Abstract

Regulatory T-cells (Tregs) may exert a neuroprotective effect on ischemic stroke by inhibiting both inflammation and effector T-cell activation. Transplantation of human bone marrow-derived stem cells (BMSCs) in ischemic stroke affords neuroprotection that results in part from the cells’ anti-inflammatory property. However, the relationship between Tregs and BMSCs in treatment of ischemic stroke has not been fully elucidated. Here, we tested the hypothesis that Tregs within the BMSCs represent active mediators of immunomodulation and neuroprotection in experimental stroke. Primary rat neuronal cells were subjected to an oxygen-glucose deprivation and reperfusion (OGD/R) condition. The cells were re-perfused and co-cultured with Tregs and/or BMSCs. We detected a minority population of Tregs within BMSCs with both immunocytochemistry (ICC) and flow cytometry identifying cells expressing phenotypic markers of CD4, CD25, and FoxP3 protein. BMSCs with the native population of Tregs conferred maximal neuroprotection compared to the treatment conditions containing 0%, 10%, and 100% relative ratio Tregs. Increasing the Treg population resulted in increased IL6 secretion and decreased FGF-β secretion by BMSCs. This study shows that a minority population of Tregs exists within the therapeutic BMSC population, which serves as robust mediators of the immunomodulatory and neuroprotective effect provided by BMSC transplantation.

Keywords: Adaptive immunity, ischemia, foxp3, immunotherapy

Introduction

Stroke is the second leading cause of death worldwide and the third major cause of disability in adults, and ischemic stroke accounts for between 70 and 80% of all strokes.1 Ischemic stroke is an occlusion of an artery supplying a specific area of the brain leading to acute loss of blood flow and oxygen to that area, resulting in cell death. The timeline following infarction is characterized by a phased response of cell death, inflammation, and injury resolution.2,3 Disruption of the neurovascular unit (NVU) has been implicated as a pivotal stroke pathology, with the vulnerable cells in the infarct and peri-infarct zone as key component of NVU that undergo apoptosis and necrosis, releasing non-cell autonomous “help me” signals into the parenchyma.4 Excitatory neurotransmitters are released and depolarize cells in the peri-infarct region, which triggers cellular cascades that eventually leads to further cell death via apoptosis among other degenerative signaling pathways.4 New treatments aim to rescue the cells in the peri-infarct region.5,6

Rescue of the peri-infarct region has been closely linked to the process of inflammatory cascades and homeostasis. The brain’s innate immune system, consisting primarily of microglia, is immediately activated following ischemic injury. Subsequently, the systemic adaptive immune system, consisting of T-lymphocytes, homes to the infarcted region to induce apoptosis of damaged cells. This initial immune response evolved to dispose of cellular debris and attack invading pathogens, but prolonged over-activation is known to be detrimental to neurons in the peri-infarct region.7 Bone marrow cells have been shown to migrate to the peri-infarct area in response to ischemic stroke, providing a neuroprotective effect.8 Similarly, exogenous delivery of bone marrow-derived stem cells (BMSCs) has been shown to confer neuroprotection against stroke.9–11 BMSCs have been demonstrated to act both locally and systemically to attenuate deleterious immune responses, providing a significant degree of neuroprotection.11–14 Careful attenuation of the immune response after stroke affords neuroprotective effects with stem cells playing an active role as potent mediator of immunomodulation, which is one of the principle mechanisms by which they exert a neuroprotective effect. However, it is not yet fully understood how stem cell treatments modulate the immune system, and the effect is likely multifactorial in nature.

BMSCs are a well-characterized cell population consisting of adherent mononuclear cells extracted from the bone marrow.15 While consisting primarily of stem cells, it is possible that the harvested and isolated BMSC population contains more mature cell types that act to prevent deleterious inflammation. In vivo, bone marrow stem cells normally mature into either a myeloid or lymphoid precursor, from which all peripheral blood cells are derived. Cells of the adaptive immune system have recently been identified as important initiators and regulators of the immune system post ischemic stroke.2,16–21

Specifically, a small subset of T-lymphocytes, the regulatory T-cells (Tregs), are potent initiators of anti-inflammatory effects.16,22 It is known that Tregs are reduced in number and functional capacity in post-stroke homeostasis.23 Introduction of Tregs into post-stroke brain has been shown confer neuroprotection by stabilizing the blood–brain barrier and promoting anti-inflammatory signaling processes.17,24–28 There exist also data providing compelling evidence that FoxP3, a critical transcription factor responsible for Treg maturation,29,30 is expressed in mesenchymal stem cells.28 Tregs found within BMSCs would be of significant importance in understanding the anti-inflammatory effect of therapeutic BMSC transplantation in stroke.

In the present study, we investigated BMSCs for the presence Tregs and found a distinct subpopulation of CD4+/CD25+/FoxP3+ Tregs. We found that the neuroprotective effect of Tregs and BMSCs in co-culture varied in a ratio-dependent manner. We found that Tregs were capable of minimizing stem cell production of IL-6, a pro-inflammatory cytokine32 and that increasing the concentration of Tregs inhibits BMSC secretion of FGF-β, a cytokine related to BMSC proliferation and differentiation.33,34 We showed the ratio of Tregs found natively in BMSCs is optimally adapted to provide the maximum neuroprotective benefit of stem cell treatment after ischemic stroke.

Materials and methods

Animal experiments

All experiments involving animals were conducted under the supervision and approval of our university’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). All experimental procedures were consistent with the NIH Guide for The Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the United States Animal Welfare Act, the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and our university’s IACUC Principles and Procedures. The experiments were reported in compliance with the Animal Research: Reporting in Vivo Experiments guidelines for how to report animal experiments.

Cell culture

Primary rat neuronal cells (PRNCs) were cultured in vitro as described previously.35 A total of 80,000 E18 Primary rat neural cells (PRNCs) (BrainBits, Springfield, IL, USA) were suspended in 400 µL neural medium (NbActive 4, BrainBits) containing 2 mM L-glutamine and 2% B27 and grown in poly-l-lysine-coated 96-well plates at 37℃. E18 primary rat neural cells consisted of neurons and glial cells, which included astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes, in concentrations resembling in vivo conditions. After the cells reached confluence, they were subjected to an oxygen-glucose deprivation and reperfusion (OGD/R) condition (5% CO2, 95% N2) for 90 min. The cells were re-perfused and co-cultured with Tregs and/or BMSCs, at concentrations of either 800, 8000, or 80,000 cells per well, for three more days. The co-culture was created by directly inoculating the culture medium with the appropriate number of BMSCs and/or Tregs.

ICC

After cell culture was completed, cells were fixed for 30 min in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with a 0.1% tween solution, and incubated with fluorescent antibodies with affinity for CD4, CD25, and FoxP3 at the manufacturer’s recommended dilutions. Cells in suspension were concentrated by centrifugation and mounted on glass slides for imaging. Measurement of cell viability was performed using Hoechst nuclear stain (33342, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA).35 Viable cell counts were calculated in 10 randomly selected areas (1 mm2, n = 10) to quantify cell viability. Stained cells were digitally captured under microscope (20×). Ten pictures (approximately 100 cells/picture) for each condition were acquired and five pictures were randomly selected and cells were counted for each individual treatment condition. Confocal microscopy was used to image certain subgroups at higher magnification (20×, 80×, and 180×).

Flow cytometry

Cells were manually dissociated into a single-cell suspension and then fixed for 30 min in 4% paraformaldehyde. The cells were divided into separate tubes for all single antibody controls and immunoglobulin isotype control. Fixed cells were incubated with fluorescent antibodies specific to cell surface markers CD4 and CD25. Then, cells were permeabilized and incubated with fluorescent antibody to FoxP3. Finally, the labeled cell suspension was analyzed using an analytical flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The flow cytometer output was gated by a blinded researcher to appropriately exclude cellular debris and contaminants by using forward scatter and side scatter parameters. Target fluorescence thresholds were set to exclude the isotype control group, so to quantify only the specific fluorescence.

Treg isolation and depletion

Tregs were harvested from spleens from healthy, wild-type, male adult (three months old) C57BL/6 mice using a previously described magnetic sorting technique.25 Splenic tissue was manually dissociated and anti-CD4 and CD25 antibodies were used to label Tregs. The bound antibodies were then conjugated with magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Magnetically labeled cells were isolated by passing the cell suspension through a column containing magnetic metal substrate. First, non-CD4+ cells were depleted using a depletion column. Then, CD25+ positive cells were sorted from the CD4+-enriched solution, resulting in a CD4+/CD25+ cell population of Tregs. Tregs were isolated on the same day as the start of cell culture to avoid any freeze–thaw cycles and associated damage (Figure 1). Native Tregs were depleted from BMSCs using the same magnetic bead approach. However, instead of using the purified Treg population in our experimental culture, we used the cell population that remained after Treg isolation, which consisted of Treg-depleted BMSCs.

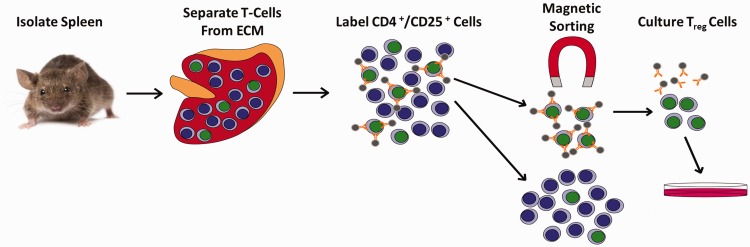

Figure 1.

Treg magnetic cell isolation procedure. Whole spleens were isolated from mice and manually dissociated into a single-cell solution to remove extracellular matrix (ECM). The solution was passed through a strainer and then incubated with magnetic bead conjugated antibodies. Labeled cells were then passed through a magnetic field with metal beads. Non-CD4+ cells were depleted from the solution and CD4+/CD25+ cells were sorted from the remaining solution to yield CD4+/CD25+ Tregs.

ECM: extracellular matrix.

Measurement of extracellular cytokines: IL-6, FGF-β

After OGD/R, culture medium was centrifuged at 3000g for 15 min and supernatant was collected and frozen at −80℃. The supernatant was later processed and analyzed using ELISA kits specific to interleukin-6 (IL-6) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) or fibroblast growth factor-beta (FGF-β) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) with absorbance measured at 450 nm on a Synergy HT plate reader (Bio-Tex Inc., Houston, TX, USA).

Statistics

Randomization and blinding of investigators were strictly followed throughout the experimental procedures. A two-sample t-test was used to compare two independent groups. For categorical independent variables with more than one dependent continuous variable, a one-way ANOVA test was used to determine significance. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical tests were conducted using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). The sample size (eight replicates) was based on our previous study35 allowing rigorous testing of cultured cells for recognizing a 25% statistically significant difference between treatments and controls. All data were initially analyzed for normal distribution, which revealed normally distributed data points, but we excluded a few data points that were two standard deviations away from the mean all in the final analyses.

Results

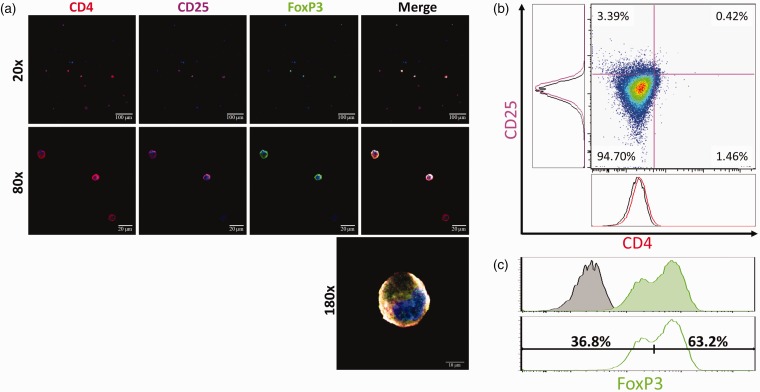

Tregs were identified in BMSCs

CD4+/CD25+/FoxP3+ triple-positive cells were imaged using a scanning laser confocal microscope (Figure 2(a)). Tregs were sparsely detected, but clearly visualized as triple-positive cells with morphology consistent with a lymphoid lineage (Figure 2(a)). Next, the presence of triple-positive Tregs was quantified with flow cytometry. CD4 and CD25, surface markers for Tregs, were expressed in a small subpopulation of BMSCs (1.88% and 3.81%, respectively) (Figure 2(b)). FoxP3 was positively expressed in 63.2% of BMSCs. CD4+/CD25+ cells made up 0.44% of the total cell population, and FoxP3 expression was identified in 95.5% of CD4+/CD25+ cells. Therefore, CD4+/CD25+/FoxP3+ triple-positive Tregs constituted 0.42% of the total cell population (Figure 2(c)).

Figure 2.

A subpopulation of cells expressing protein markers characteristic of Tregs is identified in BMSCs. (a) Fluorescent antibody labeling with CD4 (red), CD25 (magenta), and FoxP3 (green) shows specificity in a subpopulation of cells, demonstrating the presence of Tregs as a distinct subpopulation in BMSCs. (b) CD4 and CD25 were expressed in a small subpopulation of BMSCs (1.46% and 3.39%, respectively). (c) FoxP3 fluorescence in the stained sample (green) shows bimodal distribution and a relatively large delta compared to the unstained control (black). Bimodal distribution suggests that there is a FoxP3+ and a FoxP3-subpopulation in BMSCs. The bimodal FoxP3 histogram was analyzed to quantify the possible FoxP3+ subpopulation of BMSCs. The bimodal histogram was separated into a right-shifted FoxP3+ population (63.2%) and left-shifted FoxP3-population (36.8%).

Native population of Tregs is neuroprotective

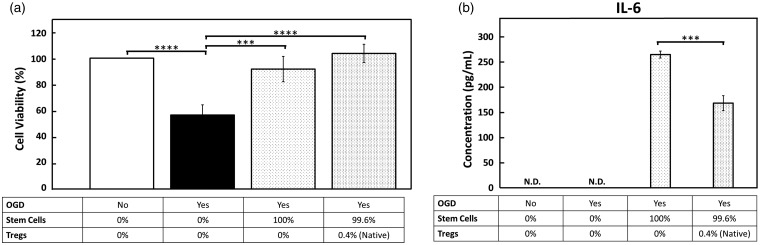

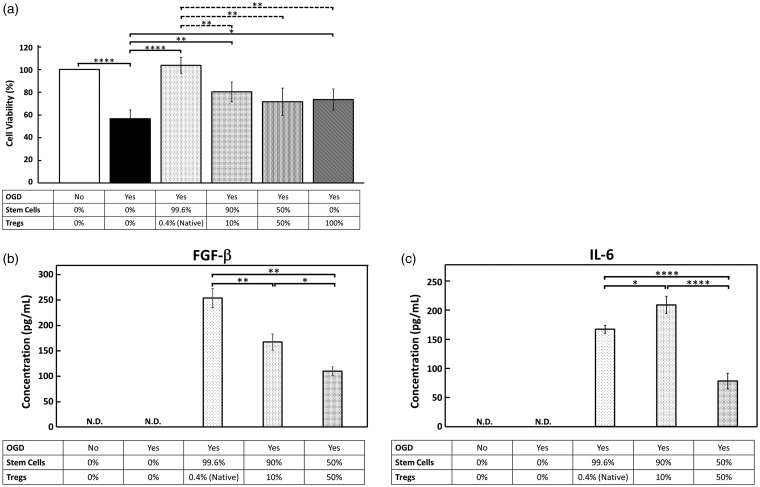

We showed that OGD/R significantly (p < 0.0001) reduced the number of surviving neurons to 56.6% of the control. Treatment with BMSCs protected the ischemic neurons, and significantly increased survival from 56.6% to 103.7% of the control (p < 0.0001). Removal of the native population of Tregs from BMSCs relatively decreased the neuroprotective effect of treatment compared to BMSCs with native Tregs, but there was no statistically significant difference between these two BMSC groups (p = 0.0659) (Figure 3(a)). When BMSCs were supplemented with exogenous Tregs isolated from mouse spleens, the neuroprotective effect was attenuated. At a 1:10 ratio of Tregs to BMSCs, neuron survival was significantly reduced compared to the native BMSC population (p < 0.05). At a 1:1 ratio of Tregs to BMSCs, the neuroprotective effect was also significantly reduced compared to the native cell population (p < 0.05) (Figure 4(a)). Interestingly, Tregs alone without BMSCs exerted significant neuroprotection (p < 0.05) (Figure 4(a)).

Figure 3.

The native population of Tregs in BMSCs relatively increases neuroprotection and reduces IL-6 production. (a) The vertical axis displays the viable neuron (MAP2+) cell count normalized to the control group (black) as a percentage. OGD/R condition results in significant decrease in cell viability (black vs. white bar). BMSCs depleted of Tregs confer neuroprotection after OGD/R and BMSC treatment with native population of Tregs increases cell viability. (b) IL-6 secretion, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, by BMSCs was measured via ELISA. IL-6 secretion was significantly increased by depleting BMSC cell transplant of Tregs.

OGD: oxygen-glucose deprivation; IL-6: interleukin-6.

Figure 4.

Increasing the ratios of Tregs in BMSC treatment after OGD/R decreases neuroprotection capacity of Tregs. (a) Treatment with BMSCs and the native ratio of Tregs confers significant neuroprotection after OGD/R. Supplemental Tregs in ratios of 1:10 and 1:1 Tregs: BMSCs show significant reduction in neuroprotection relative the native 1:100 ratio. (b) FGF-β, a cytokine secreted by BMSCs promoting proliferation and differentiation, was measured by ELISA. Increasing the ratio of Tregs correlates to a dose-dependent decrease in FGF-β secretion. (c) BMSC IL-6 secretion was measured by ELISA. IL-6 production was significantly increased in the 1:10 Treg ratio treatment group, while it was significantly decreased in the 1:1 ratio treatment group.

OGD: oxygen-glucose deprivation; IL-6: interleukin-6: FGF-β: fibroblast growth factor-beta.

BMSC cytokine secretion is altered by Tregs

BMSC IL-6 and FGF-β secretion was measured by ELISA and the results from each experimental group were compared to each other, measuring relative changes in cytokine secretion as a function of an increasing Treg concentration. IL-6 concentration in the cell culture supernatant was significantly decreased in the treatment group with native Treg population as compared to the Treg-depleted BMSCs (p < 0.05) (Figure 3(b)). BMSCs with 1:10 ratio of supplemental Tregs showed significant increase in IL-6 secretion relative to the native Treg treatment group (p < 0.05). When the Treg population reached a 1:1 ratio of Tregs to BMSCs, the IL-6 concentration was significantly lower than the native BMSC group (p < 0.05), and had the lowest observed IL6 concentration of all groups (p < 0.05) (Figure 4(c)).

FGF-β concentration varied inversely with the Treg concentration in the treatment groups. The two treatment groups with supplemental Tregs both showed a significant reduction in FGF-β concentration as compared to the native BMSC group (p < 0.05) (Figure 4(b)). We measured the basal levels of FGF-β and IL-6 produced by BMSCs without the influence of OGD, Tregs, or neuronal cells. IL-6 was found in the cell culture supernatant at a concentration of 502 ± 12.2 pg/mL, and FGF-β was not detected.

Discussion

We found that BMSCs contain a minority population of Tregs, a cell population that modulates the therapeutic benefit of BMSCs following ischemic stroke. We positively identified Tregs in BMSCs, and observed a neuroprotective effect that was dependent on Treg concentration. Increasing or decreasing the Treg population ratio decreased the neuroprotective effect of BMSC treatment. We found that the ideal ratio of Tregs to BMSCs was the ratio found natively in BMSCs. As a proof-of-concept in demonstrating the active role of these immune cells within the BMSC population in affording immunoregulatory and neuroprotective function, Tregs alone were observed to exert therapeutic effects against experimental stroke, which support accumulating evidence of the robust beneficial effects of adoptive Treg transfer in stroke.24,26,28 These results warrant tandem investigations of BMSCs which represent a heterogenous stem cell population, as opposed to pure Treg isolation, as equally effective donor cells for transplantation therapy in stroke.

We also found that cytokine secretion related to BMSC immunomodulation, differentiation, and survival was dependent on the proportion of Tregs. Our ELISA assay was specific to assess BMSCs, in that all cytokines measured were those representing the BMSC secretome that was modulated by increasing concentrations of Tregs. FGF-β promotes beneficial differentiation and survival of BMSCs and was produced at lower levels with increasing numbers of Tregs in co-culture. IL-6 is a cytokine implicated for its role in promoting inflammation, which is generally regarded as an impediment to neuroprotection. However, equally compelling evidence suggests that IL-6 is crucial for promoting angiogenesis after stroke.36,37 We found that varying numbers of Tregs significantly altered IL-6 production, possibly reflecting the altered homeostatic equilibrium of competing anti-inflammation and angiogenesis effects of IL-6. These findings together showed that while the Treg population is a small fraction of therapeutic BMSC transplants, they exerted a powerful effect on stem cell function and consequently their ability to provide neuroprotection. Prior studies have demonstrated the importance of Tregs and BMSCs as independent effectors of neuroprotection post-stroke25,26 and that Tregs are decreased after stroke23 (Figure 5). We showed that Tregs in conjunction with BMSC transplants are a double-edged sword; Tregs prevented deleterious inflammation but also possibly inhibited the neuroprotective role of BMSCs after stroke if the ratio of Tregs to BMSCs was increased.

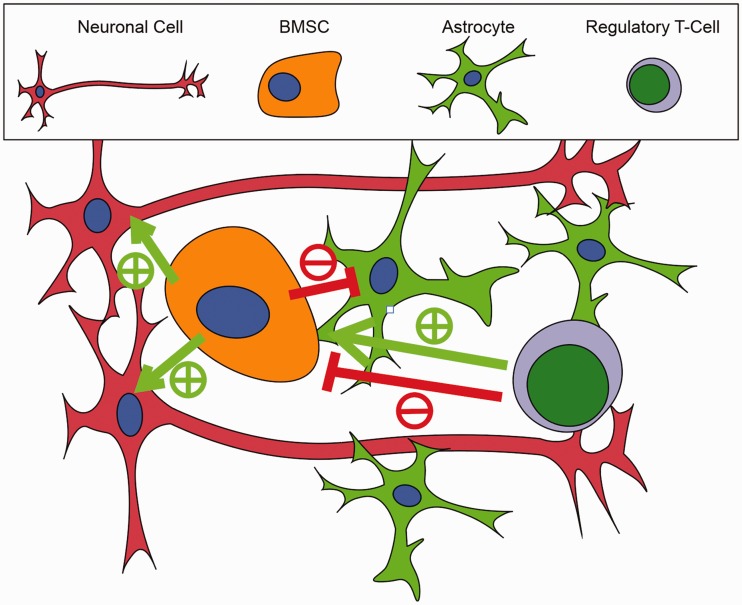

Figure 5.

A graphical depiction of cell culture is depicted showing the interaction between Tregs, BMSCs, and neural cells (astrocytes and neurons). BMSCs are shown to be neuroprotective by promoting neuron survival (green arrows, +) and attenuating astrocyte activation (red arrows, −). Tregs are shown to potentially have a dualistic, concentration-dependent effect on BMSCs. At the native concentration, Tregs relatively decrease BMSC IL-6 production, a potentially deleterious pro-inflammatory cytokine. BMSC FGF-β production, a cytokine related to BMSC survival, proliferation, and differentiation, is reduced in a concentration-dependent manner with Treg co-culture.

BMSC: bone marrow-derived stem cell.

We positively detected the three classic markers for Tregs, and found somewhat unexpected results. The FoxP3+ cells we found in the BMSCs comprised a higher percentage than we expected. CD4 and CD25, proteins expressed in less than 4% of our BMSCs, are proteins located in the cell membrane with extracellular epitopes. FoxP3 is an intracellular soluble transcription factor protein normally found in the nucleus. Techniques for specific identification of nuclear antigens were used to minimize non-specific staining, but it is possible that we observed false-positives in our experimental sample. However, this result is consistent with a previous study,31 and it is possible that FoxP3 is expressed in a significant proportion of BMSCs, acting as an anti-inflammatory signaling mediator. FoxP3-expressing BMSCs may have a greater anti-inflammatory effect due to increased transcriptional regulation of FGF-β and IL-10 by FoxP3.29,30 The present study aimed to uncover the role of CD4+/CD25+/FoxP3+ Tregs, and future studies will more closely examine the role of the FoxP3+ BMSCs and their possible anti-inflammatory capacity in ischemic stroke.

While not significantly detracting from our conclusions, there are limitations to this study. The cell population percentages reported here suggest that our Treg cell population was pure. While Tregs were enriched in our cell population by magnetic sorting, there were other splenocytes included in our cell culture that were not accounted for. Tregs were considered to be the predominant cell type in the enriched splenocytes, and the measured effects were therefore likely attributed to Tregs. It is also possible that the cells expressing Treg markers within the BMSCs were an immature cell type not functionally equivalent to the adult Tregs isolated from the spleen. Future studies will investigate the functional differences between Tregs obtained from BMSCs and those obtained from spleens.

This study is a step towards understanding the interaction between Tregs and BMSC transplants after stroke and has informed future studies. It has been shown that numbers of circulating T-lymphocytes vary within the post-stroke period, and implanted BMSCs are constantly changing in composition and function as a function of time. Modulation of the Treg population may have a variety of effects dependent on the timing of cell transplantation after stroke. Characterizing the dynamics of inflammation following ischemic stroke will be critical to determining the optimal post-stroke period to transplant stem cells and Tregs. This study analyzed the response in the acute phase following stroke, and future studies will establish the relationship between Tregs and BMSCs in the sub-acute and chronic phases of recovery. Moreover, a better understanding of the mechanism of Treg concentrations in BSMCs in in vivo stroke models will likely further optimize transplant functional outcomes. Notwithstanding, our study supports the concept of the inclusion of Tregs in the NVU in assessing stroke pathology and its treatment.

BMSC transplant is a powerful treatment following ischemic stroke. Modulation of the immune system is a key mechanism by which BMSCs confer neuroprotection. This study showed that a minority population of Tregs exists within the therapeutic BMSC population, and those Tregs are independent modulators of the immunomodulating effect provided by BMSC transplantation. The ratio of Tregs found naturally in BMSCs correlates with the highest level of neuroprotection after ischemic stroke.

Acknowledgements

Part of this manuscript was presented at the American Society for Neural Therapy and Repair 24th Annual Conference, 27–29 April 2017, Clearwater, Florida.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: CVB is funded by NIH R01NS071956, NIH R01 NS090962, NIH R21NS089851, NIH R21 NS094087, and VA Merit Review I01 BX001407.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author’ contributions

EGN, SAA, YK, XJ, and CVB made a substantial contribution to the concept and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data. EGN and CVB drafted the article and revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Research statement

Research materials, including data, reported in this study are stored at the Center of Excellence for Aging and Brain Repair at the University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine, Tampa, Florida, USA, and can be easily accessed by contacting Cesario V Borlongan.

References

- 1.Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, et al. Stroke epidemiology: a review of population-based studies of incidence, prevalence, and case-fatality in the late 20th century. Lancet Neurol 2003; 2: 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An C, Shi Y, Li P, et al. Molecular dialogs between the ischemic brain and the peripheral immune system: dualistic roles in injury and repair. Prog Neurobiol 2014; 115: 6–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevens SL, Bao J, Hollis J, et al. The use of flow cytometry to evaluate temporal changes in inflammatory cells following focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Brain Res 2002; 932: 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doyle KP, Simon RP, Stenzel-Poore MP. Mechanisms of ischemic brain damage. Neuropharmacology 2008; 55: 310–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarkson AN, Huang BS, Macisaac SE, et al. Reducing excessive GABA-mediated tonic inhibition promotes functional recovery after stroke. Nature 2010; 468: 305–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamorro Á, Dirnagl U, Urra X, et al. Neuroprotection in acute stroke: targeting excitotoxicity, oxidative and nitrosative stress, and inflammation. Lancet Neurol 2016; 15: 869–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin R, Yang G, Li G. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: role of inflammatory cells. J Leukoc Biol 2010; 87: 779–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borlongan CV. Bone marrow stem cell mobilization in stroke: a ‘bonehead’ may be good after all!. Leukemia 2011; 25: 1674–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vahidy FS, Rahbar MH, Zhu H, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of bone marrow–derived mononuclear cells in animal models of ischemic stroke. Stroke 2016; 47: 1632–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tajiri N, Acosta S, Glover LE, et al. Intravenous grafts of amniotic fluid-derived stem cells induce endogenous cell proliferation and attenuate behavioral deficits in ischemic stroke rats. PLoS One 2012; 7: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toyoshima A, Yasuhara T, Kameda M, et al. Intra-arterial transplantation of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells mounts neuroprotective effects in a transient ischemic stroke model in rats: analyses of therapeutic time window and its mechanisms. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0127302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoo SW, Chang DY, Lee HS, et al. Immune following suppression mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in the ischemic brain is mediated by TGF-β. Neurobiol Dis 2013; 58: 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu Y, He M, Zhou X, et al. Endogenous IL-6 of mesenchymal stem cell improves behavioral outcome of hypoxic-ischemic brain damage neonatal rats by supressing apoptosis in astrocyte. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 18587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopez-Verrilli MA, Caviedes A, Cabrera A, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes from different sources selectively promote neuritic outgrowth. Neuroscience 2016; 320: 129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, et al. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell 2001; 105: 369–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petrovic-Djergovic D, Goonewardena SN, Pinsky DJ. Inflammatory disequilibrium in stroke. Circ Res 2016; 119: 142–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liesz A, Kleinschnitz C. Regulatory T cells in post-stroke immune homeostasis. Transl Stroke Res 2016; 7: 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopes Pinheiro MA, Kooij G, Mizee MR, et al. Immune cell trafficking across the barriers of the central nervous system in multiple sclerosis and stroke. Biochim Biophys Acta – Mol Basis Dis 2016; 1862: 461–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arunachalam P, Ludewig P, Melich P, et al. CCR6 (CC Chemokine Receptor 6) is essential for the migration of detrimental natural interleukin-17–producing γδ T cells in stroke. Stroke 2017; 48: 1957–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liesz A, Zhou W, Mracskó É, et al. Inhibition of lymphocyte trafficking shields the brain against deleterious neuroinflammation after stroke. Brain 2011; 134: 704–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yilmaz G. Role of T lymphocytes and interferon-gamma in ischemic stroke. Circulation 2006; 113: 2105–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu L, Xiong X, Zhang H, et al. Distinctive effects of T cell subsets in neuronal injury induced by cocultured splenocytes in vitro and by in vivo stroke in mice. Stroke 2012; 43: 1941–1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruhnau J, Schulze J, von Sarnowski B, et al. Reduced numbers and impaired function of regulatory T cells in peripheral blood of ischemic stroke patients. Mediators Inflamm 2016; 2016: 2974605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia Y, Cai W, Thomson AW, et al. Regulatory T cell therapy for ischemic stroke: how far from clinical translation? Transl Stroke Res 2016; 7: 415–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liesz A, Suri-Payer E, Veltkamp C, et al. Regulatory T cells are key cerebroprotective immunomodulators in acute experimental stroke. Nat Med 2009; 15: 192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brea D, Agulla J, Rodríguez-Yáñez M, et al. Regulatory T cells modulate inflammation and reduce infarct volume in experimental brain ischaemia. J Cell Mol Med 2014; 18: 1571–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li P, Mao L, Liu X, et al. Essential role of program death 1-ligand 1 in regulatory T-cell-afforded protection against blood-brain barrier damage after stroke. Stroke 2014; 45: 857–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li P, Gan Y, Sun B-L, et al. Adoptive regulatory T-cell therapy protects against cerebral ischemia. Ann Neurol 2013; 74: 458–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol 2003; 4: 330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science 2003; 299: 1057–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sundin M, D'Arcy P, Johansson CC, et al. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells express FoxP3. J Immunother 2011; 34: 336–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Haan S, et al. Principles of interleukin (IL)-6-type cytokine signalling and its regulation. Biochem J 2003; 374: 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsutsumi S, Shimazu A, Miyazaki K, et al. Retention of multilineage differentiation potential of mesenchymal cells during proliferation in response to FGF. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001; 288: 413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kunath T, Saba-El-Leil MK, Almousailleakh M, et al. FGF stimulation of the Erk1/2 signalling cascade triggers transition of pluripotent embryonic stem cells from self-renewal to lineage commitment. Development 2007; 134: 2895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaneko Y, Pappas C, Tajiri N, et al. Oxytocin modulates GABAAR subunits to confer neuroprotection in stroke in vitro. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 35659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grønhøj MH, Clausen BH, Fenger CD, et al. Beneficial potential of intravenously administered IL-6 in improving outcome after murine experimental stroke. Brain Behav Immun 2017; 65: 296–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gertz K, Kronenberg G, Kälin RE, et al. Essential role of interleukin-6 in post-stroke angiogenesis. Brain 2012; 135: 1964–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]