Abstract

NMDA receptors are ligand-gated ion channels permeable to calcium and play a critical role in excitatory synaptic transmission, synaptic plasticity, and excitotoxicity. They are heteromeric complexes of NR1 combined with NR2A-D and/or NR3A-B subunits that are activated by glutamate and glycine and whose activity is modulated by allosteric modulators. In this study, patch-clamp recordings from human embryonic kidney 293 cells expressing NR1/NR2 receptors were used to study the molecular mechanism of the endogenous neurosteroid 20-oxo-5β-pregnan-3α-yl sulfate (3α5βS) action at NMDA receptors. 3α5βS was a twofold more potent inhibitor of responses mediated by NR1/NR2C-D receptors than those mediated by NR1/NR2A-B receptors. The structure of the extracellular loop between the third and fourth transmembrane domains of the NR2 subunit was found to be critical for the neurosteroid inhibitory effect. The degree of 3α5βS-induced inhibition of responses to glutamate was voltage independent, with recovery lasting several seconds. In contrast, application of 3α5βS in the absence of agonist had no effect on the subsequent response to glutamate made in the absence of the neurosteroid. A kinetic model was developed to explain the use-dependent action of 3α5βS at NMDA receptors. In accordance with the model, 3α5βS was a less potent inhibitor of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs and responses induced by a short application of 1 mm glutamate than of those induced by a long application of glutamate.

These results suggest that 3α5βS is a use-dependent but voltage-independent inhibitor of NMDA receptors, with more potent action at tonically than at phasically activated receptors. This may be important in the treatment of excitotoxicity-induced neurodegeneration.

Keywords: neurosteroids, NMDA receptor, inhibition, patch-clamp recording, recombinant receptors, culture

Introduction

NMDA receptors, a subtype of ionotropic glutamatergic receptors, mediate a slow component of EPSCs and participate in different forms of synaptic plasticity. However, their overactivation can induce excitotoxicity that may lead to symptoms characteristic of severe diseases of the nervous system in man (Doble, 1999; Sattler et al., 2000); (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993; Liu et al., 2004). Structurally, NMDA receptors are heteromeric complexes that consist of different combinations of three subunit types: NR1, NR2, and/or NR3 (Dingledine et al., 1999). Receptors composed of NR1 and NR2 subunits require two coagonists for activation: glycine, which binds to NR1, and glutamate, which binds to NR2 (Kuryatov et al., 1994; Laurie and Seeburg, 1994).

NMDA receptor activity can be influenced by exogenous and endogenous ligands, including neurosteroids. These compounds are of steroid origin, having a direct nongenomic effect on neuron excitability (Paul and Purdy, 1992). They are both synthesized de novo in the CNS and modified to neuroactive compounds from circulating precursors and can reach a high local concentration (Mellon and Griffin, 2002; Kawato et al., 2003). It has been well established that neurosteroids exert a positive, negative, or combined effect on NMDA receptors (Wu et al., 1991; Bowlby, 1993; Park-Chung et al., 1994; Horak et al., 2004). Pregnenolone sulfate (PS), an endogenously occurring neurosteroid, acts in a subunit-dependent manner as a combined positive and negative modulator of NMDA receptors (Malayev et al., 2002; Horak et al., 2004). The mechanism of action of PS associated with a positive effect is disuse dependent (i.e., NMDA receptor affinity for PS is decreased during receptor activation) and involves an increase in the peak probability of the NMDA receptor opening (Po). In contrast, 20-oxo-5β-pregnan-3α-yl sulfate [pregnanolone sulfate (3α5βS)], also a naturally occurring neurosteroid that differs from PS in a single unsaturated bond, has an inhibitory action at NMDA receptors (Park-Chung et al., 1994; Abdrachmanova et al., 2001). Although the molecular mechanism of 3α5βS action at NMDA receptors is only partially understood, its synthetic analog 3α5β hemisuccinate ester has been shown to have a neuroprotective effect, both in vitro (hippocampal neurons) and in vivo (spinal cord ischemia model), thereby indicating its potential therapeutic use (Weaver et al., 1998; Lapchak, 2004).

In the present study, we examined the mechanism of action of 3α5βS using whole-cell and single-channel recordings from neurons and human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells transfected with NR1 and NR2A-D subunits of the NMDA receptor. Our results show that 3α5βS is a use-dependent but voltage-independent inhibitor that exerts its effect by reducing the peak Po of NMDA receptor channels. Its inhibitory action is weaker for responses mediated by NMDA receptors activated by synaptically released glutamate than those tonically activated by the agonist.

Materials and Methods

All experiments were performed in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive (86/609/EEC) and with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Hippocampal cultures. Primary dissociated hippocampal cultures were prepared from 1- to 2-d-old postnatal rats using established methods (for details, see Mayer et al., 1989). Rats were decapitated, and the hippocampi were dissected. Trypsin digestion, followed by mechanical dissociation, was used to prepare a cell suspension. Single cells were plated at a density of 100,000 cells/cm2 onto a confluent glial feeder layer prepared 2 weeks earlier. Neuronal cultures were maintained in a medium composed of MEM, 10% horse serum, and a nutrient supplement consisting of transferrin, insulin, selenium, corticosterone, triiodothyronine, and progesterone. A metabolic inhibitor, 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine, was used to suppress cell division.

Transfection and maintenance of HEK293 cells. HEK293 cells (ATTC number CRL1573; American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) were cultured in Opti-mem I (Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD) with 5% fetal bovine serum at 37°C. The day before transfection, cells were plated in 24-well plates (2 × 105 cells per well) in 0.5 ml of their normal growth medium and became confluent on the day of transfection. Equal amounts (0.3 μg) of cDNAs coding for NR1, NR2, and green fluorescent protein (pQBI 25; Takara, Tokyo, Japan) were mixed with 2 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). DNA–Lipofectamine complexes were added to HEK293 cells for 5 h. The cells were then trypsinized, resuspended in Opti-mem I containing 1% fetal bovine serum supplemented with 20 mm MgCl2, 1 mm d, l-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid, and 3 mm kynurenic acid, and plated on 31 mm poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips.

The following genes encoding NMDA receptor subunits were used: NR1–1a (GenBank accession number U08261) (Hollmann et al., 1993), NR1–1b (GenBank accession number U08263) (Hollmann et al., 1993), NR2A (GenBank accession number D13211) (Ishii et al., 1993), NR2B (GenBank accession number M91562) (Monyer et al., 1992), NR2C (GenBank accession number M91563) (Monyer et al., 1992), and NR2D (GenBank accession number L31611) (Monyer et al., 1994). NR2A3C4A (NR2AM1-S632CV644-M834AL824-V1464) chimera was a generous gift from Dr. G. Westbrook (Oregon Health and Science University, Vollum Institute, Portland, OR) (Krupp et al., 1998; Vissel et al., 2002).

Animals and slice preparation. Neocortical rat slices were prepared from juvenile Wistar rats of either sex (postnatal day 13–14). The brains were rapidly removed, hemisected, and transferred to cold (4°C) artificial CSF (ACSF) of the following composition (in mm): 130 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 28 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, and 25 glucose (gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2 to a nominal pH of 7.4). Brain slices 250 μm thick were cut using a vibratome (DTK-1000; Dosaka, Kyoto, Japan) and incubated in the ACSF at a temperature of 36°C for 45 min. Slices were maintained at room temperature (6–8 h) before being placed in a recording chamber, in which they were continually perfused with ACSF at a rate of 3 ml/min.

Recording from cultured cells and drug application. Experiments were performed 24–48 h after the end of HEK293 transfection; neurons maintained in culture for 5–8 d were used. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were made with a patch-clamp amplifier (Axopatch 1D; Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) after capacitance and series resistance (<10 MΩ) compensation of 80–90% (Hamill et al., 1981; Stuart et al., 1993). Agonist-induced responses were low-pass filtered at 1 kHz with an eightpole Bessel filter (Frequency Devices, Haverhill, MA), digitally sampled at 5 kHz, and analyzed using pClamp software version 9 (Axon Instruments). Patch pipettes (3–4 MΩ) pulled from borosilicate glass were filled with an intracellular solution containing the following (in mm): 125 gluconic acid, 15 CsCl, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 3 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, and 2 ATP-Mg salt, pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH.

Pipettes for outside-out recording were coated with Sylgard (Dow Corning, Brussels, Belgium) and had a resistance of 5–10 MΩ. Single-channel currents were filtered at 2 kHz with an eight-pole Bessel filter, sampled at 20 kHz, and analyzed using pClamp software. Openings were defined as a transition from closed to open state using a 50% threshold criterion. Openings briefer than 255 μs (1.5× filter rise time) were excluded from the analysis (Colquhoun and Sakmann, 1985).

Mean current (MI) was calculated as follows:

|

(1) |

where Ai and ti are the amplitude and duration of individual NMDA receptor channel openings, and d is duration of data sample (usually 15–30 s). Relative effect (RE) of neurosteroid on NMDA-induced receptor channel activity was defined as follows:

|

(2) |

where MISteroid and MIControl are mean currents induced by NMDA receptor channel openings in the presence of neurosteroid and control extracellular solution.

Extracellular solution (ECS) contained the following (in mm): 160 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, and 0.2 CaCl2, pH adjusted to 7.3 with NaOH. In some experiments, the concentration of CaCl2 was increased to 2 mm, and 1 mm MgCl2 was added as indicated. Single-channel recordings were made using ECS containing 0.7 mm CaCl2 and 0.2 mm EDTA. NMDA was used as an agonist to activate native NMDA receptors, recombinant NMDA receptors when fast deactivation of response was desirable (see Fig. 2 B), and receptors in outside-out patches. Glycine (10 μm) (except in experiments aimed to determine peak Po, when it was 30 μm), an NMDA receptor coagonist, was present in the control and test solutions. TTX (0.5 μm) and bicuculline methochloride (5 μm) were used in experiments on cultured hippocampal neurons. 3α5βS solutions were made from freshly prepared 20 mm stock in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). Control experiments were performed in extracellular solution containing DMSO at the same concentration that was present in solutions containing steroids.

Figure 2.

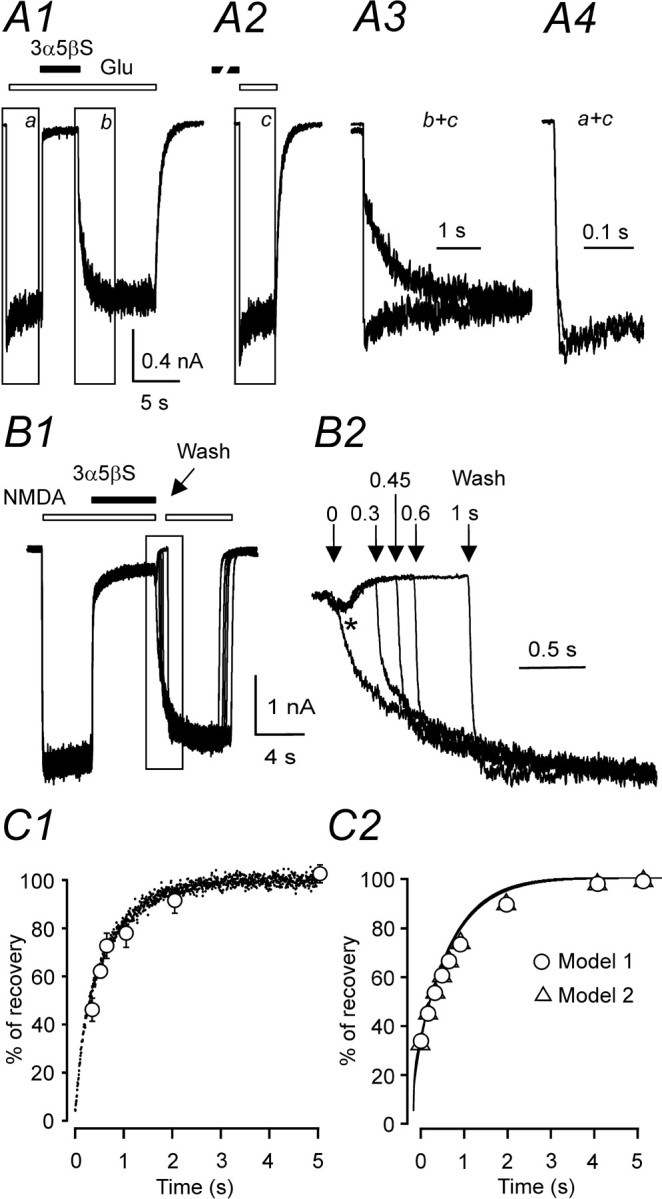

3α5βS is a use-dependent inhibitor of NMDA receptor channels. Examples of records obtained from HEK293 cells transfected with NR1–1a and NR2B. A1, Response to coapplication of 300 μm 3α5βS and 1 mm glutamate (Glu) made after the onset of the response to the agonist was inhibited by 95.3% and recovered from the inhibition on a slow timescale. A2, The onset of the response to application of 1 mm glutamate made immediately after preapplication of 300μm 3α5βS for 37 s was rapid, similar to the control glutamate response from A1. A3, To illustrate the difference in the time course of responses to glutamate made after coapplication of 3α5βS and glutamate (b; boxed area in A1) and that made after preapplication of 3α5βS (c; boxed area in A2), both responses are shown superimposed on an expanded time-scale. A4, The rise time of the responses to glutamate made after preapplication of 3α5βS (c; boxed area shown in A2) was similar to that of control response to 1 mm glutamate (a; boxed area shown in A1). B1, Five consecutive responses to 100 μm NMDA, coapplication of 3α5βS (300 μm), and recovery after varying durations (0, 0.3, 0.45, 0.6, and 1 s) of the neurosteroid washout in the absence of agonist (Wash) are shown. B2, The recovery from inhibition is shown on an expanded timescale. Note that the application of control extracellular solution immediately after coapplication of neurosteroid and NMDA resulted in an after-response (indicated by asterisk). C1, Analysis of the rate of 3α5βS unbinding from NMDA receptors in the absence of the agonist. Data points (open circles) are averaged values of the normalized amplitude of the quick phase of the response to agonist reapplication plotted versus duration of the neurosteroid washout in the absence of agonist. Error bars represent SD; n = 6. Mean time course of the recovery of NMDA-induced responses made immediately after coapplication of 3α5βS and NMDA (neurosteroid dissociation from liganded receptors) is represented by dots (scatter plot; traces recorded in 6 cells were digitally averaged). C2, Model 1 and model 2 (for values of the rate constants, see diagram of NMDA receptor states in Fig. 8 B, Table 2) were used to simulate the response to 1 mm glutamate made immediately after coapplication of 300 μm 3α5βS and 1mm glutamate. Recovery from inhibition in the continuous presence of glutamate (lines) and recovery from inhibition after varying durations (0–5 s) of the neurosteroid washout in the absence of agonist (circles and triangles for model 1 and model 2, respectively).

A microprocessor-controlled multibarrel fast perfusion system, with a time constant of solution exchange around cells of ∼10 ms, was used to apply test and control solutions (Vyklicky et al., 1990). To study the deactivation kinetics of glutamate responses and the peak Po, small lifted cells were used. A brief application of glutamate (6 and 20 ms as indicated) was made by a stepping motor-controlled movement of double-barreled theta tubings (Hilgenberg, Malsfeld, Germany), and 10–90% rise time was 0.58 ± 0.12 ms (n = 5).

Peak Po was calculated according to Jahr (1992) and Chen et al. (1999) as follows:

|

(3) |

Parameters a and b are defined as follows:

|

(4) |

where QPostMK is the total charge transfer of the response induced by a brief application of glutamate recorded after a single application of glutamate made in the presence of 20 μm (+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5,10-imine maleate (MK-801), and QControl is the total charge transfer of control glutamate-induced response; and

|

(5) |

where QMK20 is the charge transfer that occurs within 20 ms after the beginning of the glutamate response made in the presence of 20 μm MK-801, and QMK is the total charge transfer of the response induced by glutamate made in the presence of MK-801.

Experiments were performed at 23–26°C at a holding potential of –60 mV, except when indicated otherwise.

Recording from slices. Neocortical neurons were visualized in slices using a combination of near-infrared and differential interference contrast microscopy (Axioskop-FS; Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Pyramidal neurons in the layer II/III were identified by their position in the cortical slices, triangular somatic shape, and bases of apical dendrites. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings (Hamill et al., 1981; Stuart et al., 1993) were made using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments) at room temperature (23–26°C). To elicit EPSCs, a second pipette filled with extracellular solution and positioned in layer I ∼50–100 μm from the postsynaptic neuron was used. Current pulses of constant amplitude (10–30 μA) and duration (0.5 ms) were applied at a 30 s intervals. EPSCs were recorded at a holding potential of +40 mV with no correction for the liquid junction potential (+9 mV). The responses were filtered at 2 kHz with an eight-pole Bessel filter, sampled at 5 or 10 kHz, and analyzed using pClamp software. NMDA receptor EPSCs were recorded in the presence of control and test solutions. A solution containing neurosteroid was prepared from ACSF bubbled with O2/CO2 for at least 30 min, to which an appropriate amount of 20 mm stock 3α5βS in DMSO was added. This solution was kept in contact with the carbogen atmosphere without bubbling to avoid neurosteroid precipitation. Control experiments were performed in ACSF containing DMSO at the same concentration that was present in test solution containing the steroid. Both the control and test solutions were routinely supplied with CNQX (5 μm), 10 μm bicuculline methochloride, 1 μm strychnine, and 10 μm glycine.

The drugs were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) or Tocris Cookson (Avonmouth, UK). Neurosteroid, 3α5βS, was synthesized by H.C. according to a previously published method (Arnostova et al., 1992), and its purity (>98%) was repeatedly tested using nuclear magnetic resonance, thin-layer chromatography, and elemental analyses.

Statistics. Results are presented as mean ± SD, with n equal to the number of cells studied; statistical comparison of groups was performed using Student's t test or a one-way ANOVA. p < 0.05 was used to determine the significance.

Kinetic modeling. To describe the effects of 3α5βS on NMDA receptor channels, we have adopted the kinetic model of NR1/NR2B receptor function proposed recently by Banke and Traynelis (2003). Simulations and fitting were performed using Gepasi software (version 3.21) (Mendes, 1993, 1997; Mendes and Kell, 1998).

Results

3α5βS inhibition is influenced by the NMDA receptor subunit composition

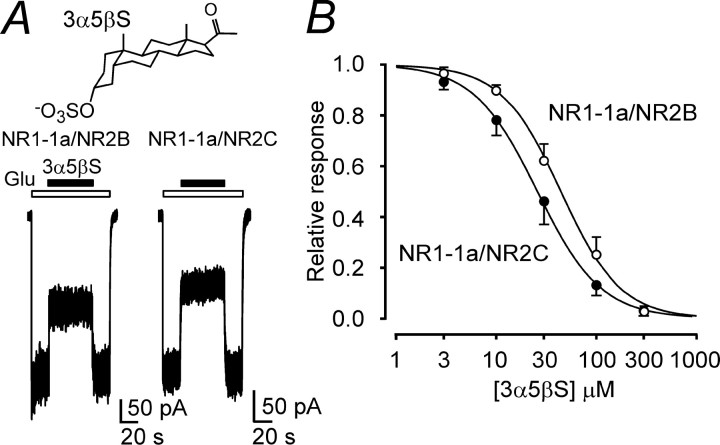

To investigate the influence of the composition of the NMDA receptor on the effect of 3α5βS, cDNAs encoding for the NR1 and NR2 subunits were cotransfected into HEK293 cells. Fig. 1A shows control responses to the fast application of glutamate (1 mm) in HEK293 cells transfected with NR1–1a and NR2B subunits recorded in the presence of 10 μm glycine, no added Mg2+, and 0.2 mm Ca2+. The responses to a coapplication of 30 μm 3α5βS and glutamate made after the onset of the response to glutamate were inhibited, but less in NR1–1a/NR2B receptors than in NR1–1a/NR2C receptors. The results of the dose–response analysis indicate significantly (approximately twofold) lower potency of 3α5βS to inhibit NR1–1a/NR2A-B receptors and native receptors in cultured hippocampal neurons than to inhibit NR1–1a/NR2C-D receptors (Table 1). No significant differences were found in the mean values of the Hill coefficient (h), which varied from 1.2 to 1.5. These result agree well with those published recently by Malayev et al. (2002).

Figure 1.

The effect of 3α5βS at NMDA receptors is dependent on the receptor subunit composition. A, Examples of traces obtained from HEK293 cells transfected with cDNAs encoding NR1–1a/NR2B and NR1–1a/NR2C receptors. 3α5βS (30 μm) was applied simultaneously with 1 mm glutamate (duration of 3α5βS and glutamate application is indicated by filled and open bars, respectively). Chemical structure of 3α5βS is shown on the top. B, Concentration–response curves for the 3α5βS effect at NR1–1a/NR2B and NR1–1a/NR2C receptors. Data points are averaged values of normalized responses from HEK293 cells transfected with NR1–1a/NR2B (n = 5) and NR1–1a/NR2C (n = 5). Error bars represent SD. The relative glutamate-induced responses (I) recorded in the presence of 3α5βS (3–300 μm) and determined in individual cells were fit to the following logistic equation: I = 1/(1 + ([3α5βS]/IC50)h), where IC50 is the concentration of 3α5βS that produces a 50% inhibition of agonist-evoked current, [3α5βS] is the 3α5βS concentration, and h is the apparent Hill coefficient. Smooth curves are plotted by mean parameters listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Concentration dependence of the effect of 3α5βS on the NMDA receptor response

|

Subunits |

IC50 |

h |

n |

|---|---|---|---|

| NR1-1a/NR2A | 50.0 ± 8.0 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 6 |

| NR1-1a/NR2B | 44.4 ± 9.8 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 5 |

| NR1-1a/NR2C | 25.6 ± 4.8 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 5 |

| NR1-1a/NR2D | 30.1 ± 2.3 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 5 |

| NR1-1b/NR2B | 40.6 ± 4.8 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 6 |

| NR1-1a/NR2A3C4A | 12.7 ± 2.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 5 |

| Neurons |

41.6 ± 5.7 |

1.2 ± 0.1 |

6 |

The table shows mean ± SD values of the IC50 and Hill coefficient (h) (with n equal to the number of cells studied) obtained from the logistic equation fit (see legend to Fig. 1) of relative glutamate (1 mm) responses recorded in the presence of 3α5βS (3-300 μm) in HEK293 cells transfected with recombinant NMDA receptors and 100 μm NMDA in cultured hippocampal neurons (Neurons).

We have shown recently that PS, a neurosteroid structurally similar to 3α5βS, has a positive and negative effect on NMDA receptors and further that the structure of the extracellular M3–M4 loop of the NR2 subunit is critical for the expression of both effects (Malayev et al., 2002; Horak et al., 2004, 2005). To explore the molecular basis of 3α5βS action at NR2 subunits, which may be similar to the inhibitory effect of PS, we used a chimera (NR2A3C4A) in which the extracellular M3–M4 loop of the NR2A subunit, which is less sensitive to the inhibitory effect of 3α5βS, was exchanged for the homologous region of the NR2C subunit, which is more sensitive to the inhibitory effect of 3α5βS. Analysis of the dose–response effect of 3α5βS on chimeric receptors (NR1–1a/NR2A3C4A) indicated a significant increase in the neurosteroid potency compared with the effects of 3α5βS at NR1–1a/NR2A receptors (Table 1). These results stress the importance of the M3–M4 loop of the NR2 subunit for the 3α5βS effect; however, they also indicate that there may be other structural and/or functional characteristics of the receptor that affect the neurosteroid effect. Next, experiments were performed to test the role of the NR1 subunit. NR1 subunits exist in eight splice variants differing by the presence (denoted b) or absence (denoted a) of a 21 amino acid insert in the extracellular domain of the N terminus (Hollmann et al., 1993). The potency of 3α5βSto inhibit glutamate responses mediated by NR1–1b/NR2B receptors was not significantly different from its potency to inhibit responses mediated by NR1–1a/NR2B receptors.

3α5βS is a use-dependent inhibitor

We have shown previously that PS is a disuse-dependent NMDA receptor modulator with action that depends on the relative timing of the application of agonist and neurosteroid (Malayev et al., 2002; Horak et al., 2004). To test whether 3α5βS has an action similar to PS at NMDA receptors, two protocols of 3α5βS and glutamate applications were used: (1) a coapplication of 3α5βS and glutamate made after the onset of the response to glutamate and (2) a sequential application of glutamate after preapplication of 3α5βS for 37 s. Figure 2A1 shows responses of NR1–1a/NR2B receptors to a coapplication of 3α5βS (300 μm) with glutamate made after the onset of the response. The neurosteroid induced almost complete inhibition (96.8 ± 1.1%; n = 5) of responses to a saturating concentration of glutamate (1 mm; three orders of magnitude higher than the glutamate EC50). After cessation of the coapplication of 3α5βS, the response to glutamate recovered on a slow timescale, with complex kinetics, characterized by a fast and a slow time course of recovery (10–90% recovery time was 2.7 ± 0.2 s; n = 5). Similar results in terms of the degree of 3α5βS inhibition and the time course of recovery from the inhibition were observed when NMDA (100 μm; threefold higher concentration than the NMDA EC50) was used to study the neurosteroid-induced inhibition in cultured hippocampal neurons.

Subsequent experiments were designed to test the effect of 3α5βS on subsequent responses to glutamate or NMDA when 3α5βS is preapplied in the absence of NMDA receptor agonist. As can be seen from records in Figure 2A, the response to 1 mm glutamate made after a preapplication of 300 μm 3α5βS was significantly faster than that made after coapplication of 3α5βS and glutamate and was not significantly different from that induced by the control response to 1 mm glutamate (made without the neurosteroid preapplication). There were no significant differences in 10–90% rise time between NR1–1a/NR2B receptor responses activated by a low-affinity agonist (500 μm NMDA; 12 ± 2 ms; n = 6) and those activated after a preapplication of 3α5βS (300 μm) (13 ± 3 ms; n = 6). These results show that the inhibitory action of 3α5βS at NMDA receptors depends on the receptor activation, and they indicate a neurosteroid use-dependent mechanism of action on this type of glutamate receptors.

Differences in the time course of NMDA receptor responses made after preapplication and coapplication of 3α5βS indicate that the 3α5βS binding kinetics differs substantially for agonist-liganded and non-agonist-liganded receptors. Next, experiments were performed that aimed to determine the time course of 3α5βS unbinding from NMDA receptors after agonist washout. In these experiments, neurosteroid washout of varying durations (0.3–5 s) in the absence of NMDA receptor agonist was introduced after a coapplication of 100 μm NMDA and 300 μm 3α5βS. The NR1–1a/NR2B receptor response after reapplication of NMDA demonstrated both quickly and slowly rising phases (Fig. 2B2). It is tempting to conclude that the presence of a quick phase reflects the proportion of receptors that unbound the neurosteroid in the absence of agonist. Figure 2C1 shows the results of experiments in which the rate of recovery from 3α5βS inhibition of agonist-activated receptors (continuous line) was compared with recovery after varying durations of NMDA washout (dots). Although detailed comparison is complicated by desensitization, the rate of 3α5βS unbinding follows a similar time course regardless of NMDA receptor activation. This implies that the rate of neurosteroid unbinding (in contrast to the neurosteroid binding) is similar for activated and nonactivated receptors.

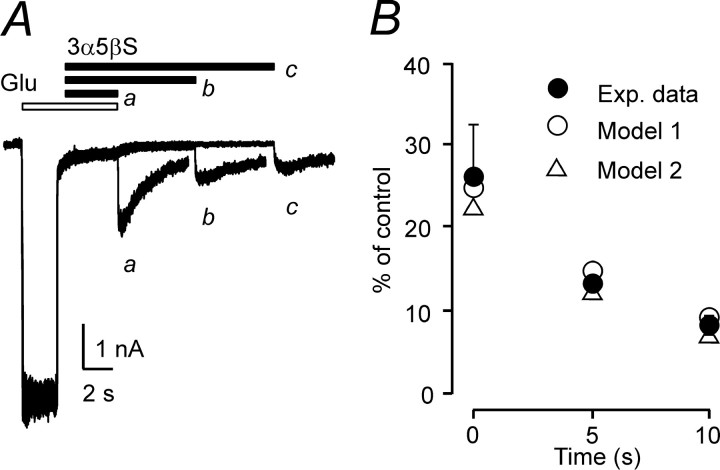

Figure 3A (trace a) shows that the application of control extracellular solution immediately after coapplication of 300 μm 3α5βS and 1 mm glutamate resulted in an after-response that was 26.2 ± 6.4% (n = 6) of the control response to glutamate. After coapplication of 1 mm glutamate and 300 μm 3α5βS, the occurrence of the after-response was delayed if application of extracellular solution containing 300 μm 3α5βS was interposed for 5 and 10 s before application of control extracellular solution (Fig. 3A, traces b, c). The graph of the amplitude of the after-response as a function of duration of 3α5βS application (Fig. 3B) indicates that dissociation of glutamate from the NR1–1a/NR2B receptor was decelerated by the neurosteroid. These results suggest the existence of neurosteroid-induced conformational state(s) of the NMDA receptor channel complex that prevent dissociation of the glutamate from the neurosteroid-modulated NMDA receptor. If this hypothesis is true, then 3α5βS dissociation will allow an agonist-bound NMDA receptor channel to open before agonist dissociation, resulting in a macroscopic after-response.

Figure 3.

Delayed agonist dissociation from 3α5βS-bound receptors. A, Three consecutive NR1–1a/NR2B receptor responses (plotted overlaid) to 1 mm glutamate (Glu) when 300 μm 3α5βS was applied after the start of glutamate application. After removal of glutamate and 3α5βS, an inward tail current developed, with 10–90% rise time of 67 ms and an amplitude of 31.7% of the control response to glutamate; the tail current decayed exponentially with a time constant of 1843 ms (a). When 3α5βS was applied for 5 s (b) and 10 s (c) after removal of glutamate and before application of extracellular solution, the amplitude of the tail current was 12.3 and 9.1% of the control, respectively. B, Graph of the relative amplitude of the after-response expressed as a function of duration of 3α5βS application (applied after coapplication of glutamate and neurosteroid and before application of extracellular solution). Simulations using rate constants of model 1 and model 2 (Fig. 8 B, Table 2) predict existence of an after-response. The amplitude of the after-response slowly diminishes as a function of duration of 3α5βS application.

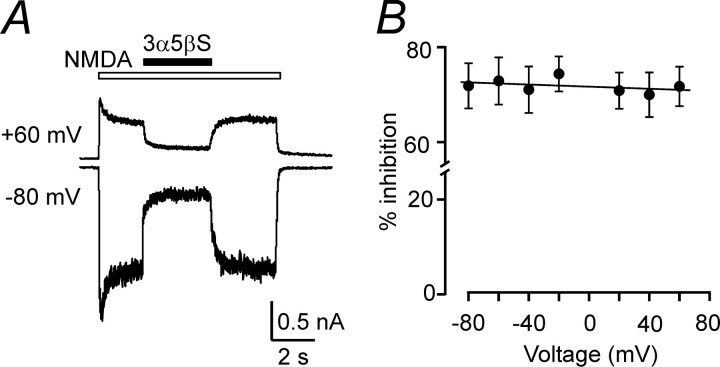

Use-dependent inhibition may be produced by the binding of a charged compound inside the ion channel pore, resulting in a voltage-dependent action. Because positively charged compounds produce a voltage-dependent block of NMDA receptor channels, it is not surprising that the effect of a negatively charged compound, such as 3α5βS, is voltage independent at responses induced in NR1–1a/NR2B receptors by 100 μm NMDA at holding potentials of –80 to +60 mV (Fig. 4). This agrees well with conclusions drawn from studies of 3α5βS action at native NMDA receptors (Park-Chung et al., 1994; Abdrachmanova et al., 2001).

Figure 4.

3α5βS is a voltage-independent inhibitor of NMDA receptor channels. A, Responses to 100μm NMDA recorded from an HEK293 cell transfected with NR1–1a/NR2B receptors and voltage clamped at –80 and +60 mV; 100μm 3α5βS was applied at times indicated by the filled bar. The inhibitory effect is similar at both membrane potentials. B, Analysis of the current-to-voltage relationship of the 3α5βS effect recorded from five cells.

3α5βS decreases peak Po of NMDA receptors

Next, experiments were performed that aimed to determine the mechanism by which 3α5βS induces inhibition of NMDA receptor responses. Several mechanisms were considered. The degree of inhibition induced by 30 μm 3α5βS was not dependent on a glutamate concentration of 43.1 ± 2.0 and 42.0 ± 1.3% (n = 5) for 1 mm and 1 μm glutamate, respectively (these agonist concentrations are, respectively, three orders of magnitude higher than and equal to the glutamate EC50). In addition, responses to 1 mm glutamate made in the absence or continuous presence of 30 μm 3α5βS show a similar degree of macroscopic desensitization. This argues against neurosteroid-induced change in the agonist binding and desensitization as the principal mechanisms by which the NMDA receptor channel activity is inhibited.

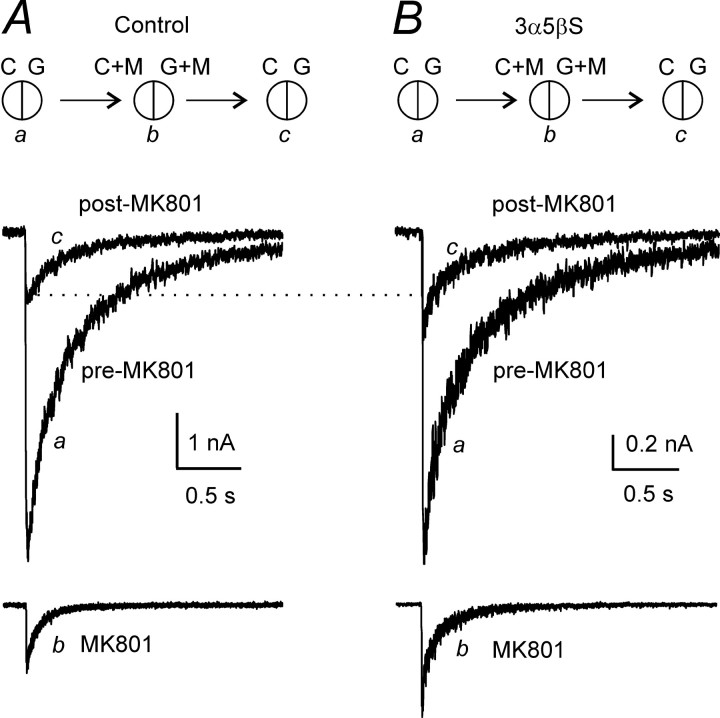

Following the protocol used by Jahr (1992) and Chen et al. (1999), an open NMDA receptor channel blocker, MK-801, was used as an experimental tool to determine the peak Po of NR1–1a/NR2B receptor channels. Peak Po in control cells was determined in three steps, as described by Jahr (1992) and Chen et al. (1999) and used in our recent experiments (Horak et al., 2004). After a cell was lifted, consecutive 20 ms applications of agonist (1 mm glutamate with 30 μm glycine) were recorded. These were repeated at 20 s intervals for stabilization of peak current amplitude in at least three consecutive records. In the second phase, a single response was evoked in the presence of 20 μm MK-801 in both the control and agonist solutions (Fig. 5A). Subsequent applications of glutamate made in the absence of MK-801 elicited currents with smaller amplitudes but similar time courses compared with the pre-MK-801 responses (Fig. 5A). After washout of MK-801, the charge transfer by the response to glutamate was reduced by 84% compared with the control response made before the MK-801 application. To estimate the peak Po for the peak current, we followed the analysis used by Jahr (1992) and Chen et al. (1999) and measured the fraction of the total charge transfer that occurred during a 20 ms application of glutamate in the presence of 20 μm MK-801; this was 11.7 ± 3.5% (n = 6). The peak Po [calculated as the product of the relative decrease of the charge transfer of the response to glutamate after MK-801 application and the relative charge transfer that occurred within 20 ms after the beginning of glutamate application in the presence of MK-801 (Eq. 3)] was calculated to be 9.9 ± 2.5% (n = 6), which is similar to that reported for the same receptor channel composition by Chen et al. (1999).

Figure 5.

Analysis of the effect of 3α5βS on peak Po of NR1–1a/NR2B receptors. Superimposed traces showing currents evoked by 1 mm glutamate applied for 20 ms before (a; pre-MK-801) and after (c; post-MK-801) a single application of glutamate made in the presence of 20 μm MK-801 in both agonist and control solutions (b; MK-801). Glutamate-evoked response was made in the presence of control solution (A) or solution containing 3α5βS(B); 100μm 3α5βS was present in all solutions: C, G, C+M, and G+M. Insets in A and B illustrate the tip of the stepping-motor-controlledθ-tube and the solutions used for recording. C, Control extracellular solution; G, 1 mm glutamate; M, 20 μm MK-801. Responses illustrated in A and B are from different cells.

The same protocol was used to estimate the peak Po of NR1–1a/NR2B receptor channels affected by 3α5βS. Responses to a 20 ms application of 1 mm glutamate made in the continuous presence of 3α5βS (100 μm) were recorded before and after (Fig. 5B) a single response to the application of 3α5βS and glutamate made in the presence of 20 μm MK-801 in the control and agonist solution (Fig. 5B). The analysis showed that, after washout of MK-801, the charge transfer by the response to glutamate recorded in the continuous presence of 3α5βS was reduced by 75% compared with the response made before the application of MK-801. In the presence of 20 μm MK-801, 5.9 ± 0.8% (n = 6) of the charge transfer occurred within 20 ms after the beginning of the glutamate application (Fig. 5B). The estimated value of the peak Po of the NR1–1a/NR2B receptor channels affected by 3α5βS (100 μm) was significantly decreased, to 4.5 ± 0.6% (n = 6). An independent set of experiments was performed to determine the degree of 3α5βS (100 μm) inhibition of responses to a 20 ms application of 1 mm glutamate in lifted HEK293 cells. The peak amplitude of responses in the presence of 100 μm 3α5βS was inhibited by 59 ± 5% (n = 5), similar to the decrease of the peak Po (by 55%).

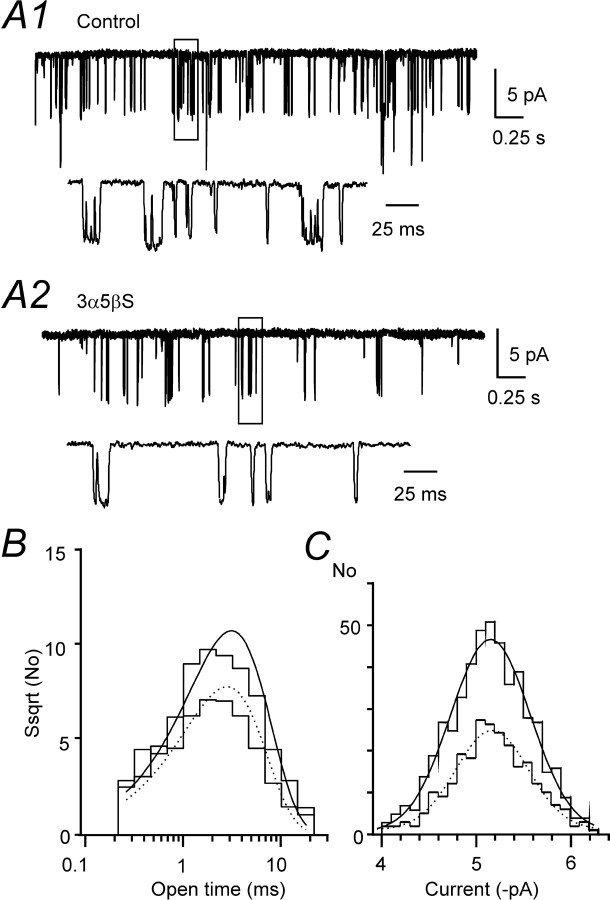

We also tested the effect of 3α5βS (100 μm) on the single-channel activity induced by the application of NMDA (10 μm) in outside-out patches isolated from HEK293 cells expressing NR1–1a/NR2B receptors and recorded in the presence of 0.5 mm Ca2+ (0.7 mm CaCl2 and 0.2 mm EDTA) and Mg2+-free extracellular solution at –95 mV. Figure 6 shows an example of the inhibitory effect of 3α5βS on the NMDA-induced single-channel activity. The relative degree of inhibition [expressed as the ratio of mean current induced by NMDA receptor channel openings recorded in the presence of 3α5βS to the control activity (Eqs. 1, 2)] was 61.9 ± 14.4% (n = 6), which is similar to the effect of the neurosteroid on the whole-cell NMDA receptor responses. In the presence of 3α5βS (100 μm), the frequency of NMDA receptor channel openings was significantly reduced, by 54.2 ± 11.2% (n = 6) relative to the control, and the mean open time of NMDA receptor channel openings was significantly shortened from τ = 3.02 ± 0.39 ms (n = 6) recorded in the control to τ = 2.73 ± 0.43 ms (n = 6) in the presence of 3α5βS. In contrast, no significant difference was observed in the distribution of NMDA receptor channel amplitudes recorded in the control (5.2 ± 0.2 pA; n = 6) and the presence of 3α5βS (5.3 ± 0.2 pA; n = 6). The results of the single-channel analysis are compatible with 3α5βS-induced diminution of the peak Po of NMDA receptor channels and indicate that the neurosteroid affects mainly the rate constant of channel opening rather than a channel closing.

Figure 6.

Effect of 3α5βS on single NMDA receptor channel activity. A, Example of single-channel currents evoked by 10 μm NMDA (Control) and those recorded in the presence of 100 μm 3α5βS (3α5βS) in an outside-out patch isolated from HEK293 cells transfected with NR1–1a/NR2B receptors and held at a potential of –95 mV. Calibration applies to both records. Boxed regions of the responses are displayed below on the expanded timescale. B, Open time distribution (square root of frequency) was fitted by a single-exponential component (τ = 3.0 ms; control, continuous line and τ = 2.7 ms; 3α 5βS, dashed line).C, The distribution of single-channel amplitudes was fitted by a single Gaussian component (–5.15 pA; control, continuous line and –5.17 pA; 3α5βS, dashed line). Amplitude and open time distribution are based on an analysis of a 20 s record of control activity (505 openings) and the same duration of activity recorded in the presence of 3α5βS (254 openings).

The effect of 3α5βS on EPSCs

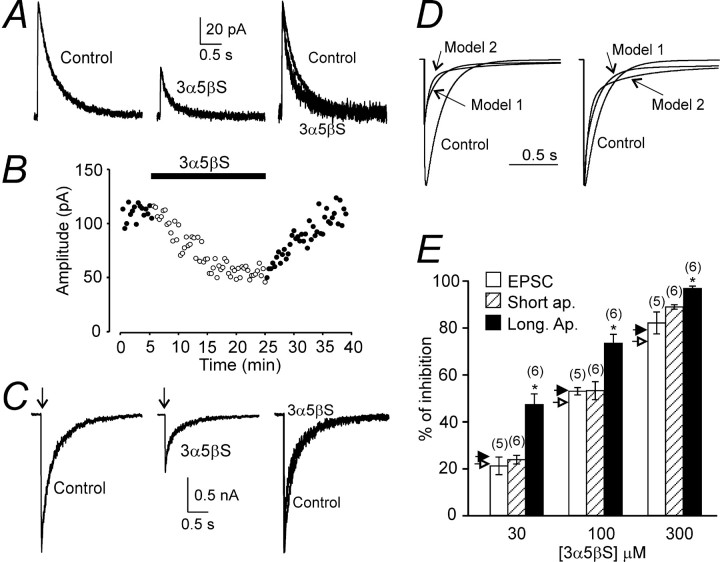

Next, experiments were performed that aimed at characterizing the effects of 3α5βS on the amplitude and deactivation kinetics of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs in lamina II/III pyramidal neurons of the rat cortex. NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs were evoked in neurons voltage clamped at +40 mV by focal electrical stimulation of the adjacent tissue. After an initial period in which control NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs were recorded, the perfusion solution was exchanged for extracellular solution containing 3α5βS for a period sufficient to produce a steady-state effect on the amplitude of the EPSCs (usually 15–25 min). Figure 7A shows a typical example of the effect of 100 μm 3α5βSonthe amplitude and time course of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs. In the presence of 3α5βS, the amplitude of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs slowly decreased and reached ∼50% of the amplitude before the neurosteroid application. The effect was slowly reversible, presumably attributable to a slow diffusion of the neurosteroid from the slice (Fig. 7B). Taking into account the profound inhibitory effect of 3α5βS on NMDA- and glutamate-induced whole-cell responses recorded from both neurons and HEK293 cells, it was surprising that the inhibitory effect of 3α5βS on the amplitude of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs was significantly smaller at all neurosteroid concentrations tested (30–300 μm) (Fig. 7E). The difference in the relative degree of 3α5βS-induced inhibition of steady-state agonist-evoked responses and NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs was more pronounced at low neurosteroid concentrations (Fig. 7E).

Figure 7.

The effect of 3α5βS on NMDA receptor-mediated EPSC.A, Example of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSC (4 consecutive responses were averaged) evoked in a cortical lamina II/III pyramidal neurons voltage clamped at +40 mV before (Control) and 23–25 min after the start of 100μm 3α5βS application. On the right, both responses are displayed filtered at 100 Hz, normalized to the peak amplitude of the control response, and overlaid to show the difference in the deactivation time course. B, Plot of the amplitude of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSC as a function of time of recording. Filled bar indicates duration of 100 μm 3α5βS application (same neuron as in A1). C, Examples of the records obtained from HEK293 cells expressing NR1–1a/NR2B receptors. Control response to the fast application of 1 mm glutamate (Control) and that induced in the presence of 3α5βS (100 μm) are shown. Above, a 6 ms application of glutamate is indicated by an arrow. Filtered at 100 Hz, superimposed and normalized responses with respect to the peak amplitude of the control response are shown on the right. Note the accelerated initial component and decelerated late component of the deactivation of glutamate responses recorded in the presence of 3α5βS. D, Model 1 and model 2 (for values of the rate constants, see diagram of NMDA receptor states in Fig. 8 B, Table 2) were used to simulate the response to 6 ms application of 1 mm glutamate (Control) and that in the presence of 100 μm 3α5βS. On the left, the simulated responses are shown superimposed. On the right, they are shown superimposed and normalized with respect to the peak amplitude of the control response. E, Summary of the effect of 3α5βS (30–300 μm) on the amplitude of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSC and responses induced by short (6 ms) and long (5 s) application of 1 mm glutamate in HEK293 cells expressing NR1–1a/NR2B receptors. Predicted inhibition of responses to 6 ms application of 1 mm glutamate by 30–300 μm 3α5βS using model 1 and model 2 is indicated by open and filled arrowheads, respectively. Error bars represent mean ± SD, and the number of cells is indicated in parentheses. For any neurosteroid concentration, there is a statistically significant difference (*p < 0.001) between inhibition of responses induced by long and short coapplications of glutamate and neurosteroid, as well as long coapplications of glutamate and neurosteroid and NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs.

The decay of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs recorded in the control extracellular solution was best fit by a double-exponential function with mean time constants τ1 = 108 ± 36 ms (A1 = 46 ± 7%) and τ2 = 369 ± 21 ms (n = 9). It has been shown previously that EPSCs in lamina II/III pyramidal neurons are mediated by NMDA receptors composed of NR2A and NR2B subunits with the relative density changing as a function of postnatal age (Flint et al., 1997). This fits well with the results of our experiments showing that NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs in lamina II/III pyramidal neurons at postnatal day 14 were inhibited by 47 ± 4% (n = 4) when recorded in the presence of ifenprodil (10 μm; selective inhibitor of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors) (Williams, 1993). In the presence of 3α5βS (100 or 300 μm), the deactivation of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs had complex kinetics characterized by an accelerated initial and decelerated late component (see overlaid responses in Fig. 7A). Similar effect of the neurosteroid on the deactivation time course of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs was observed in all 10 neurons analyzed.

Several mechanisms were considered that would account for the minor effect of the neurosteroid on the amplitude of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs, e.g., presynaptic action of the neurosteroid, neurosteroid breakdown, and the presence of endogenous compounds interfering with the neurosteroid action. To exclude mechanisms other than postsynaptic ones, an effect of 3α5βS was studied on responses induced by short applications of glutamate in recombinant NR1–1a/NR2B receptors. Control responses to glutamate (1 mm; applied for 6 ms) were compared with those induced in the continuous presence of 3α5βS (Fig. 7C). At 30–300 μm 3α5βS, the degree of inhibition of responses induced by a brief application of glutamate in lifted HEK293 cell-expressing NR1–1a/NR2B receptors was not significantly different from neurosteroid-induced inhibition of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs; however, it was significantly different from a steady-state inhibition of responses to a long application of glutamate (Fig. 7E). These results suggest that a postsynaptic mechanism accounts for the difference in the 3α5βS-induced inhibition of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs and responses to a long application of glutamate.

The deactivation of control responses mediated by NR1–1a/NR2B receptors after a brief application of glutamate was best fit by a double-exponential function with mean time constants τ1 = 212 ± 23 ms (A1 = 41 ± 5%) and τ2 = 860 ± 121 ms (n = 5). As can be seen from the superimposed responses shown in Figure 7C, 3α5βS accelerated the initial component and decelerated the late component of the deactivation. The deactivation had complex kinetics, and, similarly to the deactivation of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs, we failed to fit it by an exponential function.

Model for 3α5βS action at NMDA receptors

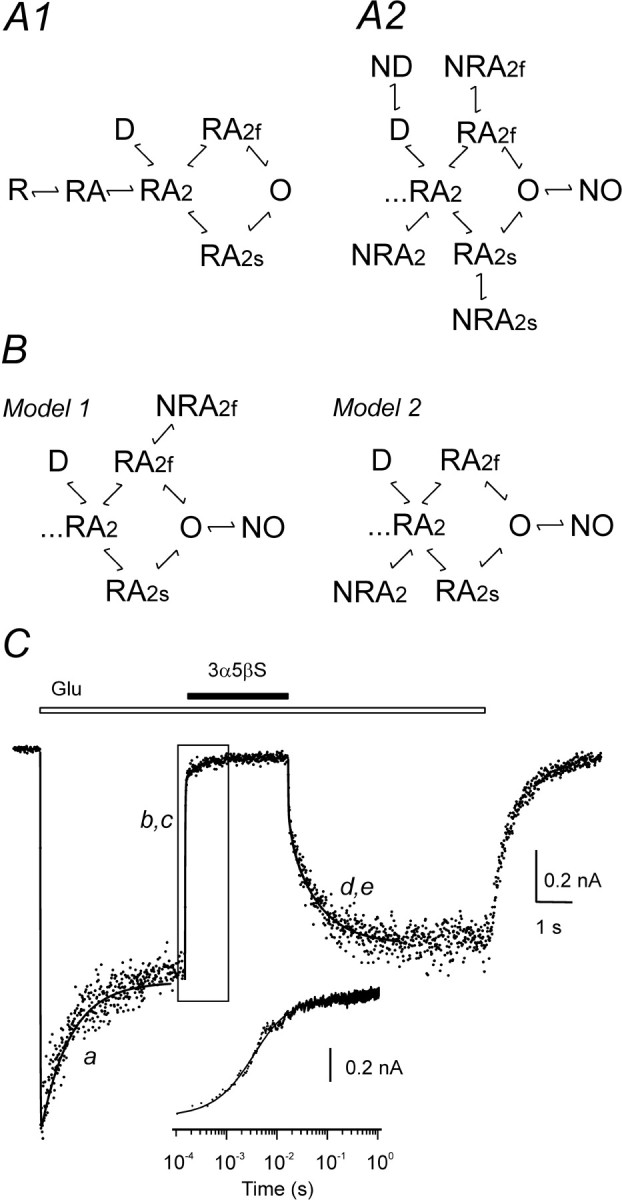

Despite considerable structural and biophysical research, the molecular mechanism of NMDA receptor channel activation is still poorly understood. Several kinetic models were proposed to account for the receptor macroscopic and microscopic properties (Lester and Jahr, 1992; Banke and Traynelis, 2003; Popescu and Auerbach, 2003). Figure 8A1 shows our working model used to infer on the molecular mechanism of 3α5βS action at NMDA receptors. The model is based on a scheme suggested previously by Banke and Traynelis (2003) for the same NMDA receptor subunit combination used in our experiments (NR1–1a/NR2B).

Figure 8.

Model of NMDA receptor inhibition by 3α5βS. A1, Diagram of NMDA receptor states; the model is based on a scheme suggested previously by Banke and Traynelis (2003). A model of gating scheme assumes that, after binding of two molecules of agonist (A), NMDA receptor (R) can reach an active state with the ion channel open (O) via either fast or slow conformational change (RA2f, RA2s). One desensitized state (D) was added, as predicted by the single-exponential time course of current response to prolonged glutamate application. A2, According to the use-dependent action of 3α5βS at NMDA receptors, it is assumed that neurosteroid binds to agonist-induced conformational state(s): RA2, D, RA2f, RA2s, and/or O. B, Onset and offset of 3α5βS-induced inhibition of response to glutamate were fit to model 1 (assuming neurosteroid binding to conformational states RA2f and O) or model 2 (assuming neurosteroid binding to conformational states RA2 and O). C, NR1–1a/NR2B receptor response to 1 mm glutamate, coapplication of glutamate with 300 μm 3α5βS, and neurosteroid washout (duration of 3α5βS and glutamate is indicated by filled and open bar, respectively) is represented by dots. The transient induced by glutamate was fitted to the seven-state kinetic model shown in A1. The following rate constants (k(X, Y) indicates rate constant that determines transition from conformational state X to Y) were fixed: k(R, RA = 19 μm–1s–1; k(RA, RA2) = 9.5 μm–1s–1; k(RA, R) = 29 s–1; k(RA2, RA) = 58 s–1; k(RA2, RA2f) = k(RA2 s, O) = 1557 s–1; k(RA2f, RA2) = k(O, RA2s) = 182 s–1; and k(RA2s, RA2) = k(O, RA2f) = 135 s–1. Only rate constants of receptor desensitization and channel opening were allowed to vary during fitting. Fitted rates were as follows: k(RA2, D) = 4.7 s–1; k(D, RA2) = 0.7 s–1; and k(RA2, RA2s) = k(RA2f, O) = 12.7 s–1. The optimally fitted transient from the kinetic model is superimposed (line a). The transient induced by neurosteroid washout was fit to models shown in B, and the rate of 3α5βS unbinding from conformational states NRA2f and NO (model 1) and NRA2 and NO (model 2) was determined. Fitted rates were as follows: k(NRA2f, RA2f) = 55.3 s–1 and k(NO, O) = 0.75 s–1 (model 1); k(NRA2, RA2) = 0.75 s–1 and k(NO, O) = 9.8 s–1 (model 2). The optimally fitted transients using model 1 and model 2 are shown superimposed (line d, e). With rate constants determined in previous steps, the transient induced by neurosteroid application in the presence of glutamate was fit, and the rate constants of 3α5βS binding to conformational states RA2f and O (model 1) and RA2 and O (model 2) were determined. Fitted rates were as follows: k(RA2f, NRA2f) = 0.29 μm–1 s–1 and k(O, NO) = 0.84 μm–1 s–1 (model 1); k(RA2, NRA2) = 0.86 μm–1 s–1 and k(O,NO) = 1.57 μm–1 s–1 (model 2). The optimally fitted transients are shown superimposed (line b, c). Inset shows boxed region of the response and both fits plotted on a logarithmic timescale. Note that both the onset and offset of the neurosteroid inhibition were equally well fit by both models; therefore, lines b, c and d, e overlap.

Kinetic analysis of responses induced in lifted HEK293 cells by (1) fast application of 1 mm glutamate, (2) coapplication with 300 μm 3α5βS, and (3) recovery of glutamate responses after the neurosteroid washout was performed in three consecutive steps (Fig. 8C). First, the model was fitted to the macroscopic current response induced by 1 mm glutamate (Fig. 8C, trace a), and the desensitization/resensitization rate constants k(RA2, D) (rate constant that determines transition from conformational state RA2 to D), k(D, RA2), and k(RA2, RA2S) = k(RA2F, O) were determined (Table 2). All other rate constants were the same as those set by Banke and Traynelis (2003) and are listed in the Figure 8 legend. Subsequently, concentrations of all conformational states were determined at the time of initiation of neurosteroid application (4 s after the start of glutamate application).

Table 2.

Summary of NMDA receptor model rate constants and those for 3α5βS action

|

Rate constant |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| k(RA2, D) (S-1) | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 4.2 ± 0.7 |

| k(D, RA2) (S-1) | 0.75 ± 0.13 | 0.75 ± 0.13 |

| k(RA2, RA2s) = k(RA2f, O) (S-1) | 11.5 ± 3.3 | 11.5 ± 3.3 |

| k(RA2f, NRA2f) (μm-1S-1) | 0.27 ± 0.08 | |

| k(NRA2f, RA2f) (S-1) | 55 ± 24 | |

| k(O, NO) (μm-1S-1) | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 |

| k(NO, O) (S-1) | 0.81 ± 0.07 | 7.0 ± 2.8 |

| k(RA2, NRA2) (μm-1S-1) | 0.98 ± 0.39 | |

|

k(NRA2, RA2) (S-1) |

|

0.82 ± 0.17 |

The table shows the mean ± SD (from a total of 6 cells) rate constants (k(X,Y) indicates the rate constant that determines transition from conformational state X to Y) obtained from the fitting of the response to 1 mm glutamate, onset and offset of inhibition by 300 μm 3α5βS with models 1 and 2 (see Fig 8B).

In all six cells analyzed, only one desensitized state was sufficient to fit the whole-cell responses induced by a saturating concentration of glutamate. This is predicted by a single-exponential time course of current response to a saturating concentration of glutamate. Attempts to use a model with two desensitized states proposed by Banke and Traynelis (2003) provided inconsistent data. It is possible that the increase in the desensitization of NMDA receptor channels after patch isolation from the cell (Tong and Jahr, 1994) is associated with the appearance of a new desensitized state (Banke and Traynelis, 2003) that is rare or nonexisting for receptors with the relatively intact microenvironment expected to occur in the initial states of whole-cell recording. Estimates of the rate constants k(RA2, RA2S) and k(RA2F, O) (values listed in Table 2) predict a peak Po of 6.3%, which agrees well with our experimental data (see above) and estimates made previously (Chen et al., 1999; Horak et al., 2004).

Figure 8A2 shows an overall scheme combining 15 models that were considered in assessing the molecular mechanism of 3α5βS action at NR1–1a/NR2B receptors. The models assume that the neurosteroid (N) binds to single or multiple agonist-induced conformational state(s) of the NMDA receptor with the ion channel closed (RA2, RA2s, and RA2f), desensitized (D), and ion channel open (O). In the initial stages of the analysis, we considered a model assuming two equivalent and independent binding sites for 3α5βS at the NMDA receptor. This assumption was vaguely supported by the results of our experiments indicating the importance of the NR2 subunit for the 3α5βS inhibitory effect and by the conclusion that functional NMDA receptors assemble as heteromers of two NR1 and two NR2 subunits (Laube et al., 1998); it was further supported by a Hill slope for the 3α5βS inhibition of >1. A tentative 11-state model was, however, too complicated and did not allow a reproducible determination of the neurosteroid binding and unbinding rate constants, in contrast to the one-to-one stoichiometry model that was sufficient to fit the data adequately (see below).

For each of the 15 models (two of them are shown in Fig. 8B), rate constant(s) of neurosteroid unbinding from respective conformational state(s) were set as free parameter(s), and the models were fit to the offset of 3α5βS-induced inhibition of glutamate response (for an example, see Fig. 8C, lines d, e). The sum of the squares of residuals (SSR) determined for each model, and cell response (n = 6) was used to compare the goodness of the fits. In all six cells analyzed, the best fit was obtained using model 2, and therefore SSR obtained through this model was used to determine the relative value of SSR when other models were used (Table 3). Statistical comparison of models (Rao, 1973) indicated that all 10 models that assumed neurosteroid unbinding from combinations of two conformational states provided significantly (p < 0.05) better fit than the models that assumed neurosteroid unbinding from a single conformational state (ND, NO, NRA2s, NRA2f, and NRA2) (Table 3). The conformational state NO stands for agonist-activated NMDA receptor with the neurosteroid bound but with a nonconducting ion channel. Figure 8, B and C, shows an example of such an analysis in which 3α5βS was assumed to dissociate from conformational states NRA2f and NO (model 1) and NRA2 and NO (model 2).

Table 3.

Comparison of kinetic models used to fit the offset of 3α5βS-induced inhibition of glutamate responses

|

|

ND → D |

NO → O |

NRA2s → RA2s |

NRA2f → RA2f |

NRA2 → RA2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ND → D | 5.22 ± 1.83 | ||||

| NO → O | 1.02 ± 0.01 | 1.98 ± 0.58 | |||

| NRA2s → RA2s | 1.02 ± 0.01 | 1.03 ± 0.04 | 1.89 ± 0.50 | ||

| NRA2f → RA2f | 1.01 ± 0.03 | 1.01 ± 0.01 | 1.06 ± 0.06 | 2.67 ± 0.47 | |

| NRA2 → RA2

|

1.02 ± 0.03

|

1.00

|

1.02 ± 0.02

|

1.07 ± 0.08

|

2.69 ± 0.50 |

The values are the mean ± SD (n = 6) of the relative SSR obtained from the fit of 15 different models to the offset of 3α5βS-induced inhibition of glutamate responses. The model assuming neurosteroid (N) unbinding from state NRA2 (NRA2 → RA2) and NO (NO → O) (Fig. 8B, model 2) provided the best fit in all six cells analyzed and therefore was used to determine relative SSR in other models tested. Values in bold indicate combinations of conformational states that were considered to provide a good fit. The models assumed neurosteroid unbinding from one (indicated by intersections of rows and columns with the same transitions) or a combination of two agonist-induced conformational states of the NMDA receptor (indicated by intersections of rows and columns with different transitions). Titles indicate direction of neurosteroid unbinding from respective states.

We next sought to analyze the onset of inhibition of the glutamate response by 300 μm 3α5βS. Models providing a good fit to the off response were used to assess the rate constants of the neurosteroid binding to the respective conformational states of the receptor. For each of the 10 models, rate constants of neurosteroid unbinding from respective conformational states (determined in the previous step) were fixed, rate constants of neurosteroid binding were set as free parameters, and the models were fit to the onset of 3α5βS-induced inhibition of glutamate response (for an example, see Fig. 8C, line b, c). Based on SSR values, the best fit was obtained using model 1 in three of six cells analyzed and using model 2 in the remaining cells. The relative values of SSR indicate that 2 of 10 combinations of the two conformational states to which the neurosteroid can bind and from which it can dissociate [RA2f, O (model 1) and RA2, O (model 2)] provided a good fit (Fig. 8C, Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of kinetic models used to fit the onset of 3α5βS-induced inhibition of glutamate responses

|

|

D → ND |

O → NO |

RA2s → NRA2s |

RA2f → NRA2f |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O → NO | 3.16 ± 1.41 | |||

| RA2s → NRA2s | 15.61 ± 6.54 | 2.27 ± 0.52 | ||

| RA2f → NRA2f | 4.23 ± 1.14 | 1.01 ± 0.02 | 6.36 ± 3.76 | |

| RA2 → NRA2

|

11.91 ± 7.98 |

1.03 ± 0.03

|

6.10 ± 3.40 |

7.70 ± 5.31 |

The values are means ± SD (n = 6) of the relative SSR obtained from the fit of 10 different models to the onset of 3α5βS-induced inhibition of glutamate responses. The model assuming neurosteroid (N) binding to conformational state RA2f (RA2f → NRA2f) and O (O → NO) (Fig. 8B, model 1) provided the best fit in three of six cells analyzed, whereas in the remaining three cells, the responses were best fit by a model assuming neurosteroid binding to conformational state RA2 (RA2 → NRA2) and O (O → NO) (Fig. 8B, model 2). In each cell, the model providing best fit was used to determine relative SSR for other models tested. Values in bold indicate combinations of conformational states that were considered to provide a good fit (models 1 and 2). The models assumed neurosteroid binding to a combination of two agonist-induced conformational states of the NMDA receptor (indicated by the intersections of rows and columns). Titles indicate direction of neurosteroid binding to respective states.

Discussion

Through analysis of whole-cell and single-channel responses induced in native and recombinant receptors, we suggest that 3α5βS is a use-dependent but voltage-independent inhibitor of NMDA receptors.

Comparison of 3α5βS and PS action at NMDA receptors

Despite the structural similarity of 3α5βS and PS, these neurosteroids exert different effects at NMDA receptors. In contrast to the use-dependent inhibitory action of 3α5βS, PS has disuse-dependent potentiating action at NMDA receptors and, in addition, a weak inhibitory effect (Malayev et al., 2002; Horak et al., 2004). The effects of both neurosteroids are dependent on the receptor subunit composition: the inhibitory effect of 3α5βS and PS is more pronounced at receptors containing NR2C/D subunits, and the potentiating effect of PS is more pronounced at receptors containing NR2A/B subunits (Malayev et al., 2002; Horak et al., 2005). Although the neurosteroid-binding sites at the NMDA receptor have not been identified with certainty, the data presented here for 3α5βS and those for PS (Jang et al., 2004; Horak et al., 2005) indicate the importance of the M3–M4 loop of the NR2 subunit that controls the sensitivity to both neurosteroid-induced potentiation and inhibition. The experimental data are compatible with a model that assumes that two separate binding sites for neurosteroids exist at the NMDA receptor: activation of the first type by 3α5βS and PS has an inhibitory effect, whereas activation of the second type by PS has a potentiating effect. The model of neurosteroid action at NMDA receptors is similar to that proposed for 3α5βS and PS action at AMPA receptors, in which evidence for the binding of both neurosteroids to the glutamate-binding core of GluR2 was provided (Spivak et al., 2004).

3α5βS is a use-dependent NMDA receptor inhibitor

Evidence from this study suggests that 3α5βS is a use-dependent inhibitor of NMDA receptor channels. A large number of ions and drugs inhibit NMDA receptor channels by a mechanism that is use- (or agonist-) dependent in nature, which is typical for ion channel blockers (Rogawski, 1993). Pharmacologically, these compounds have been defined as having a “noncompetitive” and/or “uncompetitive” mechanism of action and a voltage-dependent nature of antagonism (MacDonald et al., 1991; Rogawski, 1993). The voltage dependence of blockers arises from binding of the positively charged compound inside the channel pore. Therefore, binding will be affected by the voltage drop across the membrane (Woodhull, 1973). The voltage-independent effect of 3α5βS at NR1–1a/NR2B, as well as native receptors (Park-Chung et al., 1994; Abdrachmanova et al., 2001; Malayev et al., 2002), strongly indicates that the binding site is located outside the potential field of the membrane and also that the site of action is different from those of open channel blockers. Our working hypothesis is that 3α5βS functions as an endogenous compound that binds to agonist-induced state(s) of the NMDA receptor to decrease the efficacy by which the binding of glutamate results in conformational changes associated with the channel opening.

Our experiments suggest that 3α5βS binding to the NMDA receptors can occur only in the presence of agonist, i.e., it is use dependent (Fig. 2A1,A2). However, 3α5βS dissociation proceeds at the same rate independently of the receptor activation (Fig. 2B,C1). The binding characteristics are similar to those described for some of the voltage-dependent blockers of NMDA receptor (MacDonald et al., 1987; Huettner and Bean, 1988). The extent of agonist dependency affects the degree to which the blocker is trapped in the channel, so the blockers range from those that are not trapped [e.g., 9-aminoacridine (Benveniste and Mayer, 1995)] to those that are fully trapped [e.g., MK-801 (Huettner and Bean, 1988)]. If we neglect the differences in the voltage dependency, the action of 3α5βS at NMDA receptors is similar to that of 9-aminoacridine, because neither of them are trapped (Benveniste and Mayer, 1995). It has been proposed that the lack of complete trapping is an important factor that accounts for the favorable tolerability of certain channel-blocking NMDA receptor antagonists as drugs in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases (Mealing et al., 2001).

On the basis of kinetic analysis of the 3α5βS-induced inhibition, a model of neurosteroid action at NR1–1a/NR2B receptors was developed (Fig. 8B). Only 2 of 15 models provided a good fit to the experimental data: model 1 with neurosteroid binding at agonist-induced receptor conformational states RA2f and O, and model 2 with neurosteroid binding at states RA2 and O (Fig. 8B1). Rate constants characterizing models 1 and 2 were subsequently used to test for their compatibility with the experimental data (Fig. 2C2, 3B, 7D). Both models faithfully simulated recovery from 3α5βS-induced inhibition in the continuous presence of glutamate and recovery from inhibition after varying durations of neurosteroid washout in the absence of agonist (Fig. 2C1,C2).

Molecular mechanism of agonist trapping during 3α5βS-induced inhibition

The existence of an after-response induced by control extracellular solution after a coapplication of neurosteroid and glutamate (Fig. 3A) indicates the existence of neurosteroid-induced conformational state(s) of the NMDA receptor channel complex that impede dissociation of the glutamate from the neurosteroid-modulated NMDA receptor. After the relief of neurosteroid inhibition, NMDA receptors with trapped glutamate undergo conformational transitions, which include a conformational state with open NMDA receptor channel. A similar after-response was induced after relief of inhibition of NMDA and nicotinic receptors induced by the open channel blocker 9-aminoacridine and local anesthetics, respectively. A scheme has been proposed in which the blocker prevents the escape of agonist from its binding site (Neher, 1983; Benveniste and Mayer, 1995). This may indicate that the model for open channel blockers and the neurosteroid-induced inhibition of NMDA receptors may be similar. Although the ion channel block is induced by the binding of positively charged compound in the ion channel, the results of our experiments indicate that the neurosteroid-induced inhibition is induced by 3α5βS binding outside the membrane field, likely in the M3–M4 loop of the NR2 subunit. On the basis of the results of previous studies that identified a segment within the M3–M4 loop that was important for glutamate binding (Laube et al., 1997; Anson et al., 1998; Jang et al., 2004), our working model assumes that glutamate binding induces conformational changes in the M3–M4 loop, which in turn leads to the formation of a neurosteroid-specific binding site. 3α5βS binding to this site arrests the receptor in a state with the trapped agonist. This hypothesis is in agreement with our experimental results; however, structural data are required to determine the consequences of neurosteroid binding at the NMDA receptor.

Rate constants characterizing models 1 and 2 were used to test for their compatibility with the proposed mechanism of agonist trapping during 3α5βS-induced inhibition. Both models simulated well the after-response after 3α5βS-induced inhibition in the continuous presence of glutamate (Fig. 3B). Comparison of models 1 and 2 with that proposed for open channel blockers indicates that models of neurosteroid action at NMDA receptors and voltage-dependent ion channel blockers incorporate the same scheme: drug interaction with activated receptor (with ion channel open) and a linear transition to conformational state with the inhibitor bound to a nonconducting conformational state (O ↔ NO) (Neher, 1983; Benveniste and Mayer, 1995). Although an open ion channel is an absolute requirement for the blocker to associate with the receptor, our models of neurosteroid action at NMDA receptors indicate that 3α5βS can bind to NMDA receptor with the ion channel open or closed (state RA2f, model 1; RA2, model 2).

Synaptic transmission

Our results indicate that the difference in the degree of 3α5βS-induced inhibition of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs and responses to a long application of glutamate rely on the molecular mechanism of the neurosteroid postsynaptic action. This is presumably attributable to its use-dependent effect, which predicts that the neurosteroid binding is conditioned by preceding agonist binding and further because of its slow binding kinetics. To affect the amplitude of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSC, the neurosteroid must bind to the receptor during a brief window limited by the rise time of the EPSC (∼15 ms). Both model 1 and model 2 predict that the fraction of receptors affected by neurosteroid binding to synaptically activated NMDA receptors will be smaller than the fraction of receptors affected by neurosteroid binding to tonically activated receptors. At 30 μm 3α5βS, the amplitude of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs is reduced approximately twofold less than the amplitude of responses induced by prolonged application of 1 mm glutamate. Because binding of the neurosteroid to NMDA receptors is a second-order reaction, the relative difference between the degree of 3α5βS-induced inhibition of responses to prolonged application of NMDA receptor agonist and NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs decreases with increasing neurosteroid concentration (Fig. 7E). Surprisingly, no effect of 3α5βS on the amplitude and time course of NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs was observed in rat motoneurons (Abdrachmanova et al., 2001). Several possibilities may account for this, including very fast activation and deactivation kinetics of NMDA receptors in these cells (Abdrachmanova et al., 2000).

During pathological conditions, extracellular levels of glutamate are likely to be tonically elevated. Prolonged activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors can lead to the specific cell death referred to as excitotoxicity, which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several CNS diseases in humans (Danysz et al., 2000; Sattler and Tymianski, 2001). Our results show the use-dependent inhibitory effect of 3α5βS, which is more expressed on receptors “tonically” activated than on receptors “phasically” activated during synaptic transmission. This may have significant implications for the design of therapeutic agents with potential clinical use (Zorumski et al., 2000; Kemp and McKernan, 2002).

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic Grant 309/04/1537, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic Research Project AV0Z50110509, and Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports of the Czech Republic Grants 1M0002375201 and LC554. The work of H.C. was supported by Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic Research Project Z4 005 905. We thank Dr. R. Pohl for measurements of nuclear magnetic resonance spectra, H. Holasova for elemental analyses, and E. Stastna and M. Kuntosova for excellent technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Ladislav Vyklický Jr, Institute of Physiology ASCR, Videnska 1083,142 20 Prague 4, Czech Republic. E-mail: vyklicky@biomed.cas.cz.

DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1407-05.2005

Copyright © 2005 Society for Neuroscience 0270-6474/05/258439-12$15.00/0

References

- Abdrachmanova G, Teisinger J, Vlachova V, Vyklicky L (2000) Molecular and functional properties of synaptically activated NMDA receptors in neonatal motoneurons in rat spinal cord slices. Eur J Neurosci 12: 955–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdrachmanova G, Chodounska H, Vyklicky Jr L (2001) Effects of steroids on NMDA receptors and excitatory synaptic transmission in neonatal motoneurons in rat spinal cord slices. Eur J Neurosci 14: 495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anson LC, Chen PE, Wyllie DJ, Colquhoun D, Schoepfer R (1998) Identification of amino acid residues of the NR2A subunit that control glutamate potency in recombinant NR1/NR2A NMDA receptors. J Neurosci 18: 581–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnostova LM, Pouzar V, Drasar P (1992) Synthesis of the sulfates derived from 5 alpha-cholestane-3 beta,6 alpha-diol. Steroids 57: 233–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banke TG, Traynelis SF (2003) Activation of NR1/NR2B NMDA receptors. Nat Neurosci 6: 144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste M, Mayer ML (1995) Trapping of glutamate and glycine during open channel block of rat hippocampal neuron NMDA receptors by 9-aminoacridine. J Physiol (Lond) 483: 367–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Collingridge GL (1993) A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature 361: 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby MR (1993) Pregnenolone sulfate potentiation of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor channels in hippocampal neurons. Mol Pharmacol 43: 813–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Luo T, Raymond LA (1999) Subtype-dependence of NMDA receptor channel open probability. J Neurosci 19: 6844–6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D, Sakmann B (1985) Fast events in single-channel currents activated by acetylcholine and its analogues at the frog muscle end-plate. J Physiol (Lond) 369: 501–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danysz W, Parsons CG, Mobius H, Stoffler A, Quack G (2000) Neuroprotective and symptomatological action of memantine relevant for Alzheimer's disease—a unified glutamatergic hypothesis on the mechanism of action. Neurotox Res 2: 85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF (1999) The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol Rev 51: 7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doble A (1999) The role of excitotoxicity in neurodegenerative disease: implications for therapy. Pharmacol Ther 81: 163–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint AC, Maisch US, Weishaupt JH, Kriegstein AR, Monyer H (1997) NR2A subunit expression shortens NMDA receptor synaptic currents in developing neocortex. J Neurosci 17: 2469–2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ (1981) Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Arch 391: 85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollmann M, Boulter J, Maron C, Beasley L, Sullivan J, Pecht G, Heinemann S (1993) Zinc potentiates agonist-induced currents at certain splice variants of the NMDA receptor. Neuron 10: 943–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak M, Vlcek K, Petrovic M, Chodounska H, Vyklicky Jr L (2004) Molecular mechanism of pregnenolone sulfate action at NR1/NR2B receptors. J Neurosci 24: 10318–10325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak M, Vlcek K, Chodounska H, Vyklicky Jr L (2005) Subtype-dependence of NMDA receptor modulation by pregnenolone sulfate. Neuroscience, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Huettner JE, Bean BP (1988) Block of N-methyl-d-aspartate-activated current by the anticonvulsant MK-801: selective binding to open channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85: 1307–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T, Moriyoshi K, Sugihara H, Sakurada K, Kadotani H, Yokoi M, Akazawa C, Shigemoto R, Mizuno N, Masu M, Nakanishi S (1993) Molecular characterization of the family of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunits. J Biol Chem 268: 2836–2843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahr CE (1992) High probability opening of NMDA receptor channels by l-glutamate. Science 255: 470–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang MK, Mierke DF, Russek SJ, Farb DH (2004) A steroid modulatory domain on NR2B controls N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor proton sensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 8198–8203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawato S, Yamada M, Kimoto T (2003) Brain neurosteroids are 4th generation neuromessengers in the brain: cell biophysical analysis of steroid signal transduction. Adv Biophys 37: 1–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp JA, McKernan RM (2002) NMDA receptor pathways as drug targets. Nat Neurosci [Suppl] 5: 1039–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupp JJ, Vissel B, Heinemann SF, Westbrook GL (1998) N-terminal domains in the NR2 subunit control desensitization of NMDA receptors. Neuron 20: 317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuryatov A, Laube B, Betz H, Kuhse J (1994) Mutational analysis of the glycine-binding site of the NMDA receptor: structural similarity with bacterial amino acid-binding proteins. Neuron 12: 1291–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapchak PA (2004) The neuroactive steroid 3-alpha-ol-5-beta-pregnan-20-one hemisuccinate, a selective NMDA receptor antagonist improves behavioral performance following spinal cord ischemia. Brain Res 997: 152–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laube B, Hirai H, Sturgess M, Betz H, Kuhse J (1997) Molecular determinants of agonist discrimination by NMDA receptor subunits: analysis of the glutamate binding site on the NR2B subunit. Neuron 18: 493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laube B, Kuhse J, Betz H (1998) Evidence for a tetrameric structure of recombinant NMDA receptors. J Neurosci 18: 2954–2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurie DJ, Seeburg PH (1994) Ligand affinities at recombinant N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors depend on subunit composition. Eur J Pharmacol 268: 335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester RA, Jahr CE (1992) NMDA channel behavior depends on agonist affinity. J Neurosci 12: 635–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Wong TP, Pozza MF, Lingenhoehl K, Wang Y, Sheng M, Auberson YP, Wang YT (2004) Role of NMDA receptor subtypes in governing the direction of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Science 304: 1021–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald JF, Miljkovic Z, Pennefather P (1987) Use-dependent block of excitatory amino acid currents in cultured neurons by ketamine. J Neurophysiol 58: 251–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald JF, Bartlett MC, Mody I, Pahapill P, Reynolds JN, Salter MW, Schneiderman JH, Pennefather PS (1991) Actions of ketamine, phencyclidine and MK-801 on NMDA receptor currents in cultured mouse hippocampal neurones. J Physiol (Lond) 432: 483–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malayev A, Gibbs TT, Farb DH (2002) Inhibition of the NMDA response by pregnenolone sulphate reveals subtype selective modulation of NMDA receptors by sulphated steroids. Br J Pharmacol 135: 901–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML, Vyklicky Jr L, Westbrook GL (1989) Modulation of excitatory amino acid receptors by group IIB metal cations in cultured mouse hippocampal neurones. J Physiol (Lond) 415: 329–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mealing GA, Lanthorn TH, Small DL, Murray RJ, Mattes KC, Comas TM, Morley P (2001) Structural modifications to an N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist result in large differences in trapping block. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 297: 906–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellon SH, Griffin LD (2002) Synthesis, regulation, and function of neurosteroids. Endocr Res 28: 463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes P (1993) GEPASI: a software package for modelling the dynamics, steady states and control of biochemical and other systems. Comput Appl Biosci 9: 563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes P (1997) Biochemistry by numbers: simulation of biochemical pathways with Gepasi 3. Trends Biochem Sci 22: 361–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes P, Kell D (1998) Non-linear optimization of biochemical pathways: applications to metabolic engineering and parameter estimation. Bioinformatics 14: 869–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monyer H, Sprengel R, Schoepfer R, Herb A, Higuchi M, Lomeli H, Burnashev N, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH (1992) Heteromeric NMDA receptors: molecular and functional distinction of subtypes. Science 256: 1217–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monyer H, Burnashev N, Laurie DJ, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH (1994) Developmental and regional expression in the rat brain and functional properties of four NMDA receptors. Neuron 12: 529–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E (1983) The charge carried by single-channel currents of rat cultured muscle cells in the presence of local anaesthetics. J Physiol (Lond) 339: 663–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park-Chung M, Wu FS, Farb DH (1994) 3 alpha-Hydroxy-5 beta-pregnan-20-one sulfate: a negative modulator of the NMDA-induced current in cultured neurons. Mol Pharmacol 46: 146–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul SM, Purdy RH (1992) Neuroactive steroids. FASEB J 6: 2311–2322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popescu G, Auerbach A (2003) Modal gating of NMDA receptors and the shape of their synaptic response. Nat Neurosci 6: 476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao CR (1973) Linear statistical infererence and its applications, Chaps 4, 5. New York: Wiley.

- Rogawski MA (1993) Therapeutic potential of excitatory amino acid antagonists: channel blockers and 2,3-benzodiazepines. Trends Pharmacol Sci 14: 325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler R, Tymianski M (2001) Molecular mechanisms of glutamate receptor-mediated excitotoxic neuronal cell death. Mol Neurobiol 24: 107–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler R, Xiong Z, Lu WY, MacDonald JF, Tymianski M (2000) Distinct roles of synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in excitotoxicity. J Neurosci 20: 22–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spivak V, Lin A, Beebe P, Stoll L, Gentile L (2004) Identification of a neurosteroid binding site contained within the GluR2–S1S2 domain. Lipids 39: 811–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GJ, Dodt HU, Sakmann B (1993) Patch-clamp recordings from the soma and dendrites of neurons in brain slices using infrared video microscopy. Pflügers Arch 423: 511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong G, Jahr CE (1994) Regulation of glycine-insensitive desensitization of the NMDA receptor in outside-out patches. J Neurophysiol 72: 754–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissel B, Krupp JJ, Heinemann SF, Westbrook GL (2002) Intracellular domains of NR2 alter calcium-dependent inactivation of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors. Mol Pharmacol 61: 595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]