Abstract

Objective:

The Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is a collection of item banks of self-reported health. This study assessed the feasibility and construct validity of using PROMIS instruments in vasculitis.

Methods:

Data from a multicenter longitudinal cohort of subjects with systemic vasculitis were used. Instruments from 10 PROMIS item banks were selected with direct involvement of patients. Subjects completed PROMIS instruments using computer adaptive testing (CAT). The Short Form 36 (SF-36) was also administered. Cross-sectional construct validity was assessed by calculating correlations of PROMIS scores with SF-36 measures and physician- and patient global scores for disease activity. Longitudinal construct validity was assessed by correlations of between-visit differences in PROMIS scores with differences in other measures.

Results:

During the study period 973 subjects came for 2,306 study visits and the PROMIS collection was completed at 2,276 (99%) of visits. The median time needed to complete each PROMIS instrument ranged from 40–55 seconds. PROMIS instruments correlated cross-sectionally with individual scales of the SF-36, most strongly with subscales of the SF-36 addressing the same domain as the PROMIS instrument. For example, PROMIS Fatigue correlated with both the Physical Component Score (PCS) (r=−0.65) and with the Mental Component Score (MCS) (r=−0.54). PROMIS Physical Function correlated strongly with PCS (r=0.81) but weakly with MCS (r=0.29). Weaker correlations were observed longitudinally between change in PROMIS scores with change in PCS and MCS

Conclusion:

Collection of data using CAT PROMIS instruments is feasible among patients with vasculitis and has some cross-sectional and longitudinal construct validity.

Keywords: patient reported outcome measures, vasculitis

INTRODUCTION

The clinical course of patients with systemic vasculitis is often characterized by alternating periods of remission and active disease. Outcome measures of Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Autoantibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides and large-vessel vasculitis used in randomized controlled trials are predominately physician-based (1, 2) and do not broadly capture information on the patient experience (3, 4). A standard approach to patient-reported outcomes has not been developed for vasculitis. Measures capturing a more accurate picture of the patient perspective of disease burden in vasculitis would improve disease assessment and the selection of treatments that target disease manifestations of importance to patients (5).

The Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is a system of instruments intended to capture all elements of self-reported health (6, 7). PROMIS utilizes item response theory (IRT) as an underlying statistical framework that enables the use of computer adaptive testing (CAT) to arrive at a precise estimate of a trait under study with minimal patient burden. CAT items are selected from the entire item bank established for the specific instrument domain being studied where additional items are administrated to each participant based on their previous response(s). CAT approaches are designed to efficiently arrive at a measure for each participant with minimal floor and ceiling effects. In addition, to remain compatible with non-adaptive settings, short form (fixed questionnaires) PROMIS instruments in each domain have been developed, typically consisting of four, six, or eight items.

The development of the PROMIS system has led to the application of a number of standardized measures to many disease areas but this has not been done with the vasculitides. The aim of this study was to assess the feasibility and validity of using PROMIS measures to assess the burden of disease in patients with various vasculitides

METHODS

Study oversight

This study was performed by members of the Vasculitis Working Group within the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT)(8) initiative and the investigators of the Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium (VCRC). The work was performed in concordance with the OMERACT guidelines of outcome measure development and validation (9). Members of the Steering Committee for this study were drawn from North-America and Europe and included clinical investigators, methodologists, and patient research partners (PRPs). Main center’s ethics review was obtained from the Office of Regulatory Affairs at the University of Pennsylvania (Approval # 815673). Ethical approval was also obtained from each participating site: Boston University (H-24994), the Cleveland Clinic (05–053), the Mayo Clinic (PR05-004051-12), Mount Sinai Hospital Toronto (07–0189-E), St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton (07–2874), the University of Pittsburgh (PRO 10090549), and the University of Utah (IRB_00042415). All subjects enrolled in the Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium Longitudinal Study (VCRC-LS) have provided written consent for their participation.

Data Source/setting

The VCRC-LS is an ongoing longitudinal observational cohort funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in which participants undergo in-person assessments at either quarterly or annual visits. A total of six forms of vasculitis are studied in the VCRC-LS: Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss, EGPA), giant cell arteritis (GCA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s, GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK), and polyarteritis nodosa (PAN). Data for this study were collected from participants included in the VCRC-LS derived from study visits between December 2013 and May 2016.

Selection of PROMIS measures.

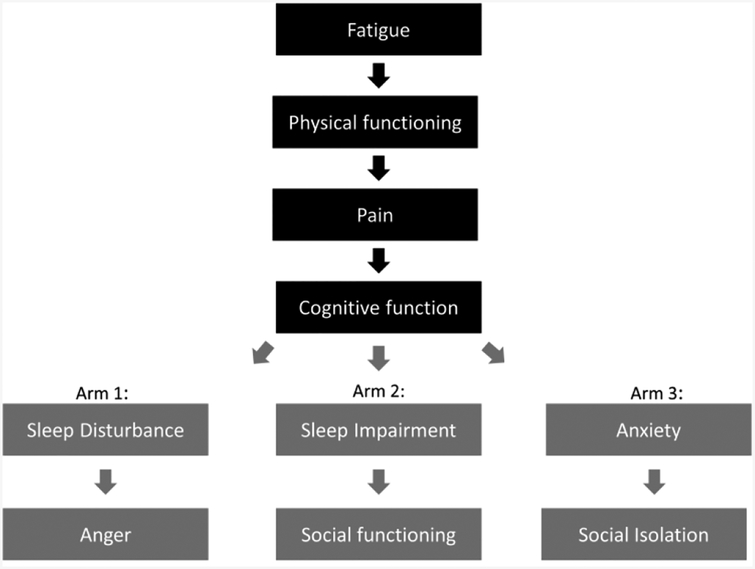

Selection of candidate domains in vasculitis to be represented by a PROMIS item bank was guided by the previous literature, clinical expertise, guidance from the PRPs, a review of qualitative data describing the experiences of patients with vasculitis, and through input from the OMERACT community (4, 10–15). Of the 10 PROMIS item bank instruments selected, four were identified as being of highest relevance to outcome measurement in vasculitis and administered to all subjects in the VCRC-LS: fatigue, physical function, pain interference, and cognitive function. To limit patient burden, the six other item banks felt possible relevant to vasculitis (sleep disturbance, social participation, sleep-related impairment, anger, social isolation, and anxiety) were studied by randomized assignment of two to be consistently administered to each patient so that each of the six additional measures would be completed by one-third of the participants (Figure 1). During the first VCRC study visit after PROMIS had been added to regular assessments, subjects were randomized to one of the three arms by a simple randomization function at the Webserver for this study. Participant remained in the arm they were originally randomized to. All PROMIS instruments are scaled to have a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10 in the US population, where higher scores mean more of the concept being measured.

Figure 1.

Domains and study arms with different PROMIS assessments to which subjects were randomized.

Administration of PROMIS instruments

During scheduled study visits in the VCRC-LS, all participants were asked to complete the PROMIS instruments using an online system presented on a computer or tablet device, in addition to the paper-based patient reported outcome (PRO) instruments already included as part of the study; participants had the option of using one of their fingers or a hand-held stylus to respond to the tablet-based questions. Participants were randomized to complete sets of six PROMIS instruments as outlined above and each patient completed their originally-assigned set of instruments at each follow-up visit. For each item bank a CAT instrument was first administered to completion. To also test the short form version of each PROMIS measure, any remaining items on the four-question short form that had not been chosen by the CAT protocol were also provided to the participants for completion. PROMIS instruments all use 7-day recall period, except the physical functioning instrument where recall periods are not associated with the items. Initially, a pain screening question was employed so only those patients that reported having experienced pain during the prior week were administered the instruments from the pain interference item banks. As this use of a screening question resulted in skewed distribution of pain interference scores, the approach was discontinued during the observation period and the PROMIS pain interference instrument was subsequently administered to all participants. For the CAT instrument the default IRT calibration settings at assessmentcenter.net were used.

Additional Measurement of Health-Related Quality of Life

Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) was assessed with the SF-36 administered by paper (as most instruments in the VCRC) at all study visits. The SF-36 contains 36 items that assess HRQoL in eight health dimensions: physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health (16, 17). Scores for each dimension/subscale range from 0–100 and were transformed to have a mean of 50 and SD of 10 in the reference population, with higher scores indicating better HRQoL. Following standard procedures, two summary scores were derived from combining the eight subscales: the physical component summary (PCS) score and the mental component summary (MCS) score. The PCS and MCS are also norm-based scores standardized to the US general population and transformed to have a mean of 50 and SD of 10 in the reference population.

Assessment of disease activity

Physicians completed a global assessment on a 0–10 integer scale, worded as follows: “Mark to indicate the amount of disease activity (not including longstanding damage) within the previous 28 days.” Patients completed a global assessment on a 0–10 integer scale, worded as follows: “Please mark to indicate how severe your vasculitis disease has been for the past 28 days.” Active disease was defined as a score >0 on the physician global assessment for disease activity.

Statistical analysis

Means with standard deviations and proportions were used to summarize demographic and disease associated factors in this cohort for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Feasibility of PROMIS administration was assessed by calculating the proportion of participants that completed the PROMIS assessments and the time it took to complete the assessments. Cross-sectional construct validity was assessed at the first patient visit during the study period by calculating Spearman correlation coefficients between each PROMIS instruments and subscales of the SF-36, PCS, MCS, and physician and patient global assessments. Longitudinal construct validity was assessed by calculating the between-visit difference in PROMIS measures with differences in the SF-36 measures and global scores to evaluate if the PROMIS measure was more highly correlated with subscales designed to measure the same construct. Data interpreted as supporting construct validity included higher correlations between related measures, convergence (e.g. comparing correlation of bodily pain by SF-36 with pain interference by PROMIS and comparison of vitality by SF-36 with fatigue by PROMIS) and divergence (lower correlations between measures of unrelated constructs). All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software v. 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC)

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics.

During the study period, 1,040 patients with systemic vasculitis came for a VCRC-LS study visit, of whom 973 (94%) started a PROMIS assessment and thus entered this study (Table 1). During the study period the 973 participants attended 2,306 study visits and PROMIS was completed at 2,276 (99%) of the visits. Sixty-two percent of participants were female, the mean age was 57.1 years. Participants with all six forms of vasculitis under study participated in the PROMIS assessments: EGPA (N=123), GCA (N=194), GPA (N=419), MPA (N=68), PAN (N=53), and TAK (N=97). Randomization of the six secondary measures (Figure 1) resulted in study arms that were balanced with respect to age, sex, type of vasculitis, and measures of HRQoL (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants

| Total Cohort N=973 |

Randomization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arm 1 N=311 |

Arm 2 N=331 |

Arm3 N=331 |

||

| Women | 604 (62.1%) | 189 (60.8%) | 197 (59.5%) | 218 (65.9%) |

| Age (years) | 57.1 (16.3) | 56.8 (16.6) | 57.2 (16.7) | 57.4 (15.7) |

| Disease duration (years) | 5.8 (5.5) | 5.9 (5.6) | 6.2 (5.9) | 5.2 (4.9) |

| Patient global | 2.5 (2.3) | 2.4 (2.3) | 2.6 (2.4) | 2.4 (2.3) |

| Physician global | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.3 (1.1) | 0.3 (1.0) |

| SF36 PCS | 42.0 (11.1) | 42.1 (11.0) | 42.0 (10.8) | 42.1 (11.6) |

| SF36 MCS | 48.7 (11.7) | 48.2 (11.1) | 49.5 (11.7) | 48.6 (12.3) |

| PROMIS CAT scores | ||||

| Fatigue | 54.3 (9.5) | 54.4 (9.2) | 54.2 (9.5) | 54.3 (9.8) |

| Physical function | 43.9 (8.9) | 44.0 (9.1) | 43.6 (8.4) | 44.1 (9.3) |

| Pain interference* | 56.5 (8.4) | 57.5 (7.9) | 56.5 (8.5) | 55.6 (8.6) |

| Cognition | 50.1 (8.2) | 49.8 (7.9) | 50.6 (8.0) | 49.9 (8.8) |

| Disease | ||||

| EGPA | 123 (12.7%) | 35 (11.3%) | 42 (12.7%) | 46 (13.9%) |

| GCA | 194 (20.0%) | 53 (17.0%) | 58 (17.5%) | 83 (25.2%) |

| GPA | 419 (43.1%) | 139 (44.7%) | 148 (44.7%) | 132 (40.0%) |

| MPA | 86 (8,9%) | 24(9.6%) | 31 (11.9%) | 21(7.6%) |

| PAN | 53 (5.5%) | 18 (5.8%) | 19 (5.7%) | 16 (4.8%) |

| TAK | 97 (10.0%) | 37 (11.9%) | 31 (9.4%) | 29 (8.8%) |

| Medication | ||||

| glucocorticoid | 457 (47%) | 148 (47.6%) | 146 (44.1%) | 163 (49.2%) |

| azathioprine | 150 (15.4%) | 44 (14.1%) | 50 (15.1%) | 56 (16.9%) |

| cyclophosphamide | 27 (2.8%) | 11 (3.5%) | 6 (1.8%) | 10 (3%) |

| leflunomide | 6 (0.6%) | 3 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (0.9%) |

| methotrexate | 136 (14%) | 45 (14.5%) | 46 (13.9%) | 45 (13.6%) |

| mycophenolate | 44 (4.5%) | 16 (5.1%) | 9 (2.7%) | 19 (5.7%) |

| rituximab | 52 (5.3%) | 25 (8%) | 21 (6.3%) | 6 (1.8%) |

Demographic factors, global scores, measures of quality of life and diagnosis recorded at baseline. Categorical variables are expressed as number (percentage) and continuous variables as mean (standard deviation). PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, SF 36=Short form 36, PCS = physical component summary, MCS = mental component summary, EGPA = eosinophillic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, GCA = giant cell arteritis, GPA = granulomatosis with polyangiitis, MPA = microscopic polyangiitis, PAN = polyarteritis nodosa, TAK = Takayasu’s arteritis.

Until February 2015 only administered to subject admitting to some level of pain. After that, administered to all subjects. The pain interference instrument was administered to 662 subjects at baseline.

Scores on measures of HRQoL and PROMIS measures were overall reduced compared to US population norms (Table 1). At baseline, PROMIS measures were worse (i.e. higher) than the population norms for fatigue, pain interference, and sleep-related impairment, and worse (i.e. lower) for physical function and social isolation. Measures for cognitive abilities, social participation, anger, and anxiety were close to the population norms. No substantial differences in PROMIS scores across disease categories were identified (Table 2).

Table 2.

PROMIS scores from CAT instruments for different forms of vasculitis

| EGPA N=123 |

GCA N=194 |

GPA N=419 |

MPA N=86 |

PAN N=53 |

TAK N=97 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 54.9 (8.8) | 53.7 (9.2) | 54.2 (9.5) | 56.9 (10.0) | 56.9 (10.0) | 54.4 (9.9) |

| Physical functioning | 44.8 (8.0) | 41.4 (7.9) | 45.0 (9.1) | 42.9 (10.7) | 42.9 (10.7) | 44.6 (10.0) |

| Pain interference* | 55.2 (9.3) | 56.3 (7.9) | 56.5 (8.4) | 61.8 (7.6) | 61.8 (7.6) | 57.7 (7.3) |

| Cognitive abilities | 51.0 (9.3) | 50.9 (7.8) | 49.8 (7.6) | 48.1 (9.4) | 48.1 (9.4) | 49.9 (10.1) |

| Sleep disturbance | 50.6 (9.3) | 50.1 (11.0) | 52.2 (10.1) | 53.6 (7.8) | 53.6 (7.8) | 52.3 (10.7) |

| Ability to participate in social activities | 52.4 (9.6) | 49.3 (7.7) | 50.6 (9.2) | 49.0 (10.1) | 49.0 (10.1) | 48.5 (9.9) |

| Sleep-related impairment |

55.0 (10.3) | 50.3 (9.9) | 52.8 (10.7) | 58.1 (9.7) | 58.1 (9.7) | 52.1 (10.8) |

| Anger | 51.0 (9.0) | 47.9 (8.7) | 49.8 (8.3) | 54.0 (7.8) | 54.0 (7.8) | 48.6 (9.3) |

| Social isolation | 44.1 (10.0) | 44.3 (8.6) | 46.1 (9.3) | 50.1 (12.0) | 50.1 (12.0) | 45.1 (10.8) |

| Anxiety | 50.9 (7.9) | 51.0 (7.7) | 52.9 (9.1) | 55.2 (13.2) | 55.2 (13.2) | 54.2 (10.8) |

PROMIS = Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, CAT= computer adaptive testing, EGPA = eosinophillic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, GCA = giant cell arteritis, GPA = granulomatosis with polyangiitis, MPA = microscopic polyangiitis, PAN = polyarteritis nodosa, TAK Takayasu’s arteritis.

Until February 2015 only administered to subject admitting to some level of pain. After that, administered to all subjects. The pain interference instrument was administered to 662 subjects at baseline.

All PROMIS scores are expressed as mean (standard deviation).

Time to complete of PROMIS assessments

The median time to complete each PROMIS domain was 40–55 seconds (Table 3). Age was strongly associated with how long it took subjects to complete the PROMIS assessment. Typically, it took those above the age of 80 years twice as long to complete the assessments compared to those 40 years old and younger. It took participants longer to complete the assessment on the first visit than at subsequent study visits (data not shown).

Table 3:

Time to complete PROMIS instrument

| PROMIS CAT Instruments | Time (seconds) Median (IQR) |

Number of items Mean (sd) |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 50 (IQR: 35–82) | 4.3 (1.2) |

| Physical Function | 50 (IQR: 35–82) | 4.5 (2.7) |

| Pain Interference | 44 (IQR: 31–66) | 5.4 (3.0) |

| Applied Cognitive Abilities | 43 (IQR: 30–65) | 4.9 (2.4) |

| Sleep Disturbance1 | 38 (IQR: 27–56) | 5.1 (2.1) |

| Ability to Participate in Social Activities1 | 42 (IQR: 30–63) | 5.0 (2.3) |

| Sleep-Related Impairment2 | 46 (IQR: 31–74) | 6.0 (3.2) |

| Anger2 | 53 (IQR: 38–78) | 7.2 (2.4) |

| Social Isolation3 | 43 (IQR: 28–65) | 6.4 (3.5) |

| Anxiety3 | 32 (IQR: 23–47) | 5.2 (2.6) |

Times to complete the individual PROMIS assessments are expressed as medians (inter-quartile range, IQR) and number of items (questions) expressed as mean (standard deviation, s.d.) PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, CAT = Computer adaptive testing.

Οnly administered in arm 1

Only administered in arm 2

Only administered in arm 3

Cross-sectional validity of PROMIS instruments at baseline

PROMIS instruments correlated highly, and significantly, with the individual scales of the SF-36. Correlations were of varying magnitude and in the expected direction. PROMIS instruments correlated most strongly with subscales of the SF-36 addressing the same domain (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlations of PROMIS CAT instruments with patient-reported outcomes at Baseline

| PROMIS CAT Instrument |

SF36 Subscales |

SF36 Summary Scores |

Global Assessment Scores |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vital | PF | BP | SF | MH | GH | RE | RP | PCS | MCS | PtGA | PhGA | |

| Fatigue | −0.67* | −0.51* | −0.52* | −0.59* | −0.44* | −0.44* | −0.49* | −0.59* | −0.65* | −0.54* | 0.48* | 0.19* |

| Physical function | 0.50* | 0.73* | 0.53* | 0.47* | 0.30* | 0.40* | 0.40* | 0.63* | 0.81* | 0.29* | −0.43* | −0.11* |

| Pain Interference | −0.52* | −0.51* | −0.62* | −0.52* | −0.40* | −0.36* | −0.43* | −0.54* | −0.71* | −0.43* | 0.44* | 0.07 |

| Applied cognitive abilities | 0.50* | 0.36* | 0.38* | 0.47* | 0.46* | 0.34* | 0.48* | 0.44* | 0.41* | 0.54* | −0.34* | −0.12* |

| Sleep disturbance | −0.38* | −0.24* | −0.28* | −0.46* | −0.41* | −0.26* | −0.39* | −0.28* | −0.31* | −0.53* | 0.32* | 0.17* |

|

Social Participation |

0.49* | 0.62* | 0.50* | 0.63* | 0.43* | 0.34* | 0.48* | 0.59* | 0.72* | 0.48* | −0.51* | −0.10 |

| Sleep-related Impairment | −0.44* | −0.21* | −0.37* | −0.44* | −0.40* | −0.30* | −0.43* | −0.37* | −0.31* | −0.53* | 0.30* | 0.13* |

| Anger | −0.24* | −0.16* | −0.21* | −0.34* | −0.39* | −0.21* | −0.34* | −0.18* | −0.10 | −0.46* | 0.21* | 0.10 |

| Social isolation | −0.45* | −0.33* | −0.32* | −0.48* | −0.56* | −0.31* | −0.48* | −0.37* | −0.30* | −0.58* | 0.23* | 0.07 |

| Anxiety | −0.50* | −0.24* | −0.34* | −0.51* | −0.64* | −0.33* | −0.54* | −0.32* | −0.21* | −0.70* | 0.20* | 0.07 |

| PtGA | −0.40* | −0.40* | −0.47* | −0.42* | −0.25* | −0.36* | −0.31* | −0.45* | −0.54* | −0.31* | 1.00* | 0.29* |

| PhGA | −0.16* | −0.14* | −0.15* | −0.18* | −0.09* | −0.09* | −0.14* | −0.18* | −0.17* | −0.15* | 0.29* | 1.00* |

Spearman correlation coefficients between scores from 10 PROMIS CAT domains, SF36 subscales, SF-36 summary scores and physician- and patient global assessment scores.

PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, CAT = Computer adaptive testing, SF36 = Short form 36, Vital. = Vitality, PF = Physical function, BP = bodily pain, SF = social function, MH = mental health, GH = general health, RE = role emotional, RP = role physical, PCS = physical component summary, MCS = mental component summary, PtGA = Patient global assessment for disease activity, PhGA = Physician global assessment for disease activity.

p<0.05

Some of the PROMIS instruments correlated moderately or strongly with summary scores of the SF-36 in a pattern consistent with the convergence and divergence expected from these measures. For example, PROMIS fatigue correlated both with PCS (r = −0.65) and with MCS (r = −0.54). PROMIS Physical function correlated strongly with PCS (r = 0.81) but weakly with MCS (r = 0.29). PROMIS social participation correlated strongly with PCS (r = 0.72) and moderately with MCS (r = 0.48) and social function subscales. Sleep disturbance and sleep-related impairment correlated best with the SF-36 vitality, social functioning, and MCS scores (Table 4).

Some PROMIS instruments correlated moderately with the patient global assessment for disease activity: fatigue, physical function, pain interference, and social participation, all with r > 0.40. Weak or no correlations were observed between PROMIS instrument and the physician global assessment for disease activity (Table 4). Correlation coefficients using PROMIS scores from short forms were almost identical to the coefficients when the corresponding PROMIS CAT scores were used (Supplemental Table 1).

Longitudinal construct validity of PROMIS instruments

Among the 575 participants that came for more than one visit the change in PROMIS scores correlated with change in the validating constructs, typically in the range r = 0.3–0.5 (Table 5). CAT and short form instruments provided quite similar correlation coefficients (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 5.

Longitudinal correlation of PROMIS CAT instruments with patient-reported outcomes

| PROMIS CAT Instrument |

SF36 Subscales |

SF36 Summary Scores |

Global Assessment Scores |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vital | PF | BP | SF | MH | GH | RE | RP | PCS | MCS | PtGA | PhGA | |

| Fatigue | −0.50* | −0.35* | −0.38* | −0.43* | −0.34* | −0.33* | −0.35* | −0.43* | −0.48* | −0.44* | 0.36* | 0.13* |

| Physical function | 0.40* | 0.56* | 0.40* | 0.36* | 0.22* | 0.28* | 0.28* | 0.48* | 0.65* | 0.23* | −0.32* | −0.10* |

| Pain Interference | −0.34* | −0.36* | −0.48* | −0.37* | −0.27* | −0.24* | −0.25* | −0.33* | −0.57* | −0.27* | 0.34* | 0.16* |

| Applied cognitive abilities | 0.37* | 0.26* | 0.26* | 0.31* | 0.36* | 0.23* | 0.34* | 0.32* | 0.25* | 0.43* | −0.21* | −0.06* |

| Sleep disturbance | −0.20* | −0.22* | −0.18* | −0.30* | −0.14* | −0.10* | −0.14* | −0.14* | −0.18* | −0.24* | 0.17* | 0.08 |

|

Social Participation |

0.29* | 0.25* | 0.25* | 0.32* | 0.15* | 0.16* | 0.27* | 0.30* | 0.36* | 0.24* | −0.27* | −0.08 |

| Sleep-related Impairment | −0.20* | −0.24* | −0.24* | −0.30* | −0.25* | −0.11* | −0.25* | −0.24* | −0.19* | −0.36* | 0.10* | 0.06 |

| Anger | −0.28* | −0.16* | −0.24* | −0.33* | −0.39* | −0.17* | −0.36* | −0.25* | −0.09* | −0.51* | 0.17* | 0.05 |

| Social isolation | −0.30* | −0.13* | −0.18* | −0.28* | −0.29* | −0.12* | −0.28* | −0.22* | −0.19* | −0.34* | 0.21* | 0.02 |

| Anxiety | −0.23* | −0.14* | −0.14* | −0.21* | −0.32* | −0.07 | −0.18* | −0.11* | −0.06 | −0.37* | 0.08 | −0.01 |

Spearman correlation coefficients between change in scores from 10 PROMIS CAT instruments, SF36

subscales, SF-36 summary scores and physician- and patient global assessment scores.

PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, CAT = Computer adaptive testing, SF36 = Short form 36, Vital. = Vitality, PF = Physical function, BP = bodily pain, SF = social function, MH = mental health, GH = general health, RE = role emotional, RP = role physical, PCS = physical component summary MCS = mental component summary, PtGA = Patient global assessment for disease activity, PhGA = Physician global assessment for disease activity.

p<0.05

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that the administration of PROMIS instruments is quite feasible and valid for use among patients with various forms of vasculitis. Adding PROMIS measures to other disease assessment instruments did not prevent a high completion rate. The completion of each PROMIS instrument took less than one minute for most subjects allowing for comprehensive assessment with minimal subject burden. PROMIS measures demonstrated cross-sectional construct validity with respect to SF-36 domains. Change over time in PROMIS measures also appeared to correlate appropriately with differences in SF-36 measures.

Currently-used physician-based measures of disease in vasculitis may not incorporate the impact of symptoms important to patients. Findings from this study support that hypothesis. The current measures are dichotomized to active or non-active disease. By formally using the PROMIS system in the evaluation of potential novel treatments for vasculitis, treatment-related benefits of importance to patients are more likely to be captured. PROMIS measures might also contribute to future definitions of intermediate disease states that cannot be defined with current measures.

Most PROMIS instruments correlated moderately with patient global assessment for disease activity, with the strongest correlations observed for social participation, fatigue, and pain interference. Patient global assessment has been shown to capture a disease aspect that is different from physician-measures and it has some attractive characteristics as an outcome measure(18–19). The underlying constructs of patient global assessments in vasculitis are not known but this analysis offers some insight as to what domains of self-reported health contribute to patient global for disease activity in vasculitis.

None of the 10 PROMIS instruments correlated with the physician global assessment, highlighting that physicians and patients bring different perspectives to the assessment of vasculitis (13, 20) and that information on the life impact of vasculitis must be directly assessed by patients. This is consistent with what has been observed in other rheumatic diseases; that physician-based and patient-based measure capture distinct disease features (21–23). To assess how therapeutic strategies could diminish impact of disease, patient-reported outcomes should be administered as part of randomized controlled trials.

Within each domain, the distributions of the scores from the PROMIS CAT instrument and the short form were almost identical. Correlation coefficients between PROMIS and other measures were also quite similar between the CAT and short form instruments. Future studies may show a degree of separation between the two PROMIS formats and determine if such a difference is meaningful. Therefore, both CAT and short forms are reasonable to use for disease assessment in vasculitis.

There is a clear mandate to formally incorporate the patient perspective into assessment of vasculitis. This study found that instruments from several domains might be of importance. That is informative but does not imply that all the studied domains require representation in outcome measures administered in a trial. The goal should be to arrive at a parsimonious set of instruments that capture the impact of disease and allows for discrimination between treatment arms. This study has identified several domains that might be fit for this purpose. Further studies might identify the optimal items and CAT algorithms for assessment of vasculitis. It is also possible that administration of PROMIS instruments could be feasible in clinical care to obtain assessment of life impact of vasculitis without exhaustively burden patient with filling in forms.

This study had several important strengths. The data source is a well-defined patient cohort with systemic vasculitis followed in a longitudinal fashion at expert centers according to a protocol that provides for evaluations of changes in HRQoL and changes in physician-based disease assessment during the disease course. The large number of patients participating and the comprehensive data acquisition is also notable. The domains under study were chosen with substantial patient input to reflect disease-related manifestations of importance to patients with vasculitis.

This study also has some limitations to consider. First, ss is common in cohorts of patients with vasculitis, participants were in disease remission about 80% of the time. Thus, it remains to be seen how the identified measures will function in trials that enroll patients during a period of highly active disease. Second, the different PRO instruments in this study used different recall periods that might have impacted our findings. Third, no qualitative data or surveys on how patients with vasculitis felt the PROMIS instruments captured disease burden of vasculitis. Fourth, this study was conducted in North-American cohort of vasculitis patients and results might not be generalizable to another cohorts. Translation of most of the PROMIS instruments is underway but validation in non-English speaking cohorts is warranted.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the validity of using PROMIS instruments in vasculitis, the feasibility and construct validity of several PROMIS instruments with systemic vasculitis and expands the options for capturing patient-reported outcomes in the assessment of vasculitis to assess the burden of disease.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This work was supported by The Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium (VCRC) (U54 AR057319 and ROI AR 064153) which is part of the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR), National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS). The VCRC is funded through collaboration between NCATS, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and has received funding from the National Center for Research Resources (U54 RR019497). Additional support for this work was provided by a contract from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (IP2PI000603).

Contributor Information

Gunnar Tomasson, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Iceland, Reykjavik Iceland,; Department of rheumatology, University Hospital, Iceland. Centre for Rheumatology Research, University Hospital, Iceland,

John T. Farrar, Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Informatics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

David Cuthbertson, Department of Biostatistics and Informatics, Department of Pediatrics, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA.

Carol A. McAlear, Division of Rheumatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA..

Susan Ashdown, Oxfordshire, UK.

Peter F. Cronholm, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Jill Dawson, Nuffield Department of Population Health (HSRU), University of Oxford, Old Road Campus, Oxford, UK Don Gebhart MD, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

Georgia Lanier, Boston, MA, USA.

Raashid A. Luqmani, Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Nataliya Milman, Department of Rheumatology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada.

Jacqueline Peck, Faculty of Health and Applied Sciences, University of the West of England, Bristol and School of Clinical Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK.

Judy A. Shea, Division of General Internal Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Simon Carette, Division of Rheumatology, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada.

Nader Khalidi, Division of Rheumatology, St. Joseph’s Healthcare, McMaster University, Hamilton, N, Canada.

Curry L. Koening, Division of Rheumatology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA.

Carol A. Langford, Department of Rheumatology, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Paul A. Monach, Section of Rheumatology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA.

Larry Moreland, Division of Rheumatology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Christian Pagnoux, Division of Rheumatology, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada.

Ulrich Specks, Division of Pulmonology and Critical Care Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Rochester, MN, USA.

Antoine G. Sreih, Division of Rheumatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA..

Steven R. Ytterberg, Division of Rheumatology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN, USA.

Peter A. Merkel, Division of Rheumatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA..

REFERENCES

- 1.Exley AR, Bacon PA, Luqmani RA, Kitas GD, Gordon C, Savage CO, et al. Development and initial validation of the Vasculitis Damage Index for the standardized clinical assessment of damage in the systemic vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:371–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mukhtyar C, Lee R, Brown D, Carruthers D, Dasgupta B, Dubey S, et al. Modification and validation of the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (version 3). Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2009;68:1827–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kupersmith MJ, Speira R, Langer R, Richmond M, Peterson M, Speira H, et al. Visual function and quality of life among patients with giant cell (temporal) arteritis. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2001;21:266–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hellmann DB, Uhlfelder ML, Stone JH, Jenckes MW, Cid MC, Guillevin L, et al. Domains of health-related quality of life important to patients with giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:819–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Direskeneli H, Aydin SZ, Kermani TA, Matteson EL, Boers M, Herlyn K, et al. Development of outcome measures for large-vessel vasculitis for use in clinical trials: opportunities, challenges, and research agenda. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1471–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:1179–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amtmann D, Cook KF, Jensen MP, Chen WH, Choi S, Revicki D, et al. Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain. 2010;150:173–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aydin SZ, Direskeneli H, Sreih A, Alibaz-Oner F, Gui A, Kamali S, et al. Update on Outcome Measure Development for Large Vessel Vasculitis: Report from OMERACT 12. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:2465–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boers M, Kirwan JR, Wells G, Beaton D, Gossec L, d’Agostino MA, et al. Developing core outcome measurement sets for clinical trials: OMERACT filter 2.0. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:745–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basu N, Jones GT, Fluck N, MacDonald AG, Pang D, Dospinescu P, et al. Fatigue: a principal contributor to impaired quality of life in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Rheumatology. 2010;49:1383–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boomsma MM, Bijl M, Stegeman CA, Kallenberg CG, Hoffman GS, Tervaert JW. Patients’ perceptions of the effects of systemic lupus erythematosus on health, function, income, and interpersonal relationships: a comparison with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carpenter DM, Meador AE, Elstad EA, Hogan SL, DeVellis RF. The impact of vasculitis on patients’ social participation and friendships. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:S15–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herlyn K, Hellmich B, Seo P, Merkel PA. Patient-reported outcome assessment in vasculitis provides important data and a unique perspective. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:1639–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minnock P, Kirwan J, Bresnihan B. Fatigue is a reliable, sensitive and unique outcome measure in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2009;48:1533–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Streiner D, Norman G. Selecting the items. Health Measurement Scales A practical guide to their development and use. 4th edition ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr., Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware JE Jr., Sherboume CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomasson G, Davis JC, Hoffman GS, McCune WJ, Specks U, Spiera R, et al. Brief report: The value of a patient global assessment of disease activity in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s). Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:428–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grayson PC, Maksimowicz-McKinnon K, Clark TM, Tomasson G, Cuthbertson D, Carette S, et al. Distribution of arterial lesions in Takayasu’s arteritis and giant cell arteritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1329–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seo P, Min YI, Holbrook JT, Hoffman GS, Merkel PA, Spiera R, et al. Damage caused by Wegener’s granulomatosis and its treatment: prospective data from the Wegener’s Granulomatosis Etanercept Trial (WGET). Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2168–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hewlett S, Sanderson T, May J, Alten R, Bingham CO 3rd, Cross M, et al. ‘I’m hurting, I want to kill myself: rheumatoid arthritis flare is more than a high joint count—an international patient perspective on flare where medical help is sought. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirwan JR, Boonen A, Harrison MJ, Hewlett SE, Wells GA, Singh JA, et al. OMERACT 10 Patient Perspective Virtual Campus: valuing health; measuring outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis fatigue, RA sleep, arthroplasty, and systemic sclerosis; and clinical significance of changes in health. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1728–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neogi T, Xie H, Felson DT. Relative responsiveness of physician/assessor-derived and patient-derived core set measures in rheumatoid arthritis trials. J Rheumatol 2008;35:757–762. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.