Significance Statement

Studies have shown significant racial and ethnic disparities in the end-of-life care received by dialysis patients with ESKD in the United States, but little is known about disparity in the palliative care services received by such patients in the inpatient setting. This retrospective cohort study of 5,230,865 hospitalizations of patients on dialysis found that, despite a significant increase in use of palliative care services from 2006 through 2014, such services remained underused. Black and Hispanic patients were less likely than white patients to receive palliative care services in the hospital, disparities that persisted in all hospital subtypes, including hospitals with a high proportion of minority patients. These results complement previous findings and highlight the importance of further investigation of systemic issues contributing to barriers and racial disparities in palliative care use.

Keywords: ESKD, ethnic minority, disparity, race, palliative care, dialysis

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Study findings show that although palliative care decreases symptom burden, it is still underused in patients with ESKD. Little is known about disparity in use of palliative care services in such patients in the inpatient setting.

Methods

To investigate the use of palliative care consultation in patients with ESKD in the inpatient setting, we conducted a retrospective cohort study using the National Inpatient Sample from 2006 to 2014 to identify admitted patients with ESKD requiring maintenance dialysis. We compared palliative care use among minority groups (black, Hispanic, and Asian) and white patients, adjusting for patient and hospital variables.

Results

We identified 5,230,865 hospitalizations of such patients from 2006 through 2014, of which 76,659 (1.5%) involved palliative care. The palliative care referral rate increased significantly, from 0.24% in 2006 to 2.70% in 2014 (P<0.01). Black and Hispanic patients were significantly less likely than white patients to receive palliative care services (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.72; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.61 to 0.84, P<0.01 for blacks and aOR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.30 to 0.68, P<0.01 for Hispanics). These disparities spanned across all hospital subtypes, including those with higher proportions of minorities. Minority patients with lower socioeconomic status (lower level of income and nonprivate health insurance) were also less likely to receive palliative care.

Conclusions

Despite a clear increase during the study period in provision of palliative care for inpatients with ESKD, significant racial disparities occurred and persisted across all hospital subtypes. Further investigation into causes of racial and ethnic disparities is necessary to improve access to palliative care services for the vulnerable ESKD population.

ESKD is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, with more than 700,000 patients in the United States requiring RRT.1 The mortality rate of patients on dialysis ranges between 20% and 25%, with a 5-year survival rate between 30% and 36%.1 Patients with ESKD on dialysis have poor life expectancy compared with the general population.2 Additionally, people with ESKD may benefit from symptom-focused palliative care services due to the high burden of severe symptoms including anorexia, pruritus, dyspnea, and depression.3–5

There is an increasing interest in palliative care and end-of-life care among different patient populations to address symptom burden as diseases progress. Palliative care has been shown to decrease the burden of debilitating symptoms, facilitate advanced care planning, prevent readmissions, avoid in-hospital death, and decrease healthcare utilization.6–11 However, palliative care remains underused in patients with ESKD compared with other chronic diseases.12

Poor knowledge of palliative care options has been reported by a majority of patients on dialysis and patients often continue dialysis until acute medical complications occur.13,14 Nearly 50% of patients with ESKD receive intensive care treatment within the last month of their lives, and this use of intensive measures has increased over the past decade.15,16 Lastly, despite the high morbidity and mortality of patients with ESKD, advance directives are only addressed in 50% of those with ESKD, with only 10% of them including decisions on dialysis at the end-of-life stage.17 Although lack of training in end-of-life conversations at the provider level likely contributes to the low rates, the lack of specific prompts regarding patient’s preferences regarding RRT in standardized advance directive forms further hampers these efforts.18,19

In addition to the above systemic barriers in the end-of-life care of all patients with ESKD, minority patients in particular are less likely to discontinue dialysis or pursue hospice care.20–22 Additionally, palliative care referral in other terminal diseases has been shown to differ among racial/ethnic groups and at the hospital level.23,24 However, there is limited data on trends and racial disparities of palliative care utilization among patients on dialysis who are admitted to the hospital. Using a large, nationally representative database, we sought to determine the trends and racial disparities in palliative care usage in patients with ESKD in the inpatient setting.

Methods

Data Sources

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) is part of a family of databases and software developed for the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.25 It is the largest, publicly available, all-payer inpatient database in the United States and is composed of discharge-level data from approximately 8-million hospitalizations annually. Since 2012, NIS data represents a stratified sampling equivalent to a 20% approximation of hospitalizations in the United States and contains clinical, demographic, and insurance information on patients gathered from hospital coding. These clinical data are documented using the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and clinically meaningful clusters of ICD-9-CMs termed Clinical Classification Software codes. We selected the time period from 2006 through 2014 to determine trends and provide for an adequate sample size.

Hospital information was obtained from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey of Hospitals. Hospital size categories are based on the number of short-term acute beds in a hospital. The teaching status and location of hospitals are categorized into urban teaching, urban nonteaching, and rural nonteaching groups. The location of hospitals is categorized into Northeast, Midwest, West, and South.25 Race and ethnicity were categorized into four groups: white, black, Hispanic, and Asian. Minority patients were defined as any race or ethnicity other than white. Patient’s median income represented a quartile classification of the estimated median household income in the patient’s zip code, derived from zip code–demographic data from Claritas. Hospitals were grouped by the proportion of minority patients admitted during the study time period: high-minority hospitals (>50%), medium-minority hospitals (25%–49%), and low-minority hospitals (<25%).26

Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study of adult patients with ESKD on dialysis hospitalized from 2006 through 2014 across the United States. We identified the patient population using ICD-9-CM codes of 585.6 (CKD5 requiring chronic dialysis) and diagnostic or procedure codes related to dialysis (listed in Supplemental Table 1).27 The exclusion criteria included elective admission, missing data on race/ethnicity (approximately 6% of all hospitalizations in NIS), and diagnosis of AKI on admission or status post–kidney transplant (diagnoses codes are listed in Supplemental Table 1).25

The primary outcome was the temporal trend of palliative care referral overall and by race/ethnicity. Palliative care referral is identified using ICD-9-CM code V66.7 (encounter for palliative care). This has been used in other studies and has been shown to have high validity in an analysis of veteran’s administrative data with 84% sensitivity and 98% specificity.23,24,28 In the secondary analysis, we conducted subgroup analyses to determine the racial disparities of palliative care utilization in hospitals based on different hospital types and patient-level factors. We also examined the association between the above patient-/hospital-level factors and different rates of palliative care referral.

Statistical Analyses

We compared the baseline characteristics of hospitalized patients with ESKD by those with and without palliative care referral. We used the chi-squared test for categorical variables, the t test for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normally distributed continuous variables. In the primary analysis, we performed Joinpoint regression analysis to determine the temporal trend of palliative care referral in the study population and each race/ethnic group. In our secondary analysis, we used survey logistic regression analysis to conduct subgroup analysis to compare the difference of palliative care utilization between each minority race/ethnicity and white race based on hospital characteristics (proportion of minority patients, size, region, location, and teaching status) and patient-level factors (Charlson comorbidity index category, insurance, and median income by zip code). We adjusted for patient-level factors (age, gender, race/ethnicity, comorbidities using Charlson comorbidity index, do-not-resuscitate status, primary insurance, and median income by zip code) and the above hospital-level factors. Unfortunately, we could not account for the availability of palliative care services in individual hospitals. Therefore, we adjusted for hospital-level factors including hospital size/teaching status as proxies because these two factors have been demonstrated to be highly correlated with the availability of palliative care services.24,29 We used an additive interaction term to determine the interaction between individual race/ethnicity and hospital minority status (proportion of patients that were minorities). We also used this survey logistic regression model to determine the association between patient and hospital-level factors and different rates of palliative care utilization. We performed Joinpoint regression analysis using Joinpoint Regression Program 4.7.0.0. We performed all other analysis using STATA version 14.2 (College Station, TX). We considered a two-tailed P value of <0.05 as statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

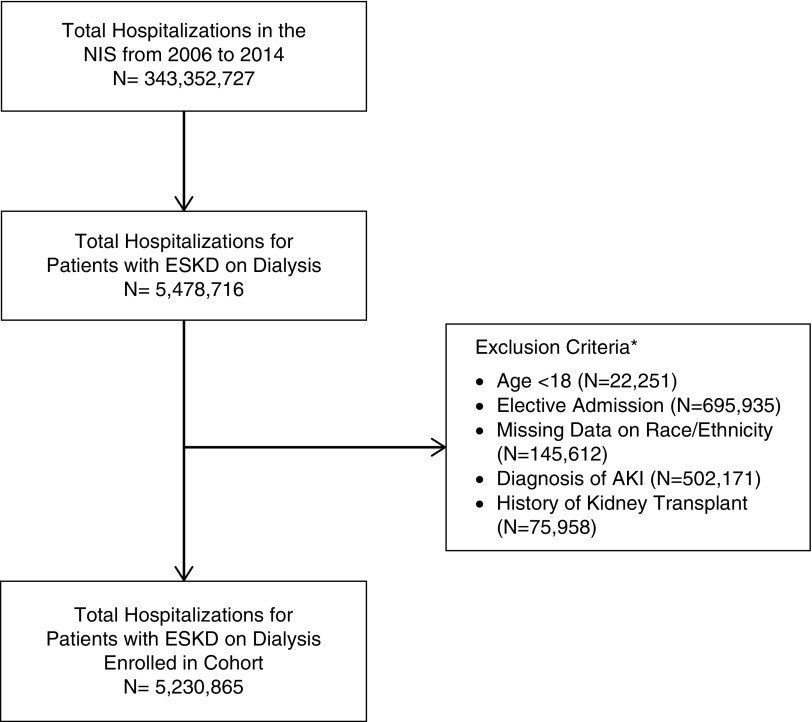

We identified 5,230,865 hospitalizations in patients with ESKD on dialysis and only 1.5% of these hospitalizations had a code for palliative care services. A study flow chart is presented in Figure 1. Patients receiving palliative care services, compared with those without, were older (70.0±0.2 versus 61.3±0.1 years old, P<0.01), male (50.3% versus 48.2%, P<0.01), white (56.5% versus 40.7%, P<0.01), had a do-not-resuscitate status (35.3% versus 1.8%, P<0.01), and had more comorbidities (proportion with Charlson comorbidity index ≥8, 11.7% versus 3.6%; P<0.01) (Table 1). Patients who received palliative care services were more likely to be of higher income (21.3% versus 15.5% with zip code median income of $63,000 or more), have Medicare (84.1% versus 77.7%, P<0.01), and less likely to have Medicaid (6.2% versus 11.1%, P<0.01). They were less likely to be from high-minority hospitals (44.9% versus 50.1%, P<0.01), more likely from urban teaching hospitals (61.5% versus 54.2%, P<0.01), and more likely from hospitals in the West (24.8% versus 19.4%, P<0.01). They were also more likely to die in the hospital (46.6% versus 3.4%, P<0.01) and had longer stays in the hospital (9.4±0.1 versus 6.3±0 days, P<0.01).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart of enrolled 5,230,865 hospitalizations of patients with ESKD on dialysis. *Numbers are not cumulative as hospitalizations may meet more than one exclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of hospitalizations of patients with ESKD with and without palliative care utilization

| Characteristics | No Palliative Care (n=5,154,206) | Palliative Care (n=76,659) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean±SD | 61.3±0.1 | 70.0±0.2 | <0.01 |

| Female, % (N) | 48.9 (2,522,613) | 47.7 (36,559) | 0.02 |

| Race/ethnicity, % (N) | <0.01 | ||

| White | 40.7 (1,859,900) | 56.5 (40,461) | |

| Black | 38.1 (1,739,369) | 26.9 (19,253) | |

| Hispanic | 16.5 (754,427) | 11.5 (8253) | |

| Asian | 3.6 (166,298) | 4.3 (3074) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index, % (N) | <0.01 | ||

| 0–4 | 67.6 (3,483,313) | 51.2 (39,284) | |

| 5–7 | 28.8 (1,483,681) | 37.0 (28,375) | |

| ≥8 | 3.6 (187,211) | 11.7 (8998) | |

| DNR status, % (N) | 1.8 (91,536) | 35.3 (27,049) | <0.01 |

| Median income per zip code, % (N)a | <0.01 | ||

| <$38,999 | 38.6 (1,939,946) | 29.8 (22,417) | |

| $39,000–$47,999 | 25.0 (1,259,430) | 25.1 (18,832) | |

| $48,000–$62,999 | 20.9 (1,050,238) | 23.8 (17,856) | |

| $63,000 or more | 15.5 (782,486) | 21.3 (16,006) | |

| Primary insurance, % (N) | <0.01 | ||

| Medicare | 77.7 (3,991,921) | 84.1 (64,108) | |

| Medicaid | 11.1 (568,204) | 6.2 (4692) | |

| Private insurance | 9.7 (497,610) | 9.0 (6845) | |

| Self-pay | 1.3 (67,941) | 0.7 (553) | |

| Hospital percentage of ethnic minority patients, % (N) | <0.01 | ||

| Low minority (<25%) | 25.0 (1,289,303) | 24.7 (18,931) | |

| Medium minority (25%–50%) | 24.9 (1,281,677) | 30.4 (23,299) | |

| High minority (>50%) | 50.1 (2,583,226) | 44.9 (34,430) | |

| Hospital location/teaching status, % (N)b | <0.01 | ||

| Rural nonteaching | 6.0 (306,940) | 4.9 (3720) | |

| Urban nonteaching | 39.8 (2,042,417) | 33.6 (25,651) | |

| Urban teaching | 54.2 (2,778,375) | 61.5 (46,862) | |

| Hospital bed size, % (N)c | <0.01 | ||

| Small | 8.9 (454,600) | 8.5 (6481) | |

| Medium | 23.8 (1,218,480) | 23.9 (18,203) | |

| Large | 67.4 (3,454,652) | 67.6 (51,550) | |

| Hospital region, % (N) | <0.01 | ||

| Northeast | 18.8 (967,860) | 17.1(13,130) | |

| Midwest | 21.0 (1,080,748) | 22.7 (17,440) | |

| South | 40.8 (2,103,233) | 35.3 (27,083) | |

| West | 19.4 (1,002,364) | 24.8 (19,006) | |

| In-hospital mortality, % (N) | 3.4 (174,186) | 46.6 (35,773) | <0.01 |

| Length of stay, mean±SD | 6.3±0 | 9.4±0.1 | <0.01 |

Frequencies (%) in the columns may not sum to 100% because there might be missing data. Data presented as percept (n) except where indicated. DNR, do not resuscitate.

This represents a quartile classification of the estimated median household income of residents in the patient’s zip code. These values are derived from zip code demographic data obtained from Claritas. The quartiles are identified by values of 1–4, indicating the poorest to wealthiest populations.27

The hospital’s teaching status was obtained from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey of Hospitals. A hospital is considered to be a teaching hospital if it has an American Medical Association–approved residency program, is a member of the Council of Teaching Hospitals, or has a ratio of full-time equivalent interns and residents to beds of 0.25 or higher. Nonmetropolitan hospitals were not split according to teaching status because rural teaching hospitals were rare. The metropolitan categorization is a simplified adaptation of the 2003 version of the Urban Influence Codes and includes both large and small metropolitan areas.27

Bed size categories are based on hospital beds, and are specific to the hospital’s location and teaching status. Bed size assesses the number of short-term acute beds in a hospital. Hospital information was obtained from the AHA Annual Survey of Hospitals.27

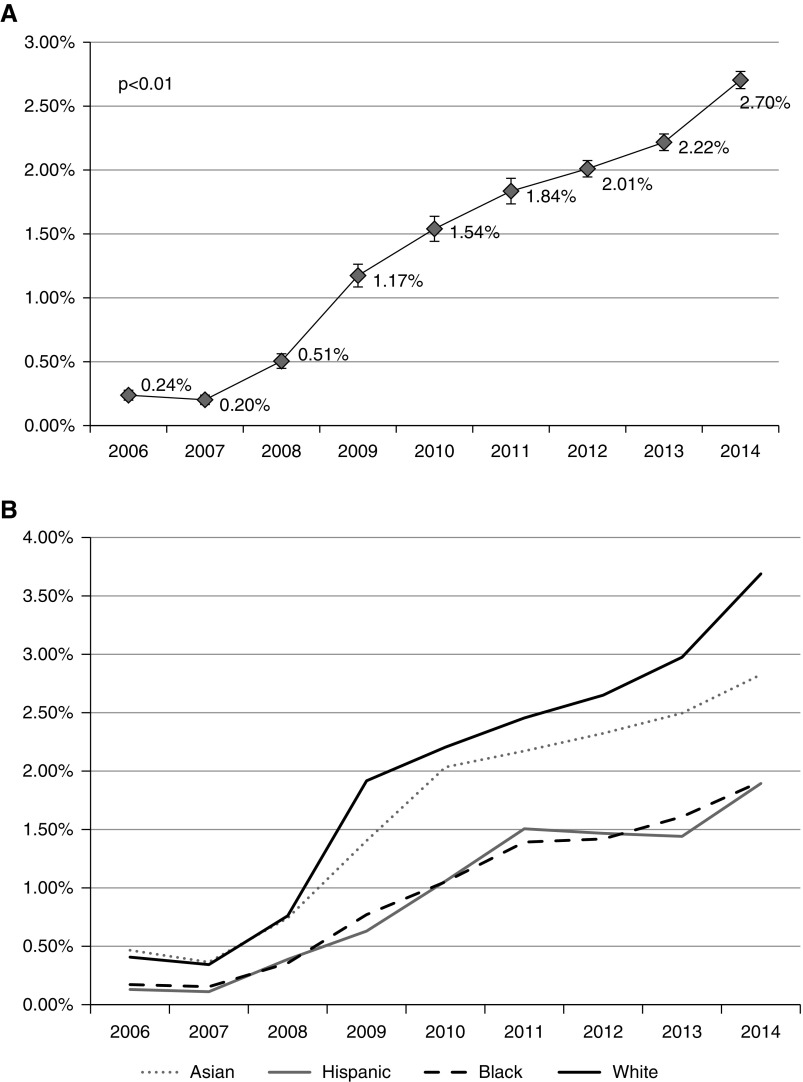

Temporal Trends of Palliative Care Referral

The incidence of palliative care utilization increased significantly from 0.24% in 2006 to 2.70% in 2014 among hospitalizations of patients with ESKD on dialysis (P<0.01) (Figure 2A). This increasing trend in palliative care utilization was observed in all racial/ethnic groups, including white (0.41% in 2006 to 3.69% in 2014, P<0.01), black (0.17% in 2006 to 1.91% in 2014, P<0.01), Hispanic (0.13% in 2006 to 1.89% in 2014, P<0.01), and Asian (0.47% in 2006 to 2.83% in 2014, P<0.01) patients. Out of all racial/ethnic groups, white patients had the fastest increase in palliative care utilization (0.41%/yr versus 0.21%/yr in black patients versus 0.22%/yr in Hispanic patients versus 0.26%/yr in Asian patients) (Figure 2B). The disproportionate increases in rates have led to a widening in the difference of palliative care utilization between white and black patients (difference of 0.24% in 2006 to 1.78% in 2014), white and Hispanic patients (difference of 0.28% in 2006 to 1.80% in 2014), and white and Asian patients (difference of 0.06% in 2006 to 0.86% in 2014).

Figure 2.

Increasing trend of palliative care referral among hospitalized ESKD patients on dialysis. (A) Increasing trend of palliative care referrals among all hospitalizations in patients with ESKD on dialysis. Brackets around points are 95% confidence intervals. (B) Increasing trend of palliative care referrals among all hospitalizations in patients with ESKD on dialysis stratified by race/ethnicity.

Factors Associated with Palliative Care Referral

Patient-level and hospital-level factors associated with palliative care utilization are shown in Table 2. There was a clear increase in odds of palliative care utilization in patients with increasing levels of comorbidities and income. Compared with those with Medicare, patients with private insurance were significantly more likely to receive palliative care services (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.18, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.09 to 1.27, P<0.01).

Table 2.

Patient- and hospital-level factors associated with palliative care use in hospitalizations for ESKD in multivariate logistic regression model

| Factors | aOR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.03 (1.02–1.03) | <0.01 |

| Female | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) | 0.18 |

| Race | ||

| White | Reference | N/A |

| Black | 0.72 (0.61–0.84) | <0.01 |

| Hispanic | 0.46 (0.30–0.68) | <0.01 |

| Asian | 1.02 (0.68–1.52) | 0.93 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||

| 0–4 | Reference | N/A |

| 5–7 | 1.40 (1.34–1.46) | <0.01 |

| ≥8 | 3.82 (3.56–4.10) | <0.01 |

| DNR status | 19.91 (18.57–21.35) | <0.01 |

| Median income per zip code | ||

| $1–$38,999 | Reference | N/A |

| $39,000–$47,999 | 1.11 (1.04–1.18) | <0.01 |

| $48,000–$62,999 | 1.16 (1.08–1.25) | <0.01 |

| $63,000 or more | 1.24 (1.14–1.35) | <0.01 |

| Primary insurance | ||

| Medicare | Reference | N/A |

| Medicaid | 0.99 (0.90–1.09) | 0.88 |

| Private insurance | 1.18 (1.09–1.27) | <0.01 |

| Self-pay | 0.98 (0.75–1.29) | 0.89 |

| Hospital percentage of ethnic minority patients | ||

| Low-minority hospital | Reference | N/A |

| Medium-minority hospital | 0.91 (0.80–1.02) | 0.10 |

| High-minority hospital | 0.79 (0.70–0.90) | <0.01 |

| Hospital teaching status/location | ||

| Rural nonteaching | Reference | N/A |

| Urban nonteaching | 1.03 (0.84–1.26) | 0.78 |

| Urban teaching | 1.60 (1.30–1.96) | <0.01 |

| Hospital size | ||

| Small | Reference | N/A |

| Medium | 1.23 (1.08–1.39) | <0.01 |

| Large | 1.45 (1.29–1.64) | <0.01 |

| Hospital region | ||

| Northeast | Reference | N/A |

| Midwest | 1.28 (1.12–1.47) | <0.01 |

| South | 1.30 (1.15–1.47) | <0.01 |

| West | 1.59 (1.38–1.82) | <0.01 |

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; N/A, not applicable; DNR, do not resuscitate.

In terms of hospital-level factors, hospitals with more minorities were less likely to provide palliative care compared with those with fewer minorities in the study population (high- versus low-minority hospitals, aOR 0.79, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.90, P<0.01). Larger hospitals compared with smaller hospitals (aOR 1.45, 95% CI 1.29 to 1.64, P<0.01) and urban teaching hospitals compared with rural nonteaching hospitals (aOR 1.60, 95% CI 1.30 to 1.96, P<0.01) had higher odds of palliative care utilization. There was also a significant difference in palliative care utilization among different geographic regions. In the multivariate logistic model, after controlling for other patient- and hospital-level factors, patients admitted to hospitals in the Midwest, South, and West were more likely to receive palliative care compared with those admitted to hospitals in the Northeast (Midwest, aOR 1.28, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.47, P<0.01; South, aOR 1.30, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.47, P<0.01; West, aOR 1.59, 95% CI 1.38 to 1.82, P<0.01).

Racial Disparities in the Provision of Palliative Care

Compared with white patients, significantly lower rates of palliative care utilization were observed in black (1.1% in black versus 2.1% in white patients, aOR 0.72, 95% CI 061 to 0.84, P<0.01) and Hispanic (1.1% in Hispanic versus 2.1% in whites patients, aOR 0.46, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.68, P<0.01) patients.

On subgroup analysis by hospital percentage of minority patients, we observed similarly low rates of palliative care utilization in hospitalizations of minority groups compared with hospitalizations of white patients. (Supplemental Figure 1A) With white race as the reference group, the aOR for black people to receive palliative care was 0.69 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.80, P<0.01) in low-minority hospitals and 0.84 (95% CI 0.76 to 0.92, P<0.01) in high-minority hospitals. Similarly, the aOR for Hispanic patients to receive palliative care was 0.45 (95% CI 0.30 to 0.67, P<0.01) in low-minority hospitals and 0.72 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.80, P<0.01) in high-minority hospitals. In our interaction model for racial/ethnic group and hospital minority status, the only significant interaction was between Hispanic race and high-/medium-minority hospitals. Hospitalizations for Hispanic patients had higher odds of receiving palliative care in high- (aOR 1.67, 95% CI 1.08 to 2.60, P=0.02 for interaction) and medium-minority (aOR 1.53, 95% CI 1.00 to 2.33, P=0.047 for interaction) hospitals with the reference group being hospitalizations for Hispanic patients in low-minority hospitals.

Differences on palliative care utilization by race/ethnicity also occurred by hospital size, with Hispanic and black patients being significantly less likely to receive palliative care services in medium and large hospitals. With white race as the reference group, the aOR for black patients to receive palliative care was 0.65 (95% CI 0.47 to 0.89, P<0.01) in medium hospitals and 0.73 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.90, P<0.01) in large hospitals. Similarly, the aOR for Hispanic patients to receive palliative care was 0.29 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.75, P=0.01) in medium hospitals and 0.56 (95% CI 0.35 to 0.89, P=0.01) in large hospitals (Supplemental Table 1A). Other hospital characteristics did not reveal a consistent theme.

These racial/ethnic disparities persisted in several subgroups of patient characteristics (shown in Supplemental Figure 1B). Minority patients hospitalized with higher income or private insurance received similar rates of palliative care as white patients. Significant differences in palliative care utilization by racial/ethnic group only persisted in the low- and median-income groups (aOR 0.93, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.53, P=0.76 in >$63,000 versus aOR 0.66, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.85, P<0.01 in <$38,999 for black patients).

Discussion

In this nationwide retrospective cohort study, we identified a significant increase in inpatient palliative care utilization among hospitalized patients with ESKD, however, overall utilization remained low. Moreover, minority groups of black and Hispanic patients compared with white patients received significantly less palliative care services regardless of hospital subtype. Although there were significant increases in palliative care utilization in all races/ethnicities, the racial disparities increased during the study period with the utilization of palliative care services increasing the fastest in white patients. In addition, our study demonstrated variability in the use of palliative care services both in different geographic areas and different types of hospitals. It is also associated with patient socioeconomic status.

Nationwide, there is a growing interest in providing palliative care to patients with advanced chronic diseases, including those with ESKD.23,24,29,30 To date, our study is the first to identify an increasing trend in the usage of palliative care in the ESKD population. Our study identified a higher rate of inpatient palliative care utilization compared with previous studies, likely due to the differences in the patient populations such as the inclusion of patients with Medicaid and private insurance rather than only patients with Medicare, and the inclusion of palliative care services not just hospice care.31 Increased accessibility to palliative care programs in the inpatient and outpatient setting, especially in larger institutions, likely contributes to the increased trends we identified.32

Despite the increasing usage, palliative care remains under utilized in the ESKD population, with <1% of hospitalized patients with ESKD receiving palliative care services, as reported in other studies.31,33 This rate is significantly lower than other conditions with similarly high rates of morbidity and mortality, such as malignancy, advanced lung disease, and stroke.30,34–38 Provider characteristics including lack of training in end-of-life transitioning, significant heterogeneity in nephrologists’ practice patterns, and attitudes toward palliative care services may contribute to the lower rates of palliative care services in patients with ESKD. We also recognize that financial incentives exist for continuing dialysis. Compared with nephrologists in countries with universal healthcare systems and those that lack financial incentives for dialysis, nephrologists in the United States were found to be more inclined to initiate or continue dialysis and less accepting of conservative kidney management in patients with ESKD.19,39

Cultural and societal understanding of the role of dialysis and palliative care services further affects palliative care utilization in patients on dialysis. Family members and non-nephrology providers may request to continue aggressive care including dialysis initiation/continuation despite limited or no benefit in overall prognosis or survival in the patient who is morbidly ill.19 Recent studies have shown limited to no survival benefit for older patients with a high comorbidity profile, especially those with a history of ischemic heart disease, in pursuing dialysis initiation compared with conservative management.40,41 Moreover, palliative care services are not limited to hospice and end-of-life transitioning; they are also important for symptom control, addressing goals of care, reducing readmissions, and reducing cost in the kidney disease population as well as the general population.12,20,42–44 Several groups have now developed guidelines and communication workshops focused on facilitating early encounters for advanced care planning and shared decision making in patients with ESKD.45,46 We expect the use of palliative care services among selected patients with ESKD to further improve.

Despite the increasing trend of palliative care usage, our study demonstrated significant racial and ethnic disparities among certain minority groups. Even after adjustment for patient- and hospital-level factors, black and Hispanic patients were less likely to receive palliative care compared with white patients, and these disparities remained persistent even on subgroup analysis of different hospital-level factors. Compared with white patients, these minority patients received less palliative care even in high- and medium-minority hospitals where presumably providers were exposed to a higher volume of minority patients. Additionally, although there were significant differences in comorbidities and age between minority patients and white patients (Supplemental Table 2), these disparities remained significant even after adjustment for differences in age, gender, comorbidities, and socioeconomic factors. Racial disparities in dialysis discontinuation at the end-of-life and hospice care among patients with ESKD was recently identified.20 Minority patients were less likely to receive hospice care, less likely to discontinue dialysis, and more likely to die in the hospital. Our study complements previous literature and shows persistent racial disparities in end-of-life care of patients with ESKD in the hospital.

Racial disparities in palliative care services are not limited to the ESKD population but also suggested by studies in other populations including those with cancer, stroke, end stage liver disease, end stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and heart failure.23,24,47–50 The reasons of these disparities are complex, multifactorial, and still under investigation. Dissatisfaction with clinical care and mistrust of providers are potential barriers for black patients to receive palliative care.47 Moreover, a unique finding of our study is that significant interaction exists between race/ethnicity and the hospital’s minority proportion. Hispanic patients are more likely to receive palliative care in high-minority hospitals compared with low-minority hospitals. This possibly underlines inherent system-level differences between low-minority hospitals and high-minority hospitals and may possibly be explained by cultural sensitivity and fewer language barriers in high-minority hospitals. Cultural and religious preferences in end-of-life care, especially in Hispanic patients, have also been reported.51

Our study demonstrates similar rates of palliative care referral in Asian patients compared with white patients. This is a surprising finding and may be associated with a higher socioeconomic profile in Asian patients compared with other minority patients (data shown in Supplemental Table 2).49 However, there are no previous studies in Asian patients with ESKD regarding palliative care use and this finding needs to be studied further. Interestingly, our subgroup analysis shows the racial disparity is only significant in minority populations with low level of income or nonprivate insurance, indicating a role of socioeconomic status affecting palliative care service usage in minority groups. The lack of coverage in specialized inpatient hospice facilities by Medicare and Medicaid may alter certain patients’ disposition.52 Further studies are needed to determine the reasons for the racial disparities in an effort to improve end-of-life care in minority patients.

Our study also demonstrated several hospital-level factors associated with the differences in palliative care usage. Larger hospitals and teaching hospitals are providing more palliative care services than smaller hospitals and nonteaching hospitals. These findings are also suggested in the provision of palliative care services in patients with cirrhosis and cancer.34,53,54 There are also significant geographic differences throughout the country. Variations in accessibility to palliative care based upon hospital size and geographic location have been previously reported for other conditions.29 Our study and other studies in patients with malignancy and stroke which used the NIS found that hospitals in the Northeast had lower rates of palliative care use.34,38 However, studies which used non-NIS databases found that hospitals in New England had the highest use of in-hospital palliative care services in the general patient population.29 The differences in regional variation patterns may be explained by different sampling methods among databases. It could also be associated with inherent differences between patients on dialysis and other patient populations in different geographic locations. As palliative care is increasingly adopted by hospitals both in the inpatient and outpatient setting, this variation among different hospital types may change in the future.

Although the use of a nationally representative sample allows for power and generalizability, we do recognize several limitations. The NIS database is based on hospitalization data rather than patient data which means multiple admissions could be present for the same patient. Therefore the rate for palliative care referral may be overestimated. This study is also prone to coding error because diagnosis and procedures were coded as ICD-9-CM codes. We acknowledge that we did not have direct information on the availability of palliative care services for individual hospitals or the change in the availability of services over time. We used hospital size/teaching status as proxies which are highly correlated with palliative care services, however, there may be residual confounding. The database is dated up to 2015 at the time of our study, but the 2015 data were not included due to a mixture of ICD-10 and ICD-9-CM codes. Due to the nature of the NIS being an inpatient database, postdischarge data such as mortality after discharge, palliative care encounter as an outpatient, and readmission rates were not captured. As the NIS is an administrative database, we are unable to assess the clinician or patient preference to palliative care services, or the effect of religion and cultural beliefs on palliative care utilization. Finally, as in all database and retrospective studies, we cannot rule out the possibility of residual confounding.

In summary, despite low rates of palliative care usage, there was a substantial increase in the provision of palliative care among hospitalized patients with ESKD on dialysis from 2006 to 2014. Significant racial/ethnic disparities occurred in palliative care utilization and these persisted across all hospital subtypes. Further investigation into causes of racial disparities is necessary to improve access to palliative care services in the vulnerable ESKD population.

Disclosures

Coca reports personal fees and other from RenalytixAI, personal fees from CHF Solutions, personal fees from Quark, personal fees from Takeda, personal fees from Janssen, personal fees and “other” from pulseData, and personal fees from Goldfinch, outside the submitted work. Nadkarni reports personal fees from Renalytix AI, from Pensieve Health, personal fees from BioVie, and grants from Goldfinch Bio, outside the submitted work.

Funding

Chan is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (5T32DK007757-18). Nadkarni is supported in part by the NIH (1K23DK107908-01A1).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Wen, Dr. Jiang, Dr. Nadkarni, and Dr. Chan participated in the study design. Dr. Wen and Dr. Jiang carried out statistical analysis. Dr. Wen, Dr. Nadkarni, and Dr. Chan analyzed the data. Dr. Wen, Dr. Koncicki, Dr. Horowitz, Dr. Cooper, Dr. Coca, Dr. Nadkarni, and Dr. Chan drafted and revised the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Another Example of Race Disparities in the US Healthcare System,” on pages 1553–1554.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2018121256/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. ICD 9 codes for inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Supplemental Table 2. Baseline characteristics of hospitalizations of ESRD patients based on racial/ethnic group.

Supplemental Figure 1A. Subgroup analysis of the odds of palliative care referral among each minority group compared with white based on hospital characteristics.

Supplemental Figure 1B. Subgroup analysis of the odds of palliative care referral among each minority group compared with white based on patient-level characteristics.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System : 2017 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan HW, Clayton PA, McDonald SP, Agar JWM, Jose MD: Risk factors for dialysis withdrawal: An analysis of the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant (ANZDATA) registry, 1999-2008. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 775–781, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Johnson JA: Cross-sectional validity of a modified Edmonton symptom assessment system in dialysis patients: A simple assessment of symptom burden. Kidney Int 69: 1621–1625, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yong DS, Kwok AO, Wong DM, Suen MH, Chen WT, Tse DM: Symptom burden and quality of life in end-stage renal disease: A study of 179 patients on dialysis and palliative care. Palliat Med 23: 111–119, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flythe JE, Hilliard T, Lumby E, Castillo G, Orazi J, Abdel-Rahman EM, et al.: Kidney Health Initiative Prioritizing Symptoms of ESRD Patients for Developing Therapeutic Interventions Stakeholder Meeting Participants : Fostering innovation in symptom management among hemodialysis patients: Paths forward for insomnia, muscle cramps, and fatigue. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 150–160, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rome RB, Luminais HH, Bourgeois DA, Blais CM: The role of palliative care at the end of life. Ochsner J 11: 348–352, 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.May P, Normand C, Morrison RS: Economic impact of hospital inpatient palliative care consultation: Review of current evidence and directions for future research. J Palliat Med 17: 1054–1063, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, Dionne-Odom JN, Ernecoff NC, Hanmer J, et al.: Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 316: 2104–2114, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.May P, Normand C, Cassel JB, Del Fabbro E, Fine RL, Menz R, et al.: Economics of palliative care for hospitalized adults with serious illness: A meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 178: 820–829, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallace SK, Waller DK, Tilley BC, Piller LB, Price KJ, Rathi N, et al.: Place of death among hospitalized patients with cancer at the end of life. J Palliat Med 18: 667–676, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horton JR, Morrison RS, Capezuti E, Hill J, Lee EJ, Kelley AS: Impact of inpatient palliative care on treatment intensity for patients with serious illness. J Palliat Med 19: 936–942, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chettiar A, Montez-Rath M, Liu S, Hall YN, O’Hare AM, Kurella Tamura M: Association of inpatient palliative care with health care utilization and postdischarge outcomes among medicare beneficiaries with end stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1180–1187, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davison SN: End-of-life care preferences and needs: Perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 195–204, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen JC, Thorsteinsdottir B, Vaughan LE, Feely MA, Albright RC, Onuigbo M, et al.: End of life, withdrawal, and palliative care utilization among patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis therapy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1172–1179, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med 172: 661–663, discussion 663–664, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eneanya ND, Hailpern SM, O’Hare AM, Kurella Tamura M, Katz R, Kreuter W, et al.: Trends in receipt of intensive procedures at the end of life among patients treated with maintenance dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 69: 60–68, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feely MA, Hildebrandt D, Edakkanambeth Varayil J, Mueller PS: Prevalence and contents of advance directives of patients with ESRD receiving dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 2204–2209, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Renal Physicians Association : Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis: Clinical Practice Guideline, 2nd Ed., Rockville, MD, Renal Physicians Association, 2010, pp 39–92 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grubbs V, Tuot DS, Powe NR, O’Donoghue D, Chesla CA: System-level barriers and facilitators for foregoing or withdrawing dialysis: A qualitative study of nephrologists in the United States and England. Am J Kidney Dis 70: 602–610, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foley RN, Sexton DJ, Drawz P, Ishani A, Reule S: Race, ethnicity, and end-of-life care in dialysis patients in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 2387–2399, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wetmore JB, Yan H, Hu Y, Gilbertson DT, Liu J: Factors associated with withdrawal from maintenance dialysis: A case-control analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 831–841, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas BA, Rodriguez RA, Boyko EJ, Robinson-Cohen C, Fitzpatrick AL, O’Hare AM: Geographic variation in black-white differences in end-of-life care for patients with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1171–1178, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel B, Secheresiu P, Shah M, Racharla L, Alsalem AB, Agarwal M, et al.: Trends and predictors of palliative care referrals in patients with acute heart failure. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 36: 147–153, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rush B, Hertz P, Bond A, McDermid RC, Celi LA: Use of palliative care in patients with end-stage COPD and receiving home oxygen: National trends and barriers to care in the United States. Chest 151: 41–46, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Databases: Overview of the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS). Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed March 10, 2018.

- 26.Faigle R, Ziai WC, Urrutia VC, Cooper LA, Gottesman RF: Racial differences in palliative care use after stroke in majority-white, minority-serving, and racially integrated U.S. hospitals. Crit Care Med 45: 2046–2054, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan L, Tummalapalli SL, Ferrandino R, Poojary P, Saha A, Chauhan K, et al.: The effect of depression in chronic hemodialysis patients on inpatient hospitalization outcomes. Blood Purif 43: 226–234, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feder SL, Redeker NS, Jeon S, Schulman-Green D, Womack JA, Tate JP, et al.: Validation of the ICD-9 diagnostic code for palliative care in patients hospitalized with heart failure within the veterans health administration. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 35: 959–965, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dumanovsky T, Augustin R, Rogers M, Lettang K, Meier DE, Morrison RS: The growth of palliative care in U.S. hospitals: A status report. J Palliat Med 19: 8–15, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, Leland NE, Miller SC, Morden NE, et al.: Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: Site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA 309: 470–477, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray AM, Arko C, Chen SC, Gilbertson DT, Moss AH: Use of hospice in the United States dialysis population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1248–1255, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meier DE: Increased access to palliative care and hospice services: Opportunities to improve value in health care. Milbank Q 89: 343–380, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davison SN, Levin A, Moss AH, Jha V, Brown EA, Brennan F, et al.: Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes : Executive summary of the KDIGO controversies conference on supportive care in chronic kidney disease: Developing a roadmap to improving quality care. Kidney Int 88: 447–459, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uppal S, Rice LW, Beniwal A, Spencer RJ: Trends in hospice discharge, documented inpatient palliative care services and inpatient mortality in ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 143: 371–378, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuo TL, Lin CH, Jiang RS, Yen TT, Wang CC, Liang KL: End-of-life care for head and neck cancer patients: A population-based study. Support Care Cancer 25: 1529–1536, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murthy SB, Moradiya Y, Hanley DF, Ziai WC: Palliative care utilization in nontraumatic intracerebral hemorrhage in the United States. Crit Care Med 44: 575–582, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gershon AS, Maclagan LC, Luo J, To T, Kendzerska T, Stanbrook MB, et al.: End-of-life strategies among patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 198: 1389–1396, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh T, Peters SR, Tirschwell DL, Creutzfeldt CJ: Palliative care for hospitalized patients with stroke: Results from the 2010 to 2012 national inpatient sample. Stroke 48: 2534–2540, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong SPY, Vig EK, Taylor JS, Burrows NR, Liu C-F, Williams DE, et al.: Timing of initiation of maintenance dialysis: A qualitative analysis of the electronic medical records of a national cohort of patients from the department of veterans affairs. JAMA Intern Med 176: 228–235, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE: Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1955–1962, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verberne WR, Geers AB, Jellema WT, Vincent HH, van Delden JJ, Bos WJ: Comparative survival among older adults with advanced kidney disease managed conservatively versus with dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 633–640, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL: Quality of end-of-life care provided to patients with different serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med 176: 1095–1102, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grubbs V, Moss AH, Cohen LM, Fischer MJ, Germain MJ, Jassal SV, et al.: Dialysis Advisory Group of the American Society of Nephrology : A palliative approach to dialysis care: A patient-centered transition to the end of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 2203–2209, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grubbs V, O’Riordan D, Pantilat S: Characteristics and outcomes of in-hospital palliative care consultation among patients with renal disease versus other serious illnesses. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1085–1089, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurella Tamura M, Meier DE: Five policies to promote palliative care for patients with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1783–1790, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schell JO, Cohen RA: A communication framework for dialysis decision-making for frail elderly patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 2014–2021, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson KS: Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med 16: 1329–1334, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spencer BA, Insel BJ, Hershman DL, Benson MC, Neugut AI: Racial disparities in the use of palliative therapy for ureteral obstruction among elderly patients with advanced prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer 21: 1303–1311, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ngo-Metzger Q, McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Davis RB, Li FP, Phillips RS: Older Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders dying of cancer use hospice less frequently than older white patients. Am J Med 115: 47–53, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langberg KM, Kapo JM, Taddei TH: Palliative care in decompensated cirrhosis: A review. Liver Int 38: 768–775, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cervantes L, Jones J, Linas S, Fischer S: Qualitative interviews exploring palliative care perspectives of Latinos on dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 788–798, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Hospice eligibility requirements. Available at: https://dart.nhpco.org/hospice-eligibility-requirements. Accessed January 25, 2019

- 53.Patel AA, Walling AM, Ricks-Oddie J, May FP, Saab S, Wenger N: Palliative care and health care utilization for patients with end-stage liver disease at the end of life. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 15: 1612–1619.e4, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gani F, Enumah ZO, Conca-Cheng AM, Canner JK, Johnston FM: Palliative care utilization among patients admitted for gastrointestinal and thoracic cancers. J Palliat Med 21: 428–437, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.