Abstract

Memory and the self have long been considered intertwined, leading to the assumption that without memory, there can be no self. This line of reasoning has led to the misconception that a loss of memory in dementia necessarily results in a diminished sense of self. Here, we challenge this assumption by considering discrete facets of self-referential memory, and their relative profiles of loss and sparing, across three neurodegenerative disorders: Alzheimer’s disease, semantic dementia, and frontotemporal dementia. By exploring canonical expressions of the self across past, present, and future contexts in dementia, relative to healthy ageing, we reconcile previous accounts of loss of self in dementia, and propose a new framework for understanding and managing everyday functioning and behaviour. Notably, our approach highlights the multifaceted and dynamic nature in which the temporally-extended self is likely to change in healthy and pathological ageing, with important ramifications for development of person-centred care. Collectively, we aim to promote a cohesive sense of self in dementia across past, present, and future contexts, by demonstrating how, ultimately, ‘All is not lost’.

Keywords: autobiographical memory, personal semantics, future thinking, Alzheimer’s disease, semantic dementia, frontotemporal dementia

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

“Memory alone... ‘tis to be considered... as the source of personal identity”

Memory and the self have long been considered intertwined (Locke, 1690; Squire and Kandel, 2003). The accumulation of memories from meaningful life experiences naturally gives rise to a ‘sense of self, or a feeling that we exist as a distinct and unique person (Prebble et al., 2013). A sense of continuity of who we are (and will be) as individuals (i.e., ‘self-continuity’) endures across time despite life’s many vagaries and ever-changing circumstances, enabling reflection upon one’s past, as well as anticipation of the future. Exploration of the interplay between memory and the self, however, has been hindered by the ephemeral nature of the “self’, and the tendency to consider episodic and semantic contributions to the self as independent, uniform, and static (see Haslam et al., 2011; Prebble et al., 2013). Recent theoretical refinements have sought to delineate how episodic and semantic elements of memory potentially interact to support continuity of the self across past, present, and future contexts (Addis and Tippett, 2008; Haslam et al., 2011; Prebble et al., 2013). Here, we build upon such integrative frameworks to consider how disruptions to discrete facets of memory impact an individual’s sense of self, largely in the context of pathological ageing (Section 1), and how such alterations potentially differ contingent on temporal context, including past (Section 2), future (Section 3), and present (Section 4) . In doing so, we demonstrate that loss of memory does not in fact translate to a complete loss of self.

1.1. The self as a temporally-extended system

Humans are inherently driven to view their sense of self as continuous across time, enabling one to experience both stability and growth in who one is as a person (Locke, 1690; Ricoeur et al., 1990). Maintaining such a continuous sense of self is typically couched with reference to episodic (event-based) memory; however, it is important to also recognise the contribution of semantic memory (conceptual knowledge) in supporting self-continuity overtime. In addition, considerable interdependence exists between the episodic and semantic memory systems (Burianová and Grady, 2007; Greenberg and Verfaellie, 2010), irrespective of whether an individual recollects a highly detailed autobiographical memory from the past or projects forward in time to envisage a self-referential future event (Irish, 2016; Irish and Piguet, 2013). As such, both episodic and semantic memory are proposed to support self-continuity across temporal contexts, in ways that are complex and distinct (Prebble et al., 2013). Episodic memory is posited to confer a sense of subjective continuity of the self, that is, the ability to mentally project to the past or future to autonoetically re-experience (or ‘pre-experience’) episodes (Tulving, 1972; Wheeler et al., 1997). This gives rise to a sense that the present self is an extension of who one was (or will be) at the time of the event, allowing a sense of agency (Metcalfe et al., 2012), aiding in future decision making and goal-setting (Hershfield, 2011), contributing to growth of the self over time (D’Argembeau et al., 2012), and benefiting social relationships (Alea and Bluck, 2003). On the other hand, semantic memory is held to underlie the objective, narrative continuity of the self, experienced via ‘noetic’ consciousness (Tulving, 1972), allowing for the creation of a meaningful life story connecting past, present, and future selves. Personal facts and experiences may be weaved together via common themes, providing a narrative which one can retell, update, and create new meaning from (McAdams, 2001). Both forms of self-continuity, therefore, crucially contribute to an individual’s functioning and wellbeing (Rathbone et al., 2015; Vanderveren et al., 2017).

1.2. Does loss of memory entail a loss of self?

The proposed centrality of memory for a sense of self (Locke, 1690) has led to the assumption that without memory, such as in amnestic disorders, there can be no “self’ (Buñuel, 2011; Squire and Kandel, 2003; Tulving, 1983). By this view, an amnesic individual is effectively stripped of their personhood and moral agency, raising grave ethical questions regarding their autonomy and capacity to make personal decisions. Here, we build on recent arguments cautioning against the simplistic notion that memory impairments lead to a loss of self (e.g., Craver, 2012). Two of the most famous amnesic case studies, H.M. and K.C., both retained some semblance of self-continuity via preserved knowledge about themselves (for example, where they grew up, personality traits, and preferences), in the face of marked retrograde and anterograde impairments (Hilts, 1995; Tulving, 1993). Such examples suggest that aspects of self-continuity persist even in the face of gross episodic memory impairment, and caution against viewing the self as a monolithic entity. A similar erroneous view has been applied in relation to neurodegenerative disorders, characterised by profound episodic and semantic memory loss. Such conditions have been described as causing a “loss” (Downs, 1997), “disintegration” (Davis, 2004), or “unbecoming” (Fontana and Smith, 1989) of the self. Despite emergent evidence to the contrary (Baird, 2019; Caddell and Clare, 2010; Hampson and Morris, 2016; Kitwood, 1989; Tippett et al., 2018), conceptualisations of the self as entirely compromised in dementia continue to persist (as noted by Feast et al., 2016). Viewing the self as completely diminished in dementia can have potentially damaging effects on the wellbeing of these individuals and their loved ones, resulting in the exacerbation of behavioural problems and breakdowns in relationships (Feast et al., 2016). Here, however, we review evidence which suggests that despite the severe memory disturbances in dementia, self-continuity remains present to varying degrees across past and future contexts.

1.3. The importance of studying the self in dementia

Neurodegenerative disorders with distinct profiles of memory impairment offer a unique opportunity to examine the complex interplay of episodic and semantic contributions to self-continuity. The contrasting conditions of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), characterised by stark episodic memory loss, and semantic dementia (SD), in which the semantic knowledge base is progressively eroded, permit us to study how changes in episodic and semantic memory, respectively, impinge upon the self. In addition, unique insights may be gleaned from the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), a form of younger-onset dementia characterised by marked personality and behavioural change. This syndrome provides a compelling window into the unravelling of the self, manifesting in alterations in defining characteristics of the person, such as preferences, values, and traits, combined with a pervasive lack of self-awareness and insight into these changes (see Wong et al., 2018b). Interestingly, while episodic and semantic memory are also affected in bvFTD, these appear to be secondary to the stark changes in the self, and resultant impairment of processing self-related information (Irish et al., 2012c; Wong et al., 2017). As such, these three contrasting syndromes can provide distinct insights into episodic and semantic contributions to continuity of the self.

Empirical studies of how episodic and semantic memory impairments deleteriously affect self-continuity in dementia have thus far been scarce (see Caddell and Clare, 2010). Of the limited studies to date, one approach has involved measurement of the self independently from episodic and/or semantic memory, with the relationship between the two subsequently explored (e.g., Addis and Tippett, 2004). Reliable assessment of the abstract construct of the ‘self’ in populations characterised by widespread cognitive dysfunction, however, is inherently challenging (Caddell and Clare, 2010). Measures of ‘self-experience’ typically employed across other populations (e.g., Twenty Statements Test, Kuhn and McPartland, 1954; Tennessee Self-Concept Scale, Fitts and Warren, 1996; Self-Consciousness Scale, Scheier and Carver, 1985; Self-Persistence Interview, Chandler et al., 2003) are heavily reliant on self-reflection and insight: abilities commonly affected from early in the disease course of many neurodegenerative disorders. Given this limitation, the bulk of current evidence for altered self-continuity in dementia stems from studies of episodic and semantic processes on their own. Here, we consider how metrics such as specificity, contextual detail, and the subjective phenomenological experience (e.g., self-reported re-experiencing, visual perspective, and emotional valence of retrieved memories) potentially inform our understanding of the component processes underlying subjective and narrative self-continuity. Importantly, we further draw upon convergent evidence about patient behaviour and functioning as evidence of observable changes in the self, including the individual’s actions, preferences, and interactions. Collectively, these findings reveal how distinct alterations in continuity of the self manifest across different neurodegenerative disorders dependent on temporal context and the nature of memory dysfunction.

2. “I was”- Remembering the past

Often considered the prototypical expression of the self, autobiographical memory (ABM) involves the recollection of personally-defining past memories imbued with rich sensory-perceptual details, emotional connotations, as well as abstracted semantic knowledge not specific to time or place (Greenberg and Verfaellie, 2010; Grilli and Verfaellie, 2014; Irish and Piguet, 2013; Renoult et al., 2012). Disruption to ABM is a pervasive feature across a host of dementia syndromes (e.g., Irish et al., 2011a), with significant impacts on interpersonal relationships (Kumfor et al., 2016).

The majority of studies of ABM have focused on its episodic component (see Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2018), in recognition of its proposed importance for subjective continuity of the self (Prebble et al., 2013). Traditionally, episodic ABM was quantified by the specificity of a recollected past, personal event (e.g., Autobiographical Memory Interview, AMI, Kopelman et al., 1989; TEMPau, Piolino et al., 2000), though scores on these tasks are constrained by the limited range of the scoring system. An increasing focus on contextual details as a marker of re-experiencing has led to the use of uncapped scoring systems (e.g., ‘internal’ details on the Autobiographical Interview, AI, Levine et al., 2002), with individuals credited for the total amount of episodic content generated. Contextual details, however, are not the sole criterion for the subjective feeling of autonoetic reliving (Piolino, 2003; Irish et al., 2008), prompting a shift towards examining phenomenological aspects of the recollective endeavour (e.g., Irish et al., 2011b). As such, to better appreciate how subjective self-continuity is altered across neurodegenerative disorders, assessments of episodic ABM must consider the subjective phenomenological experience along with event specificity and level of contextual detail.

2.1. Contributions of episodic ABM disruption to self-continuity in dementia syndromes

2.1.1 Alzheimer’s disease (AD)

Early studies in AD using the AMI highlighted a temporal gradient of event recall, with impaired retrieval of recent events in the context of relatively intact remote recall (Greene et al., 1995; Irish et al., 2006), in accordance with Ribot’s Law (Ribot, 1881). Using the uncapped scoring system of the AI, however, a flat profile of episodic ABM impairment is evident, with global disruption of the memory trace across all life epochs (Barnabe et al., 2012; Irish et al., 2011a; 2014). Loss of episodic content occurs in parallel with marked alterations in the phenomenological experience of remembering. As such, AD more than other dementia syndromes provides compelling insight into the critical contribution of episodic ABM to subjective self-continuity. These individuals no longer mentally relive their past memories, instead reporting that they simply “know” the events to have taken place (Piolino, 2003; Souchay and Moulin, 2009). More tellingly, autonoetic re-experiencing is grossly compromised in AD (Irish et al., 2011b; Piolino, 2003), manifesting in narratives that are divested of first-person self-referential imagery and emotional salience (Irish et al., 2011b). Memories of formerly evocative events such as one’s wedding day, birth of a child, or death of a parent, are largely reduced to semanticised abstracted accounts, divorced of a sense of having lived through the defining event. Maintaining a sense of subjective self-continuity is posited to serve important social functions, with the painting of a detailed picture of a previously experienced event to another person thought to promote bonding, trust, and empathy (Mahr and Csibra, 2017). It is surprising, then, that social comportments and interactions remain generally preserved in AD, at least in the early stages (Zhang et al., 2015), in the face of starkly impaired subjective self-continuity for the past. As we argue in later sections, other, preserved elements of self-referential memory may in fact be preferentially drawn upon in AD to support social exchanges when subjective elements are no longer available (see also Hayes et al., 2018, for discussion of the importance of semantic memory in social interactions).

2.1.2. Semantic dementia (SD)

While SD primarily involves the progressive degeneration of the conceptual knowledge base, studying this group nonetheless provides insights into the contribution of episodic ABM to self-continuity. In contrast to AD, recent episodic retrieval appears relatively spared in SD, with these patients typically displaying detailed recollection of recent episodes (Graham and Hodges, 1997; Hou et al., 2005; Irish et al., 2011a) for which they report a preserved sense of mental reliving (Remember/Know paradigm; Piolino, 2003; Piolino et al., 2003). Contrarily, memory for remote episodes is largely impoverished in detail (Graham and Hodges, 1997; Hou et al., 2005; Irish et al., 2011a), interpreted as reflecting the semanticisation of older episodic memories with age. While patients report autonoetically re-experiencing these remote events, the validity of such accounts is questionable given they are unable to adequately justify this sense of remembering (Piolino, 2003; Piolino et al., 2003a). As such, a degree of subjective self-continuity for the recent past appears retained in SD, though this is likely limited to a narrow temporal window (i.e., the past year). Intriguingly, this temporal tapering of the self may help to explain the commonly reported rigid and stereotypical behaviours in this condition (Ahmed et al., 2014; Perry et al., 2001; Rosen et al., 2006). Patients with SD often develop a strong preference for routine, such as wearing the same clothes, or insisting on attending the same cafe, and having the same lunch, at the same time, every day. The ability to mentally re-experience the self exclusively within the recent past in SD may therefore lead to an over-reliance on recent events to guide behaviour, and potentially even, to define the self.

2.1.3. Behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD)

Notably, while episodic memory impairments are not typically considered a core diagnostic feature of bvFTD (Rascovsky et al., 2011), mounting evidence reveals gross alterations in self-referential retrieval in this syndrome (Wong et al., 2017). Impairments in episodic ABM are evident across all lifetime periods in bvFTD (Irish et al., 2011a; 2014; Matuszewski et al., 2006; Thomas-Anterion et al., 2000), combined with reduced autonoetic (Bastin et al., 2011; Piolino, 2003) and egocentric (Piolino et al., 2007) reliving. As such, while this syndrome is primarily characterised by marked personality and behavioural changes, it evolves to impact ABM, with the initial breakdown in the self likely impairing subsequent retrieval of self-related information (Irish et al., 2012c). At first glance, the gross impairments in episodic ABM in both AD and bvFTD would suggest comparable disruption to subjective self-continuity for the past. Critically, however, at a functional level, such deficits play out in markedly different ways. Unlike in AD, bvFTD patients undergo prominent deterioration in their social functioning, including the breakdown of meaningful relationships (Hsieh et al., 2013). While this is at least somewhat attributable to early symptoms such as challenging behaviours and reduced empathy, the altered subjective self-continuity in bvFTD likely exacerbates such social dysfunction. Limited access to detailed personal events from their past may contribute to the reduced initiation and impoverished content of conversations in these patients, further impeding the bonding experience with close others.

2.2. Contributions of semantic ABM

While episodic expressions of ABM have received the most attention in relation to the self, the semantic component of ABM is also integral to self-continuity, by providing an ‘objective’ store of all that is known about the self (Klein et al., 2002). These semantic elements, rather than the events from which they are abstracted, provide a sense of narrative continuity across time (Thomsen, 2009), which can be drawn upon when episodic elements are lacking (e.g., Grilli and Verfaellie, 2015; Rathbone et al., 2009). Accordingly, even in the absence of autonoetic reliving, semantic memory may provide a sense of self-continuity across time, by creating a personal life story encompassing facts about oneself and abstractions of one’s experiences (Prebble et al., 2013; Tippett et al., 2018). For example, such a narrative could incorporate that one grew up in the UK, moved to Australia, has three children, and enjoys classical music. Recent theoretical updates, however, contend that semantic ABM is not necessarily a unitary entity, but rather comprises subcomponents which vary in their relative episodicity or semanticity (Grilli and Verfaellie, 2014; Renoult et al., 2012; Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2018). Highly abstracted personal trait knowledge and autobiographical facts (‘personal semantics’) are considered separable from ‘general event’ memories (i.e., repeated or extended episodes), which lie at the intersection of episodic and semantic ABM (Figure 1). Each of these discrete elements of semantic memory impart important contributions to narrative continuity of the self (Prebble et al., 2013).

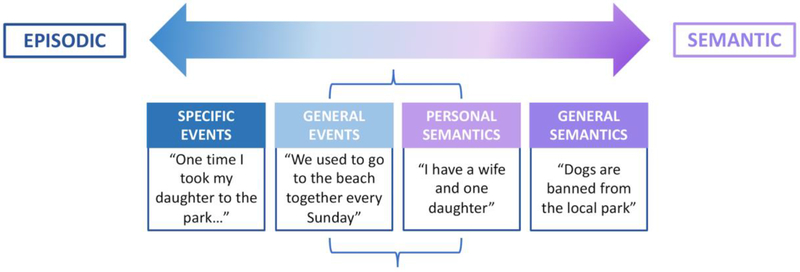

Figure 1:

The episodic-semantic-continuum of ABM. General events (i.e., repeated or extended episodes) and personal semantics (i.e., trait knowledge and autobiographical facts) lie at the intersection of episodic and semantic ABM (represented by brackets), and may draw upon either, or both, memory systems for their retrieval.

2.2.1. Alzheimer’s disease (AD)

Direct probing of personal semantic information (e.g., asking where one went to school, whether they are a kind person) reveals impaired retrieval of autobiographical facts in AD (e.g., Barnabe et al., 2012; Graham and Hodges, 1997; Irish et al., 2006; 2011b), in the context of relatively preserved personal trait knowledge (Addis and Tippett, 2004; Eustache et al., 2013; Klein et al., 2003; Rankin et al., 2005; Ruby et al., 2009). Temporal gradients are evident for both types of personal semantics in AD, such that self-knowledge about the recent past may be particularly impaired, including facts about the self (e.g., having new grandchildren; Kazui et al., 2000), or changes in personality traits occurring since the onset of the disease (e.g., becoming less self-assured; Hehman et al., 2005; Klein et al., 2003; Mograbi et al., 2009). Nonetheless, knowledge about the self from the distant past, such as the location of their childhood home, the university they attended, and their premorbid personality, remains relatively resilient in AD (e.g., Hou et al., 2005; Rankin et al., 2005). Indeed, the spontaneous narratives of AD patients are commonly observed to reflect remote personal semantics that remain accessible in mild to moderate stages of the disease (e.g., Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2018). Taken together, these findings suggest that while AD patients retain some access to the semantic elements required to provide narrative continuity for much of their personal life history, their sense of self is largely anchored on the remote past (i.e., childhood & early adulthood periods, see Addis and Tippett, 2004; Tippett et at., 2018).

Intriguingly, the relative preservation of remote personal semantics in AD results in a mismatch between the period of life they believe they are in, and objective reality. For example, AD patients may rate their current age as younger than they actually are (Eustache et al., 2013) with some individuals expressing shock or surprise when confronted by their reflection. With the progressive erosion of the recent personal narrative, AD patients increasingly default to older, intact, semantic memories with no updating or change in their life story over time (see Grilli et al., 2018, for similar findings in amnesia). Behavioural observations of patients returning to previous life roles (e.g., a former doctor continuing to write reports) or mistaking family members (e.g., looking for their young children) (Harrison et al., 2005) provide compelling illustrations of how the self is not lost in AD per se. Rather, the individual reverts to an older iteration of the self that is incongruent with their present experience and surroundings. These observations in AD relate to the proposal that personal semantics are organized into higher-order categories of knowledge culminating in an active schema of the self (Markus, 1977). From this perspective, similar to schemas of world or shared knowledge, one’s self-schema may operate as a dynamic, heuristically-driven template that facilitates fast decisions regarding “who I am”, “what I do”, and “how I behave” – rules that govern our day-to-day activities (Sheeran and Orbell, 2000). Also aligning with the properties of other schemas, one’s self-schema may be adaptable, and updated as dictated by changing physical contexts, experiences, and social relationships (Markus, 1977). AD patients, therefore, may deploy an out-of-date self-schema, in that “who I was” becomes “who I am”, and this non-updated framework governs their everyday behaviour.

2.2.2. Semantic dementia (SD)

Unsurprisingly, the gross semantic impairments in SD extend to the retrieval of autobiographical facts (e.g., where they went to school), resulting in a reverse temporal gradient, such that recent facts are better preserved than those from the remote past (Graham and Hodges, 1997; Hou et al., 2005; Nestor et al., 2002). Similarly, on a more open-ended task of personal knowledge (the ‘3 I test’), SD patients produce an equivalent number of semantic representations of the present self, compared with healthy controls, but descriptions of the past self are impoverished (Duval et al., 2012). Collectively, findings to date suggest some degree of preservation of ‘personal semantic’ memory in SD, particularly for the recent past and present time periods. So-called ‘facts’, however, may more accurately reflect retrieval of recent events (e.g., remembering the conversation in which they were told a new grandchild’s name), and therefore draw upon the episodic, rather than semantic memory system (Graham et al.,1997; Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2018). Nonetheless, these memories likely touch on activities, people, or places that can connect the recent past to the present at a factual level. Preservation of recent episodes may support a degree of narrative continuity in SD particularly in relation to the current self, a proposal that meshes well with reports of relatively preserved self-awareness in SD (Savage et al., 2015). This recent episodic information may also override previously established, vulnerable elements of the self-schema in SD, resulting in behaviour that is largely guided by the recent self. We speculate that this retention of recent self-defining information in SD may confer some functional benefit in this condition, by augmenting a connection to current reality. It is interesting therefore that this syndrome displays lower rates of disability (Mioshi et al., 2007), and improved survival rates (Hodges et al., 2010), compared with other neurodegenerative disorders.

2.2.3. Behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD)

Findings on personal semantic memory in bvFTD are more equivocal, spanning from preserved retrieval of autobiographical facts across the lifespan (Hou et al., 2005; Nestor et al., 2002) to global impairments irrespective of time period (Thomas-Anterion et al., 2000). More intriguingly, despite the marked personality changes that are characteristic of this syndrome, such as inappropriate behaviour, disinhibition, and impulsivity, bvFTD patients fail to update their self-knowledge to incorporate these alterations in personal traits (Rankin et al., 2005; Ruby et al., 2007). This profound lack of insight extends to other personal attributes such as preferences, values, sense of humour, political affiliation, and morality, all of which undergo dramatic changes (Piguet et al., 2011). The bvFTD syndrome thus presents something of a paradox whereby the individual is viewed as a ‘different person’ by close others (Strohminger and Nichols, 2015), with no corresponding change in the patient’s own perceived ‘self’. In the absence of an accurate self-schema or self-governing framework, bvFTD results in behaviour that is considered extremely jarring to close others, and at odds with the individual’s premorbid personality. Furthermore, the striking impairment of self-awareness, and resultant effects of their behaviour on loved ones, leads to significant carer burden and distress (Diehl-Schmid et al., 2013; Hsieh et al., 2013). Interestingly, however, this lack of insight has a somewhat protective effect for the mental wellbeing of patients, who rarely present with mood disturbances (Bozeat et al., 2000). These findings further highlight the complexity of the relationship between memory and the self in dementia and its subsequent manifestations in patients’ daily lives.

2.3. General event memories (“I used to”)

General event memories, of episodes repeated a number of times (e.g., “I used to go dancing every Friday”), or spanning an extended time period (e.g., “I worked in the city for a few years”), also impart a significant contribution to narrative continuity (Conway and Pleydell-Pearce, 2000). Such events lie at the centre of the episodic-semantic continuum (Renoult et al., and may draw upon either memory system during retrieval (Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2018; Figure 1), dependent on the accessibility of the information (Irish, in press). Studies of general event memory in dementia typically examine the specificity of recollected personal episodes (e.g., on the AMI; Kopelman et al., 1989), with the provision of more general, abstract events interpreted as impaired episodic, but preserved semantic, ABM. General event memory is typically found to be preserved in AD (Irish et al., 2011b; Philippi et al., 2015), potentially reflecting a compensatory strategy by which intact memories of repeated events are harnessed to support a self-narrative. For example, an individual with AD can recall that they went dancing every Friday, despite being unable to provide a contextually rich description of one particular instance. Such overgeneral events may provide some semblance of self-narrative in AD, albeit bound to memories that are temporally distant from the present day. SD patients, by contrast, provide reduced semanticised recollections of past events (Duval et al., 2012), though unlike in AD, their retained subjective self-continuity for the recent past may instead be preferentially drawn upon to support the self. No such compensatory process occurs in bvFTD, though, with memory for general events reduced to an equal degree as detailed episodic ABM (Thomas-Anterion et al., 2000). We speculate that such global changes in both subjective and narrative self-continuity for the past in bvFTD may contribute to the greater functional disability seen in bvFTD compared to other dementia syndromes (Mioshi et al., 2007). By this view, preservation of certain elements of ABM in AD and SD may serve to maintain a degree of self-continuity even in the face of stark memory loss, whereas the global disruptions in self-referential retrieval in bvFTD equate to a much more profound disruption of the self.

2.4. New approaches to understanding the past self

The aforementioned studies have typically dissected episodic from semantic components of ABM, treating these constructs as dissociable entities. This tendency to fractionate episodic and semantic memory, however, fails to embrace the many ways in which the two memory systems interact during ABM retrieval (e.g., Greenberg and Verfaellie, 2010; Irish and Piguet, 2013). In addition, intact recall of semantic facts alone is not sufficient to provide a sense of self-continuity, which instead requires integration of this information into a coherent narrative (McAdams, 2001). A more sensitive and ecologically valid window into narrative continuity, therefore, can be gained by examining the semantic details enmeshed within autobiographical narratives, as these details typically situate the event within the broader context of the individual’s life story. We recently proposed a new taxonomy for the fine-grained examination of ‘external’ details in episodic narratives, that is, the additional information provided during recall that is not specific to the main event being described (Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2018). While external details have long been overlooked in the ABM literature, we argue that this contextual, background information is integral to one’s life story. Our new protocol, the New External Details (NExt) taxonomy, reveals distinct profiles of personally-relevant information across the episodic-semantic spectrum in AD and SD, obscured using traditional scoring methods (e.g., Barnabe et al., 2012; Benjamin et al., 2015; Irish et al., 2011a; 2018). Specifically, AD patients default to providing general events (‘extended episodes’), personal semantic, and general semantic details in the face of impoverished episodic (‘internal’) retrieval, particularly for the remote period (Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2018). Such findings dovetail with the increased reliance on gist-based memory in AD (Gallo et al., 2006; Irish et al., 2011b) and the preserved ability to share aspects of one’s life story (Usita et al., 1998). As such, in the absence of detailed event-based recollection, semantic elements may be harnessed to foster a sense of narrative continuity by providing self-relevant descriptions of lifetime periods, divorced from any specific episode. While the overall coherence of autobiographical narratives may be reduced in AD compared with healthy older adults, even these somewhat simplified life stories are sufficient to provide a sense of self-continuity across time in AD patients (Tippett et al., 2018).

In contrast, applying our NExt taxonomy to SD reveals an increased provision of general event and general semantic details such as details of frequently experienced events, not specific to any one time (Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2018). At first glance, the increased provision of seemingly semantic details in a patient group characterised by impairments in this memory type is counterintuitive. Such elevated details are therefore unlikely to represent semantic ABM per se and may be better conceptualised as episodic details co-opted into the memory trace (see also Graham et al., 1997; Irish et al., 2012b; McKinnon et al., 2006). Irrespective of the origin of such details, they may contribute to narrative continuity by providing relevant information for one’s life story (Conway and Pleydell-Pearce, 2000). Nonetheless, future studies examining the phenomenology (e.g., autonoetic consciousness, visual imagery) of these detail types across patient groups will be important to ascertain their respective contributions to subjective versus narrative self-continuity. Overall, our review of the extant ABM literature reveals that continuity of the self is not entirely lost in dementia, with distinct elements of preservation emerging contingent on life epoch and dementia syndrome.

3. “I will be”- Envisaging the future

While we tend to exclusively characterise the self in relation to memory for one’s past, it is clear that the self also extends into the future. Much of our waking life consists of planning and imagining our personal future, simulating hypothetical situations and foreseeing different outcomes (Schacter et al., 2012). From an evolutionary perspective, this ability to envisage personally-relevant events is of great adaptive value (Suddendorf et al., 2009; Tulving and Szpunar, 2009), and is integral for a sense of wellbeing (Chandler et al., 2003). Given the close concordance between autobiographical memory and event-based future simulation (Schacter et al., 2012), maintaining a sense of subjective and narrative continuity of self across time requires not only linkage to one’s past, but also a connection with one’s future. As such, projecting oneself into the future via the simulation of self-relevant events can be used to define the self across temporal contexts (D’Argembeau et al., 2012). Characterising how these future self-projections support self-continuity in dementia syndromes is crucial to understanding alterations in the self across temporal contexts. Surprisingly little empirical research, however, has been done on this topic.

3.1. Contributions of episodic elements of future thinking to self-continuity

According to the constructive episodic simulation hypothesis (Schacter and Addis, 2007), imagining a novel, self-relevant future event relies heavily upon the episodic memory system, involving the flexible recombination of contextual details from previous experiences. In line with this framework, deficits in episodic retrieval for the past extend to imagining future events in both AD (Addis et al., 2009; Irish et al., 2012a) and bvFTD (Irish et al., 2013). Despite such striking alterations in the content of future simulations in these conditions, the phenomenological components of these events have proven more difficult to decipher. Interestingly, subjective quality ratings of vividness and level of detail for future events do not differ between AD and control participants (Addis et al., 2009; Irish et al., 2012b). Future studies incorporating ratings of more sensitive measures of subjective self-continuity, such as autonoetic consciousness and egocentric reliving, may prove more informative in this regard (e.g., Irish et al., 2010). Nonetheless, the impoverished episodic content of future simulations in AD and bvFTD implies a distinct narrowing of the temporal window of subjective self-continuity in these disorders. Moreover, the inability to subjectively experience the self in the future has important implications for patients’ daily functioning (Irish and Piolino, 2016; Bulley and Irish, 2018). For example, individuals with AD and bvFTD have difficulty remembering to perform intended actions in the future (prospective memory: Kamminga et al., 2014; van den Berg et al., 2012), as well as impairments in planning ahead and making adaptive financial decisions (Gleichgerrcht et al., 2010).

3.2. A role for semantic representations

Even more intriguing are findings of asymmetric impairments between past and future episodic thinking in SD. Despite preserved recall of recent episodes, future thinking is compromised in this condition at a level comparable to that observed in AD (Irish et al., 2012a; 2012b). Such striking findings suggest that episodic future thinking is not merely mediated by episodic content, but relies heavily on semantic contributions; a central tenet of the semantic scaffolding hypothesis (Irish, 2016; Irish and Piguet, 2013). By this view, future conceptualisations of the self hinge upon semantic scripts, representations, and schemas, which guide one along a prescribed path of typical life events: providing a scaffold for the generation of plausible self-relevant future episodes. Accordingly, while subjective continuity of the self for the past relies entirely on episodic components, we argue that semantic elements are equally important as their episodic counterpart for subjectively experiencing the self in the future. This interaction between episodic and semantic elements further challenges the simplistic episodic-subjective/semantic-narrative dichotomy of self-continuity. Findings on the phenomenology of simulated future events in SD have been mixed, with no difference in subjective quality ratings between SD and controls in one study (Irish et al., 2012b), but reduced autonoetic consciousness for future episodes in another (Remember/Know paradigm, Duval et al., 2012; though this study did not directly probe episodic future thinking). Given the frequent ‘re-casting’ of entire events from one’s past into the future in SD (Irish, 2016; Irish et al., 2012a; 2012b), though, any apparent preservation of autonoetic continuity for future simulations may stem from having experienced the event in the recent past. Such observations have important implications for understanding subjective self-continuity in SD. While these patients retain some continuity of self for the recent past (Irish et al., 2011a; Piolino, 2003), this heavily influences their experience of the self in the future. An inability to foresee the occurrence of novel personal events in the future may lead to a “static” self in SD, with no growth or change over time, which meshes well with the behavioural rigidity observed in this condition. Further supporting this notion, impaired prospection has been associated with increased stereotypical and repetitive behaviours in SD (Kamminga et al., 2014). Importantly, these changes to continuity of the future self may significantly impact mental wellbeing in these patients. A pertinent case study by Hsiao and colleagues (2013) describes a patient with SD who loses the ability to imagine himself in the future. The patient’s profound distress at the loss of his future leads to suicidality as he questions, “What am I going to do for the rest of my life?”. Such striking findings illustrate how loss of the future self may have more devastating effects than changes to self-continuity for the past.

3.3. New approaches to examining the future self

The study of future thinking in clinical populations is relatively new borne, yet we propose that much can be learned from studying the narrative as a whole including the “extraneous” information (i.e., external details) (e.g., Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2018). Of particular interest will be dissecting the external detail profiles generated by AD patients for future events. Findings on the total external details provided for future events in AD have thus far been mixed, with some studies reporting marked reductions (Addis et al., 2009), whereas others reveal comparable total external details to controls (Irish et al., 2012b; Irish et al., 2013). Given the harnessing of semantic information (i.e., general events, personal semantics, and general semantics) to support past narratives in AD (Strikwerda-Brown et al., 2018), a similar pattern may also occur for future simulations. In other words, these patients may be able to construct a personalised semantic framework for the future, containing abstract information about who they may be as a person, details of their life circumstances, and frequently occurring events, even in the absence of specific details of particular episodes. Such findings would indicate some degree of retained narrative continuity across both past and future contexts in AD, despite alterations in subjective continuity, again pointing to preservation of discrete aspects of the self in these patients.

In contrast, the provision of external details is compromised for future and past events in bvFTD, potentially reflecting a global difficulty in generating any form of self-referential material (Irish et al., 2013). As such, the bvFTD syndrome encompasses striking alterations in subjective and narrative aspects of self-continuity, which extends across past, present, and future contexts. Such pervasive shifts in sense of self likely relate to many of the prominent behavioural symptoms that are characteristic of this condition, such as apathy (see Irish et al., 2013). It seems intuitive that not ‘feeling’ (subjective continuity) or ‘knowing’ (narrative continuity) a continuous sense of self that aligns with the present environment may result in reduced motivation to engage in personally relevant goal-directed behaviour, a common thread underlying symptoms of bvFTD (Wong et al., 2018a). The distinct profiles of subjective and narrative self-continuity for the past, present, and future across AD, SD, and bvFTD further speak to the importance of adopting a multifaceted approach to examining the self, considering both episodic and semantic elements, as well as their expression across temporal contexts.

4. “I am”- The unconstrained, mind-wandering self

Up to this point, we have focused on the direct probing of personally-relevant mental time travel in neurodegenerative disorders in the context of mnemonic and prospective tasks. It is clear, however, that self-referential thought often occurs unbidden and unrelated to the task at hand. When external environmental conditions are not sufficiently stimulating, humans tend to redirect their attention inwards in a spontaneous or deliberate fashion, a phenomenon often referred to as “mind-wandering” (Smallwood and Schooler, 2015). Adults have been shown to spend almost half their waking life engaged in off-task thought (Killingsworth and Gilbert, 2010; though estimates may vary dependent on measurement tool, Seli et al., 2018), which can involve travelling through subjective time (remembering the past/imagining the future) or engaging in thoughts about the present/of an atemporal nature (Smallwood and Schooler, 2015). Emerging evidence suggests the frequency and content of spontaneous thoughts are integral to wellbeing and sense of self (Andrews-Hanna et al., 2013; Smallwood and Andrews-Hanna, 2013). As such, studying spontaneously generated expressions of the self may provide a unique glimpse into the subjective self-experience in neurodegenerative disorders not permitted by traditional methods of memory and prospection. Moreover, this approach would allow examination of the natural tendency to engage in different forms of self-referential thought (i.e., past, present, future; episodic, semantic) in the absence of external direction.

4.1. Frequency of mind-wandering in dementia

To date, only two studies to our knowledge have explored the propensity for off-task and/or stimulus-independent thought in dementia. O’Callaghan and colleagues (2019) found alterations in spontaneous cognition in bvFTD and AD under conditions of low cognitive demand. This manifested as a shift towards stimulus-bound thinking in bvFTD, with an increase in thoughts about the immediate environment, at the expense of mind-wandering or off-task thought. Intriguingly, these changes in spontaneous cognition converge strongly with behavioural symptoms of bvFTD, including the environmental dependency syndrome, in which an individual’s actions are almost entirely controlled by their surroundings (Shin et al., 2013). For example, patients may spontaneously imitate actions or speech, or attempt to use any item placed in front of them (‘utilisation behaviour’), such as drinking from the coffee cup of another person (Ghosh et al., 2012), and often fail to initiate behaviour or conversation without external prompting (Quaranta et al., 2012). We tentatively speculate that this profound dependence on the immediate environment in bvFTD may stem from impaired access to internally-driven self-referential cognitive processes. In the absence of a continuous subjective and/or narrative sense of self, patients may turn their attention outwards towards the external environment. By contrast, AD patients displayed off-task thought at intermediate levels to bvFTD patients and controls (O’Callaghan et al., 2019). This finding suggests that under conditions of minimal cognitive demand, which mirror the circumstances in which mind-wandering occurs in daily life, AD patients retain some capacity for spontaneous thought. In contrast, however, a recent study revealed that under more cognitively demanding conditions, mind-wandering is reduced in AD (Gyurkovics et al., 2018), emphasising the importance of considering task requirements when interpreting findings in this field (see also Seli et al., 2018). Whether changes in the propensity for mind-wandering in dementia reflect altered spontaneous versus deliberate off-task thought (see Smallwood and Schooler, 2015) remains unknown, and represents an important question for refining our understanding of the subjective experience of these patients.

4.2. Temporal content of mind-wandering

While preliminary evidence of alterations in the frequency of mind-wandering in dementia is accumulating, a more in-depth understanding of the everyday self-experience of these patients will be provided by studying the content of off-task thoughts. Mind-wandering generally consists of a combination of past, future, and present-oriented thoughts in healthy individuals, though their relative proportions depend upon the method of assessment. In healthy ageing and amnesic patients, a shift towards present/atemporal oriented thoughts is revealed under undirected or low cognitive demand conditions (Irish et al., 2018; Jackson et al., 2013; McCormick et al., 2018). This parallels the changes in mental time travel abilities in these populations, suggesting the content of an individual’s spontaneous thought may reflect the relative accessibility of its constituent elements (O’Callaghan and Irish, 2018). A similar bias towards present-oriented spontaneous thoughts, then, may also be expected in AD, SD, and bvFTD, in the face of disrupted past and future thinking. In support of this view, patients with AD and SD have been found to increasingly use the present, rather than past, tense during self-narratives (Irish et al., 2015). Examining the temporal content of spontaneous cognition in dementia provides an exciting opportunity to clarify the width of the temporal window of the self as experienced moment-to-moment. Furthermore, instances of mind-wandering vary in their self-relevance. For example, healthy older adults have been found to shift away from self-focused spontaneous cognition towards increased thoughts about other people (Irish et al., 2018). The self-referential content of spontaneous cognition in dementia remains to be explored, but may further uncover the nature of the self in the here-and-now in these patients.

4.3. Episodic and semantic content

Like other forms of mental construction, spontaneous cognition comprises episodic and semantic elements (O’Callaghan and Irish, 2018), the relative weighting of which varies across different populations (O’Callaghan et al., 2015; McCormick et al., 2018). Given the importance of these elements for continuity of the self, examining their prevalence during mind-wandering instances in dementia may inform how subjective and narrative self-continuity are spontaneously experienced. Of note, amnesic patients, faced with stark episodic memory deficits, primarily furnish their instances of mind-wandering with semantic elements (McCormick et al., 2018). This suggests that the most accessible content is preferentially harnessed during spontaneous cognition, not unlike that observed during deliberate instances of past and future thinking. In the absence of access to episodic elements, AD patients may default to predominantly semantic content during mind wandering (e.g., personal facts), largely drawing upon the self-narrative to support the self in the present. The contrasting memory profiles in SD, however, may result in a predominantly episodic style of mind wandering. Such thoughts would be predicted to comprise the replay of recent episodes that remain accessible, providing some sense of subjective self-continuity for the recent past. An increased focus on the frequency and content of spontaneous expressions of the self will be essential to improve our understanding of the subjective experience of the individual living with dementia. More crucially, such investigations may provide important insights to guide appropriate interventions to improve overall quality of life in dementia.

5. Conclusion

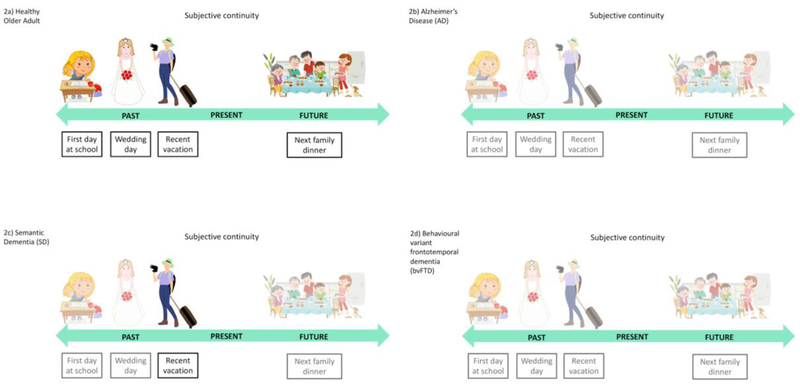

Our objective in writing this review was to direct attention away from the misperception often observed in the literature that loss of memory equates to a global loss of self. In reviewing the available evidence on deliberate and spontaneous expressions of memory and the self, we uncover distinct profiles of loss and sparing across the dementia syndromes of AD, SD, and bvFTD, each of which reveals important insights into their everyday functioning and behavioural symptoms (Figures 2 and 3). In sum, according to the framework that we have outlined in this review, extant research suggests that the impoverished capacity for episodic expressions of past and future thinking in AD may lead to a global decay in subjective self-continuity across temporal contexts. By contrast, the impaired recent, but spared remote, personal semantic memory in these patients may allow for a preserved, though outdated, self-narrative. SD patients, however, appear to retain subjective and narrative self-continuity for the recent past, but not the remote past or future, leading to a self defined predominantly by recent experiences. Finally, bvFTD results in globally impaired subjective and narrative self-continuity, with the absence of an appropriate self-schema to guide and regulate behaviour. Notably, our approach highlights the multifaceted and dynamic nature in which the self is likely to change in healthy and pathological ageing, with important ramifications for the development of person-centred care.

Figure 2:

(A) Episodic re-experiencing of significant autobiographical events (e.g., first day at school, wedding day, a recent holiday) and pre-experiencing of potential self-relevant future occurrences (e.g., next family dinner) gives rise to a subjective sense of self-continuity across temporal contexts. (B) In AD, impoverished episodic memory and future construction leads to a global decay in subjective self-continuity across temporal contexts (C) SD patients retain subjective self-continuity for the recent past, however they are unable to mentally re-experience remote memories or simulate novel events in the future. (D) bvFTD results in globally impaired subjective continuity for both past and future periods.

Figure 3:

(A) The weaving of personal facts from across the lifespan into a life story (e.g., grew up in the UK, worked as a doctor, and have one grandchild) and foreseeing who one may be in the future (e.g., becoming a grandmother of two) provides a sense of narrative-self continuity spanning past, present, and future. These personal facts may be integrated into a ‘self-schema’, informing “Who I Am” and guiding behaviour accordingly. (B) In AD, personal semantic memory is affected for the recent period, but relatively spared for the remote past. This leads to a preserved, but outdated, self-narrative, with “Who I was” becoming “Who I am”. Narrative continuity for the future remains to be explored. (C) SD patients retain narrative self-continuity for the recent past, with behaviour exclusively guided by recent experiences. Narrative continuity for the remote period, and the future, however, is impaired (D) bvFTD results in the progressive deterioration of the self, leading to globally impaired narrative self-continuity for past and future time periods, with an absence of a self-schema to guide appropriate behaviour.

Looking ahead, we propose that a refined understanding of the self in dementia is essential. To fully appreciate the differing profiles of loss and sparing, fine-grained analysis of past and future narratives will help to further elucidate episodic and semantic contributions to self-referential forms of (re)construction. In addition, consistent with recent studies (Tippett et al., 2018), naturalistic measures of narrative continuity should be employed, including autobiographical life stories (Grilli et al., 2018) in addition to narratives of episodic memories (e.g., the AI, Levine et al., 2002). This convergent approach will capture the integration of memories into a meaningful, personal story, as opposed to the isolated recall of personal semantic facts, devoid of context. Detailed examination of the content of spontaneous thought, such as temporal context, self-referential nature, and episodic and semantic elements, will be of utmost importance in understanding the everyday experience of self-continuity in neurodegenerative disorders. Furthermore, given the limitations of existing measures of the ‘self (i.e., questionnaires requiring insight and higher-level cognitive abilities), multidimensional assessment tools will be required, incorporating carer ratings capturing how facets of the self may be altered in daily life, in areas such as functioning, behaviour, wellbeing, mood, motivation, and social engagement. Consistent with existing theoretical frameworks (Haslam et al., 2011; Prebble et al., 2013), this review has predominantly focused on autonoetic (i.e., subjective) and noetic (i.e., narrative) expressions of self-continuity. Whether intact implicit and procedural memory permit the persistence of self-continuity at an ‘anoetic’, experiential level in dementia represents an intriguing avenue for future inquiry (see Vandekerckhove, 2009; Vandekerckhove et al., 2014; Vandekerckhove and Panksepp, 2011). Finally, as most studies to date have focused on patients in the mild to moderate stage of dementia, increased research is required into how the self changes across the lifespan and with the onset and progression of neurodegenerative disease. Collectively, we aim to stimulate further concerted research efforts to understand and promote a cohesive sense of self in dementia, across past, present, and future contexts, by demonstrating how, ultimately, ‘All is not lost’.

Highlights.

Memory impairments in dementia do not necessarily equate to a loss of self

Distinct aspects of the self may be affected, while others remain preserved

Understanding the self in dementia will assist in developing person-centered care

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by an Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence in Cognition and its Disorders (CE110001021). CSB is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Postgraduate Scholarship (APP1132764). MG is supported by the Arizona Alzheimer’s Consortium, Department of Health Services. JAH is supported by an NIA funded Alzheimer’s Disease Center (P30 AG019610) and the University of Arizona’s Department of Psychology and Cognitive Science Program. MI is supported by an ARC Future Fellowship (FT160100096).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Addis DR, and Tippett LJ (2004). Memory of myself: autobiographical memory and identity in Alzheimer’s disease. Memory 12, 56–74. doi: 10.1080/09658210244000423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addis DR, and Tippett LJ (2008). The contributions of autobiographical memory to the content and continuity of identity: A social-cognitive neuroscience approach Self continuity: Individual and collective perspectives, (pp. 71–84). New York, NY, US: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Addis DR, Sacchetti DC, Ally BA, Budson AE, and Schacter DL (2009). Episodic simulation of future events is impaired in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia 47, 2660–2671. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed RM, Irish M, Kam J, van Keizerswaard J, Bartley L, Samaras K, et al. (2014). Quantifying the eating abnormalities in frontotemporal dementia. JAMA Neurol 71, 1540–1546. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alea N, and Bluck S (2003). Why are you telling me that? A conceptual model of the social function of autobiographical memory. Memory 11, 165–178. doi: 10.1080/741938207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews-Hanna JR, Kaiser RH, Turner AEJ, Reineberg AE, Godinez D, Dimidjian S, et al. (2013). A penny for your thoughts: dimensions of self-generated thought content and relationships with individual differences in emotional wellbeing. Front. Psychol. 4, 900. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird A (2019). A reflection on the complexity of the self in severe dementia. Cogent Psychology, 6(1), 1–5. doi: 10.1080/23311908.2019.1574055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnabe A, Whitehead V, Pilon R, Arsenault-Lapierre G, and Chertkow H (2012). Autobiographical memory in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: A comparison between the Levine and Kopelman interview methodologies. Hippocampus 22, 1809–1825. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastin C, Feyers D, Souchay C, Guillaume B, Pepin J-L, Lemaire C, et al. (2011). Frontal and posterior cingulate metabolic impairment in the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia with impaired autonoetic consciousness. Hum. Brain Mapp 33, 1268–1278. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin MJ, Cifelli A, Garrard P, Caine D, and Jones FW (2015). The role of working memory and verbal fluency in autobiographical memory in early Alzheimer’s disease and matched controls. Neuropsychologia 78, 115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozeat S, Gregory CA, Ralph MA, and Hodges JR (2000). Which neuropsychiatric and behavioural features distinguish frontal and temporal variants of frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer’s disease? Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 69, 178–186. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulley A, and Irish M (2018). The functions of prospection – Variations in health and disease. Front. Psychol 9, 2328. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buñuel L (2011). My last breath. Random House.

- Burianová H, and Grady CL (2007). Common and unique neural activations in autobiographical, episodic, and semantic retrieval. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 19, 1520–1534. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.9.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caddell LS, and Clare L (2010). The impact of dementia on self and identity: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review 30, 113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MJ, Lalonde CE, Sokol BW, and Hallett D (2003). Personal persistence, identity development, and suicide: a study of Native and Non-native North American adolescents. Monogr Roc Res ChildDev 68, vii–viii. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2003.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway MA, and Pleydell-Pearce CW (2000). The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system. Psychological review 107, 261–288. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.107.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craver CF (2012). A Preliminary Case for Amnesic Selves: Toward a Clinical Moral Psychology. Social Cognition 30, 449–473. doi: 10.1521/soco.2012.30.4.449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Argembeau A, Lardi C, and Van der Linden M (2012). Self-defining future projections: exploring the identity function of thinking about the future. Memory 20, 110–120. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2011.647697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DHJ (2004). Dementia: sociological and philosophical constructions. Soc SciMed 58, 369–378. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl-Schmid J, Schmidt E-M, Nunnemann S, Riedl L, Kurz A, Forstl FL, et al. (2013). Caregiver Burden and Needs in Frontotemporal Dementia. Journal of geriatric psychiatry and neurology 26, 221–229. doi: 10.1177/0891988713498467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs M (1997). The emergence of the person in dementia research. Ageing Soc 17, 597–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval C, Desgranges B, la Sayette, de V, Belliard S, Eustache F, and Piolino P (2012). What happens to personal identity when semantic knowledge degrades? A study of the self and autobiographical memory in semantic dementia. Neuropsychologia 50, 254–265. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eustache ML, Laisney M, Juskenaite A, Letortu O, Platel FL, Eustache F, et al. (2013). Sense of identity in advanced Alzheimer’s dementia: A cognitive dissociation between sameness and selfhood? Consciousness and Cognition 22, 1456–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feast A, Orrell M, Charlesworth G, Melunsky N, Poland F, and Moniz-Cook E (2016). Behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia and the challenges for family carers: Systematic review. British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(5), 429–434. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.153684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitts WH, and Warren WL (1996). Tennessee self-concept scale: TSCS-2. Western Psychological Services Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A, and Smith RW (1989). Alzheimer’s Disease Victims: The ‘Unbecoming’ of Self and the Normalization of Competence. Sociological Perspectives 32, 35–46. doi: 10.2307/1389006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo DA, Shahid KR, Olson MA, Solomon TM, Schacter DL, and Budson AE (2006). Overdependence on degraded gist memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology 20, 625–632. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.20.6.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Dutt A, Bhargava P, and Snowden J (2012). Environmental dependency behaviours in frontotemporal dementia: have we been underrating them? J Neurol 260, 861–868. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6722-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleichgerrcht E, Ibanez A, Roca M, Torralva T, and Manes F (2010). Decision-making cognition in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature Publishing Group 6, 611–623. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham KS, and Hodges JR (1997). Differentiating the roles of the hippocampal complex and the neocortex in long-term memory storage: evidence from the study of semantic dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology 11, 77–89. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.11.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham KS, Lambon MA, and Hodges RJR (1997). Determining the Impact of Autobiographical Experience on “Meaning”: New Insights from Investigating Sports-related Vocabulary and Knowledge in Two Cases with Semantic Dementia. Cognitive Neuropsychology 14, 801–837. doi: 10.1080/026432997381367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg DL, and Verfaellie M (2010). Interdependence of episodic and semantic memory: evidence from neuropsychology. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 16, 748–753. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710000676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene J, Hodges JR, and Baddeley AD (1995). Autobiographical memory and executive function in early dementia of Alzheimer type. Neuropsychologia 33, 1647–1670. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(95)00046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilli MD, and Verfaellie M (2014). Personal semantic memory: insights from neuropsychological research on amnesia. Neuropsychologia 61, 56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilli MD, and Verfaellie M (2015). Supporting the self-concept with memory: insight from amnesia. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 10, 1684–1692. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsv056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilli MD, Wank AA, and Verfaellie M (2018). The life stories of adults with amnesia: Insights into the contribution of the medial temporal lobes to the organization of autobiographical memory. Neuropsychologia 110, 84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyurkovics M, Balota DA, and Jackson JD (2018). Mind-wandering in healthy aging and early stage Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology 32, 89–101. doi: 10.1037/neu0000385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson C, and Morris K (2016). Dementia: Sustaining Self in the Face of Cognitive Decline. Geriatrics, 7(4), 25. doi: 10.3390/geriatricsl040025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison BE, Therrien BA, and Giordani BJ (2005). Alzheimer’s disease behaviors from past self-identities: An exploration of the memory and cognitive features. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementiasr, 20(4), 248–254 doi: 10.1177/153331750502000405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam C, Jetten J, Haslam SA, Pugliese C, and Tonks J (2011). ‘I remember therefore I am, and I am therefore I remember’: Exploring the contributions of episodic and semantic self-knowledge to strength of identity. 102(2), 184–203. doi: 10.1348/000712610x508091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes BK, Ramanan S, and Irish M (2018). “Truth be told” - Semantic memory as the scaffold for veridical communication. Behavioural and Brain Sciences 41, el5. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X17001364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehman JA, German TP, and Klein SB (2005). Impaired Self-Recognition from Recent Photographs in a Case of Late-Stage Alzheimer’s Disease. Social Cognition 23, 118–124. doi: 10.1521/soco.23.1.118.59197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hershfield ΗE (2011). Future self-continuity: how conceptions of the future self transform intertemporal choice. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1235, 30–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilts PJ (1995). Memory’s Ghost: The Strange Tale of Mr. M and the Nature of Memory. Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges JR, Mitchell J, Dawson K, Spillantini MG, Xuereb JH, McMonagle P, et al. (2010). Semantic dementia: demography, familial factors and survival in a consecutive series of 100 cases. Brain 133, 300–306. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou CE, Miller BL, and Kramer JH (2005). Patterns of autobiographical memory loss in dementia. Int. J. Geriat. Psychiatry 20, 809–815. doi: 10.1002/gps,1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao JJ, Kaiser N, Fong SS, and Mendez MF (2013). Suicidal Behavior and Loss of the Future Self in Semantic Dementia. Cognitive And Behavioral Neurology 26, 85–92. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e31829c671d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh S, Irish M, Daveson N, Hodges JR, and Piguet O (2013). When one loses empathy: its effect on carers of patients with dementia. Journal of geriatric psychiatry and neurology 26, 174–184. doi: 10.1177/0891988713495448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume D (1739).A Treatise of Human Nature: Being an Attempt to Introduce the Experimental Method of Reasoning Into Moral Subjects. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Irish M (2016). “Semantic memory as the essential scaffold for future oriented mental time travel,” in Seeing the Future: Theoretical Perspectives on Future-Oriented Mental Time Travel \ eds.Michaelian K, Klein SB, and Szpunar K (New York: Oxford University Press; ), 388–408. [Google Scholar]

- Irish M (in press). “On the interaction between episodic and semantic representations – Constructing a unified account of imagination” in The Cambridge Handbook of Imagination, ed.Abraham A. [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Addis DR, Hodges JR, and Piguet O (2012a). Considering the role of semantic memory in episodic future thinking: evidence from semantic dementia. Brain 135, 2178–2191. doi: 10.1093/brain/awsll9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Addis DR, Hodges JR, and Piguet O (2012b). Exploring the content and quality of episodic future simulations in semantic dementia. Neuropsychologia 50, 3488–3495. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, and Piguet O (2013). The pivotal role of semantic memory in remembering the past and imagining the future. Front. Behav. Neurosci 7, 27. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, and Piolino P (2016). Impaired capacity for prospection in the dementias - Theoretical and clinical implications. Br J Clin Psychol 55, 49–68. doi: 10.Ill1/bjc.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Cunningham CJ, Walsh JB, Coakley D, Lawlor BA, Robertson IH, et al. (2006). Investigating the enhancing effect of music on autobiographical memory in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 22, 108–120. doi: 10.1159/000093487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Goldberg Z, Alaeddin S, O’Callaghan C, Andrews-Hanna JR (2018). Age-related changes in the temporal focus and self-referential content of spontaneous cognition during periods of low cognitive demand. Psychol Res. doi: 10.1007/s00426-018-1102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Hodges JR, and Piguet O (2013). Episodic future thinking is impaired in the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. CORTEX49, 2377–2388. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Homberger M, Lah S, Miller L, Pengas G, Nestor PJ, et al. (2011a). Profiles of recent autobiographical memory retrieval in semantic dementia, behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia 49, 2694–2702. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Kamminga J, Addis DR, Crain S, Thornton R, Hodges JR, et al. (2015). “Language of the past” - Exploring past tense disruption during autobiographical narration in neurodegenerative disorders. J Neuropsychol 10, 295–316. doi: 10.Ill1/jnp.12073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Landin-Romero R, Mothakunnel A, Ramanan S, Hsieh S, Hodges JR, et al. (2018). Evolution of autobiographical memory impairments in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia - a longitudinal neuroimaging study. Neuropsychologia, 110, 14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Lawlor BA, O’Mara SM, and Coen RF (2008). Assessment of behavioural markers of autonoetic consciousness during episodic autobiographical memory retrieval: a preliminary analysis. Behavioural neurology 19, 3–6. doi: 10.1155/2008/691925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Lawlor BA, O’Mara SM, and Coen RF (2010). Exploring the recollective experience during autobiographical memory retrieval in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 16, 546–555. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710000172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Lawlor BA, O’Mara SM, and Coen RF (2011b). Impaired capacity for autonoetic reliving during autobiographical event recall in mild Alzheimer’s disease. CORTEX47, 236–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Piguet O, and Hodges JR (2012c). Self-projection and the default network in frontotemporal dementia. Nature Publishing Group 8, 152–161. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish M, Piguet O, Hodges JR, and Hornberger M (2014). Common and unique gray matter correlates of episodic memory dysfunction in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35, 1422–1435. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JD, Weinstein Y, and Balota DA (2013). Can mind-wandering be timeless? Atemporal focus and aging in mind-wandering paradigms. Front. Psychol 4, 742. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamminga J, O’Callaghan C, Hodges JR, and Irish M (2014). Differential prospective memory profiles in frontotemporal dementia syndromes. JAD 38, 669–679. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazui H, Hashimoto M, Hirono N, Imamura T, Tanimukai S, Hanihara T, et al. (2000). A Study of Remote Memory Impairment in Alzheimer’s Disease by Using the Family Line Test. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 11, 53–58. doi: 10.1159/000017214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killingsworth MA, and Gilbert DT (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science 330, 932. doi: 10.1126/science.1192439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitwood T (1989). Brain, Mind and Dementia: With Particular Reference to Alzheimer’s Disease. Ageing and Society, 9(1), 1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X00013337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SB, Cosmides L, and Costabile KA (2003). Preserved knowledge of self in a case of Alzheimer’s dementia. Social Cognition 21, 157–165. doi: 10.1521/soco.21.2.157.21317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SB, Loftus J, and Kihlstrom JF (2002). Memory and temporal experience: the effects of episodic memory loss on an amnesic patient’s ability to remember the past and imagine the future. Social Cognition 20, 353–379. doi: 10.1521/soco.20.5.353.21125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kopelman MD, Wilson BA, and Baddeley AD (1989). The autobiographical memory interview: a new assessment of autobiographical and personal semantic memory in amnesic patients. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology (Neuropsychology, Development and Cognition: Section A) 11, 724–744. doi: 10.1080/01688638908400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn ΜH, and McPartland TS (1954). An Empirical Investigation of Self-Attitudes. American Sociological Review 19, 68–76. doi: 10.2307/2088175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumfor F, Teo D, Miller L, Lah S, Mioshi E, Hodges JR, et al. (2016). Examining the Relationship Between Autobiographical Memory Impairment and Carer Burden in Dementia Syndromes. JAD 51, 237–248. doi: 10.3233/jad-150740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Svoboda E, Hay JF, Winocur G, and Moscovitch M (2002). Aging and autobiographical memory: Dissociating episodic from semantic retrieval. Psychology and Aging 17, 677–689. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke J (1690). An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, 1690 Menston, Scolar Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mahr J, and Csibra G (2017). Why do we remember? The communicative function of episodic memory. Behavioural and Brain Sciences 41, 1–93. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X17000012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus Η (1977). Self-schemata and processing information about the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 35, 63–78. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.35.2.63. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matuszewski V, Piolino P, La Sayette, de V, Lalevee C, Pelerin A, Dupuy B, et al. (2006). Retrieval mechanisms for autobiographical memories: Insights from the frontal variant of frontotemporal dementia. Neuropsychologia 44, 2386–2397. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP (2001). The psychology of life stories. Review of General Psychology 5, 100–122. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.5.2.100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick C, Rosenthal CR, Miller TD, and Maguire EA (2018). Mind-Wandering in People with Hippocampal Damage. Journal of Neuroscience 38, 2745–2754. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1812-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon MC, Black SE, Miller B, Moscovitch M, and Levine B (2006). Autobiographical memory in semantic dementia: Implications for theories of limbic-neocortical interaction in remote memory. Neuropsychologia 44, 2421–2429. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe J, Van Snellenberg JX, DeRosse P, Balsam P, and Malhotra AK (2012). Judgements of agency in schizophrenia: an impairment in autonoetic metacognition. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 367, 1391–1400. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mioshi E, Kipps CM, Dawson K, Mitchell J, Graham A, and Hodges JR (2007). Activities of daily living in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. Neurology 68, 2077–2084. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000264897.13722.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]