Based primarily on cellular data (1) and community-based epidemiological studies (2) showing an association of low magnesium (Mg) levels with malignant arrhythmias and mortality, guidelines recommend Mg supplementation to maintain levels >2.0 mg/dL during acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (3), despite lack of supporting data from >26 randomized trials of routine Mg supplementation (4). We used the Cerner Health Facts® database, a national database of patients hospitalized with AMI, to determine the association of Mg levels with in-hospital mortality and malignant cardiac arrhythmias.

METHODS

Eligible patients were hospitalized 2005–2015 with a clinically relevant AMI, defined as 1) principal discharge diagnosis of AMI and cardiac biomarkers >3× ULN within 48 hours of admission, or 2) secondary discharge diagnosis of AMI and cardiac biomarkers >10× ULN within 48 hours of admission. All data were extracted de-identified from electronic health records. Laboratory data were time-stamped. As this dataset represents real-world care, local providers dictated all laboratory draws, electrolyte supplementation, and other aspects of clinical care.

Hierarchical Cox regression evaluated the association of most recent Mg level (as a time-varying covariate) with in-hospital mortality. As a secondary analysis, logistic regression examined the association of admission Mg level with in-hospital malignant arrhythmia (ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation or cardiac arrest). As arrhythmias were not time-stamped (only noted on discharge diagnoses), we could not analyze Mg levels as a time-varying covariate. Both models adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking, alcohol abuse, diabetes, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, kidney disease, liver disease, and admission potassium, creatinine, and hematocrit. Hospital site was included as a random effect to account for clustering of patients within sites.

The UMKC IRB determined this as non-human subjects research, and a waiver of informed consent was granted. Analyses were conducted with SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R v3.2.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

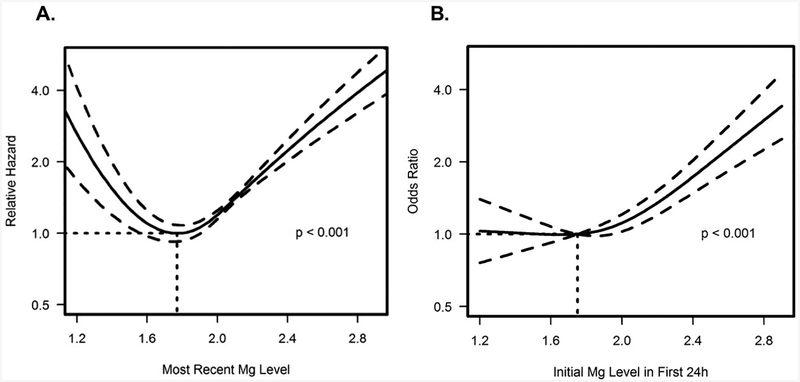

Among 10,806 patients hospitalized at 77 US hospitals with a clinically-relevant AMI, median age was 66 years, 61% male, and 81% white. Median length of stay was 3.1 (IQR 2.1–5.8) days. 63% had at least 1 Mg level checked with median admission Mg 1.9mg/dL (IQR 1.8–2.1). Patients who presented with low Mg were more likely to be female and have diabetes and heart failure. Patients with admission Mg <1.8mg/dL, 1.8mg/dL, 1.9–2.0mg/dL, and >2mg/dL had in-hospital mortality rates of 7.4% vs. 4.1% vs. 4.7% vs. 9.7%, respectively (unadjusted p<0.001). After adjusting for patient factors, there continued to be a U-shaped relationship between most recent Mg level and mortality (Figure 1A), with the lowest hazard of death at most recent Mg level ~1.8 mg/dL. A similar relationship was evident between admission Mg level and odds of malignant arrhythmia (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1.

A-Adjusted Association of Most Recent Mg Level with In-Hospital Mortality.

Model accounted for demographic and clinical factors, #Mg checks during hospitalization, and Mg as a time-varying covariate.

B-Adjusted Association of Admission Mg Level with In-Hospital Malignant Arrhythmia.

DISCUSSION

Previously conducted large multicenter trials found no benefit of routine intravenous Mg supplementation in AMI (1); however these studies did not specifically assess the relationship of Mg levels and in-hospital outcomes. In a retrospective multi-center study of >10,000 patients with AMI, we found that serum Mg levels were associated with in-hospital mortality and malignant arrhythmias in a U-shaped manner, with the lowest risk of adverse events at serum Mg levels ~1.7 to 1.9 mg/dL. While our results confirm risk associated with hypomagnesemia, they also demonstrate increased risk with higher Mg levels and suggest that the optimal range of Mg in patients with AMI may be lower than what is currently recommended by AMI guidelines. Importantly, these results represent associations and therefore cannot explicitly define a specific safe Mg level; however, they do suggest that aggressive supplementation may not be necessary (or safe) for Mg levels slightly lower than 2.0 mg/dL.

FUNDING SOURCE:

AS and MQ: supported by a T32 grant from the NHLBI (T32HL110837).

ABBREVIATIONS

- AMI

acute myocardial infarction

- Mg

magnesium

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES: MK: Research grants from AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences, Genentech and Sanofi; other research support from AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences, Amgen and ZS Pharma; consulting honoraria from AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Eli Lilly, GSK, Boehringer Ingelheim, Takeda, Merck (Diabetes), Novo Nordisk, Glytec and ZS Pharma; speakers bureau for Amgen. AG: advisory board honorarium from ZS Pharma. The other authors report no relevant conflicts.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Agus ZS. Hypomagnesemia. J Am Soc Nephrol 1999;10:1616–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford ES. Serum magnesium and ischaemic heart disease: findings from a national sample of US adults. Int J Epidemiol 1999;28:645–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction--executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation 2004;110:588–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li J, Zhang Q, Zhang M, Egger M. Intravenous magnesium for acute myocardial infarction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007:CD002755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]