Abstract

In studies of Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis there is an increasing focus on mechanisms of intracellular amyloid-β (Aβ) generation and toxicity. Here we investigated the inhibitory potential of the 42 amino acid Aβ peptide (Aβ1-42) on activity of electron transport chain enzyme complexes in human mitochondria. We found that synthetic Aβ1-42 specifically inhibited the terminal complex cytochrome c oxidase (COX) in a dose-dependent manner that was dependent on the presence of Cu2+ and specific “aging” of the Aβ1-42 solution. Maximal COX inhibition occurred when using Aβ1-42 solutions aged for 3-6 h at 30°C. The level of Aβ1-42-mediated COX inhibition increased with aging time up to ∼6 h and then declined progressively with continued aging to 48 h. Photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins followed by SDS-PAGE analysis revealed dimeric Aβ as the only Aβ species to provide significant temporal correlation with the observed COX inhibition. Analysis of brain and liver from an Alzheimer's model mouse (Tg2576) revealed abundant Aβ immunoreactivity within the brain mitochondria fraction. Our data indicate that endogenous Aβ is associated with brain mitochondria and that Aβ1-42, possibly in its dimeric conformation, is a potent inhibitor of COX, but only when in the presence of Cu2+. We conclude that Cu2+-dependent Aβ-mediated inhibition of COX may be an important contributor to the neurodegeneration process in Alzheimer's disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, amyloid-β, cytochrome oxidase, copper, mitochondria, Tg2576

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurological disorder characterized by the deposition of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and progressive loss of cognitive function (Selkoe, 2001). The degree of cognitive impairment occurs relative to soluble Aβ load (McLean et al., 1999; Naslund et al., 2000), and mutations have been found in familial AD pedigrees that lead to elevated levels of Aβ production, particularly the 42 amino acid form (Aβ1-42), through altered processing of the Aβ precursor protein (APP) (Citron et al., 1992; Selkoe, 2001). Early research into the role of Aβ in AD focused on extracellular fibrillar Aβ as the causative agent for this disease (Pike et al., 1991; Hardy and Higgins, 1992), but there is growing evidence to suggest that the toxic species of Aβ occurs within a soluble, intracellular pool (Hartley et al., 1999; McLean et al., 1999; Dahlgren et al., 2002; Dodart et al., 2002; Walsh et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002).

Despite the apparent link between Aβ and the development of AD, and the consistent feature that the AD brain is under severe oxidative stress (Martins et al., 1986), the underlying biological mechanisms responsible for the neurodegeneration characteristic of this disease remain uncertain. One Aβ-mediated mechanism for the development of AD that has gained some support is mitochondrial dysfunction. Analyses of the AD brain provide evidence for decreased abundance and activity of cytochrome c oxidase (COX) (also known as complex IV) from the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) (Maurer et al., 2000; Cottrell et al., 2001, 2002), decreased glucose metabolism (Duara et al., 1986; Haxby et al., 1986), and ultrastructural changes to the mitochondria (Hirai et al., 2001; Casley et al., 2002b). Furthermore, in vitro studies have shown that the disruption of normal mitochondrial functioning can be achieved by exposure to Aβ. Canevari et al. (1999) and Casley et al. (2002a) observed that when supplied to nonsynaptic brain mitochondria from rats, a truncated form of the Aβ peptide (Aβ25-35) specifically inhibits COX, whereas complexes I and II+III of the ETC remain unaffected. Similarly, Parks et al. (2001) reported Aβ25-35-mediated inhibition of COX, but not the other ETC enzyme complexes, in mitochondria isolated from rat liver. These studies suggest that mitochondrial dysfunction may be at least in part a causative factor in the pathology of AD and that the observed mitochondrial dysfunction may be the result of Aβ-mediated inhibition of COX activity.

We examined the direct effects of Aβ1-42 on activity of the ETC enzyme complexes in mitochondria from cultured human cells. We examined the role of Aβ1-42 oligomerization and the requirement for Cu2+ in the generation of an Aβ solution that is able to exert an inhibitory potential toward COX. In addition, we examined mitochondrial fractions from brains and livers of AD transgenic mice (Tg2576) for the presence of APP and Aβ. Our aims were to determine whether the presence of a particular Aβ species is required to generate Aβ-mediated inhibition of COX and to establish whether Aβ accumulation could be detected within Tg2576 mouse brain mitochondria.

Materials and Methods

Mitochondrial isolation from cultured cells. Leukocytes isolated from whole human blood from healthy donors were transformed with Epstein-Barr virus to yield lymphoblastoid cells (Wallace et al., 1986), which were then maintained in 100 ml cultures at 37°C and 5% (v/v) CO2 in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen). Cells were seeded into 2 L roller bottles in 250 ml, passaged to 1 L after 3 or 4 d growth, and then harvested for the isolation of mitochondria once the cells reached a density of 1.0-1.5 × 106 cells ml-1 in late log growth phase. Intact mitochondria were isolated from lymphoblast cells as described previously (Trounce et al., 1996), except that the final mitochondrial pellet was suspended in EGTA-free isolation buffer.

Mitochondrial isolation from mouse brain and liver. Tg2576 (Hsiao et al., 1996) and wild-type (WT) mice were housed, bred, and genotyped as described previously (Maynard et al., 2002). Mice were killed at 18 months of age by cervical dislocation and then dissected to remove the brains and livers. Total brain mitochondria isolates were prepared from fresh brains using Percoll gradients as described by Anderson and Sims (2000). Fresh liver samples (on ice) were minced to a paste with scissors, diluted to 10% (w/v) with ice-cold isolation buffer (as per cell culture mitochondria isolation buffer), and then homogenized in a Dounce homogenizer (12 strokes loose pestle, 4 strokes tight pestle). The homogenate was centrifuged four times at 600 × g (10 min per spin at 4°C) and then once at 5000 × g (10 min, 4°C); the supernatant fraction was centrifuged each time. Pelleted material from the final spin was resuspended with 20 ml fresh isolation buffer and centrifuged at 5000 × g. The resulting crude mitochondria pellet was purified further by resuspending in isolation buffer containing 14% (v/v) Percoll and fractionating through a Percoll density gradient as described by Anderson and Sims (2000). Aliquots of the initial brain and liver homogenates were stored at -80°C and used for SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis alongside mitochondrial fractions.

Protein content and storage of mitochondria isolates. Total protein in the mitochondria isolates was determined using a modified version of Lowry et al. (1951) as described by Peterson (1977). Mitochondrial protein was determined as the difference between total protein content of the isolates and the BSA content of the isolation buffer. Mitochondrial membranes were disrupted by subjecting the isolates to a 3× freeze-thaw cycle at -80°C, and the isolates were stored in aliquots at -80°C.

Aβ solution preparation. Synthetic Aβ1-42 or Aβ42-1 (W. M. Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Laboratory, Yale University, New Haven, CT) was dissolved in 20 mm NaOH and then diluted with 10× PBS (1.45 m NaCl, 75 mm Na2HPO4, 2.4 mm NaH2PO4, pH 7.2) and MilliQ water to yield a 200 μm Aβ solution with a final pH of 8.0 and 1× PBS concentration. When required, Cu2+ (as a 7 mm CuCl2, 42 mm glycine stock) was added to 400 μm to provide a final Aβ/Cu2+ molar ratio of 1:2. Zn2+, Fe2+, or Fe3+ was added by substituting CuCl2 with ZnCl2, FeSO4, or FeCl3. Aβ and vehicle solutions are referred to with respect to their metal cation form only (Aβ1-42/Cu2+, vehicle/Fe3+, Aβ42-1/Zn2+ etc). Vehicle solutions used as negative controls were identical to the appropriate Aβ solutions but contained no Aβ. Aβ and vehicle solutions were incubated at 30°C for the times specified before their incubation with mitochondrial isolates.

Aβ/mitochondria incubations. Cell-culture mitochondria isolates (10 μl) were incubated with 50 μl Aβ or vehicle solution for 5 min at 30°C and then kept on ice until assayed for enzyme activities. The period on ice before assaying never exceeded 3 min. Using these volumes and an initial 200 μm Aβ solution, the final Aβ concentration in the incubation mixture was 167 μm.

Enzymology. The mitochondrial ETC enzyme complexes I, II, III, and IV (COX) and the mitochondrial matrix enzyme citrate synthase were assayed as described by Trounce et al. (1996). Briefly, complex I was measured as the rate of decylubiquinone-dependent, rotenone-sensitive oxidation of β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide by monitoring ΔAbs at 340 nm; complex II as the rate of decylubiquinone-dependent oxidation of succinate by monitoring the coupled reduction of 2,6-dichloroindolphenol at 600 nm; complex III as the rate of decylubiquinol-dependent, antimycin A-sensitive reduction of cytochrome c at 550 nm; COX as the rate of cyanide-sensitive cytochrome c oxidation at 550 nm; and citrate synthase as the rate of oxaloacetate-dependent reduction of acetyl-CoA by monitoring the coupled reduction of 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) at 412 nm.

Photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins, SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting for synthetic Aβ. Synthetic Aβ species in solution (dimers, trimers, etc.) were cross-linked using photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins (PICUP) (Fancy and Kodadek, 1999), as modified for its application to Aβ preparations by Bitan et al. (2001, 2003a,b). While kept in the dark, 12 μl of Aβ preparation (200 μm total Aβ in monomer equivalents) was added to 6 μl of 1 mm Tris(2,2′-bipyridyl)dichlororuthenium(II) and 6 μl 20 mm ammonium persulfate in 10 mm Na2HPO4, pH 7.4. Cross-linking was initiated by exposing the mixture to a 200 W incandescent light for exactly 0.5 s and then terminated by adding 24 μl of gel loading buffer [100 mm Tris, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 4% (v/v) SDS, 4% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% (w/v) bromophenol blue]. Exposure time was controlled by passing the light through the body of a single-lens reflex camera and setting the shutter speed to 0.5 s. Cross-linked Aβ preparations in loading buffer were kept at -80°C until required for SDS-PAGE analyses. Aβ species were separated on 1-mm-thick 15% Tris-tricine gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, probed with the monoclonal mouse antibody WO2 for human Aβ (Ida et al., 1996), and then reprobed with horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-mouse IgG. Aβ bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagents, Amersham Biosciences, Arlington Heights, IL), and the relative abundance of each Aβ species was determined by densitometry (Scion Image, Frederick, MD).

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting for APP and Aβ in mouse tissues. Proteins (50 μg) in mouse brain and liver samples were diluted with loading buffer [100 mm Tris, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 4% (v/v) SDS, 4% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% (w/v) bromophenol blue], separated on 10-20% Tris-tricine gels (Gradipore, Frenchs Forrest, New South Wales, Australia), and then Western blotted and visualized as described for synthetic Aβ. Purity of the mitochondria samples was determined by reprobing the membrane with HO-1 for endoplasmic reticulum (Stressgen, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada) and then stripping and probing with Porin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for mitochondria.

Results

Soluble Aβ1-42/Cu2+ inhibits COX

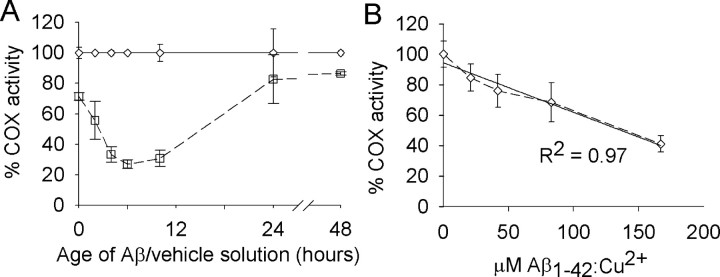

We examined whether aging freshly prepared Aβ1-42/Cu2+ at 30°C would lead to the formation of an Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution with an inhibitory potential toward COX activity. When incubated with mitochondria isolates for 5 min without previous aging, the Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution inhibited COX activity by 28% relative to the vehicle/Cu2+ control (Fig. 1A) (p < 0.001; ANOVA; n = 4 Aβ/vehicle solutions). With aging for up to 6 h, the Aβ1-42/Cu2+-mediated inhibition of COX increased with increasing aging time to 73%. The correlation between aging of the Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution up to 6 h and inhibition of COX activity was linear (R2 = 0.96; p < 0.01; linear regression analysis). With continued aging after 6 h, the inhibitory effect of the Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution began to decrease; by 24 h the inhibitory effect had dropped back to 17%, and by 48 h it was back to 13%.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of COX activity by Aβ1-42 solutions aged in the presence of Cu2+. A, Aβ1-42/Cu2+ (□) and vehicle/Cu2+ (⋄) solutions were aged at 30°C for the times shown and then incubated with mitochondria isolates for 5 min before assaying for COX activity. All activities are expressed relative to the vehicle/Cu2+ control. Error margins represent the SD of the mean (n = 4). COX activity for vehicle/Cu2+-treated mitochondria isolates was 9.38 (±1.12) k · min-1 · mg-1 mitochondrial protein. B, Mitochondria isolates were incubated with Aβ1-42/Cu2+ (aged for 5 h at 30°C) at the concentrations shown and then assayed for COX activity. All activities are expressed relative to the 0 μm Aβ control. Error margins represent the SD of the mean (n = 4). COX activity for 0 μm Aβ-treated mitochondria isolates was 7.23 (±0.63) k · min-1 · mg-1 mitochondrial protein.

Free Cu2+ ions can be lost from solutions with neutral pH because of the time-dependent formation of metal-hydroxy and metal-oxy polymers (Huang et al., 1999). Thus, if free Cu2+ is required for the observed Aβ1-42-mediated inhibition of COX activity, it is possible that the observed decrease in COX inhibition with continued aging of the Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution beyond 6 h was caused by the loss of free Cu2+ from solution. To investigate this possibility, Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solutions were prepared and aged for 48 h at 30°C and then assayed for their effect on COX activity. Consistent with the data shown in Figure 1A, the 48-h-old Aβ1-42/Cu2+ inhibited COX activity by only 27% (data not shown; p < 0.001; ANOVA; n = 4 Aβ/vehicle solutions). The addition of fresh Cu2+ (as 400 μm CuCl2) did not alter the inhibitory effect of the 48-h-old Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution (data not shown; p = 0.11; ANOVA; n = 4 Aβ solutions).

The substrate of COX activity is ferrocytochrome c (reduced form of cytochrome c), and the product is ferricytochrome c (oxidized form). To determine whether Aβ1-42/Cu2+ itself has any effect on the redox state of cytochrome c, the reduced and oxidized forms of cytochrome c were incubated at 30°C for 5 min with Aβ1-42/Cu2+ or vehicle/Cu2+ (both of which had been aged for 5 h), and then their wavelength spectra were determined. In the presence of vehicle/Cu2+, ferrocytochrome c exhibited its typical double-peaked spectrum with absorption maxima at 520 and 550 nm, whereas ferricytochrome c exhibited its broader spectrum with a single absorption maximum at 529 nm. Incubation with Aβ1-42/Cu2+ had no effect on these wavelength spectra (data not shown).

To examine whether the inhibitory effect of the Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution could be attributed to soluble or insoluble forms of the Aβ, an Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution was prepared and then assayed for its effects on COX activity as per other experiments (i.e., the Aβ1-42 solution was aged for 4 h at 30°C in the presence of Cu2+ and then incubated with mitochondrial isolates for 5 min at 30°C before assaying for COX activity). Under these conditions the Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution (“total Aβ1-42/Cu2+”) inhibited COX activity by 54% (data not shown; p < 0.001; ANOVA; n = 3 Aβ/vehicle solutions). Aliquots of the same Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution were then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 5 min, and either the supernatant (“soluble Aβ1-42/Cu2+”) was assayed directly for its effects on COX activity or the insoluble pelleted material (“insoluble Aβ1-42/Cu2+”) was resuspended with vehicle/Cu2+ and then assayed for its effects on COX. All of the inhibitory effect present in the total Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution was recovered in the soluble fraction (53% inhibition of COX; p < 0.001; ANOVA; n = 3 Aβ/vehicle solutions), whereas the insoluble fraction had no effect on COX activity (p = 0.11). It remains to be established whether the present Aβ aging and centrifugation conditions were sufficient for the production and/or precipitation of insoluble Aβ.

To determine the dose-dependent affect of Aβ1-42/Cu2+ on COX activity, a 200 μm Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution was prepared and aged at 30°C for 5 h. Before conducting the 5 min Aβ/mitochondria incubations at 30°C, the Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution was diluted with vehicle solution (without Cu2+) to give final Aβ concentrations of 0, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μm while maintaining the Aβ/Cu2+ molar ratio of 1:2. Using these Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solutions, the final concentrations of Aβ in the Aβ/mitochondria incubation mixture were 0, 21, 42, 83, and 167 μm. Inhibition of COX activity occurred proportional to Aβ1-42/Cu2+ concentration, with inhibition at 59% when the mitochondria were incubated with 167 μm Aβ1-42/Cu2+ (Fig. 1B) (R2 = 0.97; p < 0.01; linear regression analysis).

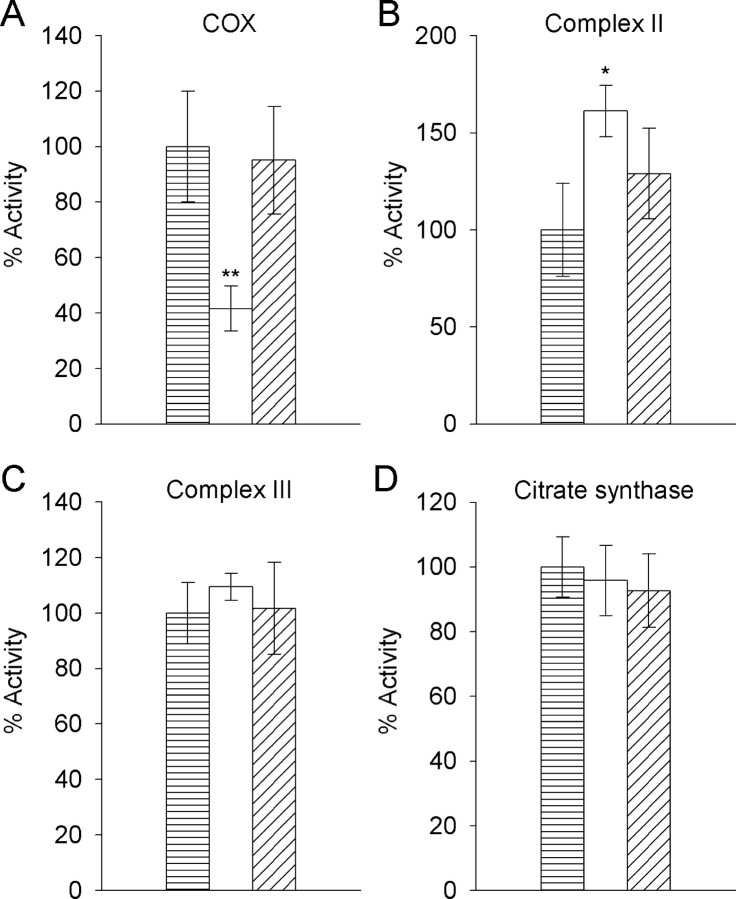

Inhibition by Aβ1-42/Cu2+ is specific to COX

An Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution aged for 5 h at 30°C inhibited COX activity by 58% relative to the vehicle/Cu2+ control (Fig. 2A) (p < 0.001; ANOVA; n = 5 mitochondria isolates); however, the same Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution had no inhibitory effect on complex II, complex III, or citrate synthase activity (Fig. 2B-D). In the presence of Aβ1-42/Cu2+, complex II activity increased 61% (Fig. 2B) (p < 0.05; ANOVA; n = 3 mitochondria isolates). This could be significant to AD pathology if there was an associated increase in the production of free radicals, but it may have been caused by a nonspecific peptide effect because there was no significant difference in complex II activity for Aβ1-42/Cu2+- and Aβ42-1/Cu2+-treated mitochondria (p = 0.71; ANOVA; n = 3 mitochondria isolates). Relative to the vehicle/Cu2+ control, the reverse peptide Aβ42-1/Cu2+ had no effect on any of the enzymes studied. Data for the effects of Aβ1-42/Cu2+ on complex I activity could not be obtained because activity for this enzyme was nondetectable when EGTA was omitted from the mitochondria isolates, even when assayed without treating with Aβ1-42/Cu2+ or vehicle/Cu2+. When EGTA was included in the mitochondria isolates, complex I activity could be detected at 23 nmol · min-1 · mg-1 protein (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Effects of Aβ1-42/Cu2+ and Aβ42-1/Cu2+ on activity of the electron transport chain enzyme complexes II, III, and COX, and the mitochondrial matrix enzyme citrate synthase. Mitochondria isolates were incubated for 5 min with vehicle/Cu2+ (▤), Aβ1-42/Cu2+ (□), or Aβ42-1/Cu2+ (▤) solutions that had been aged for 5 h at 30°C and then assayed for the activity of COX (A), complex II (B), complex III (C), and citrate synthase (D). All activities are expressed relative to the vehicle/Cu2+ control. Error margins represent the SD of the mean (n = 3-5). COX activity in vehicle/Cu2+-treated mitochondria was 7.41 (±1.48) k · min-1 · mg-1 mitochondrial protein. Specific activities (min-1 mg-1 mitochondrial protein) in vehicle/Cu2+-treated mitochondria for complex II, complex III, and citrate synthase were 26.1 (±6.3) nmol succinate, 129.5 (±14.3) nmol cytochrome c, and 231.6 (±21.6) nmol acetyl-CoA, respectively. ANOVA; *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.001 compared with vehicle/Cu2+ control; n = 3-5.

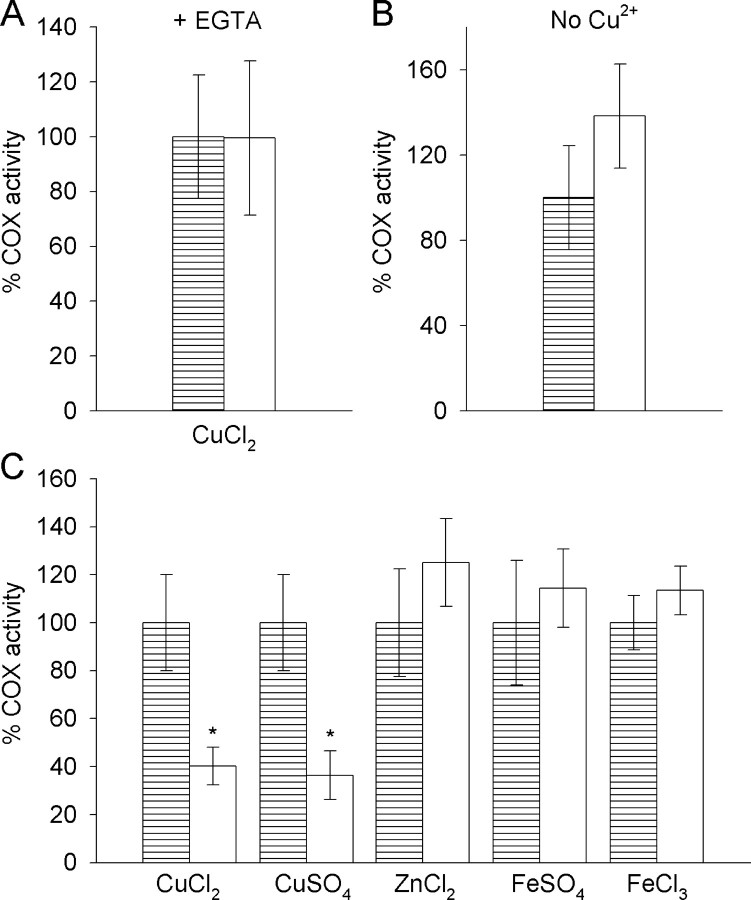

Cu2+ is required for Aβ1-42 inhibition of COX

When 700 μm EGTA was included in the Aβ/mitochondria 5 min incubation before assaying for COX activity, or when Cu2+ was omitted from the Aβ1-42 preparation, no Aβ1-42-mediated inhibition of COX could be detected (Fig. 3A,B)(p = 0.98 and 0.07, respectively; ANOVA; n = 4 mitochondria isolates). Furthermore, no Aβ1-42-mediated inhibition of COX could be detected when Cu2+ was substituted with Zn2+, Fe2+, or Fe3+ (Fig. 3C) (p = 0.13, 0.32, and 0.17 for Zn2+, Fe2+, and Fe3+, respectively; ANOVA; n = 3-5 mitochondria isolates). The counter ion form of the Cu2+ that was supplied, however, had no effect on the inhibitory potential of the Aβ1-42/Cu2+. When using CuCl2, the Aβ1-42/Cu2+ inhibited COX activity by 60% (Fig. 3C) (p < 0.01; ANOVA; n = 4 mitochondria isolates), whereas using CuSO4 caused 63% inhibition (Fig. 3C) (p < 0.001; ANOVA; n = 5 mitochondria isolates).

Figure 3.

The requirement for Cu2+ in Aβ1-42-mediated inhibition of COX activity. Mitochondria isolates were incubated for 5 min with vehicle/Cu2+ (▤) or Aβ1-42/Cu2+ (□) solutions that had been aged for 5 h at 30°C, and subsequent COX activity in the mitochondria isolates was determined. A, EGTA was included in the 5 min incubation at a final concentration of 700 μm, thus providing an EGTA/Cu2+ molar ratio of 2:1. B, Cu2+ was omitted from the Aβ1-42 and vehicle solutions. C, Aβ1-42 and vehicle solutions were prepared and aged with Cu2+ (supplied as CuCl2 or CuSO4), Zn2+ (as ZnCl2), Fe2+ (as FeSO4), or Fe3+ (as FeCl3). All activities are expressed relative to the vehicle controls. Error margins represent the SD of the mean (n = 3-5). ANOVA; *p < 0.001 compared with vehicle controls; n = 3-5.

PICUP analysis of Aβ1-42 species

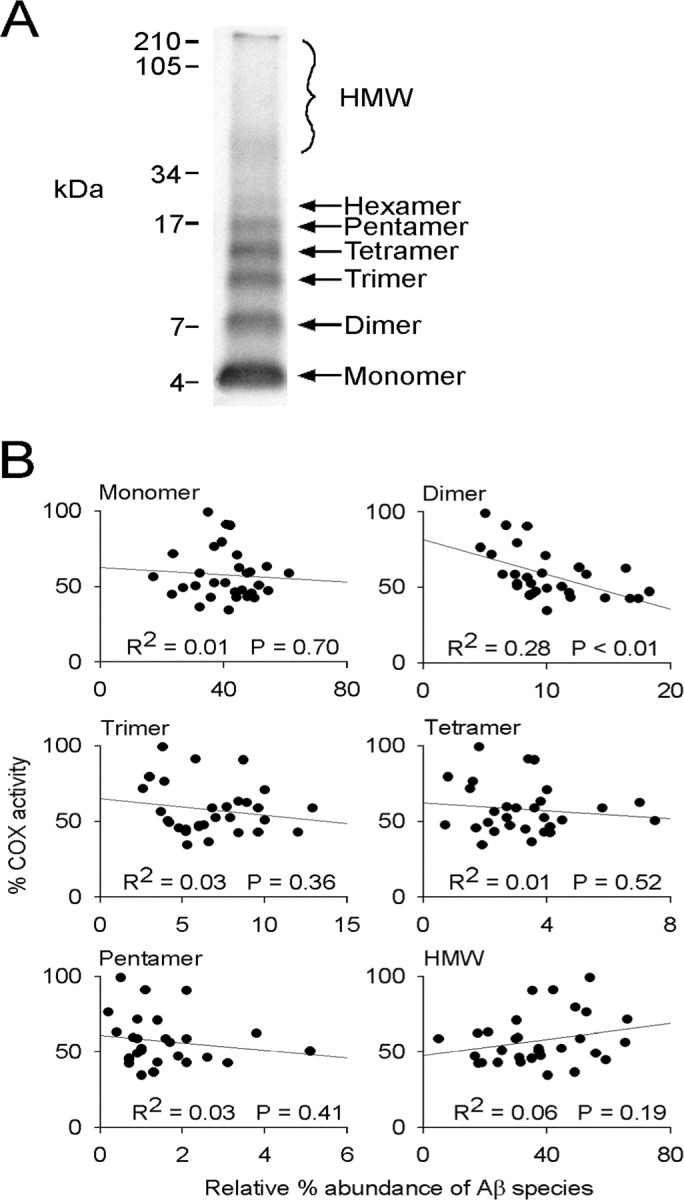

Aβ1-42/Cu2+ was prepared and aged at 30°C as for the other experiments except that after 0, 2, 4, 6, 10, and 24 h aging, aliquots of the Aβ solution were collected and either assayed immediately for its effects on COX activity or cross-linked via PICUP for SDS-PAGE analysis. SDS-PAGE analysis revealed the presence of Aβ1-42 species that correlated by molecular weight to monomers, dimers through to hexamers [low molecular weight (LMW) oligomers], and high molecular weight (HMW) (>45 kDa) Aβ (Fig. 4A). At each time point in the Aβ aging process, the abundance of individual Aβ species was calculated relative to the other Aβ species present at that time. The abundance of monomeric Aβ remained relatively constant throughout the 24 h aging period, accounting for ∼40% of total Aβ at all times. In contrast, the HMW Aβ, presumably consisting of at least some protofibrillar and fibrillar Aβ, increased in abundance with increasing aging time (from ∼15% of total Aβ after 0 h aging to ∼50% after 24 h). Throughout the 24 h aging period, the LMW Aβ oligomers collectively accounted for only ∼20% of the total Aβ. Of these, dimeric Aβ was the most abundant, accounting for ∼10% of total Aβ.

Figure 4.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of Aβ1-42/Cu2+ and the correlation between the abundance of Aβ1-42/Cu2+ species and Aβ-mediated inhibition of COX activity. Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solutions were aged at 30°C for 0, 2, 4, 6, 10, and 24 h and then either cross-linked by PICUP or assayed for their effects on COX activity in mitochondrial isolates. A, Different Aβ species present in the cross-linked samples were resolved on 15% Tris-tricine gels, and their relative abundance, as a percentage of total Aβ, was determined by densitometry. B, The relative abundance of each Aβ species was plotted against percentage COX activity in mitochondria isolates treated with the Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution, and the correlation (R2) between the two was determined. Five Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solutions were aged for the times shown and then assayed for their effects on COX activity, relative to vehicle/Cu2+ solutions aged under the same conditions, or cross-linked and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE. One hundred percent COX activity indicates no Aβ-mediated inhibition relative to the vehicle/Cu2+ control treatment. Significance of the R2 values was determined by linear regression analysis.

Given the distinct pattern of COX inhibition observed when mitochondria isolates were incubated with Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solutions aged for 0-24 h (Fig. 1A), we examined whether the abundance of any particular species of Aβ over the 24 h aging period correlated with COX inhibition. To do this, we plotted Aβ1-42/Cu2+-mediated COX inhibition (as percentage activity relative to COX activity in vehicle/Cu2+-treated mitochondria isolates) against the relative abundance of each Aβ species present within the Aβ1-42/Cu2+ solution at any given time in the aging period. We found that of all the Aβ species detected, only dimeric Aβ exhibited a significant correlation with COX inhibition (Fig. 4B) (R2 = 0.28; p < 0.01; linear regression analysis).

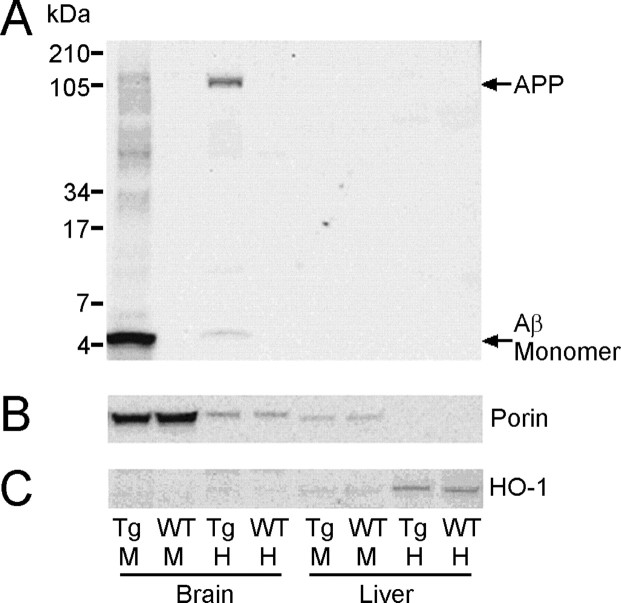

APP and Aβ in 18-month-old Tg2576 mouse brain mitochondria

When 18-month-old Tg2576 mouse brain homogenate was electrophoresed on 10-20% Tris-tricine gradient gels (50 μg of total protein per lane), Western blot analysis revealed the presence of WO2-immunoreactive bands at ∼5 and ∼110 kDa, presumably representing Aβ and APP (Fig. 5A). The ∼5 kDa band comigrated with monomeric Aβ from a sample of cross-linked synthetic Aβ1-42 equivalent to that shown in Figure 4A (data not shown). The same WO2-immunoreactive bands were detected in the Tg2576 mouse brain mitochondrial fraction, with the APP being considerably less abundant, whereas the Aβ was greatly enriched. No WO2 immunoreactivity was observed in either fraction of the WT mouse brain. Purity of the brain mitochondria fraction was established by Western blotting total brain homogenate and brain mitochondria samples with Porin (for mitochondria) and HO-1 (for endoplasmic reticulum, a common contaminant of mitochondria preparations). These analyses revealed both Porin and HO-1 immunoreactivity in the total brain homogenate fraction, but only Porin immunoreactivity in the mitochondria fraction (Figs. 5B, C), suggesting that the mitochondria preparations were relatively free of endoplasmic reticulum.

Figure 5.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of APP and Aβ in brain mitochondria of Tg2576 mice. A, Aβ and APP in total homogenate (H) and mitochondria (M) samples from the brain and liver of 18-month-old Tg2576 (Tg) and wild-type (WT) mice were resolved on 10-20% Tris-tricine gels and Western blotted with WO2 for Aβ/APP. Aβ was greatly enriched in the brain mitochondria of Tg2576 mice but nondetectable in brain mitochondria of age-matched WT controls. Fifty micrograms of total protein (for mitochondria samples) or 30 μg of total protein (for homogenate samples) was loaded per lane. The gels were reprobed with Porin for mitochondria (B) or HO-1 for endoplasmic reticulum (C), and this revealed that the mitochondria fractions were relatively free from endoplasmic reticulum.

COX activity in Tg2576 mouse brain mitochondria

Preliminary analysis of COX activity in purified brain mitochondria from 18-month-old Tg2576 mice showed no differences from controls when mitochondria were prepared in isolation buffer with EGTA (61.5 ± 5.0 k · min-1 · mg-1 mitochondrial protein for Tg2576, 66.0 ± 4.0 for controls; p = 0.37; ANOVA; n = 3 mitochondria isolates) or without EGTA (47.4 ± 0.8 k · min-1 · mg-1 mitochondrial protein for Tg2576, 44.9 ± 2.9 for controls; p = 0.22; ANOVA; n = 3 mitochondria isolates).

Discussion

We found that specific inhibition of the terminal respiratory chain enzyme COX can be obtained when mitochondria isolates are exposed to Aβ1-42, but that maximal inhibition requires specific pre-aging of the Aβ preparation. Inhibition of COX activity increased with Aβ1-42 aging up to 6 h and then declined progressively with continued aging to 48 h. This is consistent with a model in which monomeric Aβ is relatively nontoxic, but the formation of LMW oligomers, a time-dependent process, correlates with an increase in Aβ toxicity. Furthermore, it is consistent with a model in which continued aging of the Aβ solution leads to a decrease in the abundance of the toxic LMW oligomers and an increase in HMW oligomers, and possibly protofibrils and fibrils, all of which are relatively nontoxic. Such a model has been proposed and supported by other studies (Dahlgren et al., 2002; Walsh et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002). To further investigate this model, we correlated the observed temporal pattern of Aβ-mediated COX inhibition with the relative abundance of individual LMW oligomers. To do this, it was essential to first cross-link the Aβ1-42 solutions (using PICUP) because many of the Aβ1-42 LMW oligomers appeared sensitive to denaturing conditions and as such were nondetectable when using SDS-PAGE. We observed that the level of Aβ1-42-mediated COX inhibition correlated significantly with the abundance of dimeric Aβ1-42. No other Aβ1-42 species detected throughout the 48 h aging period (monomers, LMW oligomers from trimers up to hexamers, or HMW Aβ) showed any correlation with the observed COX inhibition. Our data therefore indicate that in vitro inhibition of COX is caused by the time-dependent formation of dimeric Aβ1-42.

The specific inhibition of COX by Aβ, compared with other members of the mitochondrial ETC, is consistent with previously published data (Canevari et al., 1999; Parks et al., 2001; Casley et al., 2002a). These reports generally used a truncated 11 amino acid form of the Aβ (Aβ25-35) to generate their specificity data. Casley et al. (2002a) did demonstrate Aβ1-42-mediated inhibition of purified bovine COX and coupled respiration in rat brain mitochondria but did not assay for its effects on other ETC enzyme complexes. Using Aβ25-35 to demonstrate specific inhibition of COX activity may provide some important data with respect to Aβ domains involved in potential COX-Aβ interactions, but Aβ1-42 is the form of Aβ increasingly implicated in the development of AD and as such may be more indicative of potential Aβ-mediated mechanisms occurring in the AD-affected brain.

The presence of free Cu2+ was essential for the observed Aβ1-42-mediated inhibition of COX activity. Removal of Cu2+, via omission or the addition of the chelator EGTA, alleviated the inhibition of COX. The role for Cu2+ in the observed COX inhibition may be several-fold. It may facilitate Aβ oligomerization (Atwood et al., 1998; Klug et al., 2003), may facilitate the formation of specific Aβ conformers such as dityrosine Aβ (Galeazzi et al., 1999; Curtain et al., 2001; Atwood et al., 2004), or may facilitate Aβ-COX interaction, serving as a ligand. A precedent for the latter scenario may be the adriamycin/Fe3+-mediated inhibition of COX observed by Hasinoff and Davey (1988). These authors found that adriamycin inhibited COX with an inhibition constant of 12 μm when in the presence of Fe3+, and this inhibition was lost when the metal was removed by chelators.

The requirement for free metal cations for Aβ1-42-mediated inhibition of COX activity appeared specific toward Cu2+, because no COX inhibition was detected when using Fe2+, Fe3+, or Zn2+. It is unlikely that this was caused by a limited potential for Aβ to interact with metals other than Cu2+, because it has been shown previously that Aβ binds and interacts with various metals, including Fe2+, Fe3+, and Zn2+ (Atwood et al., 1998). It is possible, therefore, that although Aβ may interact with various metals and these metals differentially affect Aβ conformation (Atwood et al., 2004), its interaction with Cu2+ specifically generates the conditions required to mediate an inhibitory affect on COX activity. Further study is required to determine the nature of this specificity.

The relevance of our findings to the in vivo Aβ-mediated neurodegeneration characteristic of AD is restricted to the assumptions that Aβ has access to mitochondria of the AD-affected brain and that it is present within the mitochondria at concentrations high enough to exert an inhibitory affect on COX activity. With respect to the first assumption, recent reports provide some evidence that Aβ does occur within brain mitochondria of human AD patients and transgenic AD mice. Anandatheerthavarada et al. (2003) provided evidence that the full-length APP can insert into the outer membrane of mitochondria from cortical neurons of transgenic AD mice, whereas Lustbader et al. (2004) colocalized Aβ with mitochondria in human AD-affected brains. In addition to this, the data that we present here have shown readily detectable levels of Aβ associated with the mitochondria fraction in brains from Tg2576 mice, without the requirement for stringent solublization procedures. These data indicate that Aβ may be delivered to the mitochondria after processing of the APP within other regions of the cell or that Aβ is produced de novo within the mitochondria, with APP processing at the mitochondrial membrane generating an intra-mitochondrial pool of Aβ. Evidence for the latter possibility has emerged recently with Hansson et al. (2004) demonstrating the presence of active γ-secretase complexes within purified rat brain mitochondria.

Whether Aβ can accumulate within mitochondria of the ADaffected brain to concentrations required to inhibit COX to the extent shown here remains to be determined. To partly address this, we measured COX activity in 18-month-old Tg2576 and WT mice. Although we observed considerably elevated levels of Aβ in Tg2576 brain mitochondria, we did not find decreased COX activity as recently reported by Anandatheerthavarada et al. (2003). Another recent report using PC12 cells overexpressing Swedish mutant APP also found a moderate decrease in COX activity in transfected cells (Keil et al., 2004). The mitochondrial preparations in both of these reports appear to have excluded EGTA or EDTA, whereas we used the standard EGTA-containing isolation medium for our mouse brain mitochondrial preparations. Because Aβ-mediated inhibition of COX appears to be reversible by the addition of EGTA (Fig. 4B), we prepared EGTA-free mitochondria isolates from 18-month-old mice. Although COX activity was decreased by the removal of EGTA, there was no difference in COX activity between WT and Tg2576 mice. Further work is clearly needed to determine whether variations in the mitochondrial isolation or COX assay conditions can affect such results. Importantly, the extent to which COX activity is decreased in Tg2576 mouse brain mitochondria, as reported by Anandatheerthavarada et al. (2003), may be determined by the region of brain from which the mitochondria are isolated.

The concentrations of Aβ used in this study to generate 50-70% inhibition of COX activity may be considered high with respect to other Aβ toxicity assays, particularly cell-based toxicity assays in which low micromolar ranges of Aβ are generally used to generate a significant decline in cell viability. Such assays generally use considerably longer incubation periods to observe any Aβ-mediated effects (i.e., up to several days as opposed to 5 min for our Aβ/mitochondria isolate incubations) and therefore are likely to be indicative of different toxicity mechanisms. Nonetheless, to partly address these concerns, our data indicate that the observed inhibition of COX activity was caused by the formation of dimeric Aβ1-42, and this species at any given time accounted for only ∼10% of the total Aβ. Thus, when the mitochondria isolates were incubated with Aβ at a final concentration of 167 μm, it can be argued that they were exposed to only ∼17 μm of the toxic species. If correct, dimeric Aβ1-42 shows a similar potency to cyanide, a classic inhibitor of COX. Chronic exposure of the mitochondria to relatively lower concentrations of Aβ, a scenario probably more representative of conditions within the AD-affected brain, may well lead to physiologically significant levels of COX inhibition. Our data clearly demonstrate the accumulation of Aβ within the mitochondria fraction of Tg2576 mouse brain, relative to the total brain homogenate. Further studies are needed to determine whether the subcellular distribution of Aβ-rich mitochondria coincides with specific regions of a single cell, such as the synapse, that correlate with the histopathology characteristic of AD.

The in vitro data presented here are consistent with a model in which the formation of dimeric Aβ1-42, when in the presence of free Cu2+, leads to inhibited activity of the mitochondrial ETC enzyme COX. Aβ1-42 and Cu2+ levels are elevated in regions of the AD-affected brain (Lovell et al., 1998; McLean et al., 1999; Naslund et al., 2000), and COX is decreased in the AD brain (Maurer et al., 2000; Cottrell et al., 2001, 2002). Our data are therefore consistent with the possibility that the formation of dimeric Aβ1-42 in the presence of Cu2+, and subsequent inhibition of COX, may be an important contributor to the neurodegeneration of AD.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant 208798. We also thank Prana Biotechnology Ltd. and Schering AG Berlin for support.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Ian Trounce, Centre for Neuroscience, The University of Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia. E-mail: i.trounce@unimelb.edu.au.

Copyright © 2005 Society for Neuroscience 0270-6474/05/250672-08$15.00/0

References

- Anandatheerthavarada HK, Biswas G, Robin M-A, Avadhani NG (2003) Mitochondrial targeting and a novel transmembrane arrest of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein impairs mitochondrial function in neuronal cells. J Cell Biol 161: 41-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MF, Sims NR (2000) Improved recovery of highly enriched mitochondrial fractions from small brain tissue samples. Brain Res Protoc 5: 95-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood CS, Moir RD, Huang X, Scarpa RC, Bacarra NME, Romano DM, Hartshorn MA, Tanzi RE, Bush AI (1998) Dramatic aggregation of Alzheimer Aβ by Cu(II) is induced by conditions representing physiological acidosis. J Biol Chem 273: 12817-12826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood CS, Perry G, Zeng H, Kato Y, Jones WD, Ling K-Q, Huang X, Moir RD, Wang D, Sayre LM, Smith MA, Chen SG, Bush AI (2004) Copper mediates dityrosine cross-linking of Alzheimer's amyloid-β. Biochemistry 43: 560-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitan G, Lomakin A, Teplow DB (2001) Amyloid β-protein oligomerization: prenucleation interactions revealed by photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins. J Biol Chem 276: 35176-35184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitan G, Vollers SS, Teplow DB (2003a) Elucidation of primary structure elements controlling early amyloid β-protein oligomerization. J Biol Chem 278: 34882-34889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitan G, Kirkitadze MD, Lomakin A, Vollers SS, Benedek GB, Teplow DB (2003b) Amyloid β-protein (Aβ) assembly: Aβ40 and Aβ42 oligomerize through distinct pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 330-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canevari L, Clark JB, Bates TE (1999) β-Amyloid fragment 25-35 selectively decreases complex IV activity in isolated mitochondria. FEBS Lett 457: 131-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casley CS, Canevari L, Land JM, Clark JB, Sharpe MA (2002a) β-Amyloid inhibits integrated mitochondrial respiration and key enzyme activities. J Neurochem 80: 91-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casley CS, Land JM, Sharpe MA, Clark JB, Duchen MR, Canevari L (2002b) β-Amyloid fragment 25-35 causes mitochondrial dysfunction in primary cortical neurons. Neurobiol Dis 10: 258-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citron M, Oltersdorf T, Haass C, McConlogue L, Hung A, Seubert P, VigoPelfrey C, Lieberberg I, Selkoe DJ (1992) Mutation of the beta-amyloid precursor protein in familial Alzheimer's disease increases beta-protein production. Nature 360: 672-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell DA, Blakely EL, Johnson MA, Ince PG, Turnbull DM (2001) Mitochondrial enzyme-deficient hippocampal neurons and choroidal cells in AD. Neurology 57: 260-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell DA, Borthwick GM, Johnson MA, Ince PG, Turnbull DM (2002) The role of cytochrome c oxidase deficient hippocampal neurones in Alzheimer's disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 28: 390-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtain CC, Ali F, Volitakis I, Cherny RA, Norton RS, Beyreuther K, Barrow CJ, Masters CL, Bush AI, Barnham KJ (2001) Alzheimer's disease amyloid-β binds copper and zinc to generate an allosterically ordered membrane-penetrating structure containing superoxide dismutase-like subunits. J Biol Chem 276: 20466-20473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren KN, Manelli AM, Stine WBJ, Baker LK, Krafft GA, LaDu MJ (2002) Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-β peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. J Biol Chem 277: 32046-32053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodart JC, Bales KR, Gannon KS, Greene SJ, DeMattos RB, Mathis C, DeLong CA, Wu S, Wu X, Holtzman DM, Paul SM (2002) Immunization reverses memory deficits without reducing brain Aβ burden in Alzheimer's disease model. Nat Neurosci 5: 452-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duara R, Grady C, Haxby J, Sundaram M, Cutler NR, Heston L, Moore A, Schlageter N, Larson S, Rapoport SI (1986) Positron emission tomography in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 36: 879-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancy DA, Kodadek T (1999) Chemistry for the analysis of protein-protein interactions: rapid and efficient cross-linking triggered by long wave-length light. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 6020-6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeazzi L, Ronchi P, Franceschi C, Giunta S (1999) In vitro peroxidase oxidation induces stable dimers of beta-amyloid (1-42) through dityrosine bridge formation. Amyloid 6: 7-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson CA, Frykman S, Farmery MR, Tjernberg LO, Nilsberth C, Pursglove SE, Ito A, Winblad B, Cowburn RF, Thyberg J, Ankarcrona M (2004) Nicastrin, presenilin, APH-1, and PEN-2 form active γ-secretase complexes in mitochondria. J Biol Chem 279: 51654-51660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JA, Higgins GA (1992) Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 256: 184-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley DM, Walsh DM, Ye CP, Diehl T, Vasquez S, Vassilev PM, Teplow DB, Selkoe DJ (1999) Protofibrillar intermediates of amyloid β-protein induce acute electrophysiological changes and progressive neurotoxicity in cortical neurons. J Neurosci 19: 8876-8884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasinoff BB, Davey P (1988) The iron(III)-adriamycin complex inhibits cytochrome c oxidase before its inactivation. Biochem J 250: 827-834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby J, Grady C, Duara R, Schlageter N, Berg G, Rapoport SI (1986) Neocortical metabolic abnormalities precede non-memory cognitive deficits in early Alzheimer's type dementia. Arch Neurol 43: 882-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai K, Aliev G, Nunomura A, Fujioka H, Russell RL, Atwood CS, Johnson AB, Kress Y, Vinters HV, Tabaton M, Shimohama S, Cash AD, Siedlak SL, Harris PL, Jones PK, Petersen RB, Perry G, Smith MA (2001) Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci 21: 3017-3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G (1996) Correlative memory deficits, Aβ elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science 274: 99-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Cuajungco MP, Atwood CS, Hartshorn MA, Tyndall JD, Hanson GR, Stokes KC, Leopold M, Multhaup G, Goldstein LE, Scarpa RC, Saunders AJ, Lim J, Moir RD, Glabe C, Bowden EF, Masters CL, Fairlie DP (1999) Cu(II) potentiation of Alzheimer Aβ neurotoxicity: correlation with cell-free hydrogen peroxide production and metal reduction. J Biol Chem 274: 37111-37116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ida N, Hartmann T, Pantel J, Schroder J, Zerfass R, Forstl H, Sandbrink R, Masters CL, Beyreuther K (1996) Analysis of heterogeneous βA4 peptides in human cerebrospinal fluid and blood by a newly developed sensitive Western blot assay. J Biol Chem 271: 22908-22914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil U, Bonert A, Marques CA, Scherping I, Weyermann J, Strosznajder JB, Muller-Spahn F, Haass C, Czech C, Pradier L, Muller WE, Eckert A (2004) Amyloid-beta induced changes in nitric oxide production and mitochondrial activity lead to apoptosis. J Biol Chem 279: 50310-50320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klug G, Losic D, Subasinghe SS, Aguilar M-I, Martin LL, Small DH (2003) β-Amyloid protein oligomers induced by metal ions and acid pH are distinct from those generated by slow spontaneous ageing at neutral pH. Eur J Biochem 270: 4282-4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell MA, Robertson JD, Teesdale WJ, Campbell JL, Markesbery WR (1998) Copper, iron and zinc in Alzheimer's disease senile plaques. J Neurol Sci 158: 47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ (1951) Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193: 265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustbader JW, Cirilli M, Lin C, Xu HW, Takuma K, Wang N, Caspersen C, Chen X, Pollak S, Chaney M, Trinchese F, Liu S, Gunn-Moore F, Lue L-F, Walker DG, Kuppasamy P, Zewier ZL, Arancio O, Stern D, Yan SD, Wu H (2004) ABAD directly links Aβ to mitochondrial toxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Science 304: 448-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins RN, Harper CG, Stokes GB, Masters CL (1986) Increased cerebral glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity in Alzheimer's disease may reflect oxidative stress. J Neurochem 46: 1042-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer I, Zierz S, Moller HJ (2000) A selective defect of cytochrome c oxidase is present in brain of Alzheimer disease patients. Neurobiol Aging 21: 455-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard CJ, Cappai R, Volitakis I, Cherny RA, White AR, Beyreuther K, Masters CL, Bush AI, Li QX (2002) Overexpression of Alzheimer's disease amyloid-β opposes the age-dependent elevations of brain copper and iron. J Biol Chem 277: 44670-44676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CA, Cherny RA, Fraser FW, Fuller SJ, Smith MJ, Beyreuther K, Bush AI, Masters CL (1999) Soluble pool of Aβ amyloid as a determinant of severity of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol 46: 860-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund J, Haroutunian V, Mohs R, Davis KL, Davies P, Greenard P, Buxbaum JD (2000) Correlation between elevated levels of amyloid β-peptide in the brain and cognitive decline. JAMA 283: 1571-1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks JK, Smith TS, Trimmer PA, Bennett JPJ, Parker WDJ (2001) Neurotoxic Aβ peptides increase oxidative stress in vivo through NMDA-receptor and nitric-oxide-synthase mechanisms, and inhibit complex IV activity and induce a mitochondrial permeability transition in vitro J Neurochem 76: 1050-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL (1977) A simplification of the protein assay method of Lowry et al. which is more generally applicable. Anal Biochem 83: 346-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike CJ, Walencewicz AJ, Glabe CG, Cotman CW (1991) Aggregation-related toxicity of synthetic beta-amyloid protein in hippocampal cultures. Euro J Pharmacol 207: 367-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ (2001) Alzheimer's disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev 81: 741-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trounce IA, Kim YL, Jun AS, Wallace DC (1996) Assessment of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in patient muscle biopsies, lymphoblasts, and transmitochondrial cell lines. Methods Enzymol 264: 484-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace DC, Yang J, Ye J, Lott MT, Oliver NA, McCarthy J (1986) Computer prediction of peptide maps: assignment of polypeptides to human and mouse mitochondrial DNA genes by analysis of two-dimensional-proteolytic digest gels. Am J Hum Genet 38: 461-481. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ (2002) Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo Nature 416: 535-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H-W, Pasternak JF, Kuo H, Ristic H, Lambert MP, Chromy B, Viola KL, Klein WL, Stine WB, Krafft GA, Trommer BL (2002) Soluble oligomers of β amyloid (1-42) inhibit long-term potentiation but not long-term depression in rat dentate gyrus. Brain Res 924: 133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]