Short abstract

Osteoradionecrosis (ORN) is a complication of radiation therapy for which several treatment options have been reported. The use of platelet‐rich fibrin (PRF), a second-generation platelet concentrate, has been promoted in refractory wounds. A 53-year-old man underwent concurrent chemoradiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma in the right side of the tongue. Subsequently, he exhibited pus discharge around the right maxillary first molar. Intraoral examination showed mobility and probing depths of >10 mm in teeth 15 and 16. Computed tomography revealed poorly defined osteolytic changes in teeth 15 to 17, indicative of oroantral fistula. Teeth 15 to 17 were extracted and the socket was debrided. Primary closure was achieved after PRF dressing. The wound healed within 2 weeks. The patient returned because of spontaneous loss of tooth 46 and numbness over the right lower lip. Pus was present in premolar areas and in the tooth 46 socket. Radiographic examination showed moth-eaten destruction in right mandibular teeth and better trabecular quality in the right maxilla. A provisional diagnosis of ORN was made. Debridement and primary closure after PRF dressing were performed. The mucosa healed within 3 weeks. Our findings suggest that PRF combined with a surgical approach might be useful for treatment of ORN.

Keywords: Osteoradionecrosis, platelet‐rich fibrin, radiation therapy, oroantral fistula, debridement, squamous cell carcinoma

Introduction

Osteoradionecrosis (ORN) of the jaws is regarded as delayed radiation-induced injury, characterized by radiation-induced ischemic necrosis of bone with associated soft tissue necrosis and failure to heal. It occurs in the absence of primary tumor, recurrence, or metastatic disease.1 The most important risk factor is surgical trauma, generally involving dental extractions; however, it can also occur in the absence of trauma. Other risk factors have also been reported, such as pre-radiotherapy tooth extractions, smoking, and radiation therapy techniques.2 The reported incidence of ORN was 4.16% in patients who underwent pre-radiotherapy dental extraction,3 whereas it was 7% after tooth extraction in irradiated patients.4 Periodontitis may contribute to the onset of ORN due to hyposalivation and loss of tooth‐supporting tissues.5

A technique involving the application of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) was originally developed by Choukroun et al.6 Importantly, it does not require the use of anticoagulant or any other gelling agent, such as bovine thrombin. PRF can release growth factors7 and promote the healing process,8 even in chronic wounds in locations distant from the site of PRF application.9 Local application of PRF after debridement can relieve pain and reduce the occurrence of postoperative infections. In this case report, we describe treatment for ORN of the jaw induced by periodontitis, comprising conservative therapy and debridement combined with PRF dressing.

Case report

A systemically healthy 53-year-old man was referred from the periodontist in July 2017 for the management of oroantral fistula with pus formation over the gingival sulcus of the upper right first molar, which had been present for 1 month. The patient had been diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma in the right side of the tongue, staged as T1N0M0 in October 2012, for which he received external beam radiation therapy by tomotherapy at a total dose of 72 Gy; concurrent cisplatin treatment was administered weekly. The patient’s hygiene was fair. Pre-radiation oral clinical and radiographic examination revealed average health (Figure 1a). The patient also attended periodontal follow-up sessions every 3 months.

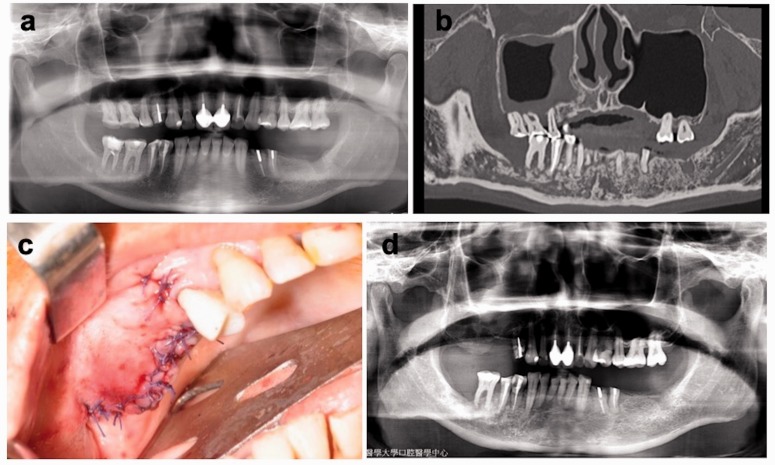

Figure 1.

First debridement, teeth 15 to 17. (a) Pre-radiation panoramic radiographic examination showed average health. (b) Dental view via computed tomography revealed bony destruction involving teeth 15 to 17 and 41 to 46 with a thickened sinus membrane in the right maxillary sinus. (c) Primary closure was achieved using a buccal fat pad flap and a buccal advancement flap after platelet‐rich fibrin dressing. (d) Postoperative panoramic radiographic examination showed minimal alveolar bone in the right maxillary posterior region and minimal cloudiness of the right maxillary sinus.

Intraoral examination showed mild gingival swelling with mobility of teeth 15 and 16. The probing depths of both teeth exceeded 10 mm over the buccal area; pus discharge and bleeding were present around these teeth. The mandibular right teeth also showed minimal mobility, with periodontal pocket depths of 3 to 5 mm. Multidetector row helical computed tomography with multiplanar reconstruction revealed poorly defined osteolytic changes with bony destruction involving teeth 15 to 17, as well as teeth 41 to 46, compatible with an oroantral fistula (Figure 1b). Conservative therapy was initiated, including antibiotics and irrigation, but was unsuccessful. Teeth 15 to 17 were extracted; necrotic bone and granulation tissue were debrided. Double-layer watertight closure was achieved using a buccal fat pad flap and a buccal advancement flap after PRF dressing was applied to the bony defect (Figure 1c). The patient returned for wound inspection and suture removal 2 weeks later (Figure 1d). The wound healing was uneventful, and the final histopathology examination revealed nonviable bone and a mixed inflammatory cell infiltration, confirming the suspected diagnosis of osteonecrosis.

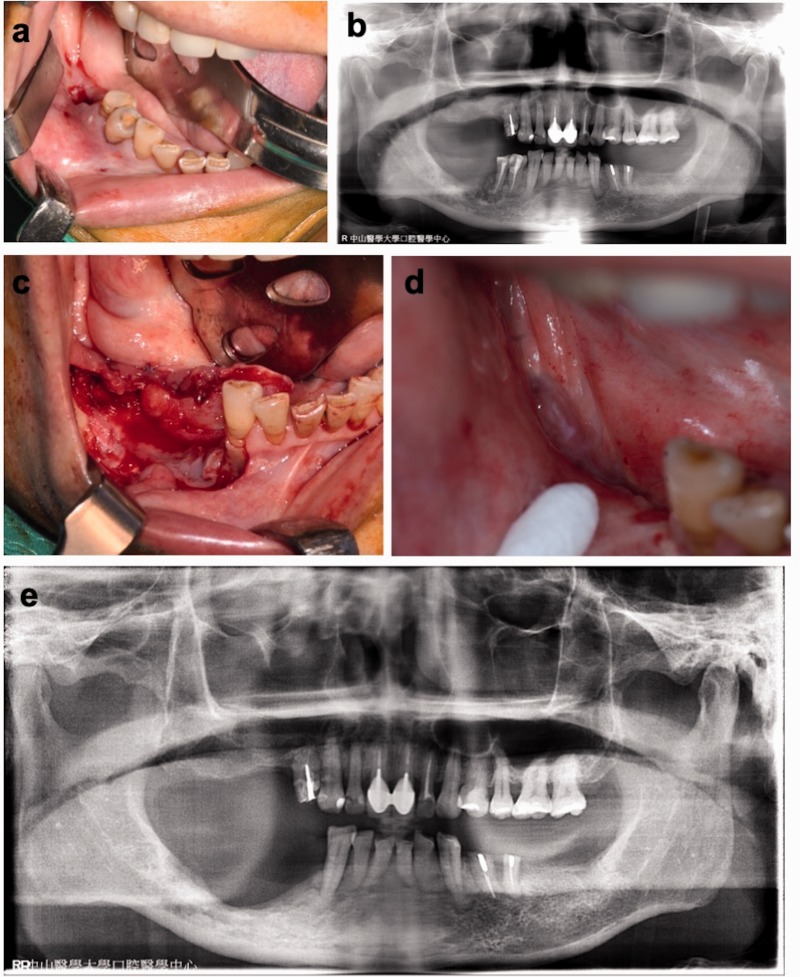

The patient returned in February 2018 due to spontaneous loss of tooth 46, 1 month prior to visiting the clinic, as well as numbness over the right lower lip. Suppuration was elicited on palpation of the gingiva, both in premolar areas and in the unhealed tooth 46 socket (Figure 2a). Probing depths were 8 mm in teeth 44 and 45; these teeth exhibited grades 2 and 3 mobility, respectively. The panoramic radiographic examination demonstrated progressive moth-eaten destruction of the alveolar bone on the right mandibular teeth, compared with the previous image (Figure 2b); it also revealed better trabecular quality in the right maxilla. A diagnosis of stage 3 ORN10 over the right mandible was made. Conservative therapy and debridement were performed, followed by primary closure with lingual advancement flap after the application of PRF dressing (Figure 2c). The mucosa healed completely within 3 weeks (Figure 2d). The final histopathology examination also revealed osteonecrosis, concomitant with an abscess and granulation tissue. Ten months postoperatively, a follow-up radiographic examination demonstrated that the bone healing process was progressing well. The patient is undergoing periodic clinical follow-up (Figure 2e). The patient consented to publication of this report, and all identifying information has been excluded.

Figure 2.

Second debridement, teeth 44 to 46. (a) Unhealed tooth 46 socket and gingival swelling over teeth 45 and 44 with concomitant abscess formation. (b) Panoramic radiographic examination demonstrated progressive poorly defined bony destruction of the right mandible, involving the inferior alveolar nerve. The right maxilla exhibited better bony formation. (c) Debridement and placement of platelet‐rich fibrin were performed. (d) Within 3 weeks postoperatively, the mucosa had healed completely. (e) Good bone healing was observed in the right mandible at 10 months postoperatively.

Discussion

Currently, the radiation-induced fibroatrophic process described by Delanian and Lefaix is regarded as the primary mechanism underlying radiation-associated tissue injury.11 Cell cultures of human fibroblasts on established radiation-induced fibroatrophic processes have shown reduced expression levels of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and other proinflammatory cytokines, which may comprise molecular markers of ORN. Current approaches for the treatment of ORN include a combination of antifibrotic drugs, hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT), and sequestrectomy. These treatment options are selected based on the severity of ORN. Assessment of available evidence and expert opinion via literature review suggest that routine use of HBOT for the prevention or management of ORN is not recommended, and is rarely implemented in the clinic.12 Other medication therapies, including tocopherol, pentoxifylline, and clodronate, require stronger supporting evidence in the form of randomized clinical trial results.13 Several reports have shown that the application of PRF as the sole filling material in preprosthetic surgery and implantation elicited new bone formation in the augmented areas.14,15 We previously reported that the application of PRF for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw demonstrated wound closure and new bone regeneration.16 PRF can increase osteoblast attachment, proliferation by the Akt pathway, and matrix synthesis through the actions of heat shock protein 47 and the upregulation of collagen‐related protein production.17 These combined effects promote bone healing and regeneration. The PRF application protocol was very simple and could produce a substantial amount of autologous growth factors, cytokines, and wound healing proteins (e.g., TGF-β, platelet-derived growth factor AB, and vascular endothelial growth factor) for >7 days in vitro. Furthermore, the PRF remains usable for many hours after preparation if it is prepared correctly and maintained in physiologic conditions.18,19 During wound healing in this case, we utilized the ability of PRF to gradually release growth factors into lower grade ORN, which persist for a considerable length of time.

Current published literature on radiation-associated tissue injury indicates that there are several effective therapeutic strategies for improving tissue healing, but a gold standard treatment has not yet been established.13 In the present case, the combination of sequestrectomy and PRF was effective and beneficial in the treatment of ORN, but more robust data, in the form of randomized controlled trials, are needed to confirm the effectiveness of our approach.

In conclusion, the potential for development of ORN can be minimized by oral evaluation before irradiation and routine dental check-up after irradiation. Tooth extraction after radiotherapy is strongly associated with the development of ORN,20 which suggests that teeth that cannot be preserved for an extended period of time should be extracted before irradiation. In dental extractions performed after irradiation, it is necessary to ensure minimal trauma, perform primary closure, and administer adjunctive therapies.21 In the present case, the patient’s general dental condition was good and conservative periodontal therapies were applied routinely to prevent the need for extraction, thus preventing exacerbation of ORN. Antibiotics were administered, in combination with irrigation and debridement, if infectious signs were present in focal areas. Thus, the combination of sequestrectomy and PRF might be effective and beneficial for treatment of ORN.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Rice N, Polyzois I, Ekanayake K, et al. The management of osteoradionecrosis of the jaws – a review. Surgeon 2015; 13: 101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moon DH, Moon SH, Wang K, et al. Incidence of, and risk factors for, mandibular osteoradionecrosis in patients with oral cavity and oropharynx cancers. Oral Oncol 2017; 72: 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang Y, Zhu X, Qu S. Incidence of osteoradionecrosis in patients who have undergone dental extraction prior to radiotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surgery Med Pathol 2014; 26: 269–275. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nabil S, Samman N. Incidence and prevention of osteoradionecrosis after dental extraction in irradiated patients: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011; 40: 229–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sroussi HY, Epstein JB, Bensadoun RJ, et al. Common oral complications of head and neck cancer radiation therapy: mucositis, infections, saliva change, fibrosis, sensory dysfunctions, dental caries, periodontal disease, and osteoradionecrosis. Cancer Med 2017; 6: 2918–2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choukroun J, Adda F, Schoeffer C, et al. PRF: an opportunity in perio-implantology. Implantodontie 2000; 42: 55–62. [in French] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai CH, Shen SY, Zhao JH, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin modulates cell proliferation of human periodontally related cells in vitro. J Dent Sci 2009; 4: 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao JH, Tsai CH, Chang YC. Clinical and histologic evaluations of healing in an extraction socket filled with platelet-rich fibrin. J Dent Sci 2011; 6: 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinto NR, Ubilla M, Zamora Y, et al. Leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF) as a regenerative medicine strategy for the treatment of refractory leg ulcers: a prospective cohort study. Platelets 2018; 29: 468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyons A, Osher J, Warner E, et al. Osteoradionecrosis–a review of current concepts in defining the extent of the disease and a new classification proposal. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014; 52: 392–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delanian S, Lefaix JL. The radiation-induced fibroatrophic process: therapeutic perspective via the antioxidant pathway. Radiother Oncol 2004; 73: 119–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sultan A, Hanna GJ, Margalit DN, et al. The use of hyperbaric oxygen for the prevention and management of osteoradionecrosis of the jaw: a Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center Multidisciplinary Guideline. Oncologist 2017; 22: 343–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costa DA, Costa TP, Netto EC, et al. New perspectives on the conservative management of osteoradionecrosis of the mandible: a literature review. Head Neck 2016; 38: 1708–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen YT, Chiu YW, Chang YC. Effects of platelet-rich fibrin on healing of an extraction socket with buccal cortical plate dehiscence. J Dent Sci 2019; 14: 103–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao JH, Chang YC. Alveolar ridge preservation following tooth extraction using platelet-rich fibrin as the sole grafting material. J Dent Sci 2016; 11: 345–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai LL, Huang YF, Chang YC. Treatment of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw with platelet-rich fibrin. J Formos Med Assoc 2016; 115: 585–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu CL, Lee SS, Tsai CH, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin increases cell attachment, proliferation and collagen-related protein expression of human osteoblasts. Aust Dent J 2012; 57: 207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Pinto NR, Pereda A, et al. The impact of the centrifuge characteristics and centrifugation protocols on the cells, growth factors, and fibrin architecture of a leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF) clot and membrane. Platelets 2018; 29: 171–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dohan Ehrenfest DM. How to optimize the preparation of leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF, Choukroun’s technique) clots and membranes: introducing the PRF Box. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2010; 110: 275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thorn JJ, Hansen HS, Specht L, et al. Osteoradionecrosis of the jaws: Clinical characteristics and relation to the field of irradiation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000; 58: 1088–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koga DH, Salvajoli JV, Alves FA. Dental extractions and radiotherapy in head and neck oncology: review of the literature. Oral Dis 2008; 14: 40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]