We thank Rostoker et al.1 for their comment on our paper.2 We acknowledge that our database lacks several clinical factors that may relate to the patients’ prognoses, including those pointed out by Rostoker et al. Like any other observational studies, our analysis was also subject to unknown confounders. Although randomization is an ideal method to control for confounding, we took an alternative approach—an instrumental variable (IV) analysis—that can deal with even unmeasured confounders. This sophisticated statistical technique enabled us to confirm that patients treated with long-acting erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA) had worse prognoses. Notably, the IV of our study, namely, the facility-level preference for the long-acting ESA, was strongly predictive of the type of ESA prescribed for individual patients (F-statistic in the first stage of the two-stage least squares regression: 35,549 [>10]). As discussed in our paper,2 it was unlikely that the facility-level preference for the long-acting ESA had a direct effect on the outcome, but it had an indirect effect only through the choice of ESA, especially under the medical insurance system for dialysis therapy in Japan. Therefore, although our study was observational, we think the influence of confounders on the observed association was minimal.

We deeply appreciate the comments by Tanaka et al.3 and Hanafusa et al.4 We agree that patients taking long-acting ESA could have higher ESA resistance given that they received relatively high doses of ESA compared with those taking short-acting ESA. They argued that higher ESA resistance and higher ESA dose in those treated with long-acting ESA contributed to their worse prognoses, despite our effort to control for such confounding using the IV analysis and facility-level analysis.

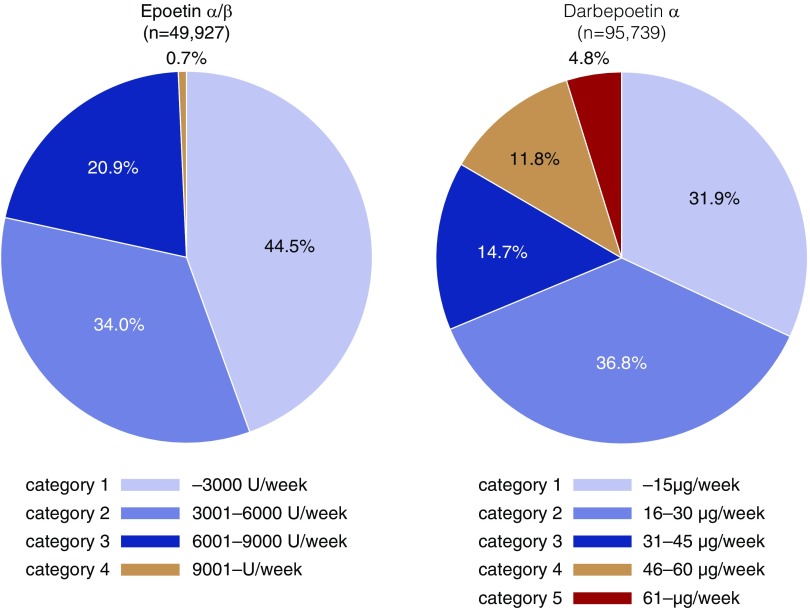

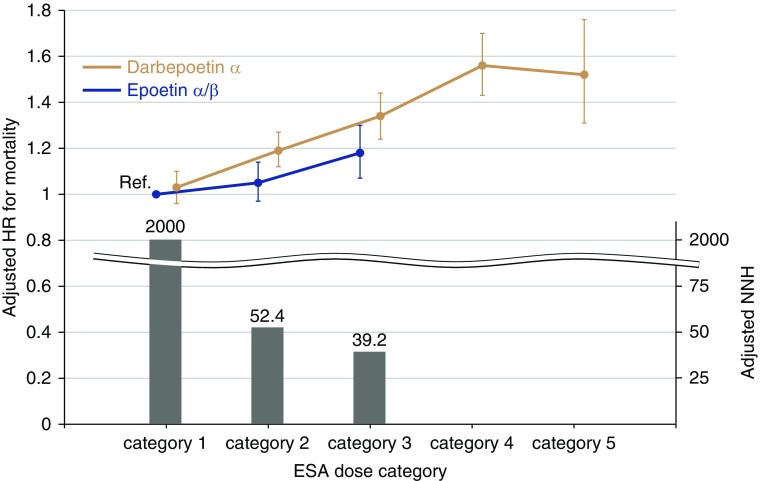

Accordingly, we have performed several additional analyses in which we accounted for the dose conversion ratio (epoetin-α/β [EPO]/darbepoetin-α [DPO] ratio=200). We defined ESA dose categories (category 1−5) according to this conversion ratio (Figure 1). There were few patients taking EPO in category 4 (0.7%), whereas a total of 16.6% of those taking DPO were in category 4 or 5. Here, we compared the risk of death between EPO and DPO in each ESA dose category. Similarly to the original version of our stratified analysis,2 the risk difference became greater in higher ESA dose categories. Although there was no significant risk difference between DPO and EPO in category 1, patients treated with DPO had a 1.38-fold higher risk of death in category 3 (Figure 2, Table 1). Given the low values of 2 year–adjusted numbers needed to harm for all-cause death in categories 2 and 3 (52.4 and 39.2, respectively), the between-drug difference in these categories is clinically relevant. Notably, the mean ESA dose was similar between the two groups in each ESA dose category according to the dose conversion ratio. The mean hemoglobin level was also similar between groups.

Figure 1.

Higher doses of ESA are prescribed for patients taking DPO-α (i.e., category 4 and 5) compared with those taking EPO-α/β. The range of ESA doses in each category is based on the dose conversion ratio (EPO/DPO=200).

Figure 2.

Mortality rates are elevated in patients treated with DPO-α except for those in ESA dose category 1. The Cox proportional hazards model was adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, predialysis systolic BP, dialysis duration, dialysis vintage, single-pool Kt/V, diabetes mellitus, a history of cardiovascular diseases, laboratory data (albumin, urea nitrogen, C-reactive protein, hemoglobin, ferritin, albumin-adjusted calcium, phosphate, and parathyroid hormone), standardized erythropoietin resistance index, and facility indicators. The patients taking EPO-α/β in category 1 were treated as a reference group. The bar graph denotes the adjusted 2-year numbers needed to harm for all-cause death, which was calculated from the reciprocal of the adjusted absolute risk difference between patients taking EPO-α/β and those taking DPO-α in each ESA dose category. HR, hazard ratio; NNH, number needed to harm; Ref., reference.

Table 1.

Adjusted hazard ratio for all-cause death stratified by ESA dose category

| ESA Dose Category | ESA | n | HR (95% CI) | P Value | Mean (SD) ESA Dose | Mean (SD) Hb (g/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category 1 | EPO-α/β | 13,637 | Reference | — | 2106 (809) U/wk | 10.8 (1.0) |

| DPO-α | 19,202 | 1.03 (0.96 to 1.10) | 0.42 | 11.3 (2.8) μg/wk | 10.9 (1.0) | |

| Category 2 | EPO-α/β | 10,394 | Reference | — | 4927 (739) U/wk | 10.5 (1.0) |

| DPO-α | 21,814 | 1.24 (1.15 to 1.33) | <0.001 | 24.2 (4.9) μg/wk | 10.6 (1.1) | |

| Category 3 | EPO-α/β | 5907 | Reference | — | 8807 (515) U/wk | 10.0 (1.2) |

| DPO-α | 8676 | 1.38 (1.21 to 1.59) | <0.001 | 40.0 (0.4) μg/wk | 10.2 (1.3) |

The model was adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, predialysis systolic BP, dialysis duration, dialysis vintage, single-pool Kt/V, diabetes mellitus, a history of cardiovascular diseases, laboratory data (albumin, urea nitrogen, C-reactive protein, hemoglobin, ferritin, albumin-adjusted calcium, phosphate, and parathyroid hormone), standardized erythropoietin resistance index, and facility indicators. HR, hazard ratio; Hb, hemoglobin.

As a sensitivity analysis, we compared the mortality risk of all patients taking EPO with those taking DPO whose prescribed DPO doses were 40 μg/wk or less. Patients treated with DPO again had a 15% higher risk of all-cause death (Table 2). The mean ESA dose and mean hemoglobin level were similar between the groups. These additional findings clearly indicate that the increased risk of death in patients taking DPO was not solely derived from their higher ESA resistance and higher ESA dose compared with patients taking EPO.

Table 2.

Adjusted hazard ratio for all-cause death excluding those treated by high doses of DPO-α

| ESA | n | HR (95% CI) | P Value | Mean (SD) ESA Dose | Mean (SD) Hb (g/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPO-α/βa | 30,135 | Reference | — | 4547 (2787) U/wk | 10.5 (1.1) |

| DPO-αb | 49,670 | 1.15 (1.11 to 1.20) | <0.001 | 22.0 (10.8) μg/wk | 10.7 (1.1) |

HR, hazard ratio; Hb, hemoglobin.

All patients treated with EPO-α/β, regardless of doses prescribed.

Patients treated with DPO-α whose prescribed doses were 40 μg/wk or less.

As Tanaka et al. and Hanafusa et al. suggested, it is true that physicians prescribed high doses of long-acting ESA relative to short-acting ESA (i.e., category 4 and 5), especially for patients with high ESA resistance. However, this practice pattern was driven by the current drug labels of ESA in Japan, which allow physicians to prescribe high doses of long-acting ESA. Notably, these labels have been approved by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA). We sincerely do hope that the PMDA limits the dose of long-acting ESA based on our scientific findings, including facility-level analysis and this stratified analysis by ESA dose, because this practice pattern is considered to accentuate the toxicity of ESA, which was first suggested by the Normal Hematocrit Study over 20 years ago.5

Disclosures

Dr. Sakaguchi reports grants and personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; grants and personal fees from Kissei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; and grants and personal fees from Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd.; outside of the submitted work. Dr. Hamano reports grants and personal fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; grants, personal fees, and other from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; grants and personal fees from Torii Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; grants and personal fees from Kissei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; grants and personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; grants from Terumo Corporation; grants from Fuso Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd.; grants, personal fees, and other from Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd.; grants and personal fees from Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd.; grants and personal fees from Asahi Kasei Pharma Corporation; grants from Eisai Co., Ltd.; other from GlaxoSmithKline KK; personal fees and other from Astellas Pharma Inc.; and grants from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd.; outside the submitted work. Dr. Masakane received honorariums from Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd.; Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; and Kissei Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express heartfelt appreciation to the Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy, the principal investigators of all prefectures, and all personnel and patients at the institutions participating in this survey.

The contents and opinions in this paper are those of the authors only and do not reflect those of the Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Rostoker G, Lepeytre F, Rottembourg J: Analysis of other confounding factors is mandatory before considering that long-acting erythropoiesis stimulating agents are deleterious to dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 1771, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakaguchi Y, Hamano T, Wada A, Masakane I: Types of erythropoietin-stimulating agents and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 1037–1048, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka M, Shinohara K, Ono A, Ikuma M: ESA-resistance may be a potential confounder for mortality among different ESA types. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 1772, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanafusa N, Tsuchiya K: Equivalent doses matters, rather than types. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 1772, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besarab A, Bolton WK, Browne JK, Egrie JC, Nissenson AR, Okamoto DM, et al. : The effects of normal as compared with low hematocrit values in patients with cardiac disease who are receiving hemodialysis and epoetin. N Engl J Med 339: 584–590, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]