Significance Statement

In Canada, access to kidney transplantation requires referral to a transplant center, and selection of patients for transplant is in part a subjective process. The authors determined the incidence of transplant referral among incident patients with ESKD in Canada. Only 17% of incident patients with ESKD were referred within 12 months of starting dialysis, and transplant referral varied more than three-fold between provinces. Factors associated with a lower likelihood of referral included older age, female sex, and receiving dialysis >100 km from a transplant center, but not median household income or nonwhite race. The findings highlight the need to educate health care providers about the medical criteria for kidney transplantation and implement standards for referral, as well as the need for ongoing reporting of referral for transplantation in national registries.

Keywords: kidney transplantation, clinical epidemiology, kidney donation

Abstract

Background

Patient referral to a transplant facility, a prerequisite for dialysis-treated patients to access kidney transplantation in Canada, is a subjective process that is not recorded in national dialysis or transplant registries. Patients who may benefit from transplant may not be referred.

Methods

In this observational study, we prospectively identified referrals for kidney transplant in adult patients between June 2010 and May 2013 in 12 transplant centers, and linked these data to information on incident dialysis patients in a national registry.

Results

Among 13,184 patients initiating chronic dialysis, the cumulative incidence of referral for transplant was 17.3%, 24.0%, and 26.8% at 1, 2, and 3 years after dialysis initiation, respectively; the rate of transplant referral was 15.8 per 100 patient-years (95% confidence interval, 15.1 to 16.4). Transplant referral varied more than three-fold between provinces, but it was not associated with the rate of deceased organ donation or median waiting time for transplant in individual provinces. In a multivariable model, factors associated with a lower likelihood of referral included older patient age, female sex, diabetes-related ESKD, higher comorbid disease burden, longer durations (>12.0 months) of predialysis care, and receiving dialysis at a location >100 km from a transplant center. Median household income and non-Caucasian race were not associated with a lower likelihood of referral.

Conclusions

Referral rates for transplantation varied widely between Canadian provinces but were not lower among patients of non-Caucasian race or with lower socioeconomic status. Standardization of transplantation referral practices and ongoing national reporting of referral may decrease disparities in patient access to kidney transplant.

Among patients with ESKD, transplantation is associated with longer survival, better quality of life, and cost savings compared with treatment with chronic dialysis.1,2 Remarkably, the benefits of transplantation are applicable to most patients with ESKD,2 and only a minority of patients with ESKD have absolute contraindications to transplantation such as active malignancy, uncontrolled infection, active substance abuse, or habitual nonadherence.3,4 An insufficient supply of organs is the primary factor limiting treatment with transplantation, and patients routinely wait on dialysis for 5 or more years for a deceased donor transplant.5 Given these conditions, minimizing disparities in patient access to transplantation has been a challenge for transplant programs worldwide. Implementation of scientifically grounded organ distribution policies on the basis of clinical criteria and ethical norms are essential features of national transplant systems to ensure fairness in access to transplantation among wait-listed patients.6

Referral to a transplant center is a prerequisite for patients treated with dialysis to gain access to the deceased donor transplant waiting list and to access living donor transplantation. In contrast to the strict rules governing the distribution of organs to patients on the waiting list, the referral of patients on dialysis for transplantation is a partially subjective process and there are few safeguards to ensure that patients who will benefit are referred for transplantation. Previous work has documented geographic variation in wait-listing and kidney transplantation.7,8 However, relatively few studies of patient referral for transplantation have been undertaken and understanding is limited by the fact that information about referrals for transplantation is not currently collected in national dialysis or transplant registries.9–11 The available information suggests significant variability in referral for transplantation related to factors such as age, sex, ethnicity, comorbid disease burden, and socio-economic status. Moreover, the likelihood of referral for transplantation may be dependent on physician knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes about transplantation.9–13 Notably, the association of measures of organ supply such as organ donation rates and waiting times for transplantation with referral practices has not been studied.

Deceased donor kidneys are not routinely shared between Canadian provinces and deceased donor rates and waiting times for transplantation are known to vary significantly between provinces.14 The objective of this study was to determine the association of a patient’s province of residence with referral for transplantation. We hypothesized that physician referral practices for transplantation would be influenced by the organ donation rate and waiting times in their province. Specifically, we hypothesized that referrals for transplantation would be lower in provinces with lower organ donation rates and longer waiting times for transplantation because primary nephrologists, who are responsible for transplant referral, may believe their patients have limited opportunities for transplantation in these provinces.

Methods

The study was approved by the University Health Network Research Ethics Board.

Data Sources and Study Population

The Canadian Society of Transplantation kidney work group, in collaboration with the Canadian Organ Replacement Register (CORR), undertook a national study of adult patients (≥18 years) referred for kidney transplantation between June 1, 2010 and May 31, 2013. Data elements collected include date of referral, patient demographics, and the date of initial transplant consultation. A listing of the 12 Canadian transplant centers contributing data to the study is included in Supplemental Table 1.

Data on patients referred for transplantation were linked to data for all incident patients on chronic dialysis captured in CORR from June 1, 2010 to May 31, 2013 using a unique patient identifier. CORR is a pan-Canadian information system managed by the Canadian Institute for Health Information.15,16 CORR collects data from hospital dialysis programs, transplant programs, organ procurement organizations, and independent health facilities to track patients from their first treatment for end-stage organ failure (dialysis or transplantation) to their death. The registry’s data quality and completeness of coverage have been previously reported.16

Patients referred for transplantation during the study period before initiation of chronic dialysis treatment (i.e., pre-emptive transplant referrals) were excluded from the main analysis, because these patients are not captured as incident patients receiving dialysis in CORR before their transplant referral. Although referrals for transplantation were collected for Quebec residents, patients in the province of Quebec were also excluded from the analysis because Quebec privacy laws precluded the submission of patient-level data for incident patients on dialysis to CORR.

Definition of Transplant Referral

The date of transplant referral was defined as the date when a kidney transplant center first received a mailed, faxed, or electronic request for consultation to assess a patient’s candidacy for kidney transplantation.

Deceased Organ Donation Rates, Waiting Times, and ESKD Treatment Rates

Data on deceased organ donation rates (per million population), median waiting times of dialysis treatment before transplantation, and the rate of treated ESKD in Canadian provinces were determined using data from CORR.

Predictors of Referral for Kidney Transplantation

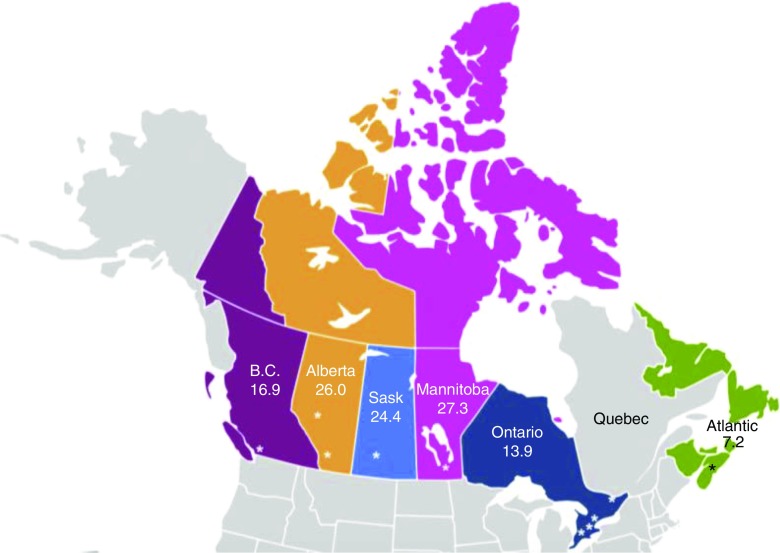

Deceased organ donor services in Canada are organized provincially and organs are routinely only distributed within provinces with the exception of the Atlantic Provinces (i.e., Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland, and Prince Edward Island), which are covered by a single regional organ donation service provider. Accordingly, our primary variable of interest was province of residence with the Atlantic provinces considered as a single group. In addition, the small number of patients with ESKD residing in Canada’s northern territories (i.e., Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut) were analyzed in the province that provides organ donation and transplant services for each territory. Figure 1 shows the seven regions defined primarily by province within which deceased donor kidneys are routinely shared.

Figure 1.

Referral for kidney transplantation in Canadian Regions. The referral rate per hundred patient-years of dialysis is shown for each region. B.C., British Columbia; Sask, Saskatchewan.

A number of patient-related factors were explored as potential predictors of transplant referral in statistical models. These factors included patient age, sex, race, cause of ESKD, body mass index, number of comorbid disease conditions (including history of type 1 or 2 diabetes, angina, myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, cerebrovascular accident, peripheral vascular disease, malignancy, and lung disease), smoking status, initial dialysis modality, duration of predialysis care by a nephrologist, serum albumin at dialysis initiation, history of prior kidney transplantation, neighborhood income quintile of the patient’s dialysis center (on the basis of national census data, in Canadian dollars), distance from the patient’s dialysis center to the nearest transplant center, and whether kidney transplantation services were offered at the center where the patient received dialysis treatment.

Statistical Analyses

Exploratory analyses were performed using descriptive statistics and graphical methods to assess the distribution and characteristics of all predictor variables. Incidence rates of referral over the study period were calculated (per 100 patient-years) by province. The time from dialysis initiation to referral for kidney transplantation was graphically examined across strata of various baseline characteristics using the Kaplan–Meier product limit method and group differences were determined by the log-rank test. Death, loss to follow-up, or end of study (May 31, 2013) before observing the outcome of interest (i.e., referral for kidney transplantation) were treated as censoring events.

A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model was used to examine the independent association of province of residence with the likelihood of referral for kidney transplantation. In this analysis, Ontario was selected as the referent group because it is the most populous Canadian province. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using log-negative-log plots of the within-group survivorship probabilities versus log-time. No significant departures from proportionality were observed.

Multiple imputation with ten simulated datasets was used to handle missing covariate data in the statistical models. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Research Ethics Board at the Toronto General Hospital, University Health Network approved the study.

Sensitivity Analyses

Because the severity of comorbid diseases may not be adequately characterized in registry data, a sensitivity analysis was performed where an assumed healthier subcohort of patients<60 years age, without documented comorbidity, and a nondiabetic cause of ESRD was used to repeat the main analysis. Because of the unique system of transplant referral in Atlantic provinces, in which patients undergo preliminary evaluation in their province of residence before being formally referred to the regional kidney transplant center in Halifax, Nova Scotia, a sensitively analysis excluding the Atlantic provinces was performed. Finally, pre-emptively referred patients were included as new referrals to assess the effect on the likelihood of transplant referral in the main model.

Results

Patient Characteristics

The characteristics of incident patients with ESKD at the time of dialysis initiation grouped by their providence of residence are shown in Table 1. Province of residence was missing for n=27 patients. The frequencies of missing data are shown in Supplemental Table 2 and averaged 3.7% with a range of 0%–11.96%.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by province of residence

| Characteristic | British Columbia | Alberta | Saskatchewan | Manitoba | Ontario | Atlantic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients in province/region | 2198 | 1270 | 496 | 751 | 7267 | 1175 |

| Population (millions) | 4.6 | 3.9 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 13.3 | 2.4 |

| Rate of ESKD per million population | 440 | 315 | 456 | 565 | 511 | 482 |

| Number of transplant centers | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Age at initial dialysis, yr | 67.4 (±14.0) | 63.3 (±15.2) | 61.6 (±15.9) | 61.8 (±15.5) | 66.0 (±14.9) | 64.3 (±14.4) |

| 18.0–40.0 | 105 (4.8%) | 116 (9.1%) | 56 (11.3%) | 74 (9.9%) | 450 (6.2%) | 91 (7.7%) |

| 40.1–50.0 | 169 (7.7%) | 132 (10.4%) | 64 (12.9%) | 90 (12.0%) | 692 (9.5%) | 106 (9.0%) |

| 50.1–60.0 | 336 (15.3%) | 234 (18.4%) | 87 (17.5%) | 159 (21.2%) | 1150 (15.8%) | 206 (17.5%) |

| 60.1–65.0 | 252 (11.5%) | 173 (13.6%) | 66 (13.3%) | 103 (13.7%) | 874 (12.0%) | 149 (12.7%) |

| 65.1–70.0 | 288 (13.1%) | 149 (11.7%) | 62 (12.5%) | 90 (12.0%) | 937 (12.9%) | 170 (14.5%) |

| 70.1–75.0 | 328 (14.9%) | 161 (12.7%) | 54 (10.9%) | 79 (10.5%) | 954 (13.1%) | 174 (14.8%) |

| >75.0 | 720 (32.8%) | 305 (24.0%) | 107 (21.6%) | 156 (20.8%) | 2210 (30.4%) | 279 (23.7%) |

| Male sex | 1394 (63.4%) | 790 (62.2%) | 309 (62.3%) | 432 (57.5%) | 4478 (61.6%) | 733 (62.4%) |

| Recipient race | ||||||

| White | 1403 (68.4%) | 827 (70.4%) | 313 (65.6%) | 348 (50.1%) | 5108 (71.6%) | 1052 (94.6%) |

| Asian | 252 (12.3%) | 84 (7.2%) | 10 (2.1%) | 37 (5.3%) | 454 (6.4%) | 4 (0.4%) |

| Black | 9 (0.4%) | 29 (2.5%) | 5 (1.1%) | 14 (2.0%) | 458 (6.4%) | 15 (1.4%) |

| Indian subcontinent | 214 (10.4%) | 55 (4.7%) | 3 (0.6%) | 3 (0.4%) | 460 (6.5%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Aboriginal | 69 (3.4%) | 121 (10.3%) | 139 (29.1%) | 256 (36.8%) | 206 (2.9%) | 31 (2.8%) |

| Other | 103 (5.0%) | 59 (5.0%) | 7 (1.5%) | 37 (5.3%) | 445 (6.2%) | 9 (0.8%) |

| Cause of ESKD | ||||||

| Diabetes | 754 (37.4%) | 550 (44.8%) | 225 (45.6%) | 383 (53.0%) | 2918 (42.9%) | 427 (37.4%) |

| Glomerular disease | 293 (14.5%) | 226 (18.4%) | 80 (16.2%) | 128 (17.7%) | 1035 (15.2%) | 204 (17.9%) |

| Hypertension | 345 (17.1%) | 93 (7.6%) | 37 (7.5%) | 53 (7.3%) | 802 (11.8%) | 79 (6.9%) |

| Polycystic | 57 (2.8%) | 47 (3.8%) | 18 (3.7%) | 19 (2.6%) | 228 (3.4%) | 55 (4.8%) |

| Urologic disease | 39 (1.9%) | 49 (4%) | 19 (3.9%) | 14 (1.9%) | 146 (2.1%) | 38 (3.3%) |

| Other | 308 (15.3%) | 143 (11.6%) | 61 (12.4%) | 105 (14.5%) | 1285 (18.9%) | 263 (23%) |

| Unknown | 220 (10.9%) | 120 (9.8%) | 53 (10.8%) | 21 (2.9%) | 393 (5.8%) | 77 (6.7%) |

| BMI at initial dialysis, kg/m2 | 28.3 (±7.5) | 28.6 (±7.4) | 28.9 (±7.9) | 28.4 (±7.2) | 28.2 (±7.2) | 29.9 (±8.1) |

| ≤18.0 | 35 (2.0%) | 33 (2.8%) | 11 (2.4%) | 14 (2.1%) | 189 (2.8%) | 17 (1.6%) |

| 18.1–25.0 | 598 (33.4%) | 382 (32.6%) | 138 (30.5%) | 224 (33.0%) | 2329 (34.2%) | 276 (25.1%) |

| 25.1–30.0 | 610 (34.1%) | 346 (29.5%) | 151 (33.3%) | 207 (30.5%) | 2084 (30.6%) | 338 (30.8%) |

| 30.1–35.0 | 277 (15.5%) | 222 (18.9%) | 80 (17.7%) | 140 (20.6%) | 1200 (17.6%) | 247 (22.5%) |

| >35.0 | 271 (15.1%) | 189 (16.1%) | 73 (16.1%) | 94 (13.8%) | 999 (14.7%) | 221 (20.1%) |

| Comorbid disease conditions | ||||||

| None | 572 (31.3%) | 334 (28.9%) | 120 (25.6%) | 268 (38.5%) | 2160 (31.2%) | 309 (27.3%) |

| 1 | 632 (34.6%) | 348 (30.1%) | 144 (30.8%) | 242 (34.8%) | 2060 (29.8%) | 339 (30.0%) |

| 2 | 354 (19.4%) | 265 (22.9%) | 110 (23.5%) | 126 (18.1%) | 1396 (20.2%) | 224 (19.8%) |

| 3 or more | 270 (14.8%) | 208 (18.0%) | 94 (20.1%) | 60 (8.6%) | 1302 (18.8%) | 260 (23.0%) |

| Serum albumin at dialysis initiation, g/La | 33.8 (±7.0) | 31.2 (±6.7) | 27.8 (±6.8) | 29.9 (±6.3) | 32.0 (±7.0) | 31.5 (±6.7) |

| ≤27.0 | 399 (19.2%) | 286 (27.6%) | 213 (45.0%) | 204 (34.1%) | 1771 (25.8%) | 282 (25.7%) |

| 27.1–32.0 | 443 (21.3%) | 288 (27.8%) | 147 (31.1%) | 169 (28.2%) | 1676 (24.4%) | 299 (27.3%) |

| 32.1–37.0 | 520 (25.1%) | 281 (27.2%) | 83 (17.6%) | 167 (27.9%) | 1852 (27.0%) | 326 (29.7%) |

| >37.0 | 714 (34.4%) | 180 (17.4%) | 30 (6.3%) | 59 (9.9%) | 1568 (22.8%) | 190 (17.3%) |

| Current smoker | 223 (12.8%) | 215 (19.9%) | 93 (22.7%) | 119 (18.3%) | 999 (15.0%) | 198 (18.8%) |

| Prior kidney transplant | 29 (1.3%) | 32 (2.5%) | 11 (2.2%) | 5 (0.7%) | 134 (1.8%) | 18 (1.5%) |

| Duration of predialysis care, mo | 14.8 (0.6, 45.5) | 18.9 (1.4, 56.9) | 18.8 (1.1, 57.9) | 16.1 (2.2, 45.3) | 23.2 (2.0, 61.2) | 27.8 (6.3, 74.0) |

| 0 | 461 (21.1%) | 105 (9.0%) | 50 (10.4%) | 65 (9.5%) | 467 (6.8%) | 34 (3.3%) |

| 0.1–6 | 375 (17.2%) | 311 (26.6%) | 128 (26.6%) | 171 (25.0%) | 1748 (25.4%) | 212 (20.8%) |

| 6.1–12.0 | 179 (8.2%) | 89 (7.6%) | 35 (7.3%) | 71 (10.4%) | 502 (7.3%) | 89 (8.7%) |

| 12.1–24.0 | 287 (13.2%) | 134 (11.5%) | 47 (9.8%) | 97 (14.2%) | 782 (11.4%) | 145 (14.2%) |

| 24.1–36.0 | 199 (9.1%) | 92 (7.9%) | 41 (8.5%) | 75 (11.0%) | 612 (8.9%) | 85 (8.3%) |

| >36.0 | 682 (31.2%) | 437 (37.4%) | 180 (37.4%) | 206 (30.1%) | 2779 (40.3%) | 455 (44.6%) |

| Initial dialysis type | ||||||

| Conventional hemodialysis | 1714 (78%) | 1110 (87.4%) | 416 (83.9%) | 627 (83.5%) | 5905 (81.3%) | 1052 (89.5%) |

| Daily hemodialysis | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 95 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Nocturnal hemodialysis | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 22 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 482 (21.9%) | 160 (12.6%) | 79 (15.9%) | 124 (16.5%) | 1245 (17.1%) | 123 (10.5%) |

| Kidney transplantation at dialysis center | 26.8% | 57.5% | 51.6% | 41.5% | 21.6% | 22.6% |

| Distance from dialysis center to transplant center, kmb | 19.3 (0, 95.8) | 0 (0, 4.5) | 0 (0, 237.0) | 3.0 (0, 6.3) | 28.8 (0, 55.6) | 208.6 (189.5, 642.9) |

| 0 | 592 (26.9%) | 732 (57.7%) | 259 (52.2%) | 323 (43.0%) | 1868 (25.8%) | 271 (24.1%) |

| 0.1–30.0 | 628 (28.6%) | 340 (26.8%) | 2 (0.4%) | 361 (48.1%) | 2268 (31.3%) | 3 (0.3%) |

| 30.1–100. 0 | 517 (23.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1451 (20.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| >100.0 | 461 (21.0%) | 196 (15.5%) | 234 (47.2%) | 67 (8.9%) | 1654 (22.8%) | 852 (75.7%) |

| Residential neighborhoodb income ($) | 63,376 (54,053, 72,769) | 74,782 (64,204, 85,896) | 53,562 (42,009, 67,638) | 53,787.5 (39,980, 65,115) | 65,998 (55,081, 80,357) | 50,934 (42,545, 59,106) |

| ≤50,900 | 386 (17.7%) | 46 (3.7%) | 171 (35.0%) | 336 (45.7%) | 1148 (15.9%) | 533 (46.8%) |

| $50,901–59,201 | 401 (18.3%) | 165 (13.2%) | 142 (29.1%) | 151 (20.5%) | 1393 (19.3%) | 334 (29.4%) |

| $59,202–67,835 | 623 (28.5%) | 239 (19.1%) | 83 (17.0%) | 109 (14.8%) | 1422 (19.7%) | 131 (11.5%) |

| $67,836–81,149 | 497 (22.7%) | 352 (28.1%) | 38 (7.8%) | 83 (11.3%) | 1539 (21.3%) | 94 (8.3%) |

| ≥$81,150 | 280 (12.8%) | 449 (35.9%) | 54 (11.1%) | 56 (7.6%) | 1712 (23.7%) | 46 (4.0%) |

Data are displayed as n (%), unless otherwise indicated. Province of residence was not recorded in 27 patients. Comorbid conditions include history of angina, myocardial infarction, pulmonary edema, type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular accident, malignancy, lung disease, and coronary artery revascularization. British Columbia includes Yukon Territories n=4. Alberta includes Northwest Territories n=11. Manitoba includes Nunavut n=2. BMI, body mass index.

Mean and SD.

Median (25th, 75th percentile).

Deceased Organ Donation Rates and Waiting Times for Transplantation

During the study period, the deceased organ donation rate per million population was highest in Ontario and the Atlantic provinces, followed by British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan (Table 2). The median duration of dialysis treatment before deceased donor transplantation was the longest in Manitoba; similar (i.e., within 1 year) in Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan; and the shortest in the Atlantic Provinces (Table 2).

Table 2.

Deceased donation rates and waiting times for deceased donor transplantation in Canadian Provinces

| Province | Deceased Donor Rate per Million Population | Median Waiting Times for Deceased Donor Transplantation (d) |

|---|---|---|

| Ontario | 16.7 | 1510 |

| Atlantic | 15.6 | 999 |

| British Columbia | 13.1 | 1642 |

| Alberta | 10.1 | 1351 |

| Manitoba | 9.7 | 1746 |

| Saskatchewan | 9.7 | 1499 |

Referrals for Transplantation by Province

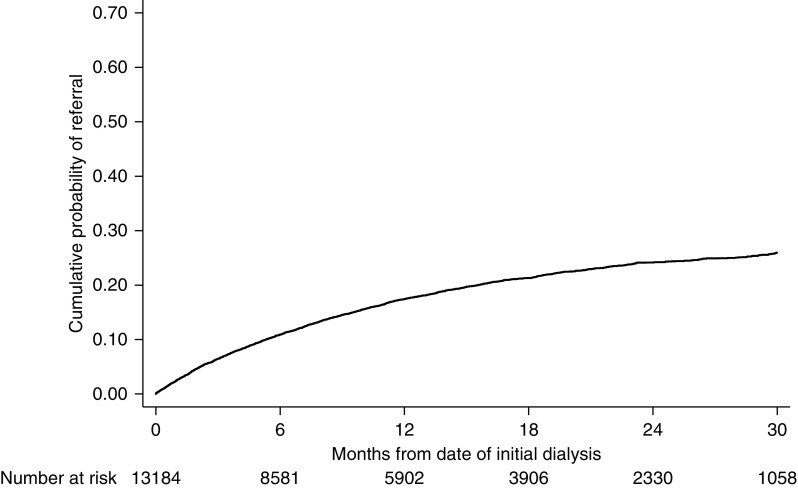

A total of 13,184 adult patients with ESKD initiated chronic dialysis from June 1, 2010 to May 31, 2013 across Canada’s provinces excluding Quebec. Among these patients, 2191 were referred for kidney transplantation over 13,898 total person-years of follow-up, with a median follow-up of 0.9 (interquartile range, 0.3–1.7) years. This represents an incidence rate of 15.8 per 100 person-years (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 15.1 to 16.4) or cumulative incidences of 17.3%, 24.0%, and 26.8% at 12, 24, and 36 months of follow-up, respectively (Figure 2). Among incident patients with ESKD <70 years of age, the incidence rate of referral was 27.5 per 100 patient-years (95% CI, 26.3 to 28.7) and the cumulative incidences of referral were 28.1% (95% CI, 27.0% to 29.3%), 38.1% (95% CI, 36.1% to 39.6%), and 41.8% (95% CI, 39.9% to 43.8%) at 12, 24, and 36 months after dialysis initiation, respectively.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of referral for kidney transplantation among incident patients on dialysis in Canada.

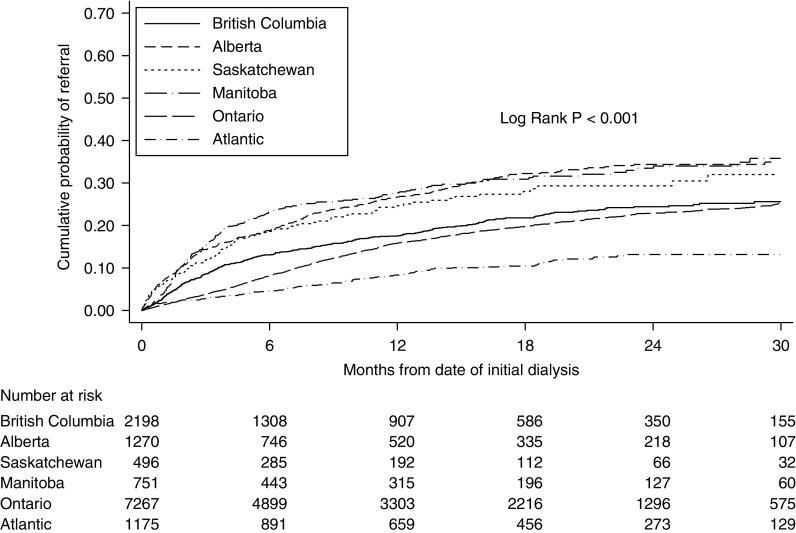

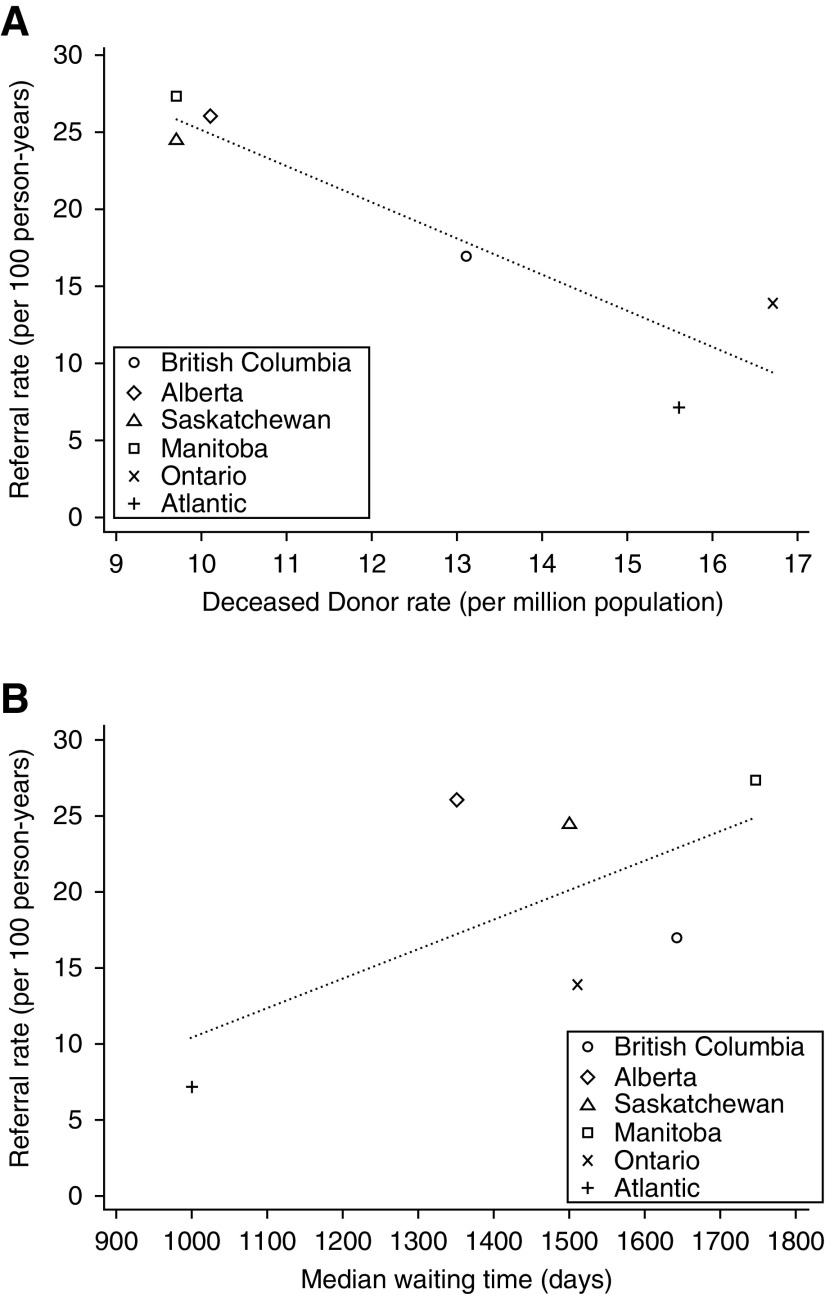

The cumulative incidence of referral for transplantation varied between provinces and was lowest in Ontario and the Atlantic provinces (Figure 3). Table 3 shows the unadjusted referral rates for transplantation per 100 patient-years by province. Ontario and Atlantic Canada had the lowest referral rates for transplantation despite having the highest deceased donor rates. Figure 4A shows the association between the provincial deceased donor rate and the referral for transplantation; contrary to the study hypothesis, provinces with lower deceased donor rates had higher rates of referral. The relationship between transplant referral and provincial median waiting times for deceased donor transplantation was also unexpected (Figure 4B); there was no statistically significant association between median waiting times for transplantation and referral.

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence of referral for kidney transplantation by province of residence.

Table 3.

Unadjusted referral rate for kidney transplantation among incident patients with ESKD treated with dialysis between June of 2010 and May of 2013

| Province | Number of Incident Patients with ESKD | Number of Referrals | Referral Rate (95% CI) per 100 Patient-Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| All provinces | 13,184 | 2191 | 15.76 (15.12 to 16.44) |

| British Columbia | 2198 | 362 | 16.96 (15.30 to 18.80) |

| Alberta | 1270 | 323 | 26.07 (23.38 to 29.07) |

| Saskatchewan | 496 | 111 | 24.44 (20.29 to 29.44) |

| Manitoba | 751 | 201 | 27.35 (23.82 to 31.40) |

| Ontario | 7267 | 1087 | 13.89 (13.08 to 14.74) |

| Atlantic provincesa | 1175 | 107 | 7.17 (5.93 to 8.67) |

Incident patients with ESKD in Yukon territory (n=4) are referred for transplantation in British Columbia and included in British Columbia statistics. Incident patients with ESKD in Northwest Territories (n=11) are included in Alberta statistics. Incident patients with ESKD in Nunavut (n=2) are included in Manitoba statistics.

Deceased organ donors are shared between Atlantic Provinces and all kidney transplants are performed in one center in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Figure 4.

Association of deceased donor rate per million (A) and median waiting time for transplantation (B) with patient referral for transplantation. Provinces with a lower deceased donor rate had a higher rate of referral (referral rate = 48.6–2.3 [deceased donor rate]; 95% CI for slope, −3.7 to −0.9; P=0.01). There was no significant association between the median waiting time in provinces and referral (referral rate = −8.9+0.02 [median waiting time]; 95% CI for slope, 0.01 to 0.05; P=0.17).

Factors Associated with Referral for Transplantation

Associations between the following patient-related factors and time to referral were identified: patient age, sex, race, cause of ESKD, body mass index, comorbid conditions, serum albumin concentration, smoking status, history of prior kidney transplantation, duration of predialysis nephrology care, dialysis type, availability of transplant services at the patient’s dialysis center, and median neighborhood income of the patient’s dialysis center (Supplemental Figures 1–14).

The results of the multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model examining factors associated with the time from dialysis initiation to referral for kidney transplantation are shown in Table 4. Compared with incident patients with ESKD in Ontario, patients in British Columbia, Alberta, and Manitoba had a 34%–74% higher likelihood of referral for transplantation, whereas patients in Atlantic provinces had a 39% lower likelihood of referral for transplantation. Various patient characteristics were associated with a lower relative hazard for kidney transplant referral, including older age, female sex, diabetes-related ESKD (compared with glomerular disease– or hypertension-related ESKD), the presence of comorbid disease conditions, predialysis nephrology care >12.0 months, and receipt of dialysis in a dialysis center >100 km from a transplant center. None of the patients belonging to nonwhite race groups (Asian, Black, Indian subcontinent, Aboriginal, other) had a lower likelihood of kidney transplant referral when compared with white patients, and there were no associations between median neighborhood income and referral.

Table 4.

Factors associated with referral for transplantation in Canadian Provinces (Cox multivariable regression model)

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Province of residence | ||

| British Columbia | 1.34 (1.18 to 1.52) | <0.001 |

| Alberta | 1.64 (1.43 to 1.89) | <0.001 |

| Saskatchewan | 1.60 (1.29 to 1.97) | <0.001 |

| Manitoba | 1.74 (1.47 to 2.07) | <0.001 |

| Ontario (reference) | 1.0 | |

| Atlantic Provinces | 0.61 (0.49 to 0.75) | <0.001 |

| Age, yr | ||

| 18.0–40.0 | 1.52 (1.33 to 1.74) | <0.001 |

| 40.1–50.0 | 1.15 (1.02 to 1.30) | 0.03 |

| 50.1–60.0 (reference) | 1.0 | |

| 60.1–65.0 | 0.81 (0.71 to 0.92) | 0.001 |

| 65.1–70.0 | 0.50 (0.43 to 0.59) | <0.001 |

| 70.1–75.0 | 0.22 (0.18 to 0.27) | <0.001 |

| >75.0 | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.04) | <0.001 |

| Female sex (reference “male”) | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.97) | 0.01 |

| Race | ||

| White (reference) | 1.0 | |

| Asian | 1.17 (0.99 to 1.38) | 0.07 |

| Black | 1.10 (0.91 to 1.33) | 0.34 |

| Indian subcontinent | 1.26 (1.06 to 1.50) | 0.01 |

| Aboriginal | 1.05 (0.89 to 1.23) | 0.56 |

| Other | 1.30 (1.10 to 1.53) | 0.002 |

| Cause of ESKD | ||

| Diabetes (reference) | 1.0 | |

| Glomerular disease | 1.30 (1.16 to 1.46) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.20 (1.02 to 1.41) | 0.03 |

| Polycystic | 1.03 (0.84 to 1.25) | 0.80 |

| Urologic disease | 0.80 (0.59 to 1.08) | 0.15 |

| Other | 0.76 (0.65 to 0.89) | 0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.03 (0.84 to 1.26) | 0.76 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||

| ≤18.0 | 0.83 (0.62 to 1.10) | 0.20 |

| 18.1–25.0 (reference) | 1.0 | |

| 25.1–30.0 | 1.20 (1.08 to 1.34) | 0.001 |

| 30.1–35.0 | 1.23 (1.08 to 1.40) | 0.002 |

| >35.0 | 0.97 (0.84 to 1.13) | 0.72 |

| Comorbid disease conditions | ||

| 0 (reference) | 1.0 | |

| 1 | 0.71 (0.64 to 0.79) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 0.72 (0.63 to 0.83) | <0.001 |

| 3 or more | 0.47 (0.39 to 0.58) | <0.001 |

| Serum albumin, g/L | ||

| ≤27.0 | 0.91 (0.80 to 1.05) | 0.19 |

| 27.1–32.0 (reference) | 1.0 | |

| 32.1–37.0 | 1.16 (1.02 to 1.33) | 0.02 |

| >37.0 | 1.14 (0.99 to 1.31) | 0.07 |

| Current smoker (reference “no”) | 0.94 (0.83 to 1.05) | 0.26 |

| Prior kidney transplant (reference “no”) | 1.01 (0.80 to 1.30) | 0.91 |

| Duration of predialysis care, yr | ||

| 0 | 0.91 (0.77 to 1.07) | 0.27 |

| 0.1–6 (reference) | 1.0 | |

| 6.1–12.0 | 0.88 (0.74 to 1.04) | 0.14 |

| 12.1–24.0 | 0.72 (0.61 to 0.84) | <0.001 |

| 24.1–36.0 | 0.74 (0.63 to 0.88) | 0.001 |

| >36.0 | 0.73 (0.65 to 0.83) | <0.001 |

| Dialysis type | ||

| Conventional hemodialysis (reference) | 1.0 | |

| Daily hemodialysis | 0.69 (0.40 to 1.20) | 0.19 |

| Nocturnal hemodialysis | 1.22 (0.63 to 2.37) | 0.56 |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 0.91 (0.82 to 1.02) | 0.12 |

| Kidney transplantation at dialysis center (reference “yes”) | 1.05 (0.80 to 1.38) | 0.73 |

| Distance from dialysis to transplant center, km | ||

| 0 (reference) | 1.0 | |

| 0.1–30.0 | 0.79 (0.60 to 1.04) | 0.10 |

| 30.1–100. 0 | 0.97 (0.73 to 1.29) | 0.86 |

| >100.0 | 0.72 (0.54 to 0.95) | 0.02 |

| Median neighborhood income (Canadian dollars) | ||

| Q1 ≤$50,900 | 0.88 (0.76 to 1.02) | 0.09 |

| Q2 $50,901–59, 01 | 0.96 (0.83 to 1.11) | 0.59 |

| Q3 $59,202–67,835 | 0.95 (0.83 to 1.09) | 0.47 |

| Q4 $67,836–81,149 | 0.98 (0.86 to 1.12) | 0.76 |

| Q5 ≥$81,150 (reference) | 1.0 |

Q, quintile.

Sensitivity Analyses

In the subcohort analysis restricted to patients aged <60 years, without comorbid conditions, and with non–diabetes-related ESKD, the differences in referrals for transplantation between provinces were attenuated and were imprecise compared with the main analysis. Female sex and distance from a transplant center >100 km were also no longer associated with a lower likelihood of transplant referral (Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors associated with referral for transplantation—sensitivity analyses

| Variable | Subcohort of Patients<60 yr, without Comorbid Conditions, and with Cause of ESKD Other than Diabetes, n=1540, Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Inclusion of n=966 Patients Referred for Transplantation before Initiation of Dialysis Treatment, n=14,150, Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Province of residence | ||

| British Columbia | 1.18 (0.92 to 1.50) | 1.49 (1.34 to 1.66) |

| Alberta | 1.09 (0.82 to 1.44) | 1.95 (1.75 to 2.17) |

| Saskatchewan | 1.52 (1.00 to 2.30) | 1.74 (1.46 to 2.08) |

| Manitoba | 1.27 (0.88 to 1.86) | 1.85 (1.61 to 2.14) |

| Ontario (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Atlantic Provinces | 0.77 (0.54 to 1.10) | 0.88 (0.75 to 1.04) |

| Age, yr | ||

| 18.0–40.0 | 1.52 (1.24 to 1.87) | 1.48 (1.32 to 1.65) |

| 40.1–50.0 | 0.98 (0.79 to 1.21) | 1.15 (1.04 to 1.27) |

| 50.1–60.0 (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 60.1–65.0 | NA | 0.79 (0.71 to 0.89) |

| 65.1–70.0 | NA | 0.48 (0.42 to 0.55) |

| 70.1–75.0 | NA | 0.23 (0.19 to 0.27) |

| >75.0 | NA | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.04) |

| Female sex (reference “male”) | 1.03 (0.87 to 1.22) | 0.88 (0.82 to 0.95) |

| Race | ||

| White (ref.) | ||

| Asian | 1.52 (1.16 to 2.00) | 0.98 (0.85 to 1.13) |

| Black | 1.17 (0.84 to 1.63) | 1.04 (0.88 to 1.22) |

| Indian subcontinent | 1.21 (0.84 to 1.72) | 1.14 (0.98 to 1.32) |

| Aboriginal | 1.25 (0.91 to 1.72) | 0.90 (0.79 to 1.04) |

| Other | 1.51 (1.14 to 2.02) | 1.12 (0.97 to 1.29) |

| Cause of ESKD | ||

| Diabetes | NA | 1.0 |

| Glomerular disease | 1.0 | 1.19 (1.08 to 1.31) |

| Hypertension | 0.84 (0.64 to 1.09) | 1.06 (0.93 to 1.22) |

| Polycystic | 0.81 (0.61 to 1.08) | 1.23 (1.06 to 1.42) |

| Urologic disease | 0.76 (0.49 to 1.17) | 0.86 (0.68 to 1.09) |

| Other | 0.73 (0.56 to 0.95) | 0.79 (0.69 to 0.91) |

| Unknown | 0.78 (0.57 to 1.08) | 0.90 (0.75 to 1.07) |

| Body mass index, kg/m | ||

| ≤18.0 | 0.96 (0.63 to 1.46) | 0.72 (0.55 to 0.94) |

| 18.1–25.0 (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 25.1–30.0 | 1.38 (1.13 to 1.68) | 1.19 (1.08 to 1.30) |

| 30.1–35.0 | 1.17 (0.91 to 1.52) | 1.16 (1.05 to 1.29) |

| >35.0 | 1.01 (0.75 to 1.37) | 0.91 (0.81 to 1.03) |

| Comorbid disease conditions | ||

| None (ref.) | ||

| 1 | NA | 0.72 (0.66 to 0.79) |

| 2 | NA | 0.65 (0.58 to 0.74) |

| 3 or more | NA | 0.42 (0.35 to 0.51) |

| Serum albumin, g/L | ||

| ≤27.0 | 1.01 (0.76 to 1.33) | 0.83 (0.75 to 0.93) |

| 27.1–32.0 (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 32.1–37.0 | 1.23 (0.96 to 1.59) | 1.15 (1.04 to 1.27) |

| >37.0 | 1.12 (0.85 to 1.47) | 1.16 (1.04 to 1.29) |

| Current smoker (reference “no”) | 1.11 (0.89 to 1.37) | 0.89 (0.80 to 0.99) |

| Prior kidney transplant (reference “no”) | 1.09 (0.76 to 1.56) | 0.90 (0.73 to 1.11) |

| Duration of predialysis care, yr | ||

| 0 | 1.15 (0.88 to 1.50) | 0.71 (0.61 to 0.83) |

| 0.1–6 (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 6.1–12.0 | 0.93 (0.63 to 1.36) | 0.95 (0.83 to 1.09) |

| 12.1–24.0 | 0.55 (0.38 to 0.79) | 0.80 (0.70 to 0.91) |

| 24.1–36.0 | 0.59 (0.40 to 0.86) | 0.80 (0.69 to 0.92) |

| >36.0 | 0.63 (0.50 to 0.80) | 0.80 (0.72 to 0.89) |

| Dialysis type | ||

| Conventional hemodialysis (ref.) | ||

| Daily hemodialysis | 0.40 (0.13 to 1.26) | 0.88 (0.56 to 1.38) |

| Nocturnal hemodialysis | 1.49 (0.65 to 3.44) | 1.37 (0.80 to 2.34) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 0.84 (0.68 to 1.04) | 1.20 (1.10 to 1.31) |

| Kidney transplantation at dialysis center (reference “yes”) | 1.31 (0.82 to 2.08) | 1.00 (0.79 to 1.25) |

| Distance from dialysis to transplant center | ||

| 0 (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 0.1–30.0 | 0.74 (0.47 to 1.18) | 0.83 (0.66 to 1.04) |

| 30.1–100.0 | 0.73 (0.45 to 1.19) | 0.90 (0.70 to 1.14) |

| >100.0 | 0.75 (0.47 to 1.20) | 0.69 (0.54 to 0.87) |

| Median neighborhood income (Canadian dollars) | ||

| Q1 ≤50,900 | 0.76 (0.57 to 1.00) | 0.89 (0.78 to 1.01) |

| Q2 50,901–59,201 | 0.88 (0.68 to 1.15) | 0.93 (0.82 to 1.05) |

| Q3 59,202–67,835 | 0.90 (0.70 to 1.16) | 0.92 (0.82 to 1.03) |

| Q4 67,836–81,149 | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.13) | 0.98 (0.88 to 1.09) |

| Q5 ≥81,150 (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

NA, not applicable; Ref., reference; Q, quintile.

There were 966 patients who were referred for transplantation before initiating chronic dialysis treatment. When these patients were included in the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model, the estimated hazards of referral in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba compared with Ontario were even stronger than in the main analysis, and the estimate of hazard for referral in Atlantic provinces was imprecise (Table 5).

Discussion

We found that only 17.3% of all incident adult patients with ESKD and 28.1% of incident patients on dialysis aged 18–69 years were referred for kidney transplantation within 1 year of starting dialysis. Referrals for transplantation varied more than three-fold between provinces, and the variation in the likelihood of referral between provinces persisted even after adjustment for differences in patient age and comorbid disease conditions. Contrary to our study hypotheses, lower rates of referral were not observed in provinces with lower rates of organ donation or longer median waiting times for deceased donor transplantation. The likelihood of referral was not lower in patients of nonwhite race or in patients from areas with lower income. Variation in referrals between provinces was attenuated in a subcohort analysis of healthier patients aged <60 years of age without comorbid conditions and with non–diabetes-related kidney disease. The findings suggest the need for strategies to minimize variation in referral of patients for transplantation and highlight the need for ongoing national data collection on referral of patients with ESKD for transplantation.

The optimal rate of referral for transplantation is undefined, but the referral rate in this study is likely inappropriately low. Not all incident patients on dialysis are medically eligible for transplantation, but the available information suggests that only 10%–15% of patients on dialysis have absolute contraindications to transplantation such as active infection, malignancy, psychiatric disease, alcohol or drug addiction, or habitual nonadherence.3,4 Some authors have suggested that dialysis survival of 5 years be used as a criterion for transplant eligibility.17 By this criterion, approximately 50% of all incident patients on dialysis would be eligible for transplantation. The referral rate for transplantation in this study is similar to that reported in the state of Georgia, which has one of the lowest rates of transplantation in the United States.10,18 The fact that the number of patients wait-listed for transplantation has remained relatively unchanged in Canada over the last decade, and that only 12% of prevalent patients on dialysis in Canada are wait-listed for transplantation compared with 17% in the United States, also suggests that referral practices for transplantation in Canada may be overly restrictive.19,20

We found significant variation in referral for transplantation between Canadian provinces. Because deceased donor kidneys are not routinely shared between provinces, and organ donation rates and waiting times for transplantation are known to differ between provinces, we hypothesized that physicians working in provinces with lower donation rates and longer waiting times would adopt more restrictive referral practices and referral rates would be lower in these provinces.14 The study findings did not support this hypothesis, indicating that other factors underlie the variation in referral between provinces. In Canada, referral for transplantation is the responsibility of the patient’s primary nephrologist. This is in contrast to the United States where dialysis facility staff may share this responsibility. In the United States access to the waiting list has been linked to the for-profit status of dialysis providers, raising the possibility that referrals for transplantation in Canada may be influenced by financial considerations of nephrologists who provide dialysis care.21

Previous work has shown that knowledge of transplantation is variable among general nephrologists and this may contribute to the observed variation in referral.13,22,23 The finding that patients who initiated dialysis in hospitals that provide transplant services did not have a higher likelihood of referral is also unexpected, because nephrologists working in transplant centers were anticipated to have a greater awareness of transplantation. This finding suggests a disconnect between transplant nephrologists and general nephrologists as transplantation becomes increasingly specialized. The provision of nephrology care before the need for RRT has also been associated with patient access to transplantation.10,24 The organization of predialysis nephrology care is variable between provinces and may be another factor contributing to the variation in referral between provinces in the study.25 Some provinces have established multidisciplinary CKD clinics and have integrated programs of early transplant education in their CKD clinical protocols, whereas in other provinces predialysis care may still be primarily provided in office-based settings. Surprisingly, we found that longer durations of predialysis nephrology care >12 months were associated with lower referral for transplantation, suggesting that transplantation may be underemphasized by Canadian nephrologists providing predialysis care. The fact that waiting time for deceased donor transplantation is determined from the date of first dialysis treatment rather than the date of wait-listing in Canada may remove the impetus for early referral of patients for transplantation. However, most of the referrals occurred early after initiation of maintenance dialysis treatment and we found no evidence of a delayed increase in referrals.

The variation in referral between provinces was attenuated in a subcohort analysis of younger patients, without comorbid conditions or diabetes-related ESKD. This finding again suggests the need to improve physician understanding about the medical criteria for transplantation. Forthcoming guidelines by the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes group should help to improve physician knowledge.26 However, it should be recognized that local transplant center wait-listing practices may be unclear to referring physicians. Local considerations that may influence a transplant center’s acceptance of individual patients include physician experience, fluctuations in organ donation rates, and the patient’s age and comorbid disease burden relative to their anticipated waiting time. An additional issue that affects transplant center wait-list practice in the United States is fear of violating regulatory authority thresholds for expected transplant outcomes.27 Finally, the sense of conflict that transplant physicians may experience between their responsibility to individual patients and their societal responsibility to ensure optimal use of scarcely available deceased donor kidneys may contribute to variation in wait-list practices, particularly among older patients and patients with a high comorbid disease burden.28 Transplant centers should endeavor to establish transparent and consistent wait-list acceptance practices and to communicate changes in practice as well as individual patient decisions to referring nephrologists to improve understanding of local considerations that affect their practice.

Consistent with previous findings in the state of Georgia, we found a lower likelihood of transplant referral among female patients.10 Notably, transplant referrals are required for patients to access living donor transplantation which is more common in men.29–31 Therefore, some of the variation in referral among women may be explained by differences in the use of living donor transplantation in women.31 In contrast to studies in the United States, income was not associated with referral.10 The provision of free health care, including lifelong coverage of immunosuppressant drugs after kidney transplantation, in Canada likely contributes to this difference between Canada and the United States. The higher rate of referral among nonwhite groups is reassuring. Previous Canadian studies have shown that nonwhites have lower rates of transplantation than white patients.32–34 Our findings suggest that these differences in transplantation may not be due to differences in referral but may be due to challenges with completing the transplant evaluation or differences in wait-list acceptance of nonwhite patients.35 Of note, previous work has shown that the factors that affect referral may differ from those that affect completion of the other steps required to gain access to transplantation (i.e., completion of the transplant evaluation or acceptance onto the transplant waiting list).10 The likelihood of referral was lower among patients treated in a dialysis facility >100 km from a transplant center. A previous study on the basis of a random sample of 7000 incident patients on dialysis in Canada between 1996 and 2000 found that the likelihood of deceased donor transplantation within provinces was not affected by distance from the closest transplant center.36 The study findings indicate a need to re-evaluate the potential effect of geographic barriers to transplantation in Canada in the current era. Of note, there are several urban centers without transplant services in Canada; therefore, distance to a transplant center was used as the primary indicator of a potential geographic barrier to transplantation rather than alternative metrics such as the Rural Urban Commuting Area.

Existing information about transplant referral is on the basis of single center or regional studies because national registries do not capture information on patient referral for transplantation. At present there is concern in the United States that reorganization of dialysis care may compromise patient access to transplantation.37 Given the effect of transplantation on the survival of patients with ESKD, transparent reporting of the determinants of access to transplantation including patient referral for transplantation, and transplant center acceptance practices, are needed to ensure system fairness. It is notable that a recommendation for the national collection of referral data was first made nearly 15 years ago.38

There are several strengths to our study, including collaboration between Canadian transplant centers to prospectively collect information on referrals and linkage to a national registry of incident patients treated with dialysis to generate the first national analysis of transplant referral to our knowledge. It is regrettable that we were unable to include assembled data from the province of Quebec in this analysis due to privacy restrictions. Completion of this study was significantly delayed because we endeavored to resolve this issue with data from Quebec before we finally decided to proceed with reporting. We believe the results remain relevant today because the proportion of patients on dialysis who gain access to the waiting list in Canadian provinces has remained unchanged over the last decade.20 Our analysis did not include information on wait-list activations as these data are being reconciled for accuracy. Additional factors not captured in our analysis such as patient preferences for transplantation may influence referral for transplantation.9,39 In addition, differences in transplant resources including transplant center staff could theoretically influence referral for transplantation and should be further evaluated.

In conclusion, referral for transplantation is variable among Canadian provinces. The observed variation is unrelated to differences in deceased organ donation or transplant waiting times and attenuated in younger, healthier patients. Efforts to standardize referral practices, including inclusion of information about referral in national dialysis and transplant registries, should be considered to reduce disparities in kidney transplant referral practices.

Disclosures

Dr. Gill reports grants from Astellas, personal fees from Astellas, and personal fees from Sanofi, outside the submitted work. Dr. Kim reports grants from Astellas Pharma Canada, and grants from Pfizer Canada, outside the submitted work. Dr. Knoll reports grants from Astellas Canada, outside the submitted work. All of the remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Gill and Dr. Knoll are funded by Foundation Awards from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Data collection at the transplant centers was supported by an unrestricted grant from Roche Canada.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of the late Peter Hoult, a kidney transplant recipient who served as volunteer treasurer for the Canadian Organ Replacement Register Board of Directors for over a decade.

The authors wish to acknowledge the efforts of adult kidney transplant centers for collecting the referral data and the members of the Canadian Society of Transplantation Kidney Work Group.

The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from Roche Canada.

Dr. Gill designed the study. All authors were members of the study steering committee and oversaw the data collection. Dr. Kim oversaw the data analysis. Dr. Gill and Dr. Kim drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Variation in Kidney Transplant Referral: How Much More Evidence Do We Need To Justify Data Collection on Early Transplant Steps?” on pages 1554–1556.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2019020127/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Participating transplant centers.

Supplemental Table 2. Missing data.

Supplemental Figures 1–14. Univariate associations with referral.

References

- 1.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G, Bello A, Browne S, Jadhav D, et al.: Systematic review: Kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transplant 11: 2093–2109, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, et al.: Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med 341: 1725–1730, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kianda MN, Wissing KM, Broeders NE, Lemy A, Ghisdal L, Hoang AD, et al.: Ineligibility for renal transplantation: Prevalence, causes and survival in a consecutive cohort of 445 patients. Clin Transplant 25: 576–583, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weng FL, Joffe MM, Feldman HI, Mange KC: Rates of completion of the medical evaluation for renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 734–745, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Gustafson SK, Wilk AR, Robinson A, et al.: OPTN/SRTR 2016 Annual Data Report: Kidney. Am J Transplant 18[Suppl 1]: 18–113, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization : WHO guiding principles on human cell, tissue and organ transplantation. Transplantation 90: 229–233, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart DE, Wilk AR, Toll AE, Harper AM, Lehman RR, Robinson AM, et al.: Measuring and monitoring equity in access to deceased donor kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant 18: 1924–1935, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashby VB, Kalbfleisch JD, Wolfe RA, Lin MJ, Port FK, Leichtman AB: Geographic variability in access to primary kidney transplantation in the United States, 1996-2005. Am J Transplant 7: 1412–1423, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patzer RE, Perryman JP, Schrager JD, Pastan S, Amaral S, Gazmararian JA, et al.: The role of race and poverty on steps to kidney transplantation in the Southeastern United States. Am J Transplant 12: 358–368, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patzer RE, Plantinga LC, Paul S, Gander J, Krisher J, Sauls L, et al.: Variation in dialysis facility referral for kidney transplantation among patients with end-stage renal disease in Georgia. JAMA 314: 582–594, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander GC, Sehgal AR: Barriers to cadaveric renal transplantation among blacks, women, and the poor. JAMA 280: 1148–1152, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Keogh JH, Noonan SJ, David-Kasdan JA, Epstein AM: Physicians’ beliefs about racial differences in referral for renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis 43: 350–357, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ, Keogh JH, Noonan SJ, Armistead N, Cleary PD, et al. : Racial disparities in access to renal transplantation—clinically appropriate or due to underuse or overuse? N Engl J Med 343: 1537–1544, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gill JS, Klarenbach S, Cole E, Shemie SD: Deceased organ donation in Canada: An opportunity to heal a fractured system. Am J Transplant 8: 1580–1587, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SJ, Fenton SS, Kappel J, Moist LM, Klarenbach SW, Samuel SM, et al.: Organ donation and transplantation in Canada: Insights from the Canadian Organ Replacement Register. Can J Kidney Health Dis 1: 31, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moist LM, Fenton S, Kim JS, Gill JS, Ivis F, de Sa E, et al.: Canadian Organ Replacement Register (CORR): Reflecting the past and embracing the future. Can J Kidney Health Dis 1: 26, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schold JD, Srinivas TR, Kayler LK, Meier-Kriesche HU: The overlapping risk profile between dialysis patients listed and not listed for renal transplantation. Am J Transplant 8: 58–68, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patzer RE, Pastan SO: Kidney transplant access in the Southeast: View from the bottom. Am J Transplant 14: 1499–1505, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.USRDS : Annual Data Report: End Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institute of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canadian Institute for Health Information : Organ replacement in Canada: CORR annual statistics, 2018. Available at: https://www.cihi.ca/en/organ-replacement-in-canada-corr-annual-statistics-2018. Accessed January 25, 2019

- 21.Garg PP, Frick KD, Diener-West M, Powe NR: Effect of the ownership of dialysis facilities on patients’ survival and referral for transplantation. N Engl J Med 341: 1653–1660, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghahramani N, Sanati-Mehrizy A, Wang C: Perceptions of patient candidacy for kidney transplant in the United States: A qualitative study comparing rural and urban nephrologists. Exp Clin Transplant 12: 9–14, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghahramani N, Karparvar ZY, Ghahramani M, Shrivastava P: Nephrologists' perceptions of renal transplant as treatment of choice for end-stage renal disease, preemptive transplant, and transplanting older patients: An international survey. Exp Clin Transplant 9: 223–229, 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winkelmayer WC, Mehta J, Chandraker A, Owen WF Jr, Avorn J: Predialysis nephrologist care and access to kidney transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant 7: 872–879, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levin A, Steven S, Selina A, Flora A, Sarah G, Braden M: Canadian chronic kidney disease clinics: A national survey of structure, function and models of care. Can J Kidney Health Dis 1: 29, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) : KDIGO clinical practice guideline on the evaluation and management of candidates for kidney transplantation. 2018. Available at: https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/KDIGO-Txp-Candidate-GL-Public-Review-Draft-Oct-22.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2019

- 27.Schold JD, Buccini LD, Poggio ED, Flechner SM, Goldfarb DA: Association of candidate removals from the kidney transplant waiting list and center performance oversight. Am J Transplant 16: 1276–1284, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong A, Howard K, Wong G, Cass A, Jan S, Irving M, et al.: Nephrologists’ perspectives on waitlisting and allocation of deceased donor kidneys for transplant. Am J Kidney Dis 58: 704–716, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gill J, Dong J, Gill J: Population income and longitudinal trends in living kidney donation in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 201–207, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gore JL, Danovitch GM, Litwin MS, Pham PT, Singer JS: Disparities in the utilization of live donor renal transplantation. Am J Transplant 9: 1124–1133, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bloembergen WE, Port FK, Mauger EA, Briggs JP, Leichtman AB: Gender discrepancies in living related renal transplant donors and recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1139–1144, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeates KE, Schaubel DE, Cass A, Sequist TD, Ayanian JZ: Access to renal transplantation for minority patients with ESRD in Canada. Am J Kidney Dis 44: 1083–1089, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeates K, Wiebe N, Gill J, Sima C, Schaubel D, Holland D, et al.: Similar outcomes among black and white renal allograft recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 172–179, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Promislow S, Hemmelgarn B, Rigatto C, Tangri N, Komenda P, Storsley L, et al.: Young aboriginals are less likely to receive a renal transplant: A Canadian national study. BMC Nephrol 14: 11, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tonelli M, Chou S, Gourishankar S, Jhangri GS, Bradley J, Hemmelgarn B; Alberta Kidney Disease Network : Wait-listing for kidney transplantation among Aboriginal hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 1117–1123, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tonelli M, Klarenbach S, Manns B, Culleton B, Hemmelgarn B, Bertazzon S, et al.: Alberta Kidney Disease Network : Residence location and likelihood of kidney transplantation. CMAJ 175: 478–482, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gill JS, Wiseman A: Bandages will not fix a fractured system of chronic kidney disease care: Why the Dialysis PATIENTS Demonstration Act cannot be supported by the transplant community. Am J Transplant 19: 973–974, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sehgal AR, Leon J, Stark S: Renal network special study: Developing dialysis facility-specific kidney transplant referral clinical performance measures. 2005. Available at: http://www.therenalnetwork.org/qi/resources/TransTEPfinalrpt805.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2019

- 39.Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Weissman JS, Epstein AM: The effect of patients’ preferences on racial differences in access to renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 341: 1661–1669, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.