Abstract

Background

This is the fourth update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2002 and last updated in 2016. It is common clinical practice to follow patients with colorectal cancer for several years following their curative surgery or adjuvant therapy, or both. Despite this widespread practice, there is considerable controversy about how often patients should be seen, what tests should be performed, and whether these varying strategies have any significant impact on patient outcomes.

Objectives

To assess the effect of follow‐up programmes (follow‐up versus no follow‐up, follow‐up strategies of varying intensity, and follow‐up in different healthcare settings) on overall survival for patients with colorectal cancer treated with curative intent. Secondary objectives are to assess relapse‐free survival, salvage surgery, interval recurrences, quality of life, and the harms and costs of surveillance and investigations.

Search methods

For this update, on 5 April 2109 we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and Science Citation Index. We also searched reference lists of articles, and handsearched the Proceedings of the American Society for Radiation Oncology. In addition, we searched the following trials registries: ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. We contacted study authors. We applied no language or publication restrictions to the search strategies.

Selection criteria

We included only randomised controlled trials comparing different follow‐up strategies for participants with non‐metastatic colorectal cancer treated with curative intent.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. Two review authors independently determined study eligibility, performed data extraction, and assessed risk of bias and methodological quality. We used GRADE to assess evidence quality.

Main results

We identified 19 studies, which enrolled 13,216 participants (we included four new studies in this second update). Sixteen out of the 19 studies were eligible for quantitative synthesis. Although the studies varied in setting (general practitioner (GP)‐led, nurse‐led, or surgeon‐led) and 'intensity' of follow‐up, there was very little inconsistency in the results.

Overall survival: we found intensive follow‐up made little or no difference (hazard ratio (HR) 0.91, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.80 to 1.04: I² = 18%; high‐quality evidence). There were 1453 deaths among 12,528 participants in 15 studies. In absolute terms, the average effect of intensive follow‐up on overall survival was 24 fewer deaths per 1000 patients, but the true effect could lie between 60 fewer to 9 more per 1000 patients.

Colorectal cancer‐specific survival: we found intensive follow‐up probably made little or no difference (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.07: I² = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence). There were 925 colorectal cancer deaths among 11,771 participants enrolled in 11 studies. In absolute terms, the average effect of intensive follow‐up on colorectal cancer‐specific survival was 15 fewer colorectal cancer‐specific survival deaths per 1000 patients, but the true effect could lie between 47 fewer to 12 more per 1000 patients.

Relapse‐free survival: we found intensive follow‐up made little or no difference (HR 1.05, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.21; I² = 41%; high‐quality evidence). There were 2254 relapses among 8047 participants enrolled in 16 studies. The average effect of intensive follow‐up on relapse‐free survival was 17 more relapses per 1000 patients, but the true effect could lie between 30 fewer and 66 more per 1000 patients.

Salvage surgery with curative intent: this was more frequent with intensive follow‐up (risk ratio (RR) 1.98, 95% CI 1.53 to 2.56; I² = 31%; high‐quality evidence). There were 457 episodes of salvage surgery in 5157 participants enrolled in 13 studies. In absolute terms, the effect of intensive follow‐up on salvage surgery was 60 more episodes of salvage surgery per 1000 patients, but the true effect could lie between 33 to 96 more episodes per 1000 patients.

Interval (symptomatic) recurrences: these were less frequent with intensive follow‐up (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.86; I² = 66%; moderate‐quality evidence). There were 376 interval recurrences reported in 3933 participants enrolled in seven studies. Intensive follow‐up was associated with fewer interval recurrences (52 fewer per 1000 patients); the true effect is between 18 and 75 fewer per 1000 patients.

Intensive follow‐up probably makes little or no difference to quality of life, anxiety, or depression (reported in 7 studies; moderate‐quality evidence). The data were not available in a form that allowed analysis.

Intensive follow‐up may increase the complications (perforation or haemorrhage) from colonoscopies (OR 7.30, 95% CI 0.75 to 70.69; 1 study, 326 participants; very low‐quality evidence). Two studies reported seven colonoscopic complications in 2292 colonoscopies, three perforations and four gastrointestinal haemorrhages requiring transfusion. We could not combine the data, as they were not reported by study arm in one study.

The limited data on costs suggests that the cost of more intensive follow‐up may be increased in comparison with less intense follow‐up (low‐quality evidence). The data were not available in a form that allowed analysis.

Authors' conclusions

The results of our review suggest that there is no overall survival benefit for intensifying the follow‐up of patients after curative surgery for colorectal cancer. Although more participants were treated with salvage surgery with curative intent in the intensive follow‐up groups, this was not associated with improved survival. Harms related to intensive follow‐up and salvage therapy were not well reported.

Plain language summary

Follow‐up strategies for participants treated for non‐metastatic colorectal cancer

What is the issue?

Colorectal cancer affects about 1 in 20 people in high‐income countries. Most patients (about two thirds) have curable disease. Follow‐up after surgical resection +/‐ chemotherapy treatment usually means visits to the doctor as well as having some tests. Many people believe that follow‐up saves lives, but we are not sure how often the patient should see the doctor and what tests they should have, and when.

Why is it important?

Follow‐up is expensive, it can make patients anxious around the time of their visit, and can be inconvenient. Tests are expensive and can have side effects. If tests find that cancer has come back in a person who feels well, but treatment cannot cure them, finding the recurrent cancer may not have helped that person or their family.

We asked...

We asked if follow‐up (i.e. tests and doctor visits) after colorectal cancer has been treated curatively is helpful. We looked at all different kinds of follow‐up: some versus none; more tests versus fewer tests; and follow‐up done by surgeons, general practitioners (GPs), or nurses.

We found...

We found 19 studies, including 13,216 participants. Our results are presented along with a judgement of quality which reflects how certain we are about the results. We found that follow‐up did not improve overall survival (high‐quality evidence), colorectal cancer‐specific survival (moderate‐quality evidence), or relapse‐free survival (high‐quality evidence). If patients have follow‐up, they are much more likely to have surgery if the cancer is detected again (high‐quality evidence). With follow‐up, more asymptomatic 'silent' cancer relapses are likely to be found at planned visits (moderate‐quality evidence). Harmful side effects (harms) from tests were not common, but more intensive follow‐up may increase harms (reported in two studies; very low‐quality evidence). Costs may be increased with more intensive follow‐up (low‐quality evidence). More intensive follow‐up probably makes little or no difference for quality of life (moderate‐quality evidence).

This means...

The information we have now suggests that there is little benefit from intensifying follow‐up, but there is also little evidence about quality of life, harms, and costs. We do not know what is the best way to follow patients treated for non‐metastatic (no secondaries) colorectal cancer, or if we should at all. We know little about the costs of follow‐up in this setting. Consumer needs and concerns with respect to the value of follow‐up require further research.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Intensive follow‐up compared to less intensive follow‐up for patients treated for colorectal cancer with curative intent.

| Intensive follow‐up compared to less intensive follow‐up for patients treated for colorectal cancer with curative intent | |||||

|

Participants: people with non‐metastatic colorectal cancer treated with curative intent Setting: primary and secondary care Interventions: more intensive follow‐up (clinic visits and investigations aimed at detecting recurrence) Comparison: less intensive follow‐up | |||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with less intensive follow‐up | Risk difference with intensive follow‐up | ||||

| Overall survival Follow‐up: range 8 months to 134 months | 12,528 (15 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Higha,b | HR 0.91 (0.80 to 1.04) | Study population | |

| 107 per 1000 | 22 fewer per 1000 (60 fewer to 9 more)c | ||||

| Colorectal cancer‐specific survival Follow‐up: range 8 months to 134 months | 11,771 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea,b,d | HR 0.93 (0.81 to 1.07) | Study population | |

| 73 per 1000 | 15 fewer per 1000 (47 fewer to 12 more) | ||||

| Relapse‐free survival Follow‐up: range 48 months to 120 months | 8047 (16 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Higha,b | HR 1.05 (0.92 to 1.21) | Study population | |

| 283 per 1000 | 17 more per 1000 (30 fewer to 66 more) | ||||

| Salvage surgery (surgery at relapse with curative intent) Follow‐up: range 2 months to 134 months | 5157 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Highe | RR 1.98 (1.53 to 2.56) | Study population | |

| 62 per 1000 | 60 more per 1000 (33 more to 96 more) | ||||

| Interval recurrences (recurrence CRC diagnosed between scheduled follow‐up visits) Follow‐up: range 2 months to 134 months | 3933 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatee,f | RR 0.59 (0.41 to 0.86) | Study population | |

| 127 per 1000 | 52 fewer per 1000 (75 fewer to 18 fewer) | ||||

|

Harms Colonoscopy complications ‐ bowel perforation |

326 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very Lowg | RR 6.83 (0.36 to 131.21) |

Study population | |

| 0 per 1000 | 0 fewer per 1000 (0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CRC: colorectal cancer; HR: hazard ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; OR: Peto odds ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

aNot downgraded for imprecision because there were more than 300 events. bConfidence intervals include 1 and exclude clinically meaningful benefit or harm. cWe used the number of events in the control arms of the included studies to derive absolute values. dDowngraded because we deemed 192/468 (41%) events from studies at high risk of bias because of incomplete follow‐up. eNot downgraded because prespecified sensitivity analysis explained heterogeneity on basis of study age. fDowngraded because we deemed 95/178 (58%) events from studies at high risk of bias because of incomplete follow‐up. gDowngraded for risk of bias related to lack of blinding and imprecision.

Background

Description of the condition

Colorectal cancer is a commonly diagnosed malignancy affecting about one person in 20 in most westernised countries (DevCan 2005). Approximately two‐thirds of patients will present with potentially curable disease (by surgery plus or minus adjuvant therapies). Of these, 50% to 60% will relapse with metastatic disease (Lee 2007; Van Cutsem 2006; Yoo 2006). Surgeons, oncologists, and other health professionals caring for people with colorectal cancer have pursued a number of strategies to try to improve clinical outcomes. These have included population screening, better diagnostic testing, improved surgical and anaesthetic techniques, and more widespread utilisation of effective adjuvant therapies.

After definitive treatment is completed, clinician attention turns to follow‐up strategies designed to detect recurrence at a stage when further curative procedures can be used. Follow‐up strategies have also been developed in order to detect new curable metachronous (i.e. occurring at different times) primary tumours. There is overlap between these two strategies; this current review focuses on the former issue of strategies designed to detect curable recurrences of the original cancer. These include recurrences that are localised in either the lung, liver, abdomen, or pelvis and can be completely resected or ablated with curative intent.

Following patients after definitive treatment for cancer has become a traditional component of medical care (Edelman 1997). It is likely that clinicians follow patients after curative treatment for colorectal cancer at least in part to provide positive feedback on their management but also to assess the toxicities of treatment and to provide more accurate outcome data (Audisio 1996). Patients and their clinicians develop relationships during treatment and follow‐up that can make it hard to discharge patients and return responsibility for care back to their primary physician in the community (Audisio 2000). As a result, a practising clinician can accumulate a large number of follow‐up patients, and the surveillance of this cohort consumes significant resources.

The opportunity cost of the resources involved is considerable, limiting the care that the clinician can provide for other individuals. Few clinicians restrict colorectal cancer follow‐up visits to clinical examination only, and the temptation to order routine investigations is often reinforced by patients who desire tests to 'prove' that their disease is under control (Audisio 2000; Kievit 2000). Clinicians justify this approach by claiming that recurrences are being detected earlier than would otherwise occur and that patient outcomes are improved as a result (Kievit 2000).

Description of the intervention

Follow‐up programmes in colorectal cancer should be based on the anatomic and temporal patterns of recurrence (Audisio 2000; Edelman 1997). The most important phase of follow‐up is the first two to three years after primary resection, as during this time, the majority of recurrences will become apparent (Böhm 1993; Ovaska 1989). The liver is the most common site of metastases from colorectal cancer. A small proportion of these patients (10% to 20%) will have liver metastases that are distributed within the liver in such a fashion that makes them amenable to surgical resection or ablation (Alberts 2005; Muratore 2007). Published series of patients undergoing such surgical interventions (with significant numbers of long‐term survivors) encourage this approach (Choti 2002; Kanas 2012; Pawlik 2005). A number of strategies have been proposed to detect liver metastases at an early stage in order to identify such patients; these include the monitoring of blood tests (liver function, level of serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)), and routine imaging of the liver and lung (Fleischer 1989; Sugarbaker 1987).

The psychological outcomes of follow‐up programmes for people with cancer can be positive or negative. Positive outcomes include reassurance and support. The negative outcomes include false reassurance, increased anxiety, fear and disappointment associated with early detection of an incurable recurrence, morbidity and mortality associated with procedures performed as a result of abnormal results, and distress caused by false‐positive results. Appropriate quality‐of‐life measurements could provide information about these outcomes.

Follow‐up can comprise clinic visits, examinations, and tests (blood tests and endoscopic and radiological examinations). More intensive follow‐up may consist of an increased frequency of clinic visits, tests, and examinations in comparison with none or fewer clinic visits, tests, and examinations.

How the intervention might work

Follow‐up programmes in colorectal cancer are thought to increase the early detection of recurrence at a stage when further curative procedures can be used, as well as new curable metachronous primary tumours, thereby, improving survival outcomes (GILDA 1998).

Why it is important to do this review

Whether systematic follow‐up can alter long‐term clinical outcomes for colorectal cancer remains controversial (Pfister 2004). Whilst some commentators have concluded that follow‐up is worthwhile (Gerdes 1990), others have questioned its effectiveness (Kievit 2000; McArdle 2000). The variation in follow‐up programmes, in terms of timing and frequency of clinician visits and the investigations undertaken by clinicians, is considerable (Collopy 1992; Connor 2001; Vernava 1994; Virgo 1995). Routine follow‐up has the potential to create psychological harm in patients, and any such disadvantages need to be outweighed by improved clinical outcomes (such as overall survival) that matter to patients. Data from follow‐up studies in other cancers (e.g. breast cancer and overall survival) is not encouraging in this regard (Rojas 2005).

Therefore, we conducted a systematic review of randomised controlled trials exploring questions relating to the effectiveness of follow‐up strategies in colorectal cancer patients treated with curative intent.

Objectives

To assess the effect of follow‐up programmes (follow‐up versus no follow‐up, follow‐up strategies of varying intensity, and follow‐up in different healthcare settings) on overall survival for patients with colorectal cancer treated with curative intent. Secondary objectives are to assess relapse‐free survival, salvage surgery, interval recurrences, quality of life, and the harms and costs of surveillance and investigations.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing different follow‐up strategies for participants with colorectal cancer. These included comparisons of follow‐up versus no follow‐up, follow‐up strategies of varying intensity (differing frequency or quantity of testing, or both), and follow‐up in different healthcare settings (e.g. primary care versus hospital). Cluster‐RCTs were eligible.

Types of participants

Male and female patients of any age with histologically proven adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum, staged as T1‐4N0‐2M0 (Edge 2010), treated surgically with curative intent (plus or minus adjuvant treatment).

Types of interventions

Follow‐up visits with any health professionals in any setting, including symptom enquiry, clinical examination, and procedures and investigations (including but not limited to colonoscopy, blood tests, faecal analysis, and radiological examinations).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Overall survival (measured from the time of randomisation in the study)

Secondary outcomes

Colorectal cancer‐specific survival (measured from the time of randomisation in the study)

Relapse‐free survival (measured from the time of randomisation in the study)

Salvage surgery (surgery performed with curative intent for relapse of colorectal cancer)

Interval recurrences (relapse of colorectal cancer detected between follow‐up visits)

Quality of life (using study‐specific instruments, including but not limited to FACT (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy), EORTC QLQ‐C30 (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life), and EORTC‐CRC (Cella 1993; Sprangers 1993; Whistance 2009)

Harms, including but not limited to psychological harms, investigation‐related complications, and waste of resources

Costs of surveillance (including investigations)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases with no language restriction:

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 4) in the Cochrane Library using the strategy in Appendix 1;

MEDLINE Ovid (from 1950 to 5 April 2019) using the strategy in Appendix 2;

Embase Ovid (from 1974 to 5 April 2019) using the strategy in Appendix 3;

CINAHL EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; from 1981 to April 2019) using the strategy in Appendix 4; and

Science Citation Index (from 1900 to April 2019) using the strategy in Appendix 5.

For the Review first published in the Cochrane Library 2002 issue 1, we also searched the electronic database CANCERLIT, which stopped existing in 2003.

Searching other resources

Trials registries

We searched the following trials registries:

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov; www.clinicaltrials.gov; (searched April 2019); and

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform; apps.who.int/trialsearch; (searched April 2019).

Handsearching

We searched the following journals and conference proceedings:

American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) (1995 to 2010, 2012‐2018);

European Society for Therapeutic and Radiation Oncology (1990, 1993, 2000 to 2010, 2012 to 2018); and

International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics: proceedings of the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) (2011 to 2018).

We searched reference lists of published articles and previous systematic reviews and made personal contact with experts. We identified non‐English and unpublished studies.

Grey literature

We searched OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu; 8 April 2019).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (BEH and GMJ) checked the titles and abstracts identified from the databases. The review authors obtained the full text of all studies of possible relevance for independent assessment, decided which studies met the inclusion criteria, and graded their methodological quality. Discussion between the review authors resolved any disagreement. We contacted authors of primary studies for clarification where necessary: we contacted the authors for Barillari 1996 on 10 November 2018 but have had no response. We did not use the reported outcomes as criteria for including studies. We included studies irrespective of their publication status. We documented the selection process using Covidence and presented the details of the search in a PRISMA diagram (Moher 2009). Reasons for exclusion are presented in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. We collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study, rather than the report, was the unit of interest in the review, and we identified the primary source.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (BEH and GMJ) independently performed data extraction; we contacted the authors of studies to provide missing data where possible. We entered data into a previously piloted data form then into Covidence. One review author (BEH) entered data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5), which a second author (AS) checked (Review Manager 2014). We resolved any disagreements by discussion. We extracted the following data when available:

number of participants;

the age and status of the participants;

inclusion and exclusion criteria;

setting;

treatment regimen;

follow‐up details; and

survival, adverse events, and quality‐of‐life indices.

We collected data that were sufficient to populate a table of characteristics of included studies. For studies where only a subset of the participants recruited were eligible for inclusion, we included them if they reported data for that subgroup separately. Where a study had more than one study arm, such as FACS 2014, we combined those intervention study arms that met the inclusion criteria and compared them with the control arm; this ensured we did not double‐count data. When we performed subgroup analysis for FACS 2014, we combined the two arms with measured carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and the two arms that used computerised tomography (CT). We compared the magnitude and direction of effects reported by studies with how they were presented in the review.

In order to report time‐to‐event data, we used the RevMan 5 calculator (Review Manager 2014), and a spreadsheet developed by Matthew Sydes (Tierney 2007), to derive observed (O) and log‐rank expected events (E) (O‐E) and variance. Tierney 2007 presents 11 methods for calculating a hazard ratio (HR) or associated statistics, or both, from published time‐to‐event‐analyses into a practical, less statistical guide. The methods we used to do so were dependent on the available information in the texts, and we report them as follows.

Reports presenting HRs and 95% confidence intervals allowed application of method 3 in Tierney 2007 and were available for analysis as follows:

overall survival (FACS 2014; ONCOLINK; Strand 2011; Treasure 2014; Wang 2009 (please note that for Wang 2009, we used the RevMan 5 calculator to derive the HR, because this agreed with the P value given in the text));

colorectal cancer‐specific survival (FACS 2014; ONCOLINK; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006); and

relapse‐free survival (FACS 2014; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998; Secco 2002; Strand 2011; Treasure 2014).

In reports with a P value, events in each arm, and where the randomisation ratio was 1:1, we used method 7 in Tierney 2007 to derive O‐E and variance. Such studies contributed to the following analyses:

overall survival (GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Ohlsson 1995; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998 (for Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006, we used the RevMan 5 calculator to derive the HR, because the statistic presented in the text was adjusted for confounding; this was also the approach that the systematic review Pita‐Fernández 2014 used for this study));

colorectal cancer‐specific survival (Kjeldsen 1997; Ohlsson 1995); and

relapse‐free survival (GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006).

In reports where we extracted data from the survival curve, assuming constant censoring, we used method 10 in Tierney 2007 for two studies contributing to the outcome of overall survival (Mäkelä 1995; Pietra 1998).

For relapse‐free survival, we extracted curve data with numbers at risk (method 11) for Sobhani 2018.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two study authors (BEH and GMJ) constructed and presented 'Risk of bias' tables using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool, resolving any disagreements by discussion (Higgins 2017). We evaluated the following domains:

random sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding of participants and personnel;

blinding of outcome assessment;

incomplete follow‐up (exclusions, attrition);

selective reporting; and

other bias, including but not limited to early stopping, inadequate duration of follow‐up, or baseline imbalances.

We graded domains as at low risk of bias, high risk of bias, or unclear risk of bias (using the criteria in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Table 8.5d) (see Appendix 6), with our reasons and supporting evidence detailed in the tables (Higgins 2017). We summarised the risk of bias for each of the key study outcomes (overall survival, disease‐specific survival, relapse‐free survival, salvage surgery, interval recurrences, and complications of colonoscopy).

Measures of treatment effect

Where possible, we conducted time‐to‐event analyses for overall survival, colorectal cancer‐specific survival, and relapse‐free survival. We expressed the results as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) when the relevant information was available in the text or could be derived. Where necessary, we derived the HR using the RevMan 5 calculator (Review Manager 2014), and calculated associated statistics using an Excel spreadsheet developed by Matthew Sydes (Cancer Division of the Medical Research Council (MRC) Clinical Trials Unit) in collaboration with the Meta‐analysis Group of the MRC Clinical Trials Unit, London (Tierney 2007). We reported risk ratios (RR) and 95% CIs for dichotomous outcomes and would use the mean difference and 95% CI to report continuous outcomes. In the case of rare events (Analysis 1.6) we used the Peto odds ratio (OR; Deeks 2017). We interpreted a statistically non‐significant result (P value larger than 0.05) as a finding of uncertainty unless the confidence intervals were sufficiently narrow to rule out a potentially important magnitude of effect. We defined confidence intervals between 0.75 and 1.25 as excluding clinically meaningful benefits or harms.

Unit of analysis issues

All of the RCTs were parallel in design, with participants being the unit of randomisation; therefore, we had no unit of analysis issues.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the authors of Secco 2002 to request the raw data. We were informed on 20 April 2015 that because of personnel changes, the authors were unable to retrieve the data, which meant we were not able to report overall survival data for this study. Because they plotted two curves for each study arm, it was not possible to extract data for use in time‐to‐event analysis. We were in contact with the study authors for GILDA 1998 on 18 February 2016, who kindly provided us with unpublished data, which we were able to include for the outcomes 'Interval recurrences' and 'Salvage surgery' (Fossati 2015). Therefore, all analyses were by intention‐to‐treat.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity both visually and statistically using the Chi² test of heterogeneity (Altman 1992; Walker 1988), and I² statistic (Deeks 2017; Higgins 2002). The criterion for identification of heterogeneity is a P value less than 0.10 for the Chi² test (acknowledging the limitations of this process) and an I² statistic value of greater than 50%. Where we identified significant heterogeneity, we first checked the data to ensure it was not due to error, explored the potential causes of it, and made a cautious attempt to explain the heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed the potential impact of reporting biases by the use of a funnel plot for the four outcomes that included data from 10 or more studies (overall survival, cancer‐specific survival, relapse‐free survival, and salvage surgery). Including 15 studies allowed us to visually assess whether small‐study effects were present or not.

Data synthesis

We calculated a weighted treatment effect (using a random‐effects model) across studies using the Cochrane statistical package in RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2014). Where O‐E and variance were available, we used a log‐rank approach and a fixed‐effect model to synthesise data. We summated data where we judged the participants, interventions, and outcomes to be sufficiently similar to ensure a clinically meaningful answer.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We used subgroup analyses to investigate possible differences in participant outcomes according to study variables that we believed could be effect modifiers. These included the use of CEA, CT, and PET‐CT (positron emission tomography–computed tomography) in the intensive follow‐up strategy when compared with no use or less frequent use (twice at most) in the control arm, and setting for follow‐up (general practitioner (GP)‐ or nurse‐led follow‐up compared with hospital follow‐up and 'dose' of follow‐up, that is, studies that compared the use of more visits and tests with fewer visits and tests). These subgroup analyses may help identify which investigations are useful in follow‐up for colorectal cancer and allow us to give specific guidance to clinicians. We used a formal statistical test to compare subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed prespecified sensitivity analyses to test the strength of our conclusions by excluding studies judged to be at high risk of bias for the particular outcome concerned (Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Pietra 1998; Schoemaker 1998; Wang 2009), and by study age (excluding those studies that completed accrual by 1996) (Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; Pietra 1998; Schoemaker 1998; Treasure 2014).

We performed post hoc sensitivity analysis in response to reviewer suggestion by excluding one study (Ohlsson 1995), where the intensity of follow‐up in the intensive arm was comparable with the intensity of follow‐up in the control arm of other studies.

'Summary of findings' tables

We evaluated the quality of evidence using the GRADE approach for the following outcomes (Schünemann 2013):

overall survival;

colorectal cancer‐specific survival;

relapse‐free survival;

salvage surgery;

interval recurrences; and

harms associated with surveillance.

We used GRADEpro GDT to present the quality of evidence for the aforementioned outcomes in 'Summary of findings' tables. We could downgrade the quality of the evidence by one (serious concern) or two levels (very serious concern) for the following reasons: risk of bias, inconsistency (unexplained heterogeneity, inconsistency of results), indirectness (indirect population, intervention, control, outcomes), imprecision (wide confidence intervals, single study), and publication bias. We could also downgrade the quality by one level due to a large summary effect.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

For this update, we screened 7571 references, of which we assessed 33 references in full. We identified four new studies for inclusion (CEAwatch 2015; COLOFOL 2018; Sobhani 2018; SurvivorCare 2013), and we identified 9 additional references for four previously included studies (FACS 2014; ONCOLINK; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Treasure 2014). In this update, we moved nine references referring to three studies that were previously either ongoing or awaiting assessment to included studies. We identified four new ongoing studies (COLOPEC; FURCA; ProphyloCHIP; SCORE).

In summary, this updated version of the review now includes a total of 82 references:

63 references refer to 19 included studies (CEAwatch 2015; COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; ONCOLINK; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998; Secco 2002; Sobhani 2008; Sobhani 2018; Strand 2011; SurvivorCare 2013; Treasure 2014; Wang 2009; Wattchow 2006);

five references refer to four excluded studies (Kronborg 1981; NCT00182234; Sano 2004; Serrano 2018);

three references refer to three studies awaiting assessment (Barillari 1996; NCT00199654; UMN000001318); and

11 references refer to six ongoing studies (COLOPEC; FURCA; HIPEC; ProphyloCHIP; SCORE; SURVEILLANCE).

There was considerable variation in the follow‐up strategies employed by the 19 studies; both the frequency of, the setting for, and the investigations that were performed during follow‐up visits were different in each study (see the 'Characteristics of included studies' tables and Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

Similarities and differences between the included studies

Thirteen of the 19 studies were multicentred (CEAwatch 2015; COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Ohlsson 1995; ONCOLINK; Pietra 1998; Schoemaker 1998; Sobhani 2018; SurvivorCare 2013; Treasure 2014; Wattchow 2006). We identified one cluster‐RCT (CEAwatch 2015).

Participants

Eleven of the 19 studies included Dukes' stage A, B, and C colon and rectal cancer (CEAwatch 2015; FACS 2014; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; ONCOLINK; Schoemaker 1998; SurvivorCare 2013; Treasure 2014; Wang 2009; Wattchow 2006). Six studies excluded Dukes' A participants (COLOFOL 2018; GILDA 1998; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Secco 2002; Sobhani 2018), two studies excluded participants with rectal cancer (Pietra 1998; Wattchow 2006), and one study included only rectal cancer participants (Strand 2011). Sobhani 2018 included some participants with completely resected Stage IV disease.

Interventions

The studies can be grouped into the following areas of assessment:

'dose' of follow‐up: more visits and tests versus fewer visits and tests (CEAwatch 2015; COLOFOL 2018; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Secco 2002; Sobhani 2018; Treasure 2014; Wang 2009);

formal follow‐up versus minimal/no follow‐up (COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; Ohlsson 1995; Schoemaker 1998; Secco 2002);

more liver imaging versus less liver imaging (COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; GILDA 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998; Sobhani 2018);

CEA versus no CEA (CEAwatch 2015; COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; Kjeldsen 1997; Ohlsson 1995; Sobhani 2018; Treasure 2014);

setting for follow‐up (where frequency of visits and tests were identical in both arms): GP‐led follow‐up (ONCOLINK; Wattchow 2006), or nurse‐led follow‐up (Strand 2011), compared with surgeon‐led follow‐up;

usual follow‐up care was supplemented by provision of survivorship educational materials, a survivorship care plan, end of treatment consultation and subsequent phone calls (SurvivorCare 2013).

The included studies did not assess the quality of histopathology.

Outcomes

Fifteen RCTs reported overall survival (COLOFOL 2018; CEAwatch 2015; FACS 2014; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; ONCOLINK; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998; Sobhani 2018; Strand 2011; Treasure 2014; Wang 2009).

Eleven RCTs reported colorectal cancer‐specific survival, measured from the time of randomisation in the study ((CEAwatch 2015; COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Ohlsson 1995; ONCOLINK; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Sobhani 2018; Wang 2009).

Sixteen RCTs reported relapse‐free survival, measured from the time of randomisation in the study (COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; ONCOLINK; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998; Secco 2002; Sobhani 2008; Sobhani 2018; Strand 2011; Treasure 2014; Wang 2009).

Thirteen RCTs reported salvage surgery, that is, surgery performed with curative intent for relapse of colorectal cancer (FACS 2014; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; ONCOLINK; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998; Secco 2002; Sobhani 2008; Treasure 2014; Wang 2009).

Seven RCTs reported interval recurrences, relapse of colorectal cancer detected between follow‐up visits or symptomatic recurrences (FACS 2014; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Secco 2002; Sobhani 2008; Wang 2009).

-

Seven RCTs assessed quality of life (CEAwatch 2015; COLOFOL 2018; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; ONCOLINK; SurvivorCare 2013; Wattchow 2006).

CEAwatch 2015 used a Dutch version of the Cancer Worry Scale (Custers 2014), measured participant attitudes to follow‐up using a validated tool (Stiggelbout 1997), and reported using the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond 1983).

COLOFOL 2018 used SF‐36 and validated scales (EORTC QLQ C‐30 (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire; Aaronson 1993)) and reported using the HADS (Zigmond 1983).

GILDA 1998 used the 12‐item short version (SF‐12) of SF‐36 (Apolone 1998; Gandek 1998), which was validated in the Italian population, and the Psychological General Well‐Being (PGWB) Index (Dupuy 1984).

Kjeldsen 1997 used the Nottingham Health Profile (Anderson 1996; Hunt 1980).

ONCOLINK used validated scales EORTC QLQ C‐30 (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire; Aaronson 1993) and EQ‐5D (EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire; Dolan 1997);

SurvivorCare 2013 assessed psychological distress using the Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI‐18; Zabora 2001), survivors' unmet needs using Cancer Survivors' Unmet Need measure (CaSUN; Hodgkinson 2007), health‐related quality of life using EORTC QLQ C‐30 (Aaronson 1993), and the EORTC QLQ CR‐29 (Whistance 2009).

Wattchow 2006 reported the short form (SF)‐12 Physical and Mental Health component (Ware 1995), and reported using the HADS (Zigmond 1983).

Schoemaker 1998 and Wang 2009 reported harms.

Six studies evaluated costs of surveillance including investigations (CEAwatch 2015; ONCOLINK; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Secco 2002; Sobhani 2018; Strand 2011). ONCOLINK and Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006 performed cost‐minimisation analyses.

See Characteristics of included studies.

Study accrual dates spanned over three decades. Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; Pietra 1998; Schoemaker 1998; Secco 2002; and Treasure 2014 accrued in the 1980s and 1990s. GILDA 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Sobhani 2008; and Wang 2009 accrued participants in the 1990s and early 2000s. CEAwatch 2015; COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; ONCOLINK; and Sobhani 2018 accrued participants from 2003 to 2012.

The variety of investigations used across the studies may affect the applicability of results. For example, Kjeldsen 1997; ONCOLINK; and Treasure 2014 did not use CT scanning, while Sobhani 2018 used PET/CT.

Excluded studies

For this update, we applied the current recommendations from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions with respect to excluded studies and only classified studies as excluded if they were those that one might reasonably expect could have been eligible for inclusion.

We excluded four studies (see the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables). Sano 2004 was not eligible because participants did not have colorectal cancer. NCT00182234 included participants with both breast and colorectal cancer and did not analyse them separately. Participants in Serrano 2018 had liver metastases, so were not eligible for inclusion in this review.

Risk of bias in included studies

There was complete concordance between review authors regarding the evaluation of study methodology (Figure 2).

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included study

Allocation

Although all of the studies were reported to be randomised, only two explicitly reported that they concealed the allocation of participants to study groups (Mäkelä 1995; Wattchow 2006). We found that none of the studies were at high risk of bias with respect to allocation; we judged them all to be at low (COLOFOL 2018; CEAwatch 2015; FACS 2014; ONCOLINK; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998; Treasure 2014) or unclear risk of bias (GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; Pietra 1998; Secco 2002; Sobhani 2008; Sobhani 2018; Strand 2011; SurvivorCare 2013; Wang 2009; Wattchow 2006).

Blinding

Participant or clinician blinding was not possible. We judged one study to be at high risk of bias for blinding of participants ( Wang 2009). One study used independent radiologists who were blinded to study group allocation to assess CT scans (Schoemaker 1998). We judged three studies to be at high risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessors (Kjeldsen 1997; Sobhani 2018; Wang 2009). Most studies were at low risk of bias for blinding Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; ONCOLINK; Pietra 1998; Schoemaker 1998;Secco 2002; Sobhani 2008; Strand 2011; Treasure 2014; Wattchow 2006 and five were at unclear risk of bias (CEAwatch 2015; COLOFOL 2018; GILDA 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; SurvivorCare 2013).

Incomplete outcome data

Eight studies ensured that they obtained outcome data from more than 80% of the participants. Wattchow 2006 obtained outcome data for 77% of the participants. All studies conducted intention‐to‐treat analyses. We judged one study to be at high risk of bias for incomplete outcome data (Pietra 1998). Two studies examined compliance with the follow‐up regimen (Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998), but no study fully assessed contamination. Most studies (CEAwatch 2015; COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; ONCOLINK; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998; Sobhani 2008; Sobhani 2018; SurvivorCare 2013; Wattchow 2006) were at low risk of attrition bias, four studies were unclear risk of attrition bias (Secco 2002; Strand 2011; Treasure 2014; Wang 2009).

Selective reporting

We did not have access to the protocols for most studies (CEAwatch 2015; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; ONCOLINK; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998; Secco 2002; Sobhani 2008; Strand 2011; Wang 2009; Wattchow 2006), so we judged them to be at unclear risk of bias. With more information available we judged COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; SurvivorCare 2013 and Treasure 2014 to be at low risk of bias for this domain (see Characteristics of included studies). We judged one study at high risk of bias for selective reporting (Sobhani 2018).

Other potential sources of bias

We did not find other sources of bias (including inadequate follow‐up duration and baseline imbalances on study populations). One study was stopped early (Treasure 2014), but we did not feel this was likely to introduce bias.

Overall survival

We judged four studies contributing data to this outcome to be at high risk of bias because they did not mention blinding (Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Secco 2002; Wang 2009). We did not feel this represented any risk of bias for this objective outcome. We deemed three studies at high risk of bias for allocation concealment, Mäkelä 1995; Schoemaker 1998, and attrition bias, Pietra 1998, but because they contributed in total 17.2% of study weight, we did not feel that we needed to downgrade for risk of bias.

Colorectal cancer‐specific survival

We judged Pietra 1998 to be at high risk of attrition bias because the study authors potentially excluded 15% of the participants randomised without explaining to which study arm they belonged. Sobhani 2018 was at high risk of bias for lack of blinding of outcome assessors. These two studies contributed in total 11.9% of study weight for this outcome. Kjeldsen 1997 and Pietra 1998 did not mention blinding and probably did not ensure it (this represented 41% of the events contributing to this outcome). Because this could cause ascertainment bias for cause of death, we downgraded evidence quality for colorectal cancer‐specific survival for risk of bias.

Relapse‐free survival

For this outcome, Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995 and Secco 2002 (which contributed 383/1340 (28%) of the events) did not mention blinding. We judged both Sobhani 2018 and Schoemaker 1998 at high risk of bias for lack of blinding, but we did not downgrade, because fewer than 30% of events were contributed from studies deemed at high risk of bias.

Salvage surgery

We judged Schoemaker 1998 to be at high risk of bias for allocation concealment. We also deemed three other studies contributing to this outcome to be at high risk of bias: Kjeldsen 1997 and Wang 2009 for lack of blinding of outcome assessment, Pietra 1998 for incomplete outcome reporting, and Wang 2009 further did not blind participants and personnel. We did not downgrade for risk of bias despite these limitations, because Schoemaker 1998 contributed only 11/526 (0.05%) of the events for this outcome, lack of blinding was unlikely to have affected the outcome reporting of salvage surgery, and the incomplete outcome reporting in Pietra 1998 was related to other outcomes.

Interval recurrences

We did not downgrade this outcome for risk of bias. We judged FACS 2014 to be at low risk of bias for all domains. We judged both Secco 2002 and Wang 2009 to be at high risk of bias for the domain of blinding, but this was because blinding was not mentioned in Wang 2009, and in Secco 2002, there were prespecified follow‐up schedules. We did not downgrade this outcome for risk of bias (Risk of bias in included studies and Table 1).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

1. Primary outcome

1.1 Overall survival

We report on 1453 deaths in 12,528 participants in 15 studies. Intensive follow‐up versus less intense follow‐up for participants treated with curative intent for colorectal cancer makes little or no difference to overall survival (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.04; 15 studies, 12,528 participants). We found no evidence of heterogeneity: I² = 18%, P = 0.25. In absolute terms, the average effect of intensive follow‐up on overall survival was 24 fewer deaths per 1000 participants, but the true effect could lie between 60 fewer to 9 more per 1000 participants. The GRADE assessment of evidence quality for this outcome was high. The funnel plot did not show evidence of small study effect (COLOFOL 2018; CEAwatch 2015; FACS 2014; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; ONCOLINK; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998; Sobhani 2018; Strand 2011; Treasure 2014; Wang 2009; Figure 3).

3.

Funnel plot of comparison 1. Intensive follow‐up versus minimalist follow‐up, outcome: 1.1 overall survival

Subgroup analyses

We compared studies comparing follow‐up provided by different health professionals. Formal testing for subgroup differences was negative (Chi² = 0.40; P = 0.53; I² = 0%) when we compared those studies that used different settings with GP‐ or nurse‐led follow‐up (ONCOLINK; Strand 2011), with those set in hospitals (CEAwatch 2015; COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998; Sobhani 2018; Treasure 2014; Wang 2009; Analysis 1.7).

In studies that compared more visits and tests with fewer visits and tests (Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Sobhani 2018; Treasure 2014; Wang 2009), versus studies that compared follow‐up with minimal or no follow‐up (COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; Ohlsson 1995; Schoemaker 1998), formal testing for subgroup differences was negative (Chi² = 0.34; P = 0.56 ; I² = 0 %; Analysis 1.8).

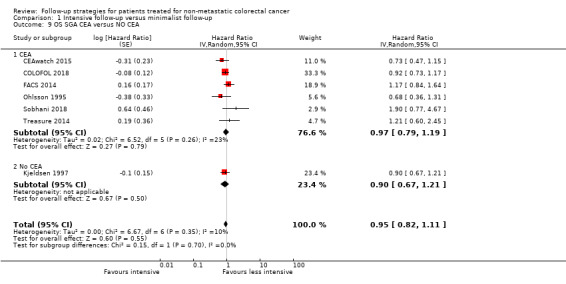

In studies using CEA in the intensive follow‐up regimen (CEAwatch 2015; COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; Ohlsson 1995; Sobhani 2018; Treasure 2014) versus those studies that did not use CEA (Kjeldsen 1997), formal testing revealed no evidence of differences between the subgroups (Chi² = 0.15 ; P = 0.7, I² = 0% (Analysis 1.9).

We compared studies using CT in the intensive follow‐up regimen (COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998; Sobhani 2018) versus those that did not use CT (Kjeldsen 1997; ONCOLINK; Treasure 2014). Formal statistical testing revealed no evidence of differences between the subgroups (Chi² = 0.31; P = 0.58; I² = 0% (Analysis 1.10)

We compared studies using frequent CT scans in the intervention arm (FACS 2014; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998) versus the use of two or fewer CT scans in the control arm (Kjeldsen 1997; ONCOLINK; Treasure 2014) (Analysis 1.11). Formal statistical testing revealed no evidence of differences between the subgroups (Chi² = 0.99; P = 0.32: I² = 0%).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intensive follow‐up versus minimalist follow‐up, Outcome 7 Overall survival SG Healthcare professional.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intensive follow‐up versus minimalist follow‐up, Outcome 8 Overall survival SGA "dose" of follow‐up.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intensive follow‐up versus minimalist follow‐up, Outcome 9 OS SGA CEA versus NO CEA.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intensive follow‐up versus minimalist follow‐up, Outcome 10 OS CT versus no CT.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intensive follow‐up versus minimalist follow‐up, Outcome 11 OS CT versus < 2 or no CT.

Sensitivity analyses

Our findings for the outcome of overall survival were robust to sensitivity analyses.

Excluding studies at high risk of bias for this outcome (Schoemaker 1998; Pietra 1998), we found no statistical evidence of a survival advantage for the comparison of intensive versus less intensive follow‐up (HR 0.97, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.08). We found no heterogeneity: I² = 0%; P = 0.68, The GRADE assessment of evidence quality for this outcome was high.

Excluding six studies on the basis of study age (Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; Pietra 1998; Schoemaker 1998; Treasure 2014), we found no statistical evidence of a survival advantage for the comparison of intensive versus less intensive follow‐up (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.15; Analysis 1.1). We found little evidence of heterogeneity: I² = 18%; P = 0.28. The GRADE assessment of evidence quality for this outcome was high.

Excluding one study where the intensity of the follow‐up in the 'intensive' arm was similar to that in the control arm of other studies (Ohlsson 1995), we found no evidence of a clinically meaningful effect on overall survival (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.05). We found no evidence of heterogeneity: I² = 20%; P = 0.24. The GRADE assessment of evidence quality for this outcome was high.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intensive follow‐up versus minimalist follow‐up, Outcome 1 Overall survival.

2. Secondary outcomes

2.1 Colorectal cancer‐specific survival

We were able to report on 925 colorectal cancer deaths in 11,771 participants enrolled in 11 studies; 99.6% had a median follow‐up of greater than 48 months. We found that intensive versus less intensive follow‐up probably makes little or no difference to colorectal cancer‐specific survival (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.07). We found no evidence of heterogeneity: I² = 0%, P = 0.57 (CEAwatch 2015; COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Ohlsson 1995; ONCOLINK; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Sobhani 2018; Wang 2009; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intensive follow‐up versus minimalist follow‐up, Outcome 2 Colorectal cancer‐specific survival.

In absolute terms, the average effect of intensive follow‐up on colorectal cancer‐specific survival was five fewer colorectal cancer‐specific deaths per 1000 participants, but the true effect could lie between 14 fewer to five more per 1000 participants. The GRADE assessment of evidence quality for this outcome was moderate, we downgraded once for risk of bias. The funnel plot did not show evidence of small study effect (Figure 4).

4.

Funnel plot of comparison 1. Intensive follow‐up versus minimalist follow‐up, outcome: 1.2 colorectal cancer‐specific survival

Sensitivity analyses

Our findings for the outcome of colorectal cancer‐specific survival were robust to the following sensitivity analyses.

Excluding studies at high risk of bias for this outcome (Kjeldsen 1997; Sobhani 2018; Wang 2009), we found no statistical evidence of an effect on colorectal cancer‐specific survival (HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.06) and no evidence of heterogeneity: I² = 0%; P = 0.43.

We found no statistical evidence of study age having an effect (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.23) and no evidence of heterogeneity: I² = 30%; P = 0.22 (excluding GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Ohlsson 1995).

2.2 Relapse‐free survival

We were able to report on 2254 relapses in 8047 participants enrolled in 16 studies, with a median follow‐up of greater than 48 months for 97.9% of participants studied (COLOFOL 2018; FACS 2014; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; ONCOLINK; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998; Secco 2002; Sobhani 2008; Sobhani 2018; Strand 2011; Treasure 2014; Wang 2009; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intensive follow‐up versus minimalist follow‐up, Outcome 3 Relapse‐free survival.

We found intensive follow‐up versus less intense follow‐up makes little or no difference to relapse‐free survival (HR 1.05, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.21). The CIs excluded both clinically meaningful benefits and harms. We found no evidence of heterogeneity: I² = 41%, P = 0.05.

The funnel plot did not show evidence of small‐study effect (Figure 5).

5.

Funnel plot of comparison 1. Intensive follow‐up versus minimalist follow‐up, outcome: 1.3 relapse‐free survival

The average effect of intensive follow‐up on relapse‐free survival was 12 more relapses per 1000 participants, but the true effect could lie between 19 fewer and 48 more per 1000 participants. The GRADE assessment of evidence quality for this outcome was high.

Sensitivity analyses

Our findings for the outcome of relapse‐free survival were robust to the following sensitivity analyses.

Excluding studies at high risk of bias for this outcome (Kjeldsen 1997; Pietra 1998; Schoemaker 1998; Sobhani 2018; Wang 2009), we found no statistical evidence of an effect (HR 1.13, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.33) and no clear evidence of heterogeneity: I² = 40%; P = 0.08.

With regard to study age (excluding GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; Pietra 1998; Schoemaker 1998; Treasure 2014), we found no statistical evidence of an effect (HR 1.05, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.40) and little evidence of heterogeneity: I² = 30%; P = 0.21.

2.3 Salvage surgery

We were able to report on 457 episodes of salvage surgery in 5157 participants enrolled in 13 studies, with a follow‐up duration of greater than 48 months in 90.6% of participants studied (FACS 2014; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; ONCOLINK; Pietra 1998; Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006; Schoemaker 1998; Secco 2002; Sobhani 2008; Treasure 2014; Wang 2009; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intensive follow‐up versus minimalist follow‐up, Outcome 4 Salvage surgery.

We found the use of salvage surgery increased with intensive follow‐up for colorectal cancer (RR 1.98, 95% CI 1.53 to 2.56). The CIs included a range of clinically significant increases in salvage surgery. We found some non‐significant evidence of heterogeneity: I² = 31%; P = 0.14.

The funnel plot did not show evidence of small‐study effect (see Figure 5).

In absolute terms, the effect of intensive follow‐up on salvage surgery was 60 more episodes of salvage surgery per 1000 participants, but the true effect could lie between 33 to 96 more episodes per 1000 participants. The GRADE assessment of evidence quality for this outcome was high.

Sensitivity analyses

Our findings for the outcome of salvage surgery were robust to the following sensitivity analyses.

Excluding studies at high risk of bias for this outcome (Pietra 1998; Schoemaker 1998; Wang 2009), we found some non‐significant heterogeneity (RR 2.03, 95% CI 1.53 to 2.69; I² = 33%; P = 0.15).

With regard to study age we found that when we excluded the older studies (GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Ohlsson 1995; Pietra 1998; Schoemaker 1998; Treasure 2014), there was less heterogeneity (RR 2.04, 95% CI 1.35 to 3.09; I² = 25%; P = 0.25).

2.4 Interval (symptomatic) recurrences

We found 376 interval recurrences reported in 3933 participants enrolled in seven studies, with a median follow‐up duration of greater than 48 months for 100% of participants studied (FACS 2014; GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995; Secco 2002; Sobhani 2008; Wang 2009; Analysis 1.5). There was an appreciable decrease in the number of interval recurrences (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.86). The CIs included a range of clinically significant decreases in interval recurrences (Analysis 1.5). We detected heterogeneity: I² = 66%; P = 0.007.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intensive follow‐up versus minimalist follow‐up, Outcome 5 Interval recurrences.

Intensive follow‐up was associated with fewer interval recurrences: 52 fewer per 1000 participants; the true effect is between 18 and 75 fewer per 1000 participants. The GRADE assessment of quality of evidence was moderate, we downgraded once for risk of bias.

Sensitivity analyses

Our findings were robust to the following sensitivity analyses.

Excluding studies at high risk of bias for this outcome (Kjeldsen 1997; Wang 2009), we found evidence of heterogeneity (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.02; I²= 75%; P = 0.003).

With regard to study age (excluding GILDA 1998; Kjeldsen 1997; Mäkelä 1995), we found no evidence of heterogeneity (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.56; I² = 0%; P = 0.81).

2.5 Quality of life

CEAwatch 2015 found no significant differences between the two groups in terms of attitude to follow‐up, fear of recurrence, HADS score and Cancer Worry score, and there was no detectable burden or improvement in psychological burden associated with intensification of follow‐up.

GILDA 1998 found no clinically significant differences among the three main quality‐of‐life scales (SF‐12 mental component, SF‐12 physical component, and PGWB Index) between the two study arms.

Kjeldsen 1997 reported the influence of different follow‐up strategies on quality of life for 350 out of 597 Danish participants. They reported a small increase in quality of life (P < 0.05), as measured by the Nottingham Health Profile, associated with more frequent follow‐up visits compared with virtually no follow‐up.

ONCOLINK reported no significant effect on quality of life for the main outcome measures. They reported significant effects in favour of GP‐led follow‐up for EORTC QLQ‐C30 for role functioning (P = 0.02), emotional functioning (P = 0.01), and pain (P = 0.01). They did not report any significant differences in global health status.

SurvivorCare 2013 reported that psychological distress was similar between the two groups (difference 0.2, 95% CI −2.5 to 2.9) with the prespecified clinically meaningful difference of 0.42 (figures from the text). DIfferences between unmet needs, information needs and health‐related quality of life were not clinically significant. The intervention group were more satisfied with their care, but the median scores were similar (see Characteristics of included studies).

Wattchow 2006 assessed depression and anxiety, quality of life, and participant satisfaction in a cohort of participants randomised to follow‐up of their colon cancer in different settings (see Included studies). They found that the study participants remained in the normal range for depression and anxiety with no difference between the two groups at either 12 months or 24 months. Study participants (in each arm) had reduced physical quality of life at baseline, which improved as the study progressed, but there were no significant differences between the two groups. There were no differences between the two groups on the participant satisfaction scale, and both groups reported high levels of satisfaction with their care.

More intensive follow‐up probably makes little or no difference to quality of life (moderate‐quality evidence). The data were not available in a form that allowed analysis.

2.6 Harms (colonoscopy complications)

Two studies reported adverse events associated with follow‐up (Schoemaker 1998; Wang 2009). Three perforations and four gastrointestinal haemorrhages (requiring transfusion) were reported from a total of 2292 (0.3%) colonoscopies. Data from Schoemaker 1998 were not available in a form that allowed analysis. Intensive follow‐up may increase the complications (perforation or haemorrhage) from colonoscopies (RR 7.30, 95% CI 0.75 to 70.69); one study, 326 participants) (Wang 2009) Analysis 1.6; Table 1). GRADE evidence quality was very low, downgraded for risk of bias related to lack of blinding, reporting bias and imprecision.

2.7 Costs of surveillance

ONCOLINK found the cost per participant for 24 months' follow‐up was GPB 9889 for surgeon‐led follow‐up and GBP 8233 for GP‐led follow‐up (P < 0.001 (figures from text)).

Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006 demonstrated that although the cost of intensive follow‐up was higher, when resectability of recurrences was considered, the cost per resectable recurrence was lower in the intensively followed group.

Secco 2002 provided risk‐adapted follow‐up based on prognostic factors prospectively identified, and the study authors commented that risk‐adapted follow‐up reduced costs for those with a better prognosis.

In Sobhani 2018 the intensive arm cost significantly more than the control arm (P < 0.0033 (figure from text)).

Strand 2011 found no difference in costs.

Costs were assessed in CEAwatch 2015, but have not yet been reported.

In summary, limited data suggests that the cost of more intensive follow‐up may be increased in comparison with less intense follow‐up, but the cost of surgery for resectable recurrence may be reduced. GRADE evidence quality was low, being downgraded for imprecision. The data were not available in a form that allowed analysis.

Discussion

The results of our review suggest that there is no overall survival benefit for intensifying the follow‐up of participants after curative surgery for colorectal cancer. The analyses did not show a significant difference in the incidence of recurrence between the participants in the intensively followed groups and the control groups. However, significantly more surgical procedures for recurrence were performed in the experimental arms of the studies. Recurrences in the more intensively followed groups may have been detected earlier allowing for effective salvage treatments, but this did not lead to better overall survival.

Each study follow‐up strategy combined a number of different components, including frequency of visits, type of clinical assessment, types and frequency of tests, and the setting in which follow‐up was conducted (see Table 2). No study compared the addition of one specific intervention, and the feasibility of comparing strategies with a variety of components and varying complexity becomes problematic. The use of liver imaging does not appear to be associated with improved survival. A specific variation across the studies was the intensity of follow‐up. For example, the follow‐up intensity in the intensively followed group in Ohlsson 1995 was similar to the intensity of follow‐up in the control groups of other studies in the review (Mäkelä 1995; Pietra 1998; Schoemaker 1998). Therefore, it was not possible to extract from these data a precise indication of the optimal combinations of frequency, type, and setting for follow‐up investigations for these participants. Our findings were robust to sensitivity analysis when excluding Ohlsson 1995.

1. Interventions in included studies.

| Study | More intensive follow‐up | Less intensive follow‐up |

| Studies comparing more visits and tests versus fewer visits and tests | ||

| CEAwatch 2015 | CEA 2‐monthly year 1‐3, then 3‐monthly year 4‐5 Clinic visits 12‐monthly year 1‐3 CT CAP 12 monthly for 3 years CXR and liver US annually year 1‐3 |

CEA 3‐6‐monthly year 1‐3, 12 monthly year 4‐5 Clinic visits 6‐monthly year 1‐3, 12 monthly year 4‐5 CXR and liver US 6‐monthly year 1‐3, 12‐monthly year 4‐5 |

| GILDA 1998 | Office visits at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 30, 36, 42, 48, and 60 months and history and clinical examination, FBC, CEA, and CA 19‐9 Colonoscopy and CXR at 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months Liver US at 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months For rectal participants, pelvic CT at 4, 12, 24, and 48 months |

Office visits at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 30, 42, 48, and 60 months, including history, examination, and CEA Colonoscopy at 12 and 48 months Liver US at 4 and 16 months Rectal cancer participants in addition had rectoscopy at 4 months, CXR at 12 months, and liver US at 8 and 16 months. A single pelvic CT was allowed if a radiation oncologist required it as baseline following adjuvant treatment |

| Kjeldsen 1997 | Clinic visits at 6, 12, 18, 30, 36, 48, 60, 120, 150, and 180 months after radical surgery Examinations included medical history, clinical examination, DRE, gynaecological examination, Haemoccult‐II test, colonoscopy, CXR, haemoglobin level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and liver enzymes | Clinic visits at 60, 120, and 180 months Examinations included medical history, clinical examination, DRE, gynaecological examination, Haemoccult‐II test, colonoscopy, CXR, haemoglobin level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and liver enzymes |

| Mäkelä 1995 | Participants with rectal or sigmoid cancers had flexible sigmoidoscopy with video imaging every 3 months, colonoscopy at 3 months (if it had not been done preoperation), then annually. Liver US and primary site at 6 months, then annually | Participants who had rectal and sigmoid cancers had rigid sigmoidoscopy and barium enema annually |

| Pietra 1998 | Clinic visits at 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 30, 36, 42, 48, 54, and 60 months, then annually thereafter. At each visit: clinical examination, US, CEA, and CXR. Annual CT liver and colonoscopy were performed |

Seen at 6 and 12 months, then annually. At each visit, clinical examination, CEA, and US were performed. They had annual CXR, yearly colonoscopy, and CT scan. |

| Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006 | History, examination, and bloods (including CEA), US/CT, CXR, and colonoscopy | history, examination, and bloods (including CEA) |

| Sobhani 2008 | PET performed at 9 and 15 months and conventional follow‐up | Conventional follow‐up |

| Sobhani 2018 | FDG PET/CT at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months pus conventional follow‐up | Conventional follow‐up: physical examination and laboratory tests (FBC, tumour markers) at 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30, 33, 36 months, liver US and CXR at 3, 9, 15, 21, 27, 33 months, CT CAP at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30 and 36 months, colonoscopy at 12 and 36 months |

| SurvivorCare 2013 | Nurse‐led survivorship care package:

|

Usual care defined as: "care according to the treating cancer centre or practitioner's usual practice" |

| Treasure 2014 | CEA rise triggered 'second‐look' surgery, with intention to remove any recurrence discovered | CEA rise did not trigger 'second‐look' surgery |

| Wang 2009 | Colonoscopy at each visit | Colonoscopy at 6 months, 30 months, and 60 months from randomisation |

| Studies comparing tests and visits with minimal or no follow‐up | ||

| COLOFOL 2018 | CEA 1 month postoperatively then CEA, CT chest and abdomen 6, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months | CEA 1 month postoperatively then CEA, CT chest and abdomen 12 and 36 months after surgery |

| FACS 2014 |

|

No scheduled follow‐up except a single CT scan of the CAP if requested at study entry by a clinician |

| Ohlsson 1995 | 3‐, 6‐, 9‐, 12‐, 15‐, 18‐, 21‐, 24‐, 30‐, 36‐, 42‐, 48‐, and 60‐month clinic visits. Performed at each visit were clinical exam, rigid proctosigmoidoscopy, CEA, alkaline phosphatase, gamma‐glutaryl transferase, faecal haemoglobin, and CXR. Examination of anastomosis (flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy, as dictated by the lesion) was performed at 9, 21, and 42 months. Colonoscopy was performed at 3, 15, 30, and 60 months. CT of the pelvis was performed at 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. | No planned follow‐up visits. Participants received written instructions recommending that they leave faecal samples with the district nurse for examination every third month during the first 2 years after surgery then once a year. They were instructed to contact the surgical department if they had any symptoms. |

| Schoemaker 1998 | Yearly CXR, CT of the liver, and colonoscopy | These investigations were only performed in the control group if indicated on clinical grounds or after screening test abnormality, and at 5 years of follow‐up, to exclude a reservoir of undetected recurrences |

| Secco 2002 | Clinic visits and serum CEA, abdomen/pelvic US scans, and CXR. Participants with rectal carcinoma had rigid sigmoidoscopy and CXR. | "minimal follow‐up programme performed by physicians" |

| Studies that assessed effect of setting for follow‐up | ||

| ONCOLINK | Surgeon‐led follow‐up Frequency of follow‐up equal |

GP‐led follow‐up Frequency of follow‐up equal |

| Strand 2011 | Surgeon‐led follow‐up | Nurse‐led follow‐up |

| Wattchow 2006 | Primary care setting and environment for follow‐up Follow‐up guidance was based on current clinical practice, and guidance was provided that suggested follow‐up visits every 3 months for the first 2 years postoperatively, then every 6 months for the next 3 years. Each visit incorporated asking a list of set questions about symptoms, physical examination, annual faecal occult blood testing, and colonoscopy every 3 years | Secondary care setting for follow‐up |

| CA 19‐9: cancer antigen 19‐9; CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen; CAP: chest, abdomen, pelvis; CT: computed tomography; CXR: chest X‐ray; DRE: digital rectal examination; FBC: full blood count; FDG: fluorodeoxyglucose; PET: positron emission tomography; US: ultrasound | ||

Most recurrences (about 90%) occur within the initial 36 months after initial therapy for colorectal cancer (Ryuk 2014), so to detect recurrences, follow‐up duration should be at least 36 months for colorectal cancer. Patients with rectal cancer should have longer follow‐up because liver and lung recurrences may be delayed. The use of adjuvant chemotherapy may further delay recurrence (Sadahiro 2003). For the outcomes included in this study, median follow‐up duration was greater than 48 months for more than 90% of the participants studied.

We presented substantially altered conclusions in the 2016 update of the review (Jeffery 2016). Where we previously reported that "there was evidence that an overall survival benefit at five years exists for patients undergoing more intensive follow up", Jeffery 2016 did not confirm these findings. The four new studies included in this updated version of the review (CEAwatch 2015; COLOFOL 2018; Sobhani 2018; SurvivorCare 2013), with an additional 6238 participants, reinforced our findings in Jeffery 2016 that there is no overall survival benefit for intensifying the follow‐up of patients after curative surgery for colorectal cancer.

Summary of main results

Overall survival: the use of intensive versus less intensive follow‐up makes little or no difference after curative treatment (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.04; Analysis 1.1).

Colorectal cancer‐specific survival: the use of intensive versus less intensive follow‐up makes little or no difference after curative treatment (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.07; Analysis 1.2).

Relapse‐free survival: intensive versus less intensive follow‐up makes little or no difference after curative treatment (HR 1.05, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.21; Analysis 1.3).

The use of salvage surgery was increased with intensive follow‐up after curative treatment for colorectal cancer (RR 1.98, 95% CI 1.53 to 2.56; Analysis 1.4).

Interval (symptomatic) recurrences were probably slightly reduced with intensive follow‐up after curative treatment for colorectal cancer (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.86; Analysis 1.5).

Quality of life

CEAwatch 2015 found no significant differences between the two groups in terms of attitude to follow‐up, fear of recurrence, HADS score and Cancer Worry score, and there was no detectable burden or improvement in psychological burden associated with intensification of follow‐up. GILDA 1998 found no clinically significant differences among the three main quality‐of‐life scales (SF‐12 mental component, SF‐12 physical component, and PGWB Index) between the two study arms. Kjeldsen 1997 reported a small increase in quality of life associated with more frequent follow‐up visits compared with virtually no follow‐up. ONCOLINK reported no significant effect on quality of life main outcome measures: for EORTC QLQ‐C30, they reported significant effects in favour of GP‐led follow‐up for pain, role functioning, and emotional functioning; they reported no differences in global health status, with intensive follow‐up compared with less intense follow‐up. SurvivorCare 2013 found no clinically meaningful differences in psychological distress, unmet needs, information needs and health‐related quality of life. Wattchow 2006 found that the study participants remained in the normal range for depression and anxiety with no difference between the two groups at either 12 or 24 months.

Harms and costs of surveillance (including investigations)

The studies reported three bowel perforations and four gastrointestinal haemorrhages (requiring transfusion) from a total of 2292 (0.3%) colonoscopies (Schoemaker 1998; Wang 2009).

ONCOLINK found the cost per participant for 24 months' follow‐up was GBP 9889 for surgeon‐led follow‐up and GBP 8233 for GP‐led follow‐up (P < 0.001 (figures from text)). Rodríguez‐Moranta 2006 demonstrated that although the cost of intensive follow‐up was higher, when they considered resectability of recurrences, the cost per resectable recurrence was lower in the intensively followed group. Secco 2002 reported that risk‐adapted follow‐up reduced costs for those with a better prognosis. Strand 2011 showed no difference in costs.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The evidence we report is directly relevant to the study question.