brain synembryn interacts with Gsα and Gqα and is translocated to the plasma membrane in response to isoproterenol and carbachol. J Cell Physiol 195: 151-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kull B, Svenningsson P, Fredholm BB (2000) Adenosine A2A receptors are colocalized with and activate Golf in rat striatum. Mol Pharmacol 58: 771-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurahashi T, Menini A (1997) Mechanism of odorant adaptation in the olfactory receptor cell. Nature 385: 725-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H-Y, Wenzel-Seifert K, Seifert R (2001) The olfactory G-protein Gαolf possesses a lower GDP-affinity and deactivates more rapidly than Gsαshort: consequences for receptor-coupling and adenylyl cyclase activation. J Neurochem 78: 325-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Denker BM (1999) Interaction of heterotrimeric G protein Gαo with Purkinje Cell Protein-2. J Biol Chem 274: 10685-10688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KG, Rand JB (2000) A role for RIC-8 (Synembrin) and GOA-1 (Goα) in regulating a subset of centrosome movements during early embryogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans Genetics 156: 1649-1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KG, Alfonso A, Nguyen M, Crowell JA, Johnson CD, Rand JB (1996) A genetic selection for Caenorhabditis elegans synaptic transmission mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 12593-12598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KG, Emerson MD, McManus JR, Rand JB (2000) RIC-8 (Synembrin): a novel conserved protein that is required for Gqα signaling in the C. elegans nervous system. Neuron 27: 289-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombaerts P (2004) Genes and ligands for odorant, vomeronasal and taste receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 263-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger SD, Lane AP, Zhong H, Leinders-Zufall T, Yau KW, Zufall F, Reed RR (2001) Central role of the CNG4 channel subunit in Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent odor adaptation. Science 294: 2172-2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppel K, Boekhoff I, McDonald P, Breer H, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ (1997) G protein-coupled receptor kinase 3 (GRK3) gene disruption leads to loss of odorant receptor desensitization. J Biol Chem 272: 25425-25428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimplikar SW, Simons K (1993) Regulation of apical transport by a Gs class of heterotrimeric G protein. Nature 362: 456-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronnett GV, Moon C (2002) G proteins and olfactory signal transduction. Annu Rev Physiol 64: 189-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Kataoka R, Dingus J, Wilcox M, Hildebrandt JD, Lanier SM (1995) Factors determining specificity of signal transduction by G-protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem 270: 15269-15276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Ribas C, Hildebrandt JD, Lanier SM (1996) Characterization of a G-protein activator in the neuroblastoma-glioma cell hybrid NG108-15* J Biol Chem 271: 30052-30060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeren-Wiemers N, Gerfin-Moser A (1993) A single protocol to detect transcripts of various types and expression levels in neural tissue and culture cells: in situ hybridization using digoxigenin-labelled cRNA probes. Histochemistry 100: 431-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnarajah S, Dessauer CW, Srikumar D, Chen J, Yuen J, Yilma S, Dennis JC, Morrison EE, Vodyanoy V, Kehrl JH (2001) RGS2 regulates signal transduction in olfactory neurons by attenuating activation of adenylyl cyclase III. Nature 409: 1051-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprang S (2001) GEFs: master regulators of G-protein activation. Trends Biochem Sci 26: 266-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strittmatter SM, Valenzuela D, Kennedy TE, Neer E, Fishman MC (1990) Go is a major growth cone protein subject to regulation by GAP-43. Nature 344: 836-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tall GG, Krumins AM, Gilman AG (2003) Mammalian Ric-8A (synembryn) is a heterotrimeric Gα protein guanine nucleotide exchange factor. J Biol Chem 278: 8356-8362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Zhao AZ, Chan GCK, Baker LP, Impey S, Beavo JA, Storm DR (1998) Phosphorylation and inhibition of olfactory adenylyl cyclase by CaM kinase II in neurons: a mechanism for attenuation of olfactory signals. Neuron 21: 495-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong ST, Trinh K, Hacker B, Chan GCK, Lowe G, Gaggar A, Xia Z, Gold GH, Storm DR (2000) Disruption of the type III adenylyl cyclase gene leads to peripheral and behavioral anosmia in transgenic mice. Neuron 27: 487-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C, Feinstein P, Bozza T, Rodriguez I, Mombaerts P (2000) Peripheral olfactory projections are differentially affected in mice deficient in a cyclic nucleotide-gated channel subunit. Neuron 26: 81-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang X, Belluscio L, Hen R (2000) Golfα mediates dopamine D1 receptor signaling. J Neurosci 20: RC91(1-5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufall F, Leinders-Zufall T (2000) The cellular and molecular basis of odor adaptation. Chem Senses 25: 473-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]