INTRODUCTION

Prescription drug coverage is a significant problem in Canada. Indeed, Canada stands out among developed countries with universal public health care systems through its lack of universal public coverage of prescription drugs (“pharmacare”)1. Additionally, compared with consumers in many other developed countries, Canadians pay significantly more for pharmaceutical medications2,3. Finally, there are significant inequities in access: age, profession, health needs, and province of residence often determine the extent to which a patient qualifies for public drug coverage4. That situation has profound consequences for individuals with life-threatening conditions such as cancer.

Cancer is the main cause of mortality in Canada, contributing to about 30% of all deaths and imposing a significant financial burden on governments and individuals alike5. In 2017, close to 200,000 patients were diagnosed with cancer in Canada and about 80,000 died from their disease5. As a treatment for cancer, chemotherapy is often used alone or in conjunction with radiotherapy or surgery, or both, because it has the advantage of acting systemically, where the latter two methods of treatment act locally6. Chemotherapy drugs are routinely administered through either of two routes: the oral route, which can be done in the comfort of the patient’s home, or the intravenous route, which is administered in a hospital setting by a health care professional7. Oral chemotherapy drugs are regularly prescribed instead of, or in addition to, intravenous chemotherapy for late-stage solid tumors (breast, pancreas, kidney, prostate, colon and rectum, and lung)8, and use of those oral drugs is growing: a 2016 estimate calculated that, of all new oncology medications being developed, close to 60% are orally administered7.

Because of the lack of universal pharmacare and the fragmented public coverage already described, public reimbursement of oral chemotherapy drugs varies significantly across Canada. Here, we expose the interprovincial and intraprovincial inequities in oral chemotherapy drug availability and reimbursement programs across Canada that could be mitigated through a national pharmacare programa.

INEQUITIES

Interprovincial Inequities in Oral and Intravenous Cancer Drug Reimbursements in Canada

In Western Canada (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba) and in Quebec, oral chemotherapy drugs are fully covered. In Ontario and Atlantic Canada (New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador), patients sometimes bear the responsibility for some or all of the costs7. In addition to those interprovincial inequities in the cost of oral chemotherapy drugs, the number of available funded cancer drugs in each province differs. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, after having performed a cost-effectiveness analysis, makes recommendations to the provinces about whether they should reimburse novel cancer drugs9. However, compliance with those recommendations varies substantially between provinces, from 78.8% in Ontario, 78.9% in Alberta, and 81.1% in British Columbia, to just 28% in Prince Edward Island10,11. That disparity in access to novel cancer drugs across Canada adds to the interprovincial inequities.

To reduce the cost of oncology drugs, the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance was founded in 2010 with the purpose of increasing bargaining power by negotiating drug prices collectively for all provinces (with the exception of Quebec)12. Although the Alliance helped to reduce the price of costly drugs, it created significant delays in access to novel oncology medications through delayed approvals12. Even after collective negotiation, an individual provincial drug plan still has the authority to refuse coverage for a given medication12. Additionally, once a cancer drug is approved for public coverage, the terms of access can still show large provincial variability13 in that certain patients might not meet the provincial eligibility requirements for public coverage for the specific cancer drug or that other factors, still unknown, might come into play13. For example, anastrozole, a breast cancer medication publicly covered in British Columbia and Alberta, was funded for 60 patients per 100,000 population in British Columbia and for only 29 per 100,000 population in Alberta13.

Residents in some provinces can therefore face the triple jeopardy of lack of public coverage for oral chemotherapy drugs, lack of access to new cancer drugs that are approved in other provinces (Table I), and lack of access to an approved cancer drug if they don’t meet the specific provincial eligibility requirements for free coverage.

TABLE I.

Overview of interprovincial inequities in public coverage of cancer drugs across Canada

| Province | Full chemotherapy drug reimbursement? | |

|---|---|---|

| Intravenous | Oral | |

| British Columbia | Yes | Yes |

| Alberta | Yes | Yes |

| Saskatchewan | Yes | Yes |

| Manitoba | Yes | Yes |

| Ontario | Yes | No |

| Quebec | Yes | Yes |

| Prince Edward Island | Yes | No |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Yes | No |

| New Brunswick | Yes | No |

| Nova Scotia | Yes | No |

Intraprovincial Inequities in Oral Chemotherapy Drug Reimbursement Policies: The Example of Ontario

Per the stipulations in the Canada Health Act, intravenous cancer drugs administered in hospital are fully covered in all provinces. However, the story is quite different for oral chemotherapy drugs in the provinces that do not cover them by default (Ontario, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador)7. Patients in those provinces can therefore face inequities depending on whether they are prescribed an oral or an intravenous chemotherapy drug.

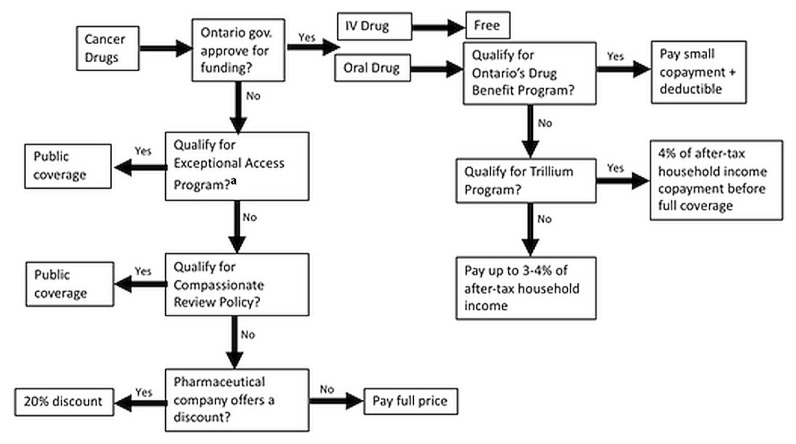

Using Ontario as an example, patients receiving oral chemotherapy drugs have to take multiple steps to receive partial or total funding, as schematically represented in Figure 1. That graphic outlines the stark difference between the experience of those patients and of patients prescribed intravenous chemotherapy drugs who have no out-of-pocket expenses and who are not required to submit complex applications to obtain coverage or reimbursement. In Ontario, residents are publicly covered for their prescription drugs before the age of 25, after the age of 65, if they reside in a long-term care home, and if they are receiving social assistance7. In those instances, oral and intravenous cancer drugs that are on the provincial formulary are both covered through the Ontario Drug Benefit program (although patients are still required to cover a small copayment and a deductible for oral chemotherapy drugs)7.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of Ontario’s public coverage for cancer drugs. aTo qualify for the Exceptional Access Program, patients must first qualify for the Ontario Drug Benefit program or the Trillium Drug Program.

Nevertheless, the program leaves out many Ontarians who have no private insurance for prescription drugs. Indeed, a recent study found that, in 2013, 9588 new cases of cancer were diagnosed in Ontarians who had no private insurance and who did not qualify for the Ontario Drug Benefit program7. Using data from 2016, it has been estimated that 48% of cancer drugs are administered orally, meaning that a significant number of Ontario residents will still incur expenses for their oral chemotherapy drugs7. Those patients can apply to the Trillium Drug Program if the drug is on Ontario’s formulary of approved drugs7. If approved, those patients have to make copayments of approximately 4% of their total household income before their oral chemotherapy drugs are covered7. That sum can still be significant7. Patients who require an oral chemotherapy drug not on the Ontario Drug Benefit formulary can apply for it through the Exceptional Access Program, but only if the patient’s physician demonstrates that no alternative is available7. According to the Physician Alliance for Cancer Care and Treatment, waiting for a decision from the Exceptional Access Program could significantly delay the start of treatment, given that about two thirds of the decisions are delivered within a month and one third take longer7. In rare cases, patients with a cancer that is immediately life-threatening and who require treatment with an unfunded drug can ask their physician to apply for reimbursement through the Compassionate Review Policy, where funding is determined by the Case-by-Case Review Program. The final option is to contact the pharmaceutical company directly, because those companies sometimes offer discounts to patients who can’t afford their medications14. The discounts are usually about 20%, an amount that does not significantly lower the financial burden of oral chemotherapy drugs for certain patients in Ontario, given that treatment with oral oncology drugs usually lasts a year or longer, and costs, on average, $6,000 per month7,14.

All the programs outlined above are independent in the sense that they require their own approvals, and obtaining drug coverage for oral drugs through those plans can be a lengthy process that involves many steps7. Furthermore, patients can ultimately be denied funding, even after pursuing all the steps7. Overall, Ontario’s coverage system for oral chemotherapy drugs appears to be fragmented and inequitable compared with its intravenous drug reimbursement system and compared with provinces such as British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan, where no out-of-pocket costs for oral chemotherapy drugs approved for funding are incurred by patients, regardless of their income and age7.

SUMMARY

It seems almost unthinkable that two patients with cancer in Canada requiring the same drug could have very different experiences. First, between provinces: if the drug has been approved for funding in one province but not the other, one patient will receive it for free, while the other patient might have to remortgage their residence in an effort to afford a drug that can cost anywhere from $1,800 to $132,000 per year7. Second, within provinces: if two patients have the same type of cancer in a province where oral drugs are not covered by default, but one is prescribed an intravenous drug, and the other is prescribed an oral drug, one will incur expenses that the other simply will not have to assume15. Those scenarios outline the inequities that plague public cancer-drug coverage programs across Canada and support the need for a standardized national pharmacare program16.

Key Points.

■ Intravenous cancer drugs are fully covered in all provinces; oral chemotherapy drugs are not.

■ In Western Canada and in Quebec, oral chemotherapy drugs are fully covered; in Ontario and Atlantic Canada, patients sometimes bear responsibility for some or all of the costs.

■ This uneven public coverage of intravenous and oral cancer drugs can lead to inequities within provinces.

■ Inter- and intraprovincial inequities in public coverage of cancer drugs across Canada could be mitigated through a national pharmacare program.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

AQV holds the Canada Research Chair in Policies and Health Inequalities.

Footnotes

Our analysis does not cover the special prescription drug coverage programs offered by the federal government for First Nations and Inuit, and for members of the military, veterans, members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and inmates in federal penitentiaries7. The present analysis excludes those individuals. Furthermore, in Quebec, recommendations for cancer drug coverage are made by the Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux, while in other provinces, recommendations are made by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health8. Quebec is therefore also excluded from the analysis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare that we have none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morgan SG, Boothe K. Universal prescription drug coverage in Canada: long-promised yet undelivered. Healthc Manage Forum. 2016;29:247–54. doi: 10.1177/0840470416658907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin D, Miller AP, Quesnel-Vallée A, Caron NR, Vissandjée B, Marchildon GP. Canada’s universal health-care system: achieving its potential. Lancet. 2018;391:1718–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30181-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (pmprb) Annual Report 2015. Ottawa, ON: pmprb; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allin S, Rudoler D. The Canadian Health Care System. Washington, DC: Commonwealth Fund; 2017. pp. 21–3. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2017. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palumbo MO, Kavan P, Miller WH, Jr, et al. Systemic cancer therapy: achievements and challenges that lie ahead. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:57. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor DW. The Institutionalized Discrimination of Cancer Patients—Not What Tommy Douglas Intended: A Business Case for the Universal Coverage of Oral Cancer Medicines in Ontario and Atlantic Canada. Cambridge, ON: The Cameron Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Given BA, Given CW, Sikorskii A, Vachon E, Banik A. Medication burden of treatment using oral cancer medications. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2017;4:275–82. doi: 10.4103/apjon.apjon_7_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mills F, Poinas AC, Siu E, Wyatt G. Consistency in reimbursement decisions at Canadian hta agencies: inesss versus cdr [abstract PHP108] Value Health. 2014;17:A28. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.03.172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen N, Walker SR, Liberti L, Sehgal C, Salek MS. Evaluating alignment between Canadian common drug review reimbursement recommendations and provincial drug plan listing decisions: an exploratory study. CMAJ Open. 2016;4:E674–8. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20160006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Breast Cancer Network (cbcn) Waiting for Treatment: Timely Equitable Access to Drugs for Metastatic Breast Cancer – 2015. Ottawa, ON: cbcn; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salek SM, Lussier Hoskyn S, Johns J, Allen N, Sehgal C. Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pcpa): timelines analysis and policy implications. Front Pharmacol. 2019;9:1578. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chafe R, Culyer A, Dobrow M, et al. Access to cancer drugs in Canada: looking beyond coverage decisions. Healthc Policy. 2011;6:27–36. doi: 10.12927/hcpol.2011.22177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor P, Priest L, Odutayo A. Personal Health Navigator: A Patient’s Guide to Ontario’s Health Care System. Toronto, ON: Healthy Debate; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pardhan A, Vu K, Gallo-Hershberg D, Forbes L, Gavura S, Kukreti V. Enhancing the Delivery of Take-Home Cancer Therapies in Canada. Toronto, ON: Cancer Care Ontario; 2014. p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan SG, Martin D, Gagnon MA, Mintzes B, Daw JR, Lexchin J. Pharmacare 2020: The Future of Drug Coverage in Canada. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia, Pharmaceutical Policy Research Collaboration; 2015. [Google Scholar]