Abstract

In this study, the anti-inflammatory effects of α-lipoic acid (LA) and decursinol (Dec) hybrid compound LA-Dec were evaluated and compared with its prodrugs, LA and Dec. LA-Dec dose-dependently inhibited lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced nitric oxide (NO) generation in BV2 mouse microglial cells. On the other hand, no or mild inhibitory effect was shown by the Dec and LA, respectively. LA-Dec demonstrated dose-dependent protection from activation-induced cell death in BV2 cells. LA-Dec, but not LA or Dec individually, inhibited LPS-induced increased expressions of induced NO synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) proteins in a dose-dependent manner in both BV2 and mouse macrophage, RAW264.7 cells. Furthermore, LA-Dec inhibited LPS-induced expressions of iNOS, COX-2, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interleukin-1β mRNA in BV2 cells, whereas the same concentration of LA or Dec was ineffective. Signaling studies demonstrated that LA-Dec inhibited LPS-activated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 and protein kinase B activation, but not nuclear factor-kappa B or mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. The data implicate LA-Dec hybrid compound as a potential therapeutic agent for inflammatory diseases of the peripheral and central nervous systems.

Keywords: Decursinol, Hybrid molecule, iNOS, Lipoic acid, Lipopolysaccharide

INTRODUCTION

Microglia are brain macrophages that function as primary inflammatory cells of the central nervous system (CNS). Over-activation or sustained activation of microglia are often associated with the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases through the increased neuronal cell death (1). An increased production of nitric oxide (NO) is proposed to be a key mediator for neuronal death induced by microglial activation. Out of the three different isoforms of NO synthase (NOS)-which are endothelial, neuronal, and inducible NOS (iNOS)-the gene encoding iNOS is increased in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or pro-inflammatory cytokines (2, 3).

Alpha-lipoic acid (LA) is a natural antioxidant found in plant and animals (4). It displays anti-inflammatory and regulatory effects on various metabolic diseases, such as diabetes (5, 6). Although LA exerts health benefits, it is not readily bioavailable because of its low solubility, low gastric absorption, and high metabolic rate in the liver (7). Hybrid drugs possess improved efficacy and bioavailability compared to a two-drug cocktail. Hybridization has the potential to synergize, amplify or modify the effects of individual drug components (8).

In this study, we investigated the anti-inflammatory effects and toxicity of a hybrid drug composed of LA and decursinol (Dec). We then compared these effects with those produced by LA and Dec, individually. Dec is a naturally present coumarin derivative with diverse pharmacological activities in cognitive dysfunction and neurotoxicity (9–11). LA-Dec hybrid molecule protects neurons from ischemic damage in the hippocampus by inhibiting glial activation (12). This study further investigated the anti-inflammatory effects of LA-Dec hybrid in the LPS-induced expression of iNOS/NO at the cellular level and identified the relevant signaling pathways. The findings implicate LA-Dec as a potentially useful therapeutic compound for inflammation in the peripheral and central nervous systems.

RESULTS

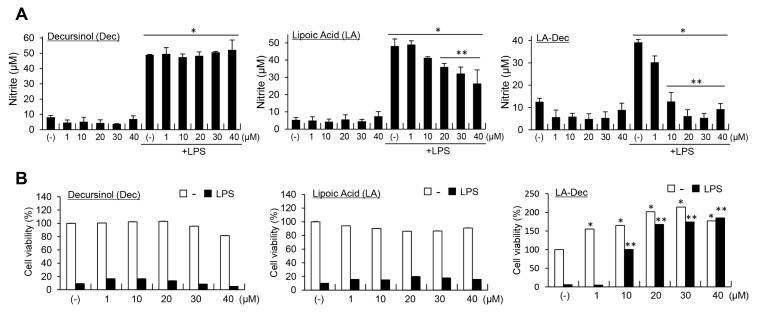

The effects of LA, Dec, and LA-Dec on LPS-induced NO generation in BV2 cells

LA-Dec hybrid compound can protect pyramidal neurons from ischemic injury and reduce inflammation in the brain following the injury (12). To further examine the anti-inflammatory effects of LA-Dec in the cell system, we compared the effects of LA, Dec and LA-Dec hybrid compound on a LPS-induced NO generation and LPS-induced cytotoxicity in BV2 cells. BV2 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of LA, Dec or LA-Dec for 2 hours prior to the 24-hour stimulation with LPS (100 ng/ml). LPS-induced nitrite production was suppressed by LA-Dec in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). LA significantly, but much less effectively, inhibited the LPS-induced nitrite production. LA-Dec (30 μM) suppressed the LPS-induced NO production in RAW264.7 cells (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Examination of LPS-induced nitrite production and cytotoxicity by decursinol (Dec), lipoic acid (LA) and LA-Dec hybrid in BV2 cells. BV2 cells were pre-treated with the indicated concentrations of LA, Dec, or LA-Dec for 2 hours and stimulated with 0.1 μg/ml LPS. Nitrite levels in the culture medium were measured at 24 hours (A). Cell viability was determined by using the MTT assay, and the results are expressed as percentages compared to the untreated control (B). *Represents significant differences from untreated control; **represents significant differences from the LPS-treated samples.

The examination of the cytotoxic effects of the LA, Dec and LA-Dec in the presence and absence of LPS in BV2 cells revealed that LA and Dec did not significantly affect cell viability or proliferation. On the other hand, LA-Dec dose-dependently increased the proliferation of the BV2 cells (Fig. 1B). LA-Dec, but not LA or Dec, strongly and dose-dependently inhibited the activation-induced cell death of BV2 cells in response to LPS.

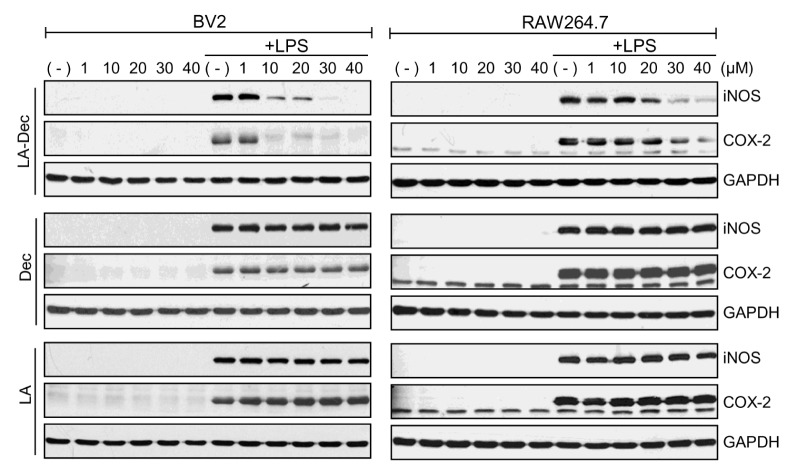

Effects of LA, Dec, and LA-Dec on LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 protein expression in BV2 cells

The effects of LA-Dec, LA, and Dec on LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 expression were assessed. BV2 (Fig. 2, left panels) or RAW264.7 (Fig. 2, right panels) cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of LA-Dec, LA and Dec for 2 hours prior to stimulation with LPS (100 ng/ml). Stimulation of BV2 and RAW264.7 cells with LPS induced the expression of iNOS and COX-2 proteins at 24 hours. LA-Dec inhibited the expression of iNOS and COX-2 protein in a dose-dependent manner in BV2 and RAW264.7 cells, while the same doses of LA or Dec were ineffective.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of expression of LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 proteins by LA-Dec. (A) BV2 (left panel) or RAW264.7 (right panel) cells were pre-treated with the indicated concentrations of Dec, LA or LA-Dec for 2 hours and then treated with 0.1 μg/ml LPS for 24 hours. iNOS, COX-2, and GAPDH protein levels were measured by Western blotting. The blots are representative of three independent experiments.

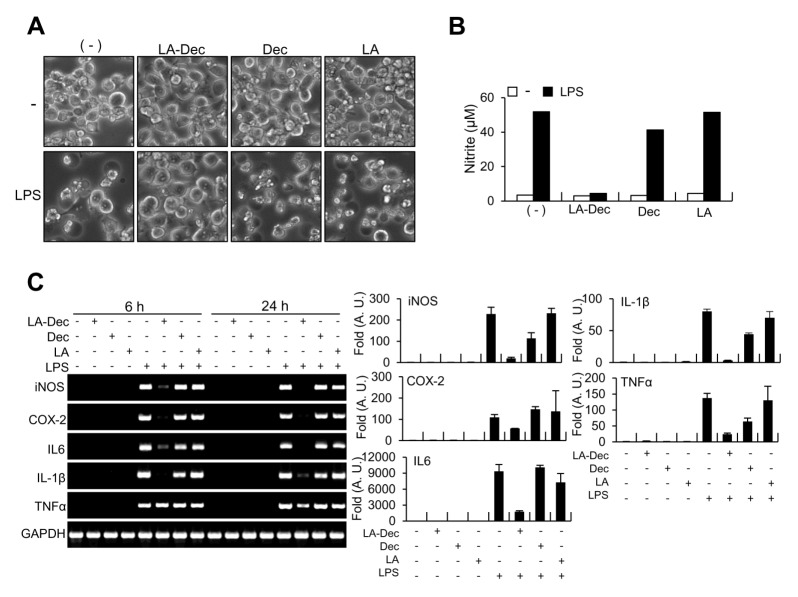

LA-Dec inhibits cell death and mRNA upregulation of proinflammatory molecules in response to LPS in BV2 cells

We examined the effects of LA-Dec on cell morphology and LPS-induced expression of inflammatory genes that have been reported to be induced by the LPS in microglia. BV2 cells were treated with 30 μM LA, Dec or LA-Dec for 2 hours prior to stimulation with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 24 hours. As previously reported (13), the morphological examinations by microscopy indicated that LPS caused activation-induced cell death at 24 hours in BV2 cells (Fig. 3A). LA-Dec significantly protected from activation-induced cell death and it inhibited LPS-induced nitrite production (Fig. 3B). However, the LA or Dec exerted no protective effects. Furthermore, the stimulation of BV2 cells with LPS (100 ng/ml) induced increased mRNA expressions of iNOS, COX-2, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) at 24 hours. Pretreatment with 30 μM LA-Dec inhibited LPS-induced expressions of iNOS, COX-2, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNFα as measured by RT-PCR and quantitative real time PCR (Fig. 3C). However, the same dose of LA or Dec did not inhibit the mRNA levels of these inflammatory molecules.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of mRNA levels of proinflammatory molecules in response to LPS by LA-Dec. BV2 cells were pre-treated with 30 μM of LA-Dec, LA, or Dec for 2 hours and stimulated with 0.1 μg/ml LPS. The phenotypes of control, LA-Dec, LA or Dec treated cells, with or without LPS, were observed by using phase-contrast microscopy at 24 hours (A). Nitrite levels in the culture medium were measured at 24 hours (B). Total RNA was prepared at 24 hours and the mRNA levels of iNOS, COX-2, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β were determined by RT-PCR and quantitative real-time PCR. The GAPDH mRNA served as a control (C). *represents significantly decreased from the LPS-treated samples. Cell images and RT-PCR results are representative of three independent experiments.

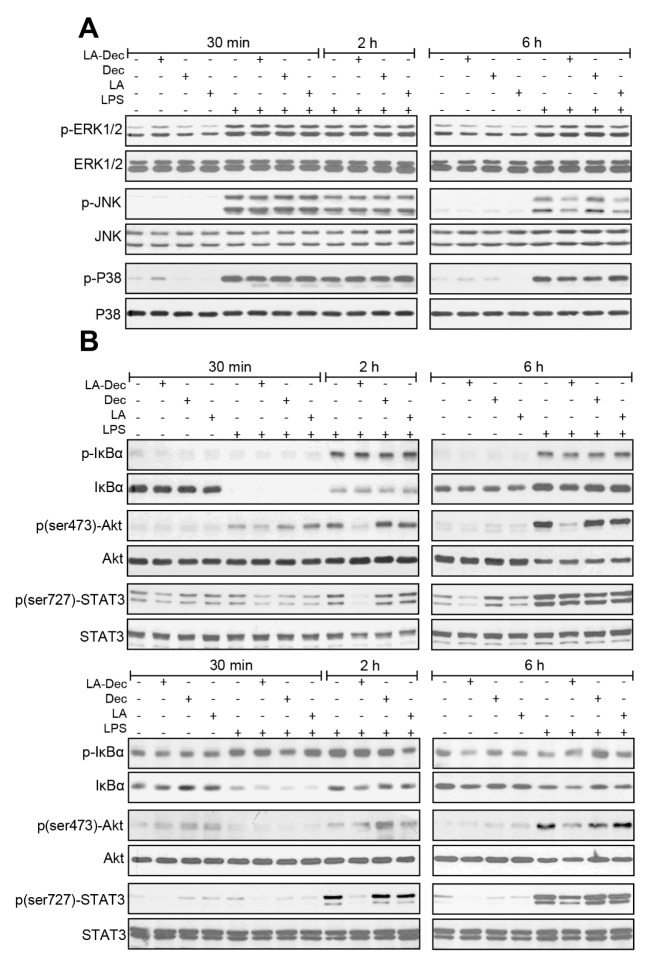

LA-Dec suppresses LPS-induced STAT3 and Akt phosphorylation

We then examined the effects of LA-Dec on the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), protein kinase B (Akt), nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), the major signaling proteins involved in the regulation of the expression of inflammatory mediators. LA-Dec, LA and Dec did not influence LPS-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2, p38, JNK, or IκBα at 30 minutes, 2 hours and 6 hours in the BV2 cells (Fig. 4A). However, LA-Dec significantly inhibited Akt phosphorylation (Ser473) at 2 and 6 hours LPS treatment in BV2 (Fig. 4B, upper panels) and at 6 hours in the RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 4B, lower panels). Furthermore, LA-Dec inhibited LPS-induced phosphorylation of STAT3 (Ser727) at 2 hours in BV2 cells and at 2 and 6 hours in RAW264.7 cells. The same dose of LA or Dec did not inhibit the LPS-induced Akt or STAT3 phosphorylation in BV2 and RAW264.7 cells.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of LPS-induced activation of Akt and STAT3 phosphorylation by LA-Dec. (A) BV2 cells were pre-treated with 30 μM of LA-Dec, LA, or Dec for 2 hours and stimulated with 0.1 μg/ml LPS. Total cell lysates were prepared at 30 minutes, 2 hours, or 6 hours, and the levels of unphosphorylated- and phosphorylated-ERK1/2, -p38, -JNK, -Akt, and -STAT3 were measured by Western blotting. (B) BV2 (upper panels) or RAW264.7 cells (lower panels) were pre-treated with 30 μM of LA-Dec, LA, or Dec for 2 hours and stimulated with 0.1 μg/ml LPS. Total cell lysates were prepared at 30 minutes, 2 hours or 6 hours. The levels of unphosphorylated- and phosphorylated-IκBα, Akt and STAT3 were examined by Western blotting by using specific antibodies. The blots are representative of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies in stroke mouse models have shown that LA-Dec protects against brain ischemic damages potentially by inhibiting brain inflammation. However, the anti-inflammatory activity of LA-Dec at the cellular level is unknown. In this study, we investigated the anti-inflammatory effects of LA-Dec hybrid compound and compared with its lead compounds, LA and Dec, in BV2 microglia and RAW264.7 macrophage cells. We have previously reported that acetylated LA hybridized to dopamine exhibits a strong anti-inflammatory effect in response to LPS in both BV2 and RAW264.7 cells (14). However, cytotoxic effects were observed when BV2 and RAW264.7 cells were incubated with concentrations of the LA-dopamine hybrid exceeding 40 μM, particularly with longer incubation (> 48 hours). The findings indicated that an LA hybrid compound with minimum cytotoxicity could have better therapeutic benefits in terms of anti-inflammatory activity. Presently, LA-Dec hybrid displayed no cytotoxic effect at 24 and 48 hours up to a concentration of 100 μM. Instead, it promoted BV2 cell proliferation at 1, 10, 20, and 30 μM in the presence or absence of LPS. It has been previously shown that LA promotes neuroproliferation through its antioxidant activity (15). Therefore, LA-Dec potentially increased BV2 cell proliferation through its antioxidant activity. Although the underlying mechanism by which LA-Dec increases microglia proliferation remains unclear, LA-Dec hybrid may protect from ischemia-induced neuronal injury through its anti-inflammatory effects and the increased proliferation of glial cells.

MAPKs and NF-κB are important regulators of various genes involved in immune and inflammatory responses, including iNOS and COX-2 (16). LPS stimulation induces the phosphorylation of p38 MAPKs, ERK-1/2, and JNK, leading to the activation of NF-κB in macrophages and microglia. LA-Dec did not inhibit the activation of MAPKs or IκB in response to LPS. Rather, LA-Dec slightly increased LPS-induced NF-κB activity measured by reporter assay (data not shown), suggesting that the anti-inflammatory effect of LA-Dec is independent of MAPKs or NF-κB. LA-Dec, instead, inhibited LPS-mediated activation of the Akt and STAT3 phosphorylation. The JAK-STAT signal pathway plays myriad and pivotal roles in the immune and inflammatory responses (17). We have previously shown that inhibition of STAT signaling reduces iNOS expression and that the inhibition of NF-κB, in turn, inhibits the activation of STAT3 and completely suppresses iNOS induction in response to LPS in BV2 cells (18). This suggests that that STAT3 is one of the many downstream targets of NF-κB that regulates iNOS transcription. However, our results implied that LA-Dec regulated STAT3 in an NF-κB-independent manner. LA-Dec potentially suppressed STAT3 phosphorylation in the Akt-associated signaling pathway for iNOS induction. A previous study reported that the activation of Akt and STAT3 signaling increases the survival and proliferation of microglia (19), implicating Akt and STAT3 activation in microglia proliferation. Furthermore, inhibition of Akt with LY294002 inhibits STAT3 phosphorylation, suggesting that the Akt pathway is responsible for STAT3 phosphorylation in rat hippocampal neurons (20). In particular, based on previous observation that Akt and STAT3 signalings play critical roles in TLR-linked inflammation (21), we propose that LA-Dec regulates Akt-dependent STAT3 signaling and modulates LPS-induced neuroinflammatory responses. However, the detailed underlying mechanisms of the Akt-STAT3 signaling regulations in response to LPS and/or LA-Dec remain to be elucidated.

In conclusion, LA-Dec can suppress the phosphorylation of STAT-3 and Akt in LPS-stimulated BV2 microglia or RAW264.7 macrophages, which may positively correlate with the downregulation of iNOS and other proinflammatory molecules. Accordingly, LA-Dec may serve as a promising therapeutic compound in the treatment of neurodegenerative or other inflammation-related diseases, either alone or as an adjunct to enhance the efficacy of immuno-regulating molecules.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Except where otherwise noted, all reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Synthesis of LA-Dec

Decursin and decursinol angelate were isolated from Dang Gui. They were both hydrolyzed under a NaOH basic condition to obtain Dec. The Dec-LA was synthesized as previously described (12). In brief, the Dec (500 mg, 2.03 mmol) and LA (Xi’an Union Pharmpro Co., Xi’an, China; 0.86 g, 4.47 mmol) were hybridized in the presence of 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP; 120 mg, 1.02 mmol) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC; 86 mg, 4.47 mmol) in 20 ml CH2Cl2 (450 mg, 51% yield).

Cell cultures

BV2 murine microglial cell line is a suitable model for in vitro studies of activated microglia (13). BV2 microglia and RAW264.7 macrophage cells were maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), streptomycin, and penicillin.

Cell viability

Cell viability was measured by the 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrasolium bromide (MTT) assays as described previously anti-inflammatory effects of a novel compound, MPQP, through the inhibition of IRAK1 signaling pathways in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages (14, 22). In brief, BV2 cells were seeded in each well of 24-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well. After 24 hours, cells were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) and/or LA, Dec, or LA-Dec. MTT solution (50 μl) was added to each well and the plates were incubated in the dark for 4 hours at 37°C. The formazan crystals that formed in the viable cells were dissolved in a solution containing equal volumes of dimethyl sulfoxide and ethanol. Absorbance at 595 nm was read on a microplate reader. The results are expressed as a percentage (%) of the untreated control.

Nitrite measurement

The level of nitrite, as an index of NO production, was measured in the supernatant of BV2 cells by the Griess method (14). Cells were seeded in each well of 24-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well. After 24 hours, cells were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/ml) and/or LA, Dec, or LA-Dec. Nitrite accumulation in the culture medium was measured at various time points by adding equal volumes of Griess reagent (1% sulphanilamide, 0.1% naphthylenediamine 5% phosphoric acid) and samples of medium. The optical density at 550 nm (OD 550) was measured with a microplate reader. Sodium nitrite diluted in culture medium (10–100 μM) was used to generate a standard curve.

RT-PCR and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA from BV2 cells was extracted with TRIzolTM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA samples were reverse-transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript II. PCR was performed using specific mouse primers as described below (Table 1). Gene expression values were compared with the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The PCR reaction mixture (15 μl) contained 1.5 mM magnesium chloride (MgCl2), 250 μM deoxy-nucleoside triphosphate, 1.25 units Taq DNA polymerase, 10 picomoles of primer, and 25 ng DNA templates. The PCR products were electrophoresed in 1% agarose gel in Tris/Borate/EDTA (TBE) buffer. The gels were observed and taken pictures using an ultraviolet imaging apparatus.

Table 1.

Mouse PCR primers used in this study

| Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | |

|---|---|---|

| iNOS | ACTTCCGAGTGTGGAACTCG | TGGCTACTTCCTCCAGGATG |

| COX-2 | GCTGTACAAGCAGTGGCAAA | GTCTGGAGTGGGAGGCACT |

| IL-1β | GGAGAAGCTGT GGCAGCTA | GCTGATGTACCAGTTGGGGA |

| IL-6 | CCGGAGAGGAGACTTCACAG | TGGTCTTGGTCCTTAGCCAC |

| TNF-α | GACCCTCACACTCAGATCAT | TTGAAGAGAACCTGGGAGTA |

| GAPDH | TCATTGACCTCAACTACATGGT | CTAAG CAGTTGGTGGTGCAG |

The expressions of mRNAs were quantitatively determined by measuring incorporation of fluorescent SYBR green into double-stranded DNA (iCycleriQ; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The relative mRNA levels were calculated from the PCR profiles of each sample using the threshold cycle (Ct), corresponding to the cycle at which a statistically significant increase in fluorescence occurred. Ct is considered to be the amount of template present in the starting reaction. To correct for differences in the amount of total cDNA in the initial reaction, the Ct values for an endogenous control (input DNA) were subtracted from those of the corresponding sample. All real-time PCR data presented are the results of two independent DNA preparations and amplifications.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed, as described previously (22). Total cell protein was prepared by lysing the cells in buffer (10 mM Tris, 140 mM NaCl, 1% Triton, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and protease inhibitors; pH 8.0). Prepared protein samples (20–40 μg protein each) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to HybondTM-ECLTM nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). All antibodies used were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), with the exception of antibodies against iNOS (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), COX-2 (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI), GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 (Cell Signaling Technology), phospho- c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (p-JNK) (Invitrogen), JNK (Cell Signaling Technology), p-P38 (Cell Signaling Technology), and α-tubulin (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany). The membrane was incubated overnight with antibodies at 4°C. After washing with TBST (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20; pH 7.6), the membrane was incubated in a buffer containing horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000 dilution in TBST) for 1 hour at room temperature. The protein bands were detected by using an ECL detection reagent (Amersham Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D., error bars) of three independent experiments and analyzed for its statistical significance using an unpaired Student’s t test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by INHA UNIVERSITY Research Grant.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown GC, Bal-Price A. Inflammatory neurodegeneration mediated by nitric oxide, glutamate, and mitochondria. Mol Neurobiol. 2003;27:325–355. doi: 10.1385/MN:27:3:325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korhonen R, Lahti A, Kankaanranta H, Moilanen E. Nitric oxide production and signaling in inflammation. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2005;4:471–479. doi: 10.2174/1568010054526359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacMicking J, Xie QW, Nathan C. Nitric oxide and macrophage function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:323–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Packer L, Witt EH, Tritschler HJ. alpha-Lipoic acid as a biological antioxidant. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;19:227–250. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)00017-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sola S, Mir MQ, Cheema FA, et al. Irbesartan and lipoic acid improve endothelial function and reduce markers of inflammation in the metabolic syndrome: results of the Irbesartan and Lipoic Acid in Endothelial Dysfunction (ISLAND) study. Circulation. 2005;111:343–348. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153272.48711.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Han P, Wu N, et al. Amelioration of lipid abnormalities by alpha-lipoic acid through antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects. Obesity. 2011;19:1647–1653. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bilska A, Wlodek L. Lipoic acid - the drug of the future? Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57:570–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corson TW, Aberle N, Crews CM. Design and applications of bifunctional small molecules: Why two heads are better than one. ACS Chem Biol. 2008;3:677–692. doi: 10.1021/cb8001792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li L, Li W, Jung SW, Lee YW, Kim YH. Protective effects of decursin and decursinol angelate against amyloid beta-protein-induced oxidative stress in the PC12 cell line: the role of Nrf2 and antioxidant enzymes. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2011;75:434–442. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang SY, Lee KY, Park MJ, et al. Decursin from Angelica gigas mitigates amnesia induced by scopolamine in mice. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2003;79:11–18. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7427(02)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang SY, Kim YC. Decursinol and decursin protect primary cultured rat cortical cells from glutamate-induced neurotoxicity. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2007;59:863–870. doi: 10.1211/jpp.59.6.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee TH, Park JH, Kim JD, et al. Protective effects of a novel synthetic alpha-lipoic acid-decursinol hybrid compound in experimentally induced transient cerebral ischemia. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2012;32:1209–1221. doi: 10.1007/s10571-012-9861-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim WK, Hwang SY, Oh ES, Piao HZ, Kim KW, Han IO. TGF-beta1 represses activation and resultant death of microglia via inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity. J Immunol. 2004;172:7015–7023. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.7015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwang JS, An JM, Cho H, Lee SH, Park JH, Han IO. A dopamine-alpha-lipoic acid hybridization compound and its acetylated form inhibit LPS-mediated inflammation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;746:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi KH, Park MS, Kim HS. Alpha-lipoic acid treatment is neurorestorative and promotes functional recovery after stroke in rats. Mol Brain. 2015;8:9. doi: 10.1186/s13041-015-0101-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie QW, Kashiwabara Y, Nathan C. Role of transcription factor NF-kappa B/Rel in induction of nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4705–4708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HY, Park SJ, Joe EH, Jou I. Raft-mediated Src homology 2 domain-containing proteintyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP-2) regulation in microglia. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11872–11878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung EH, Hwang JS, Kwon MY, et al. A tryptamine-paeonol hybridization compound inhibits LPS-mediated inflammation in BV2 cells. Neurochem Int. 2016;100:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suh HS, Kim MO, Lee SC. Inhibition of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor signaling and microglial proliferation by anti-CD45RO: role of Hck tyrosine kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt. J Immunol. 2005;174:2712–2719. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murase S, McKay RD. Neuronal activity-dependent STAT3 localization to nucleus is dependent on Tyr-705 and Ser-727 phosphorylation in rat hippocampal neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;39:557–565. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nam HY, Nam JH, Yoon G, et al. Ibrutinib suppresses LPS-induced neuroinflammatory responses in BV2 microglial cells and wild-type mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15:271. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1308-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim BR, Cho YC, Cho S. Anti-inflammatory effects of a novel compound, MPQP, through the inhibition of IRAK1 signaling pathways in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. BMB Rep. 2018;51:308–313. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2018.51.6.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]