Watch a video presentation of this article

Abbreviations

- AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

- AFP

alpha‐fetoprotein

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BCLC

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage

- CI

confidence interval

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- FGFR

fibroblast growth factor receptor

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HR

hazard ratio

- N/A

not applicable

- OS

overall survival

- PD1

programmed death receptor‐1

- PDGFR

platelet‐derived growth factor receptor

- PD‐L1

programmed death ligand 1

- SARAH

SorAfenib versus Radioembolisation in Advanced Hepatocellular carcinoma

- SIRT

selective internal radiotherapy

- SIRveNIB

Selective Internal Radiation Therapy Versus Sorafenib in Asia‐Pacific Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- VEGFR

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

- Y90

yttrium‐90

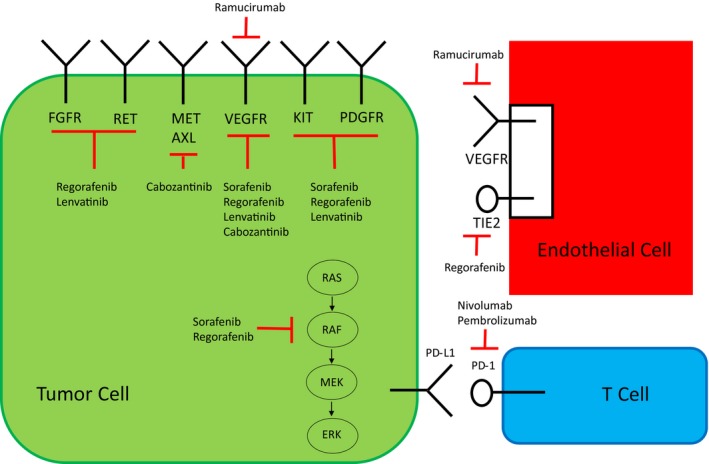

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) Guidelines for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) covered a broad scope of disease management from screening to diagnosis to management of early and advanced stage disease.1 Since its drafting in 2017 and subsequent publication in early 2018, there have been significant advances in the management of advanced HCC. Some of these new data were addressed in the subsequent AASLD Guidance,2 but still not all of the newest data were included. Lenvatinib gained US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and global approval for first‐line use, joining sorafenib in this setting. Results from two phase 3 studies comparing yttrium‐90 (Y90) resin microsphere treatment with sorafenib failed to show superiority in intermediate and advanced HCC, and a third phase 3 study failed to show benefit of Y90 plus sorafenib over sorafenib alone.3 Currently, there are two FDA‐approved therapies for second‐line use after sorafenib, including regorafenib, cabozantinib, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and ramucirumab. Fig. 1 summarizes the mechanisms of action of these new drugs.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of action. This is a depiction of the tumor microenvironment with the tumor, T cells, and blood vessels supplying the area. All four tyrosine kinase inhibitors with positive phase 3 trial results inhibit the VEGF pathway. They all differ slightly with regard to other targets. Red bars indicate inhibition; black arrows indicate activation.

First‐Line Therapy

Sorafenib, an oral multikinase inhibitor with targets including vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1 to 3 (VEGFR1‐3), platelet‐derived growth factor receptor‐β (PDGFR‐β), and Rapidly Accelerated Fibrosarcoma, was the first medication that gained FDA approval for the treatment of advanced HCC. The pivotal phase 3 Sorafenib Hepatocellular Carcinoma Assessment Randomized Protocol (SHARP) trial compared sorafenib 400 mg twice daily with placebo, demonstrating a nearly 3‐month improvement in overall survival (OS; 10.7 months in the sorafenib group and 7.9 months in the placebo group; hazard ratio [HR] 0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.55‐0.87; P < 0.001).4 Sorafenib also extended survival compared with placebo in another phase 3 study of patients with advanced HCC from the Asia‐Pacific region who predominantly had hepatitis B virus infection.5 These two studies established sorafenib as the standard of care and benchmark for Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage (BCLC) C disease and BCLC B patients not eligible for local‐regional therapy.

Lenvatinib is also an oral small‐molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor that inhibits VEGFR1‐3, fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 to 4 (FGFR1‐4), PDGFR‐α, rearranged during transfection (RET) and KIT. The REFLECT study was an open‐label phase 3 study that was powered to demonstrate either superiority or noninferiority to sorafenib. This was a positive study in regard to its noninferiority endpoint with OS of 13.6 months compared with 12.3 months with sorafenib (HR 0.92; 95% CI: 0.79‐1.06). These criteria met the noninferiority threshold with upper limit of CI ≤1.08. Lenvatinib significantly improved progression‐free survival (7.4 versus 3.7 months; HR 0.66), time to progression (8.9 versus 3.7 months; HR 0.63), and overall response rate (ORR) by mRECIST criteria (24.1% versus 9.2%; odds ratio 3.13), all of which supported FDA approval on August 16, 2018.6 Treatment‐emergent adverse events grade ≥3 occurred in 75% of the lenvatinib group and 67% of the sorafenib group, summarized in Table 1. After a decade of failed phase 3 trials versus sorafenib, the REFLECT study was the first positive study.

Table 1.

Toxicities of Newer Agents

| Drug Evaluated | Treatment‐Related Treatment‐Emergent Grade ≥3 Toxicities | Any Grade Treatment‐Related Toxicities ≥25% (≥10% for Pembrolizumab and Nivolumab) |

|---|---|---|

| Lenvatinib | 57% | Hypertension (42%), diarrhea (39%), decreased appetite (34%), decreased weight (31%), fatigue (30%), palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia (27%), proteinuria (25%) |

| Regorafenib | 50% | Palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia (52%), diarrhea (33%), fatigue (29%) |

| Cabozantinib* | 58% | Diarrhea (54%), decreased appetite (48%), palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia (46%), fatigue (45%), nausea (31%), hypertension (29%), vomiting (26%) |

| Ramucirumab | 58.9% | Fatigue (27.4%), peripheral edema (25.4%) |

| Pembrolizumab | 24% | Fatigue (21%), AST increase (13%), pruritis (12%), diarrhea (11%), rash (10%) |

| Nivolumab | 25% | Rash (23%), AST increase (21%), lipase increase (21%), amylase increase (19%), pruritis (19%), alanine aminotransferase increase (15%), diarrhea (10%), decreased appetite (10%) |

Treatment‐emergent toxicities were reported regardless of whether treatment related.

Y90 resin microsphere treatment, also known as selective internal radiotherapy (SIRT) or radioembolization, is a newer precision technology designed to focus high‐dose radiation in the tumor bed. Unlike transarterial embolization, it is not embolic, and phase 2 data have demonstrated its safety and activity.7 Two phase 3 trials compared SIRT with sorafenib in patients with advanced BCLC B and BCLC C disease. Both SorAfenib versus Radioembolisation in Advanced Hepatocellular carcinoma (SARAH) and SIRveNIB (Selective Internal Radiation Therapy Versus Sorafenib in Asia‐Pacific Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma) were negative trials, failing at their primary endpoints of superiority to sorafenib (median OS of 8.8 versus 9.9 months for SARAH; median OS of 8 versus 10.2 months for SIRveNIB) (Table 1).8, 9 Because these were designed to be superiority studies, neither equivalence nor noninferiority can be inferred. Although the Y90 group had fewer treatment adverse events, Y90 should not be recommended as a substitute for patients who are appropriate candidates for systemic therapy with sorafenib. The SORAfenib in combination with local Micro‐therapy guided by gadolinium‐EOB‐DTPA‐enhanced MRI (SORAMIC) phase 3 study evaluated the combination of Y90 and sorafenib versus sorafenib alone for patients with BCLC C HCC. This study failed to demonstrate improved OS in the palliative cohort of the combination treatment group (12.1 months) compared with sorafenib alone (11.5 months; HR 1.01 in per protocol group) as presented at the International Liver Congress in 2018.3 Grade ≥3 adverse events occurred in 72.3% of the SIRT + sorafenib arm and 68.5% of the sorafenib arm.

Challenge of Progression After Sorafenib

Until recently, options for patients who experience progression while receiving sorafenib were limited. Regorafenib, an oral multikinase inhibitor targeting VEGFR, PDGFR, RET, KIT, FGFR1, and TIE‐2, was the first drug approved in this setting. The RESORCE phase 3 trial demonstrated improved median OS compared with placebo (10.6 versus 7.8 months, HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.50‐0.79, P < 0.0001).10 All patients in the trial had tolerated dosages of at least 400 mg/day sorafenib for at least 20 days of the last 28‐day cycle and had documented radiographic progression. Based on these data, regorafenib received FDA approval in 2017.

Cabozantinib, an inhibitor of VEGFR1‐3, MET, and AXL, demonstrated improved median OS in early 2018 in the phase 3 CELESTIAL trial compared with placebo (10.2 versus 8 months, HR 0.76; 95% CI 0.63‐0.92, P < 0.0049) in the second‐ or third‐line setting.11 In addition, in June 2018, at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, ramucirumab, a monoclonal antibody directed toward VEGFR2, was evaluated in patients with alpha‐fetoprotein (AFP) greater than 400 ng/mL who had progressed while receiving sorafenib. Ramucirumab in this patient population significantly extended OS (8.5 months) compared with placebo (7.3 months; HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.53‐0.949, P = 0.0199).12 Significant grade ≥3 treatment‐emergent adverse events were hypertension (12.2%) and hyponatremia (5.6%). Cabozantinib was approved in January 2019 and ramucirumab's approval is expected.

Promise of Immunotherapy

With recent success with durable responses with programmed death receptor‐1 (PD1) checkpoint inhibitors in other tumors, the monoclonal antibodies nivolumab and pembrolizumab have been investigated in the second‐line setting with level II evidence supporting their use. Nivolumab received accelerated FDA approval after 262 patients were treated with nivolumab on a phase 1/2 dose escalation/expansion trial demonstrating ORR 15% to 20% by RECIST 1.1 (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) and median duration of response of about 17 months, considerably higher than the other systemic anti‐angiogenic therapies discussed earlier.13 Similar phase 2 data with pembrolizumab as second‐line treatment were published in July 2018, with FDA granting accelerated approval in this indication as well.14 These drugs featured similar safety data in these patients with cirrhosis and HCC as compared with their use in other solid tumor patient populations. Currently, we are waiting for phase 3 data with these drugs from a study of frontline nivolumab versus sorafenib (Checkmate 459, NCT02576509) and a study of second‐line pembrolizumab versus placebo (KEYNOTE 240, NCT02702401). Both studies have completed accrual, and results are awaited. Recent data with another PD1 antibody, camrelizumab, was recently presented in a randomized phase 2 study from China, evaluating two doses of the antibody, and demonstrated very similar efficacy in the second‐line setting as pembrolizumab and nivolumab with response rates of 13.8% and a disease control rate of 44.7%.15

Conclusion

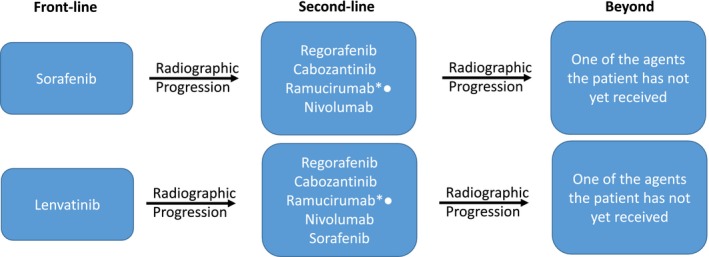

The updated AASLD Guidelines provided a critical literature review and supplied high‐level evidence for its recommendations, which at the time focused on the only systemic agent that had been proved effective in phase 3 studies. Since that time, there has been a remarkable readout of several positive phase 3 studies in both the front‐line and second‐line setting (Table 2). Clearly, systemic agents will be taking on a greater role in the management of HCC, and updating the AASLD guidelines further will help guide clinicians on how to navigate the treatment landscape. Because we now have more active agents, it is imperative that patients be triaged appropriately as they stage migrate from early to advanced before their liver function decompensates. Because we now have multiple agents that prolong survival, clinicians should not wait until patients have clinical progression before offering them the next line of therapy. Currently, several options are available and more to come. New combinations are already being explored, including PD1 inhibitors and tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as lenvatinib and pembrolizumab (NCT03006926), programmed death ligand 1 (PD‐L1) inhibitor and VEGF antibody such as atezolizumab and bevacizumab (IMbrave150, NCT03434379), and PD‐L1 inhibitor with anti‐CTLA‐4 with durvalumab and tremelimumab (NCT03298451). Systemic therapy for HCC is no longer a “one‐trick pony,” and effective sequencing of agents will require an assessment of each individual patient (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Phase 3 Trial Results With Level I Evidence

| Drugs Compared | Trial Name | No. of Patients | Primary Endpoint Median OS | Medication FDA Approved? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sorafenib versus placebo, first line | SHARP | 602 | 10.7 versus 7.9 months (HR 0.69) | Yes |

| Lenvatinib versus sorafenib, first line noninferiority | REFLECT | 954 | 13 versus 12.3 months (HR 0.92; 95% CI: 0.79‐1.06) | Yes |

| Y90 versus sorafenib, first line | SARAH | 459 | 8.8 versus 9.9 months (HR 1.12) | N/A, negative trial |

| Y90 versus sorafenib, first line | SIRveNIB | 360 | 8 versus 10.2 months (HR 1.15) | N/A, negative trial |

| Y90 with sorafenib versus sorafenib alone, first‐line palliative intent | SORAMIC | 424 | 12.1 versus 11.5 months (HR 1.01 in per protocol group) | N/A, negative trial |

| Regorafenib versus placebo, second line | RESORCE | 573 | 10.6 versus 7.8 months (HR 0.63) | Yes |

| Cabozantinib versus placebo, second or third line | CELESTIAL | 707 | 10.2 versus 8 months (HR 0.76) | Yes |

| Ramucirumab versus placebo, second line AFP >400 ng/mL | REACH‐2 | 292 | 8.5 versus 7.3 months (HR 0.71) | Yes |

Figure 2.

Potential options for sequencing systemic agents for patients with BCLC C or BCLC B (not eligible for transarterial chemoembolization). Participation in clinical trials for those who qualify is always a preferred option. Note that all phase 3 second‐line studies to date have been after prior sorafenib, not lenvatinib. The CELESTIAL (cabozantinib) study did take patients who were third line as well (about 25%). Asterisks indicate not approved in HCC as of early 2019; bullets indicate for patients with an AFP concentration greater than 400 ng/mL.

Potential conflict of interest: RSF is a consultant for Astra Zeneca Bayer, Eisai, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly Pfizer, Merck Novartis, and Roche/Genentech.

References

- 1. Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2018;67:358‐380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018;68:723‐750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ricke J, Sangro B, Amthauer H, et al. The impact of combining selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) with Sorafenib on overall survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: the Soramic trial palliative cohort. J Hepatol 2018;68(suppl 1):S102. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008;359:378‐390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia‐Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:25‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first‐line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomised phase 3 non‐inferiority trial. Lancet 2018;391:1163‐1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Salem R, Gordon AC, Mouli S, et al. Y90 radioembolization significantly prolongs time to progression compared with chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2016;151:1155‐1163.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chow PKH, Gandhi M, Tan SB, et al. SIRveNIB: Selective internal radiation therapy versus sorafenib in Asia‐Pacific patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1913‐1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vilgrain V, Pereira H, Assenat E, et al. Efficacy and safety of selective internal radiotherapy with yttrium‐90 resin microspheres compared with sorafenib in locally advanced and inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma (SARAH): An open‐label randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1624‐1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): A randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;389:56‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abou‐Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced and progressing hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018;379:54‐63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhu AX, Kang Y‐K, Yen C‐J, et al. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased alpha‐fetoprotein concentrations (REACH‐2): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:282‐296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. El‐Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): An open‐label, non‐comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2492‐2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE‐224): A non‐randomised, open‐label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:940‐952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Qin SK, Ren ZG, Meng ZQ, et al. A randomized multicentered phase 2 study to evaluate SHR‐1210 (PD‐1 antibody) in subjects with advanced HCC who failed or intolerant to prior systemic treatment [abstract LBA 27]. ESMO 2018 Congress; Munich, Germany; October 21, 2018. [Google Scholar]